Background: Cubilin is a multiligand endocytic receptor necessary for early embryonic development.

Results: Cubilin expressed in the developing head, namely the cephalic neural crest, binds Fgf8 and is required for cell survival and head morphogenesis.

Conclusion: Cubilin, Fgf8, and FgfRs act synergistically to promote anterior cell survival.

Significance: Cubilin is a novel modulator of the Fgf8-FgfR signaling activity.

Keywords: Cell Death, Development, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Molecular Cell Biology, Mouse, Xenopus, Cubilin, Megalin

Abstract

Cubilin (Cubn) is a multiligand endocytic receptor critical for the intestinal absorption of vitamin B12 and renal protein reabsorption. During mouse development, Cubn is expressed in both embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues, and Cubn gene inactivation results in early embryo lethality most likely due to the impairment of the function of extra-embryonic Cubn. Here, we focus on the developmental role of Cubn expressed in the embryonic head. We report that Cubn is a novel, interspecies-conserved Fgf receptor. Epiblast-specific inactivation of Cubn in the mouse embryo as well as Cubn silencing in the anterior head of frog or the cephalic neural crest of chick embryos show that Cubn is required during early somite stages to convey survival signals in the developing vertebrate head. Surface plasmon resonance analysis reveals that fibroblast growth factor 8 (Fgf8), a key mediator of cell survival, migration, proliferation, and patterning in the developing head, is a high affinity ligand for Cubn. Cell uptake studies show that binding to Cubn is necessary for the phosphorylation of the Fgf signaling mediators MAPK and Smad1. Although Cubn may not form stable ternary complexes with Fgf receptors (FgfRs), it acts together with and/or is necessary for optimal FgfR activity. We propose that plasma membrane binding of Fgf8, and most likely of the Fgf8 family members Fgf17 and Fgf18, to Cubn improves Fgf ligand endocytosis and availability to FgfRs, thus modulating Fgf signaling activity.

Introduction

Cubn encodes a 460-kDa peripheral membrane protein composed of eight epidermal growth factor repeats and 27 CUB domains (complement C1r/C1s, urchin Egf, bone morphogenic protein-1), which carry multiple potential sites for interaction with proteins, sugars, and phospholipids (1). Cubn is the physiological receptor for intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 in the gut and for albumin in the kidney (2). Distinct sets of mutations in CUBN either result in the Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome characterized by megaloblastic anemia and proteinuria (3) or in albuminuria and most likely end-stage kidney disease (4). Recently identified novel genetic polymorphisms in CUBN were evaluated as risk factors for neural tube defects (5, 6). It remains to be defined whether defects of this type are associated with the known Cubn implication in vitamin B12 homeostasis or with a novel developmental role of Cubn.

During mouse embryonic development, Cubn is expressed in various embryonic tissues as well as in the extra-embryonic visceral endoderm (7). Cubn gene deletion perturbs the formation of both embryonic and extra-embryonic derivatives, including somites and blood vessels, and leads to embryo lethality (8). Because extra-embryonic Cubn is critical for endocytosis of various maternally derived nutrients, including high density lipoproteins, a source of cholesterol (9, 10), the mouse knock-out phenotype was essentially attributed to nutrient deficiency resulting from a deficient maternal to fetal transport (8).

A recurrent difficulty when studying Cubn is to conciliate its endocytic function with its structure. Cubn lacks a trans-membrane domain (11). The internalization of Cubn-ligand complexes absolutely depends on the co-expression of additional proteins. We and others previously identified the trans-membrane proteins Lrp2 and Amn as endocytic partners for Cubn in the gut, kidney, and extra-embryonic visceral endoderm (11–13). Lrp2 is the only currently known Cubn partner also to be expressed along with Cubn in the early embryo (7). In this context, it is interesting to note that lack of embryonic Lrp2 perturbs forebrain development (14, 15) and that in Lrp2 null mutants the internalization of Cubn ligands is decreased (2, 16).

In this study, we focus on the role of embryonic Cubn during the early steps of anterior head formation. We show that Cubn is expressed in the anterior cephalic mesenchyme, cephalic neural crest cells (CNCCs),3 and forebrain neuroepithelium and that it is critical for cell survival and rostral head morphogenesis in the mouse, frog, and chick embryos. We provide in vivo evidence that Cubn acts synergistically with Fgf8, a morphogen essential for CNCC survival, migration, and proliferation and for telencephalic patterning. We identify Fgf8 as a novel Cubn ligand and show that Cubn is necessary for Fgf8-dependent phosphorylation of the Fgf targets MAPK/ERK in vitro. Furthermore, we provide evidence that Cubn and the Fgf8 receptor FgfR3 functionally interact in the developing head.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Animal procedures were conducted in strict compliance with approved institutional protocols and in accordance with the provisions for animal care and use described in the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC). Sox2.Cre (B6.Cg-Tg (Sox2-cre) 1AmcJ) and Foxg1.Cre (129.Cg-Foxg1tm1(cre)Skm/J) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). CubnLox/Lox mice (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B) have been described previously (2). The midnight before the morning with a copulation plug was considered as embryonic day 0 (E0.0). A small fragment of embryos or a piece of yolk sac was used for genotyping according to standard procedures. The absence of residual Cubn expression was confirmed by Western blotting using various monoclonal and polyclonal anti-Cubn antibodies that detect all Cubn extracellular modules, i.e. both EGF and CUB domain regions (supplemental Fig. 1C).

In Situ RNA Hybridization

Heart-beating embryos were fixed and analyzed by whole-mount in situ RNA hybridization according to standard procedures.

Simultaneous Detection of Cell Death and Proliferation

Lysotracker Red (Invitrogen, DND99) staining was described previously (17). For cell proliferation, anti-phospho-histone H3 (1:250, Millipore, Molsheim, France) followed by Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:200, Invitrogen) was used. Nuclear staining was achieved by a 20-min incubation in Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Images were collected by confocal microscopy (LSM710 ConfoCor 3, Carl Zeiss) and processed using ImageJ software. Total numbers of Lysotracker- and pH 3-positive profiles were counted in 15 and 23 consecutive sections for E8.75 and E9.25 embryos, respectively; in some cases four consecutive medial or more superficial sections were used.

Immunocytochemistry and Vital Staining

Fixed whole embryos or frozen sections (10 μm thick) were processed for immunocytochemistry using rabbit anti-Cubn (1:1,000), sheep anti-Lrp2 (1:4,000), rat anti-PECAM1 (1:75; Pharmingen), or rabbit-anti-Tfap2a (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. In some cases frozen sections were counterstained with Nissl (Sigma).

Protein Analysis

Embryos and subconfluent cells were lysed in a PBS buffer containing 10 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, 6 mm CaCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm Na3VO4 (Sigma), and Complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche Diagnostics), 2 mm sodium orthovanadate, and phosphatase inhibitor mixture 1 (Sigma).

For Western blot analysis, 10 μg of total protein was applied to each well. Equal loading was verified by blotting for GAPDH. Primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-P-Akt (Ser-473; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling); total anti-Akt (1:1,000; Cell Signaling); goat anti-BMP7 (1:3,000; Abcam); goat anti-β-catenin (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, C-18); mouse anti-P-β-catenin (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1B11); rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:2,500; Cell Signaling, 9661); goat anti-chordin (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, V-18); mouse anti-Cubn (1:4,000) (18); rabbit anti-Cubn (1:5,000); rabbit anti-P-Erk1/2 (Thr-202/204; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-Erk1/2 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling); mouse anti-Fgf2 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-Fgf3 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, MSD1); goat anti-Fgf8b (1:1,000; AF423-NA, R&D Systems); mouse anti-Fgf8b (1:1,000; MAB323, R&D Systems); rabbit anti-Fgf8 (1:500, 7916, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); goat anti-Fgf15 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, P-20); mouse anti-Fgf17 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, B-4) and goat anti-Fgf17 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, C-14); rabbit anti-FgfR1 (1:1000; 52153, Abcam); rat anti-FgfR2c (1:1,000; MAB716, R&D Systems); mouse anti-FgfR3c (1:1,000; MAB7662, R&D Systems); rabbit anti-Noggin (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Fl-232); rabbit anti-PSmad1 (Ser-206; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-Smad1 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-PSmad1/5/8 (1:1,000; Pharmingen); rabbit anti-Wnt1 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, H-89); rabbit anti-Wnt3 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, H-70); and goat anti-Wnt8b (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 25177).

Morpholino Oligonucleotide Design and Injection in Xenopus laevis Eggs

Embryos were obtained as described previously (19). A 122-bp sequence was amplified from St.36 cDNA using primers corresponding to the first exon of X. tropicalis Cubn gene model (5′-AGACTCACAGCTGGAGGGAA-3′; 5′-TCTCCAGACTCGCACATCAG-3′) and was further expanded using 5′rapid amplification of cDNA ends-PCR (Smarter RACE cDNA amplification kit, Clontech–Takara). The 5′ region of X. laevis Cubn mRNA was cloned to design two translation-blocking morpholinos. Specific morpholino targeting the start codon (MoCubn, 5′-AAGGTAGGAAGCCTCGGGAAAGCAT-3′) or the 5′UTR (Mo1Cubn, 5′-CCCCATGTACTCTGCGTTGATACCA-3′) was used (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR). MoFgf8 (5′-GGAGGTGATGTAGTTCATGTTGCTC-3′) targeting Fgf8 as well as an unrelated control morpholino (5′-TCGTCCACTTGTTCGCTCAATCGAT-3′) were previously described. Morpholinos, at doses ranging from 2.5 to 10 pmol, were microinjected into the two blastomeres at the 2-cell stage for protein analysis. For anterior developmental analysis, the morpholinos were injected at the 8-cell stage. To target knockdown to the anterior left side of the head and to control proper targeting, doses varying from 0.125 to 1 pmol were injected into the left dorso/animal blastomere together with 5 ng/nl rhodamine-lysinated dextran (Invitrogen) as lineage tracer. The right side was used as a control. Standard procedures were used for in situ RNA hybridization.

RT-Quantitative PCR

X. laevis Cubn primers sequences were chosen in the 3′ end of the mRNA as follows: forward, 5′-GAGACGACAAGTTCATCTTCATGC-3′ (nts 183); reverse, 5′-CCGAGTCACTGCCATTTCTCA-3′ (nts 243). Cytoskeletal actin was used as reference gene as follows: forward, 5′-TCTATTGTGGGTCGCCCAAG-3′ (nts 158); reverse, 5′-TTGTCCCATTCCAACCATGAC-3′ (nts 208). Quantification of X. lævis Cubn mRNA expression was carried out at late neurula stage (st. 20). The anterior neural plate was dissected out. The embryo was further dissected into truncal and caudal halves. Batches of six explants were processed for RNA extraction using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen SA). One μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems).

Cell Culture

Brown Norway rat yolk sac epithelial cells transformed with mouse sarcoma virus (BN/MSV) were grown as described previously (18). BN/MSV cells were seeded in 24-well plates and used at subconfluence. Overnight serum-starved cells were incubated for 5 min with 5 ng/ml Fgf8b (catalog no. 423-F8, R&D Systems) or 5 ng/ml heparin-stabilized FGF2 (F9786; Sigma). Recombinant Cubn fragments expressing CHO cells were previously described (20).

SPR Analysis, Immunoprecipitation

SPR analysis was performed on a Biacore 3000 as described previously (21). Cubilin was immobilized (at 10−15 g ml−1) on a CM5 chip, and the remaining coupling sites were blocked with 1 m ethanolamine. The sample and running buffer was 10 mm HEPES, 150 mm (NH4)2SO4, 1.5 mm CaCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 0.005% Tween 20, pH 7.4 (all products from Sigma). Recombinant mouse FGF8b and Fgf8a (catalog nos. 423-F8 and 4745-F8, R&D Systems) were applied in increasing concentration, and the sensor chip regenerated in a 10 mm glycine-HCl buffer after each analytic cycle. The SPR signal was expressed in relative response units as the response obtained in a control flow channel was subtracted. Recombinant FgfR1 (catalog nos. 658 and 655, R&D Systems) and FgfR2 (catalog nos. 665, 716, R&D Systems) were used. Mouse Cubn was purified by affinity chromatography of renal extracts on an intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 column as described previously.

Immunoprecipitation

Cephalic extracts of E8.75–9.0 embryos or cell lysates of conditioned CHO media were applied on Sepharose A or Sepharose G (GE Healthcare) beads coupled with anti-Cubn, anti-Fgf8b, or anti-Fgf17 antibodies. Immunoprecipitation was performed using standard procedures. Control immunoprecipitation was performed with rabbit or mouse preimmune serum. All precipitated proteins were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and were detected by autoradiography using ECL reagents as described by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare).

Functional Assays in Avian Embryos

dsRNA were synthesized from cDNA encoding for the following targeted genes: dsCubn1 (nts 581–883, exons 7–8); dsCubn2 (nts 6680–7034, exons 44–45); dsFgfR1 (nts 605–891, exons 5–7); dsFgfR2 (nts 785–1106, exons 5–6); dsFgfR3 (nts 612–927, exons 6–7). In ovo electroporation was performed as described previously (22). Briefly, electroporation in the developing head was performed in chick embryos at 5–6 somites stage (5–6 ss, i.e. 30 h of incubation at 37 °C). Exogenous nucleic sequences dsCubn, dsFgfR1, dsFgfR2, and dsFgfR3 or combinations (200 ng/μl) and RCAS-Noggin were mixed in a solution of Fast Green FCF (0.01%, Sigma), bilaterally transfected to the cephalic NC cells or transfected to the cephalic NC cells and cephalic ectoderm. For control series, nonannealed sense and antisense RNA strands corresponding to the sequences of the targeted genes were transfected at the same concentrations. The efficiency of the silencing was confirmed by in situ hybridization analysis. For protein supplementation, heparin-acrylic beads (Sigma) soaked with a solution of Fgf8b recombinant protein (5 μm; R&D Systems) were used.

Statistical Analysis and Graph Plotting

SigmaStat (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA) was used for data analysis. Excel (Microsoft) was used to plot data.

RESULTS

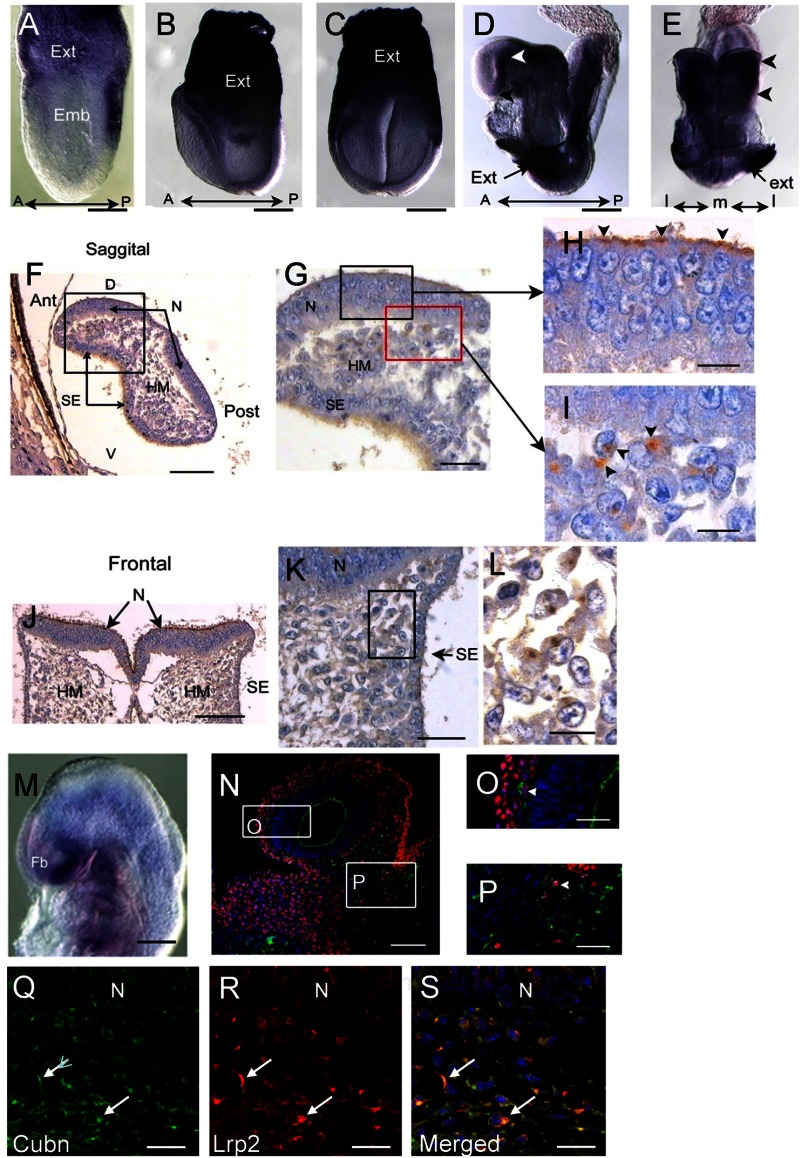

Cubn Is Expressed in the Cephalic Neuroepithelium and Neural Crest Cells during Early Somite Stages

In pre-somitic stages, Cubn mRNA is strongly expressed in the extraembryonic visceral endoderm (Fig. 1, A–C) (7). During neurulation (E8.5, 5–7 ss) Cubn mRNA is found in the prospective forebrain neuroepithelium, the optic eminences, and the cephalic mesenchyme (Fig. 1, D and E). Cubn immunostaining reveals that Cubn is distributed at the apical pole (7) of the neuroepithelial cells (Fig. 1, F–H and J) as well as along the plasma membrane of cells adjacent to the cephalic neural folds and the surface ectoderm (Fig. 1, G and I–L). At E9.0 (13–16 ss) Cubn mRNA and protein are readily detected in the ventral forebrain and pharyngeal regions and at low levels in the mesenchyme of the dorsal forebrain, mid-, and hindbrain (Fig. 1, M and N). Double immunostaining for Cubn and the neural crest marker Tfap2α shows that Cubn is partly expressed in Tfap2α-positive CNCCs (Fig. 1, N–P). In these cells, Cubn is also co-expressed with Lrp2 (Fig. 1, Q–S).

FIGURE 1.

Cubn distribution in the early mouse embryo. A–C, strong Cubn mRNA expression in the extra-embryonic (Ext) tissues during gastrulation (A, lateral view) and early headfold stages (B and C, lateral and frontal views). D–L, Cubn mRNA and protein expression at E8.5; Cubn is found in the forebrain (white arrowhead in D, lateral view) and the cephalic mesenchyme (arrowheads in E, frontal view); black arrowhead in D points to the ANR. F–L, sagittal (F–I) and frontal (J–L) paraffin sections through the forebrain show Cubn distribution at the apical pole of neuroepithelial cells (arrowheads in H) and at the plasma membrane of mesenchymal cells (arrowheads in I). M, Cubn mRNA (lateral view) in the forebrain (Fb), the cephalic mesenchyme of the fore-, mid-, and hindbrain regions, and the pharyngeal region at E9.0. N–P, sagittal cryosection of an E9.0 embryo shows partial co-localization of Cubn (green) and Tfap2α (red) in the migratory neural crest at the level of the forebrain (O) and midbrain (P) mesenchyme. Cubn is also detected in the forebrain (N and O). Q–S, Cubn (in green) and Lrp2 (in red) co-localize in the migratory neural crest of the same embryo (arrows). A, anterior; P, posterior; D, dorsal; V, ventral; m, medial; l, lateral; emb, embryonic; hm, head mesenchyme; N, neuroepithelium; se, surface ectoderm. Scale bars, A, 175 μm; B and C, 200 μm; D and E, 250 μm; F and J, 125 μm; G and K, 80 μm; H, I, and L, 50 μm; M, 250 μm; N, 175 μm; O and P, 75 μm; Q–S, 15 μm.

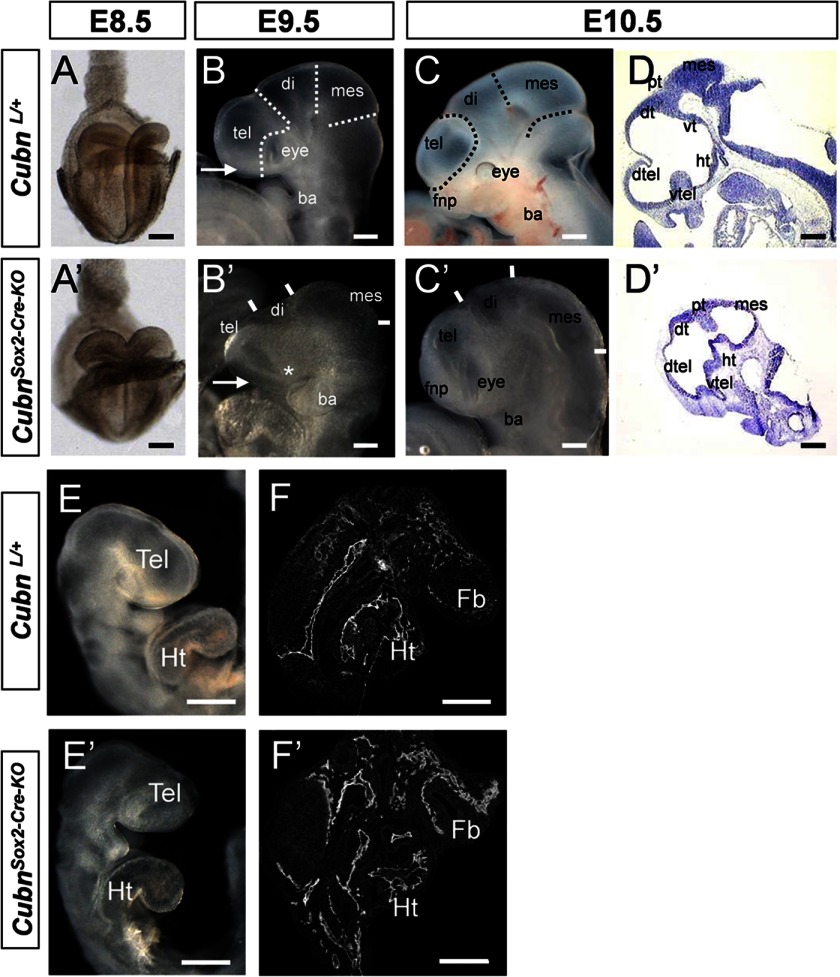

Sox2-Cre-mediated Ablation of Embryonic Cubn Leads to Rostral Head Hypoplasia by E9.5

To inactivate embryonic Cubn, we used a floxed Cubn allele (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B) and the Sox2-Cre transgene. Whereas the maternally inherited transgene recapitulates the null phenotype (supplemental Fig. 1, C–M), as reported previously (8), the paternally inherited Sox2-Cre transgene that we used here induces recombination only in epiblast cells from E6.5 onward (24) and leads to inactivation of Cubn in both the neuroepithelium and the mesenchyme (supplemental Fig. 1, N–S). CubnL/+;Sox2-Cre heterozygous mice were viable and morphologically normal. CubnL/L; Sox2-Cre (hereafter designated as Cubnsox2-cre-KO) mutants did not develop beyond E12.5 (Table 1). At E8.5 (Fig. 2, A and A′), the morphology of the Cubnsox2-cre-KO mutants was similar to that of the controls. From E9.5 (∼25 ss) onward and despite the apparently normal body axis and heart formation, the forebrain, in particular the telencephalon, was markedly reduced in size (33% compared with the controls, n = 7), and the optic vesicles were hypoplastic or absent (Fig. 2, B–F′). Despite the reduction, the general prosomeric organization of the mutant forebrain was preserved until E10.5 (Fig. 2, D and D′).

TABLE 1.

Embryonic lethality of CubnSox2-cre-KO mutants

| CubnL/L × CubnL/+;Sox2-Cre intercross | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CubnL/+, CubnL/L | CubnLL/+;Sox-Cre | CubnL/L;Sox2-Cre | Total | |

| E9.5 | 206 (58%) | 78 (22%) | 69 (20%) | 353 |

| E12.5 | 41 (73%) | 15 (27%) | 0 | 56 |

| 50% | 25% | 25% | ||

FIGURE 2.

Epiblast-specific inactivation of mouse Cubn impairs early head formation. A–F′, morphology of CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants and wild-type littermates between E8.5 and E10.5. A and A′, normal morphology at E8.5 (frontal view). B–C′, mutant telencephalon (tel), eye (asterisk in B′), and frontonasal process (fnp, arrows in B and B′) are reduced at E9.5 and 10.5 (lateral views). D and D′, sagittal cryosections showing a marked reduction of the mutant ventral (vtel) and dorsal telencephalon (dtel). E and E′, normal heart positioning and looping in the mutant at E9.5. F and F′, PECAM-1 immunostaining on sagittal cryosections through the forebrain and heart shows well developed blood vessels in both the mutant and control embryos. Di, diencephalons; dt, dorsal thalamus; fb, forebrain; fp, floorplate; ht, hypothalamus; Ht, heart; mes, mesencephalon; vt, ventral thalamus; pt, pretectum. Scale bars, A, 300 μm; B–F, 200 μm.

To find out whether Cubn is necessary in the early forebrain neuroepithelium, we used the Foxg1-Cre allele widely expressed in the forebrain and the facial ectoderm around E9.0 (25). Despite Cubn deletion, residual Cubn immunostaining was still detectable in the telencephalon of E10.5 CubnL/L;Foxg1-Cre mutants. Telencephalic development was normal in these mutants, and only minor cortical defects, including the absence of corpus callosum, could be evidenced at later stages (supplemental Fig. 2). We therefore focused on the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants.

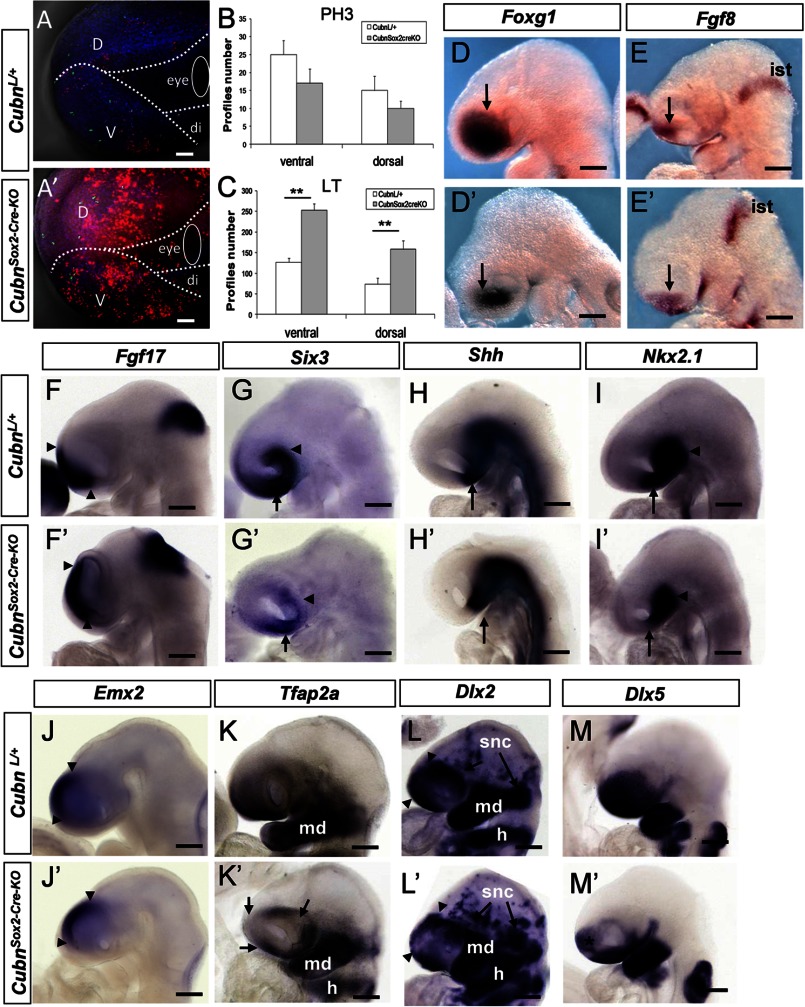

Forebrain and Face Hypoplasia in E9.25 CubnSox2-Cre-KO Mutants Correlates with Decreased Cell Survival

At E9.25 (∼20 ss), prior to the appearance of major telencephalic hypoplasia, cell proliferation evidenced by the M-phase cell cycle marker phospho-histone H3 (PH3) was not modified in the cephalic region of CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants (Fig. 3, A, A′, and B, and supplemental Fig. 3, A and B′). However, cell death, followed by the fluorescent dye Lysotracker (26), was significantly increased in the anterior mutant head (Fig. 3, A, A′, and C), both in the ventral and dorsal cephalic mesenchyme (supplemental Fig. 3, A and A′). At this stage, Lysotracker staining was marginal in the telencephalic neuroepithelium (supplemental Fig. 3, B and B′). Immunoblotting of E9.25 anterior cephalic extracts showed increased expression of activated caspase-3 in the mutants (supplemental Fig. 3C), indicating enhanced apoptosis.

FIGURE 3.

Increased apoptosis and impaired expression of CNCC markers in the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutant heads around E9.25. A and A′, representative lateral views of control and CubnSox2-Cre-KO embryos stained with Lysotracker (in red) and anti-phospho-histone H3 (in green). Dotted lines demarcate the ventral cephalic region (v), dorsal cephalic region (d), and diencephalic region (di) of E9.25 control (A) and mutant (A′) embryos. B and C, cell proliferation is similar at E9.25 (B), whereas the number of Lysotracker+ (LT) cells (C) is significantly increased in the mutant forehead (mean ± S.E., n = 3 embryos of each genotype; Student's t test, p < 0.05). D–M′, representative whole-mount mRNA staining of control (D–M) and mutant (D′–M′) embryos around E9.25. D and D′, reduced expression domain of Foxg1 in the mutant telencephalon (arrows). E and E′, Fgf8 is normally expressed in the commissural plate (arrow) and the isthmus (ist). F and F′, Fgf17 is normally detected at the commissural plate (arrowheads) and isthmus. G and G′ reduced expression domain of Six3 in the ventral telencephalon (arrow) and eye region (arrowhead). H and H′, Shh is lost in the mutant preoptic area (arrow). I and I′, down-regulation of Nkx2.1 in the mutant preoptic area (arrow) but not the hypothalamus (arrowhead). J and J′, dorsal domain of Emx2 is conserved (arrowheads). K and K′, Tfap2a displays a patchy distribution in the mutant telencephalon and periocular region (arrows). L and L′, patchy Dlx2 expression in the mutant rostral cephalic tissues (arrowheads), and in migratory cephalic neural crest cells that contribute to the neurogenic sensory cranial ganglia (snc; arrows). Dlx2 is normally expressed in the mandibular (md) component of the first branchial arch and in the hyoid (h). M and M′, down-regulation of Dlx5 in the mutant rostro-ventral cephalic tissues (asterisk). Lateral views, anterior is to the left. Scale bars, A, 75 μm; D–M, 200 μm.

Forebrain Patterning Is Maintained in E9.25 CubnSox2-Cre-KO Mutants

We next performed a detailed molecular analysis of the forebrain. Regional specification of the forebrain is controlled by at least three signaling centers that work synergistically and regulate each other (27–30). The rostral patterning center expresses Fgfs, including Fgf8, and controls the size and ventral patterning of the forebrain. The dorsal patterning center expresses Bmps and Wnts and is involved in the development of dorsal-caudal structures; the ventral patterning center expresses Shh. If Shh is lost, Bmp activity and Bmp-responsive genes are up-regulated, and Fgf8 expression is lost. Furthermore, excess of Bmps down-regulates both Fgf8 and Shh.

Foxg1, Fgf8, and Fgf17 were normally distributed in the anterior telencephalon of ∼E9.25 CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants (Fig. 3, D–F′). The occupancy percentage of Foxg1 in the telencephalon was identical in the mutants and wild-type littermates (35% versus 33%, respectively, n = 4) indicating that the reduction of the Foxg1 expression domain was due to the hypoplasia of the forebrain. Similarly, the expression domain of Six3 was reduced in the mutant hypoplastic rostroventral telencephalon and optic vesicles (Fig. 3, G and G′). Shh was absent from the mutant preoptic area only (Fig. 3, H and H′), and Nkx2.1, which is necessary in the ventral forebrain for the activation of Shh, was also absent from the preoptic area but remained normal in the hypothalamus (Fig. 3, I and I′). Spry1, an Fgf signaling antagonist, was present in the mutant commissural plate and isthmus but did not expand ventrally in the ventral cephalic ectoderm (supplemental Fig. 3, D and D′). Emx2 along the dorsal telencephalon (Fig. 3, J and J′) and Bmp7 at the dorsal midline were similarly expressed in the wild-type and mutant embryos (supplemental Fig. 3, E and E′). Finally, the diencephalic marker Wnt8b was normally expressed in the mutants, and En2 was normally detected at the diencephalic-mesencephalic boundary (supplemental Fig. 3, F and G′). The above data show that, despite the strong reduction of the forebrain tissue and the discrete patterning defects, forebrain organization is maintained in the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants.

Abnormal Distribution of CNCCs Contributes to Head Defects in CubnSox2-Cre-KO Mutants

CNCC is a migratory population that derives from the dorsal fore-, mid-, and hindbrain and contributes to head morphogenesis. The survival, migration, and patterning of CNCCs require signals of the previously cited patterning centers (31–33).

The rostroventral expression of the CNCC markers Tfap2α and Dlx2 was patchy at the level of the mutant telencephalon and in the periocular region. These markers were normally expressed in the first brachial arch (Fig. 3, K–L′). The ectodermal and CNCC marker Dlx5 was decreased rostrally at the level of the mutant telencephalic region but remained expressed in the ventral most cephalic ectoderm and brachial arch region (Fig. 3, M and M′). Thus, around E9.25, a stage at which in wild-type embryos the spread of the CNCC over the forebrain and first brachial arch region is complete, the distribution of representative CNCC markers is abnormal in the mutants suggesting that defective migration and/or survival of the CNCC in the rostral head contributes to the cephalic hypoplasia in the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutant embryos.

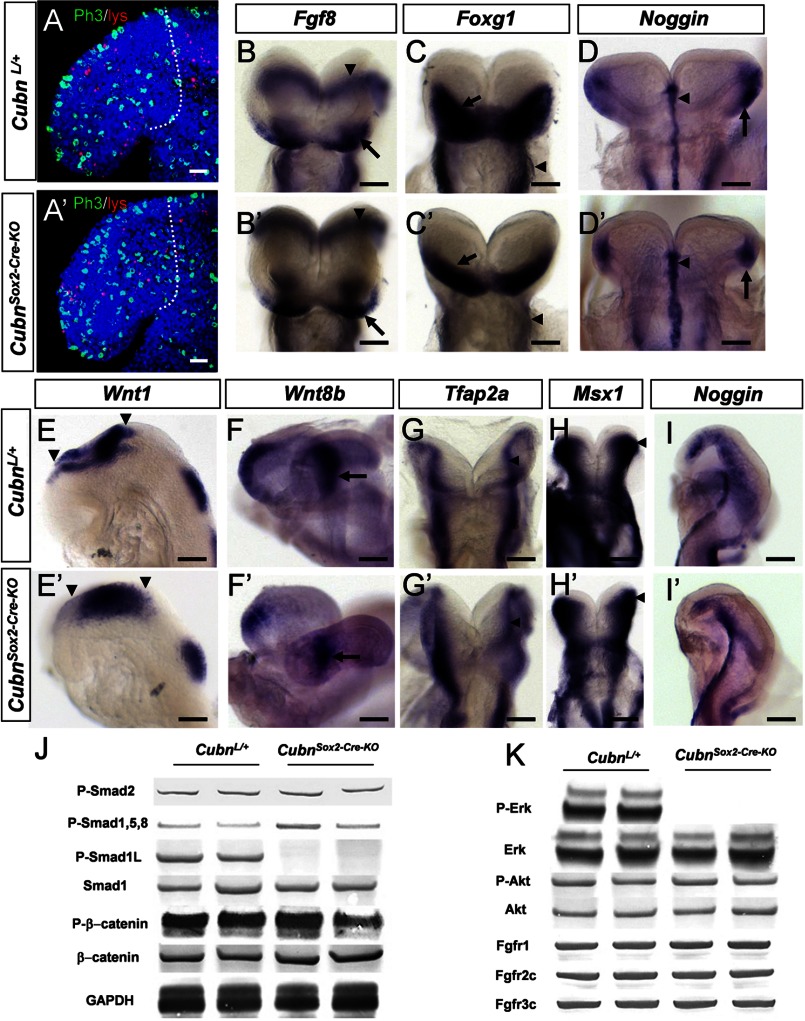

Normal Forebrain Regionalization and Perturbed Fgf Signaling in E8.75 CubnSox2-Cre-KO Mutants

To identify the onset of the defects, we analyzed mutant embryos at earlier developmental stages. We could not see any alteration in the expression of the early anterior neuroectoderm and rostrolateral ectoderm markers Otx2, Dlx5, Hesx1, and Six3 (supplemental Fig. 4, A–D′) between E7.5 and E8.25, and Fgf8 was normally induced at the mutant anterior neural ridge (ANR), prospective rostral patterning center, at E8.25 (supplemental Fig. 4, E and E′) indicating that forebrain specification was normally initiated in the mutants.

At E8.75 (8–10 ss) the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants were phenotypically normal. The rates of cell proliferation and cell death were similar in the forebrain and surrounding tissues of E8.75 mutant and wild-type littermates (Fig. 4, A and A′ and supplemental Fig. 5, A and B). Fgf8 was maintained in the mutant ANR (Fig. 4, B and B′) and Foxg1 expression similarly marked the mutant ANR and neuroectoderm (Fig. 4, C and C′ and supplemental Fig. 5, C–D′). The expression of the BMP antagonist-encoding Noggin and of Bmp7 was unaffected in the mutant axial mesendoderm (Fig. 4, D and D′ and supplemental Fig. 5, E and E′). Bmp4 was not ectopically expressed in the mutants (supplemental Fig. 5, F and F′). Wnt1 and Wnt8b were normally distributed in the presumptive diencephalon and midbrain (Fig. 4, E–F′). Shh was unaffected in the mutant neuroectoderm and axial mesendoderm (supplemental Fig. 5, G and G′), and Gli1, whose transcription is absolutely dependent on Shh signaling, was normally expressed in the mutant ventral forebrain (supplemental Fig. 5, H and H′). Six3, a repressor of Wnt1 and Wnt8b (34, 35) and an activator of Shh, appropriately marked the developing mutant ventral forebrain and eyes (supplemental Fig. 5, I and I′). Finally, the early CNCC and ectodermal markers Tfap2α, Msx1, Dlx5, and Dlx2 were normally distributed at the dorsal neural folds of the mid- and hindbrain and in the cephalic ectoderm (Fig. 4, G–H′ and supplemental Fig. 5, J–K′). Noggin was also normally detected along the dorsal neural folds and in the lateral cephalic mesenchyme of the mutants (Fig. 4, I and I′). Thus, overall forebrain regionalization and CNCC generation are normal in E8.75 CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants.

FIGURE 4.

Normal forebrain regionalization and impaired MAPK signaling in E8.75 CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutant heads. A and A′, representative lateral views of E8.75 control and CubnSox2-Cre-KO embryos stained with Lysotracker (in red) and anti-phospho-histone H3 (in green). Dotted lines demarcate the forebrain region in confocal sections of an 8-ss control (A) and mutant (A′) embryo. Nuclei colored by Hoechst are shown in blue. B–I, representative whole-mount mRNA staining of control (B–I) and mutant (B′–I′) embryos at E8.75. B and B′, normal Fg8 expression in the ANR (arrow) and the isthmus (arrowhead). C and C′, Foxg1 is expressed in the anterior neural plate (arrow); it is reduced in the mutant pharyngeal region (arrowhead). D and D′, Noggin is normally detected in the rostral axial mesendoderm (arrowhead) and the rostrolateral ectoderm (arrow). E–F′, normal expression of Wnt1 in the developing midbrain (arrowheads in E and E′) and of Wnt8b in the developing caudal forebrain (arrow in F and F′). G–H′, dorsal views of control and mutant embryos at the level of the prospective midbrain (arrowhead) and hindbrain showing Tfap2a normally expressed in the dorsal neural folds (G and G′) and Msx1 in the dorsal neural folds and cephalic mesenchyme (H and H′). I and I′, Noggin is similarly found in a lateral strip of cells between the rostral-most cephalic mesenchyme and the border of the rhombencephalon (r2–r3). Frontal views (B–D′); lateral views with the anterior to the left (E–F′ and I and I′). J, immunoblot analysis of cephalic extracts for phospho-Smad2, phospho-Smad1/5/8, phospho-Smad1Linker, total Smad1, phospho-β-catenin, and β-catenin. GAPDH is used as loading control. K, phospho-ERK1/2 is decreased, and phospho-Akt is maintained. The levels of endogenous total ERK and Akt are shown for comparison. The levels of FgfR1, FgfR2c, and Fgfr3c are normal in the mutants. Scale bars, A, 30 μm; B–D, 100 μm; E, H, and I, 6 μm; F and G, 40 μm.

MAPK/ERK Signaling Appears to be Deficient in E8.75 CubnSox2-Cre-KO Mutants

To understand why, despite normal neuroepithelial and neural crest marker expression at E8.75, increased apoptosis and perturbed CNCC distribution were evidenced half a day later in the mutants, we investigated whether the main signaling pathways involved in anterior cell survival, early forebrain regionalization, and global head morphogenesis were active (36–38). We analyzed the phosphorylation of the known Tgf-β/BMP, Wnt, and Fgf signaling effectors in anterior cephalic extracts of E8.75-E9.0 control and mutant embryos. Similar expression levels of phospho-Smad1/5/8 and phospho-Smad2 suggested that the intensity of Tgf-β/BMP activity was unaffected in the mutants (Fig. 4J). Wnt signaling-dependent GSK3 and Fgf/MAPK/ERK activities modulate the duration of the Bmp signal by catalyzing phosphorylation of Smad1 in the linker region, predominantly at Ser-206 (39, 40). We could not detect Smad1 phosphorylated at Ser-206 in the mutants (Fig. 4J). As suggested by the similar levels of β-catenin and phosphorylated β-catenin in control and mutant extracts (Fig. 4J), this was not due to modified Wnt and presumably GSK3 activity. We therefore analyzed the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 that mediates intracellular responses downstream to Fgf/FgfR signaling in the anterior head (41, 42) and triggers linker phosphorylation of Smad1 (39). The levels of ERK1/2 were clearly decreased in the mutant extracts (Fig. 4K) suggesting decreased Fgf activity. However, the unaltered levels of phospho-Akt, another Fgf effector in the anterior head (Fig. 4K), and of FgfR1–3 indicated that Fgf signaling was at least partly operating in the mutants, a finding consistent with the normal forebrain patterning. Taken together, these results support the idea that in E8.75–9.0 CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants the pro-survival Fgf signals may be not efficient enough to limit the duration of the pro-apoptotic Bmp activity, eventually contributing to increased anterior cell death and head hypoplasia.

High Affinity Binding of Fgf8 to Cubn Leads to Efficient ERK1/2 and Smad1 Linker Phosphorylation

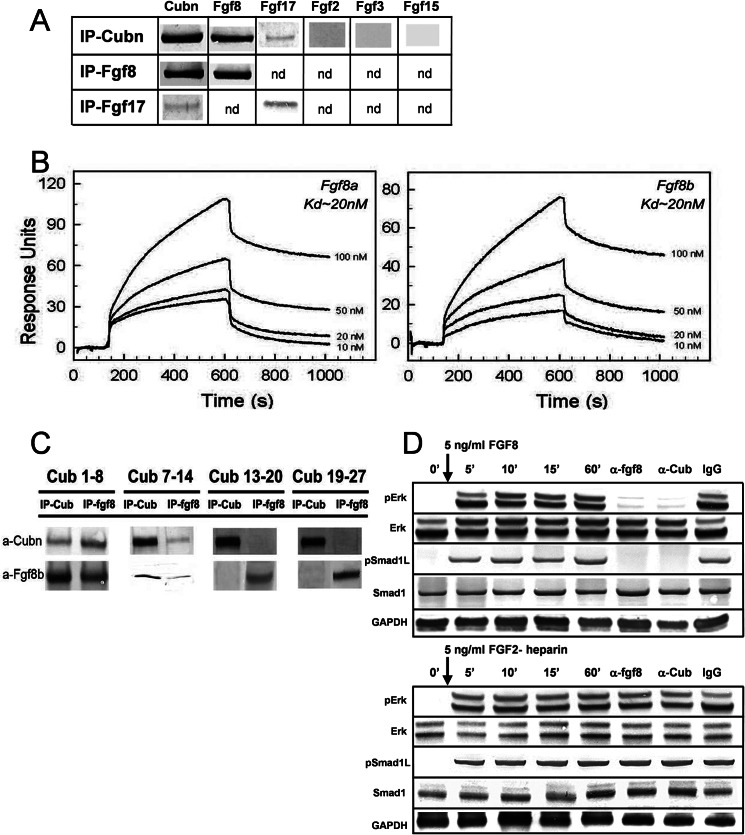

To understand how Cubn may affect the Fgf signaling pathway, we sought for potential interactions between Cubn and Fgf8, the best studied Fgf ligand during head morphogenesis. Fgf8 as well as the Fgf8 subfamily member, the structurally similar Fgf17 (43), were co-immunoprecipitated with Cubn in anterior cephalic extracts of wild-type E8.75–9.0 embryos (Fig. 5A). Structurally distinct Fgfs, including Fgf2 and the ANR-produced Fgf3 and Fgf15, were not co-immunoprecipitated with Cubn. Similarly, neither Wnt1, Wnt8b, Wnt3, Bmp7, nor Noggin were detected in the immunoprecipitates (supplemental Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 5.

Cubn binds Fgf8 with high affinity and contributes to Fgf8 signaling in vitro. A, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of Fgf8 and the structurally similar Fgf17 with Cubn; Fgf2, Fgf3, or Fgf15 do not interact with Cubn. B, SPR analysis on immobilized Cubn. Fgf8a and Fgf8b bind with equally high affinity to Cubn. C, immunoprecipitation of the “mini-proteins” CUB1–8, -7–14, -13–20, and -19–27 preincubated with recombinant Fgf8b without heparin and with anti-Fgf8b and anti-Cubn antibodies. Fgf8b preferentially co-immunoprecipitates with CUB1–8 and CUB7–14. D, incubation of serum-deprived BN/MSV cells with either 5 ng/ml of recombinant Fgf8b without heparin or recombinant Fgf2-heparin results in similar phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Smad1Linker. Anti-Cubn antibodies or anti-Fgf8b antibodies block the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Smad1Linker specifically in Fgf8b-treated cells. Control IgG has no effect. Endogenous Smad1 and ERK1/2 levels are shown for comparison, and GAPDH is used as loading control.

Further SPR analysis showed that recombinant mouse Fgf8a and Fgf8b, the two biologically active Fgf8 isomorphs (44, 45), bound in a Ca2+-dependent manner and with equally high affinity to a purified Cubn chip (Fig. 5B). The dissociation constant (Kd) was calculated to 20 nm, a value orders of magnitudes higher than those reported for binding of Fgf8b and Fgf8a to their established receptors (Kd values of ∼126–492 and 1–2.5 mm, respectively) (45). The equally high affinity of Fgf8a, the shorter Fgf8 isoform, and Fgf8b for Cubn indicated that the binding site of Fgf8 to Cubn was localized in the common core of the Fgf8 isoforms. Binding of Fgf8a or Fgf8b to Cubn was neither enhanced nor inhibited by recombinant FgfR1 or FgfR2 (supplemental Fig. 6B) indicating the following: (i) that the binding sites of Fgf8 to Cubn and to FgfRs are distinct; (ii) that FgfRs and Cubn do not directly interact, and (iii) that Cubn, Fgf8, and FgfRs do not form ternary complexes. Fgf8b did not bind to a control chip with the molecular partner of Cubn, Lrp2 (14). A very low affinity in the micromolar range was recorded for recombinant mouse Bmp7, which interacted also with the control Lrp2 chip.

To further characterize the interaction between Cubn and Fgf8, we incubated Fgf8b with overlapping recombinant Cubn constructs encoding the CUB domains 1–8, 7–14, 13–20, and 19–27 (20). Immunoprecipitation with Sepharose-bound anti-Cubn and anti-Fgf8b antibodies identified CUB domains 1–8 and 7–14 as the ones to be most likely involved in the interaction with Fgf8b (Fig. 5C).

To distinguish between FgfR-mediated and Cubn-assisted internalization of Fgf8 and to verify that internalization of Cubn-bound Fgf8 results in the phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 and Smad1 linker, we incubated Cubn expressing BN/MSV cells (46) with recombinant Fgf8b for 5 min without the addition of heparin, a component required for Fgf ligand binding to FgfRs (47). As a control of Cubn-independent FgfR activation, we in parallel incubated BN/MSV cells with recombinant heparin-bound Fgf2. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Smad1 linker was first detectable 5 min after addition of Fgf8b or Fgf2-heparin and was sustained over the time of the experiment, i.e. 60 min (Fig. 5D). In Fg8b-treated cells, endocytosis blocking anti-Cubn antibodies (18) or bioactivity neutralizing anti-Fgf8b antibodies (100 μg/ml) prevented the phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and Smad1 linker (Ser-206), whereas control IgG had no effect (Fig. 5D). In contrast, in Fgf2 heparin-treated cells, the phosphorylation of neither ERK1/2 nor Smad1 linker was modified by anti-Cubn antibodies. These results demonstrate that Fgf8 is a specific high affinity ligand of Cubn and that Cubn-assisted Fgf8 internalization results in Fgf8 signaling.

We then wondered whether Cubn and Fgf8 cooperate during head morphogenesis in vivo and whether Cubn expressed in the CNCCs is involved in the CNCC-Fgf8 cross-talk, a process critical for the formation of the cephalic vesicles (33, 48, 49). We failed to obtain mouse mutants lacking both Cubn and Fgf8 in the epiblast and to inactivate Cubn in the neural crest cells, including the rostral most CNCC population using mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the control of Wnt1 cis-regulatory elements. We therefore continued our study using frog and chick embryos.

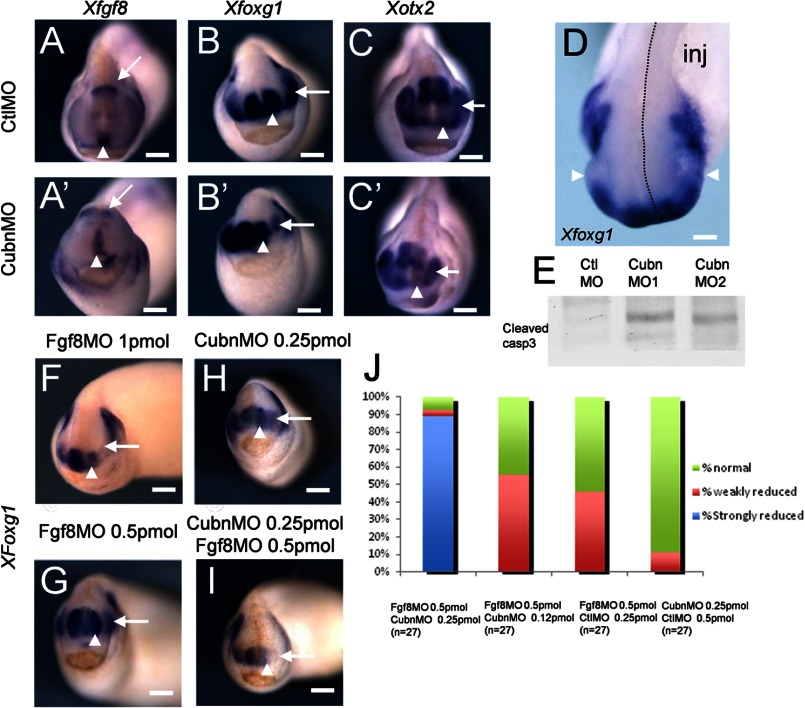

Synergistic Interplay between Cubn and Fgf8 during Head Formation

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that XCubn mRNA was enriched in the anterior neural plate region of neurula stage frog embryos, and this was confirmed at the protein level (supplemental Fig. 7, A and B). We selectively depleted Cubn in the left side of the head by microinjecting translation-blocking antisense morpholino nucleotides into the left dorso-animal blastomere of 8-cell stage embryos (supplemental Fig. 7C). The expression of XFgf8 in the ANR and the isthmus was maintained independently of the morpholino used (Fig. 6, A and A′). However, they both led to reduction of the expression domains of XFoxg1 (Fig. 6, B and B′) and XOtx2 (Fig. 6, C and C′) as well as to hypoplasia of the telencephalic and eye vesicles (Fig. 6D and supplemental Fig. 7D). Western blot analysis of treated embryos showed increased levels of activated caspase-3 (Fig. 6E) indicating that hypoplasia was accompanied by enhanced apoptosis.

FIGURE 6.

XCubn and XFgf8 are together necessary for normal head formation in the frog embryo. A–C′, representative whole-mount mRNA staining of tailbud stage frog embryos unilaterally injected with control (A–C) and MoCubn (A′–C′) morpholinos. A and A′, XFgf8 is expressed in the ANR (arrowhead) and the isthmus (arrow) of the MoCubn-treated embryos. B and B′, reduced XFoxg1 expression domain in the telencephalon (arrowhead) and eye (arrow) after MoCubn injection. C and C′, reduced expression domain of XOtx2 in the developing telencephalon (arrowhead), eye (arrow), and slightly in the midbrain of the MoCubn treated embryo. D, telencephalic and eye (arrowhead) hypoplasia and down-regulation of XFoxg1 mRNA staining in the injected part of the embryo (dotted line, inj). E, increased levels of cleaved caspase-3 in cephalic extracts of MoCubn-treated embryos. F, telencephalic hypoplasia and down-regulation of XFoxg1 in MoFgf8-injected embryos. G and H, low MoFgf8 (0.5 pmol) or MoCubn (0.25 pmol) concentrations do not affect telencephalic development and XFoxg1 expression. I, strong reduction of XFoxg1 in embryos co-injected with MoCubn and MoFgf8 at the same low concentrations. J, reduced or normal expression of XFoxg1 after co-injection of MoCubn and MoFgf8 at the concentrations indicated. The number of embryos analyzed is indicated. Scale bars, A–C, and F–I, 250 μm; D, 75 μm.

Forebrain hypoplasia and reduced XFoxg1 expression were as expected, also observed after depletion of XFgf8 (Fig. 6F). We next identified concentrations of XCubn and XFgf8 morpholinos, which did not modify telencephalic development and XFoxg1 expression when injected individually (Fig. 6, G and H). Combined, these morpholinos induced severe telencephalic hypoplasia and complete down-regulation of XFoxg1 in two independent experiments and in 24 out of 27 doubly injected embryos (Fig. 6, I and J, and supplemental Fig. 7E). These results support the idea that XCubn and XFgf8 act synergistically during head morphogenesis.

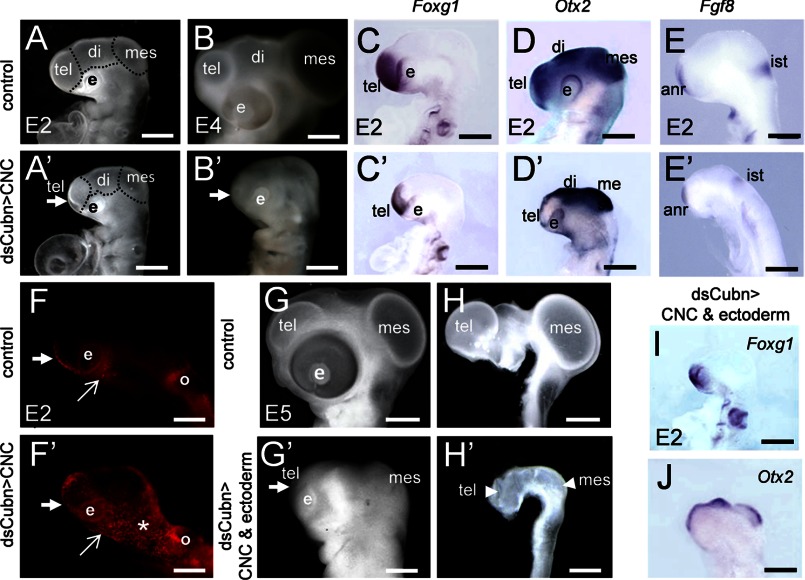

Cubn Is Required for CNCC Survival and Head Formation

In the chick embryo, before CNCC migration, at the 5 ss, Cubn is detectable at low levels in the cephalic ectoderm (CE) flanking the ANR region and in the neural folds at the level of the prospective fore-, mid-, and rostral hindbrain, i.e. the presumptive CNCC (supplemental Fig. 8, A and B). After neural tube closure and CNCC migration, Cubn remains restricted to the prospective anterior CE, rostroventral forebrain, and post-migratory CNCC (supplemental Fig. 8, C–E).

We silenced endogenous Cubn specifically in the cephalic neural folds or in both the cephalic neural folds and the anterior CE by electroporating dsCubn mRNA at the 5 ss, before the onset of CNCC migration. Twenty four hours later, i.e. at the 25 ss, and independently of the experimental design used, head morphogenesis was severely affected (Fig. 7, A–B′, and G–H′). Although the neural tube remained closed, the fore- and midbrain vesicles failed to expand, and the head volume was reduced by 42% in the treated embryos compared with the controls (n = 10). Despite the reduction of the expression domains of Foxg1 (Fig. 7, C, C′, and I) and Otx2 (Fig. 7, D, D′, and J) silencing of Cubn did not affect fore- or midbrain patterning, and Fgf8 was readily detected in the ANR and isthmus (Fig. 7, E and E′).

FIGURE 7.

Cubn expressed in the CNCC is critical for chick head formation. A–B′, electroporation of dsCubn in the premigratory CNCC leads to severe cephalic reduction (arrow points to the telencephalon) at E2 (A and A′) and E4 (B and B′). C–E′, representative whole-mount mRNA staining for Foxg1, Otx2, and Fgf8 in control (C–E) and dsCubn-treated (C′–E′) embryos. Silencing of Cubn in the CNCC leads to decreased Foxg1 (C and C′) and Otx2 (D and D′) expression domains in the telencephalon, whereas Fgf8 (E and E′) remains expressed in the ANR. F and F′, LysoTracker staining at ∼E1.5 shows enhanced cell death in the head at the level of the rostral forebrain (thick arrow), the lateral (asterisk), and the ventral cephalic mesenchyme (arrow) of a dsCubn-treated embryo. G–H′, silencing of Cubn in the premigratory CNCC and CE leads to severe cephalic hypoplasia at E5 (G and G′); the cephalic vesicles fail to expand normally (H and H′). I and J, representative whole-mount mRNA staining for Foxg1 (I) and Otx2 (J) after Cubn silencing in the CNCC and CE. Lateral views, anterior is to the left. di, diencephalons; e, eye; ist, isthmus; mes, mesencephalon; o, otic; tel, telencephalon. Scale bars, A, A′, C–E′, I, and J, 100 μm; B and B′, 600 μm; G–H′, 900 μm.

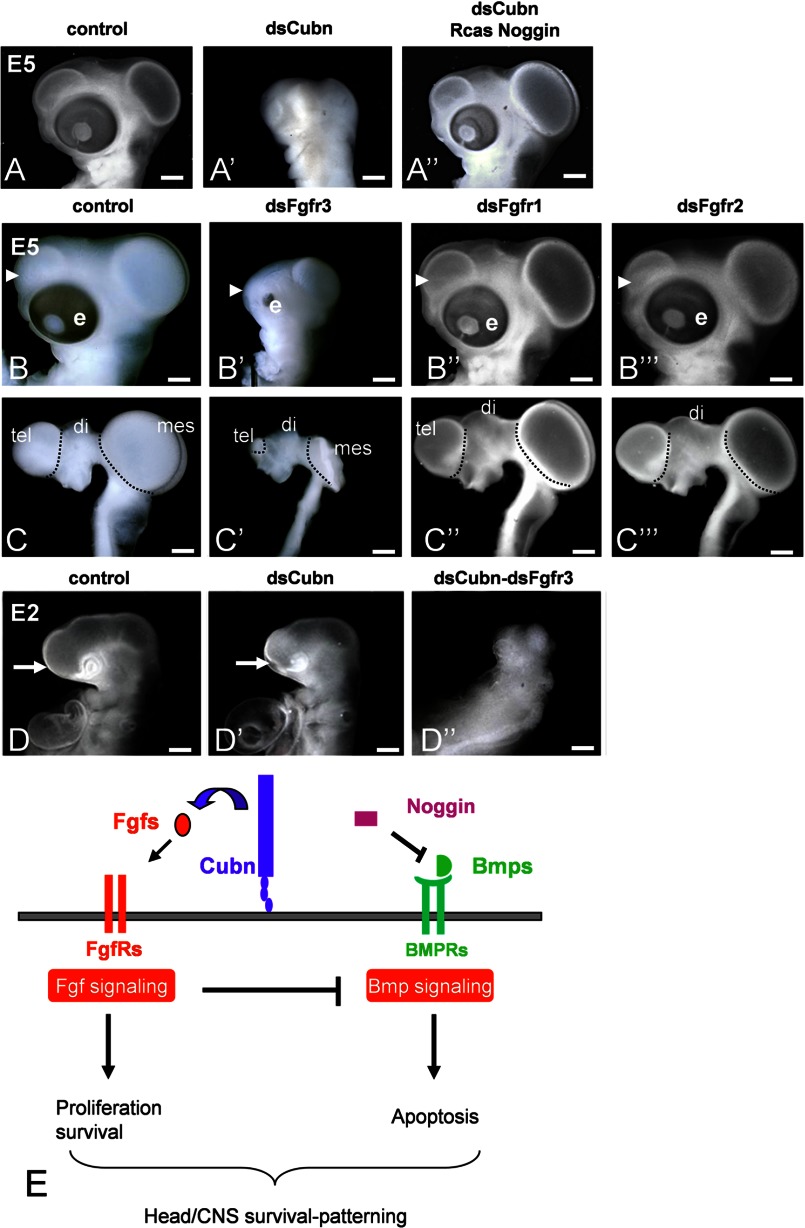

We noted that the decrease in head size correlated with extensive cell death, observed mainly in the cephalic mesenchyme a few hours after Cubn silencing, i.e. at the 18 ss (Fig. 7, F and F′). To verify that Cubn expressed in the migratory CNCCs functions, either directly or indirectly to regulate cell survival, we overexpressed the survival factor Noggin, a CNCC-produced factor known to potentiate Fgf8 signaling by counteracting Bmp activity (22), in the Cubn-depleted CNCCs. Overexpression of RCAS-Noggin in the CNCCs rescued the morphological defects and allowed normal fore- and midbrain formation (Fig. 8, A–A″). These results indicate that Cubn expressed in the migratory CNCCs is necessary for cell survival most likely by regulating CNCC response to Fgf8 signals.

FIGURE 8.

Cubn promotes Fgf signaling in the chick CNCC and CE together with FgfR3. A–A″, overexpression of Noggin in the CNCC of dsCubn-treated embryos restores head morphology. B–C‴, representative gross (B–B‴) and brain (C–C‴) morphology of E5 embryos electroporated in the CNCC and CE with dsControl (B and C), dsFgfR3 (B′ and C′), dsFgfR1 (B″ and C″), and dsFgR2 (B‴ and C‴). Cephalic hypoplasia is observed exclusively in dsFgfR3-treated embryos (arrowhead points to the telencephalon). D–D″, extremely severe head hypoplasia in double dsCubn-dsFgfR3 electroporated embryos at E2 (D″) compared with dsCubn-treated embryos of the same stage (D′). E, proposed Cubn-Fgf8 interaction in the CNCC and CE. Cubn expressed at the plasma membrane binds extracellular Fgf8, favors its endocytosis (assisted by Lrp2 and/or a yet unknown partner), and increases its availability for FgfRs within the cell. Cubn-dependent FgfR activation together with Bmp antagonism, here via Noggin, is necessary to counter Bmp activity and promote CNCC and CE survival. Scale bars, A–C‴, 900 μm; D–D″, 100 μm.

We next sought to identify the FgfRs involved in Fgf8 signal reception in the CNCCs and document the potential interactions between Cubn and FgfRs in vivo. FgfR3, FgfR1, and to a lesser extent FgfR2 are expressed in the presumptive CNCCs and CE (50, 51) in a pattern similar to Cubn. Silencing of FgfR3 at the 5 ss resulted in fore-, midbrain, and facial hypoplasia (Fig. 8, B–C′), although less severe than the ones seen in dsCubn-treated embryos (Fig. 7, G–H′), whereas electroporation with dsFgfR1 or dsFgfR2 did not affect head development (Fig. 8, B″–C‴). We therefore further focused on FgfR3 and Cubn and depleted the CE and cephalic neural folds from both Cubn and FgfR3. This double Cubn-FgfR3 silencing aggravated the individual phenotypes and led to cephalic aplasia (Fig. 8, D–D″) and lethality the day following the electroporation. This set of results shows that in the chick embryo FgfR3 is critical for Fgf, including Fgf8, signaling in the head and provides evidence that Cubn acts synergistically with FgfR3 in the CNCC and CE to convey signals for anterior cell survival and head morphogenesis (Fig. 8E).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify a novel developmental role of embryonic Cubn in the vertebrate head. Ablation of embryonic Cubn leads to head hypoplasia that correlates with increased anterior cell death, abnormal distribution of migratory CNCCs, and decreased expression of phosphorylated ERK, events that may be explained by deficient Fgf signaling. High affinity binding of Fgf8 to Cubn leading to ERK phosphorylation as well as synergistic function between Cubn and Fgf8 in the anterior head and Cubn and FgfR3 in the migratory CNCC and CE support our conclusion that Cubn may act as an extracellular modulator of Fgf8 signaling during head morphogenesis.

Cubn Expressed in the Cephalic Neural Crest Is Necessary for Head Morphogenesis but Not Patterning

During the early somitic stages, murine Cubn is expressed in the forebrain and the cephalic neural folds. After neural tube closure, Cubn remains detectable in the neuroepithelium and in the cephalic mesenchyme but is excluded from the cephalic ectoderm. Partial co-localization with Tfap2α indicates that Cubn is expressed in the migratory CNCCs. At later developmental stages Cubn is also expressed in various tissues of endodermal and mesodermal origin (7).

The epiblast-specific inactivation of Cubn resulting in efficient ablation of embryonic Cubn shows that Cubn is critical for head morphogenesis but does not allow the unambiguous identification of the embryonic tissues at the origin of the head defects. Several lines of evidence indicate however that mesodermal and endodermal development are normal in CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants at least until E9.5 and that the cephalic hypoplasia is neither the consequence of a developmental arrest nor of a heart defect. (a) The induction and maintenance of the anterior and forebrain identity as evidenced by Otx2, Hesx1, Six3, and Fgf8 in situ hybridization are not modified in the mutants. (b) Somite and body axis formation and turning onset around the 8–10 somite stage occur normally. (c) At the same stage, the expression of Bmp7 in the mutant embryonic heart region is normal. (d) A normal beating heart lying posterior/ventral to the head is seen until E9.5. (e) PECAM-1 immunocytochemistry, which is routinely used to detail embryonic vasculature, clearly detects well developed blood vessels at the level of the forebrain at E9.5. It is thus unlikely that a cardiovascular system failure or a delayed growth may explain the cephalic hypoplasia of the mutants.

Combined, the results obtained in the mouse, frog, and chick embryos show that the head hypoplasia is not due to defective patterning indicating that Cubn is not absolutely required for this process. In the mouse embryo, the lack of Shh and Nkx2.1 specifically in the preoptic area is the only forebrain defect at E9.25. This defect previously described in Fgf8 hypomorphs (52) may be explained by deficient Fgf8 signal reception within the neuroepithelium of the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants and is unlikely to reflect a primary defect in Shh signaling. This is indicated by the normal expression of the Shh signaling readout Gli1 (53), as well as the unmodified expression of Shh itself and Six3 in the ventral forebrain of the mutants between E8.25 and E8.75.

To inactivate Cubn in the forebrain neuroepithelium or the cephalic neural crest selectively, we generated CubnFoxg1-Cre-KO and CubnWnt1-Cre-KO mutants. We have been unsuccessful to efficiently delete Cubn in both cases. Most likely due to protein stability, Cubn was detectable in the forebrain of CubnFoxg1-Cre-KO mutants until E10.5. Furthermore, Cubn remained detectable in the CNCC of the rostral most forebrain region of CubnWnt1-Cre-KO mutants. XCubn silencing in the anterior head of the frog embryo provided the first direct indication that Cubn was necessary for head morphogenesis. It is the use of the chick embryo that allowed us to clearly define that CNCC is the most important site of Cubn expression/function during head morphogenesis.

CNCC is considered as a signaling center critical for neural tube closure and normal cephalic vesicle formation (22, 33). In both mouse and chick, the cephalic neural crest has a double function; it responds to Fgf8 survival, proliferation, and migration signals and maintains Fgf8 expression and signaling from the ANR by secreting Bmp antagonists (31–33). Our results support the idea that Cubn is crucial for this cross-talk, in particular for the reception of the Fgf8 survival signals by the CNCCs. Indeed, enhanced cell death is observed in the cephalic mesenchyme but not the neuroepithelium of CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutant or dsCubn-treated embryos despite normal Fgf8 expression and presumably normal Bmp antagonism. Thus Cubn expressed in the CNCCs is a novel, essential, and conserved modulator of head morphogenesis in the developing vertebrate head.

Cubn and Fgf8 Counteract Pro-apoptotic Bmp Activity

Fine-tuning of the equilibrium between Bmp, Wnt, and Fgf pro- and anti-apoptotic activities depends on the phosphorylation of the main Bmp effector Smad1 (40). Bmps promote C-terminal phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8, which is required for Bmp signaling (40). This process is identical in E8.75 wild-type and CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutant embryos indicating that the intensity of the pro-apoptotic Bmp signal is not modified and that retinoic acid activity, which suppresses Bmp activity by promoting degradation of C-terminal phosphorylated Smad1 (54), is normal. On the anti-apoptotic side, Fgf/MAPK and GSK3 mediate two sequential phosphorylations of the Smad1 linker region, which limit the duration of the Bmp signal (39, 55). In E8.75 CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants, before any morphological abnormality can be seen, phosphorylation of Smad1 linker is undetectable indicating prolonged apoptotic activity. There is no evidence to link deficient Smad1 linker phosphorylation with deficient or increased Wnt activity because the expression levels of the Wnt targets β-catenin and phosphorylated β-catenin are normal. In contrast, the decreased levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 in the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants suggest decreased activity of the Fgf/MAPK/ERK pathway, which is normally required to prime the Smad1 linker for a second phosphorylation by Wnt activity-regulated GSK3 (39). Direct evidence for the involvement of Cubn in the Fgf8/ERK1/2 pathway comes from in vitro studies of Cubn-expressing BN/MSV cells. In this model, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is similarly induced by Fgf8b or by heparin-bound Fgf2. In contrast, anti-Cubn or anti-Fgf8b antibodies block selectively the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the phosphorylation of Smad1 linker promoted by Fgf8b. We propose that absence of Smad1 phosphorylated in the linker region in the CubnSox2-Cre-KO mutants is due to a not fully efficient Fgf signaling and to a subsequently prolonged Bmp signal duration. The rescue of the phenotype of dsCubn mRNA-treated chick embryos by the overexpression of the Bmp antagonist Noggin supports this conclusion and shows that Cubn is absolutely necessary in vivo for an efficient Fgf-Bmp cross-regulation.

Cubn, a Novel Fgf8 Receptor and FgfRs Cooperate for Anterior Head Survival

There is no evidence supporting a direct interaction between Cubn and members of the Wnt or Bmp pathways involved in anterior cell survival. Our results show that Cubn is a novel and specific receptor for Fgf8. Joint silencing of Cubn and Fgf8 in the early frog embryonic head aggravates the individual effects, and double Cubn and FgfR3 down-regulation in the chick CNCC and CE results in almost complete head truncation and embryonic death clearly indicating the interplay between Cubn, Fgf8, and FgfRs for anterior cell survival.

How this cooperation occurs at the cell level is not known. The subcellular distribution of FgfRs in vivo has not been reported extensively in the developing brain, but cell surface availability may be low (42). Gutin et al. (56) postulated the existence of extracellular and/or intracellular modulators that would impart specificity in Fgf responsiveness. In this context, Cubn, which binds to the core region of Fgf8 with high affinity, could “focus” members of the Fgf8 family to specific cell types, including the CNCC, and allow internalization of Fgf8 independently of FgfRs. Our data support this hypothesis; Cubn does not interact with FgfR1 or FgfR2 in vitro and presumably with other FgfR family members (57).

To behave as a distinct Fgf8 receptor, Cubn, which has no cytoplasmic domain, needs to interact with a transmembrane protein. Amn, a molecular partner of Cubn in the visceral endoderm and other absorptive epithelia, is hardly detectable in the neuroepithelium and not detectable in the CNCC. It is therefore unlikely that Amn is important for Cubn function in the anterior head. Supporting this hypothesis, Amn-deficient chimeras are viable (58). We propose that Lrp2, the other known endocytic partner of Cubn, expressed in the neuroepithelium and CNCC may at least partly facilitate endocytosis of Cubn-bound Fgf8. However, because the phenotype of the epiblast-specific Lrp2 mutants is milder (15) than that of Cubn mutants, it is likely that Cubn interacts with additional yet not identified transmembrane proteins in the developing head.

Finally, polymorphisms in CUBN were proposed to be risk factors for neural tube closure defects (5, 6). We cannot exclude that this type of defects may be due to inadequate B12 levels in the mother or the fetus. However, neural tube closure defects are not associated with the selective vitamin B12 malabsorption Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome (23), and the maternal-to-fetal transport of vitamin B12 does not involve CUBN. Neural tube closure was not modified after selective Cubn ablation in the animal models and at the stages analyzed here. However, somite and body axis formation is severely perturbed in Cubn null mice (8). In view of our data, it is tempting to propose that the above polymorphisms may selectively modify the binding capacities of Cubn for Fgf8 family members during very early developmental stages affecting thereby Fgf8-responsive tissues involved in neural tube closure such as the mesoderm.

In conclusion, Cubn is a novel receptor for Fgf8 and most likely the Fgf8 subfamily members Fgf17 and Fgf18, necessary for efficient FgfR signaling and cell survival during early head morphogenesis at least in the mouse, frog, and chick embryos. We propose that Cubn may favor FgfR activation by increasing Fgf-ligand endocytosis/availability in all Cubn-expressing tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Le Bouffant and I. Buisson for quantitative RT-PCR studies; A. Brändli for XCubn plasmid; E. Lacy for anti-Amn antibody; S. Thomasseau and I. Anselme for technical assistance; A. Camus, F. Causeret, L. Bally-Cuif, U. Borelo, A. Pierani, and S. Schneider-Maunoury for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, and J. A. Sahel for constant support.

This work was supported in part by INSERM, CNRS, UPMC, EuReGene FP6 Grant GA5085; CNRS-ANR-BLAN-0153, CNRS-ANR-06-BLAN-0200, the GEFLUC-Paris Ile de France; the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Lundbeck Foundation.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–8.

- CNCC

- cephalic neural crest cell

- FgfR

- Fgf receptor

- nt

- nucleotide

- ss

- somite stage

- BN/MSV

- brown Norway rat/mouse sarcoma virus

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- ANR

- anterior neural ridge

- CE

- cephalic ectoderm.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kozyraki R., Gofflot F. (2007) Multiligand endocytosis and congenital defects: roles of cubilin, megalin, and amnionless. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 3038–3046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amsellem S., Gburek J., Hamard G., Nielsen R., Willnow T. E., Devuyst O., Nexo E., Verroust P. J., Christensen E. I., Kozyraki R. (2010) Cubilin is essential for albumin reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 1859–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kozyraki R., Cases O. (2013) Vitamin B12 absorption: Mammalian physiology and acquired and inherited disorders. Biochimie 95, 1002–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reznichenko A., Snieder H., van den Born J., de Borst M. H., Damman J., van Dijk M. C., van Goor H., Hepkema B. G., Hillebrands J.-L., Leuvenink H. G., Niesing J., Bakker S. J., Seelen M., Navis G., and REGaTTA (REnal GeneTics TrAnsplantation) Groningen Group (2012) CUBN as a novel locus for end-stage renal disease: insights from renal transplantation. PLoS ONE 7, e36512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franke B., Vermeulen S. H., Steegers-Theunissen R. P., Coenen M. J., Schijvenaars M. M., Scheffer H., den Heijer M., Blom H. J. (2009) An association study of 45 folate-related genes in spina bifida: Involvement of cubilin (CUBN) and tRNA aspartic acid methyltransferase 1 (TRDMT1). Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 85, 216–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pangilinan F., Molloy A. M., Mills J. L., Troendle J. F., Parle-McDermott A., Signore C., O'Leary V. B., Chines P., Seay J. M., Geiler-Samerotte K., Mitchell A., VanderMeer J. E., Krebs K. M., Sanchez A., Cornman-Homonoff J., Stone N., Conley M., Kirke P. N., Shane B., Scott J. M., Brody L. C. (2012) Evaluation of common genetic variants in 82 candidate genes as risk factors for neural tube defects. BMC Med. Genet. 13, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Assémat E., Châtelet F., Chandellier J., Commo F., Cases O., Verroust P., Kozyraki R. (2005) Overlapping expression patterns of the multiligand endocytic receptors cubilin and megalin in the CNS, sensory organs and developing epithelia of the rodent embryo. Gene Expr. Patterns 6, 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith B. T., Mussell J. C., Fleming P. A., Barth J. L., Spyropoulos D. D., Cooley M. A., Drake C. J., Argraves W. S. (2006) Targeted disruption of cubilin reveals essential developmental roles in the structure and function of endoderm and in somite formation. BMC Dev. Biol. 6, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Assémat E., Vinot S., Gofflot F., Linsel-Nitschke P., Illien F., Châtelet F., Verroust P., Louvet-Vallée S., Rinninger F., Kozyraki R. (2005) Expression and role of cubilin in the internalization of nutrients during the peri-implantation development of the rodent embryo. Biol. Reprod. 72, 1079–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hammad S. M., Stefansson S., Twal W. O., Drake C. J., Fleming P., Remaley A., Brewer H. B., Jr., Argraves W. S. (1999) Cubilin, the endocytic receptor for intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 complex, mediates high density lipoprotein holoparticle endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10158–10163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moestrup S. K., Kozyraki R., Kristiansen M., Kaysen J. H., Rasmussen H. H., Brault D., Pontillon F., Goda F. O., Christensen E. I., Hammond T. G., Verroust P. J. (1998) The intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor and target of teratogenic antibodies is a megalin-binding peripheral membrane protein with homology to developmental proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5235–5242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barth J. L., Argraves W. S. (2001) Cubilin and megalin: partners in lipoprotein and vitamin metabolism. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fyfe J. C., Madsen M., Højrup P., Christensen E. I., Tanner S. M., de la Chapelle A., He Q., Moestrup S. K. (2004) The functional cobalamin (vitamin B12)-intrinsic factor receptor is a novel complex of cubilin and amnionless. Blood 103, 1573–1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christ A., Christa A., Kur E., Lioubinski O., Bachmann S., Willnow T. E., Hammes A. (2012) LRP2 is an auxiliary SHH receptor required to condition the forebrain ventral midline for inductive signals. Dev. Cell 22, 268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spoelgen R., Hammes A., Anzenberger U., Zechner D., Andersen O. M., Jerchow B., Willnow T. E. (2005) LRP2/megalin is required for patterning of the ventral telencephalon. Development 132, 405–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kozyraki R., Fyfe J., Verroust P. J., Jacobsen C., Dautry-Varsat A., Gburek J., Willnow T. E., Christensen E. I., Moestrup S. K. (2001) Megalin-dependent cubilin-mediated endocytosis is a major pathway for the apical uptake of transferrin in polarized epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12491–12496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zucker R. M., Hunter S., Rogers J. M. (1998) Confocal laser scanning microscopy of apoptosis in organogenesis-stage mouse embryos. Cytometry 33, 348–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Panse S., Galceran M., Pontillon F., Lelongt B., van de Putte M., Ronco P. M., Verroust P. J. (1995) Immunofunctional properties of a yolk sac epithelial cell line expressing two proteins gp280 and gp330 of the intermicrovillar area of proximal tubule cells: inhibition of endocytosis by the specific antibodies. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 67, 120–129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colas A., Cartry J., Buisson I., Umbhauer M., Smith J. C., Riou J.-F. (2008) Mix. 1/2-dependent control of FGF availability during gastrulation is essential for pronephros development in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 320, 351–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kristiansen M., Kozyraki R., Jacobsen C., Nexø E., Verroust P. J., Moestrup S. K. (1999) Molecular dissection of the intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor, cubilin, discloses regions important for membrane association and ligand binding. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20540–20544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nykjaer A., Lee R., Teng K. K., Jansen P., Madsen P., Nielsen M. S., Jacobsen C., Kliemannel M., Schwarz E., Willnow T. E., Hempstead B. L., Petersen C. M. (2004) Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature 427, 843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Creuzet S. E. (2009) Regulation of pre-otic brain development by the cephalic neural crest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15774–15779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gräsbeck R. (2006) Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome (selective vitamin B12 malabsorption with proteinuria). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 1, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hayashi S., Lewis P., Pevny L., McMahon A. P. (2002) Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Gene Expr. Patterns 2, 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paek H., Gutin G., Hébert J. M. (2009) FGF signaling is strictly required to maintain early telencephalic precursor cell survival. Development 136, 2457–2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson R. M., Stottmann R. W., Choi M., Klingensmith J. (2006) Endogenous bone morphogenetic protein antagonists regulate mammalian neural crest generation and survival. Dev. Dyn. 235, 2507–2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohkubo Y., Chiang C., Rubenstein J. L. (2002) Coordinate regulation and synergistic actions of BMP4, SHH, and FGF8 in the rostral prosencephalon regulate morphogenesis of the telencephalic and optic vesicles. Neuroscience 111, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mason I. (2007) Initiation to end point: the multiple roles of fibroblast growth factors in neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 583–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geng X., Oliver G. (2009) Pathogenesis of holoprosencephaly. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1403–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hébert J. M., Fishell G. (2008) The genetics of early telencephalon patterning: some assembly required. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 678–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoch R. V., Rubenstein J. L., Pleasure S. (2009) Genes and signaling events that establish regional patterning of the mammalian forebrain. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 378–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klingensmith J., Matsui M., Yang Y.-P., Anderson R. M. (2010) Roles of bone morphogenetic protein signaling and its antagonism in holoprosencephaly. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 154C, 43–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le Douarin N. M., Couly G., Creuzet S. E. (2012) The neural crest is a powerful regulator of pre-otic brain development. Dev. Biol. 366, 74–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Geng X., Speirs C., Lagutin O., Inbal A., Liu W., Solnica-Krezel L., Jeong Y., Epstein D. J., Oliver G. (2008) Haploinsufficiency of Six3 fails to activate Sonic hedgehog expression in the ventral forebrain and causes holoprosencephaly. Dev. Cell 15, 236–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu W., Lagutin O., Swindell E., Jamrich M., Oliver G. (2010) Neuroretina specification in mouse embryos requires Six3-mediated suppression of Wnt8b in the anterior neural plate. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3568–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Itasaki N., Hoppler S. (2010) Cross-talk between Wnt and bone morphogenic protein signaling: a turbulent relationship. Dev. Dyn. 239, 16–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eswarakumar V. P., Lax I., Schlessinger J. (2005) Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Turner N., Grose R. (2010) Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 116–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sapkota G., Alarcón C., Spagnoli F. M., Brivanlou A. H., Massagué J. (2007) Balancing BMP signaling through integrated inputs into the Smad1 linker. Mol. Cell 25, 441–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eivers E., Demagny H., De Robertis E. M. (2009) Integration of BMP and Wnt signaling via vertebrate Smad1/5/8 and Drosophila Mad. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 20, 357–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shinya M., Koshida S., Sawada A., Kuroiwa A., Takeda H. (2001) Fgf signalling through MAPK cascade is required for development of the subpallial telencephalon in zebrafish embryos. Development 128, 4153–4164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Regad T., Roth M., Bredenkamp N., Illing N., Papalopulu N. (2007) The neural progenitor-specifying activity of FoxG1 is antagonistically regulated by CKI and FGF. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 531–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guillemot F., Zimmer C. (2011) From cradle to grave: the multiple roles of fibroblast growth factors in neural development. Neuron 71, 574–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guo Q., Li K., Sunmonu N. A., Li J. Y. (2010) Fgf8b-containing spliceforms, but not Fgf8a, are essential for Fgf8 function during development of the midbrain and cerebellum. Dev. Biol. 338, 183–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Olsen S. K., Li J. Y., Bromleigh C., Eliseenkova A. V., Ibrahimi O. A., Lao Z., Zhang F., Linhardt R. J., Joyner A. L., Mohammadi M. (2006) Structural basis by which alternative splicing modulates the organizer activity of FGF8 in the brain. Genes Dev. 20, 185–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nykjaer A., Fyfe J. C., Kozyraki R., Leheste J. R., Jacobsen C., Nielsen M. S., Verroust P. J., Aminoff M., de la Chapelle A., Moestrup S. K., Ray R., Gliemann J., Willnow T. E., Christensen E. I. (2001) Cubilin dysfunction causes abnormal metabolism of the steroid hormone 25(OH) vitamin D3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13895–13900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mohammadi M., Olsen S. K., Goetz R. (2005) A protein canyon in the FGF-FGF receptor dimer selects from an à la carte menu of heparan sulfate motifs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 506–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Creuzet S. E., Martinez S., Le Douarin N. M. (2006) The cephalic neural crest exerts a critical effect on forebrain and midbrain development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14033–14038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Creuzet S., Schuler B., Couly G., Le Douarin N. M. (2004) Reciprocal relationships between Fgf8 and neural crest cells in facial and forebrain development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4843–4847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lunn J. S., Fishwick K. J., Halley P. A., Storey K. G. (2007) A spatial and temporal map of FGF/Erk1/2 activity and response repertoires in the early chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 302, 536–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Walshe J., Mason I. (2000) Expression of FGFR1, FGFR2 and FGFR3 during early neural development in the chick embryo. Mech. Dev. 90, 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Storm E. E., Garel S., Borello U., Hebert J. M., Martinez S., McConnell S. K., Martin G. R., Rubenstein J. L. (2006) Dose-dependent functions of Fgf8 in regulating telencephalic patterning centers. Development 133, 1831–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bai C. B., Auerbach W., Lee J. S., Stephen D., Joyner A. L. (2002) Gli2, but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway. Development 129, 4753–4761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sheng N., Xie Z., Wang C., Bai G., Zhang K., Zhu Q., Song J., Guillemot F., Chen Y.-G., Lin A., Jing N. (2010) Retinoic acid regulates bone morphogenic protein signal duration by promoting the degradation of phosphorylated Smad1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18886–18891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fuentealba L. C., Eivers E., Ikeda A., Hurtado C., Kuroda H., Pera E. M., De Robertis E. M. (2007) Integrating patterning signals: Wnt/GSK3 regulates the duration of the BMP/Smad1 signal. Cell 131, 980–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gutin G., Fernandes M., Palazzolo L., Paek H., Yu K., Ornitz D. M., McConnell S. K., Hébert J. M. (2006) FGF signalling generates ventral telencephalic cells independently of SHH. Development 133, 2937–2946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Olsen S. K., Ibrahimi O. A., Raucci A., Zhang F., Eliseenkova A. V., Yayon A., Basilico C., Linhardt R. J., Schlessinger J., Mohammadi M. (2004) Insights into the molecular basis for fibroblast growth factor receptor autoinhibition and ligand-binding promiscuity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 935–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tomihara-Newberger C., Haub O., Lee H. G., Soares V., Manova K., Lacy E. (1998) The amn gene product is required in extraembryonic tissues for the generation of middle primitive streak derivatives. Dev. Biol. 204, 34–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]