Abstract

As populations diverge, genomic regions associated with adaptation display elevated differentiation. These genomic islands of adaptive divergence can inform conservation efforts in exploited species, by refining the delineation of management units, and providing genomic tools for more precise and effective population monitoring and the successful assignment of individuals and products. We explored heterogeneity in genomic divergence and its impact on the resolution of spatial population structure in exploited populations of Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua, using genome wide expressed sequence derived single nucleotide polymorphisms in 466 individuals sampled across the range. Outlier tests identified elevated divergence at 5.2% of SNPs, consistent with directional selection in one-third of linkage groups. Genomic regions of elevated divergence ranged in size from a single position to several cM. Structuring at neutral loci was associated with geographic features, whereas outlier SNPs revealed genetic discontinuities in both the eastern and western Atlantic. This fine-scale geographic differentiation enhanced assignment to region of origin, and through the identification of adaptive diversity, fundamentally changes how these populations should be conserved. This work demonstrates the utility of genome scans for adaptive divergence in the delineation of stock structure, the traceability of individuals and products, and ultimately a role for population genomics in fisheries conservation.

Keywords: Atlantic cod, divergent selection, genome scan, outlier loci, population genomics, single nucleotide polymorphism

Introduction

The presence of adaptive diversity is a principle consideration in the management and conservation of exploited species (Fraser and Bernatchez 2001; Hilborn et al. 2003; Schindler et al. 2010). Despite its recognized importance, knowledge of adaptive diversity is presently lacking in many exploited species, often impeding management efforts. Recent studies examining genomewide variation among individuals and populations indicate variable levels of differentiation across the genome, referred to as ‘genomic islands of divergence’ (Wu 2001; Turner et al. 2005; Nosil et al. 2009). And although a suite of factors may influence the distribution and size of divergent regions including genetic conflict, genetic drift, mutation rates, and chromosomal structure, divergent selection and adaptation are often implicated (Nosil et al. 2009; Feder and Nosil 2010; Bierne et al. 2011). A link between divergent regions and adaption is supported by associations with previously identified QTL and annotated genes (e.g. Rogers and Bernatchez 2007; Via and West 2008), or environmental gradients (e.g. Nielsen et al. 2009b; Bradbury et al. 2010). Moreover, these genomic regions may be enriched for nonsynonymous substitutions (Hancock et al. 2011) or display parallel associations with independent habitats (Bradbury et al. 2010; Deagle et al. 2011). Genome scans for signatures of directional selection may thus provide direct insight into the presence of adaptive divergence often unobtainable with other methods and central to the successful management of wild populations.

The ability to resolve genomic regions associated with adaptation (e.g. Fournier-Level et al. 2011; Hancock et al. 2011) provides multiple opportunities for insight into the scales of ecological and evolutionary population dynamics, both directly applicable to management and conservation efforts (e.g. Schindler et al. 2010; Nielsen et al. 2012). First, as conservation units such as evolutionarily significant units (ESUs) are often defined as a population or group of populations possessing both demographic isolation and adaptive or ecological significance (Waples 1995; Fraser and Bernatchez 2001), examinations of genomic regions associated with adaptation can directly inform ESU designation (Funk et al. 2012). In conjunction with improved resolution of population structure, loci associated with signatures of adaptive divergence and increased population differentiation can enhance individual assignment success (e.g. Nielsen et al. 2012). For instance, gene-associated markers displaying signatures of directional selection provided unprecedented power to assign individuals and products to the population of origin in several commercially important European fish species (Nielsen et al. 2012). Finally, the identification of genomic regions associated with functional variation provides the opportunity to monitor the population responses to factors such as climate or harvest pressure (e.g. Schwartz et al. 2007). However, the tools to achieve these goals for many groups of commercially exploited marine fishes have thus far remained elusive, limited by apparent widespread genetic homogeneity (Hauser and Carvalho 2008).

Our study integrates SNP-based genome scans for elevated divergence in a marine fish, Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), with linkage mapping information to demonstrate the utility of genome scans to resolve adaptive divergence and to inform management and conservation of exploited marine species. First, we use tests for selection and linkage information to explore the genomic distribution of outliers identified as potentially experiencing directional selection. Second, we examine the subsequent impact of adaptive variation on the resolution of spatial population structure and assignment success in Atlantic cod. We build on a previous study (Bradbury et al. 2010) that examined loci displaying evidence of environmentally associated selection in parallel with either side of the Atlantic in a subset of these loci (n = 40) and populations (n = 14). Here, we examine the distribution of divergence and its consequences for the resolution of spatial structure, providing critical insight into the geographic scale of population dynamics in exploited populations of Atlantic cod.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and location characteristics

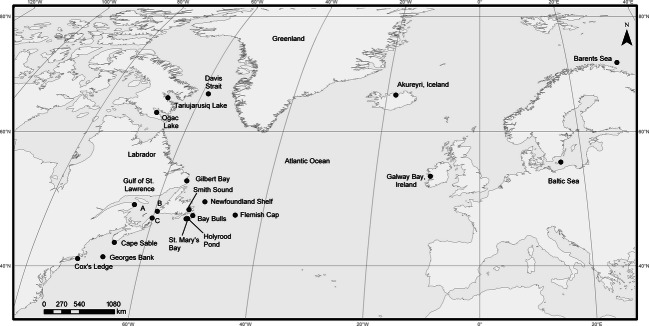

We sampled individuals (N = 466) from 23 locations throughout the North Atlantic from 1996 to 2007 (See Fig. 1 for approximate locations, Table S1) during the course of scientific surveys or commercial harvest. With the exception of Arctic and northern locations where sampling was restricted to summer months, most fish were in spawning condition. Specific details regarding some samples and locations were published elsewhere (Taggart and Cook 1996; Hubert et al. 2009; Bradbury et al. 2010; Hubert et al. 2010) and a subset of these samples analyzed previously (Bradbury et al. 2010, 2011). We isolated DNA from these samples from ethanol-preserved fin clips using a modification of a previously published glass milk procedure (Elphinstone et al. 2003).

Figure 1.

Map of sampling locations of Atlantic cod from across its geographic range. See Table S1 for further sample details.

SNP genotyping and linkage

Details on SNP development and genotyping were provided elsewhere (Bowman et al. 2010; Hubert et al. 2010). We chose 1536 SNPs (GenBank dbSNP under accession numbers ss131570222–ss131571915) for genotyping and assessed linkage using JoinMap4® (Van Ooijen 2006) and three families, including parents and F1 offspring (Borza et al. 2010). Linkage maps were generated using the group function of JoinMap4®, a LOD cutoff value of 5.0 or greater, and Haldane's mapping function. To allow the outlier loci to be mapped, we allowed JoinMap4® to force additional markers with a lower goodness of fit into the map, producing a map with 1295 SNPs (see Supporting Information for further details). Because previous work suggests that both PanI and hemoglobin beta 1 in cod are under selection (Case et al. 2005; Andersen et al. 2009), we included SNPs associated with these genes for comparison on the linkage map (see Borza et al. 2010 for SNP details).

Data analysis

Estimates of heterozygosity, population differentiation (FST, both locus specific and global), and tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were performed using ARLEQUIN (Excoffier and Lischer 2010). For outlier detection, we used a Bayesian approach that directly estimates the posterior probability that a given locus is under selection by defining two alternative models, one with and one without the effect of selection. The respective posterior probabilities of each model are estimated using a reversible jump Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach as implemented in the software BAYESCAN v2.01 (Foll and Gaggiotti 2008). Because geographic isolation or demographic structure may contribute to false positives (Foll and Gaggiotti 2008), we ran the analysis for the entire dataset (See Supporting Information) and then assessed population structure using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) with initial significant outliers removed. The BAYESCAN analysis was then repeated on the large dominant cluster representing the western Atlantic using all loci. We compared the BAYESCAN results to an alternative method for outlier identification using a hierarchical island model (number of groups = 10) to generate the distribution of genetic variation within and among populations as implemented in ARLEQUIN (Excoffier and Lischer 2010).

Principle coordinate analysis was carried out using GenAlEx (vers.6.1; Peakall and Smouse 2006). Because each SNP likely represents a single gene and linkage disequilibrium may result from selection associated with adaptive divergence, we did not exclude loci that displayed correlations in allele frequency. We previously showed that linkage disequilibrium among outliers occurs even among chromosomes in this SNP panel (Bradbury et al. 2010). Distance among samples on the PCoA was calculated as the Euclidean distance among sample average values. We took geographic distance among samples as the shortest distance among sample locations along the continental shelves. We then used Bayesian clustering in BAPS (Corander and Marttinen 2006) to examine the number of groups (K) consistent with multilocus genetic data. This approach uses a stochastic optimization procedure rather than MCMC to identify the number of groups. We ran BAPS with the predefined number of clusters = 2–25 and replicated five times to ensure the stability of results. Assignment power of the SNP panel was evaluated using the proportion of successful identifications to the population of origin identified using GeneClass2.0 (Piry et al. 2004) and a subset of individuals (Anderson 2010). We used a Bayesian approach for assignment (Rannala and Mountain 1997) with resampling (Paetkau et al. 2004), and assignment success was evaluated for the western Atlantic using populations or groups identified in clustering analyses above and separately for all SNPs and only the neutral SNPs.

Results

Although we attempted genotyping of the 23 population samples (466 individuals) for 1536 previously identified informative loci, the failure of some assays reduced successful loci to 1405. Observed (expected) heterozygosity overall was 0.307 (0.301) and ranged from 0.222 (0.220) in the Baltic Sea sample to 0.385 (0.360) for the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Georges Bank (See Table S1). The percentage of polymorphic loci in each sample varied from 69.0% in the Baltic to 99.3% in the Cape Sable sample (Table S1). Tests for departures from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium indicated that approximately 1% of population/locus combinations (n = 33 720) were significant at α = 0.01. Locus-specific FST values were as high as 0.60 for some loci; the median and maximum pairwise population FST values were 0.13 and 0.50, respectively.

Tests for the signatures of selection identified multiple loci putatively experiencing directional selection. Using BAYESCAN and focusing on the western Atlantic, and excluding isolated populations (i.e. Arctic lakes and Gilbert Bay; see Materials and methods), we identified 73 loci potentially experiencing directional selection at a false discovery rate of 1% (Fig. 2A). In comparison, the hierarchical island model-based test implemented in ARLEQUIN (Excoffier et al. 2009) using all samples identified selection in 89 loci at α = 0.01 (Fig. 2B). Only six of the loci identified by BAYESCAN were not significant in ARLEQUIN. Given the similarity among the test results and lower types I and II errors in BAYESCAN (Narum and Hess 2012), we chose the loci identified using BAYESCAN for subsequent analysis.

Figure 2.

Tests for the presence of selection on SNPs genotyped in Atlantic cod from the western Atlantic. (A) Results of Bayesian tests for selection using BAYESCAN v2.01, and (B) results from a hierarchical island model-based test for selection, using ARLEQUIN v3.55. Gray dots represent outliers identified using BAYESCAN and outliers identified at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. The dotted line in (A) represents the threshold for neutral loci, and in (B), the dashed and dotted lines represent the 50, 95, and 99 percentiles.

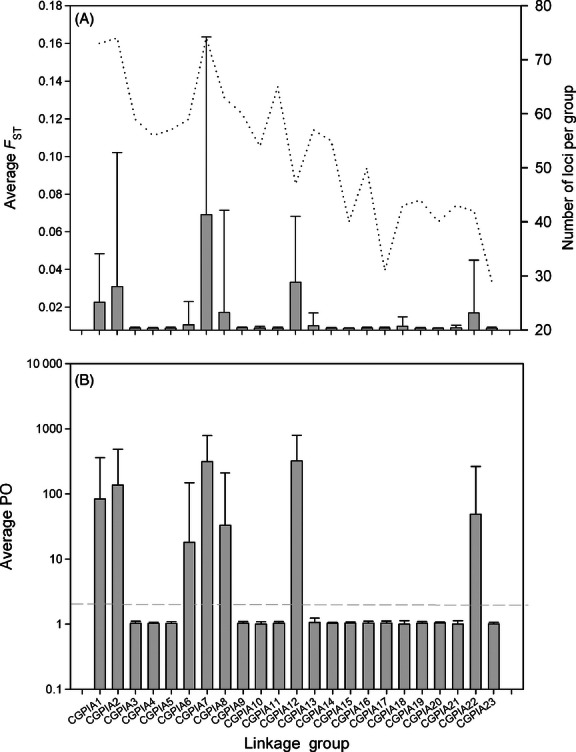

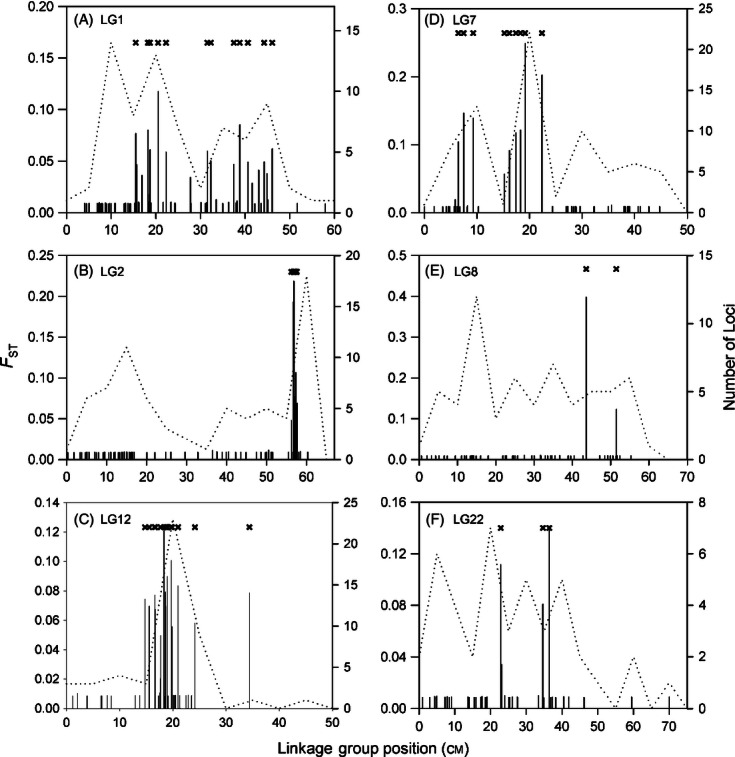

The number of SNPs that mapped to particular linkage groups (LGs) among the 23 identified LGs ranged from fewer than 40 (LG17, LG23; Fig. 3A) to more than 70 (LG1, LG2, and LG7). Average FST per LG among nonisolated western populations varied by more than an order of magnitude (Fig. 3A) to as high as 0.06 (LG7), but the majority (65%) of values were low (<0.01). The proportion of outliers observed per LG differed significantly from random expectations (G-value: 149.40, df = 21, P < 0.001) with eight LGs containing loci identified as putatively experiencing selection (LG1, LG2, LG6, LG7, LG8, LG12, LG13, and LG22). Average posterior odds (BAYESCAN) per LG was above neutral expectations for the seven of the eight LGs that possessed loci identified as potentially experiencing selection (Fig. 3B); only LG13 was not elevated on average. Within each of the identified eight LGs, the numbers of outliers ranged from 1 (LG8 and LG13) to 25 (LG7), and multiple outlier SNPs were distributed along genomic regions ranging from 1.38 cM (LG2) to 30.57 cM (LG1). Interestingly, LG7 displayed an unusually high number of outlier loci, -19-, located at a single map position (19.12 cM; Fig. 4). In addition, peaks in the number of outlier loci at map locations for LGs 1, 2, 7, and 12 corresponded with peaks in the magnitude of differentiation observed, supporting a tendency for outliers to co-occur in genomic regions of high divergence.

Figure 3.

Average divergence (A) and posterior odds ratio (B) by linkage group (LG) (error bars represent standard deviation) for samples from the western Atlantic. Dashed line in (A) represents the number of loci per LG, and in (B) the threshold (posterior odds ratio) for significant tests for selection using BAYESCAN.

Figure 4.

The distribution of genetic differentiation (FST) across each of the linkage groups displaying significant tests for selection for western Atlantic samples. Dashed lines represent the number of loci per genomic region, and crossed line symbols the map positions which tested positive for selection using BAYESCAN. PanI is located in LG1 at 31.5 cM and the hemoglobin β1 in LG2 at 36.5 and 38.8 cM. Note different y-axis scales in each plot.

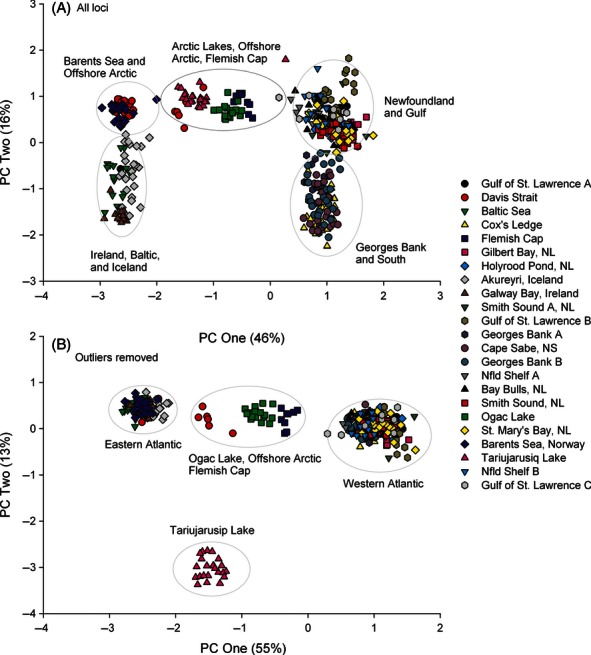

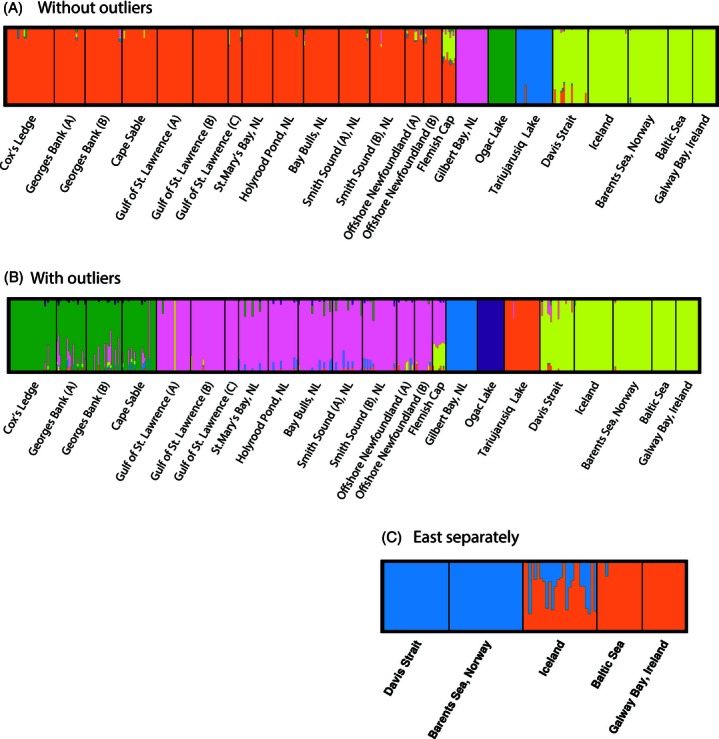

Principle coordinate analysis (PCoA) using all SNPs produced a two-dimensional representation with the first two axes explaining 62% of the variance in the complete dataset (Fig. 5A). Five distinct groupings represent the north and south (PC2) components in the East/North and West Atlantic (PC1), as well as a cluster intermediate on PC1 containing the Arctic lakes, the Flemish Cap, and a portion of the offshore Arctic (Fig. 5A). Removal of outlier SNPs prior to PCoA resulted in the loss of fine-scale geographic separation (principally latitudinal structure) on PC2 (Fig. 5B). Dominant groupings represented the East (including some of the offshore Arctic Davis Strait samples), the West Atlantic south of Labrador, and isolated Arctic and northern locations (Fig. 5B). Euclidean distance calculated from the PCoA associated strongly with geographic distance for the complete dataset (R2 = 0.75, P < 0.001), but the removal of outlier SNPs from the analysis emphasized the influence of the three distinct groups (Figure S1A,B). Bayesian clusters in BAPS were consistent with the PCoA groups. Clustering after removing outliers revealed five clear groups consistent with the isolation of the Arctic lakes, Gilbert Bay, and East and West Atlantic (Fig. 6A). Clustering using the complete dataset revealed six discrete clusters, including five from the western Atlantic (Fig. 6B); however, the single eastern Atlantic group resolved into two groups when we analyzed this group in isolation (Fig. 6C). These clusters represent northern and southern components in the East and West Atlantic and the isolated Arctic Lakes and Gilbert Bay. Again a portion of the Davis Strait/offshore Arctic sample clustered with eastern samples. In both analyses, the Flemish Cap samples associated with other Newfoundland samples, although they also displayed a clear affinity to eastern Atlantic cod populations, which was evident in all individuals (Fig. 6). Assignment success was high with 100% of individuals assigned correctly to population or cluster of origin using either the nonoutlier or the complete SNP panel. The ratio of the likelihood of correct versus incorrect assignment was similar for isolated locations for the nonoutlier loci alone versus the complete panel, but was significantly higher (anova, P-value < 0.0001) for the panel with outlier loci included in the nonisolated populations.

Figure 5.

Principle coordinate analysis of SNPs from rangewide samples of Atlantic cod, using (A) all SNPs and (B) only neutral SNPs.

Figure 6.

Bayesian clustering (BAPS) analysis of SNPs from rangewide samples of Atlantic cod using (A) only neutral SNPs, (B) all SNPs, and (C) all SNPs in the eastern Atlantic only.

Discussion

The successful management of capture fisheries necessitates the representation of adaptive diversity in conservation units (Hilborn et al. 2003; Schindler et al. 2010), the ability to monitor populations for change (Schwartz et al. 2007), and the power to track individuals and products to identify illegal harvest (e.g. Nielsen et al. 2012). The tools to achieve these goals for many groups of commercially exploited marine fishes have thus far remained elusive, limited by apparent widespread genetic homogeneity. However, recent advances in characterizing genomewide adaptive population structuring can resolve unprecedented levels of diversity in marine species (e.g. Limborg et al. 2012) and will likely change how capture fisheries are managed (e.g. Funk et al. 2012). Our observations of several genomic regions of elevated divergence clustered across multiple LGs suggest nonrandom distribution of adaptive variation across the cod genome. Obvious geographic barriers define spatial structuring at neutral loci. The inclusion of outlier SNPs revealed additional barriers to gene flow within both the eastern and western Atlantic. The resolution of genomic signatures of adaptive diversity creates the opportunity for population genomic monitoring, because identified outliers link with ocean climate (Bradbury et al. 2010), and the tracking and assignment of individuals and products to region of origin in this species (e.g. Nielsen et al. 2012). Our results highlight the importance of resolving genomic regions of adaptive divergence for the management and conservation of exploited marine species.

Genome scans can potentially resolve adaptive genetic variation and inform management or conservation strategies in species, which are difficult if not impossible to study through other means (Funk et al. 2012). From a management perspective, the representation of adaptive variation among management units is critical to protecting adaptive diversity essential to a species persistence and stability (Hilborn et al. 2003; Schindler et al. 2010). Our observations of an adaptive cline in Atlantic cod in the region of the Scotian Shelf, which separated populations to the north and south, resulted in a revision of the number of conservation units in this species in Canadian waters (COSEWIC 2010). Similar observations of fine-scale adaptive diversity in other marine fish species such as Atlantic herring (e.g. Limborg et al. 2012) are beginning to accumulate. These observations support the hypothesis that local adaptive diversity in marine fishes may be common (Hauser and Carvalho 2008) and may therefore represent critical considerations in successful management strategies.

The utility of genomic resources for the monitoring of marine populations requires a clear understanding of the function of SNPs or identified genes. Although the functional relationships among these outlier genes remain undetermined, observations are consistent with a previous study identifying temperature associations in a subset of these outliers and populations. Bradbury et al. (2010) identified strong temperature associations on either side of the Atlantic in over half of these outliers (55%), including those clustered in LG7. Our results here, based on more extensive sampling, support spatial trends reported previously and the hypothesis that a large portion of the outliers we identify here link with temperature; however, the genes involved remain to be identified. Associated work identified a QTL for body weight located at map position 19.12 on LG7 (S. Bowman, personal communication). Again this map location is characterized by a large region of low recombination and contains 26% of the identified outliers. Associations among some of these outliers with body size or ocean temperature (Bradbury et al. 2010) suggest an opportunity for their use in the monitoring of population responses to size-selective harvest (e.g. Jakobsdóttir et al. 2011) or climate change; though, these applications require further evaluation. The recent completion of the Atlantic cod genome (Star et al. 2011) should help resolve several of these outstanding issues.

The observed signals of fine-scale geographic differentiation at these gene-associated, high-divergence SNPs also provide the opportunity for accurate assignment of individuals and products to populations or regions of origin. Our study indicates very high success of assignment to cluster, but also that inclusion of outlier loci significantly improved support for assignments. Nielsen et al. (2012) evaluated a similar panel of SNPs for assignment success in Atlantic cod in the eastern Atlantic and concluded that eight of the most divergent loci were required for accurate assignment. In future, similar minimal panels of maximum assignment power could be developed from current studies and tailored to specific regional management issues. Such applications would not have been possible using microsatellite (e.g. Bentzen et al. 1996)- or mtDNA (Carr and Marshall 2008)-based approaches in the western Atlantic because of low levels of spatial differentiation, highlighting the utility of genomewide SNP approaches. Admittedly, the geographic scale of structuring observed at our outlier SNPs in the western Atlantic is often larger than several current stock management units (COSEWIC 2010), and further demographic structuring likely exists within our clusters.

Overall, we identified 5.2% of our surveyed SNPs as outliers, a pattern consistent with past studies that indicated 5–10% of a genome may display signatures of selection (Nosil et al. 2009; Strasburg et al. 2012); though, individual studies reported values ranging from 0.5% (Miller et al. 2007) to approximately 25% (Vasemägi et al. 2005). Part of this variation can likely be explained by the marker type used, given that expressed sequence-based loci or candidate genes can display a higher propensity to test positive for selection (e.g. Vasemägi et al. 2005; Nielsen et al. 2009a). As such, our use of EST-associated SNPs might partly explain the relatively high number of outliers we detected. Despite our success in identifying regions associated with divergence, we likely missed genomic regions experiencing weak selection. The frequency and nature of outlier SNPs observed here might well be influenced by the fact that we obtained these SNPs from a region in the western Atlantic that fortuitously has both previously identified cod temperature haplotypes (Bradbury et al. 2010), but is otherwise limited in its representation of cod habitat and diversity. Had we developed the SNPs using a rangewide ascertainment panel, and we might well have discovered many SNPs associated with other types of selective forces. In addition, direct experimental tests of selection and finer-scale sequencing commonly identify widespread genomic divergence resulting from selection and speciation, often contrasting earlier works that identify only a few such regions (e.g. Michel et al. 2010; Hahn et al. 2012). Further examination will likely build on the regions of divergence identified here.

The roles ascertainment bias or temporal variation among samples may play in the observed spatial patterns, or potential assignment success remains unclear. Ascertainment bias is evident in the present dataset as a decline in diversity from west to east associated with distance from the location of the ascertainment panel (Bradbury et al. 2011). We evaluated the impact of ascertainment bias on the accuracy of individual assignment, and although significant declines in assignment power were visible with some subsets of SNPs, overall there are no reductions in power for the complete panel (Bradbury et al. 2011). Sampling in the eastern Atlantic was limited, however, and in conjunction with lower observed diversity of the SNPs in the east, suggests that we may have missed significant population structure. In addition, because the samples used in our study span a 14-year period, temporal variation in allele frequency may contribute to the patterns observed. However, recent work based on a subset of these SNPs observed temporal stability over 10-year period (Nielsen et al. 2012) in European samples. Although the contribution of temporal variation to the observed spatial trends cannot be discounted, given the length of the period (2–3 generations), and evidence of stability elsewhere, we infer minimal bias in relation to the spatial trends observed.

Clustering of divergent loci within genomic regions may be common (McGaugh and Noor 2012; Via 2012) and particularly prevalent in the regions of low recombination (Nosil and Feder 2012). Across the Atlantic cod genome, the distribution of genetic divergence was not random but clustered in several LGs and map locations within LGs. This clustering was most apparent in LG7 where multiple outlier SNPs clustered to a single map location. Undoubtedly, some of this clustering could be associated with genetic hitchhiking (Maynard-Smith and Haigh 1974). Similar outlier clustering was reported in the house mouse (Mus musculus) where divergent regions accounted for 7–8% of the genome and associated with eight genomic regions (Harr 2006). Among forms of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, divergence was associated with 1.2% of the genome and distributed among three genomic regions (Turner et al. 2005). Our observation of clustering among outliers is consistent with the hypothesis that mutations contributing to divergence should accumulate in the regions of genome already experiencing divergent selection (Navarro and Barton 2003; Kirkpatrick and Barton 2006; Nosil et al. 2009) or experiencing low recombination rates (McGaugh and Noor 2012; Nachman and Payseur 2012). Significant linkage disequilibrium among outliers may inflate spatial trends if compared SNPs are not independent. Although we cannot fully discount inflated trends here, we believe it unlikely given that several outliers mapped to different LGs or locations within a LG. Nonetheless, until a physical map is available or the SNPs successfully annotated we cannot rule out potential for bias.

Our spatial analysis revealed several patterns that extend beyond that of increased spatial isolation with outlier loci. First, several locations in the Arctic and the Flemish Cap sample appear genetically intermediate between the eastern and western Atlantic on the first axis of the principle coordinate analysis. Moreover, some of the offshore Arctic Davis Strait samples cluster with the eastern Atlantic. Both observations contradict a hypothesis of long standing vicariance and support a hypothesis of eastern Atlantic colonization in the Arctic or historic trans-Atlantic gene flow. However, formally testing this hypothesis remains challenging in light of the potential confounding influence of ascertainment bias. Nonetheless, individuals from the Flemish Cap display eastern Atlantic affinities in the BAPS analysis mirroring observations based on whole mtDNA genome analysis of Flemish Cap cod which share ancestral clades with Barents Sea cod (S.M. Carr and H.D. Marshall, personal communication). Previous studies report similar trans-Atlantic trends in genetic structure and the presence of eastern Atlantic genotypes in the northwest Atlantic for both marine and anadromous fishes. In Atlantic wolffish (Anarhichas lupus), which is widely distributed across the Atlantic, a dominant genetic break separates populations to the southwest and east of western Greenland with some eastern affiliations of populations along the northern Grand Banks off Newfoundland (McCusker and Bentzen 2010). Similarly in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), longstanding genetic isolation occurs in the south on either sides of the Atlantic, but again Newfoundland and Labrador consistently contain populations characterized by eastern Atlantic genotypes (King et al. 2007). Together, these observations support a hypothesis of past trans-Atlantic gene flow perhaps associated with warm interglacial periods allowing the colonization of Canadian Arctic marine and lake habitats from the eastern Atlantic. In conjunction with the observations of fine-scale adaptive divergence, our observations of potential trans-Atlantic gene flow provide novel insight into the past and future spatial dynamics of cod in the North Atlantic.

Summary

Genomic regions associated with adaptation may directly inform conservation efforts in exploited marine species, by delineating management units, and providing genomic tools for population monitoring and individual assignment. We observed significant variation in the genomic and geographic scale of differentiation in Atlantic cod, using a panel of EST-associated SNPs. Genomic islands of divergence were associated with several LGs and in several instances clustered significantly, supporting the hypothesis that divergent regions co-occur in response to strong selection or low recombination. Outlier SNPs, likely associated with adaptive divergence, resolved fine-scale structure not evident at neutral loci and provide ample power for successful individual assignment to the region of origin. Geographic population differentiation in Atlantic cod appears to be distinguished by a few discrete islands of genomic divergence, although finer-scale sequence analysis and selection experiments are needed to further resolve the genomic scale of divergence. This work demonstrates the utility of genomic regions of adaptive divergence in the delineation of stock structure, traceability of individuals and products, and ultimately a role for population genomics in the conservation of marine fisheries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all who assisted tissue collection. L. Barrett and M. Foll assisted and advised on data analysis and interpretation. Research was supported in part by Genome Canada, Genome Atlantic and the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency through the Atlantic Cod Genomics and Broodstock Development Project. A complete list of supporting partners can be found at http://genomeatlantic.ca/projects/view/8-The_Atlantic_Cod_Genomics_and_Broodstock_Development_Project_CGP.php. Research funding and support was also provided by a NSERC Strategic Grant on Connectivity in Marine Fish and an NSERC Discovery Grant.

Data archiving statement

Details on SNP development and genotyping are available in the studies by Bowman et al. (2010) and Hubert et al. (2010). The SNPs analyzed in this study are available in GenBank dbSNP (accession numbers: ss131570222–ss131571915). Additional methods and results can be found as Supporting Information.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Euclidean distance among population average PCoA values of SNPs from range-wide samples of Atlantic cod using (A) all SNPs and (B) only neutral SNPs.

Table S1. Details on sample locations and SNP summary statistics.

Table S2. Pairwise FST values for all samples and all SNPs.

Table S3. Pairwise FST values for all samples and all non-outlier SNPs.

Table S4. Results of BAYESCAN analysis with all samples included.

Data S1. Methods.

LGMAP1.

LGMAP2.

Linkage maps 1 and 2.

Literature cited

- Andersen O, Wetten OF, De Rosa MC, Andre C, Carelli Alinovi C, Colafranceschi M, Brix O, et al. Haemoglobin polymorphisms affect the oxygen-binding properties in Atlantic cod populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:833–841. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EC. Assessing the power of informative subsets of loci for population assignment: standard methods are upwardly biased. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2010;10:701–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen P, Taggart CT, Ruzzante DE, Cook D. Microsatellite polymorphism and the population structure of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in the Northwest Atlantic. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1996;53:2706–2721. [Google Scholar]

- Bierne N, Welch J, Loire E, Bonhomme F, David P. The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Molecular Ecology. 2011;20:2044–2072. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza T, Higgins B, Simpson G, Bowman S. Integrating the markers Pan I and haemoglobin with the genetic linkage map of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua. BMC Research Notes. 2010;3:261. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman S, Hubert S, Higgins B, Stone C, Kimball J, Borza T, Tarrant Bussey J, et al. An integrated approach to gene discovery and marker development in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua. Marine Biotechnology. 2010;13:242–255. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9285-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury IR, Hubert S, Higgins B, Bowman S, Paterson I, Snelgrove PVR, Morris C, et al. Parallel adaptive evolution of Atlantic cod in the eastern and western Atlantic Ocean in response to ocean temperature. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:3725–3734. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury IR, Hubert S, Higgins B, Bowman S, Paterson IG, Snelgrove PVR, Morris CJ, et al. Evaluating SNP ascertainment bias and its impact on population assignment in Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2011;11:218–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr SM, Marshall HD. Intraspecific phylogeographic genomics from multiple complete mtDNA genomes in Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua): origins of the “Codmother,” trans-Atlantic vicariance, and mid-glacial population expansion. Genetics. 2008;108:381–389. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case RAJ, Hutchinson WF, Hauser L, Van Oosterhout C, Carvalho GR. Macro- and micro-geographic variation in pantophysin (Pan I) allele frequencies in NE Atlantic cod Gadus morhua. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2005;301:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Corander J, Marttinen P. Bayesian identification of admixture events using multi-locus molecular markers. Molecular Ecology. 2006;15:2833–2843. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSEWIC. COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the North Atlantic Cod, Gadus moruha, in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Deagle BE, Jones FC, Chan YF, Absher DM, Kingsley DM, Reimchen TE. Population genomics of parallel phenotypic evolution in stickleback across stream–lake ecological transitions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2011;279:1277–1286. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphinstone MS, Hinten GN, Anderson MJ, Nock CJ. An inexpensive and high-throughput procedure to extract and purify total genomic DNA for population studies. Molecular Ecology. 2003;3:317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Lischer HE. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2010;10:546–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Hofer T, Foll M. Detecting loci under selection in a hierarchically structured population. Heredity. 2009;103:285–298. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder JL, Nosil P. The efficacy of divergence hitchhiking in generating genomic islands during ecological speciation. Evolution. 2010;64:1729–1747. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foll M, Gaggiotti O. A Genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. Genetics. 2008;180:977–993. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.092221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier-Level A, Korte A, Cooper MD, Nordborg M, Schmitt J, Wilczek AM. A map of local adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2011;334:86–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1209271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DJ, Bernatchez L. Adaptive evolutionary conservation: towards a unified concept for defining conservation units. Molecular Ecology. 2001;10:2741–2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk WC, McKay JK, Hohenlohe PA, Allendorf FW. Harnessing genomics for delineating conservation units. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2012;27(9):489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MW, White BJ, Muir CD, Besansky NJ. No evidence for biased co-transmission of speciation islands in Anopheles gambiae. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:374–384. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock AM, Brachi B, Faure N, Horton MW, Jarymowycz LB, Sperone FG, Toomajian C, et al. Adaptation to climate across the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Science. 2011;334:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1209244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harr B. Genomic islands of differentiation between house mouse subspecies. Genome Research. 2006;16:730–737. doi: 10.1101/gr.5045006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser L, Carvalho GR. Paradigm shifts in marine fisheries genetics: ugly hypotheses slain by beautiful facts. Fish and Fisheries. 2008;9:333–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hilborn R, Quinn TP, Schindler DE, Rogers DE. Biocomplexity and fisheries sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:6564–6568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037274100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert S, Tarrant Bussey J, Higgins B, Curtis BA, Bowman S. Development of single nucleotide polymorphism markers for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) using expressed sequences. Aquaculture. 2009;296:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert S, Higgins B, Borza T, Bowman S. Development of a SNP resource and a genetic linkage map for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsdóttir KB, Pardoe H, Magnússon Á, Björnsson H, Pampoulie C, Ruzzante DE, Marteinsdóttir G. Historical changes in genotypic frequencies at the Pantophysin locus in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in Icelandic waters: evidence of fisheries-induced selection? Evolutionary Applications. 2011;4:562–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King TL, Verspoor E, Spidle AP, Gross R, Phillips RB, Koljonen ML, Sanchez JA, et al. The Atlantic Salmon. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. Biodiversity and population structure. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M, Barton NH. Chromosome inversions, local adaptation and speciation. Genetics. 2006;173:419–434. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limborg MT, Helyar SJ, De Bruyn M, Taylor MI, Nielsen EE, Ogden R, Carvalho GR, et al. Environmental selection on transcriptome-derived SNPs in a high gene flow marine fish, the Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus. Molecular Ecology. 2012;21:3686–3703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard-Smith J, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favorable gene. Genetical Research. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker MR, Bentzen P. Phylogeography of 3 North Atlantic wolffish species (Anarhichas spp.) with phylogenetic relationships within the family Anarhichadidae. Journal of Heredity. 2010;101:594–601. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esq062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh SE, Noor MAF. Genomic impacts of chromosomal inversions in parapatric Drosophila species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:422–429. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel AP, Sim S, Powell THQ, Taylor MS, Nosil P, Feder JL. Widespread genomic divergence during sympatric speciation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:9724–9729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000939107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NJ, Ciosi M, Sappington TW, Ratcliffe ST, Spencer JL, Guillemaud T. Genome scan of Diabrotica virgifera virgifera for genetic variation associated with crop rotation tolerance. Journal of Applied Entomology. 2007;131:378–385. [Google Scholar]

- Nachman MW, Payseur BA. Recombination rate variation and speciation: theoretical predictions and empirical results from rabbits and mice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:409–421. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narum R, Hess JE. Comparison of FST outlier tests for SNP loci under selection. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2011;11:184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Barton NH. Chromosomal speciation and molecular divergence-accelerated evolution in rearranged chromosomes. Science. 2003;300:321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1080600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen EE, Hemmer-Hansen J, Larsen PF, Bekkevold D. Population genomics of marine fishes: identifying adaptive variation in space and time. Molecular Ecology. 2009a;18:3128–3150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen EE, Hemmer-Hansen J, Poulsen N, Loeschcke V, Moen T, Johansen T, Mittelholzer C, et al. Genomic signatures of local directional selection in a high gene flow marine organism; the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009b;9:276. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen EE, Cariani A, Aoidh E, Maes GE, Milano I, Ogden R, Taylor M, et al. Gene-associated markers provide tools for tackling illegal fishing and false eco-certification. Nature Communications. 2012;3:851. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosil P, Feder JL. Genomic divergence during speciation: causes and consequences. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:332–342. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosil P, Funk DJ, Ortiz-Barrientos D. Divergent selection and heterogeneous genomic divergence. Molecular Ecology. 2009;18:375–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paetkau D, Slade R, Burden M, Estoup A. Genetic assignment methods for the direct, real-time estimation of migration rate: a simulation-based exploration of accuracy and power. Molecular Ecology. 2004;13:55–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2004.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R, Smouse PE. Genalex 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2006;6:288–295. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piry S, Alapetite A, Cornuet JM, Paetkau D, Baudouin L, Estoup A. GeneClass2: a software for genetic assignment and first-generation migrant detection. Journal of Heredity. 2004;95:536–539. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannala B, Mountain JL. Detecting immigration by using multilocus genotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94:9197–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SM, Bernatchez L. The genetic architecture of ecological speciation and the association with signatures of selection in natural lake whitefish (Coregonas sp. Salmonidae) species pairs. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24:1423–1438. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler DE, Hilborn R, Chasco B, Boatright CP, Quinn TP, Rogers LA, Webster MS. Population diversity and the portfolio effect in an exploited species. Nature. 2010;465:609–612. doi: 10.1038/nature09060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MK, Luikart G, Waples RS. Genetic monitoring as a promising tool for conservation and management. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. (Personal edition) 2007;22:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Star B, Nederbragt AJ, Jentoft S, Grimholt U, Malmstrom M, Gregers TF, Rounge TB, et al. The genome sequence of Atlantic cod reveals a unique immune system. Nature. 2011;477:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nature10342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburg JL, Sherman NA, Wright KM, Moyle LC, Willis JH, Rieseberg LH. What can patterns of differentiation across plant genomes tell us about adaptation and speciation? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:364–373. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart CT, Cook D. Manuscript Report, Marine Gene Probe Laboratory. Halifax, NS: Dalhousie University; 1996. Microsatellite genetic analysis of Baltic cod: a preliminary report. [Google Scholar]

- Turner TL, Hahn MW, Nuzhdin SV. Genomic islands of speciation in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Biology. 2005;3:e285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen JW. JoinMap 4. Software for the Calculation of Genetic Linkage Maps in Experimental Populations. Wageningen, Netherlands: Kyazma BV; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vasemägi A, Nilsson J, Primmer CR. Expressed sequence tag (EST) linked microsatellites as a source of gene associated polymorphisms for detecting signatures of divergent selection in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;22:1067–1076. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Via S. Divergence hitchhiking and the spread of genomic isolation during ecological speciation-with-gene-flow. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:451–460. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Via S, West J. The genetic mosaic suggests a new role for hitchhiking in ecological speciation. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:4334–4345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waples RS. Evolutionarily significant units and the conservation of biological diversity under the Endangered Species Act. American Fisheries Society Symposium. 1995;17:8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. The genic view of the process of speciation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2001;14:851–865. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Euclidean distance among population average PCoA values of SNPs from range-wide samples of Atlantic cod using (A) all SNPs and (B) only neutral SNPs.

Table S1. Details on sample locations and SNP summary statistics.

Table S2. Pairwise FST values for all samples and all SNPs.

Table S3. Pairwise FST values for all samples and all non-outlier SNPs.

Table S4. Results of BAYESCAN analysis with all samples included.

Data S1. Methods.

LGMAP1.

LGMAP2.

Linkage maps 1 and 2.