Abstract

Peptide nanostructures containing bioactive signals offer exciting novel therapies of broad potential impact in regenerative medicine. These nanostructures can be designed through self-assembly strategies and supramolecular chemistry, and have the potential to combine bioactivity for multiple targets with biocompatibility. It is also possible to multiplex their functions by using them to deliver proteins, nucleic acids, drugs, and cells. In this review, we illustrate progress made in this new field by our group and others using peptide-based nanotechnology. Specifically, we highlight the use of self-assembling peptide amphiphiles towards applications in the regeneration of the central nervous system, vasculature and hard tissue along with the transplant of islets and the controlled release of nitric oxide to prevent neointimal hyperplasia. Also, we discuss other self-assembling oligopeptide technology and the progress made with these materials towards the development of potential therapies.

1. Introduction

The expectation of humans to live long lives free from morbidity and pain demands continuous development of new therapeutic strategies that can promote the regeneration and optimal healing of tissues and organs damaged by trauma, disease, or congenital defects. The field of regenerative medicine aims to meet these demands, focusing on restoring lost, damaged, aged, or dysfunctional cells and their extracellular matrices to return function to tissues. There are many targets where new therapies could greatly improve both the span and quality of life; of special importance among these are conditions where normal physiologic regeneration is limited or non-existent. For example, the ability to regenerate the central nervous system would provide a higher quality of life to individuals paralyzed by spinal cord injury, suffering serious dysfunction from stroke, and living with degenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and multiple sclerosis. Regenerative strategies are also needed to combat heart disease and heart failure, which remain some of the leading causes of mortality, and to prompt the development of new vasculature to deliver blood to ischemic tissues and organs. Regeneration of pancreatic β cells would bring a higher quality of life to the many young people suffering from diabetes, who for now are reliant on regular insulin injections. The regeneration of teeth would eliminate the need for dentures and other dental implants. Musculoskeletal ailments such as damage to bones, tendons, and ligaments and osteoarthritis resulting from irreversible cartilage damage all are an enormous source of pain and truly compromise one’s ability to carry on an active lifestyle. These are but a few of the many targets that are in need of new regenerative strategies. Human ailments are truly complex, and innovative therapies necessitate the merging of many diverse fields including stem cell science, developmental biology, molecular biology, genetics, materials science, chemistry, bioengineering, and tissue engineering [1]. These collaborative efforts are the only foreseeable means by which to make progress in the treatment of disease and ultimately improve the human condition. This review demonstrates how we, and others, have initiated efforts towards regenerative therapies using peptide-based strategies for self-assembly, supramolecular chemistry, and nanotechnology.

The need for new regenerative strategies has coincided with, and likely promoted, the emergence of the field of bionanotechnology. Over the past decade, the focus of nanoscience has shifted from the synthesis, development and characterization of novel nanostructures to the exploration of potential applications for this technology to assist in crucial problems as diverse as energy and medicine. The organization of human tissue begins on the nanoscale, with complex biological molecules providing the structural and functional infrastructure for life’s processes. Thus, therapies designed on this scale with specific structure and function have the potential to similarly serve as matrix for cells, participate in biological signaling, and to efficiently deliver proteins and drugs, all of this through minimally invasive therapies. To date, a broad range of nanostructures including peptide nanofibers [2], carbon nanotubes [3, 4], inorganic nanoparticles such as quantum dots [5], and dendrimers [6, 7] have been explored in disease diagnostics, drug delivery, and regenerative strategies.

Molecular self-assembly is a very attractive strategy to construct nanoscale materials for applications in regenerative medicine due both to its simplicity in application and its unique capacity to produce a variety of diverse nanostructures [8–10]. This spontaneous process organizes small molecules into structures that are ordered on multiple length scales. The structural features of the final supramolecular assemblies can be controlled through molecular design and by finely tuning assembling conditions and kinetics. For applications of these self-assembled materials, the ultimate goal is for the material to achieve its desired function. For example, assemblies used for cell scaffolds would ideally incorporate both the necessary structural support as well as the ability to signal transplanted or native cells, thus serving to mimic the complex signaling machinery of native extracellular matrix. Furthermore, molecular design can be used to create structures that biodegrade over an appropriate time scale. In order to achieve maximal function in a minimally invasive way, these networks can be designed to start as small molecules in a liquid that can be injected easily into tissues and self-assembly would then transform them in situ into solid scaffolds or nanostructures, specifically designed with application-specific control over degradation to further limit invasiveness of the therapy.

Peptides are a unique platform for the design of self-assembled materials with controllable structural features at the nanoscale. The chemical design versatility afforded by amino acid sequences leads to a variety of possible secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures through folding and hydrogen bonding. β-sheet forming peptides, in particular, have demonstrated the extraordinary ability to use intermolecular hydrogen bonding for the assembly of one-dimensional nanostructures [11]. For applications in regenerative medicine, peptides have additional appeal due to their inherent biocompatibility and biodegradability. Entanglement of peptide-based nanostructures can lead to the formation of three-dimensional networks, allowing these nanofibers to mimic the structure of native extracellular matrix. Further, the ability to incorporate biological peptide-based signaling sequences affords control over the function of these nanofiber networks. While the large-scale synthesis of proteins comprising hundreds of residues while ensuring appropriate folding and post-translational modifications remains a formidable challenge, oligopeptides can be produced rather easily using standard solution or solid-phase synthetic methods. Futhermore, the design of self-assembly peptides for targeted functions can also include their modification with other biomolecular units such as sugars, lipid components, and nucleic acid monomers. These oligopeptides, while designed for supramolecular self-assembly, could also serve to functionally mimic large proteins. For these reasons, self-assembling, non-immunogenic peptides project as promising new therapeutics for human disease.

2. Peptide Amphiphiles: Technology

2.1 Design of Peptide Amphiphiles

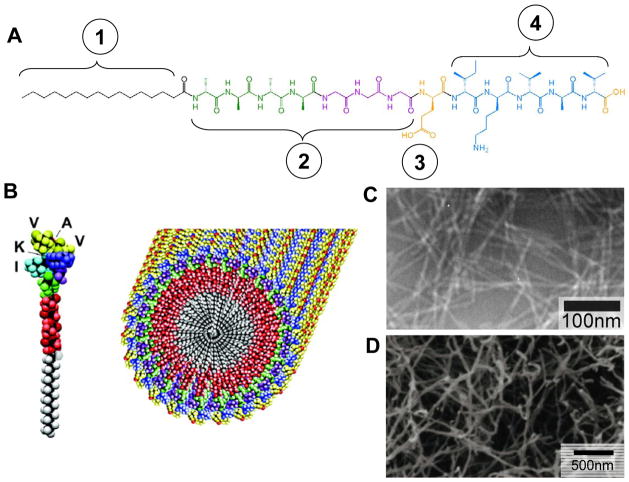

Within the past decade, the Stupp laboratory has synthesized several amphiphilic molecules designed to self-assemble into biomaterials [2, 12–15]. A broad class, known as peptide amphiphiles (PAs), incorporates a short hydrophobic domain on one end of a hydrophilic oligopeptide sequence [2, 8, 9, 11, 15]. Shown in Figure 1 is the chemical structure of a representative PA molecule, which is composed of four key structural domains [2, 16]. Domain 1, the hydrophobic domain, typically consists of an alkyl chain analogous to lipid tails and can be tuned by using different chain lengths or different hydrophobic components [15]. Domain 2, immediately adjacent to the hydrophobic segment, consists of a short peptide sequence designed to promote intermolecular hydrogen bonding, typically β-sheet formation, that induces the assembly of the molecules into high aspect ratio cylindrical or twisted nanofibers, and in some cases nanobelts [17, 18]. Domain 3 incorporates charged amino acids to enhance solubility in water and to enable the design of pH or salt-induced self-assembly of the molecules. Domain 4 can be used for the display on the nanostructure surface of bioactive signals in the form of oligopeptide sequences designed to interact with cells, proteins, or biomolecules. If domain 4 has a sufficient number of charged amino acids to provide solubility and charge screening possibilities, then domain 3 is not necessary in the design of the PA. This classical PA molecule assembles into high aspect-ratio nanofibers with dimensions similar to native extracellular matrix fibrils. The driving force for this assembly is based on both hydrophobic collapse of domain 1 away from the aqueous environment and propensity for intermolecular hydrogen bond formation. In physiologic media, the charged amino acids become screened by electrolytes, diminishing the electrostatic repulsion. Hydrophobic collapse drives the alkyl tails to aggregate away from the aqueous media, and intermolecular hydrogen bonds form parallel to the long axis of the fiber [18]. This assembly mechanism allows the bioactive region of the PA molecule to be presented on the surface of the nanofiber where it can interact with cells, proteins, or biopolymers. These 1D nanostructures can further entangle into networks, and form self-supporting gels at relatively low concentrations, on the order of 1% by weight [19, 20].

Figure 1.

(A) Molecular Structure of a representative peptide amphiphile with four rationally designed chemical entities. (B) Molecular graphics illustration of an IKVAV-containing peptide amphiphile molecule and its self-assembly into nanofibers; (C) TEM micrograph of IKVAV nanofibers; (D) SEM micrograph of IKVAV nanofiber gel network. Reprinted with permission from Gabriel Silva et. al., Selective differentiation of neural progenitor cells by high-epitope density nanofibers, Science, 2004; 303, 1352–1355 (parts B, D) and with permission from Krista Niece et. al., Self-assembly combining two bioactive peptide-amphiphile molecules into nanofibers by electrostatic attraction, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2003; 125(24), 7146–7147 (part C).

The salt- or pH-responsive design element is a critical feature that makes PAs ideal candidates for minimally invasive therapies. This feature allows unassembled PA molecules to be combined with bioactive entities, such as growth factors, DNA or glycosaminoglycans, or with cells to form a liquid cocktail with very low viscosity. Upon injection into the tissue, electrolytes in the physiological environment can immediately induce the self-assembly of PAs into nanofibers and subsequent formation of gelled networks encapsulating the desired payload. From the standpoint of applications for regenerative medicine, we are mainly interested in using individual PA nanofibers to signal cells through the display of bioactive epitopes, while employing three-dimensional networks of these high-aspect-ratio nanofibers as bioactive scaffolds to simultaneously support, deliver, and signal cells.

2.2 Cell Scaffolds and Substrates

Hydrogels have the potential, due to their fibrillar interconnected structure, to serve as a three dimensional support to study the behavior of cells in vitro or deliver and support therapeutic cells in vivo. One-dimensional PA nanofibers can bundle and entangle into such a self-supporting three-dimensional gel network. This transition typically requires screening by multivalent ions in physiologic media, and allows cells to be encapsulated in the resulting nanofiber matrix [21]. These cells, once entrapped within PA nanofiber networks, are viable for several weeks and continue to proliferate, indicating no cell cycle arrest. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) suggests internalization of the PA by these encapsulated cells, and biochemical assays demonstrate evidence of PA metabolism. PA nanofibers not only are capable of displaying signals to cells, but also provide structural support to the encapsulated cells and could be eventually metabolized into nutrients. This supports the idea that three-dimensional networks of PA nanofibers can serve as an artificial extracellular matrix, and the architectural similarities between PA nanofibers and the filamentous structures found in natural extracellular matrix could allow these PA networks to function as a highly biomimetic artificial matrix. The gelation kinetics of peptide amphiphile nanofiber networks are also tunable by changing the internal peptide sequence while keeping the bioactive domain constant, producing nanofiber gels with a range of gelation times [22]. Changes in the region promoting β-sheet formation to include more bulky and hydrophilic residues, such as SLSLGGG instead of AAAAGGG, significantly increases the time for gelation. This gives design flexibility to tune the gelation time of these injectable PA nanofiber gels for a desired application.

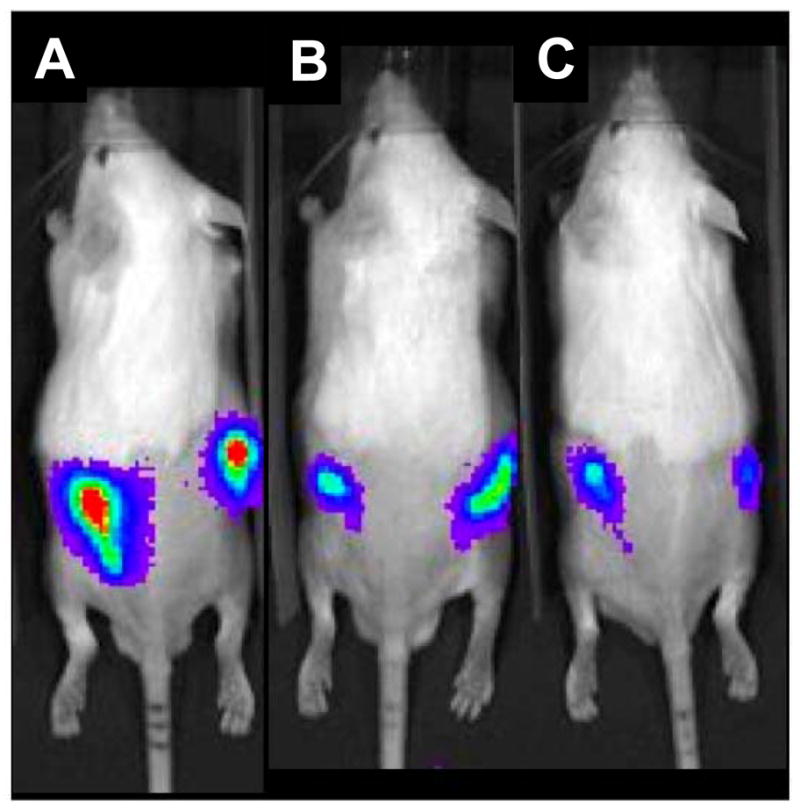

PAs as scaffolds for cells can be further tuned by the addition of a bioactive sequence to signal the encapsulated cells. For example, in order to enhance matrix-cell interaction, the Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (RGDS) peptide epitope has been incorporated into the PA molecular design. Using orthogonal protecting group chemistry, the covalent architecture in which this epitope is presented on the nanofiber surface can be varied, producing PAs that present RGDS in linear, branched, double-branched or cyclic geometries [23]. PAs designed with a branched architecture show improved cell attachment and migration, likely due to decreased molecular packing altering the density of epitopes on the nanofiber surfaces [24]. The role of nanostructure shape on the bioactivity of the displayed epitope was recently evaluated, comparing the bioactivity of RGDS presented on nanospheres with that of the epitope presented on nanofibers [25]. It was found that epitopes presented on the surface of nanofibers are significantly more bioactive than those presented at equal density on the surface of nanospheres. Co-assembly of bioactive and non-bioactive PA molecules can enable control over the epitope densities presented to cells. Using this approach, a PA system presenting RGDS was prepared and optimized for biological adhesion as a scaffold for the therapeutic delivery of bone marrow mononuclear cells [26]. In a preliminary in vivo study, this material contributed significant support to the therapeutic cells following percutaneous co-injection (Figure 2). In addition to being the main component of a scaffold, PAs can also be used as coatings to lend bioactivity to traditional tissue engineering materials. For example, coating RGDS PAs onto poly(glycolic acid) significantly enhances the adhesion of primary human bladder cells to the scaffold in vitro [27].

Figure 2.

(A) Therapeutic bone marrow mononuclear cells derived from a luciferase transgene mouse and transplanted within an RGDS-presenting PA network into either flank of a wild-type mouse, imaged at 4 days following transplant; (B) The same cells when transplanted within a PA network that did not contain the RGDS eptiope; (C) The same cells, transplanted with only a saline vehicle. Reprinted with permission from Matthew Webber et. al., Development of bioactive peptide amphiphiles for therapeutic cell delivery, Acta Biomaterialia, 2009; in press.

Not only have PAs been used as scaffolds that provide structural support and bioactive signals, but these materials have also been molded to allow for the study of the effects of matrix geometry of the behavior of cells. We have used microfabrication and lithography techniques to develop well-defined topographical patterns of PAs with microscale and nanoscale resolution [28–30]. Self-assembly of PAs containing both a photo-polymerizable moiety and the RGDS cell adhesion epitope were designed for use within microfabrication molds. This resulted in networks of nanofibers with well-defined topographical patterns such as holes, posts, or channels produced from networks of either randomly oriented PA nanofibers or pre-aligned PA nanofibers [28]. These surfaces were used as substrates to culture human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), examining for effects of the topographical and nanoscale features on the migration, alignment, and differentiation of these cells. Topographical patterns produced from aligned PA nanofibers were able to promote the alignment of MSCs, indicating cell sensing of both micro- and nanoscale substrate features. Specifically, MSCs underwent osteogenic differentiation when cultured on substrates of randomly oriented nanofibers that had been patterned into hole microtextures.

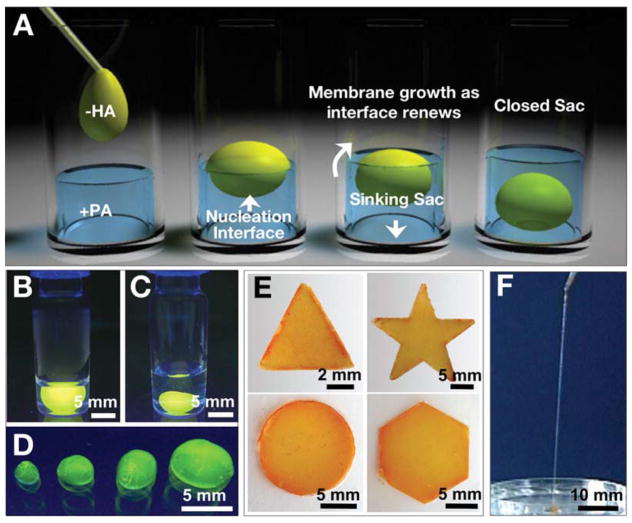

2.3 PA-polymer hybrids

Recently, a new assembly strategy that has been explored is to produce hybrid structures by mixing PA molecules with oppositely charged biopolymers. Mixing a solution of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid (HA) with a solution containing an oppositely charged PA results in immediate formation of a solid membrane at the interface (Figure 3) [31]. When the dense HA solution is placed on top of the PA solution, the HA fluid sinks into the PA solution, leading to continuous growth of the membrane at the progressively renewed liquid-liquid interface. This process eventually results in the formation of a liquid-filled sac. These sacs can be made instantly by injecting HA solution directly into the PA solution, and the resulting robust macroscopic structures can encapsulate human MSCs, which remain viable for up to four weeks in culture. These cells, when stimulated by soluble factors in the media, undergo chondrogenic differentiation while encapsulated in the sac. This synergistic assembly also allows us to produce membranes of arbitrary shape and highly ordered strings. The strategy of utilizing the electrostatic attractions between a large charged molecule and oppositely charged self-assembling small molecules has great potential for the development of highly functional materials organized across multiple length scales that could be used to deliver cells within an isolated and controlled environment for regenerative medicine.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic representation of one method to form a self-sealing closed sac. A sample of the denser negatively charged biopolymer solution is dropped onto a positively charged peptide amphiphile (PA) solution. (B) Open and (C) closed sac formed by injection of a fluorescently tagged hyaluronic acid (HA) solution into a PA solution. (D) Self-assembled sacs of varying sizes. (E) PA-HA membranes of different shapes created by interfacing the large- and small-molecule solutions in a very shallow template ( ~1 mm thick). (F) Continuous strings pulled from the interface between the PA and HA solutions. Reprinted with permission from Ramille Capito et. al., Self-assembly of large and small molecules into hierarchically ordered sacs and membranes, Science, 2008; 319, 1812–1816.

3. Peptide Amphiphiles: Medical Applications

3.1 Neural regeneration

Regeneration of the central nervous system presents a formidable challenge within regenerative medicine, as neurons in the brain and spinal cord have very limited potential for healing and reorganization. The Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (IKVAV) peptide sequence, derived from laminin, has been incorporated into PAs for applications in neural regeneration in order to enhance neural attachment, migration, and neurite outgrowth. Our previous work with PAs presenting this epitope found that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) cultured in vitro within networks of IKVAV PA quickly undergo selective and rapid differentiation into neurons with the formation of astrocytes being largely suppressed [16]. This selective differentiation was even greater for NPCs cultured in our PA networks than it was for cells cultured with laminin, the natural protein bearing the IKVAV sequence on which the synthetic peptide is based. In order to establish cell lineage the proteins β-tubulin III and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) were used as markers for neurons and astrocytes, respectively. NPCs cultured within our PA gel overwhelmingly express β-tubulin III compared to GFAP as they differentiate. This observation is presumably due to the high density at which the epitope is presented on the nanofiber surface. Control experiments using a mixture of soluble IKVAV peptide and PA nanofibers without the IKVAV epitope did not reveal this same response.

The in vitro results showing selective differentiation of NPCs suggested that the IKVAV PA may be a useful material in the treatment of spinal cord injury, where the formation of a glial scar, comprised primarily of astrocytes, prevents axonal regeneration after injury [32]. Indeed, when IKVAV PA nanofibers were applied to a mouse spinal cord injury model, the response in treated animals was quite promising [33]. The animal model used mice treated with an injection of IKVAV PA solution 24 hours following spinal cord injury; at the site of injection this solution should form nanofibers by self-assembly through electrolyte screening of the molecules. The material reduced cell death at the injury site and decreased the astrogliosis involving a hyperplastic state of astroctyes. The injected nanofiber gel also increased the number of oligodendroglia, the cells responsible for the formation of the myelin sheath around neurons in the central nervous system, at the injury site. Histological evidence was also obtained for the regeneration of descending motor axons as well as ascending sensory axons across the site of spinal cord injury in animals treated with the IKVAV PA (Figure 4). This was accompanied by behavioral improvement as well, with treated animals demonstrating enhanced hind limb functionality [33]. The results of this animal study offers great promise for the potential of PAs to restore function to those paralyzed by spinal cord injury, and this target remains an area of focus for our group.

Figure 4.

IKVAV PA promotes regeneration of descending corticospinal motor axons after spinal cord injury. a, b: Representative Neurolucida tracings of BDA-labeled descending motor fibers within a distance of 500 μm rostral of the lesion in vehicle-injected (a) and IKVAV PA-injected (b) animals. The dotted lines demarcate the borders of the lesion. c–f: Bright-field images of BDA-labeled tracts in lesion (c, e) and caudal to lesion (d, f) used for Neurolucida tracings in an IKVAV PA-injected spinal cord (a, b). g, h: Bar graphs show the extent to which labeled corticospinal axons penetrated the lesion. *The groups representing three control and three IKVAV PA mice and the tracing of 130 individual axons differ from each other at p < 0.03 by the Wilcoxon rank test. (R, Rostral; C, caudal; D, dorsal; V, ventral. Scale bars: a–d: 100 μm and e,f: 25 μm.) Reprinted with permission from Vicki Tysseling-Mattiace et. al., Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit glial scar formation and promote axon elongation after spinal cord injury, Journal of Neuroscience, 2008; 28(14), 3814–3823.

3.2 Angiogenesis

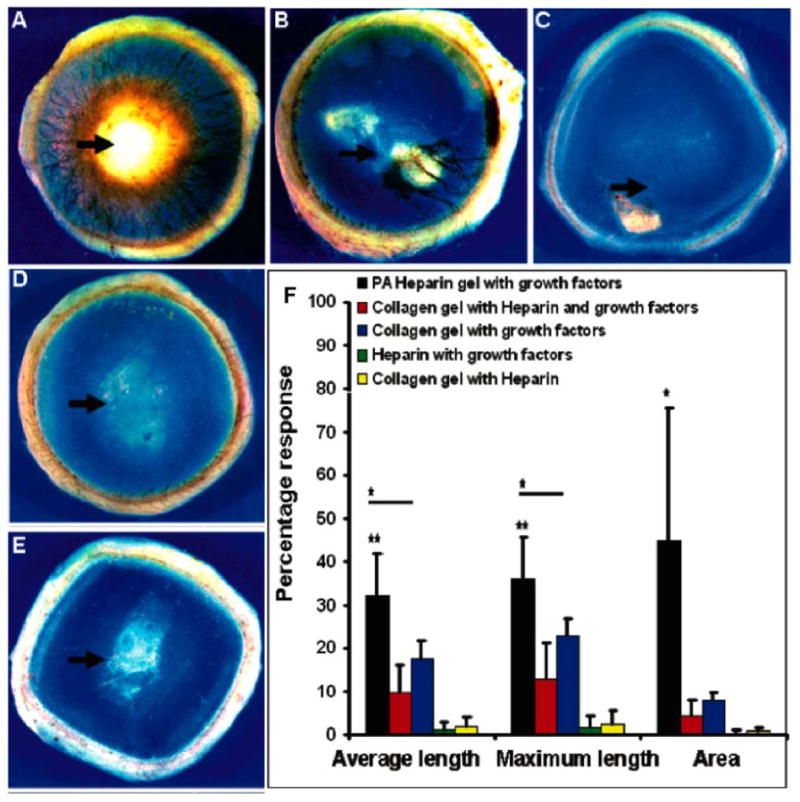

The enhancement of angiogenesis, the development of new blood vessels from existing vasculature, holds promise for the treatment of ischemic diseases of the heart, peripheral vasculature, and chronic wounds [34, 35]. A peptide amphiphile, termed the heparin binding peptide amphiphile (HBPA), was designed with a Cardin-Weintraub heparin-binding domain to specifically bind heparan sulfate-like gylcosaminoglycans (HSGAG). This glycosaminoglycan screens charges on the HBPA molecules, triggering PA self-assembly into nanofibers that display heparin on their surface [36, 37]. The heparin-binding character of HBPA was verified using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), determining an association constant of 1.1×107. The presentation of heparin enables these nanofibers to capture many potent signaling proteins through their heparin-binding domains; such proteins include fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The heparin-presenting HBPA showed a prolonged release of FGF-2 compared to an HBPA network prepared using divalent phosphate ions to screen charges and promote self-assembly. FGF-2 and VEGF are well known to participate in angiogenesis, so our laboratory first explored the HBPA-heparin system for the promotion of new blood vessels. When nanogram quantities of the bioactive factors were combined with the HBPA-heparin and implanted into a surgical pocket of a rat cornea, the material induced significant vascularization compared to growth factors alone, HBPA-heparin without growth factors, and similar materials with and without growth factors (Figure 5) [38]. Scrambling of the heparin-binding sequence presented on the PA diminished the observed angiogenic effect in a tube formation assay using endothelial cells [37]. Since the scrambled version of the PA and HBPA had similar association constants with heparin, the difference in bioactivity was attributed to a slower off-rate for the interaction between heparin and HBPA, stabilizing the protein from enzymatic degradation and leading to more efficient growth factor signaling.

Figure 5.

In vivo angiogenesis assay. Rat cornea photographs 10 days after the placement of various materials at the site indicated by the black arrow. (A)Heparin-nucleated PA nanofiber networks with growth factors show extensive neovascularization. Controls of collagen, heparin, and growth factors (B) and collagen with growth factors (C) show some neovascularization. Heparin with growth factors (D), and collagen with heparin. The bar graph (F) contains values for the average and maximum length of new blood vessels and the area of corneal neovascularization. A 100% value in the area measurement indicates that the cornea is completely covered, and a 100% value in the length parameters indicates that the new vessels are as long as the diameter of the cornea (bars are 95% confidence levels, * p < 0.05 when PA-heparin gel was compared to collagen gel with growth factors, ** p < 0.005 when PA-heparin gel with growth factors was compared to all of the other controls). PA nanofibers with heparin, PA solution with growth factors, and growth factors alone did not result in measurable neovascularization (values not shown in graph). Reprinted with permission from Kanya Rajangam et. al., Heparin binding nanostructures to promote the growth of blood vessels, Nano Letters, 2006; 6(9), 2086–2090.

Assessing the tissue reaction to these HBPA-heparan sulfate nanofiber gels using a mouse subcutaneous implantation model and percutaneous injection revealed excellent biocompatibility and also demonstrated retention of the material for at least 30 days in vivo [39]. The more exciting finding from this study was the discovery that, as the material was biodegraded, it was quickly remodeled into a well-vascularized connective tissue without the addition of any exogenous growth factors. Dynamic analysis of the tissue reaction using a skinfold chamber model demonstrated no adverse effects of the material on the microcirculation, and also confirmed the biocompatibility and vascularization seen in the subcutaneous model. This points to the potential to use the HBPA system for the healing of chronic wounds or to enhance efficacy of skin grafts, as both of these could benefit from the extensive granulation tissue observed.

3.3 Islet Transplantation

Treatments currently being explored for type I diabetes mellitus, a condition that results from autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing β-cells, involve transplantation of donor islets, the pancreatic cell aggregates that contain β-cells. The efficacy of this strategy is limited by poor islet viability and engraftment following transplant [40]. To improve islet engraftment, the angiogenic potential of the HBPA-heparin nanofiber system was explored in vivo to deliver donor islets into a diabetic mouse model [41]. Currently, donor islets are transplanted into the liver due to its high degree of vasculature. HBPA, combined with FGF-2 and VEGF, was found to significantly enhance vasculature in the omentum, an intraperitoneal fat mass that in principle would be a more desirable site for transplantation of islets. When islets were transplanted with HBPA-heparin nanofiber networks and angiogenic growth factors into the omentum, the cure percentage of diabetic mice restored to a normoglycemic state was significantly enhanced relative to untreated diabetic mice. This was not the case for the administration of islets with HBPA-heparin alone or with growth factors alone.

3.4 NOx Release for Neointimal Hyperplasia

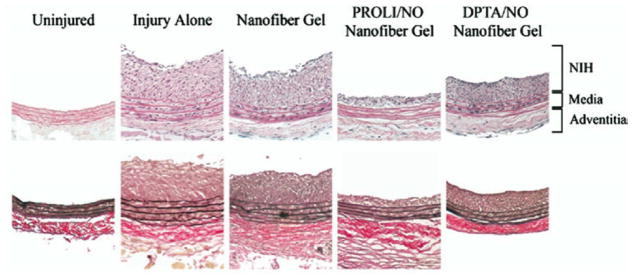

Atherosclerosis affects nearly 80 million people in the US alone, and while there are a variety of possible treatment modalities such as angiogplasty and stenting, these procedures have limited efficacy due in large part to secondary complications of neointimal hyperplasia. Nitric oxide has long been recognized as a possible solution to prevent the onset of these secondary complications. Peptide amphiphiles presenting heparin were mixed with diazeniumdiolate nitric oxide donors to prepare nitric oxide releasing nanofiber gels [42]. Mixing with the nanofiber gel extended the release of nitric oxide over a period of 4 days in vitro, significant considering the half-life for release from the small molecules alone is on the order of seconds to hours. This prolonged release profile suggests advantages for the delivery of nitric oxide in the treatment of neointimal hyperplasia, further supported by demonstrating the ability to decrease smooth muscle cell proliferation while leading to greater cells death in vitro. When applied to a rat carotid artery balloon injury model, the nitric oxide releasing PA nanofiber gels led to a reduction in neointimal hyperplasia by up to 77% compared to controls and also limited inflammation in the injury site (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Rat carotid artery sections from uninjured, injury alone, nanofiber gel, PROLI/NO nanofiber gel, and DPTA/NO nanofiber gel animals euthanized at 14 days (n=6 per group). Displayed are representative sections (100x original magnification)from each group using routine staining with hematoxylin and eosin (top) and Verhoff-van Gieson (bottom). PROLI/NO and DPTA/NO are two small molecule diazeniumdiolate nitric oxide donors that were mixed with the PA nanofiber gel. Reprinted with permission from Muneera Kapadia et. al., Nitric oxide and nanotechnology: A novel approach to inhibit neointimal hyperplasia, Journal of Vascular Surgery, 2008 47(1), 173–182.

3.5 Hard tissue replacement and regeneration

Regeneration or replacement of hard tissue in the body has proven to be a challenge in part due to the mechanical properties of these tissues. One possible approach has focused on replacement of the tissue with a permanent metal implant. While traditional metal implants made from titanium and its alloys possess good mechanical properties and reasonable biocompatibility, these materials do not incorporate a bioactive component. PA nanofibers were explored as a means to functionalize these metal implants to enhance bioactivity and prompt tissue growth around the implant to assist in long-term implant fixation. A nickel-titanium (NiTi) alloy that is frequently used for stents, bone plates, and artificial joints was modified through covalent attachment of PA nanofibers using standard silanization and cross-linking chemistry [43, 44]. Modifying the metal with RGDS-presenting PAs led to a significant increase in the number of adhered pre-osteoblastic cells cultured in vitro, while cells did not attach to the non-functionalized NiTi. Porous titanium implants are frequently used to encourage tissue ingrowth and assist with implant fixation. RGDS-presenting PA nanofiber gels have been prepared within the pores of such scaffolds [45, 46]. The PA molecules were triggered to gel by the introduction of counterions within the interconnected pores of titanium foam. Pre-osteoblastic cells seeded within these PA-titanium foam hybrids were viable, proliferative, and exhibited signs of osteogenic differentiation. These results point the potential to use these PA-functionalized metal constructs in vivo, and a pilot study in a rat defect model has been undertaken [45].

Enamel, the outermost coating of vertebrate teeth and the hardest tissue in the body, remains a formidable challenge in regenerative medicine. The ameloblast cells responsible for the production of enamel during development subsequently apoptose, preventing enamel regeneration during adulthood. Branched RGDS-presenting PA nanofibers have been used as scaffolds for ameloblast-like cells and primary enamel organ epithelial (EOE) cells that initiate the process of enamel formation [47]. When treated with branched RGDS PA nanofibers in vitro, these cells showed an enhancement in proliferation and increased their expression of amelogenin and ameloblastin, two proteins secreted by ameloblasts during enamel formation. In an organ culture model, the RGDS PA was injected into embryonic mouse incisors. Again, EOE proliferation and ameloblastic differentiation was observed, evidenced by an increased expression of enamel specific proteins.

Hartgerink and colleagues have also used PAs as an in vitro scaffold for dental stem cells. They found that stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth proliferate and secrete a soft collagen matrix while encapsulated within the PA while dental pulp stem cells differentiate into an osteoblast-like phenotype and deposit mineral when encapsulated within the gel [48]. They propose that this PA system combined with dental stem cells could be used as a treatment for dental caries, enabling regeneration of both soft and mineralized dental tissue.

3.6 Templating biomineral

The ability to template biologically relevant material holds great promise for the treatment of bone loss, osteoporosis, or dental caries. The surface of PA nanofibers can be customized to create templates for this inorganic mineralization. The first PAs designed by our group incorporated phosphorylated serine residues with the aim of templating biomimetic hydroxyapatite crystals similar to those found in bone and dentine [2, 49]. Phosphorylated serine is a non-standard amino acid that is found frequently in proteins that template calcium phosphate in mineralized tissues [50–52]. Using this amino acid to template mineral produced hydroxyapatite with the crystallographic axis aligned with the length of PA nanofibers, mimicking the crystallographic orientation of hydroxyapatite in bone with respect to the long axis of collagen fibers. The enzyme alkaline phosphatase was later determined to be critically important for biomineralization of PA networks in three dimensions [53]. Temporal control provided by enzymatically harvested phosphate ions enables phosphorylated serine-presenting PA nanofibers to nucleate hydroxyapatite on their surface which provides spatial control for biomineralization to occur on the PA nanofiber networks.

3.7 MRI contrast agents

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one of medicine’s most powerful diagnostic techniques, providing three-dimensional structures of living tissue at near cellular resolution. However, this technique is currently limited by the timecourse and circulation time of the small molecule contrast agents used for imaging. Previously, we covalently attached a derivative of a molecule (DOTA) that chelates gadolinium to PA molecules in order to increase the relaxivity of the MR agent [54, 55]. These MR agent-conjugated PA molecules self-assemble into cylindrical nanofibers or spheres under aqueous conditions. The rotational correlation time of the MR agent was increased following self-assembly into nanostructures, suggesting enhanced relaxivity. It was also found that the molecule’s relaxivity and imaging properties can be influenced by the position on the PA molecule that the DOTA derivative is attached, showing enhancement when the DOTA/Gd(III) complex was closer to the hydrophobic region. Nanofiber networks comprised of these MR agent-conjugated PAs can be imaged using MRI techniques [55]. Future work will examine these MRI-conjugated PA constructs in vivo in order to track the fate of an implanted PA nanofiber gel and also evaluate the efficacy of IV-administered PAs as a prolonged blood-pool contrast agent.

4. Other Self-Assembling Peptide Technology

4.1 β-Sheet Peptides

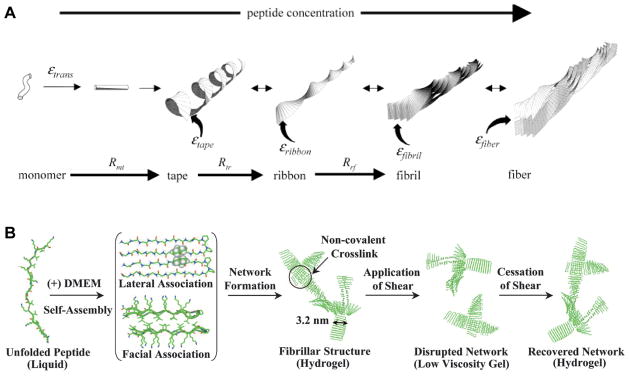

Previous work by Aggeli and colleagues demonstrated the importance of the β-sheet structural motif in peptide supramolecular chemistry, exploiting this non-covalent interaction to prepare self-assembling oligopeptides that form semi-flexible nanotapes [56]. This assembly strategy is primarily governed by hydrogen bonding along the peptide backbone and interactions between specific amino acid side-chain constituents. These β-sheet peptide nanotapes can further assemble into a hierarchy of supramolecular morphologies (Figure 7A), including twisted ribbons (double tapes), fibrils (twisted stacks of ribbons), and fibers (entwined fibrils) by changing pH, monomer concentration, amino acid sequence/charge, or the intrinsic chirality of the precursor oligopeptide [57, 58]. These structures can entangle into viscoelastic networks in both aqueous and organic conditions, depending on the selection of amino acids, and can form hydrogels or organogels, respectively, when a critical concentration is reached [58]. Mixing aqueous solutions of cationic and anionic β-sheet peptides with complementary acidic and basic side-chains results in spontaneous self-assembly of fibrillar networks and nematic hydrogels that are robust to variations in pH and peptide concentration [59].

Figure 7.

(A) The hierarchical equilibrium configurations of self-assembly of β-sheet forming peptides, which assemble to form tapes, ribbons, fibrils and fibers depending on parameters such as peptide concentration, solution pH, or sequence/charge of the precursor monomer. Reprinted with permission from Amalia Aggeli et. al., pH as a Trigger of Peptide β-sheet Self-Assembly and Reversible Switching between Nematic Iotropic Phases, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2003 125(3), 9619–9628. (B) The self-assembly of β-hairpin peptides through charge screening in physiologic media (DMEM) allows for the formation of self-healing hydrogels that can be syringe-delivered. Reprinted from Lisa Haines-Butterick et. al., Controlling hydrogelation kinetics by peptide design for three-dimensional encapsulation and injectable delivery of cells, 2007 104(19), 7791–7796 Copyright 2007 National Academy of Sciences USA.

In the context of regenerative medicine, these β-sheet peptide nanostructures have been evaluated for the treatment of enamel decay [60]. Extracted human premolar teeth containing caries-like lesions were exposed in vitro to multiple cycles of demineralizing (acidic conditions) and remineralizing (neutral pH conditions) solutions. Applying an anionic peptide designed for βsheet assembly to the defects both decreased demineralization during exposure to acid and increased remineralization at neutral pH, resulting in significant gains of net mineral within the lesions over the 5 day study. The peptide gels also nucleated the formation of de novo hydroxyapatite when incubated in mineralizing solutions [60].

In another application towards regenerative medicine, these peptides were evaluated as an injectable joint lubricant for the treatment of osteoarthritis [61]. An array of peptides were designed with variations in charge and hydrophilicity to determine which supramolecular assembles would have properties similar to those of hyaluronic acid (HA), the main contributor to the lubricating properties of synovial fluid. One such β-sheet peptide with molecular, mesoscopic, and rheological properties most closely matching those of HA performed similarly in healthy static and dynamic friction tests; however it did not perform as well as HA when friction tests were performed with damaged cartilage [61]. One advantage of these systems is that they assemble in situ, but have very low viscosity prior to and during injection, making them easier to handle than the highly viscous HA. This preliminary work points to the possibility of using self-assembled peptides as a synthetic joint lubricant in the treatment of degenerative osteoarthritis.

4.2 β-Hairpin Peptides

Another peptide design that captures the self-assembling potential afforded by the β-sheet is prepared from monomers of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues, lysine and valine, respectively, flanking an intermittent tetrapetide designed to mimic a Type II’ β-turn, termed a β-hairpin peptide [62–67]. These peptides are designed to be hydrated in pure water, adopting a random coil conformation. In charge screening conditions, such as in the presence of ions in physiologic fluid or through transitions to basic pH, the electrostatic repulsion between charged residues is diminished, allowing the peptide to fold into its β-hairpin conformation. This molecular folding produces a monomer with extensive intermolecular hydrogen bond formation and with one face of the β-hairpin exposing the hydrophobic valine residues while the other has exposed hydrophilic lysines, organization that results from the alternating sequence in the unfolded molecule. Subsequent self-assembly of the individual hairpins due to hydrophobic interactions and intramolecular hydrogen bond formation leads to a highly entangled hydrogel (Figure 7B). In cases where pH is increased to induce hydrogel formation, unfolding of the hairpins and dissociation of the hydrogel can be triggered by lowering the pH below the pKa of the lysine side chains, restoring electrostatic repulsion [62]. If a lysine residue is replaced by a negatively charged glutamic acid, the overall peptide charge is decreased and the peptide can be more easily screened, resulting in much faster self-assembly [67]. The changes in the hydrogelation kinetics were found to significantly improve the homogenous distribution of encapsulated cells within these self-assembling gels, an important characteristic for an injectable cell scaffold material. Studies in vitro have found that these β-hairpin hydrogels can support survival, adhesion, and migration of fibroblasts [65, 67, 68], and can be used to encapsulate mesenchymal stem cells and hepatocytes [67]. These gels have also been found to have inherent antimicrobial properties; showing selective toxicity to bacterial cells compared to mammalian cells [69].

4.3 Ionic Self-Complementary Peptides

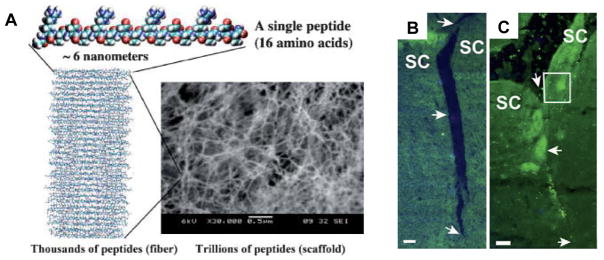

Another class of self-assembling peptide molecules developed by Zhang and colleagues was designed based on β-sheet-rich proteins from nature, prepared from sequences of alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues [70]. The first such molecules were based on a segment of the yeast protein, Zuotin, and formed an insoluble macroscopic membrane [71, 72]. Variations in peptide sequence, while maintaining the alternating ionic hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues, have utilized mixed charged residues, such as repeat units of Arg-Ala-Asp-Ala (RADA) or repeat units of RARADADA. These peptide sequences demonstrate stable fibrillar nanostructure self-assembly driven by spontaneous β-sheet formation and complementary ionic interactions between the oppositely charged ionic residues (Figure 8A). With the addition of counterions or physiological media, these fibrillar nanostructures form entangled hydrogels [72, 73]. Other studies have found that oligopeptide length [74] and side-chain hydrophobicity [75] are important variables that affect both the peptide self-assembly and the mechanical properties of the resulting gel.

Figure 8.

(A) Ionic self-complimentary peptides self-assemble by hydrogen bonding into fibers consisting of thousands of peptides which further entangle into scaffolds that are ~99.5% water and ~0.5% peptide. Reprinted with permission from Fabrizio Gelain et. al., Designer self-assembling peptide scaffolds for 3-d tissue cell cultures and regenerative medicine, Macromolecular Bioscience, 2007 7(5), 544–551. (B, C) View of the superior colliculus (SC) 30 days following the formation of a tissue gap by deep transection of the optic tract in the hamster midbrain following a control treatment with saline (B) or treatment with ionic self-complimentary peptide nanofibers (C). With nanofiber treatment, the site of the lesion has healed and axons have grown through the treated area and reached the caudal part of the SC. Reprinted from Rutledge G. Ellis-Behnke et. al., Nano neuro knitting: Peptide nanofiber scaffold for brain repair and axon regeneration with functional return of vision,, 2006 103(13), 5054–5059 Copyright 2006 National Academy of Sciences USA.

These ionic self-complimentary peptides have advanced quite far towards being applied as therapies for regenerative medicine. With respect to in vitro evaluation, there has been several studies examining the ability of these self-assembled scaffolds to support cell attachment [72], to promote the survival, proliferation, differentiation and neurite growth for neural cells [73, 76], to promote the differentiation of liver progenitor cells into hepatocyte spheroids [77], to serve as scaffolds for human endothelial cells [78–81], as well as scaffolds for chrondrocytes [82] and for ostegenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells [83, 84].

Several studies have been done in vivo examining these peptide scaffolds for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, focusing on the delivery of growth factors and the recruitment of progenitor cells [85–88]. For the treatment of myocardial infarction, the peptide scaffolds were injected into rat myocardium and were found to enhance the recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells and vascular smooth muscle cells into the injection site, appearing to form functional vascular structures [85]. Nanofibers displaying biotin were subsequently used to deliver streptavidin-linked insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) along with neonatal cardiomyocytes and this therapy was shown to significantly improve systolic function after myocardial infarction [86]. Other studies evaluated the delivery of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) using these self-assembling peptide nanofibers in a rat myocardial infarct model, demonstrating decreased infarct size corresponding to reduced cardiomyocyte death and functional improvement in cardiac performance after infarction [87, 88].

In applications towards regeneration of the central nervous system, these peptide scaffolds were evaluated in an acute model severing the optic tract within a hamster brain, demonstrating the ability to prompt axon regeneration and the reconnection of target brain tissues, eventually resulting in restored vision (Figure 8B, 8C) [89]. These scaffolds, when implanted with neural progenitor cells and Schwann cell into a transected dorsal column of a rat spinal cord, also promoted cell migration, blood vessel growth, and axonal elongation through the injury site, demonstrating the potential to perhaps use these materials to reverse spinal cord injury [90].

4.4 Aromatic-terminated Peptides

An emerging class of self-assembling peptides use conjugated aromatic groups such as carbobenxyloxy, naphthalene, or fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) on the N-terminal end of di- and tri-peptides, demonstrating the formation of very stable, highly tunable hydrogels [91, 92]. Frequently, these aromatic groups have been attached to a di-phenylalanine peptide, and gel formation from these molecules can be induced by altering pH [91] or by incorporating domains which are sensitive to enzymatic activity [93]. Assembly of these small molecules occurs through two simultaneous attractive forces, antiparallel β-sheet formation between the oligopeptide domain and π-π stacking of the aromatic rings [94]. A number of these sheets then twist together to form nanotubes. Studies examining these peptide hydrogels in vitro indicate that these materials can support chondrocyte survival and proliferation in both two and three dimensions [91, 95]. Adding chemical functionalities to these Fmoc-peptides made these materials selective to the culture of different types of cells and affected the mechanical properties of the formed hydrogel [96].

5. Future Prospects

We have described here recent progress in the development of peptide-based nanotechnology as a novel therapeutic strategy for regenerative medicine. There remains work to be done in developing this technology. The field so far has involved the design of peptidic molecules for assembly into nanostructures by different mechanisms, yielding great variability in the degree of precision in supramolecular structure. Precision in shape and dimensions of the peptide nanostructures needs to be part of future work in the field. It is also important to multiplex biological functions, either through their integration into single nanostructures or by creating arrays of different nanostructures. Designs could also include incorporation of extracellular and intracellular bioactivity targets in order to directly control signal transduction pathways. The use of bioactive peptide nanostructures in hierarchical structures with sophisticated function is also an important area for future growth. This could yield innovative constructs for controlled three dimensional cell culture, particularly for stem cells, or novel methods for cell transplantation or cell delivery. Another fertile direction is the design of peptide nanostructures that can be delivered systemically and targeted to specific compartments of the body to promote regenerative processes, including crossing of the blood-brain barrier.

While the work we have highlighted is rich in the development of the mentioned technologies, their translation into disease therapeutics is just beginning. This is evident by the recent number of small animal studies that are being undertaken by our group and others. If this technology is to advance as a therapeutic option for treating human ailments, studies like these are essential. We have described some very promising in vivo data using peptide amphiphiles as a therapy for spinal cord injury, islet transplantation, prevention of neointimal hyperplasia, and induction of angiogenesis. Ongoing work will evaluate these PAs in a variety of other disease models, from cancer to myocardial infarction to Parkinson’s disease, and we hope to continue to show therapeutic efficacy in these evaluated models. In addition, Zhang and colleagues have extensively evaluated their ionic self-complimentary peptides in a number of small animal models. The results from the in vivo studies described in this review are encouraging for the future use of peptide-based nanotechnology as a therapy for humans, though hurdles remain. However, we hope that the efficacy observed by these preliminarily evaluated technologies, combined with the continued development of new technologies, will lead to a new therapeutic niche based on self-assembling peptides that could be a realistic therapeutic option for humans in the coming years.

References

- 1.Gurtner GC, Callaghan MJ, Longaker MT. Progress and potential for regenerative medicine. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:299–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.082405.095329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison BS, Atala A. Carbon nanotube applications for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:344–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran PA, Zhang L, Webster TJ. Carbon nanofibers and carbon nanotubes in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamieson T, Bakhshi R, Petrova D, Pocock R, Imani M, Seifalian AM. Biological applications of quantum dots. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4717–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillies ER, Frechet JM. Dendrimers and dendritic polymers in drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CC, MacKay JA, Frechet JM, Szoka FC. Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer LC, Stupp SI. Molecular Self-Assembly into One-Dimensional Nanostructures. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41:1674–84. doi: 10.1021/ar8000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer LC, Velichko YS, de la Cruz MO, Stupp SI. Supramolecular self-assembly codes for functional structures. Philos Trans R Soc A-Math Phys Eng Sci. 2007;365:1417–33. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2007.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stupp SI, Pralle MU, Tew GN, Li LM, Sayar M, Zubarev ER. Self-assembly of organic nano-objects into functional materials. MRS Bull. 2000;25:42–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartgerink JD, Zubarev ER, Stupp SI. Supramolecular one-dimensional objects. Curr Opin Solid State Mat Sci. 2001;5:355–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang JJ, Iyer SN, Li LS, Claussen R, Harrington DA, Stupp SI. Self-assembling biomaterials: Liquid crystal phases of cholesteryl oligo(L-lactic acid) and their interactions with cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152667399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klok HA, Hwang JJ, Hartgerink JD, Stupp SI. Self-assembling biomaterials: L-lysine-dendron-substituted cholesteryl-(L-lactic acid)(n)over-bar. Macromolecules. 2002;35:6101–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klok HA, Hwang JJ, Iyer SN, Stupp SI. Cholesteryl-(L-lactic acid)((n)over-bar) building blocks for self-assembling biomaterials. Macromolecules. 2002;35:746–59. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Peptide-amphiphile nanofibers: A versatile scaffold for the preparation of self-assembling materials. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5133–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072699999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva GA, Czeisler C, Niece KL, Beniash E, Harrington DA, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Selective differentiation of neural progenitor cells by high-epitope density nanofibers. Science. 2004;303:1352–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1093783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui H, Muraoka T, Cheetham AG, Stupp SI. Self-Assembly of Giant Peptide Nanobelts. Nano Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1021/nl802813f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velichko YS, Stupp SI, de la Cruz MO. Molecular simulation study of peptide amphiphile self-assembly. J Phys Chem B. 2008:2326–34. doi: 10.1021/jp074420n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beniash E, Hartgerink JD, Storrie H, Stendahl JC, Stupp SI. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofiber matrices for cell entrapment. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stendahl JC, Rao MS, Guler MO, Stupp SI. Intermolecular forces in the self-assembly of peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Advanced Functional Materials. 2006;16:499–508. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beniash E, Hartgerink JD, Storrie H, Stendahl JC, Stupp SI. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofiber matrices for cell entrapment. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niece KL, Czeisler C, Sahni V, Tysseling-Mattiace V, Pashuck ET, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Modification of gelation kinetics in bioactive peptide amphiphiles. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4501–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guler MO, Hsu L, Soukasene S, Harrington DA, Hulvat JF, Stupp SI. Presentation of RGDS epitopes on self-assembled nanofibers of branched peptide amphiphiles. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1855–63. doi: 10.1021/bm060161g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storrie H, Guler MO, Abu-Amara SN, Volberg T, Rao M, Geiger B, Stupp SI. Supramolecular crafting of cell adhesion. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4608–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muraoka T, Koh CY, Cui HG, Stupp SI. Light-Triggered Bioactivity in Three Dimensions. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2009;48:5946–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webber MJ, Tongers J, Renault MA, Roncalli JG, Losordo DW, Stupp SI. Development of bioactive peptide amphiphiles for therapeutic cell delivery. Acta Biomater. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington DA, Cheng EY, Guler MO, Lee LK, Donovan JL, Claussen RC, Stupp SI. Branched peptide-amphiphiles as self-assembling coatings for tissue engineering scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2006;78A:157–67. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mata A, Hsu L, Capito R, Aparicio C, Henrikson K, Stupp SI. Micropatterning of bioactive self-assembling gels. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1228–36. doi: 10.1039/b819002j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung AM, Stupp SI. Understanding factors affecting alignment of self-assembling nanofibers patterned by sonication-assisted solution embossing. Langmuir. 2009;25:7084–9. doi: 10.1021/la900149v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hung AM, Stupp SI. Simultaneous self-assembly, orientation, and patterning of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers by soft lithography. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1165–71. doi: 10.1021/nl062835z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Capito RM, Azevedo HS, Velichko YS, Mata A, Stupp SI. Self-assembly of large and small molecules into hierarchically ordered sacs and membranes. Science. 2008;319:1812–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1154586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tysseling-Mattiace VM, Sahni V, Niece KL, et al. Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit glial scar formation and promote axon elongation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3814–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folkman J. Fundamental concepts of the angiogenic process. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:643–51. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folkman J, Klagsbrun M. Angiogenic factors. Science. 1987;235:442–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2432664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behanna HA, Rajangam K, Stupp SI. Modulation of fluorescence through coassembly of molecules in organic nanostructures. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:321–7. doi: 10.1021/ja062415b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajangam K, Arnold MS, Rocco MA, Stupp SI. Peptide amphiphile nanostructure-heparin interactions and their relationship to bioactivity. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajangam K, Behanna HA, Hui MJ, Han XQ, Hulvat JF, Lomasney JW, Stupp SI. Heparin binding nanostructures to promote growth of blood vessels. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2086–90. doi: 10.1021/nl0613555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghanaati S, Webber MJ, Unger RE, et al. Dynamic in vivo biocompatibility of angiogenic peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6202–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson RP. Islet transplantation as a treatment for diabetes - a work in progress. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:694–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stendahl JC, Wang LJ, Chow LW, Kaufman DB, Stupp SI. Growth factor delivery from self-assembling nanofibers to facilitate islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;86:478–81. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181806d9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kapadia MR, Chow LW, Tsihlis ND, et al. Nitric oxide and nanotechnology: A novel approach to inhibit neointimal hyperplasia. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:173–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sargeant TD, Rao MS, Koh CY, Stupp SI. Covalent functionalization of NiTi surfaces with bioactive peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1085–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bansiddhi A, Sargeant TD, Stupp SI, Dunand DC. Porous NiTi for bone implants: A review. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:773–82. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sargeant TD, Guler MO, Oppenheimer SM, Mata A, Satcher RL, Dunand DC, Stupp SI. Hybrid bone implants: Self-assembly of peptide amphiphile nanofibers within porous titanium. Biomaterials. 2008;29:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sargeant TD, Oppenheimer SM, Dunand DC, Stupp SI. Titanium foam-bioactive nanofiber hybrids for bone regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:455–62. doi: 10.1002/term.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang Z, Sargeant TD, Hulvat JF, et al. Bioactive Nanofibers Instruct Cells to Proliferate and Differentiate During Enamel Regeneration. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1995–2006. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galler KM, Cavender A, Yuwono V, et al. Self-Assembling Peptide Amphiphile Nanofibers as a Scaffold for Dental Stem Cells. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2008;14:2051–8. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer LC, Newcomb CJ, Kaltz SR, Spoerke ED, Stupp SI. Biomimetic Systems for Hydroxyapatite Mineralization Inspired By Bone and Enamel. Chem Rev. 2008:4754–83. doi: 10.1021/cr8004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Addadi L, Weiner S. Interactions between Acidic Proteins and Crystals -Stereochemical Requirements in Biomineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4110–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.George A, Bannon L, Sabsay B, et al. The carboxyl-terminal domain of phosphophoryn contains unique extended triplet amino acid repeat sequences forming ordered carboxyl-phosphate interaction ridges that may be essential in the biomineralization process. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:32869–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer LC, Newcomb CJ, Kaltz SR, Spoerke ED, Stupp SI. Biomimetic Systems for Hydroxyapatite Mineralization Inspired By Bone and Enamel. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4754–83. doi: 10.1021/cr8004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spoerke ED, Anthony SG, Stupp SI. Enzyme Directed Templating of Artificial Bone Mineral. Adv Mater. 2009;21:425-+. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bull SR, Guler MO, Bras RE, Meade TJ, Stupp SI. Self-assembled peptide amphiphile nanofibers conjugated to MRI contrast agents. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1–4. doi: 10.1021/nl0484898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bull SR, Guler MO, Bras RE, Venkatasubramanian PN, Stupp SI, Meade TJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of self-assembled biomaterial scaffolds. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:1343–8. doi: 10.1021/bc050153h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aggeli A, Bell M, Boden N, et al. Responsive gels formed by the spontaneous self-assembly of peptides into polymeric beta-sheet tapes. Nature. 1997;386:259–62. doi: 10.1038/386259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aggeli A, Nyrkova IA, Bell M, et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of chiral rod-like molecules as a model for peptide beta -sheet tapes, ribbons, fibrils, and fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11857–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191250198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aggeli A, Bell M, Carrick LM, et al. pH as a trigger of peptide beta-sheet self-assembly and reversible switching between nematic and isotropic phases. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9619–28. doi: 10.1021/ja021047i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aggeli A, Bell M, Boden N, Carrick LM, Strong AE. Self-assembling peptide polyelectrolyte beta-sheet complexes form nematic hydrogels. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:5603–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kirkham J, Firth A, Vernals D, et al. Self-assembling peptide scaffolds promote enamel remineralization. J Dent Res. 2007;86:426–30. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bell CJ, Carrick LM, Katta J, et al. Self-assembling peptides as injectable lubricants for osteoarthritis. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2006;78:236–46. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schneider JP, Pochan DJ, Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Pakstis L, Kretsinger J. Responsive hydrogels from the intramolecular folding and self-assembly of a designed peptide. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:15030–7. doi: 10.1021/ja027993g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pochan DJ, Schneider JP, Kretsinger J, Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Haines L. Thermally reversible hydrogels via intramolecular folding and consequent self-assembly of a de novo designed peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11802–3. doi: 10.1021/ja0353154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Semiflexible chain networks formed via self-assembly of beta-hairpin molecules. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:268106. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.268106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haines LA, Rajagopal K, Ozbas B, Salick DA, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Light-activated hydrogel formation via the triggered folding and self-assembly of a designed peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17025–9. doi: 10.1021/ja054719o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lamm MS, Rajagopal K, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Laminated morphology of nontwisting beta-sheet fibrils constructed via peptide self-assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16692–700. doi: 10.1021/ja054721f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haines-Butterick L, Rajagopal K, Branco M, et al. Controlling hydrogelation kinetics by peptide design for three-dimensional encapsulation and injectable delivery of cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:7791–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701980104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kretsinger JK, Haines LA, Ozbas B, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Cytocompatibility of self-assembled beta-hairpin peptide hydrogel surfaces. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5177–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salick DA, Kretsinger JK, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Inherent Antibacterial Activity of a Peptide-Based beta-Hairpin Hydrogel. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:14793–9. doi: 10.1021/ja076300z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gelain F, Horii A, Zhang S. Designer self-assembling peptide scaffolds for 3-d tissue cell cultures and regenerative medicine. Macromol Biosci. 2007;7:544–51. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200700033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang S, Holmes T, Lockshin C, Rich A. Spontaneous assembly of a self-complementary oligopeptide to form a stable macroscopic membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3334–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang S, Holmes TC, DiPersio CM, Hynes RO, Su X, Rich A. Self-complementary oligopeptide matrices support mammalian cell attachment. Biomaterials. 1995;16:1385–93. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)96874-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holmes TC, de Lacalle S, Su X, Liu G, Rich A, Zhang S. Extensive neurite outgrowth and active synapse formation on self-assembling peptide scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6728–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Caplan MR, Schwartzfarb EM, Zhang S, Kamm RD, Lauffenburger DA. Effects of systematic variation of amino acid sequence on the mechanical properties of a self-assembling, oligopeptide biomaterial. Journal of biomaterials science. 2002;13:225–36. doi: 10.1163/156856202320176493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caplan MR, Schwartzfarb EM, Zhang S, Kamm RD, Lauffenburger DA. Control of self-assembling oligopeptide matrix formation through systematic variation of amino acid sequence. Biomaterials. 2002;23:219–27. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Semino CE, Kasahara J, Hayashi Y, Zhang S. Entrapment of migrating hippocampal neural cells in three-dimensional peptide nanofiber scaffold. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:643–55. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Semino CE, Merok JR, Crane GG, Panagiotakos G, Zhang S. Functional differentiation of hepatocyte-like spheroid structures from putative liver progenitor cells in three-dimensional peptide scaffolds. Differentiation. 2003;71:262–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.7104503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Genove E, Shen C, Zhang S, Semino CE. The effect of functionalized self-assembling peptide scaffolds on human aortic endothelial cell function. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3341–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Narmoneva DA, Oni O, Sieminski AL, Zhang S, Gertler JP, Kamm RD, Lee RT. Self-assembling short oligopeptides and the promotion of angiogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4837–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sieminski AL, Semino CE, Gong H, Kamm RD. Primary sequence of ionic self-assembling peptide gels affects endothelial cell adhesion and capillary morphogenesis. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87:494–504. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sieminski AL, Was AS, Kim G, Gong H, Kamm RD. The stiffness of three-dimensional ionic self-assembling peptide gels affects the extent of capillary-like network formation. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;49:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kisiday J, Jin M, Kurz B, Hung H, Semino C, Zhang S, Grodzinsky AJ. Self-assembling peptide hydrogel fosters chondrocyte extracellular matrix production and cell division: implications for cartilage tissue repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9996–10001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142309999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garreta E, Genove E, Borros S, Semino CE. Osteogenic differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells and mouse embryonic fibroblasts in a three-dimensional self-assembling peptide scaffold. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2215–27. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garreta E, Gasset D, Semino C, Borros S. Fabrication of a three-dimensional nanostructured biomaterial for tissue engineering of bone. Biomol Eng. 2007;24:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davis ME, Motion JP, Narmoneva DA, et al. Injectable self-assembling peptide nanofibers create intramyocardial microenvironments for endothelial cells. Circulation. 2005;111:442–50. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153847.47301.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Davis ME, Hsieh PC, Takahashi T, et al. Local myocardial insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) delivery with biotinylated peptide nanofibers improves cell therapy for myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8155–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602877103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hsieh PC, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Cruz FU, Lee RT. Local controlled intramyocardial delivery of platelet-derived growth factor improves postinfarction ventricular function without pulmonary toxicity. Circulation. 2006;114:637–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.639831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hsieh PC, Davis ME, Gannon J, MacGillivray C, Lee RT. Controlled delivery of PDGF-BB for myocardial protection using injectable self-assembling peptide nanofibers. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:237–48. doi: 10.1172/JCI25878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ellis-Behnke RG, Liang YX, You SW, Tay DK, Zhang S, So KF, Schneider GE. Nano neuro knitting: peptide nanofiber scaffold for brain repair and axon regeneration with functional return of vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5054–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600559103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guo J, Su H, Zeng Y, et al. Reknitting the injured spinal cord by self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold. Nanomedicine. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jayawarna V, Smith A, Gough JE, Ulijn RV. Three-dimensional cell culture of chondrocytes on modified di-phenylaianine scaffolds. Biochem Soc T. 2007;35:535–7. doi: 10.1042/BST0350535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang Z, Gu H, Zhang Y, Wang L, Xu B. Small molecule hydrogels based on a class of antiinflammatory agents. Chem Commun (Camb) 2004:208–9. doi: 10.1039/b310574a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toledano S, Williams RJ, Jayawarna V, Ulijn RV. Enzyme-triggered self-assembly of peptide hydrogels via reversed hydrolysis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:1070–1. doi: 10.1021/ja056549l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Smith AM, Williams RJ, Tang C, et al. Fmoc-Diphenylalanine self assembles to a hydrogel via a novel architecture based on pi-pi interlocked beta-sheets. Adv Mater. 2008;20:37-+. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jayawarna V, Ali M, Jowitt TA, Miller AE, Saiani A, Gough JE, Ulijn RV. Nanostructured hydrogels for three-dimensional cell culture through self-assembly of fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-dipeptides. Adv Mater. 2006;18:611-+. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jayawarna V, Richardson SM, Hirst AR, Hodson NW, Saiani A, Gough JE, Ulijn RV. Introducing chemical functionality in Fmoc-peptide gels for cell culture. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:934–43. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]