Abstract

The yellow-green leaf mutant has a non-lethal chlorophyll-deficient mutation that can be exploited in photosynthesis and plant development research. A novel yellow-green mutant derived from Triticum durum var. Cappelli displays a yellow-green leaf color from the seedling stage to the mature stage. Examination of the mutant chloroplasts with transmission electron microscopy revealed that the shape of chloroplast changed, grana stacks in the stroma were highly variable in size and disorganized. The pigment content, including chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll and carotene, was decreased in the mutant. In contrast, the chla/chlb ratio of the mutants was increased in comparison with the normal green leaves. We also found a reduction in the photosynthetic rate, fluorescence kinetic parameters and yield-related agronomic traits of the mutant. A genetic analysis revealed that two nuclear recessive genes controlled the expression of this trait. The genes were designated ygld1 and ygld2. Two molecular markers co-segregated with these genes. ygld 1 co-segregated with the SSR marker wmc110 on chromosome 5AL and ygld 2 co-segregated with the SSR marker wmc28 on chromosome 5BL. These results will contribute to the gene cloning and the understanding of the mechanisms underlying chlorophyll metabolism and chloroplast development in wheat.

Keywords: durum wheat, yellow-green leaf mutant, genetic mapping, agronomic traits

Introduction

Chlorophyll (Chl) is a vital biomolecule that sustains the life processes of all plants. Chl plays a critical role in photosynthesis by absorbing light and transferring light energy to the reaction centers of the photosynthetic system. Thus, Chl is essential for plant development and agricultural production (Eckhardt et al. 2004, Flood et al. 2011). The phenotypes of leaf color mutations are varied and are affected by different genetic and environment factors. Among the numerous leaf color mutants, the yellow-green leaf color (chlorina) mutant is a special phenotype. The physiology and genetic mechanisms of this mutant are distinct from those of the other leaf color mutants. Yellow-green leaf color mutants have been identified in many higher plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Jarvis et al. 2000, Liu et al. 2003), rice (Jung et al. 2003, Moon et al. 2008), barley (Bellemare et al. 1982, Preiss and Thornber 1995), maize (Asakura et al. 2008, Mei et al. 1998), sunflower (Mashkina and Gus’kov 2002) and wheat (Falbel et al. 1996, Giardi et al. 1995, Hui et al. 2012). The effects of these mutations on chloroplast development, photosynthesis, chlorophyll b accumulation and the levels of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b proteins (Kosuge et al. 2011) have been examined. However, the rate of natural mutation is an estimated 10−5–10−8 in higher plants and is thus notably low. Artificial methods have been applied to obtain these precious mutant resources. Radiation, for example, is an effective way to induce various mutations in higher plants (Morita et al. 2009).

To date, several yellow-green leaf mutant genes have been mapped and cloned. ygl1 is a yellow-green leaf mutant gene in rice. The YGL1 gene encodes an enzyme required for Chl a biosynthesis. A point mutation (Pro-198 to Ser) in the YGL1 gene reduces Chl synthase activity (Wu et al. 2007). chl1 and chl9, which have been isolated from chromosome 3 of two rice chlorina mutants, encode the ChlD and ChlI subunits of Mg-chelatase, respectively. These two genes play an important role in chloroplast development by modulating MgProto (Zhang et al. 2006). In wheat, the homoeologous chlorina loci have been mapped onto the homoeologous group 7 chromosomes. These loci include the cn-A1 locus on chromosome 7A, the cn-B1 locus on the 7B and the cn-D1 on chromosome 7D. These mutations reduce the expression of the light-harvesting Chl a/b complex II (Klindworth et al. 1995, Watanabe and Koval 2003).

In this study, we characterized the yellow-green leaf mutant ygld in durum wheat and mapped the mutated genes of the F2:3 populations with SSR markers. The mutations affecting the agronomic traits were also investigated.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The ygld (yellow-green leaf durum) mutant was introduced from Italy, derived from Triticum durum var. Cappelli treated by gamma radiation (Tomarchio et al. 1983). The mutant displays yellow-green leaves throughout development. The F2:3 segregation populations were used for genetic analysis and mapping. These populations were made by crossing the T. durum cultivar Langdon with the normal green-leaf plant and the ygld mutant.

Pigment content and fluorescence kinetic parameters

The content of Chl (chlorophyll) and Cars (carotenoid) was measured using a DU 800 UV/Vis Spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter) according to the method detailed by Lichtenthaler (1987). The fluorescence kinetic parameters were measured using the Hansatech Fluorecence Monitoring System-FMS-2. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Transmission electron microscopy analysis

The wild-type and ygld mutant leaf samples were collected from 1-week- and 4-week-old plants. All plants were grown under a controlled environment with the same light intensity, temperature and living conditions. First, the leaf sections which were cut to about 5 mm in length from fresh leaves, were quickly fixed in a solution of 2% glutaraldehyde. Next, the sections were fixed in a solution of 1% OsO4 and the samples were stained with uranyl acetate and dehydrated in ethanol. The thin sections were embedded in Spurr’s medium. Finally, the samples were sliced to 50 nm in thickness, and stained again then examined using a JEOL 100 CX electron microscope.

Agronomic trait analysis

The agronomic traits of the F2:3 populations were examined. Both populations were grown in Beijing (39.54°N). The F2 population was planted in 2009 and the F3 population was planted in the fall of 2010. A total of 7 agronomic traits were investigated. These traits included the plant height (cm) (PH), number of spikes per plant (NSP), number of spikelets per spike (NSS), spike length (cm) (SL), number of grains per spike (NGS), grain yield per plant (GYP) and 1000-grain weight (TGW).

Microsatellite analysis

Total DNA was extracted from the sample leaves using the CTAB method (Murray and Thompson 1980). Each PCR reaction was conducted in a total volume of 15 μl containing 1.2 μl of template DNA (approximately 50 ng), 0.09 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl, Fermentas), 1.5 μl of 10 × PCR buffer [200 mM (NH4)2SO4, 750 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8, 25°C)], 1.2 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 0.12 μl of dNTP (25 mM), 1.2 μl of primers (2 μM) and 9.69 μl of H2O. The amplification experiments were subjected to 94°C for 5 min. This step was followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 48–63°C (depending on the microsatellite primer annealing temperature) for 45 s and 72°C for 45 s. The extension step was performed at 72°C for 10 min. Each PCR product was mixed with 3 μl of loading buffer (98% formamide, 0.3% of each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol and 10 mM of EDTA), denatured at 95°C for 5 min and immediately cooled on ice. Electrophoresis was carried out in a 5% denatured polyacrylamide gel with 1 × TBE (90 mM Tris-borate, 2 mM EDTA) for 90 min. A silver-staining experiment was later performed according to the method of Tixier et al. (1997).

Linkage analysis

The F2 generation derived from crossing the yellow-green leaf mutant ygld and T. durum cultivar Langdon was used for mapping. The phenotypes of the F2 individuals were confirmed by investigating the F3 families in the field at different growth stages. A total of 794 F2 individuals were used for genetic mapping. To determine the map position of the ygld genes on the wheat chromosomes, 546 pairs of SSR markers on the whole durum wheat chromosomes were selected from Somers et al. (2004), Paux et al. (2008) and Xue et al. (2008). The polymorphic markers between parents were first picked out. Then BSA (bulked segregant analysis) method was used to screen for the polymorphic markers between the green and yellow-green leaf DNA bulks. Each bulk was composed of 6 individuals from the F2 generation. To exclude the possibility of other reasons which could cause the yellow-green leaf phenotype, all the DNA samples of F2 were phenotypically validated using the F3 families. The MAPMAKER/EXP ver. 3.0 program, which is based on the maximum likelihood method, was used for linkage analysis (Lander et al. 1987). The map distances between markers and genes were derived from the Kosambi function (Kosambi 1944).

Results

Phenotypic characterization of the ygld mutant

Leaf-color mutations are diverse and can occur at different growth stages. The plants with the mutations conferring severe Chl deficiency died early. Some plants with other mutations eventually regained the normal green leaf color (Chen et al. 2009, Dong et al. 2007, Pereira et al. 1997). Compared with the wild-type, the ygld mutant exhibited yellow-green leaves from germination through maturity. Even though the mutant was less vigorous and was delayed in its development, the yellow-green leaf color mutation in the ygld mutant was not lethal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The phenotypes of the ygld mutant and the wild type. A: The phenotypes of the ygld mutant and the wild type at the seedling stage. A mutant with yellow-green leaves is shown on the left. A wild-type plant with normal green leaves is shown on the right. Both are cultivated in the same enviroment for 10 days. B: Phenotypes of the ygld mutant and wild type at the heading stage. A mutant with yellow-green leaves and reduced height is shown in the middle, which is inhibited in growth and about a week later than the normal plants. The wild-type lines are shown on the left.

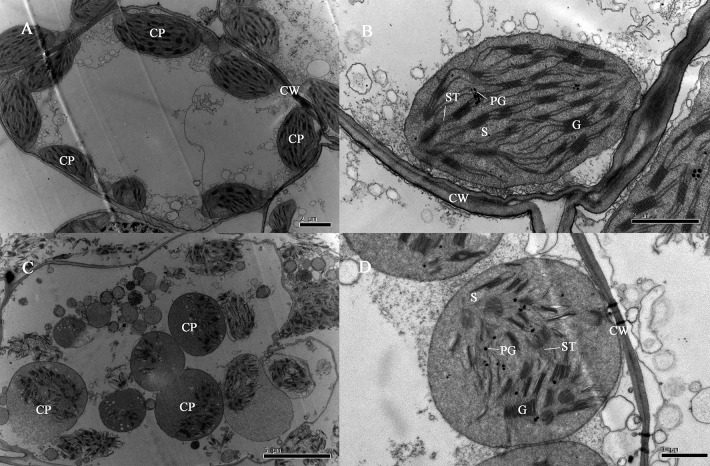

The TEM analysis showed that there were no differences in the size or number of the chloroplasts between the mutant and wild type plants. However, the shape and structure of the chloroplasts were different between groups. The wild-type plants had ellipsoidal chloroplasts. In the ygld mutant, the shape of chloroplasts changed from ellipsoidal to circular. The mutant grana stacks were highly variable in size and appeared disorganized in the stroma region. In the wild type, the chloroplasts had uniform diameters and had approximately parallel grana stacks and lamella (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron microscopic analysis of chloroplasts in the ygld mutant and the wild type. A and B: Chloroplasts in the wild type (wt) plants with normal green leaves. C and D: Chloroplasts in the ygld mutant with yellow-green leaves. CP, chloroplast; PG, plastoglobule; G, grana; S, stroma; CW, cell wall; ST, stroma thylakoid. Scale bars on the lower right corner are 2 μm, 1 μm, 5 μm and 1 μm.

Pigment content and fluorescence kinetic parameter analysis

The quantity of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b) and carotenoid (Car) as well as the ratio of chlorophyll a/chlorophyll b (Chl a/b) were measured. These measurements were compared between groups at different times during development (Table 1). The content of the pigments changed with developmental stage, but the levels of Chl a, Chl b and Car in the mutant were lower throughout development compared with the wild type. Chl accumulation in the mutant was slower than that in wild type and did not reach the wild-type level. Additionally, increasing the Chl a/Chl b ratio meant that Chl b was more reduced than Chl a in the mutant. Therefore, the ygld mutant is deficient especially in Chl b.

Table 1.

The pigment content in the leaves of the wild-type and the ygld mutant in mg g−1 fresh weight

| Growth stage | Genotype | Chl a | Chl b | Car | Chl a/b Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | ygld mutant | 0.99 ± 0.02** | 0.23 ± 0.01** | 0.21 ± 0.02** | 4.38 |

| Wild type | 3.08 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.10 | 2.81 | |

| 4 weeks | ygld mutant | 2.06 ± 0.16** | 0.42 ± 0.10** | 0.38 ± 0.01** | 4.93 |

| Wild type | 4.15 ± 0.22 | 1.39 ± 0.05 | 0.8 ± 0.11 | 2.98 | |

| 10 weeks | ygld mutant | 2.28 ± 0.24** | 0.64 ± 0.18** | 0.46 ± 0.01** | 3.96 |

| Wild type | 4.56 ± 0.36 | 1.67 ± 0.25 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 2.73 |

Chl and Car were measured in acetone extracts from second leaf of different growth stages from top. Values shown are the mean SD (±SD) from three independent determinations.

significant at P < 0.01 by T-test.

The fluorescence kinetic parameters (Table 2) in Fo and Fm of the yellow-green leaf mutant were decreased significantly compared with the wild type. This reduction corresponded to the reduction in chl. The φPSII, NPQ and ETR were decreased by 16.7%, 16.6% and 25.5%, respectively. These results indicated that photosynthesis efficiency was decreased in the mutant. The Fv/Fm values of the wild type and the mutant were not significantly different. This result implied that the primary light energy conversion of PSII in the mutant was retained at wild-type levels (Wang et al. 2009).

Table 2.

Comparison between the fluorescence kinetic parameters of the ygld mutant and the wild type

| Fo | Fm | Fv/Fm | φPSII | qP | NPQ | ETR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 76.5 ± 7.2 | 350.2 ± 30.6 | 0.78 ± 0.003 | 0.42 ± 0.007 | 0.70 ± 0.014 | 1.69 ± 0.406 | 2.71 ± 0.073 |

| Mutant | 45.5 ± 4.0** | 227.5 ± 20.1** | 0.80 ± 0.002 | 0.35** ± 0.005 | 0.66 ± 0.006 | 1.41 ± 0.087 | 2.02** ± 0.131 |

Fo: the minimal fluorescence; Fv: the variable fluorescence; Fm: the maximal fluorescence (Fm = Fo + Fv); Fv/Fm: the primary light energy conversion of PSII; φPSII: quantum yield of photosystem II electron transport; qP: photochemical quenching coefficient; NPQ: non-photochemical quenching; ETR: apparent photo-synthetic electron transport rate.

significant at P < 0.01 by T-test.

The effects of the mutations on yield traits

The yield-related traits of the F2 and parts of the F3 populations were investigated in the 2 crop seasons. To comprehensively understand the effects of the ygld phenotype on the yield-related traits, a survey of 7 agronomic traits was carried out (Table 3). We measured the plant height (cm) (PH), number of spikes per plant (NSP), number of spikelets per spike (NSS), spike length (cm) (SL), number of grains of spike (NGS), grain yield per plant (GYP) and 1000-grain weight (TGW). With the exception of SL, all of the agronomic traits in the mutant were significantly reduced compared with wild-type plants. The Chl deficiency throughout development inhibited photosynthesis and consequently affected the accumulation of biomass and the development of the plant.

Table 3.

The relationship between the phenotypes and seven yield-related traits

| Phenotype | Trait | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| PH | TGW | SL | NSP | NSS | NGS | GYP | |

| Wild type | 132.9 ± 11 | 34.6 ± 8.1 | 9.5 ± 4.6 | 23.4 ± 2.7 | 46.8 ± 9.1 | 272.6 ± 171.0 | 9.5 ± 6.5 |

| Mutant | 102.8 ± 14.5** | 20.4 ± 5.8** | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 19.5 ± 3.4** | 31.1 ± 8.5** | 45.7 ± 23.1** | 1.0 ± 0.6** |

plant height (cm) (PH), number of spikes per plant (NSP), number of spikelets per spike (NSS), spike length (cm) (SL), number of grains of spike (NGS), grain yield per plant (GYP), 1000-grain weight (TGW),

significant at P < 0.01 by T-test.

Genetic analysis of the ygld phenotype

The F2 population, which was derived from crossing the ygld mutant with Langdon, was used to investigate the Mendelian segregation ratio. The F2 population contained 794 individuals in total: 51 of them exhibited yellow-green leaves, whereas the other individuals showed normal green leaves. A χ2 analysis was applied to test for the deviation of the ygld mutant in the F2 population from the expected segregation ratio of 15:1 (χ2(15:1) = 0.0056, p > 0.9). The segregation ratio indicated that the ygld phenotype was controlled by two recessive nuclear genes. Neither gene alone could give rise to the leaf color abnormality. The genes were designated as ygld1(yellow-green leaf durum 1) and ygld2 (yellow-green leaf durum 2).

Genetic mapping of the two recessive genes

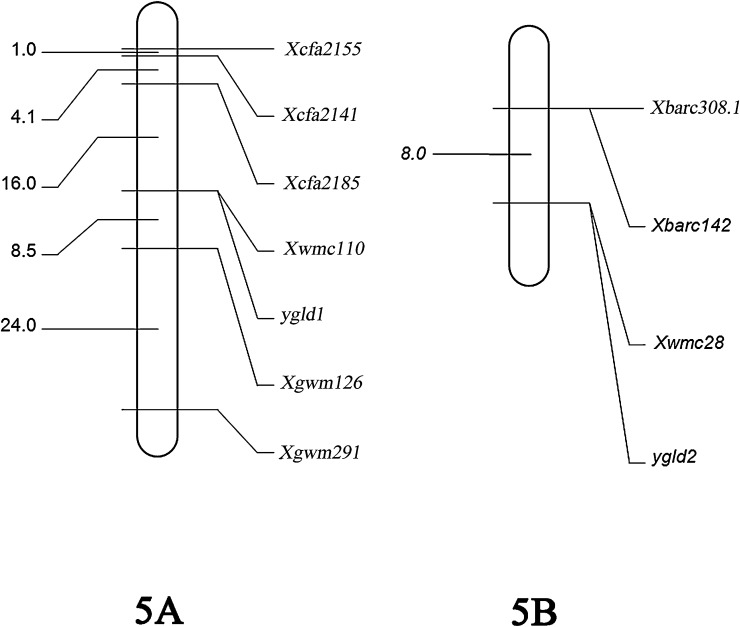

To map the ygld1and ygld2 genes, 546 pairs of markers were screened for polymorphisms. Among these markers, 132 pairs showed polymorphisms between the two parents. Six and 3 SSR markers were linked with the ygld1 and ygld2 genes, respectively (Table 4 and Fig. 3). The gene ygld1 was located on chromosome 5AL and was flanked by the SSR markers cfa2185 and cfa126 at genetic distances of 16.0 cM and 8.5 cM, respectively. Moreover, the SSR marker wmc110 co-segregated with ygld1. The ygld2 gene was mapped onto chromosome 5BL with 3 markers. Barc142 and barc308 were both at a distance of 8.0 cM and the SSR marker wmc28 cosegregated with ygld2 (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Molecular markers used for mapping the genes of ygld1 and ygld2

| Marker | Tm (°C) | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cfa2155 | 60 | TTTGTTACAACCCAGGGGG | TTGTGTGGCGAAAGAAACAG |

| cfa2141 | 60 | GAATGGAAGGCGGACATAGA | GCCTCCACAACAGCCATAAT |

| cfa2185 | 60 | TTCTTCAGTTGTTTTGGGGG | TTTGGTCGACAAGCAAATCA |

| wmc110 | 61 | GCAGATGAGTTGAGTTGGATTG | GTACTTGGAAACTGTGTTTGGG |

| gwm126 | 60 | CACACGCTCCACCATGAC | GTTGAGTTGATGCGGGAGG |

| gwm291 | 60 | CATCCCTACGCCACTCTGC | AATGGTATCTATTCCGACCCG |

| barc308 | 55 | GCGATCTTGCGTGTGCGTAGGA | GCGTGGGATGCAAGTGAACAAT |

| barc142 | 52 | CCGGTGAGAGGACTAAAA | GGCCTGTCAATTATGAGC |

| wmc28 | 51 | ATCACGCATGTCTGCTATGTAT | ATTAGACCATGAAGACGTGTAT |

Fig. 3.

Genetic map showing the ygld1 gene on chromosome 5A with the SSR co-segregation marker wmc110 and the ygld2 gene on chromosome 5B with the SSR co-segregation marker wmc28.

Discussion

Chloroplasts and Chl are essential for photosynthesis in higher plants. This fundamental process sustains the life on earth (Chen et al. 2005, Inaba and Ito-Inaba 2010, Wang et al. 2009). Chl a is a component of the light-harvesting complexes (LHCs) and photosynthetic reaction centers. Chl b is located in the light-harvesting pigment protein complexes of the PSI and PSII (Masuda et al. 2003, Oster et al. 2000). Previous studies have indicated that mutants with a higher Chl a/Chl b ratio have lower LHC levels. As a result of the limited chl content, these mutants have abnormal thylakoid membranes (Falbel and Staehelin 1996, Marco et al. 1989). The ygld mutant with the yellow-green leaf phenotype is a chlorophyll deficient mutant. This mutant has a high chl a/chl b ratio and has decreased chl a, chl b, carotenoid levels. These results indicate that the LHC content may be lower in the mutant than in the wild type. Furthermore, the PSII of the ygld mutant was not significantly affected according to our measurements of the fluorescence parameters. This result indicated that the PSI in the ygld mutant was impaired by the mutation. Thus, the abnormal pigment content and chloroplast structure in the ygld mutant may have contributed to the partial repression of chl synthesis. Plants with normal leaf colors have higher chlorophyll content and normal chloroplasts. These characteristics allow the plants to absorb more energy and be more efficient at photosynthesis (Lawlor 2009, Luo and Ren 2006, Wang et al. 2003, Wang et al. 2010). Therefore, the wild-type plants grow vigorously. The chloroplasts in many leaf color mutants are irreversibly abnormal from the early stages of leaf development (An et al. 2011). Therefore, the mutations affect the accumulation of both Chl and biomass throughout plant development. The ygld mutant can carry out photosynthesis but grows slowly compared to the wild type. Almost all of the agronomic traits were reduced significantly in ygld, but the influence on SL was limit. Further study on the genes of ygld would contribute to the improvement in breeding. The study could be useful to understand genetic mechanism of chloroplast biogenesis and exploit in the improvement for wheat photosynthesis. Moreover the differentiation in leaf color could be a significant marker. Leaf color mutant has been used successfully in rice breeding to monitor seed purity in seed production as a phenotypic marker (Chen et al. 2007).

Many of these yellow-green leaf mutations have been genetically characterized and used as genetic markers. In rice, 11 yellow-green leaf mutants (chl 1 to10 and ygl1) have been identified. All of these phenotypes are controlled by a single recessive gene (www.gramene.com). Moreover, several yellow-green leaf mutants have been identified from tetraploid wheat (Triticum turgidum L.). Further analysis showed that most yellow-green leaf mutants are also controlled by a single recessive gene (Klindworth et al. 1995, Luo and Ren 2006, Williams et al. 1985). However, Smith identified a mutant controlled by a dominant gene (Smith 1952). Additionally, Varughese and Swaminathan (1968) found a yellow-green leaf trait that was controlled by two recessive genes, but no further analysis was conducted. In the current study, we identified a new yellow-green leaf mutation that was controlled by two complementary recessive genes, specifically, ygld1 and ygld2. These two genes were mapped onto chromosome 5AL and 5BL with the co-segregating markers wmc110 and wmc28, respectively and these two genes might have homoeologous relationship due to their locations. The analysis of the mapping locations and phenotypes showed that ygld1 and ygld2 were different from the previously reported genes associated with yellow-green leaf color alterations. Thus, ygld1 and ygld2 are novel genes.

Acknowlegements

We are grateful to Juncheng Zhang for his valuable suggestion on genetic mapping, and Yiyuan Li, Lingli Zheng, Lei Pan for their work on phenotype investigaion. This work was supported by National Transgenic Research Project (2008ZX08009-001).

Literature Cited

- An, S.J., Pandeya, D., Park, S.W., Li, J., Kwon, J.K., Koeda, S., Hosokawa, M., Paek, N.C., Choi, D., and Kang, B.C. (2011) Characterization and genetic analysis of a low-temperature-sensitive mutant, sy-2, in Capsicum chinense. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 459–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura, Y., Kikuchi, S., and Nakai, M. (2008) Non-identical contributions of two membrane-bound cpSRP components, cpFtsY and Alb3, to thylakoid biogenesis. Plant J. 56: 1007–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare, G., Bartlett, S.G., and Chua, N.H. (1982) Biosynthesis of chlorophyll a/b-binding polypeptides in wild type and the chlorina f2 mutant of barley. J. Biol. Chem. 257: 7762–7767 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G., Bi, Y.R., and Li, N. (2005) EGY1 encodes a membrane-associated and ATP-independent metalloprotease that is required for chloroplast development. Plant J. 41: 364–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T., Zhang, Y., Zhao, L., Zhu, Z., Lin, J., Zhang, S., and Wang, C. (2007) Physiological character and gene mapping in a new green-revertible albino mutant in rice. J. Genet. Genomics 34: 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T., Zhang, Y., Zhao, L., Zhu, Z., Lin, J., Zhang, S., and Wang, C. (2009) Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of a green-revertible albino gene gra(t) in rice. J. Genet. Genomics 36: 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.L., Deng, Y., Mu, J.Y., Lu, Q.T., Wang, Y.Q., Xu, Y.Y., Chu, C.C., Chong, K., Lu, C.M., and Zuo, J.R. (2007) The Arabidopsis Spontaneous Cell Death1 gene, encoding a zeta-carotene desaturase essential for carotenoid biosynthesis, is involved in chloroplast development, photoprotection and retrograde signalling. Cell Res. 17: 575–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, U., Grimm, B., and Hortensteiner, S. (2004) Recent advances in chlorophyll biosynthesis and breakdown in higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 56: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falbel, T.G., Meehl, J.B., and Staehelin, L.A. (1996) Severity of mutant phenotype in a series of chlorophyll-deficient wheat mutants depends on light intensity and the severity of the block in chlorophyll synthesis. Plant Physiol. 112: 821–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falbel, T.G., and Staehelin, L.A. (1996) Partial blocks in the early steps of the chlorophyll synthesis pathway: A common feature of chlorophyll b-deficient mutants. Physiol. Plantarum 97: 311–320 [Google Scholar]

- Flood, P.J., Harbinson, J., and Aarts, M.G. (2011) Natural genetic variation in plant photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 16: 327–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardi, M.T., Kucera, T., Briantais, J.M., and Hodges, M. (1995) Decreased photosystem II core phosphorylation in a yellow-green mutant of wheat showing monophasic fluorescence induction curve. Plant Physiol. 109: 1059–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Z., Tian, F.X., Wang, G.K., Wang, G.P., and Wang, W. (2012) The antioxidative defense system is involved in the delayed senescence in a wheat mutant tasg1. Plant Cell Rep. 31: 1073–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba, T., and YIto-Inaba, Y. (2010) Versatile roles of plastids in plant growth and development. Plant Cell Physiol. 51: 1847–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, P., Dormann, P., Peto, C.A., Lutes, J., Benning, C., and Chory, J. (2000) Galactolipid deficiency and abnormal chloroplast development in the Arabidopsis MGD synthase 1 mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 8175–8179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.H., Hur, J., Ryu, C.H., Choi, Y., Chung, Y.Y., Miyao, A., Hirochika, H., and An, G. (2003) Characterization of a rice chlorophyll-deficient mutant using the T-DNA gene-trap system. Plant Cell Physiol. 44: 463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klindworth, D.L., Williams, N.D., and Duysen, M.E. (1995) Genetic-analysis of chlorina mutants of durum-wheat. Crop Sci. 35: 431–436 [Google Scholar]

- Kosambi, D.D. (1944) The estimation of map distance from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 12: 172–175 [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge, K., Watanabe, N., and Kuboyama, T. (2011) Comparative genetic mapping of homoeologous genes for the chlorina phenotype in the genus Triticum. Euphytica 179: 257–263 [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E.S., Green, P., Abrahamson, J., Barlow, A., Daly, M.J., Lincoln, S.E., and Newberg, L.A. (1987) MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1: 174–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor, D.W. (2009) Musings about the effects of environment on photosynthesis. Ann. Bot. 103: 543–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. (1987) Chlorophylls and carotenoids, the pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In: Douce, R., and Packer, L. (eds.) Methods Enzymol., 148, Academic Press Inc., New York, pp. 350–382 [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., Hong, S.W., Escobar, M., Vierling, E., Mitchell, D.L., Mount, D.W., and Hall, J.D. (2003) Arabidopsis UVH6, a homolog of human XPD and yeast RAD3 DNA repair genes, functions in DNA repair and is essential for plant growth. Plant Physiol. 132: 1405–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, P.G., and Ren, Z.L. (2006) Wheat leaf chlorosis controlled by a single recessive gene. J. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 32: 330–338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco, G.D., D’Ambrosio, N., Giardi, M.T., Massacci, A., and Tricoli, D. (1989) Photosynthetic properties of leaves of a yellow green mutant of wheat compared to its wild type. Photosynth. Res. 21: 117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashkina, E.V., and Gus’kov, E.P. (2002) Cytogenetic effect of temperature on the sunflower varieties. Tsitologiia 44: 1220–1226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, T., Fusada, N., Oosawa, N., Takamatsu, K., Yamamoto, Y.Y., Ohto, M., Nakamura, K., Goto, K., Shibata, D., Shirano, Y.et al. (2003) Functional analysis of isoforms of NADPH: protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (POR), PORB and PORC, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell physiol. 44: 963–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei, M., Qiu, Y., Sun, Y., Huang, R., Yao, J., Zhang, Q., Hong, M., and Ye, J. (1998) Morphological and molecular changes of maize plants after seeds been flown on recoverable satellite. Adv. Space Res. 22: 1691–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S., Giglione, C., Lee, D.Y., An, S., Jeong, D.H., Meinnel, T., and An, G. (2008) Rice peptide deformylase PDF1B is crucial for development of chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 49: 1536–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, R., Kusaba, M., Iida, S., Yamaguchi, H., Nishio, T., and Nishimura, M. (2009) Molecular characterization of mutations induced by gamma irradiation in rice. Genes Genet. Syst. 84: 361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.G., and Thompson, W.F. (1980) Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8: 4321–4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster, U., Tanaka, R., Tanaka, A., and Rudiger, W. (2000) Cloning and functional expression of the gene encoding the key enzyme for chlorophyll b biosynthesis (CAO) from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 21: 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paux, E., Sourdille, P., Salse, J., Saintenac, C., Choulet, F., Leroy, P., Korol, A., Michalak, M., Kianian, S., Spielmeyer, W.et al. (2008) A physical map of the 1-gigabase bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science 322: 101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, T.N., Ilarslan, H., and Palmer, R.G. (1997) Genetic and cytological analyses of three lethal ovule mutants in soybean (Glycine max; Leguminosae). Genome 40: 273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss, S., and Thornber, J.P. (1995) Stability of the apoproteins of light-harvesting complex I and II during biogenesis of thylakoids in the chlorophyll b-less barley mutant chlorina f2. Plant Physiol. 107: 709–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. (1952) A rare dominant chlorophyll mutant in durum wheat: Induced by atomic bomb irradiation. J. Hered. 43: 125–128 [Google Scholar]

- Somers, D.J., Isaac, P., and Edwards, K. (2004) A high-density wheat microsatellite consensus map for bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 1105–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tixier, M.H., Sourdille, P., Röder, M., Leroy, P., and Bernard, M. (1997) Detection of wheat microsatellites using a non radioactive silver-nitrate staining method. J. Genet. Breed. 51: 175–177 [Google Scholar]

- Tomarchio, L., Triolo, L., and Dimarco, G. (1983) Photosynthesis, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase, electron transport, and ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate of virescent and normal green wheat leaves. Plant Physiol. 73: 192–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varughese, G.S., and Swaminathan, M.S. (1968) A comparison of the frequency and spectrum of mutations induced by gamma rays and EMS in wheat. Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding 28: 158–165 [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Lan, T., Wu, W.R., and Li, W.M. (2003) Mapping of QTLs controlling chlorophyll content in rice. Acta Genetica Sinica 30: 1127–1132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., Ouyang, M., Li, Q., Zou, M., Guo, J., Ma, J., Lu, C., and Zhang, L. (2010) The Arabidopsis chloroplast ribosome recycling factor is essential for embryogenesis and chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 74: 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.S., Sang, X.C., Ling, Y.H., Zhao, F.M., Yang, Z.L., Li, Y.F., and He, G.H. (2009) Genetic analysis and molecular mapping of a novel gene for zebra mutation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Genet. Genomics 36: 679–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, N., and Koval, S.E. (2003) Mapping of chlorina mutant genes on the long arm of homoeologous group 7 chromosomes in common wheat with partial deletion lines. Euphytica 129: 259–265 [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N.D., Joppa, L., Duysen, M.E., and Freeman, T.P. (1985) Inheritance of three chlorophyll-deficient mutants of common wheat. Crop Sci. 25: 1023–1025 [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z., Zhang, X., He, B., Diao, L., Sheng, S., Wang, J., Guo, X., Su, N., Wang, L., Jiang, L.et al. (2007) A chlorophyll-deficient rice mutant with impaired chlorophyllide esterification in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 145: 29–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S., Zhang, Z.Z., Lin, F., Kong, Z.X., Cao, Y., Li, C., Yi, H.Y., Mei, M.F., Zhu, H.L., Wu, J.Z.et al. (2008) A high-density intervarietal map of the wheat genome enriched with markers derived from expressed sequence tags. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117: 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Li, J., Yoo, J.H., Yoo, S.C., Cho, S.H., Koh, H.J., Seo, H.S., and Paek, N.C. (2006) Rice chlorina-1 and chlorina-9 encode ChlD and ChlI subunits of Mg-chelatase, a key enzyme for chlorophyll synthesis and chloroplast development. Plant Mol. Biol. 62: 325–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]