Abstract

Objectives

We hypothesise that rising prevalence rates of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) increase infection risk and worsen outcomes among socially disadvantaged Indigenous Australians undergoing a rapid epidemiological transition.

Design

Available pathology, imaging and discharge morbidity codes were retrospectively reviewed for a period of 5 years prior to admission with a bloodstream infection (BSI), 1 January 2003 to 30 June 2007.

Participants

558 Indigenous and 55 non-Indigenous community residents of central Australia.

Outcome measures

The effects of NCDs on risk of infection and death were determined after stratifying by ethnicity.

Results

The mean annual BSI incidence rates were far higher among Indigenous residents (Indigenous, 937/100 000; non-Indigenous, 64/100 000 person-years; IRR=14.6; 95% CI 14.61 to 14.65, p<0.001). Indigenous patients were also more likely to have previous bacterial infections (68.7% vs 34.6%; respectively, p<0.001), diabetes (44.3% vs 20%; p<0.001), harmful alcohol consumption (37% vs 12.7%; p<0.001) and other communicable diseases (human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, 45.2%; strongyloidiasis, 36.1%; hepatitis B virus, 12.9%). Among Indigenous patients, diabetes increased the odds of current Staphylococcus aureus BSI (OR=1.6, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.5) and prior skin infections (adjusted OR=2.1, 95% CI 1.4 to 3.3). Harmful alcohol consumption increased the odds of current Streptococcus pneumoniae BSI (OR=1.57, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.40) and of previous BSI (OR=1.7, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.5), skin infection (OR=1.7, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.6) or pneumonia (OR=4.3, 95% CI 2.8 to 6.7). Twenty-six per cent of Indigenous patients died at a mean (SD) age of 47±15 years. Complications of diabetes and harmful alcohol consumption predicted 28-day mortality (non-rheumatic heart disease, HR=2.9; 95% CI 1.4 to 6.2; chronic renal failure, HR=2.6, 95%CI 1.0 to 6.5; chronic liver disease, HR=3.3, 95% CI 1.6 to 6.7).

Conclusions

In a socially disadvantaged population undergoing a rapid epidemiological transition, NCDs are associated with an increased risk of infection and BSI-related mortality. Complex interactions between communicable diseases and NCDs demand an integrated approach to management, which must include the empowerment of affected populations to promote behavioural change.

Keywords: Infectious Diseases, Microbiology

Article summary.

Article focus

Remote dwelling, Indigenous Australians are undergoing a rapid epidemiological transition, which is accompanied by a rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

In this setting of social disadvantage and frequent pathogen exposure, NCDs may increase the risk of infection and infection-related death.

Key messages

We reveal substantial racial disparities in rates of infection and of NCDs, reflecting the dual burden of disease that affects this Indigenous population.

NCDs were associated with an increased risk of bloodstream infections (BSIs) with some pathogens, previous infections that provide portals of entry for life-threatening invasive disease and infection-related mortality.

Complex interactions between communicable diseases and NCDs demand an integrated approach to management, which must include the empowerment of affected populations to promote behavioural change.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This hospital-based study only includes patients who were admitted with a BSI. We are therefore unable to determine the actual risk of BSIs that is attributable to NCDs or to comment on the background rates of other infections that might be treated in the community.

The major strength of our study lies in the demography of the study population, which is served by a single hospital, and the extensive nature of the clinical material on which our analysis is based.

Introduction

Complex interactions between the demographic, economic and sociological determinants of disease result in changing patterns of health and disease over time.1 The development of modern social and economic structures, for example, has been associated with a reduction in infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies and a corresponding rise in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) that are associated with ageing and lifestyle.1 In many developing countries, the rapidity of this ‘epidemiological transition’ has resulted in a dramatic increase in NCD prevalence among populations that have a substantial pre-existing infectious disease burden.2 3 This phenomenon proceeds at different rates according to the socioeconomic status of particular subgroups within a given population and may reinforce established health inequalities.4 5

Among Indigenous people, forced displacement, the collapse of Indigenous economies and the destruction of sociopolitical structures have been the shared experience of colonisation.6 Indigenous people living within developed countries continue to live in poverty and experience a ‘protracted’ epidemiological transition4 that is associated with a double burden of communicable diseases and NCDs,7 8 similar to that of many developing countries.2 In central Australia, for example, diabetes and other NCDs are the major contributors to racial disparities in mortality8 and to a life expectancy that remains 14 years less for Indigenous Australian men relative to their non-Indigenous peers.9 A high burden of infectious diseases persists in this Indigenous population. Incidence rates of sepsis,10 bloodstream infections (BSIs)11 and childhood pneumonia12 and prevalence rates of bronchiectasis13 are the highest reported worldwide. Strongyloidiasis and chronic viral infections, such as with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and the human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), are also common.11 Population-based infection-related mortality rates for Indigenous adults in central Australia therefore remain higher than those of some African countries prior to the current HIV pandemic and the median age of in-hospital death is only 48 years.14

Interactions between communicable diseases and NCDs have been little studied; however, an appreciable effect of NCDs on infection rates is likely where pathogen exposure is frequent. Diabetes, for example, contributes to the risk of serious bacterial infections including Streptococcus pneumoniae15 and Staphylococcus aureus,16 which are common pathogens in overcrowded Indigenous Australian communities.11 The NCD burden may therefore have a substantial impact on infection rates and outcomes where these two epidemics coincide. Such an interaction could reverse health gains in populations undergoing a rapid epidemiological transition and exacerbate health inequalities among disadvantaged subgroups within developed countries. The recent description in New Zealand of an increasing divergence in infection-related hospitalisation rates according to social status is consistent with this possibility and challenges health-transition theory.17

Central Australia is well placed to study interactions between poverty, NCDs and infectious diseases. Most Indigenous residents live in remote communities in conditions of considerable socioeconomic disadvantage, leaving a minority within the major regional township of Alice Springs. The latter have ready access to a well-resourced medical facility, Alice Springs Hospital (ASH), which has sophisticated diagnostic capabilities and provides specialist medical care to a region of 1 000 000 km2. Indigenous residents of Alice Springs dwell in either overcrowded ‘town camps’, which have poor amenities and limited refuse disposal, or are integrated with the majority of the non-Indigenous population within the township's suburbs. Indigenous adults living in town camps and remote communities are often unemployed and have limited education and poor health literacy.18 Among Indigenous adult residents of town camps, nearly half have 8 years or less schooling, labour participation rates are less than 20% and only 12% are employed.19 Despite an extremely complex regulatory framework and numerous Government attempts to minimise risk, harmful alcohol consumption in this setting remains common.20

The Indigenous population of central Australia also has among the highest BSI incidence rates reported.11 Living conditions that increase the risk of pathogen exposure21 and high background rates of focal infections, which provide portals of entry for bacterial invasion, are likely to precede these life-threatening infections. BSI incidence rates therefore provide measurable endpoints to which environmental and host factors contribute. We report the infectious and NCD burden among community residents of central Australia who presented with a BSI and determine risk factors for infection and death after stratifying by ethnicity.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of all positive blood cultures collected from adult patients (age≥15 years) admitted to ASH between 1 January 2001 and 31 June 2007. In July 2007, the Australian Federal Government suspended racial discrimination legislation and implemented an ‘Emergency Response’ that resulted in considerable uncertainty among Indigenous residents.22 This raised concerns that the central Australian resident population could change as people moved interstate to escape these restrictions and no data were collected after this date. Data collected included organism, ethnicity, dates of birth, dates of death, indigenous status and place of residence. For patients who presented between 1 January 2003 and 31 June 2007, we also reviewed available International Classification of Diseases (ICD) morbidity codes and results of microbiological and radiological investigations for each admission for 5 years prior to the final BSI presentation. NCDs were derived from ICD-10 Australian Modification (AM) morbidity codes for diabetes, harmful alcohol consumption, >stage 2 chronic kidney disease, ischaemic heart disease, chronic liver disease and malignancy. Bronchiectasis was diagnosed radiologically using American College of Chest Physician criteria. Heart failure and valvular heart disease, including rheumatic heart disease (RHD), were diagnosed by transthoracic echocardiography. Ischaemic heart disease and cardiac failure were combined (‘non-rheumatic heart disease’) for statistical analysis.

Definitions

Residence

Place of residence was categorised as (1) remote (>80 km from Alice Springs), (2) Alice Springs town camp and (3) urban (resident in Alice Springs, but not in a town camp). Nursing home residents were included in calculations of BSI incidence rates, but excluded from further analysis because the primary study objective was to determine risk factors for infection and death among community residents.

Infections

A blood culture from which a pathogen was isolated was defined as a ‘BSI episode’. Repeated culture of the same organism from blood cultures was regarded as a separate ‘episode’ only if blood samples were drawn more than 1 month apart. BSIs were defined as community-acquired if a pathogen was isolated from blood cultures drawn within 48 h of admission and nosocomial if isolated from blood cultures drawn after this time. Foci of infection were determined where possible from ICD morbidity codes in association with pathology and imaging results for each admission for 5 years prior to the final BSI during the study period. A diagnosis of pneumonia was made if there was radiological evidence of consolidation and this was attributed to the pathogen isolated from blood cultures if the same organism was also isolated from sputum or the blood culture isolate was an organism typically associated with pneumonia, such as S pneumoniae. BSIs exclude potential contaminants including coagulase negative staphylococci, Bacillus spp., coryneforms and viridans streptococci unless grown from more than one BC in a 24 h period and Acinetobacter sp. in the absence of an identifiable focus.

The study was approved by the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (http://www.health.nt.gov.au/Agency/Advisory_Groups_and_Taskforces/Human_Research_Ethics_Committee/index.aspx).

Statistics

All associations were assessed using data obtained for the final BSI admission within the study period. Univariate analysis for categorical data was performed using χ2 statistics and Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate. Multivariate analysis was performed using binary logistic regression. Short-term (28-day) and long-term survival analyses following the final BSI episode in the study period were performed using the log-rank statistic for univariate analysis and Cox regression for multivariate analysis. We calculated the annual population-based incidence rates for 2001–2006 for the combined Alice Springs and Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunyatjara (APY) land areas using the total number of BSI presentations each year as the numerator. The denominator used was the estimated adult resident population obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006 census data for the Alice Springs region combined with that of the neighbouring APY land areas. To enable analysis according to place of residence, this population was further divided into that of (1) the Alice Springs urban area excluding town camps (Indigenous 2898, non-Indigenous 18471), (2) Alice Springs town camps, including that of a closely affiliated neighbouring community (Indigenous, 1482) and (3) the Alice Springs rural area (Indigenous, 8925; non-Indigenous, 2775), which included that for the APY land areas (Indigenous=1302, non-Indigenous=294).

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 558 Indigenous and 55 non-indigenous adult community residents presented to ASH with a BSI between January 2003 and July 2007. Detailed demographic, clinical and microbiological data are described in table 1. Indigenous patients were younger (Indigenous, 44.7±15.2; non-Indigenous, 57.5±21.1; p<0.001) and more likely to be female (Indigenous, 58.1%; non-Indigenous, 41.8%; p<0.03) and to live in a town camp or remote community (Indigenous, 84%; non-Indigenous, 0; p<0.001). NCDs including diabetes (Indigenous, 44.3%; non-Indigenous, 20%; p<0.001) and harmful alcohol consumption (Indigenous, 37%; non-Indigenous, 12.7%; p<0.001) were more common among Indigenous patients, while non-Indigenous patients were more likely to have ischaemic heart disease (Indigenous, 3.4%; non-Indigenous, 31.6%; p<0.001), malignancy (Indigenous, 2.3%; non-Indigenous, 20%; p<0.001), to be receiving palliative care (Indigenous, 1.8%; non-Indigenous, 9.1%; p=0.001) and to have a history of intravenous drug use (Indigenous, 0; non-Indigenous, 5.5%; p=0.001). Forty-seven (8.4%) Indigenous and 5 (9.3%) non-indigenous BSI episodes were nosocomial (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and comorbidities for indigenous and non-indigenous BSI patients 2003–2007

| Indigenous (n=558) | Non-indigenous (n=55) | p Value for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (±SD) | 44.7±15.2 | 57.5±21.1 | <0.001 |

| Gender (M/F) (%) | 234/324 (42/58) | 31/23 (57/43) | 0.03 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 89 (16.0) | 55 (100.0) | |

| Town camp | 136 (24.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Remote community | 333 (59.7) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities* | |||

| Diabetes | 247 (44.3) | 11 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Harmful alcohol consumption | 205 (37.0) | 7 (12.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| Stages 3–4 | 34 (6.1) | 5 (9.1) | 0.39 |

| Stage 5 | 83 (14.9) | 3 (5.5) | 0.06 |

| Chronic liver disease† | 53 (9.6) | 6 (10.9) | 0.74 |

| Bronchiectasis | 27 (4.8) | 0 | 0.10 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 15 (2.7) | 3 (5.5) | 0.25 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 9 (1.6) | 7 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 27 (4.8) | 3 (5.5) | 0.84 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 12 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.27 |

| Palliative care | 10 (1.8) | 5 (9.1) | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | 13 (2.3) | 11 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| IVDU | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.5) | 0.001 |

| Community acquired | 510 (91.6) | 49 (90.7) | 0.84 |

| Primary focus of BSI | |||

| No focus | 250 (44.8) | 20 (36.4) | 0.37 |

| Pneumonia‡ | 110 (19.7) | 6 (10.9) | 0.08 |

| Skin abscess | 66 (11.8) | 5 (9.1) | 0.65 |

| Pyelonephritis§ | 63 (11.3) | 5 (9.1) | 0.56 |

| Other | 53 (9.5) | 18 (32.7) | <0.001 |

| Enteritis | 15 (2.7) | 1 (1.8) | 0.71 |

| Bone/joint | 1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.61 |

| Additional infections¶ | |||

| Acute bacterial infections | 69 (12.4) | 2 (3.6) | 0.05 |

| Pneumonia | 18 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.39 |

| Urinary tract infection | 20 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | 0.49 |

| Skin infection | 27 (4.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0.31 |

| Enteritis | 4 (0.7) | 0 | 0.53 |

| Chronic viral infections | |||

| HTLV-1** | 137 (45.2) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis B virus** | |||

| HBsAg | 49 (12.9) | 1 (6.7) | 0.70 |

| Anti-HBc | 193 (62.5) | 3 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Parasites | |||

| Strongyloidiasis** | 78 (36.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| Scabies | 20 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 |

| Mortality | |||

| 28 days | 62 (11.1) | 7 (12.7) | 0.72 |

| All deaths | 145 (26.0) | 15 (27.3) | 0.84 |

| Age of death (years) | 47±15 | 68±21 | <0.001 |

| Major BSI pathogens†† | 1029 | 110 | |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 370 (36.0) | 38 (34.5) | 0.56 |

| Escherichia coli | 246 (66.5) | 28 (73.7) | 0.37 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 57 (15.4) | 2 (5.3) | 0.09 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 191 (18.6) | 20 (18.2) | 0.83 |

| MRSA | 53 (27.8) | 1 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 136 (13.2) | 8 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 68 (6.6) | 8 (7.3) | 0.42 |

| Haemophilus influenza | 22 (2.14) | 0 | 0.14 |

| Enteric pathogens‡‡ | 29 (2.81) | 1 (0.91) | 0.27 |

*Comorbidities determined from ICD-10 AM discharge morbidity codes.

†Chronic liver disease attributed to alcohol (Indigenous, 43; non-Indigenous, 5), chronic hepatitis B (Indigenous, 10; non-Indigenous, 0) and chronic hepatitis C (Indigenous, 0; non-Indigenous, 3).

‡Chest X-rays performed for 457 Indigenous patients. Respiratory cultures performed for 150 Indigenous patients.

§Urine cultures performed for 310 Indigenous patients.

¶Pathogens identified in addition to those isolated from blood cultures. Pneumonia, urinary tract, skin and enteritis expressed as a proportion of the total number of acute bacterial infections.

**Indigenous patients tested: HTLV-1, 309; HBsAg, 388; HBcAb, 309; Strongyloides stercoralis serology, 235. Non-Indigenous patients tested: HTLV-1, 4; HBsAg, 16; HBcAb, 11; Strongyloides stercoralis serology, 4. Denominators exclude six Indigenous patients with indeterminate HTLV-1 western blot results and 19 Indigenous patients with borderline Strongyloides serology whose infective status could not be determined.

††Major BSI pathogens for all recorded episodes 2001–2007. E coli and K pneumoniae expressed as a proportion of the Enterobacteriaceae and MRSA expressed as a proportion of all S aureus isolates.

‡‡Includes Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp.

BSI, bloodstream infection; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen positive; anti-HBc, Hepatitis B core antibody positive; HTLV-1, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; IVDU, intravenous drug use; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Population-based incidence rates 2001–2006

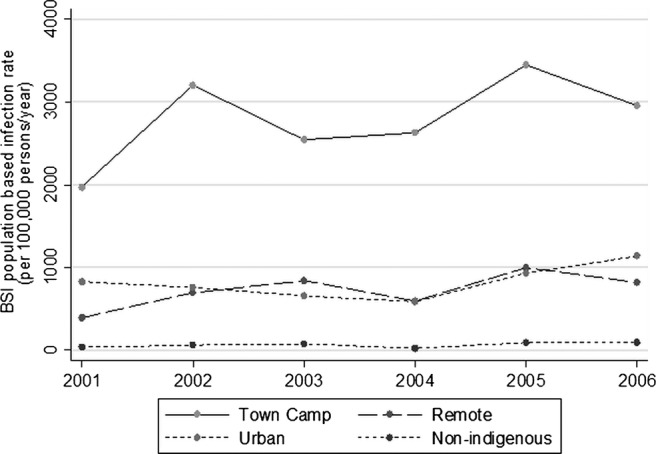

The overall population-based BSI incidence rate for the Alice Springs area between 2001 and 2006 was nearly 15 times higher for Indigenous adults (937/100 000 person-years) than for non-Indigenous adults (64/100 000 person-years; incidence rate ratio (IRR)=14.6; 95% CI 14.61, 14.65; p<0.001). Incidence rates for Indigenous town camp residents (2794/100 000 person-years) were more than 40 times higher than those of non-Indigenous urban residents (64/100 000 person-years; IRR=43.6, 95% CI 43.57 to 43.65, p<0.001) and at least three times higher than those of urban dwelling Indigenous adults (IRR=3.421, 95% CI 3.418 to 3.423, p<0.001) or those from remote communities (IRR=3.87, 95% CI 3.864 to 3.868, p<0.001) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bloodstream infection incidence rates according to ethnicity and place of residence. Town camp, Indigenous residents of town camp; urban, Indigenous residents of township who do not reside in a town camp; remote, Indigenous residents of remote Indigenous communities. Non-Indigenous residents of Alice Springs region.

Microbial aetiology

Escherichia coli and S aureus were the most common pathogens causing BSI in both ethnic groups. Methicillin-resistant S aureus (Indigenous, 53 (5.2%); non-Indigenous, 1 (0.9%); p<0.001) and S pneumoniae (Indigenous, 136 (13.2%); non-Indigenous, 8 (5.9%); p<0.001) were more common among Indigenous patients (table 1).

Risk factors for BSI were determined for pathogens contributing more than 5% of all BSI episodes (table 2). Diabetes was more common among Indigenous patients with an S aureus BSI during their final BSI admission (20.2% vs 13.5%; OR=1.6 (1.04, 2.53; p=0.03; table 2). In contrast, increased risk of S pneumoniae BSI was associated with harmful alcohol consumption, while risk was reduced among patients with diabetes or those receiving haemodialysis (table 2). Risk of BSI with other major pathogens (E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae or Streptococcus pyogenes) was not increased by any NCD (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and non-communicable disease associations for the major BSI pathogens isolated from Indigenous adults

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

Streptococcus pneumoniae |

Klebsiella pneumoniae |

Escherichia coli |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No (%) | Yes (%) | p Value* | No (%) | Yes (%) | p Value* | No (%) | Yes (%) | p Value* | No (%) | Yes (%) | p Value* | |

| Residence | |||||||||||||

| Urban | 89 | 86.5 | 13.5 | 89.9 | 10.1 | 96.6 | 3.4 | 76.4 | 23.6 | ||||

| Town camp | 136 | 88.2 | 11.8 | 83.1 | 16.9 | 91.9 | 8.1 | 73.5 | 26.5 | ||||

| Remote | 333 | 80.5 | 19.5 | 0.08 | 89.2 | 10.8 | 0.15 | 94.6 | 5.4 | 0.30 | 73.0 | 27.0 | 0.81 |

| Diabetes | |||||||||||||

| No | 310 | 86.5 | 13.6 | 83.9 | 16.1 | 93.9 | 6.1 | 74.1 | 25.8 | ||||

| Yes | 247 | 79.8 | 20.2 | 0.035 | 92.7 | 7.3 | 0.002 | 94.7 | 5.3 | 0.66 | 72.9 | 27.1 | 0.73 |

| CRF | |||||||||||||

| No | 524 | 83.4 | 16.6 | 87.6 | 12.4 | 94.3 | 5.7 | 73.7 | 26.3 | ||||

| Yes | 34 | 82.4 | 17.7 | 0.87 | 91.2 | 8.8 | 0.54 | 94.1 | 5.9 | 0.97 | 73.5 | 26.5 | 0.99 |

| HD | |||||||||||||

| No | 475 | 84.2 | 15.8 | 86.3 | 13.7 | 94.1 | 5.9 | 70.5 | 29.5 | ||||

| Yes | 83 | 78.3 | 21.7 | 0.18 | 96.4 | 3.6 | 0.01 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 0.70 | 92.6 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| CLD | |||||||||||||

| No | 505 | 82.4 | 17.6 | 87.7 | 12.3 | 93.9 | 6.1 | 73.5 | 26.5 | ||||

| Yes | 53 | 92.5 | 7.6 | 0.06 | 88.7 | 11.3 | 0.84 | 98.1 | 1.9 | 0.20 | 75.6 | 24.5 | 0.75 |

| Alcohol | |||||||||||||

| No | 349 | 82.2 | 17.8 | 92.0 | 8.0 | 95.1 | 4.9 | 75.1 | 24.9 | ||||

| Yes | 205 | 84.9 | 15.1 | 0.42 | 80.5 | 19.5 | <0.001 | 93.1 | 6.8 | 0.33 | 71.7 | 28.3 | 0.38 |

*Using chi-squared test of association.

Major BSI pathogens recorded during the final BSI admission.

Alcohol, harmful alcohol consumption; BSI, bloodstream infection; CRF, stage 3 or 4 chronic renal disease; HD, stage 5 renal disease; CLD, chronic liver disease.

Concurrent infections

During their final BSI admission, Indigenous patients more often had an additional focus of bacterial infection unrelated to the presenting BSI (Indigenous, n=69 (12.4%); non-Indigenous, n=2 (3.6%); p=0.05; (table 1). Infections with HTLV-1 (45.2%), Strongyloides stercoralis (36.1%) and HBV (anti-HBc, 62.5%; HBsAg, 12.9%) were also more common among Indigenous patients (table 1). Sarcoptes scabiei infestations were only found in Indigenous patients (n=20; 4%; table 1).

Previous infections

Excluding Indigenous patients who were at increased risk of recurrent infection (haemodialysis, 83; bronchiectasis, 27) and those residing outside the Alice Springs region who could not be followed up (17), 296 of 431 (68.7%) Indigenous adults were admitted with an acute infection during the 5 years prior to the final BSI admission (table 3). Significantly more common among Indigenous patients were pneumonia, previous BSI, skin abscesses and wound infections (table 3). Predisposing factors for previous infection-related admissions included diabetes (previous skin infections), harmful alcohol consumption (previous skin infections, pneumonia and BSI) and stages 3–4 chronic kidney disease (any previous infection; table 4).

Table 3.

Infections recorded for Indigenous and non-Indigenous adults during the 5 years prior to the final BSI presentation*

| Indigenous n=431 (%) | Non-Indigenous (n=52) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any | 296 (68.7) | 18 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| BSI | 105 (24.4) | 4 (7.7) | 0.007 |

| Respiratory tract | 179 (41.5) | 3 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 164 (38.1) | 4 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| >3 Episodes | 32 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.04 |

| Exacerbation BE | 13 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.20 |

| Skin/soft tissue infections | 154 (35.7) | 7 (13.5) | 0.001 |

| Abscess | 88 (20.5) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Cellulitis | 47 (10.9) | 7 (13.7) | 0.55 |

| Wound infection | 42 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 |

| Pyelonephritis | 77 (17.9) | 4 (7.7) | 0.06 |

| Bone/joint | 11 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 |

| Enteritis | 21 (4.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0.33 |

| Scabies | 14 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.19 |

| Other | 6 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.39 |

*Excluding haemodialysis patients (n=83 indigenous, 3 non-indigenous), patients with bronchiectasis (n=27 Indigenous, 0 non-indigenous) and those residing outside the Alice Springs urban and rural districts for whom data were not available (Indigenous, 18; non-Indigenous, 0).

BSI, bloodstream infections; BE, bronchiectasis.

Table 4.

Multivariate adjusted ORs for demographic factors and non-communicable diseases associated with previous infections among Indigenous patients*

| Any infection (n=470)† OR (95% CI) | BSI (n=553) OR (95% CI) | Skin† (n=470) OR (95% CI) | Pneumonia‡ (n=443) OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Town camp | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.4) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.6) |

| Remote | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.4) |

| Age (10 years) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Gender (0=F, 1=M) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) |

| Diabetes | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.3) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) |

| CRF | 3.0 (1.1 to 8.2) | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.8) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.2) | 1.6 (0.7 to 3.7) |

| Alcohol | 2.8 (1.8 to 4.4) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.5) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | 4.3 (2.8 to 6.7) |

*Previous infections during the 5 years prior to the final BSI in the study period. Adjusted for other risk factors in the table.

†Excluding patients receiving haemodialysis.

‡Excluding patients receiving haemodialysis and those with bronchiectasis.

BSI, bloodstream infections; CRF, chronic renal failure excluding patients receiving haemodialysis.

Mortality

A 28-day mortality

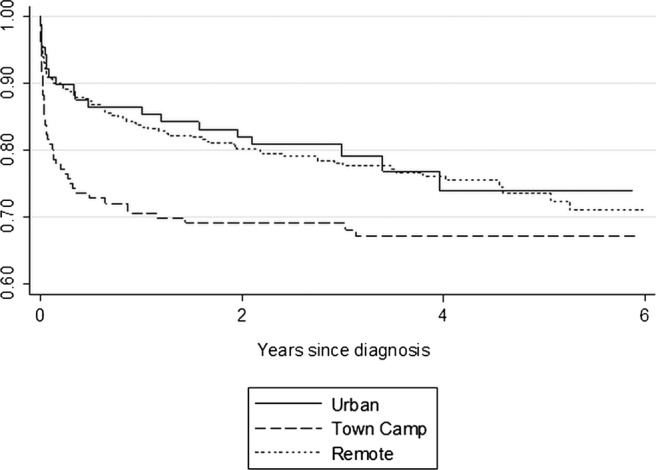

Overall 28-day mortality rates following a BSI were 11.7% and 11.4% for Indigenous and non-Indigenous adults, respectively. Mortality rates among Indigenous patients were highest for town camp residents (figure 2) and varied according to pathogen. Among the major pathogens causing BSI, most often fatal within the first 28 days was K pneumoniae infection (40%) followed by S pneumoniae (9.6%), S aureus (8%) and E coli (5%; χ2=39.1, 4df; p<0.001). Case fatality rates according to focus of infection were pneumonia (21.5%), pyelonephritis (8.9%) and skin infections (7.2%; χ2=14.5, 3df; p=0.002).

Figure 2.

Survival following the final BSI recorded during the study period according to the place of residence. Urban, residence within the township but not in a town camp; town camp, residence in a town camp within the township; remote, residence in a remote indigenous community. The median follow-up time for all Indigenous subjects was 3.23 years and for urban, town camp and remote subjects, it was 2.99, 3.04 and 3.38 years, respectively.

Community-acquired BSI among Indigenous patients

NCDs including chronic liver disease, non-RHD and chronic kidney disease were independent predictors of death (table 5). Relative to patients with E coli BSI, both S aureus (HR=2.7, 95% CI 1.0 to 7.3; p=0.05) and S pneumoniae (HR=13.4, 95% CI 4.6 to 39.2; p<0.001) were independently associated with an increased risk of death (table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with 28-day and long-term survival for 510 Indigenous patients following a community-acquired BSI*

| Deaths (28 days) | Deaths (all) | 28-day survival |

Long-term survival |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

| Residence | |||||||

| Urban | 63 | 7 | 20 | 1.00 | 0.12 | 1.0 | 0.28 |

| Town camp | 125 | 20 | 37 | 1.7 (0.7 to 4.1) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | ||

| Remote | 302 | 22 | 67 | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) | ||

| Age (10 years) | 1.04 (0.8 to 1.3) | 0.70 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 0.99 | |||

| Gender (0=F,1=M) | 298F/212M | 23/26 | 65/59 | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.7) | 0.17 | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | 0.13 |

| CLD (0=no, 1=yes) | 41 | 11 | 20 | 3.3 (1.6 to 6.7) | 0.001 | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.2) | <0.001 |

| Non-RHD | 37 | 9 | 16 | 2.9 (1.4 to 6.2) | 0.005 | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.6) | 0.01 |

| CRF | 28 | 6 | 11 | 2.6 (1.0 to 6.5) | 0.04 | 2.3 (1.2 to 4.3) | 0.01 |

| Malignancy | 11 | 3 | 10 | 2.9 (0.9 to 9.9) | 0.09 | 6.0 (3.0 to 12.4) | <0.001 |

| Organism† | |||||||

| Escherichia coli | 143 | 5 | 22 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 83 | 7 | 18 | 2.7 (1.0 to 7.3) | 0.05 | 1.8 (1.1 to 3.0) | 0.03 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 29 | 12 | 15 | 2.3 (0.7 to 7.5) | 0.17 | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.7) | 0.17 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 67 | 5 | 17 | 13.4 (4.6 to 39.2) | <0.001 | 4.8 (2.5 to 9.5) | <0.001 |

| Other | 188 | 20 | 52 | 1.8 (0.5 to 6.3) | 0.37 | 1.5 (0.8 to 3.0) | 0.22 |

*Survival following the final BSI recorded during the study period. Analysis excludes 48 nosocomial BSI episodes.

†Pathogens isolated from the last positive blood cultures drawn during the study period.

BSI, bloodstream infection; CCF, congestive cardiac failure; CLD, chronic liver disease; CRF, chronic renal failure; non-RHD, non-rheumatic heart disease.

Nosocomial BSI among Indigenous patients

In univariate analysis, place of residence (p=0.04) was a predictor of short-term mortality. Within the first 28 days of admission, town camp residents were more likely to die (7 of 11=64%) relative to other township (0 of 6=0.0%) or remote residents (14 of 30=46.7%; p=0.039). In multivariate analysis, place of residence remained an independent predictor (p<0.001) and there was also an increased risk in those with non-RHD (HR=4.6, 95% CI 1.2 to 17.6; p=0.03), a primary focus of pneumonia (HR=6.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 24.5), and those with a previous BSI (HR=3.8, 95% CI 1.4 to 10.3; p−0.008).

Nosocomial and community-acquired BSI among non-indigenous patients

In multivariate analysis, only non-RHD was an independent predictor of short-term mortality among non-indigenous patients with a community-acquired BSI (HR=12.5, 95% CI 1.0 to 150.3; p<0.05). There were 3 deaths within 28 days among 12 non-indigenous patients with non-RHD and 3 deaths among 56 patients without non-RHD. Numbers of nosocomial BSI among non-indigenous patients were too few (n=5) to attempt survival analysis.

Long-term mortality

One hundred and forty-five (26%) Indigenous and 15 (27.3%) non-Indigenous patients died during the 2056 years of follow-up at a mean±SD age of 47±15 and 68±21 years (p<0.001), respectively. Among Indigenous patients, mortality rates were again highest among those from town camps (Log-rank χ2=5.05, p=0.08; figure 2).

Among Indigenous patients, NCDs (non-RHD, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease and malignancy) and BSI with S aureus and S pneumoniae were independent predictors of long-term mortality following community-acquired BSI (table 5). Residence in a town camp (town camp, 7 of 11; urban residence, 0 of 6; remote areas, 14 of 30; χ2=6.5, 2df; p=0.04) and BSI with K pneumoniae BSI (HR=4.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 11.2; p=0.007) were the only univariate predictors of long-term mortality for nosocomial BSIs among Indigenous patients.

There were no independent predictors of long-term mortality for non-Indigenous patients with community-acquired infections and too few non-indigenous patients with nosocomial BSIs (n=5) to perform long-term survival analysis.

Discussion

The Indigenous adult population of central Australia has among the highest BSI incidence rates worldwide. Relative to their non-Indigenous peers, rates for Indigenous adults were nearly 15-fold higher overall and 40-fold higher among Indigenous town camp residents. A high burden of other infections, particularly repeated respiratory and skin infections, provides portals of entry for life-threatening invasive bacterial disease. Nearly 70% of Indigenous patients required admission for an acute infection in the preceding 5 years, 24.4% experienced a prior BSI and a second unrelated bacterial infection was found in 12.4% of patients. Chronic viral and parasitic infections were also common. Among Indigenous adults who were tested, more than 60% had been infected with hepatitis B virus, 13% remained HBsAg positive, nearly half were HTLV-1 seropositive and 36% were S stercoralis seropositive. A similar burden of infection is experienced by Indigenous children among whom frequent coinfection with bacterial pathogens and parasites23 contributes to ‘failure-to-thrive’.24 In our adult cohort, 26% of Indigenous patients died during the study period at a mean age of only 47 years. Although we were unable to attribute cause of death in the present study, 60% of Indigenous deaths at ASH are infection-related.14

High prevalence rates of NCDs were also found in our Indigenous cohort. These included diabetes, harmful alcohol consumption, chronic lung disease and end-stage kidney disease, all of which increase the risk of bacterial infection.15 16 25 26 Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), for example, is 3, 5.6 and 7–11 times more common among patients with diabetes,15 chronic lung disease15 and alcohol dependence,15 27 respectively. Alcohol dependence and diabetes also increase the risk of a BSI requiring intensive care nearly six-fold and haemodialysis increases risk several 100-fold,26 largely due to prolonged central venous access.28 In the present study, the rates of diabetes among Indigenous adults were nearly three times the reported background rates.29 Diabetes was associated with S aureus BSI and with previous skin infections, but not with S pneumoniae BSI. Stages 3–4 chronic kidney disease, which is most often a complication of diabetes in our patient population,30 was associated with any previous infection. Harmful alcohol consumption was associated with S pneumoniae BSI and with previous infection-related admissions. NCDs, including non-RHD, chronic kidney disease and chronic liver disease, were also major predictors of mortality after a BSI. However, once invasive infections were established, S aureus and S pneumoniae predicted death independently of any underlying medical condition.

The present study has compared the risk of NCDs among patients presenting with a BSI and cannot determine the population-based risks attributable to these conditions. Nevertheless, racial disparities in NCD prevalence are unlikely to fully account for the BSI incidence rate ratios reported here, and nor do regional differences in their prevalence29 explain IPD incidence rates that are twice as high among Indigenous residents of central Australia relative to those of the tropical north.31 In the USA, higher IPD incidence rates among Black Americans15 32 are more robustly associated with poverty than race.32 An increased risk of S aureus infection has also been reported among those of lower socioeconomic position33–35 and infection-related hospital admissions in New Zealand are associated with social deprivation.17 The socioeconomic circumstances of Indigenous Australians are therefore likely to further increase the infection risks associated with NCDs.

Social disadvantage predisposes to NCDs36 37 while increasing pathogen exposure and limiting opportunities to implement behavioural strategies that ameliorate risk.38 In some Indigenous Australian communities, the average number of people living per house is 1739 and non-functioning health hardware leads to environmental conditions that are detrimental to householders.21 Overcrowded housing40 and an inability to maintain adequate skin hygiene21 contribute to high rates of pyoderma. More than 40% of Indigenous patients in the present study were previously admitted with skin infections, which are the most common primary focus for S aureus bacteraemia in this population.41 Scabies, a recognised cause of S aureus and Streptococcal pyoderma,40 42 affected 4% of our cohort. Streptococcal pyoderma underlies most cases of RHD in the Northern Territory39 and this was confirmed echocardiographically in 2% of our Indigenous cohort. Similarly, the transmission of respiratory pathogens is promoted by household crowding43 and nearly 40% of Indigenous adults were admitted previously with pneumonia. Environmental contamination,24 inadequate sanitation and unhygienic food preparation areas21 contribute to infection with enteric pathogens and S stercoralis. The risks of complicated strongyloidiasis, crusted scabies44 and bronchiectasis13 are further increased by HTLV-1 infection; however, no attempt has been made to control transmission of this virus among Indigenous Australians. These effects are compounded by poor health literacy and Indigenous adults are less likely to engage with a conventional medical paradigm.18 Delays in seeking care for uncomplicated urinary tract infections may therefore contribute to the very high Gram-negative BSI incidence rates reported here.

The retrospective design of this study results in a number of limitations. First, only limited demographic information is collected by ASH and the Indigenous population is relatively mobile. Residents of remote communities, for example, frequently stay in town camps and this is not recorded by ASH. The effects of a town camp residence may therefore be underestimated if large numbers of remote residents acquire infection during these visits. Although the foci of infection were determined by reviewing the results of microbiology and imaging for each presentation, these varied between patients according to the practice of the treating physician. The number of patients with concurrent bacterial infections and medical conditions, such as RHD, may therefore be underestimated. Similarly, seropositivity rates for infections such as HBV and HTLV-1 could only be determined for a subset of patients. A further limitation is the identification of NCDs and previous infections using ICD codes; however, coding errors are unlikely to vary systematically according to ethnicity or place of residence. The use of ICD codes does, however, limit our ability to study factors that are more difficult to define and that might also influence infection risk, such as nutrition and health literacy. Finally, the present study has demonstrated an increased risk of infection and death associated with town camp residence. This occurred despite better access to healthcare relative to remote residents and little difference in crude measures of socioeconomic deprivation.7 For community-acquired BSIs, risk of death was strongly associated with NCDs; however, these conditions did not fully account for the increased risk following a nosocomial BSI. Unmeasured socioeconomic factors might contribute to increased mortality among town camp residents; however, recent research linking health outcomes to perceived racism45 may also be relevant to this marginalised population.

The disease burden among the Indigenous population of central Australia is similar to that of many developing countries where NCD prevalence rates are rising rapidly in a setting of persistently high infection rates.2 46 Recently, the validity of conventional health transition theory has been challenged by findings that infection-related hospitalisation rates are increasing among the most socially disadvantaged community members in a developed country.17 The present study provides a possible explanation for this observation and further suggests that, in contrast to the orderly epidemiological transition envisaged by Omran (1971),1 life expectancy may fall where social deprivation persists in the face of a rising prevalence of NCDs. High BSI incidence rates among Indigenous Australians were associated with a heavy burden of other infections that provide portals of entry for invasive bacterial disease. Improving life expectancy in this setting will require public health initiatives to reduce pathogen exposure in addition to controlling the burgeoning NCD burden. Diabetes, harmful alcohol consumption and organ damage resulting from these conditions increased both the likelihood of infection and the subsequent risk of death. Both conditions are included in proposed international management strategies to control the NCD crisis.37 However, our findings also illustrate the complexity of interactions between communicable diseases and NCDs and support calls for an integrated approach to disease management.47 The intimate association between these conditions and human behaviour renders the empowerment of affected populations to adopt protective health-related strategies critical to the success of any management programme.47

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr S Guthridge, Department of Health Gains Planning, Northern Territory Government, for providing the population data.

Footnotes

Contributors: LE designed the study, collected the data, assisted with the statistical analysis and prepared the manuscript. LF and SJ collected the data, AB assisted in manuscript preparation and RJW was responsible for the statistical analysis and assisted in manuscript preparation.

Funding: This study received funding from the Northern Territory Rural Clinical School, which is an initiative of the Australian Department of Health and Ageing.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data relate to Indigenous Australians and cannot be shared without specific approval from the relevant Indigenous communities and the responsible HREC. Obtaining such approval will require details of all individuals seeking access and each research project for which the inclusion of these data is proposed.

References

- 1.Omran A. A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Mem Fund Q 1971;49:509–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher D, Smeeth L, Sekajugo J. Health transition in Africa: practical policy proposals for primary care. Bull WHO 2010;88:943–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous Health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009;374:65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frenk J, Bobadilla JL, Sepulveda J, et al. Health transition in middle-income countries: new challenges for health care. Health Policy Plann 1989;4:29–39 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heuveline P, Guilllot M, Gwatkin DR. The uneven tide of the health transition. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:313–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations State of the world's indigenous peoples. New York: The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare/Australian Bureau of Statistics The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics catalogue number 4704.0, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Dempsey K. Causes of inequality in life expectancy between indigenous and non-indigenous people in the Northern Territory, 1981–2000: a decomposition study. Med J Aust 2006;184:490–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 census of population and housing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) peoples profile. Catalogue Number 2002.0 Canberra: Australia, 2012. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/communityprofile/IARE701002 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis J, Cheng AC, McMillan M, et al. Sepsis in the tropical top end of Australia's Northern Territory: disease burden and impact on Indigenous Australians. Med J Aust 2011;194:519–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einsiedel L, Woodman RJ. Two Nations: racial disparities in bloodstream infections recorded at Alice Springs Hospital, central Australia, 2001–2005. Med J Aust 2010;192:567–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Grady K, Taylor-Thompson D, Chang A, et al. Rates of radiologically confirmed pneumonia as defined by the World Health Organisation in Northern Territory Indigenous children. Med J Aust 2010;192:592–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einsiedel L, Fernandes L, Spelman T, et al. Bronchiectasis is associated with human T lymphotropic virus 1 infection in an Indigenous Australian population. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einsiedel L, Fernandes L, Woodman R. Racial disparities in infection-related mortality at Alice Springs Hospital, central Australia, 2000–2005. Med J Aust 2008;188:568–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kway M, Rose CE, Fry AM, et al. The influence of chronic illness on the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005;192:377–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi N, Caputo GM, Weitekamp MR, et al. Infections in diabetic patients. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1906–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker M, Barnard LT, Kvalsvig A, et al. Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. Lancet 2012;379:1112–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Einsiedel L, Van Iersel E, Macnamara R, et al. Self-discharge by adult aboriginal patients at Alice Springs Hospital, central Australia: insights from a prospective cohort study. Aust Health Rev 2012;37:239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 Census of population and housing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) Profile. Canberra, 2013. 2002.0. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/lookup/4704.0Chapter218Oct+2010 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skov S, Chikrizhs TN, Li SQ, et al. How much is too much? Alcohol consumption and related harm in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust 2010;193:269–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailie R, Runcie MJ. Household infrastructure in Aboriginal communities and the implications fro health improvement. Med J Aust 2001;175:363–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anaya J. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous peoples, James Anaya, on the situation of indigenous people in Australia. United Nations, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'espaignet E, Kennedy K, Paterson B, et al. Health status in the Northern Territory 1998. Darwin: Epidemiology, Primary Care and Coordinated Care Branch, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald E, Bailie R, Grace J, et al. An ecological approach to health promotion in remote Australian Aboriginal communities. Health Promot Int 2010;25:42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien J, Lu B, Ali NA, et al. Alcohol dependence is independently associated with sepsis, septic shock and hospital mortality among adult intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 2007;35:345–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laupland K, Gregson DB, Zygun DA, et al. Severe blood stream infections: a population-based assessment. Crit Care Med 2004;32:992–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuori J, Butler JC, Farley MM, et al. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med 2000;342:681–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dopirak M, Hill C, Oleksiw M, et al. Surveillance of hemodialysis-associated primary bloodstream infections: the experience of ten hospital-based centers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002;23:721–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Connors C, Wright J, et al. Estimating chronic disease prevalence among the remote Aboriginal population of the Northern Territory using multiple data sources. Aust NZ J Public Health 2008;32:307–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoy W, Davey RL, Sharma S, et al. Chronic disease profiles in remote Aboriginal settings and implications for health services planning. Aust NZ J Public Health 2010;34:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moberley S, Krause V, Cook H, et al. Failure to vaccinate of failure of vaccine? Effectiveness of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine program in Indigenous adults in the Northern Territory of Australia. Vaccine 2010;28:2296–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flory J, Joffe M, Fishman NO, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:717–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong S, Bishop E, Lilliebridge R, et al. Community Associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus in Indigenous Northern Australia: epidemiology and outcomes. J Infect Dis 2009;199:1461–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huggan P, Wells JE, Browne M, et al. Population-based epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in Canterbury, New Zealand. Int Med J 2010;40:117–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagger J, Zindrou D, Taylor KM. Post-operative infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and socioeconomic background. Lancet 2004;363:706–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, et al. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008;372:1661–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. for the Lancet NCD action group and the NCD alliance Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet 2011;377:1438–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailie R, Stevens MR, McDonald E, et al. Skin infection, housing and social circumstances in children liviing in remote Indigenous communities: testing conceptual and methodological approaches. BMC Public Health 2005;128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDonald M, Towers RJ, Andrews RM, et al. Low rates of streptococcal pharyngitis and high rates of pyoderma in Australian Aboriginal communities where acute rheumatic fever is hyperendemic. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:683–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Currie B, Carapetis JR. Skin infections and infestations in Aboriginal communities in northern Australia. Aust J Dermatol 2000;41:139–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hewagama S, Spelman T, Einsiedel L. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia at Alice Springs Hospital, central Australia, 2003–2006. Int Med J 2012;42:505–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carapetis J, Wolff DR, Currie BJ. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in the Top End of Australia's Northern Territory. Med J Aust 1996;164:146–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacoby P, Carvillo K, Hall S, et al. Crowding and other strong predictors of upper respiratory carriage of otitis media related bacteria in Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children. Paed Inf Dis J 2011;30:480–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verdonck K, Gonzalez E, Van Dooren S, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus 1: recent knowledge about an ancient infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2007;7:266–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Priest N, Paradies Y, Stevens M, et al. Exploring relationships between racism, housing and child illness in remote indigenous communities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:440–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boutayeb A, Boutayeb B. The burden of non-communicable diseases in developing countries. INT J Equity in Health 2005;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Maeseneer J, Roberts RG, Demarzo M, et al. Tackling NCDs: a different approach is needed. Lancet 2012;379:1860–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.