Abstract

Mammalian hearing relies upon active cochlear mechanics, which arises from outer hair cell (OHC) electromotility and hair bundle movement, to amplify acoustic stimulations increasing hearing sensitivity and frequency selectivity. Here we describe the novel finding that gap junctions between cochlear supporting cells also have a critical role in active cochlear amplification in vivo. We find that targeted-deletion of connexin26 (Cx26) in Deiters cells (DCs) and outer pillar cells (OPCs), which constrain OHCs standing on the basilar membrane, causes a leftward shift in OHC electromotility towards hyperpolarization, and reduces active cochlear amplification with hearing loss. Coincident with large reduction in distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) and severe hearing loss at high frequencies, the shift is larger in shorter OHCs. Our study demonstrates that active cochlear amplification in vivo is dependent on supporting cell gap junctions. These new findings also show that Cx26 deficiency can reduce active cochlear amplification to induce hearing loss.

Keywords: gap junction, connexin26, outer hair cell electromotility, hearing, cochlea, deafness

Introduction

Mammalian hearing function relies upon active cochlear amplification amplifying the basilar membrane (BM) vibration to acoustic stimulation increasing hearing sensitivity and frequency selectivity [1–2]. Outer hair cell (OHC) electromotility is an active cochlear amplifier in mammals [3–6]. Deficiency of OHC electromotility can induce hearing loss [7]. In situ, OHCs are constrained by phalangeal processes of Deiters cells (DCs) and pillar cells (PCs). They contain rigid bundles of microtubules and actin microfilaments along their phalangeal processes acting as a scaffold supporting OHCs standing between the BM and the reticular lamina (RL) [8–9]. This rigid scaffold also transfers forces between the BM and the RL and provides an appropriate mechanical load to the OHCs to maintain OHC electromotility at an optimal operating point.

It has been found that the phalangeal processes of DCs can alter their curvature in responses to electrical and chemical stimulations [10–12]. However, DCs do not have OHC-like electromotility. DCs and PCs including their phalangeal processes are well-coupled by gap junctions but hair cells have neither gap junctions nor connexin expression [6, 13–15]. There is also no direct electrical conductance between DCs and OHCs [15–16]. We previously found that electrical and mechanical stimulations in DCs or alternation of gap junctions between DCs can affect OHC electromotility in the in vitro preparation [16]. However, it remains unclear whether supporting cell gap junctions in vivo can also alter active cochlear mechanics to influence hearing.

Connexin 26 (Cx26, GJB2) is a predominant gap junction isoform in the cochlea [13, 14,17]. In this study, we selectively deleted Cx26 expression in DCs and outer pillar cells (OPCs), which directly constrain OHCs standing on the BM. We found that targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs left-shifted OHC electromotility and reduced active cochlear mechanics with hearing loss. These data demonstrate that Cx26 expression in supporting cells plays a critical role in active cochlear amplification in vivo. In the clinic, Cx26 mutations produce a high incidence of hearing loss and are responsible for ~50% of nonsyndromic hearing loss [18–20]. We recently found that cell degeneration is not a primary cause for deafness due to Cx26 deficiency [21]. These new findings also reveal a new mechanism for Cx26 deficiency associated hearing loss.

Results

Targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs in the cochlea

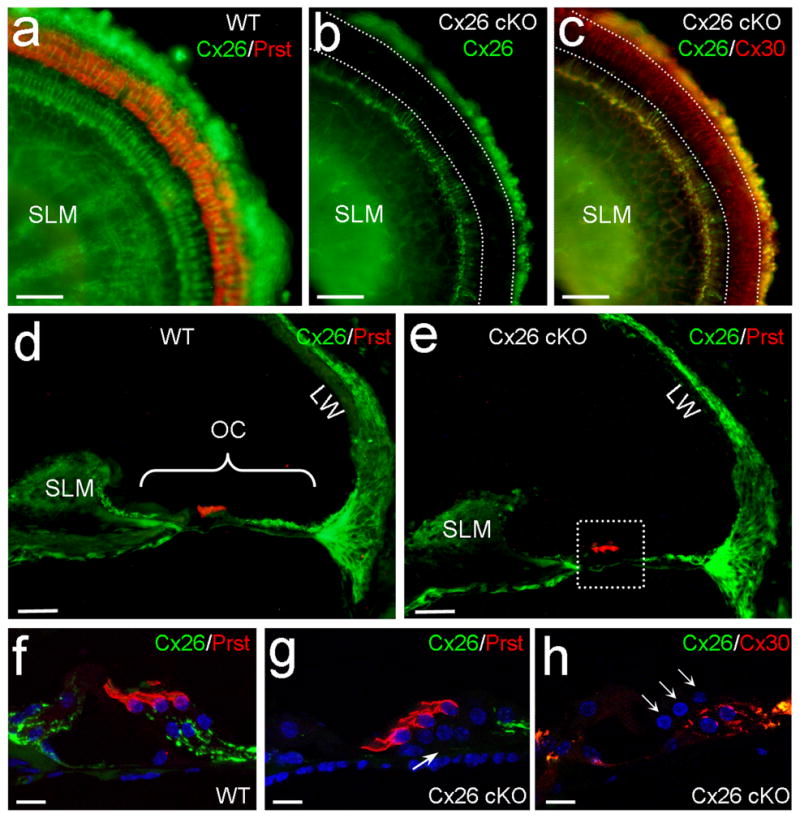

We used loxP-Cre technique to delete Cx26 expression in DCs and OPCs. The Cx26 conditional knockout (cKO) mouse was generated by crossing Cx26loxP/loxP transgenic mice [22] with a Prox1-CreERT2 mouse line, which a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase is driven by a homeodomain transcription factor Prox1 [23]. Prox1 is specifically expressed in DCs and OPCs in the cochlea after E18 and remains in these cells after birth [24–26]. Consistent with Cre expression [26], Cx26 labeling in DCs and OPCs was absent in Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2). Cx26 labeling in the inner layer of Hensen cells was also reduced but not absent (Fig. 1b–c, g–h). The deletion is uniform at apical, middle, and basal turns (Supplementary Fig. S1). Cx26 labeling in other cochlear structures including the spiral limbus (SLM) and the lateral wall was intense and normal (Figs. 1a–e and Supplementary Fig. S2). Cx30 is another predominant gap junction isoform expressed in the cochlea [14, 15]. Cx30 expression also appeared normal in Cx26 cKO mice. Intense-labeling for Cx30 in DCs and OPCs is visible (Figs. 1c&h and Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, the cochlea appeared normal development in Cx26 cKO mice (Figs. 1e and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Targeted deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs in Cx26 cKO mice. a–c:Immunofluorescent labeling of the cochlear sensory epithelium for Cx26, Prestin, and Cx30 in the whole-mounting preparation. White-dashed lines represent OHC, DC and OPC area, where Cx26 labeling (green) is absent but Cx30 labeling (red color in panel c) remains in Cx26 cKO mice. d,e: Immunofluorescent staining of the cochlear cross-section for Cx26. OHCs are visualized by prestin labeling (red color). A white-dashed line box in panel e indicates OHCs, DCs, OPCs, and their neighboring area. OC: organ of Corti; LW: lateral wall; SLM: spiral limbus. f–h: High-magnification images of the boxed area. A white arrow in panel g indicates that the Cx26 labeling in the DC and OPC region is absent in Cx26 cKO mice. Three white arrows in panel h indicate 3 rows of OHCs. Scale bars = 50 μm in a–e; 10 μm in f–h.

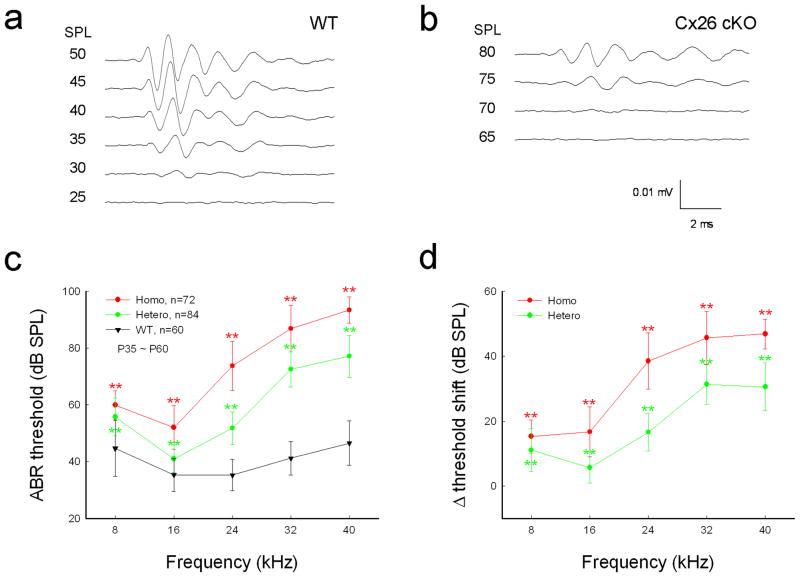

Elevation of auditory brainstem response threshold

The Cx26 cKO mice had hearing loss (Fig. 2). The ABR threshold in homozygous Cx26 cKO mice was increased significantly. The thresholds at 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40 kHz were 59.9±5.05, 52.0±7.67, 73.8±8.64, 86.9±8.16, and 93.4±4.58 dB SPL, respectively (Fig. 2c, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction). In comparison with WT littermates, the increase of ABR threshold in Cx26 cKO mice at 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40 kHz was 15.3±5.05, 16.7±7.67, 38.5±8.64, 45.7±8.16, and 46.9±4.58 dB SPL, respectively (Fig. 2d). The increase at high-frequencies was larger. The thresholds were elevated by 30–45 dB SPL at frequencies above 24 kHz. The ABR threshold was also increased in heterozygous Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 2c&d). However, the increases were less than those in homozygous mice. The ABR thresholds at 24, 32, and 40 kHz were 51.8±5.73, 72.5±6.18, and 77.1±7.35 dB SPL, respectively (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction). The threshold was increased by 15–30 dB at frequencies above 24 kHz (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Hearing loss in Cx26 cKO mice assessed by ABR recording. a,b: ABR waveforms recorded in Cx26 cKO and WT mice. The ABR was evoked by 24 kHz tone-bursts at postnatal day 45 (P45). c: Frequency-thresholds of ABR in homozygous and heterozygous Cx26 cKO mice and WT mice at P35–60. WT littermates served as a control group. d: Elevation of ABR thresholds in homozygous and heterozygous Cx26 cKO mice. Hearing loss is severe at high frequencies. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D; **: P < 0.001 as determined by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction

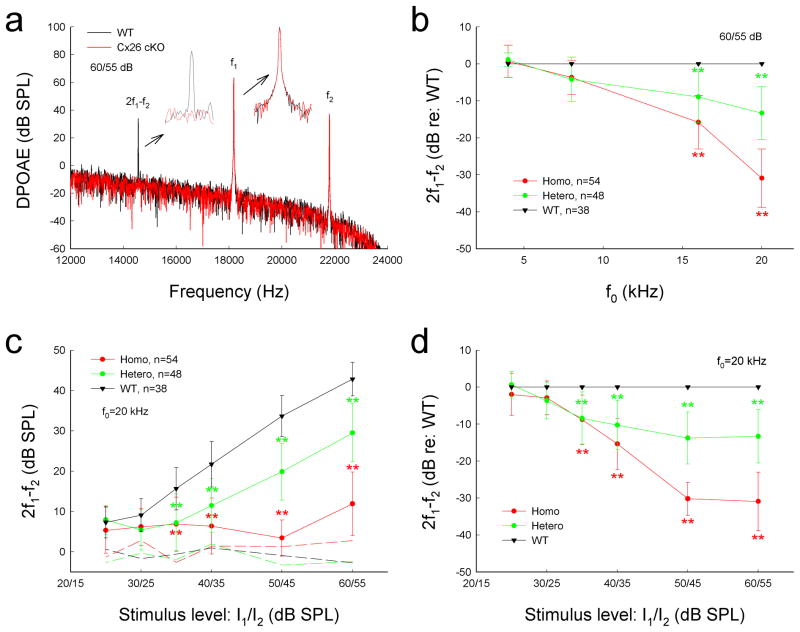

Reduction of distortion product otoacoustic emission

Figure 3 shows that targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs significantly reduced DPOAE, which reflects activity of active cochlear amplification in vivo. The distortion product of 2f1–f2 at f0 of 20 kHz was almost at the noise level and was 6.92±6.37, 4.47±3.43, and 11.9±7.89 dB SPL at the stimulus level of 40, 50, and 60 dB SPL, respectively (Fig. 3a&c). In comparison with WT littermates, the DPOAEs were reduced by 15.3±6.92, 30.2±4.47, and 30.9±7.89 dB at the stimulus level of 40, 50, and 60 dB SPL, respectively (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction). The decrease was larger at higher stimulus levels (Fig. 3d). The decrease was also larger at higher frequencies (Fig. 3b). The DPOAEs at 16 and 20 kHz were reduced by 15.8±7.23 and 30.9±7.89 dB, respectively (P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction). The DPOAE at 8 kHz in Cx26 cKO mice was also reduced by 3.69±4.61 dB. However, the decrease was not significant (P=0.13, one-way ANOVA). The DPOAE in heterozygous Cx26 cKO mice was also reduced (Fig. 3b–d). The decrease at the stimulus level of 50 and 60 dB SPL was about 10 dB SPL (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction), which was less than that in homozygous Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 3c&d). The decrease was also larger at high frequencies (Fig. 3b). The decrease at 16 and 20 kHz in the heterozygous mice was 8.95±7.01 and 13.3±7.19 dB, respectively (P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction).

Fig. 3.

Reduction of acoustic emission in Cx26 cKO mice. a: Spectrum of acoustic emission recorded from Cx26 cKO mice and WT mice. Insets: Large scale plotting of 2f1–f2 and f1 peaks. The peak of DPOAE (2f1–f2) in Cx26 cKO mice was reduced but f1 and f2 peaks remained the same as those in WT mice. f0=20 kHz. b: Reduction of DPOAE in Cx26 cKO mice in frequency responses. DPOAEs were normalized to the WT mice. c: Reduction of DPOAE in Cx26 cKO mice in I/O plot. Dashed lines represent the noise levels of recording. d: Normalized reduction of DPOAE in homozygous and heterozygous Cx26 cKO mice. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.; **: P < 0.001 as determined by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction.

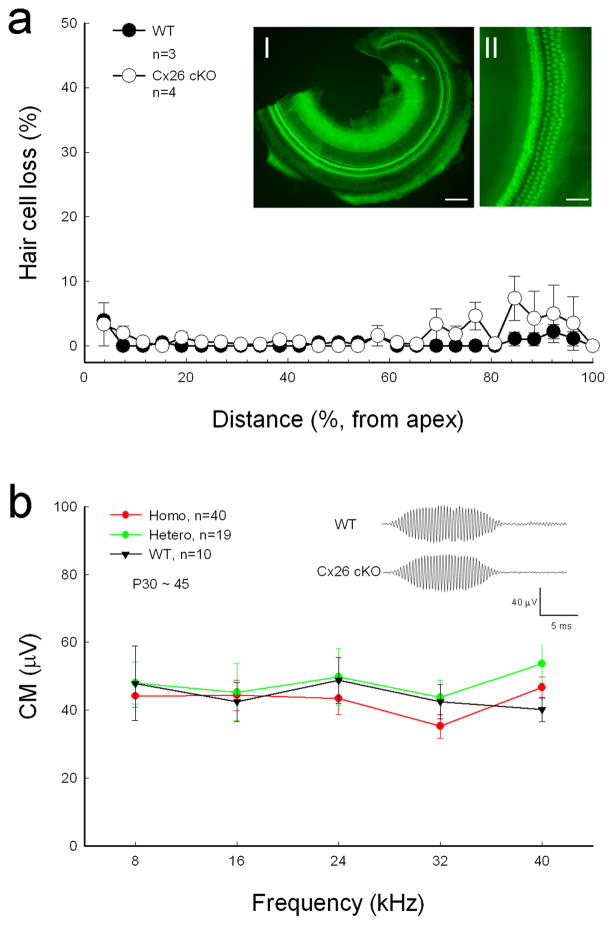

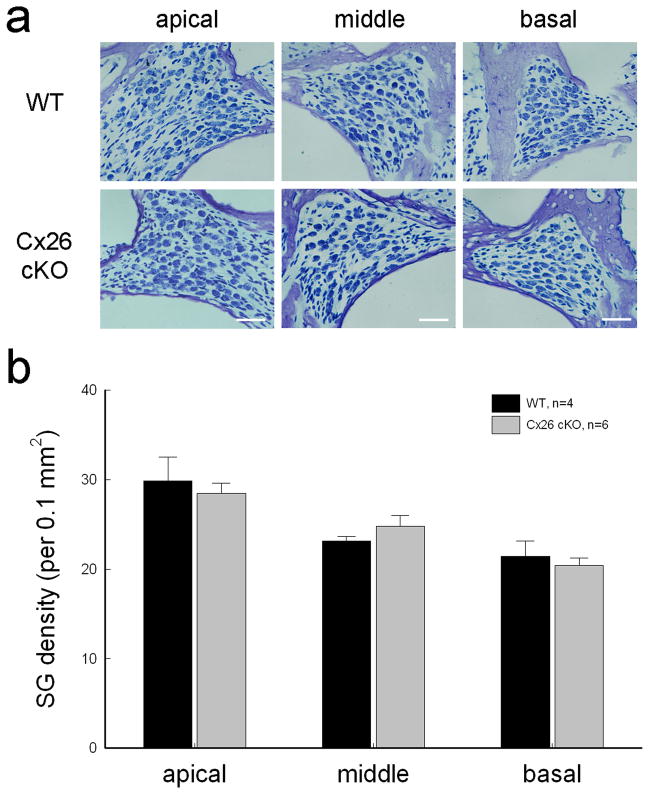

No apparent cell degeneration in the Cx26 cKO mouse cochlea

Targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs did not cause apparent hair cell loss and cell degeneration in the inner ear. Figure 4a shows that hair cell loss in Cx26 cKO mice was less than 5% at P30–60 and was not significantly different from WT mice. In particular, there was no signification hair cell loss at the high-frequency region (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Spiral ganglion (SG) neurons also had no apparent degeneration in Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 5). In comparison with WT littermates, the density of SG neurons in Rosenthal’s canal was not significantly reduced in Cx26 cKO mice (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 5b).

Fig. 4.

Cx26 cKO mice have normal CM and no substantial hair cell loss. a: Hair cell accounting at Cx26 cKO mice. Mice were P30–60 old. WT littermates served as control. Insets I and II: The whole-mounting cochlear sensory epithelium was stained by phalloidin for hair cell accounting. Scale bars = 100 μm in I; 50 μm in II. b: CM responses of homozygous and heterozygous Cx26 cKO mice and WT mice. The CM was evoked by 90 dB SPL tone bursts. Insets: CM waveform recorded from WT and Cx26 cKO mice. Error bars represent S.D.

Fig. 5.

No spiral ganglion (SG) neuron degeneration in Cx26 cKO mice. a: SGs in Rosenthal’s canal at the apical, middle, and basal turn. The sections were stained with toluidin blue. WT littermates served as control. The mice were P30–60 old. Scale bars = 30 μm. b: The density of SGs in Rosenthal’s canal at the apical, middle, and basal turns. There is no significant difference in SG densities between Cx26 cKO mice and WT mice (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

Normal cochlear microphonics and endocochlear potentials

Cochlear microphonics (CM) is the auditory receptor potential and is produced by hair cell mechanoelectrical transduction channel activity and EP driving force. CM in Cx26 cKO mice was normal (Fig. 4b). Cx26 cKO mice also had normal endocochlear potential (EP). The recorded EP in WT, heterozygous, and homozygous mice was 92.0±2.31 mV (n=4), 95.0±0.58 mV (n=3), and 91.5±0.50 mV (n=2), respectively.

Left-shift of OHC nonlinear capacitance in Cx26 cKO mice

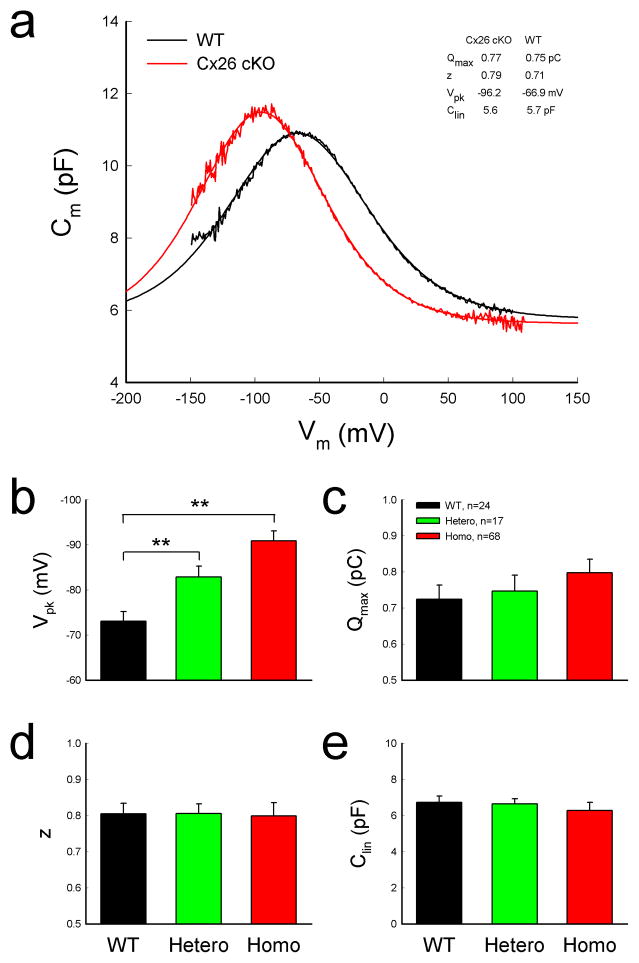

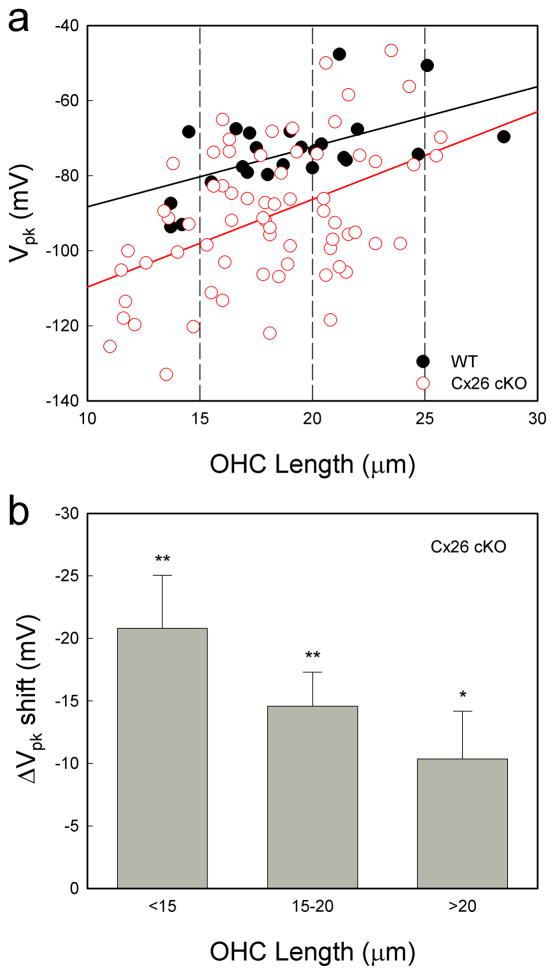

OHC electromotility associated NLC in Cx26 cKO mice retained a normal bell-shape but was shifted to the left in the hyperpolarization direction (Fig. 6a). The voltage of peak capacitance (Vpk) was significantly shifted from −73.8±2.14 mV in WT mice to − 90.9±2.22 mV in homozygous mice (Fig. 6b, P=0.00004, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction). Vpk in heterozygous mice was −82.9±2.37 mV and also had a significant left-shift by ~10 mV (P=0.0003, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction). The Vpk-shifting is larger in shorter OHCs (Fig. 7). Linear regression analysis shows that the slope of Vpk-shift with cell length is 2.33±0.55 (mean±SD, r2=0.22) and 1.60±0.49 mV/ μm (r2=0.32) in Cx26 cKO and WT mice, respectively (Fig. 7a). The slopes had significant difference between Cx26 cKO and WT mice (P=0.004, Univariate analysis of variance). The Vpk at OHC lengths <15, 15–20, and >20 μm was left-shifted by −20.8±4.25, −14.6±2.72, and −10.37±3.81 mV, respectively, in Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 7b, P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction).

Fig. 6.

Left-shift of OHC NLC in Cx26 cKO mice. a: NLC recorded from Cx26 cKO and WT mice. Smooth lines represent fitting by the first derivative of Boltzmann equation. b–e: Parameters of NLC fitting. WT littermates served as a control group. Mice were P50–60 old. **: P < 0.001 as determined by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D;

Fig. 7.

Large-shifting of NLC in shorter OHCs. a: Distribution of Vpk of NLC with OHC length. The solid lines represent linear fitting: y = 1.60x −104.3 and y = 2.33x −133.1 for WT and Cx26 cKO mice, respectively. b: Vp–shifting in Cx26 cKO mice as function of OHC length. In comparison with WT, changes of the Vpk in Cx26 cKO mice were pooled in OHC length <15, 15–20, >20 μm ranges and averaged. *: P< 0.05, **: P< 0.01, one- way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

However, there was no significant difference in linear capacitance (Clin) (Fig. 6e). The Clin in homozygous, heterozygous, and WT mice was 6.23±0.43, 6.65±0.27, and 6.73±0.34 pF, respectively (P=0.84, one-way ANOVA). Direct length measurement also shows that the average of lengths of recorded OHCs in WT and Cx26 cKO mice was 19.04±0.76 (n=24) and 18.09±2.14 μm (n=68), respectively. There was no significant difference between them (P=0.28, t-test).

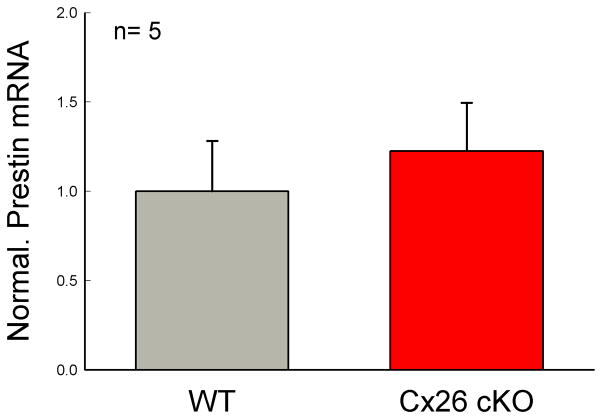

No reduction in prestin expression and function

Maximum charge (Qmax) reflects the functional expression of prestin at the OHC lateral wall. Qmax in WT mice and heterozygous and homozygous Cx26 cKO mice was 0.72±0.04, 0.75±0.04, and 0.80±0.04 pC, respectively (Fig. 6c). The Qmax in Cx26 cKO mice had a slight increase rather than decrease. However, the increase was not significant (P=0.13, one-way ANOVA). Real-time RT-PCR measurement also shows that the prestin expression at the transcription level was slightly increased rather than decreased in Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 8). The increase was also not significant (P=0.58, one-way ANOVA). There was no difference in valence z as well among WT mice and heterozygous and homozygous Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 6d, P=0.89, one-way ANOVA).

Fig. 8.

No prestin expression reduction in Cx26 cKO mice. Prestin expression at the transcriptional level was measured by real-time RT-PCR. WT littermates served as controls. Prestin expression in the Cx26 cKO mice appears slightly increased rather than decreased. However, the increase is not significant (P= 0.58, one-way ANOVA). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

Discussion

We previously reported that in vitro uncoupling of gap junctions between DCs shifts OHC electromotility toward hyperpolarization and reduces the production of distortion products [17], indicating that supporting cells can play a role in the regulation of OHC electromotility. In this study, we selectively deleted Cx26 expression in DCs and OPCs in vivo (Figs. 1& Supplementary Fig. S1). We found that the deletion shifted OHC electromotility to the left in the same hyperpolarization direction (Figs. 6&7) and caused DPOAE reduction and hearing loss (Figs. 2&3). These new findings provide direct evidence that cochlear supporting cells and gap junctions in vivo can regulate OHC electromotility to control active cochlear mechanics and hearing sensitivity.

Two active cochlear mechanics have been proposed: one is the prestin-based OHC electromotility [1, 3–5]; another is the stereocilium-based hair bundle movement [2, 27–29]. Deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs shifted OHC electromotility toward hyperpolarization (Figs. 6&7). As previously reported [30], this shift can reduce the gain of OHC electromotility amplification. The left-shift can also alter the phase difference between OHC electromotility and active force generation [31–32]. To augment sound-evoked vibrations of the BM in vivo, maximal OHC contraction need coincide with maximal BM velocity in the direction of scala vestibule [33–34]. Other timing relationships will cause smaller amplification or even attenuation. Indeed, DPOAE was significantly reduced in Cx26 cKO mice (Fig. 3), even prestin expression was not reduced (Figs. 6c&d and 8). Recently, we found that Cx26 deficiency can alter supporting cell micromechanical property [35]. Supporting cell mechanical property change can alter OHC loading and membrane tension to shift OHC electromotility [36–37] and the phase between the OHC length change and the feedback of active force to the BM vibration [31–32]. As discussed above, these changes can eventually reduce the outcome of OHC electromotility and active cochlear amplification to induce hearing loss.

In Cx26 cKO mice, DPOAE reduction and hearing loss were larger and more severe at high frequencies (Figs. 2&3). However, Cx26 deletion in DCs and OPCs was uniform at the apical, middle, and basal turns (Supplementary Fig. S1). We previously found that Cx26 expression at the cochlear sensory epithelium is gradually reduced from the cochlear apex to base [15]. The basal turn has less Cx26 expression. The reduction is more pronounced in DCs and OPCs. So, targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs may produce more severe function impairment at high frequencies. In addition, deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs can reduce gap junctional coupling and may impair potassium recycling as well [19, 38]. Computer modeling shows that this can attenuate OHC transmembrane potential to reduce the activity of OHC electromotility, in particular, at the high frequency region [39]. Finally, shorter OHCs had larger shift in OHC electromotility (Figs. 6&7). These coincident changes strongly suggest that targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs left-shifted OHC electromotility resulting into active cochlear mechanics reduction and hearing loss.

Frequency-dependent hearing loss (Fig. 2) is also inconsistent with the EP reduction induced whole-frequency deafness. Moreover, Cx26 cKO mice retained normal CM and EP (Fig. 4b), implying that the Cx26 cKO mice may retain normal hair cell transduction activity. These data further support the concept that targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs causes OHC electromotility left-shifting rather than EP reduction to induce the reduction of active cochlear mechanics and hearing loss.

Cx26 mutations are a common genetic cause for nonsyndromic hearing loss [18–20]. However, the underlying deafness mechanisms still remain unclear. Previous mouse models with extensive deletion of Cx26 in the cochlea show that Cx26 deficiency can induce cochlear development disorder, hair cell degeneration, and congenital deafness [21–22, 40]. However, clinical phenotypes of Cx26 mutation are various. A large group (~30%) of Cx26 mutation patients shows a progressive, late-onset hearing loss [18–20]. Our new study also found that hair cell degeneration is not a primary cause for Cx26 deficiency induced hearing loss [21]. Some mechanisms other than cochlear development disorder and hair cell degeneration must be engaged. In this study, we found that targeted-deletion of Cx26 in DCs and OPCs had hearing loss (Fig. 2) but had no cochlear development disorders (Figs. 1& Supplementary Fig. S1) and no significant hair cell and SG neuron degenerations (Figs. 4&5). OHC electromotility was left-shifted (Figs. 6&7) and DPOAE was reduced (Fig. 3). These new findings provide not only new information about supporting cell dependence of active cochlear mechanics in vivo but also a new mechanism for Cx26 deficiency induced deafness, particularly, for late-onset hearing loss, which patients have a significant DPOAE reduction [41–42].

Materials and Methods

Generation of Cx26 conditional KO mouse and genotyping

Cx26loxP/loxP transgenic mice (EMMA, EM00245) [22] were crossed with Prox1-CreERT2 mouse line [23]. Prox1-CreERT2;Cx26LoxP(+/−) mice were used for breeding. Tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administrated to all litters at postnatal day 0 (P0) by intraperitoneal injection (0.5 mg/10g × 3 days). Mouse genotyping was identified by PCR amplification of tail genomic DNA [22–23]. WT littermates were used as control. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the policies of the University of Kentucky Animal Care & Use Committee.

In vivo physiological measurements

ABR, DPOAE, and CM recordings were performed in a double-wall sound isolated chamber by use of a Tucker-Davis ABR & DPOAE workstation with ES-1 high frequency speaker (Tucker-Davis Tech. Alachua, FL) [21]. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (8.5 ml saline+1 ml Ketamine+0.55 ml Xylazine, 0.1 ml/10 g). Body temperature was maintained at 37–38°C. ABR was measured by clicks in alternative polarity and tone bursts (8 – 40 kHz) from 80 to 10 dB SPL in a 5 dB step. The ABR threshold was determined by the lowest level at which an ABR can be recognized. If mice had severe hearing loss, the ABR test from 110 to 70 dB SPL was added. For CM recording, the electrode was ventrolaterally inserted deeply into the temporal bone [21]. The signal was amplified (50,000 x), filtered (3 – 50 kHz), and averaged by 250 times.

For DPOAE recording, the test frequencies were presented by a geometric mean of f1 and f2 [f0 = (f1 × f2)1/2] from f0=4 to 20 kHz with a ratio of f1:f2=1:1.2. The distortion product was recorded from the L1/L2 level of 60/55 to 25/20 dB SPL with average of 150 times. A cubic distortion component of 2f1–f2 was measured.

EP was measured by a lateral-wall access. Mice were anesthetized and body temperature was maintained at 37–38°C. The cochlea was exposed by a ventral approach. Access to the endolymphatic compartment (scala media) of the middle turn was gained by thinning the bone over the spiral ligament and picking a small hole. The glass microelectrode was filled with a K+-based intracellular solution (140 KCl, 10 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES in mM, pH7.2) and the EP was recorded with an AD/DA board (PCI- 6052E, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

Immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy

The cochlear tissue preparation and immunofluorescent staining were performed as previously reported [15]. Monoclonal mouse anti-Cx26 (Cat# 33-5800, Invitrogen Corp), polyclonal rabbit anti-Cx30 (Cat#71-2200, Invitrogen Corp), and polyclonal goat anti-prestin (Cat# sc-22694, Santa Cruz Biotech Inc, CA) were used and visualized by secondary Alexa Fluor® 488 or 568 conjugated antibodies (Molecular Probes). The staining was observed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Toluidine blue staining and spiral ganglion neuron accounting

Consecutive cochlear paraffin sections were stained with toluidine blue using the conventional protocol [21]. To count the SG neurons, two neighboring sections separated by 40 μm were used to eliminate the possibility of double counting. Counting errors was corrected by Abercrombie’s equation [43]: T/(T+D), in which T is the section thickness (10 μm) and D is the mean diameter (8.65 μm) of the SG neurons. The area of Rosenthal’s canal in the cochlear sections was measured by NIH image software [21]. The densities of SG neurons in apical, middle, and basal turns were calculated by the number of SG neurons in the section divided by the area of Rosenthal’s canal.

Real-time RT-PCR measurement of prestin expression

As we previous reported [44], the cochlea was freshly isolated and homogenized. Its RNA was extracted by Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Stratagene, La Jalla, CA), following manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of total mRNAs were determined by NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Rockland, DE). The obtained mRNA was converted to cDNA by iScript™cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad laboratories, Inc. Hercules, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by MyiQ real-time PCR detection system with iQ SYBR Green Super Mix kit (Cat. #: 170822, Bio-Rad laboratories). The primers for prestin were 5′-GTT GGG TGG CAA GGA GTT TA-3′, 5′-ACA GGG AGG ACA CAA AGG TG-3′. The cycling condition of PCR amplification was 95°C 30 sec, 55°C 30 sec, and 72°C 30 sec, 45 cycles. Each cochlear sample was measured in triplicate and averaged. Universal 18S (QuantumRNATM 18S Internal Standards, Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) served as an internal control. The relative quantities of prestin expression were calculated from standard curves and normalized to the amount of 18S.

Patch-clamp recording of OHC nonlinear capacitance

OHCs were freshly isolated from the cochlea [21, 44]. The classical patch clamp recording was performed under whole-cell configuration by using an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, CA) with jClamp (Scisft, New Haven, CT). Nonlinear capacitance (NLC) was measured by a two-sinusoidal method and fitted to the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function with jClamp and MATLAB [17, 44].

| (1) |

where Qmax is the maximum charge transferred, Vpk is the peak of NLC, z is the number of elementary charge (e), k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the absolute temperature. Membrane potential (Vm) was corrected for electrode access resistance (Rs).

Statistical analysis

Data were plotted by SigmaPlot and statistically analyzed by SPSS v13.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL). Error bars represent SEM other than indicated in text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Guillermo Oliver at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN for kindly providing Prox1-Cre mouse line. This work was supported by NIH R01 DC 05989.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.Z., C.L., L. Z, J.C., and H.B.Z. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. G.D.C. contributed to figure 4a. H.B.Z. wrote the paper.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Dallos P. Cochlear amplification, outer hair cells and prestin. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudspeth AJ. Making an effort to listen: mechanical amplification in the ear. Neuron. 2008;59:530–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng J, et al. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 2000;405:149–155. doi: 10.1038/35012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashmore J. Cochlear outer hair cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao HB, Santos-Sacchi J. Auditory collusion and a coupled couple of outer hair cells. Nature. 1999;399:359–362. doi: 10.1038/20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberman MC, et al. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slepecky NB. In: The cochlea. Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Springer; New York: 1996. pp. 44–129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsa A, Webster P, Kalinec F. Deiters cells tread a narrow path-The Deiters cells-basilar membrane junction. Hear Res. 2012;290:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulon D, Blanchet C, Laffon E. Photo-released intracellular Ca2+ evokes reversible mechanical responses in supporting cells of the guinea-pig organ of Corti. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1263–1269. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bobbin RP. ATP-induced movement of the stalks of isolated cochlear Deiters’ cells. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2923–2926. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200109170-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobbin PP, Campbell J, Lousteau S, Mandhare M. Electrical and ATP induced movements of the phalangeal processes of isolated cochlear Deiters’ cells. In: Berlin CI, Hood LJ, Ricci A, editors. Hair cell micromechanics and otoacoustic emissions. Thomson Delmar Learning; Clifton Park, New York: 2002. pp. P91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi T, Kimura RS, Paul DL, Adams JC. Gap junctions in the rat cochlea: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Anat Embryol. 1995;191:101–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00186783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forge A, et al. Gap junctions in the inner ear: comparison of distribution patterns in different vertebrates and assessement of connexin composition in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:207–231. doi: 10.1002/cne.10916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao HB, Yu N. Distinct and gradient distributions of connexin26 and connexin30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium of guinea pigs. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:506–518. doi: 10.1002/cne.21113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao HB. Directional rectification of gap junctional voltage gating between Deiters cells in the inner ear of guinea pig. Neurosci Lett. 2000;296:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu N, Zhao HB. Modulation of outer hair cell electromotility by cochlear supporting cells and gap junctions. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelsell DP, et al. Connexin 26 mutations in hereditary non-syndromic sensorineural deafness. Nature. 1997;387:80–83. doi: 10.1038/387080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao HB, Kikuchi T, Ngezahayo A, White TW. Gap junctions and cochlear homeostasis. J Memb Biol. 2006;209:177–186. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0832-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castillo FJ, Castillo I. The DFNB1 subtype of autosomal recessive non- syndromic hearing impairment. Front Biosci. 2011;17:3252–3274. doi: 10.2741/3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang C, Zhu Y, Zong L, Lu GJ, Zhao HB. Cell degeneration is not a primary causer for Connexin26 (GJB2) deficiency associated hearing loss. Neurosci Lett. 2012;528:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen-Salmon M, et al. Targeted ablation of connexin26 in the inner ear epithelial gap junction network causes hearing impairment and cell death. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00904-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivasan RS, et al. Lineage tracing demonstrates the venous origin of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2422–2432. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bermingham-McDonogh O, et al. Expression of Prox1 during mouse cochlear development. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:172–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.20944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirjavainen A, et al. Prox1 interacts with Atoh1 and Gfi1, and regulates cellular differentiation in the inner ear sensory epithelia. Dev Biol. 2008;322:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Y, et al. In vivo proliferation of postmitotic cochlear supporting cells by acute ablation of the retinoblastoma protein in neonatal mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5927–5936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5989-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan DK, Hudspeth AJ. Ca2+ current-driven nonlinear amplification by the mammalian cochlea in vitro. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:149–155. doi: 10.1038/nn1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy HJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Force generation by mammalian hair bundles supports a role in cochlear amplification. Nature. 2005;433:880–883. doi: 10.1038/nature03367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fettiplace R. Active hair bundle movements in auditory hair cells. J Physiol. 2006;576:29–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopalan L, et al. Tuning of the outer hair cell motor by membrane cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36659–36670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705078200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fridberger A, Flock A, Ulfendahl M, Flock B. Acoustic overstimulation increases outer hair cell Ca2+ concentrations and causes dynamic contractions of the hearing organ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7127–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flock A, Flock B, Fridberger A, Scarfone E, Ulfendahl M. Supporting cells contribute to control of hearing sensitivity. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4498–4507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04498.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gummer AW, Hemmert W, Zenner HP. Resonant tectorial membrane motion in the inner ear: its crucial role in frequency tuning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8727–8732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zha D, et al. In vivo outer hair cell length changes expose the active process in the cochlea. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, et al. New function for Connexin26 (Cx26) in the cochlea and new mechanism for deafness induced by deficiency in Cx26. The 36th Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. Annual Meeting; Baltimore, MD. 2013. http://www.aro.org. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwasa KH. Effect of stress on the membrane capacitance of the auditory outer hair cell. Biophys J. 1993;65:492–498. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kakehata S, Santos-Sacchi J. Membrane tension directly shifts voltage dependence of outer hair cell motility and associated gating charge. Biophys J. 1995;68:2190–2197. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80401-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y, Zhao HB. ATP-mediated potassium recycling in the cochlear supporting cells. Purinergic Signal. 2010;6:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s11302-010-9184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mistrík P, Ashmore JF. Reduced electromotility of outer hair cells associated with connexin-related forms of deafness: an in silico study of a cochlear network mechanism. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2010;11:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, et al. Targeted connexin26 ablation arrests postnatal development of the organ of Corti. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engel-Yeger B, et al. The effects of a connexin 26 mutation – 35delG – on oto-acoustic emissions and brainstem evoked potentials: homozygotes and carriers. Hear Res. 2002;163:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engel-Yeger B, et al. Otoacoustic emissions and brainstem evoked potentials in compound carriers of connexin 26 mutations. Hear Res. 2003;175:140–151. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillery RW. On counting and counting errors. J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:1–7. doi: 10.1002/cne.10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu N, et al. Prestin up-regulation in chronic salicylate (aspirin) administration: An implication of functional dependence of prestin expression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2407–2418. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.