Abstract

BACKGROUND:

While paper headache pain diaries have been used to determine the effectiveness of headache treatments in clinical trials, recent advances in information and communication technologies have resulted in the burgeoning use of electronic diaries (e-diaries) for headache pain.

OBJECTIVE:

To qualitatively review headache e-diaries, assess their measurement properties, examine measurement components and compare these components with recommended reporting guidelines.

METHODS:

The databases Medline, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, PsychInfo, the Education Resources Information Centre and ISI Web of Science were searched for self-report headache e-diaries for children and adults. A total of 21 publications that involved e-diaries were found; five articles reported on the development of an e-diary and 16 used an e-diary as an outcome measure in randomized controlled trials or observational studies. The diary measures’ components, features and psychometric properties, as well as the quality of evidence of their psychometric properties, were evaluated.

RESULTS:

Five headache e-diaries met the a priori criteria and were included in the final analysis. None of these e-diaries had well-developed evidence of reliability and validity. Three e-diaries showed evidence of feasibility. E-diaries with ad hoc measures developed by the study investigators were most common, with little to no supportive evidence of reliability and/or validity. Compliance with the reporting guidelines was variable, with only one-half of the e-diaries measuring the recommended primary outcome of headache frequency.

CONCLUSIONS:

Specific recommendations regarding the development (including essential components) and testing of headache e-diaries are discussed. Further research is needed to strengthen the measurement of headache pain in clinical trials using headache e-diaries.

Keywords: Adults, Children, Electronic pain diaries, Headache diary, Psychometric properties

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Des journaux papier des douleurs céphaliques sont utilisés pour déterminer l’efficacité des traitements des céphalées lors d’essais cliniques, mais les progrès récents des technologies de l’information et des communications ont suscité l’essor des journaux virtuels de céphalées.

OBJECTIF :

Faire l’analyse qualitative des journaux virtuels de céphalées, en évaluer les propriétés de mesure, examiner les éléments de mesure qu’ils contiennent et les comparer avec les lignes directrices de déclaration recommandées.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont fouillé les bases de données Medline, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, PsychInfo, Education Resources Information Centre et ISI Web of Science pour en extraire les journaux virtuels de céphalées autodéclarées pour les enfants ou les adultes. Au total, ils ont trouvé 21 publications faisant appel à des journaux virtuels. Cinq traitaient de l’élaboration d’un journal virtuel et 16 utilisaient le journal virtuel comme mesure d’issue dans des essais aléatoires et contrôlés ou des études d’observation. Ils ont évalué les éléments de mesure, les caractéristiques et les propriétés psychométriques des journaux, de même que la qualité des preuves de leurs propriétés psychométriques.

RÉSULTATS :

Cinq journaux virtuels de céphalées respectaient les critères de départ et ont été inclus dans l’analyse définitive. Aucun ne con-tenait de données probantes bien établies sur leur fiabilité et leur validité. Trois journaux virtuels ont démontré des manifestations de faisabilité. Les journaux virtuels comportant des mesures ponctuelles élaborées par les chercheurs étaient les plus courantes. Très peu de données, sinon aucune, en étayaient la fiabilité ou la validité. Le respect des lignes directrices déclarées était variable, puisque seulement la moitié des journaux virtuels mesuraient l’issue primaire recommandée de fréquence des céphalées.

CONCLUSIONS :

Des recommandations relatives à l’élaboration (y compris les éléments essentiels) et à la mise à l’essai des journaux virtuels de céphalées sont exposées. D’autres recherches s’imposent pour renforcer la mesure de la douleur céphalique dans le cadre d’essais cliniques qui font appel à des journaux de céphalées.

Primary headache disorders (eg, migraine, tension-type headaches) are frequent in the general population. Headache prevalence varies considerably through the lifespan, typically increasing in childhood and youth, and remaining relatively stable and high over the third to fifth decades of life before markedly declining in both sexes. Headaches can negatively impact all aspects of quality of life (psychological [1–3], work/school [4–8] and social functioning [9,10]), resulting in costly disability. Paper pain diaries have been used for several decades in diverse patient populations for many purposes. In the headache patient population, they have primarily been used to assess the impact of headaches and to evaluate the efficacy of headache treatments. However, paper headache diaries exhibit several important limitations, including participant noncompliance and inaccuracies in data entry (11). Noncompliance in participants has been found to be due to the fact that paper diaries are bulky and cannot be used easily or discreetly in the workplace or school. Inaccuracies result from false entries or multiple entries being made at a more convenient time to compensate for noncompliance (11).

When pain diaries (paper or electronic) are used to assess the efficacy of treatments for recurrent and chronic pain conditions, ideally, they should conform to the recent recommendations regarding the core outcome domains suggested for use in clinical trials in children (Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials [Ped-IMMPACT]) and adults (IMMPACT) with recurrent and chronic pain (12,13). The eight core outcomes include pain, physical functioning, emotional functioning, role functioning, symptoms and adverse events, global judgement of satisfaction, sleep and economic factors (12). More specifically, efficacy studies of headache treatments should conform to clinical trial guidelines for both pharmacological (14) and behavioral (15) headache trials, which recommend headache frequency as the primary outcome measure. Recommended secondary outcomes include other headache characteristics (headache index, duration, severity), functional status, headache-related disability and quality of life (see Table 1 for a summary of these guidelines). Furthermore, there should be evidence that these diaries are reliable and valid, so that valid conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment strategies.

TABLE 1.

Guidelines for headache and chronic pain clinical trials

| Guidelines | Primary outcomes Headache | Recommended measures (when provided) | Secondary outcomes | Recommended measures (when provided) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guidelines for pharmacological headache trials (14) | Percentage of patients pain-free at 2 h Sustained pain-free Frequency |

Number of patients pain-free at 2 h with no use of rescue medication or relapse within 48 h Number of attacks per four-week period |

Headache intensity Headache relief Time to meaningful relief Global evaluation of medication Functional disability Presence of photo/phonophobia Patients’ preference for treatment Consistency of effect |

Verbal/numerical rating scale (0 = no headache; 1 = mild headache; 2 = moderate headache; 3 = severe headache). Percentage of patients with a decrease in headache from severe or moderate to none or mild within 2 h Simple verbal scale Categorical verbal/numerical scale (0 = no disability; 1 = performance of daily activities mildly impaired; 2 = performance of daily activities moderately impaired; 3 = performance of daily activities severely impaired) At least three-quarters of attacks consecutively treated with active drug |

|

| Migraine | |||||

|

| |||||

| Frequency | Number of attacks per four-week period | Headache intensity Headache duration Drug consumption for symptomatic treatment Patient preferences |

Same as headache Number of migraine attacks per four-week period treated with symptomatic treatment/number of tablets per four-week period |

||

| Episodic | |||||

|

| |||||

| Guidelines for behavioural headache trials (15) | Frequency | Number of attacks per month | Headache index Headache duration Peak headache severity Functional status Quality of life Medication use Patient preferences Psychological symptoms |

Missed work/school Headache-specific quality of life |

|

| Chronic | |||||

|

| |||||

| Frequency | Headache days per month | Headache index Number of severe headache days per month Headache duration Peak headache severity Functional status Quality of life Patient preferences Psychological symptoms |

Same as episodic | ||

|

| |||||

| Guidelines for chronic pain clinical trials (12,13) | Pain intensity Physical functioning Emotional functioning Role functioning Symptoms and adverse events Global judgement of satisfaction with treatment Sleep Economic factors |

11-point (0–10) numerical rating scale of pain intensity Multidimensional Pain Inventory Interference Scale OR Brief Pain Inventory interference items Beck Depression Inventory OR Profile of Mood States School attendance, PedMIDAS, PedsQL* Passive capture of spontaneously reported adverse events and symptoms and use of open-ended prompts Sleep diary, Sleep Habits Questionnaire* |

|||

*Pediatric recommendations. PedMIDAS Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment; PedsQL Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

During the past decade, there has been a growing trend toward measuring recurrent and chronic pain using real-time data capture (RTDC) approaches that use electronic pain diaries (e-diaries) (11,16). E-diaries have the advantages of maximizing participant compliance in completing pain ratings as well as the validity of those ratings because e-diaries can be accessed from any computer or handheld device (17). Although headache e-diaries are becoming more common, little is known about their components and features, psychometric properties and feasibility (compliance and acceptability). Therefore, the primary objective of the present study was to qualitatively review the research literature to evaluate the psychometric properties of headache e-diaries for children and adults. A secondary aim was to explore the components and features of the headache diaries and compare these components with the core outcomes recommended for headache and chronic pain clinical trials. The present review will serve to identify future avenues of research to enhance the measurement properties of headache e-diaries and will help future researchers to decide which variables to assess and how to assess them within the context of differing study purposes.

METHODS

All published peer-reviewed English-language research studies examining the psychometric properties and feasibility of self-reported headache pain e-diaries as a main outcome measure in children and adults were considered for inclusion in the present review. Unpublished manuscripts, reviews, guidelines, commentaries and other descriptive articles were excluded. Published abstracts were not included because the information provided in abstracts is limited and frequently not peer reviewed. Outcome measures other than headache e-diaries, such as surveys, questionnaires and clinical interviews, were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English were also excluded due to time and financial constraints (translation costs) and no attempt was made to locate unpublished material or to contact authors of unpublished studies.

Search strategy for identification of studies

Included studies were accessed primarily through a search of Medline (1947 to September 9, 2009), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1981 to September 9, 2009), Embase (1947 to September 9, 2009), PsychINFO (1947 to September 9, 2009), the Education Resources Information Centre (1966 to September 9, 2009) and ISI Web of Knowledge (1950 to September 9, 2009) databases. The search terms included MeSH headings, subjects, text words, wild cards and/or keywords relevant to the following terms: “headache”, “migraine”, “cephalagia”, “electronic diary or diary”, “pen-and-paper diary or diaries”, “personal digital assistant”, “decision-making support”, “ecological momentary assessment” and “real time data capture” were used. Reference lists from all identified appropriate research and review articles were examined. Non-English language abstracts were excluded due to the cost of translation. The exclusion of non-English language research studies was minimal (552 of the total of 7102). Two librarians (at two different institutions) independently conducted the literature searches.

Methods of the review

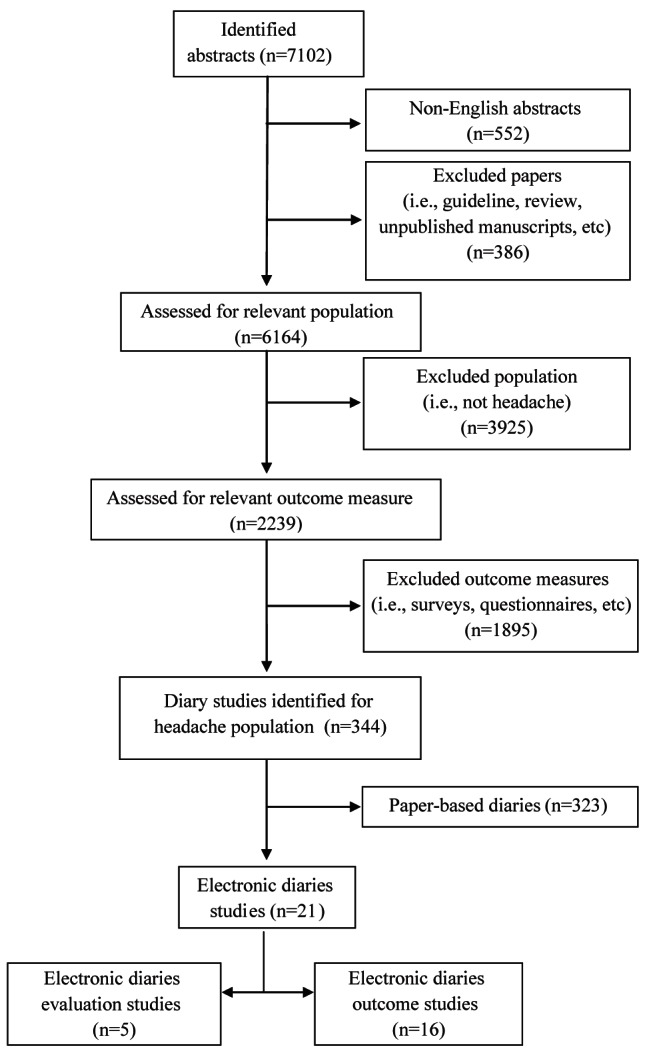

Two reviewers (BR, CS) screened all identified titles and abstracts for relevance and assessed potentially relevant studies for inclusion independently (n=7102). Abstracts were included in the review if they assessed headache and used an e-diary as a primary outcome measure. Non-English language abstracts, guidelines, reviews and unpublished manuscripts were immediately excluded from the review (Figure 1). Level of agreement between the two reviewers (BR, CS) was 98%, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (GC). A systematic approach to data extraction was used to produce a descriptive summary of the psychometric findings and feasibility of the headache e-diaries. The two reviewers first developed and tested an extraction database. For all abstracts meeting the inclusion criteria (n=344), the full article was found and subsequently entered into the database by the two reviewers; level of agreement was 100%. Outcome data extraction focused on the measures of age range, type of headache pain and the diary’s psychometric properties, including reliability, validity, responsivity, interpretability and feasibility (compliance, acceptability and technical problems). Table 2 includes operational definitions of these measurement terms (18–24). Data were also collected on the components assessed in the diary, features of the diary (eg, alarms) and type of e-diaries used (eg, handheld device, desktop computer, etc).

Figure 1).

Study selection

TABLE 2.

Operational definition of terms

| Term | Operational definition |

|---|---|

| Reliability | The reproducibility of a measure over different occasions. Is concerned with minimizing sources of random error so that measures are reproducible (18). In general, acceptable reliability coefficients for research and clinical purposes are ≥0.7 and ≥0.9, respectively (18,19) |

| Inter-rater (interobserver) reliability | The agreement between different raters/observers of an observational measure of pain (18) |

| Test-retest reliability | The agreement between observations within the same individuals on at least two occasions (18) |

| Internal consistency | A type of reliability that includes the mean of the correlation of scores from a measure with the scores of all the items in the measure (18) |

| Validity | Used to assess whether the scale is measuring what it is intending to measure (18) |

| Face validity | Whether the pain scale includes appropriate items that appear to measure what it is proposing to measure (18) |

| Content validity | The assessment of whether the items in the pain measure include the appropriate information and content (18) |

| Criterion | Includes concurrent validity and predictive validity. In general, correlations between the new measure and the gold standard should be at least r≥0.3–0.5. The magnitude of the coefficients are hypothesis dependent but should not be so high as to make the new measure redundant. In predictive validity, the correlation of the measure to the criterion variable is determined at a later time (18) |

| Construct | Determines the validity of abstract variables, such as pain, that cannot be directly observed. These constructs are assessed by their relationships with other variables (18,20) |

| i. Convergent validity | Evaluates how well items on a pain scale correlate with other measures of the same construct or related variables. In general, correlations between the measure and another measure of the same construct should be r≥0.3–0.5; however, the magnitude of the coefficients are hypothesis dependent (18) |

| ii. Discriminant validity | Evaluates how items in a pain scale correlate with other measures that are unrelated. In general, correlations between the measure and another unrelated measure should be r≥0.3; however, the magnitude of the coefficients are hypothesis dependent (18). |

| Responsivity | Measures whether the measure is able to identify changes in pain over time that is clinically important to patients. An acceptable effect size should be r≥0.05; however, the effect size is hypothesis dependent (21,22) |

| Interpretability | The meaningfulness of the scores obtained from the measure (20) |

| Feasibility | How easily the measure can be scored and interpreted (23) |

| Compliance | The number of observed over the expected number of diary entries completed for the study period |

| Acceptability | What the end-users liked and disliked about the electronic headache diary |

Adapted from Stinson et al (24)

Finally, the overall level of psychometric evidence supporting each e-diary was explored using two complementary methods. Initially, two raters (BR, CS) applied the Cohen criteria (25) to evaluate the e-diaries based on the psychometric criteria outlined above, which are described as essential in the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (26). According to these established criteria, measures can be classified as ‘well-established’, ‘approaching well-established’ or ‘promising’ (Appendix I [25]). Additionally, the two raters (BR, CS) also used the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) checklist (27), a four-step tool, to evaluate the methodological quality of the studies designed to assess the psychometric properties of these e-diaries. Specifically, the COSMIN checklist explores whether the following properties have been assessed in the study: internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, construct validity, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity, responsiveness, interpretability and generalizability (27). The level of agreement between the raters was 100% when applying both the Cohen criteria and the COSMIN checklist.

RESULTS

A total of 7102 abstracts were identified from the electronic searches, of which 386 abstracts were removed due to manuscript type (guidelines, reviews, unpublished manuscripts). After accounting for non-English language publications, 552 abstracts were also removed (of the non-English language publications, 27 contained diary information; however, it was unclear from the abstracts whether they were referring to electronic or paper diaries), leaving 6164 abstracts for further consideration. Of these, 3925 abstracts were removed based on their study population (not headache) and 1895 were excluded because they were not diary studies, leaving 344 abstracts for inclusion. Included articles were further analyzed to yield 323 studies involving paper diaries and 21 e-diary studies. A list of the excluded articles is available from the primary author on request.

On initial review, it was observed that there were two distinct groups of articles: those using an e-diary to capture outcome data (n=16), which will be referred to as ‘outcome studies using e-diaries’ (studies 6 through 21) (28–43), and those reporting on the development and/or psychometric testing (n=5) of headache e-diaries, which will be referred to as ‘evaluation studies of e-diaries’ (studies 1 through 5) (44–48). The study characteristics of these five evaluation studies of e-diaries are summarized in Table 3. Each of these studies will be referred to as Studies 1 through 5 in the results. However, due to the limited information on the headache e-diaries reported in the outcomes studies, only brief summaries of the characteristics of these diaries were possible (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Study characteristics

| Study number | Author (reference), year (country) | Target population; sample size; mean age, years (range or SD) | Study design and goal | Type of electronic device; characteristics of diary | Variables (outcome measures used in diary capture) | Sampling protocol; number of diary entries per day; length of diary use | General features of assessment tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Goldberg et al (44), 2007 (USA) | Adult females; n=20; 37 years of age (range 21–47) | Prospective observational To evaluate an electronic diary as a diagnostic tool to study headache and premenstrual symptoms |

Nino handheld device (Provenda Biometrics, USA); Set number of direct questions uses branching logic to trigger subsequent questions |

Presence or absence of headache symptoms Pain severity (0–10 NRS) Pain localization (ad hoc*) Pain quality (ad hoc*) Associated symptoms (ad hoc*) Functioning interference (ad hoc*) Premenstrual symptoms (ad hoc*) |

Event-based; mean 1.75 per day; three months |

Acceptability: Technical issues resulted in low satisfaction with e-diary – this was assessed from the perspective of researchers Technical problems: 35% of the total number of entries for the study had abnormal session endings; 34.5% of diary entries did not record an answer to the first question |

| 2 | Lewandowski et al (45), 2009 (USA) | Children with either recurrent headache (n=54), juvenile chronic arthritis (n=30), SCD (n=9); 12.5±2.5 years of age | RCT To compare diary and retrospective reports of pain |

Handheld PDA (Jornada 548, Hewlitt Packard, USA); Specific sequence of questions with a built-in response loop |

Pain intensity (Faces Pain Scale [39]) Activity limitations (Children’s Activity Limitations Interview [40]) |

Time-based; once per day; one week | Compliance: 98% compliance (e-diary users completed a mean of 6.89 days of diary reports over a seven-day period versus 4.97 days for paper diary users) |

| 3 | Moloney et al (46), 2009 (USA) | Women, 18–55 years of age; n=94; 37.5 years of age (range 21–54) | Prospective observational To explore feasibility and acceptability of Internet-based headache diary |

Personal desktop computer; Paper and pencil headache diary transformed for Internet using javascript and ColdFusion (Adobe Systems Inc, USA) |

Triggers Prodromal symptoms and their severity Use of self-treatment Probability of occurrence of a headache (ad-hoc*; Likert-type scales, multiple-choice and open-ended questions) |

Time-based; four months; one per day |

Compliance: 75% of all diary pages were completed within two days Acceptability: Participants reported that the dairy website was user-friendly and easy to navigate, with straightforward instructions Technical problems: 21% reported occasional difficulties with computer or website access; entries posted in a later time zone than that of the study were logged as late entries and error messages were sent |

| 4 | Palermo et al (47), 2004 (USA) | Children, 8–16 years of age, with headache (n=40) or juvenile idiopathic arthritis (n=20); 12.3±2.4 years of age | RCT To compare compliance, accuracy and acceptability of electronic versus paper diaries |

Handheld PDA (Jornada 548, 32 MB RAM, colour screen [Hewlitt Packard, USA]) using the Windows CE operating system (Microsoft Corporation, USA); Specific sequence of questions with a built-in response loop |

Daily pain occurrence (ad hoc*) Pain localization (validated body outline [41]) Pain intensity (Faces Pain Scale [39]) Pain duration (ad hoc*) Emotional upset (ad hoc*) Activity limitations (Children’s Activity Limitations Interview [40]) Somatic symptoms (Children’s Somatization Inventory, six core items) (42) |

Time-based; once per day; one week |

Compliance: Compliance was significantly higher for e-diary users, with 83.3% of children completing all e-diary entries versus 46.7% of paper diary users Acceptability: 83.3% of e-diary users found the diary ‘very easy or easy to remember to fill out’; 72.2% found the e-diary ‘no bother at all to fill out daily’; 61.1% of e-dairy users indicated they ‘very much liked the way the daily diary looked’; no significant difference in participants’ acceptability of either paper or electronic diary format Technical problems: Power failure and PDA malfunction caused data from five participants to be unusable; three stylus pens broken/lost; two AC adapters required repair |

| 5 | Sorbi et al (48), 2007 (Netherlands) | Women, 24–52 years of age; n=5; 38.4±10.41 years of age | Prospective observational To determine feasibility of online digital assistance in terms of technical problems, compliance and acceptability |

Handheld PalmOne Treo 600 (Palm Inc, USA) with a dedicated server, runs on Linux supported by: Apache Web Server; Java; PostgresSQL; Tomcat Data encryption authorized by Secure Sockets Layer |

Migraine headache (validated international diagnostic criteria [43]) Attack precursors: premonitory symptoms and triggers (ad hoc*) Self-relaxation and preventative behavior (derived from the Behavioural Training Evaluation Form [47,48]) |

Time-based; 4–5 per day (cycle 1); 2–3 per day (cycle 1); mean 8.5 days (range 4–12) |

Compliance: Mean compliance for both cycles was 80.1% (78.6% in cycle 1; 86.8% in cycle 2) Acceptability: Positive ratings of user-friendliness, readability of the screen, ease of answering diary questions and clarity of instructions. Technical problems: Loss of 6.8% of data due to technical problems; software problems obstructed the storage of part feedback in cycle 1 |

*Ad hoc: developed by authors for study purposes; NRS Numerical rating scale; PDA Personal digital assistant; RCT Randomized controlled trial; SCD Sickle-cell disease

TABLE 4.

Summary of outcome studies using e-diaries

| Study number | Author (reference), year (country) | Study design | Type of diary | Diary measure type | Diary measures: Ad hoc/validated | Feasibility/compliance data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Bjorling (42), 2009 (USA) | Prospective Repeated measures, momentary electronic diary design |

Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Mean compliance rate 62.5% (range 30% to 92%) |

| 7 | Kikuchi et al (39), 2007 (Japan) | Prospective | Wrist-watch computer | Primary | Ad hoc | Mean compliance rate 96% (range not provided) |

| 8 | Barton and Blanchard (41), 2001 (USA) | Prospective Multiple baseline design |

Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc HA Index | Not available |

| 9 | Giffin et al (43), 2003 (United Kingdom) | Prospective | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 10 | Holroyd et al (40), 2007 (USA) | Prospective | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 11 | Hu et al (37), 2008 (USA) | Multisite prospective observational | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 12 | James (38), 1998 (Australia) | Double-blinded placebo-controlled crossover design | Light-weight portable computer | Primary | Ad hoc and modified versions of validated paper measures | Not available |

| 13 | Massey et al (34), 2009 (The Netherlands) | Prospective | Desktop computer | Primary | Ad hoc and modified versions of validated paper measures | Mean compliance rate 57% |

| 14 | Mathew et al (35), 2007 (USA) | Multicentre, double-blinded, placebo-controlled parallel-group (intervention) | Handheld | Primary and secondary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 15 | Ng-Mak et al (33), 2008 (USA) | Multicentre prospective | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 16 | Ng-Mak et al (32), 2007 (USA) | Multicentre observational follow-up | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 17 | Sheftell et al (31), 2005 (USA) | Randomized, double-blinded, parallel-group (intervention) | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 18 | Thorn et al (29), 2007 (USA) | Randomized controlled trial (intervention) | Desktop computer | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 19 | Strom et al (28), 2000 (Sweden) | Randomized controlled trial (intervention) | Desktop computer | Primary | Ad hoc HA index | Not available |

| 20 | Van Gerven et al (30), 1996 (The Netherlands) | Double-blinded randomized parallel-group design (intervention) | Portable computer | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

| 21 | Honkoop et al (36), 1999 (USA) | Prospective | Handheld | Primary | Ad hoc | Not available |

Ad hoc measures were developed by authors for study purposes; HA headache

EVALUATION STUDIES OF E-DIARIES

Study characteristics

Reviewed studies were conducted between 2004 and 2005, with four in the United States and one in the Netherlands. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) study design was used in two of the five studies (studies 2, 4); the remaining three studies implemented a prospective observational study design (one with iterative cycles). In the two RCTs, control group participants used paper diaries with identical outcome measures to their electronic counterparts. Study duration ranged from one week to four months (mean [± SD] 6.24±7.22 weeks) with participants logging one to five diary entries per day (1.95±1.74 entries per day). The sampling protocol in four of the five studies was time based or at prespecified times each day (studies 2, 3, 4, 5); the fifth study (study 1) featured an event-based sampling protocol in which participants made diary entries when they experienced headaches (study 1).

Characteristics of study participants

The number of participants using the e-diaries ranged from five to 94 and, collectively, all studies involved a total of 272 participants (213 headache patients). Three of the evaluation studies included only participants with headache (n=118; studies 1, 3 and 5); the remaining evaluation studies featured participants with headache (n=94), juvenile arthritis (n=50) and sickle cell disease (n=9; studies 2 and 4). Three of the evaluation studies involved only female participants between 18 and 55 years of age (studies 1, 3 and 5). The remaining two studies specifically involved youth (eight to 16 years of age [studies 2 and 4]). Four evaluation studies reported participant ethnicity (studies 1, 2, 3 and 4), and in each of these studies at least 65% of participants were Caucasian. The participants also varied in type of headache. Three studies involved participants with migraine (one with or without aura, one without aura, and one not specified; studies 1, 3 and 5); the remaining two evaluation studies involved participants with recurrent headache (study 2) and headache not specified (study 4). One study involved additional, more specific criteria for inclusion, recruiting only participants who reported at least two headache attacks in the previous month (study 3). Only one of the five reviewed evaluation studies used a community sample (study 3); the other four studies (studies 1, 2, 4 and 5) featured clinical samples.

Outcome measures

The headache e-diaries varied with regard to the components assessed, as shown in Table 2. Sensory characteristics of the headaches were captured in varying degrees across the five studies. Pain intensity/severity was captured in all five studies. Pain location was recorded in studies 1, 2 and 4, while headache duration was recorded only in study 4. Premonitory symptoms and triggers were investigated in two of the five studies (studies 3 and 5), while one study investigated associated symptoms (study 1) and another investigated somatic symptoms (study 4). Physical activity limitation was captured in studies 2 and 4, whereas study 1 investigated the interference of headache with overall functioning (usual activities at home, work and/or school). Only two of the five studies recorded what steps participants were taking to self-manage or cope with their headaches (studies 3 and 5). Other outcomes included emotional upset (study 4), premenstrual symptoms (study 1) and predicting the likelihood of headache development (study 3). Two of the studies featured ad-hoc measures that were developed by study investigators (studies 1 and 3), one study featured electronic versions of validated paper measures (study 2) and two studies used a mixture of both ad-hoc and validated paper measures (studies 4 and 5). The validated paper measures transformed for the e-diaries included: Faces Pain Scale (49), Children’s Activity Limitations Interview (50), validated body outline for pain localization (51) (study 4), Children’s Somatization Inventory (52) (study 4), and the International Headache Society’s (IHS) International Classification of Headache Disorders diagnostic criteria (53) to diagnose headache type (study 5).

Diary characteristics

The types of e-diaries used in the studies were somewhat homogenous, as shown in Table 2, with four of the five evaluation studies featuring e-diaries on a handheld device (studies 1, 2, 4 and 5), while one was delivered over the Internet on a computer (study 3). The handheld devices used were the Jornada 548 personal digital assistant (PDA) (Hewlitt-Packard, USA) (studies 2 and 4), the PalmOne Treo 600 (Palm Incorporated, USA) (study 5) and the Nino handheld device (Philips Electronics, Netherlands) (study 1). All handheld devices featured a specific question sequence and used question logic to trigger subsequent questions. Four studies provided details regarding data retrieval (studies 1, 3, 4 and 5). Handheld devices in studies 1 and 4 stored data to be uploaded to desktop computers once the diaries were returned to the research centre through a delimited text file (study 1) and synchronization cable (study 4). The handheld device in study 5 featured data transmission through the Internet, with diary answers being saved separately on a server to avoid data loss. Two of the handheld devices stored data in files that were immediately suitable for statistical packages (studies 1 and 5). The Internet delivered stored e-diary data to online servers that were immediately available to researchers (study 3).

Quality and overall psychometric evidence

The Cohen criteria (25) used to evaluate the quality and overall evidence supporting the psychometric testing of the e-diaries (Appendix I) revealed that none of the five e-diaries met any of the criteria, indicating that their psychometric properties were not described sufficiently and/or not reported at all. Overall, the five studies evaluated had poor quality or reporting according to the COSMIN checklist criteria (27). Of the 10 scales of the COSMIN, all five studies only achieved ratings on the interpretability scale, indicating that all other scales (internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, construct validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity and responsiveness) were inadequately reported and, therefore, could not be rated. Interpretability ratings for all five studies were poor.

Feasibility

Compliance: Compliance with the e-diaries was reported in four of the five evaluation studies (studies 2, 3, 4 and 5). Overall compliance was high, with a mean compliance rate of 84.1±9.88% for all four studies (range 75% to 98%). The two studies featuring an RCT design (studies 2 and 4) reported greater compliance with the e-diaries compared with paper diaries used by the control group. Study 4 reported a statistically significant difference (P<0.001), with 83% of e-diary users completing all diary entries compared with 47% of paper diary users.

Only one study provided device training (study 4) with scheduled in-home instruction on how to use the PDA. Four of the five studies provided details of added features to enhance compliance. Programmed audible alarms were used in three of the studies (studies 2, 4 and 5), with an option to convert to a visual reminder when an audible alarm was not convenient (church service, meeting or concert) in study 5. Study 4 also featured a visual reminder on the diary screen when the diary had not been completed the day before and one reminder phone call during the recording period. Monetary incentives were provided in two studies (studies 2 and 4): in study 2 participants received a $30 gift card as compensation; and in study 4 participants were given a $10 incentive when diaries were returned. Participants were also entered into a monthly draw for an additional $10 incentive for completing entries on all seven days. Finally, feedback was provided twice per day, in the form of a summary of the diary users’ current state, tips for the user and a ‘pep-up’ statement in study 5 by an anonymous coach. Study 3 featured a weekly reminder email and listed tips for remembering to complete the online diary.

Acceptability (likes and dislikes): Three studies reported on the user acceptability of headache e-diaries (studies 3, 4 and 5). All three reported positive participant ratings of acceptability, indicating that the e-diaries were user-friendly, convenient and appealing. Quantifiable satisfaction data was reported in study 4, who found that 83.3% of participants that rated the acceptability of the e-diary found it ‘very easy or easy to remember to fill out’, 72.2% of participants found it ‘no bother at all to fill out daily’ and 61.1% ‘very much liked the way the daily diary looked’. While study 1 reported a low researcher satisfaction rating of the e-diary based on the high number of technical problems encountered in the study that resulted in lost data, no participant acceptability data were reported for this study.

Technical difficulties: Of the five reviewed evaluation studies, four reported technical problems. Studies 3, 4 and 5 reported minimal technical problems with participants experiencing occasional difficulty accessing the website (study 3); hardware problems including technical failure of electronic device, broken or lost stylus pens and AC adapters requiring replacement (study 4); minor internal problems with the PDA (study 5); and software problems obstructing the storage of feedback (first cycle of study 5). Major technical problems in study 1 that caused abnormal session endings in 35% of all diary entries and 34.5% of responses to the first question to be lost resulted in researchers reporting dissatisfaction with the e-diary.

OUTCOME STUDIES USING E-DIARIES

The search strategy yielded 16 studies published between 1996 and 2009 found to be using an e-diary to obtain outcome data (28–43) (Table 4). Of these, 10 (62.5%) were prospective observational studies (studies 6 through 11, 13, 15, 16, 21); the remaining six were interventional RCT studies. The devices used in the studies varied. The majority (62.5%) used a handheld device (studies 6, 8 through 11, 14 to 17, 21); however, other studies reported using a desktop computer (18.7%) (studies 13, 18 and 19), a portable computer (12.5%) (studies 12 and 20) and a wrist watch computer (6.3%) (study 7). Reliability and validity were not reported for any of the diaries used in the outcome studies; however, despite this, 15/16 studies were using e-diaries to collect primary outcome data (studies 6 through 13, 15 to 21), with the final study using the e-diary to collect both primary and secondary outcome data (study 15). Based on the inofrmation available, the multidimensional measures used in the e-diaries were found to be ad-hoc for the most part (87.5%) (studies 6 through 11, 14 to 21), with two of the studies using a combination of ad hoc measures and modified versions of validated paper measure (studies 12, 13). Only three of these studies provided compliance data with moderate to high ratings reported (57% to 96%) (studies 6, 7, 13).

Conforming to headache and chronic pain clinical trial reporting recommendations

RCT evaluation and outcome studies were compared with the recommended headache and chronic pain guideline. None evaluated all of the outcomes outlined in any one set of guidelines; however, each assessed at least one (either primary or secondary) recommended outcome.

Pharmacological headache trial guidelines

Two RCT evaluation studies (studies 2 and 4) and the six RCT outcome studies using e-diaries (studies 12, 14, 17 through 20) were compared with the recommended pharmacological headache trial guidelines first published in 1991 (14). Frequency, the recommended primary outcome for pharmacological headache trials, was evaluated in four of the eight RCTs (studies 4, 12, 18 and 19), while one additional study (study 14) evaluated the other primary outcomes recommended for pharmacological trials: percentage of patients pain free at 2 h; and sustained pain free. Seven of the eight RCTs assessed for compliance to the pharmacological trial guidelines measured pain intensity, a recommended secondary outcome (studies 2, 4, 12, 17 through 20). Time to pain free, a recommended secondary outcome for pharmacological trials, was measured in study 17.

Behavioural headache trial guidelines

One RCT evaluation study (study 2) and the three RCT outcome studies (studies 14, 18 and 19) published after the behavioural headache trial guidelines were made available in 2005 (15) were assessed for behavioural trial guideline compliance. Frequency, the recommended primary outcome for behavioral headache trials, was evaluated in two of the four assessed RCTs (studies 18 and 19). Three of the four RCTs measured pain intensity, a recommended secondary behavioural outcome (studies 2, 18 and 19). Other secondary outcomes recommended by the behavioural headache trial guidelines included medication use, which was evaluated in two of the RCTs (studies 18 and 19); psychological symptoms, evaluated in two studies (studies 4 and 18); and headache duration, evaluated in two studies (study 2).

Chronic pain trial guidelines

Only one article, an RCT evaluation study (study 2) was published after the chronic pain guidelines became available and, therefore, is the only study compared with the IMMPACT guidelines (12,13). Study 2 measured pain intensity, a recommended primary chronic pain outcome.

DISCUSSION

The present study sought to report on the development and measurement properties of electronic pain diaries to capture the experience of headaches in children and adults and the components of these diaries and their conformity to recommended reporting guidelines for headache and chronic pain clinical trials. Despite the rapid growth in the use of electronic pain diaries in research, there is little evidence supporting the validity of e-diaries in this population. Most of the e-diaries were developed ad hoc by the investigators and only a few incorporated validated paper versions of self-reported pain outcome measures in terms of intensity, frequency, headache location and impact on functioning. There is some evidence regarding the feasibility of headache e-diaries in terms of high compliance and acceptability compared with paper diaries; however, there were several drawbacks noted in terms of technical issues reported across the five studies. Finally, the studies that used headache e-diaries as primary outcome measures did not adequately report on the essential features of the diaries (validity, sampling procedure, etc), were of poor methodological quality and did not meet the recommended reporting guidelines for headache clinical trials.

It is essential that investigations of headache treatments (especially clinical trials) use reliable and valid pain measures to ensure that the results are correctly interpreted. There appears to be the implicit assumption in these studies that if the measures are valid in paper format, the method of administering the measure is inconsequential; however, studies have found that this may not be the case (54,55). To ensure that valid and reliable measures are being used in clinical trials, when the data are not available on the psychometric properties of e-diaries, researchers need to determine the validity and reliability of the RTDC versions before using them in definitive randomized controlled trials. Researchers developing headache e-diaries should use guidelines for the development of patient-reported outcome measures such as the Food and Drug Administration guidance (56).

Feasibility is a critical component when establishing the properties of a new patient-reported outcome measure. In terms of e-diaries, feasibility has been conceptualized as compliance, acceptability and technical issues. In terms of compliance, e-diaries have been found to be superior to paper diaries. Similar to the findings in the present study, Dale and Hagen (57) found that when reviewing electronic versus paper diaries, e-diaries lead to improved protocol compliance. While compliance was measured differently across all studies, the majority reported the e-diary users to have greater numbers of diary entries at greater frequency. Additionally, the time stamp features of the PDAs precluded falsification of PDA data records (58), a prudent issue when considering the almost 80% falsification rate of paper diary data reported by the Stone et al (11) study in their comparison of paper and e-diaries. However, it is not known how factors such as training, alarms and other reminders, and monetary incentives influence compliance.

Recent reviews regarding e-diaries have highlighted the advantages of this new mode of data capture compared with paper diaries such as overcoming recall bias, diary compliance and portability issues (59). Stone and Broderick (58) also suggest that e-diaries limit distortions to past experiences that are present in recall measures, particularly the changes in frequency of nonpain episodes. Given that headache frequency is the recommended primary outcome measure of both pharmacological and behavioural headache trials, e-diaries can improve the accuracy of this outcome by minimizing recall bias. However, e-diaries can be burdensome for the respondent due to the duration of monitoring (weeks to years), length of the assessment battery comprising each diary report and the device training required at the start of diary use. Additionally, the cost of the device itself may be prohibitive, especially in the context of clinical trials involving hundreds of participants (59). Furthermore, requiring participants to carry a device specific to the e-diary in addition to devices any they already carry (smartphone, pager, etc) may create an additional perceived burden. However, multiple hand-held devices (eg, iPhone [Apple Inc, USA]) that can support e-diaries are becoming increasingly popular, especially among youth and young adults with headaches (60). Future research to develop and validate diaries across a variety of devices/platforms (ie, iPhone, Android [Google Inc, USA], personal computers) that participants can download to their own device is warranted to increase adherence, feasibility and reduce burden.

While there are many reported advantages of e-diaries (11,16), there are several drawbacks that need to be acknowledged. The present review found that four of five studies reported some technical difficulties ranging from software to hardware issues and devices being lost. These technical issues can result in loss of data that may make it difficult to determine whether data are missing at random or systematically due to these technical issues. Similarly, in a systematic review of RCTs and quasirandomized controlled trials comparing PDA and paper diaries, Dale and Hagen (57) found that five of nine reviewed studies reported power problems and/or PDA malfunctions, resulting in data loss in three of the studies. These technical issues can also affect participant compliance and acceptability of this method of diary administration. These issues highlight the importance of conducting usability and feasibility testing before evaluating the measurement properties of these diaries or their use in clinical trials.

Another area that was deficient in the headache e-diaries in the present review was that the investigators did not follow the guidelines for reporting that have been proposed in studies using e-diaries. In addition to established psychometric measurement reporting guidelines for patient-reported outcome measures, e-diaries have additional testing components, such as usability and feasibility, that must also be reported. Stone and Shiffman (16) developed such a set of criteria, which they suggest must be explicitly described in any report of clinical trials using RTDC approaches using e-diaries. These criteria include the following dimensions: providing rationale for the momentary sampling design; specifying details of sampling procedures (including participants’ discretion in responding, descriptions of missing or delayed data and suspension of prompts); description of how data acquisition questions that must be truncated to accommodate brief collection of data are designed and presented; compliance with sampling plan (particularly systematic flaws leading to missing data, hoarding or backfilling entries or fabricating reports); reporting of training and monitoring protocols; reporting on how the large amount of data are managed; and describing the approach to data analysis (16). Stone and Shiffman (16) strongly suggest these criteria be clearly documented at the outset of study protocols for readers of the trial to make appropriate judgments about generalizability and validity.

There are unique issues when deciding what outcomes should be measured using e-diaries to capture headache symptoms in which the painful events are episodic in nature. According to the IHS, the most important outcome to measure in headache sufferers is headache frequency (14). Moreover, when using e-diaries, care needs to be taken to choose the most important outcome variables to include, especially when participants will be asked to complete the diary daily and over long periods of time (several months). Stone and Shiffman (16) recommend a maximum of 20 items in daily diaries. With this in mind, we would recommend including, in addition to headache frequency, headache intensity and impact of headache on sufferer’s daily functioning including physical, role and emotional functioning, and sleep. All of these variables are suggested by both IHS15 and PedIMMPACT/IMMPACT (12,13) groups. Other variables, such as side effects and treatment satisfaction, are important, but would be better captured using paper questionnaires at end of study to reduce patient burden and the potential for poor compliance. Furthermore, consensus on the validated paper-based measures for these domains and the resultant evaluation of their psychometric properties using e-diaries will facilitate the pooling of data and increase the quality of clinical headache trials.

Finally, the present review provides researchers with directions regarding future areas of research so that we can harness the full potential of this medium to capture patient-reported outcomes in headache investigations. First, research efforts need to be directed at establishing the psychometric properties of headache e-diaries as outlined in Table 2. Second, end-users should be involved in the development and testing of these diaries. Third, they need to be developed using a phased approach that includes examining their usability and feasibility before testing their psychometric properties (61,62). Finally, the diaries should also include the most important outcomes as recommended by the IHS15 and IMMPACT (12,13) statements to keep the diary entries brief (fewer than 20 questions) and minimize respondent burden.

Study limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, because few evaluations of headache e-diaries have been conducted over the past 15 years, our findings are based on a very small number of studies. Future reliability and validity investigations will be required to establish whether e-diaries are reliably efficacious for capturing headache characteristics and precursors. Due to the limited data reported in the studies included in the present review, we were only able to provide a qualitative synthesis. In addition, several factors may limit the generalizability including the fact that studies were limited to English and that the studies found were primarily conducted in North America.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study indicate that, despite technical problems, researchers can expect higher levels of compliance and user acceptability when using headache e-diaries. However, further research focusing on the psychometric properties of e-diaries is required. It is important to ensure that the electronic questionnaires used are tested for validity and reliability against their paper counterparts to ensure that the psychometric properties are maintained. Furthermore, the items on headache e-diaries should include the most important outcomes (headache frequency, pain intensity, the impact of pain on aspects of physical, emotional and role functioning and sleep) to minimize burden and optimize compliance. While it is clear that there will be a role for paper diaries in research for the foreseeable future, e-diaries are an exciting medium that offer many advantages over traditional data collection methods.

APPENDIX I.

Criteria for evidence-based assessment

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Well-established assessment | The measure must have been presented in at least two peer-reviewed articles by different investigators or investigatory teams. |

| Sufficient detail about the measure to allow critical evaluation and replication (eg, measure and manual provided or available upon request) | |

| Detailed information (eg, statistics presented) indicating good validity and reliability in at least one peer-reviewed article. | |

| Approaching well-established assessment | The measure must have been presented in at least two peer-reviewed articles, which may be by the same investigator or investigatory team. |

| Sufficient detail about the measure to allow critical evaluation and replication (eg, measure and manual provided or available upon request). | |

| Validity and reliability information presented in either vague terms (eg, no statistics presented) or moderate values. | |

| Promising assessment | The measure must have been presented in at least one peer-reviewed article. |

| Sufficient detail about the measure to allow critical evaluation and replication (eg, measure and manual provided or available upon request). | |

| Validity and reliability information presented in either vague terms (eg, no statistics presented) or moderate values. |

Adapted from Cohen et al (25)

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, Arena JG, Teders SJ, Teevan RC, Rodichok LD. Psychological functioning in headache sufferers. Psychosom Med. 1983;44:171–82. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holroyd KA, Stensland M, Lipchik GL, Hill KR, O’Donell FS, Cordingley G. Psychosocial correlates and impact of chronic tension-type headaches. Headache. 2000;40:3–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers SW, Kruglak Gilman D, Hershey AD. Headache and psychological functioning in children and adolescents. Headache. 2006;46:1404–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mack KJ. An approach to children with chronic daily headache. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:997–1000. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206002192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metsähonkala L, Sillanpaa M, Tuominen J. Social environment and headache in 8- to 9-year old children: A follow up study. Headache. 1998;38:222–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3803222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pop PHM, Gierveld CM, Kavis HAM, Tiedink HGM. Epidemiological aspects of headache in workplace setting and the impact on the economic loss. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:171–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Olesen J. Impact of headache on sickness absence and utilization of meical services: A Danish population study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:443–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz B, Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Lost workdays and decreased work effectiveness associated with headache in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39:320–7. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmeads J, Findlay H, Tugwell P, Pryse-Phillips W, Nelson RF, Murray TJ. Impact of migraine and tension-type headache on lifestyle, consulting behaviour, and medication use: A Canadian population survey. Can J Neurol Sci. 1993;20:131–7. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100047697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karwautz A, Wober C, Lang T, et al. Psychosocial factors in children and adolescents with migraine and tension-type headache: A controlled study and review of literature. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:32–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.1999.1901032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone A, Shiffman S, Schwartz J, Broderick J, Hufford M. Patient compliance with paper and electronic diaries. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:182–99. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, et al. Core outcome domains and measure for pediatric acute and chronic/ recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. Clin J Pain. 2008;9:771–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, et al. Developing outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2006;125:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: Second edition. Cephalalgia. 20:765–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00117.x. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penzien DB, Andrasik F, Freidenberg BM, et al. Guidelines for trials of behavioral treatments for recurrent headache, first edition: American Headache Society Behavioral Clinical Trials Workgroup. Headache. 2005;45(Suppl 2):S110–S132. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.4502004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone A, Shiffman S. Capturing momentary, self-report data: A proposal for reporting guidelines. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:236–43. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stinson JN. Improving the assessment of pediatric chronic pain: Harnessing the potential of electronic diaries. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:59–64. doi: 10.1155/2009/915302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Reliability. In: Portney LG, Watkins MP, editors. Foundations of clinical research — application to practice. 2nd edn. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Health; 2000. pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:1–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Veldhuyzen Van Zanten SJ, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring quality of life in clinical trials: A taxonomy and review. CMAJ. 1989;140:1441–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang MH. Longitudinal construct validity: Establishment of clinical meaning in patient evaluative instruments. Med Care. 2000;38(Suppl 2):84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens B, Gibbins S. Clinical utility and clinical significance in the assessment and management of pain in vulnerable infants. Clin Perinatol. 2002;29:459–68. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(02)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stinson JN, Kavanagh T, Yamada J, Gill N, Stevens B. Systematic review of the psychometric properties, interpretability and feasibility of self-report pain intensity measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents. Pain. 2006;125:143–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen LL, La Greca AM, Blount RL, Kazak AE, Holmbeck GN, Lemanek KL. Introduction: Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:911–5. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education 1999.

- 27.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strom L, Pettersson R, Andersson G. A controlled trial of self-help treatment of recurrent headache conducted via the Internet. J Consult Clin Psych. 2000;68:722–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorn BE, Pence LB, Ward LC, et al. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioural treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J Pain. 2007;8:938–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Gerven JMA, Schoemaker RC, Jacobs LD, et al. Self-medication of a single headache episode with ketoprofen, ibuprofen or placebo, home-monitored with and electronic patient diary. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996:42474–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.43613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheftell FD, Dahlof CGH, Brandes JL, Agosti R, Jones MW, Barrett PS. Two replicate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of the time to onset of pain relief in the acute treatment of migraine with a fast-disintegrating/ rapid-release formulation of sumatriptan tablets. Clin Ther. 2005;27:407–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng-Mak DS, Cady R, Chen YT, Ma L, Bell DF, Hu XH. Can migraineurs accurately identify their headaches as “Migraine” at attack onset? Headache. 2007;47:645–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng-Mak DS, Ma L, Hu XH, Chen YT. Treat-early and treat-mild: Role of fast vs. slow escalation of headaches. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:465–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massey EK, Garnefski N, Gebhardt WA, van der Leeden R. Daily frustration, cognitive coping and coping efficacy in adolescent headache: A daily diary study. Headache. 2009;49:1198–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathew NT, Finlayson G, Smith TR, et al. Early intervention with almotriptan: Results of the AEGIS trial (AXERT Early Migraine Intervention Study) Headache. 2007;47:189–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honkoop PC, Sorbi MJ, Godaert GLR, Spierings ELH. High-density assessment of the HIS classification criteria for migraine without aura: A prospective study. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:201–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019004201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu XH, Ng-Mak D, Cady R. Does early migraine treatment shorten time to headache peak and reduce its severity. Headache. 2008;48:914–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James JE. Acute and chronic effects of caffeine on performance, mood, headache, and sleep. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;38:32–41. doi: 10.1159/000026514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kikuchi H, Yoshiuchi K, Ohashi K, Yamamoto Y, Akabayashi A. Tension-type headache and physical activity: An actigraphic study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1236–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holroyd KA, Drew JB, Cottrell CK, Romanek KM, Heh V. Impaired functioning and quality of life in severe migraine: The role of catastrophizing and associated symptoms. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1156–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barton KA, Blanchard EB. The failure of intensive self-regulatory treatment with chronic daily headache: A prospective study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2001;26:311–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1013153804310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjorling EA. The momentary relationship between stress and headache in adolescent girls. Headache. 2009;49:1186–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giffin NJ, Ruggiero L, Lipton RB, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine: An electronic diary study. Neurology. 2003;60:935–40. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000052998.58526.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldberg J, Wolf A, Silberstein S, et al. Evaluation of an electronic diary as a diagnostic tool to study headache premenstrual symptoms in migraines. Headache. 2007;47:384–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewandowski AS, Paleramo TM, Kirchner HL, Drotar D. Comparing diary and retrospective reports of pain and activity restriction in children and adolescents with chronic pain conditions. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:299–306. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181965578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moloney MF, Aycock DM, Cotsonis GA, Myerburg S, Farino C, Lentz M. An internet-based migraine headache diary: Issues in internet-based research. Headache. 2009;49:673–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palermo TM, Valenzula D, Stork PP. A randomized trial of electronic versus paper pain diaries in children: Impact on compliance, accuracy, and acceptability. Pain. 2004;107:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sorbi MJ, Mak SB, Houtveen JH, Kleiboer AM, van Dooren LJP. Mobile web-based monitoring and coaching: Feasibility in chronic migraine. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e38. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.5.e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, et al. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: Development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41:139–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palermo TM, Witherspoon D, Cant MC, Valenzuela D, Drotar D. Development and validation of the Child Activity Limitations Interview: A measure of pain-related functional limitations. [Poster presentation]. The Sixth International Symposium on Paediatric Pain; Sydney. June 15 to 19, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lester N, Lefebvre JC, Keefe FJ. Pain in young adults – III: Relationships of three pain-coping measures to pain and activity interference. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:291–300. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker LS, Garber J, Smith CA, Van Slyke DA, Claar RL. The relation of daily stressors to somatic and emotional symptoms in children with and without recurrent abdominal pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 69:85–91. 200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society, authors The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):1–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gwaltney CJ, Shields AL, Shiffman S. Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: A meta-analytic review. Value Health. 2008;11:322–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buchanan T, Ali T, Heffernan TM, et al. Nonequivalence of on-line and paper-and-pencil psychological tests: The case of the prospective memory questionnaire. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37:148–54. doi: 10.3758/bf03206409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcomes: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. < www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/06d-0044-gdl0001.pdf> (Accessed May 19, 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Dale O, Hagen KK. Despite technical problems personal digital assistants outperform pen and paper when collecting patient diary data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone AA, Broderick JE. Real-time data collection for pain: Appraisal and current status. Pain Med. 2007;8(S3):S85–S93. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pasecki TM, Hufford MR, Solhan M, Trull TJ. Assessing clients in their natural environments with electronic diaries: Rationale, benefits, limitations, and barriers. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:25–43. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.PEW Internet and American Life Project Trends in cell phone usage and ownership. < www.pewinternet.org/Presentations/2011/Apr/FTC-Debt-Collection-Workshop-Cell-Phone-Trends.aspx> (Accessed May 30, 2011)

- 61.Stinson J, Petroz G, Tait G, et al. E-Ouch: Usability testing of an electronic chronic pain diary for adolescents with Arthritis. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:295–305. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000173371.54579.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stinson JN, Petroz GC, Stevens BJ, et al. Working out the kinks: Testing the feasibility of an electronic pain diary for adolescents with arthritis. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:375–82. doi: 10.1155/2008/326389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]