Abstract

The cyclocystine ring structure (CRS, 3), which results from a disulfide-bond between adjacent cysteine residues, is a rare motif in protein structures and is functionally important to those few proteins that posses it. This communication will focus on the construction of CRS mimics and the determination of their respective redox potentials.

Keywords: cyclocystine, dithiocine, vicinal disulfide-bond, thiol-disulfide redox

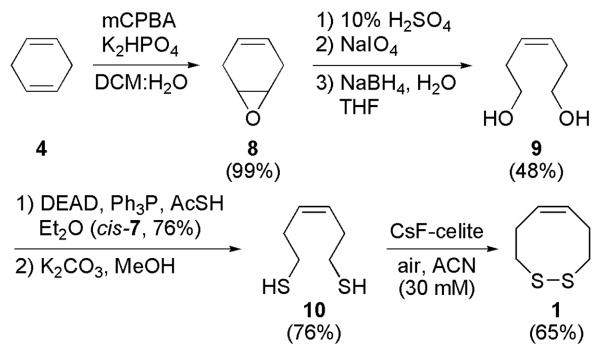

A disulfide-bond between adjacent cysteine residues (3, Figure 1) is a very rare occurrence in protein structures. Currently 32 out of ca. ~28,000 proteins structurally identified in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (PDB) carry this unique motif.1 In every case the amide bond of the CRS is reported to be in a strained trans geometry with an average ω value of 171°.1 Peptide bonds prefer a trans conformation with a torsion angle of 180° so that the nitrogen lone-pair can have maximal delocalization into the π-system, while minimizing steric repulsions from peptidyl side-chains. However, the small ring nature of the eight-membered CRS allows for multiple amide conformations to be energetically feasible. The amide bond could adopt a cis conformation, which still allows for delocalization of the nitrogen lone-pair, but would cause the main peptidyl-chain to have a kink in it. A “strained” trans conformation allows the main chain to remain relatively unaltered, but still allows for partial delocalization of the nitrogen lone-pair into the π-system. Our model studies show that a torsion angle of 180° is not allowed for a CRS due to it’s inability to form the disulfide-bond. Hence, the nitrogen lone-pair must come slightly out of phase with the π-system to allow disulfide-bond formation.

Figure 1.

Small Molecule Mimics of CRS

A reasonable model for a CRS is cyclooctene. Energetically, the cis isomer is more stable than the trans as a result of the ring strain required to incorporate a trans double bond. This ring strain is demonstrated by the higher ΔHHydrogenation of trans-cyclooctene (34.4 kcal/mol) compared to the cis isomer (23.0 kcal/mol).2 If the cyclooctene analogy is applied to the eight-membered CRS, one might expect cis amide geometry to predominate. This is not what has been observed experimentally in the PDB. Investigations into proteins that carry the CRS reveal that this motif is important for activity.3 The central focus of this study is to assess how CRS conformation affects the redox potential of the disulfide-bond. Our central hypothesis is that a CRS with a cis peptide bond should be much more reducing (low redox potential) than a CRS with a trans peptide bond.

In order to test this hypothesis, cis and trans substrates were constructed in both oxidized (1 and 2) and reduced forms (10 and 13). Both systems have a central bond (cis/trans-olefin) with restricted geometry that mimics the 0° and 180° amide conformations of a cis and trans CRS. The synthesis of these compounds has not been reported previously, though the theoretical value for the redox potential of 1 has been calculated.4

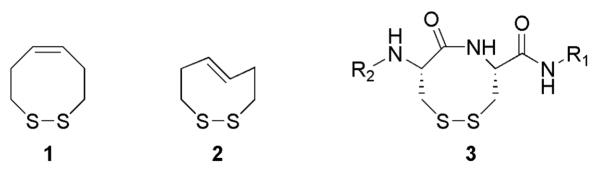

Retrosynthetically, dithiocines 1 and 2 are available upon intramolecular oxidation of the appropriate dithiol precursor. Originally the dithiol substrates were to be constructed via dithioureic salt 6. However, while the synthesis of 6 was non-problematic, the harsh conditions necessary for the generation of the dithiol led to significant by-product formation.5 This led to the use of dithioester 7 as the intermediary target, which could undergo saponification easily (Figure 2).6

Figure 2.

Retrosynthesis of Dithiocines

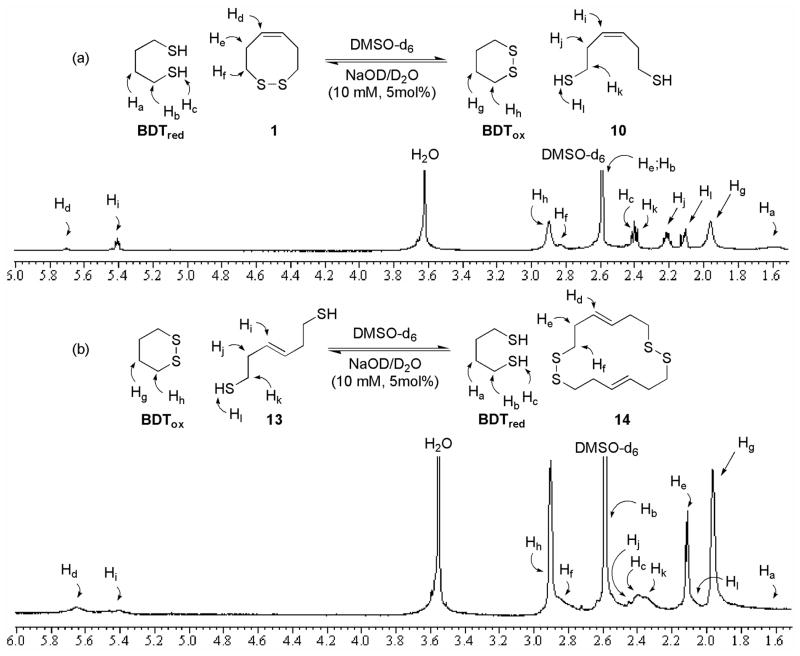

The redox properties were determined by thiol-disulfide exchange, with the varying concentrations of reduced and oxidized forms monitored by 1H-NMR (Figure 3).7 Employment of oxidized or reduced butane dithiol (BDTox and BDTred, respectively), a species of known redox potential (E0(BDT)), allows for the redox potential of the CRS mimics to be determined by equations 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

cis- and trans-Dithiol 1H-NMR Equilibrium Redox Experiment

| (1) |

| (2) |

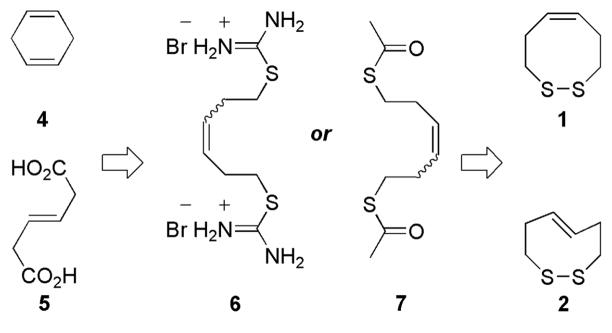

The synthesis of cis-dithiocine 1 begins with epoxidation of 1,4-cyclohexadiene to generate 8 almost quantitatively (Scheme 1).8 A subsequent one-pot protocol entails diol formation followed by oxidative ring cleavage and reduction of the intermediate acyclic dial to produce 9 in good overall yield.9 Formation of dithioester cis-7 occurs under Mitsunobu conditions,10 after which mild saponification affords dithiol 10.6 Air-oxidation mediated by CsF impregnated celite produced the desired cis-dithiocine 1.11 Disulfide formation does occur without the CsF-celite additive, however reaction times are significantly longer.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of cis-Dithiocine (1)

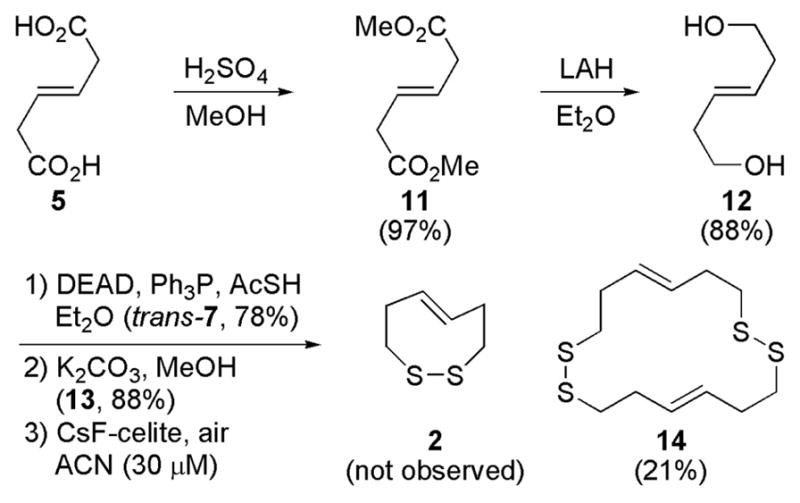

The synthesis of trans-dithiocine precursor 13 begins with trans-mucionic acid (Scheme 2). Methyl esterification and reduction generates trans-diol 12.12 Analogous to the construction of 1, Mitsunobu thioesterification and mild saponification affords trans-dithiol 13 in good overall yield. While formation of dithiol 13 was not troublesome, oxidative intramolecular construction of 2 was never realized even under dilute conditions. The only disulfide-bond containing compound isolated was that of cyclic-dimer 14.

Scheme 2.

Attempted Synthesis of trans-Dithiocine (2)

The redox potentials were then determined by equilibrium thiol-disulfide exchange. These redox experiments reached equilibrium in approximately 5 days in DMSO-d6. Integration of olefinic signals, as well as others, allowed for the respective redox potentials to be determined (Figure 3).13 This resulted in a derived cyclomonomeric redox potential of −0.311 ev for dithiol 10 (Figure 3a),14 which is in close agreement with the predicted redox potential for this compound.4 The cyclodimeric redox potential of trans-dithiol 13 was determined to be −0.329 ev (Figure 3b).15 The inability to determine the cyclomonomeric redox potential for the disulfide-bond of 2 alludes to its highly oxidative character.

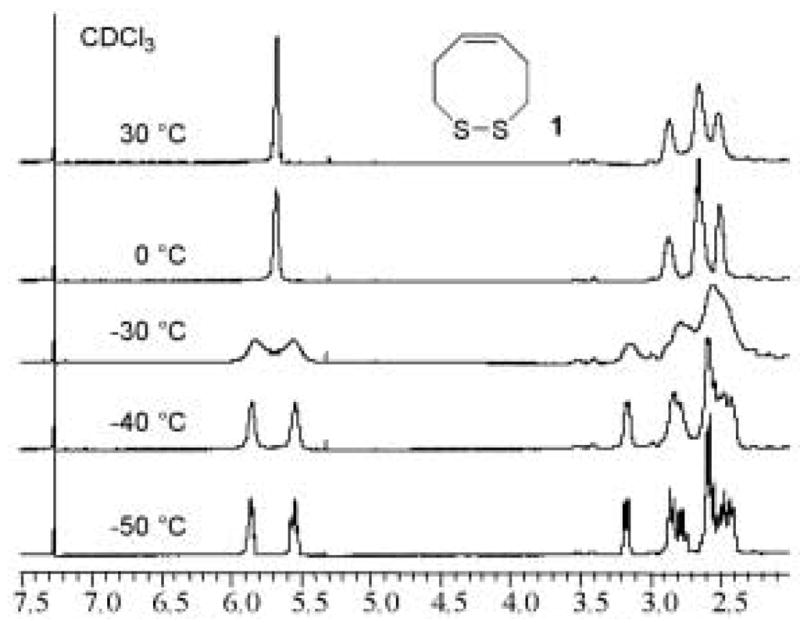

The ease of monomeric disulfide formation for the production of cis-dithiocine 1 (low redox potential) is due to (i) the very high collisional frequency of two sulfur-atoms in close proximity while in the cis configuration, and (ii) the lack of unfavorable non-bonded interactions.16 The inability to construct trans-dithiocine 2 is due to the remoteness of the sulfur-atoms in conjunction with the rigidity of the central olefinic bond. The higher monomeric redox potential of 13 is illustrated by its lack of ability to form a cyclic monomer and its propensity to dimerize as well as oligomerize. Upon disulfide-bond ring formation there is an absence of ring strain in incorporation of a cis-olefin in the eight-membered ring when compared to the trans isomer. As a result, cis-dithiocine 1 is much more stable than trans-dithiocine 2. The stability and absence of ring-strain in 1, when compared to 2, is also demonstrated via temperature dependent 1H-NMR coalescence experiments (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

1H-NMR Temperature Dependent Coalescence Experiment for cis-Dithiocine (1)

It is interesting to compare trans-dithiol 13 to that of a CRS found in proteins. A disulfide-bond can form between nearest neighbors because the peptide bond is not as rigid as an olefin. This allows the central peptide bond to “twist” slightly allowing disulfide-bond formation to occur with a strained transoid geometry. When the central torsional angle is constrained to 180°, as is the case for 13, disulfide-bond formation is impossible. Redox enzymes such as mammalian thioredoxin reductase may take advantage of the low redox potential of adjacent cysteine residues in a cis configuration which cycle between reduced and oxidized states.17 This is especially true for this enzyme since the redox pair occurs at the C-terminus, which would minimize the effect of a cisoid peptide bond on the main chain.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant GM070742 to RJH. ELR was supported by NIH grant PHS T32 HL07594.

References and Notes

- 1.Hudáky I, Gáspári Z, Carugo O, Čemžar M, Pongor S, Perczel A. Proteins: Struct, Func Bioinf. 2004;55:152–168. doi: 10.1002/prot.10581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers DW, von Voithenberg H, Allinger NL. J Org Chem. 1978;43:360–361. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carugo O, Čemžar M, Zahariev S, Hudáky I, Gáspári Z, Perczel A, Pongor S. Protein Eng. 2003;16:637–639. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns JA, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6296–6303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai Y-H, Soo T-B. Heterocycles. 1985;23:1205–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redman JE, Sanders JKM. Org Lett. 2000;2:4141–4144. doi: 10.1021/ol006615i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houk J, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:6825–6836. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman N, Albeck A. Syn Commun. 2000;30:4443–4449. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamoto K, Terashima S. Chem Pharm Bull. 1984;32:4340–4349. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobbs AP, Guesné SJJ, Martinović S, Coles SJ, Hursthouse MB. J Org Chem. 2003;68:7880–7883. doi: 10.1021/jo034981k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah STA, Khan KM, Fecker M, Voelter W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:6789–6791. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gassman PG, Bonser SM, Mlinarić-Majerski J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:2652–2662. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redox experiments were conducted under dry Ar, with reagents and solvents of reagent grade. Solvent deoxygenation was accomplished by sparging with Ar (30 min.), followed by sonication (10 min.) at aspirator pressure. Standard Redox Procedure: Dithiocine 1 (1.0 eq.) and BDTred (1.64 eq.) were combined in DMSO-d6. Residual O2 was removed by Ar-sparging for 30 min. A 10 mM NaOD/D2O (5 mol% NaOD) was then added. The redox experiment was monitored by 1H-NMR and reached equilibrium in 5 days. 10: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.49 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2 H), 2.72 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 4 H), 2.47 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 4 H), 1.25 (br s, 2 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 128.9 (CH), 38.4 (CH2), 27.2 (CH2); HRMS (EI) m/z 148.0382 [(M+) calcd. for C6H12S2: 148.0380]. 1: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.67 (m, 2 H), 2.87 (br s, 2 H), 2.64 (br s, 4 H), 2.50 (br s, 2 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 129.7 (CH), 39.4 (CH2), 27.2 (CH2); HRMS (EI) m/z 146.0225 [(M+) calcd. for C6H10S2: 146.0224]. 13: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.47 (m, 2 H), 2.57 (q, J = 7.7 Hz, 4 H), 2.33 (m, 4 H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 128.9 (CH), 38.4 (CH2), 27.2 (CH2); HRMS (EI) m/z 148.0379 [(M+) calcd. for C6H12S2: 148.0380]. 14: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.62 (m, 4 H), 2.79 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 8 H), 2.40 (m, 8 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 129.8 (CH), 39.7 (CH2), 31.8 (CH2); HRMS (EI) m/z 292.0446 [(M+) calcd. for C12H20S4: 292.0448].

-

14.The redox potential of 10 was determined by integration of Hd, Hc, Hj and Hg

1H-NMR signals (Figure 3a), which led to a ratio of 1.00:1.64:3.60:3.60 (1:BDTred:10:BDTox). Equilibrium concentrations were then determined by comparison of the equilibrium ratio to initial concentrations of 1 and BDTred. Insertion into equation 2 produces:

-

15.The redox potential of 13 was determined by integration of Hd, Hc, Hi and Hg

1H-NMR signals (Figure 3b), which led to a ratio of 1.00:2.00:1.11:1.93 (14:BDTred:13:BDTox). Equilibrium concentrations were then determined by comparison of the equilibrium ratio to initial concentrations of 13 and BDTox. Use of a cyclodimeric derived form of equation 2 produces:

- 16.Zhang R, Snyder GH. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18472–18479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandalova T, Zhong L, Lindqvist Y, Holmgren A, Schneider G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9533–9538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171178698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]