Abstract

Background:

Cisplatin (CP) is an effective drug in cancer therapy to treat the solid tumors, but it is accompanied with nephrotoxicity. The protective effect of estrogen in cardiovascular diseases is well-documented; but its nephron-protective effect against CP-induced nephrotoxicity is not completely understood.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty ovarectomized Wistar rats were divided in to five groups. Groups 1-3 received different doses of estradiol valerate (0.5, 2.5 and 10 mg/kg/week) in sesame oil for 4 weeks, and at the end of week 3, a single dose of CP (7 mg/kg, intraperitoneal [IP]) was administrated. Group 4 (positive control) received the same regimen as group 1-3 without estradiol without vehicle. The negative control group (Group 5) received sesame oil during the study. The animals were sacrificed 1 week after CP injection for histopathological studies.

Results:

The serum level of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, kidney tissue damage score (KTDS), kidney weight and percentage of body weight change in CP-treated groups significantly increased (P < 0.05), however, there were no significant differences detected between the estrogen-treated groups (Groups 1-3) and the positive control group (Group 4). Although, estradiol administration enhanced the serum level of nitrite, it was not affected by CP. Finally, significant correlation between KTDS and kidney weight was detected (r2 = 0.63, P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

Estrogen is not nephron-protective against CP-induced nephrotoxicity. Moreover, it seems that the mechanism may be related to estrogen-induced oxidative stress in the kidney, which may promote the nephrotoxicity.

Keywords: Cisplatin, estrogen, nephrotoxicity, ovarectomized rat

INTRODUCTION

Cisplatin (CP), as an anti-tumor drug, is widely used for cancer therapy and due to its accumulation in kidney, nephrotoxicity is the most common side-effect of CP administration.[1,2,3] In past years, different kind of antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, aminoguanidine or quercetin,[4,5,6,7,8,9] renin-angiotensin receptor blocker; losartan,[10] or even magnesium[11] have been proposed to be nephron-protective against nephrotoxicity induced by CP.

The incidence of chronic renal diseases is gender-related, and is potentially higher in males.[12,13] It is also found that CP-induced nephrotoxicity has different trends in the two genders.[14,15] Accordingly, experimental study indicates that urine sodium excretion in male animal is more than that in female ones, when CP was administrated.[16] The mechanism for this gender-related difference is not well- understood, but estrogen may play an important role.

The protective role of estrogen in cardiovascular diseases is reputed. However, its protective role against CP-induced nephrotoxicity is not well-documented. Estrogen receptors may be disturbed by CP, and the steroid hormone affects function of CP.[17] Previously, it was reported that estrogen enhance oxidative stress in the kidney,[18] and accordingly, it promotes kidney toxicity in proximal tubules in animal models.[19,20] Therefore, we hypothesized that estrogen is not nephron-protective when accompanied with CP, and may also potentially promote CP-induced nephrotoxicity. To examine this hypothesis, different doses of estrogen were administered to ovarectomized rats treated with CP and the results were compared with positive and negative control groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Thirty adult female Wistar rats (Animal Centre, Ahvaz University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran) with the mean weight of 156.8 g ± 2.8 g were used. The rats were individually housed at a temperature of 23-25°C. Rats had free access to water and chow. The experimental procedures were in advance approved by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee.

Experimental protocol

The animals were anesthetized with ketamine (75 mg/kg, IP). An incision of length of about 2 cm was made in the sub-abdominal area. The abdominal muscles were opened and intestine was sheared off. The uterus tube and vascular base of ovaries were twisted, and the ovaries were removed. The muscles and skin were replaced back and were stitched, and animals were let for recovery in room temperature under heat lamp. After recovery, the animals were allowed to acclimatize to the regular diet for 1 week. Then, they were randomly divided in to five experimental groups. Groups 1, 2, and 3 were subjected to receive 0.5, 2.5, and 10 mg/kg/week, intramuscular (IM) estradiol valerate (Aburaihan Co, Tehran, Iran) in sesame oil for 3 weeks, and at the end of week 3, the animals received single dose of CP (7 mg/kg body wt. IP). CP (cis-Diammineplatinum (II) dichloride, code P4394) was purchased from Sigma (Germany). Group 4 (positive control) received the same regimen as group 1-3 without estradiol valerate without vehicle. Group 5, as the negative control group, received sesame oil in equal volume during the study. One week after CP injection, blood samples were obtained and the rats were sacrificed. Kidneys were removed and weighted immediately, and were prepared for histopathological procedures and the uterus was also removed and weighed.

Measurements

The levels of serum creatinine (Cr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were determined using quantitative diagnostic kits (Pars Azmoon, Iran). The serum level of nitrite (stable nitric oxide (NO) metabolite) was measured using a colorimetric ELISA kit (Promega Corporation, USA) that involves the Griess reaction. Briefly, sulphanilamide solution was added to the sample and after incubation, N-1-naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride solution was added. Then, the absorbance was measured by a microreader, and the nitrite concentration of the sample was determined by comparison with nitrite standard reference curve. The serum level of estradiol was measured using enzyme immunoassay ELISA kit (Diagnostics Biochem Canada Inc., Canada).

Histopathological procedures

The kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral formalin solution and embedded in paraffin for staining. The tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined. The extent of tubular damage was evaluated by two independent pathologists. The pathologists were totally blind to the study. Based on the intensity of tubular lesions (hyaline cast, debris, vacuolization, flattening and degeneration of tubular cells, and dilatation of tubular lumen), kidney tissue damage score (KTDS) was graded from 1 to 5, while score zero was assigned to normal tubules without any damage.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM the percentage (%) of changes in the body weight, the serum levels of BUN, Cr, and NO; and the kidney and the uterus weights in each estradiol-treated groups were compared with those of the positive and negative control groups using two-way Student t-test. The same comparison was applied to KTDS using Mann-Whitney analysis. To determine the correlation between kidney weight and KTDS, the non-parametric Spearman correlation test was applied. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of cisplatin on serum blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and nitrite levels

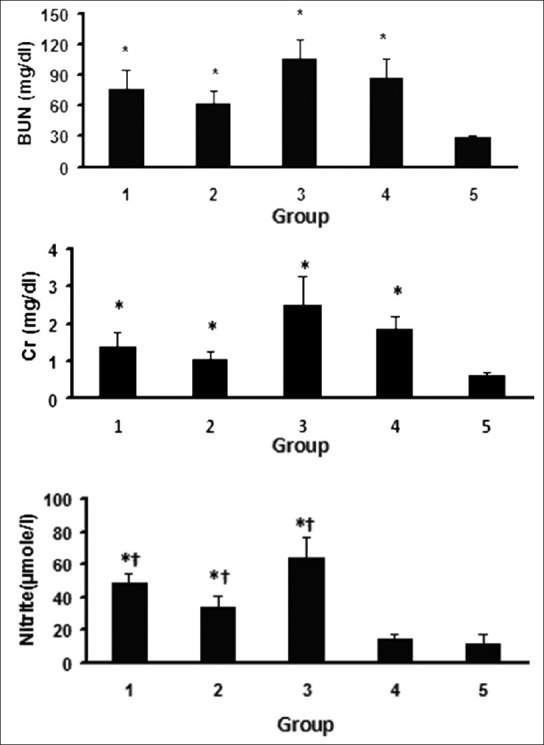

The CP-induced nephrotoxicity was confirmed by increase in BUN and Cr concentrations in serum (P < 0.05) [Figure 1]. Accordingly, the serum levels of BUN and Cr in estradiol-treated animals (Groups 1-3) were significantly higher than those in the negative control group (P < 0.05). However, the values were not significantly different from those obtained for the positive control group. Due to estradiol administration, the serum level of nitrite in the estradiol-treated groups was higher than those in the positive and negative control groups (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the serum nitrite level was detected between the positive and the negative control groups; therefore, the serum level of nitrite was not affected by CP.

Figure 1.

Serum level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr) and nitrite. The star (*) and (†) indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) when compared with the negative and the positive control groups, respectively. For the serum levels of BUN and Cr, no significant differences were detected between Groups 1 and 4

Effect of CP on sex hormone level and uterus weight

The serum level of estradiol was determined (Group 1: 116.7 ± 21.9 ng/ml, Group 2: 706.8 ± 320.7 ng/ml, Group 3: 2907.9 ± 606.7 ng/ml, Group 4: 25.6 ± 4.6 ng/ml, and Group 5: 25.8 ± 5.7 ng/ml). An expected significant difference in estradiol level was detected among the groups (P < 0.05), which was related to the estrogen administration. The uterus weight in the estradiol-treated animals were significantly greater than that in the positive and negative control groups (Group 1: 0.103 ± 0.014, Group 2: 0.123 ± 0.014, Group 3; 0.112 ± 0.015, Group 4: 0.032 ± 0.007, and Group 5: 0.017 ± 0.002 g/100 g body weight, P < 0.05).

Effect of CP on body weight

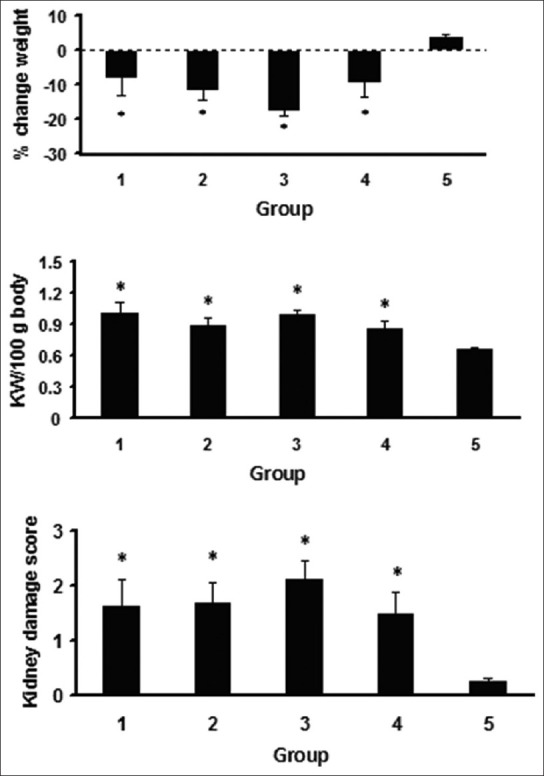

CP-treated animals lost weight during the experiment. The weight loss percentages in CP-treated animals were significantly different from that in the negative control group (P < 0.05). No significant difference was observed between each of estrogen-treated groups and the positive control group (P < 0.05) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The percentage (%) of change weight, total kidney weight/100 gr body weight, and the kidney tissue damage score. The star (*) indicates significant difference (P < 0.05) when compared with negative control group. For the above parameters, no significant differences were detected among Groups 1-4

Effect of CP on kidney damage

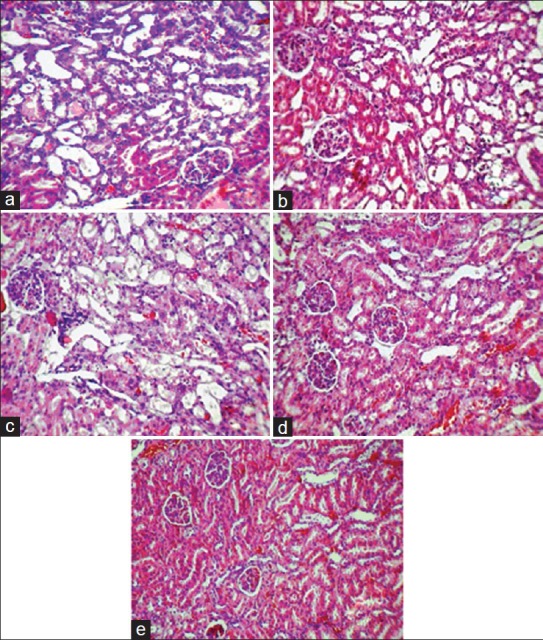

The data for KTDS and kidney weight are demonstrated in Figure 2. The KTDS and kidney weight were significantly different in the CP-treated groups when compared with the negative control group (P < 0.05). These parameters were not statistically different in comparison with the positive control group. A significant correlation was detected between the kidney weight and the KTDS (r2 = 0.63, P < 0.01). There results indicate no nephron-protective role for estrogen in CP-induced nephrotoxicity. The kidney tissue images from each group are demonstrated in [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Images (magnification ×100) of kidney tissue. (a) Group 1; low- dose of estradiol + cisplatin, (b) Group 2; mid dose of estradiol + cisplatin, (c) Group 3; high- dose of estradiol + cisplatin, (d) Group 4; vehicle + cisplatin, (e) Group 5; sesame oil. Higher tissue damage was observed in estrogen-treated and positive control groups

DISCUSSION

Estrogen has protective role on cardiovascular system,[21,22,23,24,25,26,27] however, its protective role in CP-induced nephrotoxicity is not well-established. The main objective of this study was to determine the role of estrogen in CP-induced nephrotoxicity.

The weight loss due to gastrointestinal disturbance,[28,29,30] the kidney damage and the kidney weight gain,[31,32,33,16] and the increase in the serum levels of BUN and Cr[5,10,16,34] by administration of CP were reported by other investigators, and our findings are in agreement with these data. Furthermore, we did not find significant differences between the estradiol-treated groups (Groups 1-3), and the positive control group, in the serum levels of BUN and Cr. It is reported that estrogen enhances oxidative stress in the kidney,[18] and accordingly, it promote kidney toxicity in the proximal tubules.[19,20] Moreover, owing to the vasodilatory effect of estrogen, more CP may be transported to the kidney, and CP accumulates in the kidney tissue via basolateral membranes and destroys mitochondrial DNA, and finally causes tubular damage.[35,36,37] Estrogen receptors are available in the kidneys and may sensitize the tissue to CP[17] and promote the kidney damage. Therefore, our study showed that estrogen does not have protective effect on the kidney damage induced by CP. It also seems that the CP-induced nephrotoxicity gets enhanced in the presence of high-estrogen level.

The NO production is gender-related and estrogen itself increases the serum level of NO.[38,39,40] Furthermore, NO formation is implicated in the CP-induced nephrotoxicity;[41,42] and therefore, in the current study the increased level of nitrite in all the estradiol-treated groups may promote nephrotoxicity. In other word, estrogen promotes NO production, as was observed in Groups 1-3, and NO itself is implicated in CP-induced nephrotoxicity.

It is concluded that estrogen is not only nephron-protective in CP-induced nephrotoxicity model, but also may promote kidney toxicity in the presence of high- estrogen levels due to formation of oxidative stress. Thus, special attention is suggested during CP treatment when estrogen replacement therapy is also accompanied.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 290223).

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 290223).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGuinness SJ, Ryan MP. Mechanism of cisplatin nephrotoxicity in rat renal proximal tubule suspensions. Toxicol in vitro. 1994;8:1203–12. doi: 10.1016/0887-2333(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Mechanisms of Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel) 2010;2:2490–518. doi: 10.3390/toxins2112490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos NA, Catão CS, Martins NM, Curti C, Bianchi ML, Santos AC. Cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity is associated with oxidative stress, redox state unbalance, impairment of energetic metabolism and apoptosis in rat kidney mitochondria. Arch Toxicol. 2007;81:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s00204-006-0173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajith TA, Abhishek G, Roshny D, Sudheesh NP. Co-supplementation of single and multi doses of vitamins C and E ameliorates cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009;61:565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antunes LM, Darin JD, Bianchi MD. Protective effects of vitamin c against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in adult rats: A dose-dependent study. Pharmacol Res. 2000;41:405–11. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appenroth D, Fröb S, Kersten L, Splinter FK, Winnefeld K. Protective effects of vitamin E and C on cisplatin nephrotoxicity in developing rats. Arch Toxicol. 1997;71:677–83. doi: 10.1007/s002040050444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atasayar S, Gürer-Orhan H, Orhan H, Gürel B, Girgin G, Ozgüneş H. Preventive effect of aminoguanidine compared to vitamin E and C on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009;61:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behling EB, Sendão MC, Francescato HD, Antunes LM, Costa RS, Bianchi Mde L. Comparative study of multiple dosage of quercetin against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative stress in rat kidneys. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58:526–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maliakel DM, Kagiya TV, Nair CK. Prevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by glucosides of ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2008;60:521–7. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleh S, Ain-Shoka AA, El-Demerdash E, Khalef MM. Protective effects of the angiotensin II receptor blocker losartan on cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Chemotherapy. 2009;55:399–406. doi: 10.1159/000262453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodnar L, Wcislo G, Gasowska-Bodnar A, Synowiec A, Szarlej-Wcisło K, Szczylik C. Renal protection with magnesium subcarbonate and magnesium sulphate in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer after cisplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy: A randomised phase II study. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2608–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang DH, Yu ES, Yoon KI, Johnson R. The impact of gender on progression of renal disease: Potential role of estrogen-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor regulation and vascular protection. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:679–88. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63155-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silbiger SR, Neugarten J. The role of gender in the progression of renal disease. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 2003;10:3–14. doi: 10.1053/jarr.2003.50001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei Q, Wang MH, Dong Z. Differential gender differences in ischemic and nephrotoxic acute renal failure. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:491–9. doi: 10.1159/000088171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wongtawatchai T, Agthong S, Kaewsema A, Chentanez V. Sex-related differences in cisplatin-induced neuropathy in rats. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:1485–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stakisaitis D, Dudeniene G, Jankūnas RJ, Grazeliene G, Didziapetriene J, Pundziene B. Cisplatin increases urinary sodium excretion in rats: Gender-related differences. Medicina (Kaunas) 2010;46:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Q, Liang CH, Lippard SJ. Steroid hormones induce HMG1 overexpression and sensitize breast cancer cells to cisplatin and carboplatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5768–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100108697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beleh MA, Lin YC, Brueggemeier RW. Estrogen metabolism in microsomal, cell, and tissue preparations of kidney and liver from Syrian hamsters. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;52:479–89. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00003-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butterworth M, Lau SS, Monks TJ. 2-Hydroxy- 4-glutathion-S-yl-17beta-estradiol and 2-hydroxy-1- glutathion-S-yl-17beta-estradiol produce oxidative stress and renal toxicity in an animal model of 17beta-estradiol-mediated nephrocarcinogenicity. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:133–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy D, Liehr JG. Target organ-specific inactivation of drug metabolizing enzymes in kidney of hamsters treated with estradiol. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;110:31–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02385003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho JJ, Cadet P, Salamon E, Mantione K, Stefano GB. The nongenomic protective effects of estrogen on the male cardiovascular system: Clinical and therapeutic implications in aging men. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:RA63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choudhry MA, Chaudry IH. 17beta-Estradiol: A novel hormone for improving immune and cardiovascular responses following trauma-hemorrhage. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:518–22. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubey RK, Jackson EK. Cardiovascular protective effects of 17beta-estradiol metabolites. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1868–83. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendelsohn ME. Protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(Suppl 1):12–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1801–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nematbakhsh M, Ghadesi M, Hosseinbalam M, Khazaei M, Gharagozloo M, Dashti G, et al. Oestrogen promotes coronary angiogenesis even under normoxic conditions. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;103:273–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nematbakhsh M, Khazaei M. The effect of estrogen on serum nitric oxide concentrations in normotensive and DOCA Salt hypertensive ovariectomized rats. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;344:53–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ammer U, Natochin Yu, David C, Rumrich G, Ullrich KJ. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: Site of functional disturbance and correlation to loss of body weight. Ren Physiol Biochem. 1993;16:131–45. doi: 10.1159/000173759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Endo Y, Kanbayashi H. Modified rice bran beneficial for weight loss of mice as a major and acute adverse effect of Cisplatin. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;92:300–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.920608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miya T, Goya T, Yanagida O, Nogami H, Koshiishi Y, Sasaki Y. The influence of relative body weight on toxicity of combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:386–90. doi: 10.1007/s002800050834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deegan PM, Nolan C, Ryan MP, Basinger MA, Jones MM, Hande KR. The role of the renin-angiotensin system in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Ren Fail. 1995;17:665–74. doi: 10.3109/08860229509037634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goren MP. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity affects magnesium and calcium metabolism. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41:186–9. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saad SY, Najjar TA, Daba MH, Al-Rikabi AC. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase aggravates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: Effect of 2-amino-4-methylpyridine. Chemotherapy. 2002;48:309–15. doi: 10.1159/000069714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleh S, El-Demerdash E. Protective effects of L-arginine against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and toxicity: Role of nitric oxide. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;97:91–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pabla N, Murphy RF, Liu K, Dong Z. The copper transporter Ctr1 contributes to cisplatin uptake by renal tubular cells during cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F505–11. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90545.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian W, Nishikawa M, Haque AM, Hirose M, Mashimo M, Sato E, et al. Mitochondrial density determines the cellular sensitivity to cisplatin-induced cell death. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1466–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00265.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao X, Panichpisal K, Kurtzman N, Nugent K. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: A review. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334:115–24. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31812dfe1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ha CS, Joo BS, Kim SC, Joo JK, Kim HG, Lee KS. Estrogen administration during superovulation increases oocyte quality and expressions of vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide synthase in the ovary. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:789–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kauser K, Rubanyi GM. Gender difference in bioassayable endothelium-derived nitric oxide from isolated rat aortae. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H2311–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.6.H2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kauser K, Rubanyi GM. Gender difference in endothelial dysfunction in the aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1995;25:517–23. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams C, McCarthy HO, Coulter JA, Worthington J, Murphy C, Robson T, et al. Nitric oxide synthase gene therapy enhances the toxicity of cisplatin in cancer cells. J Gene Med. 2009;11:160–8. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung M, Hotter G, Viñas JL, Sola A. Cisplatin upregulates mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase and peroxynitrite formation to promote renal injury. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;234:236–46. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]