Significance

Biomolecular binding, which controls the realization of biomolecular function, is ubiquitous and fundamental to many cellular processes. We quantified the intrinsic energy landscapes of flexible biomolecular recognition—i.e., the binding–folding. Our findings reveal that the energy landscape topography determines the thermodynamics, kinetics, and the association mechanism of the binding–folding dynamics. These three aspects are closely related to feasibility, efficiency, and the ways of realizing biomolecular function, respectively. Our results provide a unique way to address the long-standing debate of the “structure–dynamics–function” relationship using landscape topography and establish the connections between recognition landscape theory and experimental measurements.

Keywords: energy landscape theory, flexible binding-folding, intrinsically disordered proteins

Abstract

Biomolecular functions are determined by their interactions with other molecules. Biomolecular recognition is often flexible and associated with large conformational changes involving both binding and folding. However, the global and physical understanding for the process is still challenging. Here, we quantified the intrinsic energy landscapes of flexible biomolecular recognition in terms of binding–folding dynamics for 15 homodimers by exploring the underlying density of states, using a structure-based model both with and without considering energetic roughness. By quantifying three individual effective intrinsic energy landscapes (one for interfacial binding, two for monomeric folding), the association mechanisms for flexible recognition of 15 homodimers can be classified into two-state cooperative “coupled binding–folding” and three-state noncooperative “folding prior to binding” scenarios. We found that the association mechanism of flexible biomolecular recognition relies on the interplay between the underlying effective intrinsic binding and folding energy landscapes. By quantifying the whole global intrinsic binding–folding energy landscapes, we found strong correlations between the landscape topography measure Λ (dimensionless ratio of energy gap versus roughness modulated by the configurational entropy) and the ratio of the thermodynamic stable temperature versus trapping temperature, as well as between Λ and binding kinetics. Therefore, the global energy landscape topography determines the binding–folding thermodynamics and kinetics, crucial for the feasibility and efficiency of realizing biomolecular function. We also found “U-shape” temperature-dependent kinetic behavior and a dynamical cross-over temperature for dividing exponential and nonexponential kinetics for two-state homodimers. Our study provides a unique way to bridge the gap between theory and experiments.

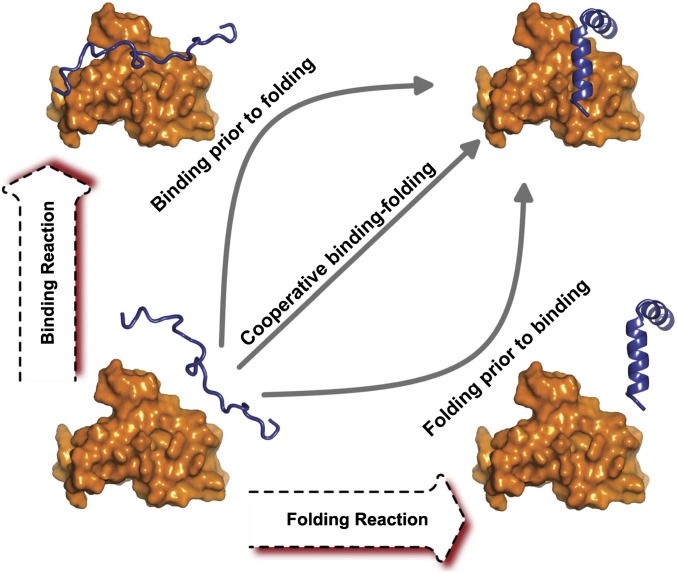

Biomolecules realize their functions through interacting with other molecules. Fully understanding the manner in which a protein participates in the process of biomolecular recognition is the basis for studying cellular activity. The first proposal of the binding mechanism was given by Fischer, called “lock-and-key,” to explain the rigid biomolecular docking (1). However, more and more experimental evidence has been accumulating in favor of the idea that protein binding often associates conformational changes. In this regard, considering the local configurational plasticity in protein–protein interactions, two scenarios have been proposed. One is named “induced fit” (2) and the other is called “conformational selection” (3). Furthermore, increasing recent evidence demonstrates that some isolated proteins are found to be disordered at physiological conditions. These proteins, known as “intrinsically disordered proteins” (IDPs), have refreshed our understanding of protein folding and function (4–6). The unstructured characteristic provides binding of IDPs with the advantage of multiple targeted partners, high association rates, high specificity, and moderate affinity (7, 8). For IDPs, the global conformational changes are always associated in their binding, known as “binding induced folding.” By investigating the synchronization of binding and folding, the association mechanism of IDPs can be classified into cooperative “coupled binding–folding” as well as noncooperative “binding prior to folding” and “folding prior to binding” (Fig. 1). As a result, it is now recognized that not only the well-defined 3D structure but also the conformational flexibility are critical pieces of information to determine the function of protein.

Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram of three typical association mechanisms for IDPs. The diagonal line represents the cooperative process with binding and folding strongly coupled. The noncooperative processes are represented by the two lines along the rectangular edge, corresponding to binding prior to folding (up) and folding prior to binding (down), respectively.

The energy landscape theory has been proposed to help understand the dynamics of protein folding (9–12). The shape of the folding energy landscape of naturally evolved proteins appears to be minimally frustrated and funneled so that the Levinthal’s paradox (13) can be solved with folding going through multiple routes toward the native structure rather than one single specific pathway (14–16). The folding landscape is widely studied in experiments and simulations (17–21) and has deepened our understanding of protein folding. As folding can be regarded as self-binding, the flexible recognition with large global conformational changes can be regarded as a process of binding coupled with folding—i.e., binding–folding. Therefore, binding and folding are analogous to each other except for the chain connectivity. It is expected that Levinthal’s paradox also exists in flexible protein binding. Therefore, it is feasible to extend the folding energy landscape concept to the binding dynamics to solve the conformational search problem in flexible binding and investigate the function of protein (22–27). The funneled binding landscape indicates that naturally evolved binding also follows the principle of minimal frustration, resulting in a reasonable physiological time for realizing the function of protein with vital activity.

However, protein binding involving at least two chains is certainly different from protein folding in some respects. The global binding–folding energy landscape is expected to be a combination or interactions of an interfacial binding energy landscape and two monomeric folding energy landscapes (28). The flexible binding–folding energy landscape, as a result of the delicate combination or balance of folding and binding, controls the way a protein realizes its function during the protein–protein associations. For the noncooperative folding prior to binding scenario, the monomeric folding energy landscapes are expected to be more funneled than the interfacial binding energy landscapes, and vice versa for the binding prior to folding scenario. The cooperative coupled binding–folding scenario is an intermediary between the two noncooperative scenarios. Notice that the global binding–folding energy landscapes do not require that the three individual binding and folding energy landscapes are necessarily all funneled. For IDPs, they do not fold to a specific 3D structure, and therefore, their individual folding energy landscapes will be highly rugged. However, IDPs realize their functions by folding to ordered structures upon binding to their targets (29, 30). In other words, coupled with binding, the individual folding energy landscapes with functional rearrangements have been changed with strong bias toward the native binding structure during the associations. In conclusion, the binding–folding energy landscapes are the underlying key factors governing the protein–protein interactions and control the realization of protein’s function.

In our work, we focused on the flexible biomolecular recognition in terms of binding–folding dynamics of 15 homodimers, which are formed by two identical monomers each (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). We quantified the whole global intrinsic landscape and the three individual intrinsic energy landscapes (one for interfacial binding, two for monomeric folding) from underlying density of states (DOS) extracted from the binding–folding dynamics using a structure-based model both with and without considering energetic roughness. We showed that the topography of each individual effective landscape and the whole global landscape of flexible recognition in terms of binding–folding can be quantified by a dimensionless ratio Λ of the energy gap between native state and average of nonnative states versus roughness modulated by the entropy. We found that the association mechanism of flexible recognition strongly relies on the interplay between the topographies of the underlying effective intrinsic binding and folding energy landscapes. This interplay changes with different strengths of nonnative interactions. We also showed that the whole global landscape topography measure  is strongly correlated with the thermodynamics characterized by the binding transition temperature versus the glassy trapping temperature and the kinetics characterized by the binding time. By investigating the kinetics of Troponin C site, which is a two-state homodimer, we demonstrated that the temperature-dependent kinetic behavior is under the control of the topography of energy landscapes. The results are consistent with the previous analytical theories and experiments (31–33). Therefore, our work gives strong evidence that the topography of the intrinsic energy landscape is the key to understanding the binding–folding mechanism in terms of both thermodynamics and kinetics. Since the thermodynamics and kinetics of binding–folding dynamics can be explicitly measured by experiments (31, 34–36), and the underlying physical observable quantities are found to be strongly dependent on the theoretical energy landscape topography, our simulation findings can be regarded as the quantitative connections between the experiments and theory. This provides a unique way to bridge the theory and experimental measurements of flexible biomolecular recognition.

is strongly correlated with the thermodynamics characterized by the binding transition temperature versus the glassy trapping temperature and the kinetics characterized by the binding time. By investigating the kinetics of Troponin C site, which is a two-state homodimer, we demonstrated that the temperature-dependent kinetic behavior is under the control of the topography of energy landscapes. The results are consistent with the previous analytical theories and experiments (31–33). Therefore, our work gives strong evidence that the topography of the intrinsic energy landscape is the key to understanding the binding–folding mechanism in terms of both thermodynamics and kinetics. Since the thermodynamics and kinetics of binding–folding dynamics can be explicitly measured by experiments (31, 34–36), and the underlying physical observable quantities are found to be strongly dependent on the theoretical energy landscape topography, our simulation findings can be regarded as the quantitative connections between the experiments and theory. This provides a unique way to bridge the theory and experimental measurements of flexible biomolecular recognition.

Results and Discussions

Quantifying the Intrinsic Energy Landscapes.

In our molecular simulations, canonical ensembles at constant temperatures are used, mapping directly the free energy landscape. Using multidimensional free energy landscapes (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), the association mechanisms of 15 homodimers in our studies have been classified into two-state cooperative coupled binding–folding and three-state noncooperative folding prior to binding scenarios. The association mechanisms uncovered here are consistent with the experimental measurements (37, 38) and previous simulation results (39, 40). The free energy, which is sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature, is therefore not a pure and direct reflection of the underlying interactions. To explore the underlying intrinsic energetic interactions and establish the connections to the binding–folding mechanisms, we need to quantify the intrinsic energy (rather than free energy) landscapes in binding–folding dynamics. The intrinsic energy landscape is reflected by DOS, a statistical distribution in microcanonical ensemble, and is independent of the temperature. Since there is a mathematical relationship connecting the canonical ensemble and microcanonical ensemble,  , through this we can obtain DOS using molecular simulations. Simulation methodology and calculation details can be found in SI Appendix and our previous work (21).

, through this we can obtain DOS using molecular simulations. Simulation methodology and calculation details can be found in SI Appendix and our previous work (21).

Whole global binding–folding energy landscapes.

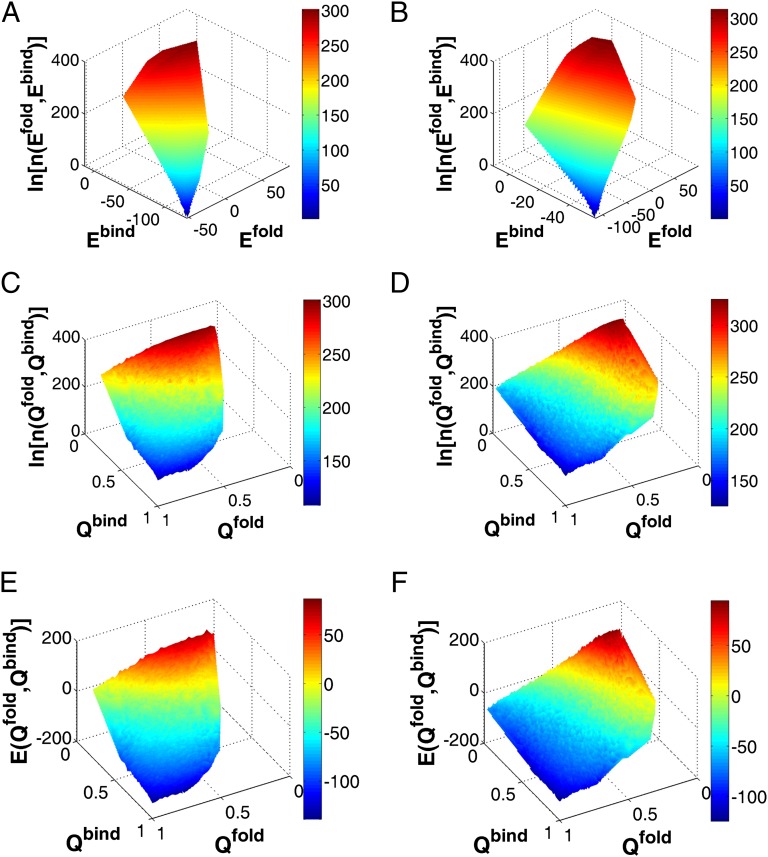

To visualize the intrinsic energy landscape, we used energy and structural similarity to native structure Q, which is defined as the fraction of the native contacts, as the reaction coordinates to plot the DOS for the two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor. As we can see from Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S9, the intrinsic global binding–folding energy landscapes, represented by DOS, are all funneled toward the native state. The distributions of DOS demonstrate that the binding–folding happens with decreasing both energy and entropy along the binding–folding process. This leads to an energy–entropy compensation in free energy landscapes. At physiological conditions, naturally evolved binding happens with the balance between the energy decreasing and temperature-dependent entropy decreasing, leading to the conclusion that the native binding states are more populated than the nonnative states with free energy minimum. To see how the configuration evolves during the binding–folding proceeding, we observed DOS along Q (Fig. 2 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). We clearly see that DOS decreases as the binding–folding approaches the native binding state, implying that the space for the configuration searching decreases during the process. By projecting the energy to Q (Fig. 2 E and F and SI Appendix, Fig. S11), we clearly see that the energy decreases with the binding–folding proceeding to the native state, indicating the underlying energy landscapes are funneled. In Fig. 2, we can see that for the two-state homodimer, the binding–folding happens with a narrower concentrated band along the diagonal line in the phase space, compared with that of the three-state homodimer with a more dispersed distribution in the phase space. It indicates that for the two-state homodimer, the binding and folding is a more synchronized process with strong coupling, whereas for the three-state homodimer, the binding and folding are nonsynchronized processes with folding happening before binding. Overall, different homodimers show different shapes of DOS, implying that the energy landscape can be used as an underlying factor to classify the dimers.

Fig. 2.

Energy landscapes of binding and folding. Logarithms of DOS are plotted as a function of energy for (A) two-state homodimer Arc repressor (PDB ID code 1ARR) and (B) three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor (PDB ID code 1COP).  and

and  are the energy of interfacial binding and monomeric folding interaction. Logarithm of DOS is plotted as a function of Q for (C) Arc repressor and (D) Lambda Cro repressor.

are the energy of interfacial binding and monomeric folding interaction. Logarithm of DOS is plotted as a function of Q for (C) Arc repressor and (D) Lambda Cro repressor.  and

and  are the fraction of native binding and folding contacts. Because the homodimers are formed by two identical chains, the folding properties of the two monomers are expected to be same. Here, we use quantities of one of the two monomers to represent the corresponding monomeric folding quantities. Energy is plotted as a function of

are the fraction of native binding and folding contacts. Because the homodimers are formed by two identical chains, the folding properties of the two monomers are expected to be same. Here, we use quantities of one of the two monomers to represent the corresponding monomeric folding quantities. Energy is plotted as a function of  and

and  for (E) Arc repressor and (F) Lambda Cro repressor. White region is not probed by the binding–folding simulations. Energy is in the reduced unit (73).

for (E) Arc repressor and (F) Lambda Cro repressor. White region is not probed by the binding–folding simulations. Energy is in the reduced unit (73).

Individual effective binding and folding energy landscapes.

The binding–folding process can be considered as a combination of one interfacial binding and two monomeric folding. Here, we extracted these three individual intrinsic energy landscapes from the binding–folding simulations, and each energy landscape has its unique energy gap, roughness, and entropy. Similar to that of folding energy landscapes (21), we quantified the topography of these three energy landscapes. It is worth noticing that these three individual energy landscapes obtained from the binding–folding dynamics should be regarded as “effective” energy landscapes, as these quantified interfacial binding landscapes and monomeric folding landscapes here are deduced from binding–folding simulations instead of independent binding and folding, and they are strongly coupled in the association.

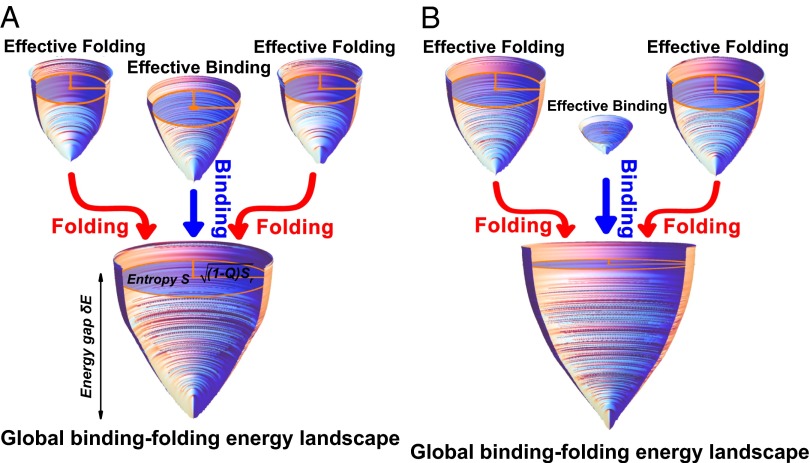

Fig. 3 shows quantitatively how the binding and folding proceed on their own effective energy landscapes and how these three individual energy landscapes combine to result in the whole global energy landscape. As the binding–folding proceeds, the energy decreases, with the energy decreasing from the top of the funnels to the bottom; the structural similarity to the native structure increases, quantified by the decreasing of semimajor axis of the ellipse at each stratum; and the entropy decreases, quantified by the decreasing area of the ellipse at each stratum. This is a quantitative illustration of how the binding–folding process occurs on the energy landscape. In addition, we can see that different homodimers have different contributions to binding and folding in the associations. For the two-state homodimer, the effective binding funnel is more significant and contributes more than the effective folding funnel to the global binding–folding energy landscape (Fig. 3A). It indicates that this association scenario is driven more by binding. However, for the three-state homodimer, the effective folding funnel is more significant than the effective binding funnel (Fig. 3B). It indicates that the association mechanism relies more on the folding of the monomers. Therefore, these three effective energy landscapes are the reflections of the relative weight for interchain binding and intrachain folding contributing to the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes, implying that they control the association mechanism.

Fig. 3.

The individual effective binding and folding as well as the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes. Quantified energy landscapes for (A) two-state homodimer Arc repressor and (B) three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor. All of the funnels are extracted from the binding–folding simulations. The depth of the funnel in z axis corresponds to the energy. Each stratum perpendicular to the energy axis is an ellipse, of which the area is equal to the entropy S. The semimajor axis of the ellipse is  , and a monotonic decreasing function of the fraction of native contacts Q,and

, and a monotonic decreasing function of the fraction of native contacts Q,and  is a scaling constant for each funnel to achieve a better visualization. The other semi-axis of the ellipse is therefore given by

is a scaling constant for each funnel to achieve a better visualization. The other semi-axis of the ellipse is therefore given by  . The unbound states are located at the top of the funnels with the largest energy, entropy, and smallest Q, and the bottom of the funnel corresponds to the native binding state with

. The unbound states are located at the top of the funnels with the largest energy, entropy, and smallest Q, and the bottom of the funnel corresponds to the native binding state with  and

and  . The shape of the funnels is therefore a representation of the relationship between energy E, entropy S, and structural similarity to native structure Q. The energy and entropy are normalized by the sizes of the homodimers for a better visualization.

. The shape of the funnels is therefore a representation of the relationship between energy E, entropy S, and structural similarity to native structure Q. The energy and entropy are normalized by the sizes of the homodimers for a better visualization.

Topography of the Effective Intrinsic Energy Landscapes Determines the Association Mechanism.

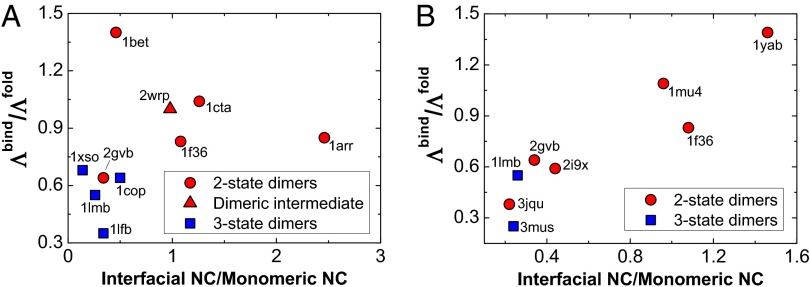

It has been recognized that the association mechanism can be roughly distinguished using structural characterization in the protein complexes. By collecting a range of data for homodimers with varying sequence length, topology, secondary structure content, and function, Gunasekaran et al. found that the per-residue interface and surface areas of the two-state homodimers are shown to be significantly larger than that of the three-state homodimers (41), implying that the two-state homodimers have much stronger interchain but weaker intrachain interactions than the three-state homodimers. Here, we examined this structural property of these two types of homodimers by calculating the ratio of the native contact number of interface with respect to intramonomer in the bound dimers (Fig. 4). The large ratio, which is the strong interfacial and weak intramonomeric interactions, leads to the folded monomer being less probable in the dissociative state and the stabilization of the dimers being mainly from the interactions at the interface. These features result in a two-state binding-coupled folding mechanism. In contrast, the small ratio, showing strong intramonomeric interactions, can fold the isolated monomer independently, and therefore, the association will go through monomeric intermediate states, leading to a three-state association mechanism (39, 40).

Fig. 4.

The phase diagram of association mechanism. The phase diagram correlates with the spatial structural property and the topography of effective binding and folding energy landscapes for (A) 10 different-sized homodimers and (B) eight similar-sized homodimers. The structural property is described by the ratio of the native contact number of interface versus intramonomer. The topography of the energy landscapes is quantified by the ratio between the effective energy landscape topography measure for interfacial binding  and monomeric folding

and monomeric folding  . The PDB ID codes of the 15 homodimers are shown.

. The PDB ID codes of the 15 homodimers are shown.

Because biomolecular recognition is determined by the underlying energy landscape, the association mechanism should be quantitatively reflected by the topography of the energy landscapes. In theory, the topography of a funneled energy landscape can be determined by three quantities: energy gap δE, energy roughness ΔE, and entropy S, corresponding to the slope, the bumpiness, and the size of the energy funnel, respectively (10, 25, 32, 42–45). These three quantities are extracted from the intrinsic energy landscapes or DOS. The energy gap δE is defined as the energy gap between the native state and the average of nonnative states, so δE can be calculated from DOS directly by  . In a structure-based model without nonnative interactions, only topological roughness

. In a structure-based model without nonnative interactions, only topological roughness  exists, and it can be expressed by

exists, and it can be expressed by  , where S is the entropy, which can be directly obtained from DOS, and

, where S is the entropy, which can be directly obtained from DOS, and  is the glassy trapping temperature. With the thermodynamic definition,

is the glassy trapping temperature. With the thermodynamic definition,  is regarded as the temperature at which the configurational entropy of the nonnative states vanishes (46). To get

is regarded as the temperature at which the configurational entropy of the nonnative states vanishes (46). To get  , the distributions of DOS are partitioned into native states and nonnative states (SI Appendix, Figs. S16 and S21). Using the Maxwell relationship

, the distributions of DOS are partitioned into native states and nonnative states (SI Appendix, Figs. S16 and S21). Using the Maxwell relationship  ,

,  can be calculated from the DOS distributions at the ground states of the nonnative states (9, 25, 45, 47–49). In contrast to

can be calculated from the DOS distributions at the ground states of the nonnative states (9, 25, 45, 47–49). In contrast to  , the interfacial binding and monomeric folding temperature are calculated from the corresponding folding and binding heat capacity curves from binding–folding simulations, respectively. Details can be found in Materials and Methods and SI Appendix. To sum up, all of the topography quantities of the effective energy landscapes can be calculated from DOS (SI Appendix, Tables S3–S6).

, the interfacial binding and monomeric folding temperature are calculated from the corresponding folding and binding heat capacity curves from binding–folding simulations, respectively. Details can be found in Materials and Methods and SI Appendix. To sum up, all of the topography quantities of the effective energy landscapes can be calculated from DOS (SI Appendix, Tables S3–S6).

There is a dimensionless quantity, which can describe the topography of the energy landscapes, represented by  (10, 25, 28, 32, 42–45), with the slope, bumpiness, and the size of the funnel quantified by the energy gap, roughness, and entropy, respectively. However, using the quantified whole global energy landscapes, we cannot easily see a clear relationship between different binding–folding scenarios and the whole global energy landscape topography measure

(10, 25, 28, 32, 42–45), with the slope, bumpiness, and the size of the funnel quantified by the energy gap, roughness, and entropy, respectively. However, using the quantified whole global energy landscapes, we cannot easily see a clear relationship between different binding–folding scenarios and the whole global energy landscape topography measure  (SI Appendix, Tables S9 and S10). Since the binding–folding dynamics are controlled by interfacial binding and monomeric folding, the underlying association mechanism should rely on the individual binding and folding energy landscapes. In Fig. 4, we show the association mechanism correlates with the ratio

(SI Appendix, Tables S9 and S10). Since the binding–folding dynamics are controlled by interfacial binding and monomeric folding, the underlying association mechanism should rely on the individual binding and folding energy landscapes. In Fig. 4, we show the association mechanism correlates with the ratio  .

.  and

and  are the effective interfacial binding and monomeric folding energy landscape topography measures, respectively. A large ratio indicates that the interfacial binding energy landscape is more funneled or biased toward the native state than that of monomeric folding. Therefore, the folding of monomer, compared with the interfacial binding, is less favored in the association transitions, leading to the monomer folding upon binding to the partner with a two-state binding mechanism. The isolated monomers of two-state homodimers are unfolded, and can be regarded as IDPs (41), and their global binding–folding energy landscapes are funneled, giving a hint that these monomers realize their function by global conformational flexible binding rather than the well-defined structures. On the contrary, a small ratio indicates that the monomeric folding energy landscape is dominated in the binding–folding dynamics and the monomers tend to fold first, then bind, undergoing a three-state binding mechanism. The global binding–folding energy landscapes of three-state homodimers are strongly dependent on the monomeric folding, indicating that their functions derive from the well-defined structures. Here, in addition to the structural perspective, we show that the topography of the energy landscape is also sufficient to classify the association mechanism. The topographies of the three effective energy landscapes have provided us a way to quantitatively characterize the interplay between folding and function.

are the effective interfacial binding and monomeric folding energy landscape topography measures, respectively. A large ratio indicates that the interfacial binding energy landscape is more funneled or biased toward the native state than that of monomeric folding. Therefore, the folding of monomer, compared with the interfacial binding, is less favored in the association transitions, leading to the monomer folding upon binding to the partner with a two-state binding mechanism. The isolated monomers of two-state homodimers are unfolded, and can be regarded as IDPs (41), and their global binding–folding energy landscapes are funneled, giving a hint that these monomers realize their function by global conformational flexible binding rather than the well-defined structures. On the contrary, a small ratio indicates that the monomeric folding energy landscape is dominated in the binding–folding dynamics and the monomers tend to fold first, then bind, undergoing a three-state binding mechanism. The global binding–folding energy landscapes of three-state homodimers are strongly dependent on the monomeric folding, indicating that their functions derive from the well-defined structures. Here, in addition to the structural perspective, we show that the topography of the energy landscape is also sufficient to classify the association mechanism. The topographies of the three effective energy landscapes have provided us a way to quantitatively characterize the interplay between folding and function.

Nonnative Interactions Modulate the Interplay Between Folding and Binding by the Intrinsic Energy Landscapes.

A previous study (21) has shown that nonnative interactions can roughen the protein folding energy landscapes through the energetic roughness. By investigating the binding and folding topography measures  and

and  with varying strengths of nonnative interactions, we find that these two measures decrease as the nonnative interactions increase. This indicates that the effective binding and folding energy landscapes become less funneled as the nonnative interactions increase (Fig. 5). This shows that increasing the energetic roughness leads to not only bumpier whole global binding–folding energy landscapes but also bumpier individual effective binding and folding energy landscapes.

with varying strengths of nonnative interactions, we find that these two measures decrease as the nonnative interactions increase. This indicates that the effective binding and folding energy landscapes become less funneled as the nonnative interactions increase (Fig. 5). This shows that increasing the energetic roughness leads to not only bumpier whole global binding–folding energy landscapes but also bumpier individual effective binding and folding energy landscapes.

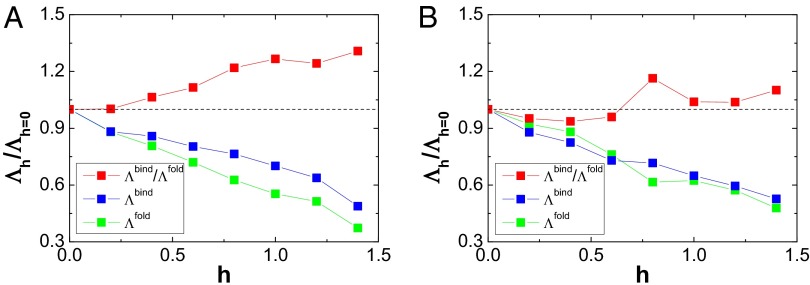

Fig. 5.

The effective energy landscape topography measures, considering strength of nonnative interactions, perturbations  versus

versus  , which corresponds to the pure structure-based model without nonnative interactions, for (A) Arc repressor and (B) Lambda Cro repressor. Red points represent the ratio of

, which corresponds to the pure structure-based model without nonnative interactions, for (A) Arc repressor and (B) Lambda Cro repressor. Red points represent the ratio of  , blue points represent the ratio of

, blue points represent the ratio of  , and green points represent the ratio of

, and green points represent the ratio of  as a function of strength of nonnative interactions. The parameter h modulates the strength of nonnative interactions.

as a function of strength of nonnative interactions. The parameter h modulates the strength of nonnative interactions.

In the details, we can see that the decreasing trends with respect to the increasing strengths of nonnative interactions for  and

and  show different slopes. For the Arc repressor,

show different slopes. For the Arc repressor,  decreases more significantly than

decreases more significantly than  , as the strengths of nonnative interactions increase. However, for the Lambda Cro repressor,

, as the strengths of nonnative interactions increase. However, for the Lambda Cro repressor,  decreases less at the beginning and then more than

decreases less at the beginning and then more than  with increasing nonnative interactions. These features will lead to different roles of nonnative interactions on

with increasing nonnative interactions. These features will lead to different roles of nonnative interactions on  for describing the interplay of the interfacial binding and monomeric folding. For the Arc repressor, the monotonic increasing behavior with respect to nonnative interactions of

for describing the interplay of the interfacial binding and monomeric folding. For the Arc repressor, the monotonic increasing behavior with respect to nonnative interactions of  indicates that nonnative interactions lead the effective binding energy landscapes to contribute more to the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes. In other words, although the nonnative interactions cause the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes to be less funneled, the effect of binding will be more significant in the global binding–folding transitions, hence the realization of functions. For Lambda Cro repressor, this effect is weaker. The results indicate that nonnative interactions will lead the binding to contribute more significantly to the realization of function of two-state homodimers than three-state homodimers. For IDPs, including the isolated monomers of two-state homodimers, it has been found that nonnative intrachain interactions can account for the degree of structural compactness and the change of the overall dimensions (50–54). The disordered globule states of IDPs, formed by nonnative interactions, will certainly increase the energetic roughness and lead to kinetic traps on the folding energy landscapes. The binding of IDPs with remarkable nonnative structural compactness needs to unravel the collapsed region first (55), and this is realized by binding to the their target, resulting in the association mechanism being strongly driven by the interfacial binding, reflected in the binding energy landscapes. Our results are also consistent with a theoretical associative-memory, water-mediated energy model used by Zheng et al. to investigate the different effects of nonnative interfacial interactions participating in the association of these two types of homodimers (56, 57). The nonnative interactions facilitate the binding with respect to folding by stabilizing the on-pathway intermediate for two-state homodimers, in accordance with our effective energy landscapes picture that the nonnative interactions lead to more significant binding over folding. On the contrary, the nonnative interactions form the off-pathway intermediate for three-state homodimers. This is due to the fact that the interfacial nonnative interactions are significantly formed to roughen the binding energy landscapes. In conclusion, the effects of the nonnative interactions in the association are modulated by the underlying binding and folding energy landscapes.

indicates that nonnative interactions lead the effective binding energy landscapes to contribute more to the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes. In other words, although the nonnative interactions cause the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes to be less funneled, the effect of binding will be more significant in the global binding–folding transitions, hence the realization of functions. For Lambda Cro repressor, this effect is weaker. The results indicate that nonnative interactions will lead the binding to contribute more significantly to the realization of function of two-state homodimers than three-state homodimers. For IDPs, including the isolated monomers of two-state homodimers, it has been found that nonnative intrachain interactions can account for the degree of structural compactness and the change of the overall dimensions (50–54). The disordered globule states of IDPs, formed by nonnative interactions, will certainly increase the energetic roughness and lead to kinetic traps on the folding energy landscapes. The binding of IDPs with remarkable nonnative structural compactness needs to unravel the collapsed region first (55), and this is realized by binding to the their target, resulting in the association mechanism being strongly driven by the interfacial binding, reflected in the binding energy landscapes. Our results are also consistent with a theoretical associative-memory, water-mediated energy model used by Zheng et al. to investigate the different effects of nonnative interfacial interactions participating in the association of these two types of homodimers (56, 57). The nonnative interactions facilitate the binding with respect to folding by stabilizing the on-pathway intermediate for two-state homodimers, in accordance with our effective energy landscapes picture that the nonnative interactions lead to more significant binding over folding. On the contrary, the nonnative interactions form the off-pathway intermediate for three-state homodimers. This is due to the fact that the interfacial nonnative interactions are significantly formed to roughen the binding energy landscapes. In conclusion, the effects of the nonnative interactions in the association are modulated by the underlying binding and folding energy landscapes.

Topography of the Whole Global Intrinsic Energy Landscapes Determines the Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Binding–Folding.

The whole global binding–folding energy landscape, which is a combination of binding and folding, describes the global formation of the homodimer. In simplified analytical models, the thermodynamic stability against trapping of the global binding–folding can be explored and linked to the whole global landscape topography measure: , with

, with  (25, 28).

(25, 28).  is the binding transition temperature, which is the transition temperature for binding from the heat capacity curves, whereas

is the binding transition temperature, which is the transition temperature for binding from the heat capacity curves, whereas  is the trapping temperature, at which the homodimer traps at the energy landscape and the kinetics of binding–folding shows glassy behaviors. In kinetics, the mean first passage time

is the trapping temperature, at which the homodimer traps at the energy landscape and the kinetics of binding–folding shows glassy behaviors. In kinetics, the mean first passage time  is calculated and used for describing the binding–folding time, which can be explicitly measured in experiments. In our work, we investigated the thermodynamics and kinetics of 15 homodimers without energetic roughness, as well as two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor with energetic roughness.

is calculated and used for describing the binding–folding time, which can be explicitly measured in experiments. In our work, we investigated the thermodynamics and kinetics of 15 homodimers without energetic roughness, as well as two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor with energetic roughness.

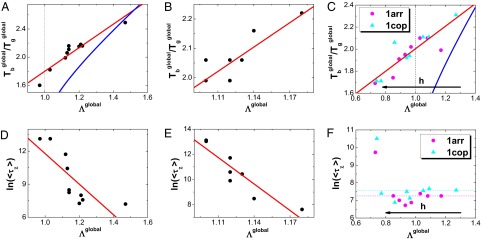

In Fig. 6 A–C, we show that  is monotonically correlated with

is monotonically correlated with  . It demonstrates that a steeper, less rugged, and smaller sized energy landscape will lead to a stronger thermodynamic stability against trapping. We also find that all of the simulated homodimers show

. It demonstrates that a steeper, less rugged, and smaller sized energy landscape will lead to a stronger thermodynamic stability against trapping. We also find that all of the simulated homodimers show  , resulting in the funneled global binding–folding energy landscapes. However, the relationship between

, resulting in the funneled global binding–folding energy landscapes. However, the relationship between  and Λ quantitatively deviated from the analytical expression from the mean field theory mentioned above. This may be due to the fact that the finite size effect and the capillarity of the protein binding–folding are accounted for in the simulations (58, 59). In experimental aspects, the binding transition temperature

and Λ quantitatively deviated from the analytical expression from the mean field theory mentioned above. This may be due to the fact that the finite size effect and the capillarity of the protein binding–folding are accounted for in the simulations (58, 59). In experimental aspects, the binding transition temperature  in dimerization (36) and glassy trapping temperature

in dimerization (36) and glassy trapping temperature  (34, 35) can be explicitly measured. Increasing the energy landscape topography measure

(34, 35) can be explicitly measured. Increasing the energy landscape topography measure  through interactions (local mutations, denaturants, and pH, for examples) is a practical realization of increasing the ratio

through interactions (local mutations, denaturants, and pH, for examples) is a practical realization of increasing the ratio  , which is directly related to the thermodynamic binding–folding stability and the feasibility of protein realizing its function.

, which is directly related to the thermodynamic binding–folding stability and the feasibility of protein realizing its function.

Fig. 6.

The correlation between the whole global landscape topography measure  and thermodynamics as well as kinetics of global binding–folding. The binding transition against glassy trapping temperature

and thermodynamics as well as kinetics of global binding–folding. The binding transition against glassy trapping temperature  correlated with the whole global landscape topography

correlated with the whole global landscape topography  for (A) 10 different-sized homodimers with correlation 0.94, (B) eight similar-sized homodimers with correlation 0.84, and (C) two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor with varying energetic roughness, showing a correlation of 0.88. The blue lines in A, B, and C are the analytical mean field theoretical prediction of the relationship between

for (A) 10 different-sized homodimers with correlation 0.94, (B) eight similar-sized homodimers with correlation 0.84, and (C) two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor with varying energetic roughness, showing a correlation of 0.88. The blue lines in A, B, and C are the analytical mean field theoretical prediction of the relationship between  and

and  . The logarithm of global binding–folding time correlated with the whole global landscape topography

. The logarithm of global binding–folding time correlated with the whole global landscape topography  for (D) 10 different-sized homodimers with correction –0.78, (E) eight similar-sized homodimers with correlation –0.91, and (F) two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor with varying energetic roughness. The red lines in A–E are the linear fits. Because all of the quantities are found to be size scaled (SI Appendix, Figs. S23–S25), the 15 homodimers in the pure structure-based model are divided into different-sized and similar-sized groups to remove the size effect in the underlying correlation between global landscape topography

for (D) 10 different-sized homodimers with correction –0.78, (E) eight similar-sized homodimers with correlation –0.91, and (F) two-state homodimer Arc repressor and three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor with varying energetic roughness. The red lines in A–E are the linear fits. Because all of the quantities are found to be size scaled (SI Appendix, Figs. S23–S25), the 15 homodimers in the pure structure-based model are divided into different-sized and similar-sized groups to remove the size effect in the underlying correlation between global landscape topography  and thermodynamics, as well as kinetics. The parameter h modulates the strength of nonnative interactions and τ is in the unit of simulation time.

and thermodynamics, as well as kinetics. The parameter h modulates the strength of nonnative interactions and τ is in the unit of simulation time.

In Fig. 6 D and E, we show the relationship between binding–folding time  and the whole global binding–folding energy landscape topography

and the whole global binding–folding energy landscape topography  . For the pure structure-based model with only topological roughness (Fig. 6 D and E), the monotonic increasing relationship between

. For the pure structure-based model with only topological roughness (Fig. 6 D and E), the monotonic increasing relationship between  and

and  is clearly shown. This implies that a steeper, smoother, and smaller sized energy landscape funnel will lead to faster binding kinetics. However, for the structure-based model with energetic roughness perturbations, the relationship is not monotonous, with the kinetics accelerating at the beginning and finally decelerating significantly at the small

is clearly shown. This implies that a steeper, smoother, and smaller sized energy landscape funnel will lead to faster binding kinetics. However, for the structure-based model with energetic roughness perturbations, the relationship is not monotonous, with the kinetics accelerating at the beginning and finally decelerating significantly at the small  value end (Fig. 6F). This interesting appearance is due to the fact that the nonnative interactions on one hand can increase the roughness of the energy landscapes, leading to bumpier funnels, and on the other hand can decrease the binding–folding transition barrier height (SI Appendix, Figs. S35 and S41), accelerating the kinetics. In reality, the global binding–folding kinetics is under the dual effects of the nonnative interactions. Therefore, the topography of the whole global binding–folding energy landscape determines the binding–folding kinetics, which is closely related to the efficiency of protein realizing its function.

value end (Fig. 6F). This interesting appearance is due to the fact that the nonnative interactions on one hand can increase the roughness of the energy landscapes, leading to bumpier funnels, and on the other hand can decrease the binding–folding transition barrier height (SI Appendix, Figs. S35 and S41), accelerating the kinetics. In reality, the global binding–folding kinetics is under the dual effects of the nonnative interactions. Therefore, the topography of the whole global binding–folding energy landscape determines the binding–folding kinetics, which is closely related to the efficiency of protein realizing its function.

Temperature Dependence of Kinetics of Binding–Folding Is a Reflection of the Intrinsic Energy Landscapes.

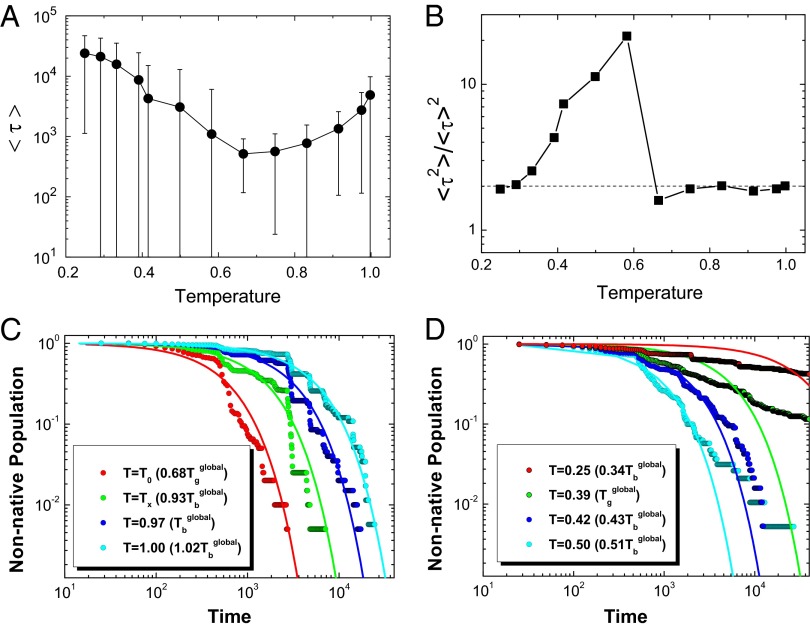

To see how intrinsic energy landscapes influence the global binding–folding kinetics in canonical ensemble, we performed a series of constant temperature kinetic simulations for a two-state homodimer, Troponin C site [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1CTA] with a pure structure-based model. We calculated the binding–folding time  and their corresponding SD at different temperatures (Fig. 7A). A “U-shape” temperature-dependent behavior is observed. At high temperature, the kinetics slows down by the instability of the binding states, whereas at low temperature, the kinetics slows down due to the trapping at the local energy landscape valleys. The results here were consistent with our previous analytical binding theoretical predictions (32). Furthermore, a similar U-shape behavior was found in an experimental investigation for the kinetics of the dimeric formation in response to varying denaturant concentrations by Rumfeldt et al. (33). Therefore, the U-shape kinetic behaviors actually describe the relaxation rate or time as a function of the change of environment measured in terms of temperature and solvent conditions (denaturants). Here, we focus on the kinetic dependence on the temperature, which is the major environmental factor to promote or denature the binding–folding in our simulations. In addition, we investigated the second-order moments of the binding–folding time

and their corresponding SD at different temperatures (Fig. 7A). A “U-shape” temperature-dependent behavior is observed. At high temperature, the kinetics slows down by the instability of the binding states, whereas at low temperature, the kinetics slows down due to the trapping at the local energy landscape valleys. The results here were consistent with our previous analytical binding theoretical predictions (32). Furthermore, a similar U-shape behavior was found in an experimental investigation for the kinetics of the dimeric formation in response to varying denaturant concentrations by Rumfeldt et al. (33). Therefore, the U-shape kinetic behaviors actually describe the relaxation rate or time as a function of the change of environment measured in terms of temperature and solvent conditions (denaturants). Here, we focus on the kinetic dependence on the temperature, which is the major environmental factor to promote or denature the binding–folding in our simulations. In addition, we investigated the second-order moments of the binding–folding time  by plotting them versus different temperatures (Fig. 7B). There is an optimal temperature (T0 = 0.67) at which the binding kinetics is the fastest.

by plotting them versus different temperatures (Fig. 7B). There is an optimal temperature (T0 = 0.67) at which the binding kinetics is the fastest.  is therefore named as optimum kinetic temperature. We can see that when

is therefore named as optimum kinetic temperature. We can see that when  , the ratio is almost a constant, close to 2. Such a small value implies that binding–folding transition events can be self-averaged and the kinetics is Poisson process (60). The binding–folding kinetic population at these temperatures is single exponential in time, which is verified in Fig. 7C. On the other hand, when

, the ratio is almost a constant, close to 2. Such a small value implies that binding–folding transition events can be self-averaged and the kinetics is Poisson process (60). The binding–folding kinetic population at these temperatures is single exponential in time, which is verified in Fig. 7C. On the other hand, when  , with the temperature decreasing, the ratio increases significantly first and then drops close to 2, implying that the binding–folding transition events change from non–self-averaging to self-averaging (i.e., the kinetic process from non-Poisson to Poisson) again. Therefore, the binding–folding kinetic population changes from nonexponential to exponential (Fig. 7D). In theory, this distinct behavior of binding kinetics was investigated and the critical temperature for dividing these two behaviors was named as activated temperature

, with the temperature decreasing, the ratio increases significantly first and then drops close to 2, implying that the binding–folding transition events change from non–self-averaging to self-averaging (i.e., the kinetic process from non-Poisson to Poisson) again. Therefore, the binding–folding kinetic population changes from nonexponential to exponential (Fig. 7D). In theory, this distinct behavior of binding kinetics was investigated and the critical temperature for dividing these two behaviors was named as activated temperature  in protein folding and glasses (61), below and above which there is a dynamical cross-over behavior. In our binding simulations, we also find the existence of

in protein folding and glasses (61), below and above which there is a dynamical cross-over behavior. In our binding simulations, we also find the existence of  and its value is close to

and its value is close to  .

.  can be used for monitoring the behavior of the binding kinetics. Above

can be used for monitoring the behavior of the binding kinetics. Above  , the binding kinetics is only affected by one major barrier, and the distribution will be exponential, whereas below

, the binding kinetics is only affected by one major barrier, and the distribution will be exponential, whereas below  , the binding kinetics is controlled by the trapping at the local energy landscape valleys, and the hopping dynamics of escape from the distributed traps will be nonexponential. It is worth noticing that

, the binding kinetics is controlled by the trapping at the local energy landscape valleys, and the hopping dynamics of escape from the distributed traps will be nonexponential. It is worth noticing that  increases rapidly as the temperature decreases near

increases rapidly as the temperature decreases near  (Fig. 7B). In analogy to random first-order phase transitions in glasses, there is a glass transition temperature here for heteropolymers or proteins,

(Fig. 7B). In analogy to random first-order phase transitions in glasses, there is a glass transition temperature here for heteropolymers or proteins,  , and the spinodal activated temperature

, and the spinodal activated temperature  represents the dynamical cross-over, below which there exists an exponentially large number of statistically trapping states and the dynamics is activated (58, 62, 63). Therefore, the rapid increase is due to the emergence of the large number of trapping states, significantly changing the statistics of the kinetic process from Poisson (exponential distribution) to non-Poisson (nonexponential distribution). In summary,

represents the dynamical cross-over, below which there exists an exponentially large number of statistically trapping states and the dynamics is activated (58, 62, 63). Therefore, the rapid increase is due to the emergence of the large number of trapping states, significantly changing the statistics of the kinetic process from Poisson (exponential distribution) to non-Poisson (nonexponential distribution). In summary,  is a dividing line for the change of the topography and roughness of the underlying energy landscapes from single barrier domination (above

is a dividing line for the change of the topography and roughness of the underlying energy landscapes from single barrier domination (above  ) to multiple distributed barriers (below

) to multiple distributed barriers (below  ). Intriguingly, at the lowest temperature limit, the ratio drops closely to 2 again, implying the kinetics is exponential again. This is shown in Fig. 7D with

). Intriguingly, at the lowest temperature limit, the ratio drops closely to 2 again, implying the kinetics is exponential again. This is shown in Fig. 7D with  . It is due to the fact that the very low temperature can lead the system to trap at certain deep energy minima, and the exponential binding kinetics is again controlled by escaping from the single energy minima. Our results are consistent with the previous theoretical predictions (32).

. It is due to the fact that the very low temperature can lead the system to trap at certain deep energy minima, and the exponential binding kinetics is again controlled by escaping from the single energy minima. Our results are consistent with the previous theoretical predictions (32).

Fig. 7.

Kinetics at different temperatures for Troponin C site (PDB ID code 1CTA). (A) The binding–folding time  as a function of temperature. The error bar represents the SD of the mean value. (B) The second-order moment ratio of the binding–folding time

as a function of temperature. The error bar represents the SD of the mean value. (B) The second-order moment ratio of the binding–folding time  versus temperature. (C) The evolution of nonnative population at different temperatures above the activated dynamical cross-over temperature

versus temperature. (C) The evolution of nonnative population at different temperatures above the activated dynamical cross-over temperature  . (D) The evolution of nonnative population at different temperatures below the activated dynamical cross-over temperature

. (D) The evolution of nonnative population at different temperatures below the activated dynamical cross-over temperature  . The fitting lines in C and D are single exponential. Temperature is in the unit of energy by multiplying Boltzmann constant k, and τ is in the unit of simulation time.

. The fitting lines in C and D are single exponential. Temperature is in the unit of energy by multiplying Boltzmann constant k, and τ is in the unit of simulation time.

Our binding results are similar to the previous folding theory and simulations (32, 45, 49, 61, 64), confirming again that the fundamental laws of binding and folding are analogous due to the similar underlying interactions. In addition, we used a structure-based model without energetic frustrations, so the results of the kinetic behavior and the activated dynamical cross-over temperature  in our simulations are caused by the topological roughness effect, which is different from the mean field theory, in which the energetic roughness dominates. In other words, we showed here that the topological roughness has the same effect as the energetic roughness on the energy landscapes. In addition, we also investigated the temperature-dependent kinetics of the three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor and obtained similar results (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), confirming that our kinetic results are universal.

in our simulations are caused by the topological roughness effect, which is different from the mean field theory, in which the energetic roughness dominates. In other words, we showed here that the topological roughness has the same effect as the energetic roughness on the energy landscapes. In addition, we also investigated the temperature-dependent kinetics of the three-state homodimer Lambda Cro repressor and obtained similar results (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), confirming that our kinetic results are universal.

Conclusions

Quantifying the intrinsic flexible biomolecular recognition energy landscape can give a clear illustration of how the binding–folding proceeds as well as how the protein realizes its function. However, this is still a challenge in both simulations and experiments at this point in time. In our work, using DOS by transforming the distributions from canonical ensemble into microcanonical ensemble, we successfully quantified the topography of the individual effective binding and folding landscapes, as well as the whole global binding–folding energy landscapes for 15 homodimers using a structure-based model with and without energetic roughness. In addition, we calculated three quantities that determine the topography of the underlying energy landscape: energy gap δE, energy roughness ΔE, and entropy S, representing the slope, the bumpiness, and the size of the energy funnel, respectively. Importantly, we quantified energy landscape topography by a measure of the energy gap over the roughness modularized by the entropy  .

.

Using the quantified effective intrinsic binding and folding energy landscape, we successfully subdivided the 15 homodimers into two groups with different association mechanisms, consistent with the analysis from free energy and experimental measurements (37–40). The quantified energy landscapes provide a unique way to solve the long-standing issue of whether the well-defined structure or the conformational flexibility determines the protein’s function. By considering the energetic roughness of the landscapes, we quantitatively investigated the interplay between binding and folding. The nonnative interactions in binding–folding are found to play a role in modulating the underlying mechanism of the protein recognizing and determining its functions.

Using the quantified whole global energy landscapes, the connections between energy landscape topography and thermodynamics, as well as kinetics, were established. In thermodynamics, the strong monotonic correlation between  , which measures the feasibility of the binding–folding, and the energy landscape topography measure

, which measures the feasibility of the binding–folding, and the energy landscape topography measure  is observed, indicating that a deeper, smoother, and smaller funnel will lead to a stronger functional performance and is related to higher binding specificity (65). In kinetics, with a pure structure-based model, the monotonic decreasing relationship between binding–folding time, which measures the efficiency of the binding–folding, and

is observed, indicating that a deeper, smoother, and smaller funnel will lead to a stronger functional performance and is related to higher binding specificity (65). In kinetics, with a pure structure-based model, the monotonic decreasing relationship between binding–folding time, which measures the efficiency of the binding–folding, and  is observed, implying that the increasing of the slope and the decreasing of the roughness as well as the size of the energy landscape lead to faster kinetics, which is related to functions of higher efficiency. However, with adding energetic roughness perturbations, the binding–folding kinetics can be accelerated by moderate strength of nonnative interactions, due to nonspecific attraction in the first recognition step to speeding the association by “fly-casting” mechanism (66). Since the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters can be experimentally measured (34–36), our results can be experimentally tested and provide a way to link the intrinsic energy landscape topography quantities, which are theoretical variables or parameters, to experimental observable quantities such as thermodynamic feasibility (binding transition and glassy trapping temperature) and kinetic accessibility (binding speed).

is observed, implying that the increasing of the slope and the decreasing of the roughness as well as the size of the energy landscape lead to faster kinetics, which is related to functions of higher efficiency. However, with adding energetic roughness perturbations, the binding–folding kinetics can be accelerated by moderate strength of nonnative interactions, due to nonspecific attraction in the first recognition step to speeding the association by “fly-casting” mechanism (66). Since the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters can be experimentally measured (34–36), our results can be experimentally tested and provide a way to link the intrinsic energy landscape topography quantities, which are theoretical variables or parameters, to experimental observable quantities such as thermodynamic feasibility (binding transition and glassy trapping temperature) and kinetic accessibility (binding speed).

Finally, by investigating the temperature-dependent binding behavior of a flexible two-state homodimer with cooperative coupled folding–binding, we found that the results here are similar to that of folding. From statistical analysis of structural characteristics on the monomeric interfaces, the hydrophobic intermolecular interactions are found to be dominant in forming two-state homodimers (41). This is similar to the protein folding case when the hydrophobic effect is considered as the main driving force in the process. Folding can be regarded as self-binding and binding can be regarded as folding without the linkers. Therefore, we demonstrated that the binding and folding are analogous processes through similar underlying driving forces from the energy landscape perspective.

In closing, our methods have provided a way to investigate the thermodynamics and kinetics of protein–protein interactions, as well as the realization of protein functioning, through the intrinsic energy landscape approach. The results are expected to be extended to multiple partner binding and multidomain protein folding (67). Our findings bridge the gap between theories, simulations, and experiments.

Materials and Methods

The intrinsic energy landscape is reflected by DOS, a distribution description of the microcanonical ensemble, which is independent of the temperature. However, the common molecular simulations are performed at the canonical ensemble, making energy landscape unobservable directly. With the transformation between the distribution of microcanonical ensemble and canonical ensemble  , we can obtain DOS using molecular simulations. The structure-based coarse-grained model is used for exploring the underlying energy landscape. In our work, the topological roughness is determined by a pure structure-based model. The pure structure-based model only considers the interactions in the native structure; therefore, the energetic frustration is ruled out, smoothing the energy landscape to only containing topological roughness. To explore the energetic roughness, we incorporated the nonnative interaction, whose strength is expressed by a Gaussian distribution, into the pure structure-based model.

, we can obtain DOS using molecular simulations. The structure-based coarse-grained model is used for exploring the underlying energy landscape. In our work, the topological roughness is determined by a pure structure-based model. The pure structure-based model only considers the interactions in the native structure; therefore, the energetic frustration is ruled out, smoothing the energy landscape to only containing topological roughness. To explore the energetic roughness, we incorporated the nonnative interaction, whose strength is expressed by a Gaussian distribution, into the pure structure-based model.

For thermodynamics, we performed 48 parallel Replica Exchanged Molecular Dynamics simulations for thermodynamic studies (68), and then collected the distributions in each replica, which represented the canonical ensemble at different temperatures. Finally we obtained DOS by converting the distributions of canonical ensemble into microcanonical ensemble using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method algorithm (69) and therefore quantified the topography of the intrinsic energy landscapes. For kinetic analysis, we performed 200 independent constant temperature simulations starting from varying unbound configurations for each homodimer or one homodimer with varying energetic roughness (including the zero energetic roughness). The simulated temperatures are chosen at the temperature when the population of native binding states occupies 80% to guarantee an identical simulation condition for different homodimers (70). In kinetic simulations, we set the maximum of simulation time of each trajectory as  . The trajectories that can reach the native states within

. The trajectories that can reach the native states within  will directly get the first passage time τ. However, there may be some trajectories that cannot reach the native states within

will directly get the first passage time τ. However, there may be some trajectories that cannot reach the native states within  and the data may be missing. Here, we used the Kaplan–Meier nonparametric estimator to calculate the mean first passage time

and the data may be missing. Here, we used the Kaplan–Meier nonparametric estimator to calculate the mean first passage time  and its second-order moment ratio

and its second-order moment ratio  from the censored data (71). Details can be found in SI Appendix.

from the censored data (71). Details can be found in SI Appendix.

It is worth noting that when considering energetic roughness, the topological roughness is assumed to be unaffected by the varying energetic variance. As the topological frustration arises from the structural characteristic in native configuration, a certain degree of change in the nonnative interaction is not supposed to perturb the topological roughness significantly (72). Therefore, the roughness of the energy landscape ΔE is expressed by  , where

, where  and

and  are the topological and energetic roughness, respectively. Simulation and calculation details can be found in SI Appendix and our previous work (21).

are the topological and energetic roughness, respectively. Simulation and calculation details can be found in SI Appendix and our previous work (21).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

X.C. thanks Yong Wang and Feng Zhang for helpful discussions, J.W. thanks the National Science Foundation for support, and X.C. and E.W. acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation of China (Grants 21190040, 11174105, and 91227114) and the 973 Project of China (2009CB930100 and 2010CB933600).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1220699110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fischer E. Einfluss der configuration auf die wirkung der enzyme. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1894;27(3):2984–2993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koshland DE. Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44(2):98–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosshard HR. Molecular recognition by induced fit: How fit is the concept? News Physiol Sci. 2001;16(4):171–173. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.4.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol. 1999;293(2):321–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunker AK, et al. Intrinsically disordered protein. J Mol Graph Model. 2001;19(1):26–59. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uversky VN. Natively unfolded proteins: A point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002;11(4):739–756. doi: 10.1110/ps.4210102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Showing your ID: Intrinsic disorder as an ID for recognition, regulation and cell signaling. J Mol Recognit. 2005;18(5):343–384. doi: 10.1002/jmr.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunker AK, et al. Intrinsic disorder and functional proteomics. Biophys J. 2007;92(5):1439–1456. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Spin-glasses and the statistical-mechanics of protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(21):7524–7528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Intermediates and barrier crossing in a random energy-model (with applications to protein folding) J Phys Chem. 1989;93(19):6902–6915. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leopold PE, Montal M, Onuchic JN. Protein folding funnels—A kinetic approach to the sequence structure relationship. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(18):8721–8725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dill KA, Chan HS. From levinthal to pathways to funnels. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4(1):10–19. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levinthal C. In: Proceedings in Mossbauer Spectroscopy in Biological Systems. Debrunner P, Tsibris J, Munck E, editors. Urbana, IL: Univ of Illinois Press; 1969. pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolynes PG, Onuchic JN, Thirumalai D. Navigating the folding routes. Science. 1995;267(5204):1619–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.7886447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Onuchic J, Wolynes P. Statistics of kinetic pathways on biased rough energy landscapes with applications to protein folding. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;76(25):4861–4864. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks CL, Onuchic JN, Wales DJ. Statistical thermodynamics—Taking a walk on a landscape. Science. 2001;293(5530):612–613. doi: 10.1126/science.1062559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolynes PG, LutheySchulten Z, Onuchic JN. Fast folding experiments and the topography of protein folding energy landscapes. Chem Biol. 1996;3(6):425–432. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveberg M, Wolynes PG. The experimental survey of protein-folding energy landscapes. Q Rev Biophys. 2005;38(3):245–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolynes PG. Recent successes of the energy landscape theory of protein folding and function. Q Rev Biophys. 2005;38(4):405–410. doi: 10.1017/S0033583505004075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, et al. Topography of funneled landscapes determines the thermodynamics and kinetics of protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(39):15763–15768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212842109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frauenfelder H, Sligar SG, Wolynes PG. The energy landscapes and motions of proteins. Science. 1991;254(5038):1598–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1749933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai CJ, Kumar S, Ma BY, Nussinov R. Folding funnels, binding funnels, and protein function. Protein Sci. 1999;8(6):1181–1190. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar S, Ma BY, Tsai CJ, Sinha N, Nussinov R. Folding and binding cascades: Dynamic landscapes and population shifts. Protein Sci. 2000;9(1):10–19. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Verkhivker GM. Energy landscape theory, funnels, specificity, and optimal criterion of biomolecular binding. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(18):188101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.188101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papoian GA, Wolynes PG. The physics and bioinformatics of binding and folding—An energy landscape perspective. Biopolymers. 2003;68(3):333–349. doi: 10.1002/bip.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schug A, Onuchic JN. From protein folding to protein function and biomolecular binding by energy landscape theory. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(6):709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Xu L, Wang E. Optimal specificity and function for flexible biomolecular recognition. Biophys J. 2007;92(12):L109–L111. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(3):197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin RH, Beeson KW, Eisenstein L, Frauenfelder H, Gunsalus IC. Dynamics of ligand-binding to myoglobin. Biochemistry. 1975;14(24):5355–5373. doi: 10.1021/bi00695a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J. Diffusion and single molecule dynamics on biomolecular interface binding energy landscape. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;418(4):544–548. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rumfeldt JAO, Galvagnion C, Vassall KA, Meiering EM. Conformational stability and folding mechanisms of dimeric proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98(1):61–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iben IET, et al. Glassy behavior of a protein. Phys Rev Lett. 1989;62(16):1916–1919. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.62.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reat V, et al. Dynamics of different functional parts of bacteriorhodopsin: H-2H labeling and neutron scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(9):4970–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy GB, Bharadwaj S, Surolia A. Thermal stability and mode of oligomerization of the tetrameric peanut agglutinin: A differential scanning calorimetry study. Biochemistry. 1999;38(14):4464–4470. doi: 10.1021/bi982828s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neet KE, Timm DE. Conformational stability of dimeric proteins—Quantitative studies by equilibrium denaturation. Protein Sci. 1994;3(12):2167–2174. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu D, Tsai CJ, Nussinov R. Mechanism and evolution of protein dimerization. Protein Sci. 1998;7(3):533–544. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levy Y, Wolynes PG, Onuchic JN. Protein topology determines binding mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(2):511–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534828100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy Y, Cho SS, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. A survey of flexible protein binding mechanisms and their transition states using native topology based energy landscapes. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(4):1121–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunasekaran K, Tsai CJ, Nussinov R. Analysis of ordered and disordered protein complexes reveals structural features discriminating between stable and unstable monomers. J Mol Biol. 2004;341(5):1327–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryngelson JD, Onuchic JN, Socci ND, Wolynes PG. Funnels, pathways, and the energy landscape of protein-folding—A synthesis. Proteins. 1995;21(3):167–195. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG, Lutheyschulten Z, Socci ND. Toward an outline of the topography of a realistic protein-folding funnel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;9(8):3626–3630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onuchic JN, LutheySchulten Z, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding: The energy landscape perspective. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48(1):545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]