Abstract

A solid-state nanopore can be used to sense DNA (or other macromolecules) by monitoring ion-current changes that result from translocation of the molecule through the pore. When transiting a nanopore, the highly negatively charged DNA interacts with a nanopore both electrically and hydrodynamically, causing a current blockage or a current enhancement at different ion concentrations. This effect was previously characterized using a phenomenological model that can be considered as the limit of the electro-hydrodynamics model presented here. We show theoretically that the effect of surface charge of a nanopore (or electroosmotic effect) can be equivalently treated as modifications of electrophoretic mobilities of ions in the pore, providing an improved physical understanding of the current blockage (or enhancement).

1. Introduction

Nanopores have been demonstrated as ultra-sensitive sensors for many macromolecules, such as DNA [1, 2], poly(ethylene glycol) [3, 4], microRNAs [5, 6], protein [7, 8], and DNA-protein complex [9, 10, 11]. During a typical sensing process, a biasing electric field is applied to drive charged molecules through a nanopore that connects two fluidic chambers. For each translocation event, an ionic current through the nanopore could be temporarily reduced, i.e. current blockage (CB). From current signals, physical features of a transported molecule (such as the size and charge) and dynamic properties (such as mobility and capture-rate) can be inferred [12, 13]. For example, nanopores has been applied to analyze the conformational change (e.g. folding and unfolding) [14, 15, 16] and protonation states [17] of a protein molecule. By functionalizing nanopores with receptors, it is possibe to monitor in real time the binding and unbinding of proteins to receptors from ionic current signals [18].

More importantly, a nanopore could be potentially deployed to sequence DNA, which promises to be a low-cost and high-throughput technology [19]. By monitoring an ionic current, recently developed protein-nanopore techniques allow not only the detection of a DNA molecule [20, 21], but also the sensing of each nucleotide in a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecule [22, 23]. For a synthetic solid-state nanopore, recent theoretical study shows that ionic currents through the pore can be nucleotide-sensitive, provided that the conformation of DNA nucleotides can be controlled during the translocation [24]. Additionally, DNA translocation events through a nanopore are normally recorded by an ionic current [25, 26, 27]. Thus, it is essential to understand signals of an ionic current through a nanopore, with and without DNA translocation.

Besides the CB during DNA translocation, a current enhancement (CE) is also possible in a low-concentration electrolyte [28]. Interestingly, both CE and CB are not always observable in experiment, although subsequent analyses (using the real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method) surprisingly confirm the presence of DNA molecules in the trans. chamber [29].

An earlier and elegant theoretical characterization of the CB and CE was based on a phenomenological model [28] that ignores the electroosmotic effect in a charged pore. However, even for a neutral nanopore, an electroosmotic flow is still present during DNA translocation because of charges on the DNA surface [30]. During the DNA translocation, the flow moves opposite the direction of DNA motion and could exert extra frictional force on DNA, reducing the effective electric driving force on the DNA molecule [30, 31, 32]. The influence of such flow on ionic current signals, with or without DNA translocation through a pore, is still not well understood.

In this article, we apply electro-hydrodynamics equations to derive experimentally measurable signals, such as an open-pore current, CB and CE during DNA translocation as well as non-measurable quantities, such as ion concentrations inside a nanopore (compared to a bulk concentration), and clarify the role of an electroosmotic flow.

2. Methoods

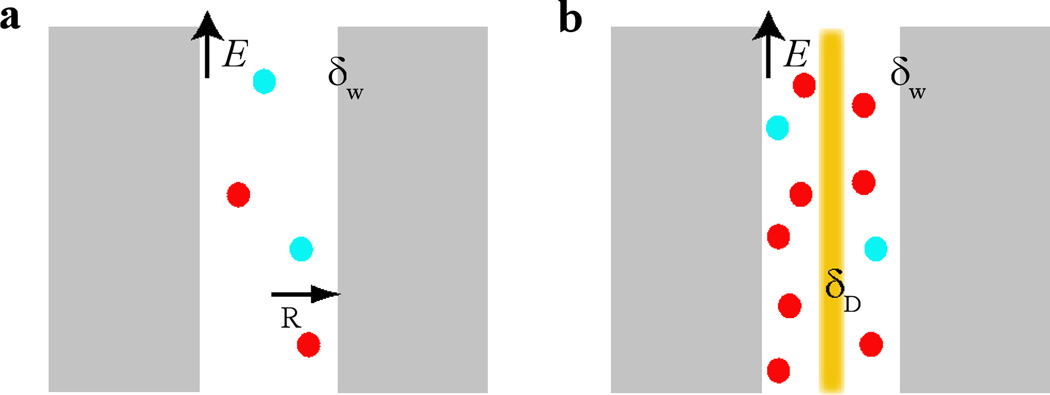

Figure 1 illustrates two modeled systems. The model for computing an open-pore conductivity is shown in Fig. 1a and the model for DNA translocation is shown in Fig. 1b. An electric field E is uniformly applied along the z-axis and electric potentials inside the pore can be written as ψ(r)+Ez. Thus, when ignoring end effects of a pore, ion distributions and the electroosmotic flow are uniform along the z-axis. The electro-hydrodynamics in these models are governed by coupled Poisson and Stokes (assuming a low Reynolds number for an electrolyte in a nanopore) equations,

| (1) |

| (2) |

where ψ(r) and υ(r) are the radius-dependent electric potential and flow velocity, respectively; ρ is the ion concentration; ε and η are the dielectric constant and the viscosity of an electrolyte, respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic views of modeled systems. (a) A cylindrical ion-channel with the radius R. (b) A cylindrical ion-channel with a dsDNA molecule (orange) at the center. The surface charge density of dsDNA is δD and the surface charge density of the channel surface is δw. An electric field E is applied along the channel. Potassium and Chloride ions are illustrated as red and cyan spheres, respectively.

According to the double layer theory, the slipping plane in the diffuse layer separates the mobile fluid from the immobile one. Therefore, the velocity of a flow at the slipping plane is zero, i.e., υ(R)=0; the velocity of the flow at the pore center satisfies that υ’(0)=0 (υ’ is the radial derivative). Here the radius R of a pore is defined as the distance from the pore center to the slipping plane. Between the slipping plane and the solid surface of a pore, there are the Stern layer (a layer of ions absorbed at the surface) and a layer of immobile water; the entire thickness of these two layers is only about a few angstroms. The electric potential at the slipping plane is defined as the electrokinetic potential or ζ-potential, i.e., ψ(R)=ζ. At the pore center, ψ’(0) = 0. After applying these boundary conditions, the coupled Eqs. (1) and (2) yield,

| (3) |

With DNA translocation, the boundary conditions on the DNA surface (r = RD) are υ(RD)=υD and ψ(R)=ζD. Here, ζD is the ζ-potential of the DNA surface. The flow profile is also described by Eq. 3 and the DNA velocity υD =εE(ζD-ζ)/η [33]. Similarly, on a flat and charged surface, the velocity of an electroosmotic flow υ = εΔψE/η, where Δψ is the potential difference across the diffuse layer whose thickness is characterized by the Debye length λ. However, besides the Debye length, the radius of a cylindrical pore imposes an additional limit to the counterion distribution or to the conductivity of a nanopore.

The ionic conductivity σ of a nanopore at a steady state can be calculated from the Nerst-Planck equation. The total ionic current I through a pore is contributed from the electroosmotic flow, drifting motion of ions in a biasing electric field E, and diffusive motion of ions due to a concentration gradient. For a protein pore, the first contribution is negligible and theoretical predictions agree well with experimental data [4]. For the problem considered here, the last contribution is zero but the first one is significant (see below). Thus,

| (4) |

| (5) |

where e is the charge of a proton; zi and ci are the valence and number concentration of the ith ion specie, respectively. Here, μ(r) = ε(ψ(r) − ζ)/η, defined as the mobility of an electroosmotic flow according to Eq. 3. n+ and n− are number concentrations of K+ and Cl−; μ+ and μ− are electrophoretic mobilities of K+ and Cl−, respectively. Note that μ+ + μ(r) and μ− − μ(r) can be considered as effective mobilities of K+ and Cl−, respectively. Therefore, an essential effect of the surface charge of a nanopore is to renormalize electrophoretic mobilities of cat- and an-ions, resulting from an electroosmotic flow in the electric field.

Equation 5 shows that, to calculate the pore conductivity, it is necessary to obtain radial distributions of electric potentials and ion concentrations. Assuming that radius-dependent concentrations obey the Boltzmann distribution, i.e. ρ=n++n− and n± = n0e∓eψ/kBT (n0 is the number concentration of a bulk electrolyte outside the pore), one can rewrite Eq. 1 into the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation in order to obtain ψ(r), n+(r) and n−(r). After taking the steric effect of ions into account [34], the PB equation is reduced to

| (6) |

where Ψ=eψ/kBT; kB is the Boltzmann constant; T is temperature; the Debye screening length λ =(εkBT/2n0e2)1/2. In Eq. 6 α = 2a3n0, where a (~5 Å) is the radius of solvated K+ and Cl−. Corresponding boundary conditions are: Ψ′(0)=0 (without DNA) or εΨ′(RD)=−eδD/kBT (with DNA); εΨ′(R) = eδw/kBT. Here δD and δw are the surface charge densities (taking into account the screening of ions on a surface) of the DNA and the pore, respectively. δD is about 25% of the charge denisity of bare DNA [31].

After solving Eq. 6 numerically, one can obtain concentrations of ions and the velocity profile of an electroosmotic flow (see below). Surprisingly, ion concentrations inside a nanopore could be orders of magnitude higher than respective bulk concentrations, which was not considered in the phenomenological theory [28]. The ionic conductivity of a nanopore (see below) can be calculated using Eq. 5. In calculations, the viscosity of water is 8.91×10−4 Pa·S; the electrophoretic mobilities of K+ and Cl− are 76.16 nm2/(μS·mV) and 79.09 nm2/(μS·mV), respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Electroosmotic flow

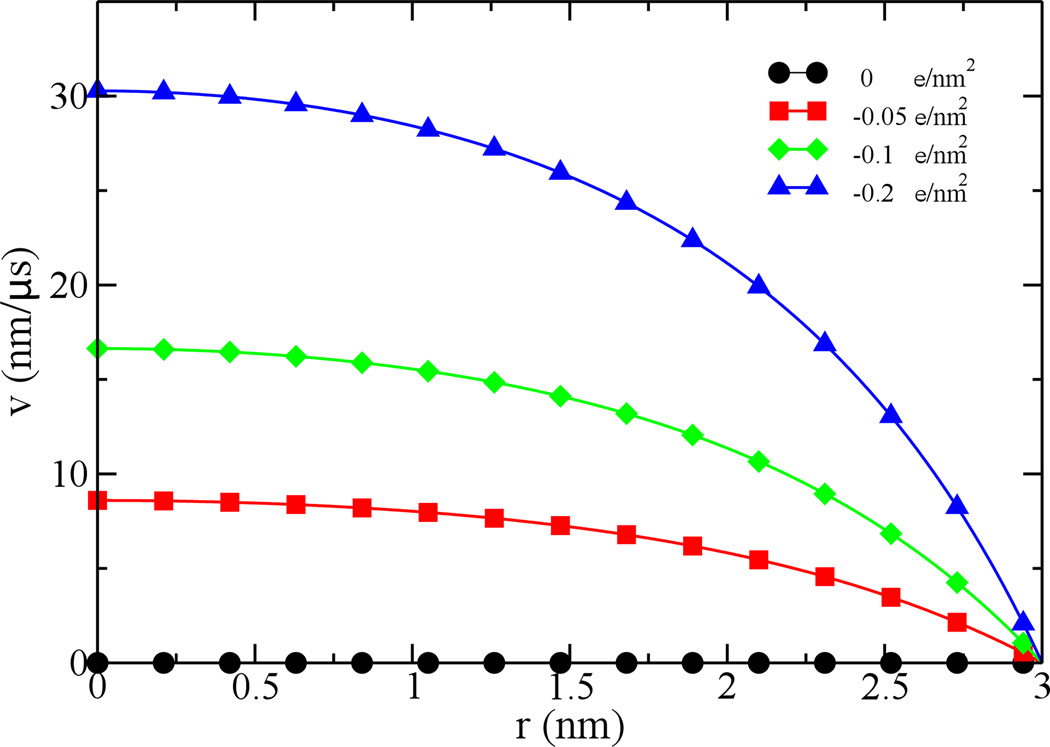

Equation 6 can be solved numerically to obtained the radial distribution of electric potentials inside the pore. Then, the velocity profile of an electroosmotic flow can be calculated using Eq. 3. When the electric field strength E is 1 mV/nm and the bulk ion concentration c (molar) is 0.1 M, Fig. 2 shows flow profiles that depend on the charge density δw of pore surface.

Figure 2.

Velocity profiles of electroosmotic flows in a 6-nm-diameter pore. The ion concentration is 0.1 M and the biasing electric field is 1 mV/nm. Surface charge density of the pore varies from 0 (dots), −0.05 (squares), −0.1 (diamonds) to −0.2 (triangles) e/nm2.

When the surface charge density is zero, as expected, there is no electroosmotic flow in the pore. With a finite surface charge density, an electroosmotic flow that is driven by screening counterions in an electric field is present inside the pore. The flow velocity is maximal at the pore center and decreases radially. At the pore surface, the flow velocity is zero. With the increase of surface charge densities, the velocity of an electroosmotic flow (defined as v(r=0)) increases. When δw=−0.2 e/nm2, the flow velocity is about 30 nm/μs. Note that electrophoretic mobilities of K+ and Cl− are 76.16 nm2/(μS·mV) and 79.09 nm2/(μS·mV), respectively. In the electric field (1 mV/nm) used for above simulations, the corresponding velocities of K+ and Cl− are about 76 nm/μS and 79 nm/μS. Therefore, velocities of electroosmotic flows are comparable to velocities of ions in the same electric field and the maximum velocity of the electroosmotic flow is about 40 % of the velocity of K+ or Cl−.

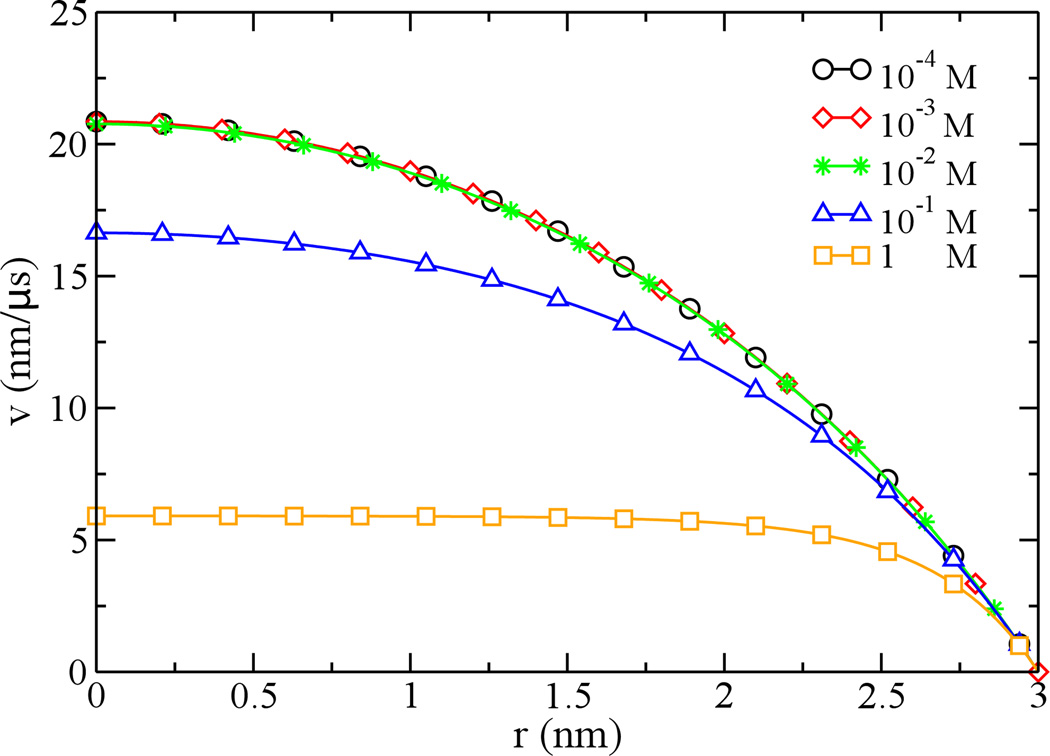

When the bulk concentration is 0.1 M, the Debye length is about 1 nm that is less than the pore radius (3 nm). At a lower ion concentration (<0.01 M), the Debye length can be larger than the pore radius. Thus the ionic screening of surface charge are different for low- and high-concentration cases. Fig. 3 shows velocity profiles of different electroosmotic flows whose bulk ion concentrations vary from 10−4 to 1 M. For these cases, the surface charge density is fixed and is −0.1 e/nm2.

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent velocity profiles of electroosmotic flows in the nanopore. The surface charge density of the pore is −0.1 e/nm2. Bulk ion concentrations vary from 0.0001 (cycles), 0.001 (diamonds), 0.01 (stars), 0.1 (triangles) to 1 (squares) M. The field strength is 1 mV/nm.

At the concentration of 1 M (Debye length ~ 0.3 nm), most screening counterions reside near the pore surface. The induced electroosmotic flow in the electric field (1 mV/nm) is slow due to the surface friction. At a lower ion concentration (0.1 M), screening counterions can be present further away from the surface and the flow velocity is accordingly larger. When the bulk ion concentration is less than 0.01 M (Debye length > pore radius). Interestingly, the velocity profile of a flow becomes constant, independent on the bulk ion concentration. This is due to the fact that at low bulk ion concentrations the distribution of screening ions of a charged pore is limited by the pore size.

3.2. Ion concentrations inside a pore

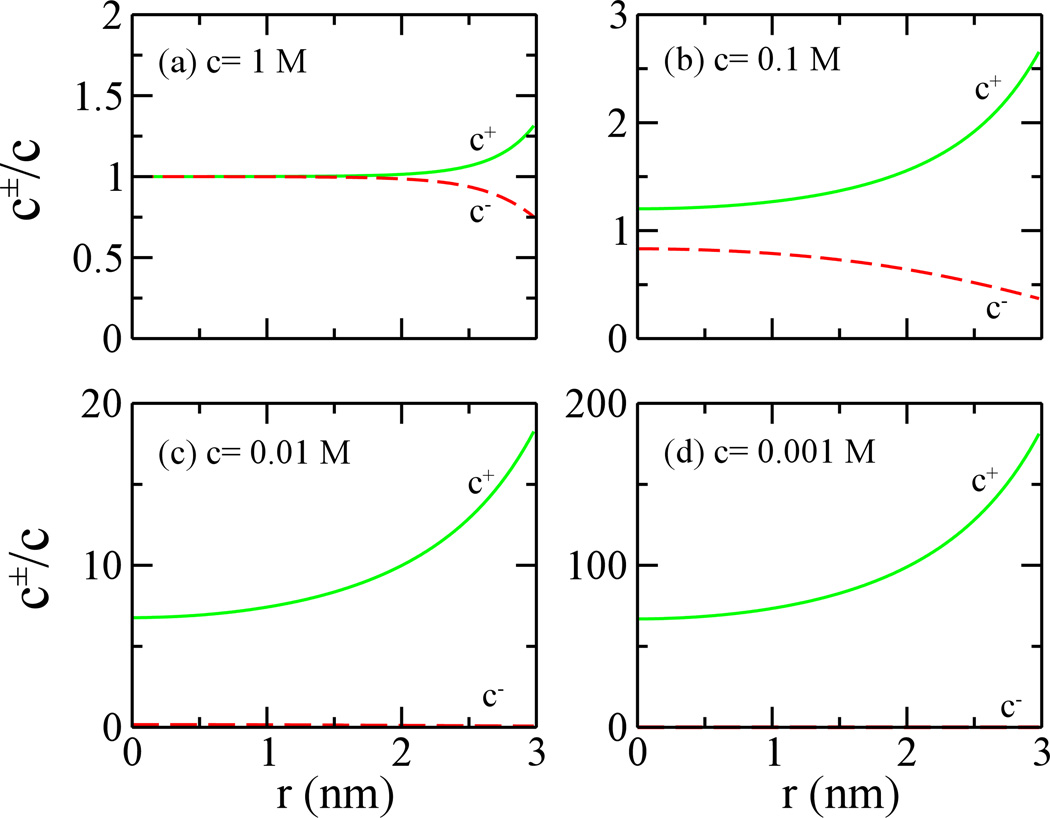

Since the electroosmotic flow results from driven motion of ions in an electric field near a charged surface, distributions of counter- and co-ions are essential to determine the flow profile and velocity. In Fig. 4, radial distributions of counter- and co-ions are shown. With the bulk molar concentration c of 1 M, concentrations of counter- and co-ions, that are several angstroms away from the charged surface, approach the bulk value (Fig 4a). Only within the Debye length of 0.3 nm, the molar concentration c+ of counter-ions (K+) is larger than that c− of co-ions (Cl−). At a lower bulk concentration (0.1 M), concentration of counter-ions near the pore surface is much higher than that of co-ions (Fig. 4b). Limited by the pore size, concentrations of counter- and co-ions are always higher and lower than the bulk concentration, respectively.

Figure 4.

Normalized ion distributions in the nanopore. The surface charge density is −0.1 e/nm2. Bulk molar concentrations c of ions are 1 M (a), 0.1 M (b), 0.01 M (c) and 0.001 M (d). c+ (solid lines) and c− (dashed lines) are concentrations of counterions and coions inside the pore, respectively.

When the bulk concentrations of electrolytes are 0.01 and 0.001 M, their respective Debye lengths are about 3 nm and 10 nm. Figure 4c and 4d show that concentration of co-ions are significantly lower than that of counter-ions. Especially for the bulk concentration of 0.001 M, coions are depleted inside the pore and the concentration of counter-ions can be two-orders of magnitude higher than the bulk value. When the bulk concentration is even lower (R ≪ λ), the distribution of counter-ions barely changes (Fig. 4c and 4d, or see Fig. 5 below) and is characterized by the pore size, not by the Debye length. Therefore, profiles of induced electroosmotic flows in the same electric field are same when the bulk concentration of ions is low enough (Fig. 3).

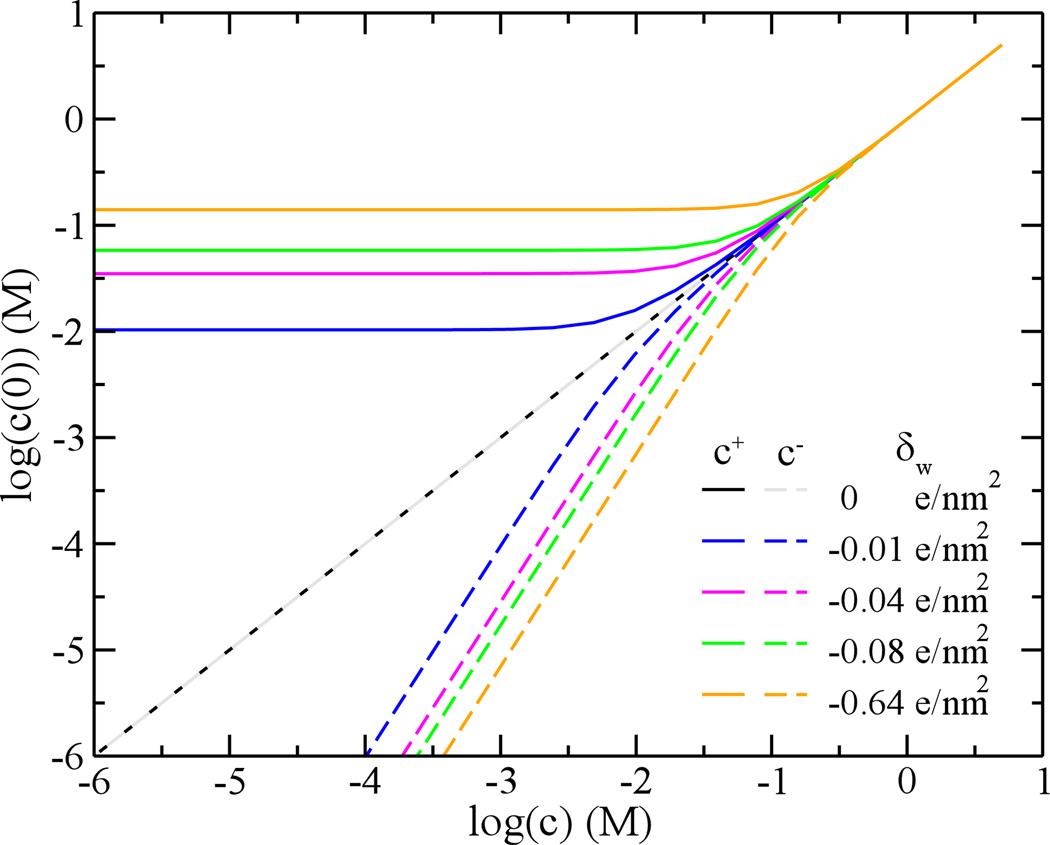

Figure 5.

Comparisons between ion concentrations at the pore center (r=0) and bulk ion concentrations. The surface charge density changes from 0 (black and gray), −0.01 (blue), −0.04 (pink), −0.08 (green) to −0.64 (orange) e/nm2. c+ (solid lines) and c− (dashed lines) are molar concentrations of counterions and coions inside the pore, respectively. The bulk molar concentration is c.

Figure 5 demonstrates the relation between the ion concentration inside the pore and the bulk concentration c. For simplicity, only ion concentrations at the pore center, c+(0) and c−(0), are compared against c. For a neutral pore (δw=0 e/nm2), Fig. 5 shows the relation that c+(0)=c−(0)=c. When the pore surface is charged, such relation is still satisfied at a high ion concentration (e.g. 1 M), because of a smaller Debye screening length. For a low bulk concentration (< 1mM), the counter-ion concentration c+(0) can be orders of magnitude higher than c while the co-ion concentration c−(0) can be orders of magnitudes lower than c (or co-ions are depleted). For example, when c=1 mM, the counterion concentration c+(0) is about 100 times higher than the bulk concentration c. It is also noted that the counter-ion concentration becomes constant when the bulk concentration of ions c is low enough, consistent with results shown in Fig. 4c and 4d.

3.3. Signals of ionic current in a neutral nanopore

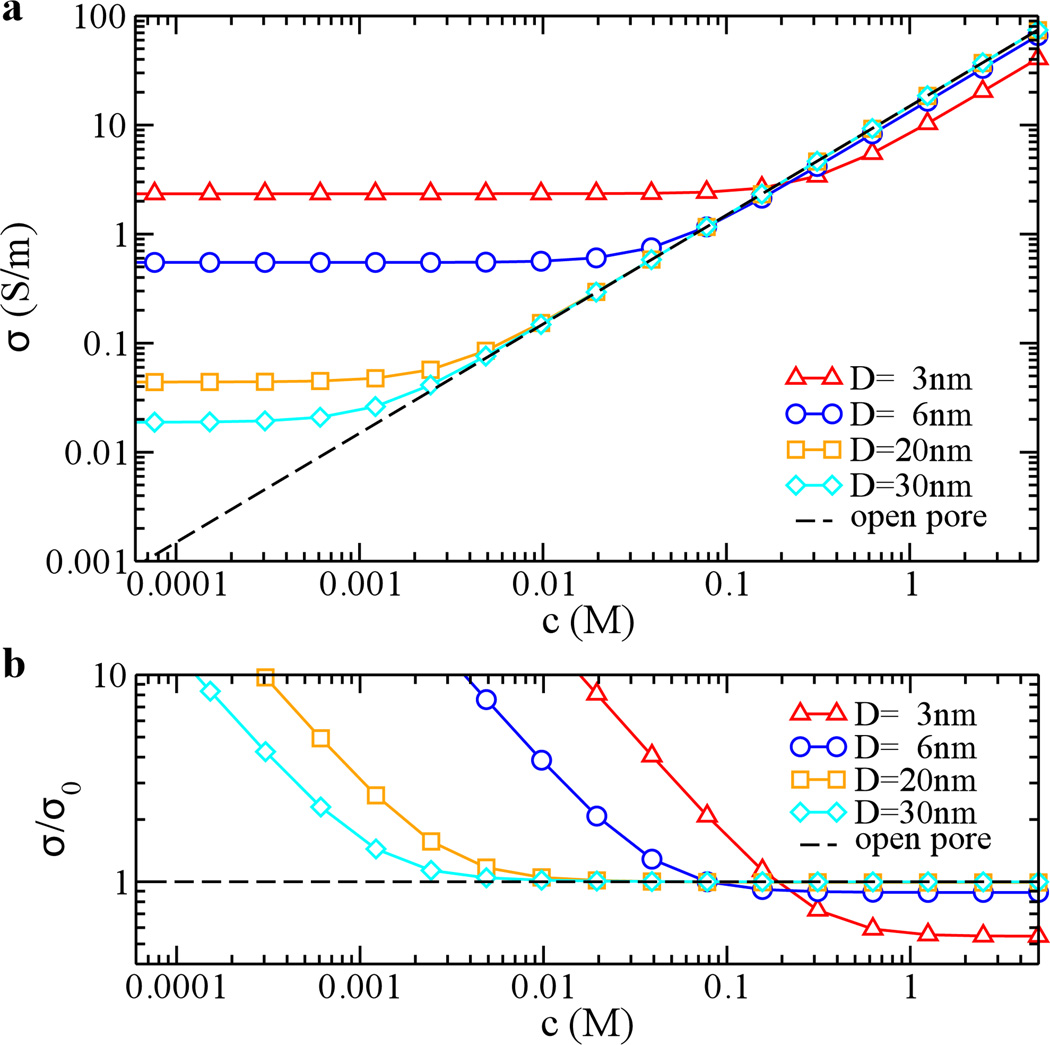

Figure. 6 shows how conductivity depends on the bulk molar concentration c when the surface of a nanopore is neutral. Without DNA translocation, the conductivity decreases linearly with the bulk concentration and is independent on the pore size. With the DNA translocation, the conductivity of the pore is lower than the open-pore conductivity σ0 at high bulk concentrations and is higher than σ0 at low bulk concentrations, as shown in Fig. 6a. This crossover behavior defines a critical bulk concentration nc at which σ = σ0, i.e. no CB or CE. nc decreases with an increase of the pore size (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

Concentration-dependent ionic conductivity of a neutral nanopore (δw=0) with or without DNA translocation. (a) conductivity; (b) relative conductivity with respect to the open-pore one (σ0). Diameters of pores are 3 (triangle), 6 (circle), 20 (square) and 30 (diamond) nm. Dashed lines show the open-pore conductivity (a) and the relative conductivity (b).

When DNA enters a pore, it not only brings in counterions but also physically excludes ions from a pore. At a high bulk concentration (> nc), the number of ions excluded could be much more than the number of counterions DNA brings in. Additionally, the flow of water is in the direction of DNA motion and opposite the direction of motions of screening-ions; the effective mobility (see above) of K+ is less. Thus, a net CB effect is expected. When increasing the pore size, the effect of CB becomes negligible. At bulk concentrations much lower than nc, the number of ions screening the charge of DNA inside the pore could be larger than the number of ions excluded by DNA, resulting in CE. Therefore, the conductivity is dominated by counterions of DNA and is independent on the bulk concentration (Fig. 6a). Since σ0 decreases with the bulk concentration and σ saturates at low bulk concentrations, Fig. 6b shows that the enhanced conductivity can be an order of magnitude higher than the open-pore conductivity.

3.4. Signals of ionic current in a charged nanopore

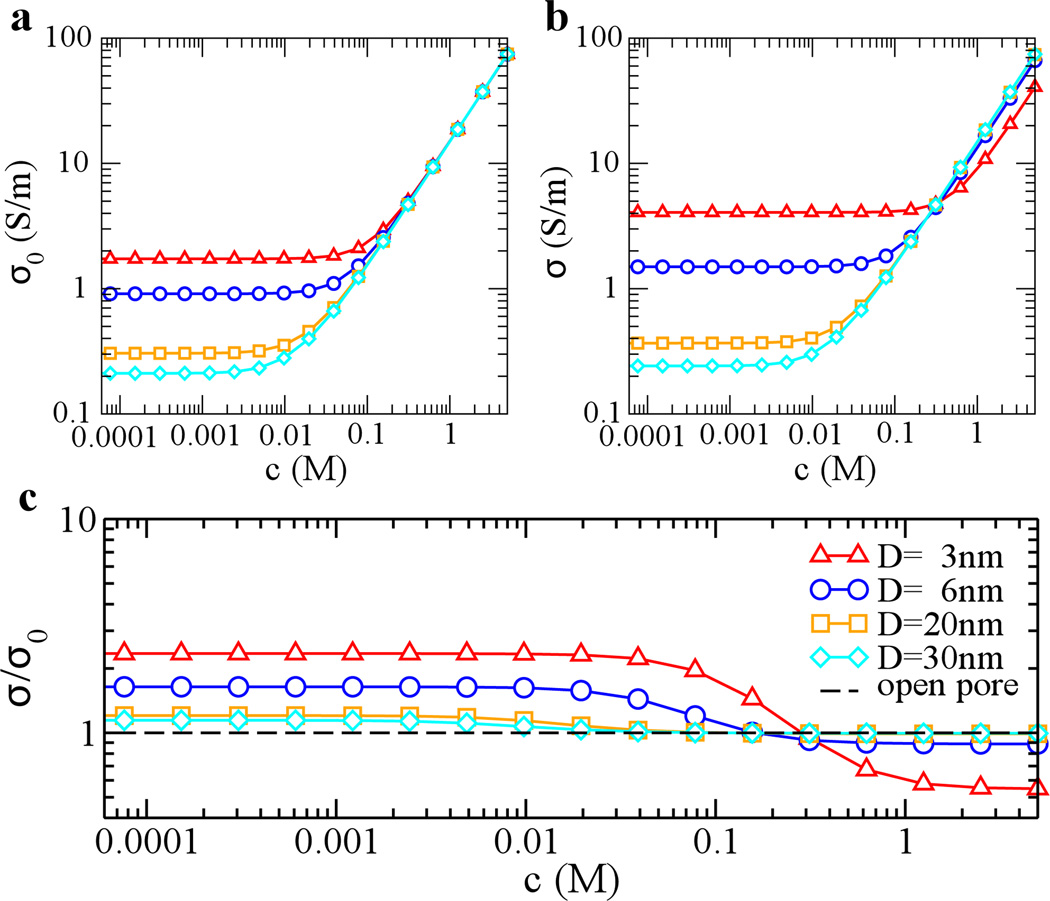

Figure 7a shows conductivities of open-pores whose surface charge densities are −0.1 e/nm2. Similar to effects on the pore conductivity caused by DNA surface charges (Fig. 6), a charged nanopore surface can also cause pore conductivities to be saturated at low bulk concentrations. In this region, the open-pore conductivity is contributed mainly from screening ions of a charged pore surface. The pore current is proportional to the number of ions screening the charged surface, therefore Iopen ~ D. The conductivity of a pore is proportional to the current density. Thus σ ~ D−1. As shown in Fig. 7a, saturated open-pore conductivities decrease with the increase of pore diameters. A comparison between theoretical predictions and experimental data [35] was provided in supplementary data.

Figure 7.

Concentration-dependent ionic conductivity of a charged nanopore (δw= −0.1 e/nm2) with or without DNA translocation. (a) open-pore conductivity σ0; (B) pore conductivity with DNA translocation σ; (c) relative conductivity. Diameters of pores are 3 (triangle), 6 (circle), 20 (square) and 30 (diamond) nm. The dashed line in (c) shows the result for an arbitrary open pore.

In the limit of high concentrations, c+(r) ≈ c−(r) ≈ c, since the Debye length is very small. Thus, electroosmotic effects on the pore conductivity from cations and anions cancel out. Therefore Eq. 5 is reduce to σ = (μ+ + μ−)ec. In the limit of low concentrations, c−(r) ≈0 for a negatively charged nanopore. When μ(r)/μ+ ≪ 1 and the entire system (including a pore and an electrolyte) is neutral, we can rewrite Eq. 5 into σ = 2μ+|δw|/R. Previously, the phenomenological model [28] combining above two contributions, i.e. σ = (μ+ + μ−)ec + 2μ+|δw|/R, was proposed. Therefore, that model is the limiting case of our electro-hydrodynamics model. Note that μ(r)/μ± is not always negligibly small and can be as large as 0.4 when δw= −0.2 e/nm2 (Supporting Information). Detailed comparisons between the phenomenological and our models are shown in Supporting Information.

When DNA transits a negatively charged nanopore, DNA brings in extra counterions. Therefore, at low bulk concentrations, saturated values of pore conductivities are systematically higher than those for open-pores, resulting in CE (Fig. 7b). At high bulk concentrations, the current blockage happens as excluded ions by DNA from an electrolyte outnumbers screening ions for both DNA and the pore surface. Figure 7c shows that when the bulk concentration decreases, the pore conductivity changes from a blockage to an enhancement. However, unlike the case of a neutral pore, σ/σ0 becomes constant at low bulk concentrations. Thus, the enhanced current is at most 2–3 times larger than the open-pore current.

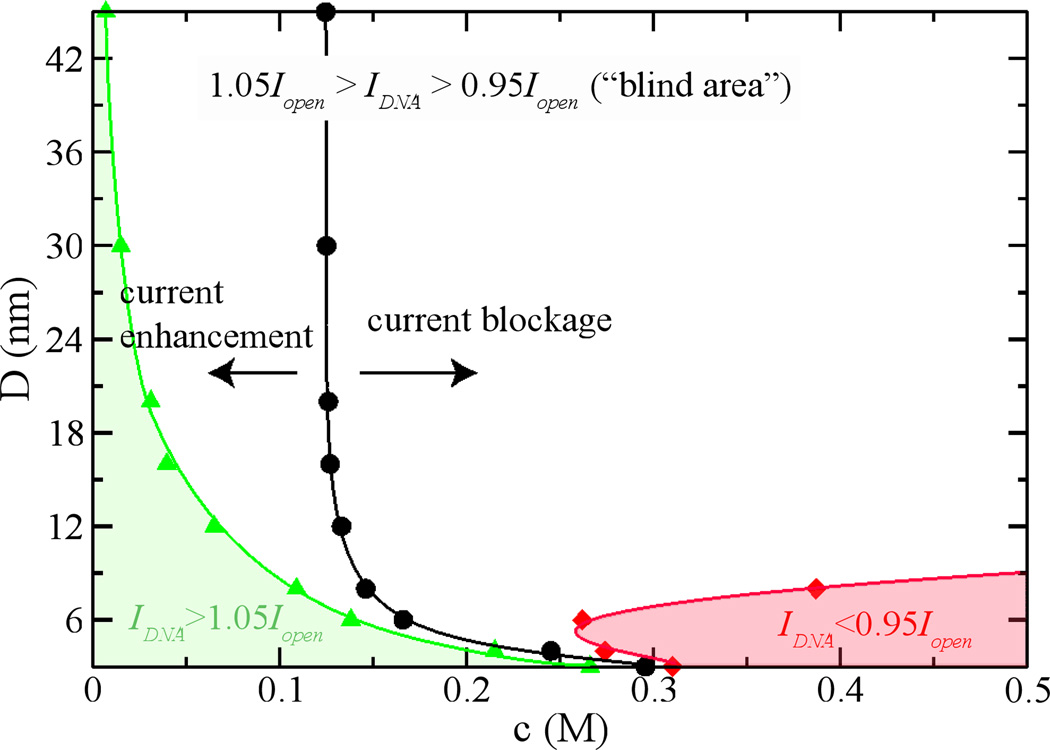

For each pore size, the critical concentration nc can be determined from Fig. 7. For a fixed surface charge density −0.1 e/nm2, Fig. 8 shows the dependence of CE or CB on both the pore size and the bulk concentration. The current blockage occurs only when c > nc. It is noted that nc decreases with the increase of pore sizes and saturates for large pores. If the current fluctuation (such as current noise or the drift of an open-pore current) is ±5% of an open-pore current,, the CB is measurable when IDNA < 0.95 Iopen (red and shaded region in Fig. 8) and the CE is measurable when IDNA > 1.05Iopen (green and shaded region in Fig. 8). A “blind area” is outside of these two regions where signals of DNA translocation are covered by noise (Supporting Information). Therefore, for a lager pore (D > 15 nm), it is difficult to detect DNA translocation in a high-concentration electrolyte but is possible to detect CE signals in a low-concentration electrolyte.

Figure 8.

The dependence of current change induced by DNA-translocation on a pore diameter and a bulk ion concentration. The surface charge density of each pore is −0.1 e/nm2. In the green and shaded area, the current with DNA translocation (IDNA) is at least 5% higher than the open-pore current Iopen. In the red and shaded area, IDNA is at least 5% less than Iopen.

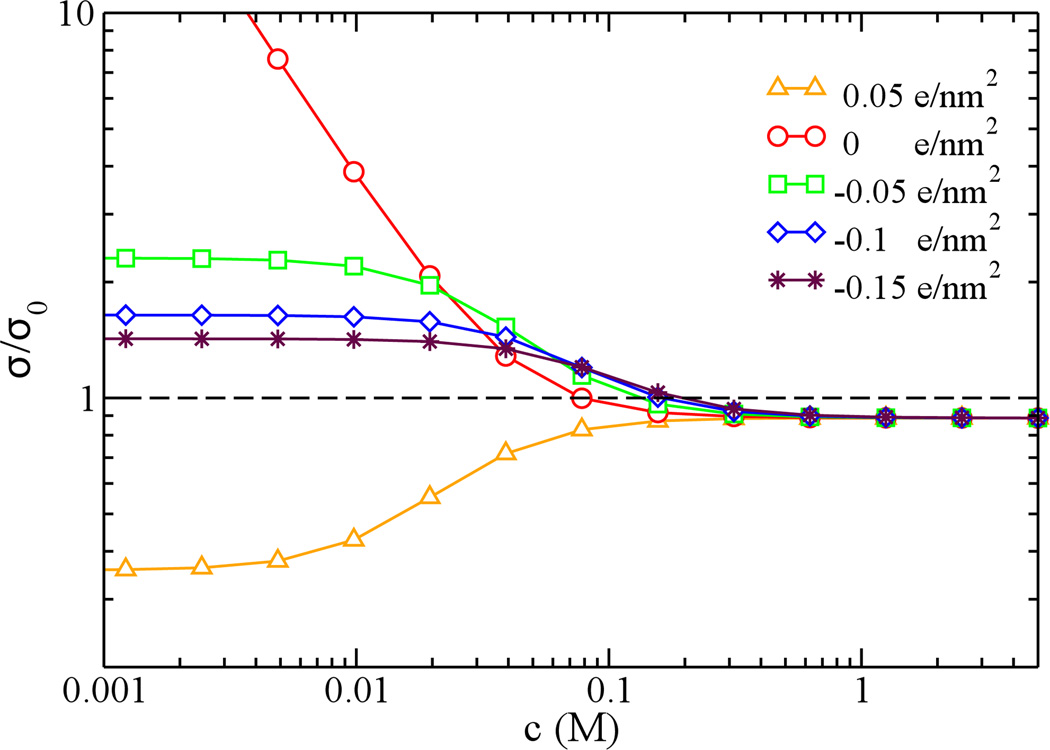

3.5. Effects of surface charge density

Besides the pore size and the electrolyte concentration, the surface charge density δw can also affect the current signal of DNA translocation, as shown in Fig. 9. Due to the strong screening effect at a high ion concentration (> 1 M), pore conductivities are independent on δw. At a low ion concentration, when δw is less negative, σ0 becomes smaller and σ/σ0 increases. When the surface is neutral, as discussed before, σ/σ0 is even larger at a low bulk concentration and the signal of CE is increased.

Figure 9.

The dependence of relative conductivities on bulk concentrations for a 6-nm pore. The surface charge density varies from −0.15, −0.1, −0.05, 0, to 0.05 e/nm2.

Interestingly, when δw is positive, only current blockage occurs as shown in Fig. 9. This is due to the fact that DNA acts like a “macro”-counterion for a positively charged pore while the positive pore plays the role of screening ions of DNA. This effect dramatically reduced number of ions in the pore, causing the CB only.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In summary, using an electro-hydrodynamics model, we have demonstrated how current signals of DNA translocation in a nanopore can be affected by the pore size, ion concentration and surface charge density of a pore. A phase diagram was provided to show regions of CE and CB. In recent theoretical and experimental studies, metal electrodes were present near a nanopore to gate an ionic current [36], to control the DNA motion [37] and to detect a DNA nucleotide [38]. They require a low-concentration electrolyte in a nanopore to avoid the ion-screening of electrodes. Thus CE signals of DNA translocation are preferred.

We also suggested a possible “blind” region where DNA translocation occurs but cannot be detected by monitoring the pore current. To avoid this, it is possible to use a high ion concentration for a small pore (to have CB) or use a low ion concentration for a large pore (to have CE). Additionally, one can modify the surface charge density (e.g. by tuning the pH value of an electrolyte [36]) to expand the region of CE or CB in the diagram (Fig. 8). Finally, this work clarifies the role of an electroosmotic flow in a pore and provides the physical understanding of the CE and CB in terms of coupled electric and hydrodynamic effects.

It should be noted that our model does not include any direct physical interaction between DNA and the surface of a pore. It was experimentally and theoretically shown that such interaction can affect the polymer translocation [39, 40, 41]. Such interaction was also investigated using molecular dynamics simulations [42]. Simulation results showed that it is possible, by chemically modifying the pore surface [43], to reduce such interaction and confine DNA near the pore center [42]. Additionally, chemical interaction (such as different protonation states at different PH values) can modify the surface charge density and affect measured signals of ionic currents, as shown in previous experimental and theoretical studies [44, 45, 36]. Beyond the continuum modeling, simulation methods such as brownian dynamics [46] can be used to study the ionic conductance of a nanopore that has a nonuniform distribution of surface charges and/or an irregular (such as non-cylindrical) surface shape.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Authors gratefully acknowledge useful discussions with Sungwook Nam, Steve Rossnagel, Ajay Royyuru and members in the IBM DNA transistor team. This work is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HG05110-01).

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Comparison between the electrohydrodynamic model and the phenomenological model; comparison between theoretical predictions and experimental data; percentage change of an ionic current during DNA translocation.

References

- 1.Venkatesan BM, Bashir R. Nanopore sensors for nucleic acid analysis. Nature Nanotech. 2011;6(10):615–624. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasianowicz JJ, Robertson JW, Chan ER, Reiner JE, Stanford VM. Nanoscopic porous sensors. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008;1:737–766. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson Joseph WF, Rodrigues Claudio G, Stanford Vincent M, Rubinson Kenneth A, Krasilnikov Oleg V, Kasianowicz John J. Single-molecule mass spectrometry in solution using a solitary nanopore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8207–8211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611085104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiner JE, Kasianowicz JJ, Nablo BJ, Robertson JWF. Theory for polymer analysis using nanopore-based single-molecule mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:12080–12085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002194107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Zheng D, Tan Q, Wang MX, Gu LQ. Nanopore-based detection of circulating micrornas in lung cancer patients. Nature Nanotech. 2011;6(10):668–674. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanunu M, Dadosh T, Ray V, Jin J, McReynolds L, Drndić M. Rapidelectronicdetection of probe-specific micrornas using thin nanopore sensors. Nature Nanotech. 2010;5(11):807–814. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niedzwiecki DJ, Grazul J, Movileanu L. Single-molecule observation of protein adsorption onto an inorganic surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010 doi: 10.1021/ja1026858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusko EC, Johnson JM, Majd S, Prangkio P, Rollings RC, Li J, Yang J, Mayer M. Controlling protein translocation through nanopores with bio-inspired fluid walls. Nature Nanotech. 2011;6(4):253–260. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Q, Sigalov G, Dimitrov V, Dorvel B, Mirsaidov U, Sligar S, Aksimentiev A, Timp G. Detecting snps using a synthetic nanopore. Nano Lett. 2007;7(6):1680–1685. doi: 10.1021/nl070668c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornblower B, Coombs A, Whitaker RD, Kolomeisky A, Picone SJ, Meller A, Akeson M. Single-molecule analysis of dna-protein complexes using nanopores. Nat. Methods. 2007;4(4):315–317. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall AR, van Dorp S, Lemay SG, Dekker C. Electrophoretic force on a protein-coated dna molecule in a solid-state nanopore. Nano letters. 2009;9(12):4441–4445. doi: 10.1021/nl9027318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aksimentiev A. Deciphering ionic current signatures of dna transport through a nanopore. Nanoscale. 2010;2(4):468–483. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00275h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthukumar M. Polymer Translocation. Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oukhaled G, Mathe J, Biance AL, Bacri L, Betton JM, Lairez D, Pelta J, Auvray L. Unfolding of proteins and long transient conformations detected by single nanopore recording. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98(15):158101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.158101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oukhaled A, Cressiot B, Bacri L, Pastoriza-Gallego M, Betton JM, Bourhis E, Jede R, Gierak J, Auvray L, Pelta J. Dynamics of completely unfolded and native proteins through solid-state nanopores as a function of electric driving force. ACS nano. 2011;5(5):3628. doi: 10.1021/nn1034795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merstorf C, Cressiot B, Pastoriza-Gallego M, Oukhaled A, Betton JM, Auvray L, Pelta J. Wild type, mutant protein unfolding and phase transition detected by single-nanopore recording. ACS Chem. Bio. 2012;7(4):652–658. doi: 10.1021/cb2004737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fologea Daniel, Ledden Bradley, McNabb David S, Li Jiali. Electrical characterization of protein molecules by a solid-state nanopore. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;91:053901–053903. doi: 10.1063/1.2767206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei R, Gatterdam V, Wieneke R, Tampé R, Rant U. Stochastic sensing of proteins with receptor-modified solid-state nanopores. Nature Nanotech. 2012;7(4):257–263. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Branton D, Deamer DW, Marziali A, Bayley H, Benner SA, Butler T, Di Ventra M, Garaj S, Hibbs A, Huang X, et al. The potential and challenges of nanopore sequencing. Nature Biotech. 2008;26:1146–1153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. Characterization of individual polynucleotide molecules using a membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meller A, Nivon L, Brandin E, Golovchenko J, Branton D. Rapid nanopore discrimination between single polynucleotide molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1079–1084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke J, Wu HC, Jayasinghe L, Patel A, Reid S, Bayley H. Continuous base identification for single-molecule nanopore DNA sequencing. Nature Nanotech. 2009;4(4):265–270. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derrington IM, Butler TZ, Collins MD, Manrao E, Pavlenok M, Niederweis M, Gundlach JH. Nanopore dna sequencing with mspa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(37):16060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001831107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells DB, Belkin M, Comer J, Aksimentiev A. Assessing graphene nanopores for sequencing dna. Nano Lett. 2012 doi: 10.1021/nl301655d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balagurusamy VSK, Weinger P, Sean Ling X. Detection of dna hybridizations using solid-state nanopores. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:335102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/33/335102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fologea D, Uplinger J, Thomas B, McNabb DS, Li J. Slowing DNA translocation in a solid-state nanopore. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1734–1737. doi: 10.1021/nl051063o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wanunu M, Sutin J, Meller A. Dna profiling using solid-state nanopores: detection of dna-binding molecules. Nano Lett. 2009;9(10):3498–3502. doi: 10.1021/nl901691v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smeets RMM, Keyser UF, Krapf D, Wu MY, Dekker NH, Dekker C. Salt dependence of ion transport and DNA translocation through solid-state nanopores. Nano Lett. 2006;6:89–95. doi: 10.1021/nl052107w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirsaidov U, Timp W, Zou X, Dimitrov V, Schulten K, Feinberg AP, Timp G. Nanoelectromechanics of methylated dna in a synthetic nanopore. Biophys. J. 2009;96(4):L32–L34. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luan BQ, Aksimentiev A. Electro-osmotic screening of the DNA charge in a nanopore. Phys. Rev. E. 2008;78:021912. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.021912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dorp S, Keyser UF, Dekker NH, Dekker C, Lemay SG. Origin of the electrophoretic force on DNA in solid-state nanopores. Nature Phys. 2009;5:347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosal Sandip. Electrokinetic-flow-induced viscous drag on a tethered dna inside a nanopore. Phys. Rev. E. 2007;76(6):061916. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.061916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosal S. Effect of salt concentration on the electrophoretic speed of a polyelectrolyte through a nanopore. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:238104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.238104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borukhov I, Andelman D, Orland H. Steric effects in electrolytes: A modified poisson-boltzmann equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;79(3):435–438. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nam SW, Rooks MJ, Kim KB, Rossnagel SM. Ionic field effect transistors with sub-10 nm multiple nanopores. Nano Lett. 2009;9(5):2044–2048. doi: 10.1021/nl900309s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang Z, Stein D. Charge regulation in nanopore ionic field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. E. 2011;83(3):031203. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.031203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polonsky S, Rossnagel S, Stolovitzky G. Nanopore in metal-dielectric sandwich for DNA position control. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;91:153103. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsutsui M, Taniguchi M, Yokota K, Kawai T. Identifying single nucleotides by tunnelling current. Nature Nanotech. 2010;5:286–290. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wanunu M, Sutin J, McNally B, Chow A, Meller A. Dna translocation governed by interactions with solid-state nanopores. Biophys. J. 2008;95(10):4716–4725. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.140475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lubensky DK, Nelson DR. Driven polymer translocation through a narrow pore. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1824–1838. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77027-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I, Brutyan RA, Kasianowicz JJ. Dynamics and free energy of polymers partitioning into a nanoscale pore. Macromolecules. 1996;29(26):8517–8522. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luan B, Afzali A, Harrer S, Peng H, Waggoner P, Polonsky S, Stolovitzky G, Martyna G. Tribological Effects on DNA Translocation in a Nanochannel Coated with a Self-Assembled Monolayer. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114(51):17172–17176. doi: 10.1021/jp108865q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wanunu M, Meller A. Chemically modified solid-state nanopores. Nano Lett. 2007;7(6):1580–1585. doi: 10.1021/nl070462b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bezrukov SM, Kasianowicz JJ. Current noise reveals protonation kinetics and number of ionizable sites in an open protein ion channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993;70:2352–2355. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasianowicz JJ, Bezrukov SM. Protonation dynamics of the α-toxin ion channel from spectral analysis of ph dependent current fluctuations. Biophys. J. 1995;69:94–105. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79879-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu Noskov S, Im W, Roux B. Ion permeation through the α-hemolysin channel: Theoretical studies based on Brownian Dynamics and Poisson-Nernst-Plank electrodiffusion theory. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2299–2309. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.