Abstract

Griffithsin (Grft) is a protein lectin derived from red algae that tightly binds the HIV envelope protein gp120 and effectively inhibits virus infection. This inhibition is due to the binding by Grft of high-mannose saccharides on the surface of gp120. Grft has been shown to be a tight dimer, but the role of the dimer in Grft's anti-HIV function has not been fully explored. To investigate the role of the Grft dimer in anti-HIV function, an obligate dimer of Grft was designed by expressing the protein with a peptide linker between the two subunits. This “Grft-linker-Grft” is a folded protein dimer, apparently nearly identical in structural properties to the wild-type protein. A “one-armed” obligate dimer was also designed (Grft-linker-Grft OneArm), with each of the three carbohydrate binding sites of one subunit mutated while the other subunit remained intact. While both constructed dimers retained the ability to bind gp120 and the viral surface, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm was 84- to 1,010-fold less able to inhibit HIV than wild-type Grft, while Grft-linker-Grft had near-wild-type antiviral potency. Furthermore, while the wild-type protein demonstrated the ability to alter the structure of gp120 by exposing the CD4 binding site, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm largely lost this ability. In experiments to investigate gp120 shedding, it was found that Grft has different effects on gp120 shedding for strains from subtype B and subtype C, and this might correlate with Grft function. Evidence is provided that the dimer form of Grft is critical to the function of this protein in HIV inhibition.

INTRODUCTION

HIV is a devastating disease affecting at least 33 million people worldwide, leading to a critical need for multiple strategies to prevent HIV infection. One such strategy is the development of a microbicide to prevent the sexual spread of HIV. While the CAPRISA 004 clinical trial showed partial success for the HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitor tenofovir in gel form, the subsequent VOICE trials were not successful, likely due in part to noncompliance (1, 2). This underscores the need for a continued study of a variety of different microbicides, and the likelihood that most success will occur with combinations of drugs with different mechanisms of action (and possibly different formulations) to achieve maximal effectiveness and to avoid potential development of drug resistance (3).

Several highly effective proteins are being studied as possible microbicides, particularly lectins that bind the glycosylated surface of gp120. Many reports confirm the importance of lectins in binding gp120 and inhibiting HIV (4–10), and it has also been shown that viral escape by deglycosylation leads to a higher viral susceptibility to plasma antibodies (11). Griffithsin (Grft), a 121-amino-acid lectin derived from red alga Griffithsia spp. (7), is among the most promising lectins yet discovered. This protein has a combination of (i) higher potency than other lectins (7, 12), (ii) excellent preclinical properties, including low/no toxicity and lack of significant activation of a variety of cell types (13, 14), (iii) inexpensive production in gram quantities (15), and (iv) synergy when combined with antibodies and a variety of other lectins (16). Recently, Grft has also been shown to be active against other viruses, including the hepatitis C virus (17–20), and it is resistant to digestion by many commercially available proteases (although it is susceptible to elastase) (21). Recent work specifically addressing lectin cellular toxicity showed that Grft does not activate T cells, minimally alters gene expression, and minimally induces cytokine secretion (14). Further, while Grft can bind some human cells, it still retains antiviral activity (14). These positive characteristics make Grft a very promising microbicide candidate and underscore the importance of elucidating the biochemical details of the role of Grft in HIV inhibition (14, 22). There is a critical gap, however, in an understanding of how Grft functions so effectively to inhibit HIV infection. Crystal structures of Grft showing a dimer (10, 23, 24) and lower antiviral potential of a monomeric variant (8) have been reported. More recently, analytical ultracentrifugation confirmed a tight Grft dimer (25). However, the mechanism of action of Grft is not fully known. In particular, no work has yet investigated the Grft dimer itself or shown how it might function to achieve such unusually high potency.

Figure 1A shows the structure of Grft as determined by X-ray crystallography (23). The protein is a dimer, having three putative carbohydrate-binding sites (CBS) per subunit. Competition data and further structural work (7, 10) indicate that each binding site binds one mannose monosaccharide, making it very likely that Grft inhibits viral entry by binding mannose on the surface of gp120. Grft has been shown to also bind gp41 (7), although it has not been proven yet whether this binding is through N-glycan interaction and/or direct protein interaction. However, the gp41 glycoprotein is obscured during the first part of HIV entry, and mutations that affect Grft sensitivity tend to occur on gp120, not gp41 (12). The HIV envelope protein gp120 contains between 18 and 33 N-linked glycosylation sites (depending on the virus strain), approximately a dozen of which are high-mannose sites (26–29). These high-mannose saccharides contain several related branched glycans, often having three terminal mannose residues rarely found on mammalian cells (reducing the possibility of mannose-specific lectin-host interaction), although it has been shown that Grft can bind to peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) but retains antiviral activity (14, 22). Other work has demonstrated that several high-mannose glycans on the subtype C gp120 surface, in particular those on N234 and N295, have important roles in Grft effectiveness. HIV strains lacking both of these glycan sites on gp120 show significantly lower sensitivity to Grft, and introducing these two glycans by adding back the glycosylation sites at these locations on gp120 increased Grft sensitivity (12). Similarly, glycosylation at site N448 is likely important for Grft function (30). Interestingly, Grft has been shown to alter the conformation of gp120 by exposing the CD4 binding site on gp120 in both HIV-1 subtype B and C strains (31). This raises the possibility that the importance of some N-glycan sites on gp120 for Grft potency is related to the ability of Grft to utilize these sites to alter the conformation of gp120, thereby interfering with virus entry.

Fig 1.

(A) The structure of griffithsin as determined by X-ray crystallography (23). Blue and red ribbons represent subunits of the Grft dimer, and green sticks represent mannose. The structure was made with the program Chimera (95) using Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure 2gud (23). (B) The 15N HSQC spectrum of the obligate dimer Grft-linker-Grft (red) overlaid with the spectrum of wild-type Grft (black). The obligate dimer shows a spectrum essentially identical to that of wild-type Grft. (C and D) Analytical ultracentrifugation of Grft-linker-Grft. (C) van Holde-Weischet G(s) sedimentation coefficient distributions of Grft-linker-Grft at 3 concentrations (OD230 of 0.3, red; OD230 of 0.6, blue; OD230 of 0.9, green). Vertical distributions indicate homogeneity. (D) Genetic algorithm Monte Carlo analysis. Shown is a combined overlay of all samples using the same color scheme as in panel C. The density of color is proportional to the partial concentration. A small amount of a contaminating species is apparent in the lower s-value range in panels C and D. The major species from all concentrations appear to have a low anisotropy, consistent with the globular shape proposed by the X-ray structure, with frictional ratios in the range of 1.1 to 1.3; this agrees very well with the linked Grft dimer molecular weight. (E) Cartoon showing color-coded Grft domains, with domain A in red and domain B in blue. Three gray crosses indicate that the 3 carbohydrate binding sites were replaced to eliminate the carbohydrate binding ability of that domain.

Two outstanding questions regarding the mechanism of HIV inhibition by Grft have been (i) what roles do each of the three putative carbohydrate-binding sites play in the affinity of the protein for its mannose target and subsequent anti-HIV activity and (ii) what is the role of the dimer in Grft's anti-HIV activity? We have recently shown that, while loss of an individual carbohydrate binding site by substitution leads to only a severalfold loss of ability to bind gp120, such individual-site variants show losses of HIV inhibitory potency of orders of magnitude (25). Therefore, there is a clear lack of correlation between simple ability to bind gp120 and the ability of Grft to inhibit the virus.

Since there appears to be a lack of direct correlation between carbohydrate binding and anti-HIV activity, the question arises as to what structural features and interactions contribute to the effectiveness of Grft. This leads to a second question: whether the role of the dimer is critical for efficient Grft function. For the lectin cyanovirin-N (CV-N), anti-HIV activity could be restored with only slightly reduced activity when two nonfunctional CV-N units (each containing only one carbohydrate binding site) were cross-linked (32). Similarly, linking higher-order multimers of cyanovirin could increase its anti-HIV activity (33).

To address the role of the dimer in Grft function, we have made an obligate dimer of Grft as well as an obligate dimer with all three CBS in one subunit intact but the three CBS on the second subunit (“arm”) removed by substitution. In a direct comparison of the “two-armed” dimer and the “one-armed” dimer, we show that, while the obligate dimer behaves very similarly in all respects to the wild-type protein, the one-armed obligate dimer has quite different properties. The one-armed obligate dimer exhibits only a modest loss of ability to bind gp120, yet its ability to inhibit the virus is reduced by orders of magnitude compared to the wild-type protein and the obligate dimer. Further, both the wild-type Grft and the obligate dimer demonstrate the ability to alter the conformation of gp120, while the one-armed obligate dimer is markedly reduced in this ability. Overall, this work provides evidence that the mechanism of Grft involves multiple subunits binding to gp120 and suggests that the need for two subunits may be related to the ability of Grft to alter the conformation of gp120, reducing the potential of gp120 to mediate viral infection. This mechanism may be applicable to other multisubunit lectin inhibitors of HIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA construction.

Genes of Grft variants were cloned into the pET-15b expression vector (Novagen). Grft-linker-Grft was constructed using a 16-amino-acid Gly-Ser linker: SSSGGGGSGGGSSSGS. One-armed obligate dimer constructs were made similarly, and all variants were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Protein purification.

Plasmids with a coding sequence for an N-terminal histidine tag were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) competent cells and expressed in minimal media with 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source. Each variant was produced using the following procedure. Protein production was induced upon addition of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) with further incubation at 37°C for 6 h. Cells were harvested at 6,000 × g for 10 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 M guanidine hydrochloride, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM benzamidine, and 20 mM Tris (pH 8); this allowed complete solubilization of proteins from both the inclusion body and the supernatant upon cell disruption. The solution was French pressed twice at 16,000 lb/in2 and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 h. The soluble portion was loaded onto a nickel chelating column (Qiagen) equilibrated with the same resuspension buffer. Proteins were eluted using 500 mM imidazole, 5 M guanidine hydrochloride, 500 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris (pH 8) and refolded by dropwise addition to low-salt refolding buffer (50 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 8) over the course of 30 min. The solution was dialyzed in the same refolding buffer at 4°C overnight. The protein solution was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 h to remove precipitated material and purified on a C4 reversed-phase chromatography column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA). The fractions were analyzed on an SDS-PAGE gel to confirm the size and then lyophilized in a Labconco freeze-dry system.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Grft variants were expressed in minimal media with 15NH4Cl as the only nitrogen source. These variants were produced and purified as described above. To dissolve the protein powder after purification, 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with 5% D2O was used, and 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) was added for calibration. Spectra were collected at 25°C on a four-channel 600-MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer. The data were processed using NMRPipe (34) and analyzed using PIPP (35). For two-dimensional heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra, sweep widths of 9,615 Hz (1H) and 1,939 Hz (15N), with 640* points in 1H and 128* points in 15N, were used.

Analytical ultracentrifugation.

To identify the oligomerization state of the Grft-linker-Grft construct, the molecule was studied by analytical ultracentrifugation using sedimentation velocity (SV) analysis. To determine if mass action effects could affect the oligomerization state, the experiments were carried out at multiple concentrations. Enhanced van Holde-Weischet analysis (36) resulted in vertical integral sedimentation coefficient distribution, identifying a major species with identical sedimentation coefficients for each concentration, suggesting that the major species is homogeneous and not subject to mass action-induced oligomerization (Fig. 1C). To determine the molecular mass of this major species and ultimately identify the oligomerization state of Grft-linker-Grft, two-dimensional spectrum analysis (37, 38) and genetic algorithm analysis (39, 40), combined with Monte Carlo analysis (41) were used; the resulting molecular masses were consistent only with the dimer (24.4 kDa for the species with optical density at 230 nm [OD230] of 0.3, 27.8 kDa for the species with OD230 of 0.6, and 26.6 kDa for the species with OD230 of 0.9) (Fig. 1D). These values are in good agreement with the theoretical molecular mass of 28.9 kDa. All experiments were performed on a Beckman Optima XL-I at the Center for Analytical Ultracentrifugation of Macromolecular Assemblies (CAUMA) at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. SV data were analyzed with the UltraScan software (42, 43). Calculations were performed at the Texas Advanced Computing Center at the University of Texas at Austin and at the Bioinformatics Core Facility at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio as described in reference 44. All Grft samples were measured in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 50 mM NaCl. All data were collected at 20°C, and samples were spun at 60 krpm using standard titanium 2-channel centerpieces (Nanolytics, Potsdam, Germany). The protein concentrations ranged from 4.2 μM (OD230 of 0.3) to 12.6 μM (OD230 of 0.9). The partial specific volume of the Grft-linker-Grft construct was determined to be 0.711 cm3/g by protein sequence according to the method by Durchschlag as implemented in UltraScan. All data were first subjected to two-dimensional spectrum analysis with simultaneous removal of time-invariant noise (45) and then to enhanced van Holde-Weischet analysis (36) and genetic algorithm refinement (39, 40), followed by Monte Carlo analysis (41).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) studies of Grft obligate dimer interaction with HIV gp120.

To test the binding of each Grft variant to HIV gp120, enzyme-linked immunosorbent binding assays were used as described previously (7, 46). In brief, 100 ng HIV-1 strain ADA gp120 (ImmunoDiagnostic) was used to coat each well of a 96-well plate (Maxisorp Immunoplate; Nalge Nunc) overnight at 4°C. Then the plate was blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. Serial dilutions of wild-type Grft as well as variants were added to triplicate wells and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After the plate was washed, a 1:1,000-fold dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), which can detect the N-terminal His tag on Grft, was added according to the company's instructions. Then the substrate for horseradish-peroxidase (2,2′-azinobis 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid [ABTS]) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added, and the signal was determined by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis.

All interaction studies were performed with a Biacore T200 instrument (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) at 25°C in HBS-P running buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% surfactant P20; pH 7.4). Recombinant gp120 proteins from the HIV-1(IIIB) strain (referred to as strain IIIB) ImmunoDiagnostics Inc., Woburn, MA) and the HIV-1 strain ADA (ImmunoDiagnostics) and recombinant gp41 protein from the HIV-1(HxB2) strain (Acris Antibodies GmbH, Herford, Germany) were covalently immobilized on the carboxymethylated dextran matrix of a CM5 sensor chip in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0, using standard amine coupling chemistry. A reference flow cell was used as a control for nonspecific binding and refractive index changes. The test compounds were serially diluted in running buffer using 2-fold dilution steps. Grft samples were injected for 2 min at a flow rate of 45 μl/min, and the regeneration pulse was 1 injection of glycine-HCl, pH 1.5. The experimental data were fit using the 1:1 binding model (Biacore T200 evaluation software 1.0) to determine the binding kinetics.

Viral reagents.

Viral plasmids containing the env gene from HIV-1 were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. HIV-1 ADA (R5) was received from Howard Gendelman. Plasmid pSV-JRFL (R5) was a kind gift from Nathaniel Landau (47). pCAGGS-SF162-gp160 (R5) was from Leonidas Stamatatos and Cecilia Cheng-Mayer. PVO clone 4 (PVO.4, SVPB11) and AC10.0 clone 29 (SVPB13) were from David Montefiori and Feng Gao (48). pWITO4160 clone 33 (SVPB 18) was from B. H. Hahn and J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez (48). DU156 clone 12 (SVPC3) was from D. Montefiori, F. Gao, S. Abdool Karim, and G. Ramjee. DU422 clone 1 (SVPC5) was from D. Monteriori, F. Gao, C. Williamson, and S. Abdool Karim (49, 50). ZM53M.PB12 (SVPC11), ZM109F.PB4 (SVPC13), and ZM135M.PL10a (SVPC15) were from E. Hunter and C. Derdeyn (51). pSG3Δenv was from John C. Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu (52, 53). Recombined human soluble CD4 (sCD4) and HIV antibodies were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, as follows: human sCD4 from Progenics and HIV-1 gp120 monoclonal antibody (IgG b12) from Dennis Burton and Carlos Barbas (54–57).

Virus capture ELISA.

Different concentrations of Grft variants were used to coat a 96-well plate at 4°C overnight. The wells were then washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–Tween 20 and blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. Virus in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was added into each well and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 4 h, followed by washing the wells 3 times using DMEM. Viruses were lysed using 0.5% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 min, and the supernatant containing viral lysate was transferred to a commercial p24 capture ELISA plate (Immuno Diagnostic) and incubated at 4°C overnight. The detector was added according the manufacturer's instructions. The signal was determined by measuring OD450.

Single-round infection assays.

TZM-bl cells stably expressing CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 coreceptors were maintained in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Ten thousand cells per well were first seeded into a 96-well plate for 1 day. The medium was then changed 3 h before the assay and made to a volume of 50 μl per well. Then a serial dilution of Grft variants were added from the top row to the bottom row as follows. Twenty microliters of the Grft variant was added into the first row and mixed with culture medium. Then 20 μl medium was removed and added into the second row, and so on. Virus (50 to 100 ng p24) was then added into each well containing different Grft variants. The medium was changed after 24 h, and cells were incubated for another 24 h. PBS containing 0.5% NP-40 was used to lyse the cells, and substrate chlorophenol red-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG; Calbiochem) was added. The absorbance signal was measured at 570 nm and 630 nm. The ratio of the signal at 570 nm to that at 630 nm for each well was calculated. Fifty percent effective concentrations (EC50s) were determined using a linear equation fitted between two data points surrounding 50% inhibition. For presentation purposes, data shown in the figures were plotted and fitted as curves using a four-parameter logistic equation in Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

Anti-HIV assays in CEM cell cultures.

CEM cells (5 × 105 cells per ml) were suspended in fresh culture medium and infected with HIV-1 strain IIIB at 100 times the 50% cell culture infective dose (CCID50) per ml of cell suspension, of which 100 μl was then mixed with 100 μl of the appropriate dilutions of the test compounds. After 4 to 5 days at 37°C, HIV-1-induced syncytium formation was recorded microscopically in the cell cultures. The EC50 corresponds to the compound concentration required to inihibit syncytium formation by 50% in the virus-infected CEM cell cultures.

Grft-induced CD4 binding site exposure.

CD4 binding site exposure in gp120 was carried out as described previously (31). Briefly, anti-gp120 antibody b12, which detects the CD4 binding site on gp120, was used to coat a 96-well plate at 4°C overnight. The next day, the plate was washed and blocked with BSA. Different concentrations of Grft variants (3.2 nM, 16 nM, and 80 nM) were preincubated with HIV virions at 37°C for 1 h and then added to the b12-coated plate. After 2 h of incubation, the plate was washed, and bound virus was lysed using 0.5% Triton X-100. The virus lysate was then transferred to a commercial p24 ELISA plate (Immuno Diagnostic), and p24 was measured by following the manufacturer's instructions. Figure 3A and B show data from the 16 nM Grft incubation.

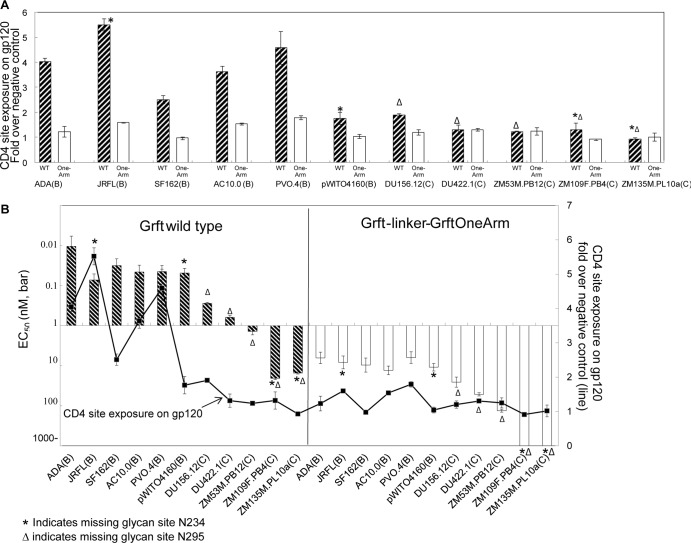

Fig 3.

(A) Bar graph showing CD4 binding site exposure in HIV-1 gp120 mediated by Grft or its dimer variants. HIV-1 capture by monoclonal antibody b12 (which binds to gp120 at the CD4 binding site) is shown for several strains that were preincubated with 16 nM Grft (striped bars) or Grft-linker-Grft OneArm (white bars). The data are shown as a fold difference relative to the negative control, which is the amount of virus captured by the b12 antibody with no preincubation of the virus with Grft. (B) Correlation of the antiviral EC50s of wild-type Grft and Grft-linker-Grft OneArm to the level of gp120 CD4 binding site exposure that is induced by Grft or Grft-linker-Grft OneArm. The EC50 is plotted on a log scale. For subtype B strains ADA, JRFL, AC10.0, and PVO.4, Grft induces a high level of CD4 binding site exposure.

Cell surface gp120 shedding.

Cell surface gp120 shedding was carried out as described previously (58, 59). Briefly, 293FT cells were transfected with the HIV JRFL, PVO.4, ZM53M.PB12, or ZM109M.PB4 plasmid using the Roche X-treme transfection reagent. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were collected, washed with PBS, and concentrated to 2 × 107 cells per ml. Cells were then aliquoted to microcentrifuge tubes (200 μl per tube). Cells were then centrifuged at low speed for 5 min; then 160 μl supernatant was removed. Different concentrations of soluble CD4 or Grft variants were added and mixed gently with cells. The mixture was then put into a 37°C incubator for 1 h and gently mixed every 20 min. The cells were then centrifuged, and the supernatant containing shed gp120 was collected and separated using SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was carried out using the mouse anti-HIV gp120 antibody (Immuno Technology) detecting a linear epitope on gp120, followed by detection using an anti-mouse IgG antibody–HRP conjugate (Promega). Metal-enhanced 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (Thermo Fisher) was then added, and the resulting image was processed using a bioimaging system (UVP).

RESULTS

Design of the obligate griffithsin dimer.

To study the role of the Grft dimer, we designed an obligate dimer in which the C terminus of one monomeric subunit was covalently linked by a 16-amino-acid (Gly-Ser) linker to the N terminus of a second subunit. This “Grft-linker-Grft” was expressed and purified. The 15N correlation spectrum (heteronuclear single quantum coherence [HSQC]) of the protein is very similar to that of the wild-type protein, strongly indicating that the obligate dimer has the same structural properties (Fig. 1B). To confirm that Grft-linker-Grft is indeed a dimer and has not associated with other units to make a higher-order oligomer, analytical ultracentrifugation was carried out; the results were consistent with a single dimer unit of 28.9 kDa (Fig. 1C and D). As noted above and shown in Fig. 1A, each Grft monomer has three carbohydrate-binding sites (CBS). Thus, this obligate dimer has 6 CBS, 3 on each monomer, with the distance between the carbohydrate binding faces on each subunit being around 47 Å (23).

To determine the role of two subunits in the dimer versus one, all three carbohydrate binding sites were removed from one of the monomers in Grft-linker-Grft by mutating the critical Asp at each site in one of the monomers. This variant, “Grft-linker-Grft OneArm” has one wild-type subunit and one subunit containing the substitutions D30A, D70A, and D112A in its CBS. We have previously shown that this triple substitution essentially removes the ability of the subunit to bind mannose (25). In order to determine whether substitutions on each of the two subunits of Grft dimer are equivalent, the 3 CBS on either the N-terminal or C-terminal subunit were triply mutated. It was found that the triple substitution on the N-terminal subunit of the Grft obligate dimer behaved the same as the triple substitution of the C-terminal subunit of the obligate dimer, both in pseudoviral assays and binding ELISAs (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Similarly, the NMR characteristics of the two one-armed variants were very similar, as judged by 15N HSQC spectra (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This indicates that the two Grft subunits are equivalent, so we proceeded to work with the triple substitution on the C-terminal domain of Grft-linker-Grft (leaving the N-terminal domain in its wild-type form) and refer to this as Grft-linker-Grft OneArm. 15N correlation spectra of this one-armed variant show a folded protein with peaks similar to those for both the wild-type protein (likely from the wild-type subunit) and the triple variant reported previously (from the other subunit) (25) (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material), indicating that this one-armed dimer does have one subunit as a wild-type Grft subunit and the other subunit as a triply mutated Grft subunit. As a negative control, the three carbohydrate binding sites for each monomer of the linked dimer were also mutated (i.e., all six sites were mutated to Ala) (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material), and this protein was nicely folded. This Grft-linker-Grft with two defective functional arms had very little function in a pseudoviral assay at the highest concentration tested (>1,000 nM). The HSQC spectra of this no-arm dimer also showed spectral characteristics similar to those shown by the unlinked Grft triple variant “Grft Triple D30A/D70A/D112A” (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material), so for convenience of purification, the unlinked triple variant is used in this work (except for the SPR studies) as a negative control (25).

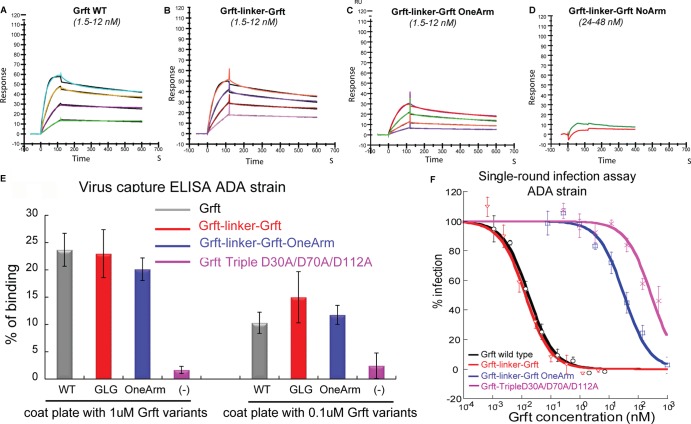

Obligate Grft dimer binding to gp120.

ELISAs were carried out to determine the ability of the obligate Grft dimers to bind to immobilized, recombinant gp120 (strain ADA). As shown in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material, Grft-linker-Grft and Grft-linker-Grft OneArm bind about as well as wild-type Grft to HIV-1 ADA, while the triple variant, Grft Triple D30A/D70A/D112A binds poorly, as expected. To obtain more-quantitative results, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis was carried out. These experiments showed that Grft-linker-Grft binds immobilized, monomeric gp120 derived from strain ADA and strain IIIB quite well, about 2- to 2.5-fold worse than wild-type Grft (Table 1 and Fig. 2A to D; see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm also binds well to gp120 compared to Grft-linker-Grft, with a dissociation constant (KD) about 2-fold higher (382 to 386 pM versus 164 to 176 pM). Also, wild-type Grft and Grft-linker-Grft bind at equally high affinity to gp41 and to gp120, whereas Grift-linker-Grft OneArm binds gp41 less well, at about 20-fold lower efficacy than wild-type Grft (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic dataa for the interaction of Grft and its variants with immobilized HIV-1 envelope proteins gp120ADA, gp120IIIB, and gp41HxB2

| Grft variant | gp120 IIIB (X4) |

gp120 ADA (R5) |

gp41 HxB2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD (pM) | kon (1/M · s) | koff (1/s) | KD (pM) | kon (1/M · s) | koff (1/s) | KD (pM) | kon (1/M · s) | koff (1/s) | |

| Wild type | 69.3 ± 5.5 | (1.93 ± 1.51)E+07 | (1.29 ± 0.96)E−03 | 65.5 ± 9.2 | (2.15 ± 1.52)E+07 | (1.30 ± 0.79)E−03 | 64.9 ± 18.7 | (1.47 ± 0.62)E+07 | (1.04 ± 0.62)E−03 |

| Grft-linker-Grft | 175.7 ± 22.6 | (4.91 ± 0.27)E+06 | (8.61 ± 1.17)E−04 | 163.5 ± 21.5 | (5.98 ± 1.19)E+06 | (9.97 ± 3.26)E−04 | 101.2 ± 2.4 | (6.63 ± 0.40)E+06 | (6.70 ± 0.36)E−04 |

| Grft-linker-Grft OneArm | 386.2 ± 121.7 | (5.15 ± 2.07)E+06 | (1.92 ± 0.98)E−03 | 381.5 ± 79.4 | (5.67 ± 1.24)E+06 | (2.12 ± 0.50)E−03 | 1,299 ± 1,148 | (7.42 ± 2.33)E+06 | (1.11 ± 1.13)E−03 |

| Grft-linker-Grft NoArm | NBb | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB | NB |

KD, dissociation equilibrium constant; kon, association rate constant; koff, dissociation rate constant. The P values for interactions with gp120IIIB are 0.0001 (wild-type Grft versus Grft-linker-Grft) and 0.0027 (wild-type Grft versus Grft-linker-Grft OneArm). The P values for interactions with gp120ADA are 0.0007 (wild-type Grft versus Grft-linker-Grft) and 0.0019 (wild-type-Grft versus Grft-linker-Grft OneArm).

NB, no specific binding observed at 12 nM. At concentrations higher than 12 nM (i.e., 24 and 48 nM), a weak binding signal was observed.

Fig 2.

(A to D) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensorgrams of Grft variants binding to immobilized gp120ADA. Shown is kinetic analysis of the interactions of wild-type (WT) Grft, obligate dimer Grft-linker-Grft, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm, and the negative control (obligate dimer with no functional arms, i.e., the D30A/D70A/D112A substitutions in both subunits) with immobilized HIV-1 ADA gp120. Serial 2-fold analyte dilutions (covering a concentration range from 1.5 to 12 nM in panels A to C and 24 to 48 nM in panel D) were injected over the surface of the immobilized gp120. The experimental data (colored curves) were fit using a 1:1 binding model (black lines) to determine the kinetic parameters. The biosensor chip density of gp120 was 90 response units (RU). (E) Virus capture ELISA indicates the ability of Grft and its variants to bind to the viral surface. Wild-type Grft and the obligate dimer Grft-linker-Grft bind well to the HIV spike. The one-armed obligate dimer Grft-linker-Grft OneArm also binds well to the viral spike, with very little, if any, apparent loss of binding affinity. The Grft containing the triple substitution D30A/D70A/D112A (in both arms) shows essentially no virus binding, as expected. The experiment was repeated 3 times. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from a triplicate experiment. (F) Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by Grft variants in single-round virus assays. Typical results are shown from an experiment in triplicate using R5 subtype B strain ADA. Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from a triplicate experiment.

The above data were obtained with recombinant gp120 (which is a monomer), whereas gp120 occurs as a trimer in the envelope of the native virus particle (60–63). However, it was recently shown that the kinetic interactions obtained for several carbohydrate binding agents (including Grft) with monomeric gp120 were similar if trimeric gp120 was used in SPR-based assays (64). To further probe the ability of Grft variants to bind trimeric gp120, we used virus capture ELISAs to measure the ability of the obligate dimers to bind to trimeric gp120 (65). In these experiments, the Grft variant was used to coat a plate, followed by incubation with pseudovirus. The amount of virus that the Grft was able to bind was measured by a subsequent p24 ELISA. As shown in Fig. 2E, both Grft-linker-Grft and Grft-linker-Grft OneArm bound well to the pseudovirus (strain ADA). The negative control containing the triple substitution D30A/D70A/D112A (in both arms) was found to bind poorly to trimeric gp120 by SPR as expected. Testing of the binding of some Grft variants to trimeric gp140 by SPR analysis generated similar data as with monomeric gp120 (64), indicating that both forms of gp120 provide relevant results.

Anti-HIV function of the obligate dimer.

Inhibition assays were carried out with several HIV-1 strains of single-round pseudovirus. As shown in Table 2, Grft-linker-Grft showed pronounced inhibition of the HIV-1 strains that were tested, including a variety of subtype B and subtype C strains. For example, the obligate dimer inhibited HIV-1 infection by strain ADA at an EC50 of 0.012 nM (compared to 0.011 nM for the wild-type protein). However, the one-armed obligate dimer variant was much less potent for each strain tested, with EC50s being 84- to 609-fold worse than those for the wild-type protein in single-round infection assays for R5 strains. For strain ADA, in which SPR showed reduced binding by Grft-linker-Grft OneArm by only 5-fold, the antiviral inhibition potency was reduced by 609-fold (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 2F). In replication-competent virus assays using CEM cells, a 1,010-fold decrease in antiviral activity was observed for the Grft-linker-Grft OneArm obligate dimer compared to the wild-type dimer with X4 strain IIIB. Together with the binding data, these functional data strongly suggest that Grft needs only one functional arm to bind with high affinity to HIV-1 gp120 but that it requires both arms to exert full antiviral function.

Table 2.

EC50s for single-round infection assay for wild-type Grft, the obligate Grft-linker-Grft dimer, and the Grft-linker-Grft OneArm dimera

| Subtype and strainb | Grft EC50 (nM) | Grft-linker-Grft (obligate dimer) |

Grft-linker-Grft OneArm |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) | Fold worse than WTc | EC50 (nM) | Fold worse than WT | ||

| Subtype B | |||||

| ADA | 0.0105 ± 0.0084 | 0.0118 ± 0.0046 | 1 | 6.39 ± 2.5 | 609 |

| JRFL* | 0.0725 ± 0.030 | 0.0533 ± 0.016 | 0.7 | 8.26 ± 3.7 | 114 |

| SF162 | 0.0316 ± 0.015 | 0.0253 ± 0.030 | 0.8 | 9.63 ± 4.8 | 305 |

| AC10.0 | 0.0458 ± 0.022 | 0.0567 ± 0.050 | 1.2 | 13.1 ± 3.7 | 286 |

| PVO.4 | 0.0445 ± 0.0066 | 0.0292 ± 0.0013 | 0.7 | 6.28 ± 2.5 | 141 |

| pWITO4160.33* | 0.0484 ± 0.015 | 0.0509 ± 0.087 | 1 | 10.9 ± 2.6 | 225 |

| IIIB (X4) | 0.06 ± 0.0 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 1 | 60.6 ± 19 | 1,010 |

| Subtype C | |||||

| DU156.12Δ | 0.276 ± 0.015 | 0.205 ± 0.010 | 0.7 | 25.8 ± 8.8 | 93 |

| DU422.1Δ | 0.619 ± 0.079 | 0.613 ± 0.028 | 1 | 51.9 ± 5.0 | 84 |

| ZM53 M.PB12Δ | 1.39 ± 0.31 | 1.43 ± 0.12 | 1.0 | 133 ± 12 | 96 |

| ZM109F.PB4Δ* | 20.6 ± 1.5 | 16.1 ± 3.14 | 0.8 | >1,000 | >49 |

| ZM135 M.PL10aΔ* | 15.2 ± 2.9 | 13.1 ± 1.5 | 0.9 | >1,000 | >66 |

Each experiment was independently repeated at least 3 times in triplicate, and the ± values are the standard deviations of the EC50s from all experiments. The experiments were carried out with TZM-bl target cells except for the experiments with the X4-tropic strain IIIB, which were carried out with CEM target cells. In this assay system, HIV-induced syncytium formation was examined microscopically at day 4 postinfection.

*, missing glycan site on N234; Δ, missing glycan site on N295.

Decrease in potency compared to wild-type Grft.

Alexandre et al. (12) have shown that the two high-mannose glycans at N234 and N295 are important for Grft function, with data suggesting that deletion of these two glycans could lead to marked loss of sensitivity to Grft. Here, with largely different HIV-1 strains, Grft and its variants were tested against a variety of HIV strains from both subtype B and subtype C (subtype C strains usually lack the N295 site). Table 2 shows the antiviral EC50s against each strain in single-round viral assays, while Table 3 lists the predicted high-mannose glycan sites for each strain. In the HIV strains tested, there appears to be a high antiviral potency by Grft against HIV-1 strains lacking the glycosylation site at N234, while strains with the glycan site at N295 missing show a somewhat lower sensitivity to Grft (but still have EC50s of about 1 nM or better). Strains lacking both sites at N234 and N295 show a loss of sensitivity to Grft by more than 2 orders of magnitude compared to HIV-1 strains having both N-glycan sites preserved (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Predicted high-mannose glycosylation patterns of HIV-1 strainsa

| Strain | Clade | Predicted no. of high-mannose sites | Presenceb of glycosylation site: |

Total no. of glycan sites (reference) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 230 | 234 | 241 | 262 | 289 | 295 | 332 | 339 | 386 | 392 | 448 | ||||

| ADA | B | 9 | * | * | 22 (92) | |||||||||

| JRFL | B | 8 | * | * | * | 23 (93) | ||||||||

| SF162 | B | 9 | * | * | 21 (94) | |||||||||

| AC10.0 | B | 8 | * | * | * | 24 | ||||||||

| PVO.4 | B | 9 | * | * | 28 | |||||||||

| pWITO4160.33 | B | 9 | * | * | 25 | |||||||||

| IIIB | B | 11 | 24 | |||||||||||

| Du156.12 | C | 8 | * | * | * | 22 | ||||||||

| Du422.1 | C | 8 | * | * | * | 24 | ||||||||

| ZM53M.PB12 | C | 8 | * | * | * | 25 | ||||||||

| ZM109F.PB4 | C | 8 | * | * | * | 23 | ||||||||

| ZM135M.PL10a | C | 8 | * | * | * | 23 | ||||||||

Predicted glycosylation sites from http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GLYCOSITE/glycosite.html.

*, glycosylation site is not present.

CD4 binding site exposure on gp120 by Grft variants.

A potentially important aspect of the mechanism of Grft is whether the Grft dimer is able to affect the conformation of HIV-1 gp120 and whether this effect on the gp120 conformation is related to Grft potency. One way to detect conformational changes is to use antibodies that bind to specific sites on the surface of gp120, such as the CD4 binding site that is accessible only at some stages during the course of viral entry (66, 67). It has been reported that wild-type Grft is able to affect the structure of gp120 by exposing the CD4 binding site for 6 strains from subtype B and subtype C upon binding (31). While the relationship between this action and inhibition of HIV is not yet known, the finding strongly suggests that Grft may function not simply by binding to gp120 but also by altering its conformation.

The ability of wild-type Grft to expose the CD4 binding site of gp120 was examined by virus capture. Briefly, a plate was coated with antibody b12, which binds to gp120 at the CD4 binding site (54–57). Then single-round virus was preincubated with Grft or its variants and then allowed to bind to the antibody on the plate. The amount of virus bound was measured by subsequent p24 assays. As shown in Fig. 3A, wild-type Grft induced CD4 exposure quite well in a variety of clade B strains, including ADA, JRFL, SF162, AC10.0, and PVO.4. The Grft-linker-Grft obligate dimer showed effects in inducing CD4 binding site exposure similar to those of wild-type Grft on 4 strains tested (see Fig. S6A in the supplemental material). However, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm was significantly less effective in this property for each virus strain, resulting in CD4 binding site exposure in the presence of this protein similar to that of the negative control with virus alone. This suggests that Grft requires both arms of the dimer to facilitate CD4 binding site exposure on gp120 in clade B strains.

The present work and other investigators have shown that HIV strains lacking glycan sites at N234 and N295 on gp120 are less sensitive to Grft (12). Therefore, we explored whether HIV strains lacking these glycan sites affect the ability of Grft to mediate CD4 binding site exposure on gp120. Experiments were carried out with several strains from both subtype B and subtype C. As shown in Fig. 3A, it appears that the lack of the glycosylation site at position N234 of gp120 does not markedly affect the ability of Grft to mediate CD4 exposure. However, in HIV-1 strains lacking the glycosylation site at position 295, the ability of Grft to mediate CD4 binding site exposure in gp120 was greatly reduced: in three separate strains (Du156.12, DU422.1, and ZM53M.PB12), wild-type Grft showed little or no ability to expose the CD4 binding site. In HIV strains lacking both the N234 and N295 glycosylation sites (ZM109F.PB4 and ZM135M.PL10a), Grft was unable to significantly mediate the exposure of the CD4 binding site in gp120, even at the highest concentration of Grft used (80 nM) (data not shown). In each viral strain, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm was able to induce only very low (if any) CD4 binding site exposure in gp120 above the control (Fig. 3A).

Anti-HIV assays were carried out with single-round virus from each of these strains to determine whether there is a correlation between the ability of Grft to induce CD4 binding site exposure and Grft antiviral potency. Figure 3B shows that in each case where CD4 exposure is relatively high (i.e., more than about 2.5-fold higher than the control), Grft was very potent (EC50 of 0.07 nM or lower). In cases where the Grft-mediated CD4 binding site exposure was low (less than 2-fold higher than the control), the antiviral potency of Grft was also lower, with Grft exhibiting a marked loss of potency compared to the average potency against the “high-CD4-exposure” HIV-1 strains. This was particularly true for HIV-1 strains lacking both glycosylation sites at N234 and N295, which showed the least sensitivity to Grft. However, one notable exception was the clade B strain pWITO4160, which was highly sensitive to Grft (EC50 = 0.048 nM) but showed only a small amount of CD4 binding site exposure (Fig. 3B). In all cases, as a rule, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm showed very little ability to mediate CD4 exposure (as previously described) and also showed reduced antiviral potency: 84- to 609-fold worse than the wild-type inhibitor (Table 2).

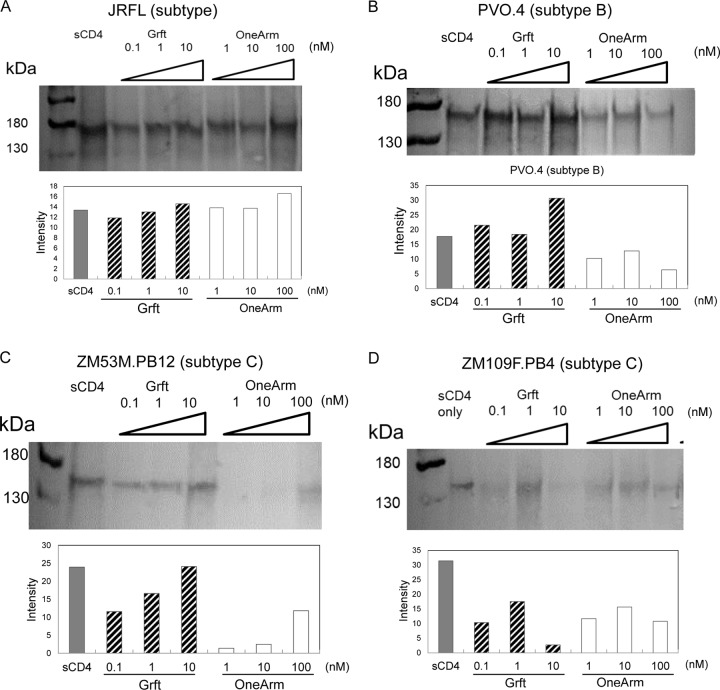

The effect of Grft on gp120 shedding.

It has been reported that soluble CD4 induces dissociation of gp120 from HIV particles and that this CD4-induced env shedding may impair the functional trimeric spike (68), though the exact role of CD4-induced shedding during viral entry is not clear (69, 70). Broadly neutralizing antibodies have also been reported to have different effects on gp120 shedding (59, 71, 72). Here, Western blot analysis was carried out on supernatants of cells transfected with HIV-1 gp120 from both clade B and clade C and incubated with Grft variants. Figure 4 shows that the soluble CD4 (sCD4) control is able to induce shedding from the surface of each strain, as expected. For clade B strains (JRFL and PVO.4), Grft also induces shedding. The subtype B strain JRFL lacks a high-mannose glycan site at N234 but still shows large amounts of shedding in the presence of Grft. The obligate dimer Grft-linker-Grft also induces env shedding from the cell surface (see Fig. S6B in the supplemental material) for strains JRFL (subtype B), PVO.4 (subtype B), ZM53M.PB12 (subtype C), and ZM109F.PB4 (subtype C). Grft-linker-Grft OneArm generally had less effect on shedding, particularly for the PVO.4 strain, despite using concentrations for the one-armed dimer that are 10-fold higher than that for wild-type Grft to account for differences in the ability to bind virus. For clade C strains (ZM53M.PB12 and ZM109F.PB4), Grft itself induces less shedding than soluble CD4, while the one-armed dimer is even less effective at mediating gp120 shedding (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Shedding of env from HIV-transfected cells for JRFL (subtype B), PVO.4 (subtype B), ZM53M.PB12 (subtype C), and ZM109F.PB4 (subtype C). The left lane is the molecular mass ladder. sCD4 (25 μg/ml) was incubated with transfected 293FT cells (lane 2) and used as a positive control. Different concentrations of wild-type Grft (0.1 nM, 1 nM, and 10 nM) or Grft-linker-Grft OneArm (1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM) were incubated with env-transfected 293FT cells. The bottom of each panel shows the intensity of bands as determined by densitometry, calculated from the program ImageJ (96).

DISCUSSION

Griffithsin (Grft) is a lectin with broad activity against a variety of viruses, including HIV, hepatitis C virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and herpes simplex virus (17–20). Grft binds high-mannose structures on viral envelope surfaces, such as HIV gp120. Structural work (23) and biochemical studies (25) confirm that the protein is a tight dimer, with each subunit containing three mannose binding sites that are critical for function. A monomeric variant of Grft was shown to be unable to effectively inhibit HIV, underscoring the importance of the dimer form (8). Its high antiviral activity against HIV in particular makes Grft a highly promising candidate for a microbicide, which could be used to prevent the sexual spread of the virus. The present work elucidates an important component of the mechanism of Grft, namely, that its mode of inhibition of HIV is not simply based on its ability to bind gp120; it also requires two functional dimer subunits.

Investigations have been carried out on other carbohydrate-binding HIV inhibitors. The prokaryotic lectin cyanovirin-N has two carbohydrate binding sites per monomer and has been observed as both a dimer and a monomer, both of which are apparently very potent (73, 74). At least two carbohydrate binding sites are necessary for activity because mutated monomers having only one CBS are not functional unless two defective monomers are cross-linked (containing in total two functional CBS) (32). Moreover, the covalent linking of the two functional monomers of cyanovirin (giving 4 CBS) also led to a moderately increased potency over that of the wild-type protein although higher-order oligomers apparently did not have increased potency (33). The neutralizing antibody 2G12 binds high-mannose carbohydrates on gp120 (75–78) and has an unusual domain-swapped structure with a shorter distance between the two primary binding sites (35 Å compared to 150 Å for a typical IgG antibody); this leads to 2 additional potential CBS (79, 80). Dimeric and polymeric 2G12 has also been reported to be more effective in neutralizing HIV (81–83). The distance between CBS may be important in optimal HIV inhibition because the apparently ideal distance between the 2 CBS for cyanovirin appears to be around 40 Å (32), the 2G12 primary binding sites are 35 Å apart, and the X-ray structure of Grft shows about a 47-Å distance between the two carbohydrate binding arms (23). Therefore, effective HIV inhibition appears in these cases to arise from multisite carbohydrate binding of defined (around 40-Å) distance, though these various proteins (which do tend to effectively compete with each other [12, 16, 75, 84]) may not always bind at the same high-mannose glycan sites.

Mechanistically, three major types of action could be envisioned for Grft function against HIV. First, tight binding to the surface of gp120 could sterically impede gp120 from binding the host cell by blocking key interactions with CD4 and/or the coreceptor. This could occur with Grft binding at various locations on gp120, with some mannose-containing glycan sites being more important than others. Avidity gained from multisite binding could be an important factor in this. Second, Grft could alter the conformation of gp120 so gp120 is less effective at mediating entry by the virus. The conformational change could affect CD4 binding, coreceptor binding, or some other entry processes. Finally, Grft could potentially cross-link two different gp120 subunits by binding a glycan unit on each subunit. gp120 is a trimer, so this could conceivably occur with two separate trimer spikes (less likely) or with two different gp120 monomers within a single trimer. It is likely that more than one of these mechanisms concomitantly functions for Grft inhibition. For example, a mechanism involving a structural change in gp120 and/or cross-linking of individual gp120 molecules may be a major inhibitory mechanism and can function for binding at particular glycan sites, while Grft could sometimes simply block other necessary interactions when it is bound at other mannose glycan sites. The relative importance of each mechanism for inhibition may depend on the viral strain and its individual glycosylation pattern.

In the present work, we have examined the role of the Grft dimer in HIV inhibition by making an obligate dimer, Grft-linker-Grft, and a one-armed obligate dimer, Grft-linker-Grft OneArm (with one functional subunit and one subunit having all three mannose-binding sites mutated). These were tested for various aspects of function, including the ability to bind gp120, to inhibit HIV, and to effect a structural change in gp120. It was found that the obligate dimer Grft-linker-Grft very much resembled the wild-type protein both in structure and in function, indicating that, as expected, native Grft likely acts as a dimer. However, while Grft-linker-Grft OneArm was minimally reduced in ability to bind gp120, this Grft variant showed a dramatic reduction in inhibitory functions, both in single-round and replication-competent virus assays. While quantitative testing of Grft binding to gp120 is presented here with two strains (either of X4 or R5 origin), other work (J. Balzarini, unpublished data) shows similar constants for binding to gp120 from at least one other HIV-1 strain. Given that Grft binds to surface high-mannose glycans and that known HIV-1 strains contain between 18 and 33 potential N-glycosylation sites, it is reasonable to expect that high binding affinity between Grft and most HIV-1 strains would be observed. In fact, the deletion (absence) from the viral envelope of only a few well-defined N-glycan locations on HIV-1 gp120 (viz., N234, N295, and N448) has been shown to result in a marked decrease in the antiviral activity of Grft (12, 33).

Our results demonstrate that both subunits of the Grft dimer are critical for its optimal anti-HIV function, but not for gp120 binding, suggesting that inhibition is not simply a “bind and block” phenomenon. Enhanced inhibition due to multisite binding can often be explained by the avidity effect of the inhibitor (33, 79). This is generally due to the increased “on rate” of the second (later) site after binding at the first site, which leads to overall better binding and less dissociation of the lectin from the virus (33). The present results are consistent with a contribution of avidity to the eventual effectiveness of Grft. Specifically, the one-armed obligate dimer has 3 fewer CBS and much lower HIV neutralization capability. However, the on rate for the one-armed dimer binding to gp120 is only 2- to 4-fold lower than that for the wild-type or the obligate dimer in SPR studies with gp120 (Table 1).

In addition to avidity effects, Grft might have additional functions which involve altering the conformation of gp120 to decrease viral entry ability. Grft may require two sites of (glycan) binding to affect the structure of gp120, in such a way enforcing a conformation that is somehow not competent to facilitate HIV entry to the host cell. To probe this possibility, we examined several possible structural conversions in gp120 and the effect of Grft on these. When initiating infection, gp120 first binds CD4 at a site that seems not to be fully accessible until CD4 is present, and it was recently shown that the presence of Grft allows a higher level of virus capture at the CD4 binding site (31). In our experiments, we show that Grft indeed affords higher levels of virus capture by the b12 antibody that binds gp120 at its CD4 binding site, while Grft-linker-Grft OneArm mediates viral capture only at the level of the negative control (Fig. 3A). In virtually every viral strain tested, Grft's ability to cause CD4 binding site exposure is strongly correlated with antiviral function. This indicates a correlation between the ability to manipulate the structure of gp120 and the anti-HIV activity of the protein and implicates both arms of the dimer as being necessary for these functions. While this does not prove that mediating a conformational change in gp120 plays a role in Grft inhibition, the data are consistent with the possibility of such a role for Grft in addition to high-affinity binding. Further experiments in this regard should clarify this issue.

The exposure of the CD4 binding site on gp120 is obviously important in productive infection by HIV, but given Grft's role as an inhibitor, it is clear either that the exposure of the CD4 binding site by Grft does not facilitate actual CD4 binding or that Grft somehow blocks entry after this step. It is also possible that this “exposure” is just part of a larger, overall conformational change to interfere with viral entry in a manner that is not yet known. Interestingly, different effects were observed for different HIV strains in the CD4 exposure experiments. In general, Grft showed higher levels of CD4 exposure in gp120 strains that retained glycosylation sites at positions N234 and N295 and lower levels of CD4 exposure relative to the negative control in gp120 strains that lacked glycosylation at N295 or at both N234 and N295. There was also a consistent correlation with the ability to mediate CD4 binding site exposure and the inhibition potency of Grft, with only one exception (clade B strain pWITO4160). In all cases, the one-armed dimer of Grft was largely unable to mediate exposure of the CD4 binding site and was also as much as 600-fold less potent in HIV inhibition. Therefore, it seems reasonable that this conformational change of gp120 may be related, at least in part, to Grft function.

An important question regarding an inhibitor that requires two arms for function is whether the inhibitor is actually cross-linking two different gp120 subunits. gp120 is a trimer on the surface of the virus, and the distance between the two arms of Grft (about 47 Å) could allow binding to putative glycosylation sites on two different gp120 monomers in the trimer (23, 85, 86). The role and importance of gp120 shedding in infection efficiency have not been defined, although shedding can occur as part of the conformational change in gp120 (69, 87, 88). Some HIV inhibitors apparently impair gp120 shedding and increase gp41 exposure, while other work indicates that CD4-induced shedding of gp120 does not correlate with subsequent membrane fusion (69, 89). The broadly neutralizing antibody b12 was shown to increase viral shedding (although there is some disagreement), while the recently discovered broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01 could not induce gp120 shedding (59, 72).

While it is not known whether an effect on gp120 shedding itself is a mechanism of drug inhibition, such a function could provide data regarding the ability of Grft to affect the gp120 conformation. We have measured the amount of gp120 that has been shed in the presence or absence of Grft (and CD4, which does induce shedding) using Western blots (58, 59). The results show that Grft in general does induce gp120 shedding, while the one-armed Grft dimer appears to be reduced in this ability, indicating that two arms of the dimer are more effective in causing shedding and suggesting that multisite binding or cross-linking by Grft may play a role in gp120 shedding. However, different effects were observed for different HIV strains, suggesting that Grft-induced env shedding may correlate with different glycan patterns on the viral surface.

Our findings that Grft is a highly active anti-HIV agent that inhibits infection of susceptible target cells by a broad variety of X4 and R5 HIV-1 strains, blocks syncytium formation between virus-infected and noninfected cells, prevents capture of virus particles by DC-SIGN-expressing cells, and blocks the subsequent transmission of such captured virus to CD4+ T lymphocytes make it a prime candidate drug for microbicide development (25, 90). In addition, it has an outstanding safety profile as a potential microbicide (14, 15). Indeed, recently, griffithsin has been proposed as the first antiretroviral drug in nonclinical use to be included in a microbicide trial for women living with HIV. This protein has been expressed in tobacco plants using transgenic plant technology, and it has been calculated that an environmentally controlled greenhouse producing 3,000 kg of leaf tissue per acre could yield >2 million doses per year, making its use as a candidate microbicide realistic (91; S. Hiller, presentation at the Forum for Collaborative HIV Research meeting on Future of PrEP and Microbicides, Washington, DC, 7 January 2013). It is therefore important to understand the mechanism of action of this lectin, both to further its development and to understand the properties that lead to the most valuable inhibitors. The combination of tight binding to gp120 and the use of multiple subunits to mediate inhibitory changes in gp120 by griffithsin may be used by other lectins or broadly neutralizing antibodies and may also be a desirable property for designing future HIV inhibitors.

In conclusion, this work provides evidence that both arms of the Grft dimer are necessary for its optimal anti-HIV function and that, in addition to allowing an increase in avidity, their role may be to manipulate the structure of gp120, thereby inhibiting the process of viral entry. Grft inhibition correlates with glycan patterns on the viral surface and with its ability to mediate CD4 binding site exposure in gp120. This work helps to explain previously reported results that HIV strains lacking glycosylation at both positions N234 and N295 are less sensitive to Grft (12). While the clade B strains (which are prevalent in North America and Western Europe) tend to retain both these sites, clade C strains (which are prevalent in Africa and Asia [49, 51]) tend to lack the glycosylation site at position N295. There may also be a relationship between Grft-mediated env shedding and viral inhibition. Our results have implications for the development of Grft as a microbicide.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH (R21 AI079777), 1P20MD005049-01 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, U.S. Army grant W911NF-11-1-0139, NCI P30 CA054174, and grants from the KU Leuven (PF 10/018, GOA 10/14, G-0528-12N). Computations were performed at the Texas Advanced Computing Center of the University of Texas, Austin, on Lonestar and Ranger with support from NSF TeraGrid allocation TG-MCB070039 (B.D.).

We thank Virgil Schirf for performing the sedimentation velocity experiments at the Center for Analytical Ultracentrifugation of Macromolecular Assemblies at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The technical assistance of Leen Ingels for the HIV assays is greatly appreciated.

We declare that we have no conflict of interests.

J.X., I.K., and P.J.L. conceived and designed the experiments. J.X. and P.J.L. conducted the experiments and wrote the paper. B.H. and J.B. conducted, analyzed the SPR data and performed the replication-competent viral assays with HIV-1 strain IIIB. B.D. performed and analyzed the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00332-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, Kharsany AB, Sibeko S, Mlisana KP, Omar Z, Gengiah TN, Maarschalk S, Arulappan N, Mlotshwa M, Morris L, Taylor D. 2010. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science 329:1168–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Quinones-Mateu ME, Vanham G. 2012. HIV microbicides: where are we now? Curr. HIV Res. 10:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Selhorst P, Vazquez AC, Terrazas-Aranda K, Michiels J, Vereecken K, Heyndrickx L, Weber J, Quinones-Mateu ME, Arien KK, Vanham G. 2011. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance or cross-resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors currently under development as microbicides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1403–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrientos LG, Gronenborn AM. 2005. The highly specific carbohydrate-binding protein cyanovirin-N: structure, anti-HIV/Ebola activity and possibilities for therapy. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 5:21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoorelbeke B, Huskens D, Ferir G, Francois KO, Takahashi A, Van Laethem K, Schols D, Tanaka H, Balzarini J. 2010. Actinohivin, a broadly neutralizing prokaryotic lectin, inhibits HIV-1 infection by specifically targeting high-mannose-type glycans on the gp120 envelope. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3287–3301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoorelbeke B, Van Damme EJ, Rouge P, Schols D, Van Laethem K, Fouquaert E, Balzarini J. 2011. Differences in the mannose oligomer specificities of the closely related lectins from Galanthus nivalis and Zea mays strongly determine their eventual anti-HIV activity. Retrovirology 8:10. 10.1186/1742-4690-8-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mori T, O'Keefe BR, Sowder RC, II, Bringans S, Gardella R, Berg S, Cochran P, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Jr, McMahon JB, Boyd MR. 2005. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J. Biol. Chem. 280:9345–9353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moulaei T, Shenoy SR, Giomarelli B, Thomas C, McMahon JB, Dauter Z, O'Keefe BR, Wlodawer A. 2010. Monomerization of viral entry inhibitor griffithsin elucidates the relationship between multivalent binding to carbohydrates and anti-HIV activity. Structure 18:1104–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanaka H, Chiba H, Inokoshi J, Kuno A, Sugai T, Takahashi A, Ito Y, Tsunoda M, Suzuki K, Takenaka A, Sekiguchi T, Umeyama H, Hirabayashi J, Omura S. 2009. Mechanism by which the lectin actinohivin blocks HIV infection of target cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:15633–15638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ziolkowska NE, Shenoy SR, O'Keefe BR, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Dwek RA, Wormald MR, Wlodawer A. 2007. Crystallographic, thermodynamic, and molecular modeling studies of the mode of binding of oligosaccharides to the potent antiviral protein griffithsin. Proteins 67:661–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu Q, Mahmood N, Shattock RJ. 2007. High-mannose-specific deglycosylation of HIV-1 gp120 induced by resistance to cyanovirin-N and the impact on antibody neutralization. Virology 368:145–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alexandre KB, Gray ES, Lambson BE, Moore PL, Choge IA, Mlisana K, Karim SS, McMahon J, O'Keefe B, Chikwamba R, Morris L. 2010. Mannose-rich glycosylation patterns on HIV-1 subtype C gp120 and sensitivity to the lectins, griffithsin, cyanovirin-N and scytovirin. Virology 402:187–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Emau P, Tian B, O'Keefe BR, Mori T, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Jiang Y, Bekele G, Tsai CC. 2007. Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J. Med. Primatol. 36:244–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kouokam JC, Huskens D, Schols D, Johannemann A, Riedell SK, Walter W, Walker JM, Matoba N, O'Keefe BR, Palmer KE. 2011. Investigation of griffithsin's interactions with human cells confirms its outstanding safety and efficacy profile as a microbicide candidate. PLoS One 6:e22635. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Keefe BR, Vojdani F, Buffa V, Shattock RJ, Montefiori DC, Bakke J, Mirsalis J, d'Andrea AL, Hume SD, Bratcher B, Saucedo CJ, McMahon JB, Pogue GP, Palmer KE. 2009. Scaleable manufacture of HIV-1 entry inhibitor griffithsin and validation of its safety and efficacy as a topical microbicide component. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:6099–6104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferir G, Huskens D, Palmer KE, Boudreaux DM, Swanson MD, Markovitz DM, Balzarini J, Schols D. 2012. Combinations of griffithsin with other carbohydrate-binding agents demonstrate superior activity against HIV type 1, HIV type 2, and selected carbohydrate-binding agent-resistant HIV type 1 strains. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 28:1513–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Keefe BR, Giomarelli B, Barnard DL, Shenoy SR, Chan PK, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Barnett BW, Meyerholz DK, Wohlford-Lenane CL, McCray PB., Jr 2010. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J. Virol. 84:2511–2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meuleman P, Albecka A, Belouzard S, Vercauteren K, Verhoye L, Wychowski C, Leroux-Roels G, Palmer KE, Dubuisson J. 2011. Griffithsin has antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5159–5167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishag HZ, Li C, Huang L, Sun MX, Wang F, Ni B, Malik T, Chen PY, Mao X. 2013. Griffithsin inhibits Japanese encephalitis virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Arch. Virol. 158:349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nixon B, Stefanidou M, Mesquita PM, Fakioglu E, Segarra T, Rohan L, Halford W, Palmer KE, Herold BC. 2013. Griffithsin protects mice from genital herpes by preventing cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 87:6257–6269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moncla BJ, Pryke K, Rohan LC, Graebing PW. 2011. Degradation of naturally occurring and engineered antimicrobial peptides by proteases. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2:404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Balzarini J. 2007. Targeting the glycans of glycoproteins: a novel paradigm for antiviral therapy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:583–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ziolkowska NE, O'Keefe BR, Mori T, Zhu C, Giomarelli B, Vojdani F, Palmer KE, McMahon JB, Wlodawer A. 2006. Domain-swapped structure of the potent antiviral protein griffithsin and its mode of carbohydrate binding. Structure 14:1127–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ziolkowska NE, Shenoy SR, O'Keefe BR, Wlodawer A. 2007. Crystallographic studies of the complexes of antiviral protein griffithsin with glucose and N-acetylglucosamine. Protein Sci. 16:1485–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xue J, Gao Y, Hoorelbeke B, Kagiampakis I, Zhao B, Demeler B, Balzarini J, Liwang PJ. 2012. The role of individual carbohydrate-binding sites in the function of the potent anti-HIV lectin griffithsin. Mol. Pharmacol. 9:2613–2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, Harris RJ, Thomas JN, Gregory TJ. 1990. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10373–10382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang M, Gaschen B, Blay W, Foley B, Haigwood N, Kuiken C, Korber B. 2004. Tracking global patterns of N-linked glycosylation site variation in highly variable viral glycoproteins: HIV, SIV, and HCV envelopes and influenza hemagglutinin. Glycobiology 14:1229–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhu X, Borchers C, Bienstock RJ, Tomer KB. 2000. Mass spectrometric characterization of the glycosylation pattern of HIV-gp120 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry 39:11194–11204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Doores KJ, Bonomelli C, Harvey DJ, Vasiljevic S, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. 2010. Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:13800–13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang X, Jin W, Griffin GE, Shattock RJ, Hu Q. 2011. Removal of two high-mannose N-linked glycans on gp120 renders human immunodeficiency virus 1 largely resistant to the carbohydrate-binding agent griffithsin. J. Gen. Virol. 92:2367–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alexandre KB, Gray ES, Pantophlet R, Moore PL, McMahon JB, Chakauya E, O'Keefe BR, Chikwamba R, Morris L. 2011. Binding of the mannose-specific lectin, griffithsin, to HIV-1 gp120 exposes the CD4-binding site. J. Virol. 85:9039–9050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matei E, Zheng A, Furey W, Rose J, Aiken C, Gronenborn AM. 2010. Anti-HIV activity of defective cyanovirin-N mutants is restored by dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 285:13057–13065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keeffe JR, Gnanapragasam PN, Gillespie SK, Yong J, Bjorkman PJ, Mayo SL. 2011. Designed oligomers of cyanovirin-N show enhanced HIV neutralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:14079–14084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Hu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. 1995. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6:277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garrett DS, Powers R, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. 1991. A common sense approach to peak picking in two-, three-, and four-dimensional spectra using automatic computer analysis of contour diagrams. J. Magn. Reson. 95:214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Demeler B, van Holde KE. 2004. Sedimentation velocity analysis of highly heterogeneous systems. Anal. Biochem. 335:279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brookes E, Boppana RV, Demeler B. 2006. Computing large sparse multivariate optimization problems with an application in biophysics, article 81. In SC '06 Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY. 10.1145/1188455.1188541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brookes E, Cao WM, Demeler B. 2010. A two-dimensional spectrum analysis for sedimentation velocity experiments of mixtures with heterogeneity in molecular weight and shape. Eur. Biophys. J. 39:405–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brookes E, Demeler B. 2006. Genetic algorithm optimization for obtaining accurate molecular weight distributions from sedimentation velocity experiments. Prog. Coll. Polym. Sci. 131:33–40 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brookes EH, Demeler B. 2007. Parsimonious regularization using genetic algorithms applied to the analysis of analytical ultracentrifugation experiments, p 361–368 In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY. 10.1145/1276958.1277035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Demeler B, Brookes E. 2008. Monte Carlo analysis of sedimentation experiments. Colloid Polym. Sci. 286:129–137 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Demeler B. 2011, posting date UltraScan version 9.9: a comprehensive data analysis software package for analytical ultracentrifugation experiments. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Demeler B. 2005. UltraScan: a comprehensive data analysis software package for analytical ultracentrifugation experiments, p 210–229 In Scott D, Harding S, Rowe A. (ed), Modern analytical ultracentrifugation: techniques and methods. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brookes E, Demeler B. 2008. Parallel computational techniques for the analysis of sedimentation velocity experiments in UltraScan. Colloid Polym. Sci. 286:139–148 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Demeler B. 2010. Methods for the design and analysis of sedimentation velocity and sedimentation equilibrium experiments with proteins. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 7, Unit 7 13. 10.1002/0471140864.ps0713s60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boyd MR, Gustafson KR, McMahon JB, Shoemaker RH, O'Keefe BR, Mori T, Gulakowski RJ, Wu L, Rivera MI, Laurencot CM, Currens MJ, Cardellina JH, II, Buckheit RW, Jr, Nara PL, Pannell LK, Sowder RC, II, Henderson LE. 1997. Discovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that binds viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1521–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Connor RI, Chen BK, Choe S, Landau NR. 1995. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology 206:935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, Voss G, Goepfert P, Gilbert P, Greene KM, Bilska M, Kothe DL, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Wei X, Decker JM, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 79:10108–10125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williamson C, Morris L, Maughan MF, Ping LH, Dryga SA, Thomas R, Reap EA, Cilliers T, van Harmelen J, Pascual A, Ramjee G, Gray G, Johnston R, Karim SA, Swanstrom R. 2003. Characterization and selection of HIV-1 subtype C isolates for use in vaccine development. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 19:133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li M, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Derdeyn CA, Morris L, Williamson C, Robinson JE, Decker JM, Li Y, Salazar MG, Polonis VR, Mlisana K, Karim SA, Hong K, Greene KM, Bilska M, Zhou J, Allen S, Chomba E, Mulenga J, Vwalika C, Gao F, Zhang M, Korber BT, Hunter E, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. 2006. Genetic and neutralization properties of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular env clones from acute and early heterosexually acquired infections in Southern Africa. J. Virol. 80:11776–11790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Mokili JL, Muldoon M, Denham SA, Heil ML, Kasolo F, Musonda R, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Korber BT, Allen S, Hunter E. 2004. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science 303:2019–2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani RB, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Wu X, Shaw GM, Kappes JC. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. 2003. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 422:307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Burton DR, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp SJ, Thornton GB, Parren PW, Sawyer LS, Hendry RM, Dunlop N, Nara PL. 1994. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science 266:1024–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burton DR, Barbas CF, III, Persson MA, Koenig S, Chanock RM, Lerner RA. 1991. A large array of human monoclonal antibodies to type 1 human immunodeficiency virus from combinatorial libraries of asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:10134–10137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Barbas CF, III, Bjorling E, Chiodi F, Dunlop N, Cababa D, Jones TM, Zebedee SL, Persson MA, Nara PL, Norrby E. 1992. Recombinant human Fab fragments neutralize human type 1 immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:9339–9343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roben P, Moore JP, Thali M, Sodroski J, Barbas CF, III, Burton DR. 1994. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:4821–4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, Stanfield RL, Julien JP, Ramos A, Crispin M, Depetris R, Katpally U, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Maloveste S, Liu Y, McBride R, Ito Y, Sanders RW, Ogohara C, Paulson JC, Feizi T, Scanlan CN, Wong CH, Moore JP, Olson WC, Ward AB, Poignard P, Schief WR, Burton DR, Wilson IA. 2011. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science 334:1097–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Li Y, O'Dell S, Walker LM, Wu X, Guenaga J, Feng Y, Schmidt SD, McKee K, Louder MK, Ledgerwood JE, Graham BS, Haynes BF, Burton DR, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR. 2011. Mechanism of neutralization by the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 monoclonal antibody VRC01. J. Virol. 85:8954–8967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]