Abstract

An activation mechanism based on encapsulated ultra-small gadolinium oxide nanoparticles (Gd oxide NPs) in bioresponsive polymer capsules capable of triggered release in response to chemical markers of disease (i.e., acidic pH, H2O2) is presented. Inside the hydrophobic polymeric matrices, the Gd oxide NPs are shielded from the aqueous environment, silencing their ability to enhance water proton relaxation. Upon disassembly of the polymeric particles, activation of multiple contrast agents generates a strong positive contrast enhancement of more than one order of magnitude.

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) strategies rely on contrast agents, such as the widely used para-magnetic gadolinium ions (Gd3+ ions), that are “always on”, emitting constant signal regardless of their proximity or interaction with target tissues, cells, or environmental markers of diseases. As a result, the large volume of non-specific signal leads to a poor target-to-background signal ratio, making the tissue or anatomical feature of interest more difficult to distinguish. MRI contrast agents whose relaxivity (r1) may be switched from OFF to ON in response to specific biological stimuli should maximize signal from the target and minimize signal from the background, which, in turn, improves sensitivity and specificity.1

Generally, most designs for activatable MRI contrast agents involve converting biochemical activities (e.g. pH, redox potential, presence of metal ions) to changes in longitudinal r1 of paramagnetic ions via the vacancy number in the inner coordination sphere (hydration number).1b,2 The strength of any MRI activation strategy depends on both effectiveness of quenching the paramagnetic relaxation of surrounding water protons and the degree to which contrast agents’ relaxivity is recovered upon activation. Previous designs for activatable contrast agents present modest changes in r1 upon activation (50% change upon enzymatic activation,3 75% increase upon Ca2+ addition and binding,4 54% increase in presence of NADH,5 18% decrease upon interactions with H2O2,6 and 3-fold enhancement upon a decrease in pH7), as most of them are unable to achieve effective silencing. These designs only prohibit, through synthetic modification of the core chelate, relaxation rate enhancement in the inner sphere (i.e., water directly coordinated to paramagnetic center). This leaves the outer sphere relaxation rate contribution, from hydrogen bonding of water molecules to the chelate and diffusion of the water in its proximity, still active.

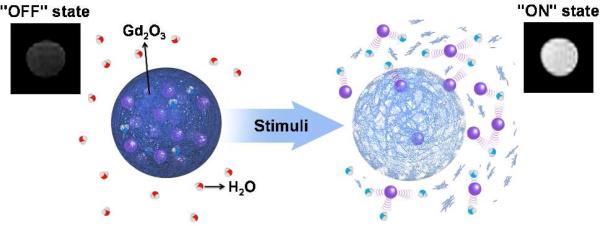

Herein, we report a novel strategy to effectively silence both inner sphere and outer sphere relaxation and activate a collective T1 relaxation from a large number of Gd-based contrast agents in response to specific biological events. The designed MRI agents consist of ultra-small gadolinium oxide nanoparticles (Gd oxide NPs, mean diameter < 5 nm),8 known to have the highest Gd density of all paramagnetic contrast agents, encapsulated in biodegradable polymer capsules capable of triggered release in response to chemical markers of disease (Figure 1).9 When trapped inside hydrophobic polymeric particles, the Gd oxide NPs are shielded from the aqueous environment, resulting in minimal water interaction and quenched T1-weighted signal enhancement (Figure 1, “OFF” state). Upon release of the Gd oxide NPs from the polymeric particles in the aqueous environment, activation of multiple contrast agents generates a strong positive contrast enhancement (Figure 1, “ON” state) and the overall r1 is increased by more than one order of magnitude, which corresponds, to the best of our knowledge, to the largest change in relaxivity yet reported. To demonstrate the wide applicability of this release and report concept, we tested this activatable design with three polymers: the widely used biodegradable polymer poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and two stimuli-responsive polymeric materials capable of rapid and specific triggered degradation upon a decrease in environmental pH or an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) concentration, respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation: The degradable polymer matrix controls the interaction of water with the Gd oxide nanoparticles (purple spheres).

Diethylene glycol (DEG)-coated Gd oxide NPs were prepared by single step polyol synthesis, which consists of direct precipitation of oxides in DEG following alkaline hydrolysis of gadolinium chloride (see Supporting Info (SI)).8b,8c This led to the formation of small nanocrystals with diameters < 5 nm, as seen by transmission electron microscopy (Figure S1). The DEG-coated Gd oxide NPs can be readily functionalized with hydrophilic capping agents such as PEG or coated with a silica protecting layer on the NPs for enhanced biocompatibility and use in an in vitro and/or in vivo setting.8b,10 The proton longitudinal relaxation rates (1/T1) as a function of Gd oxide NP concentration in PBS buffer are shown in Figure S2. The plot of Δ1/T1 vs. Gd concentration shows a linear relationship according to Δ1/T1 = 1/T1,observed - 1/T1,baseline = r1·[Gd], where T1,observed is the relaxation time in the presence of the contrast agent, the baseline T1 time is obtained with the buffer alone, r1 is the longitudinal relaxivity, i.e. the slope of the curve, and [Gd] is the Gd concentration. From the data found in Figure S2, an r1 value of 6.7 s-1.mM-1 was calculated. Nano-sized materials of gadolinium oxide feature high fractions of superficial Gd atoms, which can interact strongly with neighboring water protons and provide high contrast enhancement in MRI. Compared with most gadolinium chelates, Gd oxide NPs induce a higher proton relaxivity (Gd-DTPA, 4.1 s-1.mM-1; Gd-DOTA, 3.6 s-1.mM-1).2b Additionally, since each nanoparticle is made of hundreds of active Gd3+ ions, the resulting relaxivity per unit of contrast agent is hundreds of times larger than that of molecular contrast agents.8c,11

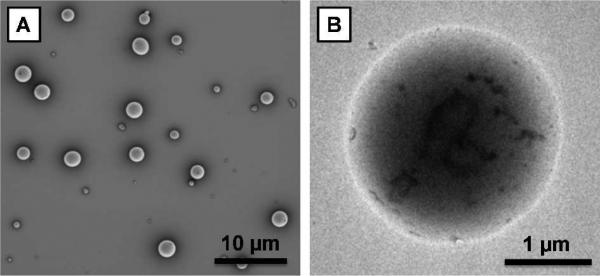

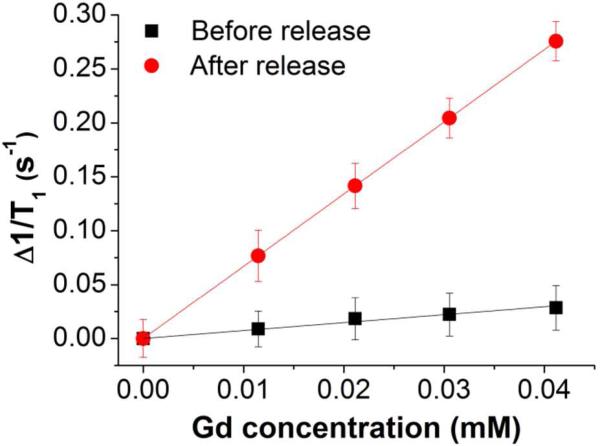

The magnetic relaxation activation concept was first evaluated by encapsulating DEG-coated Gd oxide NPs in commercially available PLGA (MW: 7 - 17 kDa) particles and comparing relaxivity of intact particles to that of degraded particles. Using an electrospray method (see SI for experimental details), which consists briefly of applying high voltage to a polymer solution to produce an aerosol stream of particles,12 we reproducibly incorporated Gd oxide NPs in spherical PLGA polymer capsules with an average diameter of 1.7 ± 0.8 µm (SEM, Figure 2A; size distribution histogram, Figure S3A). Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) of Gd oxide NP-loaded and empty PLGA particles were compared (Figure S4). TEMs of loaded PLGA particles (Figure 2B and Figure S4B) revealed a large amount of encapsulated Gd oxide NPs, appearing as regions of darker contrast, which correspond to a loading of ~1 %w/w or ~100,000 encapsulated Gd oxide NPs per PLGA capsules, as derived by ICP-AES. As predicted, when dispersed in a phosphate buffered saline medium (PBS), the T1 relaxation of the Gd oxide NPs encapsulated in PLGA particles was dramatically quenched and a low r1 value of 0.7 s-1.mM-1 was calculated from the Gd concentration based T1 relaxation rate plot shown in Figure 3 (black squares). Despite their hydrophilic character, the Gd oxide NPs are well retained by the polymer matrix because of their particulate size, a considerable advantage over other small hydrophilic molecular Gd-based contrast agents like Gd-DTPA, which were found to leak rapidly out of polymer particles during the washing steps that followed particle formulation. Since complete hydrolysis of PLGA at pH 7.4 requires 60 to 120 days,13 sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added to raise the pH of the aqueous dispersion to 14 and the mixture was allowed to react 12 hours at 37 °C, completely dissolving the particles. Following dissolution, the pH was brought back to neutral using potassium dihydrogen phosphate and T1 measurements were carried out on these polymer-free suspensions. The longitudinal relaxation time was significantly shortened; the Gd oxide NPs recovered their original r1 value of 6.7 s-1.mM-1, corresponding to 9.6-fold signal activation. A similar increase in r1 (r1,activated/r1,silenced = 9.1) was observed for DEG-coated Gd oxide NPs encapsulated in PLGA particles following a 90 day incubation in PBS at 37 °C (Figure S5), which validates these results. These changes in relaxivity likely result entirely from shielding and de-shielding of Gd oxide NPs, as the diamagnetic contribution of the PLGA matrix to the observed spin-lattice relaxation before and after degradation was insignificant (Table S1). Similar results were also obtained for the stimuli-responsive polymeric matrices used in later experiments (see also Table S1).

Figure 2.

(A) SEM and (B) TEM photographs of Gd oxide NP-loaded PLGA particles.

Figure 3.

Dissolution of PLGA particles enhances relaxivity of encapsulated Gd oxide NPs. Inverse spin-lattice (Δ1/T1) magnetic relaxation measured before (black squares) and after dissolution (red circles). Calculated relaxivities: 0.7 s-1.mM-1 inside PLGA particles; 6.7 s-1.mM-1 outside PLGA particles.

The extracellular matrix of tumor sites and various ischemic tissues are relatively acidic (pH ~ 6.5) due to tumor cells’ high metabolic activity, which limits oxygen availability.14 Several studies have demonstrated that acidic pH serves as a biomarker of tumorigenesis and cancer treatment efficacy.15 Contrast agents activated by low extracellular pH could maximize signal from tumors and minimize background signal, improving sensitivity and specificity of in vivo diagnostics. Towards this goal, we encapsulated Gd oxide contrast agents in a pH-degradable polymeric system, a poly-β-aminoester ketal polymer that utilizes a logic gate pH response mechanism to undergo rapid degradation at acidic pH (Figure S6, structure and degradation steps).16 In the event of a decrease in pH, the polymer backbone undergoes a sharp hydrophobic-hydrophilic switch through the protonation of its tertiary amines, which leads to an increase in uptake of water and hence rapid hydrolysis of the ketal moieties.

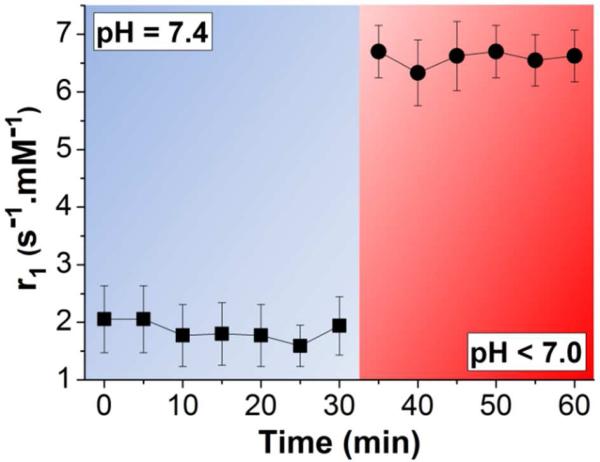

Encapsulation of Gd oxide NPs within pH-responsive polymer particles by electrospray (Dia.: 2.7 ± 0.5 µm, Figure S3B; see SI for particles formulation) resulted in deactivation of their contrast enhancement properties with a mean Gd-based r1 value of 1.6 s-1·mM-1. For the same concentration of Gd oxide NPs, the T1 relaxation appeared less affected by encapsulation in this pH-degradable polymer than in PLGA. We surmise that because the pH-degradable polymer is more hydrophilic than PLGA, these particles are more permeable to water, resulting in more activated contrast. To fully appreciate the effect of the prompt degradation unique to this polymeric system, we monitored T1 relaxation rates before and immediately after lowering the pH to an acidic value (Figure 4). T1 relaxation rates of silenced nanoprobes at pH 7.4 remained stable over 30 min (Figure 4, black squares), while changing the pH to 6.5 (extracellular pH of diseased tissue) caused burst degradation of the particles apparent in solution within one min (Figure S7), reflected by an instantaneous 4.2-fold increase in relaxivity, which remained constant thereafter (Figure 4, black circles). These results confirm rapid pH-dependent triggered release and T1 activation of these probes upon a decrease in pH. A significant advantage of this rapidly degrading system is that it minimizes the effect of diffusion of the contrast agents out of particles on contrast enhancement, as many contrast agents are activated simultaneously in the immediate vicinity of the degraded particle. With slowly degrading polymers like PLGA, contrast agents would have time to become distributed over a larger area, leading to lower signal enhancement. These pH-activatable probes relying on pH-triggered degradation of the polymer matrix could be ideal candidates for in vivo diagnosis of tumors and ischemic diseases.

Figure 4.

Magnetic relaxation of Gd oxide NPs encapsulated in pH-degradable particles increases following a switch from neutral pH to acidic conditions.

This concept of collectively activating many MRI agents simultaneously by encapsulation in on-demand degradable polymers could work with polymers that degrade in response to any biochemical signal (e.g. ions, ROS, glucose). We thus combined our OFF to ON switching process with a H2O2- degradable polymer previously published by our lab,17 creating a H2O2 MRI biosensor. H2O2 is involved in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, such as atherosclerosis, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's disease, and is an important messenger in cellular signal transduction.18 Detection of H2O2 in complex biological environments still presents a substantial challenge.19 Most probes capable of directly detecting H2O2 rely on changes in fluorescence and although they offer high spatial resolution, the lower penetration depths associated with most fluorophores’ excitation/emission wavelengths greatly impede their suitability for whole organ/body imaging. Molecular imaging with this novel concept could offer a powerful approach for studying its accumulation and/or function in living systems with unlimited penetration depth and enhanced spatial integrity due to its activatable nature.

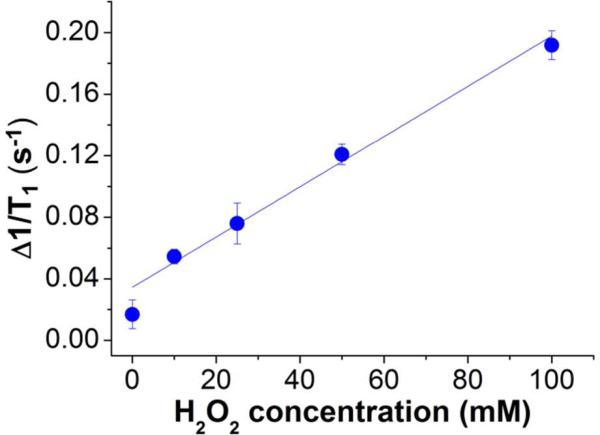

To validate this idea, we encapsulated Gd oxide NPs in a polyester bearing boronic ester triggering groups that degrades by quinone methide rearrangement upon exposure to H2O2 (see Figure S8 for structure and degradation mechanism).17 Particles formulated from this polymer release their contents upon exposure to H2O2; the degree of fragmentation and release is dependent on the number of cleavage events, i.e., H2O2 concentration. As with the two previously studied polymeric matrices, encapsulation of Gd oxide NPs within electrosprayed H2O2-responsive polymer particles (dia.: 0.6 ± 0.3 µm, Figure S3C; see SI for particle formulation) effectively quenched contrast enhancement and low relaxivity, i.e., 0.5 s-1.mM-1. The resulting OFF-state sensors were very stable over time, as magnetic relaxation rates did not change over 5 days at physiological pH (Figure S9), which means that the particles remain intact in the absence of H2O2 activation (also previously observed by de Gracia Lux et al.17). However, increasing amount of H2O2 (0 – 100 mM) triggered an increasing degradation of the polymer, generating a corresponding increase in T1 relaxation rates within 10 min (Figure 5). The maximum increase in r1 was 11-fold, reinforcing the appeal of using responsive polymeric particles encapsulating multiple contrast agents to generate collective signal enhancement upon release. To better understand the nature of the activation, H2O2-degradable polymer particles encapsulating Gd oxide NPs were examined by TEM before (0 hr) and after addition of H2O2 (100 mM) at varying periods of incubation (0.5 - 24 hrs, Figure S10). After 30 min of exposure to H2O2, disruption of the pseudo-spherical morphology of the particles could already be observed, whereas after 24 hrs only irregular masses of aggregated material remained. The presence of increasing numbers of free Gd oxide NPs and empty polymer structures confirmed the gradual release of the Gd oxide payload. Moreover, the number of total polymeric particles on the TEM grids decreased over time, which is consistent with polymer degradation into monomers and observations in solution, as the particle suspension becomes clearer over time. Interestingly, since we monitored a high signal after 10 min incubation, which corresponds to only partial damage of the particles’ integrity, we can assume that the observed reactivation of the Gd contrast agents relies in this case mostly on enhanced water access to Gd oxide NPs within the polymeric vehicles. This is attributed to the nature of the polymer's degradation; few triggering events are needed to render the carriers permeable to water. Used as it is, these activatable imaging agents enabled rapid hydrogen peroxide sensing with a limit of detection of 6 mM. On must note that the responsive polyester polymer used in this study has been shown to degrade in presence of biologically relevant H2O2 concentration (50 – 100 µM). However, considerably slower degradation (~3 days) ensued at these concentrations. Therefore, lower detection limits could be obtained for the same composites, but at the cost of much longer reaction times.

Figure 5.

An increasing concentration of hydrogen peroxide generates a matching increase in T1 relaxation rates of Gd oxide NPs encapsulated in H2O2-responsive polymer.

In summary, a generalizable concept for creating highly efficient activatable MRI contrast agents, adaptable to the detection of multiple chemical species, has been described. The general idea behind this OFF/ON MRI responsive behavior consists of quenching both inner sphere and outer sphere relaxation effects of a large number of Gd-based contrast agents by encapsulating them in hydrophobic polymer particles and limiting water availability. By using responsive polymers sensitive to various biochemical markers (i.e., pH, ROS, enzymes, etc.), a strong MRI contrast enhancement can be activated upon triggered disassembly of the polymeric matrix and release of the previously silenced Gd-based contrast agents into the aqueous environment. We have demonstrated that this concept applies to multiple polymeric materials, showing its broad applicability. The high relaxivity enhancements emphasize the remarkable advantage of using a hydrophobic polymer matrix to encapsulate and silence multiple contrast agents at once over the 1:1 activation strategy involved in most small-molecule-based sensors.2b,19b As they respond with greater changes in relaxivity than those previously reported, surpassing an order of magnitude, these activatable agents have great potential to monitor metabolic reactions and/or detect diseases with better sensitivity and spatial integrity than what has been achieved to date. Diagnostic applications, as well as cellular and in vivo imaging, are currently being explored, as is the expansion of our concepts to other responsive constructs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST-UC San Diego Center of Excellence in Nanomedicine) and the NIH New Innovator Award (1 DP2 OD006499-01) for financial support. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of staff at the Center for Functional MRI in phantom imaging.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental procedure, synthesis of gadolinium oxide nanoparticles, encapsulation of gadolinium oxide nanoparticles in polymeric particles by the electrospray method, measurement of magnetic relaxation, microscopic images, size distributions, polymer structures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.a Kobayashi H, Choyke PL. Accounts Chem Res. 2011;44:83. doi: 10.1021/ar1000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Major JL, Meade TJ. Accounts Chem Res. 2009;42:893. doi: 10.1021/ar800245h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Caravan P. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:512. doi: 10.1039/b510982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tu CQ, Osborne EA, Louie AY. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:1335. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louie AY, Huber MM, Ahrens ET, Rothbacher U, Moats R, Jacobs RE, Fraser SE, Meade TJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:321. doi: 10.1038/73780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li WH, Fraser SE, Meade TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1413. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tu C, Nagao R, Louie AY. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2009;48:6547. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu M, Beyers RJ, Gorden JD, Cross JN, Goldsmith CR. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:9153. doi: 10.1021/ic3012603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gianolio E, Maciocco L, Imperio D, Giovenzana GB, Simonelli F, Abbas K, Bisi G, Aime S. Chem Commun. 2011;47:1539. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03554h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Park JY, Baek MJ, Choi ES, Woo S, Kim JH, Kim TJ, Jung JC, Chae KS, Chang Y, Lee GH. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3663. doi: 10.1021/nn900761s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bridot JL, Faure AC, Laurent S, Riviere C, Billotey C, Hiba B, Janier M, Josserand V, Coll JL, Vander Elst L, Muller R, Roux S, Perriat P, Tillement O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5076. doi: 10.1021/ja068356j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Faucher L, Guay-Begin AA, Lagueux J, Cote MF, Petitclerc E, Fortin MA. Contrast Media Mol I. 2011;6:209. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuart MAC, Huck WTS, Genzer J, Muller M, Ober C, Stamm M, Sukhorukov GB, Szleifer I, Tsukruk VV, Urban M, Winnik F, Zauscher S, Luzinov I, Minko S. Nat Mater. 2010;9:101. doi: 10.1038/nmat2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Faucher L, Tremblay M, Lagueux J, Gossuin Y, Fortin MA. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2012;4:4506. doi: 10.1021/am3006466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Faure AC, Dufort S, Josserand V, Perriat P, Coll JL, Roux S, Tillement O. Small. 2009;5:2565. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu FQ, Joshi HM, Dravid VP, Meade TJ. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1884. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00173b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakraborty S, Liao IC, Adler A, Leong KW. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2009;61:1043. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makadia HK, Siegel SJ. Polymers. 2011;3:1377. doi: 10.3390/polym3031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tannock IF, Rotin D. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Gillies RJ, Raghunand N, Garcia-Martin ML, Gatenby RA. IEEE Eng Med Biol. 2004;23:57. doi: 10.1109/memb.2004.1360409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Perez-Mayoral E, Negri V, Soler-Padros J, Cerdan S, Ballesteros P. Eur J Radiol. 2008;67:453. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sankaranarayanan J, Mahmoud EA, Kim G, Morachis JM, Almutairi A. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5930. doi: 10.1021/nn100968e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Gracia Lux C, Joshi-Barr S, Nguyen T, Mahmoud E, Schopf E, Fomina N, Almutairi A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15758. doi: 10.1021/ja303372u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Droge W. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a Hyodo F, Soule BP, Matsumoto KI, Matusmoto S, Cook JA, Hyodo E, Sowers AL, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:1049. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.8.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lippert AR, De Bittner GCV, Chang CJ. Accounts Chem Res. 2011;44:793. doi: 10.1021/ar200126t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.