Abstract

Motivations: The design of RNA sequences folding into predefined secondary structures is a milestone for many synthetic biology and gene therapy studies. Most of the current software uses similar local search strategies (i.e. a random seed is progressively adapted to acquire the desired folding properties) and more importantly do not allow the user to control explicitly the nucleotide distribution such as the GC-content in their sequences. However, the latter is an important criterion for large-scale applications as it could presumably be used to design sequences with better transcription rates and/or structural plasticity.

Results: In this article, we introduce IncaRNAtion, a novel algorithm to design RNA sequences folding into target secondary structures with a predefined nucleotide distribution. IncaRNAtion uses a global sampling approach and weighted sampling techniques. We show that our approach is fast (i.e. running time comparable or better than local search methods), seedless (we remove the bias of the seed in local search heuristics) and successfully generates high-quality sequences (i.e. thermodynamically stable) for any GC-content. To complete this study, we develop a hybrid method combining our global sampling approach with local search strategies. Remarkably, our glocal methodology overcomes both local and global approaches for sampling sequences with a specific GC-content and target structure.

Availability: IncaRNAtion is available at csb.cs.mcgill.ca/incarnation/

Contact: jeromew@cs.mcgill.ca or yann.ponty@lix.polytechnique.fr

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

At the core of the emerging field of synthetic biology resides, our capacity to design and reengineer molecules with target functions. RNA molecules are well tailored for such applications. The ease to synthesize them (they are directly transcribed from DNA) and the broad diversity of catalytic and regulation functions they can perform enable to integrate de novo logic circuits within living cells (Rodrigo et al., 2012) or reprogram existing regulation mechanisms (Chang et al., 2012). Future advances and applications of these techniques in gene-therapy studies will strongly rely on efficient computational methods to design and reengineer RNA molecules.

Most of RNA functions are, at least partially, encoded by the 3D molecular structures, which are themselves primarily determined by the secondary structures. The development of efficient algorithms for designing RNA sequences with predefined secondary structures is thus a milestone to enter the synthetic biology era. RNAinverse pioneered RNA secondary structure design algorithms. It has been developed and distributed with the Vienna RNA package (Hofacker et al., 1994). However, only posterior experimental studies revealed the potential and practical impact of these techniques. Thereby, during the past 6 years, many improvements and variants of RNAinverse have been proposed. Conceptually, almost all of existing algorithms follow the same approach. First a seed sequence is selected, then a local search strategy is used to mutate the seed and find, in its vicinity, a sequence with desired folding properties. Using this strategy, INFO-RNA (Busch and Backofen, 2006), RNA-SSD (Aguirre-Hernández et al., 2007) and NUPACK:Design (Zadeh et al., 2011) significantly improved the performance of RNA secondary structure design algorithms. More recent research studies aimed to include more constraints in the selection criteria. RNAexinv focused on the design of sequences with enhanced thermodynamical and mutational robustness (Avihoo et al., 2011), while Frnakenstein enables to design RNA with multiple target structures (Lyngsø et al., 2012).

We recently introduced with RNA-ensign a novel paradigm for the search strategy of RNA secondary structure design algorithm (Levin et al., 2012). Instead of a local search approach, we proposed a global sampling strategy of the mutational landscape based on the RNAmutants algorithm (Waldispühl et al., 2008). This methodology offered promising performances, but suffered from prohibitive runtime and memory consumption. Following our work, Garcia-Martin et al. (2013) proposed RNAiFOLD, an alternate methodology that uses constraint programming techniques to prune the mutational landscape. While also suffering from prohibitive running times, it is worth noting that this latter algorithm also proposes a seedless approach to the RNA secondary structure design problem.

In this article, we introduce IncaRNAtion, an RNA secondary structure design algorithm that benefits from our recent algorithmic advances (Reinharz et al., 2013) to expand our original RNA-ensign algorithm (Levin et al., 2012). IncaRNAtion addresses previous limitations of RNA-ensign and offers new functionalities. First, while our previous program had a running time complexity of  , IncaRNAtion now runs in linear-time and space complexity, allowing it to demonstrate similar speeds as any local search algorithm. Next, IncaRNAtion is seedless. Unlike RNA-ensign, it does not require a seed sequence to initiate its search. Finally, IncaRNAtion implements a novel algorithm based on weighted sampling techniques (Bodini and Ponty, 2010) that enables us to control, for the first time, explicitly the GC-content of the solution. This functionality is essential because wild-type sequences within living organisms often present medium or low GC-content, presumably to offer better transcription rates and/or structural plasticity. Previous programs do not allow to control this parameter and tend to output sequences having high GC-contents (Lyngsø et al., 2012).

, IncaRNAtion now runs in linear-time and space complexity, allowing it to demonstrate similar speeds as any local search algorithm. Next, IncaRNAtion is seedless. Unlike RNA-ensign, it does not require a seed sequence to initiate its search. Finally, IncaRNAtion implements a novel algorithm based on weighted sampling techniques (Bodini and Ponty, 2010) that enables us to control, for the first time, explicitly the GC-content of the solution. This functionality is essential because wild-type sequences within living organisms often present medium or low GC-content, presumably to offer better transcription rates and/or structural plasticity. Previous programs do not allow to control this parameter and tend to output sequences having high GC-contents (Lyngsø et al., 2012).

We demonstrate the performance of our algorithms on a set of real RNA structures extracted from the RNA STRAND database (Andronescu et al., 2008). To complete this study, we develop a hybrid method combining our global sampling approach with local search strategies such as the one implemented in RNAinverse. Remarkably, our glocal methodology overcomes both local and global approaches for sampling sequences with a specific GC-content and target structure.

2 METHODS

We introduce a probabilistic model for the design of RNA sequences with a specific GC-content and folding into a predefined secondary structure. For the sake of simplicity, we choose to base this proof-of-concept implementation on a simplified free-energy function  , which only considers the contributions of stacked canonical base pairs. We show how a modification of the dynamic programming scheme used in RNAmutants allows for the sampling of good and diverse design candidates, in linear time and space complexities.

, which only considers the contributions of stacked canonical base pairs. We show how a modification of the dynamic programming scheme used in RNAmutants allows for the sampling of good and diverse design candidates, in linear time and space complexities.

2.1 Definitions

A targeted secondary structure  of length n is given as a non-crossing arc-annotated sequence, where

of length n is given as a non-crossing arc-annotated sequence, where  stands for the base-pairing position of position i in

stands for the base-pairing position of position i in  if any (and, reciprocally,

if any (and, reciprocally,  ), or −1 otherwise. In addition, let us denote by

), or −1 otherwise. In addition, let us denote by  the number of occurrences of G and C in an RNA sequence s.

the number of occurrences of G and C in an RNA sequence s.

2.1.1 Simplified energy model

We use a simplified free-energy model, which only includes additive contributions from stacking base pairs. Using individual values from the Turner 2004 model [retrieved from the NNDB (Turner and Mathews, 2010)]. Given a candidate sequence s for a secondary structure  , the free energy of any sequence s of length

, the free energy of any sequence s of length  is given by

is given by

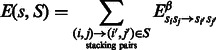

|

where  is set to 0 if

is set to 0 if  (no base pair to stack onto), the tabulated free energy of stacking pairs

(no base pair to stack onto), the tabulated free energy of stacking pairs  in the Turner model if available, or

in the Turner model if available, or  for non–Watson-Crick/Wobble pairs (i.e. not in

for non–Watson-Crick/Wobble pairs (i.e. not in  ). This latter parameter allows one to choose whether to simply penalize invalid base pairs (

). This latter parameter allows one to choose whether to simply penalize invalid base pairs ( ), or forbid them altogether (

), or forbid them altogether ( ). Position-specific sequence constraints can also be enforced at this level (details omitted for the sake of clarity) by assigning to

). Position-specific sequence constraints can also be enforced at this level (details omitted for the sake of clarity) by assigning to  a

a  penalty (leading to a null probability) in the presence of a base incompatible with a user-specified constraint mask.

penalty (leading to a null probability) in the presence of a base incompatible with a user-specified constraint mask.

2.1.2 GC-weighted Boltzmann ensemble and distribution

To counterbalance the documented tendency of sampling methods to generate GC-rich sequences (Levin et al., 2012), we introduce a parameter  , whose value will influence the GC-content of generated sequences. For any secondary structure

, whose value will influence the GC-content of generated sequences. For any secondary structure  , the GC-weighted Boltzmann factor of a sequence s is

, the GC-weighted Boltzmann factor of a sequence s is  such that

such that

| (1) |

where R is the Boltzmann constant and T the temperature in Kelvin.

Summing the GC-weighted Boltzmann factor over all possible sequences of a given length  , one obtains the GC-weighted partition function

, one obtains the GC-weighted partition function  , from which one defines the GC-weighted Boltzmann probability

, from which one defines the GC-weighted Boltzmann probability  of each sequence s, respectively, such that

of each sequence s, respectively, such that

|

(2) |

2.2 Linear-time stochastic sampling algorithm for the GC-weighted Boltzmann ensemble

Let us now describe a linear-time algorithm to sample sequences at random in the GC-weighted Boltzmann distribution. This algorithm follows the general principles of the recursive approach to random generation (Wilf, 1977), pioneered in the context of RNA by the SFold algorithm (Ding and Lawrence, 2003). The algorithm starts by precomputing the partition function restricted to each substructure occurring in the target structure, and then performs a series of recursive stochastic backtracks, using precomputed values to decide on the probability of each alternative.

2.2.1 Precomputing the GC-weighted partition function

Firstly, a dynamic programming algorithm computes  the GC-weighted partition function (the dependency in x is omitted here for the sake of clarity) for a structure

the GC-weighted partition function (the dependency in x is omitted here for the sake of clarity) for a structure  , assuming its (previously chosen) flanking nucleotides are a and b, respectively, either forming a closing base pair (

, assuming its (previously chosen) flanking nucleotides are a and b, respectively, either forming a closing base pair ( ) or not (

) or not ( ). Remark that the empty structure only supports the empty sequence, having energy 0, so one has

). Remark that the empty structure only supports the empty sequence, having energy 0, so one has

| (3) |

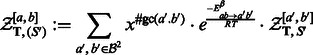

The general recursion scheme consists in three different terms, depending on the first position in  :

:

Case 1 —

First position is unpaired (

):

(4)

Case 2 —

First position is paired with last position [

], stacking onto a preexisting exterior pair (

):

(5)

Case 3 —

First position is involved in a base pair [

], which is not stacking onto an exterior base pair (

or

):

(6) Remark that the number of combinations of a, b and

remains bounded by a constant, thus the complexity of computing

mainly depends on the values taken by

on subsequent recursive calls. Such values are entirely determined by

at any given step of the recursion, and their dependency can be summarized in a tree having

. Therefore, the computation of

requires

time and space using dynamic programming.

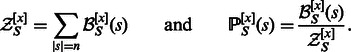

2.2.2 Stochastic backtrack

Once the GC-weighted partition functions have been computed and memorized, a stochastic backtrack starts from the target structure  with any exterior bases

with any exterior bases  and no nesting base pair, corresponding to a call SBx

and no nesting base pair, corresponding to a call SBx

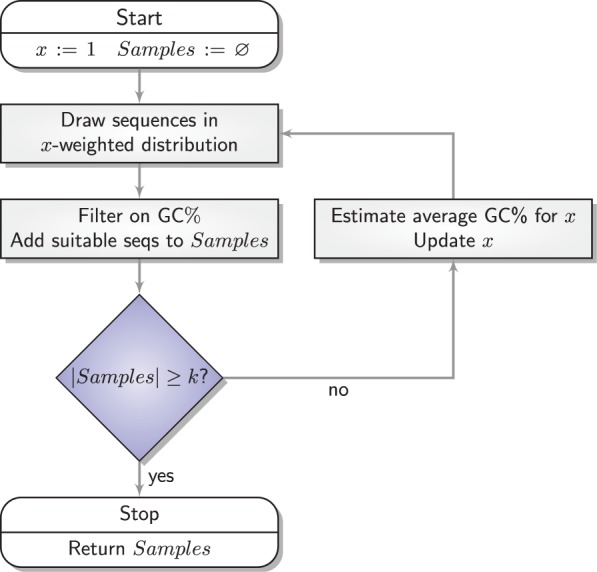

to Algorithm 1. At each step, a suitable assignment for one or several positions is chosen, using probabilities derived from the precomputation, as illustrated by Figure 1. One or several recursive calls over the appropriate substructures are then performed. On each recursive call, the algorithm assigns at least 1 nt to a previously unassigned position. Moreover, the number of executions of each loop is bounded by a constant. Consequently, the complexity of Algorithm 1 is in

to Algorithm 1. At each step, a suitable assignment for one or several positions is chosen, using probabilities derived from the precomputation, as illustrated by Figure 1. One or several recursive calls over the appropriate substructures are then performed. On each recursive call, the algorithm assigns at least 1 nt to a previously unassigned position. Moreover, the number of executions of each loop is bounded by a constant. Consequently, the complexity of Algorithm 1 is in  time and space.

time and space.

Fig. 1.

Stochastic backtrack procedure for a given substructure S. Either the first position is left unpaired (top), a base pair is formed between the two extremities, stacking onto an exterior base pair (middle) or paired without creating a stacking, defining two regions on which subsequent recursive calls are needed (bottom). For the empty structure (omitted here), the empty sequence is returned. Positions indicated in red are assigned at the current stage of the backtrack

2.2.3 Self-adaptive sampling strategy

Let us remind that our goal is to produce a set of sequences whose GC-content matches a prescribed value gc. An absolute tolerance κ may be allowed, so that the GC-content of any valid sequence must fall in  . Because sequences of arbitrary GC-content may be generated by Algorithm 1, we use a rejection-based approach (Bodini and Ponty, 2010), previously adapted by the authors in a similar context (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011). This gives an algorithm that generates k valid sequences in expected time

. Because sequences of arbitrary GC-content may be generated by Algorithm 1, we use a rejection-based approach (Bodini and Ponty, 2010), previously adapted by the authors in a similar context (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011). This gives an algorithm that generates k valid sequences in expected time  when

when  [or

[or  when κ is a positive constant] and memory in

when κ is a positive constant] and memory in  . A complete analysis of the rejection process can be found in an earlier contribution (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011), but let us briefly outline the approach, and the main arguments used to establish its complexity.

. A complete analysis of the rejection process can be found in an earlier contribution (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011), but let us briefly outline the approach, and the main arguments used to establish its complexity.

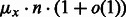

As summarized by Figure 2, our adaptive sampling approach simply generates sets of sequences by repeatedly running the stochastic backtrack algorithm. The average GC-content induced by the current value of the x parameter can then be adequately estimated from the sample, or computed exactly using recent algorithmic advances (Ponty and Saule, 2011). The set of sequences is filtered to only retain valid sequences. The value of the parameter x is then adapted to match the average GC-content (induced by the value of x) with the targeted one. It can be shown that the expected GC-content is a continuous and strictly increasing monotonic function of x, whose limits are 0 when x = 0 and n when  . Consequently, for any targeted GC-content

. Consequently, for any targeted GC-content  , there exists a unique value xgc such that generated sequences feature, on the average, the right GC-content. In practice, a simple binary search (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011) is used in our implementation, and typically converges after few iterations. An optimal value for x can also be derived analytically using interpolation after

, there exists a unique value xgc such that generated sequences feature, on the average, the right GC-content. In practice, a simple binary search (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011) is used in our implementation, and typically converges after few iterations. An optimal value for x can also be derived analytically using interpolation after  evaluations of

evaluations of  for different candidate values of x, as previously noted (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011), and could be implemented using the Fast-Fourier Transform (Senter et al., 2012).

for different candidate values of x, as previously noted (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011), and could be implemented using the Fast-Fourier Transform (Senter et al., 2012).

Fig. 2.

General workflow of our adaptive sampling algorithm (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011)

2.2.4 Overall complexity

It was previously established (Waldispühl and Ponty, 2011) that, for each value of x, there exists constants  and

and  such that the distribution of GC-content asymptotically converges toward a normal law having expectation in

such that the distribution of GC-content asymptotically converges toward a normal law having expectation in  and standard deviation in

and standard deviation in  . Furthermore, the distribution of GC-content is highly concentrated, as asserted by its limited standard deviation; therefore, the expected number of attempts required to generate a valid sequence when

. Furthermore, the distribution of GC-content is highly concentrated, as asserted by its limited standard deviation; therefore, the expected number of attempts required to generate a valid sequence when  [respectively

[respectively  ] grows like

] grows like  [respectively

[respectively  , i.e. a constant], leading to the announced complexities. Formally, because a suitable weight x must be recomputed for each targeted structure and GC-content, then the number M of iterations required for the converge can be accounted for explicitly, leading to time complexities in

, i.e. a constant], leading to the announced complexities. Formally, because a suitable weight x must be recomputed for each targeted structure and GC-content, then the number M of iterations required for the converge can be accounted for explicitly, leading to time complexities in  (if

(if  , i.e. without any tolerance) and

, i.e. without any tolerance) and  (if

(if  ).

).

2.3 Postprocessing unpaired regions: a local/global (glocal) hybrid approach

Owing to our simplified energy model, unpaired regions are not subject to design constraints other than the GC-content, leading to modest probabilities for refolded design candidates to match the targeted structure. To improve these performances and test the complementarity of our global sampling approach with previous contributions based on local search, we used the RNAinverse software to redesign unpaired regions. We specified a constraint mask to prevent stacking base pairs from being modified and, whenever necessary, reestablished their content a posteriori, as RNAinverse has been witnessed to take some liberties with constraint masks. As shown in the Supplementary Material, this postprocessing does not drastically alter the GC-content, so the glocal approach reasonably addresses the constrained GC-content design problem.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Implementation

Our software, IncaRNAtion, was implemented in Python 2.7. We used RNAinverse from the Vienna Package 2.0 (Hofacker et al., 1994). All-time benchmarks were run on a single AMD Opteron(tm) 6278 Processor at 2.4 GHz with cache of 512 kb. The penalty β, associated with invalid base pairs, was set to 15.

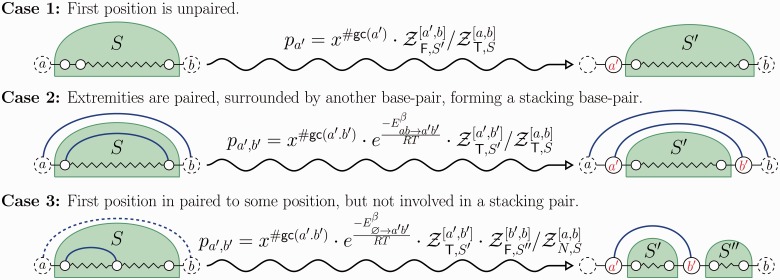

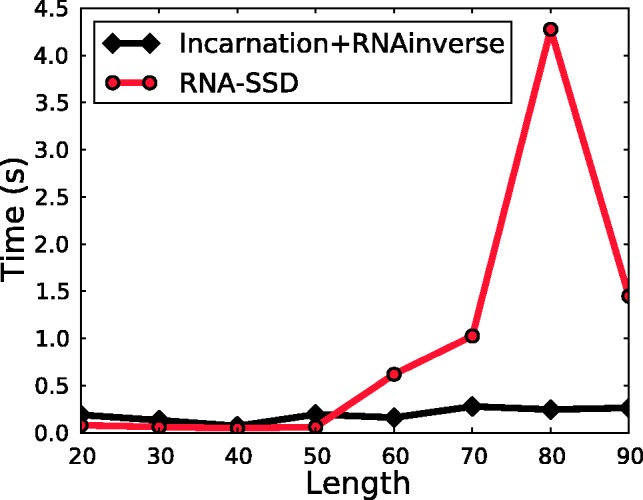

Figure 3 presents the average times spent running IncaRNAtion + RNAinverse to generate one sequence with the required GC-content. As expected, the time grows linearly in function of the length of the structures for IncaRNAtion.

Fig. 3.

Average time in seconds to generate one sequence for IncaRNAtion and RNAinverse

3.2 Dataset

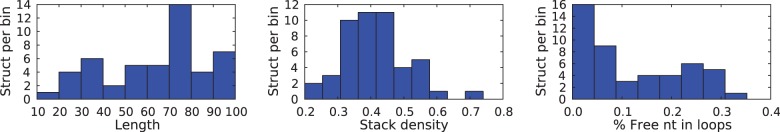

To evaluate the quality of our method, we used secondary structures from the RNA STRAND database (Andronescu et al., 2008). Those are known secondary structures from a variety of organisms. We considered a subset of 50 structures selected by Levin et al. (2012), whose length ranges between 20 and 100 nt. To ease the visualization of results, we clustered together structures having similar length, stacks density and proportion of free nucleotides in loops, leading to distributions of structures shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Number of secondary structures per bin, according to our three clustering criteria

3.3 Design

We ran our method as follows. First, we sampled approximately 100 sequences per structure. Then, we use these sequences as seed in RNAinverse. Finally, we computed the Minimal Free-Energy (MFE) with the RNAfold program from the Vienna Package 2.0 (Hofacker et al., 1994).

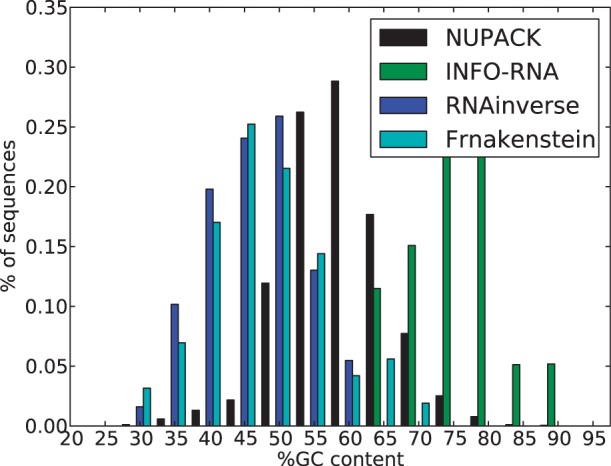

Before starting our benchmark, we asses the need for our methods and performed an analysis of the GC-content drift achieved with state-of-the-art software. Using our dataset of 50 structures, we generated 100 samples per structure with classical softwares that do not control the GC-content. Namely, RNAinverse, INFO-RNA, NUPACK:Design and Frnakenstein. We show the distribution of the GC-content of the sequences produced with these softwares in Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

Overall GC-content distribution for sequences designed using RNAinverse, INFO-RNA, NUPACK:Design and Frnakenstein folding in the desired structure

As anticipated, we observe a clear bias toward high GC-contents and a complete absence of sequence with <30% of GC. This striking result motivates a need for methods that enable to explicitly control the GC-content and more precisely that enable to design sequences with low GC-content (i.e. ≤30%). To provide a complete overview of the performance of IncaRNAtion, we provide additional statistics for these softwares in the Supplementary Material.

3.4 Success rate

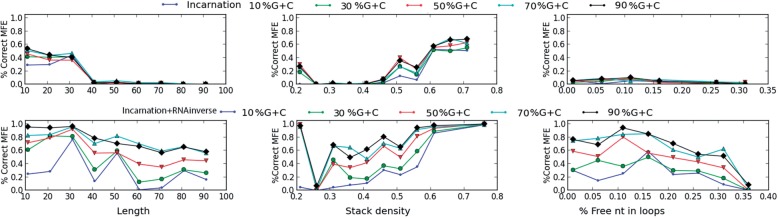

We started by estimating the success rate of our methodology and computed the percentage of sequences with a MFE structure identical to the target secondary structure. Figure 6 shows our results. We clearly see that before the postprocessing step (i.e. RNAinverse) the sequences sampled by IncaRNAtion have a low success rate (first row). As mentioned earlier, this could be explained by the fact that no selection criterion has been at this stage applied to unpaired nucleotides. Remarkably, after the local search optimization (with RNAinverse) of nucleotides in unpaired regions (second row), we observe a dramatic improvement of our success rate. As expected, we observed that length is, in general, not a good predictor for the hardness of designing a structure. Instead, a high number of free nucleotides in the structure seems to be a good measure of the hardness of its design. Similarly, these data also show that designing sequences with low GC-content is challenging for all types of targets.

Fig. 6.

Success rate IncaRNAtion before and after RNAinverse postprocessing. The first row shows the percentage of sampled sequences folding into the target when using only IncaRNAtion. The second shows after processing previous results with RNAinverse

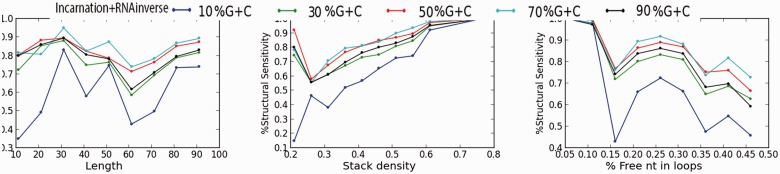

We investigated further the quality of the sequences generated by IncaRNAtion. In particular, we estimated the capacity of our methods to generate ‘good’ sequences with desired folding capabilities regardless of the property to fold exactly into the target structure. In Figure 7, we show the ratio of well-predicted base pairs in the MFE structure of our sampled sequences. As above, we can observe that, in all cases, the sequences that are the hardest to design are those with an extremely low GC-content. Indeed, the energetic contribution of the base pairs to the stability of the structure is weaker. Interestingly, we also notice that the most accurate sequences yield a GC-content of  . Overall, we observe that all our samples have good folding properties, and that there is a correlation between the ‘precision’ of the samples and the hardness of the design.

. Overall, we observe that all our samples have good folding properties, and that there is a correlation between the ‘precision’ of the samples and the hardness of the design.

Fig. 7.

Structural sensitivity (i.e. number of well predicted base pairs/number of base pairs in target) of the sampled sequences MFE

We noticed a highly decreased structural sensitivity for the sequences with 15% free nucleotides in the loops. However, one must remain careful interpreting this observation, as the structures within this class all originate from the PDB, and are relatively small (for the complete STRAND DB, the average length is  nt, compared with

nt, compared with  nt around 15% unpaired bases).

nt around 15% unpaired bases).

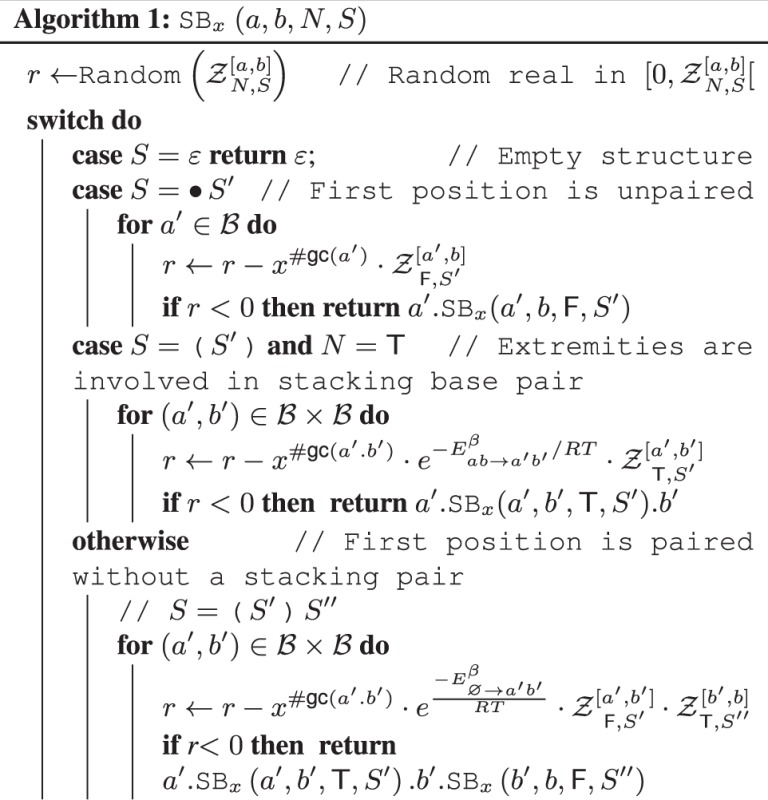

3.5 Properties of designed sequences

In this section, we further analyze the generated sequences with a MFE structure that folds into the target structure.

A desirable feature in sequence design is to produce samples with a high sequence diversity and stable secondary structure. Therefore, in the following, we will use two useful measures, which are the sequence identity of the samples, and the Boltzmann probability of the target structure in the low-energy ensemble.

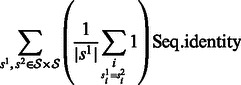

The sequence identity is defined over a set  of aligned sequences (in our case, all sequences have the same length and can be trivially aligned) as follows:

of aligned sequences (in our case, all sequences have the same length and can be trivially aligned) as follows:

|

(7) |

where si is the nucleotide at position i in sequence s. Intuitively, this measure captures the diversity of sequences generated by a given method. Next, the Boltzmann frequency is defined for a structure  and a sequence s as follows:

and a sequence s as follows:

| (8) |

where  is the partition function of sequence s. This measure tells us how dominant is a structure

is the partition function of sequence s. This measure tells us how dominant is a structure  in the Boltzmann ensemble of structures over a sequence s. A high value implies a stable structure. We compute this frequency with RNAfold from the Vienna Package 2.0 (Hofacker et al., 1994).

in the Boltzmann ensemble of structures over a sequence s. A high value implies a stable structure. We compute this frequency with RNAfold from the Vienna Package 2.0 (Hofacker et al., 1994).

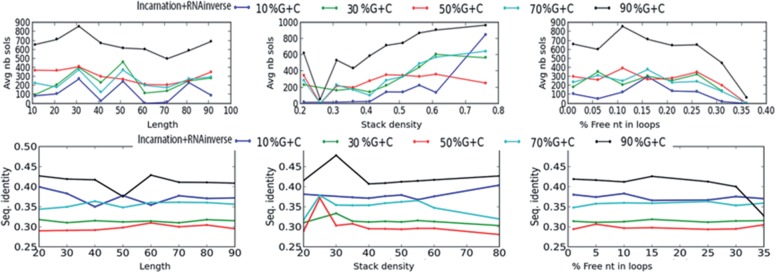

Figure 8 shows the number of solutions generated (i.e. sequences with a MFE structure identical to the target structure). Here, we note that low GC-contents have a strong (negative) influence on the number of sequences generated, and in parallel also affect negatively the sequence diversity. This observation emphasizes the difficulty to design sequences with low GC-content. Once again, large percentages of free nucleotides increase the difficulty of the task.

Fig. 8.

Number of solutions generated with IncaRNAtion + RNAinverse on the first row and their average sequence identity on the second

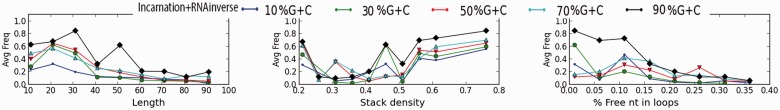

The thermodynamical stability of the target structure on the designed sequence is another important property when estimating the performance of RNA design algorithms. We estimate the quality of our solutions in Figure 9. First, we observe a slow decline of the structure stability (i.e. the frequency) when the target structure increases in size. Yet, for an average GC-content, the frequency stays >10% even at size of 100 nt. Next, we note that for the most difficult target structures (i.e. the longer ones or those with high percentages of unpaired nucleotides in loops) the GC-content has a limited (almost null) influence on the stability of the target structure on the designed sequence. By contrast, this is less true for easiest and small structures with only few free nucleotides in internal loops.

Fig. 9.

Thermodynamical stability of the target structure. The curves report the average Boltzmann probability of the target structure (which is also the MFE structure) at various GC-contents with respect to the length of the target (left), density of stacked base pairs (centre) and number of unpaired nucleotides in loops (right)

3.6 Global sampling versus Local search versus Glocal approach

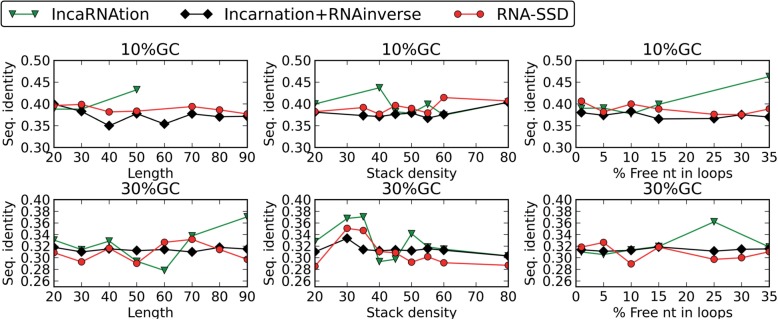

To conclude this study, we estimate the impact of the design methodology on the performances. More precisely, we aim to determine the merits of a global sampling approach (IncaRNAtion), compared with a glocal procedure (IncaRNAtion + RNAinverse) and a local search methodology (RNA-SSD). To the best of our knowledge, RNA-SSD, beside IncaRNAtion, is the only software that implements an explicit control of the GC-content.

Here, we compare the running time and the sequence diversity of the solutions produced by each software. In addition, we focus on the design of sequences with low GC-contents (≤30%) as they are almost impossible to design with classical software (Figure 5).

Figure 3 shows the running time of each software. These data demonstrate the efficiency and scalability of our techniques. In particular, this figure suggests that our strategy has the potential to be applied efficiently for designing sequences on long (and difficult) target secondary structures at low GC-content—a task that could have not been achieved before due time requirements.

Next, we show in Figure 10 the average sequence identity achieved by the various methods. Our results show that at extremely low GC-contents (i.e. 10%), IncaRNAtion slightly outperforms RNA-SSD, while this advantage becomes less evident when the GC-content increases. Our experiments on higher GC-contents (i.e. ≥50%) showed that our glocal strategy and the local search approach perform similarly. Similarly, we did not find any clear evidence that a global, local or glocal approach outperforms others when we compare at the thermodynamical stability of the target structure (data not shown).

Fig. 10.

Sequence identity of IncaRNAtion and RNAinverse for 10 and 30% of GC

4 CONCLUSION

In this article, we described a novel algorithm, IncaRNAtion, for the RNA secondary structure design problem, i.e. the design of an RNA sequence adopting a predefined secondary structure as its minimal free-energy fold. Implementing a global sampling approach, it optimizes affinity toward the target secondary structure, while granting the user full control over the GC-content of the resulting sequences. This extended control does not necessarily induce additional computational demands, and we showed the linear complexity of both the preprocessing stage and the generation of candidate sequences for the design, allowing for the design of larger and more complex secondary structures in a matter of minutes on a single processor (e.g. ∼28 min for 100 candidate sequences for a ∼1500 nt 16S rRNA). We evaluated the method on a benchmark composed of target secondary structures extracted from the RNA STRAND database. We observed good overall success rate, with the notable exception of very low targeted GC-content (10%), and a good to excellent entropy within designed candidates. Finally, we implemented a hybrid approach, using the RNAinverse software as a postprocessing step for unpaired regions. This approach greatly increased the success rate of the method, allowing for the design of highly diverse candidates for almost all of the structures in our benchmark, while largely preserving the targeted GC-content.

In the future, we would like to complement this study by further investigating the potential of hybrid local/global—or glocal—approaches. A global sampling approach would capture the positive aspects of design, optimizing affinity toward a given structure while allowing the specification of expressive systems of constraints. Designed sequences would serve as a seed for a restricted local approach which, by breaking unwanted symmetries, would perform the negative part of the design, while ideally maintaining obedience to the constraints. Another perspective of this work is the incorporation of the full Turner energy model, which should in principle yield better designs for unpaired regions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Rob Knight for his suggestions and comments.

Funding: This work was funded by the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) through the [check] Magnum ANR 2010 BLAN 0204 project (to Y.P.), the FQRNT team grant 232983 (to V.R. and J.W.) and NSERC Discovery grant 219671 (to J.W.). This article has been developed as a result of a mobility stay funded by the Erasmus Mundus Programme of the European Commission under the Transatlantic Partnership for Excellence in Engineering TEE Project (V.R.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Aguirre-Hernández R, et al. Computational RNA secondary structure design: empirical complexity and improved methods. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu M, et al. RNA STRAND: the RNA secondary structure and statistical analysis database. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:340. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avihoo A, et al. RNAexinv: an extended inverse RNA folding from shape and physical attributes to sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:319. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodini O, Ponty Y. 2010. Multi-dimensional Boltzmann Sampling of Languages. In DMTCS Proceedings, number 01 in AM, Vienne, Autriche, pp 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Busch A, Backofen R. INFO-RNA–a fast approach to inverse RNA folding. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1823–1831. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AL, et al. Synthetic RNA switches as a tool for temporal and spatial control over gene expression. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012;23:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Lawrence E. A statistical sampling algorithm for RNA secondary structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:7280–7301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martin JA, et al. RNAiFold: a constraint programming algorithm for RNA inverse folding and molecular design. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2013;11:1350001. doi: 10.1142/S0219720013500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker IL, et al. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatsh. Chem. 1994;125:167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Levin A, et al. A global sampling approach to designing and reengineering rna secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10041–10052. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngsø RB, et al. Frnakenstein: multiple target inverse RNA folding. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponty Y, Saule C. 2011. A Combinatorial Framework for Designing (Pseudoknotted) RNA Algorithms. In: WABI - 11th Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics—2011, Saarbrucken, Allemagne. [Google Scholar]

- Reinharz V, et al. 2013. A linear inside-outside algorithm for correcting sequencing errors in structured RNA sequences. In: Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 7821. Springer, pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo G, et al. De novo automated design of small RNA circuits for engineering synthetic riboregulation in living cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15271–15276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203831109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senter E, et al. Using the fast fourier transform to accelerate the computational search for RNA conformational switches. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DH, Mathews DH. NNDB: the nearest neighbor parameter database for predicting stability of nucleic acid secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D280–D282. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldispühl J, Ponty Y. An unbiased adaptive sampling algorithm for the exploration of RNA mutational landscapes under evolutionary pressure. J. Comput. Biol. 2011;18:1465–1479. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2011.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldispühl J, et al. Efficient Algorithms for probing the RNA mutation landscape. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilf HS. A unified setting for sequencing, ranking, and selection algorithms for combinatorial objects. Adv. Math. 1977;24:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh JN, et al. Nucleic acid sequence design via efficient ensemble defect optimization. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:439–452. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.