Background: Polo-like kinase1 (Plk1) activation is inhibited in response to DNA damage, and this inhibition contributes to the activation of the G2/M checkpoint.

Results: ATR phosphorylates Bora, leads to its degradation, and inhibits Plk1 activity after DNA damage.

Conclusion: Degradation of Bora activates the G2/M checkpoint through Plk1.

Significance: Learning how Polo-like kinase1 (Plk1) activation is inhibited in response to DNA damage.

Keywords: Cell Biology, Cell Cycle, Checkpoint Control, DNA Damage Response, Protein Degradation

Abstract

Polo-like kinase1 (Plk1) activation is inhibited in response to DNA damage, and this inhibition contributes to the activation of the G2/M checkpoint, although the molecular mechanism by which Plk1 is inhibited is not clear. Here we report that the DNA damage signaling pathway inhibits Plk1 activity through Bora. Following UV irradiation, ataxia telangiectasia-mutated- and Rad3-related protein phosphorylates Bora at Thr-501. The phosphorylated Thr-501 is subsequently recognized by the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCF-β-TRCP, which targets Bora for degradation. The degradation of Bora compromises Plk1 activation and contributes to DNA damage-induced G2 arrest. These findings shed new light on Plk1 regulation by the DNA damage response pathway.

Introduction

Plk1 is a multi-functional protein controlling many processes in the cell cycle, including centrosome maturation, bipolar spindle formation, sister chromatid cohesion, activation of anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome, control of cleavage furrow formation, and mitotic entry (1, 2). Plk1 promotes mitotic entry by inhibiting Wee1 (3), activating Cdc25 (4, 5) and inducing cyclin B nuclear import (6), which, in turn, activates cyclin B/Cdk1. Plk1 itself is activated by phosphorylation in its activation loop (Thr-210 in mammals) (4, 7–9). The mechanism responsible for Thr-210 phosphorylation has been elusive until two recent reports demonstrated that Bora cooperates with Aurora A to promote Plk1 phosphorylation at Thr-210 and Plk1 activation (10, 11).

Plk1 has also been shown to be a critical target of the DNA damage response pathway. In response to DNA damage, Plk1 activity is inhibited in an ataxia telangiectasia-mutated/ATR-dependent3 manner, and overexpression of constitutively active Plk1 overrides the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint (12–14). These findings suggest that inhibition of Plk1 is an important mechanism for activation of the G2/M checkpoint. Although Plk1 was speculated to be a direct target of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated /ATR-mediated signaling, the molecular mechanism of Plk1 inhibition remains unclear. Here we show that DNA damage leads to the phosphorylation of Bora by ATR, which is subsequently targeted for proteasome-mediated degradation. The resulting reduction in Bora protein levels causes inhibition of Plk1 and G2 arrest.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

S/FLAG/streptavidin-binding peptide-tagged Bora was cloned into pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech). The Bora T501A mutant and Bora shRNA-resistant constructs were generated with a PCR-based mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

Antibody and Chemicals

Bora antibody was raised by immunizing rabbit with N-terminal (1–210) Bora-GST fusion protein. pT501 Bora antibody was raised by using the phosphopeptide CMDSGYNpTQN.

Other antibodies used were anti-Bora (Epitomics), anti-FLAG (M2) (Sigma), β-actin antibody (Sigma), phospho-SQ/TQ antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), β-TRCP antibody (Invitrogen), Chk1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), Chk1-pS317 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), ATR antibody (Genetex), Plk1-pT210 antibody (BD Biosciences), Plk1 antibody (Invitrogen), and phospho-H3 antibody (Abcam). The chemicals used were MG132 (Sigma) and ON01910 (a gift from Dr. Zheng Fu, Virginia Commonwealth University).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

mRNA was extracted with a PARIS kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out with a one-step Brilliant II SYBR Green QRT-PCR Master Mix kit (Agilent Technologies). Primers of human Bora and GAPDH were purchased from Qiagen. Bora mRNA expression levels were calculated on the basis of the 2−ΔCt value normalized to GAPDH.

Cell Culture

293T, H1299, A549, and U2OS were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in 5% CO2. For the cell cycle, cells were fixed with cold 70% (v/v) ethanol, stained with propidium iodide, and then run on the fluorescence activated cell sorter machine.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed with NETN buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) containing 50 mm glycerophosphate, 10 mm NaF, and protease inhibitor mixture on ice for 20 min. The cell lysates were obtained by centrifugation and then incubated with anti-FLAG beads (M2, Sigma) or protein A beads bound to anti-Bora antibody for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunocomplexes were then washed with NETN buffer three times and separated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed following standard procedures. Band intensity was quantified by ImageJ analysis (National Institutes of Health).

RNA Interference

Bora shRNAs (NM_024808.2), β-TRCP shRNA (NM_003939.2), and ATR shRNA (NM_001184) were purchased from Sigma. The Bora shRNA target sequence was as follows: GCTTAAGAGTTCCTCGCATAT (targeted to the 3′ UTR of Bora mRNA). The β-TRCP shRNA target sequence was as follows: GCGTTTCAATAATGGCATGAT, GCGTTGTATTCGATTTGATAA, CCATTAAAGTTGCGGTATTTA, GCACATAAACTCGTATCTTAA, GCTGAACTTGTGTGCAAGGAA. The ATR shRNA target sequence was as follows: GCCGCTAATCTTCTAACATTA, GCCAAAGTATTTCTAGCCTAT, CTGTGGTTGTATCTGTTCAAT. Lentiviruses of Bora, β-TRCP, and ATR shRNAs were made according to the protocol of the manufacturer.

Immunofluorescence

Bora knockdown U2OS cells were plated on glass coverslips and transfected with the indicated constructs. 48 h after transfection, cells were left untreated or treated with UV radiation (20 J/m2). After the indicated time, cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and then stained with phospho-H3 antibody using the standard protocol.

Statistics

Experiments with three replicates were carried out, and statistical analyses were performed by two-tailed Student's t test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Degradation of Bora following DNA Damage

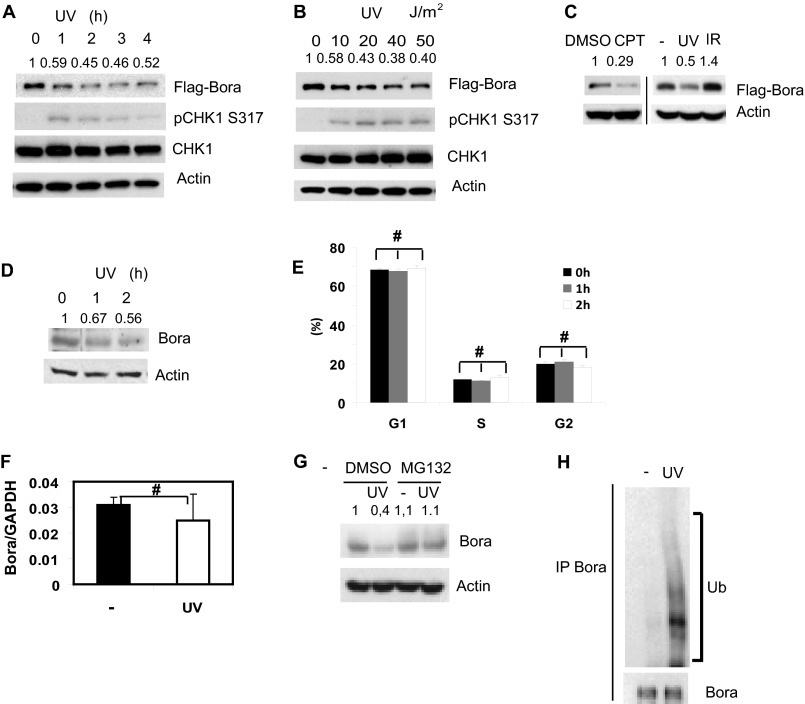

During our investigation of Bora, we unexpectedly found that Bora protein levels rapidly decreased after UV treatment (Fig. 1A). The decrease in Bora levels was both time- and dose-dependent (Fig. 1, A and B). To examine whether the decrease in Bora protein levels was a general response to genotoxic stresses, we used other DNA damage inducers. As shown in Fig. 1C, camptothecin (CPT) induced down-regulation of Bora protein. However, we did not observe a significance change in Bora level following ionizing radiation (IR), suggesting that the Bora level is regulated by replication stress. Our initial findings used epitope-tagged Bora (Fig. 1, A–C). We further confirmed these findings by examining the levels of endogenous Bora after DNA damage. As shown in Fig. 1D, endogenous Bora levels decreased with similar kinetics as those of recombinant Bora.

FIGURE 1.

Bora is degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner following DNA damage. A–C, 293T cells were transfected with a construct encoding FLAG-Bora. Cells were left untreated or treated with UV (20 J/m2), camptothecin (CPT, 1 μm), irradiation (IR, 10 gray). Cells were collected at indicated time (A) or 1 h (B and C) later and examined by immunoblot analysis. The pChk1s317 blot served as a positive control for UV treatment. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. D, 293T cells were U- irradiated, collected at the indicated time, and then endogenous Bora levels were examined with Bora antibody. E, 293T cells were UV-irradiated and fixed at the indicated time. Cell cycle distribution was determined by FACS. The results represent the mean values from three independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. #, p > 0.05. F, 293T cells were harvested 2 h post-UV radiation, mRNA was extracted, and Bora levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Error bars represent S.E. of n = 3. #, p > 0.05. G, 293T cells were pretreated with DMSO or 50 μm MG132 for 3 h and then treated with UV radiation. 2 h later, cells were harvested, and Bora levels were examined by Western blot analysis. H, 293T cells were pretreated with DMSO or 40 μm MG132 for 3 h and then treated with 20 J/m2 of UV radiation. Endogenous Bora ubiquitination (Ub) was then examined by immunoblot analysis. IP, immunoprecipitation.

We next examined the mechanism underlying DNA damage-induced Bora down-regulation. Because Bora levels change throughout the cell cycle (15, 16), it is possible that the apparent down-regulation of Bora is due to an indirect effect of cell cycle populations. However, the down-regulation of Bora occurred quickly (as early as 1 h) following DNA damage, whereas the overall cell cycle profile did not change significantly at this time (Fig. 1E). Therefore, it is unlikely that the change in Bora levels is due to a change in cell cycle populations. We also found that Bora mRNA levels did not change significantly following UV irradiation (Fig. 1F), suggesting that Bora down-regulation is regulated at the posttranscriptional level. Previous work has demonstrated that Bora is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and regulates mitotic exit (15, 16). It is possible that Bora protein levels are also regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway following DNA damage. To test this hypothesis, we pretreated cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. As shown in Fig. 1G, MG132 inhibited the UV-induced down-regulation of Bora. Furthermore, we observed increased Bora ubiquitination following UV irradiation (Fig. 1H). These results suggest that Bora is degraded through the proteasome-mediated pathway following DNA damage.

Phosphorylation of Bora at Thr-501 by ATR

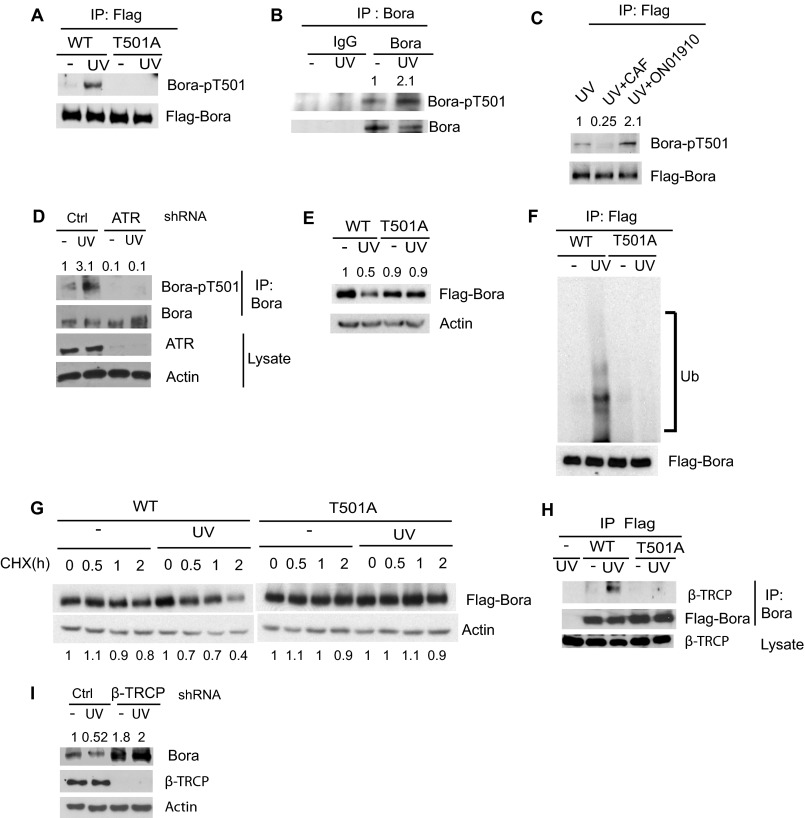

To investigate how Bora is regulated by the DNA damage response pathway, we first examined whether Bora could be phosphorylated following DNA damage. As shown in supplemental Fig. S1A, Bora was phosphorylated at the SQ/TQ motifs, which are ataxia telangiectasia-mutated/ATR consensus phosphorylation motifs. Among the possible SQ/TQ motifs of Bora, the TQ motif at amino acid 501 of Bora is the only conserved one from human to Xenopus (supplemental Fig. S2). To confirm that this site is phosphorylated after DNA damage, we generated a phosphospecific antibody against Thr-501. As shown in Fig. 2A, WT Bora was phosphorylated at Thr-501 following DNA damage, whereas mutation at Thr-501 (T501A) abolished Bora phosphorylation. We also confirmed that phosphorylation of endogenous Bora at Thr-501 was increased after UV irradiation (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, Thr-501 is localized at the DS497GXXT501 motif, which acts as a degron for Bora (16). Both Ser-497 and Thr-501 have been shown to be phosphorylated by Plk1 during mitosis, and the phosphorylation of Ser-497/Thr-501 is important for the binding of β-TRCP to Bora and subsequent Bora degradation during mitotic exit (16). However, the phosphorylation of Thr-501 following DNA damage does not require Plk1 because the Plk1 inhibitor ON01910 (17) had no effect on Thr-501 phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). Instead, the phosphorylation of Thr-501 following DNA damage required PI3K-like kinases because the pan-PI3K-like kinase inhibitor caffeine (18) inhibited Thr-501 phosphorylation of both ectopically expressed and endogenous Bora (Fig. 2C and supplemental Fig. S1B). Because ATR is an upstream PI3K-like kinase activated by replication stress, we down-regulated ATR and found that down-regulation of ATR significantly inhibited endogenous Bora phosphorylation at Thr-501 (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that ATR phosphorylates Thr-501 of Bora following UV radiation.

FIGURE 2.

Bora is phosphorylated by ATR at Thr-501, which targets Bora to β-TRCP-mediated degradation. A, 293T cells transfected with constructs encoding FLAG-WT Bora or T501A Bora (T501A) were irradiated with UV light, and 4 h later, cells were lysed and proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody and blotted with the indicated antibodies. B, 293T cells were treated with UV radiation (20 J/m2). 2 h later, cells were lysed, and endogenous Bora was immunoprecipitated with IgG or Bora antibody and then blotted with phosphorspecific Bora antibody. C, H1299 cells transfected with indicated constructs were pretreated with inhibitors for Plk1 (ON01910) or PI3K-like kinase (caffeine, CAF). Then, cells were UV-irradiated, and Bora phosphorylation was examined as in Fig. 2B. D, 293T cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding the indicated shRNAs. Cells were left untreated or irradiated. Bora was then immunoprecipitated and blotted with anti-pT501 Bora. E, WT and T501A Bora were transfected into 293T cells. Cells were treated with 20J/m2 of UV radiation and, 2 h later, blotted with the indicated antibody. F, 293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs, pretreated with 40 μm MG132 for 3 h, and then irradiated with 20 J/m2 of UV radiation. FLAG-Bora was immunoprecipitated and blotted with anti-Ub antibody (Ub). G, 293T cells transfected with the indicated constructs were left untreated or UV-irradiated (20 J/m2) with 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), and then cells were harvested at the indicated time. H, 293T cells transfected with the indicated constructs were left untreated or UV-irradiated (20 J/m2). The Bora-β-TRCP interaction was then examined by immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis. I, A549 cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding control or β-TRCP shRNA. 48 h later, cells were treated with 20 J/m2 of UV, and endogenous Bora levels were examined by Western blot analysis.

Phosphorylation of Bora at T501 is Required for β-TRCP Binding and Bora Degradation

Because phospho-Thr-501 is a β-TRCP binding site (16), we hypothesized that ATR mediated phosphorylation at Thr-501 resulted in β-TRCP binding and Bora degradation. Consistent with our hypothesis, mutating Thr-501 to Ala prevented DNA damage-induced ubiquitination and down-regulation of Bora (Fig. 2, E and F). The Bora T501A mutant was also more stable than WT Bora after DNA damage (Fig. 2G). These results suggest that Thr-501 is critical for Bora degradation following DNA damage. To confirm that phospho-Thr-501 is recognized by β-TRCP following DNA damage, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Fig. 2H, DNA damage induced the interaction between WT Bora and β-TRCP. However, the binding between the T501A mutant and β-TRCP could not be detected. To further confirm that β-TRCP is required for DNA damage-induced degradation of Bora, we used shRNA to knock down β-TRCP. As shown in Fig. 2I, the degradation of Bora was abolished in cells depleted of β-TRCP. These results suggest that DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of Bora at Thr-501 is required for β-TRCP binding and subsequent Bora degradation.

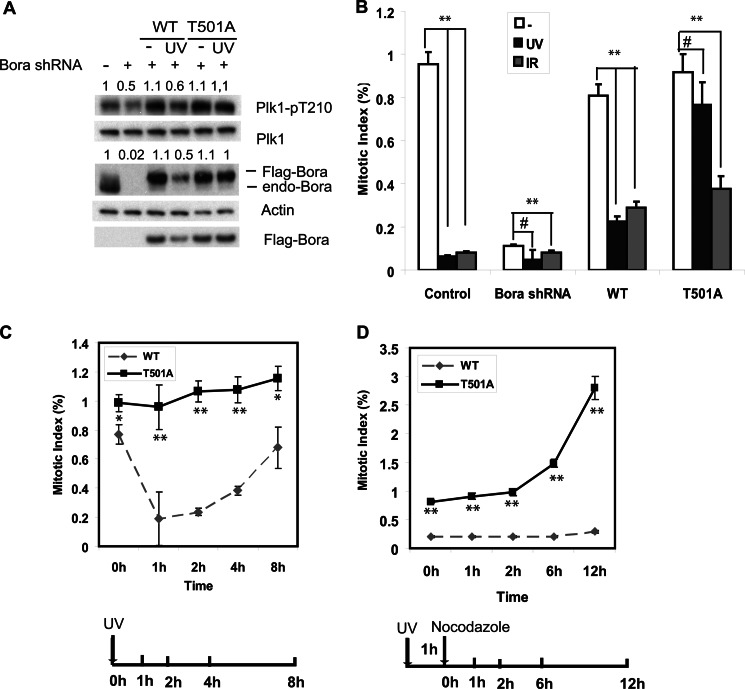

Phosphorylation of Bora at Thr-501 Is Important for G2/M Checkpoint Activation

Because Bora is important for Plk1 activation during mitotic entry (10, 11), we hypothesized that Plk1 inhibition after DNA damage is caused by decreased Bora levels. To test this hypothesis, we transfected cells with shRNA-resistant WT and T501A Bora, and depleted endogenous Bora with shRNA. Cells were then UV-irradiated. Consistent with previous reports (12–14), the phosphorylation of Plk1 Thr-210 was decreased following DNA damage, and this correlated with the lower wild-type Bora protein level. We did not observe a significant decrease of Plk1 levels. This is different from a previous report (19) reporting Plk1 degradation induced by DNA damage. However, our results are consistent with several other reports (12–14) (Fig. 3). These results suggest that phosphorylation and degradation of Bora is important for Plk1 inhibition following DNA damage.

FIGURE 3.

Degradation of Bora is required for G2/M checkpoint activation. U2OS cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding Bora shRNA. 48 h later, cells were transfected with shRNA-resistant WT or T501A Bora. Cells were left untreated or UV-irradiated (20 J/m2) or IR (10 gray). A, cells were lysed 1 h post-radiation and blotted with the indicated antibodies. B, cells were fixed at 1 h, and the mitotic index was determined by phospho-H3 staining. C, cells were UV-irradiated (20 J/m2) and fixed at the indicated time, and the mitotic index was determined by phospho-H3 staining. D, cells were UV-irradiated (20 J/m2).1 h later, cells were incubated in medium containing nocodazole and stained with phospho-H3 antibody at the indicated time to determine the mitotic index. 1000 cells were counted. The results represent the mean values from three independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E. #, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Plk1 activation is an important trigger for the mitotic entry, and impaired Plk1 activity decreases the population of mitotic cells, which contributes to the G2/M arrest. To explore the effect of Bora on G2/M checkpoint activation after DNA damage, we examined the G2/M checkpoint activation in cells overexpressing WT or T501A Bora. We found that DNA damage resulted in a significant decrease of the mitotic population in cells expressing WT Bora within 1 h of UV irradiation, suggesting that the G2/M checkpoint is intact in these cells. Conversely, there was no significant change in mitotic population in cells expressing T501A Bora. On the other hand, the mitotic population in both WT and T501A Bora-expressing cells decreased with IR treatment. This is consistent with the observation that Bora levels were not regulated by IR (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that Thr-501 phosphorylation of Bora is important for UV-induced but not IR-induced G2/M checkpoint activation (Fig. 3, B and C).

Bora degradation has been shown to be important to mitotic exit (15, 16). To exclude the possibility that the accumulation of mitotic cells in cells expressing mutant Bora is due to mitotic exit defect, we treated cells with UV radiation and then incubated cells in the presence of nocodazole. Consistent with Fig. 3, B and C, in cells expressing WT Bora, fewer cells entered mitosis after UV treatment. However, mitotic entry was less affected in cells expressing T501A Bora (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that UV-induced degradation of Bora is required for Plk1 inhibition and G2 arrest.

Cell cycle progression is under tight regulation to maintain the genomic integrity. The G2/M checkpoint stops cells from undergoing mitosis upon DNA damage until damaged DNA is repaired. One of the major targets of the G2/M checkpoint is Plk1, which is inactivated following DNA damage. However, how the DNA damage response pathway regulates Plk1 activity is not clear. Here we show that Bora is a direct target of ATR and that the phosphorylation of Bora by ATR results in Bora degradation, which is required for Plk1 inhibition and the activation of the G2/M checkpoint. We propose a working model in Fig. 4. During the normal cell cycle, Bora is up-regulated in G2 phase and binds to the Plk1 Polo-box domain and kinase domain. This changes the conformation of Plk1, making the Plk1 kinase domain accessible to Aurora A-mediated phosphorylation and activation. Activated Plk1 then phosphorylates its downstream targets and promotes mitotic entry (16). When cells encounter UV irradiation, ATR kinase is activated and phosphorylates Bora at Thr-501. This phosphorylation at the degron is recognized by β-TRCP, resulting in the degradation of Bora through the proteasome degradation system. Plk1 is thus kept inactivated, and mitotic entry is delayed. In summary, our studies reveal a key molecular mechanism by which the DNA damage signaling pathway regulates Plk1.

FIGURE 4.

A working model of DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint activation through the Bora-Plk1 pathway. Under normal, unstressed conditions, Bora accumulates in G2 phase, binds to Plk1, and facilitates Plk1 activation by Aurora A. Plk1 then activates its downstream targets, and cells enter mitosis. However, when genotoxic stressors are present during G2 phase, ATR is activated and phosphorylates Bora at Thr-501, which is recognized by SCF-β-TRCP and results in Bora degradation. Thus, Plk1 is kept inactivated, and cells are arrested at G2 phase. Ub, ubiquitination.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA130996, CA129344, and CA148940 (to Z. L.). This work was also supported by the Richard Schulze Family Foundation, by National Basic Research Program of China 973 Program Grant 2013CB530700), and by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81222029 and 31270806 (to J. Y.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- ATR

- ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related

- IR

- ionizing radiation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Takaki T., Trenz K., Costanzo V., Petronczki M. (2008) Polo-like kinase 1 reaches beyond mitosis-cytokinesis, DNA damage response, and development. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 650–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barr F. A., Silljé H. H., Nigg E. A. (2004) Polo-like kinases and the orchestration of cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watanabe N., Arai H., Nishihara Y., Taniguchi M., Watanabe N., Hunter T., Osada H. (2004) M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFβ-TrCP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4419–4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qian Y. W., Erikson E., Li C., Maller J. L. (1998) Activated polo-like kinase Plx1 is required at multiple points during mitosis in Xenopus laevis. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 4262–4271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoo H. Y., Kumagai A., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Dunphy W. G. (2004) Adaptation of a DNA replication checkpoint response depends upon inactivation of Claspin by the Polo-like kinase. Cell 117, 575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., Shinya N., Iwamatsu A., Nishida E. (2001) Polo-like kinase 1 phosphorylates cyclin B1 and targets it to the nucleus during prophase. Nature 410, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jang Y. J., Ma S., Terada Y., Erikson R. L. (2002) Phosphorylation of threonine 210 and the role of serine 137 in the regulation of mammalian polo-like kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44115–44120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee K. S., Erikson R. L. (1997) Plk is a functional homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc5, and elevated Plk activity induces multiple septation structures. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 3408–3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kelm O., Wind M., Lehmann W. D., Nigg E. A. (2002) Cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation of the Xenopus polo-like kinase Plx1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25247–25256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seki A., Coppinger J. A., Jang C. Y., Yates J. R., Fang G. (2008) Bora and the kinase Aurora A cooperatively activate the kinase Plk1 and control mitotic entry. Science 320, 1655–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Macůrek L., Lindqvist A., Lim D., Lampson M. A., Klompmaker R., Freire R., Clouin C., Taylor S. S., Yaffe M. B., Medema R. H. (2008) Polo-like kinase-1 is activated by Aurora A to promote checkpoint recovery. Nature 455, 119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smits V. A., Klompmaker R., Arnaud L., Rijksen G., Nigg E. A., Medema R. H. (2000) Polo-like kinase-1 is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 672–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Vugt M. A., Smits V. A., Klompmaker R., Medema R. H. (2001) Inhibition of Polo-like kinase-1 by DNA damage occurs in an ATM- or ATR-dependent fashion. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41656–41660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsvetkov L., Stern D. F. (2005) Phosphorylation of Plk1 at S137 and T210 is inhibited in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle 4, 166–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chan E. H., Santamaria A., Silljé H. H., Nigg E. A. (2008) Plk1 regulates mitotic Aurora A function through βTrCP-dependent degradation of hBora. Chromosoma 117, 457–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seki A., Coppinger J. A., Du H., Jang C. Y., Yates J. R., 3rd, Fang G. (2008) Plk1- and β-TrCP-dependent degradation of Bora controls mitotic progression. J. Cell Biol. 181, 65–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gumireddy K., Reddy M. V., Cosenza S. C., Boominathan R., Boomi Nathan R., Baker S. J., Papathi N., Jiang J., Holland J., Reddy E. P. (2005) ON01910, a non-ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor of Plk1, is a potent anticancer agent. Cancer Cell 7, 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sarkaria J. N., Busby E. C., Tibbetts R. S., Roos P., Taya Y., Karnitz L. M., Abraham R. T. (1999) Inhibition of ATM and ATR kinase activities by the radiosensitizing agent, caffeine. Cancer Res. 59, 4375–4382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bassermann F., Frescas D., Guardavaccaro D., Busino L., Peschiaroli A., Pagano M. (2008) The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell 134, 256–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.