Abstract

Objective

Apolipoprotein A-II (apo A-II) is the second major apolipoprotein of HDLs, yet its pathophysiological roles in the development of atherosclerosis remain unknown. We aimed to examine whether apo A-II plays any role in atherogenesis and if so, to elucidate the mechanism involved.

Methods and Results

We compared the susceptibility of human apo A-II transgenic (Tg) rabbits to cholesterol diet-induced atherosclerosis with non-Tg littermate rabbits. Tg rabbits developed significantly less aortic and coronary atherosclerosis than their non-Tg littermates while total plasma cholesterol levels were similar. Atherosclerotic lesions of Tg rabbits were characterized by reduced macrophages and smooth muscle cells and apo A-II immunoreactive proteins were frequently detected in the lesions. Tg rabbits exhibited low levels of plasma CRP and blood leukocytes compared to non-Tg rabbits and HDLs of Tg rabbit plasma exerted stronger cholesterol efflux activity and inhibitory effects on the inflammatory cytokine expression by macrophages in vitro than HDLs isolated from non-Tg rabbits. In addition, β-VLDLs of Tg rabbits were less sensitive to copper-induced oxidation than β-VLDLs of non-Tg rabbits.

Conclusions

These results suggest that enrichment of apo A-II in HDL particles has atheroprotective effects and apo A-II may become a target for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Apolipoproteins, Lipoproteins, Metabolism, Transgenic rabbits

Plasma levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) are closely associated with the risk of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease1. HDLs are macromolecules and contain equal amounts of lipids and proteins2. Apolipoprotein (apo) A-I and apo A-II constitute the major protein components of HDLs, comprising 70% and 20% of the total, respectively. Although apo A-I atheroprotective functions (such as reverse cholesterol transport, anti-inflammation, and anti-oxidation) have been extensively investigated and well established3, 4, relatively little is known about apo A-II’s physiological significance in lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis5. Synthesized predominantly in the liver and small amounts made in the intestine, apo A-II is a 77 amino acid protein and exists as a disulfide-linked homodimer (MW 17.4 kDa) in plasma.

In humans, apo A-II levels do not correlate with plasma HDL-cholesterol levels, yet clinical and epidemiological studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the relationship between plasma apo A-II levels and coronary heart disease. Some studies showed that plasma apo A-II levels are inversely associated with coronary artery heart disease, as are HDL-C and apo A-I levels6, and low plasma apo A-II is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction7, 8. In addition, there was found to be a strong inverse relationship between plasma apo A-II levels and risk of future coronary artery disease in an apparently healthy population9. Nevertheless, patients who are deficient in apo A-II gene did not show any increased susceptibility to coronary artery disease10 and the −265C polymorphism in the apo A-II promoter region was shown to be associated with decreased plasma apo A-II concentration and reduced risk of coronary artery disease11.

Animal studies along with in vitro studies also generated controversial results. Most of these studies indicate that apo A-II is poorly anti-atherogenic or even pro-atherogenic because replacement of apo A-I with apo A-II impairs HDL anti-atherogenic functions12–14. This notion is supported by the finding that the expression of “murine” apo A-II gene increases aortic atherosclerosis in transgenic (Tg) mice fed even on a chow diet15. On the other hand, a study using apo A-II knock-out mice showed that murine apo A-II may have somewhat anti-atherogenic properties, such as in the maintenance of the plasma HDL pool16. Furthermore, expression of “human” apo A-II gene in Tg mice led to either increased17 or decreased18, 19 susceptibility to atherosclerosis dependent on high-fat diets. Therefore, it is still poorly understood whether human apo A-II is involved in the development of atherosclerosis or whether apo A-II-rich HDLs are beneficial for cardiovascular protection5. To investigate the pathophysiological roles of human apo A-II in lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis, our laboratory generated human apo A-II Tg rabbits, a species that normally does not have an endogenous apo A-II gene20. On a chow diet, apo A-II Tg rabbits exhibited mild hyperlipidemia (mean plasma total cholesterol in males: 74 mg/dl in Tg vs. 65 mg/dl in non-Tg; females: 129 mg/dl in Tg vs. 68 mg/dl in non-Tg) and 50% reduction of HDL-C compared with non-Tg littermates but did not develop spontaneous atherosclerosis (Koike et al. unpublished data). To examine whether human apo A-II plays any role in the development of atherosclerosis, we fed Tg and non-Tg rabbits with a cholesterol diet and compared their susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Our studies showed that expression of human apo A-II protects against cholesterol diet-induced atherosclerosis in Tg rabbits through enhancement of cholesterol efflux activity and anti-inflammatory functions.

Methods

Animals

Transgenic (Tg) Japanese white rabbits expressing the human apo A-II genomic DNA were generated in our laboratory as described previously20. Human apo A-II was mainly expressed in the liver20. Plasma levels of human apo A-II of Tg rabbits were 29.38 ± 6.3 mg/dl in males and 35.06 ± 10.45 mg/dl in females, which are similar to those of healthy humans (31~35 mg/dl). Tg rabbits along with sex- and age-matched non-Tg littermates (4–5 months old) were used for the current study. All rabbits were fed with a diet containing ~0.3% cholesterol and 3% soybean oil for 16 weeks21. AII animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Animal Care Committee of the University of Yamanashi and Saga and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health. Plasma lipids [total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C)], lipoproteins, apo A-I and apo A-II, CETP activity, whole blood cells and C-reactive protein levels along with serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 (PON1) activity and hepatic expression were measured21. Lipoproteins and HDL size were also analyzed by HPLC. See the details in supplemental data.

Analysis of aortic and coronary atherosclerosis

The aortic and coronary atherosclerosis lesions were quantified using the method as described previously21. To detect whether apo A-II was present in lesions, rabbit aortic arch along with human carotid arteries and aortas were immunohistochemically stained with goat polyclonal Ab against human apo A-II (See the supplemental data for all Abs). For negative control staining, the sections were immunostained with non-specific goat IgG as the primary Ab or without adding the primary Ab. In addition, fresh aortic specimens of rabbits and human autopsy cases were homogenized in ice-cold suspension buffer (0.02 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). 45 μg of the crude protein from each sample was fractionated by 4~20% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under the non-reducing conditions and probed with human apo A-II Ab.

Cholesterol efflux assay

To analyze whether apo A-II affects cholesterol efflux capacity of HDLs, we compared Tg-HDLs with non-Tg HDLs for their cholesterol efflux capacity in vitro. To investigate whether ATP-binding cassette transporter A-1 (ABCA-1) was involved in the cholesterol efflux mediated by apo A-II, we performed the cholesterol efflux assay using baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells stably transfected with a mifepristone-inducible vector containing an insert encoding ABCA-1 or without insert (MOCK). See the details in supplemental data.

Analysis of anti-inflammatory effects of HDLs

To examine whether apo A-II affects the anti-inflammatory functions of HDLs, we compared the Tg-HDLs with non-Tg HDLs in terms of their inhibitory effects on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) expression in vitro. U937 monocyte-derived macrophages were incubated with 20 μg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, L4391, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) alone (as a control) or LPS with different concentrations of HDL3 isolated from either Tg or non-Tg rabbits for 24 h. Then, cells were lysed and total RNA was extracted for determination of the gene expression of TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6 by real-time RT-PCR22. The primers and protocol used for RT-PCR are shown in the supplemental data.

Evaluation of apoB-containing lipoprotein oxidizability

In Tg rabbit plasma, a small amount of apo A-II was also detected in apoB-containing lipoprotein particles of Tg rabbits20; thus, we investigated whether apo A-II affects oxidation of these particles. For this experiment, we isolated four apoB-containing lipoprotein fractions [d<1.006 g/ml (β-VLDL), d=1.006~1.02 g/ml (intermediate density lipoprotein, IDL), d=1.02~1.04 g/ml (IDL and large LDL), and d=1.04~1.06 (LDL)] from cholesterol-fed Tg and non-Tg rabbits23. Each lipoprotein fraction (50 μg/ml protein) was dissolved in phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) with 0.16 M NaCl. The kinetics of copper-induced lipoprotein oxidation was determined by monitoring the change of the conjugate-diene absorbance at 234 nm at 37°C with a SpectraMax 190 Absorbance Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) as described previously24. Absorbance of lag-time, maximal oxidation speed (V max), and maximal diene concentrations were calculated for the estimation of oxidation sensitivity.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric analysis of the lesions of coronary arteries. Student’s t test was used to compare the results of other assays. In all cases, statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Plasma lipids and lipoproteins

Tg and non-Tg developed similar hypercholesterolemia (Supplemental Figure I-A, top). Compared with those of non-Tg rabbits, plasma average TG levels of Tg rabbits were high but there was no statistical significance after 10 weeks (males) or 4 weeks (females) after cholesterol diet feeding (Supplemental Figure I-A, middle). HDL-C levels of Tg rabbits were significantly lower than those of non-Tg rabbits on a chow diet as reported previously20 but did not change with a cholesterol diet. In contrast, HDL-C levels of non-Tg rabbits were decreased after cholesterol diet feeding and became lower than those of Tg rabbits at the end of the experiment (Supplemental Figure I-A, bottom). Furthermore, cholesterol diet feeding led to the reduction of plasma apo A-I levels in both non-Tg and Tg rabbits but apo A-II levels were not affected in Tg rabbits (Supplemental Figure I-B). Hepatic expression of apo A-I was low in Tg rabbits but not significantly different at 16 weeks. There was no difference in CETP activity between two groups (Supplemental Figure I-B).

Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of lipoprotein profiles revealed that Tg rabbits had less α-migrating HDLs than non-Tg rabbits while pre-β-migrating HDLs became prominent (Supplemental Figure I-C). Analysis of the density fractions of lipoproteins further confirmed that almost all HDL1–3 in Tg rabbits migrated to the pre-β position, which is different from predominant α-migrating HDL1–3 of non-Tg rabbits (Supplemental Figure I-D, left). However, TC and TG content in each density fraction was not significantly different between Tg and non-Tg rabbits (Supplemental Figure I-D, right). HPLC analysis revealed that Tg-HDLs and small sized LDLs were rich in phospholipids while chylomicrons, VLDLs and large LDLs contained similar contents of cholesteryl ester and free cholesterol (Supplemental Figure I-E). Mean size of Tg-HDL (12.61±0.81 nm, n=4) was larger than non-Tg HDL (11.38±0.79 nm, n=3). Compared with the case in non-Tg rabbits, the presence of Apo A-II (mainly distributed in HDL fractions: HDL3>HDL2>HDL1) in Tg rabbits was accompanied by reduced apo A-I contents in HDLs (Supplemental Figure I-F). ApoB and apoE contents in apoB-containing particles and HDL particles were similar in both groups.

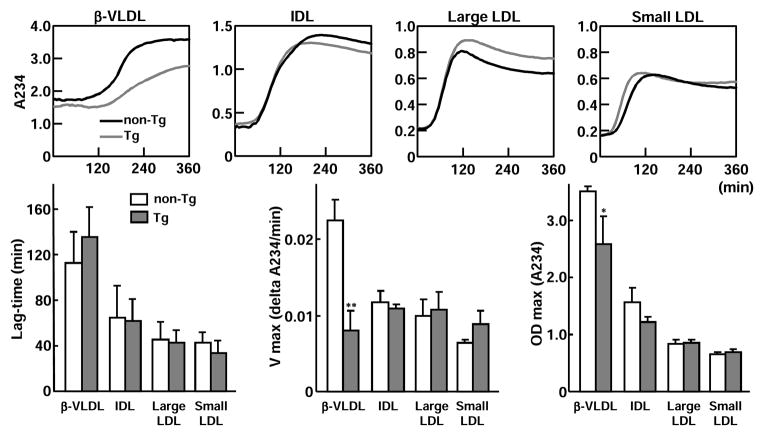

Aortic and coronary atherosclerosis

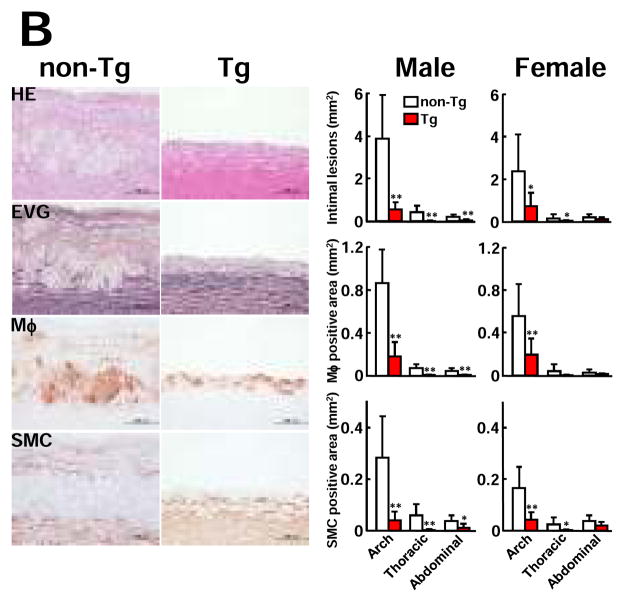

Analysis of en face aortic sudanophilic area revealed that Tg rabbits had significantly smaller atherosclerotic lesions of the whole aorta than non-Tg rabbits (Fig. 1A). The whole lesion surface area was significantly reduced by 67% in male Tg rabbits (40% ↓ in aortic arch, 87.6% ↓ in thoracic, and 81.1% ↓ in abdominal aorta vs non-Tg) and 45% in female Tg rabbits (26.8% ↓ in aortic arch, 70.5% ↓ in thoracic, and 46.5% ↓ in abdominal aorta vs. non-Tg). Histological examinations showed that the aortic lesions were mainly composed of infiltrating macrophages and smooth muscle cells intermingled with extracellular matrix (Fig. 1B, left). Morphometric analysis revealed that the microscopic atherosclerotic lesion area was significantly reduced in all parts of the aorta in Tg rabbits: 85% ↓ in aortic arch, 90% ↓ in thoracic aorta, and 73.9% ↓ in abdominal aorta in Tg males and 69.6% ↓ in aortic arch, 83% ↓ in thoracic aorta, and 40% ↓ in abdominal aorta in Tg females compared with those in each counterpart in non-Tg rabbits. Immunohistochemical staining showed that decreased aortic lesion areas in Tg rabbits were caused by marked reduction of macrophages and smooth muscle cells (Fig. 1B, right).

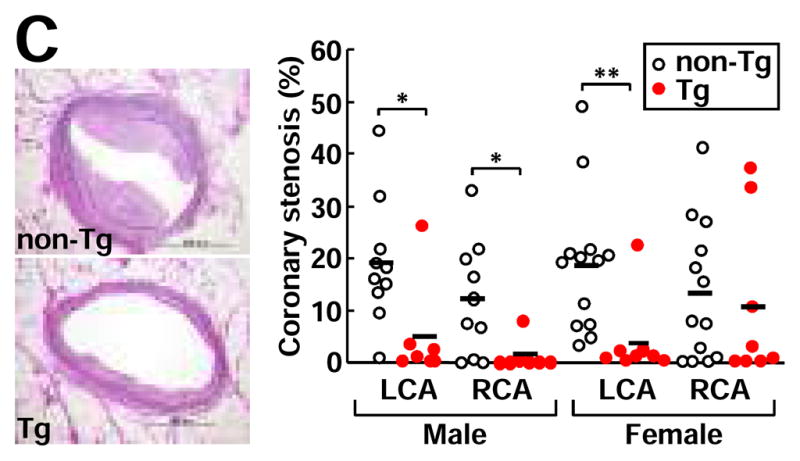

Figure 1. Analysis of atherosclerotic lesions of aorta and coronary arteries.

A, Representative photographs of pinned-out aortic trees stained with Sudan IV from non-Tg and Tg rabbits are shown (left), and aortic atherosclerotic lesions (defined by sudanophilic area) on the surface were quantified with an image analysis system (right). Each dot represents the lesion area of an individual animal.*P<0.05,**P<0.01 vs. non-Tg.

B, Representative micrographs of the aortic lesions from male non-Tg and Tg rabbits. Serial paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and elastica van Gieson (EVG) or immunohistochemically stained with mAbs against either macrophages (Mφ) or α-smooth muscle actin for smooth muscle cells (SMC) (left). Intimal lesions on EVG-stained sections and positively immunostained areas of macrophages and smooth muscle cells were quantified with an image analysis system (right). N= 7 and 13 for male Tg and non-Tg and 8 and 10 for female Tg and non-Tg. *P<0.05,**P<0.01 vs. non-Tg.

C, The heart was cut into 7 blocks21 and blocks I and II containing left and right coronary trunks were sectioned in 500 μm intervals (3 sections from each block) and stained with EVG. Representative micrographs of coronary atherosclerosis of the left main trunks stained by EVG (left). Coronary stenosis =lesion area/total lumen area x100(%) was measured and is expressed as percentage (right). LCA: left coronary artery trunks; RCA: right coronary artery trunks. *P<0.05,**P<0.01 vs. non-Tg.

In addition to aorta, male Tg rabbits had significantly smaller lesions in both left and right coronary arteries whereas in female Tg rabbits, the left coronary artery stenosis was significantly less severe than in non-Tg rabbits (Fig. 1C).

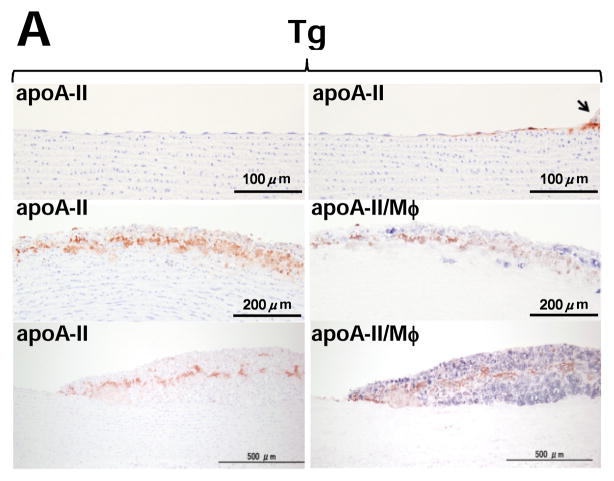

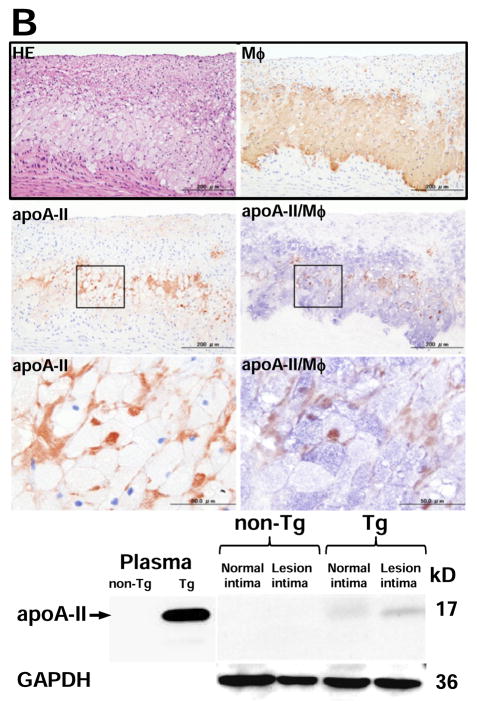

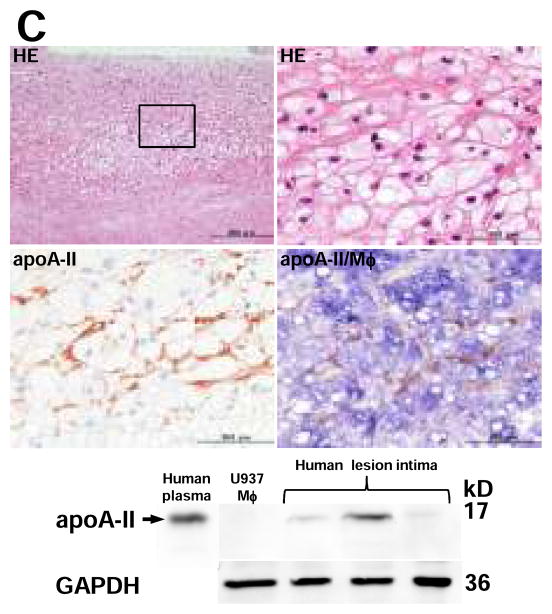

Detection of apo A-II immunoreactive proteins in the lesions

Although apo A-II was not found in the non-lesional area of Tg rabbits, apo A-II was detected beneath endothelial cells adjacent to the lesions of aorta (Fig. 2A, top). Apo A-II was often observed in the fatty streak where apo A-II was located around macrophages as shown by double immunostaining with both apo A-II and macrophage Abs (Fig. 2A, middle and bottom). The specificity of apo A-II immunostaining was confirmed by the observation that (1) apo A-II was not stained in non-Tg aortic lesions, and (2) apo A-II was not stained when the primary Ab was omitted or replaced with a non-specific goat IgG in the lesions of Tg rabbits (Supplemental Figure II). To investigate the interactions between apo A-II and foam cells, we examined foam-cell rich lesions and found that apo A-II-immunoreactive proteins were mainly located around macrophage-derived foam cells (Fig. 2B, top). The presence of apo A-II dimer (17kDa) in the lesions of Tg rabbits was further confirmed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting in the aortic intima of Tg rabbits but not in non-Tg rabbits (Fig. 2B, bottom). We also examined the lesions of human aortic atherosclerosis obtained from autopsy. Similar to the lesions of Tg rabbits, apo A-II-immunoreactive proteins were detected in human aortic lesions by both immunohistochemical staining and Western blotting (Fig. 2C). To exclude the possibility that apo A-II proteins seen in the lesions were produced by vascular wall cells, we examined human apo A-II gene expression in normal intima and lesional intima of Tg rabbits by real-time RT-PCR22, but did not detect any signals (data not shown).

Figure 2. Demonstration of apo A-II immunoreactive proteins in lesions of Tg rabbit and human atherosclerosis.

Representative micrographs of normal intima and early-stage lesions (A), and fatty streak (foam cell-rich lesions) (B top) of Tg rabbits. Serial paraffin sections were stained with HE or Abs against human apo A-II alone or double-stained with apoA-II (stained as red) and macrophage (stained as blue) Abs (labeled as apo A-II/Mφ%. Normal intima and atherosclerotic intima (grossly) of Tg rabbits were analyzed by 4–20% SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions and followed by immunoblotting using human apo A-II polyclonal Ab (B bottom).

C, Representative micrographs of advanced lesion from human carotid artery (top). Serial paraffin sections of the lesions were stained with HE, polyclonal Ab against human apo A-II, and double staining with Abs against apo A-II (stained as red) and human macrophage (stained as blue).

Human aortic atherosclerotic intima of three autopsy cases was analyzed by 4–20% SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions and followed by immunoblotting using human apo A-II polyclonal Ab (bottom). Proteins isolated from U937-derived macrophages were used as the negative control and 1 μL of human plasma was used as the positive control. GAPDH proteins are shown at the bottom to indicate the relative amount of proteins loaded in each lane.

Anti-inflammatory effects of apo A-II-rich HDLs

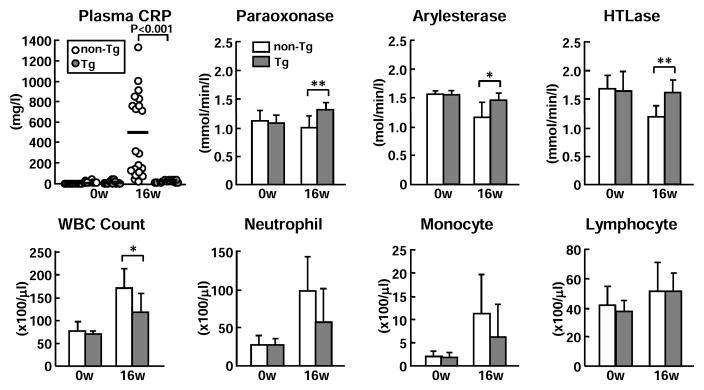

The finding that apo A-II expression in Tg rabbits led to the reduction of atherosclerosis prompted us to examine the possible mechanisms involved. We first investigated whether apoA-II affects inflammatory state. We measured plasma CRP levels (a robust inflammatory marker) and serum PON1 activity, an enzyme present in HDLs that is important for their anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidation functions. Tg rabbits exhibited significantly lower levels of plasma CRP but higher PON1 activity than non-Tg littermates after cholesterol diet feeding at 16 weeks (Fig. 3 top). We also measured white blood cell numbers. Although there was no difference between Tg and non-Tg rabbits on a chow diet, Tg rabbits had significantly fewer total white blood cells with 42% ↓ neutrophils (p=0.08) and 44% ↓ monocytes (p=0.25) but no changes in lymphocytes than those in non-Tg rabbits on a cholesterol diet at 16 weeks (Fig. 3, bottom). There was not difference in platelet and red blood cell counts between two groups (data not shown).

Figure 3. Analysis of plasma CRP, PON1 activity (top) and white blood cells (bottom).

Plasma levels of CRP of non-Tg (white dot) and Tg rabbits (gray dots) were measured by ELISA. Serum PON1 activity was measured using three different substrates. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.*P<0.05,**P<0.01 vs. non-Tg. N= 6 ~13 from each group containing both males and females.

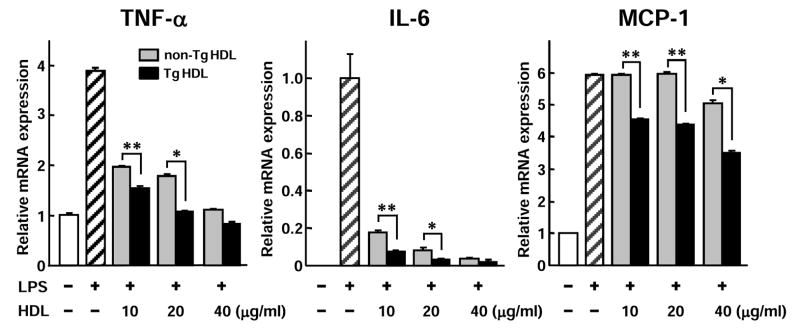

Addition of either Tg-HDLs or non-Tg HDLs at doses of 10~40 μg/ml significantly inhibited the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Fig. 4). When a comparison was made between Tg and non-Tg HDLs in regard to their suppressive capacity, Tg-HDLs had significantly stronger effects on the TNF-α and IL-6 expression than did non-Tg HDLs. Furthermore, Tg-HDLs showed inhibitory effects on MCP-1 expression, which was not obvious in non-Tg HDLs.

Figure 4. Inhibitory effects of HDLs on cytokine expression in macrophages.

U937 macrophages were treated with LPS or in the presence of HDL3 isolated from either non-Tg or Tg rabbit plasma for 24 h and mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 was measured by real-time RT-PCR. HDLs were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and shown in the middle insert. Representative data from three separate experiments are shown. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.*P<0.05,**P<0.01 vs. non-Tg.

Cholesterol efflux capacity

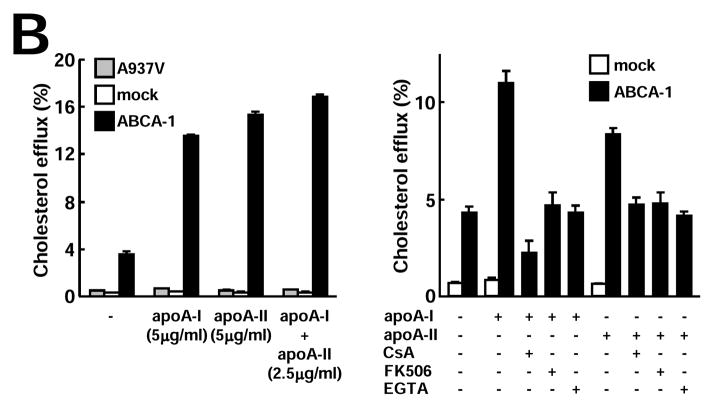

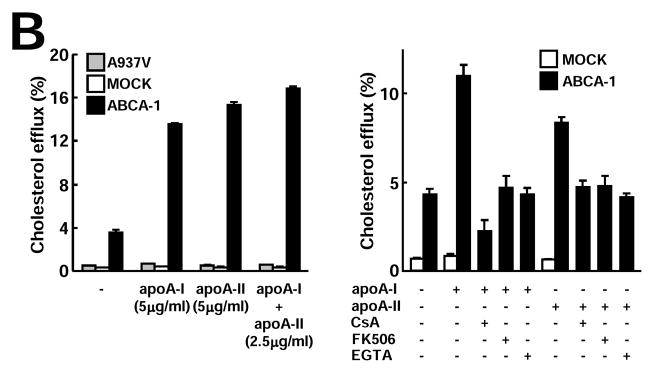

Next, we examined whether there was any difference between Tg-HDLs (containing both apo A-I and apo A-II) and non-Tg HDLs (containing only apo A-I particles) in terms of their cholesterol efflux ability. Clearly, Tg-HDLs (both HDL2 and HDL3) were more efficient in removing cellular cholesterol from THP-1 macrophages than non-Tg HDLs at all doses (10, 30, and 100 μg/ml) (Fig. 5A). We further compared the purified apo A-I and apo A-II without lipids and showed that, among three batches of apo A-I and two batches of apo A-II, their cholesterol efflux capacities were almost identical (Supplemental Figure III). In addition to THP-1 macrophages, similar results were also obtained when mouse RAW264.7 macrophages (either unloaded or loaded with cholesterol) were used (data not shown). Using ABCA-1-transfected BHK cells, we further demonstrated that functional ABCA-1 was essential for both apo A-I- and apo A-II-mediated cholesterol efflux. Both mock and cells expressing an ABCA-1-defective mutant (A937V) failed to efflux cholesterol under identical conditions (Fig. 5B). In addition, apoA-I and apoA-II did not seem to interfere with each other because apoA-I/apoA-II combination removed cholesterol as efficiently as apoA-I or apoA-II alone (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Figure 5A. Analysis of cholesterol efflux capacity of HDLs

Apo A-I and apo A-II contents were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (top). Each lane represents one sample from one rabbit. [3H] acetylated-LDL-loaded human THP-1 macrophages were incubated with different doses of HDLs for 24 h and data are expressed as percent cholesterol effluxed (bottom). N=3 for each group. **P<0.01,***P<0.001 vs. non-Tg.

Figure 5B. ABCA-1 is required for apo A-I- and apo A-II-mediated cholesterol efflux

Cholesterol efflux assay was performed using BHK cells transfected with either mock or ABCA-1 vectors as described. ABCA-1 is essential for both apo A-I- and apo A-II-mediated cholesterol efflux (left). In the presence of ABCA-1 inhibitors cyclosporin A (CsA), ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), and tacrolimus (FK506), both apo A-I- and apo A-II-mediated cholesterol efflux activity in ABCA-1-transfected BHK cells was inhibited (right). Representative data of three independent experiments are shown.

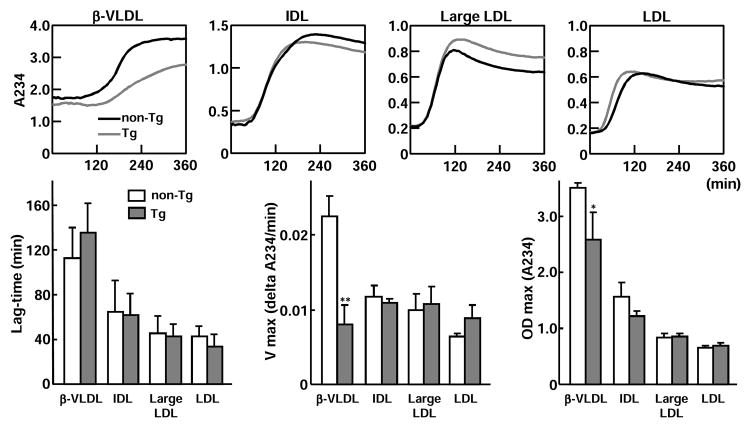

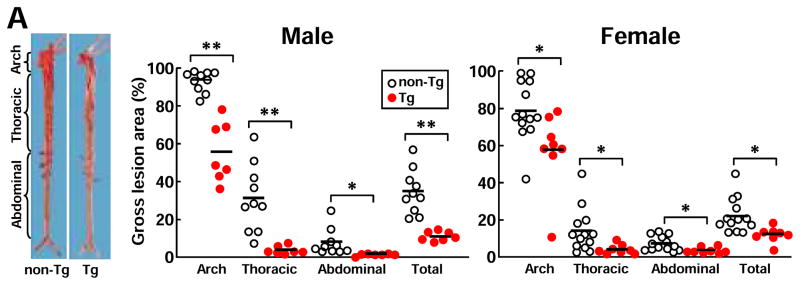

ApoB-containing lipoprotein oxidizability

Because a small amount of apo A-II is present in apoB-containing particles (Supplemental Figure IV), we next examined the possible role of apo A-II in apoB-containing lipoprotein oxidation. β-VLDL, the major atherogenic lipoprotein in cholesterol-fed rabbits, was the most sensitive to oxidation among the four apoB-containing lipoprotein fractions. Compared with that of non-Tg rabbits, oxidizability of β-VLDL but not IDL and LDL fractions of Tg rabbits was significantly diminished (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Analysis of apoB-containing lipoprotein oxidizability.

Four apoB-containing lipoprotein fractions (β-VLDL, IDL, large LDL, and LDL) isolated from cholesterol-fed non-Tg and Tg rabbits were used for evaluation of copper-induced lipoprotein oxidation by monitoring the change of the conjugate-diene absorbance at 234 nm. Representative dynamic changes are shown on the top and absorbance of lag-time, maximal oxidation speed (V max), and maximal diene concentrations are shown at the bottom. N=3 for each group and data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P<0.05,**P<0.01 vs. non-Tg.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that human apo A-II, the second major apolipoprotein of HDLs, protected against cholesterol-diet induced atherosclerosis in Tg rabbits. Expression of human apo A-II at the physiological levels of healthy humans significantly suppressed the development of aortic atherosclerosis by 67% in male and 45% in female Tg rabbits compared with that in non-Tg rabbits. Interestingly, coronary atherosclerosis was also significantly decreased in Tg rabbits. Atherosclerotic lesions of Tg rabbits were characterized by reduced macrophages and smooth muscle cells. This finding was initially surprising and unexpected because apo A-II expression in Tg rabbits led to mild elevation of plasma lipids and low HDL-C due to inhibition of lipoprotein lipase activity20. In spite of this, under similar “atherogenic” hypercholesterolemia, overall effects of human apo A-II is atheroprotective as shown in the current study. Several mechanisms may be operative underlying the anti-atherogenic functions of apo A-II in Tg rabbits. The first possible mechanism for apo A-II anti-atherogenicity may be attributed to its potent anti-inflammatory activity. This contention is supported by the fact that Tg rabbits exhibited lower levels of inflammatory marker, CRP, and blood leukocytes (both neutrophils and monocytes) along with high PON1 activity compared to non-Tg rabbits. Furthermore, Tg HDLs showed stronger suppressive activity on inflammatory cytokine expression of macrophages in vitro than did non-Tg HDLs. This finding is in contrast to a report that mouse apo A-II-rich HDLs of Tg mice could potentially be pro-inflammatory13. We speculate that such a difference may be caused by different apo A-IIs expressed in different animals (i.e. human dimer apo A-II in Tg rabbits vs. murine monomer apo A-II in Tg mice). In support of our observations, Yamashita et al. recently reported that plasma apo A-II is a potent anti-inflammatory bioactive protein because the administration of apo A-II led to the reduction of leukocyte infiltration and production of T cell-related cytokines in Con A-induced hepatitis in mice25. Because Tg-HDLs are rich in phospholipids, it is necessary to investigate whether apo A-II also affects LPS-binding activity of HDL in future.

Secondly, we found that HDLs isolated from Tg rabbits show increased cholesterol efflux capacity from macrophages compared with HDLs from non-Tg rabbits in vitro, suggesting that enrichment of apo A-II in HDL particles favors cholesterol efflux and thus inhibits foam cell formation in Tg rabbits. We also compared human lipid-free apo A-II with apo A-I regarding cholesterol efflux activity and found that apo A-II is actually as efficient as apo A-I. Furthermore, functional ABCA-1 is required for lipid-free apo A-II-mediated cholesterol efflux, identical to apo A-I. Taken together, these data indicate that lipid-free apo A-II functions similarly to apo A-I in terms of cholesterol efflux via an ABCA-1-mediated mechanism26. Moreover, there is a synergistic effect in HDL particles for cholesterol efflux when both apo A-I and apo A-II are present as shown in Tg HDLs. This finding supports the results showing that the plasma of human apo A-II Tg mice exhibited greater cholesterol efflux from J774 macrophages27. It has been controversial whether enrichment or replacement of apo A-I with apo A-II impairs HDL cholesterol efflux functions. Huang et al. purified α-migrating HDLs containing both apo A-I and apo A-II (Lp-A-I/A-II) from human plasma by immunosubtracting 2D-PAGE and showed that Lp-A-I/A-II particles are less efficient for cholesterol efflux than Lp-A-I particles in fibroblasts, whereas other studies failed to demonstrate differences in the ability of LpA-I and LpA-I/A-II to remove cholesterol from hepatoma cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and bovine endothelial cells28, 29. In addition, enrichment of apo A-II in Tg mouse HDLs did not affect the ability for cholesterol efflux from human macrophages compared with that in HDLs of wild-type mouse13. It has been reported that SR-B1 removes cholesteryl esters from Lp-A-I/A-II particles more effectively than from Lp-A-I particles30.

Because a small amount of apo A-II was also contained in apo-B-containing particles of Tg rabbits, it is likely that apo A-II affects their susceptibility to oxidation. We found that β-VLDL (the major atherogenic lipoprotein in cholesterol-fed animals) isolated from Tg rabbits showed less susceptibility to copper-induced oxidation than β-VLDL of non-Tg rabbits, which serves as another molecular mechanism for the athero-protection shown in human apo A-II Tg rabbits. Of note, a particularly interesting finding of the current study is the first demonstration of apo A-II immunoreactive proteins in the lesions of both Tg rabbit and human atherosclerosis. In the lesions, apo A-II is mainly present extracellularly in intimate association with macrophages. It has been reported that apo A-II exerts an important role in HDL binding and selective lipid uptake through SR-B1 and CD36 receptors31. Nevertheless, how apo A-II enters the arterial intima and what pathophysiological roles apo A-II plays in the lesions deserve further investigation. In the future study, it is necessary to clarify whether apoA-II exerts anti-atheorgenic effects in hepatic lipase Tg rabbits because normal rabbits are considered having low hepatic lipase activity32.

In conclusion, our studies provide evidence that human apo A-II, the second major apolipoprotein of HDLs has a potent anti-atherogenic function through several mechanisms. Enrichment of apo A-II in HDLs promotes cholesterol efflux from the cells, and inhibits inflammation and oxidation. It remains to be verified; however, whether apo A-II may become a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of atherosclerosis like apo A-I mimetic peptides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan (71790514, 19390099, 21659078, and 22390068 to JF), National Institutes of Health (HL088391, HL068878, HL105114 to YEC), a research grant for cardiovascular disease from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, and a research grant from AstraZeneca (JF). YEC is an established investigator of the American Heart Association (0840025N).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977;62:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rader DJ. Molecular regulation of HDL metabolism and function: implications for novel therapies. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3090–3100. doi: 10.1172/JCI30163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linsel-Nitschke P, Tall AR. HDL as a target in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:193–205. doi: 10.1038/nrd1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degoma EM, Rader DJ. Novel HDL-directed pharmacotherapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:266–277. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan DC, Ng TW, Watts GF. Apolipoprotein A-II: evaluating its significance in dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis. Ann Med. 2012;44:313–324. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.573498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller NE. Associations of high-density lipoprotein subclasses and apolipoproteins with ischemic heart disease and coronary atherosclerosis. Am Heart J. 1987;113:589–597. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buring JE, O’Connor GT, Goldhaber SZ, Rosner B, Herbert PN, Blum CB, Breslow JL, Hennekens CH. Decreased HDL2 and HDL3 cholesterol, Apo A-I and Apo A-II, and increased risk of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1992;85:22–29. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler K, Hoffmann MM, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B, Boehm BO, Winkelmann BR, März W, Scharnagl H. Apolipoprotein A-II Is a negative risk indicator for cardiovascular and total mortality: findings from the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1405–1406. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.103929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birjmohun RS, Dallinga-Thie GM, Kuivenhoven JA, Stroes ES, Otvos JD, Wareham NJ, Luben R, Kastelein JJ, Khaw KT, Boekholdt SM. Apolipoprotein A-II is inversely associated with risk of future coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;116:2029–2035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deeb SS, Takata K, Peng RL, Kajiyama G, Albers JJ. A splice-junction mutation responsible for familial apolipoprotein A-II deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:822–827. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao J, Zhang F, Wiltshire S, Hung J, Jennens M, Beilby JP, Thompson PL, McQuillan BM, McCaskie PA, Carter KW, Palmer LJ, Powell BL. The apolipoprotein AII rs5082 variant is associated with reduced risk of coronary artery disease in an Australian male population. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, von Eckardstein A, Wu S, Assmann G. Cholesterol efflux, cholesterol esterification, and cholesteryl ester transfer by LpA-I and LpA-I/A-II in native plasma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1412–1418. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.9.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castellani LW, Navab M, Van Lenten BJ, Hedrick CC, Hama SY, Goto AM, Fogelman AM, Lusis AJ. Overexpression of apolipoprotein AII in transgenic mice converts high density lipoproteins to proinflammatory particles. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:464–474. doi: 10.1172/JCI119554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribas V, Sánchez-Quesada JL, Antón R, Camacho M, Julve J, Escolà-Gil JC, Vila L, Ordóñez-Llanos J, Blanco-Vaca F. Human apolipoprotein A-II enrichment displaces paraoxonase from HDL and impairs its antioxidant properties: a new mechanism linking HDL protein composition and antiatherogenic potential. Circ Res. 2004;95:789–797. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146031.94850.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warden CH, Hedrick CC, Qiao JH, Castellani LW, Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis in transgenic mice overexpressing apolipoprotein A-II. Science. 1993;261:469–472. doi: 10.1126/science.8332912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weng W, Breslow JL. Dramatically decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol, increased remnant clearance, and insulin hypersensitivity in apolipoprotein A-II knockout mice suggest a complex role for apolipoprotein A-II in atherosclerosis susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14788–14794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escolà-Gil JC, Marzal-Casacuberta A, Julve-Gil J, Ishida BY, Ordóñez-Llanos J, Chan L, González-Sastre F, Blanco-Vaca F. Human apolipoprotein A-II is a pro-atherogenic molecule when it is expressed in transgenic mice at a level similar to that in humans: evidence of a potentially relevant species-specific interaction with diet. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tailleux A, Bouly M, Luc G, Castro G, Caillaud JM, Hennuyer N, Poulain P, Fruchart JC, Duverger N, Fiévet C. Decreased susceptibility to diet-induced atherosclerosis in human apolipoprotein A-II transgenic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2453–2458. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultz JR, Verstuyft JG, Gong EL, Nichols AV, Rubin EM. Protein composition determines the anti-atherogenic properties of HDL in transgenic mice. Nature. 1993;365:762–764. doi: 10.1038/365762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koike T, Kitajima S, Yu Y, et al. Expression of human apoAII in transgenic rabbits leads to dyslipidemia: a new model for combined hyperlipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:2047–2053. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.190264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koike T, Kitajima S, Yu Y, Nishijima K, Zhang J, Ozaki Y, Morimoto M, Watanabe T, Bhakdi S, Asada Y, Chen YE, Fan J. Human C-reactive protein does not promote atherosclerosis in transgenic rabbits. Circulation. 2009;120:2088–2094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.872796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Y, Koike T, Kitajima S, Liu E, Morimoto M, Shiomi M, Hatakeyama K, Asada Y, Wang KY, Sasaguri Y, Watanabe T, Fan J. Temporal and quantitative analysis of expression of metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their endogenous inhibitors in atherosclerotic lesions. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:1503–1516. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan J, Ji ZS, Huang Y, de Silva H, Sanan D, Mahley RW, Innerarity TL, Taylor JM. Increased expression of apolipoprotein E in transgenic rabbits results in reduced levels of very low density lipoproteins and an accumulation of low density lipoproteins in plasma. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2151–2164. doi: 10.1172/JCI1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa T, Kitajima S, Liang J, Koike T, Wang X, Sun H, Okazaki M, Morimoto M, Shikama H, Watanabe T, Yamada N, Fan J. Overexpression of lipoprotein lipase in transgenic rabbits leads to increased small dense LDL in plasma and promotes atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2004;84:715–726. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita J, Iwamura C, Sasaki T, Mitsumori K, Ohshima K, Hada K, Hara N, Takahashi M, Kaneshiro Y, Tanaka H, Kaneko K, Nakayama T. Apolipoprotein A-II suppressed concanavalin A-induced hepatitis via the inhibition of CD4 T cell function. J Immunol. 2011;186:3410–3420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remaley AT, Stonik JA, Demosky SJ, Neufeld EB, Bocharov AV, Vishnyakova TG, Eggerman TL, Patterson AP, Duverger NJ, Santamarina-Fojo S, Brewer HB., Jr Apolipoprotein specificity for lipid efflux by the human ABCAI transporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:818–823. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fournier N, Cogny A, Atger V, Pastier D, Goudouneche D, Nicoletti A, Moatti N, Chambaz J, Paul JL, Kalopissis AD. Opposite effects of plasma from human apolipoprotein A-II transgenic mice on cholesterol efflux from J774 macrophages and Fu5AH hepatoma cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:638–643. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000013023.11297.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oikawa S, Mendez AJ, Oram JF, Bierman EL, Cheung MC. Effects of high-density lipoprotein particles containing apo A-I, with or without apo A-II, on intracellular cholesterol efflux. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1165:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson WJ, Kilsdonk EP, van Tol A, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. Cholesterol efflux from cells to immunopurified subfractions of human high density lipoprotein: LP-AI and LP-AI/AII. J Lipid Res. 1991;32:1993–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Beer MC, Durbin DM, Cai L, Mirocha N, Jonas A, Webb NR, de Beer FC, van Der Westhuyzen DR. Apolipoprotein A-II modulates the binding and selective lipid uptake of reconstituted high density lipoprotein by scavenger receptor BI. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15832–15839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Beer MC, Castellani LW, Cai L, Stromberg AJ, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR. ApoA-II modulates the association of HDL with class B scavenger receptors SR-BI and CD36. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:706–715. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300417-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan J, Wang J, Bensadoun A, Lauer SJ, Dang Q, Mahley RW, Taylor JM. Overexpression of hepatic lipase in transgenic rabbits leads to a marked reduction of plasma high density lipoproteins and intermediate density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8724–8728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.