Comprehensive analysis of the intranuclear territories and motion of budding yeast chromosome XII loci suggests that long-range chromosome architecture is mainly determined by the physical principles of polymers.

Abstract

Chromosomes architecture is viewed as a key component of gene regulation, but principles of chromosomal folding remain elusive. Here we used high-throughput live cell microscopy to characterize the conformation and dynamics of the longest chromosome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (XII). Chromosome XII carries the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) that defines the nucleolus, a major hallmark of nuclear organization. We determined intranuclear positions of 15 loci distributed every ∼100 kb along the chromosome, and investigated their motion over broad time scales (0.2–400 s). Loci positions and motions, except for the rDNA, were consistent with a computational model of chromosomes based on tethered polymers and with the Rouse model from polymer physics, respectively. Furthermore, rapamycin-dependent transcriptional reprogramming of the genome only marginally affected the chromosome XII internal large-scale organization. Our comprehensive investigation of chromosome XII is thus in agreement with recent studies and models in which long-range architecture is largely determined by the physical principles of tethered polymers and volume exclusion.

Introduction

The genome of eukaryotes is organized in three dimensions according to principles that remain poorly understood even in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is among the simplest models to study the organization of the eukaryotic nucleus. The 16 chromosomes of a haploid yeast exhibit a nonrandom spatial distribution, and three structural elements, namely centromeres (CEN), telomeres (TEL), and the nucleolus (NUC), have been identified as key players of their organization (Taddei and Gasser, 2012). The CEN are clustered near the spindle-pole body (SPB) (Guacci et al., 1994, 1997; Jin et al., 1998, 2000). TEL are also clustered in foci at the nuclear envelope (NE; Klein et al., 1992; Gotta et al., 1996), so that chromosome arms extend outwards from CEN to the periphery, defining a Rabl-like conformation (Jin et al., 2000). Diametrically opposed to the SPB, the NUC physically separates from the rest of the genome the repetitive ribosomal DNA (rDNA) genes carried on chromosome XII in a crescent-shaped structure of about one third of the nuclear volume (Yang et al., 1989; Léger-Silvestre et al., 1999).

The conformation of yeast chromosomes was analyzed using chromosome capture conformation (3C) techniques (Dekker et al., 2002; Duan et al., 2010; Tanizawa et al., 2010), but without elucidating the mechanisms driving their folding (Langowski, 2010). Transcription may be involved in genome large-scale architecture, given that the spatial position of some genes is correlated with their expression level (for review see Taddei and Gasser, 2012). Actively transcribed genes could contact the NE through nuclear pore complex interactions (Casolari et al., 2004; Schmid et al., 2006), and these interactions are driven by transcription in some cases (e.g., GAL1-10 or INO1; Brickner and Walter, 2004; Casolari et al., 2004; Cabal et al., 2006). tRNA genes, which are scattered throughout the genome, appear to form foci at the nucleolar periphery (Thompson et al., 2003), as well as near the CEN (Duan et al., 2010), but these results still remain the subject of discussions (Cournac et al., 2012; Witten and Noble, 2012). In fact, it is still unclear whether and how the positioning of specific genes impacts the long-range organization of chromosomes.

In this report, we studied the conformation and the dynamics of yeast chromosomes using high-throughput live cell microscopy, and compared our results to a recent computational model. We focused on the largest yeast chromosome (XII) because it contains the three classes of genes: the rDNA locus transcribed by RNA Polymerase (Pol) I and Pol III (Petes, 1979), ∼600 protein coding genes transcribed by Pol II, and 22 noncoding RNA (ncRNA) genes transcribed by Pol III. The chromosome XII was fluorescently labeled every 100 kb to produce a comprehensive description of the position of one single yeast chromosome, showing a polymer-like conformation in agreement with the prediction of a computational model based on polymer physics and volume exclusion (Wong et al., 2012). Some RNA Pol III–transcribed genes along chromosome XII deviate slightly from this model, while the global organization is not affected. We also investigated the contribution of transcription to chromosome conformation by inducing a modulation of transcription by TOR inhibition. This analysis showed that such major transcription reprogramming had little effect on chromosome XII conformation. Our study of chromosome architecture was finally extended to the analysis of the motion of different loci, which matches the predictions of polymer models, thus suggesting that the folding principles of yeast chromosomes are mainly dictated by polymer physics.

Results and discussion

Long-range organization of chromosome XII between anchoring elements (TEL, CEN, and NUC)

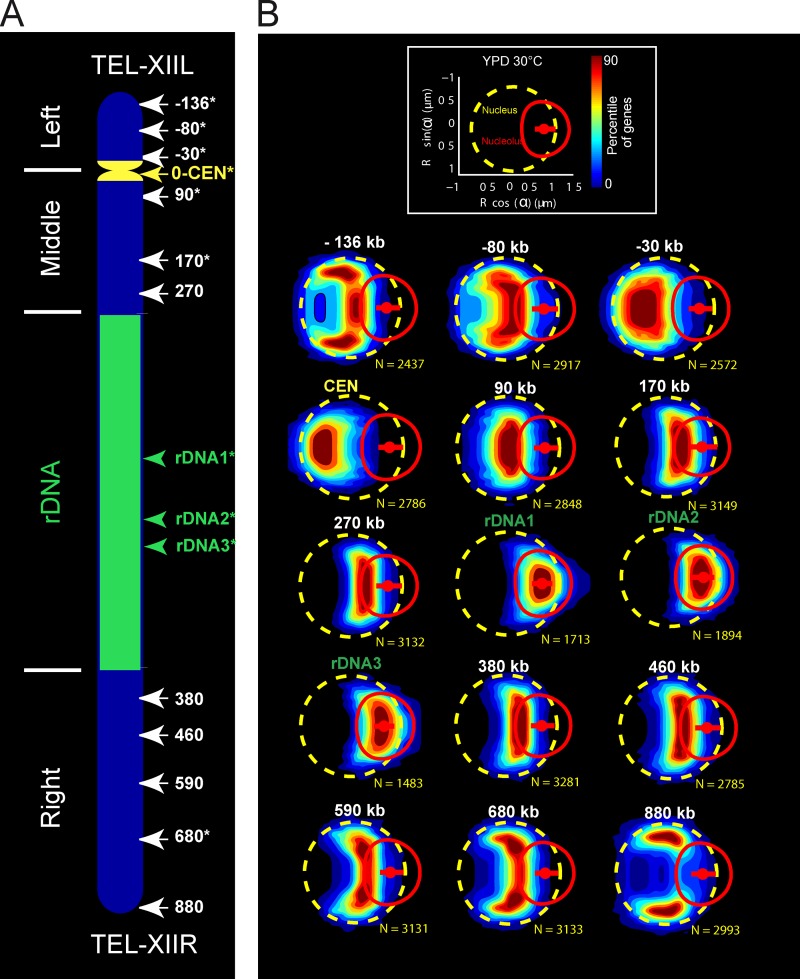

Global architecture of chromosome XII was first investigated in living yeast cells by monitoring the position of 15 loci distributed along the chromosome. Using targeted homologous recombination of fluorescent operator-repressor system (FROS), 12 independent insertions distributed every ∼100 kb were generated along the non-rDNA region of chromosome XII (Fig. 1 A). We also labeled three individual loci within the rDNA region at known distances from the CEN (Fig. 1; see Materials and methods).

Figure 1.

Color-coded statistical mapping of positions of 15 loci along chromosome XII. (A) Schematic representation of chromosome XII with the 15 FROS-labeled loci. Note that the rDNA of 1.8 Mb is depicted as a 1-Mb segment. Loci studied by particle tracking are marked with asterisks. (B) Spatial distributions of each locus are represented using gene maps, color-coded heat maps determined by the percentile of the distribution (Berger et al., 2008; Therizols et al., 2010). (top) The dashed yellow circle, the red circle, and the small red dot depict the median NE, the median NUC, and the median location of the nucleolar center, respectively. (bottom) The gene maps are represented with the genomic position indicated on top (N represents the number of nuclei analyzed). Note that the position along the genome of the three rDNA loci has been determined by I-SceI cleavage. The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats.

We chose to represent the position of a locus as a probability distribution relative to nuclear and nucleolar centers in living cells (Berger et al., 2008; Therizols et al., 2010). The spatial repartition of loci positions was assayed in a large number of cells in interphase (>1,500), and the data were represented in a color-coded statistical map of loci positions in which the percentage in an enclosing contour represents the probability of finding a locus inside (Fig. 1 B). The radius of the nuclei and their morphology, characterized by the distance between the nuclear and the nucleolar centers, were similar in all strains (see Fig. S1). We also selected FROS strains with comparable nuclear (3.4 ± 0.09 µm3) and nucleolar volumes (1.37 ± 0.08 µm3) so as to overlay the positions of loci in the same map (see Materials and methods and Video 1).

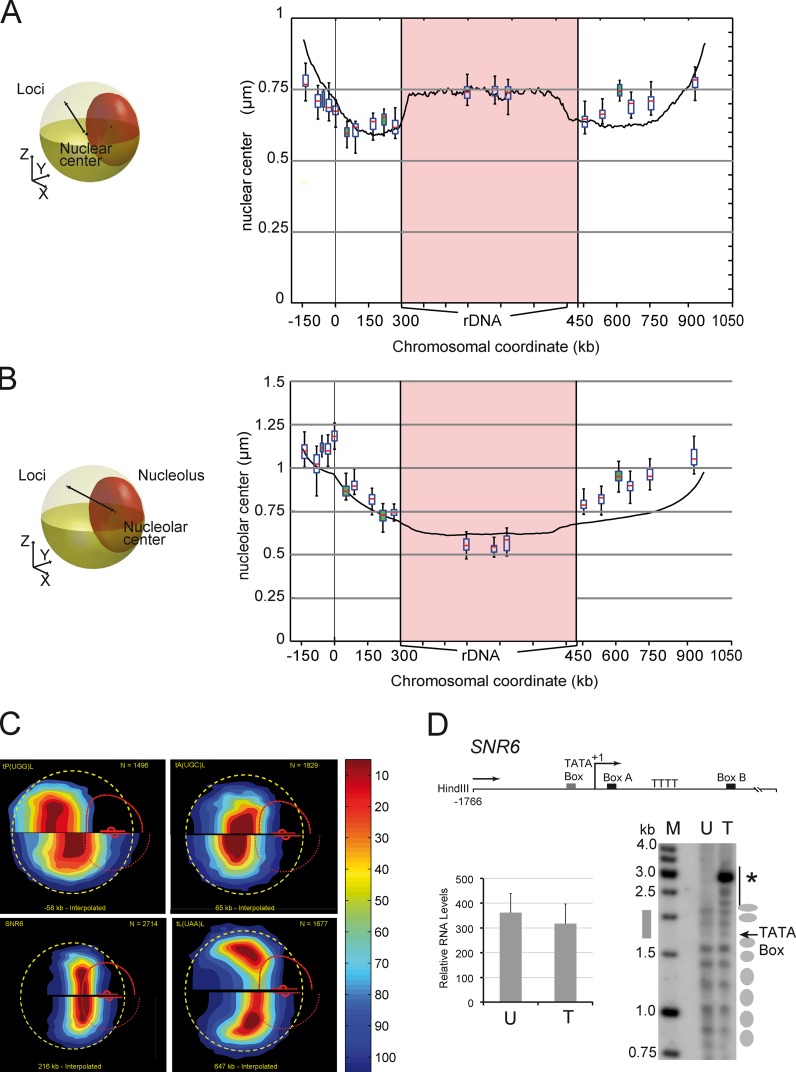

The visual inspection of statistical maps shows that the position of loci along chromosome XII is consistent with a path dictated by the genomic coordinates of each locus and the segmentation of the chromosomes between three structuring elements CEN, TEL, and NUC (Fig. 1 B and Video 1). We then wished to assess whether chromosome XII folding could be predicted by nuclear models based on polymer physics (Wong et al., 2012). The median distance to the nuclear and nucleolar centers was plotted as a function of the genomic coordinates of each locus (box plots in Fig. 2, A and B; see Materials and methods), and these data compared well with the model predictions (Wong et al., 2012; Fig. 2, A and B, black line). We noted that the fit to the model prediction was poorer for genomic positions 450–1,050 kb, i.e., from NUC to the right TEL (see, e.g., the anomalous dynamics of the rDNA in Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

The position of loci along chromosome XII relative to the NUC and the NE are predicted by computational modeling. (A and B) The distance of the locus to the nuclear center (A) and to the nucleolar center (B) is plotted versus its genomic position. Yellow and red ellipsoids depict the NE and NUC, respectively, and the black line represents the distance (left). The median distance is shown with box plots for the 15 loci described in Fig. 1 and for four RNA Pol III genes (white and green datasets). The median distance of chromosome XII loci to the nuclear center and to the centroid of the rDNA segment from a computational model of chromosome XII (Wong et al., 2012) is shown with solid black lines. (C) The gene map of loci t(P(UGG)L, tA(UGC)L, SNR6, and t(L(UAA)L relative to interpolated positions −58, 65, 216, and 647 kb (which correspond to their genomic coordinates) reveals global agreement between the model and measurements (see Video 2). The experimentally determined gene map (top) is compared with the interpolated position (bottom). The dashed yellow circle, the curved broken red line, and the small red dot depict the median NE, the median NUC, and the median location of the nucleolar center, respectively. (D) The yeast U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) gene SNR6 is unaffected by FROS insertion. Locations of important elements are indicated relative to the transcriptional start site (bent arrow) as +1 (top). Indirect end-labeling analysis of the chromatin structure on SNR6 is shown on the bottom-right panel. Ellipses on the right mark the positioned nucleosomes in the corresponding lanes with wild-type unmodified (U) or FROS tagged (T) strains. Note that the apparent hyper-sensitive site (asterisk) detected upon FROS insertion corresponds to a HindIII site introduced along with tetO repeat. SNR6 expression is not affected by FROS insertion. Transcript levels in untagged and FROS-tagged strains were normalized against the U4 transcript used as an internal control. The mean and scatter of RNA levels estimated from three independent experiments are plotted (error bars; bottom left).

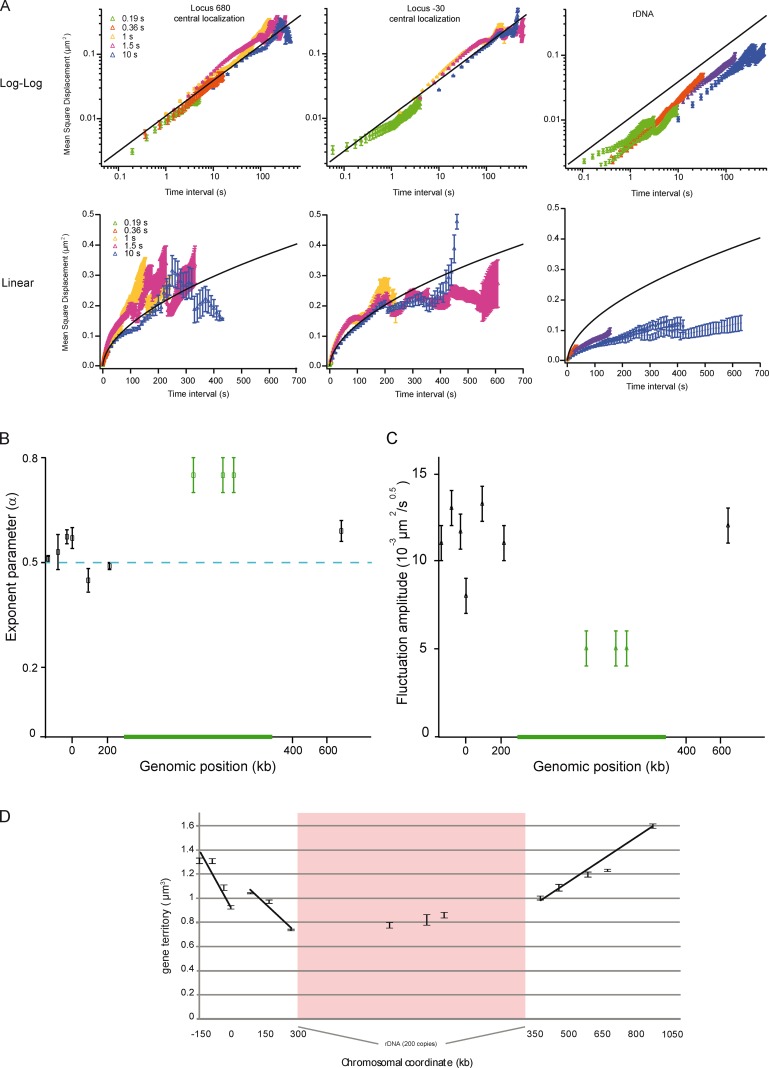

Figure 4.

Loci motion is slowed down at NUC, and homogeneous elsewhere. (A) The temporal evolution of the MSD is plotted at position 680 kb, −30 kb (for central localization), and at rDNA (nucleolar localization) in log-log (top) or linear (bottom) scale. MSD extracted from time lapse of 0.19-, 0.36-, 1-, 1.5-, and 10-s inter-frames are depicted in different colors. The curves are fitted with an anomalous diffusion model (solid lines), showing that the anomaly parameter is 0.5 ± 0.07. Note that the movements of rDNA are slow in comparison to those of the locus at 680 or −30 kb. The black line represents the fit to the dataset with a power-law scaling of 0.55. (B) The plot represents the anomaly parameter versus the genomic position, and shows the different dynamics in NUC for the 10 analyzed loci. (C) Spatial fluctuations of the 10 analyzed loci are compared by measuring the amplitude of the power-law scaling response using a model with Γt0.5. (D) The gene territory, defined by the volume occupied by 50% of the gene population (the green isocontour in gene maps) expressed in cubic micrometers is measured as a function of the genomic position. Gene territory experimental errors were determined by measuring gene territories from three samplings of the full dataset.

The smooth variations of the median positions between consecutive loci suggested that the statistical maps could be interpolated with a genomic resolution much finer than 100 kb. We thus computed statistical maps every kilobase along chromosome XII (Video 2; see Materials and methods), and we challenged their relevance by comparing them to the positions of four RNA Pol III–transcribed genes along chromosome XII (tP(UGG), tA(UGC), tL(UAA), and SNR6); their genomic positions correspond to the green box plots of Fig. 2 (A and B). Experimental and interpolated statistical maps are represented in the top and bottom half of Fig. 2 C, respectively. If SNR6 shows a good agreement with interpolation, mild or strong discrepancies are observed, respectively, for tA(UGC), tL(UAA), or tP(UGG). Such data argue for a local effect of Pol III genes on chromosome structure, and differ from colocalization assays, in which Pol III–transcribed genes were organized in clusters close to CEN or NUC (Thompson et al., 2003; Duan et al., 2010). We suggest that the distribution of genes is primarily influenced by their genomic position, and only locally by sequence-specific physical interactions (Fig. 2, A and B). Note that we checked that the FROS insertion did not affect chromatin structure by analyzing the inner structure of SNR6 using in situ indirect-end labeling (IEL; Fig. 2 D). Our results show that nucleosome positioning within the upstream and transcribed regions is similar in the control and the labeled strain (Fig. 2 D). Moreover, the transcription level of SNR6 was not significantly modified by FROS labeling (Fig. 2 D). In conclusion, experimental data and predictions from the computational model are largely compatible, which suggests that the folding of chromosome XII is mainly dictated by local attachments to the three main nuclear structures NUC, TEL, and CEN.

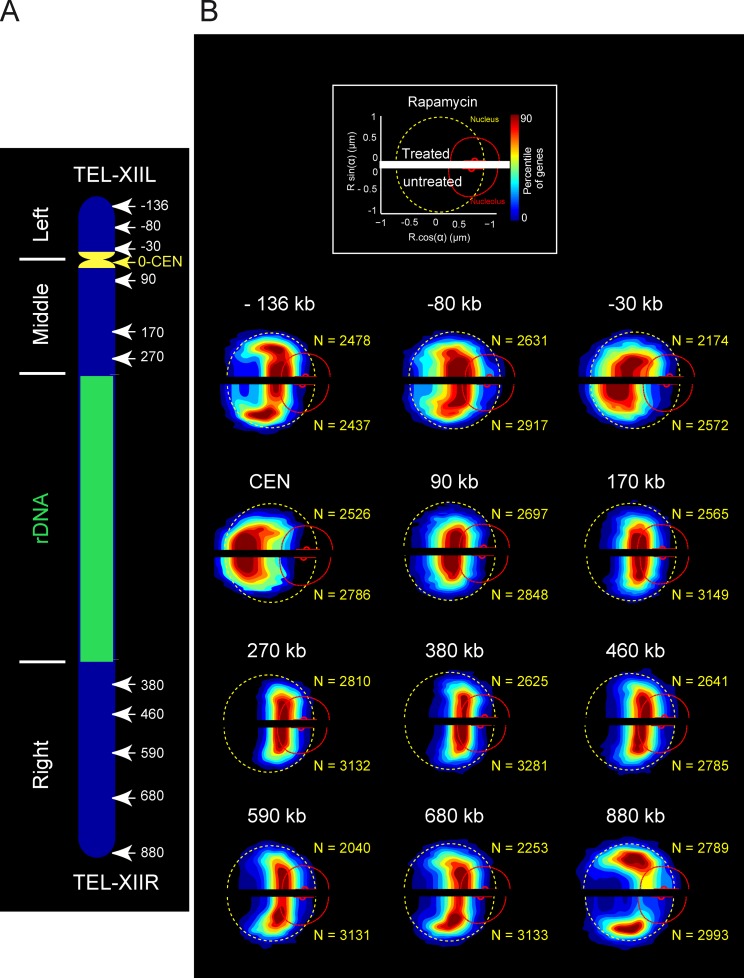

Major transcriptional reprogramming has little effect on chromosome XII structure

To investigate further whether molecular interactions driven by transcription played a role in global chromosome architecture, we probed the structure of chromosome XII by statistical mapping after a major transcriptional repression (Fig. 3). Cells were treated with rapamycin, an inhibitor of the conserved protein kinase complex TORC1 (target of rapamycin; Loewith et al., 2002), which induces a global modification of transcription, mimicking nutrient deprivation characterized by transcriptional repression of Pol II ribosomal protein genes, rRNA 5S genes transcribed by Pol III, and a repression of Pol I activity (Hardwick et al., 1999; Wullschleger et al., 2006). After 20 min of rapamycin treatment, the mean nucleolar volume decreased by 37%, but the nucleus remained nearly constant in size (4% increase in volume), in agreement with previous studies (Therizols et al., 2010). The statistical maps of 12 loci positions were determined in nontreated versus rapamycin-treated cells, and are represented, respectively, in the top half and bottom half of each gene map (Fig. 3). Nucleolar size reduction generated a global shift of all loci toward the NUC. However, we did not detect major modifications of internal chromosome folding at the population level, thus supporting our model in which chromosome architecture is mainly determined by the biophysical properties of chromosomes and volume exclusion rather than by molecular interactions mediated by transcription.

Figure 3.

Color-coded statistical mapping of positions of 12 loci along chromosome XII after rapamycin treatment. (A) Schematic representation of chromosome XII with the 12 FROS-labeled loci using the centromere as an origin. (B) The spatial distributions of each locus (bottom of the gene map representations) are compared with loci position in rapamycin-treated cells (top of the gene map representations). The dashed yellow circle, the curved broken red line, and the small red dot depict the median NE, the median NUC, and the median location of the nucleolar center, respectively.

Chromatin motion of chromosome XII

We investigated the dynamics of chromosome XII and compared these data to predictions of polymer models. The motion of 10 loci (Fig. 1 A, asterisks) was studied by recording their trajectories in 2D rather than in 3D to increase the acquisition speed and reduce phototoxicity. Normal cell growth was observed during up to 2 h of acquisition (Video 3). A broad temporal range (from 0.2 to 400 s) was probed using five distinct inter-frame intervals of 190 ms, 360 ms for all loci, and 1, 1.5, and 10 s for three loci. Dedicated software was developed to perform systematic trajectory analysis (Fig. S2, A–C; See Materials and methods). This software allowed us to extract the mean square displacement (MSD), which is the mean of the squared travel distances after a given time lag, for every locus, and to compare the dynamics in the case of central, peripheral, or nucleolar-localized loci (Fig. S2). Trajectories during which deformations of the nucleus or detection of drifts of the nuclear center occurred (e.g. during mitosis, see Video 3) were disregarded.

Several studies suggested that chromatin motion was determined by a normal diffusive behavior in a restrained volume (MSD∼t in the small time limit, and MSD∼a in the long time limit, with a being the radius of constraint; Marshall et al., 1997; Heun et al., 2001; Meister et al., 2010). To display MSD in the short and long time regimes, we used linear and logarithmic representations (Fig. 4 and Fig. S3). Loci −30, 680, and rDNA were chosen as representative examples (Fig. 4). We observed that MSD curves exhibited a power-law scaling response expressed as MSD∼Γ × tα, with an anomalous parameter α of ∼0.5 ± 0.07 (Fig. 4 B) and an amplitude of the motion Γ of ∼0.01 µm2 × s−0.5. Interestingly, the anomalous diffusive response is consistent with the Rouse polymer model that describes the movements of polymer segments based on their elastic interactions and on viscous frictions (De Gennes, 1979). This model is expected to apply to dense polymer solutions (De Gennes, 1979), and it was recently observed that the bacterial genome behaves as predicted from this model (Weber et al., 2010a,b). It also applies to the molecular dynamics simulations of the yeast genome (Rosa and Everaers, 2008), thus strengthening our view that chromosome properties in yeast fit with polymer models.

We further developed the description of chromatin dynamics at a short time interval along chromosome XII. We compared the amplitude of the MSD traces by plotting Γ for every locus (Fig. 4 C and Fig. S3), showing that the chromatin movements are homogeneous for most of the loci with a value in the range ∼0.010–0.015 µm2 × s−0.5. These results suggest a homogeneous behavior of chromatin throughout chromosome XII, except for rDNA. In addition, chromatin dynamics were not different for a locus with a central or peripheral localization (Fig. S3), and the amplitude of fluctuations Γ was moderately reduced by ∼20% for loci with nucleolar versus central localization (Fig. S3), which suggests that nucleolar proximity tends to restrain chromatin motion of non-rDNA loci. The investigation of MSD in the long time limit, best viewed in linear representation, revealed a deviation from the Rouse regimen MSD∼Γ × t0.5. As previously suggested (Meister et al., 2010), the apparent confinement in the MSD is related to loci diffusing in a restrained volume. Space visited after 200 s (∼0.15 µm2, ∼0.25 µm2, and ∼0.3 µm2 for the rDNA, locus −30 kb, and locus 680 kb, respectively), can be assigned to an explored volume of 0.57, 1.02, and 1.34 µm3 for the three loci (Meister et al., 2010). These values are in excellent agreement with the dimensions of gene territories, as defined by the volume in which 50% of the gene positions are detected in statistical maps (Fig. 4 D; rDNA, locus −30 kb, and locus 680 kb, respectively, at 0.8, 1.1, and 1.2 µm3). This analysis also shows that one locus can explore the entire statistical map within a few minutes.

Finally, the motility of three chromosomal loci in the rDNA was investigated (Fig. 4), showing an MSD with two distinct slopes: increasingly slowly for t < 5 s (α = ∼0.25) and more abruptly after 5 s (α = ∼0.7). These dynamics are not consistent with the Rouse model (Fig. 4 A, black lines). In these polymer models, several specific properties of the rDNA were disregarded, including among others the dynamics associated with transcriptional activity, the depletion of nucleosomes from actively transcribed rDNA (Conconi et al., 1989), or the possible local tethering of rDNA via CLIP proteins (Mekhail et al., 2008; Mekhail and Moazed, 2010). This problem should be considered in future molecular dynamics simulations.

To conclude, our systematic analysis of position and motion of loci along chromosome XII showed that its inner structure mainly consists of constrained chromosome arms anchored to nuclear elements (SPB, NUC, and NE), as expected from recent computational models (Tjong et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2012). We also demonstrated that the Rouse polymer model accurately describes the motion of chromatin loci except for the rDNA (Rosa and Everaers, 2008), the biophysical properties of which remain to be investigated.

We may finally speculate on whether the properties of chromosomes observed in yeast are relevant to metazoans. Our results suggest that chromosomes should be viewed as anchored polymers in a dense environment. Lamin associated domains (LADs) and nucleolar tethering domains (NADs), which appear to be distributed in large regions of the metazoan genome (Guelen et al., 2008; Németh et al., 2010; van Koningsbruggen et al., 2010), may provide anchoring regions analogous to NUC, CEN, and TEL. We believe that the relevance of the Rouse model between anchoring regions should be studied, and spatial references should be proposed to construct statistical maps to investigate chromosome folding properties.

Materials and methods

Plasmid and yeast strains construction

pUC19-URA-iSCEI was constructed by cloning a BamHI–EcoRI fragment of the cut PCR product generated using oligonucleotide 1,033–1,034 and S288c genomic DNA into pUC19 at the same sites. Genotypes of the strains used in this study are described in Table S1. Oligonucleotides used for PCR are described in Table S2. tetO insertion was performed along chromosome XII, every 10 kb in the noncoding region. Genomic tetO integrations in non-rDNA regions were performed in two steps, first by integrating the HIS3 or URA3 gene by homologous recombination at the indicated location along chromosome arms, and second by inserting in the inserted markers (HIS3 or URA3) tetO repeats. Homologous recombination of URA3 or HIS3 was performed by transforming the PCR product amplified with appropriate oligonucleotides on pCR4-HIS3-M13 (Berger et al., 2008) or pSK-URA3-M13 (Berger et al., 2008) into TMS1-1a. After confirmation of the insertion site by PCR on genomic DNA, auxotrophic markers (URA3 or HIS3) were used as targets for insertion of the EcoRI-linearized plasmids ptetO-NAT-his3Δ or ptetO-NAT-ura3Δ, respectively. ptetO-NAT-his3Δ or ptetO-NAT-ura3Δ bore an array of 256 tetO, a Nourseothricin resistance marker, and a yeast genome fragment, allowing the insertion of the linearized plasmid by homologous recombination in HIS3 or URA3, as described previously (Berger et al., 2008; Rohner et al., 2008). The proper targeting of the tetO site was confirmed by inactivation the auxotrophic markers, and by size determination of chromosome XII by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (CHEF-DR III; Bio-Rad Laboratories), followed by Southern blotting to confirm tetO insertion in the chromosome XII (Albert et al., 2011). Large chromosomal rearrangements, observed for some FROS-labeled strains, were discarded by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis. The number of rDNA repeats can change within a cell population, potentially introducing heterogeneity among the FROS-labeled clones (Pasero and Marilley, 1993), so we used PFGE to confirm that chromosome XII size was not altered in our labeled strains.

Mapping FROS insertions in rDNA

Genomic tetO integrations in the rDNA regions were performed in two steps, first by integrating the URA3 gene, bearing an adjacent I-SceI site, by homologous recombination in one of the rDNA repeats, and second by inserting tetO repeats in the inserted URA3 marker. The PCR product amplified with oligonucleotides 1,035 and 1,036 on pUC19-URA-iSCEI was transformed into TMS1-1a. To map rDNA insertion, I-SceI genomic position was determined using pulse-field gel electrophoresis, followed by Southern blotting to map tetO insertion. After I-SceI cleavage, FROS-labeled chromosome XII is separated into a fragment containing left telomere and centromere and a region containing right telomere, revealed by EtBr staining. Southern blotting using tetO as a probe identified the right arm of the cleaved chromosome XII. We estimated insertion within the rDNA at 750, 1,060, and 1,170 kb from the centromere-proximal edge of rDNA in clones rDNA-1, -2, and -3, respectively. Note that migration of a repeated genomic region, such as rDNA, is not strictly proportional to DNA size and that the insertion site was extrapolated considering 1.8 Mb of rDNA (∼200 repeats).

Chromatin structure using IEL and transcript quantification

Chromatin structure analysis by the IEL method and RNA extraction and quantification were performed as described previously (Arimbasseri and Bhargava, 2008), and repeated at least three times for each experiment. In brief, for IEL analysis, yeast cells were spheroplasted and subjected to partial digestion with micrococcal nuclease. DNA was extracted, digested with HindIII, resolved on 1.5% agarose gel, and Southern transferred. The probe for hybridization was amplified using oligonucleotides described in Table S2 and α-[32P]ATP in a PCR reaction. A 1-kb radiolabeled DNA ladder was run on the same gel as the size marker. Primer extension on RNA extracted from FROS-tagged and untagged strains to get cDNA preparation was done by using radio-labeled primers. Products were resolved on 8 M urea–10% polyacrylamide gel, bands were visualized by phosphorimaging, and SNR6 transcript was quantified by using Image gauge (Fuji) software as described previously (Shivaswamy et al., 2004; Arimbasseri and Bhargava, 2008).

Fluorescence microscopy of living yeast cells

Yeast media were used as described previously (Rose et al., 1990). YPD is made of 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose. SC medium is made of 0.67% nitrogen base without amino acids (BD), 2% dextrose supplemented with amino acids mixture (AA mixture; Bio101), adenine, and uracil. Cells were grown overnight at 30°C in YPD. Cells were diluted at 106 cells/ml, and were harvested when OD600 reached 4 × 106 cells/ml and rinsed twice with the corresponding SC media. Cells were spread on slides coated with an SC media patch containing 2% agarose and 2% glucose. Cover slides were sealed with “VaLaP” (1/3 vaseline, 1/3 lanoline, and 1/3 paraffin). For long time-lapse acquisition and confocal imaging, the imaging chamber was maintained at 30°C.

Microscope image acquisition

Confocal microscopy was limited to 20 min after mounting and performed with a disk confocal system (Revolution Nipkow; Andor Technology) installed on an inverted microscope (IX-81; Olympus) featuring a CSU22 confocal spinning disk unit (Yokogawa Corporation of America) and an EM charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (DU 888; Andor Technology). The system was controlled using the mode “Revolution FAST” of Andor Revolution IQ1 software (Andor Technology). Images were acquired using a 100× objective lens (Plan-Apochromat, 1.4 NA, oil immersion; Olympus). Single laser lines used for excitation were diode pumped solid state lasers (DPSSL) exciting GFP fluorescence at 488 nm (50 mW; Coherent) and mCherry fluorescence at 561 nm (50 mW; Cobolt jive). A bi-bandpass emission filter (Em01-R488/568-15; Semrock) allowed collection of green and red fluorescence. Pixel size was 65 nm. For 3D analysis, z stacks of 41 images with a 250-nm z step were used. Exposure time was 200 ms.

MSD analysis was performed by recording the movements of chromosome loci by epifluorescence on two different microscope settings, depending on the inter-frame interval. For long time intervals (1.5 s, 4 s, and 10 s), image acquisition was performed on an inverted microscope (Ti-E/B; Nikon) equipped with a Perfect Focus System (PFS), suitable for long-range time-lapse experiments. The system was equipped with a 100× oil immersion objective lens (CFI Plan-fluor 100×, ON 1.30, Dt0.2), HG Intensilight illumination (Nikon) with low power (NDFilter = 6.3 for GFP; 3.0 for mCherry), filter cubes TE/ZP FITC (FITC-3540C; Semrock) for GFP signal, and TE/ZP Texas red (TxRed-4040C; Semrock) for mCherry imaging, as well as a 1.5× lens and an EM CCD camera (DU-897; EM gain 555 GFP; 40 for mCherry; Andor Technology). Measured pixel size was 106.7 nm. Acquisition was set to 300 ms or 600 ms, respectively, for GFP and mCherry. For short time intervals (50 and 200 ms), imaging was performed using an upright microscope (BX-51; Olympus) equipped with a laser diode light source (Lumencor), a 100× oil immersion objective lens (NA 1.4), and an EM CCD camera (DU-897), as described in Hajjoul et al. (2009). The GFP excitation emission at 470 ± 10 nm was set to 7.53 W/µm2.

For short time intervals (50 and 200 ms), time-lapse sequences consisted of 300 consecutive images, and we displayed MSD traces on 150 time intervals to ensure the statistical relevance of mean displacements. mCherry signal was recorded at the end of GFP acquisition. For longer time intervals (1.5 s, 4 s, and 10 s inter-frame), time-lapse images were acquired, respectively, for 5, 15, and 120 min, and manually checked to discard drifting cells. For GFP exposure with an inter-frame of 10 s, mCherry and brightfield acquisition was performed every 100 s (each 10 GFP frames) to limit phototoxicity.

Image processing for time-lapse movies

Video 3 was generated by NIS image (Nikon), and was imported into Final Cut Pro X (Apple). Color enhancement and dust attenuation were obtained by background correction. The timeline and scale bar were inserted into the movie file using Flash CS5 Professional (Adobe).

Image analysis for locus position

Confocal images were processed and analyzed with a MATLAB script nucloc, available at http://www.nucloc.org/ (MathWorks; Berger et al., 2008). The box plots of nuclear radius and nuclear–nucleolar center distances were generated using the boxplot function in MATLAB (MathWorks). The box plot of median distances from nuclear center to nucleolar center were computed in two steps, first MATLAB calculating the median distances for each 100 nuclei, and then by plotting the box plot of the median values obtained.

Image analysis for gene trajectory

Automatic particle tracking and spatial registration in time-lapse analysis was then performed with our custom-made software run in MATLAB (Supplemental data). Single particle-tracking software built on the MTT platform (Sergé et al., 2008) was developed to perform high-throughput 2D trajectory analysis over a large temporal range. For trajectory analysis, we first evaluated the variations of the positioning error with the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) to compensate for biases associated to the difference in brightness between the different strains (Fig. S2). Objects of controlled brightness and position were generated in silico, and tracked with our algorithm to retrieve the detection error, which was in the range of 5 × 10−4 to 5 × 10−5 µm2. Because of the very high accuracy of gene position determination, correcting nuclear motion from gene trajectory added noise to observed motion. Rather than a systematic correction for nuclear center, we then manually excluded gene trajectories with detectable motion of nuclear position, leading to exclusion of <10% of trajectories for short time lapse, and 30–50% of trajectories for long time lapse. Gene movements were recorded at fast or slow acquisition rates, resulting in different SNR, hence in different tracking error SNR. Starting from raw data, we compensated for the difference in SNR by adding an error to the slow acquisition MSD dataset, which is determined by the difference in tracking precision. Datasets are then fused and filtered using a Gaussian filter (order 11; see Fig. S2). The resulting dataset is adjusted with an anomalous diffusion model. MSD curves were ultimately extracted and analyzed using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 depicts the nuclear morphology of the 31 analyzed populations. Fig. S2 shows methods used for tracking genes in living cells. Fig. S3 shows MSD responses for loci −136 kb, −80 kb, CEN, 90 kb, and 170 kb along chromosome XII. Table S1 shows genotypes of the strains used in this study. Table S2 lists oligonucleotides used in this study. Table S3 lists the plasmids used in this study. Video 1 shows overlaid color-coded statistical mapping of loci positions. Video 2 shows interpolation between color-coded statistical mapping of loci positions. Video 3 shows a time-lapse series of the 90-kb locus labeled strain. Codes (MATLAB scripts) of custom-made software tracking loci are available as a ZIP file. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201208186/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mathieu Stouf, Héléne Badouin, Juliane Klehr, and Céline Jeziorski for strain construction and initial characterization of loci positions. This work also benefited from the assistance of the imaging platform from Toulouse TRI.

This work was supported by an ATIP-plus grant from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Nucleopol, Ribeuc, and program JCJC), Jeune équipe from FRM, and University Paul Sabatier (a fellowship for J. Mathon). This work is a French-Indian collaborative effort funded by Indo-French Centre for the Promotion of Advanced Research (IFCPAR) Project 4103 between the laboratories of Dr. Bhargava and Dr. Gadal.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- CEN

- centromeres

- FROS

- fluorescent operator-repressor system

- IEL

- indirect-end labeling

- MSD

- mean square displacement

- NE

- nuclear envelope

- NUC

- nucleolus

- Pol

- Polymerase

- rDNA

- ribosomal DNA

- SNR

- signal-to-noise ratio

- SPB

- spindle-pole body

- TEL

- telomeres

References

- Albert B., Léger-Silvestre I., Normand C., Ostermaier M.K., Pérez-Fernández J., Panov K.I., Zomerdijk J.C., Schultz P., Gadal O. 2011. RNA polymerase I-specific subunits promote polymerase clustering to enhance the rRNA gene transcription cycle. J. Cell Biol. 192:277–293 10.1083/jcb.201006040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimbasseri A.G., Bhargava P. 2008. Chromatin structure and expression of a gene transcribed by RNA polymerase III are independent of H2A.Z deposition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:2598–2607 10.1128/MCB.01953-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A.B., Cabal G.G., Fabre E., Duong T., Buc H., Nehrbass U., Olivo-Marin J.C., Gadal O., Zimmer C. 2008. High-resolution statistical mapping reveals gene territories in live yeast. Nat. Methods. 5:1031–1037 10.1038/nmeth.1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner J.H., Walter P. 2004. Gene recruitment of the activated INO1 locus to the nuclear membrane. PLoS Biol. 2:e342 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabal G.G., Genovesio A., Rodriguez-Navarro S., Zimmer C., Gadal O., Lesne A., Buc H., Feuerbach-Fournier F., Olivo-Marin J.C., Hurt E.C., Nehrbass U. 2006. SAGA interacting factors confine sub-diffusion of transcribed genes to the nuclear envelope. Nature. 441:770–773 10.1038/nature04752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolari J.M., Brown C.R., Komili S., West J., Hieronymus H., Silver P.A. 2004. Genome-wide localization of the nuclear transport machinery couples transcriptional status and nuclear organization. Cell. 117:427–439 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00448-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conconi A., Widmer R.M., Koller T., Sogo J.M. 1989. Two different chromatin structures coexist in ribosomal RNA genes throughout the cell cycle. Cell. 57:753–761 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90790-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournac A., Marie-Nelly H., Marbouty M., Koszul R., Mozziconacci J. 2012. Normalization of a chromosomal contact map. BMC Genomics. 13:436 10.1186/1471-2164-13-436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gennes P.G. 1979. Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics. Cornell University Press; Ithica, NY: 324 pp [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J., Rippe K., Dekker M., Kleckner N. 2002. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 295:1306–1311 10.1126/science.1067799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z., Andronescu M., Schutz K., McIlwain S., Kim Y.J., Lee C., Shendure J., Fields S., Blau C.A., Noble W.S. 2010. A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature. 465:363–367 10.1038/nature08973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M., Laroche T., Formenton A., Maillet L., Scherthan H., Gasser S.M. 1996. The clustering of telomeres and colocalization with Rap1, Sir3, and Sir4 proteins in wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 134:1349–1363 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V., Hogan E., Koshland D. 1994. Chromosome condensation and sister chromatid pairing in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 125:517–530 10.1083/jcb.125.3.517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V., Hogan E., Koshland D. 1997. Centromere position in budding yeast: evidence for anaphase A. Mol. Biol. Cell. 8:957–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelen L., Pagie L., Brasset E., Meuleman W., Faza M.B., Talhout W., Eussen B.H., de Klein A., Wessels L., de Laat W., van Steensel B. 2008. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 453:948–951 10.1038/nature06947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjoul H., Kocanova S., Lassadi I., Bystricky K., Bancaud A. 2009. Lab-on-Chip for fast 3D particle tracking in living cells. Lab Chip. 9:3054–3058 10.1039/b909016a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick J.S., Kuruvilla F.G., Tong J.K., Shamji A.F., Schreiber S.L. 1999. Rapamycin-modulated transcription defines the subset of nutrient-sensitive signaling pathways directly controlled by the Tor proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:14866–14870 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun P., Laroche T., Shimada K., Furrer P., Gasser S.M. 2001. Chromosome dynamics in the yeast interphase nucleus. Science. 294:2181–2186 10.1126/science.1065366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q., Trelles-Sticken E., Scherthan H., Loidl J. 1998. Yeast nuclei display prominent centromere clustering that is reduced in nondividing cells and in meiotic prophase. J. Cell Biol. 141:21–29 10.1083/jcb.141.1.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q.W., Fuchs J., Loidl J. 2000. Centromere clustering is a major determinant of yeast interphase nuclear organization. J. Cell Sci. 113:1903–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein F., Laroche T., Cardenas M.E., Hofmann J.F., Schweizer D., Gasser S.M. 1992. Localization of RAP1 and topoisomerase II in nuclei and meiotic chromosomes of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 117:935–948 10.1083/jcb.117.5.935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langowski J. 2010. Chromosome conformation by crosslinking: polymer physics matters. Nucleus. 1:37–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léger-Silvestre I., Trumtel S., Noaillac-Depeyre J., Gas N. 1999. Functional compartmentalization of the nucleus in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Chromosoma. 108:103–113 10.1007/s004120050357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R., Jacinto E., Wullschleger S., Lorberg A., Crespo J.L., Bonenfant D., Oppliger W., Jenoe P., Hall M.N. 2002. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol. Cell. 10:457–468 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00636-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W.F., Straight A., Marko J.F., Swedlow J., Dernburg A., Belmont A., Murray A.W., Agard D.A., Sedat J.W. 1997. Interphase chromosomes undergo constrained diffusional motion in living cells. Curr. Biol. 7:930–939 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00412-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister P., Gehlen L.R., Varela E., Kalck V., Gasser S.M. 2010. Visualizing yeast chromosomes and nuclear architecture. Methods Enzymol. 470:535–567 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail K., Moazed D. 2010. The nuclear envelope in genome organization, expression and stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:317–328 10.1038/nrm2894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail K., Seebacher J., Gygi S.P., Moazed D. 2008. Role for perinuclear chromosome tethering in maintenance of genome stability. Nature. 456:667–670 10.1038/nature07460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Németh A., Conesa A., Santoyo-Lopez J., Medina I., Montaner D., Péterfia B., Solovei I., Cremer T., Dopazo J., Längst G. 2010. Initial genomics of the human nucleolus. PLoS Genet. 6:e1000889 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasero P., Marilley M. 1993. Size variation of rDNA clusters in the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Gen. Genet. 236:448–452 10.1007/BF00277147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petes T.D. 1979. Yeast ribosomal DNA genes are located on chromosome XII. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 76:410–414 10.1073/pnas.76.1.410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner S., Gasser S.M., Meister P. 2008. Modules for cloning-free chromatin tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisae. Yeast. 25:235–239 10.1002/yea.1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A., Everaers R. 2008. Structure and dynamics of interphase chromosomes. PLOS Comput. Biol. 4:e1000153 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M.D., Winston F., Hieter P. 1990. Methods in Yeast Genetics. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 180 pp [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Arib G., Laemmli C., Nishikawa J., Durussel T., Laemmli U.K. 2006. Nup-PI: the nucleopore-promoter interaction of genes in yeast. Mol. Cell. 21:379–391 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergé A., Bertaux N., Rigneault H., Marguet D. 2008. Dynamic multiple-target tracing to probe spatiotemporal cartography of cell membranes. Nat. Methods. 5:687–694 10.1038/nmeth.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivaswamy S., Kassavetis G.A., Bhargava P. 2004. High-level activation of transcription of the yeast U6 snRNA gene in chromatin by the basal RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:3596–3606 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3596-3606.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A., Gasser S.M. 2012. Structure and function in the budding yeast nucleus. Genetics. 192:107–129 10.1534/genetics.112.140608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanizawa H., Iwasaki O., Tanaka A., Capizzi J.R., Wickramasinghe P., Lee M., Fu Z., Noma K. 2010. Mapping of long-range associations throughout the fission yeast genome reveals global genome organization linked to transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:8164–8177 10.1093/nar/gkq955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therizols P., Duong T., Dujon B., Zimmer C., Fabre E. 2010. Chromosome arm length and nuclear constraints determine the dynamic relationship of yeast subtelomeres. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:2025–2030 10.1073/pnas.0914187107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M., Haeusler R.A., Good P.D., Engelke D.R. 2003. Nucleolar clustering of dispersed tRNA genes. Science. 302:1399–1401 10.1126/science.1089814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjong H., Gong K., Chen L., Alber F. 2012. Physical tethering and volume exclusion determine higher-order genome organization in budding yeast. Genome Res. 22:1295–1305 10.1101/gr.129437.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Koningsbruggen S., Gierlinski M., Schofield P., Martin D., Barton G.J., Ariyurek Y., den Dunnen J.T., Lamond A.I. 2010. High-resolution whole-genome sequencing reveals that specific chromatin domains from most human chromosomes associate with nucleoli. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:3735–3748 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S.C., Spakowitz A.J., Theriot J.A. 2010a. Bacterial chromosomal loci move subdiffusively through a viscoelastic cytoplasm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104:238102 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.238102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S.C., Theriot J.A., Spakowitz A.J. 2010b. Subdiffusive motion of a polymer composed of subdiffusive monomers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 82:011913 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.011913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten D.M., Noble W.S. 2012. On the assessment of statistical significance of three-dimensional colocalization of sets of genomic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:3849–3855 10.1093/nar/gks012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H., Marie-Nelly H., Herbert S., Carrivain P., Blanc H., Koszul R., Fabre E., Zimmer C. 2012. A predictive computational model of the dynamic 3D interphase yeast nucleus. Curr. Biol. 22:1881–1890 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M.N. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 124:471–484 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.H., Lambie E.J., Hardin J., Craft J., Snyder M. 1989. Higher order structure is present in the yeast nucleus: autoantibody probes demonstrate that the nucleolus lies opposite the spindle pole body. Chromosoma. 98:123–128 10.1007/BF00291048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.