Abstract

A wide range of molecular techniques have been developed for genotyping Candida species. Among them, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and microsatellite length polymorphisms (MLP) analysis have recently emerged. MLST relies on DNA sequences of internal regions of various independent housekeeping genes, while MLP identifies microsatellite instability. Both methods generate unambiguous and highly reproducible data. Here, we review the results achieved by using these two techniques and also provide a brief overview of a new method based on high-resolution DNA melting (HRM). This method identifies sequence differences by subtle deviations in sample melting profiles in the presence of saturating fluorescent DNA binding dyes.

1. Introduction

Candida species are opportunistic pathogens which can cause diseases ranging from mucosal infections to systemic mycoses depending on the vulnerability of the host. The major pathogen worldwide is Candida albicans [1, 2]. This fungus is detected in the body microbiota of healthy humans [3] and accounts for 75% of the organisms residing in the oral cavity [4]. It is diploid and has a largely clonal mode of reproduction. However, it can undergo considerable genetic variability either by gene regulation and/or genetic changes including chromosomal alterations, mutations, and loss of heterozygosity (LOH). In fact, LOH events lead to MTL homozygosis [5], azole resistance [6–8] and microevolution during infection [9–11], passage through a mammalian host [12], or in vitro exposure to physiologically relevant stresses [13].

Non-albicans Candida species such as Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, and Candida dubliniensis are also found with increasing frequency [14–17]. C. glabrata has been reported to be the second etiologic agent, after C. albicans, of superficial and invasive candidiasis in adults in the United States [18, 19], whereas, in Europe and Latin America, C. parapsilosis is the specie responsible for approximately 45% of all cases of candidemia [14, 20].

The ability to discriminate Candida isolates at the molecular level is crucial to better understand the spread of these species, particularly in hospitals and to assist in an early diagnosis and initiation of the appropriate antifungal therapy as these organisms show a range of susceptibilities to existing antifungal drugs. C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis remain susceptible to polyenes, azoles, and echinocandins [21]. However, C. glabrata and C. krusei show reduced triazole susceptibility [22, 23]. In addition, the majority of clade 1 isolates of C. albicans are less susceptible to flucytosine [24]. The faster and more accurate the species and strains can be identified, the greater the impact in the patient clinical response is. Several methods, such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, restriction enzyme analysis, Southern-blot assays, random amplified polymorphic DNA, and amplified fragment length polymorphism, were used to track differences among Candida isolates [25, 26]. However, these approaches have limitations such as time consuming, use of radioactive elements, poor reproducibility, and/or discriminatory power [25, 26]. In the present review, we summarize the most exact and/or recent DNA-based techniques developed for a better understanding of the epidemiology of Candida species. The availability of the C. albicans genome sequence [27–29] facilitated studies in comparative genomics and genome evolution.

2. Multilocus Sequence Typing

The multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is based on the analysis of nucleotide sequences of internal regions of various independent housekeeping genes. MLST studies for C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, and C. dubliniensis have been reported (reviewed in [30]). MLST of C. albicans was introduced during the early 2000s [31, 32]. On the basis of a collaborative work, an international consensus set of seven genes for C. albicans MLST have been proposed [33]. This gene set includes AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b (Table 1). MPIb has been renamed PMI1 [34]. Table 1 also shows primers for the amplification and sequencing of the seven gene fragments.

Table 1.

International consensus gene set used for C. albicans MLST analysis.

| Locus | Chromosome | Gene product | Primers | Sequenced fragment size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaAAT1a | 2 | Aspartate aminotransferase | F: ACTCAAGCTAGATTTTTGGC | 349 |

| R: CAGCAACATGATTAGCCC | ||||

| CaACC1 | R | Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase | F: GCAAGAGAAATTTTAATTCAATG | 407 |

| R: TTCATCAACATCATCCAAGTG | ||||

| CaADP1 | 1 | ATP-dependent permease | F: GAGCCAAGTATGAATGATTTG | 443 |

| R: TTGATCAACAAACCCGATAAT | ||||

| CaPMIb | 2 | Mannose phosphate isomerase | F: ACCAGAAATGGCCATTGC | 375 |

| R: GCAGCCATGCATTCAATTAT | ||||

| CaSYA1 | 6 | Alanyl-RNA synthetase | F: AGAAGAATTGTTGCTGTTACTG | 391 |

| R: GTTACCTTTACCACCAGCTTT | ||||

| CaVPS13 | 4 | Vacuolar protein sorting protein | F: TCGTTGAGAGATATTCGACTT | 403 |

| R: ACGGATGGATCTCCAGTCC | ||||

| CaZWF1b | 1 | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | F: GTTTCATTTGATCCTGAAGC | 491 |

| R: GCCATTGATAAGTACCTGGAT |

F and R indicate forward and reverse primers, respectively.

MLST system has proved to be a useful method for epidemiological differentiation of C. albicans clinical isolates [31, 32]. Indeed, isolations of C. albicans strains recovered from human patients seem to be specific to the patient but not associated with different anatomical sources or hospital origin [9, 10, 35, 36]. MLST studies also revealed a population structure with five major clades of closely related strain types (numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, and 11) plus various minor clades [37]. Clades do not represent cryptic species as genetic exchange between and within clades is limited [38]. Clade 1 is particularly rich in flucytosine-resistant isolates [39, 40]. All clade 1 flucytosine-resistant isolates carry a point mutation (R101C) in the FUR1 gene which encodes uridine phosphoribosyl transferase [40].

A potential weakness of the C. albicans international standard gene set is that three of the chromosomes are not represented and two gene pairs are located on the same chromosome (Table 1). In order to include highly informative polymorphisms, a MLST-biased single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray has been developed [41]. This system which includes 7 loci from the consensus scheme and 12 additional discrete loci located at intervals along the 8 chromosomes may provide a basis for a standardized system.

MLST schemes have been also reported for C. glabrata [42]. This typing system is based on fragments of six genes ([42], Table 2). Utilizing this MLST method, several studies have described the population structure of geographically diverse collections of C. glabrata isolates [43–45]. Recent MLST analysis of 230 isolates of C. glabrata from five populations that differed both geographically and temporally confirmed that the six unlinked loci provide genotypic diversity and differentiation among isolates of this species [46]. MLST studies also revealed that C. glabrata strains causing bloodstream infections have similar population structures and fluconazole susceptibilities compared to those normally residing in/on the host [47]. When susceptibility testing of colonizing isolates while receiving azole therapy was studied, MLST revealed the occurrence of resistance development far more frequently in C. glabrata than in any other species [48]. This resistance to azole prophylaxis has led to an increased use of echinocandin for primary therapy of C. glabrata infections. However, decreased susceptibility to echinocandin drugs can be observed among C. glabrata isolates with mutations in the FKS1 and FKS2 genes. These genes encode Fks1p and Fks2p subunits of the 1,3-β-glucan synthase complex, which synthesizes the principal cell wall component β-1,3-glucan, target of echinocandin drugs. In light of this, MLST analysis performed on isolates with FKS mutations indicated that the predominant S663P mutation in the FKS2 gene was not due to the clonal spread of a single resistant phenotype [49].

Table 2.

Summary of loci used for individual MLST schemes. Data for C. dubliniensis, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis are from McManus et al. [50], Dodgson et al. [42], Jacobsen et al. [51], and Tavanti et al. [52], respectively.

| Species | Locus | Gene product | Primers | Sequenced fragment size (bp) | Genotypes/site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. dubliniensis | CdAAT1a | Aspartate aminotransferase | F: ATCAAACTACTAAATTTTTGAC | 373 | 1.25 |

| R: CGGCAACATGATTAGCCC | |||||

| CdACC1 | Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase | F: GCCAGAGAAATTTTGATCCAATGT | 407 | 1.33 | |

| R: TTCATCAACATCATCCAAGTG | |||||

| CdADP1 | ATP-dependent permease | F: GAGCCAAGTATGAATGACTTG | 443 | 1.2 | |

| R: TTGATCAACAAACCCGATAAT | |||||

| CdPMIb | Mannose phosphate isomerase | F: ACCAGAAATGGCC | 375 | 3.5 | |

| R: GCAGCCATACATTCAATTAT | |||||

| CdRPN2 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit | F: TTTATGCATGCTGGTACTACTGATG | 302 | 1 | |

| R: TAACCCCATACTCAAAGCAGCAGCCT | |||||

| CdSYA1 | Alanyl-RNA synthetase | F: AGAAGAATAGTTGCTCTTACTG | 391 | 1 | |

| R: GTTGCCCTTACCACCAGCTTT | |||||

| CdVPS13 | Vacuolar protein sorting 13 | F: CGTTGAGAGATATTCGACTT | 403 | 1.33 | |

| R: ACGGATCGATCGCCAATCC | |||||

| CdZWF1b | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | F: GTTTCATTTGATCCTGAAGC | 491 | 0.86 | |

| R: GCCATTGATAAGTACCTGGAT | |||||

|

| |||||

| C. glabrata | CgFKS | 1,3-β-glucan synthase | F: GTCAAATGCCACAACAACAACCT | 589 | 1.27 |

| R: AGCACTTCAGCAGCGTCTTCAG | |||||

| CgLEU2 | 3-Isopropylmalate dehydrogenase | F: TTTCTTGTATCCTCCCATTGTTCA | 512 | 1 | |

| R: ATAGGTAAAGGTGGGTTGTGTTGC | |||||

| CgNMT1 | Myristoyl-coenzyme A, protein N-myristoyltransferase | F: GCCGGTGTGGTGTTGCCTGCTC | 607 | 0.81 | |

| R: CGTTACTGCGGTGCTCGGTGTCG | |||||

| CgTRP1 | Phosphoribosyl-anthranilate isomerase | F: AATTGTTCCAGCGTTTTTGT | 419 | 1.08 | |

| R: GACCAGTCCAGCTCTTTCAC | |||||

| CgUGP1 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | F: TTTCAACACCGACAAGGACACAGA | 616 | 0.75 | |

| R: TCGGACTTCACTAGCAGCAAATCA | |||||

| CgURA3 | Orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase | F: AGCGAATTGTTGAAGTTGGTTGA | 602 | 0.68 | |

| R: AATTCGGTTGTAAGATGATGTTGC | |||||

|

| |||||

| C. krusei | CkADE2 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase | F: GTCACTTCTCAGTTTGAAGC | 470 | 2.33 |

| R: ACACCATCTAAAGTAGAGCC | |||||

| CkHIS3 | Imidazole glycerol phosphate dehydratase | F: GGAGGGGACATATCACTGCC | 400 | 1.75 | |

| R: AATCTTTAATTGCCAAAGCC | |||||

| CkLEU2 | 3-Isopropylmalate dehydrogenase | F: CTGTGAGACCAGAACAGGGG | 619 | 1.89 | |

| R: GCAGAGCCACCCAAGTCTCC | |||||

| CkLYS2 | L-Aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | F: ATCTGAGAAGCAGTTGGCGC | 441 | 1.90 | |

| R: AGACTTGTAAGAATTATCCC | |||||

| CkNMT1 | Myristoyl-coenzyme A, protein N-myristoyltransferase | F: CTGATGAAGAAATCACCG | 537 | 2.00 | |

| R: GCTTGATATCATCTTTGTCC | |||||

| CkTRP1 | Phosphoribosyl-anthranilate isomerase | F: AGCTATGTCGAGCAAAGAGG | 380 | 2.00 | |

| R: ACATCAACGCCACAACACCC | |||||

|

| |||||

| C. tropicalis | CtICL1 | Isocitrate lyase | F: CAACAGATTGGTTGCCATCAGAGC | 447 | 0.71 |

| R: CGAAGTCATCAACAGCCAAAGCAG | |||||

| CtMDR1 | Multidrug resistance protein | F: TGTTGGCATTCACCCTTCCT | 425 | 1.67 | |

| R: TGGAGCACCAAACAATGGGA | |||||

| CtSAPT2 | Secreted aspartic protease 2 | F: CAACGATCGTGGTGCTG | 525 | 0.51 | |

| R: CACTGGTAGCTGAAGGAG | |||||

| CtSAPT4 | Secreted aspartic protease 4 | F: TGCTTCTCCTACAACTTCACCTCC | 390 | 0.90 | |

| R: ATTCCCATGACTCCCTGAGCAACA | |||||

| CtXYR1 | D-xylose reductase I or II | F: AGTTGGTTTCGGATGTTG | 370 | 3.00 | |

| R: TCGTAAATCAAAGCACCAGT | |||||

| CtZWF1 | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | F: GGTGCTTCAGGAGATTTAGC | 520 | 0.94 | |

| R: ACCTTCAGTACCAAAAGCTTC | |||||

F and R indicate forward and reverse primers, respectively. Genotypes/site indicate the ratio of genotypes to SNPs.

The MLST system for C. tropicalis comprises six housekeeping genes ([52], Table 2). Data indicate that C. tropicalis phylogenetically resembles C. albicans [53]. Both are diploid organisms, exhibit a predominant clonal mode of reproduction, and support high level of recombination events, which mimic sexual reproduction processes [53]. However, unlike C. albicans [35], C. tropicalis shows a clonal cluster enriched with isolates with fluconazole resistant or “trailing growth” phenotypes [54]. The term “trailing growth” describes the growth that some isolates exhibit at drug concentrations above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) after 48 h of incubation, although isolates appear fluconazole susceptible after 24 h of incubation. However, Wu et al. [55] reported that C. tropicalis isolates were unrelated to the fluconazole resistance pattern, suggesting that the antifungal resistance may develop geographically. Association between the MLST type of each isolate and flucytosine resistance has also been observed [40, 56, 57]. It is interesting that MLST genotypes were only distantly related, thus indicating that flucytosine resistant strains emerged independently in different geographic areas [56].

MLST gene sets for C. krusei and C. dubliniensis have also been described [50, 51]. Characteristics of the housekeeping loci used for these species are described in Table 2.

3. Microsatellite Length Polymorphisms Analysis

Microsatellite length polymorphisms (MLP) analysis identifies microsatellite instability. Microsatellites, also called simple sequence repeats (SSRs) or short tandem repeats (STRs), are tandem repeat nucleotides comprising 1–6 bp dispersed throughout the genome. These sequences undergo considerable length variations due to DNA polymerase slippage and as a consequence are highly mutagenic [58]. In Candida species, this technique has been applied for strain typing [43–45, 59–63], analysis of population structure [64, 65], and epidemiological studies [57, 61, 66–68]. For C. albicans, several polymorphic microsatellite loci have been identified (Table 3 and references therein). They were located in the promoter sequence of the elongation factor 3 (EF3) [60, 69], in coding regions of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase gene (ERK1) [70], downstream of coding sequences of cell division cycle protein (CDC3) [59, 60, 71] and imidazole glycerol phosphate dehydratase genes (HIS3) [60] and in noncoding regions (CARABEME, CAI, CAIII, CAV, CAVI, and CAVII) [44, 66, 72]. These markers were used alone or in combination. The best discriminatory powers (DPs) obtained were 0.998 for CAI, CAIII, and CAVI [44] and 0.999 for EF3, CAREBEME, CDC3, HIS3, KRE6, LOC4 (MRE11), ZNF1, CAI, CAIII, CAV, and CAVII [73]. The DP estimates the method ability to differentiate between two unrelated strains. A high DP value (close to 1) indicates that the typing method is able to distinguish each member of a strain population from all other members of that population [74]. It is noteworthy to mention that CA markers were specific for C. albicans [44, 66]. In fact, CA microsatellites were named after C. albicans and numbered according to the order of the analysis [44]. These markers are highly polymorphic since they are located outside known coding regions, thus being under inconsequential selective pressures. Recently, an allelic CDC3 ladder has been developed for interlaboratory comparison of C. albicans genotyping data [75]. This ladder proved to be important as an internal standard for a correct allele assignment.

Table 3.

Description of SSRs used for MLPs analysis of C. albicans.

| Locus | Ch | Gene product | Repeat motif | Location | DP | Primers | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EF3 | 5 | Elongation factor 3 | (TTC)n (TTTC)n | Upstream region | 0.88(1)

0.97(1+3+4) 0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: TTTCCTCTTCCTTTCATATAGAA R: GGATTCACTAGCAGCAGACA |

[59, 60, 64, 69, 73] |

| 2 | ERK1 | 4 | Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase | (CAGGCT)n(CAAGCT)n

- -(CAA)n- -(GCCGCA)n - -(CTT)n |

Coding region | nr | F: CGACCACGTCATCAATAGAAATCG R: CGTTGAATGAAACTTGACGAGGGG |

[64, 70] |

| 3 | CARE-BEME | 6 | nc | (GAA)n | Noncoding region | 0.999(ALL except 2+12) | F: GAATCATGAAACAGAAACTG R: TGGGTGAAGGATAATCTGCA |

[72, 73] |

| 4 | CDC3 | 1 | Cell division cycle protein | (AGTA)n | Downstream region | 0.97(1+3+4)

0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: CAGATGATTTTTTGTATGAGAAGAA R: CAGTCACAAGATTAAAATGTTCAAG |

[60, 73] |

| 5 | HIS3 | 2 | Imidazole glycerol phosphate dehydratase | (ATTT)n | Downstream region | 0.97(1+3+4)

0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: TGGCAAAAATGATATTCCAA R: TACACTATGCCCCAAACACA |

[60, 73] |

| 6 | KRE6 | 3 | β-1,6-Glucan synthesis | (AAT)n | Coding region | 0.999(ALL except 2+12) | F: CAAGCTTATAGTGGCTACTA R: CCAACACTGATACATCTCG |

[64, 73] |

| 7 |

LOC4

(MRE11) |

7 | Double-strand break repair protein | (GAA)n | Coding region | 0.999(ALL except 2+12) | F: GTAATGATTACGGCAATGAC R: AGAACGACGTGTACTATTGG |

[64, 73] |

| 8 | ZNF1 | 4 | Zinc finger transcription factor | (CAA)n | Coding region | 0.999(ALL except 2+12) | F: CCATTACAGCTGAACCAGCGAGGG R: CGCTAGGTAACCTACAGATTGTGGC |

[64, 73] |

| 9 | CAI | 4 | nc | (CAA)n- -(CAA)n | Noncoding region | 0.967(9)

0.998(9+10+12) 0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: ATGCCATTGAGTGGAATTGG R: AGTGGCTTGTGTTGGGTTTT |

[44, 66, 73] |

| 10 | CAIII | 5 | nc | (GAA)n | Noncoding region | 0.853(10)

0.998(9+10+12) 0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: TTGGAATCACTTCACCAGGA R: TTTCCGTGGCATCAGTATCA |

[44, 73] |

| 11 | CAV | 3 | nc | (ATT)n | Noncoding region | 0.853(11)

0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: TGCCAAATCTTGAGATACAAGTG R: CTTGCTTCTCTTGCTTTAAATTG |

[44, 73] |

| 12 | CAVI | 2 | nc | (TAAA)n | Noncoding region | 0.853(12)

0.998(9+10+12) |

F: ACAATTAAAGAAATGGATTTTAGTCAG R: TGCTGGTGCTGCTGGTATTA |

[44] |

| 13 | CAVII | 1 | nc | (CAAAT)n | Noncoding region | 0.670(13)

0.999(ALL except 2+12) |

F: GGGGATAGAAATGGCATCAA R: TGTGAAACAATTCTCTCCTTGC |

[44, 73] |

Discriminatory power (DP) based on one or various loci is indicated in brackets according to the row number. Dashed line indicates various nucleotides that separate different microsatellites in the sequence. Ch: chromosome; nc: not corresponding; nr: not reported.

Genotyping systems based on SSR markers have been also described for C. glabrata. In 2005, Foulet et al. [67] adopted three polymorphic microsatellite markers located upstream of the mitochondrial RNase P precursor (RPM2), metallothionein 1 (MTI), and δ5,6-sterol desaturase (ERG3) genes to generate a rapid strain typing method with a DP of 0.84. These markers were specific for C. glabrata isolates. Addition of three new microsatellite markers (GLM4, GLM5, and GLM6) generated a typing system with a DP value of 0.941 [76]. However, by combining only 4 microsatellite markers (MTI, ERG3, GLM4, and GLM5), authors achieved a DP value of 0.949. A different set of six different microsatellite markers located in noncoding regions (Cg4, Cg5, and Cg6) and in coding regions (Cg7, Cg10, and Cg11) have been described [68], although the highest DP value, 0.902, was reached by using a combination of only four markers (Cg4, Cg5, Cg6, and Cg10). Another research group adopted eight polymorphic microsatellite markers distributed among different chromosomes [77]. This method has a DP value of 0.97, making it suitable for tracing strains. Studies using this system indicate that C. glabrata is a persistent colonizer of the human tract, where it appears to undergo microevolution [78].

A highly polymorphic CKTNR locus for molecular strain typing of C. krusei has been identified [43]. Such locus consists of CAA repeats interspersed with CAG and CAT trinucleotides. Analysis of the CKTNR allele distribution suggested that the reproductive mode of C. krusei is mainly clonal [43].

MLP analysis also proved to be a reproducible method for molecular genotyping of C. parapsilosis [79]. Seven polymorphic loci containing dinucleotide repeats, most of them located in noncoding regions, were analyzed. The DP calculated for such loci was 0.971. These microsatellites were not amplified with DNA from single representatives of related species, Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis [79]. Recently, another research group conducted C. parapsilosis typing studies using one of the previously reported marker (locus B, [79]) and three additional new microsatellite loci located outside known coding regions [80]. This multilocus analysis resulted in a DP of 0.99. These markers were also specific for the molecular typing of C. parapsilosis since no amplification products were obtained with DNA of C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis.

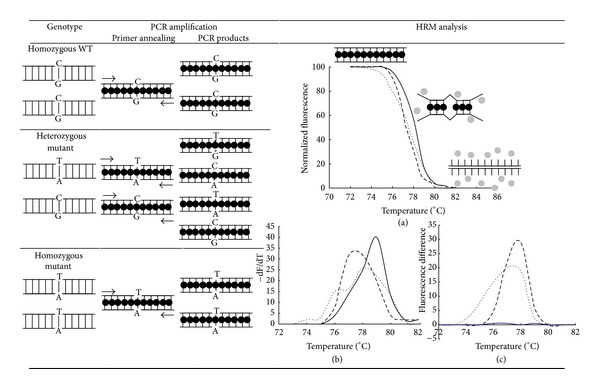

4. High-Resolution DNA Melting

High-resolution DNA melting (HRM) is a novel technique for SNPs genotyping and for the identification of new genetic variants in real time (Figure 1). First, a PCR method is used to amplify specific DNA polymorphic regions in the presence of saturating DNA fluorophores [81]. The dye does not interact with single-stranded DNA but binds to double-stranded DNA, resulting in a bright structure. After PCR amplification, at the beginning of the HRM analysis, the fluorescence is high. As DNA samples are heated up, the double-stranded DNA dissociates releasing the dye which leads to a decrease in the fluorescence intensity (Figure 1(a)). The observed melting temperature (T m) and the shape of the melt curve are characteristics of the specific sequence of the fragment (primarily the GC content and the length). Data can also easily be interpreted by derivative melting curves (Figure 1(b)) and by plotting the fluorescence difference between a sample and a selected control at each temperature (Figure 1(c)) [81]. Some recent studies used HRM to differentiate clinical Candida species [82–84]. HRM has been proven to be a sensitive, reproducible, and inexpensive tool for a clinical laboratory but exhibits low DP values. DP for CDC3, EF3, and HIS3 markers was 0.77 [84]. However, HRM can be used along other genotyping methods to increase the resolving power. In fact, the combination of HRM with MLP and SNaPshot minisequencing of the CDC3 locus provided a DP value of 0.88 [83].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of HRM analysis for SNPs genotyping. Arrows indicate the positions of the primers for allele amplification of a region harboring a SNP. The DNA fluorophore has a bright fluorescence when intercalated to double-stranded DNA (black circle) and low fluorescence in the unbound state (gray circles). Mispaired nucleotides are shown as diagonally broken lines. PCR products from homozygous wild type (solid lines), heterozygous mutant (dotted lines), and homozygous mutant (dashed lines) were analyzed by normalized melting curves (a), derivate melting curves (b), and difference plots (c).

5. Conclusions

The development of DNA sequence-based technologies led to a great progress in understanding the epidemiology of clinical isolates of Candida species. Both MLST and MLP analysis offer a number of technical advantages over conventional typing methods including extremely high DP values and reproducibility, ease of use, and rapid reliable data. The selection of the technique depends on the purpose of the study, the accessibility of genotypic strains archives, the time available to complete the analysis, and the cost. MLST remains the most reliable method for the assessment of population structure, diversity, and dynamics among C. albicans, whereas MLP analysis is most suitable for a rapid and less expensive study of a limited number of isolates.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by grants from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT) to Claudia Spampinato (PICT 0458) and Darío Leonardi (PICT 2643), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) to Claudia Spampinato (PIP 0018), and Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR) to Claudia Spampinato (BIO 221) and Darío Leonardi (BIO 328). Both authors are members of the researcher career of CONICET.

References

- 1.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2007;20(1):133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Sudbery P. Candida albicans, a major human fungal pathogen. Journal of Microbiology. 2011;49(2):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta SK, Stevens DA, Mishra SK, Feroze F, Pierson DL. Distribution of Candida albicans genotypes among family members. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 1999;34(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghannoum MA, Jurevic RJ, Mukherjee PK, et al. Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713.e1000713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hull CM, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. Evidence for mating of the ‘asexual’ yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science. 2000;289(5477):307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coste A, Selmecki A, Forche A, et al. Genotypic evolution of azole resistance mechanisms in sequential Candida albicans isolates. Eukaryotic Cell. 2007;6(10):1889–1904. doi: 10.1128/EC.00151-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coste AT, Karababa M, Ischer F, Bille J, Sanglard D. TAC1, transcriptional activator of CDR genes, is a new transcription factor involved in the regulation of Candida albicansABC transporters CDR1 and CDR2 . Eukaryotic Cell. 2004;3(6):1639–1652. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.6.1639-1652.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coste A, Turner V, Ischer F, et al. A mutation in Tac1p, a transcription factor regulating CDR1 and CDR2, is coupled with loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 5 to mediate antifungal resistance in Candida albicans . Genetics. 2006;172(4):2139–2156. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bougnoux M-E, Diogo D, François N, et al. Multilocus sequence typing reveals intrafamilial transmission and microevolutions of Candida albicans isolates from the human digestive tract. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(5):1810–1820. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1810-1820.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odds FC, Davidson AD, Jacobsen MD, et al. Candida albicans strain maintenance, replacement, and microvariation demonstrated by multilocus sequence typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(10):3647–3658. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00934-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forche A, May G, Magee PT. Demonstration of loss of heterozygosity by single-nucleotide polymorphism microarray analysis and alterations in strain morphology in Candida albicans strains during infection. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;4(1):156–165. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.1.156-165.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forche A, Magee PT, Selmecki A, Berman J, May G. Evolution in Candida albicans populations during a single passage through a mouse host. Genetics. 2009;182(3):799–811. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forche A, Abbey D, Pisithkul T, et al. Stress alters rates and types of loss of heterozygosity in Candida albicans . MBio. 2011;2(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00129-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tortorano AM, Kibbler C, Peman J, Bernhardt H, Klingspor L, Grillot R. Candidaemia in Europe: epidemiology and resistance. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2006;27(5):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow JK, Golan Y, Ruthazer R, et al. Factors associated with candidemia caused by non-albicans Candida species versus Candida albicans in the intensive care unit. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46(8):1206–1213. doi: 10.1086/529435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobel JD. The emergence of non-albicans Candida species as causes of invasive candidiasis and candidemia. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2006;8(6):427–433. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan TY, Tan AL, Tee NWS, Ng LSY, Chee CWJ. The increased role of non-albicans species in candidaemia: results from a 3-year surveillance study. Mycoses. 2010;53(6):515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Dwivedi P, Ioannidou E, Shaqman M, Hull D, Burleson J. Oral Candida infection and colonization in solid organ transplant recipients. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 2009;24(3):249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horn DL, Neofytos D, Anaissie EJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 2019 patients: data from the prospective antifungal therapy alliance registry. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(12):1695–1703. doi: 10.1086/599039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almirante B, Rodríguez D, Cuenca-Estrella M, et al. Epidemiology, risk factors, and prognosis of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections: case-control population-based surveillance study of patients in Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(5):1681–1685. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1681-1685.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaller MA, Pappas PG, Wingard JR. Invasive fungal pathogens: current epidemiological trends. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(1):S3–S14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Steele-Moore L, et al. Twelve years of fluconazole in clinical practice: global-trends in species distribution and fluconazole susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2004;10(1):11–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.t01-1-00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Jones RN, et al. International surveillance of bloodstream infections due to Candida species: frequency of occurrence and in vitro susceptibilities to fluconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole of isolates collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39(9):3254–3259. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3254-3259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodgson AR, Dodgson KJ, Pujol C, Pfaller MA, Soll DR. Clade-specific flucytosine resistance is due to a single nucleotide change in the FUR1 gene of Candida albicans . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48(6):2223–2227. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2223-2227.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saghrouni F, Abdeljelil JB, Boukadida J, Said MB. Molecular methods for strain typing of Candida albicans: a review. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 114(6):1559–1574. doi: 10.1111/jam.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soll DR. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13(2):332–370. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.332-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H, et al. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(19):7329–7334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401648101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun BR, van het Hoog M, d’Enfert C, et al. A human-curated annotation of the Candida albicans genome. PLoS Genetics. 2005;1(1):0036–0057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van het Hoog M, Rast TJ, Martchenko M, et al. Assembly of the Candida albicans genome into sixteen supercontigs aligned on the eight chromosomes. Genome Biology. 2007;8(4, article R52):1–11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odds FC, Jacobsen MD. Multilocus sequence typing of pathogenic Candida species. Eukaryotic Cell. 2008;7(7):1075–1084. doi: 10.1128/EC.00062-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bougnoux M-E, Morand S, D’Enfert C. Usefulness of multilocus sequence typing for characterization of clinical isolates of Candida albicans . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40(4):1290–1297. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1290-1297.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavanti A, Gow NAR, Senesi S, Maiden MCJ, Odds FC. Optimization and validation of multilocus sequence typing for Candida albicans . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(8):3765–3776. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3765-3776.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bougnoux M-E, Tavanti A, Bouchier C, et al. Collaborative consensus for optimized multilocus sequence typing of Candida albicans . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(11):5265–5266. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5265-5266.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnaud MB, Costanzo MC, Skrzypek MS, et al. Sequence resources at the Candida genome database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35(1):D452–D456. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen K-W, Chen Y-C, Lo H-J, et al. Multilocus sequence typing for analyses of clonality of Candida albicans strains in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(6):2172–2178. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00320-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Da Matta DA, Melo AS, Colombo AL, Frade JP, Nucci M, Lott TJ. Candidemia surveillance in Brazil: evidence for a geographical boundary defining an area exhibiting an abatement of infections by Candida albicans group 2 strains. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(9):3062–3067. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00262-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odds FC. Molecular phylogenetics and epidemiology of Candida albicans . Future Microbiology. 2010;5(1):67–79. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bougnoux M-E, Pujol C, Diogo D, Bouchier C, Soll DR, d’Enfert C. Mating is rare within as well as between clades of the human pathogen Candida albicans . Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2008;45(3):221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odds FC, Bougnoux M-E, Shaw DJ, et al. Molecular phylogenetics of Candida albicans . Eukaryotic Cell. 2007;6(6):1041–1052. doi: 10.1128/EC.00041-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tavanti A, Davidson AD, Fordyce MJ, Gow NAR, Maiden MCJ, Odds FC. Population structure and properties of Candida albicans, as determined by multilocus sequence typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(11):5601–5613. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5601-5613.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lott TJ, Scarborough RT. Development of a MLST-biased SNP microarray for Candida albicans . Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2008;45(6):803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodgson AR, Pujol C, Denning DW, Soll DR, Fox AJ. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida glabrata reveals geographically enriched clades. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(12):5709–5717. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5709-5717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shemer R, Weissman Z, Hashman N, Kornitzer D. A highly polymorphic degenerate microsatellite for molecular strain typing of Candida krusei . Microbiology. 2001;147(8):2021–2028. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sampaio P, Gusmão L, Correia A, et al. New microsatellite multiplex PCR for Candida albicans strain typing reveals microevolutionary changes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(8):3869–3876. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3869-3876.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa J-M, Eloy O, Botterel F, Janbon G, Bretagne S. Use of microsatellite markers and gene dosage to quantify gene copy numbers in Candida albicans . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(3):1387–1389. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1387-1389.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lott TJ, Frade JP, Lockhart SR. Multilocus sequence type analysis reveals both clonality and recombination in populations of Candida glabrata bloodstream isolates from U.S. surveillance studies. Eukaryotic Cell. 2010;9(4):619–625. doi: 10.1128/EC.00002-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lott TJ, Frade JP, Lyon GM, Iqbal N, Lockhart SR. Bloodstream and non-invasive isolates of Candida glabrata have similar population structures and fluconazole susceptibilities. Medical Mycology. 2012;50(2):136–142. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.592153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mann PA, McNicholas PM, Chau AS, et al. Impact of antifungal prophylaxis on colonization and azole susceptibility of Candida species. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2009;53(12):5026–5034. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zimbeck AJ, Iqbal N, Ahlquist AM, et al. FKS mutations and elevated echinocandin MIC values among Candida glabrata isolates from U.S. population-based surveillance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54(12):5042–5047. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00836-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McManus BA, Coleman DC, Moran G, et al. Multilocus sequence typing reveals that the population structure of Candida dubliniensis is significantly less divergent than that of Candida albicans . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2008;46(2):652–664. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01574-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobsen MD, Gow NAR, Maiden MCJ, Shaw DJ, Odds FC. Strain typing and determination of population structure of Candida krusei by multilocus sequence typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45(2):317–323. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01549-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tavanti A, Davidson AD, Johnson EM, et al. Multilocus sequence typing for differentiation of strains of Candida tropicalis . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(11):5593–5600. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5593-5600.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobsen MD, Davidson AD, Li S-Y, Shaw DJ, Gow NAR, Odds FC. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Candida tropicalis isolates by multi-locus sequence typing. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2008;45(6):1040–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chou H-H, Lo H-J, Chen K-W, Liao M-H, Li S-Y. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida tropicalis shows clonal cluster enriched in isolates with resistance or trailing growth of fluconazole. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2007;58(4):427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu Y, Zhou H, Wang J, et al. Analysis of the clonality of Candida tropicalis strains from a general hospital in Beijing using multilocus sequence typing. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047767.e47767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen K-W, Chen Y-C, Lin Y-H, Chou H-H, Li S-Y. The molecular epidemiology of serial Candida tropicalis isolates from ICU patients as revealed by multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2009;9(5):912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desnos-Ollivier M, Bretagne S, Bernède C, et al. Clonal population of flucytosine-resistant Candida tropicalis from blood cultures, Paris, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008;14(4):557–565. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.071083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliveira EJ, Pádua JG, Zucchi MI, Vencovsky R, Vieira MLC. Origin, evolution and genome distribution of microsatellites. Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2006;29(2):294–307. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dalle F, Franco N, Lopez J, et al. Comparative genotyping of Candida albicans bloodstream and nonbloodstream isolates at a polymorphic microsatellite locus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38(12):4554–4559. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.12.4554-4559.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Botterel F, Desterke C, Costa C, Bretagne S. Analysis of microsatellite markers of Candida albicans used for rapid typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39(11):4076–4081. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4076-4081.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eloy O, Marque S, Botterel F, et al. Uniform distribution of three Candida albicans microsatellite markers in two French ICU populations supports a lack of nosocomial cross-contamination. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6, article no. 162 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garcia-Hermoso D, Cabaret O, Lecellier G, et al. Comparison of microsatellite length polymorphism and multilocus sequence typing for DNA-based typing of Candida albicans . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45(12):3958–3963. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01261-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stéphan F, Sialou Bah M, Desterke C, et al. Molecular diversity and routes of colonization of Candida albicans in a surgical intensive care unit, as studied using microsatellite markers. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35(12):1477–1483. doi: 10.1086/344648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fundyga RE, Lott TJ, Arnold J. Population structure of Candida albicans, a member of the human flora, as determined by microsatellite loci. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2002;2(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1348(02)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lott TJ, Fundyga RE, Brandt ME, et al. Stability of allelic frequencies and distributions of Candida albicans microsatellite loci from U.S. population-based surveillance isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(3):1316–1321. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1316-1321.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sampaio P, Gusmão L, Alves C, Pina-Vaz C, Amorim A, Pais C. Highly polymorphic microsatellite for identification of Candida albicans strains. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(2):552–557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.552-557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Foulet F, Nicolas N, Eloy O, et al. Microsatellite marker analysis as a typing system for Candida glabrata . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(9):4574–4579. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4574-4579.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grenouillet F, Millon L, Bart J-M, et al. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis for rapid typing of Candida glabrata . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45(11):3781–3784. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01603-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bretagne S, Costa J-M, Besmond C, Carsique R, Calderone R. Microsatellite polymorphism in the promoter sequence of the elongation factor 3 gene of Candida albicans as the basis for a typing system. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1997;35(7):1777–1780. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1777-1780.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Metzgar D, Field D, Haubrich R, Wills C. Sequence analysis of a compound coding-region microsatellite in Candida albicans resolves homoplasies and provides a high-resolution tool for genotyping. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 1998;20(2):103–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dalle F, Dumont L, Franco N, et al. Genotyping of Candida albicans oral strains from healthy individuals by polymorphic microsatellite locus analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(5):2203–2205. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.2203-2205.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lunel FV, Licciardello L, Stefani S, et al. Lack of consistent short sequence repeat polymorphisms in genetically homologous colonizing and invasive Candida albicans strains. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180(15):3771–3778. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3771-3778.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.'ollivier CL, Labruère C, Jebrane A, et al. Using a Multi-Locus Microsatellite Typing method improved phylogenetic distribution of Candida albicans isolates but failed to demonstrate association of some genotype with the commensal or clinical origin of the isolates. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2012;12:1949–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunter PR. Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1990;28(9):1903–1905. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1903-1905.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garcia-Hermoso D, MacCallum DM, Lott TJ, et al. Multicenter collaborative study for standardization of Candida albicans genotyping using a polymorphic microsatellite marker. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(7):2578–2581. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00040-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abbes S, Sellami H, Sellami A, et al. Candida glabrata strain relatedness by new microsatellite markers. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2012;31:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brisse S, Pannier C, Angoulvant A, et al. Uneven distribution of mating types among genotypes of Candida glabrata isolates from clinical samples. Eukaryotic Cell. 2009;8(3):287–295. doi: 10.1128/EC.00215-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Enache-Angoulvant A, Bourget M, Brisse S, et al. Multilocus microsatellite markers for molecular typing of Candida glabrata: application to analysis of genetic relationships between bloodstream and digestive system isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(11):4028–4034. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02140-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lasker BA, Butler G, Lott TJ. Molecular genotyping of Candida parapsilosis group I clinical isolates by analysis of polymorphic microsatellite markers. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(3):750–759. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.750-759.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sabino R, Sampaio P, Rosado L, Stevens DA, Clemons KV, Pais C. New polymorphic microsatellite markers able to distinguish among Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(5):1677–1682. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02151-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Erali M, Voelkerding KV, Wittwer CT. High resolution melting applications for clinical laboratory medicine. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2008;85(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arancia S, Sandini S, De Bernardis F, Fortini D. Rapid, simple, and low-cost identification of Candida species using high-resolution melting analysis. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2011;69(3):283–285. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Costa J-M, Garcia-Hermoso D, Olivi M, et al. Genotyping of Candida albicans using length fragment and high-resolution melting analyses together with minisequencing of a polymorphic microsatellite locus. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2010;80:306–309. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gago S, Lorenzo B, Gomez-Lopez A, Cuesta I, Cuenca-Estrella M, Buitrago MJ. Analysis of strain relatedness using High Resolution Melting in a case of recurrent candiduria. BMC Microbiology. 2013;13, article 13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]