Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a recently characterized family of immune cells that play critical roles in cytokine-mediated regulation of intestinal epithelial cell barrier integrity1–10. Alterations in ILC responses are associated with multiple chronic human diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), implicating a role for ILCs in disease pathogenesis3,8,11–13. Due to an inability to selectively target ILCs, experimental studies assessing their function have predominantly employed mice lacking adaptive immune cells1–10. However, in lymphocyte-sufficient hosts ILCs are vastly outnumbered by CD4+ T cells, which express similar profiles of effector cytokines. Therefore, the function of ILCs in the presence of adaptive immunity and their potential to influence adaptive immune cell responses, remains unknown. To test this, we employed genetic or antibody-mediated depletion strategies to target murine ILCs in the presence of an adaptive immune system. Loss of retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan receptor-γt-positive (RORγt+) ILCs was associated with dysregulated adaptive immune cell responses against commensal bacteria and low-grade systemic inflammation. Remarkably, ILC-mediated regulation of adaptive immune cells occurred independently of IL-17A, IL-22 or IL-23. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling and functional analyses revealed that RORγt+ ILCs express major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) and can process and present antigen. However, rather than inducing T cell proliferation, ILCs acted to limit commensal-bacteria specific CD4+ T cell responses. Consistent with this, selective deletion of MHCII in murine RORγt+ ILCs resulted in dysregulated commensal bacteria-dependent CD4+ T cell responses that promoted spontaneous intestinal inflammation. These data identify that ILCs maintain intestinal homeostasis through MHCII-dependent interactions with CD4+ T cells that that limit pathologic adaptive immune cell responses to commensal bacteria.

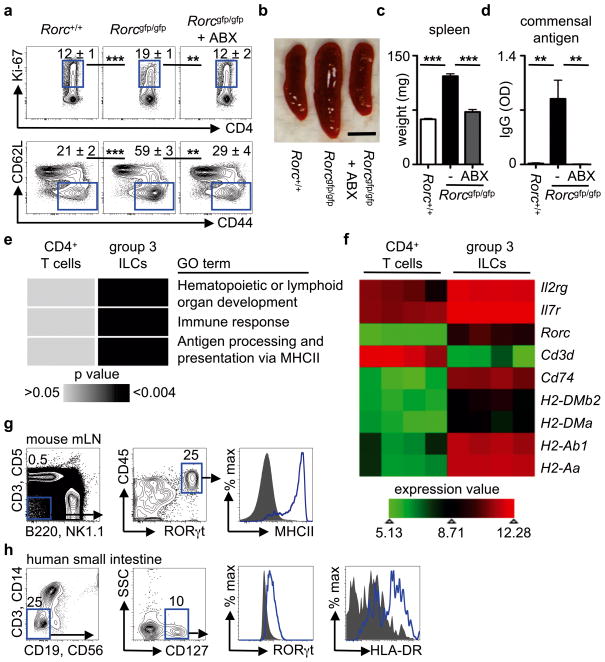

ILCs are a heterogeneous population of innate immune cells that can be grouped based on their expression of, and developmental requirements for, specific transcription factors and cytokines1,8–10. Group 1 ILCs depend on T-bet and express IFN-γ, while group 2 ILCs depend on RORα and GATA3 and express IL-5, IL-13 and amphiregulin1,8–10. Group 3 ILCs critically depend on RORγt for their development and in response to IL-23 stimulation produce the effector cytokines IL-17A and IL-22, which directly regulate innate immunity, inflammation and anatomical containment of pathogenic and commensal bacteria in the intestine1,8–10,14. However, the function of group 3 ILCs in the presence of adaptive immunity, and whether ILCs can influence adaptive immune cell responses, is unknown. To test this, adaptive immune cell responses were examined in mice lacking RORγt (Rorcgfp/gfp). In comparison to control mice, Rorcgfp/gfp mice exhibited significantly increased frequencies of peripheral proliferating Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells and effector/effector memory CD44high CD62Llow CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1a) and developed splenomegaly (Fig. 1b, c), indicative of disrupted immune cell homeostasis. Rorcgfp/gfp mice also exhibited elevated commensal bacteria-specific serum IgG (Fig. 1d), suggesting that commensal bacteria were promoting activation of adaptive immune cells in the absence of RORγt. Consistent with this, oral administration of ABX to Rorcgfp/gfp mice was associated with significantly reduced peripheral Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells and CD44high CD62Llow CD4+ T cells, spleen size and weight and commensal bacteria-specific serum IgG (Fig. 1a–d). As T cells also express RORγt and RORγt-deficient mice exhibit several developmental abnormalities6,15,16, we employed CD90-disparate chimeras to allow transient depletion of CD90.2+ ILCs, but not CD90.1+ T cells3,7. Depletion of ILCs in CD90-chimeric mice with an anti-CD90.2 monoclonal antibody resulted in significantly increased frequencies of dysregulated CD4+ T cells, increased spleen weight and elevated commensal bacteria-specific serum IgG responses (Fig. S1a–d), suggesting a critical role for ILCs in the regulation of inflammatory adaptive immune cell responses to commensal bacteria. Unexpectedly, IL-22-, IL-17A- and IL-23-deficient mice did not exhibit altered CD4+ T cell responses, splenomegaly or elevated commensal bacteria-specific serum IgG (Fig. S2a–c). Further, transient blockade of IL-22, IL-17A, IL-23 or IL-17RA in C57BL/6 mice also failed to exacerbate adaptive immune cell responses to commensal bacteria (Fig. S2d–i), suggesting that ILCs regulate adaptive immune cell responses independently of effector cytokines.

Figure 1. RORγt+ ILCs regulate adaptive immune cell responses to commensal bacteria and are enriched in MHCII-associated genes.

a–d, Defined age- and sex-matched mouse strains were examined for the frequency of splenic Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells (top) and CD44high CD62Llow CD4+ T cells (bottom) (a), spleen size (b), spleen weight (c) and relative optical density (OD) values of serum IgG specific to commensal bacteria (d). Antibiotics (ABX) were administered in the drinking water from weaning until 6–8 weeks of age. Scale bar represents 0.5 cm (b). Flow cytometry plots are gated on live CD4+ CD3+ T cells (a). e, f, DAVID pathway analysis of GO terms enriched in the transcriptional profiles of naïve CD4+ T cells and group 3 RORγt+ ILCs (e) and heat map of selected lymphoid-associated and MHCII-associated gene transcripts (f). g, h, Gating strategy for ILCs and expression of RORγt and MHCII in ILCs from the mesenteric lymph node of naïve RORγt-eGFP reporter mice (g) and the small intestine of healthy humans (h). Blue line = ILCs, Grey fill = negative control population. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments containing 3–5 mice per group or 4 human donors. Results are shown as the means ± s.e.m. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed students t-test).

To identify the mechanisms by which RORγt+ group 3 ILCs regulate commensal bacteria-responsive adaptive immune cells, genome-wide transcriptional profiles of RORγt+ ILCs were compared to naïve CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1e, f). Analysis of the top differentially expressed transcripts in RORγt+ group 3 ILCs revealed a significant enrichment for genes involved in pathways of ‘hematopoietic or lymphoid organ development’ and ‘immune response’ (Fig. 1e), consistent with previous analyses of RORγt+ ILCs17,18. Intriguingly, an additional pathway that was highly enriched in the transcriptional profile of group 3 ILCs was ‘antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen via MHCII’ (Fig. 1e). Indeed, relative to naïve CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1f) and previously published arrays of in vitro generated T helper 17 cells19 (Fig. S3), group 3 ILCs were highly enriched in transcripts involved in MHCII antigen processing and presentation pathways, such as Cd74, H2-DMb2, H2-DMa, H2-Ab1 and H2-Aa. Consistent with these transcriptional analyses, MHCII protein was detected on gated lineage− CD45+ RORγt+ ILCs from the mesenteric lymph node (mLN) of naïve RORγt-eGFP reporter mice (Fig. 1g). Critically, MHCII protein was also identified on gated lineage− CD127+ RORγt+ ILCs from the small intestine of healthy humans (Fig. 1h). Collectively, these results indicate that group 3 RORγt+ ILCs in the intestinal and lymphoid tissues of healthy mice and humans express MHCII.

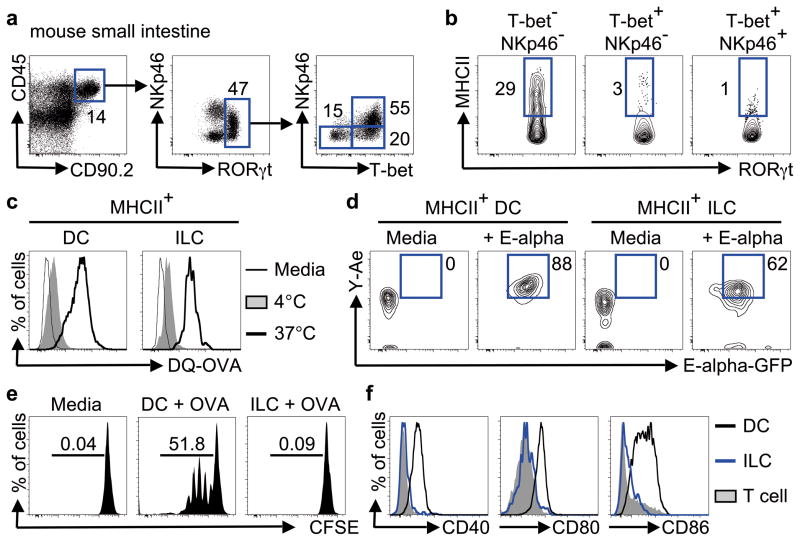

To interrogate whether MHCII expression was restricted to group 3 ILCs total lineage- CD45+ CD90.2+ ILCs in the murine small intestine were subdivided into group 1, 2 and 3 ILCs by expression of their defining transcription factors (Fig. 2a–b and S4a–e). Group 1 ILCs (RORγt- T-bet+ NKp46+/−) were found to lack MHCII expression (Fig. S4d–f), whereas group 2 ILCs (GATA-3+) expressed intermediate levels of MHCII (Fig. S4c). Microarray analyses confirmed the enrichment of MHCII-associated genes in group 3 ILCs versus previously published arrays of group 1 ILCs, such as NK cells20 (Fig. S5a) and group 2 ILCs17 (Fig. S5b). Significant heterogeneity exists within RORγt+ group 3 ILCs and three subgroups can be identified based on expression of NKp46 and T-bet (Fig. 2a)9,10,21. MHCII was found to be highly expressed on RORγt+ ILCs that lacked expression of both T-bet and NKp46, while minimal expression of MHCII was observed on RORγt+ T-bet+ NKp46− ILCs and RORγt+ T-bet+ NKp46+ ILC subsets (Fig. 2b) isolated from the small intestine of naïve mice. Consistent with this, previously published microarray data profiling ILCs based on NKp46 and RORγt expression18 also revealed an enrichment of MHCII-associated genes in RORγt+ ILCs that lacked NKp46 and T-bet expression (Fig. S5c). Furthermore, MHCII+ RORγt+ ILCs were found in lymphoid tissues at steady state (Fig. S6), exhibited homogenous expression of CD127, CD90.2, CD25, CCR6, c-kit, CD44 and heterogeneous expression of Sca-1 and CD4 (Fig. S7a) and produced IL-22, but not IL-17A or IFN-γ, in response to IL-23 stimulation (Fig. S7b).

Figure 2. T-bet− NKp46− RORγt+ ILCs express MHCII and process and present antigen.

a, b, Gating strategy (a) and expression of MHCII (b) in group 3 ILC subsets in the small intestine of naïve mice. c, d Sorted cell populations were cultured in the absence (thin line) or presence of DQ-OVA at 4°C (shaded) or 37°C (thick line) (c) or cultured in the absence (media) or presence of E-alpha-GFP protein and stained with Y-Ae antibody (d). e, Sort-purified CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from OTII mice were cultured in the presence of media alone or with OVA-pulsed DCs or OVA-pulsed ILCs. f, Expression of co-stimulatory molecules on DCs (black line), ILCs (blue line) or T cells (shaded) from the mLNs of naïve mice. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments containing 2–5 mice per group or 2–3 in vitro replicates.

To interrogate the functional capacity of MHCII+ ILCs, cells were sort-purified and cultured with DQ-Ovalbumin (DQ-OVA), a self-quenching conjugate of ovalbumin that fluoresces upon proteolytic degradation. MHCII+ ILCs exhibited an increase in fluorescence intensity comparable to CD11c+ MHCII+ dendritic cells (DCs) following incubation with DQ-OVA (Fig. 2c), indicative of an ability to acquire and degrade antigens. Sort-purified ILCs were also cultured with GFP-labeled E-alpha (Eα) protein and stained with an antibody specific for Eα derived Eα52–68 peptide bound to I-Ab molecules (Y-Ae). MHCII+ ILCs incubated with GFP-Eα exhibited positive GFP fluorescence and staining for Y-Ae at levels comparable to that of CD11c+ MHCII+ DCs (Fig. 2d), demonstrating ILCs can process exogenous protein and present peptide antigen in the context of MHCII. However, in contrast to OVA-pulsed DCs that induced multiple rounds of OT-II CD4+ T cell proliferation, OVA-pulsed ILCs failed to induce OT-II CD4+ T cell proliferation (Fig. 2e). Consistent with this, MHCII+ RORγt+ ILCs lacked expression of the classical co-stimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86, relative to DCs (Fig. 2f). Antigen presentation in the absence of co-stimulatory molecules has been proposed to limit T cell responses22, suggesting MHCII+ RORγt+ ILCs may negatively regulate CD4+ T cell responses in vivo. To test this, ILCs were pulsed with the commensal bacteria-derived antigen CBir123 and co-transferred with CBir1-specific transgenic T cells into naïve congenic mice, prior to systemic challenge with peptide (Fig. S8a). Mice that received a co-transfer of CBir1-specific T cells with peptide-pulsed ILCs exhibited a reduced population expansion of transferred T cells and decreased antigen-specific IFN-γ production relative to transfer of T cells alone (Fig. S8b–d), suggesting antigen presentation by ILCs limits CD4+ T cell responses in vivo.

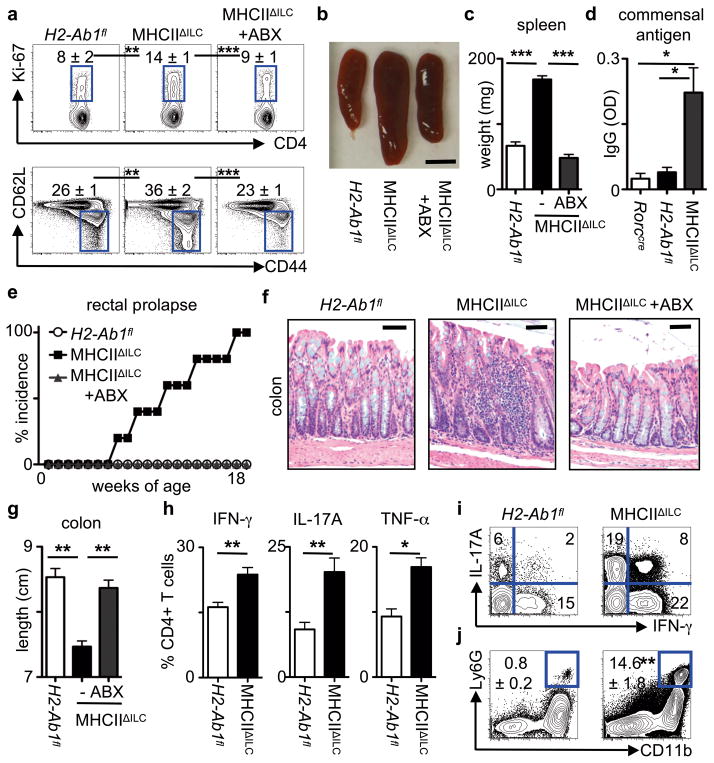

To further investigate the ability of MHCII+ RORγt+ ILCs to regulate adaptive immune cell responses, mice were generated with a RORγt+ ILC-intrinsic deletion of MHCII (MHCIIΔILC) by crossing mice with a floxed H2-Ab1 gene (H2-Ab1floxed) with mice expressing cre recombinase under control of the Rorc promoter (Rorccre) (Fig. S9a). Given that Rorc is expressed only by T cells and ILCs15,16 and that murine T cells do not express MHCII24, this permitted selective genetic deletion of MHCII in RORγt+ ILCs in the presence of an intact adaptive immune system. Consistent with this, MHCIIΔILC mice exhibited a selective loss of MHCII expression on RORγt+ ILCs while B cells, DCs and macrophages retained comparable expression levels of MHCII relative to control H2-Ab1floxed mice (Fig. S9b). MHCIIΔILC mice also had comparable peripheral numbers of LNs and Peyer’s patch, frequencies of ILCs and production of ILC-derived IL-22 (Fig. S9c, d) as compared to control mice. However, MHCIIΔILC mice did exhibit significantly increased frequencies of peripheral Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells and CD44high CD62Llow CD4+ T cells, increased spleen size and weight and a significant increase in commensal bacteria-specific serum IgG, which were abrogated upon oral administration of antibiotics (Fig. 3a–d). Thus, loss of ILC-intrinsic MHCII expression recapitulated the phenotype observed following genetic or antibody-mediated depletion of ILCs (Fig. 1a–d and Fig. S1a–d) and identifies a critical role for MHCII+ ILCs in regulating T cell responses to commensal bacteria.

Figure 3. Loss of RORγt+ ILC-intrinsic MHCII results in commensal bacteria-dependent intestinal inflammation.

a–d, Age- and sex-matched mice were examined for the frequency of splenic Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells (top) and CD44high CD62Llow CD4+ T cells (bottom) (a), spleen size (b), spleen weight (c) and relative serum IgG specific to commensal bacteria (d). Scale bar represents 0.5 cm (b). Flow cytometry plots are gated on live CD4+CD3+ T cells (a). e–g, Mice were examined for incidence of rectal prolapse (e), histological changes in H&E stained sections of the terminal colon (f) and colon length (g). Scale bars represent 25 μm (f). Antibiotics (ABX) were continuously administered in the drinking water of selected mice at weaning until 8–18 weeks of age. h–j, Frequency of total IFN-γ+, IL-17A+ and TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells (h) and IL-17A+ IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells (i) in the colons following a brief ex vivo stimulation and frequency of CD11b+ Ly6G+ neutrophils in colonic lamina propria (j). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments containing 3–5 mice per group. Results are shown as the means ± s.e.m. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed students t-test).

Inappropriate host inflammatory responses to commensal bacteria are associated with the pathogenesis and progression of numerous chronic human diseases3,11–13, therefore MHCIIΔILC mice were examined at various ages for signs of inflammation. MHCIIΔILC mice were observed to develop rectal prolapse, beginning at approximately 8 weeks of age and reaching a 100 percent incidence by 18 weeks of age (Fig. 3e). Further examination revealed that MHCIIΔILC mice exhibited intestinal inflammation characterized by crypt elongation, loss of normal architecture and significantly decreased colon length (Fig. 3f, g). Intestinal inflammation in MHCIIΔILC mice could be prevented by continuous administration of antibiotics (Fig. 3e–g), demonstrating a critical role for commensal bacteria in the development of disease. Moreover, MHCIIΔILC mice exhibited significantly elevated frequencies of IFN-γ +, IL-17A+ and TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells in the colon (Fig. 3h) including CD4+ T cells that co-produced IFN-γ and IL-17A (Fig. 3i), which was associated with significant recruitment of neutrophils into the colonic lamina propria (Fig. 3j). Further phenotypic and functional analyses suggested that the increased pro-inflammatory CD4+ T cell responses and intestinal inflammation that developed in the absence of ILC-intrinsic MHCII were not the result of impaired regulatory T cell function or regulatory cytokine production (Fig. S10), altered thymic selection (Fig. S11) or commensal microflora dysbiosis (Fig. S12). Collectively, these data suggest ILCs directly limit commensal bacteria-responsive CD4+ T cells through MHCII-dependent interactions.

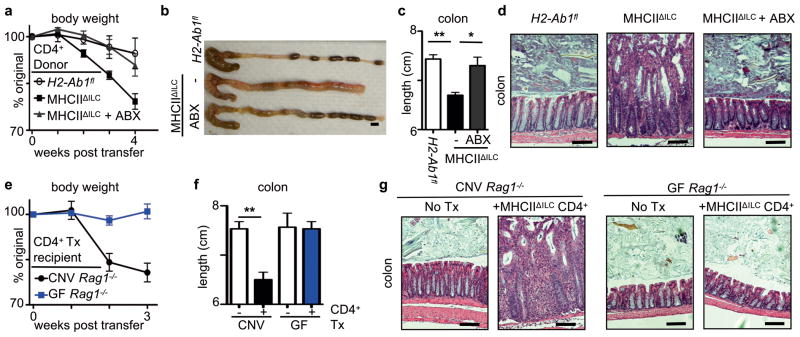

To determine whether dysregulated CD4+ T cell responses to commensal bacteria directly mediated intestinal inflammation observed in MHCIIΔILC mice, sort-purified CD4+ T cells from control H2-Ab1floxed mice or MHCIIΔILC mice were transferred into Rag1−/− mice. In comparison to Rag1−/− recipients receiving CD4+ T cells from control mice, Rag1−/− recipients receiving CD4+ T cells from MHCIIΔILC mice exhibited rapid and substantial weight loss (Fig. 4a), colonic shortening, macroscopic intestinal thickening and severe intestinal inflammation characterized by crypt elongation, loss of normal architecture and inflammatory cell infiltrates (Fig. 4b–d). Critically, oral administration of antibiotics to MHCIIΔILC donor mice prior to CD4+ T cell isolation abrogated the ability of CD4+ T cells to elicit wasting disease and intestinal inflammation in naïve Rag1−/− recipients (Fig. 4a–d). Similarly, germ-free Rag1−/− recipients of CD4+ T cells from MHCIIΔILC mice did not develop wasting disease or intestinal inflammation in comparison to conventional Rag1−/− recipients (Fig. 4e–g). Therefore, in the absence of RORγt+ ILC-intrinsic MHCII, commensal bacteria are required for both the development of pathologic CD4+ T cell responses and for the onset of wasting disease and intestinal inflammation.

Figure 4. RORγt+ ILC-intrinsic MHCII regulates pathologic CD4+ T cell responses to commensal bacteria.

a–d, Rag1−/− mice received CD4+ T cells sort-purified from defined donor mouse strains or e–g conventional (CNV) and germ-free (GF) Rag1−/− mice received sort-purified CD4+ T cells from MHCIIΔILC mice (+/−Tx). Recipients were examined for changes in weight (a, e), macroscopic colon pathology (b), colon length (c, f) and histological changes in the terminal colon (d, g). Scale bars represent 0.5 cm (b) or 25 μm (d, g). In some experiments antibiotics (ABX) were administered in the drinking water of donor mice from weaning (a–d). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments containing 3–5 mice per group. Results are shown as the means ± s.e.m. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 (two-tailed students t-test).

Collectively, these data identify a previously unrecognized role for RORγt+ ILCs in maintaining intestinal homeostasis by limiting pathologic CD4+ T cell responses to commensal bacteria through MHCII-dependent interactions (Fig. S13). MHCII expression was found to be restricted to a subset of CCR6+ RORγt+ ILCs that lack T-bet and IFN-γ expression and thus, are phenotypically and functionally distinct from RORγt+ ILC populations that have been linked with promoting intestinal inflammation in murine models and IBD patients2,11. Rather, MHCII+ RORγt+ ILCs appear more similar to IL-22 producing ILC populations previously shown to promote tissue protection3,5,8,12,13,14. In a developmental context, it is remarkable that RORγt+ ILCs are the first cells of the immune system to colonize the neonatal intestine and gut-associated lymphoid tissues15,25,26. Therefore, ILCs may play a critical role not only in promoting lymphoid organogenesis and cytokine-mediated epithelial cell barrier integrity, but also in regulating adaptive immune cell responses to newly colonizing commensal bacteria. It may also be advantageous for ILCs to modulate commensal bacteria-specific T cells as, in contrast to professional antigen presenting cells, murine ILCs lack expression of TLRs, conventional co-stimulatory molecules and do not produce cytokines that regulate T cell differentiation1,8,10,25. The demonstration that ILCs regulate adaptive immune cell responses to commensal bacteria through MHCII expression may be of importance in understanding the pathogenesis of numerous chronic human diseases associated with inflammatory host immune responses to commensal bacteria.

Methods

Mice, antibiotics and use of monoclonal antibodies in vivo

C57BL/6 mice, C57BL/6 Rag1−/−, C57BL/6 CD90.1 and C57BL/6 Rorcgfp/gfp mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), bred and maintained at the University of Pennsylvania. C57BL/6 Il17a−/− mice were kindly provided by Y. Iwakura (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan), C57BL/6 Il22−/− mice were provided by Pfizer, Il23a−/− mice were provided by Janssen Research & Development LLC, H2-Ab1floxed mice were provided by P. A. Koni, tissues from CBir1 TCR transgenic mice were provided by C. O. Elson, and Rorccre mice and Rorc(γt)-GfpTG were provided by G. Eberl. All mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities at the University of Pennsylvania. Germ-free C57BL/6 and C57BL/6 Rag1−/− mice were provided by the University of Pennsylvania Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility. CD90-disparate Rag1−/− chimeras were constructed as previously described3,7. All protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and all experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the University of Pennsylvania IACUC. A previously described cocktail of antibiotics was continuously administered via drinking water for defined periods of time3,27. Anti-CD90.2 mAb (30H12) was purchased from BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH). Anti-IL-22 mAbs, IL22-01 (neutralizing) and IL22-02 (mouse cytokine detection) were developed by Pfizer. Anti-IL-17A mAb (CNTO 8096) and anti-IL-23p19 mAb (CNTO 6163) were developed by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. Anti-IL-17RA mAb was developed by Amgen Inc. Neutralizing or depleting monoclonal antibodies were administered i.p. every 3 days at a dose of 250 μg/mouse starting on day 0 and ending on day 14.

Murine tissue isolation and flow cytometry

Spleens, LNs and Peyer’s patches were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were prepared at necropsy. For intestine lamina propria lymphocyte preparations, intestines were isolated, attached fat removed and tissues cut open longitudinally. Luminal contents were removed by shaking in cold PBS. Epithelial cells and intra-epithelial lymphocytes were removed by shaking tissue in stripping buffer (1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 5% FCS) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The lamina propria layer was isolated by digesting the remaining tissue in 0.5 mg/mL collagenase D (Roche) and 20 μg/mL DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C.

For flow cytometric analyses, cells were stained with antibodies to the following markers: anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136, eBioscience), anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11, eBioscience), anti-CD5 (clone 53–7.3, eBioscience), anti-CD90.2 (clone 30-H12, Biolegend), anti-CD127 (clone A7R34, eBioscience), anti-CD11c (clone N418, eBioscience), anti-F4/80 (clone BM8, eBioscience), anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5, Abcam), anti-CD8 (clone 53–6.7, eBioscience), anti-B220 (clone RA3-6B2, eBioscience), anti-CD25 (clone eBio3C7, eBioscience), anti-MHCII (clone M5/114.15.2, eBioscience), anti-CD44 (clone IM7, eBioscience), anti-CD62L (clone MEL-14, eBioscience), anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11, eBioscience), anti-NKp46 (clone 29A1.4, eBioscience), anti-CD11b (clone M1/70, eBioscience), anti-CD117 (c-kit) (clone 2B8, eBioscience), anti-Sca-1 (clone D7, eBioscience), anti-CD40 (clone 1C10, eBioscience), anti-CD80 (clone 16-10A1, eBioscience), anti-CD86 (clone GL1, BD Biosciences), anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8, BioLegend) and anti-CCR6 (clone 29-2L17, BioLegend). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized utilizing a commercially available kit (eBioscience) and stained with anti-RORγt (clone B2D, eBioscience), anti-FoxP3 (clone FJK016s, eBioscience), anti-T-bet (clone eBio-4B10, eBioscience), anti-GATA-3 (clone TWAJ, eBioscience) or anti-Ki-67 (clone B56, BD Biosciences). For cytokine production, cells were stimulated ex vivo by incubation for 4 h with 50 ng/mL PMA, 750 ng/mL ionomycin, 10 μg/mL Brefeldin A (all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich) or 50 ng/mL rIL-23 (eBioscience) and 10 μg/mL Brefeldin A. Cells were fixed and permeabilized as indicated above and stained with IL22-02 (Pfizer) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 or Alexa Fluor 488 according to manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes), anti-IL-17A (clone eBioTC11-18H10.1, eBioscience), anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2, eBioscience) and anti-TNF-α (clone MP6-XT22, eBioscience). Dead cells were excluded from analysis using a violet viability stain (Invitrogen). T cell V β chain usage was assessed using a commercial mouse V β TCR screening panel (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data collection was performed on a LSR II (BD Biosciences) and cell sorting performed on an Aria II (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.).

Human intestinal samples and flow cytometry

Human intestinal tissues from the ileum were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network. Single cell suspensions from intestinal tissues were obtained by cutting tissues into small pieces and incubating for 1–2 h at 37°C with shaking in stripping buffer (1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 5% FCS) to remove the epithelial layer. Supernatants were then discarded, and the lamina propria fraction was obtained by incubating the remaining tissue for 1–2 h at 37°C with shaking in collagenase solution. Remaining tissues were then mechanically dissociated, filtered through a wire mesh tissue sieve, and lymphocytes were subsequently separated by Ficoll gradient.

For flow cytometry, cells were stained with antibodies to the following markers: anti-CD3 (clone UCHT1, eBioscience), anti-CD56 (clone CMSSB, eBioscience), anti-CD19 (clone 2H7, eBioscience), anti-HLA-DR (clone LN3, eBioscience), anti-CD127 (clone A019D5, Biolegend). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized utilizing a commercially available kit (eBioscience) and stained with anti-RORγt (clone AFKJS-9, eBioscience) and anti-IL-22 (clone 22URTI, eBioscience). Dead cells were excluded from analysis using a viability stain (Invitrogen). Flow cytometry data was collected using a LSR II (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.).

Histological sections

Tissue samples from the intestines of mice were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and 5 μm sections were stained with H&E.

Microarray and DAVID pathway analysis

Microarray gene expression profiling and data normalization for group 2 ILCs (sorted Lineage-, CD90.2+, CD25+ ILCs from the lungs of naïve C57BL/6 mice), group 3 ILCs (Lineage-, CD90.2+, CD4+ ILCs from the spleens of naïve C57BL/6 mice) and naïve splenic CD4+ T cells was performed as previously described (GSE46468 and GSE30437), data was RMA-normalized and SAM analysis was performed17. Additional microarray gene expression profiling were obtained from GEO for previously published studies of in vitro polarized Th17 cells (GSM1074979, GSM1075001 and GSM1075002)19, splenic NK cells (GSM538315, GSM538316 and GSM538317)20 and subsets of RORγ+ ILCs isolated from naïve murine small intestine (GSM739586, GSM739591, GSM739588, GSM739593, GSM739589 and GSM739594)18. GEO datasets were batch-corrected to existing microarray gene expression profiles using ComBat28. Differentially expressed genes in the transcriptional profiles of specified groups were uploaded to the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/)29 and analyzed as previously described17 using the Fisher’s exact test to identify significantly enriched Gene Ontology (GO, http://www.geneontology.org) terms29. Heat maps displaying key genes were generated using Mayday software30.

Antigen processing and presentation analyses

2 ×103 sort-purified CD11c+ MHCII+ DCs and Lineage- CD127+ c-kit+ MHCII+ ILCs were cultured with 10 μg/ml DQ-OVA (Molecular Probes) at 4°C or 37°C for 3 hours, extensively washed and fluorescence assessed via flow cytometry. Alternatively, antigen processing and presentation was assessed using a previously defined self-antigen E-alpha31. Briefly, 2 ×103 sort-purified DCs and ILCs were pulsed for 3 hours in complete media with 50 μg/ml GFP-labeled E-alpha protein, extensively washed and stained with a biotin-conjugated antibody recognizing Eα52–68 peptide bound to I-Ab (clone Yae, eBioscience) followed by a streptavidin APC (eBioscience) and uptake of antigen and peptide-MHCII complex presentation assessed via flow cytometry. In some assays 2 ×103 sort-purified DCs or ILCs were pulsed with 50 μg ovalbumin for 2 hours prior to incubation with 2 ×104 sort-purified CFSE-labeled OT-II T cells. Cell co-cultures were incubated for 72 hours prior to analysis via flow cytometry.

T cell adoptive transfer

2 ×106 CD4+ CD3+ T cells were sorted from the spleen and mLN of control or experimental mice to a purity > 97% and transferred i.v. to naïve C57BL/6 Rag1−/− recipient mice (GF or CNV). Weights of recipient mice were monitored through the progression of the experiment.

CBir1-specific T cell transfers

1 ×106 CBir1 TCR transgenic T cells were transferred into congenically marked hosts with or without co-transfer of 8 ×103 sort-purified ILCs (Lineage-, CD127+, c-kit+) pulsed with 1 μg/ml CBir1456–475 peptide. 24 hours later mice were administered 50 μg CBir1456–475 peptide i.p. and 72 hours later mice were euthanized and the presence of CBir1 TCR transgenic T cells were quantified in the spleen. IFN-γ production was quantified by culturing 1 ×106 splenocytes in the presence of 1 μg/mL CBir1456–475 peptide for 48 hours.

Regulatory T cell suppression assay

CD11c+ DCs, naïve CD4+ CD25− CD45RBhi Teff cells and CD4+ CD25+ CD45RB- Treg were sort-purified from the spleen and mLN of MHCIIΔILC mice and littermate controls. Sort-purified Treg were found to be at least 98% FoxP3+. DCs were plated at 5 ×103/well in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml soluble purified anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11, BD Biosciences). Teff were CFSE labeled and added to wells containing DCs at 2.5 ×104 alone, or with Treg at a ratio of 1:0, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8 and 1:16. Following 3 days culture at 37°C/5% CO2 cell-culture supernatants were harvested and Teff proliferation was measured by CFSE dilution via flow cytometry. Treg suppression was calculated by gating on T effector cells and quantifying the percent CFSE-dim in comparison to cells cultured in the absence of Tregs.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from whole colon tissue that was homogenized and snap frozen in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA was isolated as per manufacturers instructions and cDNA generated using Superscript reverse transcription (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed on cDNA using SYBR green chemistry (Applied Biosystems) using commercially available primer sets (QIAGEN). Reactions were run on a real-time PCR system (ABI7500; Applied Biosystems). Samples were normalized to β-actin and displayed as a fold change as compared to control mice.

Commensal bacteria-specific ELISA

Colonic fecal contents were homogenized and briefly centrifuged at 1,000 rpm to remove large aggregates, and the resulting supernatant was washed with sterile PBS twice by centrifuging for 1 minute at 8,000 rpm. On the last wash, bacteria were resuspended in 2 mL ice-cold PBS and sonicated on ice. Samples were then centrifuged at 20,000 x g for 10 minutes, and supernatants recovered for a crude commensal bacteria antigen preparation. For measurement of serum antibodies by ELISA, 5 μg/mL commensal bacteria antigen was coated on 96 well plates, and sera were incubated in doubling dilutions. Antigen specific IgG was detected using an anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody (BD Biosciences). Plates were developed with TMB peroxidase substrate (KPL), and optical densities measured using a plate spectrophotometer.

Microbiota transfer to germ free mice

The ceca of MHCIIΔILC mice and littermate controls were opened under aseptic conditions and cecal contents resuspended in sterile PBS. Germ free C57BL/6 mice were then orally gavaged with 200 μl of cecal content suspension and subsequently monitored over the course of six weeks for signs of disease and rectal prolapse prior to sacrifice.

Pyrosequencing

DNA from luminal contents from the large intestine of mice was obtained using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN). DNA samples were amplified using the V1-V2 region primers targeting bacterial 16S genes and sequenced using 454/Roche Titanium technology. Sequence analysis was carried out using the QIIME pipeline32 for co-housed cohorts of H2-Ab1floxed and MHCIIΔILC mice.

Statistical analysis

Results represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Sonnenberg and Artis labs for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank H.L. Ma, L.A. Fouser, S. Olland, R. Zollner, K. Lam and A. Root at Pfizer for critical discussions, valuable advice and the preparation of IL-22 antibodies, M.M. Elloso at Janssen Research & Development for critical discussions, valuable advice and the preparation of IL-17 and IL-23 antibodies and M.S. Marks for kindly providing the E-alpha protein and Y-Ae antibody. The research is supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI061570, AI087990, AI074878, AI095776, AI102942, AI095466, AI095608 and AI097333 to D.A.; T32-AI055428 to L.A.M.; DK071176 to C.O.E.; and DP5OD012116 to G.F.S.), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (to D.A.) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award (to D.A.). We also thank the Matthew J. Ryan Veterinary Hospital Pathology Lab, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Center for the Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Disease Molecular Pathology and Imaging Core (P30DK50306), the Penn Microarray Facility and the Abramson Cancer Center Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Resource Laboratory (partially supported by NCI Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant (#2-P30 CA016520)) for technical advice and support. Human tissue samples were provided by the Cooperative Human Tissue Network, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations used

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature

Author contributions

M.R.H., L.A.M., T.C.F., D.A. and G.F.S. designed and performed the research. C.G.K.Z. performed analyses of microarray data. A.C., J.M.A. and E.J.W. performed the microarray of naïve CD4+ T cells. S.G., R.S. and F.D.B. provided valuable advice, performed and analyzed 454 pyrosequencing of intestinal commensal bacteria. A.R.M. assisted with reagents and advice for antigen presentation assays. H.L.M, P.A.K., C.O.E. and G.E. provided essential mouse strains, valuable advice and technical expertise for theses studies. M.R.H., L.A.M., T.C.F., D.A. and G.F.S. analyzed the data. M.R.H., D.A. and G.F.S. wrote the manuscript.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:647–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buonocore S, et al. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnenberg GF, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote anatomical containment of lymphoid-resident commensal bacteria. Science. 2012;336:1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1222551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cella M, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawa S, et al. RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal homeostasis by integrating negative signals from the symbiotic microbiota. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:320–326. doi: 10.1038/ni.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lochner M, et al. Microbiota-induced tertiary lymphoid tissues aggravate inflammatory disease in the absence of RORgamma t and LTi cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:125–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Elloso MM, Fouser LA, Artis D. CD4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. Immunity. 2011;34:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cell interactions with microbiota: implications for intestinal health and disease. Immunity. 2012;37:601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spits H, et al. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:145–149. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker JA, Barlow JL, McKenzie AN. Innate lymphoid cells--how did we miss them? Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:75–87. doi: 10.1038/nri3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geremia A, et al. IL-23-responsive innate lymphoid cells are increased in inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1127–1133. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takayama T, et al. Imbalance of NKp44(+)NKp46(−) and NKp44(−)NKp46(+) natural killer cells in the intestinal mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:882–892. 892 e881–883. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciccia F, et al. Interleukin-22 and IL-22-producing NKp44(+) NK cells in the subclinical gut inflammation of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 doi: 10.1002/art.34355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eberl G, Littman DR. Thymic origin of intestinal alphabeta T cells revealed by fate mapping of RORgammat+ cells. Science. 2004;305:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1096472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawa S, et al. Lineage Relationship Analysis of ROR{gamma}t+ Innate Lymphoid Cells. Science. 2010 doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monticelli LA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynders A, et al. Identity, regulation and in vivo function of gut NKp46+RORgammat+ and NKp46+RORgammat- lymphoid cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:2934–2947. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yosef N, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling T17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezman NA, et al. Molecular definition of the identity and activation of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1000–1009. doi: 10.1038/ni.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klose CS, et al. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:261–265. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz RH. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19256–19261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benoist C, Mathis D. Regulation of major histocompatibility complex class-II genes: X, Y and other letters of the alphabet. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:681–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mebius RE, Rennert P, Weissman IL. Developing lymph nodes collect CD4+CD3- LTbeta+ cells that can differentiate to APC, NK cells, and follicular cells but not T or B cells. Immunity. 1997;7:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberl G, et al. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abt MC, et al. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2012;37:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8:118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang da W, et al. Extracting biological meaning from large gene lists with DAVID. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009;Chapter 13(Unit 13):11. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1311s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battke F, Symons S, Nieselt K. Mayday--integrative analytics for expression data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy DB, et al. A novel MHC class II epitope expressed in thymic medulla but not cortex. Nature. 1989;338:765–768. doi: 10.1038/338765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.