Abstract

Objectives. We tested 2 hypotheses found in studies of the relationship between suicide and unemployment: causal (stress and adversity) and selective interpretation (previous poor health).

Methods. We estimated Cox models for adults (n = 3 424 550) born between 1931 and 1965. We examined mortality during the recession (1993–1996), postrecession (1997–2002), and a combined follow-up. Models controlled for previous medical problems, and social, family, and employer characteristics.

Results. During the recession there was no excess hazard of mortality from suicide or events of undetermined intent. Postrecession, there was an excess hazard of suicide mortality for unemployed men but not unemployed women. However, for unemployed women with no health-problem history there was a modest hazard of suicide. Finally, there was elevated mortality from events of undetermined intent for unemployed men and women postrecession.

Conclusions. A small part of the relationship may be related to health selection, more so during the recession. However, postrecessionary period findings suggest that much of the association could be causal. A narrow focus on suicide mortality may understate the mortality effects of unemployment in Sweden.

Recent studies that have examined unemployment and suicide mortality have reported an elevated, unadjusted, or minimally adjusted odds ratio or risk ratio ranging from 1.9 to almost 6 times that of employed individuals.1–5 Debate about this association is, however, exemplified by contradictory interpretations of findings in individual-level studies. The 2 central arguments have posited that the relationship is either causal or spurious. But studies of suicide mortality and unemployment frequently find evidence to support both hypotheses.2,6–8

Those who have reported a predominantly causal relationship2,3 have often suggested a direct role of unemployment in which loss of control and resulting stress produce increased vulnerability to suicide9 especially with the accumulation of long-term unemployment.10,11 Job loss might also exacerbate preexisting social or mental health vulnerabilities.9 A variation on this view has suggested some heritable dispositions could even be activated by a stressor12 (e.g., unemployment). Ultimately, job loss and suicide are thought to be linked through an increase in mental distress and a decline in mental health or well-being.

There is considerable support for this view. Findings from a recent, comprehensive meta-analysis estimated that job loss reduced the mental health of the unemployed by a half standard deviation. Effect sizes were larger for the long-term unemployed, blue-collar workers, and men.13 Curvilinear effects were found that suggested distress increased significantly with shorter-term unemployment. It leveled off during the second year, and then increased sharply with longer-term unemployment accumulation (> 29 months). In addition, small but statistically significant effect sizes related to health selection were evident. Individuals who suffered with impaired mental health while enrolled in school experienced more job loss after graduating.

Other studies have suggested that job loss caused the development of mental health problems or reduced psychological well-being.9,13,14 A British longitudinal study that examined the effect of unemployment on the formation of depression and anxiety in young men has shown that both long-term unemployment exceeding 37 months and recent unemployment experience increased the risk of symptom reporting.9 These results are convincing because they were obtained after excluding men who had reported preexisting depression from the analysis.

A longitudinal study of Danish workers who were present at the time of a shipyard closure demonstrated that changes in employment status were followed by changes in psychological well-being among employed and unemployed individuals.14 Psychological well-being was poorest for those who became unemployed and remained jobless for the study’s duration. It was best for those who maintained jobs by switching employers. However, individuals who were unemployed and then became reemployed showed improvements in self-reported well-being. Those who were employed and then became unemployed in one of the study’s later time periods experienced a decrease. Changes in well-being that followed changes in employment status were taken as strong evidence for a causal effect of employment status on well-being.

By contrast, other studies have suggested that suicide and unemployment are unrelated and are predominantly attributable to preexisting, individual-level mental health, or psychiatric problems,1,6 which may have heritable links.15 The conclusions of such studies are undergirded by the idea that the majority of individuals who have died of suicide suffered from a preexisting mental illness.1 A meta-analysis of studies that utilized the psychological autopsy method for ascertaining the specific psychiatric disorders suffered by suicide completers found that 87% of the decedents had a preexisting mental disorder.16 The relative proportions of male and female completers who were diagnosed over a range of mental health conditions (substance-related, personality disorders, affective disorders, childhood disorders, and depressive disorders) were different.

Studies that have examined parasuicide have also reported that the strongest associated risk factors were having either a psychiatric disorder or a history of hospitalization for psychiatric disorder.1,15,17 Beautrais et al. further suggested that the relationship between unemployment and parasuicide risk was completely explained by a combination of social risk factors and psychiatric disorder.17 However, those who died of suicide are likely to have been different from attempters,18 so a direct comparison with studies of suicide may not be warranted.

It is also possible that other preexisting physical health problems confound the relationship between job loss and suicide such that poor health alone may lead to unemployment. Studies have shown a relationship between previous poor health, longer unemployment duration, and reduced exit rates from unemployment.19 Those that have examined unemployment and mortality have found only small confounding effects of previous poor health.11,20

On the basis of these findings, a disjunctive interpretation of the association as either selective or causal is simplistic. We tested the validity of both hypotheses and assumed that the relative explanatory power of each depends on several factors including prevailing macroeconomic conditions, preexisting vulnerability (based on social risk factors, mental health, or both) to a stressor such as job loss, and individual-level unemployment duration.

When unemployment is framed as a crisis event, selective confounders could play a greater role in more immediate suicides. As a long-term, chronic experience, causal factors may factor more prominently. For example, there may be less ambiguity when one is suggesting a causal relationship in a case where substantial unemployment experience has accumulated before a suicide because health status and factors related to social vulnerability are more likely to function as mediators in the causal chain rather than as determinants of the job loss.

METHODS

All Swedish men and women (n = 4 224 210) who were born between 1931 and 1965, and who were still alive on January 1, 1993, were eligible for the study. The Swedish work and mortality database holds information on this population from several national registries including the in-patient registry (1982–1991), the cause-of-death registry (1992–2002), the 1990 Census, and the Longitudinell Integrationsdatabas för Sjukförsäkrings och Arbetsmarknadsstudier (Longitudinal Integrated Database for Sickness Insurance and Labor Market Studies; LISA) registry (1992–1996). The latter includes information about employment. To limit the inclusion of individuals who had retired and those with a previous history of unemployment, we only selected individuals who were gainfully employed at the time of the 1990 Census (n = 3 424 550).

The data set contained annual information on the unemployment status of individuals in each year of the recession. Employment information was unavailable in the year an individual died. Therefore, those who died in 1992 could not be included. We did not know if unemployment experience was continuous within a particular year unless an individual spent the entire year unemployed. We used a binary measure of unemployment status where individuals were classified as unemployed if they were out of work for more than 30 days during the recession.

Social Risk Factors

We used baseline social, family, and employer characteristic data from 1991. We had information on the birth month and year, gender, education level, total household income (both earned and work-related benefits, e.g., sick pay, worker’s compensation, parental benefit), marital status, immigrant status, number of children, and the employer’s county location for each person. We utilized employer county location as a proxy for the concentration of industries in different parts of the country. We grouped individuals into seven 5-year birth-cohort intervals (1931–1965), 8 education-level categories, 4 marital-status categories, and 9 employer county location indicators (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Baseline Characteristics in 1991 for Swedish Men and Women Born Between 1931 to 1965 Who Were Gainfully Employed in 1990 and Alive in 1992

| Variable | Men (n = 1 767 953), No. (%) | Women (n = 1 656 597), No. (%) |

| Age cohorts, year born | ||

| 1931–1935 | 169 786 (9.60) | 159 675 (9.64) |

| 1936–1940 | 208 886 (11.82) | 196 789 (11.88) |

| 1941–1945 | 285 210 (16.13) | 266 710 (16.10) |

| 1946–1950 | 302 825 (17.13) | 288 023 (17.39) |

| 1951–1955 | 267 866 (15.15) | 252 305 (15.23) |

| 1956–1960 | 261 460 (14.79) | 241 964 (14.61) |

| 1961–1965 | 271 920 (15.38) | 251 131 (15.16) |

| Marital status, 1991 | ||

| Married | 1 025 466 (58.00) | 1 027 683 (62.04) |

| Unmarried | 576 895 (32.63) | 398 805 (24.07) |

| Divorced | 155 750 (8.81) | 195 972 (11.83) |

| Widowed | 9842 (0.56) | 34 137 (2.06) |

| Education level, 1991 | ||

| Education level missing | 11 849 (0.67) | 5218 (0.32) |

| Presecondary upper school, < 9 y | 311 047 (17.59) | 228 403 (13.79) |

| 9–10 y presecondary upper school | 224 265 (12.69) | 200 626 (12.11) |

| ≤ 2 y secondary upper school | 542 273 (30.67) | 625 552 (37.76) |

| > 2 to max. 3 y, secondary upper school | 255 543 (14.45) | 147 758 (8.92) |

| Postsecondary upper school, < 3 y | 189 786 (10.73) | 241 725 (14.59) |

| Postsecondary upper school, ≥ 3 y | 215 065 (12.16) | 202 797 (12.24) |

| Researcher education | 18 125 (1.03) | 4518 (0.27) |

| Immigrant status, 1991 | 210 741 (11.92) | 201 130 (12.14) |

| Medical history, 1982–1991 | ||

| Any previous alcohol disease–related diagnosisa | 73 056 (4.13) | 33 023 (1.99) |

| Any previous mental health diagnosisb | 32 747 (1.85) | 38 490 (2.32) |

| Any previous suicide or self-injury attempt | 7775 (0.44) | 11 421 (0.69) |

Note. Mean number of children, 1991: 1.06 (men), 1.15 (women). Mean number of hospitalizations, 1982–1991: 0.72 (men), 1.46 (women). Total household income in Swedish Crowns, 1991: 190 170 (men), 131 548 (women).

Includes those with an alcohol-related mental health diagnosis.

Excludes those with an alcohol-related mental health diagnosis.

About 0.49% had missing information on attained education level or employer county location (2.29%). We included dummy variables representing a missing status in the analysis so that estimates of the effects of baseline characteristics of individuals would not be biased.

Medical History and Mortality Outcomes

The analyses included a summary measure of the total number of hospitalizations an individual experienced at the start of 1982 until the end of 1991. We also included a binary measure indicating whether a person had been hospitalized for the following primary, or nonprimary diagnoses (up to 9): any previous alcohol-related disease diagnosis including an alcohol-related mental health diagnosis, any previous self-injury or suicide attempt, and any previous mental health diagnosis excluding an alcohol-related mental health diagnosis (for a list of codes, see the Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Diagnoses were given in International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8) or Ninth Revision (ICD-9)21,22 codes from the beginning of 1982 until the end of 1991 and included those received upon admission and throughout the course of a hospital stay until discharge.

We examined suicide mortality (ICD-9: E950–E959; ICD-10: X60–X84, Y870) and events of undetermined intent (ICD-9: E980–E988; ICD-10: Y10–Y34).22,23 We studied both because it has been suggested that the majority of studies of suicide mortality suffer from a problem of validity24 because most events of undetermined intent in Western Europe are likely suicides.25 Hence, the sole examination of suicide mortality is unlikely to provide the true estimate of the mortality effects of unemployment. We observed a total of 5717 suicide deaths and 1546 deaths from events of undetermined intent (Table 2). For deaths that occurred from 1993 to 1996, codes are given in ICD-9. For those that occurred from 1997 to 2002, codes are given in ICD-10. We collected individual death month and year of death.

TABLE 2—

Number of Deaths and Selected Characteristics of Unemployed Men and Women in Sweden, by Period and Cause of Death, Who Were Gainfully Employed in 1990 and Alive in 1992

| Period and Cause of Death | No. of Deaths, Employed | No. of Deaths, Unemployed | Total No. of Deaths | Average No. of Days Unemployed, 1992–1996 | % Died 1–2 y After Becoming Unemployed | % Died 3–4 y After Becoming Unemployed |

| Men | ||||||

| Died 1993–1996 | ||||||

| Suicide | 1234 | 498 | 1732 | 92 | 93.6 | 6.4 |

| EUI | 333 | 209 | 542 | 128 | 93.8 | 6.2 |

| Died 1997–2002 | ||||||

| Suicide | 1561 | 858 | 2419 | 188 | 25.2 | 25.5 |

| EUI | 255 | 274 | 529 | 256 | 25.5 | 25.9 |

| Women | ||||||

| Died 1993–1996 | ||||||

| Suicide | 497 | 155 | 652 | 71 | 90.3 | 9.7 |

| EUI | 151 | 64 | 215 | 73 | 85.9 | 14.1 |

| Died 1997–2002 | ||||||

| Suicide | 675 | 239 | 914 | 114 | 21.4 | 34.1 |

| EUI | 166 | 94 | 260 | 148 | 25.5 | 39.4 |

Note. EUI = event of undetermined intent.

Study Design

We utilized 3 strategies to assess the relative contribution of causation and selection. We limited the study to a time period during which there was very high, widespread unemployment (nearly 23% of the cohort experienced a job loss) and average unemployment spell duration was longer (average duration during 1992–1996 for those aged 16–64 years was 40.2 weeks; average duration for those aged 16–64 years in 1990 was 14.2 weeks). Job loss experienced at such a time of mass unemployment may not initially be problematic.20,26 But it could become increasingly so as spell duration increases and shame or social stigma intensify as others who have also been jobless return to work.11 In addition, savings and state transfer benefits are exhausted with longer-term unemployment. It is also likely that job loss because of health selection occurs less frequently in the context of mass layoffs and establishment closures.13,20

We assessed the excess mortality effects of unemployment in 3 different mortality follow-ups: during the recession (January 1, 1993–December 31, 1996), postrecession (January 1, 1997–December 31, 2002), and a combined period (January 1, 1993–December 31, 2002). We found that those who died during the recession had less average elapsed time between job loss and death, and less cumulative unemployment experience than those who died postrecession (Table 2). In each period we assessed and compared the contribution of baseline social, family, and employer characteristics, and those related to previous health status.

Finally, we conducted separate analyses where we excluded individuals who had a previous mental health diagnosis, a previous self-injury or suicide attempt, or a preexisting alcohol-related disease diagnosis. This approach produced an estimate of the direct effect of unemployment in relation to self-inflicted mortality that was unbiased by potential statistical interactions between unemployment status and previous health status.

Statistical Analysis

We used Cox regression for the statistical analysis. Our time scale was the age at the time of censoring or death. Models accounted for the entry of participants in our observation periods at different ages. We stratified analyses by gender and birth cohort. We do not present the age cohort–stratified analyses because residual effects of unemployment were not evident for men in the oldest cohorts (born 1931–1935, 1936–1940, or 1941–1945) or for women in any birth cohort.

We estimated 5 sets of models for each of the mortality follow-ups. We adjusted the baseline model by birth cohort. The second model controlled for birth cohort and an individual’s previous health status. A third model adjusted for birth cohort, and social, family, and employer characteristics without any control for previous health status. The fourth, fully adjusted model included the indicators for previous health status and social, family, and employer characteristics. Finally, we estimated a fifth, fully adjusted model that excluded individuals who had a previous mental health diagnosis, a previous self-injury or suicide attempt, or a previous alcohol disease diagnosis.

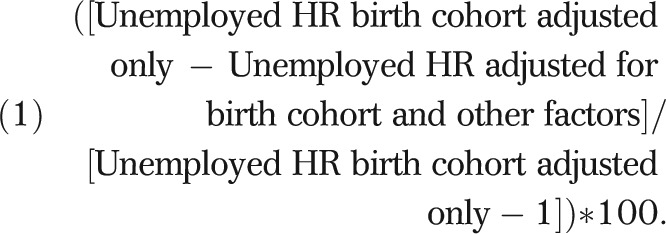

This approach allowed us to estimate the degree to which previous health status and social, family, and employer characteristics confounded or explained the effect of unemployment on suicide or events of undetermined intent mortality. For this comparison we calculated the percentage reduction to the age-adjusted, baseline hazard as:

|

RESULTS

Tables 3 and 4 show suicide and events of undetermined intent in the 3 time periods by unemployment experience in men (Table 3) and women (Table 4).

TABLE 3—

Suicide and Events of Undetermined Intent in 1993–1996, 1997–2002, and 1993–2002, by Unemployment Experience in 1992–1996, Among Men in Sweden, Born Between 1931–1965 Who Were Gainfully Employed in 1990 and Alive in 1992

| Mortality Follow-Up, 1993–1996 |

Mortality Follow-Up, 1997–2002 |

Mortality Follow-Up, 1993–2002 |

|||||||

| Variable | Unemployeda Male HR (95% CI) | % Reduction in the HR | Total No. of Deaths | Unemployeda Male HR (95% CI) | % Reduction in the HR | Total No. of Deaths | Unemployeda Male HR (95% CI) | % Reduction in the HR | Total No. of Deaths |

| Suicide | |||||||||

| Employed (Ref) | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.29 (1.16, 1.44) | … | 1.75 (1.61, 1.91) | … | 1.55 (1.45, 1.66) | … | |||

| Age- and previous health–adjustedb | 1.10 (0.98, 1.22) | 66 | 1.55 (1.42, 1.69) | 27 | 1.35 (1.26, 1.44) | 36 | |||

| Age- and SFE–adjustedc | 1.07 (0.96, 1.20) | 76 | 1.51 (1.38, 1.65) | 32 | 1.31 (1.23, 1.41) | 44 | |||

| Fully adjusted | 1.00 (0.90, 1.12) | 100 | 1732 | 1.43 (1.31, 1.56) | 43 | 2419 | 1.24 (1.16, 1.33) | 56 | 4151 |

| Fully adjustedd | 1.05 (0.92, 1.20) | … | 1274 | 1.48 (1.33, 1.63) | … | 1912 | 1.30 (1.20, 1.40) | … | 3186 |

| Events of undetermined intent | |||||||||

| Employed (Ref) | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.98 (1.66, 2.37) | … | 3.29 (2.77, 3.91) | … | 2.55 (2.35, 2.88) | … | |||

| Age- and previous health–adjustedb | 1.41 (1.17, 1.69) | 58 | 2.45 (2.05, 2.93) | 37 | 1.85 (1.63, 2.11) | 45 | |||

| Age- and SFE–adjustedc | 1.29 (1.07, 1.55) | 70 | 2.41 (2.01, 2.89) | 38 | 1.78 (1.54, 2.00) | 50 | |||

| Fully adjusted | 1.13 (0.94, 1.37) | 87 | 542 | 2.09 (1.75, 2.52) | 52 | 529 | 1.54 (1.35, 1.75) | 65 | 1071 |

| Fully adjustedd | 1.08 (0.82, 1.42) | … | 275 | 2.31 (1.82, 2.93) | … | 310 | 1.63 (1.37, 1.95) | … | 585 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; SFE = social, family, and employer characteristics.

Unemployed = at least 30 d of unemployment in any 1 year, 1992–1996.

Adjusted for the natural logarithm (no. of total hospitalizations), any previous suicide or self-injury attempt, any previous mental health diagnosis excluding an alcohol-related diagnosis, and any previous alcohol-related diagnosis, 1982–1991.

Social, family, and employer characteristics = natural logarithm (no. of children), marital status, natural logarithm (yearly household income), education level, employer county location, and immigrant status.

Excludes those with a previous history of self-injury or a suicide attempt, any previous mental health diagnosis excluding an alcohol-related diagnosis, and any previous alcohol-related diagnosis, 1982–1991.

TABLE 4—

Suicide and Events of Undetermined Intent in 1993–1996, 1997–2002, and 1993–2002, by Unemployment Experience in 1992–1996, Among Women in Sweden, Born Between 1931–1965 Who Were Gainfully Employed in 1990 and Alive in 1992

| Mortality Follow-Up, 1993–1996 |

Mortality Follow-Up, 1997–2002 |

Mortality Follow-Up, 1993–2002 |

|||||||

| Variable | Unemployeda Female HR (95% CI) | % Reduction in the HR | Total No. of Deaths | Unemployeda Female HR (95% CI) | % Reduction in the HR | Total No. of Deaths | Unemployeda Female HR (95% CI) | % Reduction in the HR | Total No. of Deaths |

| Suicide | |||||||||

| Employed (Ref) | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.26 (1.05, 1.52) | … | 1.39 (1.20, 1.62) | … | 1.34 (1.19, 1.50) | … | |||

| Age- and previous health–adjustedb | 0.98 (0.81, 1.18) | 100 | 1.14 (0.97, 1.33) | 64 | 1.07 (0.94, 1.20) | 79 | |||

| Age- and SFE–adjustedc | 1.07 (0.88, 1.30) | 73 | 1.16 (0.99, 1.36) | 59 | 1.12 (0.99, 1.26) | 65 | |||

| Fully adjusted | 0.96 (0.79, 1.17) | 100 | 652 | 1.07 (0.91, 1.25) | 82 | 914 | 1.02 (0.90, 1.15) | 94 | 1566 |

| Fully adjustedd | 1.14 (0.87, 1.48) | … | 357 | 1.26 (1.04, 1.54) | … | 599 | 1.22 (1.04, 1.42) | … | 956 |

| Events of undetermined intent | |||||||||

| Employed (Ref) | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | 1.00 | … | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.71 (1.26, 2.33) | … | 2.31 (1.77, 3.00) | … | 2.02 (1.66, 2.47) | … | |||

| Age- and previous health–adjustedb | 1.34 (0.98, 1.84) | 52 | 1.85 (1.42, 2.42) | 35 | 1.60 (1.31, 2.96) | 41 | |||

| Age- and SFE–adjustedc | 1.26 (0.92, 1.74) | 63 | 1.77 (1.34, 2.32) | 41 | 1.52 (1.23, 1.87) | 49 | |||

| Fully adjusted | 1.19 (0.87, 1.64) | 73 | 215 | 1.63 (1.24, 2.15) | 52 | 260 | 1.42 (1.15, 1.74) | 59 | 475 |

| Fully adjustedd | 1.32 (0.85, 2.07) | … | 114 | 1.69 (1.19, 2.40) | … | 161 | 1.53 (1.16, 2.02) | … | 275 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; SFE = social, family, and employer characteristics.

Unemployed = at least 30 days of unemployment in any 1 year, 1992–1996.

Adjusted for the natural logarithm (no. of total hospitalizations), any previous suicide or self-injury attempt, any previous mental health diagnosis excluding an alcohol-related diagnosis, and any previous alcohol-related diagnosis, 1982–1991.

Social, family, and employer characteristics = natural logarithm (no. of children), marital status, natural logarithm (yearly household income), education level, employer county location, and immigrant status.

Excludes those with a previous history of self-injury or a suicide attempt, any previous mental health diagnosis excluding an alcohol-related diagnosis, and any previous alcohol-related diagnosis, 1982–1991.

Suicide, Men

Table 3 shows a modest hazard of suicide for men during the recession after adjustment for birth cohort (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.16, 1.44). Further adjustment for previous health status and factors related to social, family, and employer characteristics shows that there was no excess hazard of suicide mortality attributable to unemployment. The reduction in the unemployed hazard ratio suggests that social, family, and employer characteristics explain a larger part of the association (76% reduction) than confounders related to previous health status (66% reduction). The fifth, fully adjusted model, which excludes individuals who had a previous mental health diagnosis, a previous self-injury or suicide attempt, or a previous alcohol disease–related diagnosis provides additional evidence demonstrating that the hazard of suicide mortality was not elevated once factors related to social, family, and employer characteristics were included (HR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.92, 1.20).

By contrast, for men who died of suicide after the end of the recession, there was a moderate excess effect of unemployment (HR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.31, 1.56) net of previous health status and social, family, and employer characteristics. The reduction in the hazard ratio after adjustment again suggests social, family, and employer characteristics may explain a somewhat greater part of the association (32% reduction) than previous health status (27% reduction). The fully adjusted model results also suggest that less than half of the excess effect is explained by previous health status and social, family, and employer characteristics (combined reduction 43%). Most of the effect of unemployment on suicide mortality remains. In addition, the fifth, fully adjusted model suggests that the hazard of suicide mortality attributable to unemployment was about the same or even larger once we excluded individuals who had a previous mental health or alcohol-related disease diagnosis, or a previous self-injury or suicide attempt (HR = 1.48; 95% CI = 1.33, 1.63).

The combined follow-up suggests that social, family, and employer characteristics alone may explain a larger part of the association than previous health status as the effect of unemployment was reduced by 44%. We also noted a slight increase in the magnitude of the excess effect (HR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.20, 1.40) when we omitted those individuals who had indicators associated with previous mental health and alcohol-related disease problems from the analysis. Finally, we found that unemployed men in the youngest cohort (born 1961–1965) and the prime working age cohorts (born 1946–1950, 1951–1955, 1956–1960) had an elevated hazard of suicide after full adjustment.

Events of Undetermined Intent, Men

The recessionary mortality follow-up suggests that unemployment was not related to excess mortality because of events of undetermined intent once we included social, family, and employer characteristics and previous health status in the models (Table 3). The combination of controls explains 87% of the hazard rendering the remaining excess effect statistically nonsignificant (HR = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.94, 1.37). However, in combination, social, family, and employer characteristics alone explained a greater part of the observed association. This was also the case in the model that excluded individuals with a previous medical history of mental health and alcohol-related disease problems. Nearly the entire excess effect was attributable to social, family, and employer characteristics.

By contrast, the fully adjusted models from the postrecessionary mortality follow-up suggested a strong effect of unemployment (HR = 2.09; 95% CI = 1.75, 2.52). A substantial portion of the excess effect remains (48%). The magnitude of the hazard for events of undetermined intent was also larger in comparison with the suicide results. It is notable that the relationship between unemployment and mortality from events of undetermined intent strengthened in both the later (HR = 2.31; 95% CI = 1.82, 2.93) and combined (HR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.37, 1.95) follow-ups after we excluded individuals who had previous mental health or alcohol-related disease diagnoses.

Suicide, Women

Compared with men, results were starkly different for women as excess suicide mortality was lower (Table 4). In both follow-up periods, previous health status explained a larger share of the effect of unemployment than social, family, and employer characteristics. In the recessionary follow-up, the entire excess effect was explained. The postrecessionary follow-up showed a 64% reduction and a nonsignificant, minimally elevated hazard (HR = 1.14; 95% CI = 0.97, 1.33). As a result, the excess effect in the combined follow-up was reduced by 79% when indicators of previous health status were the only included covariates (HR = 1.07; 95% CI = 0.94, 1.20).

We also noted a full to nearly complete reduction in the observed association when we jointly included factors related to social, family, and employer characteristics and previous health status in the models. In the postrecessionary and the combined follow-up it is notable that there was modestly elevated suicide mortality among unemployed women who had no history of a previous hospitalization for a mental health condition or alcohol disease–related illness (HR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.04, 1.54; HR = 1.22; 95% CI = 1.04, 1.42).

Events of Undetermined Intent, Women

The hazard of death associated with an event of undetermined intent was moderately higher for unemployed women. In the later and the combined follow-up, previous health status alone appeared to reduce the association less than those factors related to social, family, and employer characteristics. Together, more than half of the association was explained by both, leaving a fully adjusted hazard of 1.63 (95% CI = 1.24, 2.15) in the postrecessionary follow-up and 1.42 (95% CI = 1.15, 1.74) in the combined analysis.

The modest excess effect in the first follow-up became statistically insignificant once we included social, family, and employer characteristics or factors related to selection in each of the individual models. In both the later and combined follow-up we also noted a similar strengthening of the association between unemployment and events of undetermined intent mortality after we excluded women who had a history of medical problems.

DISCUSSION

The evidence we present supports the hypothesis that factors related to social, family, and employer characteristics and previous health status confound the relationship between unemployment, suicide, and likely suicides during a period of mass unemployment in Sweden. At the same time, we found an effect of unemployment on postrecession suicide and events of undetermined intent mortality among men and women after we considered differences in health and social, family, and employer characteristics. We also found that the magnitude of the hazard estimates of suicide and probable suicide mortality associated with unemployment differ. This provides support for the idea that a narrow focus on legally classified suicides is likely to understate the mortality effects of employment loss.

During the recession, social, family, and employer characteristics (especially those indicative of preexisting social disadvantage—e.g., single or divorced marital status) and previous health status combined, explain all of the excess effect of unemployment in the suicide analyses and the events of undetermined intent analyses. However, factors associated with the social, family, and employer characteristics of individuals appear to explain more of the hazard of unemployment. The female suicide analysis was the only exception where previous health status explained the entire residual effect. A direct effect of unemployment does not appear to exist during the recession.

In contrast to the recessionary period, we saw a possible causal effect of unemployment on mortality postrecession. Almost half of the association was left unexplained by our social, family, and employer characteristic predictors and previous health status. A substantial part of later suicide (men) and events of undetermined intent (men and women) mortality remained associated with earlier unemployment experience.

The interpretation of the effect as direct in the postrecessionary period was further supported by an increase in the residual estimate for men and women after we excluded those who had a previous mental health or alcohol disease–related diagnosis from the fully adjusted models. The time between unemployment and death was longer and the accumulation of unemployment experience was, on average, greater for individuals who died postrecession. It seems more likely that the relationship between long-term unemployment and suicide can be interpreted as causal. Longer-duration unemployment has been linked to an increase in material hardship,27 an increase in shame, a loss of social status,20 increased heavy drinking,28 deterioration in mental health and well-being, and the development of mental health problems.9,13,14

The results from the female suicide analysis were less clear. The contribution of confounders of health selection to the reduction in the hazard of suicide was slightly greater than the reduction attributable to social, family, and employer characteristics. A substantial part of the relationship during the recession was spurious whereas a probable causal effect remained postrecession. Postrecession models that excluded women who had a previous mental health or alcohol-related disease diagnosis showed a modest excess hazard of suicide and a somewhat larger hazard of mortality from events of undetermined intent after we controlled for social, family, and employer characteristics. Taken together, the evidence suggests that a part of the relationship for women is likely to have been causal during the latter period.

Given previous findings2,29 that have shown that job loss is associated with suicide in men and women, the mixed findings for women could be interpreted in several ways. Because the residual effect for women was modest, job loss may not have had the same material and psychosocial effects as it did for men. Women are still responsible for a larger share of the second shift in Swedish households. Unemployment duration was also shorter for women. Sectors of the economy that had a larger share of female workers (service and government) were affected toward the end of the recession and closer to the beginning of the recovery. Coupled with lower relative earnings, the loss of paid employment appears to have had less leverage in female suicide mortality.

Women in Western countries are also more likely to seek treatment for mental health problems.30 It is possible that the Swedish women who died of suicide could have been more selected while at the same time many potential suicide attempters might have sought help. Misclassification bias of probable suicide deaths is also a possibility. Because of the difference concerning the means used to cause death, probable suicides among women may have been somewhat more likely to receive an accidental or an event of undetermined intent classification (i.e., a higher percentage of unemployed women than unemployed men died from events of undetermined intent classified as poisonings).

Limitations

Some limitations should be noted. Although the study included previous physical and mental health information from a 10-year follow-up period, these measures of health status may be somewhat crude and identify only those with serious health problems. It is possible that selection effects were better diagnosed among women because of their greater propensity to seek help for mental or physical health problems. However, it should be reiterated that these health-related measures used in combination with social, family, and employer characteristics explained most or all of the excess effect of unemployment on suicide or events of undetermined intent for those who died during the recession.

In addition, we could not determine if mental health declined as a result of unemployment in either period and could not test to see if the loss of unemployment benefits or income over time was directly related to an increase in the hazard of mortality from suicide or an event of undetermined intent. Although beyond the scope of this study, time varying covariates such as income and marital status could mediate or modify the relationship. Future studies could address these topics.

Conclusions

We conclude that the Swedish recession in 1992 through 1996 had no, or marginal, immediate impact on suicide mortality. The elevated mortality among those unemployed at this time is mostly but not entirely because of their recruitment among individuals with a different personal, social, and family background. By contrast, there is clearly elevated mortality that is likely to be directly related to unemployment experience during the recession from both suicide and events of undetermined intent postrecession. Our interpretation, based on findings from a earlier but related study, is that this is because of accumulated, long-term unemployment (especially among men).11 Our findings are consistent with the idea that mental health problems are likely to have developed as a result of unemployment, particularly as unemployment experience accumulated over time. This interpretation is supported by the direct effect of unemployment in the later mortality follow-up and the absence of such in the early period.

The presented evidence is also consistent with the hypothesis that causal factors and confounders of selection contribute to the observed relationship between unemployment, suicide, and events of undetermined intent mortality. We recognize that it is unlikely that becoming unemployed causes most people to self-destruct immediately unless significant, existing vulnerabilities (e.g., previous mental or physical health problems, or other social vulnerabilities) preexist, although this possibility cannot be completely discounted in this study. Platt18 has argued that those who are socially disadvantaged, i.e., those individuals with poor coping skills and low resources (e.g., material, human capital, social support) are perhaps more inclined to feel a loss of control, anxiety, depressed, or hopeless as job loss experience accumulates.

Preventing suicide is an extremely desirable public health goal as suicide levies a tragic toll not only on the decedent but also upon those individuals to whom they were connected. Findings from this study suggest that suicide interventions should be extended to those who have experienced long-term unemployment during a deep economic crisis especially in the period when economic conditions begin to improve. As we have shown, even in a context such as Sweden where health care is universally available, providers should be more attuned to changes in the mental well-being of those who have experienced long-term joblessness. Although we did not test the hypothesis that the loss of or change in unemployment benefits was related to an increased hazard of mortality from suicide or an event of undetermined intent mortality in either period, it is possible that austerity measures introduced at the time of this recession (including changed minimum or maximum benefit levels) as well as age-related length of compensation limits could have compounded difficulties faced by those who died of suicide or events of undetermined intent after experiencing long-term unemployment. State-supported income replacement programs are often directly amendable by policymakers.

Acknowledgments

The study received support from a grant by The Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS), project 1017720.

We wish to acknowledge the anonymous referees for the useful suggestions that they gave.

Note. The sponsor had no role in the collection of the data, the study design, the analysis of the data, the interpretation of the results, or the formulation of this article.

Human Participant Protection

Ethical permission for this research was obtained from the Stockholm Regional Board of Ethics.

References

- 1.Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Erikson T, Qin P, Westergaard-Nielsen P. Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Lancet. 2000;355(9197):9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakely TA, Collings SC, Atkinson J. Unemployment and suicide. Evidence for a causal association? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(8):594–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis G, Sloggett A. Suicide, deprivation, and unemployment: record linkage study. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1283–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kposowa AJ. Unemployment and suicide: a cohort analysis of social factors predicting suicide in the US national longitudinal mortality study. Psychol Med. 2001;31(1):127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corcoran P, Arensman E. Suicide and employment status during Ireland’s Celtic Tiger economy. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(2):209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundin A, Lundberg I, Hallsten L, Ottosson J, Hemmingsson T. Unemployment and mortality: a longitudinal prospective study on selection and causation in 49321 Swedish middle-aged men. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(1):22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voss M, Nylen L, Floderus B, Diderichsen F, Terry P. Unemployment and early cause-specific mortality: a study based on the Swedish twin registry. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2155–2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platt S, Micciolo R, Tansella M. Suicide and unemployment in Italy: description, analysis and interpretation of recent trends. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(11):1191–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montgomery SM, Cook DG, Bartley MJ, Wadsworth ME. Unemployment pre-dates symptoms of depression and anxiety resulting in medical consultation in young men. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(1):95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mäki N, Martikainen P. The role of socioeconomic indicators on non-alcohol and alcohol-associated suicide mortality among women in Finland. A register-based follow-up study of 12 million person-years. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2161–2169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcy A, Vågerö D. The length of unemployment predicts mortality, differently in men and women, and by cause of death: a six year mortality follow-up of the Swedish 1992–1996 recession. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):1911–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freese J. Genetics and the social science explanation of individual outcomes. Am J Sociol. 2008;114(suppl):S1–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul K, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74:264–282 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iversen L, Sabroe S. Psychological well-being among unemployed and employed people after a company closedown—a longitudinal-study. J Soc Issues. 1988;44:141–152 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen P. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:37–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Unemployment and serious suicide attempts. Psychol Med. 1998;28(1):209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Platt S. Unemployment and suicidal-behavior: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(2):93–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart JM. The impact of health status on the duration of unemployment spells and the implications for studies of the impact of unemployment on health status. J Health Econ. 2001;20(5):781–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martikainen PT, Valkonen T. Excess mortality of unemployed men and women during a period of rapidly increasing unemployment. Lancet. 1996;348(9032):909–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ICD-9 to ICD-8 conversion table. Available at: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/laddaner/Documents/9to8.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2013.

- 22. Translator ICD-10 to ICD-9. Available at: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/laddaner/Documents/10TO9.PDF. Accessed January 29, 2013.

- 23.World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision Version for 2003. Available at: http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online2003/fr-icd.htm. Accessed January 29, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mäkinen IH. Eastern European transition and suicide mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(9):1405–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barraclough B, Hughes J. Suicide. Clinical and Epidemiological Studies. London, England: Croom Helm; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Platt S, Kreitman N. Long-term trends in parasuicide in Edinburgh, 1968–87. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990;25(1):56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinicki A, Prussia E, McKee-Ryan F. A panel study of coping with involuntary job loss. Acad Manage J. 2000;43:90–100 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mossakowski KN. Is the duration of poverty and unemployment a risk factor for heavy drinking? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(6):947–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eliason M, Storrie D. Does job loss shorten life? J Hum Resour. 2009;44:277–302 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy GE. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(4):165–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]