Abstract

The regulation of cardiac differentiation is complex and incompletely understood. Recent studies have documented that Nkx2-5-positive cells are not limited to the cardiac lineage, but can give rise to endothelial and smooth muscle lineages. Other work has elucidated that, in addition to promoting cardiac development, Nkx2-5 plays a larger role in mesodermal patterning although the transcriptional networks that govern this developmental patterning are undefined. By profiling early Nkx2-5-positive progenitor cells, we discovered that the progenitor pools of the bisected cardiac crescent are differentiating asynchronously. This asymmetry requires Nkx2-5 as it is lost in the Nkx2-5 mutant. Surprisingly, the posterior Hox genes Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 were expressed on the right side of the cardiac crescent, independently of Nkx2-5. We describe a novel, transient, and asymmetric cardiac-specific expression pattern of the posterior Hox genes, Hoxa9 and Hoxa10, and utilize the embryonic stem cell/embryoid body (ES/EB) model system to illustrate that Hoxa10 impairs cardiac differentiation. We suggest a model whereby Hoxa10 cooperates with Nkx2-5 to regulate the timing of cardiac mesoderm differentiation.

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects approximately 1% of live births and accounts for the largest incidence of death due to of birth defects in the first year of life [1,2]. Although numerous studies have defined the anatomical defects associated with CHD, the molecular networks that underpin these perturbations are incompletely defined [3,4]. Studies utilizing genetically modified mouse models have demonstrated the essential roles of transcription factors and signaling molecules at discrete stages of heart development [4–6]. Nkx2-5 is one of the earliest markers of the cardiac lineage as it is abundantly expressed in the cardiac progenitor cells that form the cardiac crescent (E7.75) [7,8]. Nkx2-5 is expressed throughout cardiac development and persists in the adult myocardium. Embryos lacking Nkx2-5 are nonviable (E9.5-E10.5) due to growth retardation and gross abnormalities of the heart, including a failure of the ventricular chamber development [7,8]. Several recent studies have demonstrated that early Nkx2-5 expressing progenitor cells are multipotent giving rise to cardiomyocyte, smooth muscle, and endothelial lineages [9,10] and likewise, Nkx2-5 knockout embryos have significant defects in these lineages [7,8,11]. These findings support the notion that Nkx2-5 plays a larger role in mesodermal patterning and the early Nkx2-5 expressing cells in the cardiac crescent may not yet be restricted exclusively to the cardiac lineage.

The Hox family of transcription factors is critical for early anterior–posterior (A-P) patterning of developing embryos and also regulates proliferation, differentiation, and migration of multiple cell types [12,13]. Human and murine HOX genes are arranged in four clusters (A-D) and are positioned within each cluster in a 5′-3′ fashion in the order in which they are expressed. The anterior groups, Hox 1–8, are homologous with the Drosophila antennapedia group (including Abd-A), while the Abd-B homologs consist of the posterior groups, Hox 9–13 [14]. Studies in the hematopoietic system have identified that several Hox genes, including Hoxa9 and Hoxa10, are expressed in the most primitive hematopoietic cells [15,16]. Enforced expression of Hoxa10 has been shown to block differentiation and increase the number of early hematopoietic progenitors [16] and retroviral overexpression of Hoxa10 not only dramatically impaired myeloid and lymphoid differentiation, but resulted in the development of acute myeloid leukemia in a significant percentage of these mice [15]. The role of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 in the development of the reproductive track has been well described. Hoxa10 is abundantly expressed in the urogenital system of both female and male mice [17]. Female mice with a targeted mutation of Hoxa10 demonstrate urogenital deformities [18], and are sterile because of the absence of Hoxa-10 expression in the adult uterus. Hoxa10 mutant males display unilateral or bilateral cryptorchidism [17], which results in abnormal spermatogenesis and increasing sterility with age [17,19]. Although Hox genes typically were considered to be expressed only during the embryonic development, the continued Hoxa10 gene expression in the adult has been described in tissues with high plasticity such as bone marrow and endometrium [16,20]. In the reproductive tract, the posterior Hox genes responsible for patterning the developing embryonic genitourinary tract are also responsible for remodeling the adult genitourinary tract as illustrated by the essential role of Hoxa10 in the continuing developmental process of the female reproductive tract with each menstrual cycle and pregnancy [20]. Persistent Hox gene expression in the adult has been proposed as a mechanism by which the reproductive tract retains developmental plasticity [21].

The role of Hox genes in the cardiac lineage is less clear. Early studies in Drosophila noted a role for the Hox gene, abd-A, in cardiac tube development. The cardiac tube in flies consists of two regions, the anterior aorta and the posterior heart that contains contracting myocytes. In animals lacking abd-A, the heart myocytes failed to differentiate and mature appropriately, instead adopting an aorta-like phenotype [22,23]. Ectopic expression of abd-A, however, was sufficient to transform aortic myocytes into more posterior heart-like myocytes. Conversely, studies of abd-B (homolog of murine Hox 9–13) revealed that pan-mesodermal overexpression completely suppressed cardiogenesis, while abd-B loss-of-function mutants displayed formation of additional posterior myocardial cells [23,24]. Several anterior Hox genes have been implicated in mammalian cardiovascular development. A recent study identified severe cardiovascular defects in patients harboring a homozygous truncating mutation in HOXA1 [25], however, cardiovascular abnormalities were not identified in initial Hoxa1 knockout mice models [26]. Given the newly described human mutation, more careful analysis revealed that almost three quarters of Hoxa1 null mice had a cardiovascular defect [26]. Additional characterization of these mutant animals determined that Hoxa1 is expressed in cardiac neural crest cells and is required for neural crest specification [26,27]. Hoxa3 expression has also recently been shown in cardiac neural crest cells and secondary heart field-derived outflow tract myocardium; this expression is greatly enhanced with retinoic acid treatment [28]. The critical role of Hox genes in the A-P patterning of the developing embryo has been well described [29–32]. A spatial and temporal colinearity of Hox gene expression has been observed in the primitive streak and lateral mesoderm during the critical stages of early heart formation. Retinoic acid administration results in changes in patterning and expression of the Hox genes in chick limb buds and rat lung buds [33,34]. Similar RA-induced changes in A-P patterning of the primitive heart tube were observed in chick cardiogenic-treated tissue [35,36]. These studies have led to the hypothesis that Hox genes are involved in early A-P patterning of the developing heart.

In the present study, we demonstrate that the Nkx2-5 expressing progenitor cells of the cardiac crescent have an asymmetric gene expression profile. The asymmetry involves accelerated differentiation of left-sided progenitors (earlier expression of cardiomyocyte terminal markers on the left side), while the right side appears slower to differentiate maintaining higher expression of the early mesodermal marker Brachyury and the posterior Hox genes, Hoxa9 and Hoxa10. Surprisingly, we find that the asymmetric expression of many transcripts requires functional Nkx2-5. We describe a novel, transient, early cardiac-specific expression pattern of the posterior Hox genes, Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 and utilize the embryonic stem cell/embryoid body (ES/EB) model system to illustrate that Hoxa10 impairs cardiac differentiation. We also suggest a model whereby Hoxa10 interacts with Nkx2-5 to regulate the timing of cardiac mesoderm differentiation. Collectively, these studies enhance our understanding of molecular networks that govern the discrete stages of early cardiac development.

Methods

FACS, transcriptome analyses

We utilized previously generated Nkx2-5-promoter-EYFP transgenic and Nkx2-5 null mouse models [8,37] and isolated cardiac progenitors from the bisected E7.75 cardiac crescent following 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) digestion and FACS analysis [8,37]. Using a MoFlo Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter), EYFP-labeled cells were collected directly into Tripure (Roche) and RNA was extracted and amplified as previously described [37]. Oligonucleotide array hybridizations were carried out according to the Affymetrix protocol as previously described [37,38]. cDNA synthesis and quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed as previously described [38]. Expression was analyzed in triplicate by qRT-PCR using FAM-labeled TaqMan probes from Applied Biosystems: Gapdh (Mn99999915_g1), Tdgf1 (Mm01605855_g1), Tnni (Mm00441922_m1), Kdr (Mm00440099_m1), Hoxa1 (Mm00439359_m1), Hoxa2 (Mm00439361_m1), Hoxa3 (Mm01326402_m1), Hoxa4 (Mm01335255_m1), Hoxa5 (Mm00439362_m1), Hoxa6 (Mm00550244_m1), Hoxa7 (Mm00657963_m1), Hoxa9 (Mm00439364_m1), Hoxa10 (Mm00433966_m1), Hoxa11 (Mm00439360_m1), and Hoxa13 (Mm00433967_m1) probes.

Analysis of Hoxa10 developmental expression pattern

Embryos were harvested and hearts isolated at designated developmental time points. In addition, at E8.25 (5–7 somite pairs), the heart tubes were isolated and the remaining embryos were divided into anterior segments minus the heart and posterior segments. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR reactions were performed as previously described [38]. Expression was analyzed in triplicate by qRT-PCR using FAM-labeled TaqMan probes from Applied Biosystems: Gapdh (Mn99999915_g1), Hoxa9 (Mm00439364_m1), and Hoxa10 (Mm00433966_m1) probes.

Generation of an inducible ES/EB system for Hoxa10 overexpression

Doxycycline-inducible expression of Hoxa10 in A2Lox mES cells was generated as previously described [39]. A2Lox cre mES cells lacking inserted Hoxa10 plus doxycycline and Hoxa10-A2Lox mES cells without doxycycline were used as controls. The previously described reporter Nkx2-5 emGFP ES cell line [40–42] was infected with pSAM2-Hoxa10-mCherry or empty lentivirus along with pLenti-RtTA as previously described [43]. In brief, HA-Hoxa10 cDNA was cloned into pSAM2-IRES-mCherry [43], a lentiviral construct with a doxycycline inducible promoter and the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) sequence followed by mCherry at the 3’ end. Viral particles were prepared and cells were infected as previously described [43]. Infected cells were enriched by doxycycline induction followed by FACS for mCherry-positive cells. During the last enrichment, cells were sorted by FACS for mCherry and SSEA1-APC (eBiosciences 51-8813-71) expression to enrich for virally integrated, undifferentiated ES cells. Expression was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of mCherry, qRT-PCR using FAM-labeled Gapdh (Mn99999915_g1) and Hoxa10 (Mm00433966_m1) TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) and western blot using the following antibodies: goat-anti-Hoxa10 serum (1:200, Santa Cruz, Sc17158) and mouse-anti-α-tubulin serum (1:5000, Sigma T5168).

EB differentiation

ES cells were preplated for 30 min on gelatin-coated flasks to remove the mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Cells were resuspended at a concentration of 10,000 cells/mL in the mouse EB differentiation medium (IMDM, 15% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamax, 1 × penicillin and streptomycin, 450 μM 1-thioglycerol (MTG), 200 μg/mL holo-transferrin, and 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid). About 10 μL hanging drops were plated and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 to induce differentiation. After 48 h (at EB D2), the hanging drops were washed from plates and further incubated in Petri dishes on a rotating platform (70 rpm) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were fed with a fresh medium with or without doxycycline every 48 h, as previously described [44]. A2Lox cre mES cells lacking inserted Hoxa10 plus doxycycline and Hoxa10-A2Lox mES cells without doxycycline were used as controls. Gene expression was analyzed using qRT-PCR or western blot analysis as previously described [39] using the following antibodies: goat-anti-Hoxa10 serum (1:200; Santa Cruz, Sc17158), rabbit-anti-cardiac Troponin I serum (1:3000; Abcam, ab47003), mouse-anti-cardiac Troponin T serum (1:3000; Abcam, ab8295), rabbit-anti-Conexin 43 serum (1:6000; Abcam, ab11370), and mouse-anti-α-tubulin serum (1:5000; Sigma, T5168). Day 4 EBs were dissociated, cells were incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark with Flk-1-PE (eBiosciences 12-5821-83) and PDGFRα-APC (eBiosciences 17-1404-81). The Flk-1-PE, PDGFRα-APC double-positive cardiac progenitors were quantified by FACS analysis on a BD FACS Aria [10,45,46]. Nkx2-5 expressing cells were collected from day 4 EBs following 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) digestion and FACS analysis. qRT-PCR was performed as previously described [38]. Expression was analyzed in triplicate by qRT-PCR using FAM-labeled TaqMan probes from Applied Biosystems: Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Brachyury (Mm00436877_m1), Nkx2-5 (Mm00657783_m1), Gata4 (Mm00484689_m1), Isl1 (Mm00517585_m1), Tbx5 (Mm00803518_m1), Aldh1a2 (Mm00501306_m1), and Hes1 (Mm01342805_m1) probes.

Transcriptional assays

Luciferase assays were performed as previously described [38]. Briefly, the 825bp Nppa promoter region containing Nkx2-5- and Gata4-binding sites was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pGL3 vector to construct the Nppa-luc reporter using the following primers: forward: 5′-GGACACGAGTCTTGGGAGGC-3′ and reverse: 5′-GGGCACGATCTGATGTTTGC-3′. The 4219bp Nkx2-5 promoter region containing Nkx2-5- and Gata4-binding sites was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pGL3 vector to construct the Nkx2-5-luc reporter using the following primers: forward: 5′- AGGTTCTCTTTGGCAGCAGGCATCTT-3′ and reverse: 5′- GGGTTTCTTGGCTCAGGGTTTTGGAC-3′. COS7 cells were cultured in the HyClone Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, High Glucose (ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10%. The cells were transfected with control (pGL3-Luc), pNkx2-5-Luc, or pNppa-Luc constructs with or without Nkx2-5, Gata4, and Hoxa10 overexpression plasmids ensuring equal amounts of total DNA [38]. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection and the luciferase activity was analyzed with the Dual Luciferase System (Promega) and normalized with the Renilla luciferase. Transfections were done in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All P-values were calculated using the Student's t-test analysis.

Results and Discussion

Molecular asymmetry in the cardiac crescent

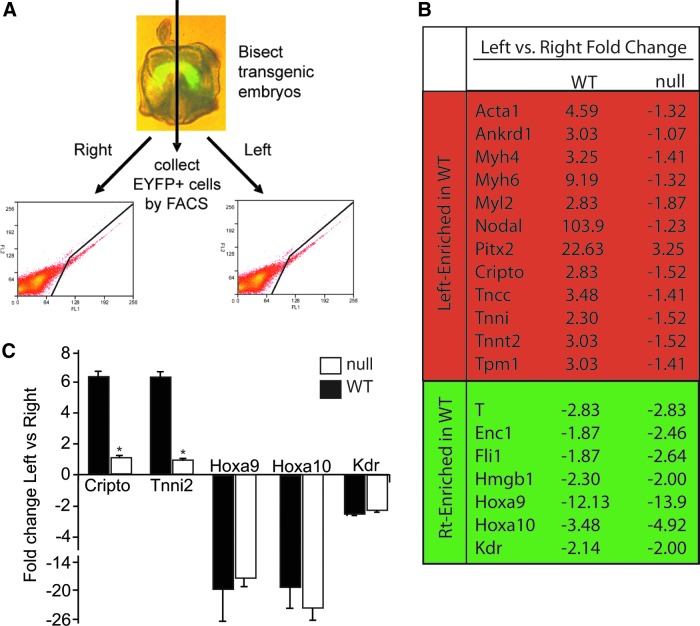

We have previously employed an Nkx2-5-EYFP transgenic mouse model to identify the transcriptome of cardiac progenitor cells [37]. We identified transcripts that were enriched in progenitor cell populations throughout all stages. As expected, these included cardiac transcriptional regulators (Nkx2.5, GATA4, HOP, Mef2C, and myocardin) and myocardial structural genes (Myl4, Myl7, Tncc, Tnni1, and Tnnt2). We also noted that, compared to adult cardiomyocytes, the cardiac progenitor cell transcriptome consisted of an induction of the vascular, endocardial, and signaling proteins, emphasizing the important role of these factors in fate determination, proliferation, patterning, and cardiogenesis [37]. Several recent studies have expanded this finding, demonstrating that early Nkx2-5 expressing progenitor cells are multipotent giving rise to not only cardiomyocytes, but also smooth muscle and endothelial lineages [9,10]. Utilizing this same Nkx2-5-EYFP transgenic mouse model and the Affymetrix array technology, we examined the gene expression signature of cardiac progenitors that populated the left versus the right regions of the cardiac crescent of single embryos. We bisected the cardiac crescent (E7.75) and collected the EYFP-positive cardiac progenitors from the left and right crescent of individual developing embryos using FACS analysis (Fig. 1A). Cell counts demonstrated that the number of EYFP-labeled cells collected from the left (mean=2044, SD=499, n=5) and the right (mean 2263, SD 294, n=5) sides of the crescent were comparable. Overall, the molecular signatures of each side of the crescent were largely similar with only 70 transcripts being significantly differentially regulated in both of the tandem array results (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd). Forty-seven transcripts were enriched on the left side of the crescent versus 23 transcripts showing right-sided enrichment. Elegant studies have defined the role of Nodal and its interaction with Cripto to initiate the left-right asymmetric program by regulating downstream effectors [47]. In crescent stage embryos, their expression is known to be restricted to the left side of the embryo [48] and accordingly, we observed left-sided enrichment of Nodal, Cripto, and Pitx2. However, it was striking to note that the majority of the genes enriched on the left-sided cardiac crescent were myogenic genes such as Myl4, Myh6, Tncc, Tnnt2, and Tpm1. There were also genes associated with the differentiated endothelium (Fus and VCAM) and smooth muscle (Apeg1 and Dia7). These findings suggested that the left-sided program was enriched in transcripts associated with cardiovascular differentiation. The right side of the crescent, in contrast, was not enriched in genes for any specific tissue program, but appeared to represent a more undifferentiated mesoderm as illustrated by the enriched expression of Brachyury. These findings suggest that cardiovascular differentiation initiates asymmetrically on the left side of the crescent similar to the initiation of asymmetric genes expression on the left side of the node [49].

FIG. 1.

Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 are expressed in early cardiac progenitor cells of the cardiac crescent. (A) Individual WT and Nkx2-5 null cardiac crescent stage embryos were bisected and EYFP-positive cells were collected from the right and left side of the crescent. Left WT mean=2044, SD=499, n=5; left null mean=1967, SD=200, n=4; right WT mean=2263, SD=294, n=5; right null mean=2167, SD=252, n=4. (B) Transcriptome analysis of the WT and Nkx2-5 null left versus right side of the crescent. Note a significant induction of cardiac structural transcripts in the left versus right WT crescent. This left-sided enrichment is absent in the Nkx2-5 null crescent. The right-sided enrichment in expression is largely unaltered in the absence of Nkx2-5. Significant differential transcript expression is denoted by a green highlight (upregulated) or a red highlight (downregulated). (C) quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of selected trannscripts in WT (black bar) and null (open bar) right and left crescent.

As discussed above, recent studies have described the role of anterior Hox genes in mammalian cardiovascular development [26–28]. Our array studies confirmed the expression of several anterior Hox genes in the early Nkx2-5 expressing cardiovascular progenitors (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Unexpectedly, we detected the expression of posterior Hox genes within the cardiac crescent. The array findings also suggested a right-sided enrichment of the Hox genes within the cardiac crescent. qRT-PCR analysis of the Hox A family (family of Hox transcripts most frequently expressed in the array) confirmed the expression of the posterior Hox genes in EYFP-positive cardiac progenitors from the left and right crescent of an additional embryo (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 were enriched on the right side of the crescent both by array and qRT-PCR and this data suggested that these posterior Hox genes may play a role in cardiovascular development. In mammals, expression of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10, first seen by in situ hybridization at the posterior limb bud stage, appeared to respect an anterior border posterior to the heart and were therefore previously not thought to be expressed in the developing heart [50]. The anterior expression border for Hoxa9 had been described as 4–5 segments anterior to the hindlimb or at the last thoracic vertebra [50]. The last lumbar vertebra or the first sacral vertebra has been noted to be the most anterior expression level for Hoxa10 [50]. We believe that this is the first description of a cardiac expression pattern for Hoxa9 and Hoxa10. Although left-sided enrichment of XHoxc-8 has been described in the posterior lateral plate mesoderm in the tail bud stage Xenopus embryos [51], there also has been no prior report of left-right asymmetric expression patterns of mammalian Hox genes.

Early asymmetric gene expression in the cardiac crescent is Nkx2.5 dependent

To further investigate the significance of this early asymmetric transcriptional program, we analyzed the same left-right transcriptional program in the Nkx2-5 null cardiac crescent. We crossed the Nkx2-5-EYFP transgenic embryo into the Nkx2-5 null background. As described previously, we bisected the crescent stage embryos and utilized FACS to isolate the respective cell populations (Fig. 1A). No significant differences were observed in the number of EYFP-positive cells recovered from the Nkx2-5 null cardiac crescents compared to the wild-type crescents (Fig. 1A). The transcriptome of the Nkx2-5 null crescent cells, however, was markedly different compared to the WT pattern (Fig. 1B). The array results were confirmed using qRT-PCR for selected transcripts (Fig. 1C). While the WT transcriptome was dominated by myogenic genes displaying left-sided enrichment, the Nkx2-5 null crescent only displayed two transcripts with left-sided enrichment (Supplementary Table S2). While Lefty2 maintained its expected asymmetric expression, the level of left-sided enrichment of Pitx was decreased when compared to WT. Even more striking was that the expression of both Nodal and Tdgf1 was largely equalized in the Nkx2-5 null crescent. Previous studies have demonstrated that Nodal initiates and directly induces Pitx2c expression, but Nkx2-5 is important in the maintenance of Pitx2 expression at later stages of development in the absence of Nodal signaling [52]. Our findings suggest that the role of Nkx2-5 in maintaining the L-R asymmetric gene expression begins very early in cardiovascular development. Prior studies suggest a number of early patterning defects in the Nkx2-5 null embryos—growth retardation, incomplete ventricular trabeculation, absence of the interventricular conduction ring, incomplete definition of the right and left ventricles, and a failure to form endocardial cushions [7,8]. These anatomical perturbations were accompanied by decreased expression of Myl2, Hand1, and Nppa in the Nkx2-5 null ventricle compared to the WT control [7]. In our current study, Nkx2-5 null crescents exhibited a loss of the left-sided enrichment for cardiac transcripts enriched on the left side of the WT crescent. Nkx2-5 has been shown to transcriptionally activate a number of genes important in cardiac differentiation [53,54]. The result of the lack of this gene induction is highlighted in the Nkx2-5 null embryos as they display defective development of the ventricles of the heart. The disruption of this program in the null crescent further supports the notion that Nkx2-5 regulates the fate determination of future cardiovascular lineages in the earliest specified multipotent cardiac progenitors. While the pattern of left-sided transcript enrichment was significantly altered in the null transcriptome, many right-side enriched transcripts, including T, Fli, and the newly identified cardiac expression of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10, retained the patterns they exhibited in the WT crescent suggesting their regulation was independent of Nkx2-5. Given the apparent lack of differentiation on the right side of the crescent, the recently discovered importance of the anterior Hox genes, Hoxa1 and Hoxa3, in cardiac development and the prior described role of Hoxa10 in inhibiting hematopoietic differentiation we investigated whether the posterior Hox genes, Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 could be important in cardiovascular differentiation.

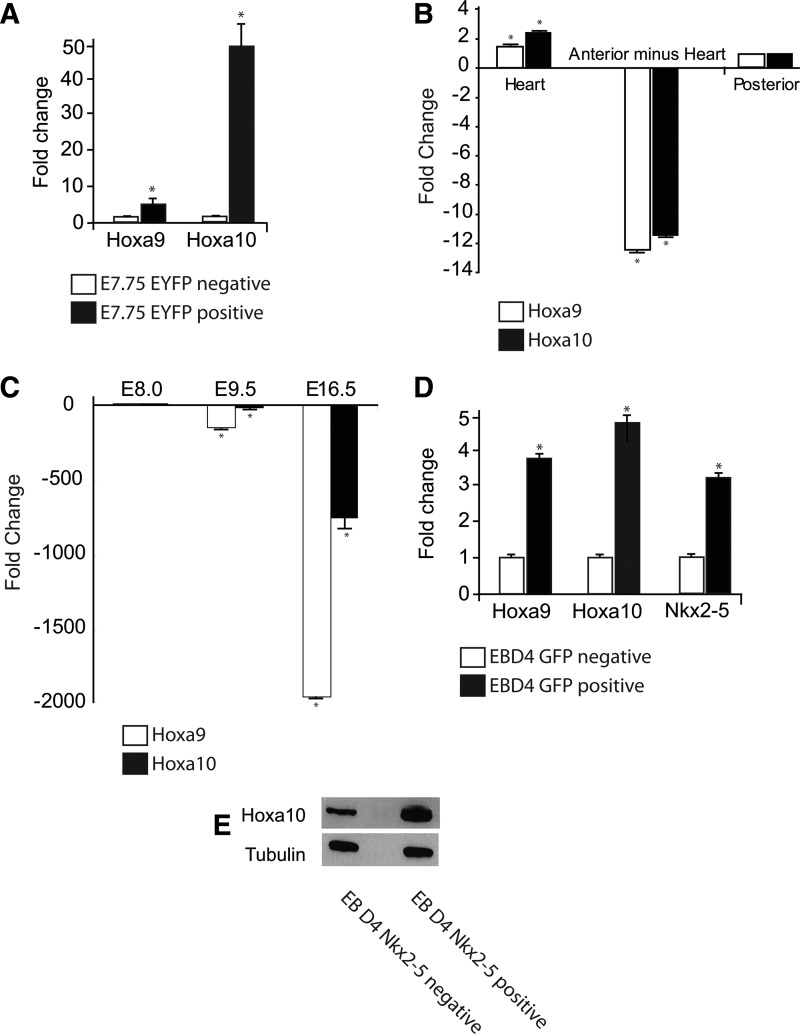

Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 are expressed in the early developing heart

Because Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 are broadly expressed throughout the neuroectoderm and have previously been only noted to be expressed in the mesoderm posterior to the thoracic vertebrae [50], we carefully confirmed this novel, putative anterior expression domain. The maintained asymmetrical expression of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 in the Nkx2-5 null crescent stage embryos suggests that the regulation of posterior Hox genes in mesodermal patterning is independent of Nkx2-5. Using qRT-PCR, we found that Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 were not only expressed in the E7.75 EYFP-positive cardiac progenitors, but enriched when compared to the EYFP-negative cells harvested from the whole embryo (Fig. 2A). Division of E8.25 (5–7 somite pair) embryos into the isolated heart tube, the anterior embryo minus the heart, and the posterior embryo also revealed continued enrichment of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 in the heart (Fig. 2B). The cardiac progenitor-specific expression of both Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 was noted to be transient as expression decreased rapidly as the cardiac development proceeded (Fig. 2C). Expression of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 in early GFP-positive, Nkx2-5 expressing cardiac progenitors isolated from crescent equivalent day 4 EBs generated from the Nkx2-5 emGFP reporter ES cell line was confirmed on both the transcript and protein levels (Fig. 2D, E).

FIG. 2.

Characterization of cardiac Hoxa10 expression. (A) Analyses of enrichment of Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 in the EYFP-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells versus EYFP-negative cells collected from the cardiac crescent using qRT-PCR; *P<0.05, n=3. (B) qRT-PCR reveals Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 are enriched in the E8.25 (5–7 somite) heart compared to the remaining segments of the embryo; *P<0.05, n=3. (C) Cardiac Hoxa9 and Hoxa10 expression is rapidly downregulated during cardiac development as assessed by qRT-PCR; *P<0.05, n=3. (D) Analyses of fold change in the expression of the Hoxa9, Hoxa10, and Nkx2-5 from GFP-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells versus GFP negative obtained from embryoid bodies (EBs) harvested at day 4 using qRT-PCR; *P<0.05, n=3. (E) Western analysis of EB day 4 GFP-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells confirm Hoxa10 protein expression.

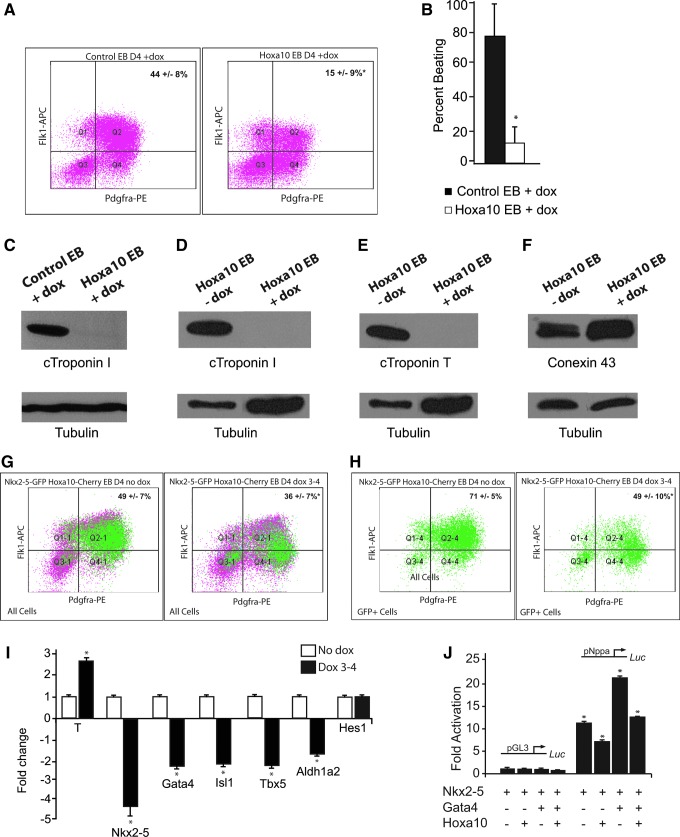

Hoxa10 inhibits cardiac differentiation in cell culture and embryoid bodies

Previous studies have clearly demonstrated that Hoxa10 plays an important role in regulating hematopoietic differentiation, including the ability of Hoxa10 to impair differentiation of mesodermally derived progenitor cells following specification [15,16]. No role for Hoxa10 in cardiovascular mesodermal differentiation in a mammalian system has yet been described. To further examine our hypothesis that Hoxa10 played a role in early cardiovascular development, we complemented our in vivo studies utilizing the Nkx2-5-EYFP transgenic embryos with the generation of a doxycycline-inducible Hoxa10 overexpressing ES cell line. Our strategy is schematized in Supplementary Fig. S2 and highlights that the reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA) binds to the tetracycline responsive element to induce Hoxa10 expression only after the addition of doxycycline. The day 4 EB cardiac progenitor population was significantly reduced in the Hoxa10 overexpressing EBs compared to control EBs (Fig. 3A; 15%±9% vs. 44%±8%, n=8, P<0.05). Assays also revealed a significant decrease in the percentage of beating embryoid bodies at EB day 8 in the Hoxa10 overexpressing EBs compared to control EBs (Fig. 3B; 13%±10% vs. 78%±22%, n=8, P<0.05). The protein harvested from day 12 EBs revealed an absence of cardiac troponin I in the Hoxa10 overexpressing EBs compared to doxycycline-treated control EBs (Fig. 3C). This control confirmed that the decrease of beating and lack troponin expression was not simply a doxycycline effect. The protein harvested from Hoxa10 day 12 EBs without doxycycline confirmed that without induction of Hoxa10, EBs generated from the doxycycline-inducible Hoxa10 cell line were able to differentiate into cardiomyocytes as evidenced by the robust expression of cardiac troponin I and cardiac troponin T (Fig. 3D, E). However, induction of Hoxa10 overexpression again resulted in an absence of cardiac troponin I and cardiac troponin T (Fig. 3D, E). Preserved expression of conexin 43 in the Hoxa10 day 12 EB protein samples supported that the lack of beating was not due to a defect in excitation or contraction coupling, but rather a perturbation of cardiomyocyte differentiation as evidenced by the lack of cardiac structural proteins. The alteration in cardiogenesis did not appear to be a general posterior Hox gene effect as Hoxa13 had a much lower effect on the percentage of Flk-1 and PDGFRα double-positive cardiac progenitor cells (30.5%±1.4% vs. 40%±6.7%, n=4, P<0.05) and no significant reduction in beating EBs (77%±27% vs. 62%±32%, n=4, P=0.5) compared to control EBs.

FIG. 3.

Hoxa10 inhibits cardiogenesis. (A) Percentage of EB day 4, Flk-1-PDGFRα double-positive cardiac progenitor cells are significantly decreased following Hoxa10 overexpression for 48 h (day 2–4) of EB formation; 15%±9% versus 43.6%±7.9%, *P<0.05, n=8. (B) Reduction of beating in EBs overexpressing Hoxa10 following induction with doxycycline (Dox) on days 3–6 versus control EBs plus doycycline; 12.5±10.3 versus 78.4±21.7, *P<0.05, n=8. (C) Western analysis reveals absence of cTroponin I in day 12 EBs overexpressing Hoxa10 following the induction with doxycycline (Dox) on days 3–6 versus day 12 control EBs treated with doxycycline (Dox) on days 3–6). Western analysis reveals absence of cTroponin I (D) and cTroponin T (E) in day 12 Hoxa10 doxycycline-inducible EBs following the induction with doxycycline (Dox) on days 3–6 versus no doxycycline. (F) Protein expression of Connexin 43 is preserved in day 12 EBs following Hoxa10 induction. (G) The Nkx2-5-GFP reporter ES cell line was infected with Hoxa10 or empty lentivirus. Overexpression of Hoxa10 for 24 h (day 3–4 of EB formation) in cardiac crescent equivalent progenitors results in a reduction of total Flk-1/PDGFRα double-positive cardiac progenitor cells; 35.5%±7% versus 48.6%±7%; *P<0.05, n=5. (H) Percentage of Nkx2-5 expressing GFP-positive cells double-positive for Flk-1 and PDGFRα is also significantly decreased with Hoxa10 overexpression; 49%±10% versus 71%±5%; *P<0.05, n=5. (I) qRT-PCR analyses revealed an increase in Brachyury expression and reduction in the cardiac transcription factors Nkx2-5, Gata-4, Tbx-5, and Isl-1 as well as a small decrease in Aldh1a2 in GFP-positive cells collected from day 4 Nkx2-5-GFP EBs following the induction of Hoxa10 with doxycycline (Dox) for 24 h (day 3–4); *P<0.05, n=3. Hes1 expression, however, was not significantly altered. (J) The Nppa promoter was fused to the luciferase (luc) reporter gene and was transfected into Cos7 cells with and without addition of the Nkx2-5, Gata4, or Hoxa10 expression plasmids. Empty pGL3 and Nppa promoter-driven luciferase expression is shown. Nppa promoter revealed a 10.65±0.44-fold activation with Nkx2-5, which was reduced to 7.41±0.50 with addition of Hoxa10 and a 20.55±0.49-fold activation with Nkx2-5 and Gata4, which was reduced to 12.62±0.17 with the addition of Hoxa10; *P<0.05, n=3.

Our initial studies in the Hoxa10 overexpressing EBs suggest that early Hoxa10 misexpression restricts the specification of cells to a cardiac lineage and also impairs the differentiation of early progenitor cells into differentiated, contractile cardiomyocytes. To further address the role of Hoxa10 on the Nkx2-5 expressing early progenitors of the cardiac crescent, we utilized the Nkx2-5 emb-GFP-Hoxa10-mCherry pSAM2 ES cell line in which the lentiviral-mediated Hoxa10 expression is induced with the addition of doxycycline in ES cells harboring an Nkx2-5-emGFP reporter. Using these engineered ES cells, Hoxa10 expression was induced from EB day 3–4 to correlate with increased Hoxa10 expression at the E7.75 (cardiac crescent) developmental time point. The total percentage of cardiac progenitor cells was again significantly reduced in the Hoxa10 overexpressing cells (Fig. 3G; 49%±7% vs. 36%±7%, n=5, P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the total percentage of GFP-positive, Nkx2-5 expressing cells in the Hoxa10 overexpressing cells versus uninduced cells (24%±8% vs. 30%±9%, n=5, P>0.05). Further analysis of these GFP-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells revealed a significant change in the characteristics of this population. In the uninduced sample, 71%±5% of the GFP-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells were double-positive for Flk-1 and PDGFRα, thus mostly representing cardiac progenitor cells (Fig. 3H). However, when Hoxa10 was overexpressed, the percentage of Flk-1 and PDGFRα double-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells was significantly reduced (49%±10%, n=5, P<0.05; Fig. 3H). qRT-PCR analysis of these GFP-positive, Nkx2-5 expressing cells collected at EB day 4 confirmed increased Brachyury expression and revealed a reduction in expression of the cardiac transcription factors Nkx2-5, Gata-4, Tbx-5, and Isl-1 as well as a small decrease in Aldh1a2 with overexpression of Hoxa10; Hes1 expression, however, was not significantly altered (Fig. 3I). Thus, early transient overexpression of Hoxa10 does not appear to reduce the percentage of the initial Nkx2-5 cardiovascular progenitors. The overexpression of Hoxa10 does, however, appear to impair the differentiation of these Nkx2-5 expressing cells to a more cardiac-restricted phenotype as illustrated by their reduced percentage of Flk-1/PDGFRα double-positive cardiac progenitors from day 4 EBs. Increased Brachyury expression and reduced expression of the cardiac transcription factors from these GFP-positive Nkx2-5 expressing cells following Hoxa10 overexpression further supports this hypothesis. We theorize that these cells most likely parallel the less differentiated Hoxa10 expressing cells of the right side of the cardiac crescent.

Hoxa10 interacts with Nkx2-5

The final set of studies was focused on defining the mechanism through which Hoxa10 perturbed early cardiogenesis. The Hox protein family has been previously shown to interact with homeodomain proteins, including Pbx and Meis family members [55]. Hox genes have the ability to act as both transcriptional activators and repressors [56] and recent work has suggested that these effects may be mediated through sequestering other proteins [57]. Given that the expression of several cardiac transcription factors in the EB-derived early cardiac progenitors was significantly decreased with Hoxa10 overexpression, and Nkx2-5 in combination with Gata4 is known to cooperatively transactivate the promoters of several genes important in cardiogenesis [53,54,58], we questioned if Hoxa10 was acting as a cardiac transcriptional repressor. Transcriptional assays confirmed that the addition of Hoxa10 decreased the Nkx2-5-Gata4-mediated activation of the both the Nkx2-5 and Nppa promoter (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Fig. 3J). This finding suggested a mechanism in which Hoxa10 may be more broadly regulating cardiogenesis as Nkx2-5 and Gata4 are known to function as mutual cofactors for a number of genes important in cardiac development [53,54,58]. This further supports that Hoxa10 plays an important role in specification and differentiation of the early cardiac progenitors.

Collectively, these data support a model whereby cardiac differentiation occurs in a left to right temporal wave across the Nkx2-5 expressing cells of the cardiac crescent. Continued expression of Hoxa10 impedes cardiac differentiation of the Nkx2-5-positive early cardiac progenitor cells in the EB system. This is the first study that examines the asymmetric molecular program of the cardiac crescent and is the first to describe the expression and functional role of Hoxa10 during early cardiac development. Definition of these transcriptional networks in cardiac progenitor cells will enhance our understanding of mesodermal patterning and cardiac differentiation during normal and perturbed cardiac development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhaohui Xu for his assistance with the pSAM2 lentiviral system generation. We also thank Alessandro Magli, Teresa Gallardo, and Amanda Massino for critical discussions and technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K08 HL102157 and U01 HL100407) and the American Heart Association (Jon Holden DeHaan Foundation 0970499).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Hoffman JI. Incidence of congenital heart disease: II. Prenatal incidence. Pediatr Cardiol. 1995;16:155–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00794186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson EN. Srivastava D. Molecular pathways controlling heart development. Science. 1996;272:671–676. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey RP. Patterning the vertebrate heart. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:544–556. doi: 10.1038/nrg843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson EN. Schneider MD. Sizing up the heart: development redux in disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1937–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand T. Heart development: molecular insights into cardiac specification and early morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;258:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans SM. Yelon D. Conlon FL. Kirby ML. Myocardial lineage development. Circ Res. 2010;107:1428–1444. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka M. Chen Z. Bartunkova S. Yamasaki N. Izumo S. The cardiac homeobox gene Csx/Nkx2.5 lies genetically upstream of multiple genes essential for heart development. Development. 1999;126:1269–1280. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons I. Parsons LM. Hartley L. Li R. Andrews JE. Robb L. Harvey RP. Myogenic and morphogenetic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene Nkx2-5. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1654–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christoforou N. Miller RA. Hill CM. Jie CC. McCallion AS. Gearhart JD. Mouse ES cell-derived cardiac precursor cells are multipotent and facilitate identification of novel cardiac genes. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:894–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI33942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondue A. Tannler S. Chiapparo G. Chabab S. Ramialison M. Paulissen C. Beck B. Harvey R. Blanpain C. Defining the earliest step of cardiovascular progenitor specification during embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:751–765. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caprioli A. Koyano-Nakagawa N. Iacovino M. Shi X. Ferdous A. Harvey RP. Olson EN. Kyba M. Garry DJ. Nkx2-5 represses Gata1 gene expression and modulates the cellular fate of cardiac progenitors during embryogenesis. Circulation. 2011;123:1633–1641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams MD. Celniker SE. Holt RA. Evans CA. Gocayne JD. Amanatides PG. Scherer SE. Li PW. Hoskins RA, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller DF. Holtzman SL. Kalkbrenner A. Kaufman TC. Homeotic Complex (Hox) gene regulation and homeosis in the mesoderm of the Drosophila melanogaster embryo: the roles of signal transduction and cell autonomous regulation. Mech Dev. 2001;102:17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah CA. Wang H. Bei L. Platanias LC. Eklund EA. HoxA10 regulates transcription of the gene encoding transforming growth factor beta2 (TGFbeta2) in myeloid cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3161–3176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bromleigh VC. Freedman LP. p21 is a transcriptional target of HOXA10 in differentiating myelomonocytic cells. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2581–2586. doi: 10.1101/gad.817100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnusson M. Brun AC. Miyake N. Larsson J. Ehinger M. Bjornsson JM. Wutz A. Sigvardsson M. Kalsson S. HOXA10 is a critical regulator for hematopoietic stem cells and erythroid/megakaryocyte development. Blood. 2007;109:3687–3696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satokata I. Benson G. Maas R. Sexually dimorphic sterility phenotypes in Hoxa10-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;374:460–463. doi: 10.1038/374460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson GV. Lim H. Paria BC. Satokata I. Dey SK. Mass RL. Mechanisms of reduced fertility in Hoxa-10 mutant mice: uterine homeosis and loss of maternal Hoxa-10 expression. Development. 1996;122:2687–2696. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rijli FM. Matyas R. Pellegrini M. Dierich A. Gruss P. Dolle P. Chambon P. Cryptorchidism and homeotic transformations of spinal nerves and vertebrae in Hoxa-10 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8185–8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanatta A. Rocha AM. Carvalho FM. Pereira RM. Taylor HS. Motta EL. Barcat EC. Serfini PC. The role of the Hoxa10/HOXA10 gene in the etiology of endometriosis and its related infertility: a review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:701–710. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du H. Taylor HS. Molecular regulation of mullerian development by Hox genes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1034:152–165. doi: 10.1196/annals.1335.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponzielli R. Astier M. Chartier A. Gallet A. Therond P. Semeriva M. Heart tube patterning in Drosophila requires integration of axial and segmental information provided by the Bithorax Complex genes and hedgehog signaling. Development. 2002;129:4509–4521. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovato TL. Nguyen TP. Molina MR. Cripps RM. The Hox gene abdominal-A specifies heart cell fate in the Drosophila dorsal vessel. Development. 2002;129:5019–5027. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YO. Park SJ. Balaban RS. Nirenberg M. Kim Y. A functional genomic screen for cardiogenic genes using RNA interference in developing Drosophila embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:159–164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307205101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tischfield MA. Bosley TM. Salih MA. Alorainy IA. Sener EC. Nester MJ. Oystreck DT. Chan WM. Andrews C. Erickson RP. Engle EC. Homozygous HOXA1 mutations disrupt human brainstem, inner ear, cardiovascular and cognitive development. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1035–1037. doi: 10.1038/ng1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makki N. Capecchi MR. Cardiovascular defects in a mouse model of HOXA1 syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:26–31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makki N. Capecchi MR. Identification of novel Hoxa1 downstream targets regulating hindbrain, neural crest and inner ear development. Dev Biol. 2011;357:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diman NY. Remacle S. Bertrand N. Picard JJ. Zaffran S. Razsohazy R. A retinoic acid responsive Hoxa3 transgene expressed in embryonic pharyngeal endoderm, cardiac neural crest and a subdomain of the second heart field. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis AP. Witte DP. Hsieh-Li HM. Potter SS. Capecchi MR. Absence of radius and ulna in mice lacking hoxa-11 and hoxd-11. Nature. 1995;375:791–795. doi: 10.1038/375791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kondo T. Dolle P. Zakany J. Duoule D. Function of posterior HoxD genes in the morphogenesis of the anal sphincter. Development. 1996;122:2651–2659. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Podlasek CA. Duboule D. Bushman W. Male accessory sex organ morphogenesis is altered by loss of function of Hoxd-13. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:454–465. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199704)208:4<454::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts DJ. Johnson RL. Burke AC. Nelson CE. Morgan BA. Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog is an endodermal signal inducing Bmp-4 and Hox genes during induction and regionalization of the chick hindgut. Development. 1995;121:3163–3174. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardoso WV. Mitsialis SA. Brody JS. Williams MC. Retinoic acid alters the expression of pattern-related genes in the developing rat lung. Dev Dyn. 1996;207:47–59. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199609)207:1<47::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabin CJ. Retinoids, homeoboxes, and growth factors: toward molecular models for limb development. Cell. 1991;66:199–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yutzey KE. Bader D. Diversification of cardiomyogenic cell lineages during early heart development. Circ Res. 1995;77:216–219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yutzey KE. Rhee JT. Bader D. Expression of the atrial-specific myosin heavy chain AMHC1 and the establishment of anteroposterior polarity in the developing chicken heart. Development. 1994;120:871–883. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masino AM. Gallardo TD. Wilcox CA. Olson EN. Williams RS. Garry DJ. Transcriptional regulation of cardiac progenitor cell populations. Circ Res. 2004;95:389–397. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138302.02691.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin CM. Ferdous A. Gallardo T. Humphries C. Sadek H. Caprioli A. Garcia JA. Szweda LI. Garry MG. Garry DJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha transactivates Abcg2 and promotes cytoprotection in cardiac side population cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iacovino M. Hernandez C. Xu Z. Bajwa G. Prather M. Kyba M. A conserved role for Hox paralog group 4 in regulation of hematopoietic progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:783–792. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsiao EC. Yoshinga Y. Nguyen TD. Musone SL. Kim JE. Swinton P. Espeneda I. Manalac C. deJong PJ. Conklin BR. Marking embryonic stem cells with a 2A self-cleaving peptide: a NKX2-5 emerald GFP BAC reporter. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L. Magli A. Catanese J. Xu Z. Kyba M. Perlingeiro RC. Modulation of TGF-beta signaling by endoglin in murine hemangioblast development and primitive hematopoiesis. Blood. 2011;118:88–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bosnakovski D. Xu Z. Gang EJ. Galindo CL. Liu M. Simsek T. Garner HR. Agha-Mohammadi S. Tassin A, et al. An isogenetic myoblast expression screen identifies DUX4-mediated FSHD-associated molecular pathologies. EMBO J. 2008;27:2766–2779. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darabi R. Arpke RW. Irion S. Dimos JT. Grskovic M. Kyba M. Perlingeiro RC. Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore DYSTROPHIN and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koyano-Nakagawa N. Kweon J. Iacovino M. Shi X. Rasmussen TL. Borges L. Zirbes LM. Li T. Perlingeiro RC. Kyba M. Garry DJ. Etv2 is expressed in the yolk sac hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors and regulates Lmo2 gene expression. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1611–1623. doi: 10.1002/stem.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindsley RC. Gill JG. Murphy TL. Langer EM. Cai M. Mashayekhi M. Wang W. Niwa N. Nerbonne JM. Kyba M. Murphy KM. Mesp1 coordinately regulates cardiovascular fate restriction and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in differentiating ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakurai H. Era T. Jakt LM. Okada M. Nakai S. Nishikawa S. In vitro modeling of paraxial and lateral mesoderm differentiation reveals early reversibility. Stem Cells. 2006;24:575–586. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norris DP. Robertson EJ. Asymmetric and node-specific nodal expression patterns are controlled by two distinct cis-acting regulatory elements. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1575–1588. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adachi H. Saijoh Y. Mochida K. Ohishi S. Hashiguchi H. Hirao A. Hamada H. Determination of left/right asymmetric expression of nodal by a left side-specific enhancer with sequence similarity to a lefty-2 enhancer. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1589–1600. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabin CJ. The key to left-right asymmetry. Cell. 2006;27:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burke AC. Nelson CE. Morgan BA. Tabin C. Hox genes and the evolution of vertebrate axial morphology. Development. 1995;121:333–346. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thickett C. Morgan R. Hoxc-8 expression shows left-right asymmetry in the posterior lateral plate mesoderm. Gene Expr Patterns. 2002;2:5–6. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00353-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shiratori H. Sakuma R. Watanabe M. Hashiguchi H. Mochia K. Sakai Y. Nishino J. Saijoh Y. Whitman M. Hamada H. Two-step regulation of left-right asymmetric expression of Pitx2: initiation by nodal signaling and maintenance by Nkx2. Mol Cell. 2001;7:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durocher D. Charron F. Warren R. Schwartz RJ. Nemer M. The cardiac transcription factors Nkx2-5 and GATA-4 are mutual cofactors. EMBO J. 1997;16:5687–5696. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee Y. Shioi T. Kasahara H. Jobe SM. Wiese RJ. Markham BE. Izumo S. The cardiac tissue-restricted homeobox protein Csx/Nkx2.5 physically associates with the zinc finger protein GATA4 and cooperatively activates atrial natriuretic factor gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3120–3129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarno JL. Kliman HJ. Taylor HS. HOXA10, Pbx2, and Meis1 protein expression in the human endometrium: formation of multimeric complexes on HOXA10 target genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:522–528. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svingen T. Tonissen KF. Hox transcription factors and their elusive mammalian gene targets. Heredity (Edinb) 2006;97:88–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shah N. Sukumar S. The Hox genes and their roles in oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:361–371. doi: 10.1038/nrc2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reecy JM. Li X. Yamada M. DeMayo FJ. Newman CS. Harvey RP. Schwartz RJ. Identification of upstream regulatory regions in the heart-expressed homeobox gene Nkx2-5. Development. 1999;126:839–849. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.