Short abstract

The lymphatic system plays important roles in protein and solute transport as well as in the immune system. Its functionality is vital to proper homeostasis and fluid balance. Lymph may be propelled by intrinsic (active) vessel pumping or passive compression from external tissue movement. With regard to the former, nitric oxide (NO) is known to play an important role modulating lymphatic vessel contraction and vasodilation. Lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) are sensitive to shear, and increases in flow have been shown to cause enhanced production of NO by LECs. Additionally, high concentrations of NO have been experimentally observed in the sinus region of mesenteric lymphatic vessels. A computational flow and mass transfer model using physiologic geometries obtained from confocal images of a rat mesenteric lymphatic vessel was developed to determine the characteristics of NO transport in the lymphatic flow regime. Both steady and unsteady analyses were performed. Production of NO was shear-dependent; basal cases using constant production were also generated. Simulations revealed areas of flow stagnation adjacent to the valve leaflets, suggesting the high concentrations observed here experimentally are due to minimal convection in this region. LEC sensitivity to shear was found to alter the concentration of NO in the vessel, and the convective forces were found to profoundly affect the concentration of NO at a Péclet value greater than approximately 61. The quasisteady analysis was able to resolve wall shear stress within 0.15% of the unsteady case. However, the percent difference between unsteady and quasisteady conditions was higher for NO concentration (6.7%). We have shown high NO concentrations adjacent to the valve leaflets are most likely due to flow-mediated processes rather than differential production by shear-sensitive LECs. Additionally, this model supports experimental findings of shear-dependent production, since removing shear dependence resulted in concentrations that are physiologically counterintuitive. Understanding the transport mechanisms and flow regimes in the lymphatic vasculature could help in the development of therapeutics to treat lymphatic disorders.

Keywords: nitric oxide, computational fluid dynamics, mass transport, lymphatic

Introduction

The lymphatic system is an expansive vascular network that plays a vital role in fluid homeostasis and physiologic function within the body. It is responsible for the transport of fluid from the interstitial spaces to the venous return. Its dysfunction could result in a number of pathologies, including lymphedema, or swelling within the interstitial spaces. Additionally, it is important for proper immune system functionality and macromolecular balances [1].

Terminal lymphatics composed primarily of endothelial cells passively take up fluid, cells, debris, and solutes from the interstitial spaces. Eventually, this initial network of vessels gives rise to the collecting lymphatics, which are generally tubular vessels segmented by bileaflet check valves encapsulated by a bulbous sinus region. Lymph (largely aqueous with relatively low concentrations of proteins and cells compared to blood) is propelled through the collecting lymphatics via two primary modes: intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. The former, also known as active pumping, is the result of lymphatic muscle cell contraction, while the latter involves external compression mechanisms, such as the movement of skeletal muscle or other tissues surrounding the lymphatics [1].

Nitric oxide (NO), a known vasodilator, has been shown to influence lymphatic pumping. Enhanced wall shear stress (WSS) has been shown to activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase in lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) to produce NO during in situ lymphatic vessel experiments [2]. Bohlen et al. [2,3] found an approximately 2–4-fold higher concentration of NO in the bulbous surface of the valve region of the lymphatics compared to that of the tubular portion. The mechanisms behind this difference in concentration are not clear. The answer to this question may lie in the nature of flow patterns in lymphatic vessels and/or the shear sensitivity of LECs.

While there are no studies that have attempted to model transport within the lymphatic system, several computational works have been conducted that model NO transport within a parallel plate flow chamber or a simplified model of the microcirculation [4–6]. Despite the 2D nature of these models, they provided valuable insight with regard to theoretical framework (e.g., constant parameter and nondimensionalization) that aided in the development of the model presented herein. Other models developed for the lymphatic system are simply lumped-parameter [7,8], one-dimensional [7,8], or do not properly take into account the geometry of the valve region [9].

The main aim of this study was to characterize the distribution of NO within a physiologic model of a lymphatic vessel obtained from confocal images in response to various convective flow regimes and degrees of LEC sensitivity to shear. In particular, we wanted to identify the importance of the convective transport of NO within the lymphatic vasculature and determine if the high concentrations in the sinus region observed in an experimental setting may be attributed to flow-mediated factors, higher LEC numbers, or some combination. While there have been experimental studies that have quantified NO concentration within the lymphatics [2,3], to our knowledge, this is the first study that has attempted to computationally model the transport of NO within a 3D model of a lymphatic vessel.

Methods

Vessel Geometry.

Pentobarbital (50 mg ml−1, 50 mg kg−1, intramuscularly (IM)) was used to anesthetize male Sprague–Dawley rats (280–380 g), and a midline laparotomy incision was made to expose the mesenteric lymphatic bed. Appropriate sections of the mesenteric lymphatic were carefully isolated, and all living cells were fluorescently loaded by intraluminally loading the vessel with CellTracker Green CMFDA (25 μM, MolecularProbes). After cannulation, the vessel was placed in a CH2 Microvessel Chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation) in Ca2+-free physiologic saline solution to prevent contractions. The inlet and outlet of the isolated vessel were attached to pipettes leading to separate reservoirs of albumin-containing physiological saline solution (APSS), where an axial pressure difference of −5 cmH2O (P out − P in) at an average pressure of 3.5 cmH2O was enforced to ensure an open valve configuration. Stacks of image slices approximately 2.5 μm apart for the full depth of the vessel were obtained via confocal microscopy (Nikon, Eclipse TE2000-E).

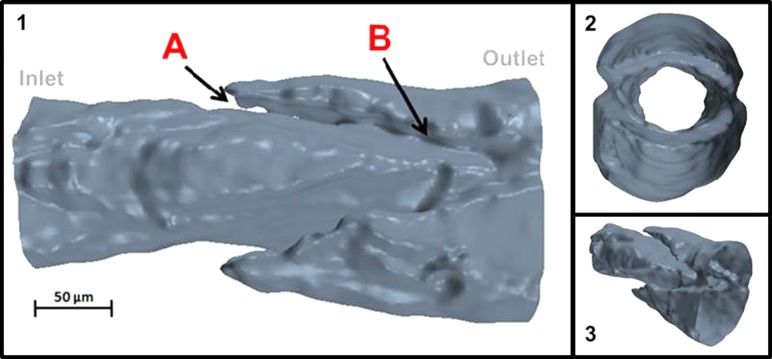

The stacks of confocal images were imported into Scan IP/FE (Simpleware, Exeter, UK) and were smoothed, filtered, and reconstructed into a 3D surface mesh of the vessel fluid region (Fig. 1). Because of this, the actual leaflets (which are part of the solid vessel wall) are not visible in this reconstruction but rather show up as “gaps” in the fluid region. In particular, recursive Gaussian and salt-and-pepper filters were used to smooth the images and reduce noise. The surface mesh was then saved in *.stl format for later computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis.

Fig. 1.

Geometry of the fluid region of the rat mesenteric lymphatic vessel. Panel 1: Side view of the lymphatic fluid region with arrows indicating (A) valve leaflet insertion point and (B) trailing edge of the valve leaflets. The valve leaflets are represented by gaps on either side of the vessel, because the fluid (not solid) region was reconstructed for simulations. Panel 2: Down-the-barrel view of lymphatic geometry. Panel 3: Skewed view of the lymphatic geometry. Note that 200-μm extensions (extensions not shown in illustration) were added at both the inlet and outlet of the vessel to accommodate flow simulations.

Employing the analogy between mass and energy transfer, the dimensionless temperature values were used to model the concentration of NO in the vessel. The computational grid was divided into control volumes, and the Navier–Stokes and conservation of energy equations were solved for each cell. To ensure accuracy in our analysis, the Lewis relation [10] was employed and α/Dij was specified as unity, where α is thermal diffusivity and Dij is the diffusion coefficient of NO in aqueous solution [11]. Thus, the energy solutions had the same shape as that of the mass transfer. Table 1 shows the values for the concentration parameters. The equivalent thermal parameters are k = 0.0138 W m−1 K−1, Cp = 4181.72 J kg−1 K−1, and kT = 1.38 W m3 K−1, representing the thermal conductivity, specific heat, and energy consumption rate, respectively. All concentration parameters were matched from the literature [5,11,12] and correspond to NO in aqueous solution.

Table 1.

Description of constant parameters used in the simulations

| Concentration parameters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Value, units | Description |

| Dij | 3.3 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient of NO in water |

| k NO | 7.56 × 10−6 nM−1 s−1 | Pseudosecond-order auto-oxidative NO reaction rate |

| R NO,Max | 0.0033 μM cm s−1 | Maximum production rate of NO |

| ρ | 1000 kg m−3 | Density of lymph |

| R | 50 μm | Representative radius |

Flow and Concentration Equations.

Both steady and time-dependent simulations were performed using the commercially available software Star-CCM+ (CD-adapco, Melville, NY). The software employs the finite volume approach that uses second order discretization to solve for flow and energy on the computational grid.

Lymph was assumed to be a Newtonian and incompressible fluid with a dynamic viscosity, μ, of 0.9 cP and density, ρ, of 1 g cm−3. Transport of NO is governed by the advection-diffusion-reaction equation

| (1) |

where is the velocity field, C NO is the concentration of NO, t is time, and k NO is the pseudosecond-order auto-oxidative NO reaction rate [12]. It should be noted that, because the concentration of NO within the lymphatic vasculature [2,3] is approximately two orders of magnitude lower than that of oxygen [13], the use of a pseudosecond-order reaction rate was employed rather than a third-order term [12]. A sigmoidal relationship between NO production and axial WSS was used as the flux boundary condition [14] for NO production at the wall of the vessel (Eq. 2),

| (2) |

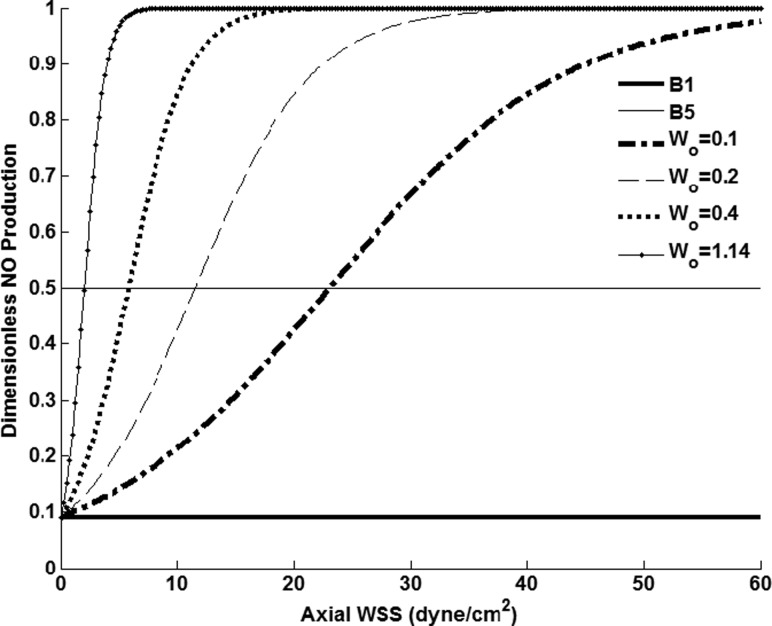

where R NO is the production rate of NO, R NO, Max is the maximum production rate of NO corresponding to the rate used by Plata et al. [5] when modeling arterial endothelial cell production, WSSaxial is axial WSS, a is the local radius of the vessel, θ is the azimuthal angle, and γ and Wo [14] characterize LEC sensitivity to shear. This function represents an increase in NO production in response to WSS, but at a certain value of axial WSS (termed the “saturation point”), the LECs can no longer produce at a higher rate with further elevation in shear (Fig. 2). Furthermore, an increase or decrease in the parameter Wo results in this saturation point occurring at a higher or lower value of axial WSS.

Fig. 2.

Range of NO production values with constant γ = 10. For shear-dependent cases, Wo was varied from 0.1 to 1.14, corresponding to increasing levels of LEC shear-sensitivity. Basal level productions B1 and B5 correspond to dimensionless production values of 0.09 and 0.5, respectively.

In this study, Wo was varied to determine the effect of different saturation points on the concentration of NO within the lumen of the vessel. It should be noted that the maximum production was assumed to be 11 times that of the basal level (e.g., γ = 10). This value was chosen based on previous work conducted by others when modeling arterial endothelial cell NO transport [5], due to lack of experimental data of NO production by LECs. Furthermore, γ is not expected to have an effect on the spatial patterns of NO concentration, but it may affect the absolute levels to some degree [5]. Simulations were also run using constant NO production boundary conditions with dimensionless values of 0.09 and 0.5, corresponding to the parameters B1 and B5, respectively.

Variables were converted to dimensionless form in the following manner:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where Vo is the average value of the parabolic inlet velocity, R is the representative radius at the inlet of the lymphatic vessel, and to is the characteristic time equivalent to 3.0 s, the time scale indicative of the duration of a typical contractile cycle for these vessels. Inserting Eqs. (3)–(8) into Eq. (1) results in the following governing dimensionless equation:

| (9) |

where Pe is the Péclet number equivalent to 2RVo/Dij.

Model Geometry and Computational Inputs.

Two-hundred-micrometer-long inlet and outlet extensions were added to the geometry to facilitate the application of boundary conditions. Extruding the inlet and outlet did not have a significant effect on concentration values during positive flow conditions (less than 1%), because these extended areas were outside the “domain of influence.” For example, when a zero-flux at the wall was applied at the extruded inlet region, it did not affect downstream concentration values within the physiologic portion of the vessel because additional NO was not added to the domain via flux. Additionally, the extruded outlet (during positive flow conditions) did not have any influence on upstream concentration within the physiologic portion of the vessel. However, during unsteady simulations, where negative velocities occurred and the domain of influence was reversed, lingering amounts of NO in the extruded portions influenced concentration values within the physiologic region and should thus be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Additionally, the selected inlet length allowed for the development of a 3D parabolic velocity profile.

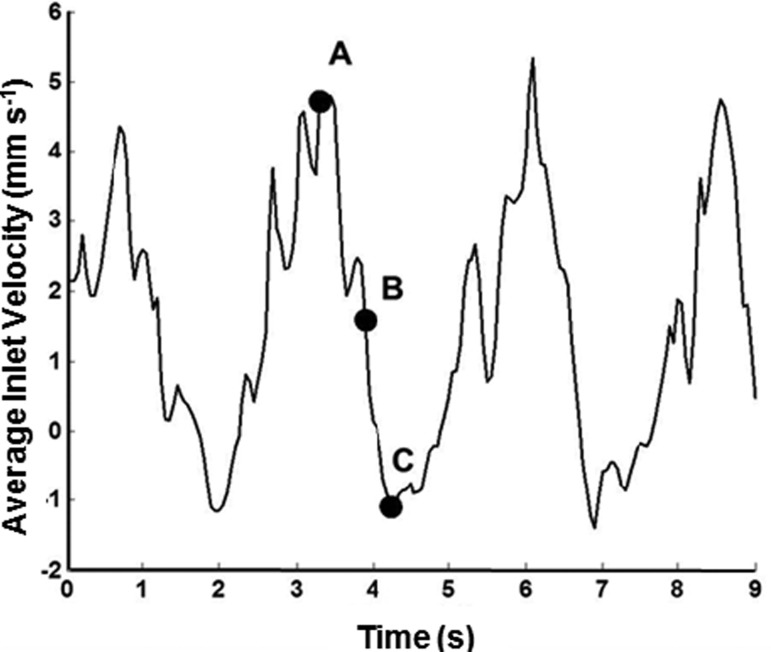

A parabolic velocity profile was implemented at the inlet with average velocities ranging from 0.5–7.0 mm s−1, which are in the physiologic range of velocities observed during in situ experiments [15] (Table 2). Note the Reynolds number, Re, is defined as ρVo2R/μ. To determine the validity of a quasisteady analysis, an unsteady case was simulated using an experimentally obtained velocity profile [15] (Fig. 3). Instantaneous WSS and NO values taken at different time points were compared to steady simulation results performed at the same average inlet velocity values.

Table 2.

Range of velocities and dimensionless numbers used for steady simulations

| Vo (mm s−1) | Pe | Re |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 15 | 0.06 |

| 1.0 | 30 | 0.11 |

| 2.0 | 61 | 0.22 |

| 3.0 | 91 | 0.33 |

| 4.0 | 121 | 0.44 |

| 5.0 | 152 | 0.56 |

| 6.0 | 182 | 0.67 |

| 7.0 | 212 | 0.78 |

Note that Re is less than one for all cases, suggesting the important role of viscous forces in the lymphatic flow regime.

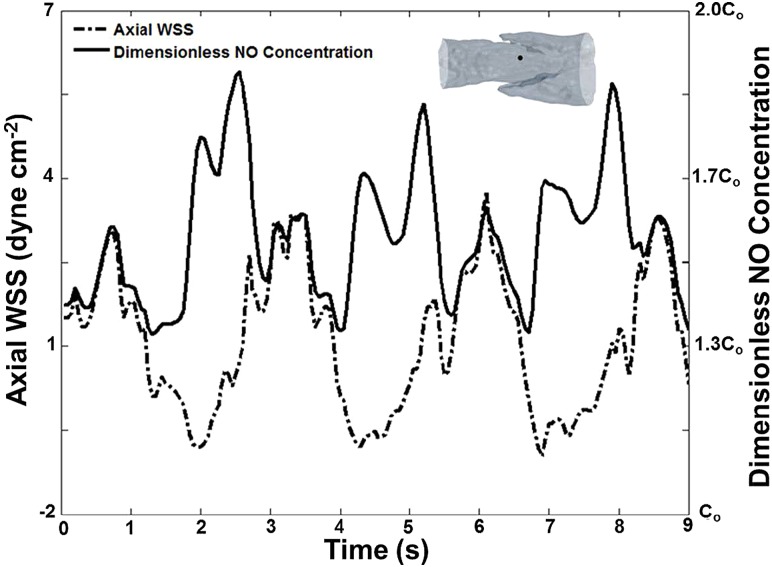

Fig. 3.

Transient velocity from a rat mesenteric lymphatic vessel used for time-dependent simulations. The raw waveform taken from the literature [15] was interpolated using a 0.05-s time step, resulting in a velocity profile consisting of values obtained through a sampling frequency of 180 points for 9.0 s. A, B, and C are locations along the velocity where instantaneous WSS and NO values were extracted. These points correspond to the maximal, transitional, and minimum values of velocity, respectively. Note the duration of a typical contractile cycle is approximately 3.0 s.

A static concentration of C * NO = 0.3, corresponding to a dimensional concentration of 100 nM was applied as a Dirichlet boundary condition at the inlet of the vessel. A zero-flux boundary condition was applied at the outlet, where the concentration was extrapolated from adjacent core cells using a reconstruction gradient. However, when negative velocity values occurred (see Fig. 3 for instances of this), the original outlet effectively became the new inlet and required a Dirichlet boundary condition of C* NO = 0.3, since the zero-flux condition would not be plausible under the new physiologic velocity boundary value. The extruded walls of the entrance and exit regions of the vessel were set to a zero-flux in order to prevent interaction with concentration profiles within the physiologically relevant portion of the geometry. To confirm the absence of initial transient effects, we ran additional simulations to ensure the choice of starting point did not influence the WSS or concentration values at the time points of interest (A, B, and C in Fig. 3). The rms differences in these quantities were < 1% between two different starting points. It is also worth noting that the steady flow case at the initial flow rate was used as the initial state of the system. Residuals for iterations in the steady case and inner iterations for the unsteady case were allowed to reach a value on the order of 10−4 to ensure convergence.

Mesh Independence.

Mesh independence was investigated by comparing steady flow axial WSS values (fully developed inlet condition) in meshes with 95,149, 201,056, 385,080, and 1,202,744 volumetric cells. Less than 6% rms difference in axial WSS was found between the 385,080 and 1,202,744 cell meshes, which compares well with the criteria set forth by Myers et al. [16] in modeling flow in coronary arteries. Therefore, the 385,080-cell mesh was used for all results. For the time-dependent case, the raw velocity was filtered and simulations were performed using 72, 180, and 900 time points corresponding to 0.125 s. 0.05 s, and 0.01 s time steps, respectively. Increasing the number of time steps beyond 180 resulted in less than 0.14% difference in time-averaged WSS values. Therefore, a time step of 0.05 s was used to generate the results presented herein.

Results

Steady Simulation Results.

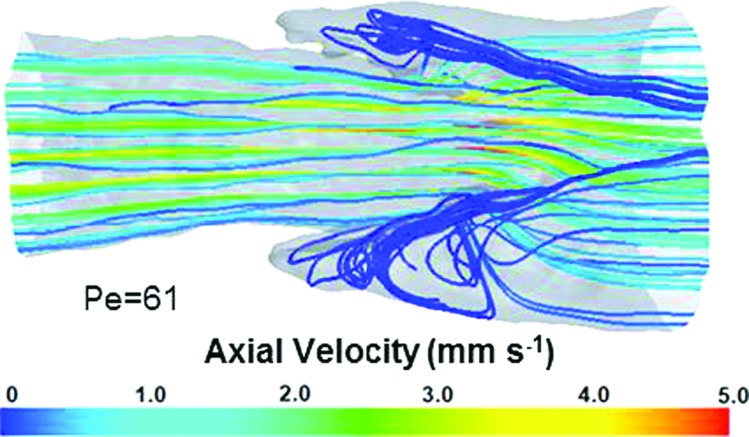

Velocity streamlines revealed areas of flow stagnation adjacent to the valve leaflets in the sinus region (Fig. 4). While flow features in this region appear to be vortex-like in shape, it should be noted that the absolute value of velocities in this region were less than 0.03 mm s−1, compared to an average inlet velocity of 2.0 mm s−1.

Fig. 4.

Representative streamlines for a simulation run at Re = 0.22. Areas of flow stagnation were observed adjacent to the valve leaflets. Although these appear vortex-like in nature, these are regions of essentially zero velocity.

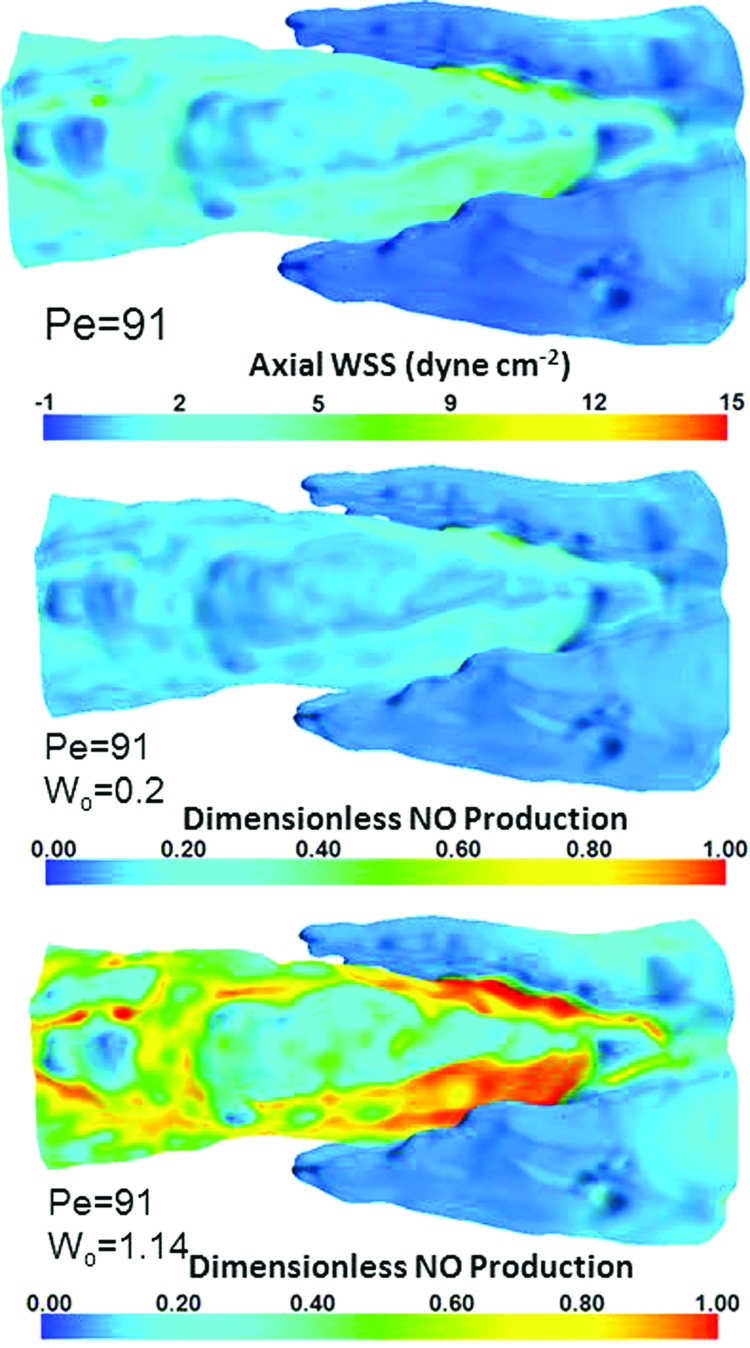

The maximum shear stress occurred near the inner surface of the trailing edges of the lymphatic valve leaflets and was 12.0 dyn cm−2 for an imposed Pe value of 91 (Fig. 5, top). Contours of NO production (Fig. 5, middle and bottom) revealed higher production in areas of elevated WSS dictated by the sigmoidal function used for the flux boundary condition of NO. Higher values of Wo (Wo = 1.14) resulted in an LEC saturation of production occurring at approximately 7.7 dyn cm−2 (Fig. 5, bottom), while lower values of Wo (Wo = 0.2) resulted in much lower sensitivity, with a saturation value occurring at 39.5 dyn cm−2 (Fig. 5, middle).

Fig. 5.

WSS and corresponding NO production distributions. Top: Distribution of axial WSS for Pe = 91; middle: dimensionless NO production for Pe = 91 and Wo = 0.2; bottom: dimensionless NO production for Pe = 91 and Wo = 1.14.

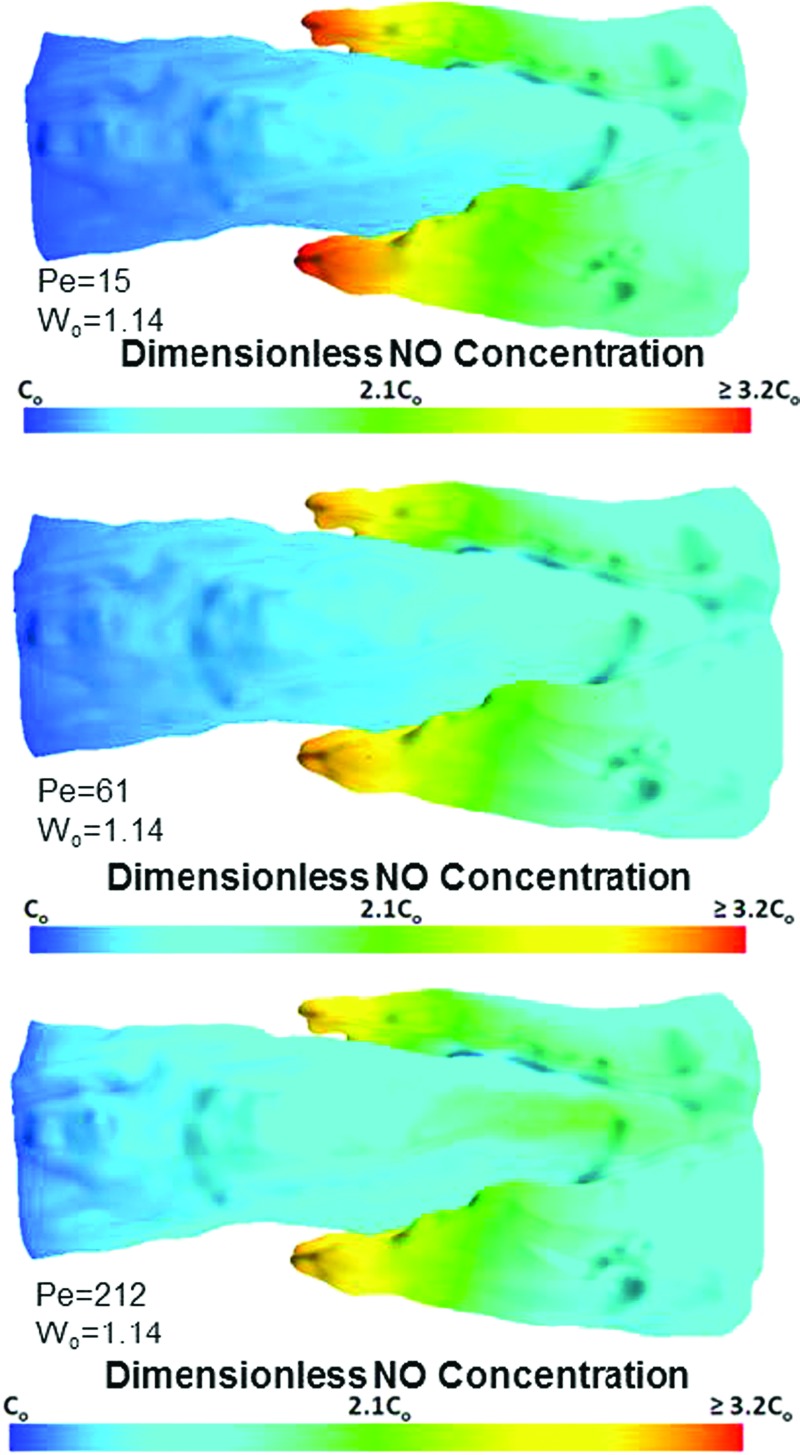

Despite higher production levels in the simulations run with large Pe values, the predominant role of convective forces was evident from the diminished concentration within the lumen of the vessel. The highest concentrations were found near the backside of the valve leaflet insertions in areas of flow stagnation and low WSS (Fig. 6, top, middle, and bottom). Simulations run at lower Pe numbers (Fig. 6, top) resulted in higher concentrations than those run at elevated Pe values (Fig. 6, bottom).This may be attributable to NO being washed out of the lumen of the vessel, due to higher convective forces.

Fig. 6.

Contours of NO at the wall of the vessel for various Pe values. Top: Surface concentration for Pe = 15 and Wo = 1.14; middle: surface concentration for Pe = 61 and Wo = 1.14; bottom: surface concentration for Pe = 212 and Wo = 1.14. Increasing the average Pe value resulted in less wall concentration; however, enhanced Pe values beyond Pe = 61 up until Pe = 212 only resulted in an rms difference in NO concentration of 3.7%.

The flow-mediated decrease in concentration was also evident in the areas of flow stagnation near the valve leaflets. After Pe ≥ 61, the concentration at the wall did not change substantially, as is evident by comparing the two simulations run at the higher Pe values (≤ 3.7% difference) (Fig. 6, middle and bottom panels).

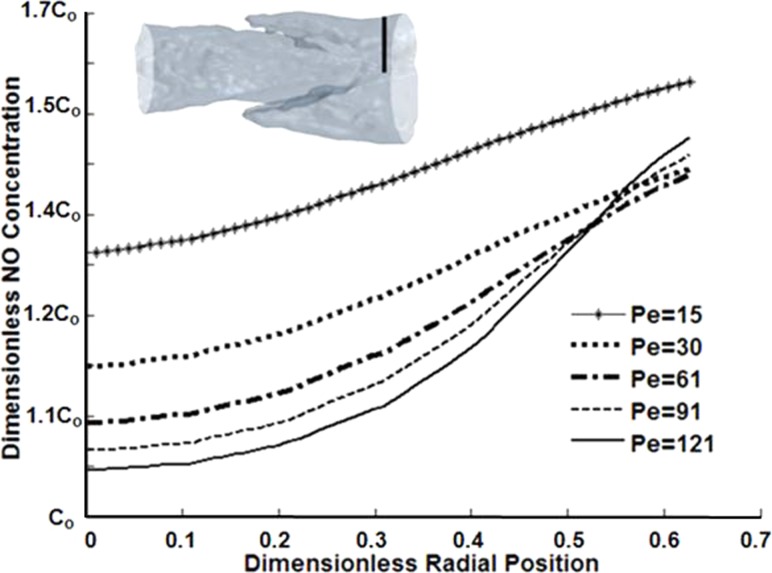

The NO concentrations near the center of the vessel were generally low, due to dominant convective forces (Fig. 7). Closer to the wall, higher concentrations were observed with higher Pe values (Pe > 61), due to increased shear-sensitive production. However, diffusive forces dominated in the simulations run at Pe values less than 30, where high values in concentration were present across all radial values, particularly evident in the case Pe = 15. Generally, at low Pe, diffusion played more of a role in transport and there was a build-up of NO, similar to the observed effect in the sinus region, where flow stagnation occurred.

Fig. 7.

Concentration plotted in the radial direction at an axial location downstream of the valve leaflets

Additionally, we estimated the concentration boundary layer thickness in an upstream portion of the vessel (prevalve) for simulations run with Vo = 0.5 mm s−1 and Vo = 7.0 mm s−1, as the dimensionless ratio δ/a, where δ is the thickness of the boundary layer and a is the local radius of the vessel equal to 37.2 μm for this particular axial location. The NO concentration boundary layer constituted a large portion of the vessel radius in both simulations. Vo = 0.5 mm s−1 resulted in a δ/a of 0.98, while Vo = 7.0 mm s−1 had a δ/a of 0.73.

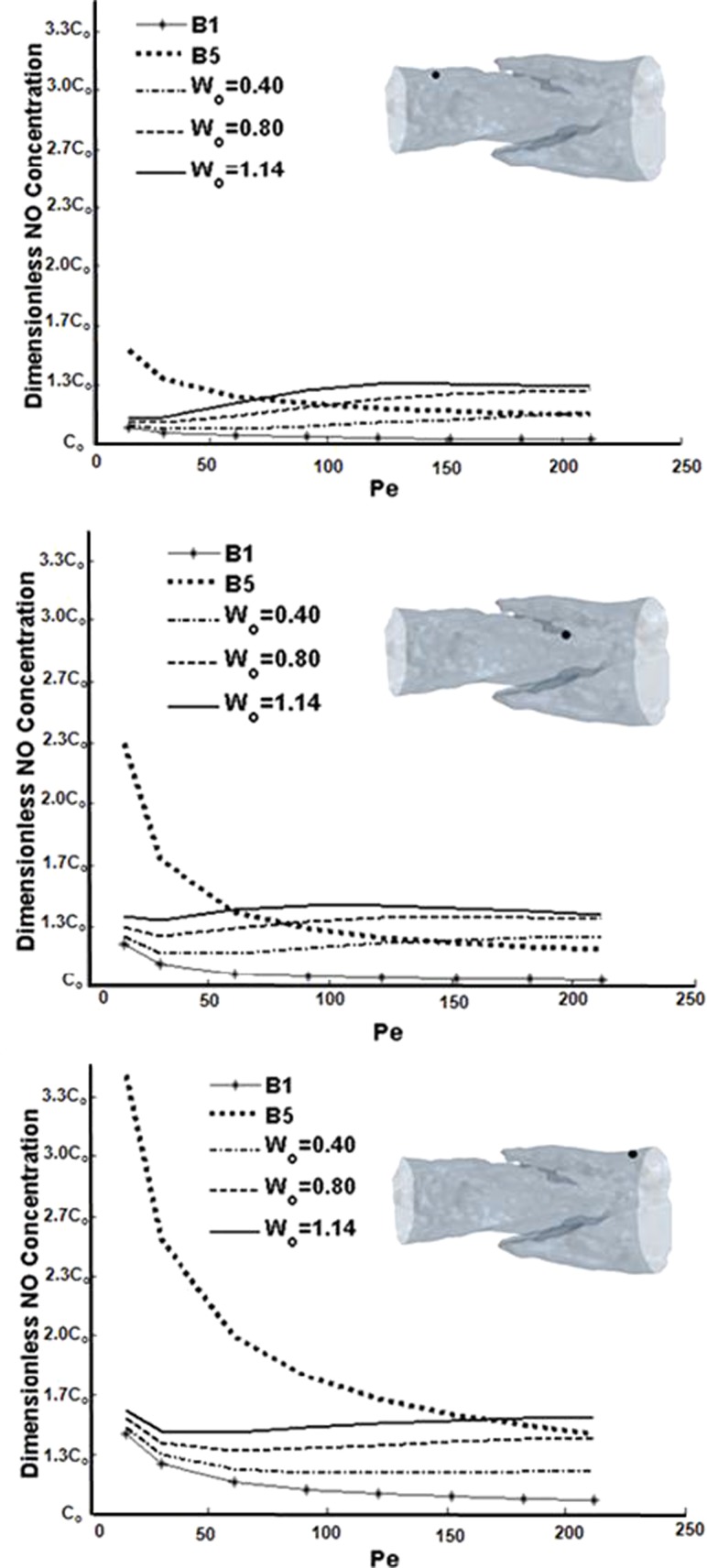

The inclusion or lack of shear-dependent NO production had profound effects on concentration profiles. Wall concentration decreased monotonically by as much as half over the physiologic range of Pe for the baseline B5 constant production case (Fig. 8). The baseline B1 case showed smaller but still monotonic decreases in wall concentrations with increasing Pe. This finding was consistent at all wall locations in the model. However, the simulations where production was shear-dependent resulted paradoxically in the wall concentration being less sensitive to Pe and, thus, shear. The concentration profiles that result from shear-sensitive NO decrease slightly at Pe = 15 but then start to increase at Pe = 30. This initial decrease may be interpreted as the concentration profile being transformed from an effectively purely diffusive behavior to a predominantly convective regime. Thereafter, the slight increases in wall concentration were due to increased production but were offset to some degree by increased convection.

Fig. 8.

Concentration sampled at the wall across a range of Pe and Wo values. Top: point upstream of the valve leaflets; middle: point of highest axial WSS; bottom: point downstream of the valve leaflets.

Unsteady Simulation Results.

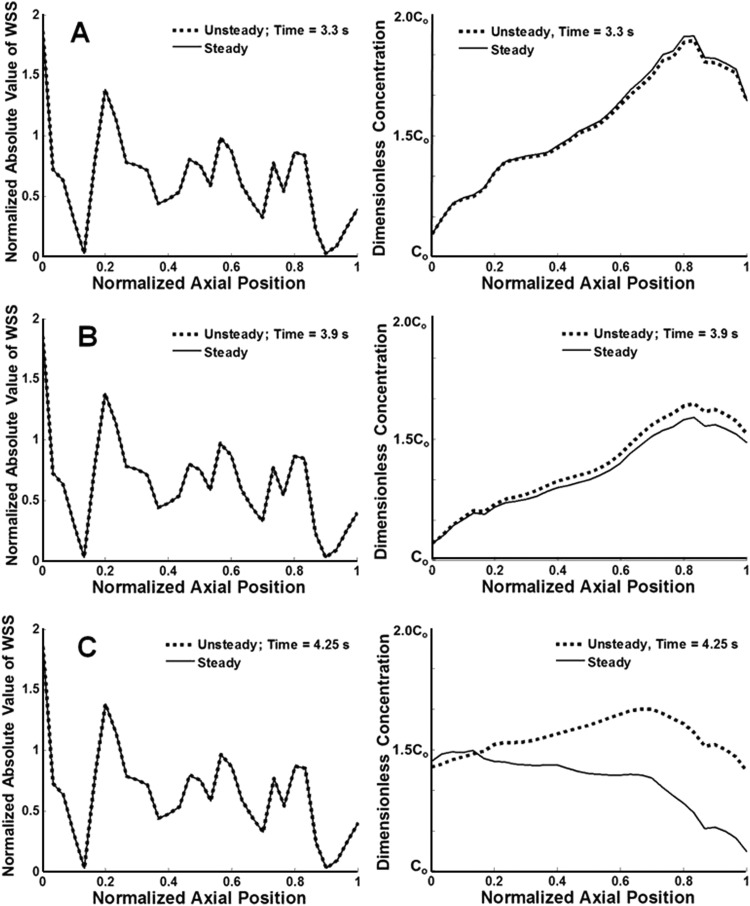

For unsteady simulations, the NO concentration peaked at both positive and negative peak values of WSS, because the sigmoidal NO production dependence on WSS was based on the absolute value of axial WSS rather than a “directional” value (Fig. 9). The peaks in concentration were higher for negative values of WSS, because previously produced NO was transported from areas downstream of the valve site during central lymph flow. Instantaneous concentration and WSS results from the unsteady simulation were compared to those of quasisteady simulations at the corresponding average inlet velocities (Fig. 10). Although many time points were compared, the results listed in Fig. 10 represent data when the flow regime was at its maximum peak (t = 3.3 s), transition into systole (t = 3.9 s), and minimum positions (t = 4.25 s).

Fig. 9.

Concentration at the wall at a location upstream of the terminal edges of the lymphatic valve leaflets

Fig. 10.

Comparison of steady WSS and NO values versus axial position to that of the unsteady case at time points A, B, and C, corresponding to 3.3 s, 3.9 s, and 4.25 s, respectively. WSS values were normalized to corresponding inlet Poiseuille value of WSS.

WSS values across all time points were resolved to less than 1% with the quasisteady approach. However, the RMS difference in concentration profiles between steady and unsteady cases increased with decreasing velocity (Table 3). For example, differences between steady and unsteady concentrations were 0.40% for the simulation run at peak velocity (t = 3.3 s) compared to 6.70% for the simulation run at the minimum velocity (t = 4.25 s).

Table 3.

rms difference in steady versus unsteady simulations

| Time (s) | Velocity (mm s−1) | % rms WSS difference | % rms concentration difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.3 | 4.70 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| 3.9 | 1.58 | 0.13 | 1.14 |

| 4.25 | −1.08 | 0.04 | 6.70 |

Instantaneous concentration values taken at a time when the velocity was small or at a minimum had lingering NO within the computational domain that had not been transferred away, due to the increasingly diffusive nature of the transport scheme. This lingering NO in the unsteady cases was not found in the quasisteady simulations and thus contributed to the percent difference between the two. Based on these findings, unsteady concentration results generally agreed better with steady results in flow regimes with an overall higher velocity.

Discussion

The study presented herein investigated the effects of fluid dynamics and LEC shear-sensitivity on the concentration of NO within the lumen of a lymphatic vessel. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies of this nature conducted on a model obtained from confocal images of a live lymphatic vessel. By implementing shear-sensitive boundary conditions for the production of NO, we were able to understand how the sensitivity of LECs may play a role in the concentration of NO throughout the vessel. Additionally, we showed that areas of high concentration exist within the sinus regions near the valve leaflets, as observed by Bohlen et al. [2]. Our results further validated that a quasisteady analysis is appropriate, particularly for cases where the velocities are elevated.

While the average values of shear within the lymphatic flow regime are approximately 0.64 dyn cm–2 in the tubular region [15], the peak values of shear quantified in simulations at the inner surface of the valve leaflets were generally comparable to WSS values calculated for large arteries [17]. Additionally, high concentrations have been observed experimentally near the valve leaflets in the sinus area, but it was unclear whether this phenomenon was due to high surface area with more LECs to produce NO, higher production rates in general at this site, or whether it is flow-mediated. Furthermore, experiments have shown that an increase in shear results in increased production of NO by LECs in whole lymphatic vessels [2]. We found that LECs in areas of flow stagnation observed in representative velocity streamlines produced NO at a much lower rate than do LECs in the higher shear areas of the vessel. Despite the low production rates in this area, there was substantially more NO present in this region compared to areas of high production, suggesting the high concentration in this area observed experimentally is flow-mediated and due to fluid stagnation as opposed to a higher amount of NO production by LEC in this part of the vessel. Additionally, the extremely low levels of production and highly diffusive effects may outweigh the concept that high surface area of LECs is the sole cause of the enhanced NO levels.

Furthermore, convection plays a major role in NO transport, not only at the wall, but also within the lumen of the vessel. The local Pe numbers generated toward the center of the vessel were much greater than those at the wall and resulted in diminished NO in this region. High NO concentrations at low Pe values were observed for cases where the basal level production was set to the B5 constant production, which intuitively does not make sense, because experiments have shown that higher concentrations of NO increase with elevation in shear [2]. Thus, this model further supports the shear-dependent production of NO by showing that situations where production is constant are physiologically counterintuitive. Additionally, there were no substantial increases in concentration after Pe ≥ 61, suggesting that the role of convection begins to take more of an effect in the transport scheme at this point. Note that Pe = 61 should not be interpreted as any “critical value,” at which convection overcomes diffusion, but simply an approximate condition, at which the role of convection becomes more apparent.

The concentration boundary layer was found to constitute a large portion of the vessel radius. Compared to macromolecules and proteins, such as low-density lipoprotein, adenosine diphosphate, and albumin (diffusion coefficients in plasma of 2.867 × 10−7, 2.37 × 10−6, and 9.0 × 10−7 cm2 s−1, respectively [18]) that have been modeled for the arterial system, NO has a relatively high diffusion coefficient in aqueous solution of 3.3 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 [11], most likely attributed to its gaseous nature and small molecular size. Moreover, the flow situations modeled here feature low Re (< 1) in small vessels, and the importance of diffusion effects are present across distances that compare well with the vessel radius.

The shape of the concentration profiles in this model, particularly those of Fig. 8, qualitatively resemble the concentration plots generated by Plata et al. [5] in their model of NO transport in a parallel plate flow chamber; however, the quantitative values differ substantially. It should be noted that Plata et al. [5] used only one sampling location (near the trailing edge of the culture chamber), so comparisons with those results are limited. The observed differences may be attributed primarily to the complex vessel geometry but also to a number of other factors, including initial conditions, rate of production, and WSS values. In particular, the morphology of the lymphatic vessel wall is not uniform; this would cause substantial variations in WSS and, hence, NO production patterns. The valve leaflets, acting as both a large source of production and concentration “storage” area (flow stagnation), add to this difference as well.

Additionally, we found that peak concentrations in the lymphatic vessel were approximately three times higher than that in a cylinder of similar length and diameter with the same boundary conditions. This highlights the importance of the vessel geometry, particularly the enhanced concentration due to flow stagnation adjacent to the valve leaflets.

We have further shown that the percent difference in WSS between instantaneous values taken from unsteady and quasisteady simulations differ by less than 1% over a range of velocity values, suggesting that a quasisteady approach is more than adequate for resolving the fluid dynamics for this geometry (not unexpected for such viscous flow). An analysis comparing concentration profiles between quasisteady and unsteady velocity simulations revealed increasing percent difference with decreasing velocity. This was attributed to lack of transport of NO for the unsteady case out of the physiologic domain of interest as well as the extruded portions of the vessel in lower Pe simulations. However, when Pe reached a certain value, these diffusive forces were no longer significant and the quasisteady and unsteady concentrations were quite similar, resulting in a decrease in percent difference between the two. While the purpose of the extended regions was to aid in the application of boundary conditions, the lingering NO in these areas did have an effect on the concentration distributions in the physiologic portion of the geometry when velocities were minimal. Thus, the increase in percent difference observed in lower velocities could change, depending on the length of the extensions, but it is expected that the same trend would occur, regardless of extension length, because the initial conditions during unsteady simulations were different than the quasisteady, due to previously produced NO during earlier time steps. Physiologically, the lingering concentrations in the extruded portions of the vessel could represent stagnant NO within tubular portions of the vessel on either side of the valve region. Since the range of velocities investigated under quasisteady conditions in this study were all in the positive range (no backflow or negative velocities), the conclusions from these findings should correlate well to results if a transient velocity profile with corresponding positive velocities was implemented.

A few limitations should be noted when considering this model. The geometry used for all simulations was static, while, in reality, lymphatic vessels contract and expand dramatically over time; thus, the results included in this research are limited to quasisteady and unsteady conditions in a stationary domain. Valve geometries throughout the lymphatic system differ, and the results presented are only from one configuration; performing similar simulations on multiple valve segments would be useful in determining the differences in transport and fluid dynamics attributed to variable geometry. It is possible that leaflet movement would serve to assist in washout of NO in the sinus region. Future studies will investigate this effect. Gradients in NO concentration may also be important in more long-term processes, such as lymphangiogenesis and subsequent valve development. Additionally, unsteady versus quasisteady differences in concentration were only compared for a Wo value of 1.14, but a similar behavior is expected across all values of this parameter. Future work could also include incorporation of diffusion through the vessel wall. Consequently, it would be useful to determine whether the areas of high concentration, such as those found adjacent to the valve leaflets due to flow stagnation, would have the highest amount of diffusion through the vessel wall. This type of analysis would be dependent on the diffusivity of NO within the vessel wall.

Our results showed that high concentrations observed adjacent to the valve leaflets in experimental findings were most likely due to flow-mediated processes. Because higher values of shear led to increasing concentrations at the wall only after Pe was at or above approximately 61, simulations suggested that this value was where convective forces start to greatly affect the concentration distribution. Furthermore, this model supports the mechanism of a shear-sensitive endothelium, because high levels of NO at the wall do not make physiologic sense in low velocity flow regimes as observed when comparing the basal level production cases to WSS-dependent cases. Finally, a quasisteady approach seems to be sufficient for analysis of WSS and NO concentration in a static model of a mesenteric lymphatic vessel.

In short, the concentrations of NO within the lymphatic vessel were found to be sensitive to changes in the convective scheme and LEC sensitivity. Further studies could be conducted to investigate the fully dynamic system of NO transport resulting from vessel wall movement and valvular propulsion of lymph.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the Texas A&M University Supercomputing facility (http://sc.tamu.edu/) for providing computing resources useful in conducting the research reported in this paper. This work was funded, in part, by NIH grant R01 HL094269 and R01 HL070308.

Glossary

Nomenclature

- a =

local vessel radius

- APSS =

albumin-containing physiological saline solution

- CFD =

computational fluid dynamics

- Dij =

diffusion coefficient of NO in aqueous solution

- kNO =

pseudosecond-order auto-oxidative NO reaction rate

- LEC =

lymphatic endothelial cell

- NO =

nitric oxide

- Pe =

Péclet number

- r =

radial position

- R =

representative radius of the lymphatic vessel

- Re =

Reynolds number

- rms =

root-mean-square

- RNO =

NO production rate

- RNO,Max =

maximum nitric oxide production rate

- t =

time

- to =

time scale indicative of one contractile cycle

- =

3D velocity field

- Vo =

average inlet velocity

- Wo =

parameter that dictates saturation level of production by LECs

- WSS =

wall shear stress

- WSSaxial =

axial wall shear stress

- α =

thermal diffusivity

- γ =

parameter that characterizes LEC sensitivity to WSS

- θ =

local azimuthal angle

- * =

dimensionless quantity

Contributor Information

John T. Wilson, Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London, South Kensington Campus, London SW7 2AZ,UK; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Texas A&M University, 5045 Emerging Technologies Building, 3120 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843

Wei Wang, Department of Systems Biology and Translational Medicine, Texas A&M Health Science Center, 702 Southwest H.K. Dodgen Loop, Temple, TX 76504.

Augustus H. Hellerstedt, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Texas A&M University, 5045 Emerging Technologies Building, 3120 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843

David C. Zawieja, Department of Systems Biology and Translational Medicine, Texas A&M Health Science Center, 702 Southwest H.K. Dodgen Loop, Temple, TX 76504

James E. Moore,, Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London, South Kensington Campus, London SW7 2AZ, UK; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Texas A&M University, 5045 Emerging Technologies Building, 3120 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843

References

- [1]. Zawieja, D. C. , 2009, “Contractile Physiology of Lymphatics,” Lymphat. Res. Biol., 7(2), pp. 87–96. 10.1089/lrb.2009.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Bohlen, H. G. , Wang, W. , Gashev, A. , Gasheva, O. , and Zawieja, D. , 2009, “Phasic Contractions of Rat Mesenteric Lymphatics Increase Basal and Phasic Nitric Oxide Generation In Vivo ,” Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol., 297(4), pp. H1319–H1328. 10.1152/ajpheart.00039.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Bohlen, H. G. , 2011, “Nitric Oxide Formation by Lymphatic Bulb and Valves Is a Major Regulatory Component of Lymphatic Pumping,” Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol., 301(5), pp. H1897–H1906. 10.1152/ajpheart.00260.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Fadel, A. , Barbee, K. , and Jaron, D. , 2009, “A Computational Model of Nitric Oxide Production and Transport in a Parallel Plate Flow Chamber,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 37(5), pp. 943–954. 10.1007/s10439-009-9658-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Plata, A. , Sherwin, S. , and Krams, R. , 2010, “Endothelial Nitric Oxide Production and Transport in Flow Chambers: The Importance of Convection,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 38(9), pp. 2805–2816. 10.1007/s10439-010-0039-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Vaughn, M. W. , Kuo, L. , and Liao, J. C. , 1998, “Effective Diffusion Distance of Nitric Oxide in the Microcirculation,” Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol., 274(5), pp. H1705–H1714. Available at: http://ajpheart.physiology.org/content/274/5/H1705.full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Bertram, C. , Macaskill, C. , and Moore, Jr., J. , 2011, “Simulation of a Chain of Collapsible Contracting Lymphangions With Progressive Valve Closure,” ASME J. Biomech. Eng., 133(1), p. 011008. 10.1115/1.4002799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Reddy, N. P. , Krouskop, T. A. , and Newell, P. H. , 1977, “A Computer Model of the Lymphatic System,” Comput. Biol. Med., 7(3), pp. 181–197. 10.1016/0010-4825(77)90023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Rahbar, E. , and Moore, J. E. , 2011, “A Model of a Radially Expanding and Contracting Lymphangion,” J. Biomech., 44(6), pp. 1001–1007. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Incropera, F. P. , DeWitt, D. P. , Bergman, T. L. , and Lavine, A. S. , 2007, Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, John Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Malinski, T. , Taha, Z. , Grunfeld, S. , Patton, S. , Kapturczak, M. , and Tomboulian, P. , 1993, “Diffusion of Nitric Oxide in the Aorta Wall Monitored In Situ by Porphyrinic Microsensors,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 193(3), pp. 1076–1082. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Kanai, A. J. , Strauss, H. C. , Truskey, G. A. , Crews, A. L. , Grunfeld, S. , and Malinski, T. , 1995, “Shear Stress Induces ATP-Independent Transient Nitric Oxide Release From Vascular Endothelial Cells, Measured Directly With a Porphyrinic Microsensor,” Circ. Res., 77(2), pp. 284–293. 10.1161/01.RES.77.2.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Hangai-Hoger, N. , Cabrales, P. , Briceño, J. C. , Tsai, A. G. , and Intaglietta, M. , 2004, “Microlymphatic and Tissue Oxygen Tension in the Rat Mesentery,” Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol., 286(3), pp. H878–H883. 10.1152/ajpheart.00913.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Wiesner, T. F. , Berk, B. C. , and Nerem, R. M. , 1997, “A Mathematical Model of the Cytosolic-Free Calcium Response in Endothelial Cells to Fluid Shear Stress,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 94(8), pp. 3726–3731. 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Dixon, J. B. , Greiner, S. T. , Gashev, A. A. , Cote, G. L. , Moore, J. E. , and Zawieja, D. C. , 2010, “Lymph Flow, Shear Stress, and Lymphocyte Velocity in Rat Mesenteric Prenodal Lymphatics,” Microcirculation, 13(7), pp. 597–610. 10.1080/10739680600893909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Myers, J. , Moore, J. , Ojha, M. , Johnston, K. , and Ethier, C. , 2001, “Factors Influencing Blood Flow Patterns in the Human Right Coronary Artery,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 29(2), pp. 109–120. 10.1114/1.1349703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Moore, J. E. , Xu, C. , Glagov, S. , Zarins, C. K. , and Ku, D. N. , 1994, “Fluid Wall Shear Stress Measurements in a Model of the Human Abdominal Aorta: Oscillatory Behavior and Relationship to Atherosclerosis,” Atherosclerosis, 110(2), pp. 225–240. 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90207-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Karner, G. , Perktold, K. , and Zehentner, H. P. , 2001, “Computational Modeling of Macromolecule Transport in the Arterial Wall,” Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng., 4(6), pp. 491–504. 10.1080/10255840108908022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]