Abstract

Background

Patients in step-down units are at higher risk for developing cardiorespiratory instability than are patients in general care areas. A triage tool is needed to identify at-risk patients who therefore require increased surveillance.

Objectives

To determine demographic (age, race, sex) and clinical (Charlson Comorbidity Index at admission, admitting diagnosis, care area of origin, admission service) differences between patients in step-down units who did and did not experience cardiorespiratory instability.

Methods

In a prospective longitudinal pilot study, 326 surgical-trauma patients had continuous monitoring of heart rate, respirations, and oxygen saturation and intermittent noninvasive measurement of blood pressure. Cardiorespiratory instability was defined as heart rate less than 40/min or greater than 140/min, respirations less than 8/min or greater than 36/min, oxygen saturation less than 85%, or blood pressure less than 80 or greater than 200 mm Hg systolic or greater than 110 mm Hg diastolic. Patients’ status was classified as unstable if their values crossed these thresholds even once during their stay.

Results

Cardiorespiratory instability occurred in 34% of patients. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was the only variable associated with instability conditions. Compared with patients with no comorbid conditions (50%), more patients with at least 1 comorbid condition (66%) experienced instability (P = .006). Each 1-unit increase in the Charlson Index increased the odds for cardiorespiratory instability by 1.17 (P = .03).

Conclusion

Although the relationship between Charlson Comorbidity Index and cardiorespiratory instability was weak, adding it to current surveillance systems might improve detection of instability.

Patients are placed in step-down units (SDUs) because their presumed risk for cardiorespiratory instability necessitates a higher level of monitoring than is available in general hospital units.1 Surveillance in SDUs generally consists of continuous but noninvasive monitoring of vital signs, a ratio of 1 nurse to 4 to 6 patients, and a requirement for face-to-face encounters between each patient and a caregiver approximately every 2 hours. This surveillance indeed is a step down from the level of care provided in an intensive care unit (ICU) with continuous invasive monitoring and a ratio of 1 nurse to 1 to 2 patients. However, the surveillance in an SDU can also be a step up from the level of surveillance provided on a general unit with intermittent monitoring of vital signs, a ratio of 1 nurse to 6 to 8 patients, and a requirement for face-to-face encounters between each patient and a caregiver approximately every 4 hours. Nevertheless, the level of surveillance as described has been used to define an SDU, regardless of a patient’s unit of origin.

Even though SDU patients have continuous noninvasive physiological monitoring, and the nurse to patient ratio is relatively high, detection of cardiorespiratory instability may still be suboptimal.2 We previously reported that a mean of 6.3 hours elapsed between the onset of a clinically apparent cardiorespiratory instability and the activation of our rapid response system (RRS), suggesting that cardiorespiratory instability is often undetected and prolonged in SDUs.1 Medical emergency teams (METs) are the response arm of the RRS and are meant to rapidly deploy critical-care-level support to the bedsides of patients outside the ICU whose cardiorespiratory status becomes unstable.3 Although some research4 suggests MET activation has no impact on fatal cardiopulmonary arrest, other research5 suggests that early interventions by the MET before cardiac arrest occurs can decrease mortality. The reason for this discrepancy might be a problem in the input arm of the RRS, namely, the inability to reliably detect events associated with cardiorespiratory instability and then activate the MET, a situation that happens in 23% of all instability conditions.6 The effectiveness of the RRS is highly dependent on the ability of bedside nurses to detect and recognize deterioration in a patient’s status and subsequently call the MET.7

Although some models and clinical algorithms have been developed to predict clinically unstable conditions in the ICU,8 these tools have not been adapted for SDU patients and have involved use of intermittent surveillance.9 In the study reported here, we used continuous surveillance of patients, a method that is more likely than intermittent surveillance to detect most of the events related to cardiorespiratory instability. In addition, including data about patients’ demographics and comorbid conditions might improve the specificity and the sensitivity of tools used to predict deterioration in a patient’s condition.7 However, the preexisting demographic and clinical characteristics associated with cardiorespiratory instability in SDU patients must be determined before such data can be used for prospective identification of patients who are at risk and therefore require increased surveillance.

In this study, we sought to determine differences in demographic (age, race, sex) and clinical (Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] at admission, admitting diagnosis, hospital unit of origin, admission service) characteristics between SDU patients who experienced cardiorespiratory instability during their SDU stay and patients who did not.

To date, no attempts have been made to examine the relationship between continuously gathered physiological data and preexisting demographic and clinical characteristics in predicting the occurrence of cardiorespiratory instability. Risk stratification at the time of admission to an SDU might help determine which patients need close surveillance. Variables predictive of risk could be used to improve the sen- sitivity and specificity of current surveillance systems and prediction tools.

Methods

A prospective longitudinal design was used in a pilot study of continuous monitoring of vital signs in a surgical-trauma SDU. The patient safety committee at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, approved the study as a quality improvement project to improve early detection of deterioration in a patient’s condition.

Sample and Setting

All patients (N = 326) admitted to a 24-bed adult surgical-trauma SDU at the medical center, a level I trauma center, during an 8-week period (November 2006 through January 2007) were included in the study. This SDU uses 3 central monitor banks, 1 in the nursing station, and 2 in the hallway. The bedside monitors (model M1204, Philips Medical Systems) provide continuous monitoring of 3-lead electrocardiography (ECG), heart rate, respirations, and blood oxygen saturation as determined by pulse oximetry (SpO2; model M1191B, Philips Medical Systems) and intermittent noninvasive monitoring of blood pressure at least every 2 hours. Nurse to patient ratios in the study unit ranged from 1 to 4 to 1 to 6 during the study period and depended on the number of patients in the unit and the acuity of the patients’ clinical conditions.

Definition of Cardiorespiratory Instability and Cohort Assignment

Continuously monitored vital signs were also recorded, and the data were downloaded from the bedside monitors. The data were analyzed to determine if any of the variables measured exceeded the thresholds used as criteria for cardiorespiratory instability4: heart rate less than 40/min or greater than 140/min, respirations less than 8/min or greater than 36/min, SpO2 less than 85%, and blood pressure less than 80 or more than 200 mm Hg systolic or greater than 110 mm Hg diastolic. Patients’ status was classified as unstable if their continuously monitored and recorded vital signs had ever—even once—exceeded any of the thresholds during the SDU stay and as stable if their continuously recorded vital signs had never exceeded any of the thresholds. For patients whose status was classified as unstable, the printed monitoring data-time plots were reviewed visually for all episodes associated with an unstable condition, and each event was judged as due to artifact (eg, sudden decrease in SpO2 with immediate return to baseline due to motion artifact) or to true physiological causes. Changes in the recorded vital signs due to artifacts were eliminated from the analyses by manual iteration of the primary time-series data. The reviews and decisions were conducted by 2 expert critical care physicians (M.R.P. and M.A.D.). After this review, patients were then classified as being in stable or unstable condition as defined previously.

Clinical and Demographic Variables

Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected from the patients’ clinical records and the hospital’s electronic databases. Race was dichotomized to white and nonwhite. CCI values were collected from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification designations by using the adaptation of Deyo et al.10 Each comorbid condition was individually coded as occurring dichotomously (yes or no) for each patient and then aggregated for a total CCI value. The CCI was further dichotomized into 2 categories; patients with no comorbid conditions were coded as CCI (0), and those with at least 1 comorbid condition as CCI (≥1). Unit of origin was categorized as ICU, SDU or general monitored unit, and nonmonitored general unit.

Statistical Analysis

Univariable analyses were used to compare age, race, sex, CCI, admitting diagnosis, unit of origin, and admission service between patients who experienced cardiorespiratory instability during their SDU stay and patients who did not. The Mann-Whitney test (used with continuous variables, such as age, that violate the assumptions of t tests), χ2 analysis, and Fisher exact tests were used in the univariable analysis. Multivariable binary logistic regression was used to find possible predictors of instability, with the raw CCI value as a continuous variable. PASW Statistics 18 (IBM/SPSS) was used for the analysis. The level of significance was set at .05.

Results

Univariable Analysis

Of the 326 patients in the original sample, 38 were missing data on race and 2 were missing CCI data. The total sample was primarily white (74%) and male (59%). The mean age was 58 years, although the variation was large (standard deviation, 20 years). Seven patients (2%) died during their SDU stay.

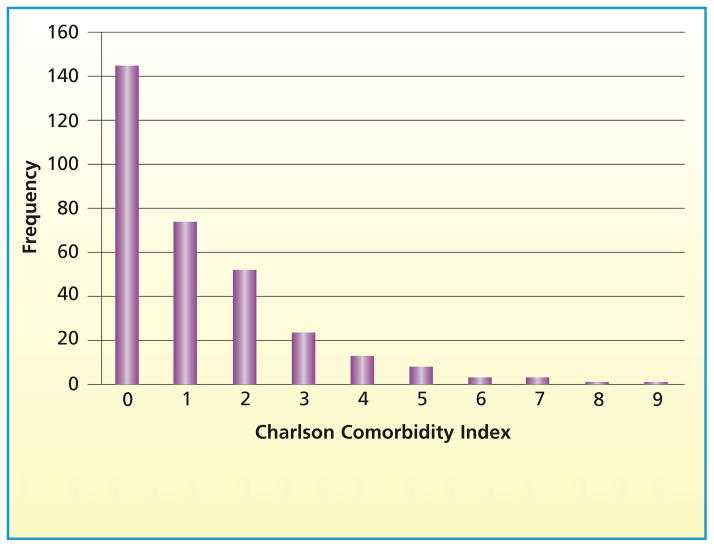

The most prevalent admission diagnosis (according to the admission diagnosis-related group code) was injury (42%). Next were signs and symptoms of poorly defined conditions (15%) and vascular disease (13%). The admitting service was surgery for 64% of the patients and medicine for 36%. Among the patients, 68% were admitted from a SDU or other monitored unit (including primary admission to the study SDU); 23% were admitted from an ICU and 9% from a non-monitored general hospital unit. Of the total sample, 145 patients (45%) had no comorbid conditions and were classified as CCI(0); 179 (55%) had at least 1 comorbid condition and were classified as CCI (≥1). The Figure shows the distribution of all CCI values. The most common preexisting comorbid conditions were diabetes mellitus (n=78; 24%), chronic pulmonary disease (n=64; 20%), congestive heart failure (n = 43; 13%), and myocardial infarction (n = 41; 13%). Overall, 112 patients in the sample (34%) fulfilled the definition of having cardiorespiratory instability at least once during the SDU stay.

Figure .

Distribution of Charlson Comorbidity Index values in the total sample (N = 326).

Age, sex, race, admitting diagnosis, and admission service did not differ significantly between patients who had cardiorespiratory instability during their SDU stay and patients who did not (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparisons between patients in stable and unstable condition (N = 326)

| Characteristica | % of patients

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable condition (n = 214) | Unstable condition (n = 112) | ||

| Sex | .88 | ||

| Male | 59 | 58 | |

| Female | 41 | 42 | |

|

| |||

| Race (n = 288) | .66 | ||

| White | 83 | 85 | |

| Nonwhite | 17 | 15 | |

|

| |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (n = 324), dichotomized | .006 | ||

| 0 | 50 | 34 | |

| ≥1 | 50 | 66 | |

|

| |||

| Admitting diagnosis | .50 | ||

| Heart disease | 5 | 4 | |

| Pulmonary and pulmonary circulation disease | 2 | 4 | |

| Vascular disease | 12 | 15 | |

| Digestive system disorders | 7 | 7 | |

| Symptoms and signs of poorly defined conditions | 15 | 14 | |

| Fractures | 5 | 4 | |

| Injury and contusion | 41 | 45 | |

| Complications of medical and surgical care | 5 | 1 | |

| Others | 8 | 6 | |

|

| |||

| Unit of origin | .06 | ||

| Intensive care units | 21 | 27 | |

| Step-down units and monitored care areas | 72 | 61 | |

| Nonmonitored care areas | 7 | 12 | |

|

| |||

| Admission service | .65 | ||

| Medical | 37 | 35 | |

| Surgical | 63 | 65 | |

Median (range) for age did not differ significantly between the patients in stable condition (59 [78] y) and patients in unstable condition (60 [76] y), according to a Mann-Whitney test (P = .29).

Although the proportion of patients admitted from an ICU was higher for those who experienced cardiorespiratory instability (27%) than for those who did not (21%), the between-group comparison for unit of origin was not significant (P = .06). However, the prevalence of the CCI (≥1) classification was higher among patients who experienced cardiorespiratory instability (66%) than among patients who did not (50%; P < .006).

Multivariable Analysis

The CCI and the unit of origin were entered into the multivariable model. In binary logistic regression analysis (Table 2), only CCI was a significant predictor of cardiorespiratory instability (P = .03). Each 1-unit increase in the CCI increased the odds for cardiorespiratory instability by 1.17. The overall accuracy of the model was 66%; the specificity was high (97%), but sensitivity was low (6%), with a positive predictive value of 54% and a negative predictive value of 67%.

Table 2.

Multivariable binary logistic regression of predictors of instability (n = 324)

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.17 | 1.02 | 1.36 | .03 |

| Intensive care unita | .05 | |||

| Step-down unit and monitored care areas | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1.12 | .12 |

| Nonmonitored care areas | 1.55 | 0.64 | 3.75 | .33 |

Reference group in the “unit of origin” variable.

Discussion

The CCI value at SDU admission was significantly associated with development of cardiorespiratory instability during an SDU stay. We conclude that in a cohort of patients ill enough to warrant SDU admission, having at least 1 comorbid condition is associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing cardiorespiratory instability. Thus, accounting for comorbid conditions may help identify which patients may need closer surveillance.

DePriest11 examined deterioration in hemodynamic status in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding who were admitted to ICUs and concluded that patients without marked comorbid illness with low-risk lesions could be transferred to a general hospital care area. In other studies, patients who had deterioration in hemodynamic status had higher CCI values12 and higher frequency of previous ischemic heart disease and left ventricular dysfunction,13 liver disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and deep-vein thrombosis14 than did patients whose status remained stable. These data collectively suggest that patients with significant comorbid conditions should be closely monitored.

Although our multivariable binary regression model had high specificity (97%), the sensitivity was low (6%). Thus, the model was poor for predicting who would experience cardiorespiratory instability, but good for predicting who would not. This finding is not surprising because the model did not include physiological variables as predictors of cardiorespiratory instability and was limited to demographic and clinical predictors. Physiological variables can be used to define cardiorespiratory instability once the instability is overt but are poor for predicting the onset of instability,15 so our main goal in this study was to determine whether CCI values and other preexisting demographic and clinical variables have predictive value for the occurrence of cardiorespiratory instability in SDUs. Therefore we wished to know if the values could be used clinically to determine which patients should be admitted to an SDU or would need closer surveillance, or even to improve the precision of existing prediction tools. Even though CCI values were only weakly sensitive as a predictor of cardiorespiratory instability, our findings indicate that variables other than vital signs alone can play a role in determining how likely patients are to experience such instability.

Prytherch et al16 developed a new model of an early warning score for predicting adverse clinical outcome by using weighted physiological data alone. Although their tool was superior to the current models, it did not include adjustments for the number of comorbid conditions, adjustments that might improve the performance of the tool. Adding the CCI value to systems for determining early warning scores might improve prediction. In addition, adding CCI values in some fashion to data obtained via dynamic physiological monitoring systems might improve prediction of cardiorespiratory instability; this possibility requires prospective evaluation.

In our study, age, race, and sex did not differ significantly between patients who did and did not experience instability. Although Gallotta et al14 found that patients whose hemodynamic status worsened tended to be slightly older than patients whose status remained stable, in most studies, age12,13 and sex13 were not significantly associated with future instability. However, evidence of a predictive relationship between age and mortality has been reported. Smith et al17 found that mortality in medical assessment units increased as age increased (mean age, 65 years). Goldhill and colleagues18,19 also found that patients who died in the hospital were significantly older than patients who survived and that age was a significant predictor of in-hospital mortality. Although our data were derived from more than 18 000 hours of continuous monitoring, only 7 patients (2%) died during the study, precluding any meaningful analysis of the variables of interest in the development of any models for predicting mortality. However, such analysis might be possible with a larger sample and a longer time of observation. Smith et al,17 who suggested that adding data on age to data on vital signs would improve prediction, used intermittent observations of vital signs by nursing staff. The gaps in assessment that occur during intermittent monitoring can result in lack of detection of important changes in a patient’s clinical status. Whether or not methods of determining early warning scores that use data from continuous monitoring of vital signs coupled with additional demographic and clinical variables will have greater predictive capacity than methods based on data obtained by intermittent monitoring remains to be explored.

Our study has several limitations. We did not gather information about whether and when corrective interventions were applied for supportive care before cardiorespiratory instability occurred. Possibly, trends toward an unstable status were noted by clinicians before instability thresholds were reached, and preemptive interventions were applied, resulting in a underestimation of the true prevalence of instability in the sample. However, evidence in the literature indicates that impending instability and even frank instability most likely are underrecognized,1 so most likely preemptive supportive care was not applied to a degree that would affect our findings. Another limitation is that our sample consisted of trauma and surgical patients, and such patients might be both younger and healthier at their baseline status than are patients in medical SDUs. This possibility may limit the generalizability of our findings. Our sample size was also too small to examine the trend between unit of origin and development of cardiorespiratory instability. Even if such a trend became stronger in a larger sample, establishing the importance of such a relationship would still be difficult. The important factor might not be the unit of origin itself, but rather the degree of stability achieved (or not achieved) before a patient was transferred to the SDU. We did not collect data on the stability of patients’ condition before transfer. Another limitation is that we had a sample size too small to examine relationships with mortality. Nevertheless, these data indicate that preexisting comorbid conditions have some bearing on patients’ likelihood to experience cardiorespiratory instability in the future and implications for the degree of surveillance required. Another limitation is that our sample consisted primarily of a relatively young patients admitted after traumatic injury or surgery. This population of patients most likely had fewer comorbid conditions and lower CCI values than would an older population of patients admitted via a medical service. Thus, the sensitivity of our model for using CCI values to predict cardiorespiratory instability might have been higher if the prevalence of comorbid conditions in our sample had been greater.

Our study has an important strength: the use of data from a continuous monitoring source for heart rate, respirations, and SpO2 to determine cardiorespiratory instability. In all other studies to date, researchers used measurements of vital signs gathered intermittently by various care providers. All of our data were collected by using a continuous monitoring system and are more likely than data colleted via intermittent monitoring to represent the true prevalence of cardiorespiratory instability in SDU patients.

Conclusion

CCI values are associated with the occurrence of cardiorespiratory instability in SDU patients and deserve more study as a predictor of the development of future instability. Although our findings are not entirely novel, they are the first report on the relationship between demographic and clinical characteristics and cardiorespiratory instability detected by using continuous monitoring in an SDU. The findings may suggest the need for increased surveillance by technological means in patients with comorbid conditions, who are more likely than patients without such conditions to experience cardiorespiratory instability. However, the sensitivity of CCI values as a predictor of cardiorespiratory instability is so low that it makes the use of CCI alone for triage questionable. Studies are needed to determine whether using CCI as a criterion for determining the need for increased surveillance would result in better prediction of instability and whether adjusting for comorbid conditions in current severity and early warning scores would result in better prognosticating capabilities for these scores.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This research was supported by grant HL57181 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Khalil Yousef, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Michael R. Pinsky, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Michael A. DeVita, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Susan Sereika, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Marilyn Hravnak, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

References

- 1.Hravnak M, Edwards L, Clontz A, Valenta C, DeVita MA, Pinsky MR. Defining the incidence of cardiorespiratory instability in patients in step-down units using an electronic integrated monitoring system. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(2):1300–1308. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeVita MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, et al. Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2463–2478. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000235743.38172.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL. Medical Emergency Response Improvement Team (MERIT). Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(4):251–254. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324:387–390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinkle RM, Flabouris A. Documenting rapid response system afferent limb failure and associated patient outcomes. Resuscitation. 2011;82(7):810–814. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVita MA, Smith GB, Adam SK, et al. Identifying the hospitalised patient in crisis—a consensus conference on the afferent limb of rapid response systems. Resuscitation. 2010;81:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eshelman LJ, Lee KP, Frassica JJ, Zong W, Nielsen L, Saeed M. Development and evaluation of predictive alerts for hemodynamic instability in ICU patients. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008 Nov 6;:379–383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. Review and performance evaluation of aggregate weighted ‘track and trigger’ systems. Resuscitation. 2008;77:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DePriest J. Low incidence of hemodynamic instability in patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. South Med J. 1996;89:386–390. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagan E, Novack V, Porath A. Adverse outcomes in patients with community acquired pneumonia discharged with clinical instability from internal medicine department. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(10):860–866. doi: 10.1080/00365540600684397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubinger D, Revis N, Pollak A, Luria MH, Sapoznikov D. Predictors of haemodynamic instability and heart rate variability during haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(8):2053–2060. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallotta G, Palmieri V, Piedimonte V, et al. Increased troponin I predicts in-hospital occurrence of hemodynamic instability in patients with sub-massive or non-massive pulmonary embolism independent to clinical, echocardiographic and laboratory information. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124(3):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hravnak M, DeVita MA, Clontz A, Edwards L, Valenta C, Pinsky MR. Cardiorespiratory instability before and after implementing an integrated monitoring system. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:65–72. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fb7b1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prytherch DR, Smith GB, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. ViEWS—towards a national early warning score for detecting adult inpatient deterioration. Resuscitation. 2010;81(8):932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Schmidt PE, et al. Should age be included as a component of track and trigger systems used to identify sick adult patients? Resuscitation. 2008;78(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldhill DR, McNarry AF. Physiological abnormalities in early warning scores are related to mortality in adult inpatients. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:882–884. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Mandersloot G, McGinley A. A physiologically-based early warning score for ward patients: the association between score and outcome. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]