Abstract

We report a novel synthetic strategy of polymer-drug conjugates for nanoparticulate drug delivery: hydroxyl-containing drug (e.g., camptothecin, paclitaxel, doxorubicin and docetaxel) can initiate controlled polymerization of phenyl O-carboxyanhydride (Phe-OCA) to afford drug-poly(Phe-OCA) conjugated nanoparticles, termed drug-PheLA nanoconjugates (NCs). Our new NCs have well-controlled physicochemical properties, including high drug loadings, quantitative drug loading efficiencies, controlled particle size with narrow particle size distribution, and sustained drug release profile over days without “burst” release effect as observed in conventional polymer/drug encapsulates. Compared with polylactide NCs, the PheLA NCs have increased non-covalent hydrophobic inter-chain interactions and thereby result in remarkable stability in human serum with negligible particle aggregation. Such distinctive property can reduce the premature disassembly of NCs upon dilution in blood stream, prolong NCs' in vivo circulation with the enhancement of intratumoral accumulation of NCs, which have a bearing in therapeutic effectiveness.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, nanoconjugates, drug delivery, polymeric nanoconjugates, camptothecin, breast cancer, nanomedicine, circulation

1. Introduction

The past several decades have witnessed the explosive development of polymeric nanomedicines for cancer diagnosis and treatment,1-4 among which polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) have attracted much interest.5-8 Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is one of the most widely used polymeric materials because of its excellent safety profile, tunable degradation kinetics and ease of synthesis.9-11 PLA/drug NPs can be readily prepared via co-precipitation of PLA and drugs.12, 13 However, this method may result in PLA NPs with formulation issues that are difficult to address, such as “burst” drug release, low drug loading and loading efficiency, and heterogeneous compositions.14 These formulation challenges present bottlenecks for the clinical translation and applications of PLA NPs.15, 16

To address these challenges, we developed drug-PLA nanoconjugates (NCs) through drug-initiated ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of lactide (LA) followed by nanoprecipitation of the resulting drug-PLA conjugates.17, 18 Drug-PLA NCs have nearly 100% loading efficiency, well controlled release kinetics with negligible “burst” drug release effects, and narrowly distributed particle sizes.19 Because drug-PLA NCs are prepared via the precipitation of the drug terminally conjugated PLA, the drug loading of NC is essentially the same as the drug content in the linear drug-PLA conjugate. To achieve high drug loading, it is essential to prepare drug-PLA conjugate with very short, low molecular weight (MW) PLA chain. However, nanoprecipitation of drug-PLA with lowered MW results in enlarged size and reduced stability of NCs because of decreased inter-chain interactions of the drug-PLA conjugates. In attempts to prepare in vivo applicable NCs with stably surface-coated poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) via the co-precipitation of drug-PLA conjugate and mPEG-PLA, low hydrophobic interaction between the low-MW drug-PLA and mPEG-PLA leads to NCs with reduced stability of PEG shell, increased tendency of particle disassembly upon dilution post-injection and increased possibility of particle aggregation because of depletion of PEG shell.

To prepare structurally stable NCs with low MW (thus high drug-loading) drug-polymer conjugates, one possible solution is to increase the hydrophobicity of the polymer.20 However, the side-chain methyl groups of PLA cannot be further modified, which makes it difficult to modulate PLA hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity.21, 22 Thus, it would be interesting to develop new monomers to synthesize PLA-like materials with enhanced hydrophobic interactions to be potentially used for making drug-polymer NCs with high drug loadings. Natural amino acids serve as a rich renewable resource for the preparation of biomaterials.23-25 Given the structural similarity between amino acids and α-hydroxyl acids, the attempt to synthesize 1,3-dioxolane-2,5-dione or O-carboxyanhydride (OCA) from phenylalanine (Phe-OCA, Figure 1a) and polymerize it to make PLA-like materials bearing hydrophobic phenyl side chains has attracted our interest.

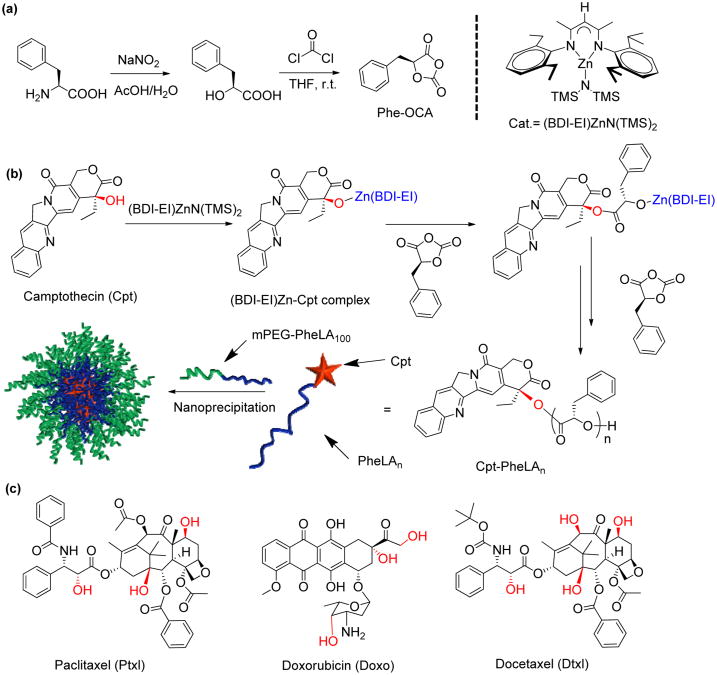

Figure 1.

(a) Synthetic scheme of Phe-OCA monomer and the structure of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 catalyst. (b) Schematic illustration of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2/Cpt mediated ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of Phe-OCA followed by formulation of Cpt-PheLAn nanoconjugates (NCs, n = the feed ratio of Phe-OCA/Cpt) using nanoprecipitation. (c) Chemical structures of hydroxyl-containing paclitaxel, doxorubicin and docetaxel.

Herein, we report a scalable and concise synthetic strategy to prepare polymeric NPs with enhanced hydrophobicity derived from phenylalanine. Camptothecin (Cpt) was used as a hydroxyl-containing drug to initiate the polymerization of Phe-OCA to prepare Cpt-poly(Phe-OCA) conjugates, termed Cpt-PheLAn, where n is the degree of polymerization. Followed by nanoprecipitation, Cpt-PheLAn self-assembled in water and formed nanoconjugates (NCs) with well controlled physicochemical properties. The high drug loading, narrowed-distributed particle size, sustained drug release profiles and controlled cytotoxicity of Cpt-PheLAn NCs were well characterized. Increased hydrophobicity of the PheLAn chain enhanced non-covalent chain-chain interactions of the Cpt-PheLAn conjugates and substantially improved Cpt-PheLAn NC stability in electrolyte solution even upon dilution. The use of such high drug-loading NCs could potentially improve NC's pharmacological properties including prolonged in vivo circulation and improved tumor accumulation, as indicated by our preliminary 64Cu-labeled biodistribution study.

2. Materials and Methods

2. 1. General

β-Diimine (BDI) ligands and the corresponding metal complex (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 were prepared by following the published procedure26 and stored at −30 °C in a glovebox. Anhydrous solvents were purified by alumina columns and kept anhydrous by using molecular sieves. Paclitaxel (Ptxl), docetaxel (Dtxl) and 20(S)-camptothecin (Cpt) were purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA) and stored at −30°C in a glovebox prior to use. Doxo·HCl was purchased from Bosche Scientific (New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and used as received. Removal of HCl of Doxo·HCl was achieved by following the procedure reported in the literature.27 All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) and used as received unless otherwise noted. The molecular weights (MWs) of PheLAn were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC, also known as size exclusion chromatography (SEC)) equipped with an isocratic pump (Model 1100, Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA), a DAWN HELEOS 18-angle laser light scattering detector and an Optilab rEX refractive index detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The wavelength of the HELEOS detector was set at 658 nm. The size exclusion columns (Phenogel columns 100, 500, 103 and 104 Å, 5 μm, 300 × 7.8 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) used for the analysis of polymers or polymer-drug conjugates were serially connected on the GPC. The GPC columns were eluted with THF (HPLC grade) at 40 °C at 1 mL/min. HPLC analyses were performed on a System Gold system equipped with a 126P solvent module and a System Gold 128 UV detector (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) equipped with a 126P solvent module, a System Gold 128 UV detector and an analytical C18 column (Luna C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μ, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The NMR studies were conducted on a Varian UI500NB system (500 MHz). The critical micelle concentration (CMC) was determined by a fluorescence spectrometer (Perkin Elmer LS55 fluorescence spectrometer, Wellesley, USA) with Nile Red as the fluorescence probe. The sizes and the size distributions of the PheLAn NCs were determined on a ZetaPALS dynamic light scattering (DLS) detector (15 mW laser, incident beam = 676 nm, Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY, USA). Lyophilization of the NCs was carried out on a benchtop lyophilizer (FreeZone 2.5, Fisher Scientific, USA). The MCF-7 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) used in the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1000 units/mL aqueous penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Female athymic nude mice (6-8 weeks) were purchased from National Cancer Institute (NCI, Frederick, MD, USA). Ad libitum feeding was provided. Light was provided in a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

2.2. Preparation and characterization of drug-PheLAn conjugates

In a glovebox, Cpt (3.5 mg, 0.01 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF, 300 μL) and mixed with a THF solution (500 μL) containing (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 (6.5 mg, 0.01 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 15 min. Phe-OCA (192.4 mg, 100 equiv) was dissolved in THF (2 mL) and added to the stirred (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 and Cpt solution. The reaction proceeded in the glovebox overnight. The conversion of Phe-OCA was determined by FT-IR by monitoring the disappearance of Phe-OCA anhydride band at 1812 cm−1 (Figure S3). After Phe-OCA was completely consumed, the reaction was stopped by quenching the polymerization solution with cold methanol solution (300 μL). The polymer was precipitated with ether (50 mL), collected by centrifugation and dried by vacuum. The molecular weight and molecular weight distribution (MWD = Mw/Mn) of Cpt-PheLAn were accessed by GPC (Table 1). Ptxl-PheLAn (Doxo-PheLAn or Dtxl-PheLAn) conjugate were prepared by following the similar procedure as described above by using the corresponding drug as the initiator for the polymerization of Phe-OCA in the presence of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2.

Table 1.

Polymerization of Phe-OCA mediated by (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2/Cpt.

| Entrya | R-OH | [M]/[Cat.] | Temp. | Time(h) | Conv (%) b | Mn cal (×103g/mol) | Mn (×103g/mol) c | MWD (Mw/Mn) c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cpt | 25/1 | rt | 12 | >98 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 1.19 |

| 2 | Cpt | 50/1 | rt | 12 | >98 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 1.15 |

| 3 | Cpt | 100/1 | rt | 12 | >98 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 1.17 |

| 4 | mPEG5k | 100/1 | rt | 12 | >98 | 19.9 | 26.0 | 1.19 |

All reactions were performed in glovebox. Abbreviation: Temp.= temperature, Conv.% = conversion of monomer %, MWD = Molecular weight distribution.

Determined by FT-IR by monitoring the disappearance of Phe-OCA anhydride peak at 1820-1800 cm−1.

Determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). dn/dc= 0.63 based on the 100% mass recovery dn/dc program determination by GPC (ASTRA 5).

2.3. Synthesis of mPEG5k-PheLAn diblock polymer

A diblock polymer of mPEG5k-PheLAn was synthesized by following similar procedures as described in the Section 2.2 by using mPEG5k-OH as the initiator. The conversion of Phe-OCA was determined by FT-IR by monitoring the disappearance of the Phe-OCA anhydride band at 1812 cm−1. After Phe-OCA was completely consumed, the reaction was stopped by quenching the polymerization reaction with cold methanol solution (300 μL). The polymer was precipitated with ether (50 mL) collected by centrifugation and dried by vacuum. The molecular weight and MWD of the obtained mPEG5k-PheLAn were accessed by GPC (Mn= 26.0 kDa, MWD = 1.19, Table 1).

2.4. Synthesis of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)-PheLA25 conjugates

The NH2-PheLA25 conjugate was synthesized by following a similar procedure as described in the Section 2.3 by using ethanolamine as the initiator. In a reaction vial containing NH2-PheLA25 conjugates (23.5 mg, 0.004 mmol) was added an anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) solution (0.5 mL) of DOTA-NCS (2.2 mg, 0.018 mmol) and triethylamine (3.6 mg, 0.036 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h under nitrogen at rt. The solvent and triethylamine were removed under vacuum to give DOTA-PheLA25, which was used directly without further purification.

2.5. General procedure for the preparation and characterization of drug-PheLAn nanoconjugates (NCs)

Ptxl- PheLAn, (Doxo-PheLAn or Dtxl-PheLAn) conjugate were prepared by following the similar procedure as described in the Section 2.2 by using the corresponding drug as the initiator for the polymerization of Phe-OCA in the presence of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2. A DMF solution of the drug-PheLAn conjugate (100 μL, 10 mg/mL) was added dropwise to nanopure water (2 mL). The resulting drug-PheLAn NCs were washed by ultrafiltration (5 min, 3000 × g, Ultracel membrane with 10,000 NMWL, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), collected from the residue and then characterized by DLS for particle sizes and size distributions, and by HPLC for drug loadings by following the reported procedures.17, 19

2.6. Extraction of Cpt from NCs

Cpt-PheLA25 NCs (1 mg) in water (1 mL) was treated with the NaOH solution (1 M, 1 mL) for 12 h at rt. The pH value of Cpt-PheLA25 suspension was then tuned to 2 by phosphoric acid. The solution color turned yellow. The resulting solution was concentrated, and the released Cpt was collected and purified through semi-prep HPLC column (Jupitor, 250 × 21.20 mm, 10 μ, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase of HPLC was acetonitrile:water:TFA (25:75:0.75, v/v/v). The collected yellow oily compound after removal of the solvents was dissolved in trace of phosphoric acid:methanol (1:1, v/v) solution (500 μL). The pH of the solution was tuned to 3-4 by NaOH (0.1 M). The resulting solution was extracted with chloroform (5 × 10 mL). The organic phase was then dried by magnesium sulfate. After the organic solvent was evaporated, a slight yellow solid was obtained. The solid was analyzed by HPLC and its spectrum was compared with the authentic Cpt, showing that the released compound has identical elution time as to the authentic Cpt.

2.7. Release kinetic study of Cpt-PheLAn NCs

Cpt-PheLA25 NCs were prepared by nanoprecipitation as previously described. Cpt-PheLA25 (10 mg, 0.002 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (1 mL) to prepare a stock solution of 10 mg/mL. The DMF solution of Cpt-PheLA25 (200 μL) was dropwise added to a vigorously stirred water solution (4 mL). The NCs were collected and purified by ultrafiltration (5 min, 3000 × g, Ultracel membrane with 10,000 NMWL, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The collected NCs were dispersed in human serum buffer (human serum:PBS=1:1, v/v, 5 mL), divided into 10 equal-volume portions, and added to 10 eppendorf microcentrifuge tubes (500 μL NC solution in each tube). The tubes were incubated at 37°C. Complete release of Cpt from NC was predetermined by the hydrolysis mentioned above in the Section 2.6. At scheduled time points, two tubes were taken out, to which methanol (500 μL) was added to precipitate proteins. The precipitates were removed by centrifugation (5 min, 15000 × g). The supernatant then was injected into HPLC for analysis of the released Cpt. For the HPLC analysis, acetonitrile:water (containing 1% TFA) was used as mobile phase. The gradient for acetonitrile:water (containing 1% TFA) was changed linearly from 25:75 to 75:25 over 30 min and then kept at 75:25 for 30 min and changed back to 25:75 over 5 min. the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. Analytical C18 column (Luna C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μ, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) was used to perform the analysis. The integrated area of the Cpt peak was documented and compared with that of 100% released Cpt to determine the released Cpt.

2.8. Formation and characterization of Cpt-PheLA100 NCs in human serum (50%)

A Cpt-PheLA100 DMF solution (100 μL, 10 mg/mL) was dropwise added into nanopure water (2 mL) (DMF:water = 1:20, v/v). The obtained NCs were dispersed in human serum buffer (human serum:PBS = 1:1, v/v). The particle sizes were measured by DLS and followed over 60 min.

2.9. Lyophilization of Cpt-PheLA100 NCs with human serum albumin (HSA)

A Cpt-PheLA100 DMF solution (100 μL, 10 mg/mL) was dropwise added to vigorously stirred nanopure water (2 mL). The resulting NCs were analyzed by DLS. Human serum albumin (HSA) was then added into the NC solution. The mixture was lyophilized for 16 h at −50 °C to obtain a white powder. The white powder was reconstituted in nanopure water (2 mL) and the solution was stirred for 5 min at rt. The resulting NC solution was analyzed by DLS to assess NC size and size distribution.

2.10. Determination of the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of mPEG5k-PheLA100 and mPEG5k-PLA100

CMC of mPEG5k-PheLA100 and mPEG5k-PLA100 were determined using Nile Red (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) as an extrinsic probe. Serial solutions with fixed Nile Red concentration of 6 × 10−7 M and various concentrations of mPEG5k-PheLA100 and mPEG5k-PLA100 between 3.9 × 10−5 and 0.5 mg/mL were prepared. Fluorescence spectra were obtained at rt. Fluorescence measurements were taken at an excitation wavelength of 557 nm and the emission monitored from 580 to750 nm. Excitation and emission slit widths were both maintained at 10.0 nm and spectra were accumulated with a scan speed of 500 nm/min.

2.11. Determination of the cytotoxicity of Cpt-PheLAn NCs

MCF-7 cells were placed in a 96-well plate for 24 h (10,000 cells per well). Cells were washed with prewarmed PBS (100 μL). Freshly prepared Cpt-PheLA25, Cpt-PheLA50, and Cpt-PheLA100 NCs (prepared in 1 × PBS, 100 μL) were added to the cells. Cpt was used as a positive control. Untreated cells and PheLA NPs without Cpt were used as negative controls in this MTT assay. The Cpt-PheLAn NCs (n = 25, 50 and 100) were applied to MCF-7 cells at a concentration up to 0.5 μg/mL. The cells were incubated for 72 h in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The standard MTT assay protocols were followed thereafter.

2.12. 64Cu labeled PheLA25 NCs

The 64Cu chloride (300 μCi, obtained from Washington University at St. Louis, MO, USA) was mixed with PEGylated DOTA-PheLA25 NCs (20 mg) in NH4OAc buffer (pH = 5.5, 0.1 M, 0.5 mL). The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 60 °C. To determine the labeling efficiency, the NCs were washed by ultrafiltration (10 min, 3000 × g, Ultracel membrane with 10 000 NMWL, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and the radioactivity in the supernatant and the NC solution was measured at different time points respectively (Figure S6a). The purified 64Cu-labelled PheLA25 NCs were used for injection.

2.13. In vivo biodistribution study of 64Cu-labelled PheLA25 NCs

Six female athymic nude mice bearing MCF-7 human breast cancer xenografts (6-8 weeks) were divided into two groups (n = 3), minimizing the weight differences. The two groups of mice were treated with 64Cu-labelled mPEG5k-PLA100 NCs and 64Cu-labelled mPEG5k-PheLA100 NPs at a dose of 35 μCi intravenously, respectively. Mice were euthanized 24 h post injection. The major organs (liver, spleen, kidney, heart, and lung), as well as MCF-7 subcutaneous tumors were collected, weighed and measured for radioactivity (64Cu) with a γ-counter (Wizard2, Perkin-Elmer, USA) using appropriate energy window centered at photo peak of 511 keV. Raw counts were corrected for background, decay, and weight. Corrected counts were converted to microcurie per gram of tissue (μCi/g) with a previously determined calibration curve by counting the 64Cu standards (Figure S6b). The activity in each collected tissue sample was calculated as percentage of the injected dose per gram of tissue (% I.D./g). For this calculation, the tissue radioactivity was corrected for the 64Cu decay (T(1/2)=12.7 h) to the time of γ -well counting.

2.14. Pharmacokinetic Study of 64Cu labeled PheLA25 NCs

Six female athymic nude mice (6-8 weeks) were divided into two groups (n = 3), minimizing the weight differences. The two groups of mice were treated with 64Cu-labelled mPEG5k-PLA100 NCs and 64Cu-labelled mPEG5k-PheLA100 NCs intravenously at a dose of 35 μCi, respectively. Blood was collected intraorbitally from mice at scheduled time points (0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 5 h, 10 h and 22 h) for pharmacokinetic profiling. The collected blood samples were weighed and measured for radioactivity (64Cu) with a γ-counter (Wizard2, Perkin-Elmer, USA) using appropriate energy window centered at photo peak of 511 keV. Raw counts were corrected for background, decay, and weight. Corrected counts were converted to microcurie per gram of tissue (μCi/g) with a previously determined calibration curve by counting the 64Cu standards (Figure S6b). The activity in each collected blood sample was calculated as percentage of injected dose per gram of blood (% I.D./g). For this calculation, the blood radioactivity was corrected for the 64Cu decay to the time of γ-well counting.

2.15. In vivo biocompatibility study of mPEG5k-PheLA100 NCs

Six female athymic nude mice (6-8 weeks) were divided into two groups (n = 3), minimizing the weight differences. In 3 mice, mPEG5k-PheLA100 NCs were administered intravenously (200 μL, 25 mg/mL) via lateral tail vein at a dose of 250 mg NC/kg. The other 3 mice received intravenous PBS, and served as a sham control group. The animals were euthanized 24 h later by carbon dioxide. Organs including heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, and intestine were collected following by flash freezing in optimum cutting temperature (O.C.T.) compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA, USA). Tissues were sectioned using cryostat at the thickness of 10 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination. Characterization of all the collected tissues for inflammatory cell infiltrate including macrophages and neutrophils were performed by Nanozoomer Digital Pathology System (Hamamatsu) at 20 × magnification and analysed by an independent pathologist.

Statistical Analyses

Student's t-test comparisons at 95% confidence interval were used for statistical analysis. The results were deemed significant at 0.01 < *p ≤ 0.05, highly significant at 0.001 < **p ≤ 0.01, and extremely significant at ***p ≤ 0.001.

3. Results and Discussion

The OCA can be synthesized from L-phenylalanine in a large scale with high purity (Figure S1). The diazontization of L-phenylalanine with sodium nitrite provided pure 2-hydroxyl-3-phenylpropanoic acid with satisfactory yield (>75%). Condensation of the resulting α-hydroxyl acid with phosgene by following the reported procedures24, 25, 28 produced the corresponding 1,3-dioxolane-2,4-diones, or phenyl O-carboxyanhydrides (Phe-OCA). Phe-OCA was obtained in high yield (>50%) as white crystalline solid after recrystallization in a glovebox. (Figure 1)

Bourissou group previously reported the ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of Ala-OCA, an OCA derived from alanine, by using DMAP as the catalyst.29 However, no polymerization of Phe-OCA was observed when DMAP was used as the catalyst and Cpt was used as the initiator, presumably due to the low reactivity of the tertiary 20-OH of Cpt and increased steric encumbrance of the Phe-OCA compred to Ala-OCA. We attempted to use more reactive metal catalysts as what we previously used in drug-initiated lactide polymerization and functional group transformation.17-19, 30, 31

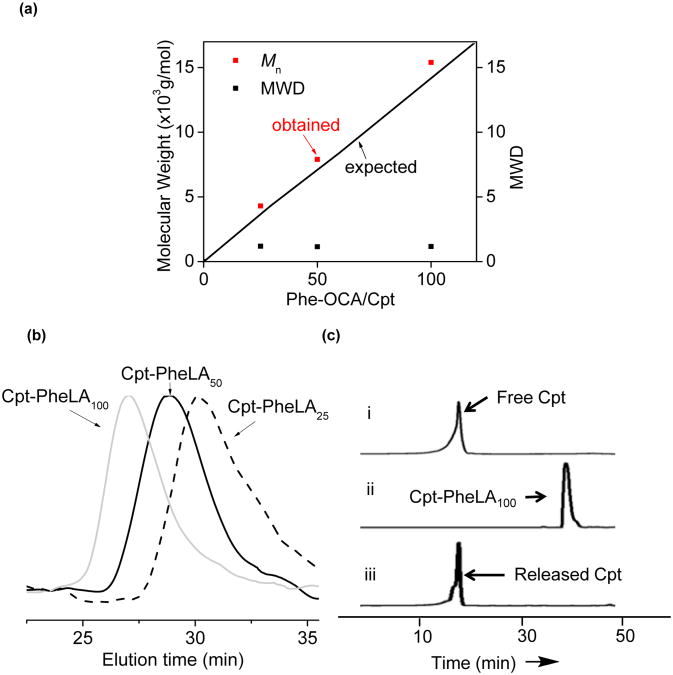

It is known that a metal alkoxide (MOR) can be prepared in situ by mixing a hydroxyl containing compound (R-OH) with a metal-amino complex and subsequently used to initiate ROP of cyclic esters.32 We first tested the feasibility of forming Cpt-metal complex. (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 (Figure 1a), an active catalyst developed by Coates and coworkers for the polymerization of LA,32 was dissolved in THF to give a colorless solution. When this solution was added to a vial containing Cpt powder (1 equiv relative to (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2), and the mixture was stirred for 20 min, Cpt was completely dissolved and the color of the solution gradually turned to orange. In the absence of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2, however, Cpt remained insoluble in THF and there was no color change of the solution. The sharp contrast of the solubility of Cpt in the presence and absence of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 and the color change after Cpt was mixed with (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 suggested that there was a reaction between Cpt and (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 and (BDI-EI)Zn-Cpt alkoxide was possibly formed (Figure 1b).33 When 25-equiv Phe-OCA was added to the mixture of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2/Cpt, Phe-OCA polymerization was observed to proceed rapidly and completed in 12 h with >98% OCA conversion. The Mn of the resulting Cpt-poly(Phe-OCA)25, or Cpt-PheLA25, was 4.3 × 103 g/mol, which was in excellent agreement with the expected MW (3.9 × 103 g/mol) (entry 1, Table 1). Controlled polymerizations were also observed for polymerization at Phe-OCA/Cpt ratios of 50 and 100 (entry 2 and 3, Table 1). The MWs followed a linear correlation with the Phe-OCA/Cpt ratios (Figure 2a). All three drug-polymer conjugates had narrow molecular weight distributions (MWDs) (Table 1), evidenced by their monomodal GPC curves (Figure 2b). In addition, in order to confirm the successful conjugation of Cpt to the polymer chain by the ROP strategy, we prepared Cpt-PheLA15 and analyzed its end group by MALDI-TOF MS (Figure S4). The result clearly showed that Cpt was convalently conjugated to the PheLAn, and the Cpt lactone ring remains intact after polymerization. To study whether this strategy could be also applied to other hydroxyl group-containing therapeutic reagents, we selected paclitaxel (Ptxl), doxorubicin (Doxo) and docetaxel (Dtxl), and evaluated their capability of initiating the ROP of Phe-OCA in the presence of (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2. When mixed with (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2, all these tested drugs could initiate controlled ROP of PheOCA with nearly 100% drug incorporation efficiency and 100% monomer conversion (Table S1).

Figure 2.

(a) (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2/Cpt mediated controlled ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of Phe-OCA at various Phe-OCA/Cpt ratios (MWD = molecular weight distribution). (b) Overlay of the GPC traces of Cpt-PheLAn (n = 25, 50 and 100). (c) HPLC analysis of Cpt-initiated polymerization and release of Cpt from Cpt-PheLA100 NCs. (i) authentic Cpt. (ii) the Phe-OCA polymerization solution (M/I = 100) mediated by (BDI-EI)ZnNTMS and Cpt. (iii) Cpt released from Cpt-PheLA100 NCs treated with 1 M NaOH for 12 h.

Drug loading, particle size, and release kinetics are critical properties of a nanoparticulate drug delivery system.34 Polymeric NPs are typically prepared via co-precipitation of polymer and drugs.35 However, the drug loadings of polymeric NPs prepared from conventional co-precipitation of polymer and drug can be very low. For instance, we used Cpt/mPEG-PheLA100 (5:95, wt/wt) to prepare Cpt-containing NPs and obtained Cpt/mPEG-PheLA100 NP with diameter of 134 nm and a fairly large polydispersity of 0.27 (entry 4, Table 2). The drug loading was only 1.4% with the loading efficiency as low as 28.1%. When Cpt and mPEG-PheLA100 were mixed at a ratio of 25:75 (wt/wt) in attempts to increase drug loading, the drug loading of the resulting Cpt/mPEG-PheLA100 NP remained unchanged (1.4%, entry 5, Table 2); the loading efficiency further decreased the 5.5%, substantiating that it is impossible to increase drug loading of an encapsulated polymeric NP by simply mixing more drug with polymer. Furthermore, unencapsulated Cpt tends to be self-aggregated and resulted in heterogeneous compositions,33 evidenced by the observation of larger particles around 250-300 nm in addition to the Cpt-encapsulated mPEG-PheLA100 NP at 100-125 nm (Figure S5). In contrast, NPs prepared from Cpt-PheLAn conjugates, termed nanoconjugates (NCs) in this study, successfully addressed all these issues. For the polymerization at PheLA-OCA/Cpt ratios of 25:1, 50:1 and 100:1, no free Cpt was detected in the polymer solution after the polymerization was complete (ii, Figure 2c), indicating 100% drug incorporation efficiency. No Cpt release was observed during nanoprecipitation of Cpt-PheLAn conjugates, the drug loading efficiency of Cpt-PheLAn NCs were essentially 100% (entries 1-3, Table 2). The drug loadings of NCs can be pre-determined by PheLA-OCA/Cpt ratios used for polymerization. At the PheLA-OCA/Cpt ratio of 25, Cpt-PheLA25 NC drug loading is 8.5%, 6 times higher than that of Cpt/PheLA NPs (entries 3 vs. 5, Table 2). NCs with sub-100 nm size and narrow size distributions were obtained (entry 1-3, Table 2; Figure 3a). The narrow size distributions of NCs were in sharp contrast to the multimodal particle distributions observed in the Cpt-encapsulated PheLA NPs (Figure S5), which could be attributed to the quantitative drug incorporation and well-defined structure of Cpt-PheLAn conjugates which excluded the possibility of self-aggregation of Cpt and consequently reduced heterogeneities (Figure 3a; Figure S5). Cpt was conjugated to the PheLA polymer through ester linkage and could be released from NCs subjected to the hydrolysis of ester bond in the physiological conditions. To better mimic the physiological conditions, we performed the release kinetic study of Cpt from Cpt-PheLAn NCs in the 50% human serum buffer. The released Cpt from Cpt-PheLAn NCs has an identical HPLC elution time with authentic Cpt, indicating it has identical molecular structure with authentic Cpt without any Cpt-carboxylic acid formed (iii, Figure 2c). The release kinetics of Cpt from Cpt-PheLAn NCs was correlated with the drug loading (polymer chain length) (Figure 3c). Hennink group has reported a backbiting mechanism to explain this polymer chain length dependent release. 36 In our system, the degradation mechanism may be different because: (1) we used high molecular weight polymer; the backbiting in high-molecular weight polymer would get more difficult (2) the monomer PheLA has more bulky phenyl group on the side chain than the methyl group of LA, and such steric hindrance would further retard the backbiting process that requires the formation of 6-member ring intermediate state. We suggested that the lower the drug loading (longer Cpt-PheLAn polymer chain), the slower the drug release, presumably because longer polymer chains resulted in stronger hydrophobic interactions which made it more difficult for the access of Cpt-PheLAn ester linkages to aqueous environment for Cpt release via hydrolysis. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that during the degradation, the small-molecular weight chain scission products may have such backbiting mechanism. The details of the release mechanism needed to be further explored. The in vitro toxicities of NCs are correlated to the amount of Cpt released; they show strong correlation with drug loadings (Figure 3d). The IC50 values of Cpt–PheLA25, Cpt–PheLA50 and Cpt–PheLA100 NCs with similar sizes (≈ 100 nm), which were determined by MTT (MTT=3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assays in MCF-7 cells, are 116, 711, and 3326 nM, respectively. The IC50 value of Cpt–PheLA25 NC is about 3 times higher than that of free Cpt (38 nM), while the IC50 value of the Cpt–PheLA100 NC is two orders of magnitude higher. As a result, the toxicity of the NCs can be tuned in a wide range simply by controlling NC drug loading. In all three NCs tested, no burst release was observed while Cpt molecules were completely released from Cpt-encapsulated mPEG-PheLA100 NP within 24 h (Figure 3c). For potential clinical application and minimizing drug release prior to use, it is desirable to formulate NCs in solid form.37 We previously reported that albumin could function as lyoprotectants to prevent PLA-based NCs from aggregation during lyophilization.16 We attempted to use human serum albumin (HSA) as lyoprotectants of Cpt-PheLAn NC solid formulation. Figure 3b demonstrated that HSA could effectively protect solid form of Cpt-PheLAn NCs from aggregation; the lyophilized Cpt-PheLA NC100 NCs redispersed in aqueous solution maintained narrow particle size distribution and nearly identical size as the parental NCs.

Table 2. Characterization of Cpt-PheLAn NCs prepared by Phe-OCA polymerization mediated a by (BDI-EI)ZnN(TMS)2 versus NPs obtained by conventional Cpt/polymer encapsulationa.

| Entrya | Name | Method | M/I ratio or Wt feeding% | Eff (%)b | Loading (%)c | Size (nm)d | PDIe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cpt-PheLA100 NC | Conj. | 100 | >95 | 2.3 | 94 | 0.09 |

| 2 | Cpt-PheLA50 NC | Conj. | 50 | >95 | 4.5 | 82 | 0.10 |

| 3 | Cpt-PheLA25 NC | Conj. | 25 | >95 | 8.5 | 93 | 0.12 |

| 4 | Cpt5/ mPEG-PheLA100 NP | Encap. | 5 | 28.1 | 1.4 | 134 | 0.27 |

| 5 | Cpt25/ mPEG-PheLA100 NP | Encap. | 25 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 176 | 0.38 |

Abbreviation: NC=Nanoconjugates; NP=Nanoparticles; Encap.=Encapsulation; Conj.=Polymerization and nanoprecipitation; M/I = monomer/initiator ratio; Wt feeding = weight feeding of Cpt/polymer; Eff = for nanoconjugates, which is incorporation efficiency, the percent of therapeutic agent utilized in the initiation of Phe-OCA polymerization and for NPs, which is encapsulation efficiency; PDI=polydispersity derived from particle size using dynamic light-scattering; Cpt=Camptothecin. NCs are named as Cpt-PheLAM/I, NPs are named as drugwt feeding%/ mPEG-PheLA100.

[b] and [c] based on the reversed-phase HPLC analysis of unincorporated drug.

[d] and [e] characterized using dynamic light-scattering.

Figure 3.

Formulation and characterization of Cpt-PheLAn NCs. (a) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis of Cpt-PheLA100 NCs in water (0.5 mg/mL) and TEM image of Cpt-PheLA100 NCs (negative stained). (b) DLS analysis of NC reconstitution. (i) Cpt-PheLA100 NCs mixed with human serum albumin (HSA) in water before lyophilization. (ii) The reconstituted Cpt-PheLA100 NCs after lyophilization in the presence of HSA (HSA:NC = 10:1, w/w). (c) Release kinetic profiles of Cpt-PheLAn NCs (n = 25, 50 and 100) versus Cpt/mPEG-PheLA100 encapsulated NPs in human serum buffer (human serum:PBS = 1:1, v/v). (d) Cytotoxicity of various Cpt-PheLAn NCs (n = 25, 50 and 100) and free Cpt in MCF-7 cells (72 h, 37 °C).

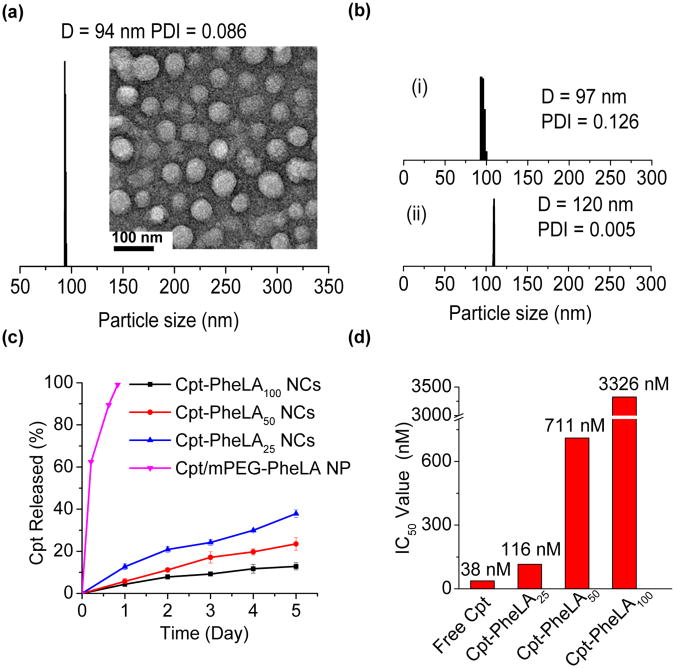

We next compared the difference of PheLA based NCs with PLA based NCs and first evaluated their stability in human serum. Surface modification of NPs with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is widely used for prolonged systemic circulation, reduced aggregation of NPs in blood,38 and suppressed nonspecific absorption of protein.39 To reduce the efforts of removing unreacted reagents and by-products, we attempted to use non-covalent approach to PEGylate NC surface instead of covalently conjugating PEG to NCs.35, 40 We used mPEG-PheLA100, an amphiphilic copolymer that has a PheLA block of 21 kDa and mPEG segment of 5 kDa,41 to PEGylate Cpt-PheLA25 NCs. It is expected that the PheLA block of mPEG-PheLA100 could form strong interaction with NCs through hydrophobic interaction to create a stable PEG shell as shown in Figure 1b. Similar approach has been used previously in NP surface PEGylation.42 Dropwise addition of the mixture of mPEG-PheLA100 and Cpt-PheLA25 to fast stirring nanopure water resulted in rapid PEG coating of Cpt-PheLA25 NCs. The resulting PEG coated NCs likely formed the core-shell nanostructure with hydrophobic Cpt-PheLA25 as the core and PEG as the shell, and the particle size remained unchanged in 50% human serum buffer for 5 days (Figure 4a) . In comparison, the size of PEGylated Cpt-LA25 NCs prepared by same strategy with mPEG-LA100 was found to increase from 122 nm to 175 nm under the same condition (Figure 4a), presumably due to the slow depletion of PEG shell from the mPEG-PLA/Cpt-LA25 NC surface. This study suggests that increased polymer chain-chain interaction can indeed improve the surface PEGylation stability and facilitates NCs' in vivo application. Because PheLAn has stronger hydrophobic interaction than LAn, and the corresponding PheLAn NCs should be more stable against dilution and has a relatively low critical micelle concentration (CMC). The CMC of mPEG-LA100 NC was determined to be 0.045 mg/mL. As expected, the CMC of mPEG-PheLA100 NC was 50% lower (0.022 mg/mL) (Figure 4b). Upon 100 time dilution the mPEG-LA100 NC size increased by 30% from 110 nm to 143 nm, while mPEG-PheLA100 NC size only increased by 10% from 108.8 nm to 119.9 nm (Figure 4c). Thus, under a dilute condition when mPEG-LA100 NC is completely dissembled, mPEG-PheLA100 NC might still keep its nanostructures as illustrated in Figure 4d.

Figure 4.

(a) Stability of PEGylated Cpt-PheLA25 NCs versus PEGylated Cpt-PLA25 NCs in human serum buffer (human serum:PBS = 1:1, v/v). (b) CMC determination of mPEG5k-PheLA100 and mPEG5k-LA100. Intensity of Nile Red versus concentrations of mPEG5k-PheLA100 and mPEG5k-PLA100. The CMC was determined by taking the midpoint in the plots, which was 2.2 × 10−2 mg/mL and 4.5 × 10−2 mg/mL, respectively. (c) The particle size changes of PEGylated PheLA100 NCs and PEGylated LA100 NCs with/without dilution as determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The original concentration of NC was 0.5 mg/mL. (d) Proposed changes of core-shell nanostructure of PEGylated PheLAn and PEGylated LAn NPs upon dilution after injection into the body: (i) PEGylated PheLAn NCs, stable micellar structure due to enhanced non-covalent interactions (hydrophobic interactions and π-π stacking) in the polymeric core preventing rapid dissolution of core-shell nanostructure in vivo. (ii) PEGylated LAn NCs, loosely packed polymeric core disrupted upon dilution. Orange star = drug cargos; blue line = PheLA/PLA polymer chain; green line = PEG.

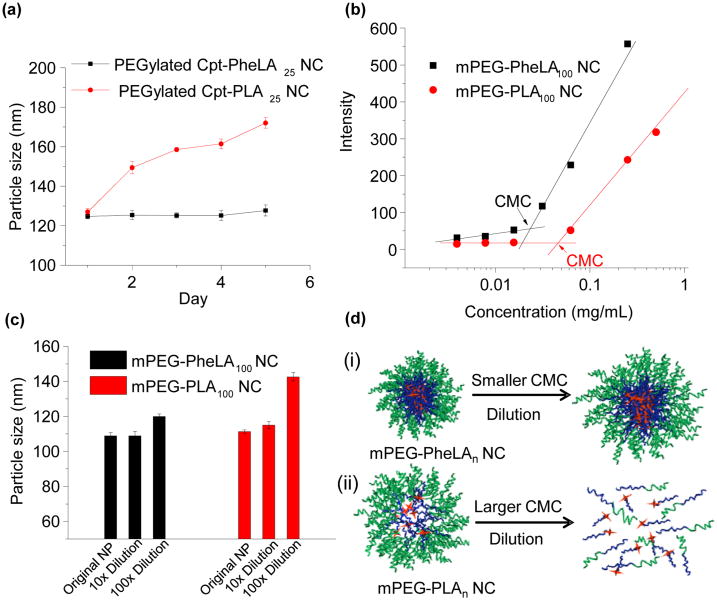

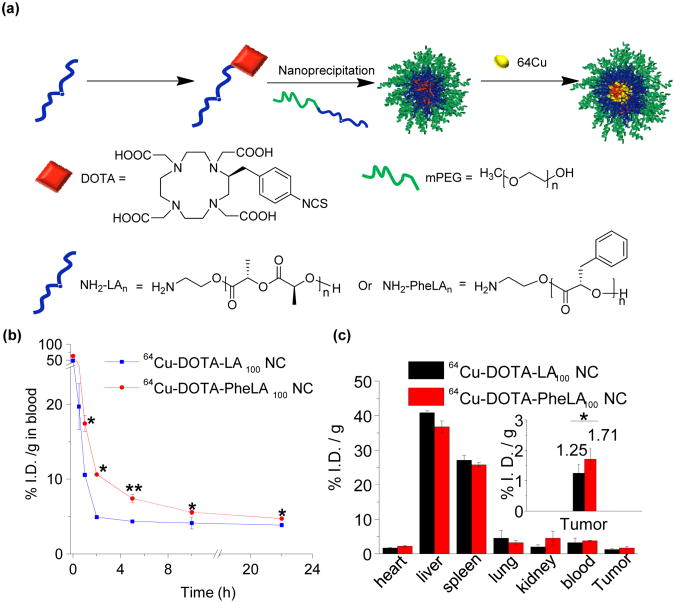

We then evaluated whether increased stability of PheLA NC PEGylation would lead to prolonged in vivo circulation and enhanced pharmacological performance by comparing the pharmacokinetics (PK) and in vivo biodistribution of PEGylated PheLA NCs and PLA NCs. For the PK study, 64Cu-labeled PEGylated PheLA100 NCs and 64Cu-labeled PEGylated LA100 NCs (Figure 5a) were injected into mice (n = 3) through tail vein intravenous (i.v.) injection, respectively. At predetermined time points, a small volume of blood was taken from orbital sinus and collected for quantitative measurements. Concentrations of PEGylated PheLA100 NCs in the blood within the first five hours post-injection were nearly twice as much as the PLA counterparts (p< 0.05 at t = 1 and 2 h and p < 0.01 at t = 5 h), showing that PEGylated PheLA NCs were cleared from blood much slower than PEGylated LA100 NCs (Figure 5b). For the in vivo biodistribution study, 64Cu-labeled PEGylated PheLA100 NCs and 64Cu-labeled PEGylated PLA NCs (50 mg/kg) were injected via lateral tail vein injection into MCF-7 human breast cancer bearing athymic nude mice (n = 3), respectively. Twenty four hours post injection, normal and tumor tissues were harvested and the 64Cu radioactivities in the liver, heart, spleen, kidney, lung, blood, and tumor tissues were assessed and normalized against the total injected dose and tissue mass (%I.D./g) (Figure 5c). The majority of NCs accumulated in the liver and the spleen; while lesser concentrations of NCs were localized in the respiratory and the urinary systems. PEGylated PheLA100 NCs showed improved tumor accumulation by 50% compared to PEGylated LA100 NCs (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic illustration of synthesis and formulation of 64Cu-labelled PEGylated PheLA NCs and PLA NCs. (b) Six athymic nude mice were divided into two groups (n = 3) and injected 64Cu-labelled PEGylated PheLA100 NCs and 64Cu-labeled PEGylated PLA100 NCs via i.v. injection, respectively. Mice were taken blood intraorbitally at different time points (0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 5 h, 10 h, and 22 h) and the radioactivity in blood was determined using γ-counter. Statistical significance analysis were assessed by Two-Sample Unpaired Student's t-test; 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01 are considered statistically significant and highly significant and are denoted as “*” and “**” respectively, in the figure. (c) Six athymic nude mice were divided into two groups (n = 3) and injected 64Cu labelled PEGylated PheLA100 NCs and PLA100 NCs via i.v. injection, respectively. Mice were euthanized after 24 h and the major organs were collected. The radioactivity in each organ was determined using γ-counter. The fidelity of utilizing γ-counter for quantitative radioactivity analysis in biological tissues was verified in a series of control studies. All the organ distribution were presented as percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (% I.D./g tissue).

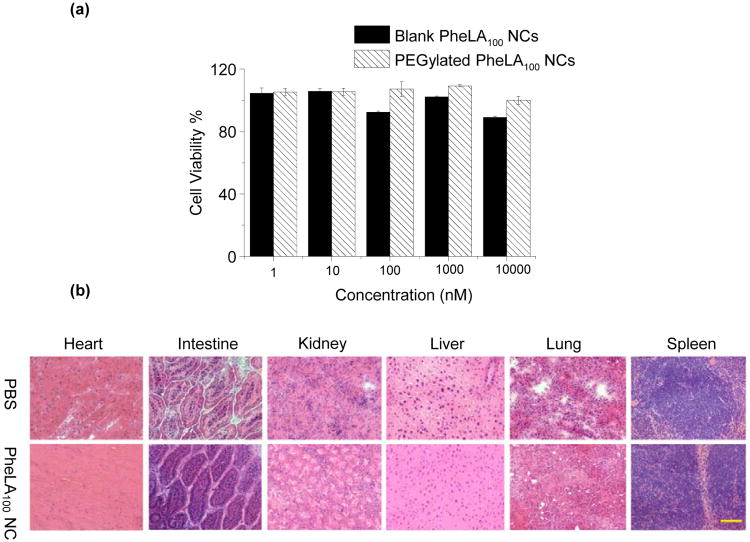

The safety profile of PheLA NC is one of significant parameters to determine its potential for drug delivery applications.43 To evaluate it, we first used MCF-7 cells to perform the MTT assay to determine the toxicity of the PheLA NCs. Figure 6a showed cell viability results of PheLA100 NCs and PEGylated PheLA100 NCs after 72-h incubation at 37 °C. As expected, both NCs did not show noticeable toxicities at a concentration up to 10 mg/mL, which is much higher than in vivo used NC concentration. Acute in vivo toxicity experiments were also performed after i.v. administration of PEGylated PheLA100 NCs in athymic nude mice at very high dose of 250 mg/kg. Mice treated with PBS were set as a control group. There was no mortality observed in any group. In addition, there were no treatment related clinical signs and change of body weights of the mice. Representative sections of various organs taken 24 h post-injections from the control mice receiving PBS and the mice receiving PEGylated PheLA100 NCs were stained by hematoxylin and eosin, and evaluated by an independent pathologist (Figure 6b). The absence of immune or inflammatory reactions after NC administration supports their lack of toxicity.

Figure 6.

(a) Cytotoxicity of blank PheLA100 NCs and PEGylated PheLA100 NCs in MCF-7 cells over 72 h at 37°C, determined by MTT assays. (b) Histopathology analysis of mouse tissues following an i.v. injection of PEGylated PheLA100 NCs via tail vein. Representative sections of various organs taken from the control mice receiving PBS and the treatment mice receiving 250 mg/kg PEGylated PheLA100 NCs 24 h post injection were stained by hematoxylin and eosin. No organs of the mice given PEGylated PheLA100 NCs showed acute inflammations.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed a strategy of using Cpt-initiated controlled ROP of Phe-OCA followed by nanoprecipitation to prepare Cpt-PheLA NCs, a class of PLA-like NCs with enhanced polymer hydrophobicity and drug covalently conjugated to the polymers via ester linkages. NCs with well-controlled properties such as predefined drug loadings, quantitative loading efficiencies, controlled release kinetics without “burst” release, and narrow size distributions are readily obtainable. This strategy can be applied to the conjugation of numerous other hydroxyl-containing drugs to polyester NPs, among which include paclitaxel, doxorubicin and docetaxel demonstrated in this study. The PEGylated PheLA NCs exhibited enhanced stability in human serum and dilute solution compared to PLA based NCs, and thereby efficiently reduced premature disassembly in circulation. Enhanced surface PEGylation facilitated protracted in vivo circulation of PheLA NCs and subsequently increased their accumulation in tumors. The PheLA NCs are novel, biocompatible nanoparticlulate delivery vehicles that can potentially be used for drug delivery applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Science Foundation (Career Program DMR-0748834), the National Institute of Health (NIH Director's New Innovator Award 1DP2OD007246-01; 1R21CA152627), and Morris Animal Foundation (D09CA-083). Q.Y. was funded at UIUC from NIH National Cancer Institute Alliance for Nanotechnology in Cancer ‘Midwest Cancer Nanotechnology Training Center’ Grant R25 CA154015A.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Experimental details, including 1H NMR spectra, 13C NMR spectra, FI-IR spectra, MALDI-TOF MS, DLS results. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Langer R. Nature. 1998;392:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, FaroKhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2006;58:1456–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner V, Dullaart A, Bock AK, Zweck A. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nbt1006-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan R. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:688–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greco F, Vicent MJ. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2009;61:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan R, Ringsdorf H, Satchi-Fainaro R. J Drug Target. 2006;14:337–341. doi: 10.1080/10611860600833856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan R. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1992;3:175–210. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musumeci T, Ventura CA, Giannone I, Ruozi B, Montenegro L, Pignatello R, Puglisi G. Int J Pharm. 2006;325:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Y, Zou J, Yu L, Jo W, Li YK, Law WC, Cheng C. Macromolecules. 2011;44:4793–4800. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lendlein A, Langer R. Science. 2002;296:1673–1676. doi: 10.1126/science.1066102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim BYS, Rutka JT, Chan WCW. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:2434–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farokhzad OC, Cheng JJ, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Jon S, Kantoff PW, Richie JP, Langer R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6315–6320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601755103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong R, Cheng JJ. Polym Rev. 2007;47:345–381. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Sung J, Luther G, Gu FX, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Radovic-Moreno AF, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Biomaterials. 2007;28:869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong R, Yala LD, Fan TM, Cheng JJ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3043–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong R, Cheng JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4744–4754. doi: 10.1021/ja8084675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong R, Cheng JJ. Macromolecules. 2012;45:2225–2232. doi: 10.1021/ma202581d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong R, Cheng JJ. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2008;47:4830–4834. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller T, Hill A, Uezguen S, Weigandt M, Goepferich A. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:1707–1718. doi: 10.1021/bm3002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyednejad H, Ghassemi AH, van Nostrum CF, Vermonden T, Hennink WE. J Control Release. 2011;152:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons TL, Baker GL. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:658–663. doi: 10.1021/bm005639+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.du Boullay OT, Bonduelle C, Martin-Vaca B, Bourissou D. Chem Commun. 2008:1786–1788. doi: 10.1039/b800852c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pounder RJ, Fox DJ, Barker IA, Bennison MJ, Dove AP. Polym Chem-Uk. 2011;2:2204–2212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu YB, Yin LC, Zhang YF, Zhang ZH, Xu YX, Tong R, Cheng JJ. Acs Macro Lett. 2012;1:441–444. doi: 10.1021/mz200165c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chamberlain BM, Cheng M, Moore DR, Ovitt TM, Lobkovsky EB, Coates GW. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3229–3238. doi: 10.1021/ja003851f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao YL, Hong H, Matson VZ, Javadi A, Xu W, Yang YA, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Nickles RJ, Cai WB, Steeber DA, Gong SQ. Theranostics. 2012;2:757–768. doi: 10.7150/thno.4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang L, Deng L. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2870–2871. doi: 10.1021/ja0255047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourissou D, Moebs-Sanchez S, Martin-Vaca B. Cr Chim. 2007;10:775–794. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong R, Christian DA, Tang L, Cabral H, Baker JR, Kataoka K, Discher DE, Cheng JJ. MRS Bulletin. 2009;34:422–431. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong R, Cheng JJ. Chem Sci. 2012;3:2234–2239. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ovitt TM, Coates GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4072–4073. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong R, Cheng JJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:111–121. doi: 10.1021/bc900356g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gref R, Minamitake Y, Peracchia MT, Trubetskoy V, Torchilin V, Langer R. Science. 1994;263:1600–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.8128245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farokhzad OC, Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Jon S, Kantoff PW, Richie JP, Langer R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6315–6320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601755103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Nostrum CF, Veldhuis TFJ, Bos GW, Hennink WE. Polymer. 2004;45:6779–6787. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. FASEB Journal. 2005;19:311–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2747rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caliceti P, Veronese FM. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2003;55:1261–1277. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(03)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kjoniksen AL, Joabsson F, Thuresson K, Nystrom B. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:9818–9825. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gref R, Minamitake Y, Peracchia M, Trubetskoy VS, Torchilin VP, Langer R. Science. 1994;263:1600–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.8128245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierri E, Avgoustakis K. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2005;75A:639–647. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao XH, Cui YY, Levenson RM, Chung LWK, Nie SM. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heath JR, Davis ME. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:251–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061506.185523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.