Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi is an invasive spirochete that can cause acute and chronic infections in the skin, heart, joints, and central nervous system of infected mammalian hosts. Little is understood about where the bacteria encounter the strongest barriers to infection and how different components of the host immune system influence the population as the infection progresses. To identify population bottlenecks in a murine host, we utilized Tn-seq to monitor the composition of mixed populations of B. burgdorferi during infection. Both wild-type mice and mice lacking the Toll-like receptor adapter molecule MyD88 were infected with a pool of infectious B. burgdorferi transposon mutants with insertions in the same gene. At multiple time points postinfection, bacteria were isolated from the mice and the compositions of the B. burgdorferi populations at the injection site and in distal tissues determined. We identified a population bottleneck at the site of infection that significantly altered the composition of the population. The magnitude of this bottleneck was reduced in MyD88−/− mice, indicating a role for innate immunity in limiting early establishment of B. burgdorferi infection. There is not a significant bottleneck during the colonization of distal tissues, suggesting that founder effects are limited and there is not a strict limitation on the number of organisms able to initiate populations at distal sites. These findings further our understanding of the interactions between B. burgdorferi and its murine host in the establishment of infection and dissemination of the organism.

INTRODUCTION

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, is transmitted to mammalian hosts via the bite of an infected Ixodes scapularis tick. Upon entering into a new animal host, the bacteria establish infection at the inoculation site and then quickly disseminate to distal tissues establishing long-term colonization (1–3). In this process, B. burgdorferi encounters multiple potential barriers to infection, including adapting to environmental changes in nutrients, pH, and temperature, breaking through tissue barriers to invasion and dissemination, and evading host immune responses (4–7). Little is currently understood about which barriers have the largest effect on B. burgdorferi survival and growth.

A population bottleneck is an event in which the size of a population is temporarily, stochastically reduced. Bottlenecks during infection have been documented in RNA viruses, parasites, and bacterial pathogens (8–12). They can exist both during movement between hosts and during dissemination within a single host (9, 13, 14). In the environment, bottlenecks can have profound effects on pathogen evolution, shifting populations to favor certain genotypes and eliminating others (15–17). In the laboratory, identifying population bottlenecks can reveal pathways of dissemination and the points where the organisms encounter the strongest barriers to infection (8, 11, 12).

Population bottlenecks experienced by different pathogens during infection vary significantly. Plant RNA viruses experience multiple sequential bottlenecks as the virus migrates contiguously to new leaves (18, 19). In contrast, the dissemination of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is nonlinear. Although there is central pool of bacteria in the mouse intestine, there are multiple pathways of systemic spread, and the populations of Y. pseudotuberculosis in the spleen and liver are distinct from those in the regional lymph nodes in an infected mouse. However, bottlenecks occur during Y. pseudotuberculosis migration along both pathways (11).

As a vector-borne organism, B. burgdorferi may experience population bottlenecks at multiple points in the life cycle: transmission from a tick to a mammalian host during a blood meal, establishment of infection at the tick bite site, colonization of distal tissues, and finally transmission from the infected mammal to a feeding tick. Previous studies exploring population dynamics during B. burgdorferi infection have been done by determining bacterial loads at different time points postinfection (2, 20, 45). However, these types of gross kinetic studies cannot identify the presence of population bottlenecks that occur during infection.

Massively parallel sequencing has been combined with transposon mutagenesis to quantitatively monitor changes in the frequency of a particular insertion within a population in strategies that have been called Tn-seq, In-seq, and high-throughput insertion tracking by deep sequencing (HITS) (21–23). Variations have been developed to study bacterial fitness in in vitro and in vivo models, including Streptococcus pneumoniae growth in vitro, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron intestinal colonization, Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic resistance, and Haemophilus influenzae infection of the lung (21–24). These strategies have not previously been attempted with B. burgdorferi. We developed a method to use Tn-seq to identify population bottlenecks and obtain quantitative data about the populations of B. burgdorferi that coexist during a mouse infection. In this study, we monitored changes in the composition of a mixed population of B. burgdorferi transposon mutants with insertions into the same gene to identify where B. burgdorferi encounters barriers to mouse infection. In addition, we explored the role of host innate immunity, an important factor in determining the outcome of B. burgdorferi infection, in mediating population bottlenecks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth medium.

The transformable, infectious B. burgdorferi B31 clone 5A18NP1 was used for generation of all signature-tagged transposon mutants used in this study. 5A18NP1 is a genetically modified clone in which linear plasmids 28-4 (lp28-4) and lp56 are missing and bbe02, encoding a putative restriction-modification enzyme, has been disrupted (26). All strains used in this study had undergone no more than three subcultures since clone isolation prior to infectivity studies. B. burgdorferi was grown at 37°C in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly II (BSK-II) medium supplemented with antibiotics (200 μg/ml kanamycin and 40 μg/ml gentamicin).

Creation of oppA1 insertion mutants.

The eight B. burgdorferi transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 (T11TC050, T03TC095, T08P01C07, T06TC172, T05TC102, T04TC011, T06TC543, and T05TC551 [mutants A to H, respectively]) were generated as part of a transposon signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) study (Table 1) (27). Briefly, the B. burgdorferi strains were electroporated with signature-tagged versions of the B. burgdorferi transposon vector pGKT using previously described methods (28, 29). pGKT is a modified version of pMarGent in which a kanamycin resistance cassette (flaB::aph1) was inserted in the “backbone” of the vector, outside the himar1-based transposable element, and a flgB::aacC1 gene was inserted within the transposable element (30). Signature-tagged versions of pGKT were constructed by inserting a 7-bp sequence tag between the ColE1 origin and the inverted terminal repeat on the transposable element. Following electroporation, the transformants were incubated in BSK-II medium without antibiotics for recovery overnight and plated on solid BSK-II medium with 200 mg/ml of kanamycin and 40 mg/ml of gentamicin. Colonies were selected and cultured in liquid BSK-II medium until mid-log phase prior to addition of 15% (vol/vol) glycerol and storage at −70°C. The transposon insertion site was determined by inverse PCR or Escherichia coli rescue of circularized HindIII fragments followed by DNA sequencing. In each of the eight insertion mutants used in the study, the transposon is in the forward orientation in a unique site of oppA1.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Mutant abbreviationa | Mutant nameb | Insertion sitec |

|---|---|---|

| A | T11TC050 | 335198 |

| B | T03TC095 | 335334 |

| C | T08P01C07 | 335491 |

| D | T06TC172 | 335793 |

| E | T05TC102 | 335961 |

| F | T04TC011 | 336241 |

| G | T06TC543 | 336406 |

| H | T05TC551 | 336493 |

Name used in this paper.

Designated name from reference 27.

Coordinates of transposon insertion in the B. burgdorferi chromosome.

The plasmid profiles of the oppA1 mutants were determined by a multiplex PCR scheme followed by detection using Luminex FlexMAP technology and compared with that of the parental clone, 5A18NP1 (31). Circular plasmid 9 (cp9) was missing from T11TC050 (A), T04TC011 (F), and T05TC551 (H). Linear plasmid 5 (lp5) was missing from T05TC102 (E) and T05TC551 (H). However, previous studies have shown that neither cp9 nor lp5 is essential for infection of mice (32).

Animal studies.

All procedures involving mice were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Tufts Medical Center. Mice were housed in microisolator cages and provided with antibiotic-free food and water. Female C57BL/6 wild-type mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MyD88−/− mice were provided by Koichi Kobayashi (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) and were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for 12 generations.

For mouse infection, frozen stocks of each individual strain were cultured in BSK-II medium at 37°C overnight. Cell density was determined by dark-field microscopy, and each clone was added in equal cell numbers into a single pool. Cultures were diluted and mixed in BSK-II medium to a concentration of 8 × 105 bacteria/ml. Mice were injected subcutaneously at the base of the tail with 8 × 104 organisms (1 × 104 of each mutant). As a control to account for any differences in in vitro growth, 8 × 104 organisms were cultured in BSK-II broth supplemented with antibiotics.

For time course studies, 15 mice were injected with the same culture, and groups of 5 mice were sacrificed at 3 days, 2 weeks, and 6 weeks postinfection. Skin samples from the injection site and the left ear as well as the heart, knee, and tibiotarsal joints from each mouse were removed under aseptic conditions and cultured individually in 6 ml of BSK-II broth supplemented with antibiotics. In addition, ear punches from the right ear were collected at 2 weeks postinfection from the mice to be sacrificed at 6 weeks postinfection. Ear punches were cultured individually in 6 ml of BSK-II broth supplemented with antibiotics. For experiments with MyD88−/− mice, wild-type and MyD88−/− mice were sacrificed at 2 weeks postinfection. All cultures were checked daily for growth and the concentration determined by dark-field microscopy. When the density of the bacteria in each culture reached between 5 × 107/ml and 1 × 108/ml, the bacteria were centrifuged for 20 min at 3,000 × g and the pellet frozen at −80°C.

Construction and sequencing of libraries.

Genomic libraries for sequencing were constructed as described by Klein et al. (25). Genomic DNA was obtained from the frozen pellets using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer's instructions. An aliquot of the DNA was placed in a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube and sheared by sonication for 2 min (duty cycle, 10 s on and 5 s off; intensity, 100%) using a high-intensity cup horn that was cooled by a circulating bath (4°C) and attached to a Branson 450 Sonifier. To facilitate amplification of the genomic DNA flanking the transposon, cytosine tails (C tails) were added to 1 μg sheared DNA using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (Promega, Madison, WI). The TdT reaction mixture contained 475 μM dCTP and 25 μM ddCTP (Affymetrix/USB Products, Santa Clara, CA) to limit the length of the C tail. The reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C followed by 20 min at 75°C. The DNA was then purified using a Performa gel filtration cartridge (Edge Biosystems). Transposon-containing fragments were amplified in a PCR mixture containing 5 μl DNA from the TdT reaction as the template and primers specific to the ColE1 site on the 5′ end of the transposon (pMargent1, 5′CGGCAAGTTCATCCTTAGGAGACCGGGG3′) and the C tail (olj376, 5′GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG3′). Primer olj376 was added at three times in excess of pMargent1. The reactions were carried out using Easy-A DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with an initial incubation of 2 min at 95°C followed by 24 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 2 min at 72°C followed by a 2-min extension at 72°C. To prepare the DNA for sequencing and amplify the exact transposon-genomic DNA junction, a nested PCR was performed using 1 μl of the original PCR as a template and a primer specific to the transposon end (pMargent2, 5′AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCGGGGACTTATCAGCCAACCTGTTA3′) and an indexing primer (5′CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATNNNNNNGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT3′), containing the specific sequences required for sequencing on an Illumina platform and where NNNNNN represents a six-base-pair barcode sequence allowing samples to be multiplexed in a single sequencing lane. Within an experiment, a unique indexing primer was used for each individual B. burgdorferi culture. Reactions were carried out using Easy-A DNA polymerase with an initial incubation of 2 min at 95°C followed by 15 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 2 min at 72°C followed by a 2-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A majority of the PCR products were between 200 bp and 600 bp. The libraries made from each culture were then pooled at equal concentrations. The pooled libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II at the Tufts University High-Throughput DNA Sequencing Core as 50-bp single-end reads using the custom sequencing primer pMargent3 (5′ACACTCTTTCCGGGGACTTATCAGCCAACCTGTTA ′) and the standard Illumina index primer.

Data analysis.

Image analysis, base calling, and base call quality are generated automatically during the sequencing run with Illumina Real Time Analysis (RTA) 1.13.48.0 software. Sequenced reads were split according to barcode sequence with the Illumina Casava 1.8.2 pipeline to generate a fastq file for each sample. The number of sequence reads obtained from the culture of each tissue ranged from 3.5 × 106 to 6.3 × 106, with an average of 4.8 × 106 reads. Subsequent data analysis was done using the Galaxy platform (33–35). The C tail was removed from the sequence reads, and reads shorter than 30 bp were discarded. The remaining reads were filtered for quality. Reads for which 90% of the cycles did not have a quality of greater than 15 were discarded. The remaining reads were aligned to the B. burgdorferi B31 genome using Bowtie with its default settings. A custom script was then used to compile the resulting SAM alignment file into a list of individual insertion sites with the number of reads aligned to each site.

Statistics.

The sequencing data comparing the frequencies of the individual mutants were nonparametric. Correlation of population composition between samples was assessed by determining the Spearman correlation coefficient. Differences in the number of high- and low-frequency mutants were assessed using Mann-Whitney tests. Significance for all was defined by a P value of ≤0.05.

RESULTS

High-throughput sequencing to study Borrelia burgdorferi during mouse infection.

The basis of Tn-seq is to use massively parallel sequencing to determine the frequency of individual transposon mutants within a population (23). Lin et al. have created a library of defined transposon mutants of B. burgdorferi (27). We infected mice with a mixed population of transposon mutants from this library and used Tn-seq to monitor changes in the composition of the population as the infection progressed. To minimize changes in population composition due to differences in infectivity, we used a set of eight transposon mutants with insertions in different sites of a single gene, oppA1, which encodes oligopeptide permease 1 (OppA1). OppA1 is a periplasmic binding substrate for the oligopeptide permease OppA (36, 37). The gene is located on the chromosome upstream of two genes encoding alternate substrate binding proteins, oppA2 and oppA3. Expression of the three genes occurs through independent transcription (38). It has previously been shown that strains of B. burgdorferi lacking oppA1, oppA2, and/or oppA3 have no growth defects in vitro and no attenuation of infectivity in mice, likely due to functional redundancy between the OppA proteins (27, 37). The DNA sequences of the genomic DNA flanking the transposon in each of the oppA1 insertions mutants could be easily differentiated from each other. The eight strains are referred to as mutants A through H (Fig. 1A).

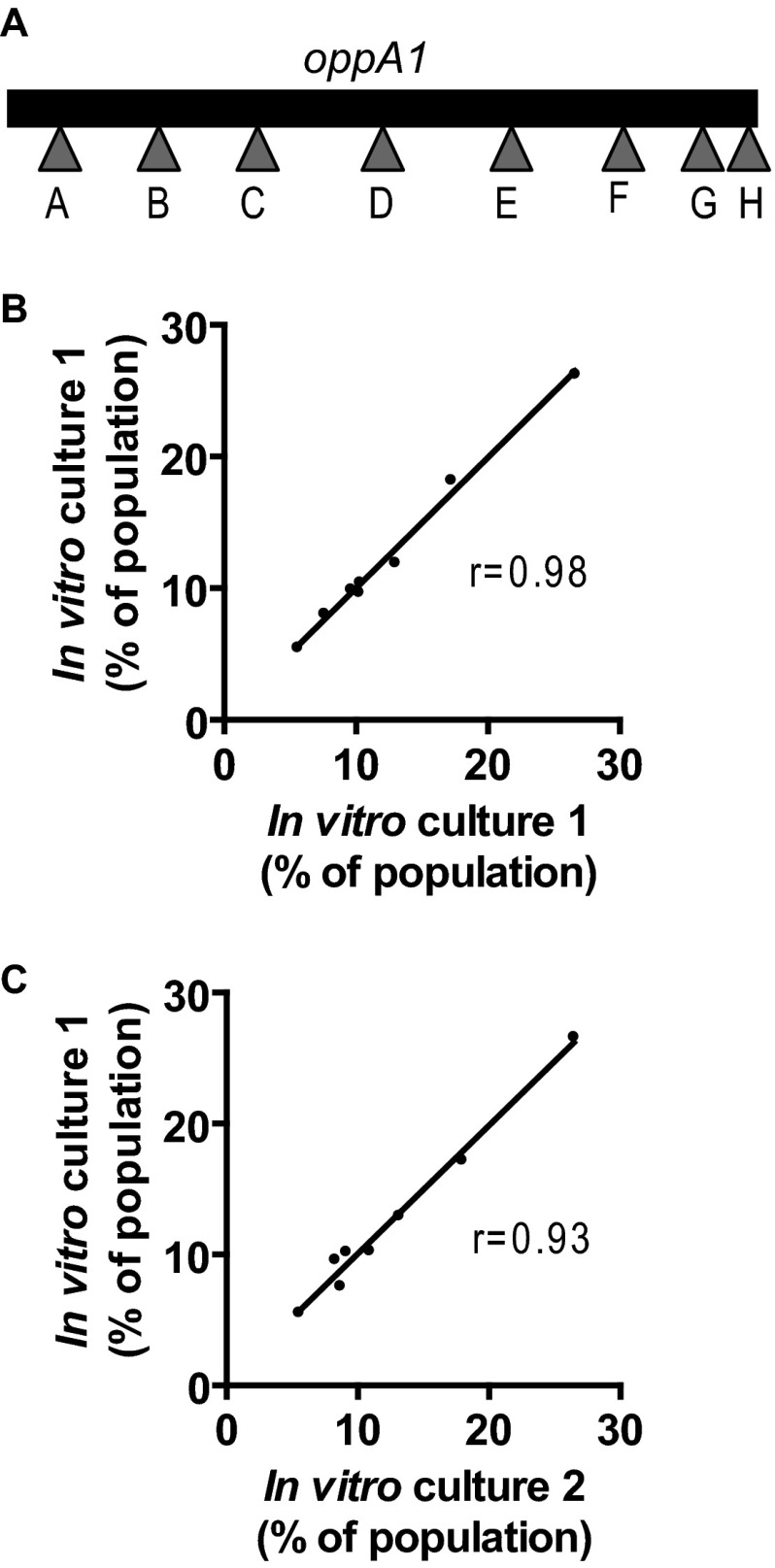

Fig 1.

Reproducibility of the Tn-seq technique. (A) Locations of the transposon insertions in oppA1 in the eight mutants (A to H) used in the experiments. (B) Technical replicate comparing the sequencing data from two sequencing libraries made from the same in vitro culture. (C) Biological replicates comparing the sequencing data from two independent in vitro cultures. To start the in vitro cultures, the eight transposon mutants were grown individually to mid-log phase in BSK-II medium. The mutants were then mixed. The mixture was split into two separate cultures, and the bacteria were grown to late exponential phase. Genomic DNA was prepared from both cultures. Correlation between the samples was assessed by Spearman's correlation coefficient.

To validate Tn-seq for use in B. burgdorferi, biological and technical replicates were performed using mixed in vitro cultures of the eight oppA1 mutants. When tested individually in vitro, no growth defects were observed in any of the mutants (data not shown). For the Tn-seq, individual cultures of each mutant were mixed at known concentrations. Biological replicates were performed by dividing the mixture into two and growing independent cultures for 4 days. Libraries for sequencing were generated from each of the cultures. Technical replicates were performed by preparing two sequencing libraries from a single genomic DNA isolation. The frequencies obtained for each mutant from the sequencing data agreed with the frequency of each mutant in the original mixed culture. Reproducibility between the technical and biological replicates was high (Fig. 1B and C). This confirmed the accuracy and reproducibility of Tn-seq for determining the relative frequency of individual B. burgdorferi mutants within a mixed population.

For the mouse studies, the oppA1 insertion mutants were mixed in equal amounts. The 50% infectious dose (ID50) of B. burgdorferi has been reported to be between 83 and 8,000 organisms (26, 39–41). To ensure that each strain was present at a sufficient dose to establish infection, mice were inoculated with 1 × 104 bacteria of each insertion, for a total dose of 8 × 104. A portion of the inoculum was diluted and passaged in vitro to confirm that any changes in the composition of the population following mouse infection were not due to a general growth defect. At 3 days, 2 weeks, and 6 weeks postinfection, groups of infected mice were sacrificed and tissues commonly associated with Lyme disease, the tibiotarsal joints, knees, hearts, and skin at the inoculation site, were excised and cultured in BSK-II medium. At 3 days postinfection, B. burgdorferi had not disseminated and was detected only at the inoculation site of the mice, with the exception of one knee sample. By 2 weeks postinfection, the bacteria had disseminated throughout the infected mice and could be detected in multiple tissues. At 6 weeks postinfection, bacteria could still be detected in all tested organs (Table 2). Organ culture expanded the population of the bacteria used to create the sequencing library, thus increasing the limit of detection for identifying minor members of the population. Furthermore, this growth step reduced the amount of eukaryotic DNA in the sample, which could decrease the efficiency of the library preparation. However, as a result, direct measurement of total bacterial loads in the tissues could not be performed. Sequencing libraries were prepared from the organ cultures when the bacteria reached late exponential phase. B. burgdorferi populations from the original inoculum mix, the passaged cultures, and the organ cultures were subjected to Tn-seq. Similar to the in vitro culture results, reproducibility was high in technical replicates from the organ cultures (data not shown).

Table 2.

Dissemination of B. burgdorferi during infection

| Length of infection | No. of organ cultures positive/no. of mice tested |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculation site | Ear | Heart | Right tibiotarsal joint | Right knee | Left tibiotarsal joint | Left knee | |

| 3 days | 5/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 |

| 2 wk | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 6 wk | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

Bacterial survival during the initiation of infection.

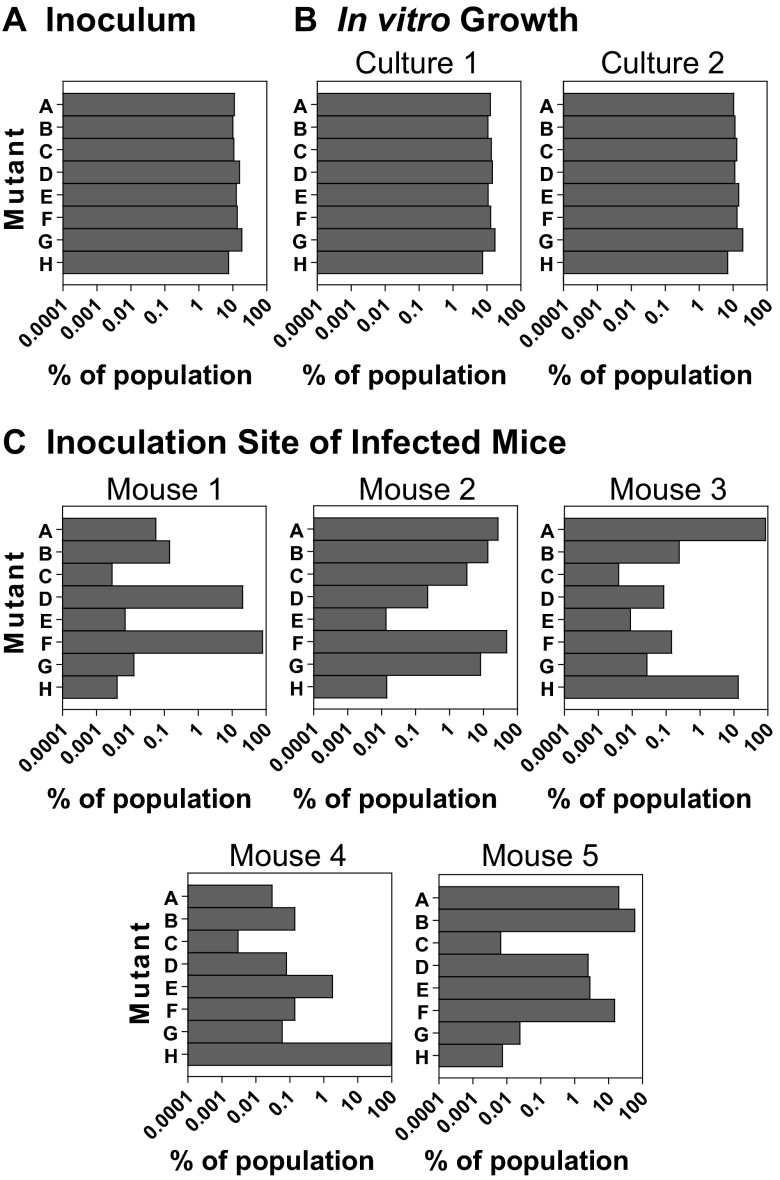

The percentage of each mutant in the inoculum as measured by Tn-seq was between 7.6% and 18.4% (Fig. 2A). In in vitro cultures made from the inoculum, the frequency of the mutants did not significantly change after 4 days of growth, ranging from 6.9% to 19.4% (Fig. 2B). However, at 3 days postinfection, there was a significant shift in the composition of the population in all of the mice. Although all mutants could be detected at the inoculation site in each of the mice, there were now substantial differences in the frequency of the mutants. Demonstrating the sensitivity of the Tn-seq technique, we were able to reproducibly detect individual mutants that were present at as low as 0.004% of the population (Fig. 2C). Four of the five mice tested had a single dominant mutant that represented over 50% of the population. This was most dramatic in mouse 4, where a single mutant, H, comprised >95% of the population. In each mouse, there were only one to four high-frequency mutants (>5.0% of the population) and at least two mutants at a low frequency (<0.05% of the population) (Fig. 3). There was no correlation between the prevalence of a mutant in the input and the populations recovered from the mice (by Spearman correlation coefficient). For example, G was the most common mutant in the inoculum (18.4%) but was not the most dominant mutant isolated from any of the mice and made up less than 0.05% of the population in three of the mice (Fig. 2A and C). This result at 3 days postinfection suggests that during B. burgdorferi infection, there is a population bottleneck at the site of inoculation and a significant portion of the population is lost.

Fig 2.

Changes in population composition early in infection. Eight transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 were grown to mid-log phase in BSK-II medium. The mutants were then mixed in equal amounts to form an inoculum. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected by needle injection with 8 × 104 organisms subcutaneously at the base of the tail. The mice were sacrificed at 3 days postinfection, and the skin at the inoculation site was excised and cultured in BSK-II medium. A total of 8 × 104 organisms from the inoculum were also cultured directly in vitro for the same amount of time as the organ cultures. Libraries for sequencing were made from a genomic DNA isolation from the inoculum (A), from two independent in vitro cultures (B), and from the mice infected for 3 days (C) and sequenced. Each chart shows the data obtained from a single culture or mouse. The bars in each chart represent the eight transposon mutants.

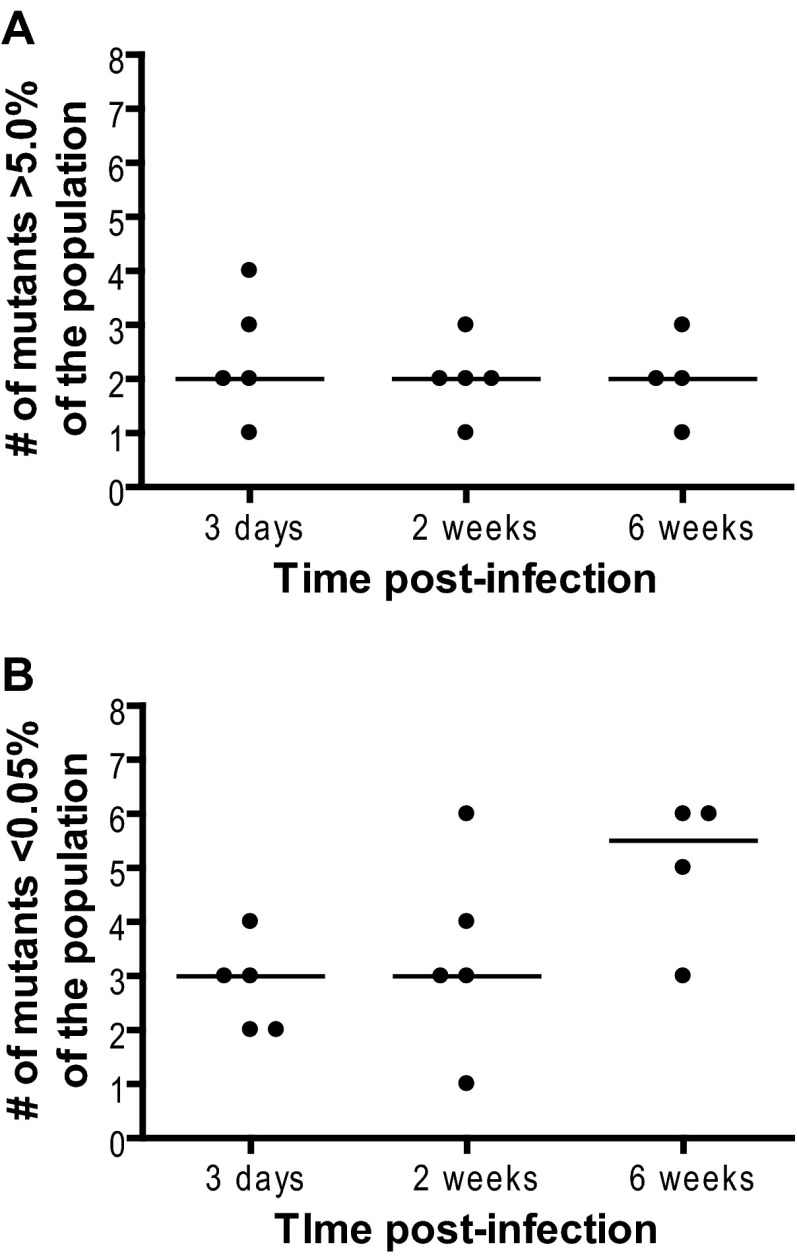

Fig 3.

Numbers of high- and low-frequency mutants in the population at the inoculation site. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with an equal mixture of eight transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 as described for Fig. 2 and sacrificed at day 3, week 2, and week 6 postinfection. The number of high-frequency mutants comprising greater than 5.0% of the population (A) and the number of low-frequency mutants comprising less than 0.05% of the population (B) recovered from the inoculation site of each mouse were determined. Each dot represents the data from one mouse. The line represents the median of the values. Data were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test. No statistically significant differences exist between groups.

Bacterial survival during dissemination and colonization.

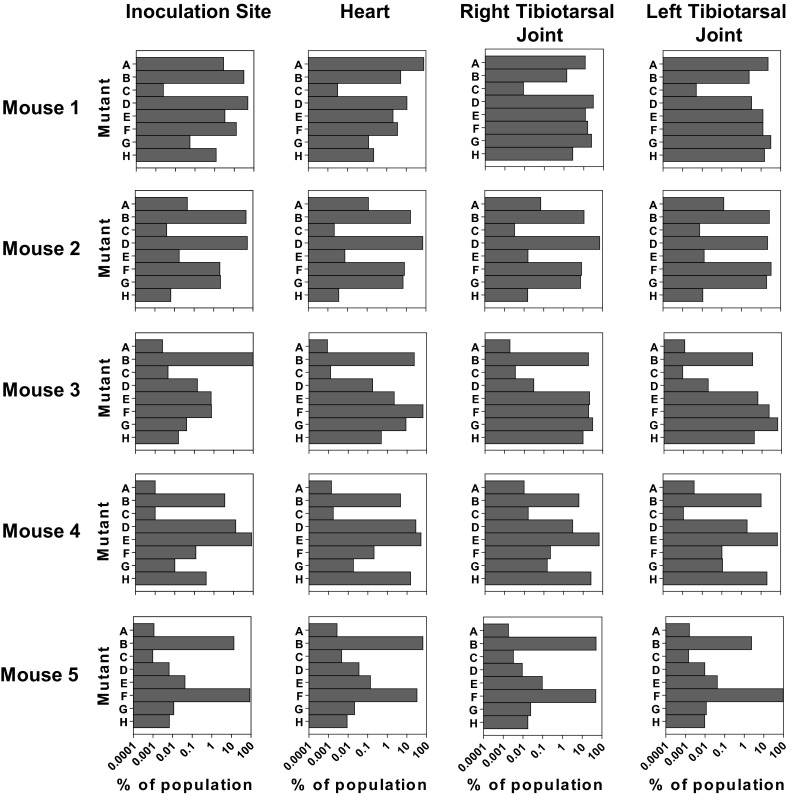

It has been previously shown that B. burgdorferi disseminates from the inoculation site to distal tissues in mice between 1 and 2 weeks postinfection (3). We examined the populations recovered at 2 weeks postinfection from the inoculation site, heart, and tibiotarsal joints. The heart and joints were chosen because they represent tissues where Lyme disease pathology is frequently observed (3, 42). At the inoculation site, we compared the distribution of mutants at this time point to that at 3 days postinfection. All of the mutants could be detected at the inoculation site in each of the mice, and there was a similar distribution of mutants at the two time points (Fig. 3 and 4). If there was additional loss of bacteria from the population between the two time points, mutants would be eliminated from the population and/or the high-frequency mutants would become even more dominant. As such, the results suggest that the B. burgdorferi organisms that survive the initial stage of infection at the inoculation site do not encounter any strong barriers that impair the ability of the bacteria to survive and replicate between 3 days and 2 weeks postinfection.

Fig 4.

Population composition following dissemination. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with an equal mixture of eight transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 as described for Fig. 2. Mice were sacrificed at 2 weeks postinfection, and the skin at the inoculation site, tibiotarsal joints, and hearts were collected and cultured in BSK-II medium. Libraries for sequencing were made from the cultures of each tissue. Each row shows the data from a single mouse. Each chart shows the data obtained from a single tissue. The bars in each chart represent the eight transposon insertion mutants.

In contrast to the large variation in the frequency of individual mutants in a single mouse, which could vary over 1,000-fold relative to the inoculum, when the data from all of the mice are analyzed in aggregate as a single population, with the exception of mutant C, the frequency of each individual mutant did not vary by greater than 2.2-fold relative to the inoculum. As the transposon mutants all contained insertions in the same gene, we believe that the fitness defect of mutant C is due to plasmid loss in the culture used to prepare the inoculum. The B. burgdorferi genome contains 21 plasmids which have been shown to be susceptible to loss during in vitro growth, potentially affecting mouse infectivity (43). Alternatively, it is possible there was a secondary-site mutation in this strain. Overall, this suggests that differences in population composition between mice, with the exception of mutant C, are due to stochastic loss of bacteria due to the bottleneck rather than to differences in bacterial fitness.

A founder effect is a type of population bottleneck that occurs when infections at a new site are initiated by only a few organisms, resulting in a disproportionate representation of these genotypes in the colonizing population relative to the original population. If there were strong founder effects during the dissemination of B. burgdorferi to distal tissues, there would be a loss of diversity at the distal organs relative to the inoculation site. Furthermore, if the bacteria migrated via a specific pathway (i.e., from the inoculation site to the heart and then to the tibiotarsal joints) and there were strong founder effects during the colonization of the tissues, there would be an increasing loss of diversity as the bacteria moved to later sites. In the B. burgdorferi-infected mice, all of the mutants were observed in each tissue tested (Fig. 4). Although the exact percentages were not the same between all of the distal tissues, the composition of the B. burgdorferi population in each tissue was relatively representative of the populations of B. burgdorferi in all tissues within individual mice. This is reflected in the Spearman correlation coefficients. There was a significant correlation in mutant frequencies between all distal sites within four of the five mice tested (Table 3). In the only mouse without significant correlation in all distal tissues (mouse 1), the inoculation site and heart were still significantly correlated. Notably, there was a more even distribution of mutants in this mouse (Fig. 4). As the Spearman correlation coefficient for nonparametric data is based on rank order of variables, a more even distribution may have affected the significance of the results. Overall there do not appear to be strong founder effects influencing the composition of the disseminated B. burgdorferi populations or a strict limitation on the number of organisms able to found populations at distal sites.

Table 3.

Correlation of mutant frequencies in different tissues

| Mouse | Spearman correlation coefficienta for mutant frequencies in: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculation site vs heart | Inoculation site vs right tibiotarsal joint | Inoculation site vs left tibiotarsal joint | Heart vs right tibiotarsal joint | Heart vs left tibiotarsal joint | Right tibiotarsal joint vs left tibiotarsal joint | |

| 1 | 0.76* | 0.40 | −0.29 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.43 |

| 2 | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.83* | 1.00* | 0.90** | 0.90** |

| 3 | 0.86* | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.81* | 0.79* | 0.93** |

| 4 | 0.97** | 0.90** | 0.87** | 0.93** | 0.88** | 0.95** |

| 5 | 0.88** | 0.95** | 0.98** | 0.93** | 0.93** | 0.93** |

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

Although the rank order of the mutants was correlated between tissues, on average, the population recovered from the inoculation site contained lower numbers of high-frequency mutants than those from the heart and tibiotarsal joints (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.03 and 0.02, respectively). Sampling error due to lower bacterial loads in the inoculation site than in the heart and tibiotarsal joints could result in a skewed distribution. However, the detection of all mutants at the inoculation site argues against this hypothesis, since insufficient sampling would likely lead to complete loss of detection of mutants.

Population composition during later stages of infection.

In the absence of antibiotic treatment, mice remain infected with B. burgdorferi for life. However, B. burgdorferi loads decline significantly after 2 to 4 weeks following the development of an adaptive immune response (2, 3, 20). Related to this drop in bacterial load, diversity decreased at the inoculation site at 6 weeks postinfection relative to the earlier time points. The median frequency of the most common mutant trended upward as the length of the infection increased. At 3 days and 2 weeks postinfection, it was 74.1% and 73.7%, respectively, while at 6 weeks, it was 84.0%. The number of low-frequency mutants increased in a majority of the mice. Five or six mutants each constituted less than 0.05% of total population in three of the four mice tested (Fig. 3). In contrast to the case at earlier time points, some mutants were lost from the populations recovered from tissues at 6 weeks postinfection. Mutant C was completely absent from all of the samples. Mutant A was observed only in mouse 1 and mouse 3 and constituted less than 0.2% of the population (Fig. 5).

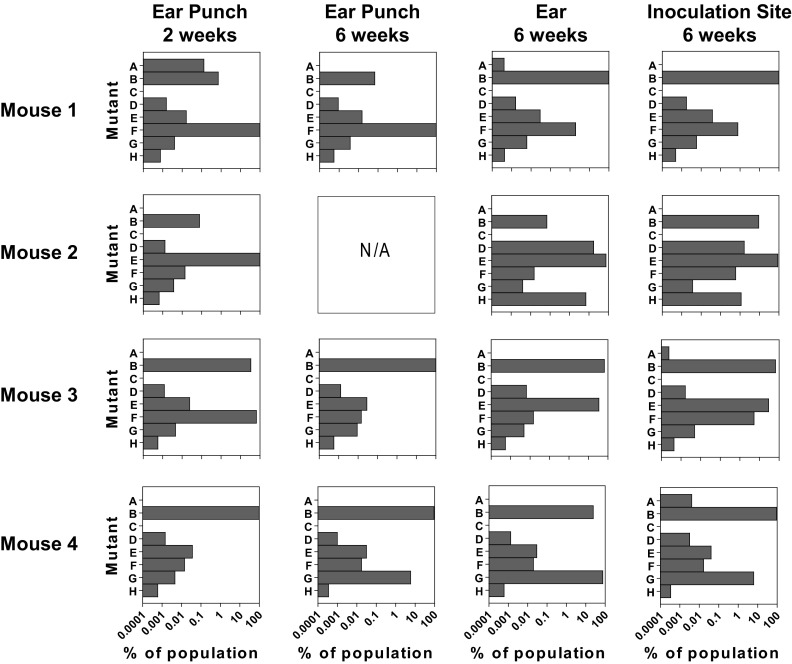

Fig 5.

Population composition in mice over time. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with an equal mixture of eight transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 as described for Fig. 2. Three-millimeter ear punches from the right ear were taken at 2 weeks postinfection. The mice were sacrificed at 6 weeks postinfection, and the skin at the inoculation site, the entire left ear, and a second 3-mm ear punch from the right ear were collected. All tissue samples were cultured in BSK-II medium. Libraries for sequencing were made from each culture. Each row shows the data from a single mouse. Each chart shows the data obtained from a single tissue. The bars in each chart represent the eight transposon insertion mutants. N/A, sequence data from this sample were not available.

To determine whether the composition of the population is stable or fluctuates with various dominant mutants, we obtained serial tissue samples over time. As we cannot study the populations at the inoculation site or internal tissues over time in a single mouse, we tested ear punches taken from right ears of infected mice at 2 and 6 weeks postinfection. In six of the seven ear punches examined, a single mutant represented >90% of the population (Fig. 5). Due to the small size of the ear punches, the overwhelming dominance of a single clone at both time points could be due to sampling error. By comparison, when testing the whole left ear, only one of the mice had a mutant that constituted >90% of the population. Overall, the dominant clone remained constant as the infection progressed. The mutant present at >90% matched between the two time points in the ear punches of two of the three mice tested. In mouse 3, there were two high-frequency mutants at 2 weeks postinfection, B and F (34.0 and 66.0% of the population, respectively), and mutant B was present at 99.95% at 6 weeks. When comparing across all mutants, the population in the whole ear at 6 weeks postinfection is significantly correlated to the populations at the inoculation site and both ear punches except for the ear and 2-week ear punch in mouse 3 (Spearman correlation coefficient for mouse 3 ear versus 2-week ear punch, r = 0.63 [P = 0.09]; all other tissue comparisons, r = 0.74 to 0.98 [P < 0.05]). Thus, as the infection progresses, the high-frequency mutants originally colonizing a tissue remain relatively constant, although the minor mutants may be lost.

Effect of innate immunity on the population bottleneck.

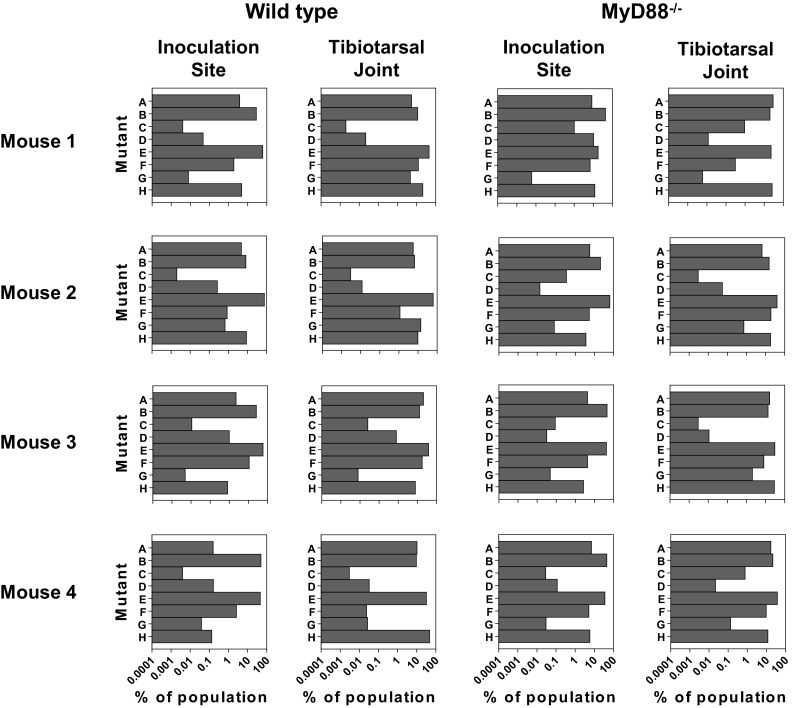

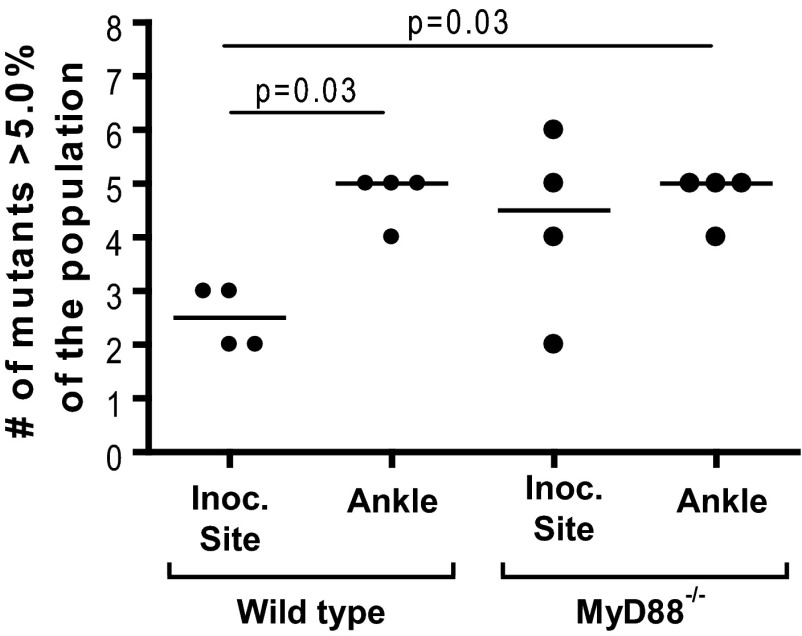

To explore the role of innate immunity in the population bottleneck, we repeated the experiment in mice lacking functional MyD88 (MyD88−/−). At 2 weeks postinfection, the B. burgdorferi populations from the inoculation site and one tibiotarsal joint in wild-type and MyD88−/− mice were examined. The results indicate that similar to the case for the wild-type mice, there was a population bottleneck at the inoculation site of the MyD88−/− mice. Some of the mutants in the population at the inoculation site decreased in frequency over 1,000-fold relative to the inoculum (Fig. 6). However, the magnitude of the bottleneck was less severe in the MyD88−/− mice, and overall there was a more even distribution of mutants. In the wild-type mice, the number of high-frequency mutants in the B. burgdorferi populations recovered from the inoculation site was significantly lower than that in the populations recovered from the tibiotarsal joint (P = 0.03, Mann-Whitney test). This difference was not present in the MyD88−/− mice. A majority of the MyD88−/− mice had four or more high-frequency mutants at the inoculation site (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the frequency of the most common mutant at the inoculation site was less than 50% in three of the MyD88−/− mice but more than 50% in all four of the wild-type mice (Fig. 6). These data suggest that although innate immunity does not play the primary role in the generation of the bottleneck, it does play a role in the severity of the bottleneck at the site of infection. The difference between the wild-type mice and the MyD88−/− mice was less pronounced in the tibiotarsal joints. The median number of high frequency mutants was the same in both groups of mice (Fig. 7). However, the frequency of the most common mutant ranged from 39.0% to 62.5% in wild-type mice and from only 22.0% to 40.0% in MyD88−/− mice, suggesting that there may be a more even distribution of mutants in MyD88 deficient mice in this tissue as well, although the difference is not statistically significant (Fig. 6) (Mann-Whitney test). One explanation for these data may be that the most significant role of innate immunity is in controlling infection at early time points postinfection. As the skin is the first organ exposed to B. burgdorferi and the cutaneous inflammatory response is the initial phase of Lyme disease, innate immunity may have a larger role in determining the outcome of infection in this tissue. At later time points, when the bacteria have disseminated, the role of the innate immune response may be supplanted by adaptive immunity, which has been shown to be independent of MyD88 (44).

Fig 6.

Population composition in the absence of innate immune responses. Wild-type and MyD88−/− C57BL/6 mice were infected with an equal mixture of eight transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 as described for Fig. 2. The mice were sacrificed at 2 weeks postinfection, and the skin at the inoculation site and a tibiotarsal joint were collected and cultured in BSK-II medium. Libraries for sequencing were made from the cultures of each tissue. Each row shows the data from a single mouse. Each chart shows the data obtained from the sequencing of a single tissue. The bars in each chart represent the eight transposon insertion mutants.

Fig 7.

Effect of innate immunity on the number of high-frequency insertions in the population. Wild-type and MyD88−/− C57BL/6 mice were infected with an equal mixture of eight transposon mutants with insertions in oppA1 as described for Fig. 2. The number of high-frequency mutants comprising greater than 5.0% of the population recovered from the inoculation site and right tibiotarsal joint at 2 weeks postinfection was determined. Each dot represents the data from one mouse. The line represents the median of the values. Data were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed a Tn-seq assay to use massively parallel sequencing to study B. burgdorferi pathogenesis. This technology allowed us to quantitatively measure the frequencies of individual B. burgdorferi mutant strains within a mixed population at multiple stages of a mammalian infection. This provided significant advantages over previous studies on B. burgdorferi population dynamics that were limited to measuring fluctuations in population size (2, 20, 45).

Overall, the results demonstrate that B. burgdorferi is a highly successful pathogen that, after surviving a population bottleneck at the site of inoculation, is able to spread throughout a mammalian host relatively unimpeded in order to establish long-term infection. There are no additional bottlenecks or significant barriers to dissemination and colonization of distal sites. Minor mutants constituting 0.004% of the population were maintained in the acute phase of infection. At 2 weeks postinfection, all of the mutants were present in all tissues examined. The lack of founder effects during the colonization of distal sites suggests that multiple bacteria reach distal tissues and are able to colonize a given site. This laboratory observation is compatible with what is observed in the environment and in the clinic. Although experimental studies on B. burgdorferi are frequently carried out using a single strain, field studies have shown that mixed infections with different B. burgdorferi genotypes occur in ticks and mammalian reservoir hosts (46–49). In humans, different strains have been isolated from individual Lyme disease patients (50, 51). The observed lack of host barriers to dissemination in mice may contribute to the frequency of heterogeneous infections observed in environmental studies.

In the wild, genetic variation is an important factor in B. burgdorferi virulence. Environmental strains of B. burgdorferi can vary in plasmid content and gene sequence (50, 52–55). Specific genotypes have been associated with particular manifestations of Lyme disease and with dissemination (56–58). However, the results of this study suggest that in addition to genotype, stochastic forces are involved in determining the outcome of B. burgdorferi infection. The presence of a population bottleneck at the onset of infection emphasizes the significant role played by factors unrelated to bacterial fitness. This is an important consideration for future studies of B. burgdorferi virulence determinants using the mouse model of infection, particularly those using competition assays with multiple strains. Virulence phenotypes of B. burgdorferi strains may be missed or characterized incorrectly due to loss of the strain by stochastic killing.

Innate immunity plays a significant role in controlling B. burgdorferi infection. The Toll-like receptor (TLR) adapter molecule MyD88 is a critical component of the innate immune response to B. burgdorferi (44, 59–61). Mice lacking MyD88 have a severe defect in controlling the bacterial burden despite the development of B. burgdorferi-specific antibodies (44, 59). When innate immunity is impaired, the magnitude of the population bottleneck at the site of infection is reduced. There is greater diversity in the bacterial populations at both the inoculation site and the tibiotarsal joints of infected mice. If the bottleneck was due solely to bacterial adaptation, a similar portion of the bacteria would be lost at the inoculation site in both groups of mice and the level of diversity would be the same in the wild-type and the MyD88−/− mice. The only difference would be an increase in bacterial load in the MyD88−/− mice.

However, despite the overall importance of innate immunity during B. burgdorferi infection, the bottleneck at the site of inoculation is not completely eliminated in the MyD88−/− mice. In addition to host factors, bacterial adaptation may be an important factor in survival. At the time of inoculation, there may be differences in the ability of individual bacteria within the population to adjust to growth conditions in the host, potentially due to differences in gene expression and regulation, epigenetic phenomena, or exposures to varying microenvironments. The bacteria that are unable to rapidly adapt to the new environment may not survive, resulting in the observed population bottleneck.

One important caveat to our experiments is that all infections were performed by needle inoculation rather than through tick transmission as would occur in the environment. This may result in differences in bacterial gene expression and inoculation dose (62). Differences in cell surface expression of lipoproteins may affect the severity of the bottleneck. Furthermore, the mice were inoculated with a much higher dose of organisms than would be expected during tick transmission. Though bacterial loads can be greater than a million in the tick midgut during feeding, only several hundred successfully traverse the gut epithelium into the hemocoel, and an even smaller number survive tick immune defenses and migrate to the tick salivary gland for transmission to the mammal (63). While many of the observations about loss of bacteria may hold true on a smaller scale for lower inoculums delivered by tick bites, it is important to note that the presence of the vector in delivering the organism may itself alter interactions at the inoculation site. When mammalian hosts are infected via a tick bite in the environment, there are various compounds in the tick saliva that suppress host immune responses, including inhibition of the complement cascade, impairment of phagocytic cell function, and repression of cytokine production (64–67). Under these immunosuppressive conditions, the innate immune system might have less of an effect on the population bottleneck and be more focused on the control of bacterial load following the initial bacterial loss. Although this study focused on interactions between B. burgdorferi and a murine host, future studies of population dynamics in B. burgdorferi during tick transmission would provide insight into arthropod-mammal interactions.

Once infection is established, infections by needle inoculation and tick inoculation are thought to follow similar paths, particularly during dissemination and in later stages of infection, after the development of adaptive immune responses. In the later phase of infection, multiple mutants are still found in each tissue, but some mutants within the original population are now absent. This is presumably due to an overall decrease in bacterial loads, resulting in the loss of minor populations while the dominant mutants remain the same in the acute and persistence phases of infection. A similar phenomenon is observed during infection by another vector-borne pathogen, Trypanosoma brucei. T. brucei is a protozoan parasite transmitted by the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.) that establishes a persistent infection in mice. When mice were infected with a mixed population of T. brucei mutants, the dominant mutants in the blood remained constant despite fluctuations in parasite load between 1 and 7 weeks postinfection (9).

The sensitivity of Tn-seq in our study, with reliable detection of mutants comprising as little as 0.004% of the population, suggests that Tn-seq can be used as a method for identifying differences in relative fitness within pools of transposon mutants. Despite our attempts to use equally infectious mutants by using a set of transposon mutants with insertions in the same gene, the strains were not identical, and mutant C appeared to have a fitness defect relative to the other mutants during mouse infection. The maximum frequency of mutant C in the mouse samples was 3.2%. The revelation of this fitness defect indicates that despite the narrow bottleneck at the site of infection, Tn-seq has the potential to identify B. burgdorferi factors involved in promoting bacterial fitness during mammalian infection. Larger competitive fitness experiments using transposon libraries can be performed using Tn-seq to answer an array of open questions in B. burgdorferi biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants F32 AI0983288 (E.B.T.), R01 AI071107 (L.T.H.), R56 AI80846 (L.T.H.), R21 AI097971 (L.T.H.), R01 AI055058 (A.C.), R01 AI59048 (S.J.N.), and R56 AI59048 (S.J.N.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Tanja Petnicki-Ocwieja for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Hodzic E, Feng S, Freet KJ, Borjesson DL, Barthold SW. 2002. Borrelia burgdorferi population kinetics and selected gene expression at the host-vector interface. Infect. Immun. 70:3382–3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pahl A, Kuhlbrandt U, Brune K, Rollinghoff M, Gessner A. 1999. Quantitative detection of Borrelia burgdorferi by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1958–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barthold SW, Persing DH, Armstrong AL, Peeples RA. 1991. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am. J. Pathol. 139:263–273 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moriarty TJ, Norman MU, Colarusso P, Bankhead T, Kubes P, Chaconas G. 2008. Real-time high resolution 3D imaging of the lyme disease spirochete adhering to and escaping from the vasculature of a living host. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000090. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Revel AT, Talaat AM, Norgard MV. 2002. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:1562–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks CS, Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Akins DR. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371–3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coutte L, Botkin DJ, Gao L, Norris SJ. 2009. Detailed analysis of sequence changes occurring during vlsE antigenic variation in the mouse model of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000293. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwartz DJ, Chen SL, Hultgren SJ, Seed PC. 2011. Population dynamics and niche distribution of uropathogenic Escherichia coli during acute and chronic urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 79:4250–4259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oberle M, Balmer O, Brun R, Roditi I. 2010. Bottlenecks and the maintenance of minor genotypes during the life cycle of Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001023. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfeiffer JK, Kirkegaard K. 2006. Bottleneck-mediated quasispecies restriction during spread of an RNA virus from inoculation site to brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5520–5525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barnes PD, Bergman MA, Mecsas J, Isberg RR. 2006. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis disseminates directly from a replicating bacterial pool in the intestine. J. Exp. Med. 203:1591–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuss SK, Etheredge CA, Pfeiffer JK. 2008. Multiple host barriers restrict poliovirus trafficking in mice. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000082. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ali A, Li H, Schneider WL, Sherman DJ, Gray S, Smith D, Roossinck MJ. 2006. Analysis of genetic bottlenecks during horizontal transmission of Cucumber mosaic virus. J. Virol. 80:8345–8350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ali A, Roossinck MJ. 2010. Genetic bottlenecks during systemic movement of Cucumber mosaic virus vary in different host plants. Virology 404:279–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergstrom CT, McElhany P, Real LA. 1999. Transmission bottlenecks as determinants of virulence in rapidly evolving pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:5095–5100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Handel A, Bennett MR. 2008. Surviving the bottleneck: transmission mutants and the evolution of microbial populations. Genetics. 180:2193–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mackinnon MJ, Bell A, Read AF. 2005. The effects of mosquito transmission and population bottlenecking on virulence, multiplication rate and rosetting in rodent malaria. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H, Roossinck MJ. 2004. Genetic bottlenecks reduce population variation in an experimental RNA virus population. J. Virol. 78:10582–10587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sacristan S, Malpica JM, Fraile A, Garcia-Arenal F. 2003. Estimation of population bottlenecks during systemic movement of tobacco mosaic virus in tobacco plants. J. Virol. 77:9906–9911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hodzic E, Feng S, Freet KJ, Barthold SW. 2003. Borrelia burgdorferi population dynamics and prototype gene expression during infection of immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. Infect. Immun. 71:5042–5055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gawronski JD, Wong SM, Giannoukos G, Ward DV, Akerley BJ. 2009. Tracking insertion mutants within libraries by deep sequencing and a genome-wide screen for Haemophilus genes required in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:16422–16427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodman AL, McNulty NP, Zhao Y, Leip D, Mitra RD, Lozupone CA, Knight R, Gordon JI. 2009. Identifying genetic determinants needed to establish a human gut symbiont in its habitat. Cell Host Microbe 6:279–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Opijnen T, Bodi KL, Camilli A. 2009. Tn-seq: high-throughput parallel sequencing for fitness and genetic interaction studies in microorganisms. Nat. Methods 6:767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gallagher LA, Shendure J, Manoil C. 2011. Genome-Scale Identification of Resistance Functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Using Tn-seq. mBio 2:e00315–10. 10.1128/mBio.00315-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klein BA, Tenorio EL, Lazinski DW, Camilli A, Duncan MJ, Hu LT. 2012. Identification of essential genes of the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. BMC Genomics 13:578. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kawabata H, Norris SJ, Watanabe H. 2004. BBE02 disruption mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 have a highly transformable, infectious phenotype. Infect. Immun. 72:7147–7154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin T, Gao L, Zhang C, Odeh E, Jacobs MB, Coutte L, Chaconas G, Philipp MT, Norris SJ. 2012. Analysis of an ordered, comprehensive STM mutant library in infectious Borrelia burgdorferi: insights into the genes required for mouse infectivity. PLoS One 7:e47532. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stewart PE, Rosa PA. 2008. Transposon mutagenesis of the lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi. Methods Mol. Biol. 431:85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin T, Gao L, Edmondson DG, Jacobs MB, Philipp MT, Norris SJ. 2009. Central role of the Holliday junction helicase RuvAB in vlsE recombination and infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000679. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart PE, Hoff J, Fischer E, Krum JG, Rosa PA. 2004. Genome-wide transposon mutagenesis of Borrelia burgdorferi for identification of phenotypic mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5973–5979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Norris SJ, Howell JK, Odeh EA, Lin T, Gao L, Edmondson DG. 2011. High-throughput plasmid content analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 by using Luminex multiplex technology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1483–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Purser JE, Norris SJ. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13865–13870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, Burhans R, Elnitski L, Shah P, Zhang Y, Blankenberg D, Albert I, Taylor J, Miller W, Kent WJ, Nekrutenko A. 2005. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 15:1451–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J, Galaxy Team 2010. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 11:R86–2010-11-8-r86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blankenberg D, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, Ananda G, Lazarus R, Mangan M, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. 2010. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 19:19.10.1–19.10.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang XG, Kidder JM, Scagliotti JP, Klempner MS, Noring R, Hu LT. 2004. Analysis of differences in the functional properties of the substrate binding proteins of the Borrelia burgdorferi oligopeptide permease (opp) operon. J. Bacteriol. 186:51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin B, Short SA, Eskildsen M, Klempner MS, Hu LT. 2001. Functional testing of putative oligopeptide permease (Opp) proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi: a complementation model in opp(−) Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1499:222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang XG, Lin B, Kidder JM, Telford S, Hu LT. 2002. Effects of environmental changes on expression of the oligopeptide permease (opp) genes of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 184:6198–6206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pitzer JE, Sultan SZ, Hayakawa Y, Hobbs G, Miller MR, Motaleb MA. 2011. Analysis of the Borrelia burgdorferi cyclic-di-GMP-binding protein PlzA reveals a role in motility and virulence. Infect. Immun. 79:1815–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sultan SZ, Pitzer JE, Boquoi T, Hobbs G, Miller MR, Motaleb MA. 2011. Analysis of the HD-GYP domain cyclic dimeric GMP phosphodiesterase reveals a role in motility and the enzootic life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 79:3273–3283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tilly K, Krum JG, Bestor A, Jewett MW, Grimm D, Bueschel D, Byram R, Dorward D, Vanraden MJ, Stewart P, Rosa P. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein required exclusively in a crucial early stage of mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 74:3554–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Steere AC. 2001. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grimm D, Elias AF, Tilly K, Rosa PA. 2003. Plasmid stability during in vitro propagation of Borrelia burgdorferi assessed at a clonal level. Infect. Immun. 71:3138–3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bolz DD, Sundsbak RS, Ma Y, Akira S, Kirschning CJ, Zachary JF, Weis JH, Weis JJ. 2004. MyD88 plays a unique role in host defense but not arthritis development in Lyme disease. J. Immunol. 173:2003–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Binder SC, Telschow A, Meyer-Hermann M. 2012. Population dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease. Front. Microbiol. 3:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Swanson KI, Norris DE. 2008. Presence of multiple variants of Borrelia burgdorferi in the natural reservoir Peromyscus leucopus throughout a transmission season. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 8:397–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guttman DS, Wang PW, Wang IN, Bosler EM, Luft BJ, Dykhuizen DE. 1996. Multiple infections of Ixodes scapularis ticks by Borrelia burgdorferi as revealed by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:652–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anderson JM, Norris DE. 2006. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in Peromyscus leucopus, the primary reservoir of Lyme disease in a region of endemicity in southern Maryland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5331–5341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kurtenbach K, De Michelis S, Sewell HS, Etti S, Schafer SM, Hails R, Collares-Pereira M, Santos-Reis M, Hanincova K, Labuda M, Bormane A, Donaghy M. 2001. Distinct combinations of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies found in individual questing ticks from Europe. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4926–4929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liveris D, Varde S, Iyer R, Koenig S, Bittker S, Cooper D, McKenna D, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. 1999. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease patients as determined by culture versus direct PCR with clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:565–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ruzic-Sabljic E, Arnez M, Logar M, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Cimperman J, Strle F. 2005. Comparison of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains isolated from specimens obtained simultaneously from two different sites of infection in individual patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2194–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liveris D, Gazumyan A, Schwartz I. 1995. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:589–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Seinost G, Dykhuizen DE, Dattwyler RJ, Golde WT, Dunn JJ, Wang IN, Wormser GP, Schriefer ME, Luft BJ. 1999. Four clones of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto cause invasive infection in humans. Infect. Immun. 67:3518–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang IN, Dykhuizen DE, Qiu W, Dunn JJ, Bosler EM, Luft BJ. 1999. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics 151:15–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilske B, Busch U, Fingerle V, Jauris-Heipke S, Preac Mursic V, Rossler D, Will G. 1996. Immunological and molecular variability of OspA and OspC. Implications for Borrelia vaccine development. Infection 24:208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brisson D, Baxamusa N, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. 2011. Biodiversity of Borrelia burgdorferi strains in tissues of Lyme disease patients. PLoS One 6:e22926. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wormser GP, Brisson D, Liveris D, Hanincova K, Sandigursky S, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Ludin S, Schwartz I. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi genotype predicts the capacity for hematogenous dissemination during early Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1358–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wormser GP, Liveris D, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Cavaliere LF, McKenna D, Holmgren D, Schwartz I. 1999. Association of specific subtypes of Borrelia burgdorferi with hematogenous dissemination in early Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 180:720–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu N, Montgomery RR, Barthold SW, Bockenstedt LK. 2004. Myeloid differentiation antigen 88 deficiency impairs pathogen clearance but does not alter inflammation in Borrelia burgdorferi-infected mice. Infect. Immun. 72:3195–3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cruz AR, Moore MW, La Vake CJ, Eggers CH, Salazar JC, Radolf JD. 2008. Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete, potentiates innate immune activation and induces apoptosis in human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 76:56–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shin OS, Isberg RR, Akira S, Uematsu S, Behera AK, Hu LT. 2008. Distinct roles for MyD88 and Toll-like receptors 2, 5, and 9 in phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi and cytokine induction. Infect. Immun. 76:2341–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Samuels DS. 2011. Gene regulation in Borrelia burgdorferi. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65:479–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dunham-Ems SM, Caimano MJ, Pal U, Wolgemuth CW, Eggers CH, Balic A, Radolf JD. 2009. Live imaging reveals a biphasic mode of dissemination of Borrelia burgdorferi within ticks. J. Clin. Invest. 119:3652–3665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ramamoorthi N, Narasimhan S, Pal U, Bao F, Yang XF, Fish D, Anguita J, Norgard MV, Kantor FS, Anderson JF, Koski RA, Fikrig E. 2005. The Lyme disease agent exploits a tick protein to infect the mammalian host. Nature 436:573–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hovius JW. 2009. Spitting image: tick saliva assists the causative agent of Lyme disease in evading host skin's innate immune response. J. Investig. Dermatol. 129:2337–2339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hovius JWR, de Jong MAWP, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, Fikrig E, van der Poll T, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TBH. 2008. Salp15 binding to DC-SIGN inhibits cytokine expression by impairing both nucleosome remodeling and mRNA stabilization. PLoS Pathog. 4:e31. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Montgomery RR, Lusitani D, De Boisfleury Chevance A, Malawista SE. 2004. Tick saliva reduces adherence and area of human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 72:2989–2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]