Abstract

Histone methyltransferase DOT1L is a drug target for MLL leukemia. We report an efficient synthesis of a cyclopentane-containing compound that potently and selectively inhibits DOT1L (Ki = 1.1 nM) as well as H3K79 methylation (IC50 ~ 200 nM). Importantly, this compound exhibits a high stability in plasma and liver microsomes, suggesting it is a better drug candidate.

Introduction

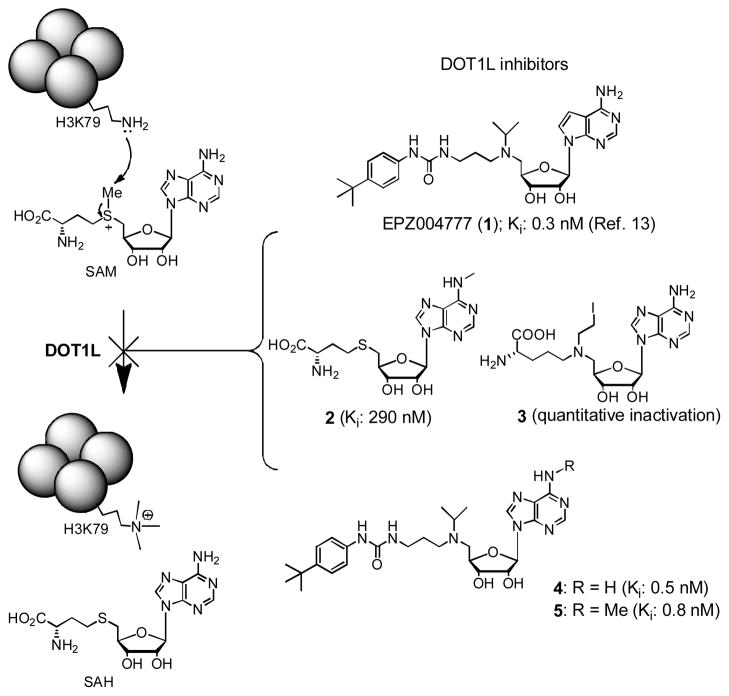

In addition to genetic changes such as DNA mutation and translocation, aberrant post-translational modifications of histone sidechains play important roles in cancer initiation and progression by dysregulating relevant gene expression.1,2 Compounds targeting histone-modifying enzymes that can correct these epigenetic errors could therefore represent novel cancer therapeutics.3,4 Histone methyltransferase (HMT) DOT1L specifically methylates the residue Lys79 of histone H3 (H3K79), using S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) as the enzyme cofactor (Figure 1).5,6 Recent biological studies have demonstrated that DOT1L is a novel drug target for acute leukemia with MLL (mixed lineage leukemia) gene translocation.7–9 This subtype of leukemia accounts for ~75% infant and ~10% adult acute leukemia with a particularly poor prognosis.10 The majority of the translocated gene products, MLL-oncoproteins, are able to recruit DOT1L, which causes H3K79 hypermethylation leading to overexpression of leukemia relevant genes and eventually the cancer. Inhibitors of DOT1L should block the process and may potentially reverse the progress of MLL leukemia.6

Figure 1.

DOT1L catalyzed reaction and inhibitors.

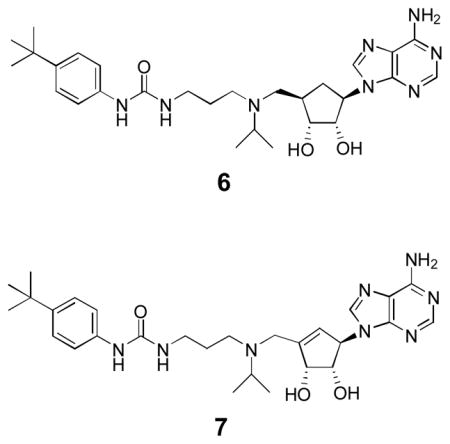

Previous medicinal chemistry studies by us11,12 and others13–15 have led to the discovery of several highly potent inhibitors of DOT1L with Ki values of <1 nM, as representatively shown in Figure 1. EPZ004777 (1) is the first disclosed DOT1L inhibitor, which can inhibit H3K79 methylation, lower down leukemia relevant gene expression, and induce differentiation of MLL leukemia cells.13 This further pharmacologically validated DOT1L to be a target for this type of leukemia. At almost the same time, we used a structure based design to find N6-substituted SAH (S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine), such as compound 2, are highly selective inhibitors of DOT1L.11 A mechanism based inhibitor design produced several aziridium analogs of SAM, such as 3 (Figure 1) which almost quantitatively inactivates DOT1L. However, these compounds with a polar and charged amino acid moiety do not have cell activity, presumably due to limited cell membrane permeability. In addition, our independent effort in finding competitive DOT1L inhibitors resulted in the identification of compounds 4 and 5 with a similar structure and activity as 1.12 Structure activity relationship (SAR) investigation showed the urea group is critically important for the high potency, with each of the two NH moieties offering ~25 - >50-fold activity enhancement. A crystallographic study revealed the binding structure of 1 in DOT1L.14 While the adenosine part of 1 adopts almost the same binding pose as that of SAM, DOT1L undergoes a large conformational change to favorably hold the tert-butylphenyl substituted urea group, with the -NHCONH-forming two hydrogen bonds with a sidechain of the enzyme.

A problem with these ribose-containing inhibitors, e.g., 1 and 4, is their metabolic instability, resulting in a short half-life in plasma.13 Compound 1 has to be infused continuously using a subcutaneously implanted osmotic pump to achieve a stable plasma drug concentration of ~0.5 μM. This might be also responsible for a relatively weak in vivo efficacy in prolonging the lifespan of the experimental animals in a mouse model of MLL translocated leukemia.13 Here, we report the synthesis, biological activity and metabolic stability of two non-ribose containing DOT1L inhibitors.

Results and Discussion

Inhibitor design and synthesis

Since adenosine or deaza-adenosine moiety can be recognized by many enzymes,16,17 leading to a rapid cleavage of adenine and/or 5′-substituent, a possible solution is to synthesize compounds 6 and 7 by replacing the metabolically labile ribose (or more accurately ribofuranose) group in 1 and 4 with a cyclopentane or cyclopentene ring.

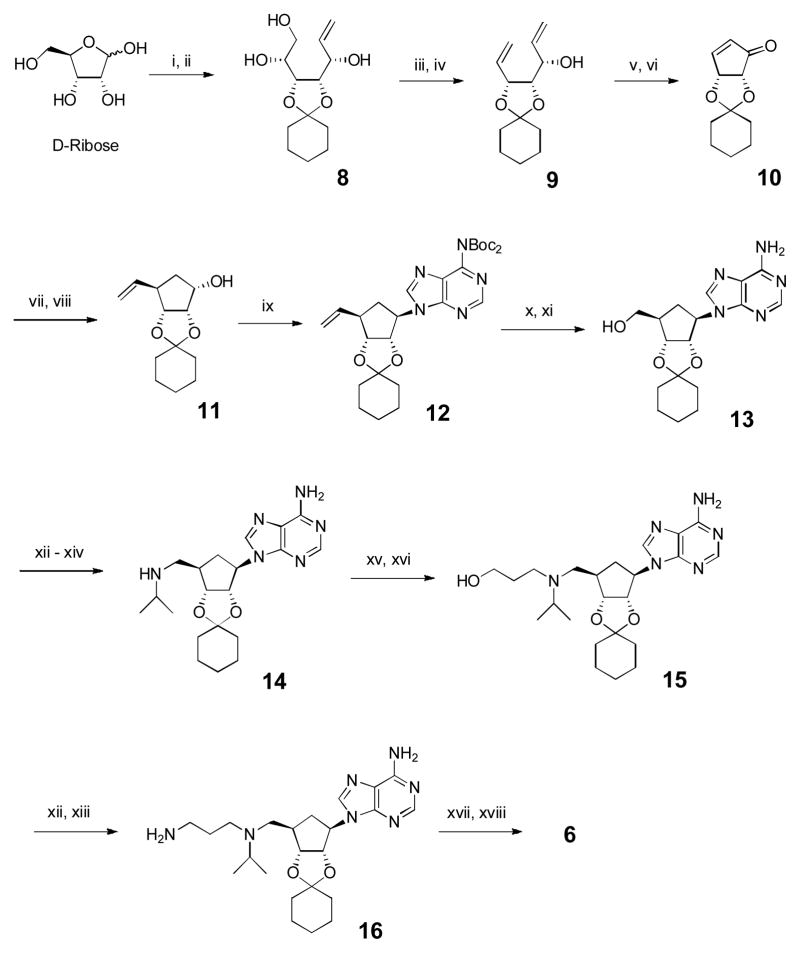

A 20-step synthesis of compound 6 is shown in Scheme 1, starting from readily available D-ribose, with the key steps being to construct the central cyclopentane ring with the correct stereochemistry of its substituents. The 2′,3′-dihydroxyls of D-ribose were selectively protected with cyclohexanone and the product was treated with vinylmagnesium bromide to give vinyl-substituted ribose derivative 8 (Supporting Information Experimental Section). Its vicinal 4′,5′-diol was oxidatively cleaved by NaIO4 and the resulting 4′-CH=O treated with CH2=PPh3 to afford diene 9, which was subjected to a ring-closing metathesis reaction, followed by oxidation using Dess-Martin periodinane (DMP) to produce cyclopentenone 10. Thanks to a high steroselectivity rendered by the bicyclic ring of 10, nucleophilic attacks preferably occur from the less hindered up side of the cyclopentane ring.18 Thus, 1,4-addition of a vinyl group to 10 and the ensuing NaBH4-mediated reduction gave exclusively the key cyclopentane intermediate 11. A Mitsunobu reaction using di-BOC (tert-butyloxycarbonyl) protected adenine with 11 afforded compound 12, which was treated with O3 at −78 °C followed by NaBH4 to give 13 with a 5′-OH (according to the corresponding ribofuranose nomenclature). Using a Mitsunobu reaction with phthalimide followed by treatment with NH2NH2, the 5′-OH of 13 was converted to an -NH2, which was then mono-substituted with an isopropyl group using acetone/NaCNBH3 to produce compound 14. Conjugated addition of 14 to methyl acrylate followed by LiAlH4 reduction gave compound 15. Its -OH was again converted to a primary -NH2, affording compound 16, which was treated with 4-tert-butylphenyl isocyanate followed by deprotection of 2′, 3′-hydroxyls to give the final product 6 with an overall yield of 19.3% from D-ribose.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis for compound 6. Reagents and conditions: (i) cyclohexanone, cat. H2SO4; (ii) CH2=CHMgBr, THF, −78 °C, 70% for 2 steps; (iii) NaIO4, MeOH/H2O; (iv) Ph3PCH3Br, t-BuOK, THF, 87% for two steps; (v) 2nd generation Grubbs’ catalyst (5 mmol%), CH2Cl2; (vi) DMP, CH2Cl2, 86% for two steps; (vii) CH2=CHMgBr, TMSCl, hexamethylphosphor-amide, CuBr·Me2S, THF, −78 °C, 89% (viii) NaBH4, CeCl3·7H2O, MeOH, 0 °C, 96%; (ix) 6,6-di-Boc-adenine, Ph3P, DIAD, THF, 73%; (x) O3, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, then NaBH4/MeOH, 92%; (xi) trifluoroacetic acid, CH2Cl2, 96%; (xii) phthalimide, PPh3, DIAD, THF, 92%; (xiii) NH2NH2, EtOH, 80 °C, 99%; (xiv) acetone, NaCNBH3, MeOH, 95%; (xv) Methyl acrylate, MeOH, 65 °C, 99%; (xvi) LiAlH4, THF, −15 °C, 90%; (xvii) 4-tBuPhNCO, CH2Cl2, 95%; (xviii) HCl, MeOH, 92%.

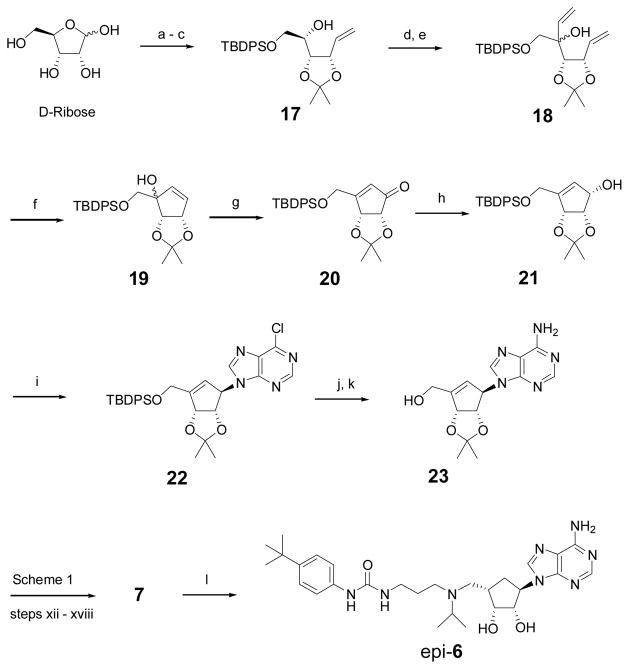

Compound 7 as well as epi-6, a diastereomer of 6 that can be used to determine the importance of the stereochemistry at 4′-position, were synthesized according to Scheme 2. The 2′,3′-dihydroxyls of D-ribose were protected with an acetonide and the 5′-OH subsequently with a tert-butyldiphenylsilyl (TBDPS) group. A wittig reaction of the product with CH2=PPh3 gave compound 17, whose 4′-OH was oxidized with SO3-pyridine, followed by an addition of a vinyl group to give diene 18. A ring closing metathesis reaction produced cyclopentene compound 19 with a tertiary allylic –OH, which was subjected to a pyridinium dichromate (PDC) mediated oxidation, affording cyclopentenone 20. It was stereoselectively reduced to compound 21 with a β-OH at the 1′-position. A Mitsunobu reaction of 21 with 6-chloropurine, followed by aminolysis of the obtained chloride 22 and 5′-deprotection of the silyl group, produced the key cyclopentene intermediate 23, corresponding to the cyclopentane analog 13 in Scheme 1. Using steps xii – xviii in Scheme 1, compound 23 was transformed to the product 7 with an overall yield of 29.2% from D-ribose. Hydrogenation of 7 from the less hindered up side of the cyclopentene ring gave compound epi-6 in 91% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis for compounds 7 and epi-6. Reagents and conditions: (a) acetone, cat. H2SO4, 85%; (b) TBDPSCl, Et3N, 4-dimethylaminopyridine, DMF, 98%; (c) Ph3PMeBr, t-BuOK, THF, 92%; (d) SO3·Py, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 97%; (e) CH2=CHMgBr, THF, −78 °C, 93%; (f) 2nd generation Grubbs catalyst (5 mmol%), CH2Cl2, reflux, 95%; (g) PDC, 4 Å molecular sieve, DMF, 87%; (h) NaBH4, CeCl3·7H2O, MeOH, 0 oC, 98%; (i) 6-chloropurine, Ph3P, DIAD, THF, 95%; (j) 7 M NH3 in MeOH, 100 °C; (k) tetrabutylammonium fluoride, THF, 93% for two steps; (l) H2, 10% Pd/C, MeOH, 91%.

Biological activity evaluation

Compounds 6, 7 and epi-6 were tested for their inhibitory activities against recombinant human DOT1L, together with 4 as a control. As shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1, carbocyclic analogs 6 and 7 exhibited a very high potency against the enzyme with Ki values of 1.1 and 1.3 nM, respectively, showing a comparable activity as inhibitor 4 (Ki = 0.72 nM). In addition to 6 (with a similar structure as 4), the flexible linker between the 5′-position and the urea group in 7 could allow both its adeninylcyclopentene and N-tert-butylphenyl urea moieties occupy the optimal binding sites in DOT1L. There is therefore little binding affinity difference among compounds 4, 6 and 7. However, epi-6 was found to be inactive against DOT1L with a Ki value of >50 μM, showing the corresponding two groups of epi-6 cannot be in the favorable positions due to the trans-orientated 5′-sidechain (relative to 1′-adeninyl). Next, HMT enzyme selectivity of compounds 6 and 7 was evaluated. As with their adenosine-containing analog 4, these two potent DOT1L inhibitors 6 and 7 were found to have no activity against three representative histone methyltransferases CARM1, PRMT1 and SUV39H1 (Table 1). This is in contrast to another DOT1L inhibitor SAH, which has broad activity against all these HMTs. The excellent selectivity of compounds 6 and 7 should also be due to the hydrophobic urea-containing sidechain. Previous crystallographic studies show the SAM amino acid binding pocket of DOT1L undergoes a large conformational change.14,15 The urea functionality of these inhibitors forms two hydrogen bonds with Asp161 and the 4-tert-butylphenyl group is favorably located in a newly formed hydrophobic pocket of DOT1L, showing the structural basis for the high selectivity over other histone methyltransferases.

Table 1.

Ki (μM) against DOT1L and other HMTs.

| DOT1L | PRMT1 | CARM1 | SUV39H1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAH | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.86 | 4.9 |

| 4 | 0.00072 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 6 | 0.0011 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 7 | 0.0013 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| epi-6 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

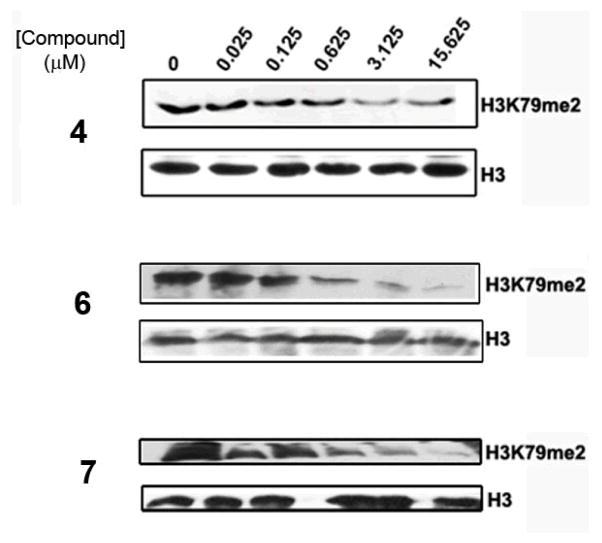

Figure 2 shows that compounds 6 and 7 are able to block H3K79 methylation in human leukemia cell line MV4-11 in a dose-dependent manner. Inhibitor 4 was also used in the study. The IC50 values of compounds 6 and 7 were estimated to be ~0.2 μM, showing a similar cell activity as 4. It is remarkable that the IC50 values of these competitive inhibitors are much higher than their corresponding enzyme Ki values (~1 nM), which is mainly due to a considerably higher concentration of SAM in cells (~300 μM)19 as compared to that used in the enzyme inhibition assay (0.76 μM = the Km value). In addition, cell membrane permeability as well as other factors including stability could also affect cell activities of these compounds.

Figure 2.

Western blot showing inhibition of H3K79 methylation in MV4-11 cells by compounds 4, 6 and 7.

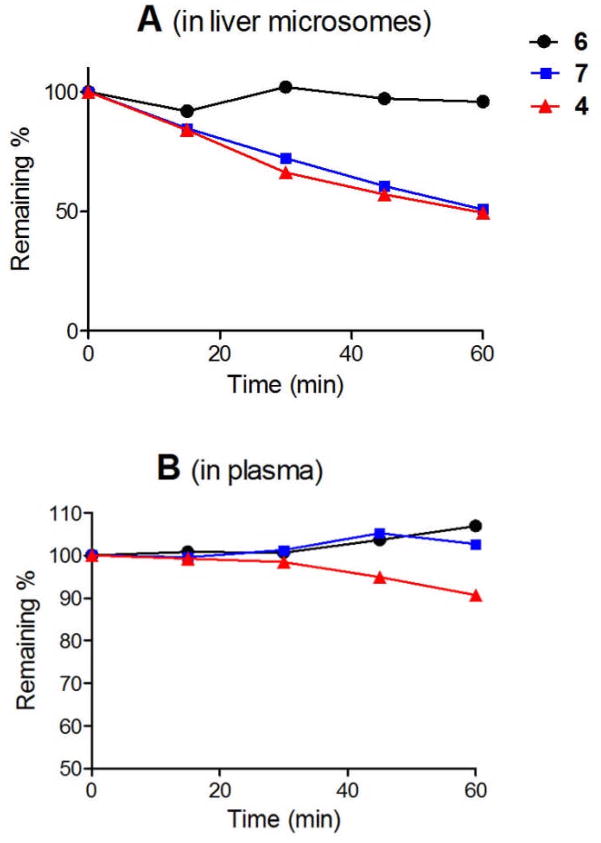

Metabolic stability evaluation

One of the objectives to make the carbocyclic DOT1L inhibitors 6 and 7 is to address the metabolic instability of ribose-containing inhibitors. We next tested the in vitro metabolic stability of potent DOT1L inhibitors 6 and 7 in human plasma and liver microsomes, the latter of which are mainly responsible for drug metabolism. These two assays, especially the liver microsome stability, are standard indicators for predicting in vivo pharmacokinetic parameters of a compound.20,21 Compound 4 was included in the study as a comparison. As shown in Figure 3, although the ribose-containing compound 4 is reasonably stable in human plasma with ~90% remaining after 1 h, it is quickly degraded in the presence of human liver microsomes with only ~50% unchanged after 1 h. The intrinsic clearance (CLint) of 4 is 24.0 μL/min/mg protein (microsomes). This is in line with a study for compound 1, showing a quick degradation and a short half-life in vivo.13 The cyclopentane-containing analog 6 exhibits, however, a very high metabolic stability in both plasma and liver microsomes, with a CLint value of only 0.36 μL/min/mg protein. Unlike 6, the cyclopentene analog 7 can also be metabolized by microsomes with ~half remaining after 1 h treatment (CLint = 22.5 μL/min/mg protein), although it is stable in human plasma containing few metabolic enzymes (Figure 3). This might be due to the C=C double bond in 7 that may be oxidized by, e.g., cytochrome P450 in microsomes. These results show changing the metabolically labile ribose ring to the cyclopentane group could be an effective strategy to produce better drug candidates with favorable pharmacokinetic properties.

Figure 3.

Metabolic stability of DOT1L inhibitors in human liver microsome (up) and plasma (down).

Conclusion

In conclusion, cyclopentane-containing compound 6, an analog of a potent DOT1L inhibitor 4, was synthesized efficiently with an overall yield of 19.3%, starting from readily available D-ribose. 6 potently inhibits human DOT1L with a Ki value of 1.1 nM, but is inactive against other HMTs. In addition, it possesses potent activity in inhibiting cellular H3K79 methylation with an IC50 of ~200 nM. Of particular interest is the metabolic stability of compound 6 without degradation by human plasma and liver microsomes, showing the promise for this class of compounds to be further developed targeting MLL leukemia. In addition, cyclopentene analog 7 was also synthesized, which has almost the same biological activities as those of 6, but lacks desired metabolic stabilities. Epi-6 with a trans-orientated urea sidechain is completely devoid of DOT1L inhibitory activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (RP110050) from Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) and, in part, a grant (R01NS080963) from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS/NIH) to Y.S.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Supplementary Figure S1 and detailed Experimental Section. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Kouzarides T. Cell. 2007;128:693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PA, Baylin SB. Cell. 2007;128:683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole PA. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:590. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copeland RA, Solomon ME, Richon VM. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:724. doi: 10.1038/nrd2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Q, Wang H, Ng HH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Struhl K, Zhang Y. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1052. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00901-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Min J, Feng Q, Li Z, Zhang Y, Xu RM. Cell. 2003;112:711. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada Y, Feng Q, Lin Y, Jiang Q, Li Y, Coffield VM, Su L, Xu G, Zhang Y. Cell. 2005;121:167. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:823. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krivtsov AV, Feng Z, Lemieux ME, Faber J, Vempati S, Sinha AU, Xia X, Jesneck J, Bracken AP, Silverman LB, Kutok JL, Kung AL, Armstrong SA. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:355. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilden JM, Dinndorf PA, Meerbaum SO, Sather H, Villaluna D, Heerema NA, McGlennen R, Smith FO, Woods WG, Salzer WL, Johnstone HS, Dreyer Z, Reaman GH. Blood. 2006;108:441. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao Y, Chen P, Diao J, Cheng G, Deng L, Anglin JL, Prasad BVV, Song Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16746. doi: 10.1021/ja206312b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anglin JL, Deng L, Yao Y, Cai G, Liu Z, Jiang H, Cheng G, Chen P, Dong S, Song Y. J Med Chem. 2012;55:8066. doi: 10.1021/jm300917h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, Majer CR, Sneeringer CJ, Song J, Johnston LD, Scott MP, Smith JJ, Xiao Y, Jin L, Kuntz KW, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Bernt KM, Tseng JC, Kung AL, Armstrong SA, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Pollock RM. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:53. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basavapathruni A, Jin L, Daigle SR, Majer CR, Therkelsen CA, Wigle TJ, Kuntz KW, Chesworth R, Pollock RM, Scott MP, Moyer MP, Richon VM, Copeland RA, Olhava EJ. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;80:971. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu W, Chory EJ, Wernimont AK, Tempel W, Scopton A, Federation A, Marineau JJ, Qi J, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Yi J, Marcellus R, Iacob RE, Engen JR, Griffin C, Aman A, Wienholds E, Li F, Pineda J, Estiu G, Shatseva T, Hajian T, Al-Awar R, Dick JE, Vedadi M, Brown PJ, Arrowsmith CH, Bradner JE, Schapira M. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1288. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JE, Smith GD, Horvatin C, Huang DJ, Cornell KA, Riscoe MK, Howell PL. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:559. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X, Hu Y, Yin DH, Turner MA, Wang M, Borchardt RT, Howell PL, Kuczera K, Schowen RL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1900. doi: 10.1021/bi0262350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang M, Ye W, Schneller SW. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3993. doi: 10.1021/jo040119g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiba P, Wallner C, Kaiser E. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1988;971:38. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(88)90159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obach RS, Baxter JG, Liston TE, Silber BM, Jones BC, MacIntyre F, Rance DJ, Wastall P. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito K, Houston JB. Pharm Res. 2004;21:785. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000026429.12114.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.