Abstract

The occurrence of intracellular ice formation (IIF) is the most important factor determining whether or not cells survive a cryopreservation procedure. What is not clear is the mechanism or route by which an external ice crystal can traverse the plasma membrane and cause the heterogeneous nucleation of the supercooled solution within the cell. We have hypothesized that one route is through preexisting pores in aquaporin (AQP) proteins that span the plasma membranes of many cell types. Since the plasma membrane of mature mouse oocytes expresses little AQP, we compared the ice nucleation temperature of native oocytes with that of oocytes induced to express AQP1 and AQP3. The oocytes were suspended in 1.0 M ethylene glycol in PBS for 15 minutes, cooled in a Linkam cryostage to –7.0 °C, induced to freeze externally, and finally cooled at 20 °C/min to –70 °C. IIF that occurred during the 20 °C/min cooling is manifested by abrupt black flashing. The mean IIF temperatures for native oocytes, for oocytes sham injected with water, for oocytes expressing AQP1, and for those expressing AQP3 were –34, –40, –35, and –25 °C, respectively. The fact that the ice nucleation temperature of oocytes expressing AQP3 was 10° to 15° C higher than the others is consistent with our hypothesis. AQP3 pores can supposedly be closed by low pH or by treatment with double-stranded AQP3 RNA. However, when morulae were subjected to such treatments, the IIF temperature still remained high. A possible explanation is suggested.

Keywords: Cryopreservation, Mouse, oocyte, embryo, intracellular ice, aquaporin

Introduction

The most important factor determining the success of cryopreservation is whether or not a cell undergoes intracellular ice formation (IIF) during freezing. In classical slow freezing, IIF is avoided by cooling cells sufficiently slowly so that osmotic dehydration results in their water remaining in near chemical potential equilibrium with the outside solution and ice. When cells are cooled too rapidly to achieve this, they become increasingly supercooled; and at some subzero temperature, they undergo IIF. In some cases, IIF occurs at or very near the lowest temperature at which the supercooled state can be maintained, the so-called temperature for homogeneous nucleation (Th). In cells the size of mouse oocytes that temperature is ~–40 °C (Mazur et al. 2005b). But in many other cases, IIF occurs at temperatures well above Th and is said to occur by heterogeneous nucleation.

We have argued that the heterogeneous nucleator of the supercooled water in cells is external ice. One route by which an external ice crystal might traverse the lipid bilayer membrane is through pores in preexisting transmembrane proteins. One family of such proteins that are constitutively present in the membranes of many cell types and which contain central pores are the aquaporins (AQPs). In AQP1, and probably in the others, the pore is hourglass shaped and the diameter at the neck is so narrow that the pore should not allow the passage of more than one molecule of water at a time, much less allow the passage of the assembly of ice molecules that constitute even a tiny ice crystal. But we consider it possible that the force generated by ice crystal growth might be sufficient to enlarge the pore.

No constitutive AQPs have been found in mouse oocytes or in mouse embryos ranging from the 1-cell (zygote) through the uncompacted 8 cell (although the 8-cell may possibly express traces of AQP9) (Barcroft et al., 2003; Matsuo et al., 2008). However, Edashige et al. (2003) have developed a molecular procedure for inducing the expression of AQP3 in mouse oocytes. They and their colleagues have achieved similar results with oocytes of Xenopus and fish, which also lack constitutive aquaporins (Valdez et al. 2006; Yamaji et al. 2006; Seki et al. (2007). The first line of evidence that the Edashige et al. procedures resulted in the expression of functional AQP3 in mouse oocytes was a several-fold increase in the permeability of the oocytes to water and to the low molecular weight nonelectrolyte solutes glycerol and ethylene glycol (EG). AQP3 is a glyceroaquaporin. It increases water permeability somewhat with low activation energy (Ea), but mostly it enhances the permeability of low molecular weight nonelectrolytes like glycerol and ethylene glycol. The second piece of evidence was that immunofluorescence showed the AQP3 protein to be localized at the plasma membrane. The procedure was the same as that described here. In the present paper, using the same two criteria, we report a similar procedure for obtaining the functional expression of AQP1 in mouse oocytes.

Compacted 8-cell embryos (= early morulae) are different from oocytes in that they express AQP3 natively (Barcroft et al., 2003; Edashige et al.,2006, 2007). As evidence of this, Edashige et al. (2006) found their water permeability to be ___fold greater than that of oocytes.

In the process of compaction, the blastomeres of the 8-cell embryo are transformed from an assembly of independent stacked cannon balls to a “tissue” in which contiguous plasma membranes between two blastomeres form tight junctions and gap junctions (Valdimarsson & Kidder 1995).

We (Seki & Mazur 2010a) have recently determined that the IIF temperature in mouse oocytes and in embryos ranging from zygotes to uncompacted 8-cell embryos is essentially the same and very low (–35 to –43 °C). However in compacted 8-cell (early morulae), it is –23 °C. The fact that the abrupt ~17 °C rise in the IIF temperature occurs at exactly the same developmental stage as the appearance of functional AQP3 and gap junctions, strongly suggests a cause and effect relationship.

A central aim of this research has been to elucidate whether extracellular ice can traverse the plasma membrane through aquaporin pores and can act as the heterogeneous nucleator of the supercooled water in cells. To achieve this, we have compared the ice nucleation behavior of normal mouse oocytes (which lack detectable AQP channels) with that of oocytes induced to express AQP3 or AQP1 and with that of early morulae which natively express AQP3, but not AQP1.

Results

The detection of intracellular AQP3 and AQP1 protein by immunofluorescence

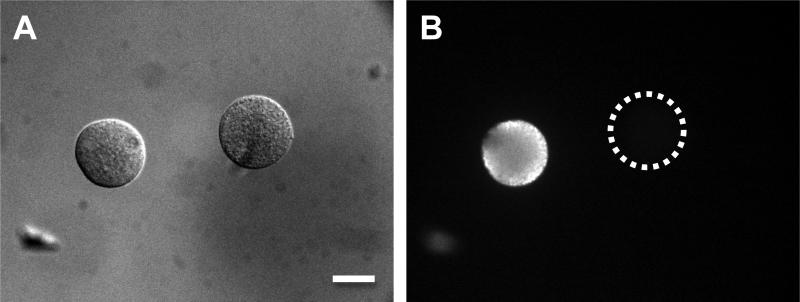

Edashige et al. (2003; 2007) demonstrated by immunofluorescence that after exogeneous expression procedures, AQP3 proteins were located in the plasma membrane of mouse oocytes at metaphase II stage. We have now demonstrated the same in AQP1. Figure 1 shows that AQP1 protein has been synthesized in the cell and is preferentially located at or near the plasma membrane. Although we can confirm the expression of AQP1 protein in the cytoplasm near the plasma membrane, we could not clearly confirm it to be in the plasma membrane. However, their permeability to water is 2.99 (μm/min/atm) which is 4-5 times higher than that (0.70) in intact oocytes (Table 3), thus strongly indicating that AQP1 protein is located in the plasma membrane.

Figure 1.

The detection of AQP1 proteins in oocytes by immunofluoresence. Mouse oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage were injected with cRNA of human AQP1, and cultured for 12-14 h. The expression of AQP1 was detected by immunofluoresent-staining using anti-rat AQP1 rabbit antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobin goat antibody. A, an uninjected oocyte (right) and a cRNA-injected oocyte (left); B, the same two cells under fluorescence microscope. The bar indicates 50 μm. Edashige et al. (2003, 2007) have obtained analogous immunofluorescence data for AQP3 proteins in mouse oocytes.

Table 3.

Intracellular flashing temperature of AQP3 cRNA injected mouse oocytes at pH 5.7 vs. 7.1.

| Stage | Injection | pH | Flash temperature ±S.E. (°C)** | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MII stage | None | 7.1 | –34.4±1.7 | 57 |

| None | 5.7 | –39.3±1.2 | 10 | |

| AQP3* | 7.1 | –24.5±2.4 | 11 | |

| AQP3* | 5.7 | –24.9±2.9 | 11 |

AQP3 cRNA were injected into oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage, and the oocytes were cultured to the MII stage.

Oocytes suspended in 1 M EG/PBS and subjected to the cooling procedures shown in Table 5.

There are no differences between the flash temperatures at pH 5.7 and those at pH 7.1.

The water permeability (Lp) of oocytes expressing AQP1 or AQP3

The water permeability of each oocyte that had been injected with AQP1 or AQP3 cRNA was determined as indicated in Methods. The water permeability of normal untreated oocytes and morulae was measured on randomly selected samples. The results are summarized in Table 1. The Lp of the AQP1- and AQP3-expressing oocytes was 4× and 9× that of controls, respectively. The difference is probably more a matter of differences in the number of aquaporins inserted in the plasma membranes than of inherent differences in the Lp of each AQP assembly.

Table 1.

Comparison of the water permeability (Lp) at 25°C of mouse oocytes expressing AQP1 or AQP3, or morulae embryos vs. the Lp of untreated oocytes and water injected oocytes

| Stage | Injection | Lp (μm/min/atm) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| MII oocyte | None | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 20 |

| Watera | 0.67 ± 0.20 | 11 | |

| AQP1 cRNAa | 2.99 ± 0.94 | 10 | |

| AQP3 cRNAa | 6.29 ± 0.79 | 22b | |

| Morulae | None | 3.25 ± 0.32 | 6 |

Water, AQP1 cRNA, or AQP3 cRNA were injected into oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage, and then the oocytes were cultured to the MII stage.

Lp of two other oocytes were extremely high (50, 94) and were not included in this data.

Edashige et al. (2003, 2006) have reported similar values of Lp for these stages and conditions; namely, 0.83, 0.87, and 3.09 for control, water injected, and AQP3 cRNA injected oocytes; and 3.93 for uninjected morulae.

The effect of AQP1 and AQP3 expression on the temperature of IIF in mouse oocytes

Table 2 shows the IIF temperatures of mouse oocytes that were induced to express AQP1 or AQP3. The IIF temperature of water-injected control oocytes (–40.4 °C) and that of the oocytes injected with AQP1 cRNA and expressing AQP1 (–34.8 °C) were not significantly different from that of normal control oocytes (–34.4 °C). But the IIF temperature of oocytes induced to express AQP3 (–24.5 °C) was about 10 °C higher than in the previous group (P< 0.05) and 16 °C higher than in the water-injected control.

Table 2.

Intracellular flashing temperature of mouse oocytes injected with AQP1 cRNA or AQP3 cRNA

| Stage | Injection | Flash temperature ±S.E. (°C)** | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| MII stage | None | –34.4±1.7a | 57 |

| Water* | –40.4±1.3a | 12 | |

| AQP1* | –34.8±2.1ab | 10 | |

| AQP3* | –24.5±2.4b | 11 |

Water, AQP1 cRNA, or AQP3 cRNA were injected into oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage, and the oocytes were cultured to the MII stage.

Oocytes suspended in 1 M EG/PBS and subjected to the cooling procedures shown in Table 5.

Values with different subscripts were significantly different (P < 0.05).

The effect of AQP3 closure in acidic condition on the temperature of IIF in mouse oocytes

Table 3 shows the effects of acidifying the EG/PBS medium on the the IIF temperatures of normal oocytes and of oocytes induced to express AQP3. The IIF temperature of the untreated controls is about 14 °C below that of the oocytes expressing AQP3, but there is no effect of pH. This means that acidic conditions did not make the oocytes more fragile and did not affect the IIF temperature. If the closure of AQP3 affects the IIF temperature, one would expect the IIF temperature of AQP3-expressing oocytes at pH 5.7 to be lower than that at pH 7.2. But that was not the case.

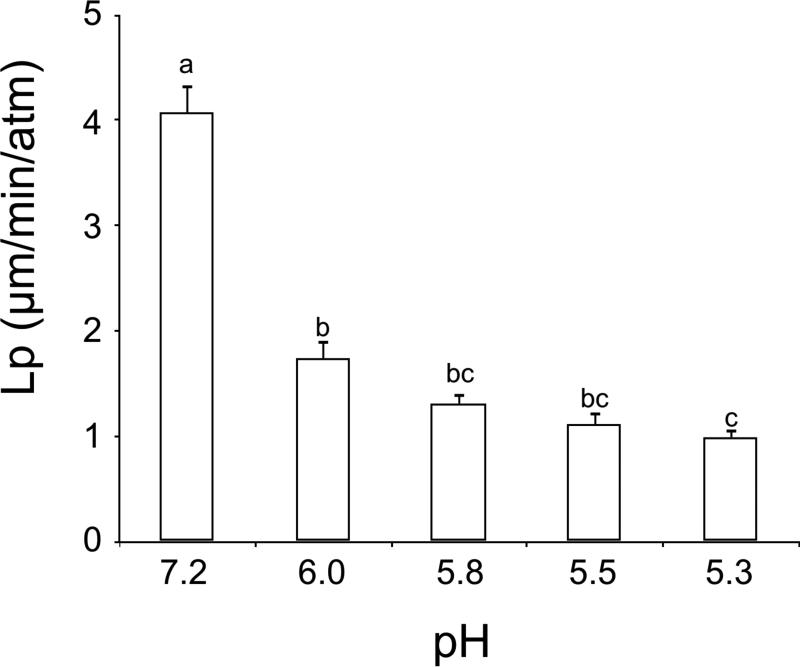

The effect of pH on the permeability of mouse morulae to water and cryoprotectants

Figure 2 shows the permeabilities to water in morulae at pH 7.2, 6.0, 5.8, 5.5 and 5.3. The Lp at pH 7.2 was 4.08 (μm/min/atm), about equal to the Lp of oocytes forced to express AQP3 (Table 3). As the pH of medium was lowered to 5.3, the Lp underwent a four-fold decrease to 0.99 μm/min/atm. Thus, in morulae, lowering the pH to 6.0 or lower produces a 3 to 4-fold decrease in Lp (Figure 2) but no decrease in the IIF temperature (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Water permeability (Lp, μm/min/atm) of early mouse morulae at pH 7.2, 6.0, 5.8, 5.5 and 5.3. The error bars are standard deviations of the mean. Values with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). The numbers of embryos were 9-11 for each bar.

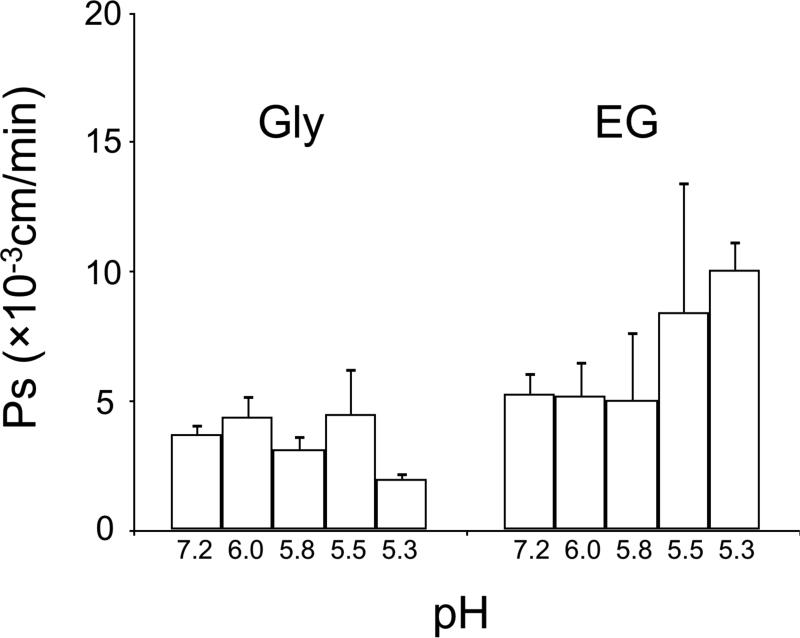

Figure 3 shows analogous data on the effects of pH on the permeability coefficient (Ps) for EG and glycerol in mouse morulae. There is little or no effect of pH on the Ps for glycerol, but there is a large effect on the Ps for EG; namely, the permeability is approximately doubled in going from pH 5.8–7.2 to pH 5.3. This is the opposite of the effect of pH on the Lp of the morulae.

Figure 3.

Permeability (Ps, ×10−3 cm/min) of mouse morulae at pH 7.2, 6.0, 5.8, 5.5 and 5.3. There were no significant differences in all pH (P > 0.05). The number of embryos was 2-7 for each bar.

The use of double-stranded AQP3 RNA to suppress the normal expression of AQP3 in mouse morulae and its effect on the IIF temperature of the morulae

The native early morula expresses AQP3, and Table 1 shows that its Lp is 3.25 μm/min/atm. This is 5-times higher than that of the MII oocyte, which does not express AQP3. We have recently shown (Seki and Mazur 2010a) that the ice nucleation temperature of the early morula is also about 12°C higher than that of the MII oocyte (–23°C vs. –35°C). Edashige et al have shown and we have confirmed that if zygotes are injected with double-stranded AQP3 RNA instead of the standard single stranded form, and allowed to develop, the resulting morulae appear not to express AQP3 as evidenced by a 3-fold drop in Lp from 3.25 to 1.05 μm/min/atm, a value close to that of oocytes.

These findings indicate that with ds-AQP3 RNA, AQP protein is either not incorporated into the plasma membrane, or does not form the usual membrane pores. In either case, one would expect that if the pores are absent, they can not serve as a route for seeding by extracellular ice, and the ice nucleation temperature of the morulae should drop from –23°C towards –35°C. But the experiments summarized in Table 4 indicate that is not the case. The nucleation temperature of the native morula is –23.1°C, and that of morulae derived from dscRNA treated zygotes is –19.4°C–essentially unchanged. We shall return to this apparent anomaly in the Discussion.

Table 4.

Intracellular flashing temperature of mouse morulae developed from zygotes injected with ds-AQP3 RNA

| Stage | Injection | Flash temperature ±S.E. (°C) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| MII stage | None | –34.4±1.7a | 57 |

| Morulae | None | –23.1±1.5b | 30 |

| ds-AQP3 RNA | –19.4±1.5b | 7 |

* ds-AQP3 RNA was injected into zygotes, and the embryos were cultured to the morulae stage.

Values with different letter superscripts were significantly different (P < 0.05).

Discussion

We reported (Mazur, et al. 2005b) that IIF in mouse oocytes suspended in 1 M EG in PBS occurs at –35 °C. In a more recent paper (Seki & Mazur 2010a), we have shown that the IIF temperatures of 1-cell, 2-cell, 4-6-cell, and early 8-cell embryos range from –37 to –43 °C. These temperatures indicate that nucleation of the intracellular supercooled water in these stages is occurring homogeneously; i.e., by the stochastic formation of a critically sized ice embryo that can grow spontaneously. However, the IIF nucleation temperature of compacted 8-cell embryos (early morulae) is markedly higher; namely, –23.1 °C. The developmental stage at which this marked rise in nucleation temperature occurs coincides with the appearance of AQP3 and gap junctions and is presumbly causally related to one or both of these events.

Since the nucleation of oocytes or of 1-cell to 8-cell embryos is occurring by homogeneous nucleation, we need not postulate the presence of heterogeneous nucleators or the presence of transmembrane pores through which external ice can grow. But there are challenges in accounting for the much higher nucleation temperatures observed in early morulae and in explaining how ice propagates from one blastomere to another in the morulae. There is considerable evidence that the blastomere to blastomere propagation occurs through the pores in gap junctions which form in the tight junctions between the plasma membranes of contiguous cells. Seki and Mazur (2010a) have presented such evidence in mouse morulae. Acker et al. (2001) and Irimia and Karlsson (2002) have presented the evidence in tissue culture cells. According to Saez et al. (2003), the pores are hourglass in shape. The outer surfaces have radii of 12-20 A° that narrow to 7.5 A° in the center. Thus, the diameter of the gap junction pore is sufficient to allow such propagation (Seki & Mazur 2010a). In contrast, gap junctions would not be expected to provide a route for the penetration of external ice into the supercooled cytoplasm because they are not present in the single plasma membrane that boarders the external compartment.

Conversely, one would not expect AQPs to play a role in the propagation of intracellular ice between individual blastomeres since presumably they are not present in these tight junctions. But they might play a role in the passage of ice from the partly frozen external medium into the supercooled cell interior if they are present in the portion of the plasma membrane of the cell that faces that medium. In the Introduction, we mentioned that, if unaltered, the 2.8 A° (Sui et al. 2001) constriction in the pore of AQP1 would be too small to allow the passage of any ice crystal; however, it is possible that it could be enlarged by the forces generated by the growth of the external ice. While the diameter of the constriction in the pore in AQP3 has not been ascertained, it is believed to be 3.8 A° (King et al. 2004); consequently, the same considerations apply.

Evidence that AQP3 channels serve as routes by which external ice can pass through the plasma membrane and cause intracellular ice nucleation

AQP3 has not been found in the membranes of oocytes or of 1-cell to 8-cell embryos. In all these stages, intracellular ice nucleation occurs at or near the homogenous nucleation temperature (Seki & Mazur 2010a). This indicates that IIF is occurring spontaneously without the need to invoke extracellular ice as the nucleating agent.

But AQP3 is present in the plasma membranes of compacted 8-cell embryos (= early morulae) (Barcraft et al., 2003; Edashige et al. 2006; 2007). These morulae exhibit the essential characteristics of membranes with functioning aquaporins; namely, (1) Lp is increased some 10-fold over that in earlier stages, and (2) the activation energy (Ea) of Lp is decreased from 12 kcal/mole to 4 kcal/mole. Furthermore, the ice nucleation temperatures rise from –43 °C to –35 °C for precompaction embryos and MII oocytes to –23.1 °C for morula (Seki & Mazur 2010a, Table 3). This rise indicates that ice nucleation in the supercooled morulae is heterogenous and that external ice is the likely nucleator.

Although AQP3 is not present in the native oocyte, Edashige et al (2003) have succeeded in expressing it, as evidenced by the immunological location of the AQP3 protein in the membrane, and by the high Lp of such oocytes. Furthermore, we show in Table 4 that the intracellular ice nucleation temperature of these oocytes is 10 to 15 °C higher than that of untreated oocytes (–24.5 °C vs. –34 to –40 °C) and is essentially identical to the nucleation temperature of morulae (–23 °C), which as noted, possess AQP3 endogenously. This rise in nucleation temperature supports the view that AQP3 pores may permit external ice to pass into the supercooled cytoplasm.

In contrast, the incorporation of AQP1 pores in the oocyte membranes had no effect on the IIF temperature. The temperatures were –34.8 °C for them, –34.4 °C for untreated oocytes, and –40.4 °C for oocytes sham injected with water (Table 4). All three temperatures are close to the homogeneous nucleation temperature. Since AQP1 has been shown to be incorporated in the plasma membrane of oocytes induced to express it (e.g. it increases Lp some 4 times [Table 3]) and since this incorporation does not raise the nucleation temperature above Th, it means that whatever membrane distortion, if any, is associated with the incorporation of AQP1 pores, it does not change the nucleation temperature. We posit that this is also true for AQP3; that is, that the 10 to 15 °C rise in nucleation temperature is not due to the production of distortions or defects in the plasma membrane from its incorporation but is due to the ability of the larger AQP3 pore to allow the permeation of external ice.

Consequences of exposure to AQP inhibitors on the IIF temperature

Inhibition by acidic pH

Zeuthen and Klaerke (1999) have reported that acidic conditions (pH ≤ 6) have no effect on water flow through AQP1 pores expressed in Xenopus oocytes. In contrast, acidic conditions produce a near total abolition of water flow through AQP3 pores induced in Xenopus oocytes. If low pH has the same effect on AQP3 pores artificially expressed in mouse oocytes, one might expect the nucleation temperature of AQP3-expressing oocytes to drop from the –24.5 °C shown in Table 5 for pH 7.1 to near –40 °C if the pH were lowered to 5.7. Clearly, that did not happen. One reason for the discrepancy is suggested from the effect of acid conditions on the Lp of early morulae shown in Fig. 2. Acid conditions clearly decrease the Lp, but they do not reduce it to zero. It remains about 25% of the control value at pH 7.2. This could either mean that 25% of the AQP3 pores are still open at say pH 5.3 to 5.8 and 75% are completely closed, or it could mean that the pores in 100% of the aquaporins are 75% closed, or it could be some percentage in between. In theory, it only takes ice propagation through a single pore of proper dimensions to initiate IIF, and the membrane contains thousands of AQP3 pores. As mentioned, the structure of the AQP3 channel has not yet been determined, but the narrow constriction is believed to be about 1 A° wider than that in AQP1 (Sui et al., 2001; King et al., 2004).

Table 5.

Linkam cryostage cooling and warming ramps for oocytes frozen in 1.0 M ethylene glycol/PBS

| Ramp No. | Rate (°C/min) | Limit (°C) | Hold (s) | Capture interval (s)* | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | –5.0 | 0 | 30 | Cooling |

| 2 | 2 | –8.0 | 0 | 10 | Cooling; EIF** |

| 3 | 2 | –3.2 | 10 | 10 | Warming; partial thawing |

| 4 | 10 | –7.0 | 0 | 10 | Cooling |

| 5 | 20 | –70.0 | 0 | 10 | Cooling; IIF** |

| 6 | 10 | –5.0 | 0 | 30 | Warming and thawing |

| 7 | 10 | +20 | 60 | 20 | Warming and thawing |

Time interval in seconds between the storage of the successive images on the hard drive

EIF and IIF refer to extracellular and intracellular ice formation, respectively.

Inhibition by double stranded AQP3 RNA

The expression of functional aquaporin 3 in morulae can also be inhibited by treating zygotes with double stranded RNA. We find that it does so based on its reducing the permeability of the morulae to water 3-fold– from 3.25 μm/min/atm (Table 1) to 1.05 ± 0.06 (n=7). But as is the case with acidification, there is no corresponding decrease in the intracellular ice nucleation temperature. It is –23.1°C in native morulae and –19.4°C in morulae previously treated with double stranded AQP3 cRNA (Table 4).

Thus, both acidification and treatment with ds AQP3 RNA inhibit the functional expression of AQP and both produce a substantial reduction in the Lp of morulae. But neither produces any lowering of their ice nucleation temperature. The answer to this apparent paradox is we believe the following. With cells possessing aquaporin pores in their plasma membranes, the overall permeability to water depends on the ratio of the aggregate cross-sectional area of all the pores to the area of the lipids in the bilayer and to the relative permeability per unit area of each component. The Lp values in Table 1 suggest that water permeation through the bilayer is 0.7 μm3/μm2/min/atm and that through AQP3 channels in the morula is 6.29 minus 0.7= 5.6 μm3/μm2/min/atm. When treated with ds AQP3 RNA, the permeability of water through aquaporin 3 channels drops to 1.05 – 0.7 = 0.35 μm3/μm2/min/atm. In other words, with this simplistic analysis, treatment with ds AQP3 RNA reduces the permeability to water through AQP3 pores to 0.35/5.6, or 6% of normal. In this scenario, if the surface membranes of the blastomeres of a morula normally contain 100,000 functional AQP3 pores, treatment with ds AQP3 RNA would reduce this to 6,000 fully functional pores. (Alternatively, one could hypothesize that all 100,000 pores have their properties changed to reduce their water permeability to 6% of normal).

We argue that the ability of AQP3 pores to permit the passage of extracellular ice and the ice nucleation of supercooled cytoplasm, has a very different functional relationship than does Lp to the number of functional pores present. The ability of a pore to permit the passage of external ice ought to depend much more on the diameters of the pores then on their number. At the limit, only one pore of normal dimensions is necessary for ice nucleation. Continuing with our hypothetical example, we argue that the 6,000 residual functional pores in the morula treated with ds AQP3RNA will permit nucleation at the same temperature as 100,000 pores.

As mentioned, the structure of the AQP3 channel has not yet been determined by X-ray diffraction. However, the narrow constriction is believed to be about 1 A° wider than that in AQP1 (Sui et al. 2001; King et al. 2004). That is consistent with the fact that AQP3 is a glyceroaquaporin and as such it also enhances the permeation of EG and glycerol. [Figure 3 shows an interesting and so far unexplained result; namely, in sharp contrast to its effect on Lp, acidity increases the permeability of mouse morulae to EG. Strangely, it has no effect on glycerol permeation.

Inhibition by mercuric compounds

Some 50? years ago, long before the discovery of the water channel Aquaporin 1 and its high abundance in human erythrocytes, Ponder and others found that their permeability to water was very high and that that high permeability was abolished by exposure to mercuric compounds (Macy, 1984). Later it was found that the mercuric compounds interacted with the aquaporins.

Consequently, we tried to use HgCl2 to inhibit water permeation through AQP3 pores expressed in mouse oocytes. Normal oocytes (which lack aquaporin pores) supercool to –35°C in 1 M EG, but when they were treated with HgCl2, they underwent IIF immediately after EIF at about –7°C. Clearly, the HgCl2 exposure treatment caused major damage to the plasma membranes. We did not attempt experiments with other mercuric compounds.

Conclusions

When mouse M II oocytes in 1 M EG or glycerol are rapidly cooled at 20°C/min, they do not undergo intracellular ice formation (IIF) until –35°C or –40°C even though ice formed in the outside medium at about –7°C. That means that the cell interior supercools some 30°C before it freezes. That in turn has to mean that the plasma membrane prevents external ice from crossing it. Thus, IIF occurs by homogeneous nucleation. The above also applies to all embryonic stage from the zygote to the early 8-cell. But it does not apply to compacted 8-cell embryos ( early morulae). The reason, we suggest, is that the plasma membranes in this latter stage natively express aquaporin 3 and the central pore in that protein permits the passage of external ice. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the IIF temperature in the early morula rises from the ~–40°C in earlier stages to –23°C. The mouse oocyte does not natively express aquaporins, but it can be induced to do so. When it is induced to express AQP3, its IIF temperature rises to –24.5°C, about the same as with the morulae.

One would expect that if the expression of AQP3 causes the oocytes/morulae to undergo IIF at markedly higher temperatures, the inhibition of AQP expression would have the opposite effect; i.e., it would lower the IIF temperature. That turned out not to be the case. Acidification and the use of double stranded AQP3 RNA have both been shown to substantially reduce water permeability, but neither produces the expected result of lowering the ice nucleation temperature. We speculate as to why this might be the case.

As mentioned earlier, another type of pore forms in compacted 8-cell embryos and morulae; namely, that in the gap junction that forms across the dual bilayer constituting the tight junctions between blastomeres. As discussed in our recent paper (Seki & Mazur 2010a), there is accumulating evidence that the cell-to-cell propagation of intracellular ice occurs through the pores in the gap junctions in mouse morulae. But the initial intracellular freezing event in multicellular systems occurs through the portions of the plasma membranes that face the freezing external medium, and that portion does not contain fully formed gap junctions. Nor can IIF occur through the channels in gap junctions of single cells, for single cells lack gap junctions.

Materials and methods

Creating AQP1- and AQP3-expressing oocytes, requires special micromanipulation and injection equipment and considerable experience in these techniques and the relevant molecular biology, both of which were available in Dr. Edashige's laboratory in Japan but are lacking in Knoxville. Consequently, to determine their ice nucleation behavior, it was necessary to ship the oocytes/embryos from Japan to Knoxville in the vitrified state. Since the AQP-expressing oocytes were to be vitrified in Japan, we considered it essential that at least initially the control oocytes be from the identical source and be subjected to vitrification in the same laboratory. We have since reported in some detail our evidence that in terms of osmotic behavior, plasma membrane integrity, and ice nucleation behavior, the control oocytes used in our experiments were not affected by their having been previously vitrified (Seki & Mazur 2010b).

Collection of oocytes/embryos

Approximately half of the control oocytes and morulae used in this study were collected in Japan and vitrified before shipment to Tennessee. The other half were collected in our laboratory at Tennessee and used without prior vitrification.

Mature female mice of the ICR colony were induced to superovulate with intraperitoneal injections of 5 IU of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) (Sigma) and 5 IU of hCG (Sigma) given 48h later. For the collection of embryos, females were mated with mature males of the same strain.

To obtain oocytes at metaphase II, matured oocytes surrounded by cumulus cells were collected from the ampullar portion of the oviducts 13 h after hCG injection and were freed from cumulus cells by suspending them in modified phosphate-buffered saline (PB1) (Whittingham, 1971) containing 0.5 mg/ml hyaluronidase followed by washing with fresh PB1 medium (non-injected oocytes).

The preparation of the mouse metaphase II oocytes that express AQP1 or AQP3 artificially was carried out in Kochi University, Japan. Oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage (immature oocytes) were obtained by puncturing the follicles on the ovaries of female mice without injection of hCG, 46-50 h after the injection of eCG. Then, these oocytes were injected with water (control), AQP1 cRNA, or AQP3 cRNA and cultured for 12 hours until they matured to the metaphase II stage as previously described.

To obtain normal untreated embryos, mature female ICR mice injected with eCG and hCG were mated with male ICR mice. Oviducts of mated animals were flushed with PB1 medium 25 h after the injection of hCG and 1-cell embryos collected and cultured for 56-68 h until they developed to the morulae stage.

All experiments were approved by IACUC protocol 911-0607 of University of Tennessee and the Animal Care and Use Committee of College for Kochi University.

Preparation of AQP1 and AQP3 cRNA

Human AQP1 cDNA was cloned at Kochi University from commercial plasmid (American Type Culture, Collection, VA, USA; ATCC™ number, 99583) and rat AQP3 cDNA was cloned from rat kidney cDNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described previously (Edashige et al. 2003; 2007; Valdez et al. 2006; Yamaji et al. 2006; Seki et al. 2007). The sense strands for AQP1 cDNA cloning was 5′- CGGAATTCCAGCATGGCCAGCGAGTTC -3′, and the antisense strand was 5’-CGTCTAGATCTATTTGGGCTTCATCTCC-3′ (underlined sequences indicate inserted EcoR I and Xba I sites, respectively). The sense strands for AQP3 cloning was 5′-CGGAATTCCATGGGTCGACAGAAGGAGTT-3′, and the antisense strand was 5′-GCTCTAGAGATCTGCTCCTTGTGCTTCA-3′ (underlined sequences indicate inserted EcoR I and Xba I sites, respectively). These primers were derived from the human AQP1 sequence (Moon et al. 1993) (Genbank™ accession No. U41517) and the rat AQP3 sequence (Echevarria et al. 1994) (Genbank™ accession No. L35108). The following profile was used for PCR: 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1.0 min, 58 °C for 0.5 min, and 72 °C for 1.0 min. The PCR product included the open reading frame of human AQP1 or rat AQP3. The fragments of the PCR product was subcloned into the EcoR I/ Xba I site for AQP1 or AQP3 of a pTNT™ vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Capped cRNA of AQP1 or AQP3 were synthesized using SP6 polymerase (Takara, Otsu, Japan) after digestion of the constructed plasmid DNA by Dra III (New England Biolabs, MA, USA) or BamH I (Takara), respectively. The linearized plasmid DNA was digested using a DNase I Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), and the resulting capped RNA was further purified with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The synthesized cRNA was resuspended in RNase-free water (1 pg/pl).

Preparation of Double Stranded AQP3 RNA

As described in Edashige et al. 2007, to synthesize AQP3 dsRNA, the cDNA of mouse AQP3 was cloned from mouse kidney cDNA by PCR with the sense primer 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTCTCGGGTGCTTGCGCTA-3′ and antisense primer 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGACACAGGGAGCGGTTTA-3′ (underlined are the T7 promoter sequences). These primers were derived from the mouse AQP3 sequence (Ma et al., 2000). The PCR was conducted for 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 62 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec. The PCR product contained the open reading flame of AQP3 sequence. From this product, the dsRNA of AQP3 was synthesized with the T7 RiboMAX Express RNAi System (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microinjection of AQP1 or AQP3 cRNA into mouse oocytes or AQP3 dsRNA into Mouse Zygotes

About 20-40 oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage were placed in a 200 μl drop of PB1 medium covered with paraffin oil in a Petri dish (90 × 10 mm). Then an oocyte was held with a holding pipette connected to a micromanipulator on an inverted microscope and injected with 2-5 pl of water (control), AQP1 cRNA, or AQP3 cRNA solution (1 pg/pl) with an injection needle connected to another micromanipulator. Then, the oocytes were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator (5% CO2 in air) for 12-14 h in modified Eagle medium (11090-081; Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (26140-079; Gibco BRL), 50 μg/ml sodium pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, 60 μg/ml penicillin G, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin (maturation medium). Oocytes without the germinal vesicle and having a polar body after culture were considered matured and were used as water- (control), AQP1 cRNA- or AQP3 cRNA-injected oocytes. As another control, we used non-injected oocytes. Only a limited number of matured oocytes were used in each experiment because the culture period for maturation needed to be limited to 12-14 h in order not to use matured but aged oocytes.

To prepare AQP3-suppressed morulae, an embryo at the 1-cell stage was held with a holding pipette connected to a micromanipulator on an inverted microscope in PB1 medium and injected with 2-10 pl of water (control) or AQP3 dsRNA solution (1 g/l) with an injection needle connected to another micromanupilator. As an additional control, noninjected embryos were used. The injected embryos with normal shape just after injection were cultured in M16 medium that was supplemented with 10 μM EDTA, 1 mM glutamine, and 10 μM ß-mercaptoethanol (Pedro et al., 1997) in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37 °C (5% CO2 and 95% air) for 56-68 h, until they developed to the morula stage. Only compacted 8-cell embryos or early morulae were used in the experiments.

Confirmation of AQP-expression in oocytes

Evidence that a cell is expressing functional aquaporins in its membrane is of two sorts. One is to demonstrate immunologically that the aquaporin protein has been synthesized in the cell and is preferentially located at or near the plasma membrane. In previous study, we confirmed that the injection of rat AQP3 cRNA made oocytes express AQP3 protein (Edashige et al. 2003). The other is that the treated cell possesses a water permeability (Lp) up to 10 × higher than that exhibited by a cell that does not express aquaporins, and that the activation energy of that Lp is about 4 kcal/mole as opposed to the usual 12 kcal/mole exhibited by a cell that lacks aquaporin channels. Since AQP 3 is a glyceroaquaporin, an additional characteristic of its expression is that the permeability of the cell to EG or glycerol is substantially higher than that of a cell that lacks AQP3.

Immunological detection of AQP 3 and AQP 1

The expression of AQP3 in mouse oocytes has been confirmed immunologically in the papers of Edashige et al. (2003; 2007). To determine whether AQP1, is similarly expressed, we tested for the presence of the protein by immunofluorescent-staining using a commercially available anti-human AQP1 rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology, inc. sc-20810) that cross-reacts with human AQP1. This protocol is based on the method in papers (Barcraft et al. 2003; Edahsige et al. 2006; 2007). After dezonation with acidic Tyrode's buffer at pH 2.5, noninjected and AQP1 cRNA-injected oocytes were fixed with a 2% paraformaldehyde solution in Dulbecco's Ca, Mg free PBS (PBS(-), Gibco) at room temperature for 30 min, and washed with PBS (-) containing 5 mg/ml BSA. The samples were then incubated with PBS (-) containing 0.01% Triton X-100 (Invitrogen, HFH10), 0.1 M lysine (Sigma), 1% non-immune goat serum (Sigma, G9023) at room temperature for 30 min. After rinsing with PBS (-) containing 5 mg/ml BSA, the oocytes were incubated with anti-human AQP1 rabbit antibody at 1:100 dilution in antibody dilution/wash buffer (ADB solution; 0.1 M lysine, 0.005% Triton X-100, 1% normal Goat Serum in PBS (-)) at 4 °C for 8 hours. After washing with ADB solution, oocytes were incubated with diluted fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) –conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin goat antibody (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz biotechnology, sc-2012, 200 mg/0.5 ml) in ADB solution at 25 °C for 2 hours, washed with ADB solution, and observed under a fluorescence microscope for the location and intensity of the fluorescence.

Evidence of functioning aquaporins from measurements of water and cryoprotectant permeability

To confirm the expression of AQP1 and AQP3, the permeability to water of each treated oocyte and embryo was determined by measuring the rate of its shrinkage after transfer from isotonic PB1 medium to PB1 medium that contained 0.43 M sucrose at 25 °C for 5 min (Edashige et al. 2003; 2006; 2007; Pedro et al. 1997). The osmolality of sucrose was calculated to be 0.50 Osm/kg from the published data on its colligative properties in aqueous solutions (Wolf et al. 1970; Kleinhans 1998; Kleinhans & Mazur 2007). The osmolality of PB1 medium (isotonic buffer: 0.30 Osm/kg) was measured with a freezing-point depression osmometer (OM801; Vogel, Giessen, Germany). The total osmolality of the hypertonic sucrose solution was 0.80 Osm/kg.

Acidic conditions are reported to close the pores of AQP3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Echevarria et al. 1994). To confirm this, the permeabilities of mouse morulae to water, glycerol, and EG were determined at pH 7.2, 6.0, 5.8, 5.5, or 5.3. After exposure to PB1 at those pH's for 5 min, the embryos were exposed to PB1 media including 0.43 M sucrose, 8% (v/v) ethylene glycol, or 10% (v/v) glycerol at each pH. The permeabilities were determined from the recorded volume change as described previously (Edashige et al. 2003; 2006; 2007; Pedro et al. 1997; 2005).

Each oocyte or embryo was placed in a 100 μl drop of PB1 medium and covered with paraffin oil in a Petri dish (90 × 10 mm), and was held with a holding pipette (outer diameter of 80-120 μm) that was connected to a micromanipulator on an inverted microscope. The temperature of the paraffin oil covering drops of PB1 medium containing sucrose or a cryoprotectant was considered to be the temperature of the solution, and was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C by controlling the temperature of the room. The oocyte or embryo held with the holding pipette was then covered with a covering pipette that had a larger inner diameter (approximately 200 μm) and that was connected to another micromanipulator. Then, by sliding the dish, the oocyte or embryo was introduced into a drop of measurement solution (PB1 medium that contained sucrose, ethylene glycol or glycerol). By removing the covering pipette, the oocyte or embryo was abruptly exposed to the new solution (Edashige et al. 2003; 2006; Pedro et al. 2005).

The hydraulic conductivity (Lp) and cryoprotectant permeability (Ps) were calculated from the measured rate of shrinkage (or swelling) of oocytes or embryos after transfer from isotonic PB1 medium to the anisotonic measurement solution at 25 °C for 5 min (PB1 medium containing sucrose) or 10 min (PB1 containing a permeable cryoprotectant). The microscopic image of the oocytes/embryos during exposure to the measurement solution was recorded by a time-lapse videotape recorder (ETV-820; Sony, Tokyo, Japan) every 0.5 sec. for 5 or 10 min. The cross-sectional area of oocytes/embryos was measured using an image analyzer (VM-50; Olympus). This was expressed as a relative cross-sectional area, S, by dividing it by the area of the same oocyte in isotonic PB1 medium. The relative volume was obtained from V = S3/2. The values of Lp and Ps were considered to be the values that provided the best fit of the classical water permeability equation and the solute permeability equation to the experimentally determined values of cell volume vs. the time in the hypertonic medium (Kleinhans, 1998). The classical water permeability equation is dV/dt= LpARTN (1/V–1/Ve), where V is the absolute volume of cell water, t is time, and A, R, T, N are the area of the cell surface, the gas constant, the absolute temperature, the osmoles of solute in the cell. Ve is the volume of cell water after equilibrium has been attained. The water voume equals the measured cell volume minus the volume of the cell solids and bound water.

The Lp of the normal mouse oocytes, which lack detectable aquaporins, is between 0.4 and 0.8 μm/min/atm (Leibo 1980; Edashige et al. 2003). If AQP1 and AQP3 are expressed in the plasma membrane, the Lp will be increased. If it was increased to more than 1.5 μm/min/atm, we considered that AQP1 and AQP3 had been expressed significantly.

Vitrifying oocytes/embryos and shipment

Oocytes expressing AQP1 or AQP3 were vitrified in Kochi University Japan. Ethylene glycol (EG) was diluted to 20% and 40% (v/v) with FS solution, which is PB1 medium containing 30% (w/v) Ficoll 70 (average molecular weight 70,000; GE Healthcare, Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) plus 0.5 M sucrose, to make EFS20 and EFS40, respectively (Kasai et al. 1990; Zhu et al. 1993). EAFS10/10 consisted of 10% (v/v) EG and 10.7% (w/v) acetamide dissolved in a stock consisting of 30% (w/v) Ficoll 70 and 0.5 M sucrose in PB1. The final concentrations of sucrose and Ficoll 70 are 0.4 M and 24% (w/v) (Pedro et al. 1997; Seki & Mazur 2008). (The letters E, A, F and S stand for EG, acetamide, Ficoll, and sucrose. The 10/10 refers to the volume % of EG and acetamide; the 20 and 40 are the volume % of EG.).

The following solutions were successively aspirated into 1/4 ml straws: a 60 mm column of PB1 medium containing 0.5 M sucrose, a 20 mm air bubble, a 5 mm column of vitrification solution (EAFS10/10 for normal or water-injected oocytes and for AQP1-expressing oocytes, EFS40 for AQP3-expressing oocytes and for normal or water-injected morulae, a 5 mm air bubble, and a 12 mm column of vitrification solution containing the oocytes or embryos. Normal oocytes, water-injected oocytes, and AQP1-expressing MII oocytes were exposed to EAFS10/10 for 2 min at 25 °C. AQP3-expressing oocytes and normal morulae were exposed to EFS40 for 1 min at 25 °C. The morulae that had been injected with dsAQP3 RNA as zygotes were suspended in EFS30 for 2 min. During the exposure times, the oocytes and embryos were transferred into the previously prepared 12 mm column of appropriate vitrification solution in each straw and the end of the straw opposite the polyvinyl alcohol plug was heat-sealed. At the conclusion of the defined exposure time, the straw was placed for 3 min or more in liquid nitrogen (LN2) vapor at –120 to –150 °C and then into LN2. For shipment from Japan, the straws were transferred to a Taylor Wharton dry cryogenic shipper (Theodore, AL, USA) and sent to Knoxville by express mail. Upon receipt, the shipping container was checked to make certain it still contained LN2.

For experiments in Tennessee, the vitrified oocytes or embryos in a straw were warmed rapidly in water at 25 °C, and mixed with PB1 medium containing 0.5 M sucrose at 23-25 °C. Some 10 min later, the oocytes and embryos were transferred at 25 °C to PB1 lacking sucrose, and then incubated in previously prepared droplets of M16 medium for some 2 h.

Experimental media and sample preparation

The experiments consisted of suspending the oocytes or embryos in a 1.0 M solution of EG in PBS, loading them on a Linkam cryostage, cooling them at 20 °C/min to –70 °C, and observing and recording the temperature at which they froze internally. Specifically, oocytes or embryos were transferred from a PB1 droplet to 1 ml of Dulbecco phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.2) containing 1.0 M EG and 0.001% (w/v) Snomax (a commercial preparation of freeze-dried Pseudomanas syringii, the ice nucleating bacterium (York Snow, Victor, NY, USA). Snomax is included to minimize the supercooling of the suspending medium. Zeuthen and Klaerke (1999) have reported that an external pH below 6.0 causes the closing of AQP3 pores (but not AQP1 pores) in Xenopus both with respect to water and glycerol. Therefore, in one experimental group, we adjusted the pH of PBS to 5.7 with 1N HCl.

Then, 15 min later after adding oocytes or embryos to the experimental medium, a 1.5 μl droplet of the medium in each of the experimental groups was placed in the center of a 50 or 75 μm thick spacer in a Linkam quartz sample cuvette, the oocytes/embryos pipetted in a minimum volume into that droplet, and a cover glass applied. (The oocytes/embryos are 75 μm in diameter; nevertheless, the 50 μm spacer was used in most runs because the thinner layer of frozen medium yielded much better optics. With respect to IIF, the response of the oocytes/embryos was no different than with the 75 μm spacer.) The sample cuvette was then inserted in a Linkam BCS 196 cryostage (Linkam Scientific Instruments, Waterfield, UK) and the freezing-thawing run initiated. The stage was attached to a Zeiss microscope, and the sample observed with a 20× objective for a displayed magnification of 500×. The images are displayed at 40 frames/s on a monitor and captured on a computer hard drive at desired intervals as short as 1 image/10 s. In a few cases where changes occurred rapidly, the computer monitor was videotaped at 40 frames/s.

The Linkam cryostage, freezing protocols, and Ramps

Using liquid nitrogen vapor for cooling and electrical resistors for heating, the Linkam cryostage with its associated Pax-it software allows samples to be subjected to sequential ramps in which cooling rate, limiting temperature, holding time, and warming rate can be specified. The ramps used here are shown in Table 5. The procedure was as follows: the oocytes/embryos were cooled rapidly to –5.0 °C, and cooled slowly to –8.0 °C (Ramp 1 and 2). EIF occurred at a mean of –7.0 °C. The sample was warmed (Ramp 3) to –3.2 °C, which is just below the melting point of the medium. Most, but not at all, the external ice melted. Re-cooling was then initiated in Ramp 4 after a 10 sec hold at the end of Ramp 3. The purpose of Ramp 3 was to provide time for the external liquid medium, the external ice, and the supercooled water in the cell to come to near equilibrium before re-cooling began. If Ramp 3 was omitted, the IIF temperature was about 20 °C higher than when the warming or an equivalent hold time were included (Mazur et al. 2005a).

Statistics

Error figures in tables and error bars in graphs are standard errors (standard deviations of the mean). Tests of significance were carried out by one-way ANOVA using Graphpad Software's Instat, V. 3.02 followed by the Tukey-Kramaer Multiple Comparison Test. Usually 1 to 5 oocytes or morulae were frozen in a single run and n is the total number subjected to given treatments.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of the following undergraduate and graduate students of Dr. K. Edashige and M. Kasai at Kochi University, Japan, in collecting and vitrifying the oocytes/embryos sent to Knoxville: Dr. B Jin, M Tanaka, S Ohta, K. Matsuo, T Kuwano, M Fuchiwaki, T Kouya, T Hara, and S Takahashi.

We also appreciate the assistance of Drs. Andreas Nebenführ, Krzysztof Bobik, and Stephanie Madison (Department of Biochemistry and Cellular and Molecular Biology (BCMB), The University of Tennessee) in using their fluorescence microscope.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-RR18470 (Peter Mazur, PI).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that would prejudice the impartiality of this scientific work.

References

- Acker JP, Elliot JAW, McGann LE. Intercellular ice propagation: experimental evidence for ice growth through membrane pores. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75794-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcroft LC, Offenberg H, Thomsen P, Watson AJ. Aquaporin proteins in murine trophectoderm mediate transepithelial water movements during cavitation. Developmental Biology. 2003;256:342–354. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria M, Windhager EE, Tate SS, Frindt G. Cloning and expression of AQP3, a water channel from the medullary collecting duct of rat kidney. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:10997–11001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edashige K, Ohta S, Tanaka M, Kuwano T, Valdez DM, Jr, Hara T, Jin B, Takahashi S, Seki S, Koshimoto C, Kasai M. The role of aquaporin-3 in the movement of water and cryoprotectants in mouse morulae. Biology of Reproduction. 2007;77:365–375. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edashige K, Tanaka M, Ichimaru N, Ota S, Yazawa K, Higashino Y, Sakamoto M, Yamaji Y, Kuwano T, Valdez DM, Jr, Kleinhans FW, Kasai M. Channel-dependent permeation of water and glycerol in mouse morulae. Biology of Reproduction. 2006;74:625–632. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edashige K, Yamaji Y, Kleinahns FW, Kasai M. Artificial expression of aquaporin-3 improves the survival of mouse oocytes after cryopreservation. Biology of Reproduction. 2003;68:87–94. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.101.002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimia D, Karlsson JOM. Kinetics and mechanism of intercellular ice propagation in a micropatterned tissue construct. Biophysical Journal. 2002;82:1858–1868. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75536-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai M, Komi JH, Takakamo A, Tsudera H, Sakurai T, Machida T. A simple method for mouse embryo cryopreservation in a low toxicity vitrification solution, without appreciable loss of viability. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1990;89:91–97. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0890091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Kozono D, Agre P. From structure to disease: the evolving tale of aquaporin biology. Nature Reviews Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;5:687–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans FW. Membrane permeability modeling: Kedem-Katchalsky vs a two-parameter formalism. Cryobiology. 1998;37:271–289. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1998.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans FW, Mazur P. Comparison of actual vs. synthesized ternary phase diagrams for solutes of cryobiological interest. Cryobiology. 2007;54:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibo SP. Water permeability and its activaiton energy of fertilized and unfertilized mouse ova. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1980;53:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF01868823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Song Y, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Nepherogenic diabetes insipidus in mice lacking aquaporin-3 water channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science in USA. 2000;97:4386–4391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080499597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey RI. Transport of water and urea in red blood cells. American Journal of Cell Physiology. 1984;246:C195–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.3.C195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganelli CV, Solomon AK. The rate of exchange of tritiated water across the human red cell membrane. The Journal of General Physiology. 1957;41:259–277. doi: 10.1085/jgp.41.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Seki S, Jin B, Valdez DM, Jr, Ohta S, Yoshimura M, Kasai M, Edashige K. The possible role of aquaporin 9 in the movement of cryoprotectants in mouse morulae. Journal of the Reproduction and Development. 2008;54(Supplement):j136. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, Pinn IL, Seki S, Kleinhans FW, Edashige K. Effects of hold time after extracellular ice formation on intracellular freezing of mouse oocytes. Cryobiology. 2005a;51:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, Seki S, Pinn IL, Kleinhans FW, Edashige K. Extra- and intracellular ice formation in mouse oocytes. Cryobiology. 2005b;51:29–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C, Preston GM, Griffin CA, Jabs EW, Agre P. The human aquaporin-CHIP gene, structure, organization, and chromosomal localization. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:15772–15778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro PB, Yokoyama E, Zhu SE, Yoshida N, Valdez DM, Jr, Tanaka M, Edashige K, Kasai M. Permeability of mouse oocytes and embryos at various developmental stages to five cryoprotectants. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2005;51:235–246. doi: 10.1262/jrd.16079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro PB, Zhu SE, Makino N, Sakurai T, Edashige K, Kasai M. Effects of hypotonic stress on the survival of mouse oocytes and embryos at various stages. Cryobiology. 1997;35:150–158. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1997.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez JC, Berthoud VM, Branes MC, Mertinez AD, Beyer EC. Plasma membrane channels formed by connexins: their regulation and functions. Physiological Review. 2003;83:1359–1397. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Mazur P. Effect of warming rate on the survival of vitrified mouse oocytes and on the recrystallization of intracellular ice. Biology of Reproduction. 2008;79:727–737. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Mazur P. The temperature and type of intracellular ice formation in preimplantation mouse embryos as a function of the developmental stage. Biology of Reproduction. 2010a;82:1198–1205. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.083063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Mazur P. Comparison between the temperatures of intracellular ice formation in fresh mouse oocytes and embryos and those previously subjected to a vitrification procedure. Cryobiology. 2010b;61:155–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Kouya T, Hara T, Valdez DM, Jr, Jin B, Kasai M, Edashige K. Exogenous expression of rat aquaporin-3 enhances permeability to water and cryoprotectants of immature oocytes in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2007;53:597–604. doi: 10.1262/jrd.18164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui H, Han BG, Lee JK, Walian P, Jap BK. Structural basis of water-specific transport through the AQP1 water channel. Nature. 2001;414:872–878. doi: 10.1038/414872a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez DM, Jr, Hara T, Miyamoto A, Seki S, Jin B, Kasai M, Edashige K. Expression of aquporin-3 improves the permeability to water and cryoprotectants of immature oocytes in the medaka (Oryzias latipes). Cryobiology. 2006;53:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdimarsson G, Kidder GM. Temporal control of gap junction assembly in preimplantation mouse embryos. Journal of Cell Science. 1995;108:1715–1722. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham DG. Survival of mouse embryos after freezing and thawing. Nature. 1971;233:125–126. doi: 10.1038/233125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AV, Brown MG, Prentiss PG. Concentration properties of aqueous solutions: Conversion tables. In: Weast RC, editor. Handbook of Cehmistry and Physics. edn 51st Chemical Rubber Co.; Cleaveland: 1970. pp. D181–D226. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji Y, Valdez DM, Jr, Seki S, Yazawa K, Urakawa C, Jin B, Kasai M, Kleinhans FW, Edashige K. Cryoprotectant permeability of aquaporin-3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Cryobiology. 2006;53:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T, Klaerke DA. Transport of water and glycerol in aquaporin 3 is gated by H (+). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:21631–21636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SE, Kasai M, Otoge H, Sakurai T, Machida T. Cryopreservation of expanded mouse blastocysts by vitrification in ethylene glycol-based solutions. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1993;98:139–145. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0980139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]