Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Birth defects (BDs) are an important cause of infant mortality and disproportionately occur among low birth weight infants. We determined the prevalence of BDs in a cohort of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants cared for at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network (NRN) centers over a 10-year period and examined the relationship between anomalies, neonatal outcomes, and surgical care.

METHODS:

Infant and maternal data were collected prospectively for infants weighing 401 to 1500 g at NRN sites between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2007. Poisson regression models were used to compare risk of outcomes for infants with versus without BDs while adjusting for gestational age and other characteristics.

RESULTS:

A BD was present in 1776 (4.8%) of the 37 262 infants in our VLBW cohort. Yearly prevalence of BDs increased from 4.0% of infants born in 1998 to 5.6% in 2007, P < .001. Mean gestational age overall was 28 weeks, and mean birth weight was 1007 g. Infants with BDs were more mature but more likely to be small for gestational age compared with infants without BDs. Chromosomal and cardiovascular anomalies were most frequent with each occurring in 20% of affected infants. Mortality was higher among infants with BDs (49% vs 18%; adjusted relative risk: 3.66 [95% confidence interval: 3.41–3.92]; P < .001) and varied by diagnosis. Among those surviving >3 days, more infants with BDs underwent major surgery (48% vs 13%, P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Prevalence of BDs increased during the 10 years studied. BDs remain an important cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality among VLBW infants.

Keywords: birth defects, prematurity, Neonatal Research Network, low birth weight

What’s Known on This Subject:

Infants with birth defects are more likely to be born preterm or with low birth weight and are at higher risk of death.

What This Study Adds:

This study describes the prevalence of birth defects in a cohort of very low birth weight infants and evaluates in-hospital surgical procedures, morbidity, and mortality.

In the United States, birth defects (BDs) are a leading cause of infant mortality, accounting for an estimated 20% of all infant deaths.1 Population-based epidemiologic data demonstrate an association between preterm birth or low birth weight and various BDs.2–8 The extent to which BDs may impact neonatal morbidity and mortality associated with preterm delivery remains unclear. Improved understanding of the frequency of BDs and outcomes in premature or low birth weight infants may help guide medical decision-making and counseling to families of affected newborns. We described the prevalence of BDs in a cohort of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants hospitalized at centers of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN) over a 10-year period and examined the impact of anomalies on outcomes and surgical care.

Methods

Infants weighing 401 to 1500 g born January 1, 1998, through December 31, 2007, at NRN centers or admitted within 14 days of birth were studied. Maternal demographic, pregnancy, and delivery information and infant data collected from birth to discharge, death, or 120 days were entered into the NRN registry of VLBW infants.9 This was the longest recent period during which information about BDs was collected consistently and before a change in registry eligibility in 2008. For infants still hospitalized at 120 days, a limited set of clinical outcomes occurring after 120 days was entered in the registry including discharge date or death up to 1 year of age. The registry was approved by the institutional review board at each center.

Infant data included birth weight (BW), gestational age (GA), gender, race/ethnicity, mode of delivery, receipt of antenatal steroids, final status, and cause of death. Small for GA (SGA) was defined as BW <10th percentile for gender and GA based on Alexander percentiles.10 Morbidities diagnosed during the initial hospital stay were recorded for infants surviving >12 hours, including patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), modified Bell’s stage ≥ IIA necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC),11,12 respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) defined based on clinical features and oxygen or respiratory support for > 6 hours of the first 24 hours, late-onset sepsis (LOS; >72 hours) defined by positive culture and antibiotic therapy ≥5 days, severe (grade 3 or 4) intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) classified by Papile criteria,13 periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) based on need for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA).

Major BDs were recorded by using codes from a predefined list in the study manual of operations with defects not listed described in text fields.9 Specific information was also entered in a text field for deaths attributed to BDs. Information from the defined codes and text fields was used to classify each infant with a major BD into 1 of the following categories modeled on those reported by Suresh et al14 for the Vermont Oxford Network (VON): chromosomal anomalies; named syndromes, sequences, and associations; 1 or more major BD of a single organ system (nervous system, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, bone and skeletal, miscellaneous single system anomalies); inborn errors of metabolism; and other multiple system anomalies. Each infant was assigned to 1 category only. Infants with anomalies in more than 1 category were classified into 1 category in the following order: chromosomal anomaly, named conditions, and other multiple system anomalies. Hydrops fetalis (43 cases) and oligohydramnios sequence (33 cases) were not counted as major BDs for this analysis, which contrasts with the VON report that included these conditions under named syndromes, sequences, and associations. Conditions not counted as BDs for this analysis are shown in the Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics and outcomes were compared for infants with and without BDs. Statistical significance for unadjusted comparisons was determined by χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate median length of hospital stay (time from birth to discharge with deaths treated as censored observations) with statistical significance between groups determined by the log-rank test.

Adjusted analyses were conducted by using Poisson regression models with robust variance estimators to assess trends in prevalence of infants with major BDs over the study period, risk for BDs associated with neonatal characteristics, and risk of death and morbidities for infants with and without BDs.15 Linear trends in prevalence were assessed by including birth year as a continuous variable, along with study center, mother’s age, race/ethnicity, and outborn status in a model with a binary BD indicator as the dependent variable. Models used to assess risk of BDs included effects for the characteristics of interest as noted in the table footnote. Models comparing outcomes between infants with and without BDs included a binary BD indicator along with effects for study center, GA, SGA, gender, and race (categories described in table footnotes). Two separate models were used to assess whether risk of death varied by race/ethnicity or over time in the subset of infants with BDs. Both models in this subset included effects for study center, GA, SGA, gender, race/ethnicity, and birth year, with an interaction term between racial group and birth year included in 1 model to assess whether yearly trend in mortality varied by race/ethnicity. Adjusted relative risks (RRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and Score or Wald χ2 tests from these models are reported. Statistical testing was considered hypothesis generating and therefore P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

Study Population

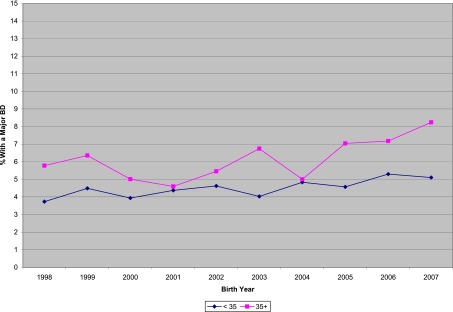

Between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2007, 37 262 VLBW infants were born at or admitted to 1 of 22 NRN study centers and included in the registry. A major BD was reported for 1776 (4.8% overall; 3.1% to 11.3% of infants at individual centers). Over the 10-year period, the proportion of infants with BDs each year ranged from 4.0% in 1998 to 5.6% in 2007, with an increasing linear trend across the years (adjusted RR for yearly trend: 1.03 [95% CI: 1.01–1.05], P = .002). Results were similar in the subset of 11 centers that enrolled infants in all 10 years. The increase in prevalence was seen among mothers 35 years and older, as well as those under 35 (no difference between groups, P = .31, Fig 1). The proportion of infants born with a cardiovascular defect increased but remained low, ranging from 0.7% in 1998 to 1.3% in 2007 (adjusted RR for yearly trend: 1.05 [1.01–1.09], P = .02; results similar in the subset of 11 centers). Statistically significant changes were not found over the period in the proportions of infants born with BDs in the chromosomal, nervous system, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary anomaly categories. We were unable to evaluate trends over time for specific anomalies within a category due to limited numbers of cases.

FIGURE 1.

Percent of VLBW infants in the NRN with a major BD by birth year among infants whose mothers were <35 years old vs 35 years or older.

Infants studied were nearly all premature (<37 weeks GA, 99.8%) and had mean GA of 28 weeks and mean BW of 1007 g (Table 1). In this cohort defined by BW, the proportion of SGA infants increased with increasing GA. Infants with BDs weighed more at birth than infants without BDs (1057 vs 1004 g, P < .001), were born at later GA (mean: 29 vs 28 weeks, P < .001), and a greater proportion were SGA (40% vs 20%, P < .001). The proportion of infants born with a major BD was higher for mothers ≥35 years of age than for those <25 (Table 2), especially for mothers ≥40 years (7.8% vs 4.6%; adjusted RR: 1.70 [1.40–2.08]). A smaller percent of non-Hispanic black than non-Hispanic white infants had BDs (3.7% vs 5.3%; adjusted RR: 0.68 [0.60–0.78]).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of VLBW Infants in the NRN Cohort Born in 1998–2007

| Characteristica | All infants, N = 37 262 | Infants With BDs, N = 1776 | Infants Without BDs, N = 35 486 | P b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.0 (6.7) | 28.0 (7.1) | 27.0 (6.7) | .007 |

| Category, n (%) | ||||

| <25 | 14 869 (40) | 685 (39) | 14 184 (40) | — |

| 25–29 | 8677 (23) | 407 (23) | 8270 (23) | — |

| 30–34 | 7887 (21) | 326 (18) | 7561 (21) | — |

| 35–39 | 4546 (12) | 259 (15) | 4287 (12) | — |

| 40+ | 1263 (3) | 99 (6) | 1164 (3) | — |

| Antenatal steroids, n (%) | 27 501 (74) | 1093 (62) | 26 408 (75) | <.001 |

| Cesarean delivery, n (%) | 22 337 (60) | 1122 (63) | 21 215 (60) | .005 |

| Multiple birth, n (%) | 9573 (26) | 328 (18) | 9245 (26) | <.001 |

| GA, wk | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 28 (3.1) | 29 (3.5) | 28 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Category, n (%) | ||||

| <22 | 377 (1) | 20 (1) | 357 (1) | — |

| 22–24 | 6051 (16) | 148 (8) | 5903 (17) | — |

| 25–28 | 15 531 (42) | 583 (33) | 14 948 (42) | — |

| 29–32 | 13 158 (35) | 740 (42) | 12 418 (35) | — |

| 33+ | 2135 (6) | 284 (16) | 1851 (5) | — |

| SGA, n (%) | 7731 (21) | 702 (40) | 7029 (20) | <.001 |

| SGA by GA category, % | <.001 | |||

| <22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| 22–24 | 4 | 4 | 4 | — |

| 25–28 | 8 | 14 | 8 | — |

| 29–32 | 31 | 45 | 30 | — |

| 33+ | 100 | 100 | 100 | — |

| BW, g | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1007 (304) | 1057 (294) | 1004 (305) | <.001 |

| Category, n (%) | ||||

| 401–750 | 9526 (26) | 325 (18) | 9201 (26) | — |

| 751–1000 | 8546 (23) | 422 (24) | 8124 (23) | — |

| 1001–1250 | 8985 (24) | 467 (26) | 8518 (24) | — |

| 1251–1500 | 10 205 (27) | 562 (32) | 9643 (27) | — |

| Boy, n (%) | 18 934 (51) | 842 (47) | 18 092 (51) | .004 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 14 249 (38) | 534 (30) | 13 715 (39) | — |

| Non-Hispanic white | 14 962 (40) | 787 (45) | 14 175 (40) | — |

| Hispanic | 6317 (17) | 367 (21) | 5950 (17) | — |

| Other | 1630 (4) | 77 (4) | 1553 (4) | — |

| Outborn, n (%) | 4315 (12) | 336 (19) | 3979 (11) | <.001 |

| Apgar ≤ 3 at 1 min, n (%) | 11 748 (32) | 791 (45) | 10 957 (31) | <.001 |

| Apgar ≤ 3 at 5 min, n (%) | 4230 (12) | 369 (21) | 3861 (11) | <.001 |

Information was missing for maternal age: 20 infants; antenatal steroids: 181; cesarean delivery: 29; multiple birth: 1; GA: 10; SGA: 10; gender: 4; race: 104; Apgar at 1 minute: 519; Apgar at 5 minutes: 504.

P value for a test between infants with BDs versus no BDs by the Wilcoxon test (means for maternal age, BW, GA), Fisher’s exact test, or the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test (SGA controlling for GA). Tests assessed differences in the distribution of each characteristic overall. P values for differences in the categorical distributions of maternal age, BW, and GA are not shown, and tests between individual categories (eg, Non-Hispanic black) of characteristics categorized as more than two levels were not performed (as indicated by dashes).

TABLE 2.

Frequency and Risk of Major BDs by Infant Characteristics

| Characteristica | N | Infants With a BD, n (%) | Adjusted RR for BDs (95% CI)b | P b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | <.001 | |||

| 40+ | 1263 | 99 (7.8) | 1.70 (1.40–2.08) | — |

| 35–39 | 4546 | 259 (5.7) | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | — |

| 30–34 | 7887 | 326 (4.1) | 0.94 (0.82–1.07) | — |

| 25–29 | 8677 | 407 (4.7) | 1.03 (0.92–1.17) | — |

| <25 | 14 869 | 685 (4.6) | 1.0 | — |

| Multiple birth | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 9573 | 328 (3.4) | 0.66 (0.59–0.75) | — |

| No | 27 688 | 1448 (5.2) | 1.0 | — |

| BW, g | <.001 | |||

| 401–500 | 1556 | 59 (3.8) | 0.66 (0.50–0.86) | — |

| 501–750 | 7970 | 266 (3.3) | 0.61 (0.53–0.71) | — |

| 751–1000 | 8546 | 422 (4.9) | 0.91 (0.80–1.03) | — |

| 1001–1250 | 8985 | 467 (5.2) | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | — |

| 1251–1500 | 10 205 | 562 (5.5) | 1.0 | — |

| GA, wk | <.001 | |||

| <25 | 6428 | 168 (2.6) | 0.36 (0.29–0.45) | — |

| 25–28 | 15 531 | 583 (3.8) | 0.55 (0.46–0.65) | — |

| 29–32 | 13 158 | 740 (5.6) | 0.72 (0.62–0.83) | — |

| 33+ | 2135 | 284 (13.3) | 1.0 | — |

| SGA | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 7731 | 702 (9.1) | 1.80 (1.59–2.03) | — |

| No | 29 521 | 1073 (3.6) | 1.0 | — |

| Boy | .01 | |||

| Yes | 18 934 | 842 (4.4) | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | — |

| No | 18 324 | 932 (5.1) | 1.0 | — |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 14 249 | 534 (3.7) | 0.68 (0.60–0.78) | — |

| Hispanic | 6317 | 367 (5.8) | 1.07 (0.92–1.23) | — |

| Other | 1630 | 77 (4.7) | 0.86 (0.67–1.09) | — |

| Non-Hispanic white | 14 962 | 787 (5.3) | 1.0 | — |

Information was missing for maternal age: 20 infants; multiple birth: 1; GA: 10; SGA: 10; gender: 4; race: 104.

RRs, CIs, and P values by the Score χ2 test from a modified Poisson regression model that included study center, maternal age (categories shown), GA (categories shown), SGA, gender, race (categories shown), multiple birth, cesarean delivery, antenatal steroids, and outborn status. GA and SGA were replaced with BW (categories shown) for estimation of RRs associated with BW. The Score test provides an overall test of association between the characteristic and risk of birth defects. For characteristics with two levels (eg, multiple birth), the P value corresponds to statistical significance for the RR shown. Dashes visually define the rows. For characteristics categorized as more than two levels, dashes are shown to indicate that P values for the pairwise comparisons represented by the relative risks are not shown. Statistically significant RRs are indicated by confidence intervals that do not include 1.0.

Types of Birth Defects

Chromosomal and cardiovascular anomalies were the most frequent types of BDs with each occurring in ∼20% of the 1776 infants affected (Table 3). Nervous system, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and other multiple system anomalies were each seen in 10% to 13%, whereas other types each accounted for <5% of infants with major BDs.

TABLE 3.

Type and Frequency of BDs and Mortality by Type Among VLBW Infants in the NRN Cohort Born in 1998–2007

| Category | No. | % of BDsd | n (%) Who Died Before Discharge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal anomalies | |||

| Trisomy 13 | 34 | — | 30 (88.2) |

| Trisomy 18 | 102 | — | 92 (90.2) |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 96 | — | 38 (39.6) |

| Turner syndrome | 10 | — | 3 (30.0) |

| Triploidy | 17 | — | 16 (94.1) |

| 22q deletion | 12 | — | 7 (58.3) |

| Klinefelter syndrome | 5 | — | 0 (0) |

| Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome | 4 | — | 2 (50.0) |

| Other chromosomal abnormalities | 75 | — | 30 (40.0) |

| Total | 355 | 20.0 | 218 (61.4) |

| Named syndromes, sequences, and associationsa | 84 | 4.7 | 37 (44.0) |

| Nervous system | |||

| Anencephaly | 27 | — | 27 (100) |

| Meningomyelocele ± hydrocephalus | 17 | — | 5 (29.4) |

| Congenital hydrocephalus | 20 | — | 12 (60.0) |

| Hydranencephaly | 5 | — | 4 (80.0) |

| Holoprosencephaly | 11 | — | 7 (63.6) |

| Myotonic dystrophy/myopathy | 7 | — | 4 (57.1) |

| Spina bifida | 5 | — | 4 (80.0) |

| Other nervous system anomalies | 79 | — | 34 (43.0) |

| Total | 171 | 9.6 | 97 (56.7) |

| Cardiovascularb | |||

| Tetralogy of Fallot ± pulmonary atresia | 38 | — | 16 (42.1) |

| Transposition of great vessels | 19 | — | 7 (36.8) |

| Pulmonary atresia | 9 | — | 4 (44.4) |

| Truncus arteriosus | 6 | — | 3 (50.0) |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous return | 5 | — | 2 (40.0) |

| HLHS | 19 | — | 16 (84.2) |

| Interrupted aortic arch | 7 | — | 1 (14.3) |

| Coarctation of aorta | 23 | — | 7 (30.4) |

| Complete atrioventricular canal | 8 | — | 1 (12.5) |

| Single ventricle | 1 | — | 1 (100) |

| Double outlet right ventricle | 10 | — | 5 (50.0) |

| Tricuspid atresia | 1 | — | 1 (100) |

| Other single cardiovascular anomalies | 132 | — | 27 (20.5) |

| Multiple cardiovascular anomalies | 87 | — | 38 (43.7) |

| Total | 365 | 20.6 | 129 (35.3) |

| Gastrointestinal anomalies | |||

| Esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula | 48 | — | 12 (25.0) |

| Duodenal/jejunal/ileal atresia | 39 | — | 8 (20.5) |

| Atresia of large bowel or rectum | 2 | — | 0 (0) |

| Imperforate anus | 9 | — | 0 (0) |

| Gastroschisis | 44 | — | 16 (36.4) |

| Omphalocele | 22 | — | 11 (50.0) |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 22 | — | 19 (86.4) |

| Other gastrointestinal anomalies | 54 | — | 16 (29.6) |

| Total | 240 | 13.5 | 82 (34.2) |

| Genitourinary | |||

| Bilateral renal agenesis | 43 | — | 43 (100) |

| Bilateral polycystic, multicystic, or dysplastic kidneys | 29 | — | 20 (69.0) |

| Obstructive uropathy with congenital hydronephrosis | 31 | — | 9 (29.0) |

| Exstrophy of the urinary bladder | 3 | — | 1 (33.3) |

| Other genitourinary anomalies | 65 | — | 26 (40.0) |

| Total | 171 | 9.6 | 99 (57.9) |

| Bone and skeletal anomalies | 37 | 2.1 | 19 (51.4) |

| Miscellaneous single system anomaliesc | 77 | 4.3 | 24 (31.2) |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | 38 | 2.1 | 8 (21.1) |

| Other multiple system anomalies | 238 | 13.4 | 165 (69.3) |

| Total | 1776 | 100.0 | 878 (49) |

Named syndromes, sequences, and associations include the following: adducted thumb syndrome (1), amniotic band syndrome (8), Alagille syndrome (1), Apert syndrome (2), Baller-Gerold syndrome (1), Bart syndrome (1), Beals syndrome (1), Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (5), branchiootorenal (BOR) syndrome (1), caudal regression syndrome (2), CHARGE syndrome (2), Cornelia de Lange syndrome (10), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (1), Fanconi syndrome (1), Fryns syndrome (2), Goldenhar syndrome (9), Goltz syndrome (1), Holt-Oram syndrome (1), Hurler syndrome (1), Jarcho Levin syndrome (1), Larsen’s syndrome (1), Meckel-Gruber syndrome (3), Miller-Dieker syndrome (1), Moebius syndrome (1), Nager syndrome (1), Neu-Laxova syndrome (1), Noonan syndrome (2), Opitz syndrome (2), Pena-Shokeir syndrome (4), Peters plus syndrome (1), Pierre Robin syndrome (5), Poland syndrome (1), Roberts syndrome (1), Saethre-Chotzen syndrome (1), Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (1), Stickler syndrome (1), thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR) syndrome (1), Townes-Brocks syndrome (1), Treacher Collins syndrome (1), and Waardenburg syndrome (2).

Thirty-three infants born in 2006–2007 who had an anomaly coded “other congenital heart defects” were counted in the “other single cardiovascular anomalies” category. It was not possible to determine whether a single cardiovascular anomaly was present or multiple cardiovascular anomalies were present because a descriptive text field was not available during these 2 years.

Includes cleft palate (36 infants), congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, and other anomalies.

Percents are shown for each category of birth defects overall. Dashes indicate that percents for individual birth defects within category are not shown.

Mortality

Overall, 7361 (20%) of the 37 262 VLBW infants died before discharge. Substantially more infants with than without a major BD died (49% vs 18%; adjusted RR: 3.66 [95% CI: 3.41–3.92], P < .001), and this relationship was consistent among all but the smallest and most premature infants (Table 4). Respiratory support was withheld or withdrawn between birth and 24 hours for 21% of infants with BDs and 7% of those without BDs, P < .001 (infants born 1998–2005; data not collected 2006–2007). Median age at death was day 3 after birth for infants with a BD who died (25th–75th percentiles: days 1–20). Coded cause of death was congenital malformation for 95% of infants with BDs who died within 12 hours after birth, whereas immaturity was the coded cause for 75% of infants without BDs who died early. Of those who died >12 hours to 7 days after birth, the most frequent cause of death was congenital malformation (80%) for infants with a BD compared with RDS with or without other conditions (52%) for infants without a major BD.

TABLE 4.

Risk of Death for VLBW Infants in the NRN Cohort Born in 1998–2007 With and Without a Major BD

| Infants With BDs, N = 1776 | Infants Without BDs, N = 35 486 | Adjusted RR for Death (95% CI) BD Versus No BDa | P a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | 898 (51) | 29 003 (82) | ||

| Died | 878 (49) | 6483 (18) | 3.66 (3.41–3.92) | <.001 |

| Died ≤ 12 h | 326 (18) | 2401 (7) | 3.83 (3.37–4.36) | <.001 |

| Died ≤ 3 db | 460 (26) | 3421 (10) | 3.77 (3.40–4.19) | <.001 |

| Deaths by BW, g | ||||

| 401–500 | 51 (86) | 1249 (83) | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) | .37 |

| 501–750 | 177 (67) | 3520 (46) | 1.46 (1.33–1.59) | <.001 |

| 751–1000 | 203 (48) | 1102 (14) | 3.48 (3.10–3.90) | <.001 |

| 1001–1250 | 210 (45) | 411 (5) | 9.22 (8.02–10.60) | <.001 |

| 1251–1500 | 237 (42) | 201 (2) | 20.07 (16.94–23.79) | <.001 |

| Deaths by GA, wk | ||||

| <22 | 20 (100) | 354 (99) | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | .59 |

| 22–24 | 114 (77) | 3632 (62) | 1.24 (1.12–1.37) | <.001 |

| 25–28 | 297 (51) | 2127 (14) | 3.39 (3.10–3.70) | <.001 |

| 29–32 | 318 (43) | 343 (3) | 14.07 (12.28–16.11) | <.001 |

| 33+ | 128 (45) | 24 (1) | 35.58 (23.21–54.57) | <.001 |

RRs, CIs, and P values by the Score χ2 test for the overall cohort from modified Poisson regression models that included study center, GA (<22, 22–24, 25–28, 29–32, 33+), SGA, male gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, other), and the BDs indicator. RRs, CIs, and P values by the Wald χ2 for each GA group from a similar model that included effects for the interaction of GA group and the BDs indicator. BW was substituted for GA and SGA in the model examining deaths by BW, which also included effects for the interaction between BW group and the BDs indicator.

Timing of death after 12 h could not be determined for 1 infant with a BD due to missing date of death.

Among VLBW infants with BDs, no significant difference was found in the risk of death for non-Hispanic black infants compared with non-Hispanic white infants (adjusted RR: 1.0 [0.88–1.13], P = .98). However, risk of death was increased for Hispanic compared with non-Hispanic white infants with BDs (adjusted RR: 1.18 [1.03–1.35], P = .02). Over the 10-year period, the proportion of infants with BDs who died each year decreased somewhat (adjusted RR for linear trend: 0.98 [0.96–0.99], P = .01). The mortality rate varied from 56% of those with BDs in 1998 to 49% in 2007, and the change in mortality over time did not differ significantly by racial group (adjusted P = .51).

More than half of infants with chromosomal (61%), nervous system (57%), genitourinary (58%), bone and skeletal (51%), and other multiple system anomalies (69%) died before discharge (Table 3). Death rates varied considerably within category depending on the specific anomaly. For example, 92/102 (90%) VLBW infants with Trisomy 18 died before discharge compared with 38/96 (40%) with Trisomy 21. Among infants with cardiovascular anomalies, deaths rates varied from 12.5% to 100%. Infants with single ventricle physiology had the highest mortality, including 84% mortality among those with HLHS.

In-Hospital Morbidities and Surgeries

Morbidities and major surgeries were reviewed for the 33 380 infants who survived more than 3 days after birth. Infants with BDs were at increased risk for PDA (adjusted RR: 2.01 [95% CI: 1.89–2.13]), RDS, NEC, and LOS compared with those without BDs (Table 5). Rates of PDA, RDS, NEC, and LOS were similar among infants who survived more than 14 days. No significant difference was found in the proportion of infants with BDs who were diagnosed with NEC by type of BD category, P = .63. PDA alone was not counted as a BD (see the Appendix). However, the proportion of infants with PDA varied by type of BD (P < .001) ranging from 29% of those with bone and skeletal anomalies to 58% with a chromosomal anomaly, 59% with a cardiac defect, and 63% with multiple system anomalies. Most infants (94%) had a cranial sonogram within 28 days of birth. The adjusted risk for severe ICH, and for PVL, was increased for infants with BDs.

TABLE 5.

Risk of In-Hospital Morbidities for VLBW Infants in the NRN Cohort Born 1998–2007 With and Without a Major BD Who Survived > 3 Days

| Outcome, N (%)a | Infants With BDs | Infants Without BDs | Adjusted RR for Morbidity (95% CI) BD Versus No BDb | P b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants who survived > 3 d | N = 1315 | N = 32 065 | — | — |

| PDA | 686 (52) | 10 394 (32) | 2.01 (1.89–2.13) | <.001 |

| RDS | 1008 (77) | 24 266 (76) | 1.16 (1.13–1.20) | <.001 |

| NEC | 135 (10) | 2492 (8) | 1.59 (1.35–1.88) | <.001 |

| LOS | 375 (29) | 7609 (24) | 1.53 (1.41–1.67) | <.001 |

| Infants who had a cranial sonogram within 28 dc | N = 1196 | N = 30 094 | — | — |

| Severe ICH | 136 (11) | 3253 (11) | 1.41 (1.20–1.65) | <.001 |

| Infants with a cranial sonogram within 28 d and/or closest to 36 wk PMAd | N = 1220 | N = 30 351 | — | — |

| PVL | 67 (5) | 1163 (4) | 1.71 (1.35–2.17) | <.001 |

| Infants with sufficient information to include in analysise | N = 1194 | N = 30 078 | — | — |

| Severe ICH or PVL | 174 (15) | 3788 (13) | 1.50 (1.30–1.72) | <.001 |

| Infants still in the hospital at 28 d who had a ROP examination | N = 819 | N = 22 414 | — | — |

| ROP | 344 (42) | 10 519 (47) | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | .003 |

| ROP stage 3 or higher | 78 (10) | 2563 (11) | 1.25 (1.02–1.53) | .05 |

| Infants born <36 wk GA who were evaluated for BPDf | N = 1016 | N = 29 241 | — | — |

| BPD | 463 (46) | 8185 (28) | 1.93 (1.79–2.08) | <.001 |

Information was missing for PDA: 9 infants; RDS: 45; NEC: 5; LOS: 32; ICH: 21; PVL: 12; ICH or PVL: 299; ROP: 4; ROP stage 3+: 16; BPD: 135 infants. The majority with missing information were infants with no major BD. One infant with a BD who died with unknown death date was excluded from survivors >3 d.

RRs, CIs, and P values by the Score test from modified Poisson regression models fit to each outcome that included study center, GA (<25, 25–28, 29–32, 33+), SGA, male gender, race (African American, non-African American), and the BD indicator. On rows showing numbers of infants, adjusted RRs and P values are not applicable and are not shown as indicated by dashes.

Severe ICH was defined as grade 3 or 4 and was diagnosed based on the cranial sonogram taken within 28 days of birth with the most severe results.

PVL was determined based on a sonogram taken within 28 days of birth and/or a sonogram taken closest to 36 weeks PMA (specified as after 28 days beginning in 2006).

Percents were based on infants with nonmissing ICH and PVL outcomes, except that a diagnosis of either condition was sufficient to set the outcome to yes. Thus, percents were based on a sonogram taken within 28 days of birth and/or a sonogram taken closest to 36 weeks PMA (specified as after 28 days beginning in 2006).

BPD was defined for infants born <36 weeks’ GA as the need for supplemental oxygen use at 36 weeks PMA. For infants discharged or transferred before 36 weeks PMA, BPD was defined based on oxygen use at 36 weeks if known, or oxygen use at the time of discharge or transfer.

Among the 28 517 (85%) infants still hospitalized at 28 days, 81% had a ROP examination. ROP was diagnosed in 42% of infants with BDs and in 47% of those without, with stage 3 or higher diagnosed in ∼10% in each group. After adjusting for GA and other characteristics, risk for ROP was somewhat increased for infants with BDs. Among 30 257 infants born <36 weeks PMA who survived to 36 weeks and were evaluated, the proportion with BPD was higher among those with BDs (46% vs 28%; adjusted RR: 1.93 [95% CI: 1.79–2.08]).

Excluding surgery for PDA, NEC, and ROP, major surgery was more common in infants who survived >3 days with a BD than in those without (48% vs 13%, P < .001). Among infants who had major surgery, those with BDs were more likely to have multiple procedures. The proportions with 1, 2, and 3+ surgery codes recorded are as follows: BDs: 42%, 28%, 30% vs No BDs: 59%, 19%, 22%; P < .001. Surgery was most common for those with GI anomalies (89%), and multiple system anomalies (64%), and lowest for those with inborn errors of metabolism (22%; Table 6). The percent of infants who underwent surgery varied within each BD category. For example, surgery was performed for 3 of 13 (23%) infants with HLHS who survived >3 days, whereas 16/22 (72%) with coarctation of the aorta had surgery. Most surgical procedures were related to the underlying BDs; however, 32 infants in our cohort had a tracheostomy performed, and 4 infants had peritoneal dialysis.

TABLE 6.

Frequency of Major Surgery by Type of BD Among VLBW Infants in the NRN Cohort Born in 1998–2007 Who Survived > 3 Days

| Category | No. | n (%) Who Had Major Surgery Before Dischargee |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal anomalies | ||

| Trisomy 13 | 13 | 3 (23.1) |

| Trisomy 18 | 49 | 2 (4.1) |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | 87 | 36 (41.4) |

| Turner syndrome | 9 | 2 (22.2) |

| Triploidy | 9 | 1 (11.1) |

| 22q deletion | 12 | 7 (58.3) |

| Klinefelter syndrome | 5 | 1 (20.0) |

| Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome | 4 | 1 (25.0) |

| Other chromosomal abnormalities | 66 | 22 (33.3) |

| Total | 254 | 75 (29.5) |

| Named syndromes, sequences, and associationsa | 65 | 30 (46.2) |

| Nervous system | ||

| Anencephaly | 0 | — |

| Meningomyelocele ± hydrocephalus | 15 | 13 (86.7) |

| Congenital hydrocephalus | 16 | 8 (50.0) |

| Hydranencephaly | 3 | 0 (0) |

| Holoprosencephaly | 7 | 0 (0) |

| Myotonic dystrophy/myopathy | 7 | 3 (42.9) |

| Spina bifida | 1 | 1 (100) |

| Other nervous system anomalies | 63 | 24 (38.1) |

| Total | 112 | 49 (43.8) |

| Cardiovascularb | ||

| Tetralogy of Fallot ± pulmonary atresia | 37 | 15 (40.5) |

| Transposition of great vessels | 15 | 11 (73.3) |

| Pulmonary atresia | 9 | 3 (33.3) |

| Truncus arteriosus | 3 | 0 (0) |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous return | 4 | 1 (25.0) |

| HLHS | 13 | 3 (23.1) |

| Interrupted aortic arch | 7 | 3 (42.9) |

| Coarctation of aorta | 22 | 16 (72.7) |

| Complete atrioventricular canal | 7 | 2 (28.6) |

| Single ventricle | 0 | — |

| Double outlet right ventricle | 10 | 5 (50.0) |

| Tricuspid atresia | 0 | — |

| Other single cardiovascular anomalies | 121 | 34 (28.1) |

| Multiple cardiovascular anomalies | 75 | 38 (50.7) |

| Total | 323 | 131 (40.6) |

| Gastrointestinal anomalies | ||

| Esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula | 42 | 39 (92.9) |

| Duodenal/jejunal/ileal atresia | 39 | 37 (94.9) |

| Atresia of large bowel or rectum | 2 | 2 (100) |

| Imperforate anus | 9 | 8 (88.9) |

| Gastroschisis | 38 | 36 (94.7) |

| Omphalocele | 17 | 13 (76.5) |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 7 | 5 (71.4) |

| Other gastrointestinal anomalies | 51 | 43 (84.3) |

| Total | 205 | 183 (89.3) |

| Genitourinary | ||

| Bilateral renal agenesis | 0 | — |

| Bilateral polycystic, multicystic, or dysplastic kidneys | 15 | 4 (26.7) |

| Obstructive uropathy with congenital hydronephrosis | 29 | 13 (44.8) |

| Exstrophy of the urinary bladder | 2 | 1 (50.0) |

| Other genitourinary anomalies | 51 | 17 (33.3) |

| Total | 97 | 35 (36.1) |

| Bone and skeletal anomalies | 21 | 5 (23.8) |

| Miscellaneous single system anomaliesc | 63 | 27 (42.9) |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | 36 | 8 (22.2) |

| Other multiple system anomalies | 137 | 88 (64.2) |

| Total | 1313d | 631 (48) |

Named syndromes, sequences, and associations among survivors > 3 days include the following: adducted thumb syndrome (1), amniotic band syndrome (6), Alagille syndrome (1), Baller-Gerold syndrome (1), Bart syndrome (1), Beals syndrome (1), Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (3), branchiootorenal (BOR) syndrome (1), caudal regression syndrome (1), CHARGE syndrome (2), Cornelia de Lange syndrome (9), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (1), Fanconi syndrome (1), Fryns syndrome (1), Goldenhar syndrome (9), Goltz syndrome (1), Holt-Oram syndrome (1), Hurler syndrome (1), Jarcho Levin syndrome (1), Larsen syndrome (1), Miller-Dieker syndrome (1), Moebius syndrome (1), Nager syndrome (1), Noonan syndrome (1), Opitz syndrome (2), Pena-Shokeir syndrome (1), Peters plus syndrome (1), Pierre Robin syndrome (5), Poland syndrome (1), Roberts syndrome (1), Saethre-Chotzen syndrome (1), Stickler syndrome (1), thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR) syndrome (1), Townes-Brocks syndrome (1), and Waardenburg syndrome (2).

Thirty-three infants born in 2006–2007 who had an anomaly coded “other congenital heart defects” and survived >3 days were counted in the “other single cardiovascular anomalies” category. It was not possible to determine whether a single cardiovascular anomaly was present or multiple cardiovascular anomalies were present as a descriptive text field was not available during these 2 years.

Includes cleft palate (36 infants), congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, and other anomalies.

Of infants with BDs, 1315 survived >3 days. Surgery information was missing for 2 infants with cardiovascular defects who survived >3 days: 1 infant with transposition of the great vessels and 1 with truncus arteriosus. One infant with a BD who died after 12 hours but for whom more precise timing of death was unknown was not included among survivors >3 days.

Where the number of infants with a specific birth defect is 0, a dash indicates that no percent is shown.

Median time to discharge was 85 days for infants with major BDs (25th–75th percentiles: 58–128 days) compared with 62 days for infants without BDs (25th–75th percentiles: 41–90 days), P < .001.

Discussion

BDs continue to be a leading cause of infant death in the United States.1 In our cohort, VLBW infants with BDs had 3 times the risk of death compared with their peers without BDs. The risk was most exaggerated among those with higher BW for whom neonatal survival rates are typically high. The increased risk for neonatal morbidity, including RDS, BPD, NEC, and severe ICH, likely impacts the overall risk of death in these infants.

In our cohort of over 37 000 VLBW infants, the prevalence of BDs was 4.8%, which is higher than the 3% prevalence reported among all births in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention registry data. Additionally, during the 10-year study period, we found a significant increase in the prevalence of BDs from 4.0% of infants born in 1998 to 5.6% in 2007. Horbar et al16 recently reported a similar increase in rate of BDs in the VON database from 4.3% in 2000 to 5.1% in 2009. This increase may represent ascertainment bias, as rates of overall survival and options for surgical interventions have increased over time for VLBW infants. Although it appears that the pregnancies in our cohort were being actively managed based on the frequency of antenatal steroid use and operative delivery (Table 1), we have no data on whether prenatal diagnosis may have affected pregnancy or neonatal management and outcomes. Trends in increasing maternal age and the frequency of maternal conditions associated with an increased risk of BDs may have also affected changes in prevalence.

Chromosomal and cardiovascular anomalies occurred most frequently in our VLBW cohort, each accounting for 20% of the infants with BDs. The proportion with chromosomal anomalies was also 20% among infants with BDs born at VON centers in 1994 and 1995,10 but the proportion reported with cardiovascular defects was smaller than at NRN sites (11% vs 20.6%). Neonates with BDs are more likely to have a screening echocardiogram, which may contribute to the increased frequency of congenital heart disease seen in these patients. However, these findings are important because only clinically significant defects were included in this analysis and it is unlikely that criteria for screening changed significantly during the study period.

Mortality varied considerably in our cohort depending on type of defect. VLBW infants with Trisomy 13 and Trisomy 18 were likely to die before hospital discharge. Interestingly, in our cohort, 4 infants (12%) with Trisomy 13 and 10 infants (10%) with Trisomy 18 were discharged from the hospital alive. Similarly, Boghossian et al17 reported that 7.6% of infants with Trisomy 13 and 11% with Trisomy 18 at VON centers survived until hospital discharge. Major surgical procedures were performed on 2 neonates with Trisomy 13 who were discharged from the hospital; however, it is unknown if these procedures improved survival after hospital discharge. In contrast, the 2 infants in our cohort with Trisomy 18 who had surgical procedures died before hospital discharge. Although term infants with Trisomy 21 typically survive beyond hospital discharge, 40% of VLBW infants in our cohort with Trisomy 21 died before discharge. In an earlier NRN report, VLBW infants with Trisomy 21 and a congenital heart or gastrointestinal anomaly had nearly twice the risk of death compared with infants with Trisomy 21 who did not have these defects.18

Although mortality rates related to congenital heart defects have trended downward over the past decade, mortality from heart defects is higher among low BW infants.19–21 Cardiovascular defect specific mortality rates in our cohort were variable yet similar to reports in larger cohort studies of VLBW infants, with the highest mortality in those with HLHS, single ventricle, and tricuspid atresia. The majority of infants (84%) with HLHS in our cohort died before hospital discharge. Management of these infants is challenging due to neonatal comorbidities such as BPD, and inability to intervene surgically due to small size. Pappas et al22 reported an increased risk of growth impairment and neurodevelopmental impairment among ELBW survivors with congenital heart defects. It will be important to monitor mortality trends in VLBW infants with congenital heart defects over time and morbidity among survivors.

In our cohort, neural tube defects accounted for 4% of all BDs and 41.5% of those involving the nervous system. Similar to published data,23 the 70% mortality associated with neural tube defects in our cohort was higher than is typical among term infants.

VLBW infants with BDs who survived past 3 days had a more protracted hospitalization and were 3 times more likely to require surgical intervention than VLBW infants without defects. Over time, there has been a shift toward performing surgical procedures on neonates with conditions previously felt to be lethal. Therefore, it is important to examine specific mortality profiles and interventions to better evaluate the risk:benefit ratio in these clinical scenarios. Three (23%) of 13 infants with HLHS who survived more than 3 days had surgery, of whom 2 survived to discharge. It is unclear whether the other infants with HLHS were not considered surgical candidates based on their low BW or whether life-threatening complications developed before reaching an appropriate size to attempt surgical palliation. Seventy-one percent of those with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and 77% of those with an omphalocele underwent surgery before hospital discharge, yet mortality rates remained high. Some surgical options and potentially life-sustaining therapies, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, are not technically feasible in VLBW infants resulting in higher mortality rates than those seen in term neonates with similar conditions.

Although our birth cohort was not population-based, it included all VLBW infants from 22 academic centers across the United States. Data collection for this cohort was based on BW; therefore, our data collection may be incomplete at the extremes of GA. Although we were able to evaluate whether overall prevalence of BDs changed over the study period, our ability to evaluate trends in prevalence of specific BDs was limited by small numbers. We had no data on prenatal diagnosis, intent to treat, or timing of confirmation of diagnosis, each of which may have affected physician attitudes toward provision of intensive and aggressive care and effected in-hospital mortality rates. Information on indication and timing of surgical procedures was limited.

Conclusions

Frequency of a major BD was low among VLBW infants but increased during the 10-year period. Infants with BDs had an increased risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality compared with peers without BDs. As boundaries for the care of extremely premature and VLBW infants with BDs continue to shift to lower GAs, it is important to evaluate morbidity and mortality among affected infants.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

NRN Steering Committee Chair: Michael S. Caplan, MD (University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904): William Oh, MD; Betty R. Vohr, MD; Barbara Alksninis, PNP; Bonnie E. Stephens, MD; Yvette Yatchmink, MD; Robert Burke, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, RN BSN; Teresa M. Leach, MEd CAES; Martha R. Leonard, BA, BS; Lucy Noel; Rachel A. Vogt, MD; Victoria E. Watson, MS CAS; and Suzy Ventura.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80): Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Deanne E. Wilson-Costello, MD; Bonnie S. Siner, RN; and Harriet G. Friedman, MA.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University Hospital, and Good Samaritan Hospital (U10 HD27853, M01 RR8084): Kurt Schibler, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Jean J. Steichen, MD; Kimberly Yolton, PhD; Barbara Alexander, RN; Kate Bridges, MD; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Marcia Worley Mersmann, RN; Holly L. Mincey, RN BSN; Jody Hessling, RN; and Teresa L. Gratton, PA.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, Alamance Regional Medical Center, and Durham Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, M01 RR30): Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; C. Michael Cotten, MD, MHS; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD, FNP-BC, IBCLC; Katherine A. Foy, RN; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; and Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN, MSN.

Emory University, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (U10 HD27851, M01 RR39): David P. Carlton, MD; Sheena Carter, PhD; Elisabeth Dinkins, PNP; Maureen Mulligan LaRossa, RN; and Gloria V. Smikle, PNP MSN.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: Linda L. Wright, MD; Elizabeth M. McClure, MEd; and Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750): Brenda B. Poindexter, MD, MS; James A. Lemons, MD; Anna M. Dusick, MD; Carolyn Lytle, MD, MPH; Lon G. Bohnke, MS; Greg Eaken, PhD; Dianne E. Herron, RN; Lucy C. Miller, RN, BSN, CCRC; Heike M. Minnich, PsyD, HSPP; Leslie Richard, RN; Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN, CCRC; and Faithe Hamer, BS.

RTI International (U10 HD36790): W. Kenneth Poole, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Jamie E. Newman, PhD, MPH; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS; Margaret Cunningham, BS; Betty K. Hastings; Elizabeth M. McClure, MEd; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS; and Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN, BSN.

Stanford University, California Pacific Medical Center, Dominican Hospital, El Camino Hospital, and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27880, M01 RR70): David K. Stevenson, MD; Susan R. Hintz, MD, MS Epi; Marian M. Adams, MD; Charles E. Ahlfors, MD; Joan M. Baran, PhD; Barbara Bentley, PhD; Lori E. Bond, PhD; Ginger K. Brudos, PhD; Alexis S. Davis, MD, MS; Maria Elena DeAnda, PhD; Anne M. DeBattista, RN, PNP; Jan T. Epcar, MA; Barry E. Fleisher, MD; Magdy Ismael, MD, MPH; Jean G. Kohn, MD, MPH; Carol G. Kuelper, PhD; Julie C. Lee-Ancajas, PhD; Melinda S. Proud, RCP; Renee P. Pyle, PhD; Dharshi Sivakumar, MD, MRCP; Robert D. Stebbins, MD; and Nicholas H. St. John, PhD.

Tufts Medical Center, Floating Hospital for Children (U10 HD53119, M01 RR54): Ivan D. Frantz III, MD; Elisabeth C. McGowan, MD; Brenda L. MacKinnon, RNC; Ellen Nylen, RN, BSN; Anne Furey, MPH; Cecelia Sibley, PT, MHA; and Ana Brussa, MS, OTR/L.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32): Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Myriam Peralta-Carcelen, MD, MPH; Kathleen G. Nelson, MD; Kirstin J. Bailey, PhD; Fred J. Biasini, PhD; Stephanie A. Chopko, PhD; Monica V. Collins, RN, BSN, MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN, BSN; Mary Beth Moses, PT, MS, PCS; Vivien A. Phillips, RN, BSN; Julie Preskitt, MSOT, MPH; Richard V. Rector, PhD; and Sally Whitley, MA, OTR-L, FAOTA.

University of California–San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women and Newborns (U10 HD40461): Neil N. Finer, MD; Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD, MPH; Maynard R. Rasmussen, MD; Paul R. Wozniak, MD; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Renee Bridge, RN; Clarence Demetrio, RN; Martha G. Fuller, RN, MSN; Donna Posin, OTR/L, MPA; and Wade Rich, BSHS, RRT.

University of Iowa Children’s Hospital (U10 HD53109, M01 RR59): John A. Widness, MD; Tarah T. Colaizy, MD; Karen J. Johnson, RN, BSN; Diane L. Eastman, RN, CPNP, MA.

University of Miami, Holtz Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21397, M01 RR16587): Charles R. Bauer, MD; Shahnaz Duara, MD; Ruth Everett-Thomas, RN, MSN; Amy Mur Worth, RN, MS; Mary Allison, RN; Alexis N. Diaz, BA; Elaine O. Mathews, RN; Kasey Hamlin-Smith, PhD; Lisa Jean-Gilles, BA; Maria Calejo, MS; Silvia M. Frade Eguaras, BA; Silvia Hiriart-Fajardo, MD; Yamiley C. Gideon, BA; Michelle Berkovits, PhD; Alexandra Stoerger, BA; Andrea Garcia, MA; and Helena Pierre, BA.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (U10 HD27881, U10 HD53089, M01 RR997): Kristi L. Watterberg, MD; Lu-Ann Papile, MD; Robin K. Ohls, MD; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN; Jean R. Lowe, PhD; and Rebecca Montman, BSN.

University of Rochester Medical Center, Golisano Children’s Hospital (U10 HD40521, M01 RR44, UL1 024160): Dale L. Phelps, MD; Ronnie Guillet, MD, PhD; Gary J. Myers, MD; Linda J. Reubens, RN, CCRC; Erica Burnell, RN; Mary Rowan, RN; Cassandra A. Horihan, MS; Julie Babish Johnson, MSW; Diane Hust, MS, RN, CS; Rosemary L. Jensen; Emily Kushner, MA; Joan Merzbach, LMSW; Lauren Zwetsch, RN, MS, PNP; and Kelly Yost, PhD.

University of Tennessee Health Science Center (U10 HD21415): Sheldon B. Korones, MD; Henrietta S. Bada, MD; Tina Hudson, RN, BSN; Marilyn Williams, LCSW; and Kimberly Yolton, PhD.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633): Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; R. Sue Broyles, MD; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Sally S. Adams, PNP; Cathy Twell Boatman, MS CIMI; Jeannette Burchfield, RN, BSN; Cristin Dooley, PhD, LSSP; Alicia Guzman; Elizabeth Heyne, PA-C, PsyD; Jackie F. Hickman, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Linda A. Madden, BSN, RN, CPNP; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Susie Madison, RN; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Diana M. Vasil, RNC, NIC; and Lizette E. Torres, RN.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Medical School, Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District (U10 HD21373): Jon E. Tyson, MD, MPH; Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD, MPH; Esther G. Akpa, RN, BSN; Patty A. Cluff, RN; Beverly Foley Harris, RN, BSN; Claudia I. Franco, RNC, MSN; Anna E. Lis, RN, BSN; Sarah Martin, RN, BSN; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Patti L. Pierce Tate, RCP; Maegan C. Simmons, RN; Patricia W. Evans, MD; Nora I. Alaniz, BS; Pamela J. Bradt, MD, MPH; Magda Cedillo; Susan Dieterich, PhD; Charles Green, PhD; Margarita Jiminez, MD, MPH; Terri Major-Kincade, MD, MPH; Brenda H. Morris, MD; M. Layne Poundstone, RN, BSN; Stacey Reddoch, BA; Saba Siddiki, MD; Laura L. Whitely, MD; and Sharon L. Wright, MT.

University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, and Primary Children’s Medical Center (U10 HD53124, M01 RR64): Roger G. Faix, MD; Bradley A. Yoder, MD; Anna Bodnar, MD; Mike Steffens, PhD; Shawna Baker, RN; Jill Burnett, RN; Jennifer J. Jensen, RN, BSN; Karen A. Osborne, RN, BSN, CCRC; and Kimberlee Weaver-Lewis, RN, BSN.

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Brenner Children’s Hospital, and Forsyth Medical Center (U10 HD40498, M01 RR7122): T. Michael O’Shea, MD, MPH; Robert G. Dillard, MD; Nancy J. Peters, RN, CCRP; Korinne Chiu, MA; Deborah Evans Allred, MA, LPA; Donald J. Goldstein, PhD; Raquel Halfond, MA; Barbara G. Jackson, RN, BSN; Carroll Peterson, MA; Ellen L. Waldrep, MS; Melissa Whalen Morris, MA; and Gail Wiley Hounshell, PhD.

Wayne State University, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385): Yvette R. Johnson, MD, MPH; Athina Pappas, MD; Rebecca Bara, RN, BSN; Debra Driscoll, RN, BSN; Laura Goldston, MA; Deborah Kennedy, RN, BSN; Geraldine Muran, RN, BSN; Elizabeth Billian, RN, MS; Laura Sumner, RN, BSN; Kara Sawaya, RN, BSN; and Kathleen Weingarden, RN, BSN.

Yale University, Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, and Bridgeport Hospital (U10 HD27871, UL1 RR24139, M01 RR125, M01 RR6022): Richard A. Ehrenkranz, MD; Christine Butler, MD; Harris Jacobs, MD; Patricia Cervone, RN; Nancy Close, PhD; Patricia Gettner, RN; Walter Gilliam, PhD; Sheila Greisman, RN; Monica Konstantino, RN, BSN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Elaine Romano, MSN; Janet Taft, RN, BSN; and Joanne Williams, RN, BSN.

Glossary

- BD

birth defect

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- BW

birth weight

- CI

confidence interval

- GA

gestational age

- HLHS

hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- ICH

intracranial hemorrhage

- LOS

late-onset sepsis

- NEC

necrotizing enterocolitis

- NICHD

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- PDA

patent ductus arteriosus

- PMA

postmenstrual age

- PVL

periventricular leukomalacia

- RDS

respiratory distress syndrome

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

- RR

relative risk

- SGA

small for gestational age

- VLBW

very low birth weight

- VON

Vermont Oxford Network

Appendix: Conditions Not Counted as Major BDs for This Analysis

Hydrops fetalis

Oligohydramnios sequence

Pulmonary hypoplasia/ hypoplastic lungs

PDA

Patent foramen ovale

Cardiac conduction defects/myocardial dysfunction

Hemoglobinopathies

Genetic RBC abnormalities (sickle cell disease, thalassemia, +G6PD)

Cystic liver disease

Congenital tumors

Congenital infections

Congenital glaucoma

Isolated microcephaly

In utero cerebrovascular accident

Laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia, and pharyngomalacia

Subglottic stenosis, tracheal stenosis, and bronchial stenosis

Laryngeal web

Meconium plug, meconium ileus, and meconium peritonitis

Toxic megacolon

Cystic fibrosis

Fetal alcohol syndrome

Twin to twin transfusion

Hypothyroidism

Adrenal insufficiency

Panhypopituitarism

Hypospadias

Inguinal hernia

Arthrogryposis

Congenital dislocation of the hips

Club feet

Cleft lip without cleft palate

Syndactyly

Polydactyly

“Congenital malformation,” “termination for congenital anomalies,” “congenital heart,” “dysmorphic features,” “multiple minor malformations” with no other information (5 cases—1 case each)

Footnotes

All authors qualify for authorship based on substantial contribution to the development of this article as outlined. Dr Adams-Chapman contributed to conception and design of the project, drafted the original article and revised the document, performed interpretation of data, and has approved the final article as submitted. Ms Hansen contributed to conception and design of the project, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted data, wrote the statistical analysis section and contributed substantially to writing the first and subsequent drafts of the article, and has approved the final article as submitted. Dr Shankaran contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 2247. Dr Bell contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 213. Dr Boghossian contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Dr Murray contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Dr Laptook contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 2424. Dr Walsh contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final manuscript as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 1771. Dr Carlo contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 3096. Dr Sanchez contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 1973. Dr VanMeurs contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 1607. Dr Das contributed to conception and design of the project, designed data collection instruments, supervised data collection for the Neonatal Research Network (NRN), supervised the statistical analysis, interpreted data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Ms Hale contributed to the conception and design of the project, designed data collection instruments, performed data collection at one site and served as a resource for data collection related activity for the other NRN sites, revised the draft for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Ms Newman contributed to the conception and design of the project, designed data collection instruments, performed data collection at one site and served as a resource for data collection related activity for the other NRN sites, revised the draft for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Ms Ball contributed to the conception and design of the project, designed data collection instruments, performed data collection at one site and served as a resource for data collection related activity for the other NRN sites, revised the draft for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Dr Higgins contributed to and supervised the conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Dr Stoll contributed to conception and design of the project, performed interpretation of data, revised the article for intellectual content, and has approved the final article as submitted. Number of patients enrolled: 2312.

Data collected at participating sites of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network (NRN) were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed, and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, Dr Das (DCC Principal Investigator) and Ms Hansen (DCC Statistician) had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s VLBW registry study. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Kochanek KD, Kirmeyer SE, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):338–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee K, Khoshnood B, Chen L, Wall SN, Cromie WJ, Mittendorf RL. Infant mortality from congenital malformations in the United States, 1970-1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(4):620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen SA, Erickson JD, Reef SE, Ross DS. Teratology: from science to birth defects prevention. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85(1):82–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolan SM, Callaghan WM, Rasmussen SA. Birth defects and preterm birth: overlapping outcomes with a shared strategy for research and prevention. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85(11):874–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Racial differences by gestational age in neonatal deaths attributable to congenital heart defects --- United States, 2003-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(37):1208–1211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honein MA, Kirby RS, Meyer RE, et al. The association between major birth defects and preterm birth. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(2):164–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen SA, Moore CA, Paulozzi LJ, Rhodenhiser EP. Risk for birth defects among premature infants: a population-based study. J Pediatr. 2001;138(5):668–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw GM, Savitz DA, Nelson V, Thorp JM., Jr Role of structural birth defects in preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(2):106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):443–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell MJ. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(5):281–282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33(1):179–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92(4):529–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suresh GK, Horbar JD, Kenny M, Carpenter JH. Major birth defects in very low birth weight infants in the Vermont Oxford Network. J Pediatr. 2001;139(3):366–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Badger GJ, et al. Mortality and neonatal morbidity among infants 501 to 1500 grams from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1019–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boghossian NS, Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Murray JC, Bell EF, Vermont Oxford Network Major chromosomal anomalies among very low birth weight infants in the Vermont Oxford Network. J Pediatr. 2012;160(5):774–780.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boghossian NS, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Survival and morbidity outcomes for very low birth weight infants with Down syndrome. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1132–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilboa SM, Salemi JL, Nembhard WN, Fixler DE, Correa A. Mortality resulting from congenital heart disease among children and adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2254–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Archer JM, Yeager SB, Kenny MJ, Soll RF, Horbar JD. Distribution of and mortality from serious congenital heart disease in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanner K, Sabrine N, Wren C. Cardiovascular malformations among preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/116/6/e833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pappas A, Shankaran S, Hansen NI, et al. Outcome of extremely preterm infants (<1,000 g) with congenital heart defects from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33(8):1415–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bol KA, Collins JS, Kirby RS, National Birth Defects Prevention Network . Survival of infants with neural tube defects in the presence of folic acid fortification. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):803–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]