Abstract

The bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum has for decades been known to cause the disease tick-borne fever (TBF) in domestic ruminants in Ixodes ricinus-infested areas in northern Europe. In recent years, the bacterium has been found associated with Ixodes-tick species more or less worldwide on the northern hemisphere. A. phagocytophilum has a broad host range and may cause severe disease in several mammalian species, including humans. However, the clinical symptoms vary from subclinical to fatal conditions, and considerable underreporting of clinical incidents is suspected in both human and veterinary medicine. Several variants of A. phagocytophilum have been genetically characterized. Identification and stratification into phylogenetic subfamilies has been based on cell culturing, experimental infections, PCR, and sequencing techniques. However, few genome sequences have been completed so far, thus observations on biological, ecological, and pathological differences between genotypes of the bacterium, have yet to be elucidated by molecular and experimental infection studies. The natural transmission cycles of various A. phagocytophilum variants, the involvement of their respective hosts and vectors involved, in particular the zoonotic potential, have to be unraveled. A. phagocytophilum is able to persist between seasons of tick activity in several mammalian species and movement of hosts and infected ticks on migrating animals or birds may spread the bacterium. In the present review, we focus on the ecology and epidemiology of A. phagocytophilum, especially the role of wildlife in contribution to the spread and sustainability of the infection in domestic livestock and humans.

Keywords: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, ecology, epidemiology, distribution, hosts, vectors

Introduction

The bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum has been known to cause disease in domestic ruminants (Europe) (Foggie, 1951) and horses (USA) (Gribble, 1969) for decades. More recently, the infection has been detected in several mammalian species, including humans, in areas on the northern hemisphere with endemic occurrence of Ixodes ticks. A. phagocytophilum as a bacterial species appears to be a generalist, infecting a wide range of animals. Multiple genetic variants of the bacterium have been characterized (Scharf et al., 2011) and subpopulations within the species are now being discussed. In this review, we present updated information especially concerning the ecology and epidemiology of A. phagocytophilum.

History

During an experimental study on louping-ill (LI) in Scotland last century, some sheep contracted an unknown fever reaction on tick-infested pastures. The fever reaction was transmitted to other sheep by blood inoculation, but gave no protection against a later LI-virus infection. The disease was given the provisional name “tick-borne fever” (TBF), and the responsible pathogen was assumed to belong to the class Rickettsia (Gordon et al., 1932, 1940). The name TBF is still used for the infection in domestic ruminants in Europe. Anecdotally it could be mentioned that the Norwegian synonym of TBF is “sjodogg,” and this name was already used to describe a devastating illness in ruminants as early as year 1780 in a coastal area of western Norway (Stuen, 2003).

The causative agent of TBF was first classified as Rickettsia phagocytophila (Foggie, 1951). However, due to morphological resemblance with Cytoecetes microti, an organism found in the polymorphonuclear cells of the vole Microtus pennsylvanicus (Tyzzer, 1938), it was later suggested to include the TBF agent in the genus Cytoecetes in the tribe Ehrlichia, as C. phagocytophila (Foggie, 1962).

In 1974, the organism was named Ehrlichia phagocytophila in Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology (Philip, 1974). The discovery of E. chaffeensis in 1986, causative agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (Maeda et al., 1987; Anderson et al., 1991), and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) in 1994 (Bakken et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1994), initiated new studies on the host associations, epidemiology and taxonomy of the granulocytic Ehrlichiae (Ogden et al., 1998). Genus Ehrlichia was divided into three genogroups, of which the granulocytic group contained E. phagocytophilum, E. equi [described in horses (Gribble, 1969)] and the agent causing HGE. Later, a reclassification of the genus Ehrlichia was proposed, and based on phylogenetic studies, the granulocytic Ehrlichia group was renamed Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Dumler et al., 2001; Anonymous, 2002) (Table 1). However, it is still argued, whether the granulocytic Anaplasma should eventually be reclassified as distinct from the erythrocytic Anaplasma and returned to the previously published genus, Cytoecetes (Brouqui and Matsumoto, 2007).

Table 1.

Classification of genus Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, and Neorickettsia in the family Anaplasmataceae (modified after Dumler et al., 2001).

| Genus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaplasma | Ehrlichia | Neorickettsia | |

| Species | A. marginale | E. canis | N. risticii |

| A. bovis | E. chaffeensis | N. sennetsu | |

| A. ovis | E. ewingii | ||

| A. phagocytophilum | E. muris | ||

| A. platys | E. ruminantium | ||

Clinical characteristics

Natural infection with A. phagocytophilum has been reported, as already mentioned, in humans and a variety of domestic and wild animal species (Foley et al., 1999), whereas fatal cases have so far only been reported in sheep, cattle, horses, reindeer, roe deer, moose, dogs, and humans (Jenkins et al., 2001; Stuen, 2003; Franzén et al., 2007; Heine et al., 2007).

The main disease problems associated with TBF in ruminants are seen in young animals, and individuals purchased from tick-free areas and placed on tick-infested pastures for the first time. The most characteristic symptoms in domestic ruminants are high fever, anorexia, dullness, and sudden drop in milk yield (Tuomi, 1967a). However, the fever reaction may vary according to the age of the animals, the variant of A. phagocytophilum involved, the host species and immunological status of the host (Foggie, 1951; Tuomi, 1967b; Woldehiwet and Scott, 1993; Stuen et al., 1998). Abortion in ewes and reduced fertility in rams have also been reported. In addition, reduced weight gain in A. phagocytophilum infected bullocks and lambs have been observed (Taylor and Kenny, 1980; Stuen et al., 1992; Grøva et al., 2011).

A variable degree of clinical symptoms have also been detected in other mammals, such as fever, anorexia, depression, apathy, distal edema, reluctance to move, and petechial bleedings in horses, while the symptoms in dogs are characterized by fever, depression, lameness, and anorexia. In cats the predominant signs are anorexia, lethargy, hyperesthesia, conjunctivitis, myalgia, arthralgia, lameness, and incoordination (Egenvall et al., 1997; Bjöersdorff et al., 1999; Cohn, 2003; Franzén et al., 2005; Heikkilä et al., 2010).

In humans, clinical manifestations range from mild self-limiting febrile illness, to fatal infections. Commonly, patients express non-specific influenza-like symptoms with fever, headache, myalgias, and malaise (Bakken et al., 1994; Dumler, 1996). In addition, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, anemia, and increased aspartate and alanine aminotransferase activity in sera are reported (Bakken and Dumler, 2008). However, most human infections probably result in minimal or no clinical manifestations. Reports from the US, indicate a hospitalization rate of 36%, of which 7% need intensive care, while the case fatality rate is less than 1% (Dumler, 2012). A recent cohort study from China however, describes a mortality of 26.5% (22/83) in hospitalized patients (Li et al., 2011).

Diagnostic and laboratory methods

Clinical signs

Clinical signs in ruminants may be sudden onset of high fever (>41°C) and drop in milk yield, while symptoms in horses, dogs, and cats may be more vague and unspecific. In humans, a flu-like symptom 2–3 weeks after tick exposure is an indicator of infection. However, laboratory confirmation is required to verify the diagnosis (Woldehiwet, 2010). To our knowledge, chronic infection has not yet been confirmed in any host, although persistent infections have been found to occur in several mammalian species.

Direct identification

Light microscopy of blood smears taken in the initial fever period is normally sufficient to state the diagnosis. Stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa, the organisms appear as blue cytoplasmic inclusions in monocytes and granular leucocytes, especially neutrophils (Foggie, 1951). Electron microscopy may also confirm the diagnosis of acute Anaplasma infection in blood or organs. Single or multiple organisms are then identified in clearly defined cytoplasmic vacuoles (Tuomi and von Bonsdorff, 1966; Rikihisa, 1991). Immuno-histochemistry on tissue samples could also be performed to confirm the diagnosis (Lepidi et al., 2000).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cultivation

Several PCR techniques (conventional, nested, and real-time) for the identification of A. phagocytophilum infection in blood and tissue samples have been established primarily on basis of the 16S rRNA, groEL, and p44 genes (Chen et al., 1994; Courtney et al., 2004; Alberti et al., 2005a). Multiple variants of A. phagocytophilum have been genetically characterized. Identification and stratification into phylogenetic subfamilies have been based on cell culturing, experimental infections, PCR and sequencing techniques (Dumler et al., 2007). Cultivation of A. phagocytophilum in cell cultures has been described for variants isolated from human, dog, horse, roe deer, and sheep (Goodman et al., 1996; Munderloh et al., 1999; Bjöersdorff et al., 2002; Woldehiwet et al., 2002; Silaghi et al., 2011c).

Serology

The presence of specific antibodies may support the diagnosis. A complement fixation test, counter-current immunoelectrophoresis test and an indirect immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test can be used (Webster and Mitchell, 1988; Paxton and Scott, 1989). Several ELISA tests have also been developed (Ravyn et al., 1998; Magnarelli et al., 2001; Alleman et al., 2006; Woldehiwet and Yavari, 2012). A SNAP®4Dx® ELISA test is commercially available for rapid in-house identification of A. phagocytophilum antibodies in dog serum, but the kit has also been used successfully on horse and sheep sera (Granquist et al., 2010a; Hansen et al., 2010).

Pathology

An enlarged spleen, up to 4–5 times the normal size with subcapsular bleedings, has for decades been regarded as indicative of TBF in sheep (Gordon et al., 1932; Øverås et al., 1993). No other typical pathological changes have been described (Munro et al., 1982; Campbell et al., 1994; Lepidi et al., 2000). An enlarged spleen with subcapsular bleedings has also been observed in roe deer and reindeer (Stuen, 2003).

Relative sensitivity of the diagnostic tests used for laboratory diagnostic confirmation of A. phagocytophilum infection in humans is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relative sensitivity of diagnostic tests for A. phagocytophilum infection in humans (modified after Bakken and Dumler, 2006).

| Duration of illness (days) | Blood smear microscopy | HL-60 cell culture | PCR | IFAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–7 | Medium | Medium | High | Low |

| 8–14 | Low | Low | Low | Medium |

| 15–30 | Low | High | ||

| 31–60 | High | |||

| >60 | High |

Treatment, prevention, and control

The drug of choice is tetracycline (Woldehiwet and Scott, 1993; Dumler, 1996). Doxycyclin hyclate, given orally or intravenously, has been effective in treating clinical cases of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and has led to clinical improvement in 24–48 h. In human patients, treated with doxycycline for 7–10 days, infections have resolved completely and relapses have never been reported. In patients at risk of adverse drug reactions, rifampin therapy should be considered (Bakken and Dumler, 2006).

Current disease prevention strategies in domestic animals are based on the reduction of tick infestation by chemical acaricides, for instance at turn out on tick pasture. This is mostly done be dipping or with a variety of pour-on applications (Woldehiwet and Scott, 1993; Stuen, 2003). This treatment has to be repeated during the tick season. In the UK, long-acting tetracycline has also been used as a prophylactic measure given before animals are moved from tick-free environment into tick-infested pasture (Brodie et al., 1986; Woldehiwet, 2007). However, there is a growing concern about the environmental safety and human health, increasing costs of chemical control and the increasing resistance of ticks to pesticides (Samish et al., 2004).

Biological tick control is becoming an attractive approach to tick management. Biological control of tick infestations has been difficult because ticks have few natural enemies. Studies so far have concentrated of bacteria, entomopathogenic fungi, and nematodes (Samish et al., 2004). However, the main challenge is to create a sustainable biological control of ticks in the natural habitat.

Vaccines against A. phagocytophilum are not yet available. Several vaccine candidates have been suggested, but the development of an effective vaccine has so far been difficult (Ijdo et al., 1998; Herron et al., 2000; Ge and Rikihisa, 2006). In order to develop a vaccine, one challenge is to choose antigens that are conserved among all variants of A. phagocytophilum.

Vaccines against ticks are also an alternative option. The development of vaccines that target both ticks and pathogen transmission may provide a mean of controlling tick-borne infections through immunization of the human and animal population at risk or by immunization of the mammalian reservoir to minimize pathogen transmission (de la Fuente and Kocan, 2006). Gut-, salivary-, or cement antigen vaccines (recombinant Bm/Ba 86, Bm91, and 64TRP) have been tested, and TickGUARDPLUS and Gavac (both recombinant Bm86) are examples of commercially available vaccines from the early 1990's (Willardsen, 2004; Labuda et al., 2006; de la Fuente et al., 2007; Canales et al., 2009). Other vaccines that inhibit subolesin expression are now being tested. These vaccines cause degeneration of gut, salivary gland, reproductive -and embryonic tissues and causes sterility in male ticks (de la Fuente et al., 2006a,b,c). Tick vaccines are feasible control methods, cost-effective and environmentally friendly compared to chemical control (de la Fuente and Kocan, 2006).

Transmission and colonization

A. phagocytophilum has, as its name implies, a partiality to phagocytic cells and is one of very few bacteria known to survive and replicate within neutrophil granulocytes (Choi et al., 2005). During tick feeding, neutrophil-associated-inflammatory-responses are modulated by various stimuli deployed by the tick sialome components (Beaufays et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2009; Heinze et al., 2012). Orchestration of vector—and bacterial interactions with the defensive mechanisms of the host animal seem to promote infection and transmission rather than controlling it, resulting in increased availability of infected cells in the circulating blood and at the site of tick bite (Choi et al., 2003, 2004; Granquist et al., 2010b; Chen et al., 2012). The low level of circulating organisms, detected between periods of bacteremia (Granquist et al., 2010c), may indicate temporary clearance of infected cells, possible margination of infected granulocytes to endothelial surface or immunologically modified intervals in generations of antigenically different organisms (Bakken et al., 1994; Beninati et al., 2006; Granquist et al., 2008). Because of the short-lived nature of circulating neutrophils, the role of these cells in establishing and maintaining infection has been questioned (Herron et al., 2005), however to date little is known about alternative cellular components involved in the invasion and colonization of A. phagocytophilum in the host organism (Granick et al., 2008).

A. phagocytophilum modulates the distribution of potential host cells and infected neutrophils, by inducing cytokine secretion and their receptors (Akkoyunlu et al., 2001; Scorpio et al., 2004) and promoting the loss of CD162 and CD62L (Choi et al., 2003). The bacterium further interacts with host cell ligands (Park et al., 2003; Granick et al., 2008), by surface exposed proteins known as adhesins (Yago et al., 2003; Ojogun et al., 2012) in order to facilitate internalization in the host cell (Wang et al., 2006).

The translocation of bacteria to the inside of host cells is receptor mediated and depending on transglutaminase activity (reviewed by Rikihisa, 2003). However, host cell specific differences to receptors and their components as well as their importance in the infection process seem to exist, which may explain why certain bacterial strains, e.g., ruminant Ap Variant 1 strain, are refractory to culture in commercially available cell lines (like the HL-60 cell line) (Carlyon et al., 2003; Herron et al., 2005; Reneer et al., 2006, 2008; Massung et al., 2007). Previous reports have shown that various tissues and cells are susceptible to infection by A. phagocytophilum (Klein et al., 1997; Munderloh et al., 2004). It has been shown that intravascular myeloid cells (mature) have a higher infection rate than cells located in the bone marrow which may indicate that precursor stages of myeloid cells express ligands different from mature neutrophils, thus being more refractory to binding and internalization of the organism (Bayard-Mc Neeley et al., 2004). The coincidence that A. phagocytophilum uses CD162 when infecting neutrophils, led to the hypothesis that endothelium may have a function in the pathogenesis of A. phagocytophilum infection in vivo (Herron et al., 2005). However, a field study of skin biopsies in sheep observed A. phagocytophilum in inflammatory cell infiltrates comprised of PMNs and macrophages in the dermis and subcutis, and occasionally restricted to the mid- and peripheral parts of the blood vessel walls during tick attachment, thus questioning the role of endothelium in the pathogenesis of A. phagocytophilum infection in in the earliest phases of tick bite inoculation (Granquist et al., 2010b). Interestingly A. phagocytophilum has the ability to delay host cell apoptosis by activation of an anti-apoptosis cascade (Sarkar et al., 2012). This is critical for intracellular survival and reproduction of A. phagocytophilum in the normally short lived neutrophil granulocytes (Yoshiie et al., 2000; Lee and Goodman, 2006). Unlike other Gram-negative bacteria, A. phagocytophilum lacks lipopolysaccharides and peptidoglycans, but compensates for the loss of membrane integrity by incorporation of cholesterol which allows the escape of Nod Like Receptor and Toll Like Receptor activation pathways to successfully infect vertebrate immune cells (Lin and Rikihisa, 2003a,b; Hotopp et al., 2006; Xiong et al., 2007). However, recent studies in mice have surprisingly shown that alternative pathways involving the Nod 1 and 2 associated receptor interacting protein 2 may be important in control and clearance of A. phagocytophilum infection (Sukumaran et al., 2012).

Persistence

A. phagocytophilum has been found to persist in several mammalian hosts, such as sheep, dog, cattle, horses, and red deer (Foggie, 1951; Egenvall et al., 2000; Stuen, 2003; Larson et al., 2006; Franzén et al., 2009). However, this may vary according to the variants of the bacterium involved.

The ability of A. phagocytophilum to persist in immune-competent hosts between seasons of tick activity is a complex and coordinated interaction that through evolutionary steps, have left the genomes of A. phagocytophilum and related organisms, heavily reduced to comprise essential genes allowing for nearly infinite numbers of recombined antigens and macromolecular exchange with its host cell (Rikihisa, 2011; Rejmanek et al., 2012).

Cyclic bacteremias display as periodic peaks containing genetically distinct variants of major surface proteins (MSP) (Granquist et al., 2008, 2010a). The capacity to generate novel antigens when other organisms are already present (superinfection) results in persistence and maintenance of the organism in natural transmission cycles and possibly allows spatial spread in nature (Barbet et al., 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2005; Futse et al., 2008; Ladbury et al., 2008; Stuen et al., 2009). Variants of MSPs such as MSp2 (or P44) contain epitopes recognized by antibodies appearing subsequently, but not prior to the respective peaks of rickettsemia in which they are expressed (Barbet et al., 2003; Granquist et al., 2010c), indicating a true process of antigenic variation influenced by the host immune response. Sequence variation may be achieved by segmental gene conversion of a single polycistronic expression site by insertion of total or partial pseudogene sequences (Barbet et al., 2000; Granquist et al., 2008) with the possible formation of mosaics or chimeras (Rejmanek et al., 2012). The large repertoire of donor sequences in A. phagocytophilum suggests that this bacterium may however only require simple gene conversion to evade host immune surveillance (Lin et al., 2003). On the other hand, the close proximity of the partial recombinase gene, recA, which is commonly involved in homologous recombinations supports the theory that recombination of pseudogenes by insertion in the expression site occurs (Barbet et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2003).

Vectors and competent vectors of A. phagocytophilum

A. phagocytophilum is transmitted by hard ticks of the I. persulcatus-complex. The main vector in Europe is I. ricinus (commonly known as sheep tick or castor been tick); in the Eastern US I. scapularis (deer tick or black-legged tick); in the Western US I. pacificus (Western black-legged tick), and in Asia I. persulcatus (taiga tick) (Woldehiwet, 2010). Vector competence has been proven for the American tick species I. scapularis (previously I. dammini), I. pacificus, and I. spinipalpis (Telford et al., 1996; Des Vignes et al., 1999; Zeidner et al., 2000; Teglas and Foley, 2006). Transovarial transmission has not been proven in Ixodes species, but in Dermacentor albipictus, which lifecycle involves a single host animal, representing a distinct ecological niche (Baldridge et al., 2009). As to current knowledge, a vertebrate reservoir host is necessary in nature for keeping the endemic cycle.

Prevalence data on molecular detection of A. phagocytophilum in questing ticks, show great variations within countries or continents where such studies have been performed. The infection rate in I. scapularis ranges from <1% up to 50% and in I. pacificus from <1% up to ~10% in the US. Additionally, A. phagocytophilum has been detected in questing I. dentatus, Amblyomma americanum, Dermacentor variabilis, and D. occidentalis (Table 4; Goethert and Telford, 2003). In Asia, detection rates varied in I. persulcatus between <1% up to 21.6% and questing I. ovatus, I. nipponensis, D. silvarum, Haemaphysalis megaspinosa, H. douglasii, H. longicornis, and H. japonica also contained DNA of A. phagocytophilum (Table 5). The greatest number of studies has been performed on questing I. ricinus ticks in Europe, where the prevalence rates vary between and also within countries. On average, the A. phagocytophilum-prevalence in I. ricinus in Europe ranges between <1% and ~20%, in I. persulcatus-endemic areas in Eastern Europe between 1.7 and 16.7%, and additionally DNA of A. phagocytophilum has been detected in questing D. reticulatus, H. concinna, and I. ventalloi (Table 3). Detailed information on worldwide prevalence rates of A. phagocytophilum in unfed ticks from the vegetation can be found in Tables 3–5.

Table 4.

Molecular prevalence studies of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing ticks in the USA*.

| State | Tick species | Year of tick collection | No. of ticks | Prevalence in % | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | Ixodes scapularis | 2007 | 509 | 0.2e | PCR | Walk et al., 2009 |

| Rhode Island | I. scapularis | 1996–1999 | 538 | 22.9 | nPCRa | Massung et al., 2002 |

| Connecticut | I. scapularis | 1994 | 120 | 50.0 | PCRa | Magnarelli et al., 1995 |

| 1996–1997 | 1115 | 1.2–19.0e | PCRa | Levin et al., 1999 | ||

| 1996–1999 | 375 | 13.3 | nPCRa | Massung et al., 2002 | ||

| New York | I. scapularis | 2003–2004 | 25females | 40.0 | nPCRc | Moreno et al., 2006 |

| 32males | 50.0 | |||||

| 62nymphs | 27.0 | |||||

| New Jersey | I. scapularis | 2001 | 107 | 1.9 | PCRa | Adelson et al., 2004 |

| Pennsylvania | I. scapularis | 2005 | 94 | 1.1 | PCRa | Steiner et al., 2008 |

| Wisconsin | I. scapularis | 1998 | 636 | 3.8 | PCRa | Shukla et al., 2003 |

| 2006 | 100 | 14 | nPCRa | Steiner et al., 2008 | ||

| 2008 | 201 | 12.0 | qPCRb | Lovrich et al., 2011 | ||

| Indiana | I. scapularis | 2003 | 68 | 11.8 | nPCRa | Steiner et al., 2006 |

| 2004 | 100 | 5 | nPCRa | Steiner et al., 2008 | ||

| Maine | I. scapularis | 2003 | 100 | 16 | nPCRa | Steiner et al., 2008 |

| Maryland | I. scapularis | 2003 | 348 | 0.3 | PCRa | Swanson and Norris, 2007 |

| Florida | I. scapularis | 2004–2005 | 236 | 1.3 | PCRb | Clark, 2012 |

| Amblyomma americanum | 2004–2005 | 223 | 2.7 | PCRb | Clark, 2012 | |

| Georgia | I. scapularis | 2004–2005 | 808 | 20.0 | nPCRd | Roellig and Fang, 2012 |

| California | Ixodes pacificus | 1995–1996 | 1112adults, f | 0.8 | nPCRa | Barlough et al., 1997a |

| 47nymphs, f | 2.1 | |||||

| 1997 | 84 | 1.2e | PCRc | Nicholson et al., 1999 | ||

| 1996–1997 | 401f | 2.0 | nPCRa | Kramer et al., 1999 | ||

| 1998 | 465adults | 0 | PCRa | Lane et al., 2001 | ||

| 202nymphs | 9.9 | |||||

| 2000–2001 | 776 | 6.2 | PCRb | Holden et al., 2003 | ||

| 2002 | 234 | 3.4 | nPCRa | Lane et al., 2004 | ||

| 2000–2001 | 168 | 3.0 | PCRb | Holden et al., 2006 | ||

| 2005–2007 | 138 | 2.2e | qPCRb | Rejmanek et al., 2011 | ||

| Dermacentor variabilis | 2000–2001 | 58 | 8.6 | PCRb | Holden et al., 2003 | |

| D. occidentalis | 2000–2001 | 353 | 1.1 | PCRb | Holden et al., 2003 | |

| 2003–2005; 2009–2010 | 513 | 0.2 | nPCRa | Lane et al., 2010 |

This table does not claim completeness. It does not include studies with 0% prevalence and studies with mixed results for questing and engorged ticks.

nPCR, nested PCR; qPCR, real-time PCR; n.s., not specified.

16S rRNA as gene target.

Msp2 as gene target.

GroESL as gene target.

AnkA as gene target.

Calculated by the authors of the present manuscript.

Study includes pools.

Table 5.

Molecular prevalence studies of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing ticks in Asia*.

| Country | Tick species | Year of tick collection | No. of ticks | Prevalence in % | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russia | Ixodes persulcatus | 2003–2004 | 125 | 2.4 | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2005 |

| 2002 | 8 | 12.5 | PCRa | Shpynov et al., 2006 | ||

| 2003–2010 | 3751 | 3.0 | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | ||

| China | I. persulcatus | 1997 | 372d | 0.8* | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2000 |

| 1999–2001 | 1345 | 4.6 | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2003 | ||

| 2005 | 100 | 4.0 | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2006 | ||

| Dermacentor silvarum | 2005 | 286 | 0.7 | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2006 | |

| Japan | I. persulcatus | n.s. | 325 | 6.2 | PCRb | Murase et al., 2011 |

| 2010–2011 | 134 | 21.6f | nPCRa | Ybañez et al., 2012 | ||

| Haemaphysalis megaspinosa | 2008 | 48 | 12.5 | nPCRa | Yoshimoto et al., 2010 | |

| H. douglasii | 2011 | 35 | 6.3f | nPCRc | Ybañez et al., 2013 | |

| I. persulcatus, I. ovatus | n.s. | 130 | 4.6e | nPCRb | Wuritu et al., 2009 | |

| Korea | H. longicornis | 2004 | 241d | 1.1 | nPCRa | Chae et al., 2008 |

| I. nipponensis | 2004 | 5male | 20 | nPCRa | Chae et al., 2008 |

This table does not claim completeness. It does not include studies with 0% prevalence and studies with mixed results for questing and engorged tick.

nPCR, nested PCR; n.s., not specified.

16S rRNA gene as target.

Msp2 gene as target.

GroEL gene as target.

Study includes pools.

I. persulcatus and I. ovatus.

Total prevalence not specified in the paper, prevalence was calculated by the authors of the present manuscript.

Table 3.

Molecular prevalence studies of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing ticks in Europe*.

| Country | Tick species | Year of tick collection | No. of ticks | Prevalence in % | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | Ixodes spp. | 1998–1999 | 341 | 2.1g | PCRa | Jenkins et al., 2001 |

| Norway | Ixodes ricinus | 200 | 8.5 | |||

| 257 | 17.1 | |||||

| 2006–2008i | 145 | 3.4 | qPCRb | Rosef et al., 2009 | ||

| 235 | 0.4 | |||||

| 348 | 14.9 | |||||

| 2006 | 224 | 4.5 | qPCRb | Radzijevskaja et al., 2008 | ||

| 2011 | 87adults | 4.6 | qPCRb | Soleng and Kjelland, 2013 | ||

| 133nymphs | 0.8 | |||||

| Sweden | I. ricinus | n.s. | 151nymphs | 6.6 | PCRa | von Stedingk et al., 1997 |

| 2007 | 1245h | 11.5 | qPCRb | Severinsson et al., 2010 | ||

| Denmark | I. ricinus | 1999–2000 | 106 | 23.6 | PCRa | Skarphedinsson et al., 2007 |

| Estonia | I. ricinus | 2000 | 100 | 3 | qPCRa | Mäkinen et al., 2003 |

| 2006–2008 | 2474 | 1.7 | qPCRb | Katargina et al., 2012 | ||

| 2008–2010 | 112 | 2.7 | nPCRa | Paulauskas et al., 2012 | ||

| I. persulcatus | 2008–2010 | 31 | 6.5 | nPCRa | Paulauskas et al., 2012 | |

| Latvia | I. ricinus | 2008–2010 | 99 | 3.0 | nPCRa | Paulauskas et al., 2012 |

| I. persulcatus | 2008–2010 | 58 | 1.7 | nPCRa | Paulauskas et al., 2012 | |

| Lithuania | I. ricinus | 2006 | 140 | 3 | qPCRb | Radzijevskaja et al., 2008 |

| 2008–2010 | 277 | 2.9 | nPCRa | Paulauskas et al., 2012 | ||

| D. reticulatus | 2008–2010 | 87 | 8.0 | nPCRa | Paulauskas et al., 2012 | |

| Russia | I. ricinus | 1997–1998 | 295 | 13.6g | PCRa, RLB | Alekseev et al., 2001a |

| 2002 | 80 | 8.8 | nPCRb | Masuzawa et al., 2008 | ||

| 2006–2008 | 82 | 13.4 | qPCRb | Katargina et al., 2012 | ||

| I. persulcatus | 2002 | 84 | 16.7 | qPCRb | Eremeeva et al., 2006 | |

| 2002 | 119 | 2.5 | nPCRb | Masuzawa et al., 2008 | ||

| Poland | I. ricinus | 2000 | 424 | 19.2 | PCRa | Stanczak et al., 2002 |

| 1999 | 533 | 4.5 | PCRa | Skotarczak et al., 2003 | ||

| 2001 | 701 | 14 | PCRa | Stanczak et al., 2004 | ||

| n.s. | 694 | 13.1 | PCRa | Tomasiewicz et al., 2004 | ||

| 2002 | 174 | 4.6 | PCRa | Rymaszewska, 2005 | ||

| 2002 | 73 | 4.1 | PCRb | Skotarczak et al., 2006 | ||

| 2000–2004 | 1474 | 14.1 | PCRa | Grzeszczuk and Stanczak, 2006 | ||

| 2005 | 684 | 10.2 | PCRaPCRc | Chmielewska-Badora et al., 2007 | ||

| 2.8 | ||||||

| 2004–2006 | 1620h | 4.9 | PCRa | Wójcik-Fatla et al., 2009 | ||

| 2007–2008 | 1123h | 8.5 | PCRa | Sytykiewicz et al., 2012 | ||

| n.s. | 40 | 2.5 | PCRb | Richter and Matuschka, 2012 | ||

| Slovakia | I. ricinus | 2002 | 60 | 8.3 | PCRa | Derdáková et al., 2003 |

| 2003–2004 | 271 | 4.4 | PCRa | Smetanová et al., 2006 | ||

| 2006 | 68 | 4.4g | PCRa | Špitalská et al., 2008 | ||

| n.s. | 180 | 1.1 | PCRe | Derdáková et al., 2011 | ||

| 102 | 7.8 | |||||

| n.s. | 80 | 8 | qPCRd | Subramanian et al., 2012 | ||

| Belarus | I. ricinus | 2006–2008 | 187 | 4.2 | qPCRb | Katargina et al., 2012 |

| 2009 | 453 | 2.6 | nPCRf | Reye et al., 2013 | ||

| Ukraine | I. ricinus | 2006 | 84 | 3.6 | PCRa | Movila et al., 2009 |

| Moldova | I. ricinus | 2005 | 198 | 9 | PCRa | Koèi et al., 2007 |

| 2006 | 156 | 5.1 | PCRa | Movila et al., 2009 | ||

| Bulgaria | I. ricinus | 2000 | 112adults | 33.9 | PCRc | Christová et al., 2001 |

| 90nymphs, h | 2.2 | |||||

| Hungary | I. ricinus | 2006–2008 | 1800h | 0.4 | nPCRa | Egyed et al., 2012 |

| Serbia | I. ricinus | 2001–2004 | 287 | 13.9 | nPCRb | Tomanovic et al., 2010 |

| 2007–2009 | 27 | 3.7g | PCRa | Tomanovic et al., 2013 | ||

| D. reticulatus | 2007–2009 | 53 | 1.9g | PCRa | Tomanovic et al., 2013 | |

| Haemaphysalis concinna | 2007–2009 | 35 | 2.9g | PCRa | Tomanovic et al., 2013 | |

| Slovenia | I. ricinus | 1996 | 93 | 3.2 | PCRa | Petrovec et al., 1999 |

| I. ricinus | 2005–2006 | 442h | 0.6 | PCR, nPCRa,f | Smrdel et al., 2010 | |

| UK (Scotland) | I. ricinus | 1996–1997 | 210h | 0.27–2.0 | PCRa | Alberdi et al., 1998 |

| 1996–1999 | 1476 | 3.0 | PCRa | Walker et al., 2001 | ||

| UK (Wales) | I. ricinus | n.s. | 60 | 7.0 | nPCRa | Guy et al., 1998 |

| UK (England) | I. ricinus | n.s. | 44adults | 9 | nPCRa | Ogden et al., 1998 |

| 65nymphs | 6 | |||||

| I. ricinus | n.s. | 70adults | 1.4 | nPCRa | Ogden et al., 1998 | |

| 70nymphs | 1.4 | |||||

| I. ricinus | 2004–2005 | 4256nymphs | 0.7 | qPCRb | Bown et al., 2009 | |

| 263females | 3.4 | |||||

| 321males | 2.5 | |||||

| The Netherlands | I. ricinus | 2000–2004 | 704 | 0.6 | PCRa, RLB | Wielinga et al., 2006 |

| Belgium | I. ricinus | 2010 | 625 | 3.0 | qPCRa, j | Lempereur et al., 2012 |

| Luxembourg | I. ricinus | 2007 | 1394 | 1.9 | PCRf | Reye et al., 2010 |

| France | I. ricinus | 2003 | 4701h | 15 | PCRa | Halos et al., 2006 |

| 2004 | 1065nymphs | 0.4 | PCRa | Ferquel et al., 2006 | ||

| 171adults | 1.2 | |||||

| 2003 | 123males | 4.3–9.4 | nPCRa | Halos et al., 2010 | ||

| 102females | 2.2–10.7 | |||||

| 3480nymphs, h | 1.7–2.6 | |||||

| 2006–2007 | 572 | 0.3 | PCRa | Cotté et al., 2010 | ||

| 2008 | 131 | 1.5 | PCRa | Reis et al., 2011 | ||

| Germany | I. ricinus | 1999 | 492 | 1.6 | PCRa | Fingerle et al., 1999 |

| 2002 | 1963 | 2.6–3.1 | nPCRa | Oehme et al., 2002 | ||

| 2003 | 305 | 2.3 | PCRa | Hildebrandt et al., 2002 | ||

| 1999–2001 | 5424 | 1.0 | nPCRa | Hartelt et al., 2004 | ||

| 2003 | 127 | 3.9 | PCRa, RLB | Pichon et al., 2006 | ||

| 2006 | 2862 | 2.9 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2008 | ||

| 2006–2007 | 1000 | 5.4 | PCRa | Hildebrandt et al., 2010b | ||

| 2005 | 1646 | 3.2 | qPCRb | Schicht et al., 2011 | ||

| 2009–2010 | 5569 | 9.0g | qPCRb | Schorn et al., 2011 | ||

| n.s. | 542 | 4.1 | PCRb | Richter and Matuschka, 2012 | ||

| 2009i | 539 | 8.7 | ||||

| 128 | 9.4 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2012b | |||

| 115 | 17.4 | |||||

| 2011–2012 | 4064 | 5.3g | qPCRb | Overzier et al., 2013b | ||

| Austria | I. ricinus | 2000–2001 | 235 | 5.1 | PCRa | Sixl et al., 2003 |

| n.s. | 880 | 8.7 | qPCRf | Polin et al., 2004 | ||

| Switzerland | I. ricinus | n.s. | 100 | 2 | qPCRa | Leutenegger et al., 1999 |

| 1998 | 1667 | 1.3 | qPCRa | Pusterla et al., 1999 | ||

| 1998 | 417 | 1.4 | nPCRa | Liz et al., 2000 | ||

| 1999 | 6071h | 1.2 | qPCRa | Wicki et al., 2000 | ||

| 2008 | 100nymphs | 2 | qPCRb | Burri et al., 2011 | ||

| 2009–2010 | 1476 | 1.5 | qPCRb | Lommano et al., 2012 | ||

| Italy | I. ricinus | n.s. | 86 | 24.4 | PCRa | Cinco et al., 1997 |

| 2002 | 1014 | 9.9 | nPCRa | Mantelli et al., 2006 | ||

| 2000–2001 | 1931 | 4.4 | PCRa | Piccolin et al., 2006 | ||

| 1998 | 55h | 9 | PCR | Lillini et al., 2006 | ||

| 2010 | 232 | 8.2 | qPCRb | Aureli et al., 2012 | ||

| 2006–2008 | 193 | 1.5 | qPCRb | Capelli et al., 2012 | ||

| Spain | I. ricinus | 2004 | 104nymphs | 8.6 | PCRa | Portillo et al., 2005 |

| 54adults | 3.7 | |||||

| 2005–2006 | 168 | 10.7 | nPCRa | Portillo et al., 2011 | ||

| 2004 | n.s. | 20.5 | PCRa | Ruiz-Fons et al., 2012 | ||

| Portugal | n.s. | Archival collection | 300 | 0.3 | nPCRf | de Carvalho et al., 2008 |

| I. ricinus | 2003–2004 | 142h | 4.0 | PCRa,b PCRb | Santos et al., 2004 | |

| n.s. | 101 | 6.9 | Richter and Matuschka, 2012 | |||

| I. ventalloi | 2003–2004 | 93h | 2.0 | PCRa,b | Santos et al., 2004 | |

| Turkey European and Asian part) | I. ricinus | 2008 | 241 | 2.7–17.5i | nPCRa,b | Sen et al., 2011 |

This table does not claim completeness. It does not include studies with 0% prevalence and studies with mixed results for questing and engorged tick.

nPCR, nested PCR; qPCR, real-time PCR; RLB, reverse line blot; n.s., not specified.

16S rRNA as gene target.

Msp2 as gene target.

AnkA as gene target.

ApaG as gene target.

Msp4 as gene target.

GroEL as gene target.

Total prevalence not specified in the paper, prevalence was calculated by the authors of the present manuscript.

Study includes pools

From different locations

Commercial kit.

Based on molecular detection in questing ticks, A. phagocytophilum seems to appear in all countries across Europe. In the US, the majority of studies have been performed in Eastern and Western (California) parts. From Northern US such data are lacking for several geographical regions, however serological evidence indicate exposure to A. phagocytophilum in large parts of the continent (Dugan et al., 2006; Bowman et al., 2009; Villeneuve et al., 2011). Two recent studies revealed the presence of A. phagocytophilum in questing ticks also in the Southern US (Florida and Georgia) (Clark, 2012; Roellig and Fang, 2012). Only few studies have been carried out in Asia, namely in Russia, China, Japan, and Korea (Table 5). It seems likely that other parts of Asia also belong to the endemic area of this pathogen.

Additionally to the ticks mentioned above, molecular detections have been reported from the following tick species (collected engorged from animals): I. hexagonus, I. trianguliceps, I. spinipalpis, I. ochotonae, and D. nutalli (Zeidner et al., 2000; Bown et al., 2003; Foley et al., 2011; Yaxue et al., 2011; Silaghi et al., 2012a). However, the vector competence of a lot of the tick species in which A. phagocytophilum has been detected as well as their contribution to the endemic cycle of A. phagocytophilum remain to be investigated.

The tick species I. ricinus, I. persulcatus, I. scapularis, and I. pacificus are found ubiquitously in their distribution range, have an open questing behavior and a broad host range, including many mammalian species (Sonenshine, 1993). These tick species may consequently also transmit the bacterium from animal reservoir hosts to humans. Aside from these aforementioned antropophilic and exophilic ticks, the involvement of nidicolous, and more host-specific endophilic ticks have been discussed in the context of so-called niche cycles, which may additionally keep the infection in nature. Examples for such proposed niche cycles involve cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), I. dentatus and I. scapularis in the US (Goethert and Telford, 2003); field voles (Microtus agrestis), I. trianguliceps and I. ricinus in the UK (Bown et al., 2003); and hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), I. hexagonus and I. ricinus in Europe (Silaghi et al., 2012a). The mentioned animals harbor two to three developmental stages of both endophilic and exophilic tick species and can thus transmit the agent from the animal host to humans via the anthropophilic tick species. Considering the large number of host specific and/or nidicolous ticks all around the world, it is likely that more potential niche cycles will be uncovered in the future (Foley et al., 2011).

Due to the comparatively low prevalence of A. phagocytophilum in I. pacificus in the Western US, I. spinipalpis has been suggested as a bridging vector for HGA (Zeidner et al., 2000). This nidiculous tick species infests, among others, Mexican woodrats (Neotoma mexicana) (in which A. phagocytophilum DNA has also been detected) and also occasionally bites humans and may thus transmit the agent from zooendemic cycles to humans.

Infection rates reported in many studies are higher in adult ticks than in nymphs. Due to the transstadial transmission, but lack of transovarial transmission, larvae are considered free of A. phagocytophilum. Adult ticks have had an additional blood meal in comparison to nymphs, and thus twice the chance of acquiring the infection. Variations in prevalence in questing ticks have also been observed with regard to the year of collection and in-between study areas and different geographic locations (Levin et al., 1999; Wicki et al., 2000; Hildebrandt et al., 2002; Cao et al., 2003; Holman et al., 2004; Ohashi et al., 2005; Grzeszczuk and Stanczak, 2006; Wielinga et al., 2006; Silaghi et al., 2008, 2012b; Schorn et al., 2011; Overzier et al., 2013b).

When looking at these variations, it has to be taken into account, that variations can be due to local variations, such as habitat structure or host availability, variation in methodology and sampling approach. Most studies shown in Tables 3–5 are single studies providing a spot prevalence, while studies including longitudinal data are scarce.

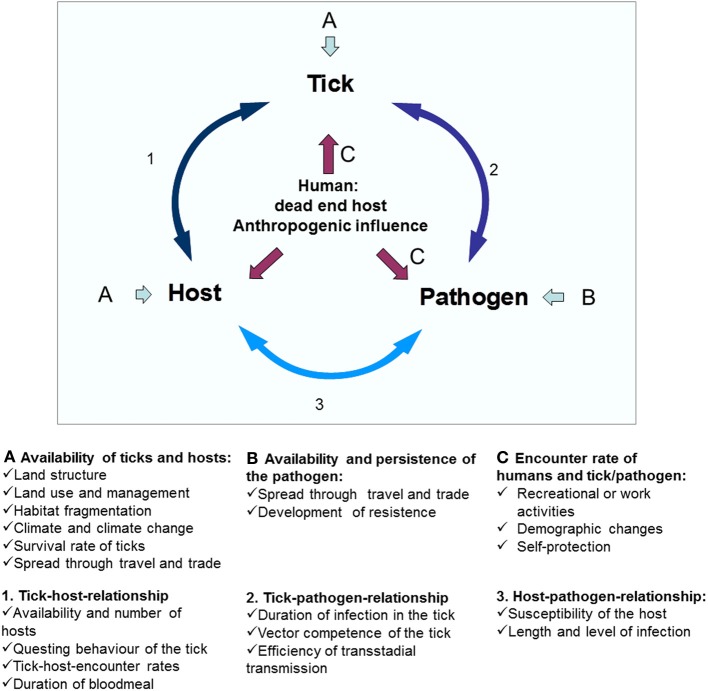

Variations in the prevalence of A. phagocytophilum in ticks may be attributed to several factors, such as the susceptibility of individual tick species, the susceptibility of certain tick populations, and the vector competence of tick species; the transmissibility of the A. phagocytophilum variant involved, the susceptibility of different host species, the susceptibility of individual hosts or host populations and the reservoir competence of the host. Especially the availability of different reservoir hosts and the adaptation strategy of A. phagocytophilum seem to be crucial factors in this variability. The availability of reservoir hosts depends on factors such as landscape structure and fragmentation (Medlock et al., 2013). In addition, effects exerted by changes in climate, demography, and agriculture may influence the tick distribution and density and their hosts.

Hosts and reservoirs

Viable A. phagocytophilum organisms have been isolated from several hosts, such as cattle, sheep, goat, dog, horse, human, red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Caperolus capreolus), and white-tailed deer (WTD) (Odocoileus virginianus) (Foggie, 1951; Goodman et al., 1996; Munderloh et al., 1996; Woldehiwet et al., 2002; Massung et al., 2007; Stuen et al., 2010; Silaghi et al., 2011c). However, several prerequisites have to be fulfilled for a reservoir to be competent for a transstadially transmitted pathogen. A reservoir host must be fed on by an infected vector tick; it must take up a critical number of the infectious agent; it must allow the pathogen to multiply and survive for a period and it must allow the pathogen to find its way into other feeding ticks (Kahl et al., 2002). Several mammals may serve as hosts and reservoirs.

Wild ruminants

In Europe, Asia, and America, A. phagocytophilum has been detected in local wild ruminant species (Tables 6–8). Wild ruminants such as WTD and roe deer are among the major feeding hosts for ticks in the Eastern US and Europe, respectively, and thus considered to contribute to a rapid increase in the population of ticks (Spielman et al., 1985; Vázquez et al., 2011; Medlock et al., 2013). WTD is considered one of the major reservoir hosts for an apathogenic variant (Ap-V1) of A. phagocytophilum in the Eastern US (Massung et al., 2005). Several genetic variants of A. phagocytophilum have been found in roe deer in Europe and there seem to be both potentially pathogenic and apathogenic variants occurring in roe deer (Silaghi et al., 2011b; Overzier et al., 2013a). A high roe deer density is associated with a high tick density (Jensen et al., 2000; Carpi et al., 2008; Rizzoli et al., 2009) and both presence and high density of roe deer seems to have a positive effect on the A. phagocytophilum prevalence (Rosef et al., 2009). Similarly, the density of WTD influences the density of I. scapularis ticks in the north-eastern US (Rand et al., 2003). For example, the elimination of WTD from certain areas lead to a drastic reduction of the occurrence of I. scapularis (Wilson et al., 1988). In a later study, however, there was no direct effect of a deer culling program on the occurrence of I. scapularis developmental stages (Jordan et al., 2007).

Table 6.

DNA-Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in blood/spleen in vertebrate hosts in the Americas*.

| Group of animals | Animal species | Country | No. of investigated | Prevalence in % | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild ruminants | White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) | USA | 458 | 16.0 | PCRa,b | Dugan et al., 2006 |

| USA (Wisconsin) | 181 | 15 | PCRa | Belongia et al., 1997 | ||

| USA (Minnesota) | 266 | 46.6 | PCRb | Johnson et al., 2011 | ||

| USA (Connecticut) | 63 | 37.0 | PCRb | Magnarelli et al., 1999 | ||

| USA (Pennsylvania) | 38 | 28.9 | nPCRa | Massung et al., 2005 | ||

| USA (Wisconsin) | 18 | 5.6 | PCRb | Michalski et al., 2006 | ||

| 40 | 22.5 | |||||

| USA (Mississippi) | 32 | 3.1 | PCRb | Castellaw et al., 2011 | ||

| Black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemonius columbianus) | USA (California) | 15 | 26.7d | nPCRa | Foley et al., 1998 | |

| Mule deer (O. h. hemonius) | USA (California) | 6 | 83.3d | nPCRa | Foley et al., 1998 | |

| Elk (Cervus elaphus nannodes) | USA (California) | 29 | 31.0 | nPCRa | Foley et al., 1998 | |

| Small mammals (rodents) | White-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) | USA (Minnesota) | 158 | 11.4 | nPCRa | Walls et al., 1997 |

| 98–150 | 20.0–46.8 | PCRb | Johnson et al., 2011 | |||

| USA (Connecticut) | 47 | 36.2 | nPCRa | Stafford et al., 1999 | ||

| 135 | 14.1 | PCRb | Levin et al., 2002 | |||

| Meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius) | USA (Minnesota) | 18 | 50.0 | PCRb | Johnson et al., 2011 | |

| Cotton mouse (P. gossypinus) | USA (Florida) | 41 | 4.9 | PCRb | Clark, 2012 | |

| Deer mouse (P. maniculatus) | USA (Colorado) | 63 | 20.6 | PCRa | Zeidner et al., 2000 | |

| 55d | 9.2d | PCRb | DeNatale et al., 2002 | |||

| Brush mouse (P. boylii) | USA (California) | n.s. | 4.0 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |

| Pinyon mouse (P. truei) | USA (California) | 5e | 20.0 | PCRc | Nicholson et al., 1999 | |

| Western harvest mouse (Rheithrodontomys megalotis) | USA (California) | n.s. | 6.3 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |

| Red-backed vole (Clethrionomys gapperi) | USA (Minnesota) | 6 | 17.0 | nPCRa | Walls et al., 1997 | |

| 73 | 15.1 | PCRb | Johnson et al., 2011 | |||

| Meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) | USA (Minnesota) | 14 | 14.3 | PCRb | Johnson et al., 2011 | |

| Prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) | USA (Colorado) | 15 | 6.6 | PCRa | Zeidner et al., 2000 | |

| Eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus) | USA (Minnesota) | 23 | 4.3 | nPCRa | Walls et al., 1997 | |

| USA (Rhode Island) | 19 | 57.9 | nPCRa | Massung et al., 2002 | ||

| Chipmunk | USA (Minnesota) | 43 | 88.4 | PCRb | Johnson et al., 2011 | |

| Least chipmunk (T. minimus) | USA (Colorado) | 5 | 40.0 | PCRb | DeNatale et al., 2002 | |

| Redwood chipmunk (T. ochrogenys) | USA (California) | 60 | 6.6 | qPCRb | Nieto and Foley, 2008 | |

| n.s. | 6.9 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |||

| 141 | 10.6 | qPCRb | Foley and Nieto, 2011 | |||

| Sonoma chipmunk (T. sonomae) | USA (California) | 5 | 40 | qPCRb | Nieto and Foley, 2008 | |

| n.s. | 50.0 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |||

| Chipmunk | USA (California) | 81 | 8.9 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2011 | |

| Tamias sp. | USA (California) | 50 | 16.7d | qPCRb | Rejmanek et al., 2011 | |

| Golden-mantled ground squirrel (Spermophilus lateralis) | USA (Colorado) | 8 | 13 | PCRb | DeNatale et al., 2002 | |

| Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) | USA (California) | 27 | 11.1 | qPCRb | Nieto and Foley, 2008 | |

| n.s. | 18.8 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |||

| 9 | 11.1d | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2010 | |||

| Western gray squirrel (S. griseus) | USA (California) | 41 | 12.1 | qPCRb | Nieto and Foley, 2008 | |

| n.s. | 15.8 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |||

| 37 | 10.8d | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2010 | |||

| 6e | n.a. | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008a | |||

| Douglas squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) | USA (California) | 2e | n.a. | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008a | |

| Northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) | USA (California) | 20 | 5 | qPCRb | Nieto and Foley, 2008 | |

| n.s. | 16.7 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |||

| 24 | 4.2d | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2007 | |||

| 4 | 25.0d | qPCRb | Rejmanek et al., 2011 | |||

| Cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) | USA (Florida) | 31 | 45.2 | PCRb | Clark, 2012 | |

| Mexican wood rat (Neatoma mexicana) | USA (Colorado) | 36 | 38.8 | PCRa | Zeidner et al., 2000 | |

| 30d | 15d | PCRb | DeNatale et al., 2002 | |||

| Dusky-footed woodrat (Neatoma fuscipes) | USA (California) | 25e | 68 | PCRc | Nicholson et al., 1999 | |

| 35e, f | 68.6 | PCRc | Castro et al., 2001 | |||

| 134 | 71 | qPCRb | Drazenovich et al., 2006 | |||

| n.s. | 4.3 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |||

| 42 | 11.8 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2011 | |||

| 53 | 9.4d | qPCRb | Rejmanek et al., 2011 | |||

| Big free-tailed bat (Nyctinomops macrotis) | USA (California) | n.s. | 1.8 | qPCRb | Foley et al., 2008b | |

| Small mammals (insectivores) | Short-tailed shrew (Blarina spp.) | USA (Minnesota) | 29 | 17.2 | PCR | Johnson et al., 2011 |

| Reptiles and Snakes | Northern alligator lizard (Elgaria coeruleus) | USA (California) | 3 | 33.3 | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2009 |

| Sage-brush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) | USA (California) | 4 | 25.0 | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2009 | |

| Western fence lizard (S. occidentalis) | USA (California) | 77 | 9.1 | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2009 | |

| Pacific gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer) | USA (California) | 5 | 20.0 | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2009 | |

| Common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) | USA (California) | 1 | 100 | qPCRb | Nieto et al., 2009 | |

| Other | Cottontail rabbit (S. floridanus) | USA (Massachusetts) | 203 | 27 | nPCRa | Goethert and Telford, 2003 |

| American black bear | USA (California) | 80 | 4 | qPCRb | Drazenovich et al., 2006 | |

| Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) | USA (California) | 70f | 9 | qPCRb | Gabriel et al., 2009 | |

| Raccoon (Procyon lotor) | USA (Connecticut) | 57 | 24.6 | PCRb | Levin et al., 2002 | |

| Domestic animals | Cat (stray) | USA (Connecticut) | 6 | 33.3 | PCRb | Levin et al., 2002 |

| Dog | USA (Minnesota) | 222 | 3 | PCRa | Beall et al., 2008 | |

| 51g | 37 | |||||

| USA (California) | 97 | 7 | qPCRb | Drazenovich et al., 2006 | ||

| 184 | 7.6 | qPCRb | Henn et al., 2007 | |||

| Brazil | 253 | 7.1 | qPCRb | Santos et al., 2011 | ||

| Horse | Guatemala | 74 | 13 | nPCRa | Teglas et al., 2005 | |

| Cattle | Guatemala | 48 | 51 | nPCRa | Teglas et al., 2005 |

This table does not claim completeness. It does not include studies with 0% prevalence and case reports.

nPCR, nested PCR; qPCR, real-time PCR; n.s., not specified.

16S rRNA as gene target.

Msp2 as gene target.

GroEL as gene target.

Total prevalence/number not specified in the paper, prevalence/number was calculated by the authors of the present manuscript.

Seropositive for Anaplasma phagocytophilum antibodies.

Includes recaptures.

Partially with symptoms.

Table 8.

Detection of DNA of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in spleen/blood of vertebrate hosts in Asia and Africa*.

| Group of animals | Animal species | Country | No. of investigated | Prevalence in % | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASIA | ||||||

| Wild ruminants | Sika deer (Cervus nippon) | Japan | 22 | 46.0 | nPCRa | Jilintai et al., 2009 |

| 126 | 19.0 | nPCRa | Kawahara et al., 2006 | |||

| 32 | 15.6 | nPCRa | Masuzawa et al., 2011 | |||

| Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) | Korea | 66 | 63.6 | nPCRa | Kang et al., 2011 | |

| Wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) | China | 20 | 10.0 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2008 | |

| 21 | 9.5 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| Black-striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) | China | 24 | 20.8 | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2006 | |

| 142 | 9.9 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| 78 | 12.8 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |||

| 12 | 16.7 | nPCRa | Yang et al., 2013 | |||

| Korea | 358 | 5.6 | nPCRa | Chae et al., 2008 | ||

| 373 | 23.6d | nPCRa | Kim et al., 2006 | |||

| Korean field mouse (Apodemus peninsulae) | Russia | 359 | 0.6d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| China | 43 | 7.0 | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2006 | ||

| 74 | 5.4 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| 4 | 25.0 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |||

| Bank vole (M. glareolus) | Russia | 61d | 6.6d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| Red-backed vole (Myodes rutilus) | Russia | 189d | 14.8d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| Red gray-backed vole (Myodes rufocanus) | Russia | 776d | 5.2d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| China | 65 | 4.6 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | ||

| East-European field vole (Microtus rossiaemeridionalis) | Russia | 38e | 2.6d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| Brown house rat (Rattus norvegicus) | China | 9 | 55.5 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |

| 9 | 33.3 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2008 | |||

| Chinese white bellied rat (Niviventer confucianus) | China | 48 | 12.5 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2008 | |

| 115 | 5.2 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| White-bellied giant rat (Niviventer coxingi) | China | 4 | 25.0 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2008 | |

| 4 | 25.0 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| Lesser rice field rat (Rattus losea) | China | 2 | 50.0 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2008 | |

| 32 | 3.1 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| Brown rat (R. norvegicus) | China | 47 | 8.5 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |

| Siberian chipmunk (Tamias sibiricus) | Russia | 24 | 25.0d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| China | 3 | 33.3 | nPCRa | Cao et al., 2006 | ||

| 18 | 5.6 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |||

| Great long-tailed hamster (Tscherskia triton) | China | 65 | 9.2 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |

| Cricetulus sp. | China | 39 | 5.1 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009a | |

| Gray hamster (Cricetulus migratorius) | China | 3 | 33.3 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |

| Small mammals (insectivores) | White-toothed shrew (Crocidura lasiura) | Korea | 33 | 63.6d | nPCRa | Kim et al., 2006 |

| Common shrew (Sorex araneus) | Russia | 137d | 4.4d | nPCRa | Rar et al., 2011 | |

| Other | Chinese hare (Lepus sinensis) | China | 54 | 1.9 | nPCRa | Zhan et al., 2009b |

| Wild boar (Sus scrofa) | Japan | 56 | 3.6 | nPCRa | Masuzawa et al., 2011 | |

| Domestic animals | Dog | China | 101 | 10.9 | nPCRa | Zhang et al., 2012a |

| Cattle | Japan | 15 | 80.0 | PCRa | Ooshiro et al., 2008 | |

| 78 | 1.0 | nPCRa | Jilintai et al., 2009 | |||

| 1251 | 3.4 | PCRb | Murase et al., 2011 | |||

| 50 | 2.0 | nPCRc | Ybañez et al., 2013 | |||

| China | 71 | 23.9 | nPCRa | Zhang et al., 2012a | ||

| 201 | 23.4 | nPCRa | Zhang et al., 2012a | |||

| Yaks | China | 158 | 32.3 | nPCRa | Yang et al., 2013 | |

| Cattle-yaks | China | 20 | 35.0 | nPCRa | Yang et al., 2013 | |

| Sheep | China | 70f | 7.1 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |

| 49 | 42.9 | nPCRa | Yang et al., 2013 | |||

| Goat | China | 35f | 5.7 | qPCRb | Zhan et al., 2010 | |

| 91 | 38.5 | nPCRa | Yang et al., 2013 | |||

| 90 | 48.9 | nPCRa | Zhang et al., 2012b | |||

| 472 | 26.7 | nPCRa | Zhang et al., 2012a | |||

| 262 | 6.1 | nPCRa | Liu et al., 2012 | |||

| AFRICA | ||||||

| Domestic animals | Dog | Tunisia | 228 | 0.9d | PCRa | M'Ghirbi et al., 2009 |

| Horse | Tunisia | 60 | 13 | nPCRa | M'Ghirbi et al., 2012 | |

This table does not claim completeness. It does not include studies with 0% prevalence.

nPCR, nested PCR; qPCR, real-time PCR.

16S rRNA gene as target.

Msp2 gene as target.

GroEL gene as target.

Total prevalence not specified in the paper, prevalence was calculated by the authors of the present manuscript

Microtus spp.

Partially with symptoms.

In the US, WTD has prevalence rates of A. phagocytophilum of up to 46.6% (Table 6), while detection of A. phagocytophilum in wild ruminants other than WTD are scarce so far. In Europe, roe deer show prevalence rates reaching up to 98.9% (Overzier et al., 2013a). Other deer species seem to contribute to the endemic cycles in Europe, and may also constitute efficient reservoir hosts, as the pathogen has been detected in red deer with up to 87% prevalence, in fallow deer (Dama dama) with up to 72%, and in sika deer (Cervus nippon) with up to 50% (Table 7). A. phagocytophilum has also been identified in deer species in Asia, namely sika deer and water deer (Hydropotes inermis) with prevalence rates of up to 46% and of 63.6%, respectively (Jilintai et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2011; Table 8). However, the studies that have been conducted in Asia on wild ruminants are too few as to draw any definite conclusion on the distribution of A. phagocytophilum.

Table 7.

Detection of DNA of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in blood or tissue (majority spleen) of vertebrate hosts in Europe*.

| Group of animals | Animal species | Country | No. of investigated | Prevalence in % | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild ruminants | Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) | Denmark | 237 | 42.6 | qPCRb | Skarphedinsson et al., 2005 |

| UK | 112 | 38.0 | PCRd, SB | Alberdi et al., 2000 | ||

| 279 | 47.3 | qPCRb | Bown et al., 2009 | |||

| 5 | 20.0 | qPCRb | Robinson et al., 2009 | |||

| Poland | 166 | 9.6 | PCRa,c | Michalik et al., 2009 | ||

| 31 | 38.7 | nPCRa | Hapunik et al., 2011 | |||

| Slovakia | 2 | 50.0 | PCRa | Smetanová et al., 2006 | ||

| 30 | 50.0 | PCRa | Stefanidesová et al., 2008 | |||

| Czech Republic | 40 | 12.5 | qPCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | ||

| 10 | 30.0 | nPCRa | Zeman and Pecha, 2008 | |||

| Germany | 31 | 94.0 | nPCRa | Scharf et al., 2011 | ||

| 95 | 98.9 | qPCRb | Overzier et al., 2013a | |||

| Austria | 121 | 43.0 | qPCRd | Polin et al., 2004 | ||

| 19 | 52.6 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2011b | |||

| Switzerland | 103 | 18.4 | nPCRa | Liz et al., 2002 | ||

| Italy | 96 | 19.8 | PCRa | Beninati et al., 2006 | ||

| 8 | 50.0 | PCRa,e | Torina et al., 2008b | |||

| Spain | 29 | 38.0 | nPCRa | Oporto et al., 2003 | ||

| 17 | 18.0 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2008 | |||

| Red deer (Cervus elaphus) | Norway | 8 | 87.5g | nPCRa | Stuen et al., 2013 | |

| UK | 5 | 80.0 | qPCRb | Robinson et al., 2009 | ||

| Poland | 88 | 10.2 | PCRa,c | Michalik et al., 2009 | ||

| 106 | 50.9 | nPCRa | Hapunik et al., 2011 | |||

| Czech Republic | 15 | 13.3 | qPCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | ||

| 21 | 86.0 | nPCRa | Zeman and Pecha, 2008 | |||

| Slovakia | 3 | 33.3g | PCRa | Smetanová et al., 2006 | ||

| 49 | 53.1 | PCRa | Stefanidesová et al., 2008 | |||

| Austria | 7 | 28.6 | qPCRd | Polin et al., 2004 | ||

| 12 | 66.7 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2011b | |||

| Spain | 21 | 23.8g | nPCRa | Portillo et al., 2011 | ||

| Iberian red deer (C. e. hispanicus) | Spain | 6 | 100 | PCRe | Naranjo et al., 2006 | |

| Fallow deer (Dama dama) | UK | 58 | 21.0 | qPCRb | Robinson et al., 2009 | |

| Poland | 44 | 20.5 | PCRa,c | Michalik et al., 2009 | ||

| 130 | 1.5 | nPCRa | Hapunik et al., 2011 | |||

| 50 | 14.0g | PCRa | Adaszek et al., 2012 | |||

| Czech Republic | 15 | 13.3 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | ||

| 2 | 50.0 | nPCRa | Zeman and Pecha, 2008 | |||

| Italy | 72 | 15.3 | PCRa | Veronesi et al., 2011 | ||

| 29 | 72.4 | nPCRa | Ebani et al., 2011 | |||

| Sika deer (Cervus nippon) | UK | 12 | 50.0 | qPCRb | Robinson et al., 2009 | |

| Poland | 32 | 34.4 | nPCRa | Hapunik et al., 2011 | ||

| Czech Republic | 5 | 40.0 | nPCRa | Zeman and Pecha, 2008 | ||

| Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) | Austria | 23 | 26.1 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2011b | |

| Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) | Austria | 18 | 16.7 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2011b | |

| Mouflon (Ovis musimon) | Czech Republic | 28 | 4.0 | nPCRa | Zeman and Pecha, 2008 | |

| 15 | 13.3 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | |||

| Slovakia | 2 | 50.0 | PCRa | Stefanidesová et al., 2008 | ||

| Austria | 6 | 50.0 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2011b | ||

| European bison (Bison bonasus) | Poland | 26 | 58.0 | nPCRa | Scharf et al., 2011 | |

| 5 | 57.7g | nPCRa | Matsumoto et al., 2009 | |||

| Small mammals (rodents) | Yellow necked-mouse (Apodemus flavicollis) | Czech Republic | 40 | 15.0 | qPCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 |

| Slovakia | 38 | 5.3g | PCRa | Smetanová et al., 2006 | ||

| Germany | 218 | 0.5 | nPCRa | Hartelt et al., 2008 | ||

| Switzerland | 69 | 2.9 | nPCRa | Liz et al., 2000 | ||

| Wood mouse (A. sylvaticus) | UK | 902j | 0.8 | nPCRa | Bown et al., 2003 | |

| Switzerland | 48 | 4.2 | nPCRa | Liz et al., 2000 | ||

| France | 18 | 11.1g | PCRa | Matsumoto et al., 2007 | ||

| Spain | 162 | 0.6 | PCRb, RLB | Barandika et al., 2007 | ||

| Black-striped field mouse (A. agrarius) | Bulgaria | 9 | 33.3 | PCRc | Christová and Gladnishka, 2005 | |

| Bank vole (Myodes glareolus) | UK | 527 | 5.0 | nPCRa | Bown et al., 2003 | |

| Czech Republic | 15 | 13.3 | qPCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | ||

| Switzerland | 78 | 19.2 | nPCRa | Liz et al., 2000 | ||

| Germany | 149 | 13.4 | nPCRa | Hartelt et al., 2008 | ||

| 36 | 5.5 | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2012b | |||

| Common vole (Microtus arvalis) | Germany | 97 | 6.2 | nPCRa | Hartelt et al., 2008 | |

| Field vole (Mi. agrestis) | UK | 163 | 6.7 | nPCRa | Bown et al., 2006 | |

| 2402j | 6.7 | qPCRb | Bown et al., 2008 | |||

| 1503j | 6.3 | qPCRb | Bown et al., 2009 | |||

| Root vole (Mi. oeconomus) | Poland | 30 | 6.7g | nPCRa | Grzeszczuk et al., 2006 | |

| Black rat (Rattus rattus) | Bulgaria | 136 | 4.4 | PCRc | Christová and Gladnishka, 2005 | |

| Porcupine (Hystricidae) | Italy | 1 | 100 | PCRa | Torina et al., 2008a | |

| Small mammals (insectivores) | Common shrew (Sorex araneus) | UK | 76 | 1.3 | PCRa | Bray et al., 2007 |

| 647j | 18.7 | qPCRb | Bown et al., 2011 | |||

| Switzerland | 5 | 20.0g | nPCRa | Liz et al., 2000 | ||

| European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) | Germany | 31 | 25.8 | nPCRa | Skuballa et al., 2010 | |

| 48 | 85.4g | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2012a | |||

| Greater white-toothed shrew (Crocidura russula) | Spain | 6 | 16.7 | PCRb, RLB | Barandika et al., 2007 | |

| Birds | Blackbird (Turdus merula) | Spain | 3 | 100 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b |

| Chaffinch (Fringilla coelobs) | Spain | 1 | 100 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| House sparrow (Passer domesticus) | Spain | 18 | 6.0 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| Spanish Sparrow (Passer hispaniolensis) | Spain | 3 | 33.0 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| Rock bunting (Emberiza cia) | Spain | 1 | 100 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| Woodchat shrike (Lanius senator) | Spain | 1 | 100 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| Magpie (Pica pica) | Spain | 1 | 100 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| Long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus) | Spain | 1 | 100 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | |

| Other | European Brown bear (Ursus arctos) | Slovakia | 74 | 24.3 | PCRa | Vichová et al., 2010 |

| Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) | Poland | 111 | 2.7 | nPCRa | Karbowiak et al., 2009 | |

| Czech Republic | 25 | 4.0 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | ||

| Italy | 150 | 16.6 | nPCRa | Ebani et al., 2011 | ||

| Wild boar (Sus scrofa) | Poland | 325 | 12 | nPCRa | Michalik et al., 2012 | |

| Slovakia | 18 | 5.5g | PCRa | Smetanová et al., 2006 | ||

| Czech Republic | 69 | 4.4 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | ||

| Slovenia | 113 | 2.7g | PCRa | Galindo et al., 2012 | ||

| 160 | 6.3 | qPCRf | Zele et al., 2012 | |||

| Hare (Leparus europaeus) | Czech Republic | 8 | 12.5 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | |

| Domestic animals | Cat | Germany | 306 | 0.3g | qPCRb | Hamel et al., 2012a |

| Germany | 265 | 0.4 | qPCRb | Morgenthal et al., 2012 | ||

| Dog | UK | 120k | 0.8g | PCRa | Shaw et al., 2005 | |

| Poland | 408 | 0.5 | PCRc | Zygner et al., 2009 | ||

| 242k | 5.4 | PCRb | Rymaszewska and Adamska, 2011 | |||

| Czech Republic | 296k | 3.4 | nPCRa | Kybicová et al., 2009 | ||

| Germany | 111 | 6.3 | nPCRa | Jensen et al., 2007 | ||

| 522k | 5.7 | qPCRb | Kohn et al., 2011 | |||

| Italy | 46 | 2.8–21.7i | PCRa,e | Torina et al., 2008a | ||

| Italy (Sardinia) | 50k | 7.5g | nPCRd | Alberti et al., 2005a | ||

| Hungary/Romania | 216 | 1.9 | qPCRb | Hamel et al., 2012b | ||

| Horse | Czech Republic | 40 | 5 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | |

| Netherlands | 61k | 9.8g | PCRa, RLB | Butler et al., 2008) | ||

| Italy | 135k | 8.1g | nPCRa | Passamonti et al., 2010 | ||

| 5k | 80.0g | PCR | Lillini et al., 2006 | |||

| 134 | 0–4.7i | PCRa,e | Torina et al., 2008a | |||

| 300 | 6.7g | PCRa | Laus et al., 2013 | |||

| 42 | 4.7 | PCRa, e | Giudice et al., 2012 | |||

| Italy (Sardinia) | 20k | 15.0g | nPCRd | Alberti et al., 2005a | ||

| Donkey | Italy | 76 | 4 | PCRa, e | Torina et al., 2008b | |

| Spain | 3 | 100 | PCRe | Naranjo et al., 2006 | ||

| Cattle | Czech Republic | 55 | 5.5 | PCRa | Hulínská et al., 2004 | |

| France | 20j | 20.0g | PCRa, d, e | Laloy et al., 2009 | ||

| Switzerland | 27k 16k | 4.0 13.0 | qPCRa | Hofmann-Lehmann et al., 2004 | ||

| Italy | 78 | 17 | PCRa, e | Torina et al., 2008b | ||

| 374 | 0–2.9i | PCRa, e | Torina et al., 2008a | |||

| Spain | 107 | 19 | PCRe | de la Fuente et al., 2005b | ||

| 157 | 13 | PCRe | Naranjo et al., 2006 | |||

| Sheep | Norway | 32 | 37.5g | nPCRa, e | Stuen et al., 2013 | |

| Denmark | 43 | 11.6g | PCRa | Kiilerich et al., 2009 | ||

| Germany | 255 | 4 | nPCRa | Scharf et al., 2011 | ||

| Italy | 200 | 11.5 | PCRa | Torina et al., 2010 | ||

| 286 | 0–3.8i | PCRa, e | Torina et al., 2008a | |||

| 90 | 3 | PCRa | Torina et al., 2008b | |||

| Sheep, goats | Slovakia, Czech Republic | 323 | 2.8h | PCRe | Derdáková et al., 2011 | |

| Goats | Switzerland | 72 | 5.6g | qPCRb | Silaghi et al., 2011e | |

| Italy | 134 | 0–3.5i | PCRa, e | Torina et al., 2008a |

This table does not claim completeness. It does not include studies with 0% prevalence and case reports.

nPCR, nested PCR; qPCR, real-time PCR; RLB, reverse line blot, SB, Southern Blot.

16S rRNA as gene target.

Msp2 as gene target.

AnkA as gene target.

GroEL as gene target.

Msp4 as gene target.

Commercial kit.

Total prevalence not specified in the paper, prevalence was calculated by the authors of the present manuscript.

Sheep only.

Range represents confidence interval.

Individuals sampled several times.

Partially with symptoms.

Small mammals

The second large group of animals that A. phagocytophilum is found in endemic countries are in small mammals such as rodents and insectivores. These animals also are major feeding hosts for ticks, especially for the developmental stages (Kiffner et al., 2011). DNA of A. phagocytophilum was found in different mouse, vole, other rodent and insectivore species in the US, Europe, and Asia (Tables 6–8).

Rodents

In Europe, yellow-necked mice (Apodemus flavicollis) were infected with ranges from <1 to 15%, wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) from <1 to 11% and bank voles (Myodes glareolus) from 5 to 19.2%. In mouse species, detection with higher prevalence rates represents only single studies, whereas detection in bank voles seemed higher and more consistent. This was also the case for other vole species in Europe (Table 6). In the UK, the field vole has been discussed as a potential small mammal reservoir (Bown et al., 2003). However, in several studies on rodents in Europe, no DNA of A. phagocytophilum has been detected or at such low prevalence rates, that a reservoir role of this group of animals in Europe remains unclear (Barandika et al., 2007; Silaghi et al., 2012b; Table 6).

On the contrary, in the Eastern US, the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) is considered one of the major reservoir hosts for the human pathogenic variant (Ap-ha) (Massung et al., 2003). P. leucopus is found as the predominant small mammal in forested habitats throughout the Eastern and Central US and it is one of the major hosts for the larval stages of I. scapularis (Sonenshine, 1993). The white-footed mouse has reservoir competence for the AP-ha variant, but reservoir competence could not be shown for the apathogenic Ap-V1 variant (Massung et al., 2003), as opposed to the aforementioned WTD as a major reservoir hosts for Ap-V1 (Massung et al., 2005). Different lengths of infections with the two strains have also been shown in an experimental WTD study: Ap-V1 from tick cells resulted in lasting parasitemia, whereas infection with Ap-ha was short-lived (Reichard et al., 2009). By contrast, both Ap-V1 and Ap-ha were infectious for goats and goats are reservoir competent to Ap-V1 (Massung et al., 2006).

Ap-V1 was isolated from goats and I. scapularis and propagated in the ISE6 tick cell line, but it could not be cultivated in the human HL-60 cell line. This stands in contrast to A. phagocytophilum strains which have been isolated from human cases in the US, which readily grow in HL-60 cell lines (Horowitz et al., 1998; Massung et al., 2007), suggesting differing host specificity for these two strain types.

Apart from the white-footed mouse, A. phagocytophilum DNA has been detected in several rodent species such as voles and chipmunks in the Eastern US, cotton mice and cotton rats in Florida and several mouse-, chipmunk-, and squirrel-species as well as the dusky-footed woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes) in the Western US (Table 7). Prevalence ranges from 1.8 to 88.4%. The gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) has also been found to be reservoir competent (Levin et al., 2002) and the redwood chipmunk (Tamias ochrogenys) and sciurid rodents are discussed as important reservoir hosts for A. phagocytophilum in the Western US (Nieto et al., 2010; Foley and Nieto, 2011). Similarly to other small mammals that have been suggested to maintain niche cycles, the redwood chipmunk hosts both antropophilic (I. pacificus) and nidicolous (I. angustus) ticks (Foley and Nieto, 2011).

In Asia, comparatively high prevalence rates in small mammals also seem to indicate a reservoir function of this group of mammals (Table 8). For example, in China, wood mice showed prevalence rates up to 10.0% (Zhan et al., 2008), Korean field mice (A. peninsulae) up to 25% (Zhan et al., 2010) and black-striped field mice (A. agrarius) up to 20.8% (Cao et al., 2006). In Korea, prevalence rates in the black-striped field mouse was also up to 23.6% (Kim et al., 2006) and therefore, A. agrarius has been discussed as one of the major reservoir host in Asian countries. In the Asian part of Turkey, however, all captured rodents were serologically negative for A. phagocytophilum (Güner et al., 2005).

Additionally to mice, voles, chipmunks, and squirrels, DNA of A. phagocytophilum has also been detected in rats on all three continents, in hamsters (China) and in a porcupine (Italy) (Tables 6–8).

Insectivores

There are very few published studies on the role of insectivores in the life cycle of A. phagocytophilum. The common shrew (Sorex araneus) has been discussed as a reservoir host for A. phagocytophilum in the UK (Bown et al., 2011). In that study, prevalence reached 18.7%. Other insectivores which have been investigated in Europe were the greater white-toothed shrew (Crocidura russula) and the European hedgehog (Table 6). DNA of A. phagocytophilum has also been detected in short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda) with 17.2% prevalence in the US and in Asia in white-toothed shrews with 63.6% prevalence (Tables 6, 8). Detection rates of A. phagocytophilum in insectivores were generally high, with average prevalence rates around 20%, reaching over 80%. However, the role of insectivores in the life cycle of A. phagocytophilum needs further investigation.

Other animal species

Apart from wild ruminants, rodents and insectivores, there are several other vertebrate species in which DNA from A. phagocytophilum has been isolated. Whether these contribute to the endemic cycle of A. phagocytophilum is currently not clear. Amongst these animals are mammals such as wild boars, foxes, and bears, but also birds and reptiles (Tables 6–8). The prevalence rates in these animal species seem similar to the potential reservoir hosts discussed above, but studies have been very few so a final conclusion is not yet possible. In the US, raccoons (Procyon lotor) have been found to be reservoir competent for A. phagocytophilum (Levin et al., 2002; Yabsley et al., 2008), while wild boar (Sus scrofa) has recently been discussed as a host for human pathogenic variants of A. phagocytophilum in Europe (Michalik et al., 2012).

The questions which remain open are whether many different animal species get infected only temporarily with potentially non-species specific strains of A. phaogcytophilum and constitute dead-end hosts such as human beings, whether they develop clinical signs of disease or if they contribute in any way to the endemic cycle.

Domestic animals

Dogs in Europe were positive for DNA of A. phagocytophilum at about 1–6% prevalence, regardless whether they show symptoms of canine granulocytic anaplasmosis or not. By comparison, the prevalence rates in cats were much lower, with <0.5%. In horses, prevalence was higher ranging up to 80%, however, several of the studies investigated horses with symptoms of equine granulocytic anaplasmosis. Without any clinical signs, the prevalence in horses was less than 6.7% (Tables 6–8). Furthermore, several case reports and case series have been published on domestic animals in North America (e.g., Cockwill et al., 2009; Granick et al., 2009; Uehlinger et al., 2011), and serological studies have shown a wide evidence of dogs, cats, and horses being in contact with A. phagocytophilum in USA, Canada, and Asia (e.g., Magnarelli et al., 2001; Billeter et al., 2007; Bowman et al., 2009; Villeneuve et al., 2011; Bell et al., 2012; Ybañez et al., 2012). Additionally, serological and molecular evidence have been provided from North Africa (which also is an endemic area for I. ricinus) that horses and dogs become infected with A. phagocytophilum (M'Ghirbi et al., 2009, 2012). This important finding broadens the known geographic range of A. phagocytophilum to Africa as another continent.

The role of dogs as reservoir hosts has been discussed (Schorn et al., 2011). Furthermore, a report of granulocytic anaplasmosis has been described in another member of the canine family, a captive timber wolf (Canis lupus) (Leschnik et al., 2012). The question remains open whether dogs can contribute to the natural cycle of A. phagocytophilum: Is the infection persistent enough for subsequent ticks to become infected, and do dogs host enough nymphal stages of ticks to contribute to the spread? Animals which host mainly adult ticks cannot effectively contribute to the life cycle of A. phagocytophilum, as transovarial infection does not seem to occur.

Domestic ruminants

Infection with A. phagocytophilum has also been detected in several domestic ruminant species such as sheep, goats, cattle, and yaks (Tables 6–8). In Europe, domestic ruminants have been found infected with DNA with rates of up to 20% (cattle), 37% (sheep), and 5.6% (goats) (Table 6). However, larger scale molecular studies on domestic ruminants in Northern America are lacking, but cases of granulocytic anaplasmosis have been described in llama (Lama glama) and alpaca (Vicugna pacos) in California and Massachusetts, respectively (Barlough et al., 1997a,b; Lascola et al., 2009). Furthermore, serological evidence has been provided for A. phagocytophilum antibodies in cattle in Connecticut (Magnarelli et al., 2002).

Spread of infection

A. phagocytophilum may be spread between different geographic regions by both infected ticks and infected hosts. Expansion of existing endemic areas or to new geographic regions occurs when populations of competent vectors and reservoirs or the abundance of susceptible hosts increase both in total number and in geographic range.

Roe deer carry large number of ticks and moves over long distances (Vor et al., 2010) and may therefore add to the spread of the pathogen itself as well as by moving infected ticks to other areas (Overzier et al., 2013a). Factors contributing to a wider occurrence of suitable hosts such as WTD, white-footed mice, roe deer, field mice etc. may be landscape changes leading to an expansion in the distribution range as well as in the density of those hosts.

Landscape changes such as reforestation may also lead to an expansion of the anthropophilic ticks which are spread also when their primary feeding hosts expand (Sonenshine, 1993).

The increase and spread of I. scapularis in the Eastern US has lead to an increase in Lyme Borreliosis cases (Sonenshine, 1993) and may similarly contribute to the expansion of A. phagocytophilum. In Europe, the increasing geographic range of I. ricinus as well as the expansion to higher altitudes has recently been discussed by several authors (Materna et al., 2005; Jore et al., 2011; Jaenson et al., 2012; Medlock et al., 2013).