Abstract

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, costly, and difficult to treat disorder that impairs health‐related quality of life and work productivity. Evidence‐based treatment guidelines have been unable to provide guidance on the effects of acupuncture for IBS because the only previous systematic review included only small, heterogeneous and methodologically unsound trials.

Objectives

The primary objectives were to assess the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for treating IBS.

Search methods

MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, and the Chinese databases Sino‐Med, CNKI, and VIP were searched through November 2011.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture, other active treatments, or no (specific) treatment, and RCTs that evaluated acupuncture as an adjuvant to another treatment, in adults with IBS were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias and extracted data. We extracted data for the outcomes overall IBS symptom severity and health‐related quality of life. For dichotomous data (e.g. the IBS Adequate Relief Question), we calculated a pooled relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for substantial improvement in symptom severity after treatment. For continuous data (e.g. the IBS Severity Scoring System), we calculated the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI in post‐treatment scores between groups.

Main results

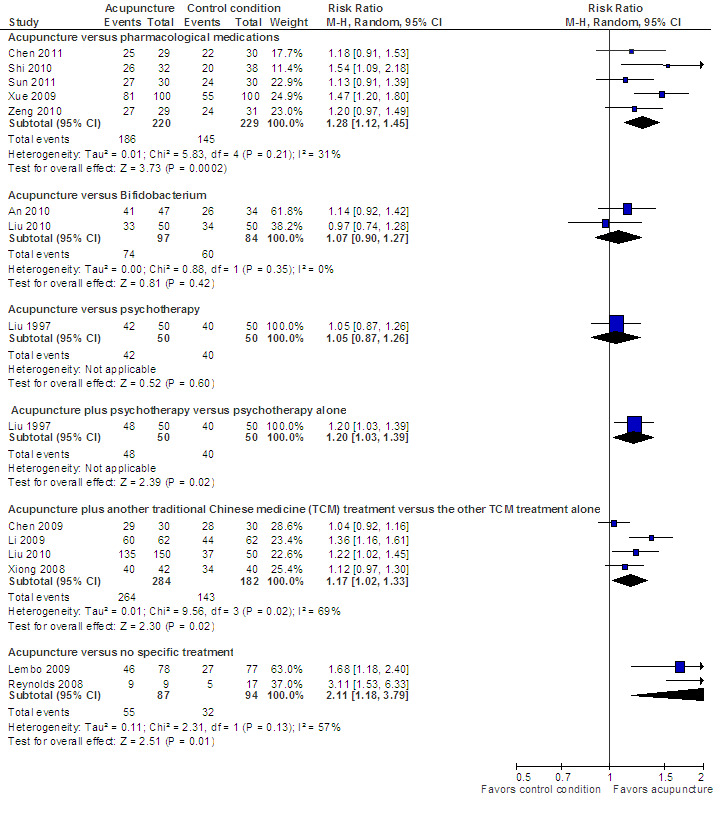

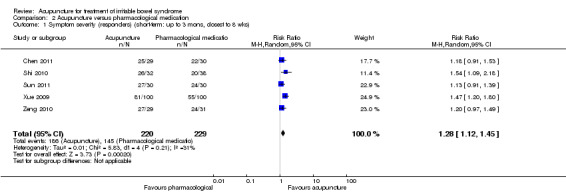

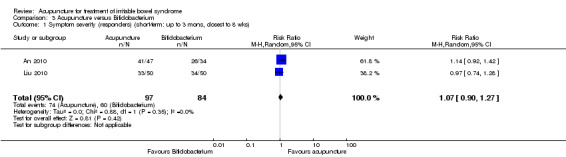

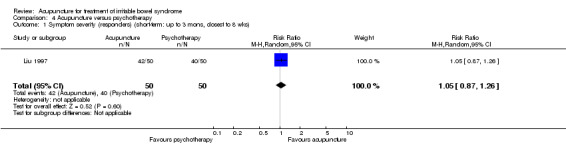

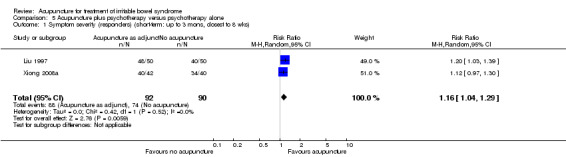

Seventeen RCTs (1806 participants) were included. Five RCTs compared acupuncture versus sham acupuncture. The risk of bias in these studies was low. We found no evidence of an improvement with acupuncture relative to sham (placebo) acupuncture for symptom severity (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.13; 4 RCTs; 281 patients) or quality of life (SMD = ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.22; 3 RCTs; 253 patients). Sensitivity analyses based on study quality did not change the results. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcomes in the sham controlled trials was moderate due to sparse data. The risk of bias in the four Chinese language comparative effectiveness trials that compared acupuncture with drug treatment was high due to lack of blinding. The risk of bias in the other studies that did not use a sham control was high due to lack of blinding or inadequate methods used for randomization and allocation concealment or both. Acupuncture was significantly more effective than pharmacological therapy and no specific treatment. Eighty‐four per cent of patients in the acupuncture group had improvement in symptom severity compared to 63% of patients in the pharmacological treatment group (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.45; 5 studies, 449 patients). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome was low due to a high risk of bias (no blinding) and sparse data. Sixty‐three per cent of patients in the acupuncture group had improvement in symptom severity compared to 34% of patients in the no specific therapy group (RR 2.11, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.79; 2 studies, 181 patients). There was no statistically significant difference between acupuncture and Bifidobacterium (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.27; 2 studies; 181 patients) or between acupuncture and psychotherapy (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.26; 1 study; 100 patients). Acupuncture as an adjuvant to another Chinese medicine treatment was significantly better than the other treatment alone. Ninety‐three per cent of patients in the adjuvant acupuncture group improved compared to 79% of patients who received Chinese medicine alone (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.33; 4 studies; 466 patients). There was one adverse event (i.e. acupuncture syncope) associated with acupuncture in the 9 trials that reported this outcome, although relatively small sample sizes limit the usefulness of these safety data.

Authors' conclusions

Sham‐controlled RCTs have found no benefits of acupuncture relative to a credible sham acupuncture control for IBS symptom severity or IBS‐related quality of life. In comparative effectiveness Chinese trials, patients reported greater benefits from acupuncture than from two antispasmodic drugs (pinaverium bromide and trimebutine maleate), both of which have been shown to provide a modest benefit for IBS. Future trials may help clarify whether or not these reportedly greater benefits of acupuncture relative to pharmacological therapies are due entirely to patients’ preferences for acupuncture or greater expectations of improvement on acupuncture relative to drug therapy.

Keywords: Humans, Acupuncture Therapy, Acupuncture Therapy/methods, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Irritable Bowel Syndrome/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal condition characterized by altered bowel habits and abdominal pain and discomfort. It is a common, costly, and difficult to treat disorder that also impairs health‐related quality of life and work productivity. Some pharmacological (i.e. drug) therapies for treating IBS have modest benefits and a risk for side effects, and therefore, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of non‐drug therapies, including acupuncture. One problem with trials in IBS is that placebo effects are often seen in IBS treatment. Placebo effects are improvements in symptoms that are due to patient beliefs in a particular treatment rather than the specific biological effects of the treatment.

This review included 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including a total of 1806 participants. Five RCTs (411 participants) compared acupuncture to sham acupuncture for the treatment of IBS. Sham acupuncture is a procedure in which the patient believes he or she is receiving true acupuncture. However, in sham acupuncture the needles either do not penetrate the skin or are not placed at the correct places on the body, or both. Sham acupuncture is intended to be a placebo for true acupuncture. The sham‐controlled studies were well designed and of high methodological quality. These studies tested the effects of acupuncture on IBS symptom severity or health‐related quality of life. None of these RCTs found acupuncture to be better than sham acupuncture for either of these two outcomes, and pooling the results of these RCTs also did not show acupuncture to be better than sham acupuncture. Evidence from four Chinese language comparative effectiveness trials showed acupuncture to be superior to two antispasmodic drugs (pinaverium bromide and trimebutine maleate), both of which provide a modest benefit for the treatment of IBS, although neither is approved for treatment of IBS in the United States. It is unclear whether or not the greater benefits of acupuncture reported by patients in these unblinded studies are due entirely to patients’ greater expectations of improvement from acupuncture than drugs or preference for acupuncture over drug therapy. There was one side effect (i.e. fainting in one patient) associated with acupuncture in the nine trials that reported side effects, although relatively small sample sizes limit the usefulness of this safety data.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome.

| Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with irritable bowel syndrome Settings: Canada (1), Germany (1), UK (1), US (2) Intervention: True acupuncture Comparison: Sham acupuncture | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Sham acupuncture | True acupuncture | |||||

| symptom severity (continuous outcome) IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS‐SSS)1. Scale from: 0 to 500. Follow‐up: 3‐13 weeks2 | The mean symptom severity (continuous outcome) in the control groups was 193 points3 | The mean symptom severity (continuous outcome) in the intervention groups was 9.2 lower (29.2 lower to 10.8 higher)4(Better values are indicated by lower scores.) | 281 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | SMD ‐0.11 (‐0.35 to 0.13) | |

| quality of life (continuous outcome) IBS Quality of Life (IBS‐QOL) Scale6. Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 3‐5 weeks2 | The mean quality of life (continuous outcome) in the control groups was 73.8 points3 | The mean quality of life (continuous outcome) in the intervention groups was .53 lower (4.8 lower to 3.9 higher)7(Better values are indicated by higher scores.) | 253 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | SMD ‐0.03 (‐0.27 to 0.22) | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS‐SSS) possesses responsiveness, face and construct validity (Francis 1997), and is one of the most widely used IBS symptom severity outcome measures. Better values are indicated by lower scores. 2 This outcome is for the short‐term follow‐up time point, defined as the time point closest to 8 weeks and less than or equal to 3 months after randomization. Outcomes were measured at the end of the treatment period in all studies, and because in all studies the end of treatment time point coincided with the time point closest to 8 weeks and less than or equal to 3 months, our short term outcome time points were the end of treatment for all trials. 3 We used the Lembo 2009 trial as the representative trial for the final value scores of symptom severity and quality of life in the control group because this trial was sufficiently large; the patient characteristics and the baseline means and SDs of symptom severity and quality of life in the control group of this trial were similar to and representative of the other trials; and this trial used the familiar IBS‐SSS scale for symptom severity and the well‐validated IBS‐QoL for quality of life. 4 The standardized mean difference (SMD) was re‐expressed into a mean difference by applying the calculated SMD back into the Lembo 2009 study and depicted on the IBS‐SSS scale used in that study. This calculation was made by multiplying the post‐treatment standard deviation of the IBS‐SSS score of the sham group in the Lembo trial by the pooled SMD. 5 Imprecision due to sparse data (less than 400 events ) and confidence intervals include possibility of benefit. 6 The IBS Quality of Life measure (IBS‐QoL) (Patrick 1998) is an extensively validated IBS quality of life scale (Bijkerk 2003; Irvine 2006). Better values are indicated by higher scores. 7 The standardized mean difference (SMD) was re‐expressed into a mean difference by applying the calculated SMD back into the Lembo 2009 study and depicted on the IBS‐QoL scale used in that study. This calculation was made by multiplying the post‐treatment standard deviation of the IBS‐QoL score of the sham group in the Lembo trial by the pooled SMD.

Summary of findings 2. Acupuncture versus pharmaceutical medications for irritable bowel syndrome.

| Acupuncture versus pharmaceutical medications for irritable bowel syndrome | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with irritable bowel syndrome Settings: China (5) Intervention: Acupuncture Comparison: Pharmaceutical medications | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Pharmaceutical medications | Acupuncture | |||||

| symptom severity (dichotomous outcome) Dichotomous measure of overall symptom severity1 Follow‐up: 3‐7 weeks2 | 633 per 10003had improved overall symptom severity in the pharmaceutical medication group | 810 per 1000 (709 to 918) had improved overall symptom severity in the acupuncture group | RR 1.28 (1.12 to 1.45) | 449 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 In cases where dichotomous outcomes such as improvement in IBS symptoms were presented in the form of multiple strata, such that we had the option of choosing cutpoints for the dichotomous outcome, we created a dichotomous measure in which all positive outcomes were combined into a single positive category (i.e., improvement) and the remaining strata constituted the negative category (i.e., no improvement). When investigators selected a cutpoint on a continuous scale to dichotomize between improvement and no improvement, we used the same cutpoint to define the dichotomous outcome. 2 This outcome is for the short‐term follow‐up time point, defined as the time point closest to 8 weeks and less than or equal to 3 months after randomization. 3 The assumed risk in the control group is based on the percentage of all participants in the control group who experienced improvement in symptom severity. There were a total of 229 control group participants, and 145 of these participants experienced improvement in symptom severity. 4 The primary limitation is that treatment in these studies was unblinded, and it is unclear whether or not the greater benefits of acupuncture reported by patients in these unblinded trials are due entirely to patients' greater expectations of improvement from acupuncture than drugs. Additionally, one study author (Xue Y 2009) explained that allocation to treatment was by means of a random number table and did not give further details.

5 Imprecision due to sparse data (less than 400 events).

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, relapsing gastrointestinal disorder characterized by altered bowel habits and abdominal pain and discomfort (Brandt 2009). A systematic review (Saito 2002) has estimated that 10 to 15% of adults in North America have IBS, as diagnosed by either the Rome (Vanner 1999) or Manning (Saito 2000) objective diagnostic criteria. IBS is associated with significant reductions in both health‐related quality of life (El‐Serag 2002) and work productivity (Maxion‐Bergemann 2006; Brandt 2009) and increased consumption of medical resources. Indeed, people with IBS consume over 50% more health care resources than age‐matched controls without IBS (Longstreth 2003; Talley 1995). The combined direct and indirect costs associated with IBS patients in the United States in 2004 were estimated at over $1 billion (Everhart 2008).

Effective treatments for IBS are needed to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and to reduce healthcare utilization. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology Task Force conducted a series of systematic reviews to evaluate the efficacy of both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological therapies for treating IBS (Brandt 2009). In terms of pharmacological treatments, the Task Force found “poor quality of evidence” for certain antispasmodics and “moderate quality of evidence” for tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, non‐absorbable antibiotics (for diarrhea‐predominant IBS), and C‐2 chloride channel activators (for constipation‐predominant IBS). The Task Force found "good quality of evidence" for 5HT3 antagonists and 5HT4 agonists, but noted that these agents carry a possible risk of ischemic colitis and cardiovascular events, respectively, which may limit their utility. A subsequent systematic review showed that the benefits of these 5HT3 antagonists and 5HT4 agonists relative to placebo are "modest" (Ford 2009a). In terms of non‐pharmacological therapies, the Task Force found “poor quality of evidence” for psyllium fiber and peppermint oil. The Task Force also noted that preliminary evidence suggested that some probiotics may be effective in reducing IBS symptoms (Brandt 2009). A subsequent systematic review (Brenner 2009) concluded that the specific probiotic B. infantis 35624 has shown repeated efficacy in well‐designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and can be considered an effective treatment for IBS.

The Task Force was unable to make any recommendations either for or against acupuncture for treating IBS because the only systematic review available at the time was a Cochrane review (Lim 2006) which was inconclusive because it included only small, heterogeneous, and methodologically unsound trials. Given the safety of acupuncture (MacPherson 2001; White 2001; Melchart 2004) and the limited availability of other safe and effective treatments for IBS, the question of whether acupuncture is effective for treating IBS is highly relevant. Recently, RCTs have been published which provide greater evidence to estimate the effects of acupuncture for treating IBS. We have therefore updated our previous Cochrane systematic review and meta‐analysis of acupuncture for IBS (Lim 2006) to assess whether the pooled effects of currently available trials show any benefit of acupuncture for improving symptoms or health‐related quality of life in patients with IBS.

Objectives

The primary objectives were to assess the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for treating IBS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in any language, published as either full articles or abstracts. Recent research indicates that a large proportion of Chinese‐language RCT reports are of studies that are not truly randomized (Wu 2009). An author (KC) therefore contacted the investigators of Chinese‐language RCTs by telephone to determine whether they had used randomization. The interviews were conducted using questions adapted from the survey developed by Wu et al to verify the authenticity of “claimed” randomized trials (Wu 2009). Responses were recorded and forwarded to a second review author (EM) for confirmation of RCT authenticity. The same questions were asked of authors of English‐language RCTs that did not include details about randomization methods in their published reports. Trials that were found to assign patients by alternation, rotation, or hospital record number were excluded. Trials that used a random method of assignment, but with flaws or suspected flaws in the random assignment process were included, but with their limitations described.

Types of participants

We included trials involving adult participants diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Examples of diagnostic criteria included but were not limited to the Manning criteria (Manning 1978), and Rome I (Drossman 1994), Rome II (Thompson 2000), or Rome III criteria (Longstreth 2006). We did not exclude trials in which patients were stated to be diagnosed with IBS but no diagnostic criteria were described.

Types of interventions

We included trials evaluating Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) acupuncture. TCM acupuncture involves inserting needles into traditional meridian points, usually with the intention of influencing energy flow in the meridian. Needles may also be inserted at additional tender points and electrical stimulation of the needles may be used. Since TCM acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion, we included trials using moxibustion as a co‐intervention with acupuncture. We excluded trials of dry needling or trigger point therapy, a therapy which is based on principles of Western anatomy and physiology and rejects TCM concepts of energy and meridians. We also excluded RCTs of laser acupuncture, non‐invasive electrostimulation (i.e. using electrodes on the skin rather than needles to stimulate acupuncture points (Ezzo 2005)), and acupressure, to restrict our focus to the effects of traditional needle acupuncture. Finally, we excluded trials of micropuncture, a non‐traditional acupuncture practice which is based on the principle that the ear (or nose, eye, etc.) is a microsystem of the entire body, and in which needles are only inserted on that microsystem. Identified trials using types of interventions that are not eligible are described in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table.

We included trials comparing acupuncture to any of the following control interventions: sham (placebo) acupuncture, no (specific) treatment, an active non‐TCM treatment, or evaluated acupuncture as an adjuvant to another treatment. Because our objective was to evaluate the effects of TCM acupuncture compared to a sham treatment, no treatment or a Western medicine control, we excluded RCTs in which one form of acupuncture was compared with another form of acupuncture or a different type of TCM (e.g. Chinese herbal medicine). Adjunctive treatments, either Western or TCM, were allowed as long as they had been given to both the acupuncture and control groups.

Types of outcome measures

Our primary outcomes were overall IBS symptom severity and IBS health‐related quality of life. Studies that did not report at least one of these outcomes were excluded. Although there is no consensus on how to define and measure clinically meaningful improvement in IBS (Irvine 2006), two recent evaluations of symptom and quality of life measures in IBS concluded that the IBS Adequate Relief question (IBS‐AR) (Mangel 1998) and the IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS‐SSS) (Francis 1997) possessed responsiveness, face and construct validity and were two of the most appropriate IBS symptom outcome measures, while the IBS Quality of Life measure (IBS‐QoL) (Patrick 1998) was the most extensively validated quality of life scale (Bijkerk 2003; Irvine 2006). When an individual study reported more than one overall IBS symptom severity measure, and either the IBS‐AR question or the IBS‐SSS scale was present, we gave preference to the IBS‐AR question for dichotomous outcomes and to the IBS‐SSS scale for continuous outcomes. When an individual study reported more than one quality of life measure, we gave preference to the IBS‐QoL if present. In cases where dichotomous outcomes such as improvement in IBS symptoms were presented in the form of multiple strata, such that we had the option of choosing cutpoints for the dichotomous outcome, we followed the model of Ford et al. and created a dichotomous measure in which positive outcomes were combined into a positive category (i.e. improvement) and the remaining strata constituted the negative category (i.e. no improvement) (Ford 2009a; Ford 2009b). In cases where investigators selected a cutpoint on a continuous scale to dichotomise between improvement and no improvement, we used the same cutpoint to define the dichotomous outcome (Ford 2009a).

Timing of outcome assessment

We extracted outcome data for both short and long‐term follow‐up points. Short‐term follow‐up was defined as three months or less after randomization, and long‐term follow‐up was defined as closest to six months but more than three months after randomization. When we observed multiple short‐term follow‐up points, we chose to extract the data closest to eight weeks after randomization, which coincided with end of treatment.

In randomized crossover trials, only outcomes from the first period were eligible for inclusion, due to the risk of carry‐over effects.

Adverse outcomes

We extracted data on adverse events when such data were present in the trial report.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To identify RCTs, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library, Issue 11, 2011), the Cochrane Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Functional Bowel Disorders Review Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field Specialized Register, MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, and the Chinese databases Sino‐Med, CNKI and VIP, during November 15 to 28, 2011. We developed search strategies for each database, based upon the original Medline search strategy constructed for the previous version of this review (Lim 2006). The strategies and results for each database are presented in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We considered all RCTs included in the previous version of this review for inclusion in this update. We scanned bibliographies of included articles and systematic reviews for further references. Finally, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify trials that may be relevant for future updates of this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All records identified by searching were independently screened by at least one author. The full text of potentially relevant reports was obtained and independently reviewed by two authors for eligibility. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

All data were independently extracted by two authors. In addition to the outcomes of overall IBS symptom severity and IBS health‐related quality of life for all time points reported, we extracted data pertaining to the methods of the trial, characteristics of the participants, details of the acupuncture and control interventions, and treatment outcomes. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. When reported data were incomplete or ambiguous, we requested additional information or clarification from the corresponding authors.

The method of selecting acupuncture points was categorized as fixed, flexible or individualized. For the fixed method, the same points are used for all participants. For the flexible method, a fixed formula is used and some additional points are chosen for the individual participant, based upon individual diagnosis or symptoms. In individualized point selection, the practitioner is free to choose any points.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011a). We used the following six criteria:

Adequate sequence generation: Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Allocation concealment: Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data: Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Selective reporting: Were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other risk of bias: Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

For each risk of bias question, an answer of ‘Yes’ indicates low risk of bias, ‘No’ indicates high risk of bias and ‘Unclear’ indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias. We used the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a) for judgments of ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Unclear’. For “Blinding”, we assigned sham‐controlled trials a judgment of "Unclear" unless we felt certain that the sham control was sufficiently credible in fully blinding participants to the treatment being evaluated (Manheimer 2007; Manheimer 2010). We assigned the "Yes" score to sham‐controlled trials that either 1) evaluated the credibility of the sham and found the sham to be indistinguishable from true acupuncture or 2) used a penetrating needle or a previously validated sham needle (i.e. Streitberger needle). There is no universally agreed‐upon instrument to measure outcomes in trials of IBS treatment, however overall IBS symptom severity is a key outcome in the majority of IBS trials and health‐related quality of life is an important secondary outcome that may legitimately be considered as a primary outcome measure (Irvine 2006). For the selective reporting item, we assigned the "Yes" score to trials that both 1) reported outcomes for overall IBS symptom severity or health‐related quality of life, or both, and 2) reported, at the end of treatment (and follow‐up, if done), the results of each outcome measured according to the Methods section. For “Other risk of bias”, we evaluated 2 other risk of bias‐related criteria: baseline comparability and use of an intention to treat analysis. For the baseline comparability criterion to be considered adequate, a comparison of the symptom scores between the treatment and control group(s) at baseline needed to be reported

Although we did not explicitly consider this to be a risk of bias measure, we also extracted data on the sources of funding for each trial.

As a first step in evaluating risk of bias, we copied information relevant for making a judgment on a criterion from the original publication into a table. If available, we also entered any additional information from the RCT authors into this table. Two review authors (EM and LSW or KC for English‐language trials, and LL and KC for Chinese‐language trials) independently judged whether the risk of bias for each criterion should be considered low, high or unclear. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

We used the GRADE approach to rate the overall quality of evidence for the primary outcomes. RCTs start as high quality evidence, but may be downgraded due to: (1) limitations in design and implementation (risk of bias), (2) indirectness of evidence, (3) inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity), (4) imprecision (sparse data), and (5) reporting bias (publication bias). The overall quality of evidence for each outcome was determined after considering each of these elements, and categorized as high quality (i.e. further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect); moderate quality (i.e. further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate); low quality (i.e. further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate); or very low quality (i.e. we are very uncertain about the estimate) (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011).

Assessment of acupuncture adequacy

Two acupuncturists (LL, XS) who have a combined clinical experience of nearly fifty years in treating IBS with acupuncture, and who have previously worked on RCTs of acupuncture, independently assessed the adequacy of the acupuncture administered in the trials. Six aspects of the acupuncture intervention were assessed for adequacy: choice of acupuncture points; total number of sessions; treatment duration; treatment frequency; needling technique; and acupuncturist's experience (Furlan 2005). The likelihood of the sham intervention to have physiological activity was also assessed, using an open‐ended question. The acupuncturist assessors were provided with only the part of the publications that described the acupuncture and sham procedures, so that their assessments could not be influenced by the results of the trials. To test the success of blinding the assessors to the study publication and results, we asked the assessors to guess the identity of each study being assessed. The acupuncturists assessed adequacy independently and achieved consensus by discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

Dichotomous outcomes (e.g. adequate symptom relief) were expressed as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes on the same scale (e.g. symptom severity as measured by the IBS‐SSS), the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. For continuous outcomes on different scales that assess the same underlying construct (e.g. different measures of symptom severity), the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Dealing with missing data

In cases where participants were lost to follow‐up, and intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses were conducted using baseline observations carried forward, multiple imputation, or other methods to impute the missing values, we used the ITT data for our primary analysis, if group means and standard deviations were present or could be estimated, and if the method for imputing data was described and did not bias the effect size calculation. If only the ITT data were reported, and not the available case data, we used the ITT data. When statistics such as standard deviations were not present in the study report, we used the methods suggested in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b) to calculate or estimate the values of the missing statistics.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003), which indicates the proportion of variability across trials not explained by chance alone. Roughly, I2 values of 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and I2 values of 75% to 100% represent considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2003; Deeks 2011). We also checked for heterogeneity by visual examination of forest plots. When heterogeneity was observed, we attempted to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study characteristics, such as study population, type and duration of treatment, and type of control intervention.

Data synthesis

Data from individual trials were combined when the trials were sufficiently similar in terms of control interventions (sham (placebo) acupuncture, no treatment, another active treatment, or acupuncture as adjuvant to another treatment), outcome measures (overall IBS symptom severity, IBS‐related quality of life), and timing of outcome assessment (short‐term, long‐term). For pooled data, summary test statistics were calculated using a random‐effects effect model to account for expected heterogeneity. If the I2 statistic was greater than or equal to 50%, the summary measures of effect were interpreted with caution, and heterogeneity between trials was investigated.

For the acupuncture versus sham comparison, data for the symptom severity outcome were presented in some studies as dichotomous data (e.g. adequate symptom relief) and in other studies as continuous data (e.g. symptom severity as measured by the IBS‐SSS). We re‐expressed odds ratios as standardized mean differences (SMDs), thereby allowing dichotomous and continuous data to be pooled together for this comparison/outcome (Deeks 2011), using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses using fixed‐effect and random‐effects meta‐analytic estimates, and for available case and imputed data, when such data were available.

To assess whether treatment effects varied with internal validity of studies or treatment adequacy, we attempted sensitivity analyses to evaluate whether any pooled results that were significant in analyses of all the trials remained significant when we restricted them to trials judged adequate on each of the risk of bias and treatment‐adequacy criteria.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

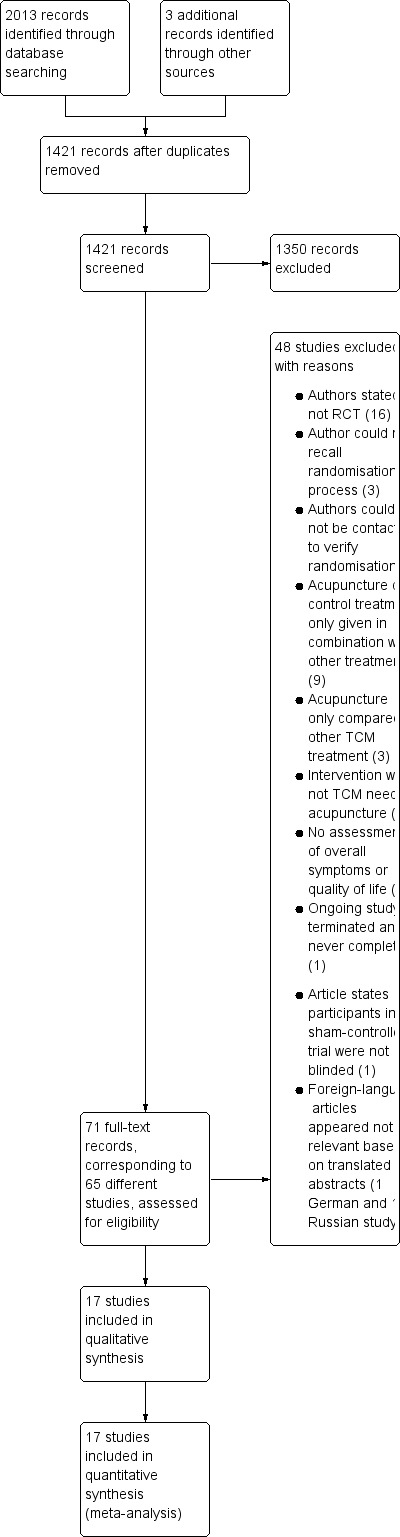

Figure 1 shows details of the search and selection process.

1.

Flow of studies through selection process.

Included studies

Seventeen studies with a total of 1806 participants were included (Liu 1997; Lowe 2000; Forbes 2005; Schneider 2006; Reynolds 2008; Xiong 2008a; Anastasi 2009; Chen 2009; Lembo 2009; Li 2009; Xue 2009; An 2010; Liu 2010; Shi 2010; Zeng 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011; See 'Characteristics of included studies' table). Five of the studies were small, including between 29 and 59 participants (Lowe 2000; Forbes 2005; Schneider 2006; Reynolds 2008; Anastasi 2009). The largest study included 230 participants (Lembo 2009). The studies were conducted in the US (Anastasi 2009; Lembo 2009), the UK (Forbes 2005; Reynolds 2008), China (Liu 1997; Xiong 2008a; Chen 2009; Li 2009; Xue 2009; An 2010; Liu 2010; Shi 2010; Zeng 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011), Canada (Lowe 2000) and Germany (Schneider 2006). The studies conducted in China were published in Chinese, and the remaining studies were published in English. All were published as full articles, with the exception of the Lowe 2000 trial, which was published as an abstract. Three of the studies included in our 2006 Cochrane review (Liu 1995; Liao 2000; Fireman 2001) were excluded from this update because either an adequate randomization process was not used (Liao 2000; Fireman 2001) or the randomization procedure could not be recalled by the author (Liu 1995). Appendix 2 includes an overview description of trial characteristics and acupuncture and control interventions.

Excluded studies

The 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table lists the studies that we excluded as well as the reasons for exclusion.

Risk of bias in included studies

All sham‐controlled trials reported adequate methods for sequence generation and allocation concealment, and all trials except the Lowe 2000 trial adequately described and addressed losses to follow‐up. The Lowe 2000 trial was reported only as an abstract, and the completeness of outcome data ascertainment could not be assessed.

In 4 out of 5 of the sham‐controlled trials (Forbes 2005; Schneider 2006; Lembo 2009; Anastasi 2009), we judged that the shams were likely to be indistinguishable from true acupuncture. In two of these sham‐controlled trials (Schneider 2006; Lembo 2009), the Streitberger placebo needle was used, which has been previously validated as a sufficiently credible sham (Streitberger 1998). The Streitberger needles were placed close to the genuine acupuncture points in both trials. In both trials, the participants were acupuncture naïve. In the Anastasi 2009 trial, the investigators superficially inserted needles at non points which were 2 to 3 cm away from the true points, and placebo moxibustion was performed above the same sham points without generating a heat sensation. In the Forbes 2005 trial, acupuncture needles were inserted at areas on the body that do not correspond to acupuncture points and are deemed to have no therapeutic value. The points and needling technique were varied somewhat each week, as was also done in the true acupuncture group, who received individualized point selection. In each of these four trials, the sham was likely to be indistinguishable from true acupuncture. For the Lowe 2000 trial, the sham was judged to have been potentially detectable as a fake treatment by the trial participants. The sham procedure involved tapping a blunt needle on the skin and then taping the needle in place. Although this procedure was described as “validated” in the Lowe 2000 abstract, we are unaware of a validation study for this procedure. Also, in the trial report there was no description of whether or not the patients were required to have never previously used acupuncture, and there were no reported tests for checking the success of the blinding.

In the trials comparing acupuncture with another active treatment (Liu 1997; Li 2005; Xue 2009; An 2010; Liu 2010; Shi 2010; Zeng 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011), no (specific) treatment (Reynolds 2008; Lembo 2009), or evaluating acupuncture as an adjuvant to another treatment received by all trial participants (Liu 1997; Xiong 2008a; Chen 2009; Li 2009; Liu 2010), blinding of participants was not possible, and this likely represents the major risk of bias in these trials. In these pragmatic trials, there were also risks of bias associated with the randomization procedure and the follow‐up of patients. Although all of these trials reported to use a random sequence generation for the treatment assignment, 5 of these trials (Liu 1997; Chen 2009; Li 2009; Xue 2009; Liu 2010) reported an equal number of participants in each group, which would be unlikely to occur by chance with the simple randomization methods used in these trials. The authors of the Chen 2009 and Li 2009 trials confirmed in telephone interviews that a few patients were non‐randomly assigned to achieve identical sized treatment groups. The authors of the other 3 trials (i.e. Liu 1997; Xue 2009; Liu 2010), were unable to explain how equal sample sizes were achieved. In 6 of the Chinese language trials (Liu 1997; Xiong 2008a; Chen 2009; Li 2009; An 2010; Liu 2010), incomplete outcome data were not adequately addressed. In four trials (Liu 1997; Xiong 2008a; Li 2009; An 2010), the authors did not report the numbers of drop‐outs in the publication, and did not have records of the numbers of drop‐outs to provide during the telephone interviews. For the Liu 2010 trial, the authors reported no drop‐outs, which would be unusual in a 4 week trial of 300 participants. For the Chen 2009 trial, the authors endeavoured to maintain equal group sizes, by eliminating participants who withdrew during the trial and replacing them with new patients, and the number of such replacements was not recorded by the author.

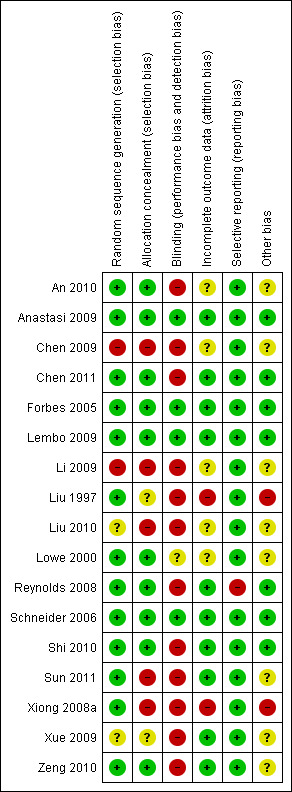

A 'risk of bias graph' displays the judgments for each risk of bias item for each included study (Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Acupuncture adequacy

All trials included in this review were judged adequate on "Choice of acupoints" and “Needling technique”, except for the Lowe 2000 trial, for which the acupuncture points and needling technique were not reported. The acupuncture frequency was judged adequate in all trials except for the Forbes 2005 and Reynolds 2008 trials. All trials that reported on the acupuncturist’s experience were judged adequate, except for the Lowe 2000 trial, for which a physiotherapist with Level 1 accreditation in acupuncture was used, which was judged inadequate. Also, for two trials (Forbes 2005; Anastasi 2009), the acupuncture adequacy assessors noted that the sham needling may have had physiologic activity. The results of the acupuncture adequacy assessments are reported in Appendix 3.

Effects of interventions

The GRADE analyses for the main comparisons are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

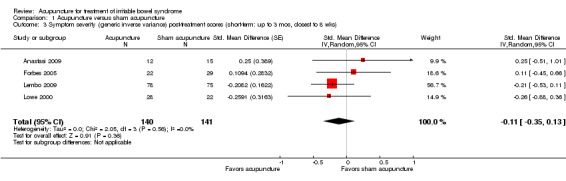

Acupuncture versus sham

Five trials (Lowe 2000; Forbes 2005; Schneider 2006; Anastasi 2009; Lembo 2009) compared the effects of acupuncture and sham acupuncture. The Schneider 2006 trial did not measure the outcome of symptom severity and the Anastasi 2009 and Lowe 2000 trials did not report quality of life. The 5 individual sham‐controlled RCTs, and also the pooled analyses, found no statistically significant differences between acupuncture and sham acupuncture for the outcomes symptom severity or quality of life.

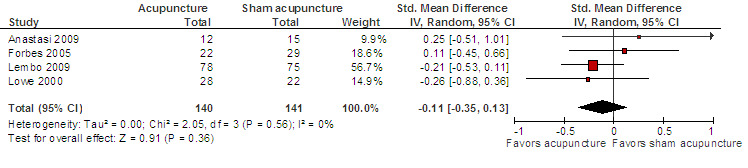

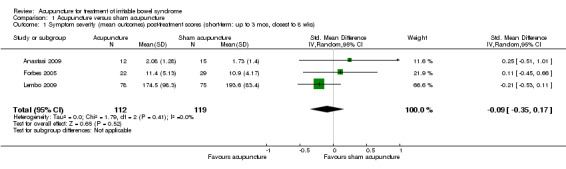

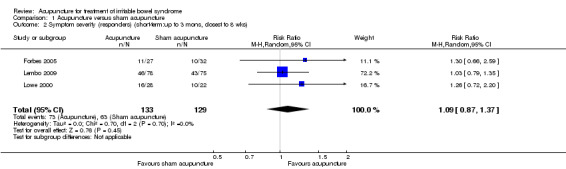

Data for the symptom severity outcome were presented as dichotomous data (e.g. adequate symptom relief) in some studies and as continuous data (e.g. symptom severity as measured by the IBS‐SSS) in other studies. We re‐expressed odds ratios as standardized mean differences (SMDs), thereby allowing dichotomous and continuous data to be pooled together for this comparison/outcome (Deeks 2011), using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan. This pooled analysis for symptom severity included 4 studies and 281 patients. There was no statistically significant difference between acupuncture and sham acupuncture (SMD ‐ 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.13; See Figure 3). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (less than 400 events; See Table 1). Three studies (231 patients) reported symptom severity as a continuous outcome. There was no statistically significant difference between acupuncture and sham acupuncture (SMD ‐ 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.17; See Analysis 1.1). Three studies (262 patients) reported on adequate symptom relief. Fifty‐five per cent of patients in the acupuncture group had adequate symptom relief compared to 49% of patients in the sham acupuncture group. There was no statistically significant difference between acupuncture and sham acupuncture (RR 1.09, 95% CI is 0.87 to 1.37; See Analysis 1.2).

3.

Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture: Symptom severity

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (mean outcomes) post‐treatment scores (short‐term: up to 3 mos, closest to 8 wks).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 2 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term:up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

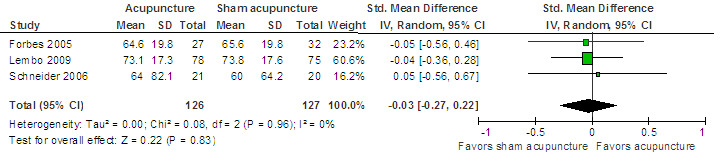

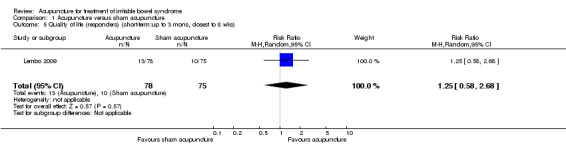

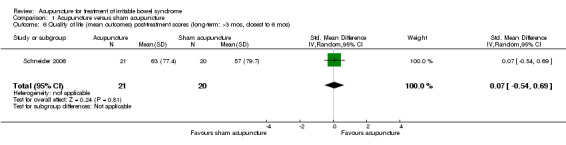

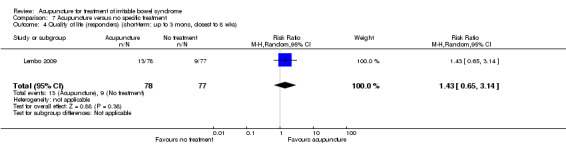

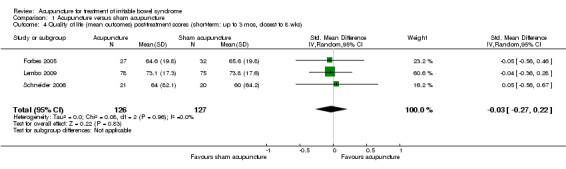

For the acupuncture versus sham comparison, all 3 studies (253 patients) that included the quality of life outcome reported continuous data. There was no statistically significant difference in quality of life scores between acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups (SMD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.22; See Figure 4). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (less than 400 events; See Table 1). One study reported quality of life as a dichotomous outcome (153 patients). Seventeen per cent of acupuncture patients had an improvement in quality of life compared to 14% of sham acupuncture patients. There was no statistically significant difference (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.68; See Analysis 1.5). For both outcomes, the results of all sham‐controlled trials were homogeneous (I2=0%; See Figure 3; Figure 4). One trial (Schneider 2006) assessed quality of life at long‐term follow‐up, and this trial did not find a difference in effect between acupuncture and sham acupuncture at six months (SMD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.54 to 0.69; 41 patients; See Analysis 1.6).

4.

Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture: Quality of life

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 5 Quality of life (responders) (short‐term:up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 6 Quality of life (mean outcomes) post‐treatment scores (long‐term: >3 mos, closest to 6 mos).

Acupuncture versus other active treatments, as an adjuvant to other active treatments, and versus no specific treatment

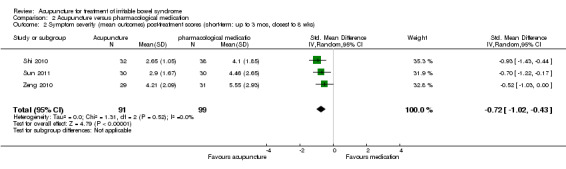

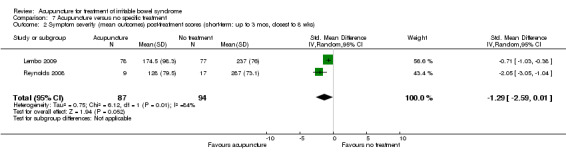

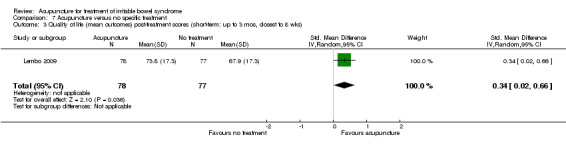

All trials reported dichotomous outcome data for all non‐sham comparisons, We pooled these trials as relative risks (see Figure 5). In cases where continuous outcome data were also reported in the trials, we pooled the available continuous data as well, and present these as additional forest plots (See Analysis 2.2; Analysis 7.2; Analysis 7.3).There were no important differences between continuous and dichotomous results for any comparison or outcome.

5.

Acupuncture versus another active treatment, as adjuvant to another active treatment, or compared to no specific treatment: Symptom severity

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture versus pharmacological medication, Outcome 2 Symptom severity (mean outcomes) post‐treatment scores (short‐term: up to 3 mos, closest to 8 wks).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Acupuncture versus no specific treatment, Outcome 2 Symptom severity (mean outcomes) post‐treatment scores (short‐term: up to 3 mos, closest to 8 wks).

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Acupuncture versus no specific treatment, Outcome 3 Quality of life (mean outcomes) post‐treatment scores (short‐term: up to 3 mos, closest to 8 wks).

Acupuncture versus other active treatments

The five trials (Xue 2009; Shi 2010; Zeng 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011) that compared acupuncture to pharmacological therapies for IBS found that participants receiving acupuncture reported a significantly greater improvement in symptom severity than participants receiving pharmacological therapies. Eighty‐four per cent of acupuncture patients reported improvement in symptom severity compared to 63% of patients in the pharmacological treatment group. (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.45, 449 patients, See Figure 5; Analysis 2.1). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome was low due to risk of bias (i.e. all studies were not blinded) and sparse data (less than 400 events; See Table 2). Three studies (190 patients) reported symptom severity as a continuous outcome. Acupuncture patients had significantly lower mean symptom severity scores than patients in the pharmacological treatment group (WMD ‐0.72, 95% CI ‐1.02 to ‐0.43; See Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture versus pharmacological medication, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

Two studies (181 patients) compared acupuncture with probiotics (An 2010; Liu 2010). There was no statistically significant difference in improvement between patients treated with acupuncture and probiotics (Bifidobacterium). Seventy‐six per cent of acupuncture patients improved compared to 71% of probiotic patients (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.27; See Figure 5; Analysis 3.1). Participants receiving acupuncture were not more likely to have responded to treatment than those treated with psychotherapy (Liu 1997). Eight‐four per cent of patients in the acupuncture group improved symptomatically compared to 80% of patients in the psychotherapy group (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.26, 100 patients (See Figure 5; Analysis 4.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture versus Bifidobacterium, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acupuncture versus psychotherapy, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

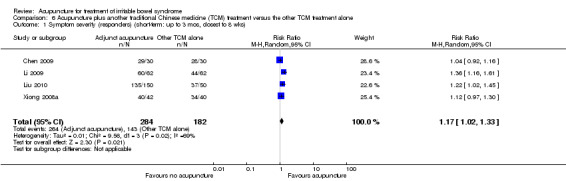

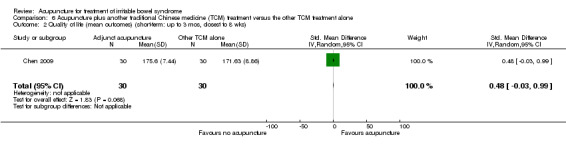

Acupuncture as an adjuvant to other active treatments

Five trials (Liu 1997; Xiong 2008a; Chen 2009; Li 2009; Liu 2010) compared the combination of adjuvant acupuncture plus another IBS treatment received by all trial participants to the other IBS treatment alone. Patients who received acupuncture and psychotherapy were significantly more likely to have improvements in symptom severity than patients who received psychotherapy alone. Ninety‐six per cent of patients in the combined acupuncture and psychotherapy group improved compared to 82% of patients in the psychotherapy group (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.29, 2 studies, 182 patients; See Analysis 5.1). Pooled results (4 studies, 466 patients) showed that participants receiving adjuvant acupuncture were significantly more likely to have reported improvement than those treated with another Chinese medicine treatment alone (although there was substantial heterogeneity of results and high risks of bias in these trials). Ninety‐three per cent of patients in the adjuvant acupuncture group reported improvement in symptom severity compared to 79% of patients who received traditional Chinese medicine alone (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.33; See Figure 5; Analysis 6.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Acupuncture plus psychotherapy versus psychotherapy alone, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Acupuncture plus another traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treatment versus the other TCM treatment alone, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mos, closest to 8 wks).

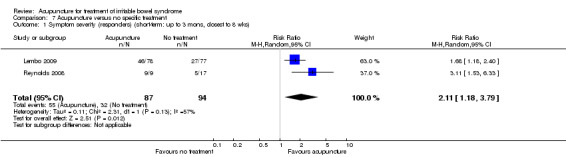

Acupuncture versus no specific treatment

Two trials (Lembo 2009; Reynolds 2008) compared the effects of acupuncture to no specific treatment. In both trials, all participants were allowed to continue receiving standard medical care for IBS, including any prescribed medications, but control group participants were not assigned to any additional IBS treatment. Both of these trials showed a statistically significant benefit of acupuncture for improving IBS symptom severity, although there was substantial heterogeneity of results between the 2 trials (181 patients). Sixty‐three per cent of patients in the acupuncture group reported improvement in IBS symptom severity compared to 34% of patients in the no treatment group (RR 2.11, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.79; See Figure 5; Analysis 7.1). At short‐term follow‐up in a single trial (Lembo 2009), post‐treatment quality of life scores showed acupuncture to be associated with significant improvement for the continuous quality of life measure (Analysis 7.3), but not the dichotomous quality of life measure (Analysis 7.4).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Acupuncture versus no specific treatment, Outcome 1 Symptom severity (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Acupuncture versus no specific treatment, Outcome 4 Quality of life (responders) (short‐term: up to 3 mons, closest to 8 wks).

Sensitivity analyses

For the sham‐controlled trials, sensitivity analyses based on risk of bias or treatment adequacy‐related variables would be uninformative because all sham‐controlled trials had similar results and no combination of these trials resulted in a pooled statistically significant benefit, for either the symptom severity or quality of life outcome. For the five trials comparing acupuncture versus pharmacological therapies, restriction to the four trials that compared acupuncture versus evidence‐based (Ruepert 2011) antispasmodic pharmacological therapies (Shi 2010; Zeng 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011) had similar results (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.37, 249 participants, I2=0). For the other comparisons, there were too few trials to attempt sensitivity analyses (Deeks 2011).

For the Forbes 2005 trial, which reported both intent‐to‐treat (ITT) and available case data for the symptom severity outcome, a sensitivity analysis using ITT values instead of the available case values did not result in important differences in the SMDs for this trial. The statistical significance of the pooled results did not change depending on whether the random‐effects or fixed‐effect analyses were used.

Safety of acupuncture

Nine trials included descriptions of adverse events associated with acupuncture (Forbes 2005; Reynolds 2008; Anastasi 2009; Lembo 2009; An 2010; Liu 2010; Shi 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011). For 8 of these 9 trials, no serious adverse events were reported, while the Shi 2010 trial reported that 1 participant in the electro‐acupuncture group withdrew because of syncope (see Appendix 4).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Five sham‐controlled RCTs have tested the effects of acupuncture for treating IBS, and four of these trials used adequate methods for randomization and blinding, and had few withdrawals or drop‐outs. None of these sham‐controlled RCTs found a statistically significant benefit of acupuncture relative to sham acupuncture for the outcomes symptom severity or quality of life. Similarly, pooling the data from these sham‐controlled trials did not result in statistically significant benefits of acupuncture for either outcome. Five unblinded Chinese‐language comparative effectiveness trials found that patients receiving acupuncture reported greater improvements in IBS symptoms compared to patients receiving pharmacological therapies for IBS.

How should physicians, researchers, and policy‐makers interpret these seemingly contradictory trial findings, i.e., that acupuncture had no greater effects than a sham placebo, but acupuncture did show greater effects compared with two pharmacological treatments (pinaverium bromide and trimebutine maleate) that have both previously been shown to be superior to a placebo (Jailwala 2000; Ruepert 2011)? First, both the comparative effectiveness trials and the sham‐controlled trials have important limitations that complicate their interpretations. An important limitation of the trials comparing acupuncture to pharmacological therapy is that the patients in these trials are not “blinded” to whether they received acupuncture or drug therapy, and expectation effects (i.e. defined as ‘‘the impact of expectations on subjective outcomes’’ (Flum 2006)), may differ between acupuncture and drug treatment (Kaptchuk 2006; Manheimer 2007; O'Connell 2009). That is, if patients randomized to acupuncture expect greater improvements than patients randomized to drugs, the greater expectations of benefits from acupuncture may contribute to a larger placebo effect (i.e. a larger improvement in symptoms due to an inert treatment, or an inert component of a treatment) in the acupuncture group than in the drug treatment group. Because of the possibility of differential expectations of a benefit from acupuncture versus drugs in these trials (Linde 2007; Manheimer 2007; O'Connell 2009), it cannot be determined whether any of the reported benefits of acupuncture are due to a larger biological effect of acupuncture needling relative to drugs, or rather due entirely to the impact of the trial participants’ greater expectations of a benefit of acupuncture, on the subjective outcomes that they reported.

A limitation of the sham‐controlled trial design is that the high placebo effects of sham acupuncture may preclude the detection of any small, true biological benefits of true acupuncture relative to a credible sham acupuncture control, when subjective patient self reports are the outcome measures used. Two “methodological” trials have evaluated the placebo effects of sham acupuncture, on both subjective and objective outcome measures (Kaptchuk 2006; Wechsler 2011). One such methodological trial (Kaptchuk 2006), designed to compare placebo effects of placebo pills and sham acupuncture, found that, relative to placebo pills, sham acupuncture was more credible as an authentic treatment and resulted in higher subjective patient self reports of improvement. This trial also found that the placebo effect was confined to self‐reported, subjective outcomes (e.g. pain) and that there was no placebo effect (i.e. no improvement from baseline) for either the placebo acupuncture or placebo pill on the objective outcome that they measured (i.e. grip strength). Another recent methodological trial (Wechsler 2011) compared albuterol (i.e. a proven asthma drug) versus sham acupuncture for asthma patients, and found that while only the albuterol had a biological effect on the objective outcome of airway flow, both the sham acupuncture and albuterol groups had dramatic and comparable improvements from baseline on the subjective outcome of patient self‐reports of improvement, such that the albuterol showed no benefit relative to the sham acupuncture on self‐reported improvement.

These methodological studies suggest that relying exclusively on subjective patient reports, such as those used as outcomes in IBS trials, may result in a failure to detect small biological effects of an active treatment (i.e. true acupuncture) relative to a highly credible, but physiologically inert, sham acupuncture control. Thus, while the high placebo effects among IBS patients (Spiller 1999) make it difficult to show that any pharmacological treatment is superior to an inert placebo pill, demonstrating such an effect may be even more difficult when the placebo control is sham acupuncture.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

How externally valid are the results of this review? Namely, do the types of interventions investigated in these studies represent current best practice of acupuncture treatment for IBS? Assessing the adequacy of the acupuncture treatment procedure is important because, for instance, basing conclusions about acupuncture efficacy on a suboptimal procedure is “analogous to a pharmaceutical trial formulating conclusions about the efficacy of a drug based on an inadequate dose” (Ezzo 2001).

For the sham‐controlled trials, a possible reason for the lack of benefit might be explained by the fact that only the Forbes 2005 trial used individualized acupuncture, in which the acupuncturist tailors the point selection individually to each patient, and which is the typical approach used in everyday acupuncture clinical practice. Among the other four sham‐controlled trials that did not use an individualized approach, two (Anastasi 2009; Lembo 2009) used a “flexible formula” approach, and two (Lowe 2000; Schneider 2006) used a fixed formula approach. With the fixed formula approach, the same acupoints are used for all trial participants. With the flexible formula approach, some acupoints are required for all patients but other acupoints could be selected based on the individual patient’s specific constellation of symptoms. In terms of RCT design, an advantage of the flexible formula approach over the entirely individualized approach is that using a flexible formula allows for the results of the RCT to be relatively reproducible and externally valid (Lembo 2009) while at the same time allowing for some discretion of the acupuncturist to individualize point selection. In an RCT setting, this flexible formula approach is also easier to blind than an individualized approach, because individualization requires increased contact between the patient and the acupuncturist, which increases the risk of unblinding. Thus, although four trials did not use individualized acupuncture, the two acupuncturist systematic reviewers who assessed the adequacy of the acupuncture judged that, when reported, the point selection, the needling technique, and the experience of the acupuncturists to be adequate in all four of these trials. For the reasons described above, it seems unlikely that the use of a flexible or fixed formula instead of individualized acupuncture in four of the five sham‐controlled trials is the reason for the lack of a benefit.

Alternative explanations for the negative results in these trials might include an inadequate number of treatment sessions, an insufficient duration of treatment, or an inadequate treatment frequency. All sham‐controlled trials were judged by our acupuncture adequacy assessors to have used an adequate number of treatment sessions and a sufficient duration of treatment. Only the Forbes 2005 sham‐controlled trial was judged to use an inadequate treatment frequency because this trial involved only one acupuncture session per week (for 13 weeks), which even though judged inadequate, probably still well reflects clinical practice in Western countries. The other sham‐controlled trials all used two sessions per week, which was judged by the acupuncture adequacy assessors as an adequate treatment frequency, so it seems unlikely that an inadequate frequency of treatments explains the lack of benefit. While one trial (Lembo 2009) did not meet the Rome criteria recommendations for a minimum treatment duration of four weeks (Irvine 2006), the acupuncturist adequacy assessors judged that this trial’s three week treatment duration, with twice weekly treatments, was adequate. Although the acupuncture assessors judged the treatment frequency of the sham‐controlled trials to be largely adequate, the Chinese language comparative effectiveness trials used a much greater treatment frequency, with daily acupuncture treatments used in 9 out of 11 of these comparative effectiveness trials, and in all five of these trials that compared acupuncture to drug treatment. The higher acupuncture treatment frequency in the Chinese comparative effectiveness trials, relative to the sham‐controlled trials, might also help explain the different benefits of acupuncture relative to the controls in these two subsets of trials.

Quality of the evidence

For the sham‐controlled trials, the continuous outcomes symptom severity and quality of life were rated as 'moderate' quality using the GRADE criteria because of sparse data (i.e. less than 400 events). This indicates that further research could have an impact on our confidence in the estimates of effect and may change the estimates.

Four out of the five sham‐controlled trials in this review (Forbes 2005; Schneider 2006; Anastasi 2009; Lembo 2009) did not have limitations related to a risk of bias criterion. Each of these four trials used adequate randomization (which was not reported in the publications but ascertained by contacting the corresponding authors), each adequately addressed incomplete outcome data, and each used a sham control that was likely to adequately blind participants to the treatment received. Only the Lowe 2000 trial used a sham intervention that might not have been sufficiently believable as true acupuncture, such that this sham could adequately blind study participants as to whether they were receiving true acupuncture or a sham. However, if the sham acupuncture group participants realized they were getting a sham treatment, then this unblinding to the treatment received would likely have resulted in an overestimate of the effects of true acupuncture in this trial (Higgins 2011a).

A potential methodological limitation is that two of the five sham‐controlled RCTs (Forbes 2005; Anastasi 2009) used a sham control that involved skin penetrating needles inserted at non‐acupuncture points, that the acupuncture assessors in our review judged to have potential weak physiological activity that might influence the outcome, and which might therefore have biased these two RCTs to the null. However, we would not expect this to explain the lack of benefit of acupuncture relative to sham, both because these two shams were judged to have potential for only weak physiological activity and also because the other three sham‐controlled RCTs (Lowe 2000; Schneider 2006; Lembo 2009) used non‐penetrating shams that were judged to be unlikely to have physiological effects. These three RCTs also found no benefit of acupuncture relative to sham.

The quality of the evidence is also limited by the fact that all sham‐controlled trials except the Lembo 2009 study had small sample sizes and were each underpowered to detect a small benefit of the acupuncture protocol evaluated. Although these trials may have been adequately powered to detect a moderate to large benefit of acupuncture relative to sham, an effect size of this magnitude may have been unreasonable to expect, considering that specific 5HT4 agonists (i.e. tegaserod) and 5HT3 antagonists (i.e. alosetron and cilansetron), which are the only treatments with “good quality of evidence” for treating IBS (Brandt 2009) provide only a modest benefit. Although a meta‐analysis of the five sham‐controlled trials increases the statistical power to detect an effect, a limitation of pooling trials with different acupuncture protocols is that we cannot rule out the possibility that larger trials or meta‐analyses focusing on one of these protocols might show a benefit of treatment. In addition, although the meta‐analysis point estimates suggest no effect, the 95% confidence intervals include the possibility that there could be small benefits which could be important to patients. A final limitation of the sham‐controlled trial evidence base, related to the small sample sizes, and also the heterogeneity of participants, is that these trials did not restrict eligibility to specific subtypes of IBS patients, and the proportions of patients with different IBS subtypes differed across trials. An individual patient data meta‐analysis would be necessary to address whether acupuncture has different effects on different subtypes of IBS patients, although the relatively small numbers of patients would be unlikely to provide a confident answer to this question.

For the Chinese language comparative effectiveness trials the dichotomous outcome symptom severity was rated as 'low' quality using the GRADE criteria because of high risk of bias (e.g. none of the studies were blinded) and sparse data (i.e. less than 400 events). This indicates that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

In the Chinese language comparative effectiveness trials, in addition to the primary risk of bias associated with the absence of patient blinding, there were also risks of bias associated with the randomization procedure and the follow‐up of patients. Notably, for five of these trials (Liu 1997; Chen 2009; Li 2009; Xue 2009; Liu 2010), there were equal sized treatment groups, and during our telephone surveys the trial investigators either stated that some participants were non‐randomly assigned to treatment or could not adequately explain how the equal group sizes were achieved. This raises the possibility that the randomization might not have been adequately generated or concealed (Schulz 2002). The notion that randomized trials should have equal numbers in each treatment group has been shown to commonly lead clinical trial investigators to force equality by unscientific means (Schulz 2002). Indeed, previous methodological reviews of this issue have found that over one‐half of trials using simple, unrestricted randomization schemes report equal numbers in each group (Adetugbo 2000; Schulz 2002), and 88% of reported randomized trials have been shown to exclude some randomized participants from their analysis (Adetugbo 2000). The Chinese trials with high risks of bias associated with randomization or the accounting of randomized patients in the outcomes assessments evaluated acupuncture as an adjuvant to either another Chinese medicine treatment or psychotherapy; or compared acupuncture to psychotherapy, probiotics, or a drug not indicated or commonly used for IBS (i.e. sulfasalazine (Xue 2009)). Therefore, the findings from these studies should be considered to be hypothesis generating, and are not included in our overall conclusions. In contrast, there was a lower overall risk of bias in the four comparative effectiveness trials that found acupuncture to be more effective than two antispasmodic pharmacological therapies shown to be effective for IBS (Jailwala 2000; Ruepert 2011) (i.e. pinaverium bromide (Chen 2011; Shi 2010; Sun 2011) and Trimebutine maleate (Zeng 2010)). These four studies were rated as high risk of bias due to lack of blinding but were otherwise methodologically sound studies.

Potential biases in the review process

Potential biases in the review process were avoided by conducting comprehensive searches to identify all relevant studies, conducting dual and independent data extraction, and blinding the acupuncture treatment adequacy assessors to the results of the trials they assessed. In addition, we contacted the corresponding authors of all potentially eligible, claimed "randomized" trials published in Chinese language journals, as well as English language RCTs that did not include details about randomization methods in their published reports, to confirm their authenticity.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The conclusions of this review have changed from the conclusions of our 2006 Cochrane review (Lim 2006) which is the only other systematic review focused on acupuncture for IBS. While our 2006 Cochrane review found that it is "inconclusive whether acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture", the current review concludes that currently available sham‐controlled trials suggest that acupuncture is not superior to sham acupuncture for reducing symptom severity or improving quality of life in patients with IBS. Comparative effectiveness Chinese trials have found that patients report greater benefits from acupuncture than from pharmacological therapies. However, the results of the comparative effectiveness studies should be interpreted with caution due to risk of bias (lack of blinding) and expectation effects.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

People with IBS have few treatment options available. Pharmacological therapies provide modest benefits (Ford 2009a), can have high costs, and some of the newer drugs have been withdrawn from the market because of adverse events (Thompson 2001; Pasricha 2007). Safe, non‐pharmacological therapies that may allow patients to feel more empowered and more in control of their symptoms should be evaluated for effectiveness. However, evaluating complex non‐pharmacological therapies for IBS (e.g. mindfulness meditation (Gaylord 2011) or hypnotherapy (Lindfors 2012)) poses challenges, particularly in regards to selecting a placebo control or a credible alternative treatment control.

While acupuncture can theoretically be compared with a sham acupuncture “placebo” control, a fundamental challenge has been developing a sham acupuncture control that is sufficiently believable to patients so as to be indistinguishable from true acupuncture, and yet at the same time not so similar to true acupuncture that the sham has a therapeutic effect of its own and is therefore not an inert placebo. The sham acupuncture controls used in four of the five sham‐controlled trials in this review appeared to be believable as authentic treatments (Forbes 2005; Schneider 2006; Lembo 2009; Anastasi 2009), but two of the five sham‐controlled trials used sham controls that might have had weak physiological activity (Forbes 2005; Anastasi 2009), and therefore these shams may not have been completely inert placebos. While none of the sham‐controlled trials showed a benefit of acupuncture relative to sham acupuncture, it is still not clear whether these findings are because acupuncture has no true biological effect above and beyond a placebo; or whether instead acupuncture has small biological effects, but the small sample sizes and heterogeneity of participants and interventions in these trials precluded detecting a statistically significant pooled benefit of acupuncture over sham; or whether any biological effects of true acupuncture cannot be detected because they are overridden and obscured by the large placebo effects of the sham control (Kaptchuk 2006; Wechsler 2011). Evidence from four Chinese language comparative effectiveness trials (Shi 2010; Zeng 2010; Chen 2011; Sun 2011) showed acupuncture to be superior to two antispasmodic drugs (pinaverium bromide and trimebutine maleate), both of which have consistently been shown to provide a modest benefit in high quality trials (Jailwala 2000; Ruepert 2011), although neither is approved for treatment of IBS in the United States (Jailwala 2000). Patient preferences and expectations may partly explain the positive findings of these trials comparing acupuncture to drug treatment. That is, if the trial participants had pretreatment preferences for acupuncture over drugs, these preferences may have influenced the participants’ later assessments of their subjective states, as reported on the patient‐reported outcome measures used (Kalauokalani 2001; Linde 2007; Manheimer 2007; O'Connell 2009).

In addition to efficacy, safety and costs are other considerations. Safety is best determined with large prospective surveys of practitioners and three such surveys (MacPherson 2001; White 2001; Melchart 2004) show that serious adverse events after acupuncture are rare. There was one adverse event associated with acupuncture in the nine trials that reported this outcome (Forbes 2005; Reynolds 2008; Anastasi 2009; Chen 2009; Lembo 2009; An 2010; Liu 2010; Shi 2010; Sun 2011), although relatively small sample sizes limit the usefulness of these safety data. Finally, patients would also need to consider costs because acupuncture treatment often needs to be paid for out of pocket.

Implications for research.

Considering that our meta‐analysis found no differences between acupuncture and sham, and also considering that there are limited resources available to conduct trials of acupuncture, a non‐proprietary therapy, additional sham‐controlled trials of acupuncture among IBS patients should not be a high priority in acupuncture research, at least until the large, ongoing sham‐controlled trial, which is expected to complete data collection in March 2013, is published (Anastasi). This trial (n = 171) (Anastasi) compares a sham control with two different acupuncture test treatment groups, one test group using a fixed formula and the other test group using an individualized treatment approach, for patients with diarrhea‐predominant IBS (See Characteristics of ongoing studies). If this trial shows no benefit of acupuncture relative to the sham, then the need for additional sham‐controlled trials would seem questionable. However, if this ongoing sham‐controlled trial shows a benefit, then it would certainly be warranted to conduct future sham‐controlled trials building upon the results of this trial (e.g. restriction to diarrhea predominant IBS patients; using the same acupoints as used in this trial). Such future sham‐controlled trials should use non‐penetrating, but demonstrably credible, shams to control for placebo effects, and ideally these sham needles should be placed far away from the true acupuncture points.