Abstract

Background and Objectives

The macrophage is an important early cellular marker related to risk of future rupture of atherosclerotic plaques. Two-channel two-photon luminescence (TPL) microscopy combined with optical coherence tomography (OCT) was used to detect, and further characterize the distribution of aorta-based macrophages using plasmonic gold nanorose as an imaging contrast agent.

Study Design/Materials and Methods

Nanorose uptake by macrophages was identified by TPL microscopy in macrophage cell culture. Ex vivo aorta segments (8 × 8 × 2 mm3) rich in macrophages from a rabbit model of aorta inflammation were imaged by TPL microscopy in combination with OCT. Aorta histological sections (5 µm in thickness) were also imaged by TPL microscopy.

Results

Merged two-channel TPL images showed the lateral and depth distribution of nanorose-loaded macrophages (confirmed by RAM-11 stain) and other aorta components (e.g., elastin fiber and lipid droplet), suggesting that nanorose-loaded macrophages are diffusively distributed and mostly detected superficially within 20 µm from the luminal surface of the aorta. Moreover, OCT images depicted detailed surface structure of the diseased aorta.

Conclusions

Results suggest that TPL microscopy combined with OCT can simultaneously reveal macrophage distribution with respect to aorta surface structure, which has the potential to detect vulnerable plaques and monitor plaque-based macrophages overtime during cardiovascular interventions.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, macrophage, nanorose, two-photon luminescence microscopy, optical coherence tomography, photothermal wave imaging

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis and plaque rupture leading to myocardial infarction, stroke, and progression of peripheral artery disease remain the leading cause of death worldwide, far surpassing both infectious diseases and cancer [1]. Many investigators once believed that progressive luminal narrowing or stenosis beginning from increased lipid storage and continued growth of smooth-muscle cells in the plaque was the main cause of myocardial infarction [2]. Angiographic studies have, however, identified that culprit lesions do not arise from critical stenosis. Previous work by Ambrose et al., Little et al., Nobuyoshi et al., and Giroud et al. demonstrated that nearly two thirds of myocardial infarctions occur in lesions that showed only moderate stenosis [3–8]. Recent advances in basic and experimental science have established a fundamental role that inflammation and underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms [9–11] contribute to atherogenesis from initiation through progression, plaque rupture, and ultimately, thrombosis. The principal pathologic features of atherosclerotic plaques that are prone to rupture are now well-described [12]. Accumulations of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques over-express matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), such as MMP-1 (collagenase-1), MMP-3 (stromelysin-1), and MMP-9 (gelatinase-B) [13–16]. Over-expression of such matrix-degrading enzymes is believed to contribute to plaque instability and thrombogenicity [17–19]. Thus, the macrophage is an important early cellular marker that indicates and contributes to increased risk of plaque remodeling and subsequent rupture in the coronary, cerebral, and peripheral circulations. Since plaque instability is related to cellular composition as well as anatomical structure, developing a diagnostic method that can simultaneously reveal both is critical to identify vulnerable plaques and would allow in vivo monitoring of macrophage density in longitudinal studies in response to cardiovascular interventions.

Currently, X-ray angiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), computed tomography (CT), single-photon emission CT (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET) have been utilized to image atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (e.g., atherosclerotic plaques in the arterial wall) [20,21]. MRI can achieve molecular imaging using contrast agents [22,23]. IVUS can perform virtual histology using spectral analysis to identify plaque components [24,25]. CT and PET/CT using contrast agents can image macrophage infiltration into arterial wall with improved sensitivity [26,27]. SPECT/CT can track monocytes recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques in vivo [28]. However, none of these techniques is able to provide cellular or subcellular resolution. Two-photon luminescence (TPL) microscopy uses nonlinear optical properties of tissue and has been recently utilized to image plaque components such as endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells [29], elastin fibers [30,31], oxidized LDL [32] and lipid droplets [33] based on their endogenous autofluorescence. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been demonstrated to visualize microstructural features such as fibrous cap and surface structure of atherosclerotic plaques with high resolution [34–37]. Due to poor scattering and weak two-photon absorption contrast between macrophages and other plaque components, OCT or TPL microscopy alone, is not able to detect macrophages with high specificity while depicting detailed plaque structures.

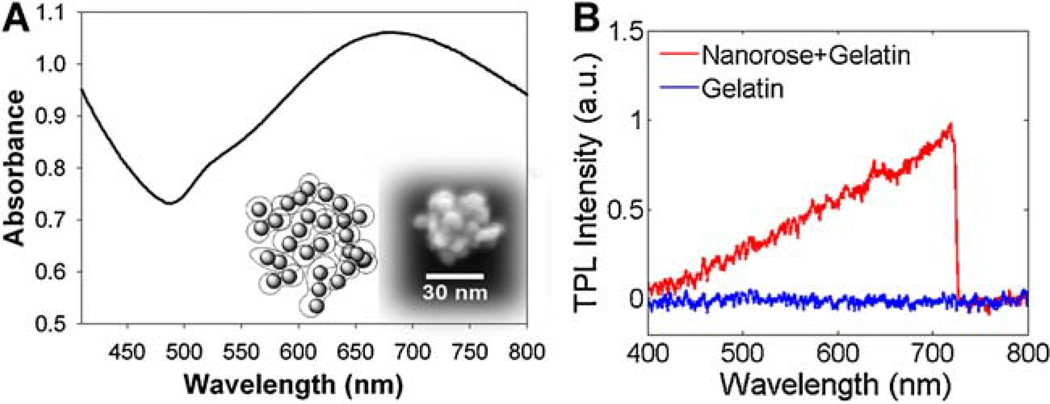

To solve this problem, a novel gold nanoparticle called nanorose [38] was used as an imaging contrast agent for TPL microscopy to target macrophages. The 30 nm diameter nanorose is characterized by the assembly of thin gold shell (1–2.5 nm in thickness) coated iron oxide (5 nm in diameter) nanoparticles. Dextran-coated nanoroses were injected intravenously and engulfed by aorta-based macrophages or blood-based monocytes [39]. Broad near infrared (650–800 nm) absorption of nanorose is achieved by the asymmetric core-shell geometry and plasmonic effects arising from close spacing between primary particles in the cluster (Fig. 1A). Nanorose specificity is achieved since endogenous fluorescence emission (in response to 800 nm two-photon excitation) of collagen, elastin fibers, oxidized-LDL, calcification, and lipid are all below 650 nm [32,33,40] while TPL emission of nanorose is broad and emission intensity increases beyond this wavelength (Fig. 1B). Two emission channels (<570 nm and 700/75 nm) were selected to separate nanorose-loaded macrophages and other aorta components in TPL microscopy.

Fig. 1.

A: Absorbance spectrum of nanorose colloidal suspension. Inset shows a schematic cartoon (left) and scanning electron microscopy image (right) of a single nanorose cluster. B: TPL emission spectra of nanorose in gelatin (red) and gelatin alone (blue) at an excitation wavelength of 800 nm. Nanorose suspension (3.3 × 1011 nanoroses/ml) was mixed with 8% (wt/wt) gelatin to make a nanorose-gelatin tissue phantom (1.99 × 1011 nanoroses/ml). A shortpass filter (<750 nm) was placed in front of the spectrometer detector in order to block the laser line.

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that TPL microscopy in combination with OCT using nanorose as a contrast agent can identify aorta-based macrophages in the context of aorta surface structure in a double balloon injured hypercholesterolemic rabbit model. Presence of nanorose-loaded macrophages was confirmed by co-localization of TPL microscopy of nanorose and RAM-11 staining of macrophages in aorta histological sections. This combined imaging approach can simultaneously reveal cellular composition and anatomical structure of the aorta and has the potential to assess macrophage distribution over time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of Imaging Contrast Agent (Nanorose)

Details of nanorose synthesis were described previously [38]. Briefly, iron oxide nanoparticles were first synthesized using a method modified from Shen et al. [41]. NH4OH (4 ml; >25% wt/wt) was used to titrate 15 ml of a dextran aqueous solution (15% wt/wt) to pH 11.7. To this, 5 ml of freshly prepared 0.75 g of FeCl3 6H2O and 0.32 g of FeCl24H2O aqueous solution was injected dropwise after passing through a hydrophilic 0.2 µm filter. The suspension immediately turned black and was stirred for 0.5 hours. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 9 min to remove aggregates. The supernatant was decanted and dialyzed (Spectra/Pro 7, Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA) against DI water for 24 hours. To concentrate dispersions, a centrifugal filter device (Ultracel YM-30, Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used with a relative centrifugal force of 1,500g. To synthesize the gold-coated iron oxide clusters, 0.1 ml (14.6 mg Fe/ml) of dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles was dispersed in 8.9 ml of DI water, along with 100 µl of 1% hydroxylamine seeding agent was added and 0.5 g of dextrose. The solution pH was adjusted to 9.0 using 20 µl of 7% NH4OH solution. HAuCl4 aqueous solution (6.348 mM) was added in aliquots of 100 µl to the stirred dispersion. A total of four injections were added with 10 min between each injection. The gold-coated iron oxide nanoclusters were separated from iron oxide only clusters by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 6 min. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet was redispersed in 0.1 ml 10% dextran solution and 0.01 ml of a 5% polyvinyl alcohol solution to form a nanorose suspension.

Preparation of Macrophage Cell Culture and Rabbit Arterial Tissues

Macrophage cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). To load nanorose in cells, macrophages were incubated with nanorose suspension (3 × 1010 nanoroses/ml) in DMEM overnight and then mixed with 6% gelatin (wt/wt). Nanorose-loaded macrophages (2.97 × 106 cells/ml) and control macrophages without nanorose (2.59 × 106 cells/ml) were imaged by TPL microscopy with 800 nm excitation and TPL from macrophages was detected in two channels (red channel: bandpass (700/75 nm), green channel: shortpass (<570 nm)).

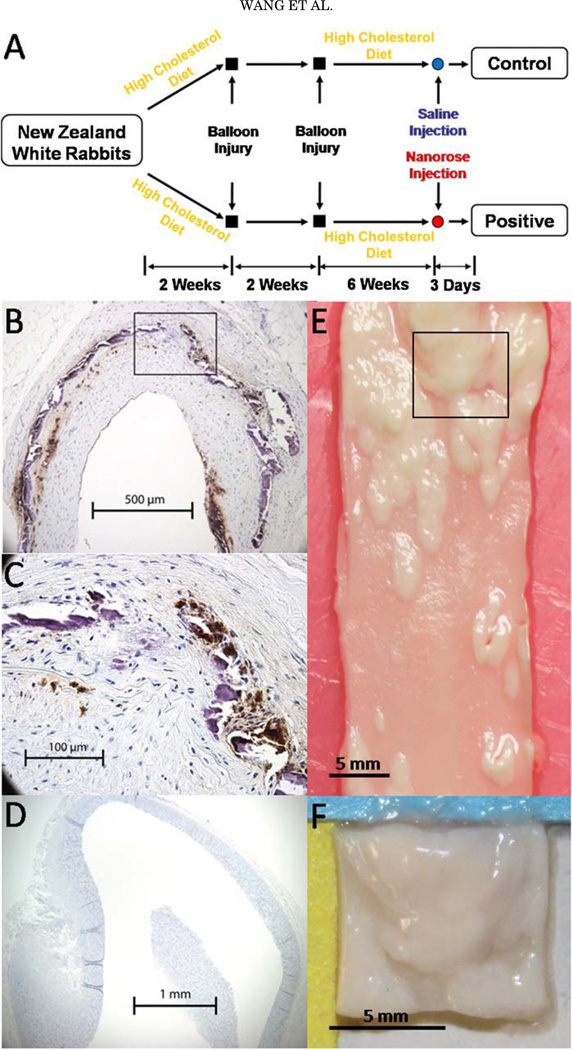

Abdominal aortas were collected from two male double balloon injured and fat fed New Zealand white rabbits: nanorose-(Positive) and saline-injected (Control) rabbits (Fig. 2A). Briefly, following a 2-week 0.25% cholesterol chow diet, the abdominal aorta was balloon injured twice and became rich in intimal hyperplasia and macrophages, while the thoracic aorta was not balloon injured and had little intimal hyperplasia and few macrophages (Fig. 2B – D). The rabbits were continuously fat fed for 6 weeks and intravenously injected with nanorose (1.4 mg Au/kg rabbit body weight) and saline, respectively, 3 days before sacrifice. Ex vivo abdominal aorta with macrophages were harvested, flushed clean of red blood cells and cut into aorta segments (8×8×2 mm3 ) positioned en face onto glass slides with the luminal side face-up for imaging as shown in Figure 2E,F. The aorta segments were first imaged by OCT, then pre-screened by photothermal wave (PTW) imaging [42] to identify ‘‘hot spots’’ where high concentration of nanoroses are located, and finally the hot spots were imaged by TPL microscopy with 800 nm excitation. All imaging experiments were completed within 12 hours after animal sacrifice. The animal protocol was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio IACUC.

Fig. 2.

A: Rabbit model of aorta inflammation with intimal hyperplasia. B: RAM-11 staining of a cross-section of abdominal aorta. C: Amplified view of the black box in (B). Brown color indicates macrophages. D: RAM-11 staining of a cross-section of thoracic aorta. E: A piece of abdominal aorta with intimal hyperplasia. F: An aorta segment (8×8×2 mm) cut from the black box in (E).

Experimental Setup

TPL microscopy

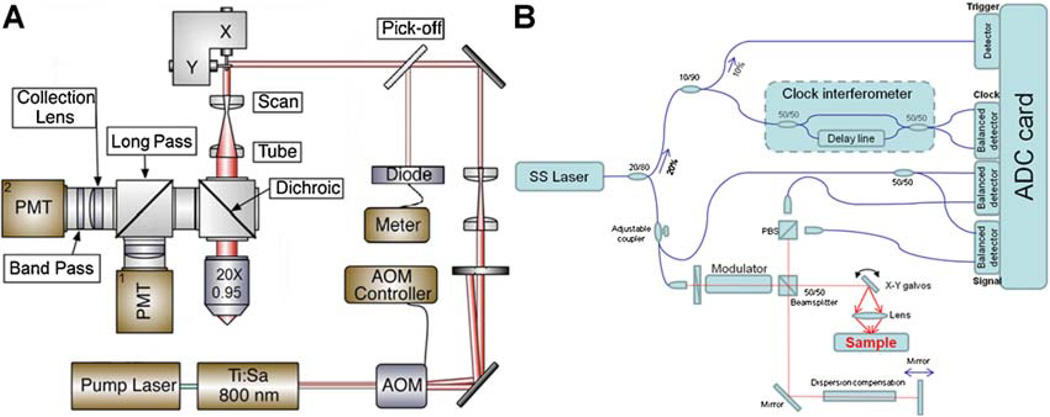

TPL from nanorose was measured using a custom-built NIR laser scanning multiphoton microscope escribed previously (Fig. 3A) [43]. A femtosecond Ti:Sapphire laser (Mira 900, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) emitting at 800 nm (76 MHz, 300 fsecond) was used as an excitation light source. Intensity of the laser beam entering the microscope was modulated by an acousto-optic modulator (23080-1, NEOS Technologies, Melbourne, FL) and monitored by a pick-off mirror (reflectance 1%) with a photodiode calibrated for measuring the power delivered to the objective’s back aperture. The focal volume of the objective lens (20×, NA = 0.95, water emersion, Olympus, Center Valley, PA) was scanned over the sample in the x–y plane using a pair of galvanometric scanning mirrors (6215HB, Cambridge Technology, Lexington, MA) to produce 2D images. TPL from the aorta segment was directed into two channels and detected by two photomultiplier tubes (PMT1: H7422P-40, PMT2: H7422P-50, Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka, Japan). To separate endogenous aorta fluorescence from nanorose luminescence, aorta fluorescence with emission wavelengths shorter than 570 nm were reflected by a long-pass filter (E570LP, Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT) and collected by PMT1 (green channel), while nanorose luminescence with emission wavelengths longer than 570 nm transmitted through a band-pass filter (HQ700/75m, Chroma Technology) and was collected by PMT2 (red channel). The laser power applied at cell culture and arterial tissue (ex vivo aorta segment and histological section) was 15 and 20 mW, respectively. No nanorose damage or photo-bleaching effect was observed during imaging.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagrams of (A) TPL microscopy and (B) intensity OCT system. PMT, photomultiplier tube; AOM, acousto-optic modulator; SS, swept source.

OCT

A swept source (SS) laser (HSL-1000, Santec, Hackensack, NJ) with a center wavelength of 1,060 nm and a bandwidth of 80 nm scanning at a repetition rate of 34 kHz was used in the custom-built intensity OCT system (Fig. 3B). Average power incident on the sample arm was 1.2 mW. The measured free-space axial resolution was 20 µm with a 2.8 mm scan depth. The OCT signal was sampled with a linear k-space sampling clock to allow real-time OCT image acquisition and display. The linear k-space clock was generated by splitting a portion of the source light into a Mach-Zehnder interferometer and into a balanced detector. The clock signal was filtered, frequency-quadrupled and used as the input to the external clock port of the ADC card. The laser sweep rate governs the A-scan rate of 34 kHz and images were acquired at a rate of 68 B-scans per second with 500 A-scans per B-scan.

PTW imaging system

A semiconductor laser (FCTS/ B, Opto Power, Tucson, AZ) that emits at a wavelength of 800 nm with output power of 0.25 W was used to irradiate rabbit arterial and liver tissues to induce photothermal waves from nanorose. A 50 mm diameter lens (f = 40 cm) was used to focus the laser beam to a 1 cm diameter spot on the tissue samples. A mechanical shutter intensity-modulated continuous laser light at a fixed frequency of 4 Hz with a 50% duty cycle. The IR signal (radiometric temperature) emitted from the tissue surface was reflected by a dichroic mirror and recorded by an IR camera (ThermoVision SC6000 with an InSb detector (3.0–5.0 µm), FLIR, Boston, MA) over a 20 second time period at a frame acquisition rate of 25.6 Hz. The extraction of amplitude PTW images (256 × 320 pixels) at 4 Hz was performed by computing a fast Fourier transform (FFT) at each pixel of the recorded temporal IR image sequence.

Histology Analysis

Aorta sections (5 µm in thickness) were immersion-fixed in formalin, processed with paraffin embedding and stained with RAM-11 [44], a marker of rabbit macrophage cytoplasm.

RESULTS

TPL Microscopy of Nanorose-Loaded Macrophages in Cell Culture

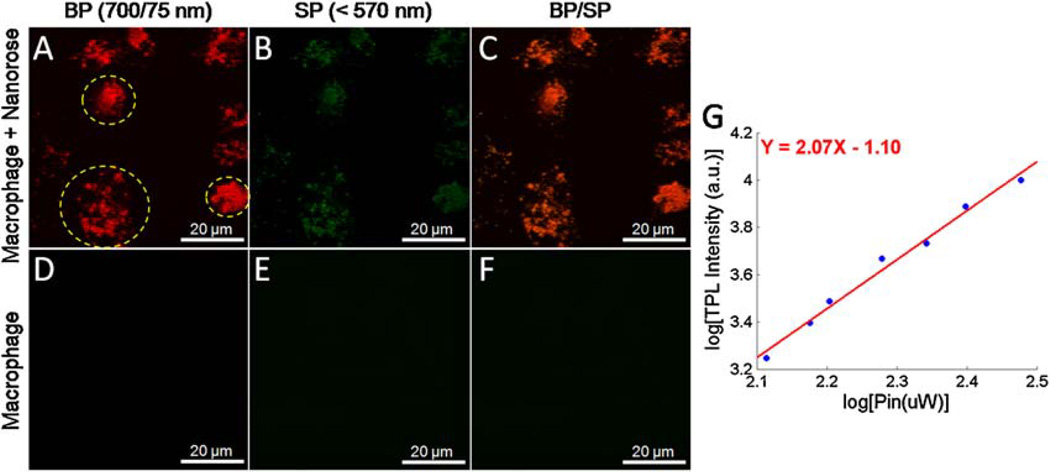

We investigated the capability of nanorose uptake by macrophages and use of nanorose as an imaging contrast agent for TPL microscopy in macrophage cell culture. Macrophage cell cultures were selected to simulate the in-timal layer of an atherosclerotic aorta since high concentration of macrophages in the arterial intima are characteristic of atherosclerotic plaques. TPL from macrophages were divided into two channels and co-registered into a merged two-channel image (Fig. 4). In macrophage culture with nanorose, strong TPL signals are detected inside macrophages in the red channel while much weaker TPL signal level is observed in the green channel (Fig. 4A,B). In the control macrophages without nanorose no TPL signal is detected in either red or green channel (Fig. 4D,E) at the same input laser power (15 mW). When TPL from nanorose is detected in both red and green channels, nanorose appears yellowish red (Fig. 4C). The nonlinear nature of the TPL signal was analyzed by measuring the dependence of the luminescence intensity as a function of laser excitation power. Excitation laser power was monitored by a photodiode giving the power of 13–30 mW delivered to the nanorose-loaded macrophages in cell culture. Luminescence intensities were measured by PMT2 (red channel). Figure 4G illustrates the quadratic dependence of luminescence intensity on the excitation laser power with a slope value of 2.07, confirming a TPL process.

Fig. 4.

Co-registered TPL images of (A,B) nanorose-loaded macrophages and (D,E) control macrophages without nanorose in two channels (red and green). C,F: Merged two-channel images of (A,B) and (D,E) respectively. G: Quadratic dependence of luminescence intensity (red channel) of nanoroses in macrophage cell culture on excitation laser power of 13–30 mW at 800 nm. A slope of 2.07 confirms the TPL process. Yellow circles in (A) indicate macrophage cells. BP, band-pass (700/75 nm); SP, short-pass (<570 nm).

Imaging Ex Vivo Rabbit Tissues

Ex vivo segments of rabbit liver and aorta were imaged by OCT, PTW imaging and TPL microscopy to obtain aorta surface structure and nanorose distribution. Rabbit liver was selected as a positive control because liver is known to contain a high density of macrophages. Several interesting findings of these imaging experiments are illustrated in Figure 5. Detailed surface structure of aorta segments is depicted by OCT (Fig. 5B,F). Peak and valley regions of the aorta surface are clearly visible in the 3D OCT image. Due to strong NIR absorption by nanorose, PTW imaging is able to screen nanorose distribution in the whole aorta segment. High intensity PTW signals are observed in both abdominal aorta and liver segments (bright region Fig. 5C,I) from the Positive rabbit with nanorose injection but not from the Control rabbit (Fig. 5G,K). Moreover, PTW signals are not observed in healthy thoracic aorta regions with no intimal hyperplasia from the Positive rabbit (data not shown). Due to the double-balloon injury process, the distribution of nanorose in abdominal aorta from the Positive rabbit is diffusive (Fig. 5C) with respect to the corresponding aorta surface structure as shown by OCT (Fig. 5B).

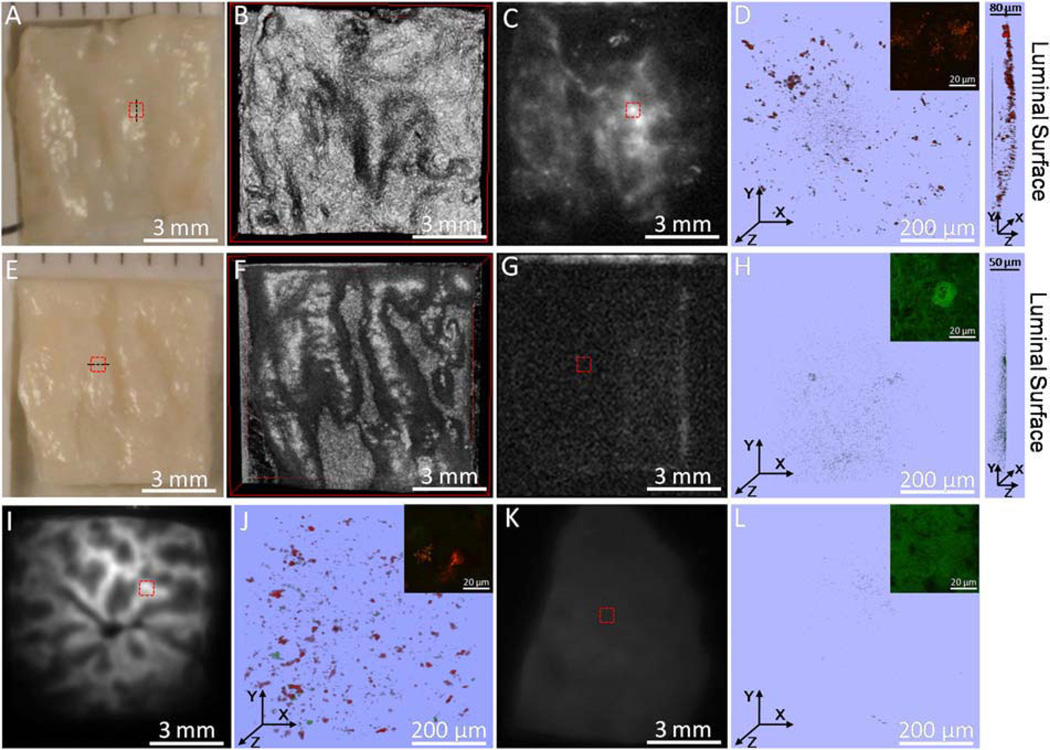

Fig. 5.

A–D: Digital image, 3D OCT, PTW imaging and 3D two-channel TPL microscopy (red box in (A,C)) of an abdominal aorta segment from the Positive rabbit. E–H: Digital image, 3D OCT, PTW imaging and 3D two-channel TPL microscopy (red box in (E,G)) of an abdominal aorta segment from the Control rabbit. I,J: PTW imaging and 3D two-channel TPL microscopy (red box in (I)) of a liver segment from the Positive rabbit. K,L: PTW imaging and 3D two-channel TPL microscopy (red box in (K)) of a liver segment from the Control rabbit. Inset in (D,H,J,L) shows a two-channel TPL image at a single depth at an amplified view within the corresponding 3D TPL image. Right side of (D,H) shows a side view of the corresponding 3D TPL image. Laser power delivered to the sample is 20 mW in all TPL measurements except insets of (H) 59 mW and (L) 45 mW.

Nanorose is also detected by TPL microscopy in the same aorta and liver segments from the Positive rabbit over a smaller field of view (500 × 500 × 80 µm3 ) as denoted by the red boxes in Figure 5C,I. Strong TPL signals from nanorose are observed (red color in Fig. 5D,J). Nanoroses are identified to be diffusely located in lateral directions of the tissue segments (Fig. 5D,J). From a side view of Figure 5D, nanoroses are also observed to be diffusely distributed in the axial direction along the luminal surface of the aorta segment within 20 µm in depth. In comparison, endogenous fluorescence signal detected from control aorta and liver segments is much weaker than nanorose TPL from the Positive rabbit at the same laser power delivered to the tissue (Fig. 5H,L). Moreover, the endogenous fluorescence signal is only detected in the green channel, suggesting that no nanorose is identified which emits stronger TPL in the red channel. Insets of Figure 5D,J show a closer view of nanorose distribution with strong TPL signal intensity, while much higher laser powers (59 and 45 mW), respectively, are needed to show the tissue structures from the Control rabbit at a similar endogenous fluorescence signal intensity in insets of Figure 5H,L.

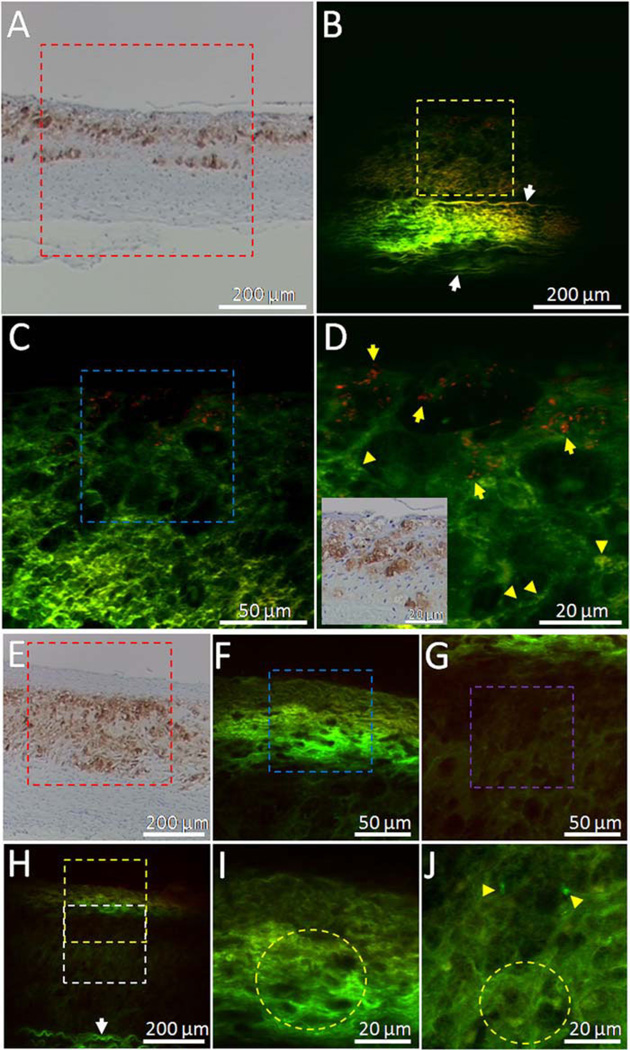

To verify that TPL signals from abdominal aorta segment from the Positive rabbit (Fig. 5D) originate from nanorose-loaded macrophages, unstained histological sections as denoted by the black dashed lines in Figure 5A,E were cut off and imaged by TPL microscopy. Sister histo-logical sections (5 mm apart from the corresponding unstained sections) were stained with RAM-11. Positive RAM-11 staining of the intimal layer (Fig. 6A,E) indicates presence of infiltrated macrophages in the aorta. High intensity TPL signals from nanorose (red color in Fig. 6B – D and pointed by yellow arrows in Fig. 6D) in the intimal layer co-localize with corresponding RAM-11 staining of superficial macrophages (Fig. 6A and inset in Fig. 6D), suggesting that TPL signals in red color are generated from superficial nanorose-loaded macrophages. The size of nanorose aggregations in the macrophages are 1–2 µm (Fig. 6D). Although macrophages are observed as deep as 100 µm from luminal surface of the aorta, most nanoroses are detected within 20 µm (Fig. 6D), consistent with nanorose distribution in the axial direction in the reconstructed 3D TPL image of the same aorta segment from the Positive rabbit (side view of Fig. 5D). This observation may suggest that the nanorose-loaded macrophages mostly reside in the very superficial regions of intima and have not migrated to deeper locations up to three days after intravenous nanorose injection. In contrast, in the unstained histological section from the Control rabbit, only endogenous fluorescence from aorta (green color) is observed in both superficial intima (Fig. 6F,I) and deeper intima (Fig. 6G,J) although dense accumulation of macro-phages are identified with corresponding RAM-11 stain in these regions (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

A: RAM-11 stain with positive macrophage staining of the black dashed line in Figure 5A. B–D: Two-channel TPL images of the red, yellow and blue boxes in (A), (B), and (C) respectively. Red color indicates TPL signals from nano-rose. Green color indicates endogenous fluorescence from aorta. Inset in (D) is a co-localized RAM-11 stain image of (D) amplified from (A). E: RAM-11 stain with positive macro-phage staining of the black dashed line inFigure 5E. H: TPL image of the red box in (E). F,I: TPL images of the yellow and blue boxes in (H) and (F), respectively. G,J: TPL images of the white and purple boxes in (H) and (G), respectively. Yellow arrows in (D) point to nanoroses. Yellow arrow heads in (D,J) point to lipid droplets. White arrows in (B,H) point to elastin fibers. Yellow circles in (I,J) indicate clusters of macrophage cells defined by dark nuclei. Laser power delivered to the sample is 20 mW. High intensity TPL signals from nanorose in intimal layer (B–D) co-localize with corresponding RAM-11 staining of superficial macrophages in the histo-logical section from the Positive rabbit (A), while no TPL signal from nanorose (red color) is observed in the histological section from the Control rabbit (F–J).

Endogenous fluorescence from aorta may originate from elastin fibers (pointed by white arrows in media layer in Fig. 6B,H) [29,33,40]. Moreover, macrophage-like cellular structures with dark nuclei (indicated by yellow circles in Fig. 6I,J) and possibly lipid droplets (pointed by yellow arrow heads in Fig. 6D,J) in or outside macro-phages are also observed [45,46].

DISCUSSION

Nanorose was tested in macrophage cell culture as an imaging contrast agent for TPL microscopy. Due to a dextran coating and 30 nm particle size, a high uptake rate of nanorose by macrophages compared to gold nanoshells is observed and measured to be more than 7,500 nanoroses per macrophage cell [47]. Higher TPL signal intensity is observed in the red channel (700/75 nm) compared to green channel (<570 nm) from the nanorose-loaded mac-rophages (Fig. 4A,B), consistent with the TPL spectrum of nanorose (Fig. 1B). Endogenous fluorescence from control macrophages without nanorose is not observed when the same laser power is applied (Fig. 4D,E). In fact, 10 times greater laser power than that used in nanorose-loaded macrophages is needed (data not shown) to bring endogenous fluorescence intensity from control macrophages to the same signal level induced by nanorose as shown in Figure 4A.

To demonstrate the capability of TPL microscopy in combination with OCT to detect aorta-based macro-phages, a hypercholesterolemic rabbit model of focal aorta inflammation induced by endothelial abrasion followed by double-balloon injury was utilized. The resulting injury-induced neointima in abdominal aorta was particularly rich in macrophages, simulating macrophage accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques. In contrast to previous studies performed in animal models with diffuse atherosclerosis, this inflammation model allows straightforward anatomic localization of the inflammatory arterial lesion and a direct comparison of diseased versus normal artery portions in the same rabbit (Fig. 2B – D) in a much shorter formation time (from 4–5 months [48] to 10 weeks). Double-balloon injured lesions are widely spread in the aorta, consistent with the high accumulation and diffusive distribution of nanoroses in these areas as detected by TPL microscopy (Figs. 5D and 6B – D) and PTW imaging (Fig. 5C).

Most nanoroses are superficially detected by TPL microscopy within 20 µm from luminal surface of the aorta as shown in the histological section (Fig. 6D). However, RAM-11 stained macrophages from corresponding sister section are distributed as deep as 100 mm (Fig. 6A). This observation suggests that macrophages taking up nanorose are superficial in the aorta and nanoroses may migrate and then reside (no-slip condition) on the endothelial surface and be partially engulfed by superficial macrophages. Deeper in situ macrophages and macro-phages that migrated into deeper locations before nanorose injection may not be able to take up nanorose possibly because nanorose cannot penetrate into the intima directly through diffusion or no nanorose is delivered through the vasa vasorum. In fact, vascular permeability and rate of particle (molecule or nanoparticle) transfer from the vascular lumen to peripheral tissue is regulated and limited by transcytosis of endothelial cells [49,50]. Moreover, apoptotic and necrotic macrophages contribute to lipid core formation in advanced atherosclerotic plaques [51]. These macrophage debris can stain RAM-11 positive but are not intact and would no longer take up nanorose in situ.

Although nanorose uptake by macrophages has been identified in our cell culture study (Fig. 4), their transport pathway to aorta-based macrophages is not elucidated. Previous studies have proposed three possible mechanisms for transport of superparamagnetic nanoparticles to arterial tissue [52–55], including monocyte-mediated migration, transcytosis across the endothelium followed by uptake by in situ macrophages and diffusion into the adventitia via the vaso vasorum. TPL microscopy results of histological sections (Fig. 6B) show that nanorose is not detected at deeper locations (e.g., 100–300 µm) in the aorta, indicating that nanorose diffusion via the vasa vasorum may not have occurred in our study. However, the relative contributions of monocyte-mediated migration and endothelial transcytosis of nanorose remain to be determined.

Simultaneous observation of macrophage distribution and plaque surface structure offers the ability to characterize plaque composition and identify vulnerable plaque regions more prone to rupture. However, several limitations need to be addressed before the current imaging approach can be used in patients with atherosclerosis to study the natural history of plaque inflammation over time and the efficacy of treatments aimed at plaque stabilization. First, TPL microscopy and OCT were performed in this study, respectively, on ex vivo tissues. An intravascular catheter is required to realize in vivo imaging of macrophages in plaques. Second, TPL microscopy has a smaller field of view than OCT in the current study. Co-registered fields of view can be achieved by coupling two-photon excitation light with OCT light into a catheter. Third, the penetration depth of TPL microscopy is shorter than OCT at current wavelength (800 vs. 1,060 nm). A longer wavelength for two-photon excitation will provide deeper penetration depth in tissue. Although the current study utilized a model of arterial wall inflammation which does not contain the complex nature of advanced atherosclerotic plaques, TPL microscopy in combination with OCT using nanorose as a contrast agent to detect plaque-based macrophages and assess macrophage density quantitatively is promising. Additional studies are required to test the capability of this combined imaging approach for the detection of macrophages in vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques.

CONCLUSION

By utilizing TPL microscopy in combination with OCT we demonstrate detection of nanorose with respect to aorta surface structure in a double-balloon injured hyper-cholesterolemic rabbit model. Nanorose presence is also detected with PTW imaging. Co-localization of nanorose identified by TPL microscopy with RAM-11 stained macrophages in the corresponding histological section suggests that TPL signal in the red channel (700/75 nm) is generated by superficial nanorose-loaded macrophages. Our results suggest that nanorose-loaded macrophages are diffusively distributed in the aorta and superficially located (within 20 µm from the luminal surface). This study indicates that combined TPL microscopy and OCT is promising for the detection of aorta inflammation in the hypercholesterolemic rabbit using nanorose as a contrast agent. This combined imaging approach will need to be tested in further studies for macrophage detection in atherosclerotic plaques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. This study was supported in part by a travel grant from the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery to Wang, a Veterans Administration merit grant to Feldman, a Welch Foundation grant F-1319 and NSF grant CBET-0968038 to Johnston, and the Department of Energy Center for Frontiers of Subsurface Energy Security.

Contract grant sponsor: American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery; Contract grant sponsor: Veterans Administration Merit Grant; Contract grant sponsor: Welch Foundation Grant; Contract grant number: F-1319; Contract grant sponsor: NSF Grant; Contract grant number: CBET-0968038; Contract grant sponsor: Department of Energy Center for Frontiers of Subsurface Energy Security.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part I: General considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P, Aikawa M. Stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques: New mechanisms and clinical targets. Nat Med. 2002;8:1257–1262. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrose JA, Winters SL, Stern A, Eng A, Teichholz LE, Gorlin R, Fuster V. Angiographic morphology and the patho-genesis of unstable angina pectoris. J Am Coll Cardioll. 1985;5:609–616. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, Hjemdahl-Monsen CE, Leavy J, Weiss M, Borrico S, Gorlin R, Fuster V. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:56–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hackett D, Davies G, Maseri A. Pre-existing coronary stenosis in patients with first myocardial infarction are not necessarily severe. Eur Heart J. 1988;9:1317–1323. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little WC, Downes TR, Applegate RJ. The underlying coronary lesion in myocardial infarction: Implications for coronary angiography. Clin Cardiol. 1991;14:868–874. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960141103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nobuyoshi M, Tanaka M, Nosaka H, Kimura T, Yokoi H, Hamasaki N, Kim K, Shindo T, Kimura K. Progression of coronary atherosclerosis: Is coronary spasm related to progression? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:904–910. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90745-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giroud D, Li JM, Urban P, Meier B, Rutishauer W. Relation of the site of acute myocardial infarction to the most severe coronary arterial stenosis at prior angiography. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:729–732. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90495-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111:3481–3488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas AR, Korol R, Pepine CJ. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: Some thoughts about acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2006;113:e728–e732. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.601492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies MJ, Thomas A. Thrombosis and acute coronary-artery lesions in sudden cardiac ischemic death. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1137–1140. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405033101801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JL, George SJ, Newby AC, Jackson CL. Divergent effects of matrix metalloproteinases 3, 7, 9, and 12 on atherosclerotic plaque stability in mouse brachiocephalic arteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15575–15580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henney AM, Wakeley PR, Davies MJ, Foster K, Hembry R, Murphy G, Humphries S. Localization of stromelysin gene expression in atherosclerotic plaques by in situ hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8154–8158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galis ZS, Sukhova GK, Lark MW, Libby P. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2493–2503. doi: 10.1172/JCI117619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikkari ST, O’Brien KD, Ferguson M, Hatsukami T, Welgus HG, Alpers CE, Clowes AW. Interstitial collagenase (MMP-1) expression in human carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1995;92:1393–1398. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Libby P, Geng YJ, Aikawa M, Schoenbeck U, Mach F, Clinton SK, Sukhova GK, Lee RT. Macrophages and atherosclerotic plaque stability. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1996;7:330–335. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199610000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taubman MB, Fallon JT, Schecter AD, Giesen P, Mendlo-witz M, Fyfe BS, Marmur JD, Nemerson Y. Tissue factor in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Weber DK, Kutys R, Finn AV, Gold HK. Pathologic assessment of the vulnerable human coronary plaque. Heart. 2004;90:1385–1391. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.041798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanz J, Fayad ZA. Imaging of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2008;451:953–957. doi: 10.1038/nature06803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershlick AH, de Belder M, Chambers J, Hackett D, Keal R, Kelion A, Neubauer S, Pennell DJ, Rothman M, Signy M, Wilde P. Role of non-invasive imaging in the management of coronary artery disease: An assessment of likely change over the next 10 years.A report from the British Cardiovascular Society Working Group. Heart. 2007;93:423–431. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.108779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nahrendorf M, Jaffer FA, Kelly KA, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P, Weissleder R. Noninvasive vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 imaging identifies inflammatory activation of cells in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;114:1504–1511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amirbekian V, Lipinski MJ, Briley-Saebo KC, Amirbekian S, Aguinaldo JGS, Weinreb DB, Vucic E, Frias JC, Hyafil F, Mani V, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Detecting and assessing macrophages in vivo to evaluate atherosclerosis noninvasively using molecular MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:961–966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair A, Kuban BD, Obuchowski N, Vince DG. Assessing spectral algorithms to predict atherosclerotic plaque composition with normalized and raw intravascular ultrasound data. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27:1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenya N, Etsuo T, Osamu K, Vince DG, Renu V, Jean-Francois S, Akira M, Yoshihiro T, Tatsuya I, Mariko E, Tetsuo M, Mitsuyasu T, Takahiko S. Accuracy of in vivo coronary plaque morphology assessment: A validation study of in vivo virtual histology compared with in vitro histopathology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2405–2412. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyafil F, Cornily JC, Feig JE, Gordon R, Vucic E, Amirbekian V, Fisher EA, Fuster V, Feldman LJ, Fayad ZA. Noninvasive detection of macrophages using a nanoparticulate contrast agent for computed tomography. Nature Med. 2007;13:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nm1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nahrendorf M, Zhang H, Hembrador S, Panizzi P, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P, Swirski FK, Weissleder R. Nanoparticle PET-CT imaging of macrophages in inflammatory atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2008;117:379–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kircher MF, Grimm J, Swirski FK, Libby P, Gerszten RE, Allport JR, Weissleder R. Noninvasive in vivo imaging of monocyte trafficking to atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2008;117:388–395. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.719765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Zandvoort M, Engels W, Douma K, Beckers L, oude Egbrink M, Daemen M, Slaaf DW. Two-photon microscopy for imaging of the (atherosclerotic) vascular wall: A proof of concept study. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:54–63. doi: 10.1159/000076246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoumi A, Lu XA, Kassab GS, Tromberg BJ. Imaging coronary artery microstructure using secondharmonic and two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 2004;87:2778–2786. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulesteix T, Pena AM, Pages N, Godeau G, Sauviat MP, Beaurepaire E, Schanne-Klein MC. Micrometer scale ex vivo multiphoton imaging of unstained arterial wall structure. Cytometry Part A. 2006;69A:20–26. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le TT, Langohr IM, Locker MJ, Sturek M, Cheng JX. Label-free molecular imaging of atherosclerotic lesions using multimodal nonlinear optical microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:0540071–05400710. doi: 10.1117/1.2795437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lilledahl MB, Haugen OA, de Lange Davies C, Svaasand LO. Characterization of vulnerable plaques by multiphoton microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:0440051–04400512. doi: 10.1117/1.2772652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brezinski ME, Tearney GJ, Bouma BE, Boppart SA, Hee MR, Swanson EA, Southern JF, Fujimoto JG. Imaging of coronary artery microstructure (in vitro) with optical coherence tomography. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:92–93. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raffel OC, Tearney GJ, Gauthier DD, Halpern EF, Bouma BE, Jang IK. Relationship between a systemic inflammatory markers, plaque inflammation, and plaque characteristics determined by intravascular optical coherence tomography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1820–1827. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka A, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, Kubo T, Takarada S, Tanimoto T, Kuroi A, Tsujioka H, Ikejima H, Ueno S, Kataiwa H, Okouchi K, Kashiwaghi M, Matsumoto H, Take-moto K, Nakamura N, Hirata K, Mizukoshi M, Akasaka T. Morphology of exertion-triggered plaque rupture in patients with acute coronary syndrome: An optical coherence tomography study. Circulation. 2008;118:2368–2373. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.782540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vancraeynest D, Pasquet A, Roelants V, Gerber BL, Vano-verschelde JJ. Imaging the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1961–1979. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma LL, Feldman MD, Tam JM, Paranjape AS, Cheruku KK, Larson TA, Tam JO, Ingram DR, Paramita V, Villard JW, Jenkins JT, Wang T, Clarke GD, Asmis R, Sokolov K, Chan-drasekar B, Milner TE, Johnston KP. Small multifunctional nanoclusters (nanoroses) for targeted cellular imaging and therapy. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2686–2696. doi: 10.1021/nn900440e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mornet S, Vasseur S, Grasset F, Duguet E. Magnetic nano-particle design for medical diagnosis and therapy. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:2161–2175. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu W, Braz JC, Dutton AM, Prusakov P, Rekhter M. In vivo imaging of atherosclerotic plaques in apolipoprotein E deficient mice using nonlinear microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:0540081–05400810. doi: 10.1117/1.2800337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen T, Weissleder R, Papisov M, Bogdanov A, Jr, Brady TJ. Monocrystalline iron oxide nanocompounds (Mion): Physico-chemical properties. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:599–604. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang T, Qiu J, Ma LL, Li X, Sun J, Ryoo S, Johnston KP, Feldman MD, Milner TE. Nanorose and lipid detection in atherosclerotic plaque using dual-wavelength photothermal wave imaging. Proc SPIE. 2010;7562:75620S–75620S-7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park J, Estrada A, Sharp K, Sang K, Schwartz JA, Smith DK, Coleman C, Payne JD, Korgel BA, Dunn AK, Tunnell JW. Two-photon-induced photoluminescence imaging of tumors using near-infrared excited gold nanoshells. Opt Exp. 2008;16(3):1590–1599. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.001590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leibovich SJ, Polverini PJ, Shepard HM, Wiseman DM, Shively V, Nuseir N. Macrophage-induced angiogenesis is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1987;329:630–632. doi: 10.1038/329630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim RS, Kratzer A, Barry NP, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Miyazaki M, Mantulin WW, Levi M, Potma EO, Tromberg BJ. Multimodal CARS microscopy determination of the impact of diet on macrophage infiltration and lipid accumulation on plaque formation in ApoE-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1729–1737. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M003616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang H, Langohr IM, Sturek M, Cheng J. Imaging and quantitative analysis of atherosclerotic lesions by CARS-based multimodal nonlinear optical microscopy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1342–1348. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sapozhnikova V, Willsey B, Asmis R, Wang T, Jenkins JT, Mancuso JJ, Ma L, Kuranov R, Milner TE, Johnston KP, Feldman MD. Near infrared fluorescence produced by gold nanoclusters (nanoroses) J Biomed Opt. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.2.026006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Okada Y, Voglic SJ, Clinton SK, Brinckerhoff CE, Sukhova GK, Libby P. Lipid lowering by diet reduces matrix metalloproteinase activity and increases collagen content of rabbit atheroma: A potential mechanism of lesion stabilization. Circulation. 1998;97:2433–2444. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frank PG, Pavlides S, Lisanti MP. Caveolae and transcytosis in endothelial cells: Role in atherosclerosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu W, Tan YZ, Hu KL, Jiang XG. Cationic albumin conjugated pegylated nanoparticle with its transcytosis ability and little toxicity against blood-brain barrier. Int J Pharm. 2005;295:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabas I. Macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis: Consequences on plaque progression and the role of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2333–2339. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corot C, Petry KG, Trivedi R, Saleh A, Jonkmanns C, le Bas JF, Blezer E, Rausch M, Brochet B, Foster-Gareau P, Bale´riaux D, Gaillard S, Dousset V. Macrophage imaging in central nervous system and in carotid atherosclerotic plaque imaging using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide in magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2004;39:619–625. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000135980.08491.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dousset V, Delalande C, Ballarino L, Quesson B, Seilhan D, Coussemacq M, Thiaudiere E, Brochet B, Canioni P, Caille JM. In vivo macrophage activity imaging in the central nervous system detected by magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:329–333. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199902)41:2<329::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rausch M, Hiestand P, Baumann D, Cannet C, Rudin M. MRI-based monitoring of inflammation and tissue damage in acute and chronic relapsing EAE. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:309–314. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corot C, Robert P, Idée J, Port M. Recent advances in iron oxide nanocrystal technology for medical imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1471–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]