Abstract

Wild common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is distributed throughout the Americas from Mexico to northern Argentina. Within this range, the species is divided into two gene pools (Andean and Middle American) along a latitudinal gradient. The diversity of 24 wild common bean genotypes from throughout the geographic range of the species was described by using sequence data from 13 loci. An isolation–migration model was evaluated using a coalescent analysis to estimate multiple demographic parameters. Using a Bayesian approach, Andean and Middle American subpopulations with high percentage of parentages were observed. Over all loci, the Middle American gene pool was more diverse than the Andean gene pool (πsil=0.0089 vs 0.0068). The two subpopulations were strongly genetically differentiated over all loci (Fst=0.29). It is estimated that the two current wild gene pools diverged from a common ancestor ∼111 000 years ago. Subsequently, each gene pool underwent a bottleneck immediately after divergence and lasted ∼40 000 years. The Middle American bottleneck population size was ∼46% of the ancestral population size, whereas the Andean was 26%. Continuous asymmetric gene flow was detected between the two gene pools with a larger number of migrants entering Middle American gene pool from the Andean gene pool. These results suggest that because of the complex population structure associated with the ancestral divergence, subsequent bottlenecks in each gene pool, gene pool-specific domestication and intense selection within each gene pool by breeders; association mapping would best be practised within each common bean gene pool.

Keywords: Phaseolus vulgaris, wildtypes, demography, bottleneck, geneflow, divergence

Introduction

Modern crop diversity depends on the breadth of diversity found within the wild ancestors from which it was derived. The alleles necessary for domestication of the crop are derived from this diversity. From this perspective, it is important to understand the evolutionary history of the species in its wild state with regards to its levels of diversity, linkage disequilibrium (LD) and demographic history. Using multilocus sequence data, it has been shown that wild forms of species, such as maize (Tiffin and Gaut, 2001), sunflower (Liu and Burke, 2006) and poplar (Ingvarsson, 2005), have similar levels of diversity, whereas relative to these species, diversity is reduced in wild barley (Morrell et al., 2003) and wild rice species (Zhu et al., 2007). Diversity within the cultivated form of maize was 60% of that found in its wild ancestor (Tenallion et al., 2004). Coalescent simulations that modeled the demographic effects relative to selection determined that domestication within wild maize involved a small population of individuals. For rice, diversity was severely reduced to 20% of that found in wild genotypes (Zhu et al., 2007). At the other extreme is einkorn wheat where wild and domesticated forms had equal diversity levels (Kilian et al., 2007). Multilocus sequence data also supported a single domestication event for each of these three species (Tenaillon et al., 2004; Kilian et al., 2007; Molina et al., 2011).

The patterns of nucleotide diversity within and among populations are influenced by evolutionary forces, such as mutation, population structure and gene flow, at the genome level (Wright and Gaut, 2005; Arunyawat et al., 2007), and recombination and natural selection at the gene level (Schmid et al., 2005). Demographic parameters such as effective population sizes of current and ancestral populations, species divergence times and gene flow rates between populations collectively define biogeographic histories and the process of population divergence and/or speciation (Strasburg and Rieseberg, 2010). Collectively, these events leave traces on the pattern of the genetic diversity (Pyhajarvi et al., 2007) within the species and can be used to define the demographic history of the species. Multilocus DNA sequence data contains a wealth of information used to describe nucleotide variation and demographic parameters in multiple plant species (Liu and Burke, 2006; Arunyawat et al., 2007; Haudry et al., 2007; Pyhajarvi et al., 2007; Zhang and Ge, 2007; Zhu et al., 2007; Ingvarsson, 2008; Stadler et al., 2008; Strasburg and Rieseberg, 2008; Chen et al., 2010). It can also be used to model demographic parameters using coalescent analysis (Pyhajarvi et al., 2007; Stadler et al., 2008; Strasburg and Rieseberg, 2008). Multiple parameters can be estimated by comparing the output from the coalescent analysis with observed nucleotide diversity data. Recently, the inference of demographic parameters from genetic data has become an integral part of conservation genetic studies (Lopes and Boessenkool, 2010).

The focus here is on common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), the most consumed food legume in the world and is a major source of protein for Latin America and Africa (Graham and Vance, 2003). Common bean is a highly structured species. Wild beans are partitioned into two large gene pools based on phaseolin seed protein variation (Gepts et al., 1986), DNA marker diversity (Becerra Velasquez and Gepts, 1994; Freyre et al., 1996; Tohme et al., 1996), morphology (Gepts and Debouck, 1991), isozymes (Koenig and Gepts, 1989) and mitochondrial DNA RFLPs (Khairallah et al., 1992). The wild Middle American gene pool extends from Mexico through Central America and into Venezuela and Colombia, whereas the Andean gene pool is found in Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. These two gene pools overlap in Colombia (Gepts and Bliss, 1986). Similar molecular analyses have shown that domesticated common bean is also split into two gene pools, and each gene pool consists of multiple races that in general have a similar geographical distribution as wild genotypes (Singh et al., 1991).

Recently, a multilocus sequence analysis determined that for each gene pool the cultivated form of the species arose by a single domestication event (Mamidi et al., 2011) out of distinct wild gene pools. This is unique among domesticated crop species studied to date that exhibited a single domestication event out of a single wild gene pool (Tenaillon et al., 2004; Kilian et al., 2007; Molina et al., 2011). The duration of the Middle American domestication bottleneck, 8160–6260 years before the present (BP), was longer than the Andean duration, 8500–7012 years BP. These dates are consistent with archeological evidence (Kaplan and Lynch, 1999). Additionally, the domestication bottleneck population size for the Andean gene pool was about 50% of that of the Middle American, a result that explains the consistent observation of reduced sequence variability within Andean landraces (McClean et al., 2004; McClean and Lee, 2007). Following the bottleneck, each species experienced a population expansion and divergence into races.

What has not been modeled previously is the evolutionary history of the wild form of a cultivated plant species using the coalescent approach. Here we collected multilocus sequence data from wild P. vulgaris genotypes, determined the nucleotide variation within this collection, described the evolutionary forces that contributed to the population structure of the progenitors of domesticated common bean, and estimated demographic parameters. Given the many reports that show the wild members of P. vulgaris are split into two gene pools, and that domesticated forms appear to have been derived from those two pools, we estimated these parameters using a single isolation–migration (IM) model. Understanding the genetic architecture of the wild common bean will help design approaches to mine the genetic diversity (Singh, 2001; Acosta-Gallegos et al., 2007) for the many adaptive traits that may be necessary under a climate-change scenario (Muraya et al., 2010; McClean et al., 2011).

Materials and methods

Genetic material, DNA isolation and sequence analysis

A collection of 24 wild P. vulgaris genotypes with a geographic distribution ranging from Northern Mexico to Northwestern Argentina were analyzed (Table 1). The genotypes were selected to represent the haplotype variability at the CHI intron-3 and DFR intron loci (McClean et al., 2004; McClean and Lee, 2007). A total of 13 nuclear loci were selected for sequencing with at least one locus located on each chromosome (McConnell et al., 2010; Mamidi et al., 2011).

Table 1. Wild common bean genotypes used for this study of diversity and demography.

| Wild types | Countrya | Latitude/longitudea | CHI intron-3b | DFR intron 1b | Gene poola |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI 417671 | Mexico | 28.600, −107.167 | 1 | 3B | Middle American |

| PI 318698 | Mexico | 21.083, −104.500 | 2A | 8 | Middle American |

| PI 417770 | Mexico | 20.700, −102.350 | 8 | 4 | Middle American |

| PI 535409 | Mexico | 19.917, −103.333 | 9D | 8 | Middle American |

| PI 535430 | Mexico | 18.983, −99.100 | 9B | 2 | — |

| PI 535450 | Mexico | 18.983, −99.100 | 4 | 4 | Middle American |

| W6 20516 | Guatemala | 15.667, −91.783 | — | 7B | Middle American |

| PI 310514 | Honduras | 15.000, −86.500 | 1 | 6A | Middle American |

| W6 20523 | Guatemala | 14.767, −91.517 | 9A | 7A | Middle American |

| W6 20522 | Guatemala | 14.750, −91.517 | 8 | 5 | Middle American |

| PI 201013 | El Salvador | 13.917, −89.850 | 9C | 5 | Middle American |

| W6 12107 | Costa Rica | 8.950, −83.083 | 9C | 3B | — |

| PI 326054 | Venezuela | 8.117, −72.250 | 9C | 5 | Andean |

| DGD 1962 | Peru | −7.12, −78.78 | 1 | 6 | — |

| PI 390770 | Peru | −13.967, −75.083 | 6 | 1A | Andean |

| W6 18819 | Bolivia | −19.283, −64.333 | 6 | 7B | Andean |

| W6 17002 | Argentina | −23.467, −64.933 | 7 | 1E | Andean |

| W6 16999 | Argentina | −23.479, −64.947 | 2B | 1E | Andean |

| W6 17000 | Argentina | −23.482, −64.947 | 7 | 1D | Andean |

| W6 17005 | Argentina | −23.706, −65.533 | 5A | 1C | Andean |

| W6 17501 | Argentina | −24.650, −65.367 | 2B | 1E | Andean |

| W6 17499 | Argentina | −24.900, −65.483 | 3A | 2 | Andean |

| W6 17474 | Argentina | −25.161, −65.611 | 2B | 1A | Andean |

| W6 17468 | Argentina | −27.817, −65.783 | 2B | 1E | Andean |

Collection site of the sample.

Haplotype from analysis of CHI intron-3 and DFR intron.

Assignment of individuals to gene pool based on our structure analysis.

DNA was extracted from young leaves using the procedure described in Brady et al. (1998), and the 13 loci were amplified using standard PCR conditions. The amplified fragments were sequenced from both directions using Beckman CEQ 2000XL DNA Analysis System (Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, CA, USA). The DNA sequence chromatograms were analyzed using the Staden Package (Staden, 1996; http://staden.sourceforge.net/). Gene annotation and structure were identified by blastx against the Viridiplantae database at NCBI. All sequences are deposited in the GenBank database.

Population differentiation and nucleotide diversity

To differentiate individuals into subpopulations, population structure was investigated using the STRUCTURE 2.2 software (Pritchard et al., 2000). Combined data for all loci was used for this analysis. Given that the common bean is a highly self-fertilizing species, the haploid phase setting was used for the data analysis. The use of an admixture model was included based on the results of Rossi et al. (2009). We set k (the number of subpopulations) from 1 to 6 and performed 10 runs for each k value. For each run, a burn in of 100 000 iterations was followed by an additional 500 000 iterations. We considered the STRUCTURE posterior probability for each k value and the Evanno et al. (2005) Δk output to select the subpopulation number. Individuals with membership coefficients of qi⩾0.7 in STRUCTURE 2.2 runs were assigned to a specific group. The subpopulations were further defined as gene pools based on the geographic distribution of individuals within that subpopulation. To further differentiate the subpopulations, neighbor-joining (NJ) trees for the combined loci were built in ClustalX (Larkin et al., 2007) and bootstrapped over 1000 replicates.

Once the subpopulations were defined, Fst tests of population differentiation (Hudson et al., 1992) were performed using DnaSP 4.90 (Rozas and Rozas, 1999). Population differentiation was further assessed using the Hudson's Snn (Hudson, 2000) statistic, and the significance was determined with 10 000 permutations. The number of shared (Ss) and fixed (Sf) silent sites between populations, and the number of unique silent sites (SAnd and SMA) in each population were analyzed. Unless noted otherwise, population parameters were estimated using DnaSP 4.90.

Nucleotide diversity for silent sites (synonymous and noncoding) were estimated for the complete population and the subpopulations separately. The estimated parameters include: Watterson's estimator (θw=4Neμ), the average number of pairwise differences per site between sequences in a sample (π), number of segregating sites (S), the number of haplotypes (h) and haplotype diversity (Hd).

To test for departure from a neutral equilibrium model of evolution, Tajima's D (DT; Tajima (1989)) was estimated. A multilocus Hudson–Kreitman–Aguadé (HKA) test (Hudson et al., 1987) across genetically unlinked or loosely linked loci was performed using the HKA program (http://genfaculty.rutgers.edu/hey/software) to discriminate between selection and population demography. P. coccineus genotypes PI 325589 and PI 325599 were used as outgroup members. The minimum number of recombination events (Rm) at silent sites was determined using the four-gamete test of Hudson and Kaplan (1985). The number of significant pairwise LD comparisons was evaluated using Fisher's exact test and the Bonferroni procedure. The Zns statistic, which is the average of r2 of all pairwise comparisons, was calculated. The expected decay of LD with physical distance was graphed using a non-parametric regression equation suggested in Remington et al. (2001) in SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA).

Demographic parameter estimation

Demographic parameters were estimated in two steps. In the first step, the MIMAR program (Becquet and Przeworski, 2007) was used to estimate divergence parameters for an IM model with the priors described in Table 2. MIMAR uses four statistics known to be sensitive to the parameters of the IM model (Wakeley and Hey, 1997; Leman et al., 2005). MIMAR outputs the posterior distribution of the parameters for a given data set obtained using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation that allows for intra locus recombination. The MCMC was run for 20 million steps after an initial 5 million burn in with sampling every 1000 steps. We tested different ranges of priors, burn ins and variances of kernel distributions. The MIMAR autocorrelation function was used to discover a combination of values that gave good mixture of parameter values (Chen et al., 2010). A variable locus specific recombination rate was used. To test if the estimated IM parameters (NA, NMA, NAnd, T3, M12 and M21) described a model that was consistent with the observed data, we conducted a goodness of fit test using MIMARgof. Simulated and observed values of SAnd, SMA, Sf, Ss, π, Fst and DT at silent sites were compared by the test.

Table 2. Priors used for simulations and posteriors estimated after simulations.

| Parameters | Priors |

Posteriors |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | 95% CI | ||

| Step 1: IM model of wild types | |||

| Time of divergence (T3) | 10 000–200 000 | 110 706 | 55 931–196 101 |

| θAncestral | 0.001–0.02 | 0.0102 | 0.0059–0.0165 |

| Ancestral population sizea | 223 970 | 129 308–361 586 | |

| θAndean | 0.001–0.02 | 0.0033 | 0.0014–0.0150 |

| Population size (Andean)a | 73 428 | 30 892–329 891 | |

| θMA | 0.001–0.02 | 0.0071 | 0.0025–0.0194 |

| Population size (MA)a | 156 414 | 55 079–425 389 | |

| Migration—MA to And (M12)b | 0.0009–20 | 0.0968 | 0.0011–5.3925 |

| Migration—And to MA (M21)b | 0.0009–20 | 0.2658 | 0.0011–3.3036 |

| Step 2: wild types bottleneck | |||

| Middle American | |||

| Start of bottleneck (T2M) | 10 000–200 000 | 103 065 | 76 674–134 017 |

| End of bottleneck (T1M) | Start–200 000 | 62 794 | 38 480–83 407 |

| Bottleneck population size (% of Ne)c | 1–100 | 46.26 | 35.17–67.54 |

| Recombination rate (ρ) | 1E-10–1E-05 | 5.06E-06 | 3.32E-06–6.49E-06 |

| Andean | |||

| Start of bottleneck (T2A) | 10 000–200 000 | 103 695 | 58 000–154 900 |

| End of bottleneck (T1A) | Start–200 000 | 60 050 | 29 600–95 040 |

| Bottleneck population size (% of Ne)c | 1–100 | 25.72 | 14.15–38.42 |

| Recombination rate (4Neρ) | 1E-10–1E-05 | 4.94E-06 | 2.22E-06–7.5E-06 |

Abbreviations: And, Andean; MA, Middle-America.

Population size calculated from θ=4Nμ using a mutation rate (μ) of 6.1E-09 and then scaled using Ne=(2−s) N/s.

Migration rate is in terms of M=4Nem.

The effective population size is assumed to be 220 000, equivalent to MIMAR estimate of ancestral population size.

In the second step, the bottleneck population size was estimated separately for each gene pool using Hudson ms (Hudson, 2002) in an Approximate Bayesian Computation pipeline. A simple demographic model was modeled in which the ancestral population (NA) was split to a bottleneck population size (NBMA and NBAnd) at time T2M and T2A in the Middle American and Andean gene pools, respectively. The bottleneck ended at times T1M and T1A, respectively, with duration time equal to T2M−T1M and T2A−T1A, respectively, for each of the two gene pools. This was followed by an exponential growth to the present size. The priors for present-day population size and bottleneck start times were derived from the 99% confidence interval (CI) of MIMAR results from the first step. Ancestral population size and the effective population size (Ne) are assumed to be 220 000 individuals. A total of 10 million simulations per locus were run, and these simulations were piped to msstats software (available at http://molpopgen.org) to obtain the summary statistics for each of the simulation. All the priors including the recombination rate are listed in Table 2. The summary statistics of the simulations were compared with the statistics observed for the sequenced wild genotypes. The Euclidean distance was calculated between simulated and observed summary statistics using S, H, π, DT and Zns. We accepted 10 000 simulations with a Euclidean distance less than 0.01. The summary statistics for the accepted simulations were subjected to a Principal Component Analysis using the PRINCOMP procedure in SAS 9.2. The parameters were then estimated from the accepted 10 000 simulations using the general linear model (GLM), described in Leuenberger and Wegmann (2010), using the GLM procedure in SAS 9.2.

Combining the results for the goodness of fit test of our IM parameters estimated using MIMAR and bottleneck parameters estimated using ms, we performed 10 million simulations in Hudson ms. We compared the results of the simulations with the observed means of θ, π, DT, H, Hd and Zns data across the 13 loci within each gene pool. If the observed data fits within the 95% CI of simulated data, it can be said that the model and parameters are appropriate.

Results

Population differentiation

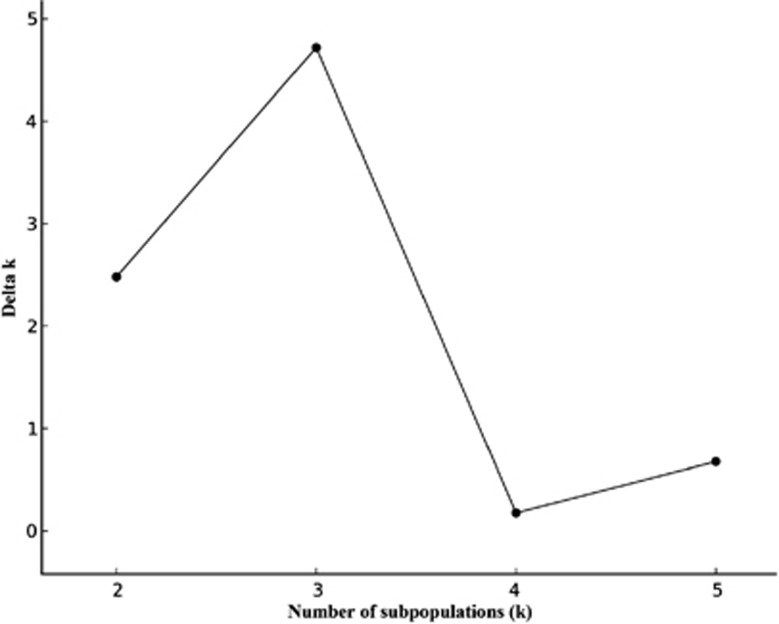

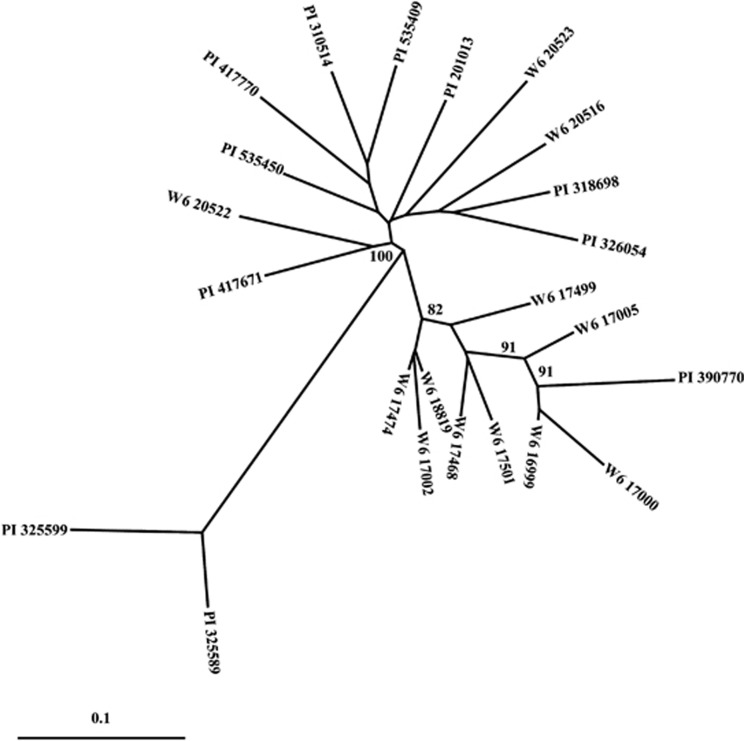

Sequence data for 13 nuclear loci were obtained from 24 wild common bean genotypes (Table 3). The length of the aligned sequence varied from 341 bp to 689 bp, and a total of 6.4 kb (4.13 kb of coding region) of sequence data was analyzed. Subpopulations were defined using the combined sequence data from all loci with the Bayesian approach implemented in STRUCTURE. Both the highest posterior probability approach (recommended in the STRUCTURE manual) and the Δk method of Evanno et al. (2005) (Figure 1) indicated the population was best represented by three subpopulations. In all, 21 genotypes were assigned to one of the two major groups based on a subpopulation membership coefficient of qi>0.7. Samples from Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela and Peru grouped together in an Andean subpopulation, whereas a Middle American subpopulation was represented by samples from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. Three genotypes (DGD 1962, PI 535430, W6 12107), assigned to a third group with a major subpopulation membership coefficient of less than 0.7, were considered to be recently admixed genotypes. Because of our interest to evaluate events in a more distant past, and as this subpopulation did not appear representative of the ancestral wild populations, they were excluded from further analysis. A NJ analysis of the remaining 21 genotypes, using the combined data from all loci, defined a tree with two clusters (Figure 2). The cluster separation was supported with a bootstrap value of 100% (1000 replicates). The NJ cluster membership was same as that generated with the STRUCTURE analysis. The results of the two analyses were also consistent with the geographically based two-gene-pool model of wild P. vulgaris and strongly suggested that this population of 21 genotypes was appropriate for our demographic analyses.

Table 3. Diversity and neutrality parameters at the silent sites of each locus studied.

| Locus | Pop | n | S | H | Hd | πsil | θsil | πnonsyn/πsyn | Tajima D | Rm | Zns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g1224 | All | 19 | 7 | 7 | 0.608 | 0.0080 | 0.0132 | 0.0679 | −1.310 | 0 | 0.082 |

| MA | 9 | 5 | 6 | 0.833 | 0.0106 | 0.0121 | 0.0853 | −0.526 | 0 | 0.100 | |

| And | 10 | 4 | 3 | 0.378 | 0.0029 | 0.0049 | — | −1.667 | 0 | 1.000 | |

| g680 | All | 18 | 10 | 10 | 0.850 | 0.0082 | 0.0102 | 0.5687 | −0.496 | 0 | 0.098 |

| MA | 7 | 8 | 7 | 1.000 | 0.0105 | 0.0111 | 0.5495 | −0.216 | 0 | 0.175 | |

| And | 11 | 4 | 5 | 0.618 | 0.0024 | 0.0034 | 0.5212 | −0.639 | 0 | 0.114 | |

| g2218 | All | 21 | 3 | 3 | 0.529 | 0.0037 | 0.0044 | 0.3010 | −0.467 | 0 | 0.127 |

| MA | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0.467 | 0.0025 | 0.0019 | 0.6161 | 0.819 | 0 | 0.126 | |

| And | 11 | 3 | 2 | 0.182 | 0.0029 | 0.0055 | 0.0887 | −1.600 | 0 | 0.505 | |

| g1375 | All | 21 | 14 | 16 | 0.971 | 0.0354 | 0.0394 | 0.0427 | −0.368 | 2 | 0.067 |

| MA | 10 | 8 | 9 | 0.978 | 0.0324 | 0.0286 | 0.0408 | 0.567 | 1 | 0.150 | |

| And | 11 | 9 | 7 | 0.909 | 0.0254 | 0.0311 | 0.0728 | −0.771 | 2 | 0.168 | |

| CV533374 | All | 20 | 5 | 4 | 0.621 | 0.0056 | 0.0085 | 0.0363 | −1.060 | 0 | 0.149 |

| MA | 10 | 4 | 3 | 0.378 | 0.0048 | 0.0086 | 0.0822 | −1.667 | 0 | 0.210 | |

| And | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0.200 | 0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.0000 | −1.112 | 0 | — | |

| g1159 | All | 20 | 7 | 7 | 0.768 | 0.0062 | 0.0080 | 1.3911 | −0.770 | 1 | 0.079 |

| MA | 10 | 6 | 5 | 0.844 | 0.0082 | 0.0086 | — | −0.236 | 1 | 0.140 | |

| And | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0.644 | 0.0039 | 0.0058 | 0.4785 | −1.244 | 0 | 0.205 | |

| g2129 | All | 20 | 13 | 7 | 0.784 | 0.0194 | 0.0154 | 0.0200 | 0.937 | 4 | 0.239 |

| MA | 9 | 12 | 4 | 0.750 | 0.0217 | 0.0186 | 0.0000 | 0.449 | 1 | 0.424 | |

| And | 11 | 11 | 5 | 0.618 | 0.0132 | 0.0158 | 0.0527 | −0.720 | 0 | 0.318 | |

| g776 | All | 20 | 14 | 7 | 0.521 | 0.0036 | 0.0084 | 0.3784 | −2.100* | 0 | 0.169 |

| MA | 10 | 12 | 6 | 0.778 | 0.0053 | 0.0079 | 0.3282 | −1.440 | 0 | 0.219 | |

| And | 10 | 3 | 2 | 0.200 | 0.0015 | 0.0026 | — | −1.562 | 0 | 1.000 | |

| D1468 | All | 20 | 8 | 4 | 0.437 | 0.0047 | — | 0.7799 | 0.873 | 0 | 0.359 |

| MA | 10 | 8 | 4 | 0.733 | 0.0074 | 0.0061 | — | −0.357 | 0 | 0.485 | |

| And | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.0005 | — | 0.7793 | — | 0 | 1.000 | |

| g2393 | All | 19 | 6 | 8 | 0.819 | 0.0108 | — | 0.5304 | 0.468 | 2 | 0.157 |

| MA | 8 | 4 | 5 | 0.786 | 0.0067 | — | 0.3306 | −1.030 | 0 | 0.181 | |

| And | 11 | 6 | 5 | 0.709 | 0.0102 | — | 0.5438 | −0.445 | 0 | 0.208 | |

| g634 | All | 21 | 10 | 5 | 0.643 | 0.0150 | 0.0109 | 1.0208 | 1.291 | 1 | 0.505 |

| MA | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0.356 | 0.0028 | 0.0028 | 2.1185 | 0.019 | 0 | 0.641 | |

| And | 11 | 10 | 5 | 0.782 | 0.0206 | 0.0134 | 0.8321 | 0.271* | 1 | 0.562 | |

| g1661 | All | 20 | 4 | 6 | 0.768 | 0.0096 | 0.0072 | 0.0489 | 1.020 | 2 | 0.105 |

| MA | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.511 | 0.0058 | 0.0054 | 0.2570 | 0.247 | 0 | 0.341 | |

| And | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0.644 | 0.0072 | 0.0091 | 0.0000 | −0.834 | 1 | 0.251 | |

| g1215 | All | 20 | 5 | 5 | 0.742 | 0.0061 | 0.0046 | 0.0200 | 0.985 | 0 | 0.140 |

| MA | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0.711 | 0.0057 | 0.0046 | 0.0000 | 0.927 | 0 | 0.344 | |

| And | 10 | 4 | 3 | 0.378 | 0.0031 | 0.0046 | 0.0745 | −1.244 | 0 | 0.242 | |

| Average | All | 7.6 | 6.36 | 0.647 | 0.0097 | 0.0109 | 0.3719 | 0.085 | 0.86 | 0.175 | |

| MA | 5.5 | 4.29 | 0.652 | 0.0089 | 0.0090 | 0.3673 | −0.175 | 0.21 | 0.272 | ||

| And | 4.5 | 3.43 | 0.447 | 0.0068 | 0.0082 | 0.2870 | −0.986 | 0.29 | 0.464 |

Abbreviations: And, Andean; MA, Middle-America.

*P<0.05.

Figure 1.

Structure results based on Δk approach. The number of subpopulations is listed on x-axis and Δk is listed on y-axis.

Figure 2.

NJ tree of the concatenated 13 loci. Only bootstrap>80% are indicated in the NJ tree.

The two subpopulations were strongly differentiated based on an average Fst value of 0.29 and a significant Hudson Snn statistic at ten loci (0.001<P<0.05). Collectively, these results suggested the genotypes were representative of the two presumed ancestral gene pools of wild common bean. A total of 34 shared polymorphisms were observed between the two subpopulations. Fixed polymorphisms were not found within these subpopulations (Table 4). The number of unique polymorphisms in the Middle American subpopulation (43) is higher than for the Andean subpopulation (29).

Table 4. Population differentiation data for the two gene pools.

| Loci | Fst | Significance of Snn | Shared | Fixed |

Unique sites |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| And | MA | |||||

| g1224 | 0.05 | NS | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| g680 | 0.30 | * | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| g2218 | 0.40 | *** | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| g1375 | 0.30 | *** | 3 | 0 | 6 | 5 |

| CV533374 | 0.61 | *** | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| g1159 | 0.04 | NS | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| g2129 | 0.19 | ** | 10 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| g776 | 0.08 | * | 1 | 0 | 2 | 11 |

| D1468 | 0.26 | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| g2393 | 0.35 | * | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| g634 | 0.32 | NS | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| g1661 | 0.48 | ** | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| g1215 | 0.41 | ** | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mean | 0.29 | |||||

Abbreviations: And, Andean; MA, Middle-America; NS, non significant.

*0.01<P<0.05; **0.001<P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

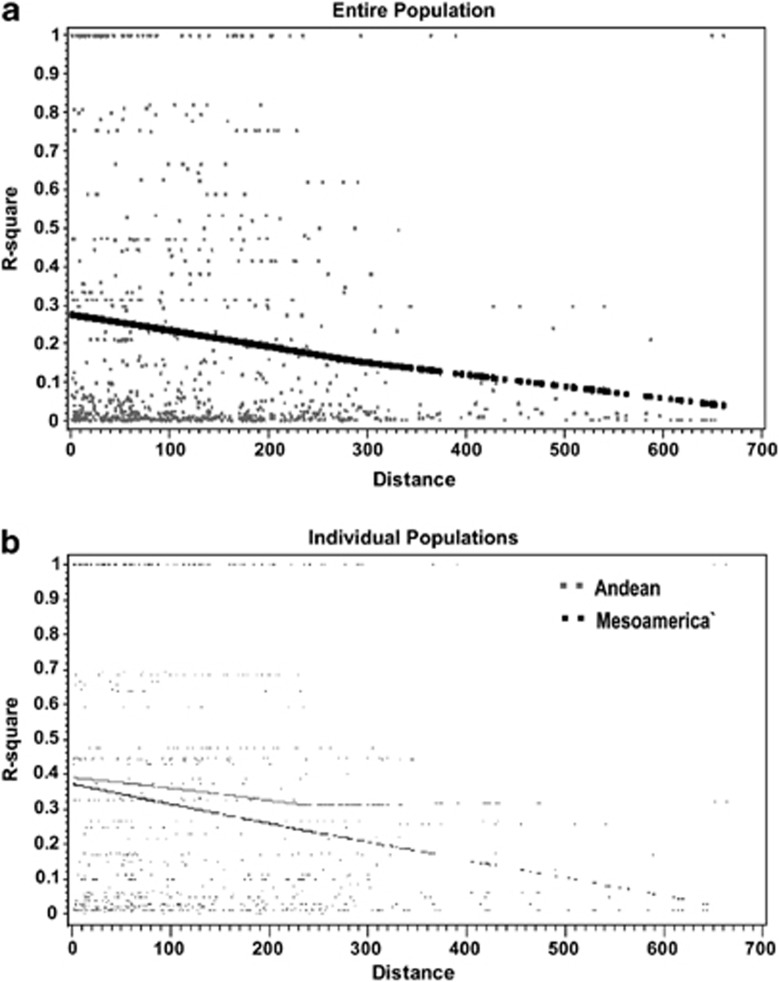

Nucleotide diversity of the entire population

A total of 106 segregating silent sites were observed among all genotypes for all loci (Table 3). The number of haplotypes varied between 3 and 16 for the silent sites with an average of 6.36. The average haplotype diversity across all the samples was 0.647. Within various loci, the Watterson's estimate (θsil) for the silent sites varied between 0.0044 and 0.0394 with an average of 0.0109. Nucleotide polymorphism at silent sites (πsil) averaged 0.0097 and ranged from 0.0036 to 0.0354. Except for loci g1159 and g634, the ratio of πnonsyn/πsyn was less than one with an average of 0.372. Tajima's D is significant only for locus g776 (P<0.05) and slightly negative for the majority of the loci. For the complete population, the multilocus HKA test of neutrality was not significant (P=0.9765). Among the loci, the minimum number of recombination events (Rm) varied between 0 and 4 with an average of less than one event per locus. The average r2 value (Zns) is 0.175. For the entire population, LD decayed to r2=0.1 within ∼500 bp (Figure 3a). Using the Fishers exact test, the percentage of significant LD pairwise comparisons was 7% when the Bonferroni correction was applied. Based on the significant correlation (P<0.0001) between silent diversity and interspecific divergence (θsil and Ksil; Zhu et al., 2007), the populations were considered to be under neutral equilibrium. A similar positive correlation was observed between segregating sites and the number of haplotypes (P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Decay of linkage disequilibrium with distance. Solid lines indicate the non-parametric regression and the dots indicate the raw r2 values plotted against distance. In (a), the line indicates the whole population, and in (b) the black represents Middle America and gray represents Andean.

Nucleotide diversity of individual gene pools

The Middle American gene pool contained 77 silent segregating sites, whereas the Andean gene pool had 63 (Table 3). The average number of Middle American haplotypes (4.29) is slightly higher than that of the Andean loci (3.43). The Middle American haplotype diversity (Hd=0.652) was greater than the Andean (Hd=0.447). The level of nucleotide diversity within the two gene pools was nearly identical among loci with an average θsil=0.0090 (πsil=0.0089) for the Middle American gene pool and θsil=0.0082 (πsil=0.0068) for the Andean gene pool. The ratio of πnonsyn/πsyn was less than 1, except for locus g634 within Middle American gene pool.

DT did not depart from neutral equilibrium expectations at any locus within either gene pool except locus g634 (P<0.05) in the Andean gene pool (Table 3). DT values are negative in majority of the loci (7 and 11 loci in both gene pools). The multilocus HKA test was not significant within either the Middle American gene pool (P=0.9732) or Andean gene pool (P=0.9884). The strong positive correlations between θsil and Ksil (P<0.0001), and between segregating sites and the number of haplotypes (P<0.0001) further support the conclusion that these populations do not deviate from neutral equilibrium.

The average r2 value for the Andean gene pool (Zns=0.464) is greater than Middle American gene pool (Zns=0.272). The minimum number of recombination events (Rm) for most loci was 0. In the Middle American gene pool, LD decay was within 500 bp (r2=0.1), whereas in the Andean gene pool, the decay was within 250 bp (r2∼0.3) (Figure 3b). Finally, using the Fishers exact test, only 0.2% pairwise comparisons were significant when Bonferroni correction was applied.

Demography estimation

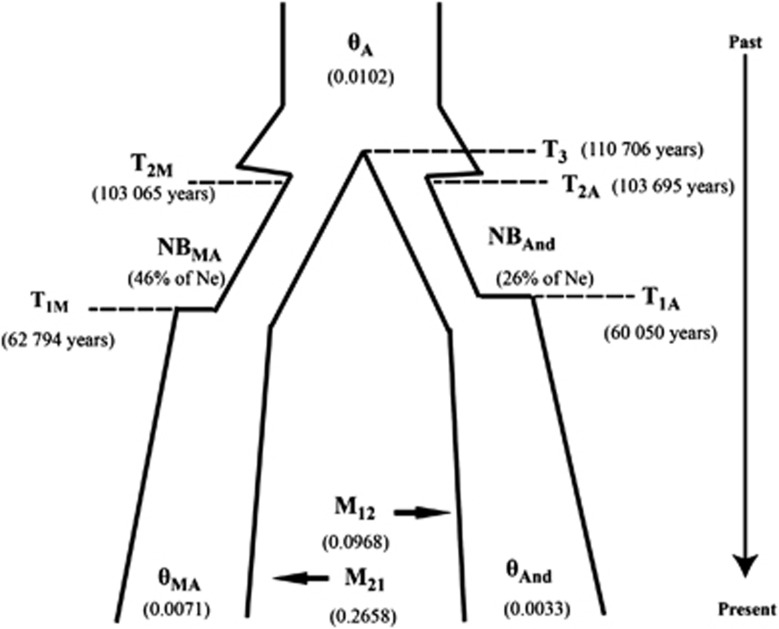

Given that population differentiation was best explained by a geographic distribution and no fixed sites were observed between the two gene pools, a parapatric model with a recent divergence was assumed to best define the evolution of wild common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Such a model includes an ancestral population as the initial source of the variation from which the two wild gene pools were derived. And given the geographic proximity of the two gene pools, gene flow between the two was expected. Based on these assumptions, several population parameters were estimated using MIMAR for this model. First the divergence time between the two gene pools was ∼111 000 years ago (95% CI: 55 931–196 101; Table 2; Figure 4; Supplementary Figure 1). θ for the ancestral population was calculated to be 0.0102 (95% CI: 0.0059–0.0165), which is equivalent to an effective population size of ∼220 000 individuals (based on a mutation rate of 6.1 × 10−9 synonymous substitutions per generation for vascular plants (Lynch and Conery, 2000) and calculated using θ=4 Nμ and then scaled to Ne=N(2−s)/2 (Nordborg and Donnelly, 1997) where s is the selfing rate, which is estimated to be 93% (Ibarra-Perez et al., 1997). Similarly, θ for the Middle American gene pool is 0.0071 (95% CI: 0.0025–0.0194), whereas for Andean gene pool, it is 0.0033 (95% CI: 0.0014–0.0150). Asymmetric migration rates (4 Nem) of 0.2658 from Andean to Middle American population and 0.0968 from Middle American to Andean were estimated (Figure 3, Table 3). Using these population parameter estimates, the results from 10 000 simulations were analyzed using MIMARgof to test the accuracy of the estimated IM model parameters. The standard IM model gave a reasonably good fit for SAnd, SMA, Ss and Sf, π and Fst, for both populations, but the fit for Andean DT was poor (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Parameter estimates for the wild gene pools of Phaseolus vulgaris.

Based on the negative DT, which suggests population expansion, we included a population bottleneck followed by an exponential growth to the present sizes of two wild subpopulations. Using the Approximate Bayesian Computation pipeline, we separately estimated that the Andean and Middle American bottlenecks started at ∼103 000 years ago and ended ∼62 000 years ago. The start time of bottleneck is similar to the divergence time estimated above. The Andean bottleneck population size was equivalent to 26% of the ancestral population (95% CI: 14.15–38.42), whereas the Middle American bottleneck population size was equivalent to 46% of the ancestral population (95% CI: 35.17–67.54; Figure 4). Then using the divergence time and migration estimates from first step, bottleneck times and population sizes from second step, the simulations give a reasonable fit for the summary statistics tested, that is, the observed statistics lie between the 95% CI of simulations.

Discussion

Diversity and demography of wild common bean

Common bean is diverse crop best known for its variation in seed size, seed shape, seed coat color and patterns (McClean et al., 2002), which collectively define the various market classes of beans we consume. Both wild types and landraces of the species form the core germplasm base available to the breeders. Wild genotypes of P. vulgaris were previously the subject of multiple marker analyses (Gepts et al., 1986; Koenig and Gepts, 1989; Gepts and Debouck, 1991; Khairallah et al., 1992; Becerra Velasquez and Gepts, 1994; Freyre et al., 1996; Tohme et al., 1996; Kwak and Gepts, 2009; Rossi et al., 2009) and only recently has multilocus gene sequence data been used to evaluate its diversity (Bitocchi et al., 2012). Here we collected sequence data for 13 loci distributed across the common bean genome from a diverse group of genotypes representing the two major gene pools, and from that data assessed nucleotide diversity, population differentiation and for the first time demographic parameters for the wild form of the species. These results have implications regarding the origins of wild populations that were the source of variation used during the domestication events (Mamidi et al., 2011).

A combination of STRUCTURE and NJ tree analysis defined two subpopulations that correspond to the two wild-type gene pools. The geographic composition of the subpopulations were consistent with that described in previous studies (Gepts et al., 1986; Koenig and Gepts, 1989; Gepts and Debouck 1991; Khairallah et al., 1992; Becerra Velasquez and Gepts 1994; Freyre et al., 1996; Tohme et al., 1996; Rossi et al., 2009), and Fst estimates indicate a moderate to high level of population differentiation. These Fst estimates are higher than those found for cross-pollinated species (Ingvarsson, 2005; Arunyawat et al., 2007) and other self-pollinated species (Wright et al., 2003), and are most likely due to the self-pollinating nature of the species by which the amount of diversity contributed by the migrants is less than that in a cross-pollinated species (Ness et al., 2010). Significant Hudson's Snn values for the majority of loci further confirmed the presence of significant differentiation between the two gene pools.

Low levels of nucleotide variation among the wild genotypes (πsil=0.0097) and within each gene pool (πsil-MA=0.0089; πsil-And=0.0068) also reflect the self-pollinating nature of P. vulgaris. This is consistent with the concepts of Charlesworth (2003), who suggested that low levels of genetic variation within self-pollinating species is due to a low effective population size and a low effective rate of recombination. The level of nucleotide variation observed for these wild populations is comparable to that for the wild form of some other self-pollinated crop species (Wright and Gaut, 2005; Liu and Burke, 2006; Arunyawat et al., 2007; Zhang and Ge, 2007; Zhu et al., 2007) and greater than that found in wild rice (Zhu et al., 2007). One reason for the low levels of nucleotide variation may be introgression from cultivated domesticated beans as reported recently (Papa et al., 2005). Finally, the fact that the nucleotide diversity at silent sites for the entire population is greater than that of individual subpopulations supports the existence of population structure (Moeller et al., 2007).

The nucleotide diversity of the Middle American gene pool was slightly higher than that of Andean gene pool yet not as great as observed previously for individual loci (McClean et al., 2004; McClean and Lee, 2007). Differences in nucleotide diversity among populations can be attributed to differences in population size, the number of immigrants and genotypic contributions to the migrant pool (Wakeley, 2001). Consistent with these suggestions, we observed a greater number of migrants entering the Middle American gene pool. In addition to greater nucleotide diversity, the Middle American gene pool had a higher level of haplotype diversity, a population feature attributed to a larger effective population size. The results of the IM model simulations were consistent with this expectation of a larger Middle American effective population size.

Other than a single locus (g634 in the Middle-America gene pool), the DT estimates were generally negative for the other loci in the two gene pools. This suggests an excess of singletons in the gene pools that can be attributed to the interplay between population structure and demography (Arunyawat et al., 2007), population expansion (Zhu et al., 2007; Städler et al., 2009) and/or due to population subdivision (Ingvarasson, 2005; Moeller et al., 2007). Based on the neutrality tests, and the correlations between θsil and Ksil, and between S and H, it appears that selection is not acting on most of these loci. The locus D1468, which maps near a domestication locus, has the same level of diversity as other loci, whereas g776, an alcohol dehydrogenase locus, which maps near D1468, has a significant DT value (P<0.5) indicating it is evolving by different evolutionary or demographic forces, possibly purifying selection.

We estimate the present-day population sizes of the Middle American and Andean gene pools are about 70% and 32% of the ancestral population, respectively. We also determined that the divergence time of the two gene pools at ∼111 000 years ago, a date more recent than the ∼500 000 years ago estimate based on alpha-amylase inhibitor and internal transcribed spacer sequence data (reviewed in Kwak and Gepts (2009)). These estimates could be biased if the ancestral gene pool was structured or if migrants were entering that population (Becquet and Przeworski, 2009; Strasburg and Rieseberg, 2010). Given that P. vulgaris and P. coccineus, common bean's closest species, diverged at about ∼1.3–2.5 million years ago (Matt Lavin, personal communication), it is unlikely that in-migration from such a diverged species affected nucleotide diversity of the ancestral wild common bean population. In addition, recent analyses determined the wild Andean and Middle American gene pools were derived from a mostly unstructured ancestral population located in Mexico (Bitocchi et al., 2012). Although these observations add credence to our demographic estimates, it should be noted that the sensitivity of demography parameter estimates to the assumption of population structure is not clear (Hey 2006; Strasburg and Rieseberg, 2008).

As observed for wild relatives in other crop species (Muraya et al., 2010), our simulations determined that the ancestral wild population of common bean underwent bottlenecks associated with the development of the wild Andean and Middle American wild gene pools. Although a bottleneck in the Andean wild gene pool has been detected previously (Rossi et al., 2009; Bitocchi et al., 2012), our analysis for the first time also detected a bottleneck associated with the development of the Middle American wild gene pool. Although the direct consequences of the bottleneck are to decrease genetic diversity, increase rates of inbreeding and fix mildly deleterious alleles (reviewed in Muraya et al. (2010)), these factors did not have the same intensity for the wild Andean and Middle American gene pools. For example, although the duration of the bottleneck was similar for the two gene pools, the intensity of the bottleneck was less for the Middle American gene pool. This was directly reflected by difference in the diversity for the two wild gene pools. This is consistent with recent observations relative to the origin of the two wild gene pools and their subsequent adaptations to the ecosystems in Mexico, Central America and South America. Based on the close relationship between wild Andean and Middle American genotypes from central Mexico, Bitocchi et al. (2012) proposed the ancestral gene pool of common bean was located in central Mexico in a region bordered by the Sierra Madre Occidental, the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Transverse Volcanic Axis. They also observed wild Middle American subpopulations in North/Central Mexico, along the Mexican Pacific Coast and extending into Central America, and along the South/Central Mexican region bordering the Caribbean Sea. It would be expected from these and our observations that the Middle American gene pool would be more diverse to allow for adaptation to such a broad geographic and climatic area. Finally, an expansion in population size following the bottleneck was a critical parameter in explaining the current diversity levels. This was reflected by the negative DT values for both the wild gene pools.

Several observations suggest migration is occurring between the gene pools. With no fixed sites and many shared sites, it can be suggested that the subpopulations were recently diverged and migration was necessary. Also, ongoing migration was supported by the observation that the sum of haplotypes within each gene pool was greater than when the genotypes were evaluated as a single population. Asymmetric levels of gene flow are common between recently formed species (Hey, 2006; Zhou et al., 2008), and gene flow has been observed for many other wild ancestors of plant species (Stadler et al., 2008; Ross-Ibarra et al., 2009). Although modest in size, we did observe gene flow with a higher migration rate from the Andean to the Middle American gene pool. The gene flow (4Nem) estimated here is consistent with other species (Morjan and Rieseberg, 2004), which ranges from 0.02 to 90.4, with a mean of 1.8 and a median of 1.1. Further investigations into this variation in migration rates using genome-wide scans may provide clues to the genetic or genomic basis of differences and similarities of the two gene pools brought on by reproductive isolation and occasional migration events (Machado et al., 2007).

The differential effects of the bottleneck upon the gene pools was also reflected by the result that the average LD coefficient (Zns) estimate was higher for the Andean gene pool, a result consistent with earlier results (Rossi et al., 2009). The differential level of LD may reflect the differences in haplotype diversity between the two gene pools. In contrast to the LD results, recombination (as measured by Rm) was rare for most of the loci studied here. In the absence of recombination, other factors such as selection and effective population size may be modulating LD (Rafalski and Morgante, 2004). Although we cannot estimate LD or recombination rates at the chromosome level by evaluating a single locus per chromosome, we were able to determine that sufficient levels of diversity exist in common bean to search for diagnostic polymorphisms within or near candidate genes (Zhu et al., 2007) given a high density marker system.

Implications for association mapping (AM)

AM has the advantage of exploiting all the recombination events that have occurred in the evolutionary history of a sample and results in a higher mapping resolution compared with family mapping (Myles et al., 2009). The success of AM is related to the extent of LD with a population sample. With the increased use of AM to discover quantitative trait loci (QTL), it is necessary to understand the different factors that affect LD. The resolution with which a QTL can be mapped is a function of LD decay over distance. Differences in the extent of LD have a very important effect on the marker density required for association mapping. In association mapping, the price of higher LD is lower resolution. Among the different factors that affect LD, demographic parameters have a profound influence. As the majority of neutral genetic variation present in domesticated crops arose in their wild populations by mutations and genetic drift to present-day allele frequencies (Hamblin et al., 2011), it becomes necessary to study the demographic parameters of wild types that shaped the present-day landraces and cultivars.

Effective population size (Ne) is an important parameter in population genetics because it is inversely proportional to the rate of genetic drift (reviewed in Hamblin et al. (2011)). A larger effective population size would lead to more recombination events, and recombinant chromosomes are lost more slowly. Thus, larger populations are expected to have lower levels of LD (Hamblin et al., 2011). Self-pollinated plants are highly homozygous and rarely generate new haplotypes via recombination. When a very large population exists over many generations, rare outcrossing events can maintain linkage equilibrium. Bottlenecks, as observed for wild common bean here, reduce variation and change the frequency spectrum by removing low-frequency alleles (Hamblin et al., 2011). Bottlenecks also increase the extent of LD by eliminating recombinant lineages resulting in extensive haplotype structure, which is more pronounced in self-pollinating crops. Differential rates of LD can occur across the genome because selection reduces variation locally relative to that found throughout the genome (Myles et al., 2009). The strong population structure in many crops presents both challenges and opportunities for association mapping. It is a source of allelic diversity, which can be used to discover QTL regions through use of admixed populations. On the other hand, population structure generates spurious associations between phenotypes and unlinked markers. Although mixed models include factors that account for population structure, these corrections reduce our ability to detect true positives (Brachi et al., 2010).

In P. vulgaris, population structure arose in wild types ∼110 000 years ago followed by a bottleneck within each wild gene pool before domestication. Later, a domestication bottleneck reduced diversity and increased the population structure (Mamidi et al., 2011). This was followed by differentiation of domestication populations into races and intense selection by breeders. All these would lead to higher LD in present-day cultivar populations. As a result of the selfing mating system, an insufficient amount of time has passed to break up the LD generated by the bottleneck (Myles et al., 2009; Hamblin et al., 2011). Even though high LD is beneficial to detect QTL with high probability, fine mapping a causal variant is difficult, as multiple markers around the QTL have same strength of detection (Astle and Balding, 2009). With this it can be suggested that association mapping P. vulgaris should be performed independently for each gene pool. As the bottleneck and selection effects are different for each gene pool, AM in each gene pool will be necessary to detect the causal variants in P. vulgaris.

Data archiving

Sequence data have been submitted to the NCBI Genome Survey Sequences Database: accession numbers JY123505–JY123801.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Heredity website (http://www.nature.com/hdy)

Supplementary Material

References

- Acosta-Gallegos JA, Kelly JD, Gepts P. Prebreeding in common bean and use of genetic diversity from wild germplasm. Crop Sci. 2007;47:S44–S59. [Google Scholar]

- Arunyawat U, Stephan W, Stadler T. Using multilocus sequence data to assess population structure, natural selection, and linkage disequilibrium in wild tomatoes. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2310–2322. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astle W, Balding DJ. Population structure and cryptic relatedness in genetic association studies. Stat Sci. 2009;24:2310–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra Velasquez VL, Gepts P. RFLP diversity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) in its centers of origin. Genome. 1994;37:256–263. doi: 10.1139/g94-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becquet C, Przeworski M. A new approach to estimate parameters of speciation models with application to apes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1505–1519. doi: 10.1101/gr.6409707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becquet C, Przeworski M. Learning bout modes of speciation by computational approaches. Evolution. 2009;63:2547–2562. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitocchi E, Nanni L, Rossi M, Giardini A, Zeuli PS, Logozzo G, et al. The Mesoamerican origin of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is revealed by sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E788–E796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108973109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachi B, Faure N, Horton M, Flahauw E, Vazquez A, Nordborg M, et al. Linkage and association mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana flowering time in nature. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady L, Bassett MJ, McClean PE. Molecular markers associated with T and Z, two genes controlling partly colored seed coat patterns in common bean. Crop Sci. 1998;38:1073–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D. Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 2003;358:1051–1070. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Källman T, Gyllenstrand N, Lascoux M. New insights on the speciation history and nucleotide diversity of three boreal spruce species and a tertiary relict. Heredity. 2010;104:3–14. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyre R, Ríos R, Guzmán L, Debouck DG, Gepts P. Ecogeographic distribution of Phaseolus spp.(Fabaceae) in Bolivia. Econ Bot. 1996;50:195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P, Bliss FA. Phaseolin variability among wild and cultivated common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) from Colombia. Econ Bot. 1986;40:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P, Debouck D.1991Origin, domestication, and evolution of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.)In: Van Schoonhoven A, Voysest O (eds)Common Beans: Research for Crop Improvement CAB Int: Wallingford, UK and CIAT: Cali, Colombia; 7–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P, Osborn TC, Rashka K, Bliss FA. Phaseolin-protein variability in wild forms and landraces of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris): evidence for multiple centers of domestication. Econ Bot. 1986;40:451–468. [Google Scholar]

- Graham P, Vance C. Legumes: importance and constraints to greater use. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:872–877. doi: 10.1104/pp.017004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin MT, Buckler ES, Jannink JL. Population genetics of genomics-based crop improvement methods. Trends Genet. 2011;27:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haudry A, Cenci A, Ravel C, Batallion T, Brunel D, Poncet C, et al. Grinding up wheat: a massive loss of nucleotide diversity since domestication. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1506–1517. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey J. Recent advances in assessing gene flow between diverging populations and species. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:592–596. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. A new statistic for detecting genetic differentiation. Genetics. 2000;155:2011–2014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:337–338. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR, Kaplan NL. Statistical properties of the number of recombination events in the history of a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics. 1985;111:147–164. doi: 10.1093/genetics/111.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR, Kreitman M, Aguade M. A test of neutral molecular evolution based on nucleotide data. Genetics. 1987;116:153–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/116.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR, Slatkin M, Maddison WP. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics. 1992;132:583–589. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.2.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Perez FJ, Ehdaie B, Waines JG. Estimation of outcrossing rate in common bean. Crop Sci. 1997;37:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson P. Multilocus patterns of nucleotide polymorphism and the demographic history of Populus tremula. Genetics. 2008;180:329–340. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson PK. Nucleotide polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium within and among natural populations of European aspen (Populus tremula L., Salicaceae) Genetics. 2005;169:945–953. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan L, Lynch TF. Phaseolus (Fabaceae) in Archaeology: AMS. Econ Bot. 1999;53:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Khairallah MM, Sears BB, Adams MW. Mitochondrial restriction fragment length polymorphisms in wild Phaseolus vulgaris L.: insights on the domestication of the common bean. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;84:915–922. doi: 10.1007/BF00227404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian B, Ozkan H, Walther A, Kohl J, Dagan T, Salamini F, et al. Molecular diversity at 18 loci in 321 wild and 92 domesticate lines reveal no reduction of nucleotide diversity during Triticum monococcum (Einkorn) domestication: implications for the origin of agriculture. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2657–2668. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig R, Gepts P. Allozyme diversity in wild Phaseolus vulgaris: further evidence for two major centers of genetic diversity. Theor Appl Genet. 1989;78:809–817. doi: 10.1007/BF00266663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak M, Gepts P. Structure of genetic diversity in the two major genepools of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L., Fabaceae) Theor Appl Genet. 2009;118:979–992. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leman SC, Chen Y, Stajich JE, Noor MAF, Uyenoyama MK. Likelihoods from summary statistics: recent divergence between species. Genetics. 2005;171:1419–1436. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger C, Wegmann D. Bayesian computation and model selection without likelihoods. Genetics. 2010;184:243–252. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Burke JM. Patterns of nucleotide diversity in wild and cultivated sunflower. Genetics. 2006;173:321–330. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.051110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes JS, Boessenkool S. The use of approximate Bayesian computation in conservation genetics and its application in a case study on yellow-eyed penguins. Conserv Genet. 2010;11:421–433. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Conery J. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado CA, Haselkorn TS, Noor MAF. Evaluation of the genomic extent of effects of fixed inversion differences on intraspecific variation and interspecific gene flow in Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis. Genetics. 2007;175:1289–1306. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamidi S, Rossi M, Annam D, Moghaddam S, Lee RK, Papa R, et al. Investigation of the domestication of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) using multilocus sequence data. Funct Plant Biol. 2011;38:953–967. doi: 10.1071/FP11124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean P, Lee R, Miklas P. Sequence diversity analysis of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase intron 1 in common bean. Genome. 2004;47:266–280. doi: 10.1139/g03-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean PE, Burridge J, Beebe S, Rao IM, Porch TG. Crop improvement in the era of climate change: an integrated, multi-disciplinary approach for common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Funct Plant Biol. 2011;38:927–933. doi: 10.1071/FP11102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean PE, Lee RK. Genetic architecture of chalcone isomerase non-coding regions in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Genome. 2007;50:203–214. doi: 10.1139/g07-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean PE, Lee RK, Otto C, Gepts P, Bassett MJ. Molecular and phenotypic mapping of genes controlling seed coat pattern and color in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) J Hered. 2002;93:148–152. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M, Mamidi S, Lee R, Chikara S, Rossi M, Papa R, et al. Syntenic relationships among legumes revealed using a gene-based genetic linkage map of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2010;121:1103–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller DA, Tenaillon MI, Tiffin P. Population structure and its effects on patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in teosinte (Zea mays ssp. parviglumis) Genetics. 2007;176:1799–1809. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.070631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina J, Sikora M, Garud N, Flowers JM, Rubinstein S, Reynolds A, et al. Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:8351–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104686108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morjan CL, Rieseberg LH. How species evolve collectively: implications of gene flow and selection for the spread of advantageous alleles. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:1341–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell PL, Lundy KE, Clegg MT. Distinct geographic patterns of genetic diversity are maintained in wild barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp. Spontaneum) despite migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10812–10817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633708100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraya MM, Sagnard F, Parzies HK. Investigation of recent population bottlenecks in Kenyan wild sorghum populations (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench ssp. verticilliflorum (Steud.) De Wet) based on microsatellite diversity and genetic disequilibria. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2010;57:995–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Myles S, Peiffer J, Brown PJ, Ersoz ES, Zhang Z, Costich DE, et al. Association mapping: critical considerations shift from genotyping to experimental design. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2194–2202. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness RW, Wright SI, Barrett SCH. Mating-system variation, demographic history and patterns of nucleotide diversity in the tristylous plant Eichhornia paniculata. Genetics. 2010;184:381–392. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.110130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordborg M, Donnelly P. The coalescent process with selfing. Genetics. 1997;146:1185–1195. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa R, Acosta J, Delgado-Salinas A, Gepts P. A genome-wide analysis of differentiation between wild and domesticated Phaseolus vulgaris from Mesoamerica. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111:1147–1158. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyhajarvi T, Garcia-Gil MR, Knurr T, Mikkonen M, Wachowiak W, Savolainen O. Demographic history has influenced nucleotide diversity in European Pinus sylvestris populations. Genetics. 2007;177:1713–1724. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.077099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafalski A, Morgante M. Corn and humans: recombination and linkage disequilibrium in two genomes of similar size. Trends Genet. 2004;20:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington DL, Thornsberry JM, Matsuoka M, Wilson LM, Whitt SR, Doebley J, et al. Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11479–11484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201394398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Ibarra J, Tenaillon M, Gaut BS. Historical divergence and gene flow in the genus Zea. Genetics. 2009;181:1399–1413. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.097238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Bitocchi E, Bellucci E, Nanni L, Rau D, Attene G, et al. Linkage disequilibrium and population structure in wild and domesticated populations of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Evol Appl. 2009;2:504–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2009.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Rozas R. DnaSP version 3: an integrated program for molecular population genetics and molecular evolution analysis. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:174–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid KJ, Ramos-Onsins S, Ringys-Beckstein H, Weisshaar B, Mitchell-Olds T. A multilocus sequence survey in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a genome-wide departure from a neutral model of DNA sequence polymorphism. Genetics. 2005;169:1601–1615. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP. Broadening the genetic base of common bean cultivars: a review. Crop Sci. 2001;41:1659–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Nodari R, Gepts P. Genetic diversity in cultivated common bean: I. Allozymes. Crop Sci. 1991;31:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Staden R. The Staden sequence analysis package. Mol Biotechnol. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler T, Arunyawat U, Stephan W. Population genetics of speciation in two closely related wild tomatoes (Solanum section Lycopersicon) Genetics. 2008;178:339–350. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburg JL, Rieseberg LH. Molecular demographic history of the annual sunflowers Helianthus annuus and H. petiolaris—large effective population sizes and rates of long-term gene flow. Evolution. 2008;62:1936–1950. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburg JL, Rieseberg LH. How robust are ‘Isolation with Migration' analyses to violations of the IM model? A simulation study. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:397–310. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Städler T, Haubold B, Merino C, Stephan W, Pfaffelhuber P. The impact of sampling schemes on the site frequency spectrum in non-equilibrium subdivided populations. Genetics. 2009;182:205–216. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon MI, U'Ren J, Tenaillon O, Gaut BS. Selection versus demography: a multilocus investigation of the domestication process in maize. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1214–1225. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin P, Gaut BS. Molecular evolution of the wound-induced serine protease inhibitor wip1 in Zea and related genera. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:2092–2101. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohme J, Gonzalez D, Beebe S, Duque MC. AFLP analysis of genepools of a wild bean core collection. Crop Sci. 1996;36:1375–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeley J. The coalescent in an island model of population subdivision with variation among demes. Theor Popul Biol. 2001;59:133–144. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2000.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeley J, Hey J. Estimating ancestral population parameters. Genetics. 1997;145:847–855. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SI, Gaut BS. Molecular population genetics and the search for adaptive evolution in plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:506–519. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SI, Lauga B, Charlesworth D. Subdivision and haplotype structure in natural populations of Arabidopsis lyrata. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:1247–1263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LB, Ge S. Multilocus analysis of nucleotide variation and speciation in Oryza officinalis and its close relatives. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:769–783. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HF, Zheng XM, Wei RX, Second G, Vaughan DA, Ge S. Contrasting population genetic structure and gene flow between Oryza rufipogon and Oryza nivara. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117:1181–1189. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Zheng X, Luo J, Gaut BS, Ge S. Multilocus analysis of nucleotide variation of Oryza sativa and its wild relatives: severe bottleneck during domestication of rice. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:875–888. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.