Abstract

Learning and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) result from synaptic failure and neuronal loss, the latter caused in part by excitotoxicity and oxidative stress. A therapeutic approach is described, which uses NO-chimeras directed at restoration of both synaptic function and neuroprotection. 4-Methylthiazole (MZ) derivatives were synthesized, based upon a lead neuroprotective pharmacophore acting in part by GABAA receptor potentiation. MZ derivatives were assayed for protection of primary neurons against oxygen-glucose deprivation and excitotoxicity. Selected neuroprotective derivatives were incorporated into NO-chimera prodrugs, coined nomethiazoles. To provide proof of concept for the nomethiazole drug class, selected examples were assayed for: restoration of synaptic function in hippocampal slices from AD-transgenic mice; reversal of cognitive deficits; and, brain bioavailability of the prodrug and its neuroprotective MZ metabolite. Taken together the assay data suggest that these chimeric nomethiazoles may be of use in treatment of multiple components of neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD.

Keywords: Neuroprotection, GABA, Nitric oxide, Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid β, Synaptic plasticity

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disease manifested by progressive memory loss, decline in language skills, and other cognitive impairments. The disorder is reaching epidemic proportions, with a large human, social, and economic burden.1 Currently approved treatments may temporarily reduce the rate of cognitive decline in a limited number of patients, without halting disease progression, however, no treatment is considered disease-modifying.2 Diverse factors play a role in the pathogenesis of AD, notably abnormal aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau protein, glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation.3 Accordingly, a variety of therapeutic strategies modulating the progression or prevention of AD are currently being investigated.4, 5 AD represents a major unmet medical need.

Excitotoxicity is a mechanism of neuronal dysfunction and cell death characterized by excessive stimulation of glutamate receptors, pathological elevation of intracellular calcium concentration and mitochondrial damage. The methylthiazole (MZ) containing GABA-mimetic agent clomethiazole (CMZ; Scheme 1) potentiates the function of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA in the brain,6–8 attenuating glutamate induced excitotoxicity. CMZ has seen clinical use in a number of indications,9–11 and study of compounds related to CMZ, has shown that anticonvulsant and hypnotic potency could be dissociated and modulated separately.12–17 Under the name Zendra, CMZ was explored in clinical trials including Phase III trials as a neuroprotective drug for use in spinal cord injury and ischemic stroke, 18–25 and CMZ continues to be suggested as a potential component of future combination therapies for neuronal injury.26 CMZ has also been demonstrated to counteract inflammation, lowering levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα,27,28 and to rescue mitochondrial function in brain tissues.29 Recent evidence, from both clinical observations and mouse model studies, supports TNFa as a therapeutic target in AD.30–32 Likewise, restoration of mictochondrial function is seen as a strategy for AD therapy.33, 34 Therefore, MZ derivatives, capable of eliciting neuroprotection and attenuating neuroinflammation, are of potential clinical utility in AD.

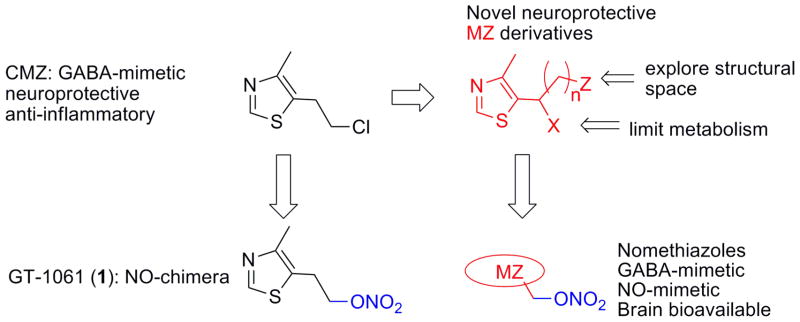

Scheme 1.

Design concept for novel nomethiazole NO-chimeras based upon neuroprotective MZ scaffolds.

An early event in AD is synaptic failure.35 Restoration of synaptic function via activation of cAMP-responsive element binding factor (CREB) is seen as a new target for treatment of AD and other neurological disorders.36–43 Activation of CREB is known to enhance or restore long term potentiation (LTP) and the expression of corresponding gene products to enhance neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis.44–46 Since activation of CREB in the hippocampus is tightly coupled to NO/cGMP signaling,44, 46–49 restoration of normal NO/cGMP signaling in the aging brain is essential to preserve both synaptic and neuronal survival and function. NO-mimetic agents that enhance CREB activity will likely be of benefit in treatment of AD.50

We have previously reported a chimeric molecule with NO and GABA-mimetic attributes, 1 (GT-1061) that contains an MZ pharmacophore (Scheme 1).50 1 significantly improved learning and memory in rats with cognitive deficits in the cholinergic systems of the basal forebrain.37 A key objective of the present study was to determine if 1 is a prototype of an NO-chimera drug class. A positive observation would allow further optimization and refinement of this drug class for AD and other CNS indications. We report herein: 1) the development of a small MZ library; 2) selection of MZ derivatives based upon neuroprotective activity screened in primary neurons; 3) synthesis of novel NO-chimeras, coined nomethiazoles; 4) selection based upon chemical stability; 5) assay for synaptic rescue in brain slices; 6) assay for restoration of learning and memory in vivo; and 7) demonstration of brain bioavailability and measurement of brain/plasma ratios. The drug design approach is depicted in Scheme 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

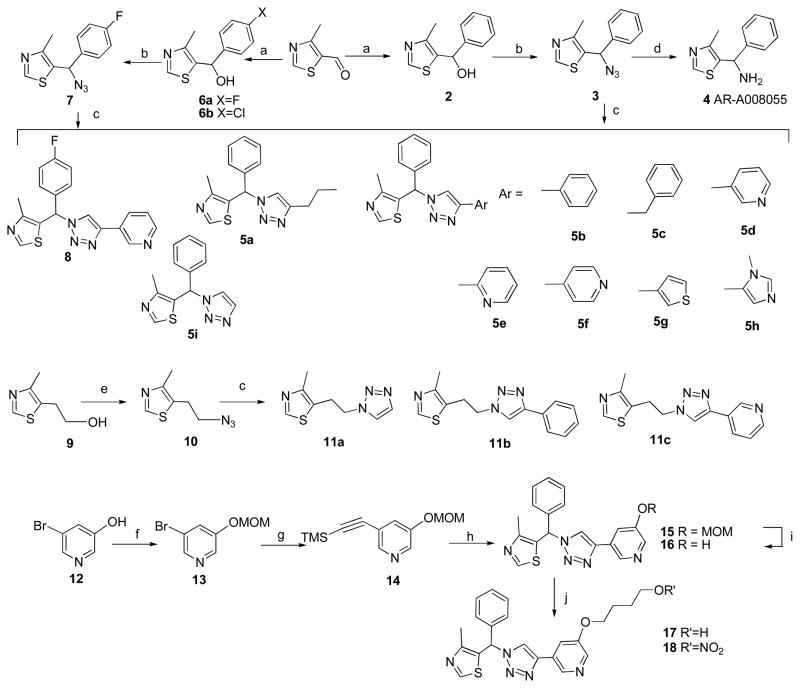

1. Synthesis of MZ derivatives

Copper (I)-catalyzed Huisgen [3 + 2]-cycloaddition between an azide and a terminal alkyne was used to afford regioselectively 1,4-disubstituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles, based upon the mild conditions, reliable high yield, and chemoselectivity of this “click” reaction.51–53 Azide 3 was synthesized in two steps and reacted with commercially available alkynes, including alkyl (e.g. 1-hexyne, ethynyltrimethylsilane, propargylbenzene) and aryl (e.g. ethynylbenzene, regioisomers of ethynylpyridine, 3-ethynyl thiophene and 5-ethynyl-1-methyl-1H-imidazole), to generate a small library of 4-methyl-5-(phenyl(1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)thiazole derivatives (5a-i); and in addition, one fluorinated analogue 8 was also prepared (Scheme 2). The goal was to increase diversity of MZ derivatives and identify novel neuroprotective scaffolds, accordingly 5-(2-(1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-methylthiazole derivatives (11a-c) and two 5-benzyl-4-methylthiazole derivatives were synthesized (6a-b). Of all the click products, compound 5d was identified as an excellent neuroprotectant using in vitro bioassays (discussed below), whereas removal of the 3-pyridyl substitutent (5i), replacement of the pyridine ring with phenyl (5b) or other heterocycles (5g, 5h) and changing the position of the nitrogen (5e, 5f) led to reduced efficacy. A similar structure-activity pattern was observed for 11a-c. Thus the 3-(1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-yl)-pyridine fragment is a potential neuroprotective pharmacophore and was used to develop further MZ derivatives.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: a) Grignard reagent, THF, 0°C to r.t.; b) MsCl, NEt3 then NaN3, CH3CN, r.t.; c) alkyne, CuSO4·5H2O, sodium ascorbate, tBuOH/H2O (1:1, v/v); d) LiAlH4, THF, reflux; e) MsCl, NEt3 then NaN3, CH3CN, reflux; f) MOM-Br, K2CO3, THF; g) ethynyltrimethylsilane, CuI, Pd(Ph3P)2Cl2, NEt3, THF; h) 3, CuSO4·5H2O, sodium ascorbate, K2CO3, MeOH-H2O (2:1); i) HCl/i-PrOH (1.5 M), 70°C; j) 4-nitrooxy-butan-1-ol (for 18) or 1-acetoxy-4-hydroxybutane (for 17), Ph3P, DIAD, 0°C to r.t ; then K2CO3, MeOH (for 17).

Synthesis of MZ analogues, retaining the 5-ethyl-4-methylthiazole motif of both CMZ and 1, proceeded from 4-methyl-5-vinylthiazole (19) to yield the alcohols 22, 23 (Scheme 3). Epoxide intermediate 21 was added dropwise to Grignard reagents to give 22a-c as major products. Although the ultimate objective was to modify MZ derivatives as NO-chimeras, compounds such as the indole derivative, 24, served to extend and explore the MZ structural space. Compound 24 also represents an analogue of latrepirdine, a once-promising new AD drug.54 Tetrahydrocarboline, the starting material for 24, was made according to a published procedures.55 To incorporate the newly discovered 3-(1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-yl)-pyridine pharmacophore into NO-chimera scaffolds, azidoalcohol 25 was obtained by treating epoxide 21 with sodium azide and reacting with 3-ethylnylpyridine under standard click chemistry conditions to give cycloaddition product 26. Compound 31, a close structural analogue of 26, was synthesized from 22c using Suzuki coupling to investigate the tolerance of neuroprotection to triazole ring replacement in the novel pharmacophore.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NBS, CH3CO2H, dioxane-H2O; (b) K2CO3, MeOH; (c) Grignard reagent, THF, 0°C to r.t.; (d) NaN3, CH3CN/H2O (1:1, v/v), reflux; (e) NaH, DMSO, 90°C, 5h; (f) 3-ethynyl pyridine, CuSO4·5H2O, sodium ascorbate, tBuOH/H2O (1:1, v/v); (g) fuming HNO3, Ac2O, CH2Cl2, 0°C; (h) 3-ethynyl pyridine, toluene, reflux, 48h; (i) 2-mercaptoethanol, Na2CO3, CH3CN/H2O (2:1); (j) 3-pyridineboronic acid, (2-biphenyl)di-tert-butylphosphine, Pd(OAc)2, KF, DMF, 120°C.

2. CMZ pharmacology underlying the design and biossay of MZ derivatives

Many papers have discussed the biological activity of CMZ in clinical settings and in animal models. Thiazole derivatives have long been known to manifest sedative/hypnotic and anticonvulsant effects that are indicative of GABA-mimetic activity. 15, 16 The prototype NO-chimera, 1, releases 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole (HMZ) as primary metabolite, which was first reported in 1956 to be an anticonvulsant agent in rabbits.56 CMZ has been shown extensively to be neuroprotective in animal models of transient and global ischemia. CMZ potentiates GABA and muscimol agonism at the GABAA receptor without evidence for modulation of levels of GABA itself; opens neuronal Ca-dependent chloride channels enhancing inhibitory neurotransmission; and, at concentrations 100 fold those required to potentiate GABA function (30 μM), CMZ is a direct GABAA receptor agonist.57–59 CMZ is not a ligand for the GABAB, nor benzodiazepine receptors and potentiates the actions of glycine on inhibitory neurotransmission.6–8

The mechanism of action of CMZ appears not to be limited to GABAA potentiation,60, 61 since CMZ has been claimed to be a p38-MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) pathway inhibitor, although the exact protein target was not defined.68, 69 In Alzheimer’s therapy, inhibition of p38-MAPK is seen as a target, since for example, Aβ-mediated inhibition of LTP involves stimulation of the p38 MAPK cascade.62, 63 Compound 4 (Scheme 2) is the lone analogue of CMZ for which mechanistic data has been reported. In the gerbil model of global ischemia, protection by R-4 and S-4 was equivalent to CMZ, 6 however, R-4 was reported to be devoid of anticonvulsant activity, suggested to be compatible with a mechanism involving GABA re-uptake inhibition.7

CMZ has a short half life and is extensively metabolized. Oxidative metabolism at carbon α to the thiazole ring leads to α-hydroxylation, and formation of metabolites from further oxidation, including an α-chloro ketone and aldehyde.64, 65 The replacement of the secondary α-carbon by addition of a group X (Scheme 1) was justified to prevent metabolic oxidation to potentially electrophilic metabolites. The primary α-hydroxyl metabolite of CMZ was also shown to have sedative activity, providing further reason to limit metabolism at this position. The rationale for exploration of the structural space represented by Z (Scheme 1) using aromatic and heterocyclic groups was based upon the reported biological data on MZ derivative 4 that clearly shows central biological actions including neuroprotection. In the absence of an identified CMZ binding site associated with a GABAA subunit, iterative extension of the structural space was carried out by varying the structure and isomerism, represented by n, X, and Z in Scheme 1.

The selection of a bioassay for iterative design and synthesis of MZ derivatives was not immediately apparent. Despite the wealth of reports on CMZ activity in vivo, relatively few publications have described in vitro assays that could be adapted for screening of novel MZ analogues and derivatives for use as neuroprotectants. In SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells, CMZ was reported to inhibit the glutamate-induced activation of AP-1 mediated by NMDA receptor activation.66, 67 Immortalized cell cultures (e.g. SK-N-MC and the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell lines) would provide a facile system for cell-based drug screening, however, in SH-SY5Y cell cultures subject to excitotoxic insults including glutamate, NMDA, and oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD), CMZ did not produce robust and reproducible neuroprotection (data not shown). Therefore, rat primary cortical neurons were studied as a more complete neuronal model. Excitotoxic cell death from treatment with NMDA (100 μM) was inhibited reproducibly by CMZ treatment and by a number of MZ derivatives and analogues (Supporting Information, Table S1).

NMDA excitotoxicity represents only one aspect of neurotoxicity, whereas OGD provides a much more complete model simulating ischemia followed by reperfusion inducing ATP depletion, glutamate release, NMDA receptor overstimulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS generation, apoptosis, and pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Given the evidence that multiple pathways underlie the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activity of CMZ, OGD in primary neurons was seen as the preferred model to screen and to correlate structure of MZ analogues with activity.

The simple 5-ethyl-4-methylthiazole derivatives (22–23) studied in primary neuron OGD retained comparable neuroprotective efficacy to CMZ (Table 1). In contrast, substitution of the phenyl ring in (4-methylthiazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methanol derivatives (2 versus 6a and 6b in Table 1) significantly reduced efficacy. Further, O-alkylation of 2 led to improved neuroprotection (2 versus 38 and 41 in Scheme 4). Compound 26 (Scheme 3) incorporated a 3-(1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-yl)-pyridine pharmacophore within the MZ scaffold. Both 26 and its regioisomer 30 were protective against OGD, whereas replacement of the triazole substitutent in 26 (26 vs. 31) or substitution of 3-pyridyl in 5d with 2-pyridyl (5e) led to significant loss of efficacy. The results indicate that both triazole and 3-pyridyl moieties are critical structural elements to the neuroprotective 3-(1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-yl)-pyridine fragment.

Table 1.

Relative percentage neuroprotection of primary neuronal cultures in response to OGD after treatment with MZ derivativies.

| % normalized to CMZ after OGDa | % normalized to CMZ after OGDa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-ethyl-4-methylthiazoles | 4-methyl-5-(phenyl(1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)thiazoles | ||

| HMZ | 14.11 ± 8.5 | 5a | 26.8 ± 5.2 |

| CMZ | 100b | 5b | 57.6 ± 6.7 |

| 10 | ns | 5c | 88.3 ± 6.9 |

| 22a | 99.6 ± 1.4 | 5d | 108 ± 3.6 |

| 22b | 98.9 ± 3.0 | 5e | 50.9 ± 6.7 |

| 23a | 102 ± 1.5 | 5f | 90.2 ± 2.2 |

| 23b | 101 ± 3.9 | 5g | 62.0 ± 3.6 |

| 24 | 15.4 ± 5.9 | 5h | 93.9 ± 1.2 |

| 25 | ns | 5i | 58.1 ± 4.2 |

| 31 | 25.0 ± 7.3 | 8 | 87.2 ± 3.5 |

| 16 | 104 ± 1.7 | ||

| (4-methylthiazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methanols | 5-(2-(1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-methylthiazoles | ||

| 2 | 94.0 ± 2.9 | 11a | 51.5 ± 11.8 |

| 6a | 36.8 ± 6.4 | 11b | 53.9 ± 6.8 |

| 6b | 25.0 ± 4.6 | 11c | 99.6 ± 2.5 |

| 38 | 110.2 ± 12.2 | ||

| 41 | 114.1 ± 4.6 | ||

| 2-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethanols | |||

| 26 | 107.3 ± 2.7 | ||

| 30 | 92.9 ± 7.3 | ||

Readings from MTT assay at 24 h normalized to vehicle (0% survival) and CMZ (100% survival).

Comparison, before normalization, with vehicle treated cells demonstrated a mean increase in cell survival of approximately 30% caused by CMZ treatment. % = (Drug-DMSO)/(CMZ-DMSO). Not studied = ns. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n=6).

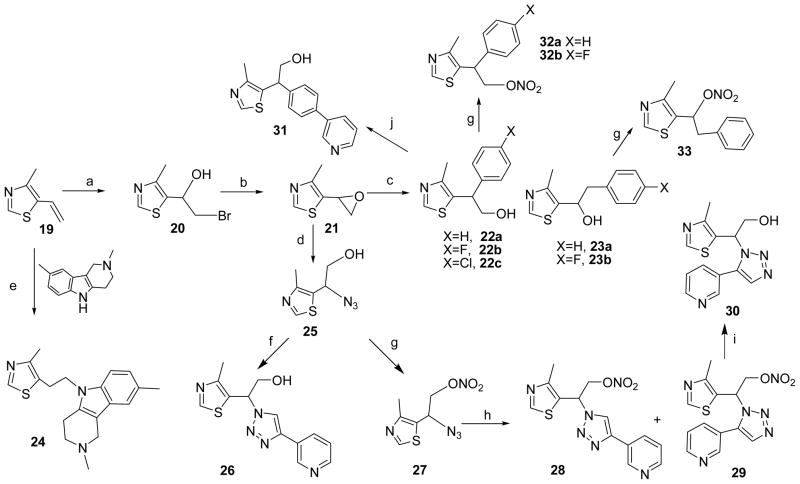

Scheme 4.

Reagents and conditions: (a) fuming HNO3, Ac2O, CH2Cl2, 0°C; (b) TEMPO, PhI(OAc)2, DCM; (c) NaClO2, NaH2PO4, 2-methyl-2-butene, tBuOH; (d) 35 (for 36, 44) or 1-Methylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (for 37), EDCI, DIPEA, HOBT, DCM; (e) NaH, CH3I, DMF; (f) bis(2-bromomethyl)ether, NaH, DMF; (g) AgNO3, CH3CN, reflux; (h) LiAlH4, THF, reflux; (i) triphosgene, AcOEt, reflux; (j) 34 (for 42) or 4-nitrooxy-butan-1-ol (for 43), NEt3, THF.

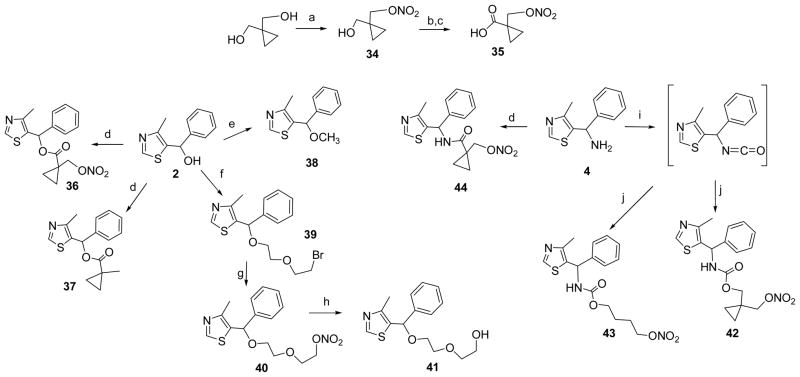

Mindful of the reports of GABAergic and GABA-independent mechanisms of action for CMZ, the mechanism of neuroprotection of four MZ derivatives was probed using the GABAA receptor channel blocker picrotoxin (100 μM) that has been used extensively for selective antagonism of GABAA mediated signaling.68–71 Lower concentrations of picrotoxin deliver only partial blockade,72, 73 and some studies employ higher concentrations.74, 75 Muscimol, a potent, selective GABAA receptor agonist was studied for comparison. Instead of OGD, the simpler excitotoxic insult delivered by glutamate (100 QM) was used to induce neuronal loss, measured at 24 h (Figure 1). As anticipated, muscimol produced effective neuroprotection against glutamate toxicity, which was lost and reversed on blockade of the GABAA chloride channel. Neuroprotection produced by 22a mirrored that by muscimol, indicating a GABAergic neuroprotective mechanism. In contrast, neuroprotection by 11c was significantly attenuated by GABAA receptor blockade, but was not ablated, nor reversed, indicating a neuroprotective mechanism only partially dependent on the GABAA receptor. MZ derivatives, 26 and 41, demonstrated intermediate neuroprotective mechanisms. On the basis of these collected data, a neuroprotective pharmacophore was speculated (Figure 1). Full elucidation of the individual GABA-dependent and GABA-independent pharmacophores requires extended structure activity studies, however, the objective was achieved: to develop novel MZ derivatives to be functionalized as NO-chimeras.

Figure 1.

Inhibition by picrotoxin of neuroprotection elicited by MZ derivatives in primary neuronal cultures subject to excitotoxic insult. Primary cortical cultures (10–11 DIV) were subjected to 24 h of glutamate (Glut; 100 μM) toxicity with co-treatment of muscimol (Musc) or MZ derivatives (50 μM). Picrotoxin (Picro; 100 μM) was added, where indicated, 1 h before glutamate treatment to provide blockade of GABAA signaling. Survival was measured with the MTT assay and normalized to vehicle treated controls. Data shows mean and SEM from at least six individual experiments analyzed by ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s MCT comparing to non-glutamate treated vehicle control, or comparing the efficacy of picrotoxin in blocking each drug treatment effect with a two-tailed t-test: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns: not significant.

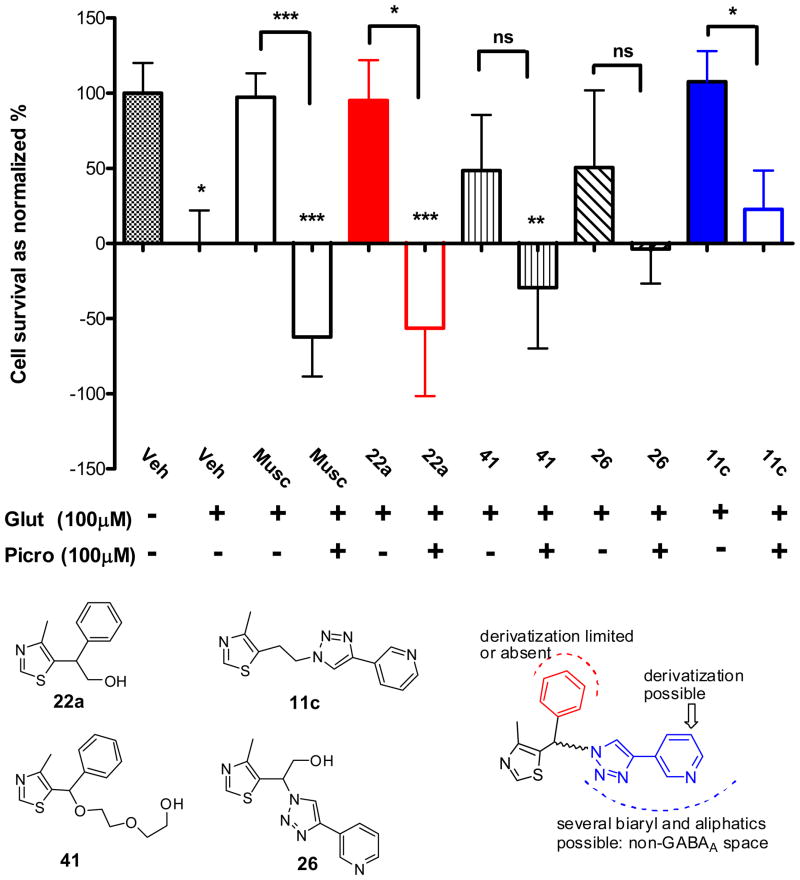

3. Synthesis of NO-chimeras

MZ derivatives (e.g. compounds 5d, 22, 23 and 26, Table 1) were selected for further study based upon efficacy for neuroprotection against OGD-induced cell death and the feasibility of structural modification to give nitrate NO-chimeras. Compound 5d is as an excellent neuroprotectant against OGD and NMDA induced cytotoxicity. Compound 16 (Scheme 2) is an analogue of 5d providing an hydroxyl group on the pyridine ring allowing modification as an NO-chimera. A TMS protected alkyne was introduced into the pyridine derivative 13 via a Sonogoshira reaction, yielding 14, which underwent direct reaction with azide 3 in a basic methanolic solution, as adapted from the literature.76 The MOM protecting group of 15 was removed and NO-chimera 18 was prepared by coupling of 16 with 4-nitrooxy-butan-1-ol under Mitsunobu conditions. Similarly, 17, the de-nitration product of 18 was made by using 4-acetyloxy-butan-1-ol as reactant followed by deacetylation. Both 16 and 17 are potential metabolites of the NO-chimera 18; notably 16 retained neuroprotective efficacy comparable to CMZ (Table 1).

Two general strategies were used for synthesis of nitrate NO-chimeras. The first used simple electrophilic or nucleophilic nitration procedures to generate nitrate esters from alcohol or halide intermediates, respectively. For instance, NO-chimeras 32a-b and 33 were prepared from hydroxyl MZ precursors 22a-b and 23a by the treatment of a mixture of acetic anhydride and fuming nitric acid (Scheme 3). However, this method failed to directly convert 26 to NO-chimera 28, therefore nitrate 27 was prepared from intermediate 25 and then reacted with 3-ethynyl pyridine in the presence of ascorbate and CuSO4. The expected instability of the nitrate moiety under these reductive conditions led to a low yield of 26 as major and 28 as minor product. However, a mixture of 25 and alkyne refluxed in toluene successfully gave both regioisomers 28 and 29 by thermal cycloaddition. The nitrate group of 29 was removed using thiol under basic condition to yield MZ derivative 30 (Scheme 3).

The second strategy of synthesizing NO-chimeras was to incorporate a labile linker group that would distance the nitrate from the MZ core in an approach more akin to that used in hybrid nitrates such as NO-NSAIDs. Esters of cyclopropane carboxylic acid have been reported to possess substantially increased stability towards both acid- and base-catalyzed hydrolysis.77 Inspired by this observation, 1-nitrooxymethylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid (35, Scheme 4) was prepared by mono-nitration and sequential oxidation. Acid 35 was coupled with 2 to yield NO-chimera 36 which was expected to have enhanced stability to esterase hydrolysis and therefore theoretically predicted to have enhanced brain bioavailability. An alternative use of this strategy led to design and synthesis of the carbamate prodrug 42, using the isocyanate precursor obtained from 4 reacting with mono-nitrate 34, again predicted to have further enhanced stability. A similar procedure was used for coupling of 4-nitrooxy-butan-1-ol to yield the carbamate 43. Preparation of the amide-linked prodrug 44 and compound 37 allowed comparison with the ester-linked prodrug 36. Aliphatic nitrate 40 was synthesized from 2 by O-alkylation with dibromide and subsequent nucleophilic substitution using AgNO3. The ethylene glycol linker was incorporated to increase aqueous solubility.

4. Stability of NO-chimeras

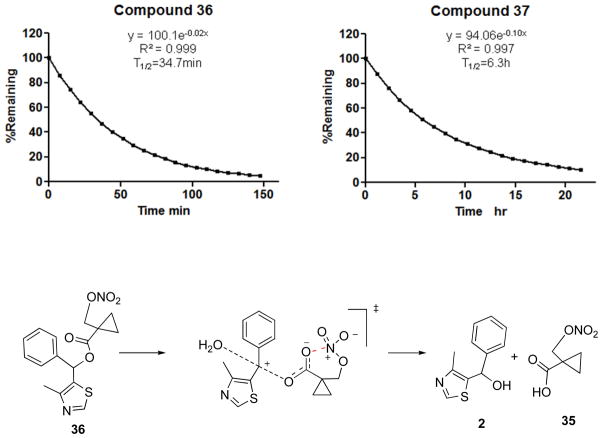

It was anticipated that future animal studies would require simulation of an extended release formulation, potentially by use of drug in buffered drinking water, therefore the stability of nitrates was tested in phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) using HPLC-UV or LC-MS monitoring. Since the nitrate group itself is stable in acid and mild alkaline solution, the observed stability over 5 days at room temperature of 28, 29, 32a-b, 33, 40 was expected; the carbamate 43 and amide 44 were also stable. However, to our surprise, hydrolysis of 36 was rapid, rather than being retarded by the hindered a-cyclopropane group, with a half life of only about 30 min (Figure 2). The lability of the nitrooxymethylcyclopropanecarboxylate was unexpected and therefore comparison was made with the stability of 37 as an analogue lacking only the nitrate group. The observed half life of about 380 min for ester hydrolysis confirms that the nitrate group contributes to the instability of 36. We have previously reported the phenomenon of accelerated hydrolysis caused by an adjacent nitrate group ascribed to intramolecular Lewis acid catalysis78 and propose a similar mechanism for 36 enhanced by a Thorpe-Ingold effect in which the developing negative charge is stabilized by the nitrate moiety through a cyclic transition state (Figure 2). Although more stable than 36, carbamate 42 also decomposed in phosphate buffer with a half-life of approximately 3,000 min to yield at least four UV-detectable products that from LC-MS analysis included two denitrated products (m/z = 333) (Supporting Information, Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Representative kinetic traces for hydrolysis of 36 and 37 (10 μM) in phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4). Incubations were conducted at room temperature and monitored by HPLC with UV detection at 254nm and fit to a pseudo-first order rate equation. A putative mechanism is shown for rate acceleration by anchimeric stabilization of the anionic transition state by the nitrate group acting as intramolecular Lewis acid.

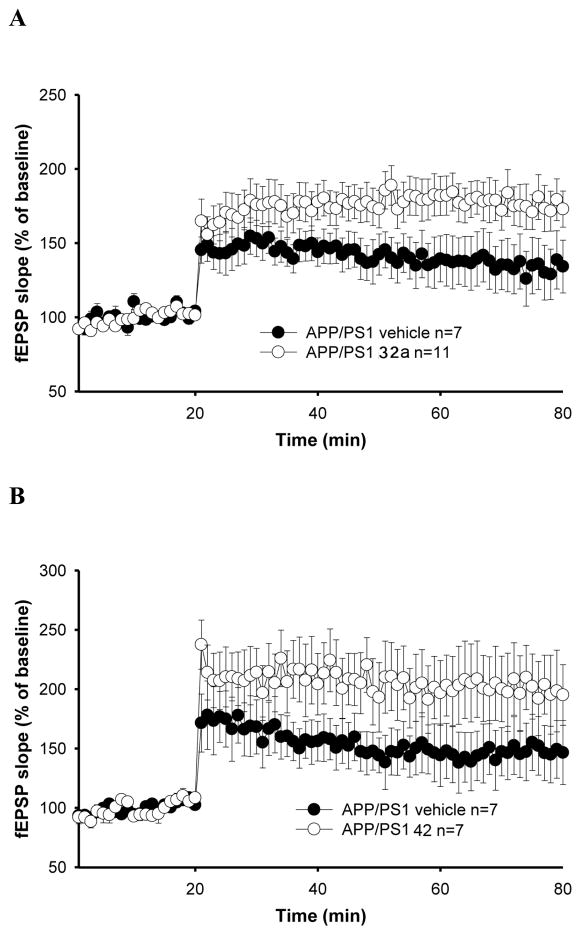

5. Restoration of synaptic function by NO-chimeras

An early event in AD is synaptic failure leading to deficits in learning and memory.35 The importance of synaptic alterations in AD has also been confirmed by studies in transgenic mouse models of AD79 as well as on LTP, a widely studied cellular model of learning and memory. 80 Previous work has reported that synaptic transmission and cognition are altered in double transgenic, APP/PS1 mice expressing both the human APP mutation (K670M:N671L) and the human PS1 mutation (M146L).81, 82 In hippocampal slices obtained from APP/PS1 and WT littermates between 4–5 months of age, reproducible LTP responses in the CA1 are observed, with a reduction of LTP in APP/PS1 hippocampal slices, as measured by field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP). Aβ-induced inhibition of LTP has been observed to be reversed by NO-donors via a mechanism shown to be mediated by the NO/cGMP signaling pathway.47 Basal synaptic transmission was determined by measuring the slope of fEPSP at increasing stimulus intensities in slices from 4–5 month old APP/PS1 mice for NO-chimeras 32a and 42 (100 QM) perfused for 5 min before inducing LTP through a -burst tetanic stimulation of the Schaeffer collateral pathway (Figure 3). 81 Potentiation was observed for 32a, although data for 42 did not reach significance (P<0.1). The requirement for reductive bioactivation of nitrates to NO and the instability of 42 discussed above are likely causes of the observed differences. The potentiation of the actions of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA are not expected to enhance LTP, and accordingly, CMZ did not restore LTP (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Restoration of CA1-LTP impairment in 3-month-old APP/PS1 mouse hippocampal slices. (A) NO-chimera 32a rescued the LTP impairment in APP/PS1 mice (F(1,16) = 4.129, p = 0.05, compared with vehicle; 50–80 min analysis); (B) NO-chimera 42 showed a tendency towards reversal of LTP impairment without reaching significance (F(1,12) = 2.537, p = 0.13, compared with vehicle).

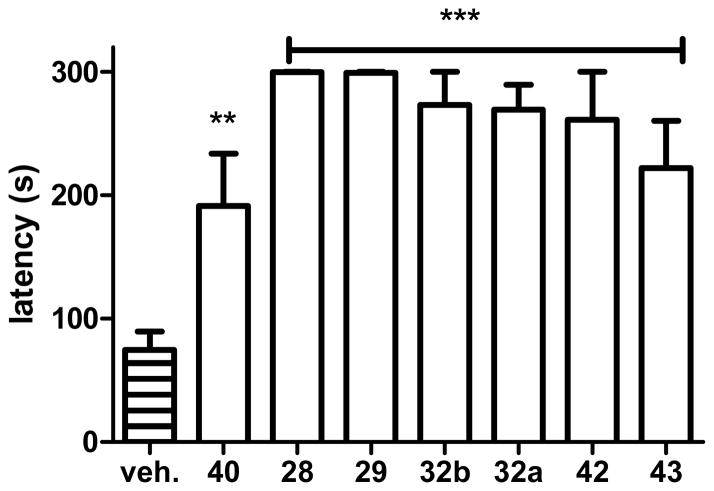

6. Restoration of cognition by NO-chimeras

The step-through passive avoidance (STPA) task was used to measure the reversal of a stimulus-response memory deficit induced by the amnesic agent scopolamine that blocks muscarinic acetylcholine receptor activation. Since muscarinic acetylcholine receptor dysfunction is relevant to AD, scopolamine-induced amnesia remains a useful model for screening of drugs for procognitive actions.83 The STPA task tests learned aversion memory, since mice have a natural preference for dark areas over brightly lit and open areas. Following a period of habituation, the animal is placed in the light compartment of the apparatus and inevitably crosses to the dark compartment of the apparatus at which time an electric shock is delivered. The animals rapidly learn to avoid moving into the dark compartment during the training phase, despite the administration of the amnesic agent. Retention of this newly learned behavior can be tested on subsequent days to assess the strength of the aversive memory, by measuring the latency to enter the dark area. In both training and testing phases, the task is halted after 300 sec if the animal does not enter the dark side.

STPA has a significant advantage for drug screening, because the potential locomotor effects of drugs are very unlikely to confound the observations. Firstly, all animals must show a uniform learning response to training regardless of drug treatment, which initially entails movement between the compartments until the task is learned. Secondly, animals are tested 24 and/or 48 hours after a single drug treatment, and since the majority of drugs, including all NO-chimeras that we have studied to date, have cleared the system long before memory is tested, the STPA task is primarily a measure of memory consolidation.

Scopolamine was administered 30 min and drugs 20 min before training (both i.p.). Drugs were administered at concentrations equimolar to 1 (1 mg/kg; i.e. 4.45 μmol/kg) to provide comparison to previous work.84 Administration of scopolamine and vehicle resulted in a latency of less than 100 s for mice to enter the dark side of the apparatus when tested 24h later, demonstrating an inability to consolidate memory. In contrast, treatment with scopolamine and all novel NO-chimeras studied (28, 29, 32a, 32b, 40, 42, 43), significantly restored memory at 24 h (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Procognitive effects of NO-chimeras evaluated in the scopolamine-induced memory deficit model using the STPA task. Scopolamine was administered 30 min and drug was administered 20 min prior to the start of training and memory was tested 24 h after training and drug treatment. NO-chimeras, 28, 29, 32a, 32b, 42 and 43 (***, p<0.01, compared with vehicle), and 40 (**, p<0.05, compared with vehicle) significantly reversed the scopolamine induced memory deficit. Data were obtained from at least 5 mice per group.

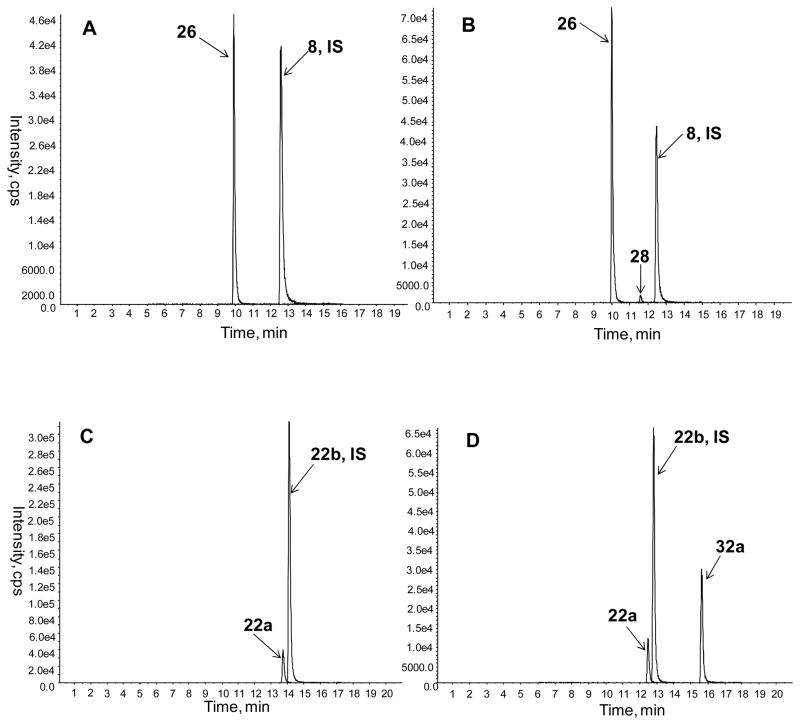

7. Brain bioavailability assessed by LC-MS/MS

Although the procognitive effects of the NO-chimeras are indicative of brain bioavailability, LC-MS/MS measurements were used to confirm blood-brain barrier penetration. Furthermore, a second objective of these assays was to measure the concentrations of MZ metabolites in the brain after NO-chimera delivery, since the neuroprotective properties of the MZ metabolite are an important aspect of the drug design. Figure 5 shows LC-MS/MS chromatograms for multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) after administration of two NO-chimeras and their MZ metabolites, representing two sub-classes of NO-chimera with different physicochemical properties. The NO-chimera 32a showed good brain bioavailability and its 5-ethyl-4-methylthiazole metabolite 22a was also observed in the brain of mice 20 min after administration. In contrast, the bioavailability of NO-chimera 28 was low at this time point, whereas the 2-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethanol metabolite 26 was readily detected. Calculated parameters suggest that 26 (tPSA = 73 Å2; ClogP < 0) should not penetrate the blood-brain barrier, whereas 22a (tPSA = 33 Å2; ClogP = 1.56) has more favorable properties, however, both MZ derivatives were observed in mouse brains after direct i.p. administration or after administration of the NO-chimera prodrug. The preliminary replicate analyses after administration of 26 and 28 suggest that the nitrate chimera prodrug elevates brain levels of 26, relative to direct administration of 26 itself (Table 2). These data, obtained after i.p. administration, are predictive of oral bioavailability, by comparison with data for 1.37

Figure 5.

MRM LC-MS/MS chromatograms of extracted mouse brain samples 20 min after i.p. delivery of each drug at a dosage that was equimolar with 1 (4.5 μmol/kg): A) 26 with 8 used as internal standard; B) 28 with 8 used as internal standard; C) 22a with 22b used as internal standard; D) 32a with 22b used as internal standard.

Table 2.

Analysis of selected MZ derivatives and NO-chimeras in mice brain tissue.

| Injected Drug (i.p.) | Analyte | MRM transition of analytes | Internal Standard and MRM transition | Brain Con. (ng/mL)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 28 | 333→288 |

8 352→147 |

2.1±0.6 |

| 26 | 288→147 | 76.6±10.2 | ||

| 26 | 26 | 56.4±5.5 | ||

| 32a | 32a | 265→220 |

22b 238→207 |

9.5±0.6 |

| 22a | 220→189 | 9.5±1.1 | ||

| 22a | 22a | 32.9±3.7 |

Four mice were used for the injection of each drug. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n=4).

Conclusions

Synaptic failure is an early event in both AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which causes impaired cognition and memory.1 Disease progression involves neurodegeneration of cortical and hippocampal neurons and loss of hippocampal volume. A drug that targets synaptic failure in addition to providing neuroprotection is a rational approach to AD therapy. Abnormally assembled Aβ and tau proteins are associated with both synaptic and neuronal dysfunction and loss.3 Aβ has been shown to downregulate signaling via the NO/cGMP/CREB pathway, therefore enhancement of NO/cGMP signaling and activation of CREB may provide a novel approach for the treatment of AD.39–42, 47, 85 Gene products associated with CREB activation may provide neuroprotection, however, prevention of neuronal loss can also be achieved by selective pharmacological modulation of GABAA receptors, a mechanism that has been shown to provide neuroprotection against Aβ mediated toxicity.86–89

Herein, we have elaborated on the concept of an NO-chimera, incorporating GABA-mimetic and NO-mimetic mechanisms, by developing and derivatizing novel MZ scaffolds. These chimeric agents represent a novel drug class coined nomethiazoles. The milestones for this study were: (1) development of the MZ pharmacophore through synthesis of novel derivatives; (2) assay of neuroprotection in primary neurons; (3) synthesis of nomethiazoles by derivatization of novel, neuroprotective MZ scaffolds, possessing (4) satisfactory stability. Proof-of-concept for nomethiazoles was achieved by demonstration of: (5) synaptic rescue using LTP measurements ex vivo; (6) restoration of learning and memory in vivo; and (7) demonstration of brain bioavailability of both NO-chimeras and their MZ metabolites. It was confirmed that 1 is a prototype of a novel drug class that possesses a combination of GABA-mimetic and NO-mimetic activities, thus providing both neuroprotection and neurorestoration. Since neurodegenerative diseases such as AD are multifactorial, the development of drugs designed to target more than one mechanism of action is likely to be a promising therapeutic approach.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis

1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained with Bruker Ultrashield 400 MHz or Advance 300 MHz spectrometers. Chemical shifts are reported as δ values in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) for all recorded NMR spectra. All reagents and solvents were obtained commercially from Acros, Aldrich, and Fluka and were used without purification. Low-resolution mass spectra (LRMS) were acquired on an Agilent 6300 Ion-Trap LC/MS. High resolution mass spectral data was collected using a Shimadzu QTOF 6500. All compounds submitted for biological testing were found to be > 95 % pure by analytical HPLC. Purity and/or low resolution mass spectral (ESI or APCI) analysis was measured using an Agilent Zorbax Bonus C18, 3.5 μM; 150 × 3.0 mm column, on either a Shimadzu UFLC or Agilent 1100 Series HPLC in tandem with an Agilent 6310 Ion Trap LC/MS. HPLC Method: 0.1 % FA in 10% CH3OH (Solvent A); 0.1 % FA in CH3CN (Solvent B); flow rate 0.5 mL/min; gradient: t = 0 min, 10 % A; t = 1 min, 10% A; t = 18 min, 80% A; t = 20 min, 80 % A; t = 21 min, 95% A.

1-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)-1-phenyl-methanol (2)

4-Methyl-5-thiazolecarboxaldehyde (1.0 g, 7.8 mmol) was dissolved in THF (40 mL) and cooled in an ice bath, phenyl magnesium bromide (1M in THF, 8.5mL) was added dropwise. Reaction mixture was warmed up to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction was quenched with aqueous NH4Cl and extracted with ethyl acetate (2×100mL). Organic solutions were combined, concentrated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/ethyl acetate 1:1, 1.4g, 87%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.81 (s, 1H), 7.45(d, 2H, J=7.2Hz) 7.24–7.36 (m, 3H), 6.16 (d, 1H, J=3.6Hz), 5.34 (d, 1H, J=3.6Hz), 2.38 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 151.57, 148.90, 145.14, 137.96, 129.09, 128.20, 126.92, 69.66, 15.54.

5-(Azidophenylmethyl)-4-methylthiazole (3)

MsCl (2.9 mL) was added to a solution of 2 (6.2 g) and NEt3 (6.0 mL) in anhydrous acetonitrile (70 mL). Reaction was monitored by TLC until the starting material was consumed. NaN3 (6.1 g) was added and the reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight. Most of the acetonitrile was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was diluted with ethyl acetate and washed with water. Organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate, 2:1, 75%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.87(s, 1H), 7.34–7.47(m, 5H), 6.41(s, 1H), 2.45(s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 152.86, 151.16, 140.13, 131.97, 129.67, 129.24, 127.62, 61.78, 15.55. HRMS calcd for C11H10N4S [M+H]+ 231.0704, found 231.0713.

α-phenyl-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)methanamine (4)

LiAlH4 (130 mg, 3.5 mmol) was added to a solution of 3 (320 mg, 1.39 mmol) in anhydrous THF (10 mL). The reaction was refluxed for 1h and quenched with 0.1 N NaOH. The residue was diluted with water and extracted using ethyl acetate (2×25 mL). Organic solutions were combined, concentrated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 15:1, 230 mg, 82%). 13C-NMR (CD3CN, 100MHz): δ 151.62, 148.35, 145.96, 139.76, 129.52, 128.23, 127.51, 53.69, 15.61. HRMS calcd for C11H12N2S [M+H]+ 205.0799, found 205.0807.

Compound 5

Standard click chemistry pro cedure: Azide (1 equiv.) and alkyne (1 equiv.) were dissolved in t-BuOH and water (1:1), sodium ascorbate (0.2 equiv.) and CuSO4·5H2O (0.1 equiv.) were added, the reaction mixture was stirred overnight and diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with water, organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 20:1; yield 75–90%). For compounds 5i and 11a, solvent was changed to a mixture of MeOH and H2O (2:1, v/v), K2CO3 (1 equiv.) was also added in addition to other reactants.

4-Butyl-1-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5a)

1-Hexyne was reacted with 3 to give 5a. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.92 (s,1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.41(m, 3H), 7.27–7.28 (m, 2H), 2.68 (t, 2H, J=8.0Hz), 2.36 (s, 3H), 1.58–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.29–1.38 (m, 2H), 0.88 (t, 3H, J=7.6Hz); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 153.50, 152.51, 148.66, 140.45, 131.10, 129.67, 129.34, 127.72, 122.08, 61.08, 32.23, 25.86, 22.79, 15.40, 14.02; HRMS calcd for C17H20N4S [M+H]+ 313.1481, found 313.1468.

1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5b)

Ethynylbenzene was to give reacted with 3 to give 5b. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 7.92–7.94 (m, 2H), 7.58 (s, 1H), 7.30–7.45 (m, 8H), 2.41 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6,100MHz): δ147.98, 140.23, 131.82, 129.77, 129.55, 129.48, 128.75, 127.74, 126.29, 121.31, 61.47, 15.47; HRMS calcd for C19H16N4S [M+H]+ 333.1174, found 333.1186.

1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-4-(phenylmethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5c)

Propargyl -benzene was reacted with 3 to give 5c. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.98 (s, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.17–7.41 (m, 10H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 2.31 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 153.82, 150.92, 146.33, 139.46, 139.36, 129.81, 128.99, 128.57, 128.52, 126.81, 126.29, 122.78, 59.37, 31.19, 15.05; HRMS calcd for C20H18N4S [M+H]+ 347.1330, found 347.1344.

3-[1-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]pyridine (5d)

3-Ethynylpyridine was reacted with 3 to give 5d. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400MHz): δ 9.10 (bs, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.83 (s, 1H), 8.54 (bs,1H), 8.25 (d, 1H, J=8.0Hz), 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.29–7.49 (m, 6H), 2.45 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100MHz): δ153.98, 151.42, 149.12, 146.58, 143.77, 139.09, 132.71, 129.48, 129.08, 128.76, 126.87, 126.41, 124.08, 122.18, 59.87, 15.12; HRMS calcd for C18H15N5S [M+H]+ 334.1126, found 334.1118.

2-[1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]pyridine (5e)

2-Ethynyl pyridine was reacted with 3 to give 5e. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.55 (d, 1H, J=4.0Hz), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.15 (d, 1H, J=8.0Hz), 7.85 (triple doublet, 1H, J=8.0Hz, 1.6Hz), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.21–7.45 (m, 6H), 2.43 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 153.73, 152.61, 151.51, 150.42, 148.90, 140.03, 137.59, 130.37, 129.79, 129.51, 127.74, 123.69, 123.32, 120.34, 61.43, 15.43; HRMS calcd for C18H15N5S [M+H]+ 334.1126, found 334.1129.

4-[1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]pyridine (5f)

4-Ethynyl pyridine was reacted with 3 to give 5f. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, 2H, J=4.8Hz), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.71 (d, 2H, J=5.6Hz), 7.34–7.40 (m, 4H), 7.18–7.20 (m, 2H), 2.42 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.49, 151.94, 150.09, 145.12, 137.55, 137.39, 129.02, 128.99, 128.81, 126.46, 120.65, 119.73, 60.96, 15.18; HRMS calcd for C18H15N5S [M+H]+ 334.1126, found 334.1119.

1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-4-(3-thienyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5g)

3-Ethynyl thiophene was reacted with 3 to give 5g. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.74 (s, 1H), 7.69 (d, 1H, J=2.0Hz), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.36–7.44 (m, 5H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 7.15–7.16 (m, 2H), 2.43 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.43, 152.16, 144.17, 138.07, 131.47, 129.34, 129.17, 129.08, 126.70, 126.40, 125.73, 121.42, 118.68, 60.91, 15.42; HRMS calcd for C17H14N4S2 [M+H]+ 339.0738, found 339.0754.

4-(1-Methyl-1H-imidazol-5-yl)-1-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5h)

5-Ethynyl-1-methyl-1H-imidazole was reacted with 3 to give 5h. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.75 (s, 1H), 7.70(s, 1H), 7.50 (bs, 2H), 7.39–7.40 (m, 3H), 7.31(s, 1H), 7.17–7.19 (m, 2H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.50, 151.87, 137.66, 129.04, 128.99, 128.90, 126.52, 120.21, 60.89, 15.22; HRMS calcd for C17H16N6S [M+H]+ 337.1235, found 337.1235.

1-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5i)

Ethynyltrimethylsilane was reacted with 3 in the presence of CuSO4, sodium ascorbate and K2CO3 to give 5i. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.90 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, 1H, J=0.8Hz), 7.75 (s, 1H, J=0.8Hz), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.43 (m, 5H), 2.37 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 153.57, 152.41, 140.39, 134.11, 130.73, 129.73, 129.42, 127.71, 125.00, 61.00, 15.35; HRMS calcd for C13H12N4S [M+H]+ 257.0861, found 257.0873.

1-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-methanol (6a)

4-Fluorophenyl magnesium bromide was reacted with 1 to give 6a according to the method described for compound 2. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.49 (s, 1H), 7.33–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.03 (t, 2H, J=8.4Hz), 6.04 (s, 1H), 2.32 (s, 3H); HRMS calcd for C11H10FNOS [M+H]+ 224.0545, found 224.0544.

1-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-methanol (6b)

4-Chlorophenyl magnesium bromide was reacted with 1 to give 16b according to the method described for compound 2. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.56 (s, 3H), 7.33 (bs, 4H), 6.07 (s, 1H), 2.38 (s, 3H); HRMS calcd for C11H10ClNOS [M+H]+ 240.0250, found 240.0245.

5-[azido(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-4-methylthiazole (7)

6a was used to prepare 7 according to the method described for compound 3. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.69 (s, 1H), 7.27–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.07 (t, 2H, J=8.4Hz), 5.98 (s, 1H), 2.43 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 163.82, 161.35, 151.85, 150.28, 134.43, 134.40, 130.92, 128.60, 128.52, 115.98, 115.77, 60.74, 15.49.

3-[1-[(4-Fluorophenyl)(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)methyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]pyridine (8)

3-ethylnyl pyridine was reacted with 7 to give 8 using a method described for compound 5. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, 1H, J=3.6Hz), 8.18–8.21 (m, 1H), 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.34–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.1–7.20 (m, 2H), 7.06–7.11 (m, 2H), 2.44 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 163.97, 161.49, 152.59, 152.09, 149.33, 146.89, 144.89, 113.71, 113.68, 132.89, 128.79, 128.61, 128.53,126.16, 123.60, 119.27, 116.26, 116.04, 60.42, 15.30. ; HRMSb calcd for C18H14FN5S [M+H]+ 352.1032, found 352.1040.

5-(2-Azidoethyl)-4-methylthiazole (10)

MsCl (2.1 g, 18.1 mmol) was added to a solution of 9 and DIPEA (3.7 mL, 22.3 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (100 mL). Reaction was monitored by TLC until the starting material was consumed. NaN3 (2.7 g, 41.9 mmol) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 3h. Most of the acetonitrile was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was diluted with ethyl acetate and washed with water. Organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography. Product was obtained as a slightly yellow oil. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.74 (s, 1H), 3.59 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 3.09 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 2.38 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 150.75, 128.19, 52.72, 26.54, 14.96.

Compound 11

11a-c were synthesized using the method described for compound 5.

1-[2-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (11a)

Ethynyltrimethylsilane was reacted with 10 in the presence of CuSO4, sodium ascorbate and K2CO3 to give 11a. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.62 (s, 1H), 4.68 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 3.45 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 2.18 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ 151.12, 150.93, 133.81, 127.25, 125.13, 51.14, 27.68, 14.59; HRMS calcd for C8H10N4S [M+H]+ 195.0704, found 195.0711.

1-[2-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethyl]-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole (11b)

Ethynylbenzene was reacted with 10 to give 11b. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.60 (s, 1H), 7.76–7.78 (m, 2H), 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.39–7.43 (m, 2H), 7.31–7.35 (m, 1H), 4.60 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 3.44 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 2.25 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.73, 150.32, 147.78, 130.32, 128.80, 128.20, 125.84, 125.69, 119.94, 51.06, 27.34, 14.58; HRMS calcd for C14H14N4S [M+H]+ 271.1017, found 271.1015.

3-[1-[2-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]pyridine (11c)

3-Ethynylpyridine was reacted with 10 to give 11c. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.61 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, 1H, J= 3.6Hz), 8.13–8.15 (m, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.34–7.37 (m, 1H), 4.64 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 3.47 (t, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 2.26 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.82, 150.40, 149.33, 147.01, 144.73, 132.98, 126.49, 125.66, 123.74, 120.35, 51.23, 27.31, 14.61; HRMS calcd for C13H13N5S [M+H]+ 272.0970, found 272.0965.

3-Bromo-5-(methoxymethoxy)pyridine (13)

3-Bromo-5-hydroxypyridine (1.0 g, 5.7 mmol) and MOM-Br (0.64 mL, 6.9 mmol) were dissolved in THF(10mL), anhydrous K2CO3 (1.5 g, 10.9 mmol) was added, the reaction mixture was stirred overnight. After filtration and concentration, the product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 3:1, 1.1g, 88%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.56 (t, 1H, J=2.4Hz), 5.19 (s, 2H), 3.49 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 153.70, 143.96, 137.81, 125.72, 120.18, 94.66, 56.27.

3-(Methoxymethoxy)-5-[2-(trimethylsilyl)ethynyl]pyridine (14)

Compound 13 (1.0 g, 4.6 mmol), CuI (44mg, 0.23 mmol), Pd(Ph3P)2Cl2 (162 mg, 0.23mmol) were placed in a flask and filled with argon. THF (10mL) was added using a syringe followed by NEt3 (3.0 mL, 21 mmol) and ethynyltrimethylsilane (0.7 mL, 5.1 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at r.t.. Most of the solvent was removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 5:1, 0.85 g, 81%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.32–8.35 (m, 2H), 7.43–7.44 (m, 2H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 3.48 (s, 3H), 0.26 (s, 9H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.65, 145.97, 139.21, 125.18, 120.38, 101.15, 98.03, 94.53, 56.17.

3-(Methoxymethoxy)-5-[1-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]pyridine (15)

Azide 3 (783 mg, 3.4 mmol) and alkyne 14 (0.8 g, 3.4 mmol) were dissolved in a mixture of MeOH and water (2:1, 5 mL), K2CO3 (484 mg, 3.5 mmol), CuSO4·5H2O (170 mg, 0.68 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (272 mg, 0.68 mmol) were added, reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Most of the solvent was removed under reduce pressure, the residue was dissolved in DCM and washed with water, organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 20:1, 1.15 g, 86%) 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.39 (m, 4H), 7.18–7.20 (m, 2H), 5.24 (s, 2H), 3.48 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ153.40, 152.50, 151.92, 144.42, 140.07, 139.05, 137.69, 129.01, 128.96, 128.92, 126.79, 126.51, 119.70, 119.48, 94.31, 60.93, 56.03, 15.20.

5-[1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-3-pyridinol (16)

Click product 15 (230 mg, 0.58 mmol) was dissolved in HCl/i-PrOH solution (1.5M, 5.0 mL) and heated at 70°C for 1h, solvent was removed, the residue was dissolved in AcOEt and washed with aqueous NaHCO3, organic phase was separated and concentrated, and crude product was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 15:1, 170 mg, 83%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 9.11 (bs, 1H), 8.93 (s, 1H), 8.61(s, 1H), 8.59 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, 1H, J=2.8Hz), 7.76 (t, 1H, J=2.4Hz), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.46 (m ,5H), 2.41 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ154.63, 153.77, 152.72, 145.09, 140.14, 139.11, 138.41, 130.41, 129.83, 129.56, 128.41, 127.78, 122.09, 119.22, 61.50, 15.43; HRMS calcd for C18H15N5OS [M+H]+ 350.1076, found 350.1068.

4-[5-[1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-3-pyridinyl]oxy-1-butanol (17)

1-Acetoxy-4-hydroxybutane (150 mg, 1.2 mmol), 16 (200 mg, 0.57 mmol) and PPh3 (227 mg) were dissolved in THF (5 mL) and the flask was filled with Argon. The solution was cooled in an ice bath and DIAD (230 μL, 1.1 mmol) was added using a syringe. The reaction was stirred overnight and quenched water. After workup, the crude product was dissolved in methanol (10 mL) and treated with K2CO3 (140 mg). Solvent was removed, the residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate and washed with water. Crude product was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 15:1, 67mg, 28%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.76 (s,1H), 8.50 (d, 1H, J=0.8Hz), 8.24 (d, 1H, J=2.4Hz), 7.84 (s,1H), 7.77 (t, 1H, J=1.6Hz), 7.39–7.41 (m, 3H), 7.33 (s,1H), 7.17–7.19 (m, 2H), 4.10 (t, 2H, J=6.4Hz), 3.73 (t, 2H, J=6.4Hz), 2.44 (s, 3H), 1.89–1.94 (m, 2H), 1.74–1.79 (m, 2H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 155.30, 152.60, 152.09, 144.66, 138.82, 138.13, 137.74, 129.19, 129.16, 129.06, 126.84, 126.64, 119.58, 117.38, 68.19, 62.01, 61.11, 29.07, 25.55, 15.35; HRMS calcd for C22H23N5O2S [M+H]+ 422.1645, found 422.1657.

4-[[5-[1-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]-3-pyridinyl]oxybutane]-1-nitrate (18)

1-nitrooxy-4-hydroxybutane (25 mg, 0.19 mmol), 16 (25 mg, 0.07 mmol) and PPh3 (37 mg, 0.14 mmol) were dissolved in THF (2 mL) and the flask was filled with Argon. The solution was cooled in an ice bath and DIAD (40 μL) was added using a syringe. The reaction was stirred overnight and quenched water. Solvent was removed and crude product was purified by purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 20:1, 67%), 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.77 (s, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.26 (s, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.80–7.79 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 7.17–7.19 (m, 2H), 4.55 (t, 2H, J=6.0Hz), 4.12 (t, 2H, J=6.0Hz), 2.45 (t, 3H), 1.95–1.97 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ155.14, 152.65, 152.24, 144.67, 139.20, 138.14, 137.81, 129.29, 129.26, 129.09, 126.98, 126.72, 119.54, 117.39, 72.70, 67.47, 61.21, 25.47, 23.71, 15.45; calcd for C22H22N6O4S [M+H]+ 467.1501, found 467.1488.

α-(Bromomethyl)-4-methyl-5-thiazolemethanol (20)

4-Methyl-5-vinylthiazole (900mg, 7.2 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of dioxane (2.5 mL), H2O (5 mL) and acetic acid (430 mg), NBS (1.4 g, 7.9 mmol) was added in 3 portions. The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 hour and then diluted with ethyl acetate (50 mL). Organic phase was separated and concentrated, product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1.5:1, 900mg, 52%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.64 (s, 1H), 5.22 (t, 1H, J=6.8Hz), 3.57 (d, 2H, J=6.8Hz), 2.42 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 151.53, 149.48, 132.10, 67.63, 38.44, 15.39.

4-methyl-5-(2-oxiranyl)thiazole (21)

Bromohydrin 20 (650mg, 2.94 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (10 mL), K2CO3 (1.2 g, 8.8 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 hour. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was diluted with hexane and ethyl acetate (50 mL, 2:1 v/v), after filtration and concentration, the product was obtained with enough purity for the next step reaction. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.63 (s, 1H), 4.10 (t, 1H, J=3.6Hz), 3.22–3.24 (m, 1H), 2.91–2.93 (m, 1H), 2.53 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 151.90, 150.69, 128.97, 51.25, 46.80, 14.95.

β-phenyl-4-methyl-5-thiazoleethanol (22a) and α-(Phenylmethyl)-4-methyl-5-thiazole methanol (23a)

Crude epoxide 21 (1.0g, 7.1 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (10 mL) and added dropwise to a phenyl magnisum bromide solution (1M in THF, 10 mL) at 4°C. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at r.t., quenched with aqueous NH4Cl and extracted with ethyl acetate (2×50 mL). Organic phase was separated and concentrated, 22a and 23a were separated and purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1). 22a (major product, 1.0 g; 65%): 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.43 (s, 1H), 7.25–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.17–7.21 (m, 3H), 4.38 (t, 1H, =6.4Hz), 3.95–4.05 (m, 2H), 3.87 (s, 1H, OH), 2.28 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR J (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.11, 149.87, 140.13, 131.48, 128.92, 127.91, 127.33, 67.13, 46.27, 15.34. HRMS calcd for C12H13NOS [M+H]+ 220.0796, found 220.0795. 23a (minor product, 0.2g, 13%): 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.43 (s, 1H), 7.28–7.33 (m, 5H), 4.83 (t, 1H, J=6.4Hz), 3.29 (s, 1H), 3.10–3.19 (m, 2H), 2.17 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.07, 149.89, 143.23, 128.42, 127.82, 126.95, 125.77, 74.36, 36.08, 14.63; HRMS calcd for C12H13NOS [M+H]+ 220.0796, found 220.0796.

β-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-methyl-5-thiazoleethanol (22b) and α-[(4-Fluorophenyl)methyl]-4-methyl- 5-thiazolemethanol (23b)

22b and 23b were synthesized using the procedure described above for 22a from epoxide 21 and 4-fluorophenyl magnisum bromide. Products were separated and purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1). 22b (major product, 60%): 1 H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.45 (s, 1H), 7.16–7.19 (m, 2H), 6.30–6.97 (m, 2H), 4.37 (t, 1H, J=6.4Hz), 3.94–4.03 (m, 2H), 2.26 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 162.66, 160.22, 150.07, 148.95, 136.24, 136.21, 131.98, 129.26, 129.18, 115.36, 115.14, 66.22, 45.16, 14.82. HRMS calcd for C12H12FNOS [M+H]+ 238.0702, found 238.0699. 23b (minor product, 14%): 1 H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.21-.24 (m, 2H), 6.96–6.99 (m, 2H), 4.81 (t, 1H, J=6.4Hz), 3.04–3.16 (m, 2H), 2.12 (s, 3H); 3C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 163.50, 161.06, 150.25, 149.84, 139.14, 139.11, 127.51, 127.43, 126.89, 115.35, 115.14, 73.62, 36.19, 14.61; HRMS calcd for C12H12FNOS [M+H]+ 238.0702, found 238.0709.

β-(4-Chlorophenyl)-4-methyl-5-thiazoleethanol (22c)

Compound 22c was synthesized using the procedure described above for 22a from epoxide 21 and 4-chlorophenyl magnisum bromide (1M in diethyl ether). Product was separated and purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1, 79%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.61 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, 2H, J=8.4Hz), 7.18 (d, 2H, J=8.4Hz), 4.42 (t, 1H, J=6.4Hz), 4.03–4.07 (m, 2H), 2.35 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.29, 149.95, 138.78, 133.13, 131.02, 129.26, 129.00, 66.86, 45.57, 15.32.

2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2,8-dimethyl-5-[2-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethyl]-1H-Pyrido[4,3-b]indole (24)

Caboline (500mg, 2.5mmol) was dissolved in DMSO (5 mL), NaH (120 mg, 60%, 3 mmol) was added and stirred for 5min. 4-Methyl-5-vinylthiazole (2.86 mL, 25 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was heated at 90°C for 5h. Reaction was quenched with MeOH (0.5 mL) and solvent was evaporated under high vacuum. Residue was dissolved in DCM (20mL) and washed with water, organic phase was separated and concentrated, product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, DCM/MeOH 25:1, 0.1% HOAc, 350mg, yellow solid, 36%), compound 24 was obtained as AcOH salt. 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.18–7.22 (m, 2H), 6.93 (d, 1H,J=8.4Hz), 4.28 (t, 2H, J=6.4Hz), 3.82 (s, 2H), 3.23 (t, 2H, J=6.4Hz), 2.92 (t, 2H, J=6.0Hz), 2.56–2.62 (m, 5H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 1.96 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H) ; 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100MHz): δ172.71, 150.34,150.75, 135.69, 133.51, 128.69, 128.35, 126.83, 123.21, 118.16, 109.16, 106.11, 52.23, 51.42, 44.69, 44.22, 27.10, 21.84, 21.48, 20.89, 14.43; HRMS calcd for C19H23N3S·CH3CO2H [M+H]+ 326.1691, found 326.1687.

β-azido-4-methyl-5-thiazoleethanol (25)

Epoxide 21 (400 mg, 2.8 mmol) was dissolved in acetonitrile and water (1:1, 10 mL), NaN3 (553 mg, 8.4 mmol) was added, the reaction mixture was refluxed for 1h. Most of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the residue was dissolved in DCM (20 mL) and washed with water, organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1, 410 mg, 61%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.71 (s, 1H), 4.98–5.00 (m, 1H), 4.80 (bs, 1H), 3.76–3.87 (m, 2H), 2.49 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.35, 150.67, 126.97, 65.28, 59.85, 15.01; HRMS calcd for C6H8N4OS [M+H]+ 185.0497, found 185.0508.

[1-[β-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethanol]-4-(3-pyridinyl)]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (26)

Compound 26 was prepared according to the standard click chemistry procedure described above from 25 and 3-ethynyl pyridine, crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, DCM/MeOH 20:1, 95%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 9.05 (s, 1H), 9.01 (s, 1H), 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.52 (d, 1H, J=3.6Hz), 8.21 (d, 1H, J=8.0Hz), 7.45 (dd, 1H, J=5.2Hz, 7.6Hz), 6.22–6.25 (m, 1H), 4.15–4.20 (m, 1H), 4.04–4.08 (m, 1H), 2.44 (m, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ153.49, 151.44, 148.90, 146.37, 143.36, 132.42, 126.56, 126.36, 123.96, 121.73, 63.87, 58.99, 15.07; HRMS calcd for C13H13N5OS [M+H]+ 288.0919, found 288.0918.

1-nitrooxy-β-azido-(4-methyl-5-thiazoyl)ethane (27)

25 (400 mg, 2.17 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (10mL) and cooled in an ice bath, fuming nitric acid (130μL) and acetic anhydride (245μL) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0–4°C for 4 hours. After dilution with ethyl acetate (20 mL), reaction mixture was neutralized by saturated aqueous NaHCO3. Organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 2.5:1, 350mg, 71%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.79 (s, 1H), 5.24 (t, 1H, J=2.4Hz), 4.58 (d, 2H, J=6.0Hz), 2.53 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.61, 151.93, 125.14, 73.29, 55.79, 15.33.

β-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)-[4-(3-pyridinyl)-1H-1,2,3-Triazole-1-ethane]-1-nitrate (28) and β-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)-[5-(3-pyridinyl)-1H-1,2,3-Triazole-1-ethane]-1-nitrate (29)

Compound 27 (260 mg, 1.1 mmol) and 3-ethynyl pyridine (234 mg, 2.2 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (5 mL), the reaction mixture was refluxed for 48h. Toluene was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, DCM/MeOH 20:1). 28 (165 mg, 44%), 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.98 (s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.59 (d, 1H, J=3.2Hz), 8.18 (d, 1H, J=8.0Hz), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.37 (dd, 1H, J=4.8Hz, 8.0Hz), 6.35–6.38 (m, 1H), 5.31–5.36 (m, 1H), 5.09–5.13 (m, 1H), 2.56 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): d153.33, 153.10, 149.63, 147.04, 145.27, 133.11, 126.01, 123.77, 123.58, 119.70,72.32,55.41,15.40 HRMS calcd for C13H12N6O3S [M+H]+ 333.0764, found 333.0751. 29 (120 mg, 32%), 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.80 (dd, 1H, J=4.8Hz, 1.6Hz), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.59 (d, 1H, J=1.6Hz), 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.64–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.49–7.52 (m, 1H), 5.97–6.01(m, 1H), 5.44–5.50 (m, 1H), 4.98–5.02 (m, 1H), 2.24 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 153.83, 151.55, 151.34, 149.41, 136.44, 135.22, 133.71, 124.74, 123.80, 122.30, 72.76, 52.95, 14.93; HRMS calcd for C13H12N6O3S [M+H]+ 333.0764, found 333.0776.

β-(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)-5-(3-pyridinyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-1-ethanol (30)

Nitrate 29 (100 mg, 0.3 mmol) was dissolved in CH3CN/H2O (2:1, 5 mL), Na2CO3 (300 mg, 3 mmol) and 2-mercaptoethanol (70 μL, 1 mmol) were added. Reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. until most of the starting material consumed. After dilution with DCM (20 mL), the solution was washed with H2O and concentrated. Crude product purified with column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 20:1, 81%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.73 (d, 1H, J=4.0 Hz), 8.66 (bs, 2H), 7.76–7.77 (m, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.45–7.49 (m, 1H), 5.85–5.88 (m, 1H), 4.65–4.71 (m, 1H), 4.18–4.22 (m, 1H), 2.14 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 152.97, 150.91, 150.65, 149.63, 136.91, 135.65, 133.38, 126.45, 123.79, 122.96, 65.62, 58.02, 14.96; HRMS calcd for C13H13N5OS [M+H]+ 288.0919, found 288.0916.

β-[4-(3-pyridyl)phenyl]-4-methyl-5-thiazoleethanol (31)

22c (350 mg, 1.4 mmol), 3-pyridineboronic acid (270 mg, 2.2 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (15 mg), (2-biphenyl)di-tert-butylphosphine (41 mg) and KF(240 mg, 4.1 mmol) were placed in a flask filled with Argon. DMF (10 mL) was added using a syringe. The reaction was heated at 120°C for 1h. DMF was removed under vacuum and the residue was dilution with DCM (50 mL), washed with water. Crude product purified with column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 20:1, 58%).1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.57–8.60 (m, 2H), 8.47 (d, 1H, J=3.6Hz), 7.80 (d, 1H, J=7.6Hz), 7.47 (d, 2H, J=8.0Hz), 7.31–7.37 (d, 3H), 4.50 (t, 1H, J=6.0Hz), 4.09–4.18 (m, 2H), 2.38 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.18, 149.57, 147.96, 147.61, 140.81, 136.27, 136.03, 134.38, 131.51, 128.74, 127.30, 123.57, 66.62, 45.98, 15.26; HRMS calcd for C17H16N2OS [M+H]+ 297.1062, found 297.1071.

β-phenyl-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethane-1-nitrate (32a)

22a (150 mg, 0.68 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (3 mL) and cooled in an ice bath, fuming nitric acid (120 μL) and acetic anhydride (280 μL) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0–4°C for 4 hours. After dilution with ethyl acetate (20 mL), reaction mixture was neutralized by saturated aqueous NaHCO3. Organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 3:1, 110mg, 61%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.64 (s, 1H), 7.25–7.37 (m, 5H), 4.89–4.94 (m, 1H), 4.80–4.85 (m, 1H), 4.68 (t, 1H, J=7.2Hz), 2.40 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.35, 150.21, 138.33, 130.04, 129.06, 127.86, 127.49, 75.02, 41.34, 15.21; HRMS calcd for C12H12N2O3S [M+H]+ 265.0647, found 265.0657.

β-(4-Fluorophenyl)-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)ethane-1-nitrate (32b)

Compound 32b was prepared from 22b as described for 32a. Product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 3:1, 69%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.68 (s, 1H), 7.21–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.03–7.07 (m, 2H), 4.86–4.91 (m, 1H), 4.79–4.84 (m, 1H), 4.68 (t, 1H, J=7.2Hz), 2.40 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 163.39, 160.93, 150.56, 150.27, 134.18, 134.14, 129.83, 129.25, 129.17, 116.17, 115.95, 74.85, 40.69, 15.22; HRMS calcd for C12H11FN2O3S [M+H]+ 283.0553, found 283.0565.

α-(Phenylmethyl)-(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)methanenitrate (33)

Compound 33 was prepared from 23a as described for 32a (86%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.55 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.34 (m, 3H), 7.26–7.28 (m, 2H), 5.88 (t, 1H, J=7.2Hz); 3.38–3.44 (m, 1H), 3.24–3.29 (m, 1H), 2.22 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 150.90, 150.41, 136.15, 129.12, 128.66, 126.22, 124.04, 84.51, 31.27, 14.51; HRMS calcd for C12H12N2O3S [M+H]+ 265.0647, found 265.0657.

1-[(nitrooxy)methyl]cyclopropanemethanol (34)

1,1-Bis(hydroxymethyl)cyclopropane (5.0 g, 48.9 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (100 mL) and cooled in an ice bath. Fuming nitric acid (2.5 mL) followed by acetic anhydride (5 mL) was added slowly. The reaction was stirred at 4°C for 4h and quenched by aqueous NaHCO3. Organic phase was separated and washed with water. Crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/ethyl acetate 4:1, 1.2g, 17%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz): δ 4.53 (s, 2H), 3.44 (s, 2H), 0.59–0.66 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100 MHz): 78.35, 65.36, 21.35, 8.92.

1-[(nitrooxy)methyl]cyclopropanecarboxylic acid (35)

Compound 34 (1.9 g, 12.9 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (100 mL), TEMPO (0.4 g, 2.6 mmol) and PhI(OAc)2 (4.5 g, 14.2 mmol) were added successively. The reaction mixture was stirred until the alcohol was no longer detectable by TLC. Reaction mixture was washed with aqueous Na2S2O3, NaHCO3 and H2O. Organic phase separated and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/ethyl acetate 2:1). The starting material was oxidized to an aldehyde as white solid (1.3 g, 70%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz): δ 8.84 (s, 1H), 4.78 (s, 2H), 1.36–1.47 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100 MHz): 199.35, 74.15, 30.35, 12.56. The aldehyde (1.1 g, 7.6 mmol) and 2-methyl-2-butene (8.8 mL) were dissolved in t-BuOH (50 mL); NaH2PO4·H2O (10.0g) and NaClO2 (9.0g) were mixed with H2O (25mL) and then added to the t-BuOH solution. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was diluted with ethyl acetate (200 mL) and washed with aqueous Na2S2O3 (25 mL), NaHCO3 (25 mL) and H2O (2×40 mL). Organic phase separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated. Product was obtained as white solid (1.1 g, 90%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz): δ 10.3 (bs, 1H), 4.73 (s, 2H), 1.36–1.40 (m, 2H), 1.16–1.20 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6, 100 MHz): 174.21, 76.96, 21.58, 14.48.

[1-[(nitrooxy)methyl]cyclopropanecarboxyl]-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl] ester (36)

Compounds 2 (236 mg, 1.15 mmol) and 35 (222 mg, 1.38 mmol) were dissolved in a mixture of DCM (5 mL) and DIPEA (570 μL), EDCI (330 mg, 1.7 mmol), HOBt (233 mg, 1.7 mmol) and DMAP (15 mg, 0.13 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight and then diluted with ethyl acetate (50 mL), washed with water. Organic phase was separated and concentrated, crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1, 160mg, 40%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.66 (s, 1H), 7.29–7.39 (m, 5H), 7.15 (s, 1H), 4.62–4.68 (m, 2H), 2.48 (s, 3H), 1.45–1.52 (m, 2H), 1.06–1.10 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 170.67, 151.94, 150.66, 138.77, 130.72, 128.76, 128.50, 126.06, 75.06, 71.18, 21.54, 15.39, 14.85, 14.78; HRMS calcd for C16H16N2O5S [M+H]+ 349.0858, found 349.0854.

[1-methylcyclopropanecarboxyl]-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl] ester (37)

Compound 37 was prepared from 2 and 1-methylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid as described for 36 (85%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.31–7.38 (m, 5H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 3H), 1.28–1.32 (m, 2H), 0.72–0.76 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 174.50, 151.68, 150.40, 139.54, 131.62, 128.70, 128.29, 126.19, 70.16, 19.28, 18.70, 17.03, 17.00, 15.50; HRMS calcd for C16H17NO2S [M+H]+ 288.1058, found 288.1070.

5-(Methoxyphenylmethyl)-4-methylthiazole (38)

To a solution of 2 (200 mg, 0.87 mmol) in DMF (4 mL) was added NaH (52 mg, 60%, 0.87 mmol), the reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 15min. CH3I (65 μL, 1 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for another 3 hours. The reaction was quenched with MeOH (1 mL) and then most of the solvent was removed under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (50 mL) and washed with water, organic phase was separated and concentrated. Crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1, 150mg, 70%). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6, 400MHz): δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 7.42–7.44 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.27–7.31 (m, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H); HRMS calcd for C12H13NOS [M+H]+ 220.0796, found 220.0792.

5-[[2-(2-Bromoethoxy)ethoxy]phenylmethyl]-4-methylthiazole (39)

To a solution of 2 (500 mg, 2.4 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) was added NaH (117 mg, 2.92 mmol), the reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 15min. Bis(2-bromomethyl)ether (2.2 g, 9.6 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for another 3 hours. The reaction was quenched with MeOH (1 mL) and then most of the solvent was removed. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (50 mL) and washed with water, organic phase was separated and concentrated. Crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1, 740mg, 86%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 300MHz): δ 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.39 (m, 5H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 3.81(t, 2H, J=6.1Hz), 3.62–3.73 (m, 4H), 3.46 (t, 2H, J=6.1Hz), 2.45 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 151.50, 149.60, 140.83, 133.74, 128.60, 128.09, 126.58, 77.31, 71.25, 70.65, 68.36, 30.45, 15.57.

1-nitrooxy-2-[2-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethoxy]ethoxy]ethane (40)

Silver nitrate (2.0 g, 11.8 mmol) was added to a solution of 39 (1.1 g, 3.1 mmol) in CH3CN (15 mL), the reaction was refluxed for 2 hours and then diluted with ethyl acetate (50 mL). After filtration and concentration, the crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1.5:1, 720 mg, 69%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.62 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.38 (m, 5H), 4.59 (t, 2H, J=4.4Hz), 3.77 (t, 2H, J=4.4Hz), 3.67–3.69 (m, 2H), 3.62–3.64 (m, 2H), 2.45(s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ151.40, 149.46, 140.63, 133.55, 128.49, 127.99, 126.39, 77.22, 72.03, 70.69, 68.26, 67.15, 15.36. HRMS calcd for C15H18N2O5S [M+H]+ 339.1014, found 339.1014.

[2-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol (41)

To a solution of 40 (70 mg, 0.21 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added LiAlH4 (35 mg, 0.85 mmol), the reaction was refluxed for 1h and then quenched with methanol. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with water. Crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/acetone 2:1, 25mg, 41%) 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.64 (s, 1H), 7.29–7.38 (m, 5H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 3.71–3.74 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.66 (m, 4H), 2.45 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz):151.60, 149.56, 140.71, 133.66, 128.65, 128.16, 126.52, 72.38, 70.37, 68.49, 61.80, 15.52; HRMS calcd for C15H19NO3S [M+H]+ 294.1164, found 294.1169.

N-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-[1-[(nitrooxy)methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl carbamate (42)

Compound 4 (160 mg, 0.78 mmol) and triphosgene (297 mg, 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and refluxed for 2 hours, solvent was removed, the residue was re-dissolved in a mixture of THF (5 mL) and NEt3 (0.25 mL, 1.8 mmol), 34 (147 mg, 1 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 40°C for 1 hour. Solvent was removed and the product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1, 150 mg, 51%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400MHz): δ 8.55(s, 1H), 7.27–7.36(m, 5H), 6.19(s, 1H), 5.98(s, 1H), 4.35(s, 2H), 3.98(s, 2H), 2.39(s, 3H), 0.67–0.71(m, 4H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 155.21, 150.51, 149.68, 140.32, 133.53, 128.69, 127.93, 126.39, 77.06, 68.31, 51.97, 30.68, 18.33, 15.08, 9.41; ; HRMS calcd for C17H19N3O5S [M+H]+ 378.1124, found 378.1114.

N-[(4-Methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-[4-(nitrooxy)butyl] carbamate (43)

Compound 43 was prepared from 4 and 4-nitrooxy-butan-1-ol90 using the same procedure described for 42. Product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1, 65%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 8.60 (s, 1H), 7.27–7.38 (m, 5H), 6.19 (bs, 1H), 5.45 (bs, 1H), 4.45 (bs, 2H), 4.13 (t, 2H, J=5.6Hz), 2.41 (s, 3H), 1.60–1.80 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ155.35, 150.46, 149.51, 140.31, 133.60, 128.60, 127.83, 126.35, 72.40, 64.10, 51.81, 25.01, 23.18, 14.98; HRMS calcd for C16H19N3O5S [M+H]+ 366.1124, found 366.1117.

N-[(4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)phenylmethyl]-1-[(nitrooxy)methyl]cyclopropanecarboxamide (44)

Compound 44 was prepared from 4 and 35 as described for 36. Crude product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1, 49%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 8.59 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.38 (m, 5H), 6.61 (d, 1H, J=7.2Hz), 6.45 (d, 1H, J=7.3Hz), 4.58 (s, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.35–1.39 (m, 2H), 0.94–0.97 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz): δ 169.97, 150.58, 150.04, 139.98, 133.04, 128.97, 128.18, 126.50, 76.03, 50.59, 22.68, 15.26, 13.74, 13.66; HRMS calcd for C16H17N3O4S [M+H]+ 348.1018, found 348.1008.

Stability of NO-chimera in neutral phosphate buffer

Stock solutions of 36, 37 and 42 were made in DMSO. Compound 36 or 37 (10μM) and 5i (internal standard, 10μM) were dissolved in phosphate buffer (100mM, pH 7.4), final concentration of DMSO was 2% (v/v). The solution was kept in the auto sampler of HPLC at room temperature and aliquot (50 μL) was injected into HPLC column. Injection occurred about every 7 min for 36 and 67min for 37 due to different stability of the two compounds. HPLC analysis was performed using Shimadzu UFLC instrument with UV absorbance detection at 254 nm. Separation of parent compound, hydrolysis product (compound 2) and internal standard (IS) was achieved using a Hypersil BDS C18 column (2.1×30mm, 3μm). The composition of HPLC mobile phase was a mixture of water with 10% methanol, 0.1% formic acid (solution A), and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (solution B). The mobile phase was initially composed of solvent A/solvent B (90:10), held for 1 min, and then a linear gradient of solution B from 10 to 95% over next 3 min. The solvent was held at 95% of solution B over 1 min and the column was finally balanced using 10% solvent B for 1.5 min. Flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. Peak area ratio of parent compound vs. internal standard was calculated at each time point and divided by the time zero value to give the percentage of compound remaining.

To detect the decomposition products of 42, the compound (100 μM) was dissolved in phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4), final concentration of DMSO was 2% (v/v). The sample was placed in the dark at room temperature for 48h. Aliquot (10 μL) of the sample was analyzed using an Agilent 6310 ion trap mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with Agilent 1100 HPLC system and electrospray ionization (ESI) source operated in positive mode. HPLC was performed using an Agilent Zorbax Bonus reverse phase C18 column (3.0 mm × 150 mm, 3.5 μm) with UV absorbance detection at 254 nm. The composition of HPLC mobile phase was the mixture of water with 10% methanol, 0.1% formic acid (solution A), and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (solution B). The mobile phase was initially composed of solvent A/solvent B (90:10), held for 1 min, and then a linear gradient of solution B from 10 to 80% over 17 min, 0.5 min gradient of solution B from 80 to 95% and held for 5min. Flow rate was set at 0.5 mL/min.

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice aged 8–10 weeks (20–25 g, Charles River Laboratories, IL) were used for step through passive avoidance (STPA) task and brain bioavailability assay. Sprague Dawley rat (gestational day 17–18, Charles River Laboratories, IL) were used for the primary neuronal cultures. Animals were housed at the BRL (biological resources laboratories) animal facility at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). The animals were kept under standard laboratory conditions with free access to dry food and water, but no nesting materials (Nestlets™) supplied (not enriched environment). Regular light-dark cycle with at least 12 hours of light was maintained throughout the housing in the facility. Animals were acclimated for at least one week in BRL before running any experiment. Also 1–2 h prior to each testing, mice were habituated to the animal study room in the facility. All protocols using live animals were reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UIC (Animal Care Committee). Injection volumes were adjusted based on the animal weight (0.1 ml/25 g mouse).

Double transgenic APP/PS1 mice expressing both the human APP (K670M:N671L) and PS1 (M146L) (line 6.2) mutations were used for LTP study. They were obtained by crossing APP with PS1 animals.38 The animals were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (with light onset at 6:00 A.M.) in temperature and humidity-controlled rooms of the Columbia University Animal Facility. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Primary neuronal cultures

Primary cultures of rat cortical neurons were prepared as described.91 Briefly, brains were removed from embryonic day 17 Sprague Dawley rat embryos, cortices were dissected and meninges were removed. Neurons were mechanically dissociated in Basal Medium Eagle 1X containing glucose (33 mM), glutamine (2 mM), 10% horse serum and 10% FBS, and then plated at 3×105 cells/cm2 in poly-L-lysine-precoated plates. The medium was replaced 24h later with serum-free neurobasal medium (NBM) supplemented with 0.5 mmol/L-glutamine and 2% complete B27 supplement. Four days later, 50% of the medium was replaced with fresh NBM. Neurons were used for OGD or NMDA cytotoxicity experiments after grown for 8–10 d in NBM.

Primary neurons subject to transient OGD followed by reoxygenation

Primary cortical cultured neurons were subjected to a transient OGD as described.92 On day 8–10 of culture, cultured neurons were placed in a humidified 37°C incubator (95% N2, 5% CO2) and the culture medium were replaced with deoxygenated, glucose-free balanced salt solution, pH 7.4, containing the following (in mM): NaCl 116, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.8, KCl 5.4, NaH2PO4 1, NaHCO3 14.7 and HEPES 10. Following 2 hours of OGD incubation, OGD were ended by replacing OGD medium with testing compound conditioned fresh NBM (supplemented with 0.5 mmol/L-glutamine and B27 without antioxidants). Cultures were returned to the normoxic 37°C incubator (5% CO2) for 24 hours prior to evaluation of cell viability and neuronal death by MTT and LDH assay. The test compounds (50 μM) were present during 2-hour OGD and 24-hour reoxygenation.

NMDA and glutamate induced cytotoxicity in primary neurons

Primary cortical cultured neurons were subjected to NMDA induced cytotoxicity as described.93, 94 On day 11 of culture, primary neurons were pre-incubated with testing compounds (50μM) for 30 min in neurobasal culture mudium, and were exposed to NMDA (100μM) in HEPES-buffered salt solution, containing (in mM) NaCl 20, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 0.8, CaCl2 1.8, glucose 15 and HEPES 20 (pH 7.4). Twenty-four hours later, cell viability and neuronal death were evaluated by MTT and LDH assay. The testing compounds (50μM) were presented during the pre-incubation and 24-hour chronic NMDA cytotoxicity. MTT assay for cell viability and LDH assay of cell death were performed as described previously.95

To probe the mechanism of neuroprotection elicited by MZ derivatives, after 10–11 DIV (day in vitro), picrotoxin (100 QM) was added to primary neuronal cultures 1 h before glutamate (100μM) insult. One hour after glutamate addition, MZ derivatives or muscimol were supplied at a final concentration of 50 QM. After incubation for 24 h, final cell survival was assayed using MTT. For comparison, picrotoxin treatment was omitted in another experiment.

LTP measurement