Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have naturally evolved as suitable, high affinity and specificity targeting molecules. However, the large size of full-length mAbs yields poor pharmacokinetic properties. A solution to this issue is the use of a multistep administration approach, in which the slower clearing mAb is administered first and allowed to reach the target site selectively, followed by administration of a rapidly clearing small molecule carrier of the cytotoxic or imaging ligand, which bears a cognate receptor for the mAb. Here, we introduce a novel pretargetable RNA based system comprised of locked nucleic acids (LNA) and 2′O-Methyloligoribonucleotides (2′OMe-RNA). The duplex shows fast hybridization, high melting temperatures, excellent affinity, and high nuclease stability in plasma. Using a prototype model system with rituximab conjugated to 2′OMe-RNA (oligo), we demonstrate that LNA-based complementary strand (c-oligo) effectively hybridizes with rituximab–oligo, which is slowly circulating in vivo, despite the high clearance rates of c-oligo.

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are widely used as diagnostic and therapeutic agents for cancer and inflammatory diseases. While mAbs alone may be therapeutically effective in redirecting the endogenous immune effectors to attack the target cells, a relatively small number of mAbs are successful by use of this approach alone (Scott et al., 2012). However, the remarkable affinity and specificity of mAbs makes them attractive carriers (HUGHES, 2010; Adair et al., 2012). These properties have been utilized effectively for mAb therapeutics with appended cytotoxic drugs for antibody drug conjugates or radionuclides for radioimmunotherapy (RIT) (Sharkey and Goldenberg, 2011). In addition, radionuclides conjugated to mAb are being used as radiotracers for gamma or positron emission tomography radioimmunoimaging (RII) (Boswell and Brechbiel, 2007). The radioactive constructs are typically prepared by conjugation of a radio-metal chelate or nuclide directly to the mAb. However, RIT and RII are underutilized due to radiation induced organ toxicities and poor pharmacokinetics and biodistributions of the mAb, respectively. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics are characterized by (1) prolonged circulation times, (2) poor diffusion into solid tumors leading to low therapeutic index, and (3) low signal-to-background ratios.

As an alternative strategy, a second generation of radioimmuno-conjugates was introduced that used engineered, smaller antibody fragments as carriers in RII and RIT (Olafsen et al., 2006). The smaller size of mAb improved the tumor penetration and delivery and decreased the exposure of non-targeted tissues by increasing the tumor-to-background ratio. However, widespread use of mAb fragments in RII and RIT has been limited by the reduced affinities of the mAb fragments and their renal reabsorption leading to renal toxicity or lower tumor uptake. Alternatively, a multistep targeting process had been proposed (Sharkey et al., 2012) in which the specificity and affinity of the mAb for the cancer target is retained, and the cytotoxic warhead is uncoupled from the mAb by appending it to a rapidly clearing carrier. Thus, the multistep strategy involves a “pretargeting” step, in which the slowly clearing intact mAb appended to a nontoxic adaptor molecule is administered first and allowed to reach the target. Later, a low molecular weight effector molecule with the radioactive payload is administered that specifically recognizes the adaptor on the mAb, which has already accumulated at the tumor site. Due to the rapid clearance of the small effector molecule, the uptake or exposure of normal tissue to the radionuclide is minimized and efficacy of RII and RIT is improved.

Several approaches to this multistep strategy have been introduced. For example, the high affinity of the streptavidin–biotin interaction was utilized by infusing a streptavidin-modified mAb followed by injection of radionuclides chelated to biotin (Karacay et al., 1997; Green et al., 2009). Bispecific antibodies with one antigen binding fragment (Fab) specific for the tumor antigens and the other Fab specific for a radio-metal chelate ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) have been developed (Goldenberg et al., 2007). Other methods use click chemistry in vivo to link the warhead to the mAb (Zeglis et al., 2011). Finally, pretargeting systems using RNA analogs are being used, which take advantage of natural self-assembly of oligonucleotide for crosslinking (Bos et al., 1994). Exploiting naturally occurring RNA–RNA hybridization to design a pretargeting system is attractive, but poor nuclease stability in plasma and a requirement for long oligomers (18–20 in length) limits its application in a clinical setting. However, recent advances in the design and the synthesis of unnatural RNA/DNA analogues with superior biochemical properties have allowed the application of oligonucleotides such as phosphothioate DNA (PS) oligomers (Villa et al., 2008), peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligomers (Rusckowski et al., 1997) and morpholino (MORFs) oligomers (Liu et al., 2002b) as pretargeting molecules. Nevertheless, PS oligomers show substantial nonspecific interactions with serum proteins, and PNA oligomers are also known to have poor aqueous solubility. MORFs show greater aqueous solubility; however, affinity is not substantially improved compared to their natural analogues. Thus, the design of MORFs is restricted to 22-mers or more. Longer oligomer strands show higher degree of inter- or intra-annealing.

Alternatively, oligomers based on locked nucleic acid (LNA) have been shown to be effective in shorter lengths compared to other counterparts. These oligomers are widely being used in antisense technology, DNAzymes, and decoy oligonucleotides and show a great potential to be used in pretargeting systems (Kaur et al., 2007; Moschos et al., 2011). LNA inherently shows excellent thermal stability, affinity, nuclease stability, and mismatch discrimination when hybridized with RNA or DNA. Similarly, 2′OMe RNA based oligonucleotides exhibit improved properties such as efficient hybridization, specificity and resistance to nuclease degradation, chemical stability, convenient synthesis, and minimal nonspecific interactions with nucleic acid binding proteins (Beijer et al., 1990; Iribarren et al., 1990; Lamond et al., 1990). Most of the new altered oligos used in this study were designed with modifications of 2′-oxygen moieties of the sugar backbone; these modifications improved the biochemical compatibility without compromising solubility and unique features of self-assembly.

Taking advantage of these unique properties, here we introduce a novel pretargetable cross-linking oligonucleotide system comprised of LNA and 2′OMe-RNA. Due to excellent thermodynamic properties exhibited by LNA, this novel duplex contains only 7 bases compared to >20 bases for morpholinos. The duplex shows fast hybridization, high melting temperatures, excellent affinity, and high nuclease stability in human plasma. Rapid whole body clearance was observed in vivo. Complementary LNA 7-mer can be orthogonally functionalized to allow multifunctional capabilities. Using a prototype model system with rituximab conjugated to 2′OMe-RNA-oligo, we demonstrated that radiolabeled LNA-based c-oligo effectively hybridize with rituximab–oligo circulating in live mice.

Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotide synthesis

Oligonucleotides (oligos) were synthesized using standard phosphoramidite chemistry (Fig. 1). Oligos possessing locked nucleic acid bases were synthesized using LNA phosphoramidites. The phosphoramidites and DNA synthesis reagents, except for locked nucleic acids, were obtained from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). Locked nucleic acids were obtained from Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark).

FIG. 1.

Design of oligo duplex. (A) Schematic representation of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2. c-oligo is comprised of (1) a Cy5, for in vitro/in vivo detection assays, (2) an internal amine moiety for the conjugation of chelating agents/drugs, (3) an LNA base platform, (4) a PEG unit for further nuclease stabilization, and (5) a disulfide moiety for conjugation of multifunctional groups. (B) Schematic representation of oligo-F1. The oligo is comprised of (1) an aldehyde group to conjugated to an antibody, (2) PEG units as a flexible linker between c-oligo and antibody, (3) a 2′O-Methyloligoribonucleotide (2′OMe) RNA base platform, and (4) a fluorescein for in vitro detection assays. R-oligo design is the same as the oligo-F1, except the platform sequence is comprised of c-oligo LNA bases. Cy5, cyanine 5; F1, fluorescein; LNA, locked nucleic acids; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Controlled-pore glass columns with fluorescein were used for 3′ fluorescein (fluorophore) modifications. For 5′ modifications in dabsyl (quencher)-containing sequences, dabsyl-dT, 5′-dimethoxytrityloxy-5-[(N-4′-carboxy-4-(dimethylamino)-azobenzene)-aminohexyl-3-acrylimido]-2′-deoxyuridine-3′-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite, was used. Oligo-fluorescein (F1)-CHO, c-oligo-Cy5-NH2, and r-oligo-Cy5-CHO were designed for both in vitro and in vivo experiments involving rituximab oligonucleotide conjugates. An aldehyde moiety was incorporated using 2-[4-(5,5-diethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)phenoxy]ethan-1-yl-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite in olgio-F1-CHO to conjugate to the rituximab using hydrazine-aldehyde chemistry. For c-oligo-Cy5-NH2, a 5′-dimethoxytrityl-5-[N-(trifluoroacetylaminohexyl)-3-acrylimido]-2′-deoxyuridine-3′-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite was introduced as an internal amine-dT to conjugate chelating agents, and 1-O-dimethoxytrityl-propyl-disulfide,-1′-succinyl-lcaa-CpG was used at the 3′ end to introduce disulfide group at the 3′ end for additional modifications. A C18 spacer, 18-O-dimethoxytritylhexaethyleneglycol,-1-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite, was used in all three sequences as a spacer between rituximab and the oligo to reduce steric hindrance effects and to protect from exonucleases. The completed oligo sequences were deprotected in concentrated ammonia at 55°C for 6 hours or according to the manufacture's recommendation for each modification. The resulting crude product was lyophilized and reconstituted in DNAse/RNAse-free water and purified by Sephadex™G-25 DNA-grade size exclusion chromatography (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The sample collected from the separation was lyophilized, reconstituted in 200 μL 80% acetic acid for 15 minutes, and incubated with 200 μL ethanol for 30 minutes for detritylation. The final product was vacuum- dried, reconstituted in ultrapure water, and quantified using ultraviolet–visible (UV-Vis) absorbance spectroscopy.

Instrumentation

An ABI3400 DNA/RNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) was used for target oligo synthesis. For the quantification of oligos, UV–Vis measurements were performed with a Cary Bio-100 UV spectrometer (Varian, Santa Clara, CA). Fluorescence measurements were performed on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrometer (Varian). Radiochemical quantifications were done on a Cobra II gamma counter (Packard, Santa Clara, CA). Flow cytometric analyses were done on a FacsCalibur 2002 (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Hybridization experiments using fluorescence resonance energy transfer

In order to characterize the biochemical properties of oligo (2′methoxy modified RNA: 5′mCmCmUmCmUmC-A-FAM-3′) and c-oligo (LNA: 5′-dabsyl-dT-+G+A+G+A+G+G-T-3′) duplex, the initial design consisted of a quencher on the c-oligo and a fluorophore on the oligo. We chose dabsyl-dT as the quencher and fluorescein as the fluorophore due to their well-overlapping spectral properties. Upon hybridization of oligo with c-oligo, the fluorescence of the oligo-F1 was quenched by dabsyl on the c-oligo, allowing the determination of the hybridization efficiency, affinity, thermal, and nuclease stability of the duplex in vitro.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assays were utilized to investigate the following parameters: (1) apparent affinity between c-oligo and oligo, (2) melting temperature, (3) nuclease stability, and (4) hybridization of c-oligo and oligo duplex. Hybridization of the duplex was also measured by first recording the fluorescence intensity of 1 μM of oligo-F1 for 10 minutes and addition of 5×molar excess of c-oligo-dabsyl into the cuvette. Flourecence quenching was recorded every minute. All FRET assays were performed with 500 μL of test reagent in a 500 μL quartz cuvette. Initial hybridization experiments were performed three different buffers of ascending stringency: (1) 10 mM Na2HPO4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA; (2) cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer; and (3) 4%–100% human serum with/without PBS, buffer to evaluate the duplex in vitro.

Apparent affinity between c-oligo and oligo

At room temperature, fluorescence of 10 nM of oligo-F1 in 4% human serum in PBS was analyzed with excitation at 497 nm and emission at 518 nm, and this value was used as the reference to provide the fluorescence of un-hybridized oligo-F1 fluorescence, which is equal to total hybridization sites in free solution. In a separate cuvette, serially diluted c-oligo-dabsyl was added into a 10 nM of oligo-F1-polyethylene glycol (PEG) in 1-nM, 5-nM, 10-nM, 25-nM, 50-nM, and 100-nM increments. The quenching of the fluorescence was measured as a function of concentration of c-oligo-dabsyl with simultaneous monitoring of total hybridization sites in a reference cuvette. The percentage of hybridization was calculated based on the degree of quenching as a function of the concentration of the quencher and plotted to calculate the relative affinity between the duplex.

|

|

Melting temperature of c-oligo and oligo duplex

The thermal stabilities of the oligo-F1 and c-oligo-dabsyl samples were determined by FRET assay. A 500 μL sample of oligo-F1 (50 nM) and 250 nM of c-oligo-dabsyl was incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes in PBS buffer supplemented with 4% human serum, and fluorescence intensity was recorded. Then the temperature was increased in 5°C increments with each step lasting for 1 minute to 95°C, and fluorescence intensity was monitored during each step. The melting temperatures (Tm values) were obtained as the maxima of the first derivative of the melting curves. Using similar conditions, a control experiment was carried out using oligo-F1 and r-oligo-dabsyl to investigate the nonspecific hybridization.

Nuclease stability of c-oligo and oligo duplex

To test the nuclease stability of oligo-F1 and c-oligo-dabsyl duplex, fresh human serum was chosen as the buffer media. The fluorescence of 1 μM of oligo-F1-PEG hybridized with 5 μM of c-oligo-dabsyl was incubated in fresh human serum and fluorescence intensity was measured as a function of time at 37°C for 1000 minutes, collecting fluorescence intensity measurement at every 2 seconds. We used 1 μM concentrations to avoid the high background generated by scattered light by highly abundant serum proteins.

Radiochemistry

One milligram of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 was first treated with 10-fold molar excess of EDTA to remove bivalent metals and buffer exchanged using P-10 column preequilibrated with buffer of 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate previously treated with Chelex 100 resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To this solution, added a 20-molar excess of amine reactive 2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA-SCN, Macrocyclics, Dallas, TX). This reaction was kept at room temperature for 2 hours, followed by purification, first on a Nap-5: Sephadex™ G-25 DNA-grade column preequilibrated with metal-free water to purify the product from the crude mixture then collect fractions from the size-exclusion column, then on a Sep-Pak C18 mini cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) previously washed with 20 mL of metal-free water. The product retained on the Sep-Pak C18 mini cartridge, which was visible due to Cy5 label, was eluted using a 50% ethanol in metal-free distilled H2O and lyophilized to give the solid c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA product. The solid product was redissolved in metal free water and quantified measuring wavelength λmax at 260 nm using UV–Vis spectroscopy. For each experiment, 100 μg of this product was radiolabeled with In-mCl3 (In-111) (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) by adding a 1-mCi radioisotope in an ammonium acetate buffer (1 M) at pH 5.5, for a period of 1 hour at 37°C. The labeling mixture was quenched by addition of 225 nmol of DTPA and purified on a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. Prior to elution of the product, the radiolabeled product, which was retained in the column, was first washed 4 times with water and 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate to ensure that all free DTPA-In-111 was removed. Radioactivity of the washes was counted to ensure complete elution of the free chelating agent. Then the product retained in the column was eluted into 50% ethanol in distilled water. Based on the radioactivity of the Sep-Pak column before and after product elution, the recovered product was about 90% of total retained activity. The product was evaporated under vacuum to yield c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 and specific activity was from ∼1–4 μCi/μg across all labeling. The radiochemical purity was measured by C18-silica thin-layer chromatography using mobile phases of 10 mM EDTA and 0.9% NaCl/10 mM NaOH. The scraped silica layers at the bottom and the solvent front were counted using a Cobra 2 gamma counter (Packard). Radiochemical purity was 70%–80% across repeated labeling reactions.

Conjugation of oligo-F1-PEG to rituximab

Aldehyde modified oligo-F1-CHO was conjugated to rituximab employing hydrazine-aldehyde conjugation chemistry. The pH of the rituximab (10 mg in PBS) solution was adjusted to 7.5 with 0.1 M NaHCO3. A 20-molar excess of succinimidyl-6-hydrazino-nicotinamide (S-HyNic, Solulink, San Diego, CA) was first dissolved in anhydrous dimethylformamide and added drop-wise to the rituximab solution. The mixture was reacted at room temperature for 2 hours to introduce hydrazine functionality at the primary amines of rituximab. The reaction mixture was purified using a 10DG-gel filtration column (BioRad, Hercules, CA) to remove unreacted S-HyNic. The hydrazone modified rituximab was eluted into 100 mM sodium citrate, 100 mM sodium chloride buffer, pH=5.5. The resulting S-HyNic modified rituximab was then reacted with 14× excess of aldehyde modified oligo-F1-CHO or r-oligo-F1-CHO at room temperature for 2 hours with gentle shaking. The un-reacted oligo-F1-CHO was removed by centrifugation using a 100,000 molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filter device, with four washings each of 5 mL of cold PBS at 4°C. The conjugated rituximab (rituximab-oligo-F1) concentration was quantified using detergent compatible protein assay (BioRad) using rituximab stock solution as the standard. The ratio of conjugated oligo-F1 to rituximab was quantified spectroscopically by observing the λmax at 488 nm for fluorescein on conjugated oligo and formed bis-aryl hydrazone chromophore (λmax=354 nm) resulted from the aldehyde-hydrazine conjugation. A similar procedure was used to conjugate rituximab and r-oligo-F1-CHO to yield rituximab-r-oligo-F1.

Cell binding assays

Avidity and in vitro assembly of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 with rituximab-oligo-F1

Serum blocked Ramos cells (5×105) were incubated with 50 nM rituximab-oligo-F1 and rituximab-r-oligo in 50 μL on ice for 1 hour in 2% human serum in cold PBS (binding buffer). At the end of 1 hour, unbound antibody was washed off with 1 mL ice cold binding buffer and 50 μL of serially diluted concentrations (from 500 nM to 5 nM) of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 was added into the cell palette and suspended to allow the hybridization of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 with rituximab-oligo-F1 bound to Ramos cells. This mixture was incubated at either 4°C or 37°C for 1 hour and unbound c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 was washed off. The hybridization of the c-oligos was detected by flow cytometry by counting 10,000 events for each concentration of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2. When calculating hybridization affinity, median fluorescence intensity was fitted to a nonlinear regression, and calculated Bmax/2 was used as the binding constant. Similar experiments were carried out in 100% human serum using 50 nM of rituximab-oligo-F1 to 50nM of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 to investigate the hybridization ability at the tumor site in vitro.

Biodistribution of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 in SCID mice

C-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 (3.45 μg) was injected via retro-orbital sinus into 12- to 16-week old female SCID/NCr Balb/cBk mice (NCI, Bethesda, MD). Three animals for each group were sacrificed at 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 hours. The biodistribution of the radiolabeled product was evaluated by detecting the radioactivity of blood, heart, kidney, lung, spleen, liver, stomach, intestine, muscle, and bone and % injected dose (ID) per gram was plotted. In a similar manner, biodistribution of preassembled rituximab-oligo-F1:c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was evaluated using time points of 3, 6, 24, and 48 hours. Prior to injection, rituximab-oligo was incubated with 5-molar excess of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 overnight in PBS buffer at 4°C. Unhybridized c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was removed by eluting the preassembled antibody on a 10DG column preequilibrated with 2% human serum in PBS buffer. Twenty-four micrograms of eluted preassembled rituximab-oligo-F1:c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 complex was injected via retro-orbital sinus. Organs were then harvested post-injection, and distribution of preassembled rituximab-oligo-F1:c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 were measured.

In vivo assembly of the duplex

In vivo hybridization of the duplex was monitored using SCID-female mice. Two groups of mice, with 3 animals per group, received 24 μg of either rituximab-oligo-F1 or rituximab-r-oligo-F1 intravenously (i.v.) via the right eye retro-orbital sinus. Then after 6 minutes, 3.45 μg of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was injected in the left eye retro-orbital sinus and allowed to circulate for, 3, 6, 24, and 48 hours. At each time point, animals were sacrificed and the biodistribution of assembled/free oligo was determined by harvesting organs as described above.

Results and Discussion

Design and characterization of oligos

We aimed to design a robust pretargeting system with physicochemical properties suitable for use in vivo, involving an oligonucleotide duplex that satisfies the following features: (1) thermal stability, (2) serum nuclease stability, (3) high affinity, (4) rapid hybridization between the two complementary strands, (5) minimum nonspecific interactions with serum proteins, and (6) rapid plasma clearance. We used 2 different types of nucleic acid bases: a complementary oligo (c-LNA, also known as the effector) comprised of LNA that is attached to the warhead or imaging agent, and a 2′OMe RNA (known as the target) to attach to the mAb that selectively binds the tumor. LNA molecules are a third generation of RNA mimicking nucleic acid derivatives in which the furanose ring of the ribose sugar is chemically locked with 2′-O,4′-C-methylene bridge (JESPER, 1999). Due to unique rigid conformation of LNA, these molecules have higher thermal and nuclease stability and high affinity towards its complementary strand. 2′-OMe RNA bases are a second generation of modified-version of RNA with a methoxy moiety at the 2′ position of the ribose sugar to improve nuclease stability against RNAse H and greater thermal stability than its natural counterpart.

The high affinity of LNA-LNA, can lead to inter-molecular (non-specific inter-strand annealing) and intra-molecular (self-annealing) interactions in fully modified LNA oligomers. In order to avoid such issues, we designed the c-oligo with LNA containing only purines. This design also aided in minimizing kidney accumulation in vivo, as cytocine incorporated oligo analogues are reported to show higher kidney accumulation (Fluiter et al., 2005). Prediction of sequence dependent hetero- and homo-dimer formation, as well as nonspecific folding was done with m-Fold software (ZUKER, 2003; Owczarzy et al., 2008). Based on m-Fold analysis and previous investigations pertaining to thermodynamic parameters of LNA-modified oligonucleotide sequences, a minimum of 7 nucleic acids of LNA was predicted to have the highest melting temperatures without hetero- or homo-dimer formation. These sequences were then evaluated experimentally (Fig. 1A). Extensive investigations suggested that substitution of a single LNA base with natural analogues substantially increases the melting temperature (Kaur et al., 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that a fully modified oligo duplex with LNA and 2′OMe would be characterized by superior thermodynamic and biochemical properties. In the final design, we also introduced a number of chemical modifications that provided multifunctional capabilities in preclinical applications: an aldehyde functionality was incorporated to conjugate with the hydrazine modified rituximab. Two PEG linkers were added to minimize steric effects that may hinder the efficient duplex formation upon hybridization with the c-oligo. Finally, a fluorescein molecule was added at 3′ end as a reporter molecule for biochemical investigations (Fig. 1B).

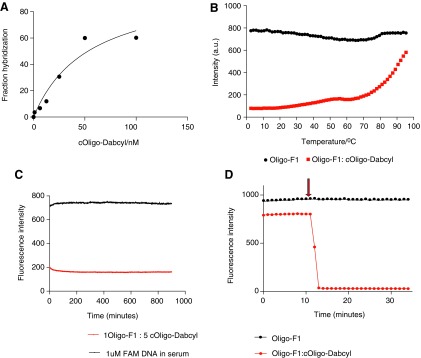

Apparent affinity between the c-oligo and oligo

The affinity of the oligo:c-oligo duplex was determined to be 54 nM using FRET (Fig. 2A). The observed high affinity of the oligo-F1 containing 2′OMe-RNA bases and c-oligo-dabsyl containing LNA bases was expected, based on the many reports highlighting the improved affinity of oligonucleotides derived on LNA towards its complementary strand. The high affinity hybridization is often attributed to the constrained sugar moiety and locked 3′endo conformation in LNA molecules. Furthermore, circular dichroism analysis of LNA:RNA duplexes show that they form expected A-type duplexes mimicking the natural structural features of an RNA duplex leading to improved stacking of the duplex, increasing the affinity (McTigue et al., 2004; Bhattacharyya et al., 2011).

FIG. 2.

In vitro characterization of the oligo duplex. (A) Binding of oligo-F1 to c-oligo-dabsyl. Affinity of the duplex was calculated to be 54 nM in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 4% human serum at 37°C. Serially diluted c-oligo-dabsyl was added into fixed concentration of 10 nM of oligo-F1 and the fluorescence quenching was observed. The fraction of hybridization was calculated according to equation 1 and plotted against the concentration of c-oligo-dabsyl. (B) Thermal profile of oligo-F1:c-oligo-dabsyl duplex in 4% human serum in PBS. (C) Nuclease stability profile of the duplex in 100% human serum at 37°C. (D) Hybridization of the oligo duplex at 37°C. Fluorescence intensity of oligo-F1was observed for 10 minutes in 4% human serum in PBS, and 5×molar excess of c-oligo-dabsyl was added at 10 minutes (indicated by the arrow). Due to hybridization of c-oligo-dabsyl, a dramatic reduction of fluorescence intensity of oligo-F1 was observed.

Determination of the melting temperature

A thermal denaturing profile of the duplex was recorded to evaluate the thermal stability of the duplex using FRET. In order to ensure complete hybridization of the duplex, c-oligo-dabsyl was used in 5×molar excess of oligo-F1. The fluorescence emission of oligo-F1 by itself and of the mixture of r-oligo-F1: c-oligo-dabsyl were constant during the thermal analysis, indicating that there was no significant fluorescence quenching with increasing temperature and no nonspecific interaction of c-oligo-dabsyl with oligo-F1 (Fig. 2B). The melting temperature was measured to be 88.72°C. The high thermal stability is related to high affinity of LNA bases towards its complementary strand, and due to the formation of stable duplexes leading to an increase in enthalpy or entropic change resulting from the restriction of the ribose and the preorganization of the single-stranded state.

Nuclease stability of c-oligo and oligo duplex

Recently, a number of unnatural analogues of nucleic acids have been introduced in antisense technology to reduce exo- and endo-nuclease sensitivity such as 2′OMe RNA bases and LNA bases. However, the extent of nuclease resistance in LNA bases is sequence dependent and not yet fully understood. The oligo duplex designed here showed complete nuclease stability for at least 17 hours in human serum at 37°C based on FRET (Fig. 2C). This resistance to nucleases can be explained by the combined effects of the 2′modification at the sugar moiety of the duplex due to the additional methyl moiety in the RNA bases as well as the restricted sugar moiety on the LNA bases. The restrained sugar moiety on LNA bases also changes the geometry of the phosphate backbone, which perturbs the interactions between the nucleases and the target duplex.

Hybridization of c-oligo and oligo duplex

The observed rapid hybridization of the duplex was correlated with high affinity of the duplex, which is related to on rate (Kon), and higher thermal stability (Fig. 2D). Upon addition of 5×molar excess of c-oligo-dabsyl, the duplex formation was instant, further confirming the potential of this duplex as a pretargeting molecule. Fast hybridization of the duplex is particularly important when pretargeting applications are planned, because the fast clearance of the small complementary strand will lead to rapid and substantial dilutions in vivo.

While a comparison study with a conventional construct consisting of DNA/RNA duplex would be an additional control, native DNA/RNA duplexes are not stable, and melting temperatures of conventional duplexes are not high (Koshkin et al., 1998). During the design of the novel duplex, we predicted the melting point of the same sequence with conventional bases using m-Fold software (ZUKER, 2003; Owczarzy et al., 2008); it was predicted to be <10°C. With this predicted melting point, we excluded this control complex as futile due to thermal instability.

Oligonucleotide conjugation to antibodies and characterization

Methods of conjugation of molecules to mAbs can be either random acylation of lysine ɛ-amino groups, alkylation of tyrosine groups, amidation of carboxylates, or regioselective modifications (Sun et al., 2005). Here, oligo-F1-CHO and r-oligo-F1-CHO (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/nat) were conjugated to rituximab and isotype control anti-CD3 antibodies (OKT3) via random acylation of lysine ɛ-amino groups by succinimidyl 6-hydrazinonicotinamide acetone hydrazine respectively. The modified mAbs were then reacted with aldehyde modified 2′OMe RNA to form a hydrazone linkage. One advantage of using this particular conjugation chemistry is that the hydrazone linker specifically absorbs at 350 nm, which allows the quantification of extent of conjugation by comparing the absorbance at 350 nm and 488 nm for fluorescein attached to oligo. Monoclonal antibodies conjugated to small molecules show variable biological properties based on the extent of modification; therefore, the ability to monitor the extent of conjugation is useful for proper quality control of the construct. We used 2 different controls to investigate duplex assembly in vitro: rituximab-r-oligo-F1 as a control for oligo and OKT3-oligo-F1 as a control of rituximab. This dual control system allowed the precise determination of in vitro biochemical parameters such as avidity of rituximab-oligo-F1 with c-oligo-F1 of the duplex. Using the ratio of absorbance of 350nm/488 nm, the extent of oligo conjugation to the antibodies was determined. With two different antibodies, the typical ratio of oligo to mAb was 5–10. Next we evaluated the Bmax/2 of both rituximab-oligo and OKT3-oligo to ensure the affinity of antibody was not affected by conjugation of the oligo (Supplementary Fig. 1). Affinities of both OKT3-oligo and rituximab-oligo were similar to the original antibody demonstrating that modification of each antibody did not interfere on its affinity towards the antigen.

In vitro assembly and avidity of c-oligo against oligo conjugated to antibodies

Avidity of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 with rituximab-oligo-F1 was investigated using respective cell lines in the presence of human serum both at 37 and 4°C. Dual detection of oligo conjugated to the antibody and c-oligo was facilitated by Cy5 signal originating from c-oligo-Cy5-NH2, and the fluorescein signal originating from the rituximab-oligo-F1 and rituximab-r-oligo-F1 conjugates. The avidity of c-oligo with rituximab-oligo was determined against the control rituximab-r-oligo using Ramos cells, in 2% human serum on ice. The avidity of c-oligo-Cy5-NH2 was calculated as 10 nM, demonstrating that the conjugation of the oligo to an antibody does not interfere with hybridization with its complementary sequence (Fig. 3A). This observation also confirms that the binding of the rituximab with its epitope on the cell is not altered upon hybridization of the c-oligo-Cy5-NH2. A reverse experiment was carried using c-oligo attached to OKT3 antibody, and sequence on the rituximab was as the c-oligo. The binding was evaluated against Jurkat cells. The avidity of this reverse system was calculated to be 17 nM, demonstrating that the retained avidity of oligo-duplex is generalizable to other antibodies (Fig. 3B). We investigated the ability of hybridization of the oligos in 100% human serum, using the same method with Ramos cells. Both OKT3 and rituximab attached to oligo showed a signal on the F1 channel due to fluorescein; therefore, the presence of rituximab on the cells is detectable. When c-oligo-Cy5 was added to the rituximab-oligo constructs already bound to Ramos cells, upon assembly of the duplex, Cy5 fluorescence becomes detectable in channel 4. The controls with rituximab-r-oligo-F1 and OKT3-Oligo-F1, show background fluorescence (Fig. 3C, middle panel) while, in vitro pretargeted cells show an increase in the fluorescence in channel 4, demonstrating that the hybridization is cell specific. Also, both rituximab-oligo-F1 and rituximab-r-oligo-F1specifically bound to Ramos cells in 100% human serum with c-oligo-Cy5 (Fig. 3C, right panel) showing oligo-conjugation to rituximab does not interfere with its binding and c-oligo-Cy5 hybridization does not change binding of rituximab-oligo-F1 with its antigen on Ramos cells.

FIG. 3.

In vitro assembly and avidity of c-oligo against oligo conjugated to antibodies. (A) Determination of avidity of c-oligo-Cy5 against rituximab-oligo-F1 using Ramos cells. (B) Determination of avidity of c-oligo-Cy5 against OKT3-oligo-F1 using Jurkat cells. (C) c-oligo-Cy5 hybridization on to the rituximab-oligo-F1 treated Ramos cells in the presence of 100% human serum: Left: The fluorescence shift of rituximab constructs on the x-axis compared with OKT3-oligo-F1 signal shows that both rituximab-oligo-F1 and rituximab-r-oligo-F1positively bind to Ramos cells. Middle: Rituximab-oligo construct bound to Ramos cells when c-oligo-Cy5 added; no change of the fluorescence signal in the F1 channel was observed, demonstrating that c-oligo-Cy5 hybridization does not affect antigen-antibody interaction. Right: Increase in the fluorescence shift for Cy5 of rituximab-oligo-F1 compared with rituximab-r-oligo-F1 shows the specific hybridization of c-oligo-Cy5 with rituximab-oligo-F1 bound to Ramos cells.

Radiochemical labeling of c-oligo

The chelating agent, DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraaza-cyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) is widely used as a chelating molecule in radioimmunotherapy applications due to its formation of stable chelating complex with the diagnostic and therapeutic radio-metals. We used DOTA as the chelating agent along with trace-labeled In-111 for biodistribution studies. The radiochemical yield for the reaction was in the range of 35% to 22% for multiple labelings. The recovery of the product preceeding the purification was ∼90%.

Biodistribution of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111

Biodistribution of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was investigated using female SCID/NCr Balb/cBk mice. We expected that c-oligo would show pharmacokinetic properties of a small molecule due to its smaller size. Within 6 hours, the blood level of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111- was 0.75±0.38 %ID/gram (Fig. 4A) confirming that the small c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 cleared rapidly. The distribution of the construct throughout the harvested organs was below 1% ID/g, demonstrating that c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 showed no non-specific organ accumulation. Interestingly, ∼16±3.7 %ID/gram of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 accumulated in kidney after 6 hours. The kidney accumulation of LNA based antisense oligonucleotides had been reported before (Fluiter et al., 2005). Renal secretion is the main route for oligonucleotides in general except PS oligonucleotides (Hnatowic and Nakamura, 2006). PS oligonucleotides non-specifically interact with serum protein, which leads to liver accumulation. In this study, fast renal clearance of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111, minimal nonspecific interaction with serum proteins and minimal accumulation in the liver or spleen demonstrates its suitability in pretargeting applications. Pharmacokinetics of fully modified LNA molecules and their kidney accumulation were not fully investigated and available literature is insufficient to discuss whether the observed uptake in the kidney is sequence specific. The backbone chemistry, composition of pyrimidines, and modification of sugar moiety, however, play a significant role in determining pharmacokinetics of oligonucleotides, respective organ accumulation, and the clearance route. For example, it has been reported that excessive kidney uptake of cytocine bases is responsible for kidney accumulation in MORFs (Liu et al., 2002a). This might not be the case for LNA as c-oligo does not contain pyrimidines; nevertheless, a systematic study using individual LNA base sequences will aid in clarifying observed accumulation of c-oligo in kidneys.

FIG. 4.

Biodistribution of studies in SCID mice. (A) Biodistribution of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111. (B) Biodistribution of preassembled complex of rituximab-oligo-F1:c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111. (C) Biodistribution profile of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 in SCID mice pre-injected with control rituximab-r-oligoF1. Rituximab-r-oligo-F1 injected via the left retroorbital sinus. After 6 minutes, c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was injected via the right retroorbital sinus. (D) Biodistribution profile of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 in mice preinjected with rituximab-oligo-F1. Rituximab-oligo-F1 was injected on the left orbital sinus. After 6 minutes, c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was injected on the right retroorbital sinus.

Biodistribution of rituximab-oligo-F1:c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111

Next, we investigated the biodistribution of the preassembled complex of rituximab-oligo:c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 (Fig. 4B). Prior to injection, a 1:5 molar ratio of the antibody was incubated with c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 in PBS at 4°C and unhybridized c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 was removed using size exclusion chromatography. In contrast to c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111, the preassembled complex showed high accumulation in spleen (9.2 2±1.68% ID/g); liver (30.56±4.07% ID/g); and kidney (36.19±4.92% ID/gram) at 48 hours post injection, a pharmacokinetic profile similar to that of an antibody. As the rituximab antibody does not bind specifically to any mouse antigens, that is, mouse CD20, accumulation of the antibody into tissues is driven by interactions with Fc receptors, primarily found on B-lymphocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, and macrophages, which are located largely in the sites of the reticuloendothelial system, such as liver, spleen, and bone marrow. In addition, due to fenestrated vascular endothelium of the spleen and liver, mAb distribution into these tissues is even higher. Due to their large size, the mechanism of elimination of mAbs is mainly catabolism following fluid-phase or receptor mediated endocytocis. Based on these typical antibody biodistributions, we expected that preassembled antibody complexes would localize partially in liver and spleen and the observed pharmacokinetic profile in Fig. 4B confirmed that prediction. Since, c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 is the tracer, the biodistribution results of the preassembled complex clearly demonstrated (1) prolonged circulation, (2) altered pharmacokinetic properties of c-oligo-DOTA-In-111, (3) the stability of the rituximab-oligo-F1:c-oligo-DOTA-In-111 construct up to 48 h.

In vivo assembly of rituximab-oligo with c-oligo-DOTA-In-111

We next investigated whether hybridization of the duplex could take place in vivo, a dynamic setting where rituximab-oligo and c-oligo-DOTA-In-111 are clearing slowly and rapidly, respectively. First, we injected 24 μg of rituximab-oligo in 100 μL of PBS i.v., and after 6 minutes we injected 3.45 μg of c-oligo-DOTA-In-111 i.v. As a control experiment, r-oligo conjugated rituximab was administered into a separate group of mice in a similar manner. Pharmacokinetic profiles showed that mice that received control rituximab-r-oligo-F1 had a pharmacokinetic profile for the labeled oligo similar to that of free oligos (compare Fig. 4C with Fig. 4A,) whereas, the rituximab-oligo capable of forming the duplex followed by c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 had a pharmokinetic profile similar to preassembled antibody (compare Fig. 4D with Fig. 4B). The similarity between the profiles in Figs. 4D and 4B confirms that the c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111 specifically hybridized with circulating antibody to yield the assembled complex in vivo.

Comparison of tissue deposition of respective constructs and controls confirmed the in vivo hybridization. Unhybridized c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In 3 cleared through the kidney (Fig. 4A), whereas upon specific hybridization to the antibody, it changed to liver deposition (Fig. 4D.) The control experiment in which the oligo cannot hybridize with rituximab-r-oligo, also showed the typical renal clearance of the c-oligo tracer. The observation of the clearance route of c-oligo-Cy-DOTA-In-111 changing from kidney (evidence of free oligo) to liver (evidence of binding to mAb) is proof that the hybridization reaction occurred rapidly in vivo. The low concentration of the injected c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111, due to low injection amounts, rapid dilution, and renal clearance, makes tissue extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography analyses impossible.

The animals used in these studies are immunocompromised; hence, immunogenicity of the agents would not be expected. However, single stranded RNA rich in uracil and guanine can activate Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7), a receptor that can instigate inflammation and could be immunogenic in healthy hosts. However, the minimal length reported for activation of the immune system was 21 nucleotides (Dalpke and Helm, 2012). Since the oligo designed in our study contains only 7 nucleotides and is guanine-free, we do not anticipate TLR7 activation. However, further investigations on immunogenicity of oligo sequence are necessary to confirm that this novel oligo duplex will not activate TLR7 or be recognized by other arms of the immune system.

Investigations of fully modified LNA-2′OMe RNA duplexes as pretargeting agents have not been explored before. This is partly due to the applications of unnatural oligomers primarily in antisense technology, not as pretargeting assemblies. Since assembly of the oligonucleotides can be predicted based on the sequence, by designing different sequences, multiple numbers of oligonucleotides can be used in controlled assembling for a desired outcome. So far, pretargeting application based on morpholino constructs with affinities of 10nM showed effective tumor localizations in a number of tumor models (Summerton and Weller, 1997; Liu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011). The novel duplex presented here, shows affinity of 54 nM and avidity of 10–17 nM, which could be effective in tumor pretargeting for imaging or therapy.

Conclusion

Here, we introduced a novel duplex that is applicable for crosslinking mAb to ligands for pretargeting based on LNA and 2′OMe. These LNA and 2′OMe-RNA duplexes showed increased nuclease and thermal stability, rapid hybridization, and strong affinity, features that allow the new constructs to be applied therapeutically or for imaging. Due to the high affinity towards its complementary oligo sequence, LNA based oligos have allowed the design of shorter sequences than previously used modified oligonucleotide duplexes. Shorter sequences are important for pretargeting applications because shorter sequences are unlikely to form secondary structures. Moreover, the feasibility of chemical modifications has allowed us to introduce PEGs, fluorophores, thiol, and amine modifiers on the c-oligo. These modifications will be useful for a variety of applications in vivo. As a proof of concept for this approach, we have successfully appended a 2′OMe-RNA molecule on rituximab without altering the affinity of the antibody, and then demonstrated that the affinity and the avidity of the crosslinking duplex in vitro in 100% human serum. Finally, we demonstrated that the novel duplex could hybridize in vivo, in mice. We plan next to explore the tumor targeting ability of this novel duplex. Achieving effective tumor targeting by use of 2-step methods is complicated and tedious due to the multiple variables involved, including finding: the optimal dosage of the rituximab-oligo, the optimal dosage of c-oligo-Cy5-DOTA-In-111, their ratio, the best time interval between the first and second steps, the clearance of unbound rituximab-oligo and the c-oligo. The optimization of each parameter is underway. The proposed duplex can also be applied as a tool to generate other macromolecular assemblies such as dimeric or multimeric small molecules, aptamers, mAb fragments, or peptides, to increase the avidity or to add multifunctionality and multivalency, or could be used in solid phase or chip assays as an addressable capture molecule.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Vitaly Kuryavyi of the Dinshaw Patel Lab, MSKCC for providing assistance with the DNA synthesizer. This work was supported by NIH R01 CA55349, NIH P01 33049, NIH R21 CA128406, and by a Lymphoma Research Foundation Research Fellow Grant, the Lymphoma Foundation, and the Tudor and Glades Funds.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- ADAIR J.R. HOWARD P.W. HARTLEY J.A. WILLIAMS D.G. CHESTER K.A. Antibody-drug conjugates: a perfect synergy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012;12:1191–1206. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.693473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEIJER B. SULSTON I. SPROAT B.S. RIDER P. LAMOND A.I. NEUNER P. Synthesis and applications of oligoribonucleotides with selected 2′-O-methylation using the 2′-O-[1-(2-fluorophenyl)-4-methoxypiperidin-4-yl] protecting group. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5143–551. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHATTACHARYYA J. MAITI S. MUHURI S. NAKANO S. MIYOSHI D. SUGIMOTO N. Effect of locked nucleic acid modifications on the thermal stability of noncanonical DNA structure. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7414–7425. doi: 10.1021/bi200477g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOS E.S. KUIJPERS W.H. MEESTERS-WINTERS M. PHAM D.T. DE HAAN A.S. VAN DOORNMALEN A.M. KASPERSEN F.M. VAN BOECKEL C.A. GOUGEON-BERTRAND F. In vitro evaluation of DNA-DNA hybridization as a two-step approach in radioimmunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3479–3486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOSWELL C.A. BRECHBIEL M.W. Development of radioimmunotherapeutic and diagnostic antibodies: an inside-out view. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34:757–778. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DALPKE A. HELM M. RNA mediated Toll-like receptor stimulation in health and disease. RNA Biol. 2012;9:828–942. doi: 10.4161/rna.20206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLUITER K. FRIEDEN M. VREIJLING J. ROSENBOHM C. DE WISSEL M.B. CHRISTENSEN S.M. KOCH T. ORUM H. BAAS F. On the in vitro and in vivo properties of four locked nucleic acid nucleotides incorporated into an anti-H-Ras antisense oligonucleotide. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1104–1109. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDENBERG D.M. CHATAL J.F. BARBET J. BOERMAN O. SHARKEY R.M. Cancer imaging and therapy with bispecific antibody pretargeting. Update. Cancer Ther. 2007;2:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.uct.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN D.J. PAGEL J.M. NEMECEK E.R. LIN Y. KENOYER A. PANTELIAS A. HAMLIN D.K. WILBUR D.S. FISHER D.R. RAJENDRAN J.G., et al. Pretargeting CD45 enhances the selective delivery of radiation to hematolymphoid tissues in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2009;114:1226–1235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HNATOWIC D.J. NAKAMURA K. The influence of chemical structure of DNA and other oligomer radiopharmaceuticals on tumor delivery. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2006;8:136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES B. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer: poised to deliver? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:665–667. doi: 10.1038/nrd3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRIBARREN A.M. SPROAT B.S. NEUNER P. SULSTON I. RYDER U. LAMOND A.I. 2′-O-alkyl oligoribonucleotides as antisense probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:7747–7751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JESPER W. Synthesis of 3′-C- and 4′-C-branched oligodeoxynucleotides and the development of locked nucleic Acid (LNA) Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- KARACAY H. SHARKEY R.M. GOVINDAN S.V. MCBRIDE W.J. GOLDENBERG D.M. HANSEN H.J. GRIFFITHS G.L. Development of a streptavidin-anti-carcinoembryonic antigen antibody, radiolabeled biotin pretargeting method for radioimmunotherapy of colorectal cancer. Reagent development. Bioconjug. Chem. 1997;8:585–594. doi: 10.1021/bc970102n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUR H. BABU B.R. MAITI S. Perspectives on chemistry and therapeutic applications of Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4672–4697. doi: 10.1021/cr050266u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOSHKIN A.A. NIELSEN P. MELDGAARD M. RAJWANSHI V.K. SINGH S.K. WENGEL J. LNA (Locked Nucleic Acid): An RNA Mimic Forming Exceedingly Stable LNA:LNA Duplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:13252–13253. [Google Scholar]

- LAMOND A.I. BARABINO S. BLENCOWE B.J. SPROAT B. RYDER U. Studying pre-mRNA splicing using antisense 2-OMe RNA oligonucleotides. Mol. Biol. Rep. 1990;14:201. doi: 10.1007/BF00360473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU G. DOU S. BAKER S. AKALIN A. CHENG D. CHEN L. RUSCKOWSKI M. HNATOWICH D.J. A preclinical 188Re tumor therapeutic investigation using MORF/cMORF pretargeting and an antiTAG-72 antibody CC49. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010;10:767–774. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.8.12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU G. DOU S. LIU Y. WANG Y. RUSCKOWSKI M. HNATOWICH D.J. 90Y labeled phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer for pretargeting radiotherapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011;22:2539–2545. doi: 10.1021/bc200366t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU G. HE J. ZHANG S. LIU C. RUSCKOWSKI M. HNATOWICH D.J. Cytosine residues influence kidney accumulations of 99mTc-labeled morpholino oligomers. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2002a;12:393–398. doi: 10.1089/108729002321082465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU G. MANG'ERA K. LIU N. GUPTA S. RUSCKOWSKI M. HNATOWICH D.J. Tumor pretargeting in mice using (99m)Tc-labeled morpholino, a DNA analog. J. Nucl. Med. 2002b;43:384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCTIGUE P.M. PETERSON R.J. KAHN J.D. Sequence-dependent thermodynamic parameters for locked nucleic acid (LNA)-DNA duplex formation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5388–5405. doi: 10.1021/bi035976d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOSCHOS S.A. FRICK M. TAYLOR B. TURNPENNY P. GRAVES H. SPINK K.G. BRADY K. LAMB D. COLLINS D. ROCKEL T.D., et al. Uptake, efficacy, and systemic distribution of naked, inhaled short interfering RNA (siRNA) and locked nucleic acid (LNA) antisense. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:2163–2168. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLAFSEN T. KENANOVA V.E. WU A.M. Tunable pharmacokinetics: modifying the in vivo half-life of antibodies by directed mutagenesis of the Fc fragment. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2048–2060. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OWCZARZY R. TATAUROV A.V. WU Y. MANTHEY J.A. MCQUISTEN K.A. ALMABRAZI H.G. PEDERSEN K.F. LIN Y. GARRETSON J. MCENTAGGART N.O., et al. IDT SciTools: a suite for analysis and design of nucleic acid oligomers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W163–W169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSCKOWSKI M. QU T. CHANG F. HNATOWICH D.J. Pretargeting using peptide nucleic acid. Cancer. 1997;80:2699–2705. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971215)80:12+<2699::aid-cncr48>3.3.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCOTT A.M. WOLCHOK J.D. OLD L.J. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:278–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARKEY R.M. CHANG C.H. ROSSI E.A. MCBRIDE W.J. GOLDENBERG D.M. Pretargeting: taking an alternate route for localizing radionuclides. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARKEY R.M. GOLDENBERG D.M. Cancer radioimmunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:349–370. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUMMERTON J. WELLER D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:187–195. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN M.M. BEAM K.S. CERVENY C.G. HAMBLETT K.J. BLACKMORE R.S. TORGOV M.Y. HANDLEY F.G. IHLE N.C. SENTER P.D. ALLEY S.C. Reduction-alkylation strategies for the modification of specific monoclonal antibody disulfides. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005;16:1282–1290. doi: 10.1021/bc050201y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLA C.H. MCDEVITT M.R. ESCORCIA F.E. REY D.A. BERGKVIST M. BATT C.A. SCHEINBERG D.A. Synthesis and biodistribution of oligonucleotide-functionalized, tumor-targetable carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4221–4228. doi: 10.1021/nl801878d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEGLIS B.M. MOHINDRA P. WEISSMANN G.I. DIVILOV V. HILDERBRAND S.A. WEISSLEDER R. LEWIS J.S. Modular strategy for the construction of radiometalated antibodies for positron emission tomography based on inverse electron demand Diels-Alder click chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011;22:2048–2059. doi: 10.1021/bc200288d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZUKER M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.