Abstract

Study Objectives:

Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy (ADCA-DN) is caused by DNMT1 mutations. Diagnosing the syndrome can be difficult, as all clinical features may not be present at onset, HLA-DQB1*06:02 is often negative, and sporadic cases occur. We report on clinical and genetic findings in a 31-year-old woman with cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy, and discuss diagnostic challenges.

Design:

Clinical and genetic investigation in a patient and family members.

Setting:

Ataxia clinic, São Paulo, Brazil.

Patients or Participants:

One patient and her family members.

Interventions:

N/A.

Measurements and Results:

Narcolepsy was supported by polysomnographic and multiple sleep latency testing. HLA-DQB1*06:02 was positive. CSF hypocretin-1 was 191 pg/mL (normal values > 200 pg/mL). Mild brain atrophy was observed on MRI, with cerebellar involvement. The patient, her asymptomatic mother, and 3 siblings gave blood samples for genetic analysis. DNMT1 exons 20 and 21 were sequenced. Haplotyping of polymorphic markers surrounding the mutation was performed. The proband had a novel DNMT1 mutation in exon 21, p.Cys596Arg, c.1786T > C. All 4 parental haplotypes could be characterized in asymptomatic siblings without the mutation, indicating that the mutation is de novo in the patient.

Conclusions:

The Brazilian patient reported here further adds to the worldwide distribution of ADCA-DN. The mutation is novel, and illustrates a sporadic case with de novo mutation. We believe that many more cases with this syndrome are likely to be diagnosed in the near future, mandating knowledge of this condition and consideration of the diagnosis.

Citation:

Pedroso JL; Barsottini OGP; Lin L; Melberg A; Oliveira ASB; Mignot E. A novel de novo exon 21 DNMT1 mutation causes cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy in a Brazilian patient. SLEEP 2013;36(8):1257-1259.

Keywords: Narcolepsy, cerebellar ataxia, deafness, novel DNMT1 mutation, de novo

INTRODUCTION

Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy (ADCA-DN, MIM 604121) was first described in a Swedish pedigree.1,2 ADCA-DN is characterized by narcolepsy (with low CSF hypocretin-1), followed by deafness, ataxia, and finally dementia. Peripheral neuropathy, psychosis, and optic atrophy also occur later in the course of the disease. Exome sequencing in individuals from 3 ADCA-DN kindreds identified DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 as the causative gene.3 DNMT1 is widely expressed targeting hemi-methylated loci, resulting in transcriptional repression. Its crystal structure is known, and regulation is complex.4 Interestingly, all mutations producing this phenotype in 4 families were located in exon 21, in the regulatory replication foci targeting sequence (RFTS) domain of the protein.3 Klein et al.5 reported 2 mutations in exon 20 (also in the RFTS domain) causing hereditary sensory neuropathy (HSN1E, MIM 614116), dementia, and hearing loss, a syndrome characterized first by a severe peripheral neuropathy (typically resulting in limb amputation) and deafness, followed by dementia and variably cerebellar ataxia.5 Herein, we describe a patient with sporadic late age of onset of narcolepsy, cerebellar ataxia, and hearing loss, with a novel de novo mutation in exon 21.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 31-year-old woman of Italian descent presented with ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy. She had a 10-year history of narcolepsy treated with methylphenidate 20 mg daily. She denied cataplexy, hallucinations, or sleep paralysis. Polysomnographic and multiple sleep latency testing were consistent with narcolepsy (mean sleep latency 1.3 minutes and 5 sleep onset REM periods in 5 naps). HLA-DQB1*06:02 was positive. At age 24, she started to have tinnitus and progressive hearing loss, diagnosed by audiogram as of sensory origin. Gait instability occurred progressively over the last 6 years. She also had primary amenorrhea. The patient denied memory loss or psychiatric symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. FSH, estradiol, LH, testosterone, and thyroid axis values were within normal range. Neurological examination showed moderate axial and appendicular ataxia, mild vertical nystagmus, and absent lower limb tendon reflexes, but no sensory deficits, ulcerations, lymphedema, or optic atrophy. Mild brain atrophy was observed on MRI, with cerebellar involvement. CSF hypocretin-1 was 191 pg/mL (normal values > 200 pg/mL), indicating low to intermediary decreased levels, as found in other cases at this stage of the disease.3

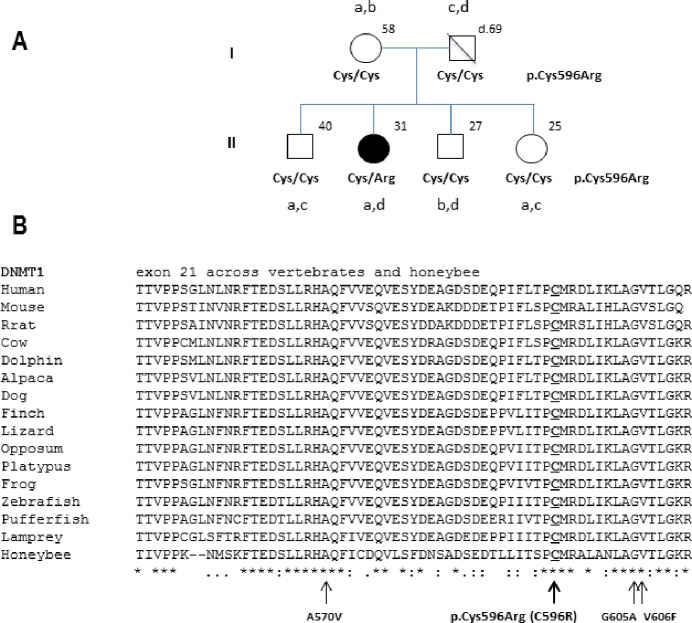

DNMT1 exon 20 and exon 21 were sequenced. A non-synonymous mutation p.Cys596Arg (NM_001130823.1: c.1786T > C) was found in exon 21, substituting a conserved cysteine residue by arginine. This mutation was not found in 90 controls sequenced previously and in the 1000 genomes. The mother and 3 siblings were tested and had wild-type alleles (Figure 1). Haplotyping of 14 markers surrounding the mutation indicated de novo status for c.1786T > C in the proband (Figure 1 and Table S1). The father died at age 69 from laryngeal cancer and had no neurological symptoms.

Figure 1.

Novel DNMT1 mutation causing cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy in a Brazilian female patient. (A) Pedigree with p.Cys596Arg amino acid change in the affected proband and 5 marker haplotypes (a, b, c, d) derived using surrounding the mutation. Haplotypes were derived using rs8112063, rs7710, rs3826784, rs2290684, and rs7253062 (see Table S1). Note that all 4 parental haplotypes could be characterized in asymptomatic siblings without the mutation, indicating that the mutation is de novo in the patient. (B) Exon 21 of DNMT1 gene with arrows indicating the four mutations so far found in ADCA-DN patients and an overview of the degree of conservation of the region containing the four known mutations. p.Cys596Arg is the new mutation described in our patient.

DISCUSSION

The novel de novo DNMT1 mutation described here is remarkable as it further demonstrates that another exon 21 mutation of the DNMT1 RFTS domain causes cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy. Consistent with the likely disruptive effect of this polar substitution, onset was similar to that of patients with p.Val606Phe and earlier than in patients with p.Ala570Val and p.Gly605Ala mutations.3 In all ADCA-DN patients with exon 21 mutations3 and unlike in HSN1E patients with exon 20 mutations,5 peripheral neuropathy is a late symptom, whereas narcolepsy and cerebellar ataxia are consistent symptoms. Deafness is also present as an early symptom, while dementia occurs later in the disease, with optic atrophy and other symptoms. It remains to be seen if narcolepsy is also a variable or later onset feature of exon 20 HSN1E mutations, as in 3 cases in a multiplex pedigree, occasional somnolence in the fifth decade was noted.6

How these mutations could induce late onset neurodegeneration is unknown. Both hyper- and hypomethylation have been shown to induce neuronal cell death in various models.7,8 The DNMT1 RFTS domain is inhibitory, thus impairment would likely produce hypermethylation, a gain of function consistent with the dominant effect of these mutations. In its biochemical studies of exon 20 mutations, Klein et al.5 mostly found decreased enzyme activity, and decreased genome wide methylation using the bisulfide technique. A suggestion of impaired nuclear localization of the mutant protein was also found indicating decreased activity.5 Interestingly, however, selected CpG island loci displayed significantly increased methylation, loci that could be more important functionally. Clarifying whether these mutations lead to increased or decreased function, or off-target methylation (hemi-methyl-ated versus un-methylated DNA for example), together with the identification of target genes relevant to the phenotype will likely be essential to the design of future therapies for these patients.

Since the discovery of the cause of this syndrome in 4 families with three mutations in exon 21, one more multigenerational family with the syndrome was also discovered in the UK (John Ealing, Personal communication) and found to have p.Ala570Val, a mutation already reported in two other pedigrees.3 Together with the report described here, a total of six families with 4 distinct mutations (2 de novo mutations, 4 auto-somal dominant pedigrees) in exon 21 have been found to cause ADCA-DN, with onset of the full syndrome at age 30-50. All cases progress to dementia not otherwise specified, but without Lewy body or amyloid plaques at autopsy. We believe that many more such families will be identified in the future.

The most striking feature of the syndrome may be the earlier onset of narcolepsy without cataplexy (sleepiness with rapid transitions into REM sleep during the MSLT) up to 20 years before the onset of the other symptoms. At this early stage, the diagnosis is unlikely to be made, as this is a common diagnosis without major health consequences. At a later stage, narcolepsy may manifest unusually with cataplexy in a middle age subject with deafness and/or ataxia, often without DQB1*06:02 (a marker of sporadic autoimmune narcolepsy-cataplexy), and with intermediary CSF hypocretin-1 levels.3,9 Associated psychiatric presentations such as psychosis or depression are possible. MRI may show minor cerebellar and supratentorial atrophy, pronounced dilatation of the third ventricle, low T2-signal intensity in the basal ganglia, and loss of cerebral cortex-white matter differentiation.2 Neurological examination can be borderline abnormal, suggesting cerebellar ataxia, mild peripheral neuropathy, or other abnormalities. Assessment of visual acuity, pupils, peripheral vision, color vision, electroretinography, visual evoked potential, and optical coherence tomography may also reveal early signs consistent with progressing optic nerve atrophy. Early recognition of this syndrome will likely be important in the future, as therapy, if efficacious, will be needed early to delay onset of the fatal symptoms.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Haplotypes surrounding the p.Cys596Arg mutation in the family

REFERENCES

- 1.Melberg A, Hetta J, Dahl N, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia deafness and narcolepsy. J Neurol Sci. 1995;134:119–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melberg A, Dahl N, Hetta J, et al. Neuroimaging study in autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy. Neurology. 1999;53:2190–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkelmann J, Lin L, Schormair BR, et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2205–10. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frauer C, Leonhardt H. Twists and turns of DNA methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8919–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105804108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein CJ, Botuyan MV, Wu Y, et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy with dementia and hearing loss. Nat Genet. 2011;43:595–600. doi: 10.1038/ng.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hojo K, Imamura T, Takanashi M, et al. Hereditary sensory neuropathy with deafness and dementia: a clinical and neuroimaging study. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6:357–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.1999.630357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chestnut BA, Chang Q, Price A, Lesuisse C, Wong M, Martin LJ. Epigenetic regulation of motor neuron cell death through DNA methylation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16619–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1639-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutnick LK, Golshani P, Namihira M, et al. DNA hypomethylation restricted to the murine forebrain induces cortical degeneration and impairs postnatal neuronal maturation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2875–88. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melberg A, Ripley B, Lin L, Hetta J, Mignot E, Nishino S. Hypocretin deficiency in familial symptomatic narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:136–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Haplotypes surrounding the p.Cys596Arg mutation in the family