Abstract

The degree of correspondence between objective performance and subjective beliefs varies widely across individuals. Here we demonstrate that functional brain network connectivity measured before exposure to a perceptual decision task covaries with individual objective (type-I performance) and subjective (type-II performance) accuracy. Increases in connectivity with type-II performance were observed in networks measured while participants directed attention inward (focus on respiration), but not in networks measured during states of neutral (resting state) or exogenous attention. Measures of type-I performance were less sensitive to the subjects’ specific attentional states from which the networks were derived. These results suggest the existence of functional brain networks indexing objective performance and accuracy of subjective beliefs distinctively expressed in a set of stable mental states.

Keywords: interoception, metacognition, resting-state, partial-report-paradigm

Decisions often bear upon other decisions, as when we seek a second medical opinion before undergoing a risky surgical intervention. These “metadecisions” are mediated by confidence judgments, the degree to which decision makers consider that their choices are likely to be correct. Confidence judgments can be severely distorted: People may lack confidence when responding correctly and reciprocally, be very confident of incorrect responses (1–6). In classic perceptual tasks followed by a confidence report, one can distinguish between (i) the ability to correctly discriminate between stimulus alternatives, referred to as type-I performance, and (ii) the ability of confidence judgments to discriminate between correct and incorrect responses, referred to as type-II performance (2, 7). The objective of this work is to investigate whether functional brain networks distinctively covary with type-I and type-II performance.

Network organization of resting state functional brain activity can account for individual differences in several cognitive functions (8–13). These studies rely on networks derived from the “resting state” (14, 15). Recently, Tang et al. (16) showed the formation of distinct brain networks in the maintenance of three well-defined mental states that vary the focus of attention: resting, alert, and meditation states (16). Here we capitalize on this idea, deriving functional brain networks for each individual, varying the focus of attention toward internal states (interoception, focus on respiration), external stimulus (exteroception), or remaining in a resting state of free thought.

Interoception (generically defined as the ability to detect subtle changes in bodily systems, including muscles, skin, joints, and viscera) (17), is closely related to metacognition of agency (18, 19). We reasoned that this may more generally reflect a partially overlapping system regulating attention to internal states, including interoception (focus on body systems) and metacognitive ability (focus on internal thoughts and feelings). Hence, our working hypothesis is that increases in functional connectivity with the quality of subjective judgments (type-II performance) should be more sensitive in networks expressed while attention is directed inward compared with networks obtained in other attentional states.

We measured functional networks in three different attentional states: exteroceptive attention (detecting an oddball within a sequence of sounds), interoceptive attention (focusing on respiration), and resting state (relaxing without falling asleep), while a sequence of tones was presented at a very low volume in all states. We then investigated the covariance of functional connectivity, measured in different attentional states, with type-I and type-II performance in a perceptual decision task.

Results

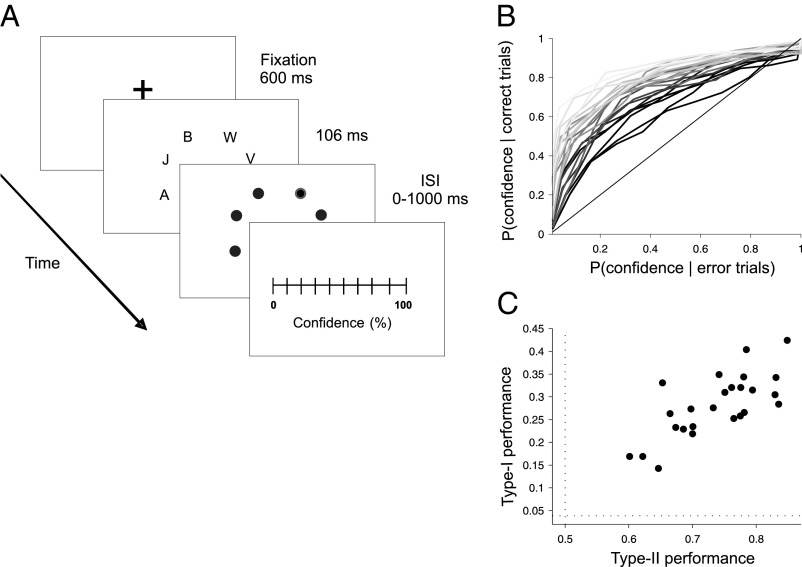

After the functional MRI (fMRI) recordings, participants performed a partial report (PR) experiment, identifying a letter in a cued location of a cluttered field (20) and indicating the degree of confidence in their response in a continuous scale (Fig. 1A) (3). Type-II performance can be quantified by measuring the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AROC) (2, 21). This nonparametric test estimates the degree of overlap between confidence distributions for correct and error trials. Type I and type II varied widely between subjects (Fig. 1 B and C) with a significant correlation (r = 0.74, P < 0.001) but with sufficient dispersion to allow a reliable simultaneous regression of the fMRI signal to both factors.

Fig. 1.

(A) Subjects performed a partial report task experiment identifying a letter in a cued location of a cluttered field (3) and subsequently indicating the degree of confidence in their response in a continuous scale. (B) Individual ROC curves reflect a broad variability in metacognitive accuracy. (C) Type-I and type-II performance show a significant correlation across individuals, but with sufficient dispersion to perform a reliable bivariate regression to both factors. Dotted lines mark random type-I (1/26) and type-II (0.5) performance.

To test whether coherence in spontaneous activity between brain regions in different attentional states covary with type-I and type-II performance, we conducted a functional connectivity analysis, based on 141 standard previously defined cortical regions of interest (ROIs) (22). Following the work of Dosenbach and colleagues (22, 23), ROIs were grouped in five different functional systems: frontoparietal (FP), cinguloopercular (CO), default brain network (DBN), sensorimotor (SM), and occipital (OC) (Fig. S1).

For each attentional state s (interoceptive, exteroceptive, or resting) and participant p we measured a 141 × 141 connectivity matrix Cs,p. The matrix entry Cs,p(i,j) indicates the temporal correlation of the average fMRI signal of ROIs i and j, which henceforth is referred as functional connectivity. To investigate connectivity changes associated with type-I and type-II performance, we conducted an across-subjects bivariate linear regression, between each entry of the correlation matrix Cs,p and type-I and type-II performances of the subject in the PR task. This led to six matrices of beta (β) values, Bs,r(i,j), one per attentional state s and regression r to type-I or type-II performance (Fig. S2). As an example, a positive value of Bresting,type-I(i,j) indicates that connectivity between ROI(i) and ROI(j) increases with type-I performance for networks measured in the resting state.

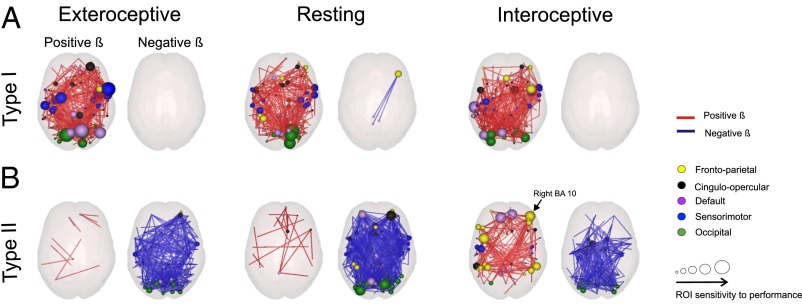

For visualization purposes, we projected Bs,r(i,j) values exceeding a threshold of 3 SDs into glass brains (Fig. 2 A and B). For type-I performance (Fig. 2A), the vast majority of values were positive, showing a marked tendency of increased connectivity with type-I performance. On the contrary, Bs,r(i,j) values indexing how connectivity varies with type-II performance—Bs,type-II(i,j)—showed different patterns across states (Fig. 2B). For networks measured in the exteroceptive and resting states, the vast majority of values were negative, indicating a marked tendency of decrease in connectivity with type-II performance. This pattern was different for networks measured in the interoceptive state. The regression revealed a dense distribution of positive Binteroceptive,type-II values for ROIs localized within the frontoparietal system and negative Binteroceptive,type-II values within medial and occipital regions, involving nodes from the occipital and cinguloopercular systems (Fig. 2B, Right).

Fig. 2.

Dependence of functional brain connectivity with type-I and type-II performance measured by a bivariate regression of connectivity to both factors. Red links denote positive beta (β) values (connectivity increases with performance). Blue links negative β-values (connectivity decreases with performance). For visualization purposes only β whose absolute value exceeded 3 SDs were depicted. For each ROI, the size of the sphere denotes the number of connections exceeding 3 SDs. Color indicates the functional system to which the ROI belongs. (A) β-Values for type-I performance. ROIs whose connectivity varies positively with type-I performance were mostly located in medial and posterior brain regions. The four ROIs with the highest rank in the number of connections exceeding a threshold (for networks measured under exteroceptive state, the state with the highest average β-value) are in dorsal frontal cortex ([60, 8, 34]), occipital cortex ([−16, −76, 33]), the precuneus ([11, −68, 42]) and parietal cortex ([−26, −8, 54]) (see Table 1 for the top 15 ROIs), which is consistent with previous findings of connectivity in the resting state predicting visual performance (11). (B) β-Values for type-II performance. The spatial distribution of ROIs whose connectivity increases for increasing type-II performance was mostly located in frontal regions in the FP and DBN. The 4 ROIs with the highest rank in the number of connections exceeding a threshold (for networks measured under interoceptive state, the state with the highest average β-value) are in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex ([−11, 45, 17] and [9, 51, 16]), the dorsal frontal cortex [−42, 7, 36] and the anterior prefrontal cortex [42, 48, −3] (see Table 2 for the top 15 ROIs).

Table 1.

Regression to type-I performance, top 15 ROIs

| MNI coordinates |

ROI label | Network | ||

| x | y | z | ||

| 60 | 8 | 34 | Dorsal frontal cortex | Sensorimotor |

| −16 | −76 | 33 | Occipital | Occipital |

| 11 | −68 | 42 | Precuneus | Default |

| −26 | −8 | 54 | Parietal | Sensorimotor |

| 45 | −72 | 29 | Occipital | Default |

| 43 | 1 | 12 | Ventral frontal cortex | Sensorimotor |

| 17 | −68 | 20 | Postoccipital | Occipital |

| −55 | −22 | 38 | Parietal | Occipital |

| −36 | −12 | 15 | Mid insula | Sensorimotor |

| 58 | −3 | 17 | Precentral gyrus | Sensorimotor |

| −9 | −72 | 41 | Occipital | Sensorimotor |

| 27 | 49 | 26 | Anterior PFC | Default |

| −41 | −31 | 48 | Postparietal | Cinguloopercular |

| 33 | −12 | 16 | Mid insula | Sensorimotor |

| 60 | 8 | 34 | Dorsal frontal cortex | Sensorimotor |

ROIs with the highest rank in the number of connections whose β-value for type-I performance exceeded a threshold of 3 SDs, for networks measured under exteroceptive state. MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute.

Table 2.

Regression to type-II performance, top 15 ROIs

| MNI coordinates |

||||

| x | y | z | ROI label | Network |

| −11 | 45 | 17 | Ventromedial PFC | Default |

| 9 | 51 | 16 | Ventromedial PFC | Default |

| −42 | 7 | 36 | Dorsal frontal cortex | Frontoparietal |

| 42 | 48 | −3 | Ventral anterior PFC | Frontoparietal |

| 54 | −44 | 43 | Inferior parietal lobule | Frontoparietal |

| −47 | −12 | 36 | Parietal | Sensorimotor |

| −55 | −44 | 30 | Parietal | Cinguloopercular |

| 44 | −52 | 47 | Inferior parietal lobule | Frontoparietal |

| −35 | −46 | 48 | Postparietal cortex | Frontoparietal |

| −5 | −52 | 17 | Postcingulate cortex | Default |

| −52 | 28 | 17 | Ventral PFC | Frontoparietal |

| 40 | 36 | 29 | Dorsolateral PFC | Frontoparietal |

| −54 | −9 | 23 | Precentral gyrus | Sensorimotor |

| −11 | −58 | 17 | Postcingulate | Default |

| −11 | 45 | 17 | Inferior parietal lobule | Frontoparietal |

ROIs with the highest rank in the number of connections whose β-value for type-II performance exceeded a threshold of 3 SDs, for networks measured under interoceptive state.

To quantify these observations, we first reduced the dimensionality of the connectivity matrix by collapsing all of the connections between ROIs belonging to each pair of functional systems to a single scalar value. For each state s and subject p, we derived the average (reduced) connectivity matrix Ĉs,p, a 5 × 5 matrix resulting from all possible pairings between FP, OP, DBN, SM, and OC. Each entry (n,m) of this matrix represents the average connectivity between system n and system m. Note that the interaction between a functional system with itself reflects the interaction between all of the ROIs within this functional system and hence the diagonal elements of Ĉs,p are not trivially and maximally correlated. The entries of these matrices were submitted as dependent variables to an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with type-I and type-II performance as continuous regressors, attentional state (exteroceptive, resting, and interoceptive) as within-subjects factor and subject identity as a random-effect factor. The ANCOVA revealed a main effect for type-I performance [F(1, 21) = 6.26, P < 0 0.05] but not for type-II performance [F(1, 21) = 1.38, P > 0.1]. In Fig. 2 it can be observed that there is a main trend of type-II effect (when regressed together with type I) to decrease connectivity, but this effect does not reach significance when analyzed in an ANCOVA as a main effect. Conversely, we observed a significant interaction between attentional state and type-II performance [F(2, 42) = 3.72, P < 0.05] and a nonsignificant interaction between type-I performance and attentional state [F(2, 42) = 0.37, P > 0.5]. These results show that functional connectivity relates to type-I performance in a way that is independent of the attentional state, whereas the relation between connectivity and type-II performance varies with the attentional state of the subjects.

Next, to investigate the sensitivity of functional networks, measured under different attentional states, to type-I and type-II performance, we submitted independently for each state s, the entries of the reduced connectivity matrix Ĉs,p to three independent intrastate ANCOVAs with type-I and type-II performance as continuous regressors, and subject identity as a random variable. The ANCOVA tests revealed a main effect of type-I performance on networks measured under exteroceptive and interoceptive states [exteroceptive: F(1,21) = 4.95, P < 0.05; interoceptive: F(1,21) = 4.72, P < 0.05]. We observed a main effect of type-II performance on connectivity only in the interoceptive state [F(1,21) = 6.48, P < 0.02], reaching a higher level of significance than all other comparisons. The effect of type-II performance was not significant in the exteroceptive [F(1,21) = 0.88, P > 0.1] or resting [F(1,21) = 0.05, P > 0.1] states.

The ANCOVA analyses described above show the global trends of how connectivity (accumulated over all pairs of functional systems) depends on performance and attentional state. They show that connectivity increases for more accurate type-I performers for all attentional states. Instead, the effect of type-II performance shows a more complex pattern that depends on the attentional state. However, the ANCOVA cannot describe which specific connections contribute to these effects. To this aim we performed a one-sample t test following the ANCOVA reported above. For each attentional state s, regressor (r, type-I or type-II performance), and pair of functional systems Sn Sm, we considered all of the Bs,r(i,j) where ROI(i) belongs to system n and ROI(j) belongs to system m. Note that connectivity (and hence Bs,r) is symmetric. This analysis naturally extends to connections of a system with itself by considering the Bs,r(i,j) values of all of the ROIs within one system (excluding of course the connectivity of a ROI with itself). Then, for each condition and pair of systems (n,m) the statistical significance of the dependence of this specific connection with performance was assessed comparing whether the distribution of dependences [i.e., Bs,r(i,j) values for all ROI(i) - ROI(j) connections] differed from zero, by means of a one-sample t test and correcting for multiple comparisons. A significant negative t value indicates that the distribution of Bs,r(i,j) values for that system pair (n,m) is shifted toward negative values (indicating a tendency to decrease connectivity between systems n and m as performance increases). Instead, a significantly positive t value indicates that the distributions of Bs,r(i,j) for that system pair (n,m) is shifted toward positive values (indicating that connectivity between systems n and m increases as performance increases).

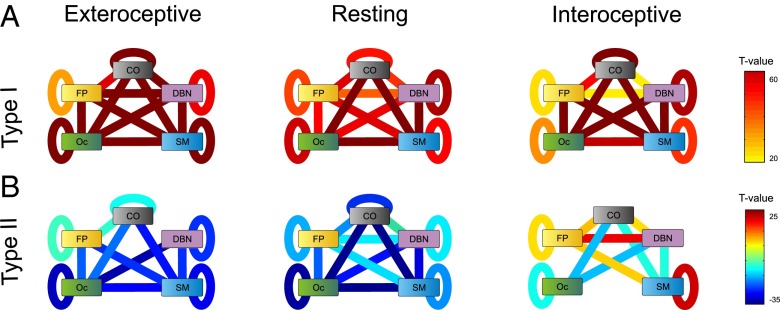

Fig. 3 represents these results displaying a link for each pair of functional systems when the t value of the dependence in connectivity is higher than 5.35, corresponding to a P value of 10−5, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons (Fig. 3 A and B). First, we observe that connectivity between many pairs varied with type I and type II. This shows that the effect of the ANCOVA described above does not result from a sparse distribution of changes but instead from broad and distributed changes in the connectivity pattern. Functional connectivity showed an overall increase in connectivity with type-I performance. A major core, including interactions between OC–CO–SM systems and the SM–DBN interaction, reached the highest levels of significance (Fig. 3A). This indicates that subregions within this core coherently increased their connectivity with increasing type-I performance. For type-II performance, connectivity between functional systems showed an overall decrease with performance for the exteroceptive and resting states. Only for networks measured under the interoceptive state, we observed increases in connectivity with increasing type-II performance, specifically involving systems FP (to SM, DBN, OC, and FP itself), SM (to itself), and CO (to DBN). This reveals a core formed by reciprocal connections between ROIs belonging to the FP–DBN–CO systems whose connectivity shows distinct patterns of dependence with type-II performance in the interoceptive state compared with resting and exteroceptive states.

Fig. 3.

Connectivity between functional systems and its relation with type-I and type-II performance. (A) T values from a one-sample t test analysis quantifying the magnitude of β-values for type-I performance averaged across system pairs, for all attentional states. Negative t values indicate a decrease in connectivity between systems n and m as type-I performance increases, whereas a significantly positive value indicates a connectivity increase between systems n and m increases as type-I performance increases (P value of 10−5, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). (B) T values from a one-sample t test analysis quantifying the magnitude of β-values for type-II performance averaged across system pairs, for all attentional states.

Discussion

We combined measures of objective performance, fluctuations of brain activity in different states, and subjective estimates of performance (24) to investigate which aspects of functional connectivity correlate with the wide variability observed in objective (type I) performance and metacognitive (type II) ability. Specifically, we examined whether increases in functional connectivity with type-II performance are distinctively manifested when attention is directed inward (focus on respiration). We found that connectivity in states of neutral (resting state) or exogenous attention globally decreased with increasing type-II performance. Instead, connectivity measured in the interoceptive state showed a more complex dependence with type-II performance: connectivity within a core formed by FP, SM, and DBN systems increases with type-II performance and connectivity between OC and CO systems decreases with type-II performance. Contrary to this state dependence observed in the covariation of connectivity with type-II performance, the relation between type-I performance and functional connectivity was less sensitive to the specific subjects’ mental states from which the functional networks were derived.

We emphasize that these analyses are only correlational and do not imply any causality or directionality. Our hypothesis is that connectivity between brain regions should have an effect on (type I and type II) performance in a task. On the other hand, the ANCOVA analyses test how connectivity varies as a function of task performance and attentional state. We have tried not to use semantic descriptions involving causal relations (such as “predict” and “explain”) but as a note of caution here we explicitly mention that all our analyses can only show a correlational and nondirectional relation between connectivity and performance.

As expected from previous anatomical (2), lesion (25), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (7) studies, we found that the prefrontal cortex (PFC) was one of the regions whose connectivity was more sensitive to type II performance. This includes Brodmann area 10 and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, known to play an important role in linking objective performance to subjective beliefs (2, 21). However, beyond these specific nodes, we also observed an increase in connectivity with an individual’s type-II performance in a much broader network including ventrolateral PFC, bilateral inferior parietal lobules, angular gyrus, and bilateral precentral gyrus. This observation is in line with theories of conscious perception relying on long-distance brain networks linking prefrontal cortex with other brain regions, including the parietal cortex (26–28).

Our work builds on previous studies showing that variability in several cognitive functions, including reading (11), executive control (12), intelligence (13), insight (10), working memory (8), perceptual learning (29), and attention (9) can be accounted for by the organization of resting state networks. The uniqueness of our work is twofold: First, it distinctively identifies networks that covary with objective (type I) performance on a visual task and metacognitive accuracy (type II). Second, it measures functional networks in different attentional states to examine whether a relatively narrow library of networks of stable mental states may be better indicators of individual traits than measures of resting state per se (16, 30).

Relative to this second specific aim, the most important result of this study is that networks measured during a state of interoception show a distinct pattern of dependence on type-II performance compared with networks obtained in the resting state or state of exteroceptive attention. Only networks measured in the interoceptive state show connections increasing with type-II performance. One of the regions showing increased connectivity to other nodes with type-II performance is the angular gyrus (AG), typically associated with awareness of action authorship (31). However, we did not find a change in connectivity with type II performance for other brain structures involved in interoception, such as insula and anterior cingulate (32, 33). Hence, interoception and metacognitive ability show partial overlap on brain circuitry.

These findings build on Garfinkel and colleagues’ behavioral study (34) of recall and confidence of stimuli presented at different moments of the heart cycle; systole (bursts indicating heart contractions) and diastole (heart relaxations). A deficit in recall was observed specifically for targets perceived with low confidence during the systole. Participants with high interoceptive accuracy were more immune to this deficit in recall and as a consequence confidence becomes a worse indicator of future recall (because both high and low confidence elements are recalled). Thus, participants with high interoceptive accuracy have worse metacognitive accuracy of future recall during the systole. This leads to a negative correlation between type-II performance and introspective ability, which may seem at odds with our finding that only networks measured in the interoceptive state show connections increasing with type-II performance. However, there is no intrinsic contradiction between these results: a partial overlap on brain circuitry of interoception and metacognitive ability may reveal itself as a competition between these processes, yielding results similar to those found by Garfinkel and colleagues (34). In the following paragraphs we argue how these arguments can be sketched for specific predictions of interactions between the systems of metacognitive ability and interoception. More generally, our work on functional brain networks and Garfinkel et al.’s behavioral studies (34), are only the first steps to understanding what may be a complex pattern of interactions between the systems of metacognitive ability and interoception. This may help bridge the fertile but largely disconnected literature of metacognitive ability (2, 35–37) and interoception (17, 32, 33, 38).

Beyond the results described in this study, other predictions derive from the hypothesis of partially overlapping systems of metacognitive ability and interoception: (i) Training interoception—for instance with interventions of mindfulness—may be a vehicle to partially improve metacognitive ability in a broad and nonspecific manner. (ii) Psychiatric disorders with deficits of interoception (such as depersonalization disorders; ref. 39), should reflect a specific deficit in type-II performance without affecting type-I performance. (iii) Synchronic expression of introspective and interoceptive tasks may reflect a bottleneck and hence interference. As in ref. 2, concurrent performance with an interoceptive task may impair (or delay, or interact with) type-II, but not type-I performance. (iv) Finally, a more speculative and theoretically provoking thought is that metacognitive ability and interoception may share a fundamental role in cementing conscious experience. In several psychological theories, metacognition is considered a process of second-order (meta) representation of first-order processes, which is constitutive of consciousness (see ref. 36 for a review). Similarly, interoceptive sensitivity has often been identified as a precursor of consciousness, although of a different kind: awareness of one’s body, which is intimately linked to self-identity and self-consciousness (40). Hence a further prediction that can be examined empirically is that manipulations affecting conscious state (through sleep or mild sedation for instance) should show a correlated fade out of interoceptive and metacognitive abilities.

Our results extend the reach of the covariations of connectivity of previous studies to the domain of metacognition and highlight that mental states of interoceptive, resting, and exteroceptive attention convey different information about future objective performance and accuracy of subjective beliefs. Beyond the specific consequences for the domain of metacognition, our results indicate how information about individual traits may be enriched when based on a set of functional brain networks obtained from different mental states.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Twenty-five subjects (12 male; mean age = 25.06 y) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, no report of history of psychiatric or neurological disorders, and no current use of any psychoactive medications, gave their written consent to participate in the experiment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics committees of the Fundación para la Lucha contra las Enfermedades Neurológicas de la Infancia (Argentina) and Glasgow university (UK). Sixteen subjects were from Buenos Aires and 9 from Glasgow, Scotland. Both groups showed a very similar pattern of results in the main observations of this study (Fig. S3) and hence were pooled together to increase the statistical power.

Partial Report (Behavioral) Experiment.

Several days after the fMRI recordings, participants performed a PR experiment, identifying a letter in a cued location of a cluttered field (3). Participants were asked to report, using a standard keyboard, the letter presented in the position cued by the red circle, which remained on screen until the subject’s response. Random performance is 1/26, because for each trial, subjects had to choose 1 of 26 possible letters. Subsequently, participants indicated the degree of confidence in their response in a continuous scale (Fig. 1A). Performance in the objective task (reporting the letter, or type-I performance) and performance in the subjective task (reporting confidence on response, or type-II performance) were used as linear regressors for functional MRI connectivity. To explore how much of the total variance in the fMRI data was explained by the two behavioral regressors, we calculated the R-square value (Fig. S5).

fMRI Recordings and Analysis.

Functional images from Buenos Aires were acquired on a GE HDx 3.0T MR system with a conventional eight-channel head coil. Twenty-four axial slices (5 mm thick) were acquired parallel to the plane connecting the anterior and posterior commissures and covering the whole brain [repetition time (TR) = 2,000 ms, echo time (TE) = 35 ms, flip angle = 90]. To aid in the localization of functional data, high-resolution structural T1 image [3D Fast inversion recovery spoiled gradient echo (SPGR-IR), inversion time 700 mm; flip angle (FA) = 15, field of view (FOV) = 192 × 256 × 256 mm; matrix 512 × 512 × 168; slice thickness 1.1 mm] was also acquired. Images from Glasgow were acquired on a 3-T Siemens MRI system (Magnetom Vision; Siemens Electric) with the same parameters.

Subjects underwent three functional runs lasting 7 min 22 s each for the Buenos Aires dataset and 12 min for the Glasgow dataset. We ran the experiment in Glasgow with longer time series to assure that the functional networks measured with 7 min 22 s were stable and close to convergence to a stationary value (Fig. S4). Subjects were instructed to keep their eyes closed without falling asleep. Random sequences of tones with the same distribution of duration (200 ms), pitch (400 Hz), and oddball frequency (pitch 410 Hz every 15 tones) were presented every 400 ms during the three blocks at very low volume. In the interoceptive attention run, participants were instructed to focus on their respiration cycle, perceiving the air flowing in and out. In the exteroceptive attention, participants were informed that they would hear a series of sounds and should focus on it. In the resting block, subjects were instructed to relax, not to do any mental effort and not to fall asleep. After the recordings we asked subjects whether they heard the beeps in the other runs. None of the subjects reported noticing the tones in the resting state or interoceptive attention, indicating that in absence of directed attention the tones were camouflaged within the noise of the scanner. Conversely, all subjects reported a consistent approximate number of odd tones during the exteroceptive attention run. As the goal of our study was simply to direct subjects’ attention to different states, we did not measure auditability but sounds were presented with exactly the same parameters in all three states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alejo Salles, Ariel Zylberberg and Simon van Gall for useful suggestions for the manuscript. This work is funded by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), the Secretaría de Ciencia y Técnica de la Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBACYT), and by the Human Frontiers Science Program. M.S. is sponsored by the James McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Understanding Human Cognition – Scholar Award. B.W. is supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. P. Barttfeld was supported by a fellowship from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and a Human Frontiers Science Program research grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1301353110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dienes Z, Seth A. Gambling on the unconscious: A comparison of wagering and confidence ratings as measures of awareness in an artificial grammar task. Conscious Cogn. 2010;19(2):674–681. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming SM, Weil RS, Nagy Z, Dolan RJ, Rees G. Relating introspective accuracy to individual differences in brain structure. Science. 2010;329(5998):1541–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1191883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graziano M, Sigman M. The spatial and temporal construction of confidence in the visual scene. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunimoto C, Miller J, Pashler H. Confidence and accuracy of near-threshold discrimination responses. Conscious Cogn. 2001;10(3):294–340. doi: 10.1006/ccog.2000.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persaud N, McLeod P, Cowey A. Post-decision wagering objectively measures awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(2):257–261. doi: 10.1038/nn1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilimzig C, Tsuchiya N, Fahle M, Einhauser W, Koch C. 2008. Spatial attention increases performance but not subjective confidence in a discrimination task. J Vis 8(5):7.1–7.10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rounis E, Maniscalco B, Rothwell J, Passingham R, Lau H. Theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation to the prefrontal cortex impairs metacognitive visual awareness. Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;1(3):165–175. doi: 10.1080/17588921003632529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampson M, Driesen NR, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Constable RT. Brain connectivity related to working memory performance. J Neurosci. 2006;26(51):13338–13343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He BJ, et al. Breakdown of functional connectivity in frontoparietal networks underlies behavioral deficits in spatial neglect. Neuron. 2007;53(6):905–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kounios J, et al. The origins of insight in resting-state brain activity. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(1):281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koyama MS, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity indexes reading competence in children and adults. J Neurosci. 2011;31(23):8617–8624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4865-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeley WW, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Heuvel MP, Stam CJ, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. Efficiency of functional brain networks and intellectual performance. J Neurosci. 2009;29(23):7619–7624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox MD, et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(27):9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raichle ME. A paradigm shift in functional brain imaging. J Neurosci. 2009;29(41):12729–12734. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4366-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang YY, Rothbart MK, Posner MI. Neural correlates of establishing, maintaining, and switching brain states. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(6):330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn BD, et al. Listening to your heart. How interoception shapes emotion experience and intuitive decision making. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(12):1835–1844. doi: 10.1177/0956797610389191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metcalfe J, Greene MJ. Metacognition of agency. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2007;136(2):184–199. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seth AK, Suzuki K, Critchley HD. An interoceptive predictive coding model of conscious presence. Front Psychol. 2011;2:395. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graziano M, Sigman M. 2008. The dynamics of sensory buffers: Geometric, spatial, and experience-dependent shaping of iconic memory. J Vis 8(5):9.1–9.13.

- 21.Lau H, Maniscalco B. Neuroscience. Should confidence be trusted? Science. 2010;329(5998):1478–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.1195983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dosenbach NU, et al. Prediction of individual brain maturity using fMRI. Science. 2010;329(5997):1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1194144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dosenbach NU, et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(26):11073–11078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jack AI, Roepstorff A. Introspection and cognitive brain mapping: From stimulus-response to script-report. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(8):333–339. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01941-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Cul A, Dehaene S, Reyes P, Bravo E, Slachevsky A. Causal role of prefrontal cortex in the threshold for access to consciousness. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 9):2531–2540. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crick F, Koch C. Are we aware of neural activity in primary visual cortex? Nature. 1995;375(6527):121–123. doi: 10.1038/375121a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehaene S, Naccache L. Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: Basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition. 2001;79(1-2):1–37. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehaene S, Sergent C, Changeux JP. A neuronal network model linking subjective reports and objective physiological data during conscious perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(14):8520–8525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332574100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldassarre A, et al. Individual variability in functional connectivity predicts performance of a perceptual task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(9):3516–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113148109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barttfeld P, et al. State-dependent changes of connectivity patterns and functional brain network topology in autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(14):3653–3662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrer C, et al. The angular gyrus computes action awareness representations. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(2):254–261. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craig AD. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig AD. Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13(4):500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garfinkel S, et al. What the heart forgets: Cardiac timing influences memory for words and is modulated by metacognition and interoceptive sensitivity. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(6):505–512. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleming SM, Huijgen J, Dolan RJ. Prefrontal contributions to metacognition in perceptual decision making. J Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6117–6125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6489-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau H, Rosenthal D. Empirical support for higher-order theories of conscious awareness. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(8):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zylberberg A, Barttfeld P, Sigman M. The construction of confidence in a perceptual decision. Front Integr Neurosci. 2012;6:79. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(2):189–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simeon D. Depersonalisation disorder: A contemporary overview. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(6):343–354. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsakiris M, Tajadura-Jimenez A, Costantini M. 2011. Just a heartbeat away from one’s body: Interoceptive sensitivity predicts malleability of body-representations. Proc Biol Sci 278(1717):2470–2476.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.