Abstract

The embryonic development of the olfactory nerve includes the differentiation of cells within the olfactory placode, migration of cells into the mesenchyme from the placode, and extension of axons by the olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs). The coalition of both placode-derived migratory cells and OSN axons within the mesenchyme is collectively termed the “migratory mass.” Here we address the sequence and coordination of the events that give rise to the migratory mass. Using neuronal and developmental markers, we show subpopulations of neurons emerging from the placode by embryonic day (E) 10, a time at which the migratory mass is largely cellular and only a few isolated OSN axons are seen, prior to the first appearance of OSN axon fascicles at E11. These neurons also precede the emergence of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and ensheathing glia which are also resident in the mesenchyme as part of the migratory mass beginning at about E11. The data reported here begin to establish a spatiotemporal framework for the migration of molecularly heterogeneous placode-derived cells in the mesenchyme. The precocious emigration of the early arriving neurons in the mesenchyme suggests they may serve as “guidepost cells” that contribute to the establishment of a scaffold for the extension and coalescence of the OSN axons.

INDEXING TERMS: olfactory placode, development, axon guidance, migratory mass

The embryonic development of the olfactory nerve encompasses a series of coordinated events: 1) the differentiation of cells within the olfactory placode (OP); 2) the migration of cells into the mesenchyme from the placode; 3) the extension of olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) axons into the mesenchyme; and 4) the final approach of OSN axons to the basal telencephalon, the site of the presumptive olfactory bulb (pOB). Of interest here, the migration of cells out of the placode may help coordinate the formation of a molecular topography between the OSNs in the olfactory epithelium (OE) and the olfactory bulb (OB; Conzelmann et al., 2002; Schwarzenbacher et al., 2004, 2006).

The first OSN axons extend across the basal lamina into the mesenchyme beginning at late embryonic day (E)10 in the mouse (Cuschieri and Bannister, 1975). A few axons penetrate the telencephalon around E11.5 (Hinds, 1972; Cuschieri and Bannister, 1975; Doucette, 1989), but most remain outside; the first OSN axon synapses do not appear until several days later, at E14 (Hinds and Hinds, 1976). OSN axons do not migrate from the placode to the pOB in isolation; they are accompanied by a population of migratory cells (Marin-Padilla and Amieva, 1989; Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Valverde et al., 1992). The migrating cells and extending axons are collectively termed the “migratory mass” (MM; Valverde et al., 1992). Heterogeneous populations of cells are found within the MM, including the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons and the olfactory ensheathing glia/cells (OECs).

GnRH+ neurons migrate from a specialized region of the placode, the nascent vomeronasal organ (VNO), beginning at E11.5 and travel across the nasal septum along the vomeronasal and terminal nerves (Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Wray et al., 1989; Schwarting et al., 2007). GnRH+ neurons enter the forebrain and migrate to their final destination, the septal-preoptic area and hypothalamus (Schwarting et al., 2007). OECs are believed to migrate from the main olfactory placode (OP), and are found within the nascent olfactory nerve as early as E10.5 (Marin-Padilla and Amieva, 1989; Valverde et al., 1992; Chuah and Au, 1993).

Another population of migrating cells, which are GnRH−, express olfactory marker protein (OMP; Baker and Farbman, 1993; Valverde et al., 1993; Conzelmann et al., 2002). The OMP+ cells are primarily clustered in the ventrolateral MM, and appear closely apposed to OSN axon fascicles, mirroring their trajectory (Valverde et al., 1993; Tarozzo et al., 1995).

Within the MM there are also cells expressing odor receptors (ORs; Leibovici et al., 1996; Nef et al., 1996). The OR+ cells are also OMP+, suggesting there is some, although not complete, overlap of these two populations. The OR+/OMP+ cells may be candidates for providing guidance cues to OSN axons extending toward the telencephalon (Conzelmann et al., 2002; Schwarzenbacher et al., 2004, 2006).

Additional populations of cells exiting the placode include cells expressing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and β-tubulin III, which migrate and spread broadly over the surface of the rat telencephalon (De Carlos et al., 1995). Further markers attributed to cells exiting the placode include NCAM, GAP43, Dlx5, Six1, and VGlut2, but their fates are unknown (Schwanzel-Fukuda et al., 1992; Pellier et al., 1994; Honma et al., 2004; Ikeda et al., 2007; Merlo et al., 2007).

Both the chick and zebrafish show evidence of migratory populations of cells that may promote the establishment of the olfactory nerve. In zebrafish pioneer neurons differentiate prior to the OSNs and while their somata remain resident within the olfactory placode, their axons form the initial connections with the telencephalon (Whitlock and Westerfield, 1998). Of interest, the pioneer neurons arise in a distinct section of the neural plate and differ morphologically and molecularly from OSNs. Following the development of OSN axons, the pioneer neurons undergo apoptosis.

The early migratory cells in chicks appear similar to those described in mice. Neuronal precursors, which later express GnRH, migrate from the neuroepithelium into the mesenchyme at the placodal stage, prior to the invagination of the placode to form the olfactory pit (Fornaro et al., 2001, 2003).

In the human, “pioneer neurons” expressing β-tubulin III and Tbr1 were identified both within the placode and the mesenchyme after crossing the basal lamina of the placode (Bystron et al., 2006). They contributed to the formation of a fibrous network within the mesenchyme, extending from the placode to the basal telencephalon, where the pOB will later emerge.

Despite advances in describing the organization of the MM, fundamental questions remain: 1) Which first exit the placode, OSN axons or migratory cells? 2) Do migratory neurons, or OECs, establish a path for growing axons? 3) Is the molecular diversity of migratory cells established prior to exiting the placode? 4) Do all cells simultaneously exit the placode, or do subpopulations exhibit spatiotemporal migratory diversity?

To begin addressing these questions, we employed a panel of molecular probes to identify the subpopulations of cells emerging from the placode and nascent epithelium, and coordinated our analyses with the extension of the OSN axons into the mesenchyme and their approach to the telencephalon. Our data demonstrate the diversity of placode-derived migratory cells and establish the temporal framework for the development of the olfactory nerve. We show that while the MM is primarily cellular during its initial development, there are a few isolated axons that appear to exit the placode synchronously with the MM cells. However, the coordinated emergence of large numbers of OSN axons and the formation of axon fascicles does not occur until after the first cells migrate from the placode into the mesenchyme. The serial migration of cells from the placode followed by the emergence of OSN axons forming fascicles supports the hypothesis that placode-derived migratory cells contribute to a scaffold or framework for extending OSN axons. We propose that the molecular diversity of migratory cells within this framework likely contributes to axon sorting and the initial topography between the OE and the OB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Pregnant, time-mated CD-1 (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) and doublecortin green fluorescent protein (DCX-GFP) mice were euthanized with CO2. The DCX-GFP mice (GENSAT BAC transgenic, strain name STOCK Tg(Dcx-EGFP)1Gsat/Mmmh) were a kind gift of Dr. Angelique Bordey (Whitman et al., 2009). They were developed by injecting multiple copies of a BAC containing EGFP upstream of the coding sequence of DCX into the pronuclei of FVB/N fertilized oocytes. Hemizygous progeny were mated to Swiss Webster mice (Gong et al., 2003). Pregnant dams were ordered from Charles River and embryos were collected by cesarean section at gestational days 9.5, 10, 10.5, 11, 11.5, 12, 12.5, and 13 (vaginal plug = day 0). Embryos were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 0.1 M phosphate buffer [PB] and 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight; tissue for Lhx2 labeling (see Table 1) was fixed for 1 hour. After fixation, tissue was washed in PBS overnight. Staging to determine embryonic age, as described by Theiler (1989), was employed as an independent measure of gestational age. Both the Theiler stage and the embryonic age (based on appearance of vaginal plug) are correlated, as shown in Figure 1. Subsequently, embryonic ages are reported in order to be consistent with the literature. For the DCX-GFP mice, timed pregnancies were set up in the Yale Animal Facilities and the age of the embryo was designated accordingly (vaginal plug = day 0). Tissue was cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C, embedded in O.C.T. (Tissue-Tek; Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IN), frozen in cryo-molds at −70°C and kept there until needed. Embryonic specimens were sagittally sectioned at 20 μm using a cryostat (Reichert-Jung 2800 Frigocut E) and thaw-mounted onto SuperFrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), air-dried, and stored at −20°C until needed.

TABLE 1.

Primary Antibodies

| Antiserum | Immunogen | Source (cat. no.) | Working dilution | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goat polyclonal anti-doublecortin (DCX) | Synthetic peptide corresponding to AA 385–402 at the c-terminus of human doublecortin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA (SC-8066) | 1:500 | A single band at 40 kDa was detected on a Western blot of adult rat olfactory bulb.(Brown et al., 2003). |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-growth associated protein 43 (GAP-43) | Synthetic peptide corresponding to AA 216–226 of rat/mouse GAP-43. | Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO (NB300-143) | 1:1,000 | A band at 47 kDa is detected in Western blots of brain (manufacturer’s technical information). Staining with GAP-43 was consistent with the staining pattern previously described, staining the lower part of the OE (Iwema and Schwob, 2003; Rodriguez-Gil and Greer, 2008). |

| Goat polyclonal anti-olfactory marker protein (OMP) | Purified natural Rat OMP | Wako, Dallas, TX (#544-10001) | 1:2,000 | This antibody recognized a single band at 19 kDa on a Western blot of mouse brain. Preabsorption blocks all staining (Baker et al., 1989; Koo et al., 2004). |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-brain lipid binding protein | Recombinant human full length BLBP protein | Millipore, Billerica, MA (AB9558) | 1:2,000 | A single band at 14.5 kDa on a Western blot of mouse cerebellum and cortex (Feng et al., 1994). |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-peripherin | Electrophoretically pure trp-E-peripherin fusion protein containing all but the four N-terminal amino acids of rat peripherin | Millipore, Billerica, MA (AB1530) | 1:2,000 | This antibody recognizes a single band at 57 kDa on a Western blot from PC12 lysates (manufacturer’s technical information) |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin III, clone SDL.3D10 | Synthetic peptide corresponding to the C-terminal sequence of human b-tubulin isotype III coupled to BSA. The exact sequence is: C-E S E S Q G P K. | Sigma, St. Louis, MO (T8660) | 1:250 | A single 46 kDa band was detected on a Western blot from bovine brain; no cross-reactivity with other tubulin isotopes (manufacturer’s technical information; Banerjee et al., 1990). |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) | Synthetic peptide corresponding to residues pyroE(22) H W S Y G L R P G- NH2 (32) of mouse GnRH | Affinity BioReagents (now Thermo Scientific Pierce Antibodies, Rockford, IL) (PA1-121) | 1:1,000 | Western blot from mouse brain has an expected band at 10.4 kDa. Staining with GnRH produced the expected pattern of staining in the developing embryos (Leupen et al., 2003; Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Wray et al., 1989) |

| Goat polyclonal anti-Delta/Notch-like EGF-related Receptor (DNER) | Purified, NSO-derived, recombinant mouse DNER extracellular domain; AA 26–640. | R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN (AF2254) | 1:200 | Western blot from rat brain shows a 78 kDa band (manufacturer’s technical information). Staining pattern showed labeling of developing neurons (confirmed with double staining using established neuronal markers. Cells were adjacent to glial cells consistent with the expected role for this molecule in glial cell differentiation (Eiraku et al., 2005). |

| Goat polyclonal anti-LIM homeobox do- main 2 (Lhx2) | Peptide mapping at the C-terminus of Lhx2 of human origin. Specific sequence: VTSVLTSVPGNLEGHEPHSP | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA (SC-19344) | 1:1,000 | The staining pattern seen was consistent with the expected, published staining pattern in the OE and MM cells, previously described as pioneer neurons (Ikeda et al., 2007). Western blots of mouse brain have an apparent band at 43 kDa. |

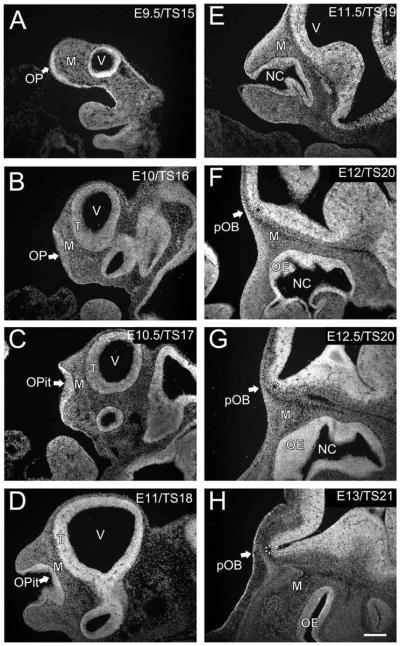

Figure 1.

Development of the olfactory placode (OP) and olfactory bulb (OB). The distribution of cells is shown with the nuclear marker DRAQ5. A: E9.5/TS15; OP (arrow). B: E10/TS16; olfactory pit (arrow). C: E10.5/TS17; olfactory pit (arrow). D: E11/TS18; olfactory pit (arrow). E: E11.5/TS19. F: E12/TS20; presumptive olfactory bulb (arrow, asterisk). G: E12.5/TS20; presumptive olfactory bulb (arrow, asterisk). H: E13/TS21; presumptive olfactory bulb (arrow, asterisk). OPit, olfactory pit; pVNO, presumptive vomeronasal organ; M, mesenchyme; pOB, presumptive olfactory bulb; NC, nasal cavity; T, telencephalon. Scale bar = 200 μm in H (applies to all).

All procedures undertaken in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University and conformed to National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

Immunolocalization and confocal microscopy

The 20-μm cryostat sections were immunostained with antibodies as described below (Table 1; n = minimum of 3 for each condition). Briefly, tissue was thawed, warmed on a hotplate at 55°C for 10 minutes, and preincubated with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) in PBS-T (PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, Sigma) for 30 minutes to block nonspecific binding sites. Tissue was incubated overnight at room temperature (RT) with a cocktail of two or three of the primary antibodies, diluted in the blocking solution. Sections were then washed 3 times in PBS-T for 5 minutes and incubated in secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluors or cyanide-dyes diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at RT (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, or Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA; Table 2). Sections were washed (as above), rinsed in PBS, mounted in Gel/Mount mounting medium (Biomeda, Foster City, CA), and coverslipped. To verify the specificity of the antibodies, dilution series were performed and tissue sections were processed in the absence of the primary antibody (data not shown). In all cases the specificity of the staining was consistent with prior reports in the literature.

TABLE 2.

Secondary Antibodies

| Secondary antibodies | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Dk α Rb 555/488 | Molecular Probes | 1:1,000 |

| Dk α MsIgG 555 | Molecular Probes | 1:1,000 |

| Dk α Gt 488/555 | Molecular Probes | 1:1,000 |

| Dk α Rt Cy3 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1:200 |

| Dk α Ch Cy3 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1:200 |

| Dk α Gt 647 | Molecular Probes | 1:1,000 |

| DRAQ5 | Alexis Biochemicals | 1:1,000 |

| DAPI | Molecular Probes | 1:1,000 |

Primary antibodies and concentrations

Complete information on the immunogens, specificity, and dilution of all primary antibodies are in Table 1. Goat anti-DCX was used to identify migrating neurons (Komitova et al., 2009); it recognizes a single band at 40 kDa on a Western blot of the olfactory bulb (Brown et al., 2003). Immunostaining with DCX stained a population of immature neurons with a migratory morphology, which is expected based on colocalization with BrdU and Ki67 (Brown et al., 2003) in the published results and is consistent with the pattern of labeled cells in the DCX-GFP transgenic mouse, also used in this study and described above.

Rabbit anti-growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43), which recognizes a band at 47 kDa on Western blots of brain (manufacturer’s technical data), was used to identify immature neurons and axons. The GAP-43 antibody stained a population of cells in the developing olfactory epithelium and mesenchyme, as previously described (Pellier et al., 1994) The staining pattern obtained with the antibody to GAP-43 corresponded to in situ localization of GAP-43 mRNA (Marcucci et al., 2009).

Goat anti-olfactory marker protein (OMP) was used to identify OSN axons. The antibody recognizes a single band at 19 kDa on a Western blot of brain; preabsorption blocks all staining (Baker et al., 1989). Immunostaining for OMP showed the pattern previously described, staining OSNs located in the upper part of the olfactory epithelium and a population of cells in mesenchyme, and also corresponded to the in situ localization of OMP mRNA (Valverde et al., 1993; Conzelmann et al., 2002; Marcucci et al., 2009).

Rabbit anti-brain lipid binding protein (BLBP), which recognizes a single band of 14.5 kDa on Western blots of cerebellum and cortex, was used to identify olfactory ensheathing cells (Feng et al., 1994). Immunostaining with BLBP stained a population of cells with morphological characteristics and a spatiotemporal distribution consistent with that of olfactory ensheathing cells; BLBP was previously shown to label ensheathing cells during development (Murdoch and Roskams, 2007; Rodriguez-Gil and Greer, 2008).

Rabbit anti-peripherin was used to identify OSN axons. The antibody recognizes a single band at 57 kDa on Western blots of PC12 lysates (manufacturer’s technical information). Immunostaining with peripherin showed strong labeling of the developing olfactory and vomeronasal nerves as previously described (Akins and Greer, 2006; Toba et al., 2008).

Mouse anti-β-tubulin III was used to identify immature neurons. The antibody detects a single band at 46 kDa on Western blots of bovine brain (manufacturer’s technical information) (Banerjee et al., 1990). Immunostaining with anti-β-tubulin III showed staining in the developing olfactory placode and mesenchyme. The cells labeled with anti-β-tubulin III double label for other markers specific to neuronal cells (Freed et al., 2008).

Rabbit anti-gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) was used to identify cells migrating from the presumptive vomeronasal organ to central targets. Staining for GnRH produced the expected pattern in the developing embryos; chains of migratory neurons were labeled emerging from the developing vomeronasal organ (Wray et al., 1989; Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Leupen et al., 2003). The antibody on Western blots detects the expected band at 10.4 kDa (manufacturer’s technical data). In situ analyses of GnRH mRNA labels neurons that are migrating from the immature vomeronasal organ in a pattern complementary to that seen with immunostaining (Schwarting et al., 2006).

Goat anti-Delta/Notch-like EGF-related Receptor (DNER) was used to identify neurons within the MM. The antibody labels a band of 78 kDa on Western blots of rat brain (manufacturer’s technical information). The staining pattern has not been previously described in the olfactory system, but was consistent with the expected pattern based on the published literature. Neuronal cells were labeled that were in direct contact with ensheathing cells during development. This is consistent with the established role of DNER as a critical molecule for the differentiation of glial cells in the developing cerebellum (Eiraku et al., 2005).

Goat anti-LIM homeobox domain 2 (Lhx2), with an apparent band at 43 kDa on Western blots of brain (manufacturer’s technical data), was used to identify neurons within the MM. The expression pattern is consistent with the abundant expression of Lhx2 mRNA shown by in situ analyses, in both the immature neurons in the olfactory epithelium, and with the failure of the olfactory bulb to form in Lhx2 knockout mice (Hirota and Mombaerts, 2004). The staining pattern seen with this antibody was consistent with prior reports in which the MM cells were described as pioneer neurons (Ikeda et al., 2007).

Electron microscopy

Embryos were obtained as described above and then immersion-fixed in 4% PFA and 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for a minimum of 24 hours at 4°C. Sections containing the developing OE, mesenchyme, and presumptive olfactory bulb were dissected and processed for electron microscopy as previously described (Montague and Greer, 1999; Treloar et al., 2002). Briefly, sections were postfixed with osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through graded alcohols, and polymerized in EPON between glass slides and coverslips previously coated with Liquid Release Agent (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA). Smaller regions containing the area of interest within the mesenchyme were micro-dissected from the EPON films and reembedded on blank EPON blocks for thin sectioning and conventional electron microcopy. Thin sections (0.07 μm) were examined with a JEOL 1200 electron microscope and photographed at primary magnifications of 4,000–25,000×. Electron micrograph negatives were digitized on a flat-bed scanner at 1200 dpi. The OE was identified based on the polarity of apically directed dendritic processes that included nascent cilia. The basal lamina was identified by the change in the orientation of cells from radial to horizontal relative to the luminal surface of the OE.

Image acquisition, analysis, and preparation

Images were acquired with a Leica confocal microscope TCS SL (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) using 20×, 40×, or 63× objectives, the latter two oil-immersion. Digital images were collected from a single optical plane, ≈0.5 μm thick. Using Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), levels were adjusted when necessary to determine if colocalization of antibodies occurred, but the composition of the images was not altered in any way. Plates were constructed using Corel Draw 10.0 for the Macintosh (Corel, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analyses were performed on timed-pregnant DCX-GFP embryos at E12 and E13. Single plane confocal images from the middle of a z-stack (1 image/section), ≈1.00 μm thick, were used to assess the density of cells within the migratory mass. Comparable to our prior procedures (Whitman et al., 2009), freeform regions were drawn surrounding the migratory mass on sagittal images from DCX-GFP-labeled sections and the area (μm2) was measured using the Measure and Label function in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). All nuclei that were double-labeled with Lhx2 and DCX-GFP were counted manually. Counts were corrected using the Abercrombie correction factor (T/(T+h)), where T is the thickness of the optical section (1.00 μm), and h is the height (z-dimension) of the Lhx2/DCX-GFP double-labeled nuclei (8.41 μm). Cell density is expressed per 100 μm2.

RESULTS

Macroscopic development of the olfactory system

The OE and OB emerge independently and do not appear to exert reciprocal influences until after the OSN axons reach the pOB (Treloar et al., 1999; Matsutani and Yamamoto, 2000; Lopez-Mascaraque et al., 2005). The OE arises from the olfactory placode, a specialized epithelial thickening, in the rostrolateral aspect of the head. The placode is seen at E9.5/TS15 (Fig. 1A, arrow), with mesenchyme separating it from the telencephalon. By E10/TS16 an increase in thickness and slight concavity in the placode is evident (Fig. 1B, arrow), along with an increase in the size of the telencephalon. By E10.5/TS17 the placode has invaginated to form the olfactory pit (Fig. 1C, arrow) with distinct marginal lips, as described by Theiler (1989). The pit enlarges and thickens through E11/TS18 (Fig. 1D, arrow) and the bordering rims narrow as the external nares form. At E11/TS18 the first evidence of an invagination of the medial wall, forming the presumptive vomeronasal organ (pVNO), is apparent. The olfactory pit continues to deepen at E11.5/TS19 and the nostrils close in further, leaving a narrow entrance to the nasal cavity (Fig. 1E). At E11.5/TS19 the invaginated pVNO is clearly distinct. By E12/TS20 (Fig. 1F) the transition from olfactory pit to nasal cavity appears complete, although epithelial development within the cavity continues as the turbinates increase in complexity and the surface area of the epithelium increases.

From E9.5/TS15 to E11.5/TS19 there is little evidence to suggest the differentiation of the olfactory bulb from the telencephalon. By E12/TS20, however, a flexure begins to form in the rostral-ventral telencephalon that will become the presumptive bulb (Fig. 1F, arrow, asterisk). Delineation of the bulb flexure is clearer in older TS20 embryos (≈E12.5; Fig. 1G, arrow, asterisk). Theiler (1989) designated E12 as a single developmental stage. However, the data we present here indicates that the bulb is undergoing significant growth and differentiation during this 24-hour period and perhaps warrants two TS stages at E12 and E12.5. By E13/TS21 the bulb has acquired its characteristic evaginated appearance, protruding rostrally from the telencephalon (Fig. 1H, arrow, asterisk). Thus, by E13/TS21, while the development of the olfactory system is not complete, the two most prominent components, the epithelium and the bulb, are easily recognized.

Migratory mass

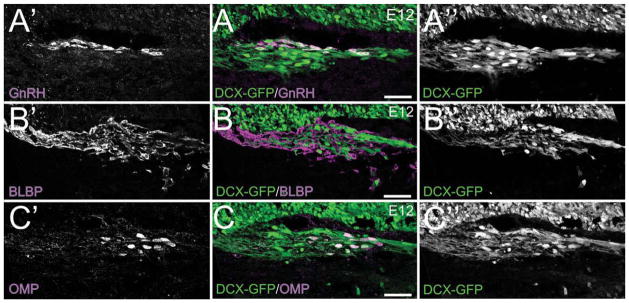

Valverde (1992) described a mass of cells and axons within the mesenchyme, intermediate between the developing OE and OB and termed it the migratory mass (MM). In ensuing years three primary populations of cells have been described within the MM: 1) GnRH+ cells; 2) olfactory ensheathing glia; and 3) olfactory marker protein+ cells. These cells have unique temporal patterns of appearance and, as shown in Figure 2, distinct distributions within the MM. Of particular importance, they account for only a fraction of the migratory cells that make up the MM. In DCX-GFP mice, in which migratory neurons are GFP+, it is evident that GnRH, OMP, and OECs account for only a small proportion of the cells within the MM (Fig. 2) (Gleeson et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2003; Whitman and Greer, 2007).

Figure 2.

The MM cells are distinct from the GnRH+ cells, the OECs, and the OMP+ cells that emerge from the OE/pVNO at E12. Sagittal sections of DCX-GFP embryos. A: E12 DCX-GFP section stained for GnRH (purple). A′: GnRH. A″: DCX-GFP. B: E12 DCX-GFP section stained for BLBP (purple). B′: BLBP. B″: DCX-GFP. C: E12 DCX-GFP section stained for OMP (purple). C′: OMP. C″: DCX-GFP. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Neuronal cell population is present in the mesenchyme beginning at E10–10.5

The first evidence for neuronal differentiation in the placode is found at E9.5 with the expression of β-tubulin III, a marker of immature neurons (Supporting Fig. 1). However, at E9.5 there is as yet no evidence of neurite extension from OSNs; axons are not found crossing the basal lamina or in the mesenchyme. Twelve to 24 hours later, at E10–10.5, there is an increase in β-tubulin III+ OSNs in the placode; they have an elongated cell body oriented radially within the developing placode and express DNER, a neuronal specific transmembrane protein (Eiraku et al., 2005) (Fig. 3A, A′, open arrow). Some OSNs extend an apical dendrite towards the lumen, and a few extend short immature cilia into the lumen of the cavity (Fig. 3A, A′).

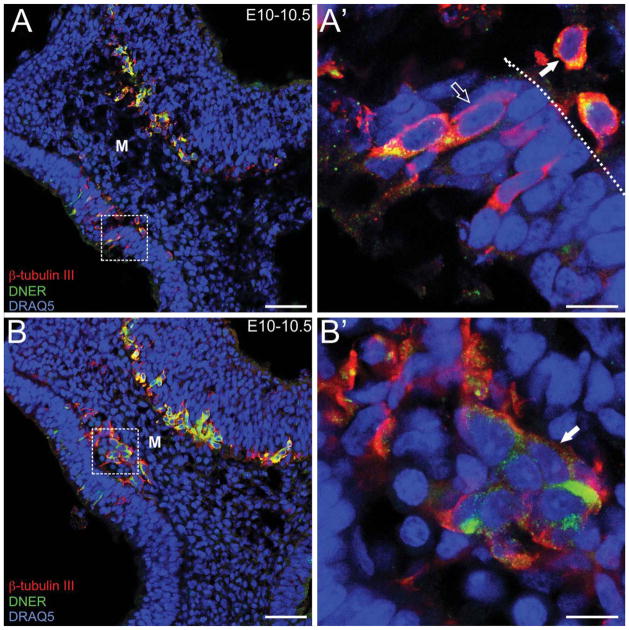

Figure 3.

MM cells are present in the mesenchyme beginning at E10–10.5 and express diverse neuronal markers. DNER (green)/β-tubulin III (red)/DRAQ5 (blue). A: E10–10.5 sagittal section. Low-magnification image of the olfactory placode. A′: High-magnification image of the boxed area in A. MM cells (solid arrow) and OSNs (open arrow). Dotted line indicates basal lamina. B: E10–10.5 sagittal section. Low-magnification image showing a cluster of MM cells in the mesenchyme. B′: High-magnification image of the boxed area in B (filled arrow indicates cluster). Abbreviations as in Fig. 1. Scale bars = 50 μm in A, B; 10 μm in A′, B′.

As noted above, the most frequently described neurons found in the mesenchyme are the GnRH+ and OMP+ cells, which are present beginning at E11.5 and E12, respectively (Fig. 2) (Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989; Wray et al., 1989; Valverde et al., 1993; Baker and Farbman, 1993; Conzelmann et al., 2002). Predating the emergence of these populations, at E10–E10.5, DNER+ neurons, which appear to have emerged from the placode and crossed the basal lamina, are seen in the mesenchyme, where they coalesce as part of the MM (Fig. 3B, B′, closed arrow). They are generally spherical, but more irregular in shape than OSNs, perpendicular to pseudo-stratified placode, and deep to the basal lamina (Fig. 3A, A′; closed arrow). Within the mesenchyme they cluster, and coalesce into focal masses along the nascent olfactory nerve pathway (Fig. 3B, B′; arrow). The density of cells within the olfactory nerve appears to increase between E10.5 and E11 (cf. Fig. 6 for quantitative analysis at later ages), and the cells become more organized as they coalesce into a distinct mass and align with the trajectory of the OSN axons (cf. Fig. 5). Coexpression of DNER and DCX was shown with double-label immunohistochemistry (Supporting Fig. 2) confirming the migratory phenotype of the DNER+ neurons in the MM.

Figure 6.

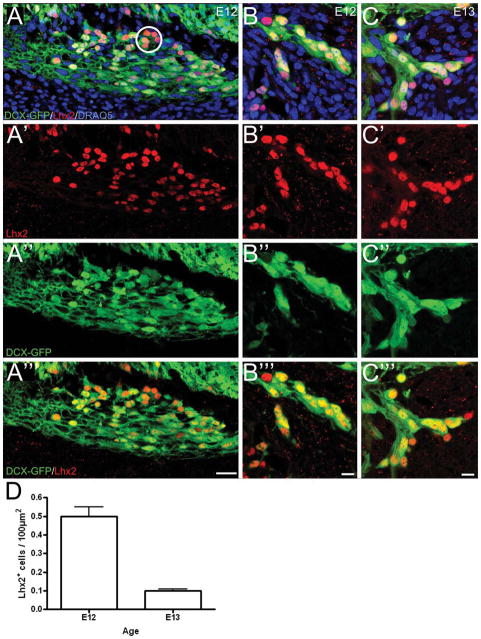

The mean ± SEM density of DCX+/Lhx2+ cells decreases between E12 and E13. DCX-GFP sections stained with Lhx2 (red)/DRAQ5 (blue). Sagittal sections. A–C: The expression level of both Lhx2 and DCX-GFP is variable. Cells with similar expression levels cluster (i.e., dorsal aspect of MM in A; circle). A few isolated MM cells express Lhx2 but not DCX-GFP. A′–C′: Lhx2 staining. A″–C″: DCX–GFP labeling. A‴-C‴: DCX-GFP sections stained with Lhx2 without the nuclear marker to demonstrate the colocalization. D: Cell counts of Lhx2+/DCX+ cells at E12 and E13. Scale bars = 25 μm in A–A‴, B–B‴; 10 μm in C–C‴.

Figure 5.

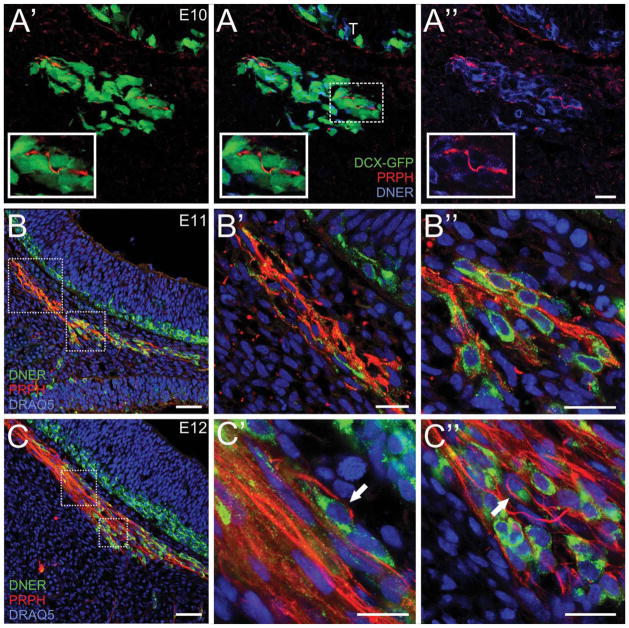

Composition of the migratory mass. DCX-GFP sections stained with peripherin (red)/DNER (blue). E10 sagittal section. A: DCX-GFP/PRPH/DNER. Inset shows a single PRPH+ axon fascicle within the MM. A′: DCX-GFP/PRPH. A″: PRPH/DNER. B, B′, B″, C, C′, C″: Sagittal CD1 sections stained with DNER (green)/peripherin (red)/DRAQ5 (blue). (B) Low-magnification image of the MM at E11. (B′) High-magnification of the upper box shown in B. (B″) High-magnification of the lower box shown in B. (C) Low-magnification image of the MM at E12. (C′) High-magnification of the upper box shown in C. (C″) High-magnification of the lower box shown in C. The axons are seen directly apposed and wrapping the MM cells (filled arrows). Scale bars = 20 μm in A, A′, A″, B′, B″, C′, C″; 50 μm in B, C.

MM cells are a migratory population emerging from the olfactory placode

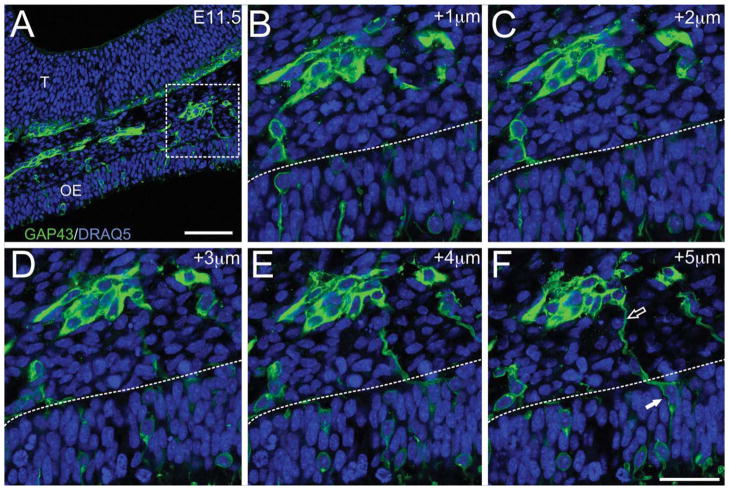

MM cells differentiate within the placode beginning at E10–10.5, when they first migrate across the basal lamina and into the mesenchyme (cf. Fig. 3). MM cells can also be identified with GAP43, a marker of immature neurons, as they differentiate within the epithelium and move toward the basal lamina (Fig. 4). They extend a leading process across the basal lamina where it appears to contact the trailing process of another MM cell (Fig. 4F, open arrow), forming chains of MM cells which exit the developing OE to join the MM in the mesenchyme (Fig. 4A–F; closed arrow in 4F). Like most migratory neurons, the MM cells have both leading and trailing processes (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

MM cells emerge from the olfactory pit. GAP43 (green)/DRAQ5 (blue). E11.5 sagittal section. A: Low-magnification image of MM cells exiting the presumptive OE. B–F: Z-series of a high-magnification image of the boxed area from A, taken at 1-μm intervals. Dotted lines indicate position of the basal lamina. The MM cells within the olfactory pit (F; filled arrowhead) extend a leading process that contacts the cells already in the mesenchyme (F; open arrowhead). Abbreviations as in Fig. 1. Scale bars = 50μm in A; 20μm in F (applies to B–F).

Changing composition of the MM

To determine whether OSN axons or MM cells cross the basal lamina first, we stained the MM cells with DNER and the OSN axons with peripherin, an intermediate filament marker that selectively labels axons (Akins and Greer, 2006). We also used DCX-GFP to confirm the molecular phenotype of the MM cells. At E10 there is a paucity of OSN axons (red) within the MM. Isolated axons were seen (Fig. 5A, A′, A″; insets), but axon fascicles are not yet found within the mesenchyme (cf. Fig. 7). At E10 the density of cells in the MM, in comparison to OSN axons, is notably greater.

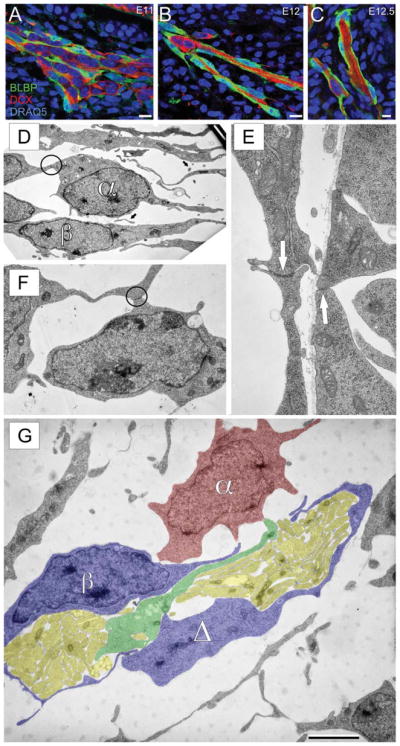

Figure 7.

MM cells, ensheathing cells, and OSN axons travel in clusters through the mesenchyme. Sagittal sections stained for DCX (red)/BLBP (green)/DRAQ5 (blue). A–C: Composition of the MM at E11, 12, and 12.5. Note the clustering of OSN axons, MM cells, and OECs in the mesenchyme at E12 and E12.5, respectively. D–G: Electron microscopy of the developing olfactory nerve pathway. D: Section through the mesenchyme of an E10 mouse. Two distinct cell morphologies are apparent (α and β). A few examples of likely axons (arrows) are seen, but no evidence of fasciculation. E, F: Examples of adherens junctions (E, arrows; F, circle) between adjacent cells within the mesenchyme at E10; see also circle in (D). G: Section through the mesenchyme of an E12 mouse. Fascicles of coalesced axons (yellow) are seen surrounded by the α (red) and β (blue) cells as well as an unidentified process (Δ, blue). A process (green) that appears to be an axon with an enlarged terminal at one end is seen interposed between the two clusters of axons. Scale bars = 10 μm in A–C; 5 μm in G (for D); 1.25 μm in G (for E); 2.5 μm in G (for F).

However, by E11 there is an increase in the density of fasciculated axons, although cells persist and continue to be a primary component of the MM (Supporting Fig. 3A, A′, A″). A transition is apparent by E12, when the axons begin to innervate the pOB (Supporting Fig. 3B, B′, B″). By E13 the MM has transitioned to the nascent olfactory nerve; there are only a few cells within the MM that express neuronal markers, and the region is now largely composed of axon fascicles surrounded by OECs (Supporting Fig. 3C, C′, C″).

To quantify the changes in the MM we used Lhx2, an LIM-homeodomain protein expressed by OSN progenitors and MM cells (Rincon-Limas et al., 1999; Cau et al., 2002; Hirota and Mombaerts, 2004; Kolterud et al., 2004). At E12 and E13, Lhx2 and DCX-GFP colocalize in the MM, although a subpopulation of Lhx2+ cells do not express DCX-GFP+ (Fig. 6A–C, A‴–C‴). To quantify the density of cells within the MM, we counted Lhx2/DCX-GFP+ cells in single digital optical planes of the MM. Between E12 and E13, 24 hours, the density of MM cells decreased by 80%, consistent with our working hypothesis that they are a transient population within the mesenchyme (Fig. 6D).

Topography of cells within the migratory mass

As early as E11 cells cluster caudally within the MM. OSN axons are found throughout, but appear to coalesce rostrally within the mass (Fig. 5B, B′, B″, C, C′, C″; Supporting Fig. 3). In the caudal MM the axons are juxtaposed to the cells, providing the opportunity for cell:axon interactions (Fig. 5B″, C″, arrows). The transition between the caudal area, where the MM cells are present, and the rostral area, where the OSN axons converge, is distinctive, suggesting that the migration of MM cells may be spatially restricted.

Olfactory ensheathing cells surround axon clusters and MM cells

OECs surround the OSN axons and were previously suggested to be the primary cellular components of the MM (Doucette, 1989). Thus, we asked when OECs are first detected in the MM. We labeled OECs with an antibody against brain-lipid binding protein (BLBP), a radial glial marker that labels OECs during early development (Carson et al., 2006). OECs, labeled with BLBP (green), are first seen at E11 juxtaposed to and surrounding MM cells (DCX+; red) and the few OSN axons present (Fig. 7A). As the OSN axons travel across the basal lamina and traverse the mesenchyme, they, and the MM cells, are wrapped by OEC processes (Fig. 7B, C). The proximity of the BLBP+ OECs, the MM cells, and the OSN axon fascicles is consistent with the notion that they are cooperatively organized.

To test our conclusions at an ultrastructural level we performed electron microscopy using E10 and E12 embryos (Fig. 7). At E10 we did not find axon fascicles in the mesenchyme or crossing the basal lamina. We cannot exclude the possibility that some axon fascicles might be found outside of the areas we sampled, although it seems unlikely. However, a few transversely cut single axons were seen within the mesenchyme at E10, which was consistent with our confocal analyses in which we encountered rare isolated axons (Fig. 7D, arrows; cf. Fig. 5). Despite the paucity of axons, cells were widespread within the mesenchyme (Fig. 7D, F) and fell into two basic morphological phenotypes: cells with a spherical cell body, large nucleus, and small amount of cytoplasm, and narrow cells with an elongated nucleus (Fig. 7D, α,β). Of further interest, the α cells formed close appositions with puncta adherens (Fig. 7D, F, circles; 7E, arrows), consistent with the formation of the chains of MM cells seen with confocal analyses.

By E12, many OSN axons are crossing the basal lamina and joining fascicles (yellow) within the mesenchyme (Fig. 7G). The axon fascicles are surrounded by morphologically heterogeneous cells, some of which had an irregular nuclear membrane, typical of a migratory phenotype (Fig. 7G, α, red). Others have an elongated appearance more consistent with OECs (Fig. 7G, β, blue). It was common to encounter processes, closely apposed to or wrapping the axon fascicle, that did not include a nucleus and thus may be an extended process (Fig. 7G, Δ, blue). This was reminiscent of the clusters of OSN axons, OECs, and MM cells seen with confocal microscopy at E12 (Fig. 7). In some cases, longitudinally cut axons appeared to extend an enlarged leading process (Fig. 7G, green).

While the molecular phenotype of the cells ultrastructurally identified at both E10 and E12 remains to be determined, their overall morphological similarity to the cells we are describing here at the level of the confocal microscope suggests that they correspond to the MM neurons and OECs. The paucity of axons relative to MM cells at E10 with the ensuing shift in ratios by E12 is consistent with our hypothesis that MM cells are precocious in migrating into the mesenchyme, accompanied perhaps by only a few OSN axons. Later, the synchronous emergence of larger numbers of axons leads to the formation of fascicles that interdigitate among the earlier arrived MM cells.

DISCUSSION

Here we: 1) identify subpopulations of neuronal cells emerging from the placode and developing OE; 2) develop a timeline of OSN axon extension relative to cellular migration from the placode; and 3) demonstrate that at least one neuronal population emerges from the placode into the frontal mesenchyme precociously, prior to the outgrowth of sufficient numbers of OSN axons to form fascicles. Based on these data we propose a model in which the MM cells in mice may act as “guidepost” cells and establish a scaffold or framework that contributes to the initial formation of the olfactory nerve and its approach to the nascent OB.

Neurons are present within the mesenchyme beginning at E10

As early as E9.5 the expression of β-tubulin III provides evidence of neuronal differentiation within the placode. However, at E9.5 there is no evidence of OSN axon extension or migration of cells into the frontal mesenchyme. By E10–10.5 the density of neurons in the placode has increased, and there are migratory cells clustering within the mesenchyme. Neurons within both the placode and the mesenchyme express DNER and β-tubulin III, but at E10–10.5 differences in morphology suggest the presence of two distinct populations.

Changing composition of the MM

In the adult mouse the olfactory nerve is composed exclusively of OSN axon bundles surrounded by ensheathing cells, which promote axon outgrowth and extension (Kafitz and Greer, 1999; Au et al., 2002). However, we show here that the composition of the developing embryonic olfactory nerve is starkly different from that of the adult. The transition from “nascent” olfactory nerve to “adult-like” occurs rapidly. At E10–E10.5 the olfactory nerve pathway appears to be primarily composed of MM cells, but 72 hours later, at E13, it contains predominately OSN axons and OECs.

Neuronal populations emerging from the nascent OE

Several groups have described neuronal populations migrating from the developing OE into the mesenchyme. Among these, the OECs, OMP+ cells, and GnRH+ cells have received the most recognition, while others have garnered scant attention. For example, in the E12 rat a population of acetylcholinesterase+ and β-tubulin III+ cells emerges from the placode and spreads over the dorsal surface of the telencephalon (De Carlos et al., 1995). Other populations emerge from the placode as early as E10 and express a variety of neuronal markers including NCAM (Schwanzel-Fukuda et al., 1992), GAP43 (Pellier et al., 1994), Dlx5 (Merlo et al., 2007), Six1 (Ikeda et al., 2007), and VGlut2 (Honma et al., 2004). While the emergence of neuronal populations from the placode is established, the molecular and functional identity of these cells, and their influence on the formation of the olfactory system and/or the central nervous system (CNS), has remained controversial.

Here we demonstrate that beginning at E10.0–10.5 there is a neuronal population of cells in the mesenchyme (MM cells) expressing several markers including DCX, β-tubulin III, and DNER. By E12, our data clearly indicates that this is a heterogeneous population of cells, expressing various combinations of DCX, OMP, DNER, GnRH, and Lhx2. The diversity that exists among these MM cells may be related to the heterogeneity of the OSN axons, each of which expresses only 1 of ≈1,200 ORs. It is plausible to speculate that the subpopulations of OSN axons rely on specific subsets of the neurons within the mesenchyme (MM cells) as they travel toward the pOB. In this scenario MM cells could act as “guidepost cells” for the OSN axons, an idea previously suggested solely for the later arriving OMP+ cells (Valverde et al., 1993; Conzelmann et al., 2002).

Bate (1976) showed that the neural pathways of the grasshopper antenna and leg are established by pioneer axons that rely on the presence of intermediate cells to direct their trajectory toward their target, the general tenet of guidepost cells. Guidepost cells have the following features: 1) located along the path of growing axons; 2) contacted directly by advancing growth cones; and 3) within filopodial reach of each other (Palka et al., 1992). Furthermore, guidepost cells are discrete and do not form a continuous pathway. They act as intermediate rather than final targets for the axons, providing cues regulating axon guidance. The data presented here are consistent with the notion that cells within the mesenchyme, components of the MM, conform to these criteria and therefore seem likely to be guidepost cells contributing to the formation of the olfactory nerve. An alternative for testing this hypothesis is with a selective deletion of cells contributing to the MM using, for example, a conditional knockout of DCX in olfactory placode derived cells.

Here we demonstrate for the first time the molecular diversity of the MM cells emerging from the placode prior to or synchronous with the outgrowth of OSN axons, which are first be seen at E10–E10.5. However, at this early age the axons have not yet formed dense fascicles. Fasciculation is not evident until E11; by E11.5 the OSN axons have contacted the basal lamina of the telencephalon (cf. Supporting Fig. 3). While Cuschieri and Bannister (1975) initially reported that the axons contact the telencephalon at E10.5, the 24-hour difference may be attributable to differences in staging embryonic mouse development, the strain of mice, or environmental effects. The MM cells are present prior to the initial fasciculation of OSN axons, and disappear from the mesenchyme after the axons reach the telencephalon and pOB. The earliest arriving OSN axons traverse ≈200 μm through the mesenchyme to reach the pOB. Along this path there are ≈1,200 subpopulations of axons that begin to sort and coalesce as they form the olfactory nerve layer and begin targeting glomeruli. It is plausible that the MM cells provide intermediate cellular cues that influence the organization and trajectory of the OSN axons.

CONCLUSIONS

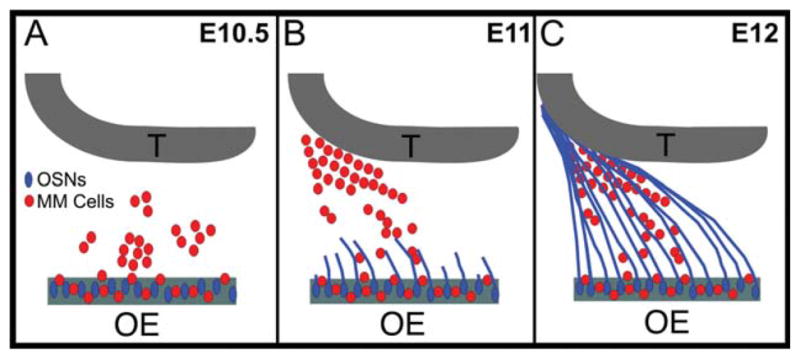

In light of these data, we propose a model for the development of the olfactory nerve pathway (Fig. 8). We suggest that a population of neuronal “guidepost” cells emerge from the OP beginning at E10–E10.5. These cells coalesce to form a focal mass within the mesenchyme by E11 and are joined by a few OECs and scattered isolated axons. As the MM cells gather caudally within the developing pathway, they interdigitate with both OECs and axons, both of which continue to travel rostrally toward the interface with the basal telencephalon. The cellular diversity within the MM suggests that subsets of MM cells may be associated with specific subsets of axons, perhaps influencing axon sorting and targeting within the mesenchyme as early as E10.5. By E13, when the OSN axons and OECs have definitively contacted the basal telencephalon and the nascent OB has begun to emerge, the MM cells are no longer required since axon:axon interactions within the olfactory nerve can now serve to promote axon guidance (i.e., Bozza et al., 2009; Imai et al., 2009).

Figure 8.

MM cells act as guidepost cells as the OSN axons transverse and organize within the mesenchyme. A: At 10.5, both OSNs (blue) and MM cells (red) differentiate within the developing OE and the MM cells begin to egress into the mesenchyme. B: By E11, the OSN axons (blue) begin crossing the basal lamina and contacting the mesenchymal MM cells. While OSN axon outgrowth is occurring, the MM cells (red) coalesce into an organized mass that parallels the nascent olfactory nerve pathway. C: By E12, the OSN axons (blue) have traversed the mesenchyme, in close apposition to the MM cells (red), until the axons contact and penetrate the telencephalic vesicle.

In summary, our data show that there is significant heterogeneity in the populations of cells expressing neuronal markers that emerge from the early placode. While the fate of many of these cells remains unknown, their transient stabilization and positioning within the mesenchyme, intermediate between the OP and the nascent pOB, strongly suggests that they contribute to the establishment of the olfactory nerve pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD); Grant numbers: DC00210, DC007880; National Institue on Aging (NIA); Grant number: AG028054 (to C.A.G.); Grant sponsor: NIDCD; Grant number: DC007600 (to H.B.T.); Grant sponsor: Yale MSTP Program; Grant number: GM0720; Grant sponsor: NIDCD; Grant number: F30 DC010324 (both to A.M.M.).

The authors thank Ms. Dolores Montoya and Ms. Christine Kaliszewski for excellent technical support. We also thank the members of the Greer Laboratory for encouragement and many constructive discussions.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akins MR, Greer CA. Cytoskeletal organization of the developing mouse olfactory nerve layer. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:358–367. doi: 10.1002/cne.20814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au WW, Treloar HB, Greer CA. Sublaminar organization of the mouse olfactory bulb nerve layer. J Comp Neurol. 2002;446:68–80. doi: 10.1002/cne.10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H, Farbman AI. Olfactory afferent regulation of the dopamine phenotype in the fetal rat olfactory system. Neuroscience. 1993;52:115–134. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90187-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H, Grillo M, Margolis FL. Biochemical and immunocytochemical characterization of olfactory marker protein in the rodent central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:246–261. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Roach MC, Trcka P, Luduena RF. Increased microtubule assembly in bovine brain tubulin lacking the type III isotype of beta-tubulin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1794–1799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate CM. Pioneer neurones in an insect embryo. Nature. 1976;260:54–56. doi: 10.1038/260054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza T, Vassalli A, Fuss S, Zhang JJ, Weiland B, Pacifico R, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P. Mapping of class I and class II odorant receptors to glomerular domains by two distinct types of olfactory sensory neurons in the mouse. Neuron. 2009;61:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JP, Couillard-Despres S, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG. Transient expression of double-cortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.10874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystron I, Rakic P, Molnar Z, Blakemore C. The first neurons of the human cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:880–886. doi: 10.1038/nn1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson C, Murdoch B, Roskams AJ. Notch 2 and Notch 1/3 segregate to neuronal and glial lineages of the developing olfactory epithelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1678–1688. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Casarosa S, Guillemot F. Mash1 and Ngn1 control distinct steps of determination and differentiation in the olfactory sensory neuron lineage. Development. 2002;129:1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuah MI, Au C. Cultures of ensheathing cells from neonatal rat olfactory bulbs. Brain Res. 1993;601:213–220. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91713-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conzelmann S, Levai O, Breer H, Strotmann J. Extraepithelial cells expressing distinct olfactory receptors are associated with axons of sensory cells with the same receptor type. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri A, Bannister LH. The development of the olfactory mucosa in the mouse: light microscopy. J Anat. 1975;119(Pt 2):277–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlos JA, Lopez-Mascaraque L, Valverde F. The telencephalic vesicles are innervated by olfactory placode-derived cells: a possible mechanism to induce neocortical development. Neuroscience. 1995;68:1167–1178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00199-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette R. Development of the nerve fiber layer in the olfactory bulb of mouse embryos. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:514–527. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraku M, Tohgo A, Ono K, Kaneko M, Fujishima K, Hirano T, Kengaku M. DNER acts as a neuron-specific Notch ligand during Bergmann glial development. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:873–880. doi: 10.1038/nn1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Hatten ME, Heintz N. Brain lipid-binding protein (BLBP): a novel signaling system in the developing mammalian CNS. Neuron. 1994;12:895–908. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro M, Geuna S, Fasolo A, Giacobini-Robecchi MG. Evidence of very early neuronal migration from the olfactory placode of the chick embryo. Neuroscience. 2001;107:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro M, Geuna S, Fasolo A, Giacobini-Robecchi MG. HuC/D confocal imaging points to olfactory migratory cells as the first cell population that expresses a post-mitotic neuronal phenotype in the chick embryo. Neuroscience. 2003;122:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed WJ, Chen J, Backman CM, Schwartz CM, Vazin T, Cai J, Spivak CE, Lupica CR, Rao MS, Zeng X. Gene expression profile of neuronal progentior cells derived from hESCs: activation of chromosome llp15.5 and comparison to human dopaminergic neurons. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds JW. Early neuron differentiation in the mouse of olfactory bulb. I. Light microscopy. J Comp Neurol. 1972;146:233–252. doi: 10.1002/cne.901460207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds JW, Hinds PL. Synapse formation in the mouse olfactory bulb. I. Quantitative studies. J Comp Neurol. 1976;169:15–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.901690103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota J, Mombaerts P. The LIM-homeodomain protein Lhx2 is required for complete development of mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8751–8755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400940101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma S, Kawano M, Hayashi S, Kawano H, Hisano S. Expression and immunohistochemical localization of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 in the migratory pathway from the rat olfactory placode. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:923–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Ookawara S, Sato S, Ando Z, Kageyama R, Kawakami K. Six1 is essential for early neurogenesis in the development of olfactory epithelium. Dev Biol. 2007;311:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Yamazaki T, Kobayakawa R, Kobayakawa K, Abe T, Suzuki M, Sakano H. Pre-target axon sorting establishes the neural map topography. Science. 2009;325:585–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1173596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafitz KW, Greer CA. Olfactory ensheathing cells promote neurite extension from embryonic olfactory receptor cells in vitro. Glia. 1999;25:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key B, Akeson RA. Olfactory neurons express a unique glycosylated form of the neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1729–1743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolterud A, Alenius M, Carlsson L, Bohm S. The Lim homeobox gene Lhx2 is required for olfactory sensory neuron identity. Development. 2004;131:5319–5326. doi: 10.1242/dev.01416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komitova M, Zhu X, Serwanski DR, Nishiyama A. NG2 cells are distinct from neurogenic cells in the post-natal mouse subventricular zone. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:702–716. doi: 10.1002/cne.21917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JH, Gill S, Pannell LK, Menco BP, Margolis JW, Margolis FL. The interaction of Bex and OMP reveals a dimer of OMP with a short half-life. J Neurochem. 2004;90:102–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovici M, Lapointe F, Aletta P, Ayer-Le Lievre C. Avian olfactory receptors: differentiation of olfactory neurons under normal and experimental conditions. Dev Biol. 1996;175:118–131. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leupen SM, Tobet SA, Crowley WF, Jr, Kaila K. Heterogeneous expression of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons of the adult mouse. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3031–3036. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Mascaraque L, Garcia C, Blanchart A, De Carlos JA. Olfactory epithelium influences the orientation of mitral cell dendrites during development. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:325–335. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci F, Zou DJ, Firestein S. Sequential onset of presynaptic molecules during olfactory sensory neuron maturation. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516:187–198. doi: 10.1002/cne.22094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M, Amieva MR. Early neurogenesis of the mouse olfactory nerve: Golgi and electron microscopic studies. J Comp Neurol. 1989;288:339–352. doi: 10.1002/cne.902880211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsutani S, Yamamoto N. Differentiation of mitral cell dendrites in the developing main olfactory bulbs of normal and naris-occluded rats. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:402–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo GR, Mantero S, Zaghetto AA, Peretto P, Paina S, Gozzo M. The role of Dlx homeogenes in early development of the olfactory pathway. J Mol Histol. 2007;38:612–623. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague AA, Greer CA. Differential distribution of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:233–246. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990308)405:2<233::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch B, Roskams AJ. Olfactory epithelium progenitors: insights from transgenic mice and in vitro biology. J Mol Histol. 2007;38:581–599. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nef S, Allaman I, Fiumelli H, De Castro E, Nef P. Olfaction in birds: differential embryonic expression of nine putative odorant receptor genes in the avian olfactory system. Mech Dev. 1996;55:65–77. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palka J, Whitlock KE, Murray MA. Guidepost cells. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2:48–54. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90161-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellier V, Astic L, Oestreicher AB, Saucier D. B-50/GAP-43 expression by the olfactory receptor cells and the neurons migrating from the olfactory placode in embryonic rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1994;80:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon-Limas DE, Lu CH, Canal I, Calleja M, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Botas J. Conservation of the expression and function of apterous orthologs in Drosophila and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2165–2170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gil DJ, Greer CA. Wnt/Frizzled family members mediate olfactory sensory neuron axon extension. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511:301–317. doi: 10.1002/cne.21834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Pfaff DW. Origin of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Nature. 1989;338:161–164. doi: 10.1038/338161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Abraham S, Crossin KL, Edelman GM, Pfaff DW. Immunocytochemical demonstration of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) along the migration route of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) neurons in mice. J Comp Neurol. 1992;321:1–18. doi: 10.1002/cne.903210102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting GA, Henion TR, Nugent JD, Caplan B, Tobet S. Stromal cell-derived facgtor-1 (chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 12) and chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 4 are required for migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons to the forebrain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6834–6840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1728-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting GA, Wierman ME, Tobet SA. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:305–312. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbacher K, Fleischer J, Breer H, Conzelmann S. Expression of olfactory receptors in the cribriform mesenchyme during prenatal development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbacher K, Fleischer J, Breer H. Odorant receptor proteins in olfactory axons and in cells of the cribriform mesenchyme may contribute to fasciculation and sorting of nerve fibers. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;323:211–219. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarozzo G, Peretto P, Fasolo A. Cell migration from the olfactory placode and the ontogeny of the neuroendocrine compartments. Zoolog Sci. 1995;12:367–383. doi: 10.2108/zsj.12.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler K. The house mouse: atlas of embryonic development. Heidelberg: Springer; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Toba Y, Tiong JD, Ma Q, Wray S. CXCR4/SDF-1 system modulates development of GnRH-1 neurons and the olfactory system. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:487–503. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar HB, Purcell AL, Greer CA. Glomerular formation in the developing rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:289–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar HB, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Greer CA. Specificity of glomerular targeting by olfactory sensory axons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2469–2477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02469.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F, Santacana M, Heredia M. Formation of an olfactory glomerulus: morphological aspects of development and organization. Neuroscience. 1992;49:255–275. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90094-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F, Heredia M, Santacana M. Characterization of neuronal cell varieties migrating from the olfactory epithelium during prenatal development in the rat. Immunocytochemical study using antibodies against olfactory marker protein (OMP) and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;71:209–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock KE, Westerfield M. A transient population of neurons pioneers the olfactory pathway in the zebrafish. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8919–8927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08919.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman MC, Greer CA. Synaptic integration of adult-generated olfactory bulb granule cells: basal axodendritic centrifugal input precedes apical dendrodendritic local circuits. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9951–9961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman MC, Fan W, Rela L, Rodriguez-Gil D, Greer CA. Blood vessels form a migratory scaffold in the rostral migratory stream. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516:94–104. doi: 10.1002/cne.22093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S, Grant P, Gainer H. Evidence that cells expressing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone mRNA in the mouse are derived from progenitor cells in the olfactory placode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:8132–8136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.