Abstract

Background and Purpose

We have shown that infusions of apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) mimetic peptide induced regression of aortic valve stenosis (AVS) in rabbits. This study aimed at determining the effects of ApoA-I mimetic therapy in mice with calcific or fibrotic AVS.

Experimental Approach

Apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice and mice with Werner progeria gene deletion (WrnΔhel/Δhel) received high-fat diets for 20 weeks. After developing AVS, mice were randomized to receive saline (placebo group) or ApoA-I mimetic peptide infusions (ApoA-I treated groups, 100 mg·kg−1 for ApoE−/− mice; 50 mg·kg−1 for Wrn mice), three times per week for 4 weeks. We evaluated effects on AVS using serial echocardiograms and valve histology.

Key Results

Aortic valve area (AVA) increased in both ApoE−/− and Wrn mice treated with the ApoA-I mimetic compared with placebo. Maximal sinus wall thickness was lower in ApoA-I treated ApoE−/− mice. The type I/III collagen ratio was lower in the sinus wall of ApoA-I treated ApoE−/− mice compared with placebo. Total collagen content was reduced in aortic valves of ApoA-I treated Wrn mice. Our 3D computer model and numerical simulations confirmed that the reduction in aortic root wall thickness resulted in improved AVA.

Conclusions and Implications

ApoA-I mimetic treatment reduced AVS by decreasing remodelling and fibrosis of the aortic root and valve in mice.

Keywords: HDL, fibrosis, collagen, aortic valve stenosis, mouse model

Introduction

Aortic valve stenosis (AVS) is the most prevalent valvular heart disease affecting the elderly in developed countries (Grimard and Larson, 2008; Carabello and Paulus, 2009). Severe AVS leads to considerable morbidity and death in less than 5 years if left untreated; therefore, open heart surgery and more recently percutaneous valve replacement are currently the primary therapeutic approaches. Medical treatments used to inhibit atherosclerosis, such as statins, have also been assessed for their beneficial effects in patients with AVS (Carabello and Paulus, 2009). Statins have been shown to be cardioprotective and to halt progression or induce regression of atherosclerosis (Nissen et al., 2006) but they do not prevent AVS progression (van der Linde et al., 2011; Salas et al., 2012). Although there are some similarities between AVS and atherosclerosis, their pathophysiology and treatments differ significantly. AVS is a complex inflammatory process involving infiltration of different cell types, including lymphocytes, macrophages and foam cells, endothelial activation and dysfunction, increased cellularity, extracellular matrix and lipoprotein deposition, as well as active leaflet calcification (Guerraty and Mohler, 2007; Rajamannan et al., 2011). Extracellular matrix remodelling, including collagen synthesis and elastin degradation by MMPs and cathepsins, contributes to leaflet stiffening. Severe AVS is associated with the presence of active mediators of calcification and cells with osteoblast-like activity within the valves (Guerraty and Mohler, 2007; Helske et al., 2007). The combination of these processes leads to valve thickening, varying degrees of calcification and impaired leaflet motion causing AVS (Freeman and Otto, 2005).

Some of the mechanisms underlying AVS development have been studied in apolipoprotein E (ApoE) and LDL receptor-deficient mice (Aikawa et al., 2007; 2009; Rajamannan, 2009; Hjortnaes et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2010; 2011). The aortic valves in these hypercholesterolemic mice are characterized by thickened leaflets, macrophage infiltration and the subsequent formation of calcific deposits in late stages, reproducing pathological features found in human valve disease. The ApoE knockout (ApoE−/−) mouse develops aortic valve and aortic root calcification, although only at a very old age or in combination with chronic uraemia (Tanaka et al., 2005; Aikawa et al., 2009). In the current study, we reasoned that administering vitamin D to ApoE−/− mice would accelerate the development of calcific AVS, as we had observed in the rabbit hypercholesterolemic and hypervitaminosis D AVS model (Drolet et al., 2003; Busseuil et al., 2008). Degenerative valve disease has also been associated with accelerated ageing-related syndromes like progeria or Werner (Wrn) syndrome (Makous et al., 1962; Rollé et al., 1997; Grubitzsch et al., 2000; Capell et al., 2007). Analysis of mice with a deletion in the helicase domain of the Wrn gene has shown that these animals develop severe cardiac interstitial fibrosis and signs of AVS (Lebel and Leder, 1998; Massip et al., 2006). We previously confirmed, using serial echocardiography and valve histology analysis, that WrnΔhel/Δhel mice fed with a high-fat/high-carbohydrate diet [the same diet previously used to trigger AVS development in other mice strains, including wild-type C57Bl/6J (Drolet et al., 2006)], develop mild AVS with no or minimal atherosclerosis (Trepeaux et al., unpublished data).

High-density lipoproteins (HDL) have anti-atherosclerotic properties through increased reverse cholesterol transport and anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and endothelial protection. Infusions of reconstituted HDL have been shown to induce rapid improvement of coronary atherosclerosis in patients (Nissen et al., 2003; Tardif et al., 2007), but their therapeutic effects have not yet been tested in AVS patients. Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), the main protein component of HDL, mediates many of its beneficial effects (Meyers and Kashyap, 2005; Tabet and Rye, 2009). Using a rabbit model of AVS, we have previously shown that infusions of an ApoA-I mimetic peptide complex lead to regression of experimental calcific AVS, with a 25% increase of aortic valve area (AVA), 21% decrease of aortic valve thickness, reduced extent of lesions at the base of valve leaflets and sinuses of Valsalva, as well as significant reduction in calcifications (Busseuil et al., 2008). A study using recombinant ApoA-I Milano in another rabbit model confirmed our findings of the potential benefits of HDL-based therapy for the treatment of AVS (Speidl et al., 2010).

In this study, we investigated the effects of an ApoA-I mimetic peptide on AVS progression in two fundamentally different murine AVS models, namely a hypercholesterolaemia calcific model in ApoE−/− mice and an accelerated ageing fibrotic model in WrnΔhel/Δhel mice.

Methods

Animals and experimental procedures

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and were approved by the institutional ethics committee for animal research. Studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 76 animals were used in the experiments described here.

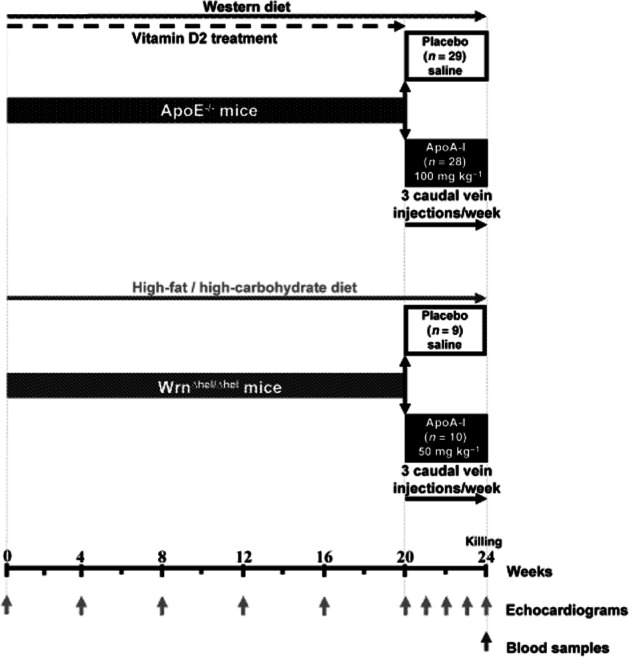

ApoE−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Fifty-seven ApoE−/− male mice (aged 8–9 weeks) were fed with a Western diet (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 24 weeks. They were randomly assigned to receive either saline (placebo group, n = 29) or the ApoA-I mimetic peptide (ApoA-I group, 100 mg·kg−1, n = 28) from week 20 to week 24 (Figure 1). To obtain calcified AVS in ApoE−/− mice, we added vitamin D2 (Sigma-Aldrich, ON, Canada) (at a concentration of 30 U·g−1 body weight per day during the first 20 weeks) in the drinking water, as in to our earlier work on the rabbit AVS vitamin D2 model (Drolet et al., 2003; Busseuil et al., 2008). Compared with our previous study, the doses of ApoA-I mimetic peptide were increased to compensate for a possible decrease in t1/2 in mice and/or also to take into consideration the higher HDL cholesterol levels normally observed in mice compared with rabbits. In the rabbit study, we terminated the cholesterol diet at the time of therapy initiation (Busseuil et al., 2008); however, in the current study, we continued the high-fat diet throughout the treatment period but doubled the duration of the treatment, and stopped the vitamin D2 supplementation in the drinking water. Moreover, given the higher total cholesterol levels in ApoE−/− mice, we also increased the dose of the ApoA-I peptide complex in this model compared with that used for WrnΔhel/Δhel mice.

Figure 1.

Experimental design using ApoE−/− and WrnΔhel/Δhel AVS mice models.

WrnΔhel/Δhel mice on a C57BL/6NHsd background were obtained from Dr Michel Lebel (CHUQ – Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, QC, Canada). Nineteen WrnΔhel/Δhel male mice (aged 13–15 weeks) were fed for 24 weeks with a high-fat/high-carbohydrate diet (Bioserv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA) which was previously used to induce AVS in wild-type C57BL/6J (Drolet et al., 2006). They were randomly assigned to receive either saline (placebo group, n = 9) or the ApoA-I mimetic peptide complex (ApoA-I group, 50 mg·kg−1, n = 10) from week 20 to week 24 (Figure 1). From week 20, we injected both strains of mice through the caudal vein, with either saline or ApoA-I mimetic peptide, three times per week for 4 weeks. We performed serial echocardiograms every 4 weeks from week 0 to week 20 (Supporting information Figure S1) and every week starting from week 20 throughout the randomized treatment period.

Animals were weighed at the time of every echocardiogram. Mice were killed 1 or 2 days after the last echocardiogram by cardiac puncture under anaesthesia using i.p. injection with ketamine (at 0.1 mg·g−1 body weight; Vetalar, Bioniche Animal Health Belleville, ON, Canada)/xylazine (0.2 mg·g−1 body weight; Rompun, Bayer HealthCare, Toronto, ON, Canada). Blood was collected and the heart and aorta were excised for further analyses. We measured total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and calcium levels from plasma with an automated filter photometer system (Dimension RxL Max; Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL, USA).

ApoA-I mimetic peptide complex

We used the ApoA-I mimetic peptide was synthesized as Polypeptide Laboratories (Torrance, CA, USA) as we previously described (Busseuil et al., 2008). Briefly, the peptide was complexed with egg sphingomyelin and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., Alabaster, AL, USA). In a 1:1:1 weight ratio by mixing the components in saline, fresh solutions were prepared as needed, under sterile conditions, and kept at 4°C for less than a week.

Echocardiography

Mice were sedated using isoflurane (2.5% in 500 mL of O2 min−1, Abbott Laboratories, Montreal, QC, Canada). Studies were carried out with an i13L probe (10 ∼14 Megahertz) on a Vivid 7 Dimension system (GE Healthcare Ultrasound, Horten, Vestfold, Norway). Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter was measured in a zoomed parasternal long-axis view, and LVOT cross-sectional area (CSALVOT) was calculated according to: CSALVOT = π (LVOT diameter/2)2. LVOT velocity (VLVOT) and velocity-time integral (VTILVOT) were obtained with pulsed-wave Doppler sampled proximally to the aortic valve in the apical five-chamber view. Continuous wave Doppler interrogation across the aortic valve was used to obtain transvalvular maximal velocity (VAV) and VTI (VTIAV) in the same view. VLVOT/VAV ratio was calculated to determine AVS development. AVA was obtained at each time point by the continuity equation and was equal to: CSALVOT × (VTILVOT/VTIAV) (Busseuil et al., 2008). The average of three consecutive cardiac cycles was used for each measurement. Special care was taken to obtain similar imaging planes on serial examinations. No angle correction was employed in flow acquisition as great effort was made to obtain optimal sampling parallel to flow in an apical view. All echocardiographic imaging and measurements were performed throughout the protocol by an experienced investigator unaware of the randomized treatment assignment.

Histology

After killing, the excised hearts were put in Neg-50 frozen section medium (Richard-Allan Scientific) and stored at −80°C. Cross-sections of the aortic valves were performed to obtain sinus wall and valve leaflets on the same section. Tissue sections were stained with Picrosirius Red, Alizarin red and haematoxylin phloxine saffron (HPS). For lipid infiltration analysis, tissue sections were fixed in formalin (10%) and stained with Oil Red O.

Immunohistochemistry

We used rabbit anti-mice antibodies against matrix metaloproteinase (MMP)2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; 1:1000 dilution), MMP9 (Abcam; 1:1000 dilution), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1; Abcam; 1:500 dilution), collagen I (Abcam; 1:1000 dilution) and collagen III (Abcam; 1:1000 dilution). These primary antibodies were followed by a goat antirabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody (Vector laboratories, Burlington, ON, Canada) at a dilution of 1:1000. They were revealed by Vectastain ABC-AP kit (Vector laboratories) with Vector blue alkaline phosphatase substrate kit III (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with Vector Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Laboratories). For WrnΔhel/Δhel mice, biotin-conjugated MMP9 antibody (Abcam; 1:10 dilution) followed by a horse anti-rat secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories; 1:200 dilution) was used for atherosclerosis-related histological study. Staining was revealed by Vectastain ABC kit (Vector laboratories) and peroxidase substrate kit AEC (Vector laboratories) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Images of aortic valve sections were taken at 10 × magnification with a computer-based digitizing image system using a light microscope BX41 (Olympus, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada) connected to a digital video camera Q-Color3 (Olympus) using Image Pro Plus version 7.0 (Mediacybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) for picture acquisitions and analysis. The percentage of antibody positive staining area in sinus wall, sinus plaque and valve leaflet was measured.

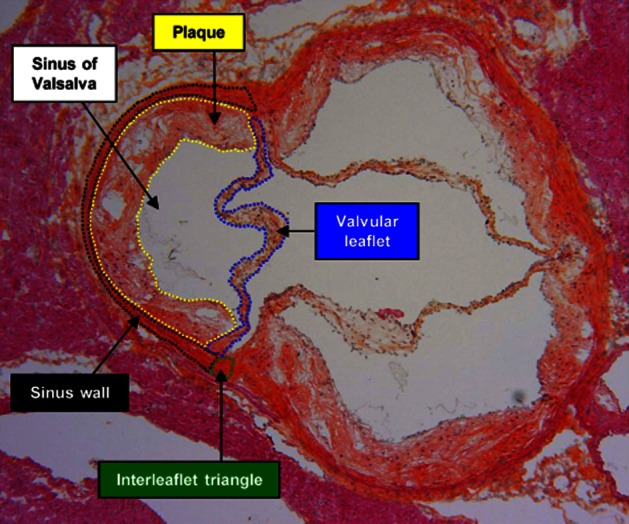

Histomorphometry

Thicknesses of leaflet and of sinus wall were measured with Image Pro Plus version 7.0 (Mediacybernetics). The term ‘valve’ in this analysis includes the components of the aortic root [sinuses of Valsalva wall (sinus wall), fibrous interleaflet triangles and valvular leaflets] and the plaques of the sinuses, if present (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic overlay showing the compartments analysed on aortic valve cross-sections (example of an ApoE−/− mouse valve). To simplify the reading of the diagram, the compartments are plotted on a single sigmoid.

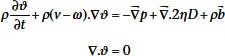

Three-dimensional modelling of the aortic root and valve

A geometrically corrected version of our previously published three-dimensional model of the aortic root and valve (Nobari et al., 2012) was used to simulate aortic valve dynamics in mice. Fluid–structure interaction (FSI) methodology is carried out in our simulations using the explicit finite element software LS-DYNA. Due to the FSI nature of our simulations, the model is comprised of two domains: the structural domain that represents the cardiac tissue and the fluid domain that represents the blood inside the cardiac tissue and the pericardial fluid outside of the cardiac tissue. The structural domain consists of the aortic root, valve leaflets/cusps, the aortic walls and a portion of the ascending aorta. The aortic wall includes the three sinuses of Valsalva, the attachment lines, the sinotubular junction and the two coronary ostia. The fluid domain includes an inlet to allow blood from the left ventricle to enter the aortic root, an outlet into the ascending aorta and the main fluid encompassing the entire cardiac tissue.

In order to calculate the desired variables such as velocity, pressure or displacement in the model, the dynamic equation that is solved in our explicit solution is generally of the following form:

| (1) |

where {F} is the total load matrix, {U} is the overall displacement matrix, [K] is the stiffness matrix, [C] is the damping matrix and [M] is the mass matrix. Assuming known values for velocity and displacement at a certain time step, Equation (1) results in the classic form of the relation between external forces and the acceleration of an object or Newton's second law of motion as shown in Equation (2).

| (2) |

Using the arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian differential form of the conservation equations for mass, momentum and energy, Equation (1) will result in the Navier–Stokes formulation for the fluid flow.

|

(3) |

where ρ is the density, D is the rate of deformation tensor, ν denotes the material velocity vector, (ν − ω) is the convective velocity, b is the specific body force and η is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid. The coupling between the fluid and the structure is obtained by applying a ‘no slip’ condition (νf − νs = 0) where νf and νs represent the fluid and the structure velocity, respectively, in the coupling interface. As for the material properties, blood is considered to be Newtonian with a density of 1060 kg·m−3 and a dynamic viscosity of 3.5 mPa.s.

We calculated the aortic elastic modulus E = (Ps − Pd)/[(Ds − Dd)/Dd] (Nemes et al., 2007) using systolic BP (Ps) and diastolic BP (Pd) values obtained using a Millar catheter from C57Bl/6 normal mice (mean of five animals, data not shown), and using systolic aortic diameter (Ds) and diastolic aortic diameter (Dd) values obtained by echocardiography from ApoE−/− mice at baseline of the present study. More detailed description of these boundary conditions and governing equations have previously been described (Nobari et al., 2009b; 2012). Linear elastic material properties are implemented to model the cardiac tissue with an elastic modulus of 1.25 and 1.85 MPa for the aortic root and valve leaflets, respectively, and a Poisson's ratio of 0.45 to account for the nearly incompressible behaviour of the tissue. Maximal thickness of the sinus wall values measured on histological sections of both placebo and ApoA-I-treated ApoE−/− mice were used in our simulations and the respective AVAs were then calculated using LS-prepost as our post-processing software.

Data analysis

For continuous variables, depending on the distribution of the data, results are expressed as mean ± SD or median (q1;q3). Repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were used to study AVA, weight and other echocardiographic parameters across time and between groups (placebo vs. ApoA-I), including a factor for group, time, group × time, centred baseline value of the response variable and centred baseline value × time. To observe changes over time, the adjusted means with 95% confidence intervals were presented in both groups at each time point. The group × time interaction was included in the ANCOVA model and was the main focus of the analysis as it tested the homogeneity of the pattern of change in the response variable between placebo and ApoA-I groups. In case of significant group × time interaction, various contrasts under the repeated ANCOVA model were conducted to explain the nature of the interaction (test of within-subjects time effect in each group and comparisons between groups at each time point). Otherwise, global conclusions were drawn based on the main time and group effects of the model. This was done on the diet period and treatment period separately. Single time point parameters were compared between placebo and treated groups using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney test if distributional assumptions were not met. The relationship between AVA change and total collagen was investigated over all groups using Pearson's r. All analyses were done with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and conducted at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Initial development of AVS in ApoE−/− and WrnΔhel/Δhel mice

To monitor the changes in aortic valve function in both murine models, we assessed the progressive development of AVS by serial echocardiography during the first 20 weeks (Figure 1 and Supporting information Figure S1). The individual parameters utilized to calculate AVA values for ApoE−/− and WrnΔhel/Δhel mice are presented in the Supporting information Table S1. A significant decrease of AVA was observed at week 20 compared with week 0 in both models: (median with q1-q3) 0.595 (0.583–0.606) mm2 versus 0.698 (0.687–0.709) mm2 (corresponding to a decrease of approximately 15% from pooled placebo and treated group data) for ApoE−/− mice and 0.691 (0.672–0.710) mm2 versus 0.757 (0.738–0.776) mm2 (decrease of approximately 9%) for WrnΔhel/Δhel mice (P < 0.0001 for both models). There was no difference in AVA among mice randomized to placebo and ApoA-I groups during this AVS development period up to 20 weeks, prior to randomized therapy (P = 0.309 for ApoE−/− mice; P = 0.549 for WrnΔhel/Δhel mice).

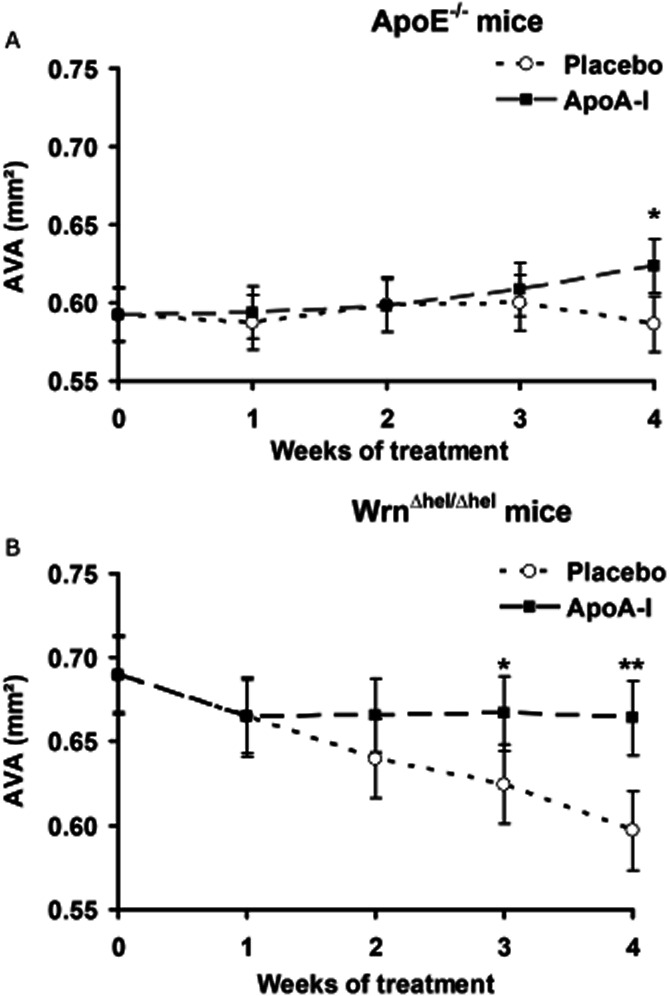

Benefits of ApoA-I treatment on AVA

We assessed the effect of ApoA-I treatment on AVA in both models by serial echocardiographic measurements. In ApoE−/− mice, the pattern of change of AVA over time during the 4 week ApoA-I-treatment period was different between the placebo and treated groups (P = 0.035, Figure 3A). A significant increase of AVA was observed in the ApoA-I treated group (P = 0.043), whereas AVA remained unchanged during the treatment period in the placebo group (P = 0.244). AVA was significantly higher in the ApoA-I group compared with controls after 4 weeks of treatment (P = 0.0039), corresponding approximately in the treated group to the recovery of 30% of the AVA lost during the AVS development period (from week 0 to week 20).

Figure 3.

Echocardiographic measurements of aortic valve area (AVA) during the apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) mimetic peptide treatment period for ApoE−/− mice (A) and WrnΔhel/Δhel mice (B). Day 0 corresponds to the beginning of treatment.. *P < 0.02; **P < 0.001.

We also found the AVA changes to be significant during the treatment period in WrnΔhel/Δhel mice (P = 0.012, Figure 3B). The comparison between the 2 groups during the treatment period revealed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.0001). We observed a significant reduction of approximately 13% of AVA in the placebo group during the treatment period. By contrast, AVA remained stable in ApoA-I-treated WrnΔhel/Δhel mice from week 1 to week 4 (week 1 compared with weeks 2, 3 and 4; all P = ns). The gradual decrease observed in control (placebo-treated) animals resulted in the AVA being significantly higher with ApoA-I compared with placebo at week 3 (P = 0.0158) and week 4 (P = 0.0002). Similar results were obtained for both models after indexing of AVA data to body weight (Supporting information Figure S2).

The lipid profiles of ApoE−/− and WrnΔhel/Δhel mice were measured at the end of treatment (Table 1). As expected by differences in their genetic background, the high-fat diet resulted in HDL-cholesterol increase in WrnΔhel/Δhel mice compared with ApoE−/− mice. However, there were no significant differences between corresponding placebo and treated groups for total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides. Plasma calcium levels were significantly higher in ApoE−/− ApoA-I-treated mice compared with the ApoE−/− placebo-treated mice. Although similar findings were observed in the WrnΔhel/Δhel ApoA-I-treated group compared with the corresponding placebo group, the difference was not significant for this model.

Table 1.

Plasma profiles of placebo and ApoA-I mimetic peptide-treated mice at the end of the treatment period

| Total cholesterol (mM) | HDL-cholesterol (mM) | Triglycerides (mM) | Calcium (mM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− mice | ApoA-I (n = 18) | 6.4 ± 1.4 | 0.45 ± 0.18 | 0.78 ± 0.29 | 2.45 ± 0.21 |

| Placebo (n = 14) | 7.2 ± 3.3 | 0.54 ± 0.37 | 0.91 ± 0.41 | 2.30 ± 0.14 | |

| P | 0.437 | 0.391 | 0.321 | 0.024 | |

| WrnΔhel/Δhel mice | ApoA-I (n = 10) | 5.0 ± 1.4 | 1.57 ± 0.61 | 0.53 ± 0.33 | 2.39 ± 0.24 |

| Placebo (n = 8) | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 1.86 ± 0.29 | 0.56 ± 0.37 | 2.24 ± 0.09 | |

| P | 0.683 | 0.229 | 0.865 | 0.095 |

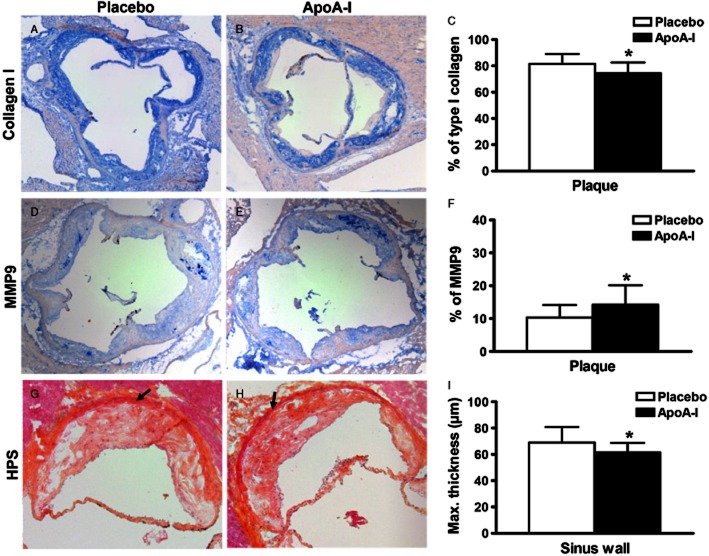

Reduced collagen type I and increased MMP9 in ApoA-I-treated ApoE−/− mice

To understand how ApoA-I therapy might exert its beneficial effects on aortic valve function, we measured different histological markers of calcification, lipid infiltration and fibrosis. ApoE−/− mice developed atheromatous plaques in the sinuses of Valsalva and showed fibrous thickening of the aortic valve leaflets. We observed both calcification (detected by Alizarin red staining) and lipid infiltrations (Oil red O staining), albeit without any significant differences between placebo and ApoA-I treated mice (Table 2). To evaluate tissue fibrosis, we quantified the levels of collagen by immunohistochemistry and found a significantly lower content of type I collagen in the plaques of the sinuses from aortic valves of ApoA-I-treated mice compared with those of placebo mice (P = 0.011) (Figure 4A–C). Differences in the type I collagen content were also observed in the sinus wall (17.1 ± 5.1 vs. 23.4 ± 12.4%, P = 0.058). We also measured the type I/type III collagen ratio and found this ratio in the sinus wall to be lower in ApoA-I-treated mice compared with placebo [1.16 (0.86;9.50) vs. 1.80 (0.72;4.16), P = 0.020]; there was no significant difference in that ratio in the plaques between ApoA-I- and placebo-treated mice (1.37 ± 0.22 vs. 1.52 ± 0.26, P = 0.084).

Table 2.

Quantification of tissue calcification and lipid infiltration in aortic valves from placebo and ApoA-I mimetic peptide-treated mice

| % of tissue calcification | % of lipid infiltration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− mice | ApoA-I (n = 23) | 31 ± 12a | 28 ± 25a |

| Placebo (n = 19) | 27 ± 8a | 22 ± 17a | |

| P | 0.201 | 0.425 | |

| WrnΔhel/Δhel mice | ApoA-I (n = 6) | None | 2.7 ± 2.2b |

| Placebo (n = 6) | None | 3.0 ± 1.6b | |

| P | – | 0.839 |

In valvular plaques.

In commissures.

Figure 4.

Immunostaining analysis of aortic valves (A–F) and histomorphometric analysis of the sinus wall (G–I) from ApoE−/− mice following apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) mimetic peptide or control treatment. Cross-sections (10 × magnification) were immunolabelled using (A, B) type I collagen and (D, E) MMP9 antibodies. (C) Percentage of type I collagen and (F) MMP9 staining in the plaque areas in both treatment groups. Type I collagen and MMP9 labelling were stained with Vector blue (Fast Red counterstained), *P < 0.05. (G, H) Photomicrographs of one sigmoid from HPS-stained aortic valve sections used for sinus wall (arrows) thickness measurement (10 × magnification). (I) Maximum thickness of sinus wall (mean of the 3 sigmoids), *P < 0.05.

To further assess tissue remodelling, we quantified MMP9 by immunodetection (Figure 4D and E) and found a higher percentage of area occupied by MMP9 staining in the plaques of the sinuses of ApoA-I treated compared with placebo-treated mice (P = 0.042) (Figure 4F). We also observed a numerical increase of the median percentage of MMP9 staining in the sinus wall of ApoA-I-treated mice compared with placebo mice, which did not reach statistical significance [1.27 (0.17–7.25)% vs. 0.77 (0.07–5.13)%, P = 0.319]. By contrast, we did not observe any significant differences between the placebo and ApoA-I-treated groups for MMP2 or for TIMP-1 labelling in the plaques of the sinuses or in the sinus wall (data not shown). To further investigate the type I collagen differences observed in plaques and sinus wall between the two groups, we performed histomorphometric analyses. We found that the average maximal thickness of the sinus wall from the three sigmoids was lower in ApoA-I-treated mice compared with placebo-treated mice (P = 0.016, Figure 4G–I).

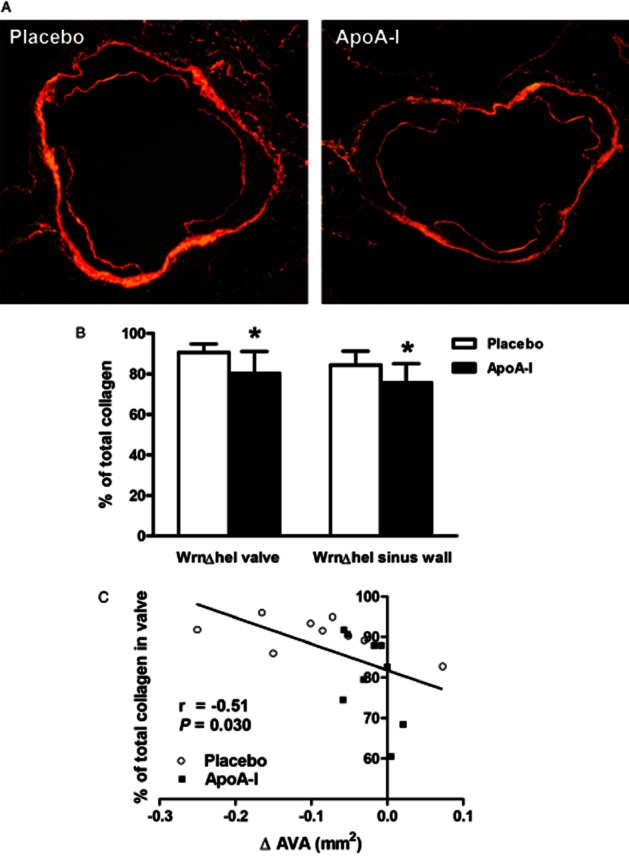

Reduced total collagen in ApoA-I-treated WrnΔhel/Δhel mice

We did not detect any atheromatous plaques in the aortic valves of the WrnΔhel/Δhel mice. In contrast to the ApoE−/− mice, we did not detect any signs of calcification by Alizarin red staining in the WrnΔhel/Δhel animals. Given the lack of calcification, we did not measure any osteogenic specific proteins. We observed minor lipid infiltrations (Oil red O staining) albeit with no difference among groups (Table 2). Collagen content in the valve, as evaluated by Sirius red staining (Figure 5A), was lower in ApoA-I-treated mice compared with placebo-treated (P = 0.023, Figure 5B). A similar finding was obtained when analysing staining in the sinus wall only (P = 0.039, Figure 5B). To strengthen these observations, we correlated AVA (measured by echocardiography) with % total collagen content (measured by histological analysis). We found a negative correlation between the % total collagen content in the valve and the change of AVA during treatment time in pooled WrnΔhel/Δhel mice (n = 18, Figure 5C). We did not find any significant differences between the two groups for collagen I and MMP9 labelling in the sinus wall (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Collagen content analysis of aortic valve sections from WrnΔhel/Δhel mice. (A) Picrosirius Red staining of placebo (left) and apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) mice (right) (4 × magnification); (B) percentage of collagen content in the entire valve and in the sinus wall; (C) correlation between the change in aortic valve area (AVA) during the treatment period as assessed by echocardiography and the % of total collagen in the entire valve from pooled placebo and ApoA-I treated mice. *P < 0.05. ApoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide-treated group.

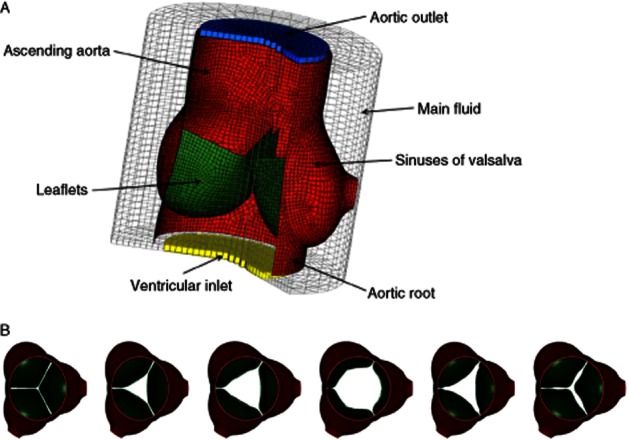

Three-dimensional modelling of the aortic root and valve in ApoE−/− mice

Finally, given that the average maximal thickness of the sinus wall from the three sigmoids was lower in ApoA-I-treated mice compared with placebo-treated mice (Figure 4G–I), we wanted to investigate whether such a change in the sinus wall thickness could affect the effective AVA and, thereby, account for the improved AVA observed with echocardiography following ApoA-I treatment. To address this issue, we used a corrected version of our published 3D model of a human aortic valve to simulate a mouse aortic valve (Nobari et al., 2012) and performed FSI simulations of the aortic root region and valve leaflets (see Figure 6A for a cut view of the FSI model of the aortic valve and Figure 6B for the opening and closing patterns of the aortic valve during one cardiac cycle using this 3D model). We performed two sets of simulations based on histological measurements of maximal thickness of sinus walls from placebo- and ApoA-I-treated mice. Similar AVA values were obtained from our simulations when compared with the echocardiographic measurements. The qualitative results in terms of global leaflet tip movement and the triangular valve orifice were similar to our previous studies and to what is observed in pulse duplicator for humans. We calculated the maximum AVA (geometric orifice area) based on the opening and closing dynamics of the valve obtained for placebo- and ApoA-I-treated mice. We have also taken into account the maximal thickness value of the sinus wall measured on histological sections for both placebo (69.1 μm) and ApoA-I-treated (61.5 μm) ApoE−/− mice. Using our numerical simulations, we found the AVA values from ApoE−/− mice to be similar to the values obtained through the echocardiography analysis (Table 3). Importantly, the difference between AVA values obtained with echocardiography between the treated groups was similar to that obtained through the numerical simulation. These findings indicate that the changes in sinus wall thickness induced by ApoA-I therapy could explain the beneficial changes in AVA observed following treatment.

Figure 6.

Cut views of the fluid structure interaction model of (A) the aortic root and (B) the opening and closing patterns of the aortic valve during a cardiac cycle in ApoE−/− mice using 3D modelling.

Table 3.

Aortic valve area (AVA) values obtained with echocardiography and calculated from numerical simulations

| Sinus wall thickness measured on histological sections (μm) | AVA obtained with echocardiography | AVA calculated from numerical simulations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 69.1 | 0.587 mm2 | 0.572 mm2 |

| ApoA-I mimetic | 61.5 | 0.624 mm2 | 0.609 mm2 |

| Percent difference | – | 6.30% | 6.34% |

Discussion

We have shown in this study that treatment with an ApoA-I mimetic peptide complex leads to significant improvement of AVS developed in two different AVS murine models: ApoE−/− mice, a dyslipidaemia-related model, and WrnΔhel/Δhel mice, an ageing fibrosis-related model that develops early-stage AVS without significant atherosclerosis. Compared with placebo, ApoA-I mimetic peptide infusions resulted in improved AVA in both the ApoE−/− and the WrnΔhel/Δhel mice. Our histological findings in these AVS models and the 3D modelling provide new evidence that the beneficial effects of an ApoA-I mimetic peptide are associated with reduced remodelling of the aortic root and valve.

In ApoE−/− mice, ApoA-I treatment increases AVA, decreases the maximal thickness of sinus wall and alters the collagen content in valves

Histological examination revealed atheromatous lesions both in the leaflets and Valsalva sinuses and calcium deposition. During treatment, the significant AVA increase in the treated group and lack thereof in the placebo group demonstrates the beneficial effects of the ApoA-I mimetic peptide on this calcific AVS hypercholesterolemic murine model. These findings extend the beneficial effects of ApoA-I therapy observed in a hypercholesterolaemia-induced calcific AVS rabbit model (Busseuil et al., 2008). Histological analysis in the AVS rabbit model revealed that the ApoA-I treatment led to decreased lesions at the base of valve leaflets and sinuses of Valsalva and reduced calcification. In the current study, we chose to perform cross-sections of tissues instead of longitudinal sections, as performed in our previous rabbit study (Busseuil et al., 2008), mainly due to the small size of the mouse valve. We report a reduction of maximal thickness of the sinus wall with ApoA-I mimetic peptide therapy, which can be explained, at least in part, by changes in fibrosis.

We found a small but significant increase in MMP9 expression following ApoA-I treatment in the valvular plaques of ApoE−/− mice. Although an increase in MMP9 expression has sometimes been regarded as a sign of plaque instability (Loftus et al., 2000) or of increased inflammation in AVS (Fondard et al., 2005), studies in ApoE/MMP9 double knockout mice have suggested that MMP9 could slow plaque expansion and increase plaque stability (Johnson et al., 2005). It has also been suggested that MMP9 is associated with smooth muscle cell migration and repair processes (Galis et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2005) and that it is not only involved in plaque rupture. For example, MMP9 was shown to modify geometrical arterial remodelling, which allows preservation of lumen size in a carotid artery model (Galis et al., 2002). On the other hand, it is possible that the changes observed in MMP9 expression are the consequence of haemodynamic alterations (Nichol et al., 2009) caused by other mechanisms affected by the ApoA-I treatment.

To further assess fibrosis and remodelling, we evaluated the ratio of type I/type III collagen as it has been shown that an increase of the type I/type III collagen ratio might affect cardiac rigidity and may decrease cardiac compliance; type I collagen has been shown to contribute to rigidity whereas type III collagen contributes to elasticity (Marijianowski et al., 1995; Pauschinger et al., 1999). In our study, ApoA-I treatment decreased type I collagen content in ApoE−/− mice's plaques and decreased the type I/type III collagen ratio in the sinus wall, which suggests decreased rigidity of the aortic valve, sinuses and related structures in ApoA-I-treated mice. In agreement with these findings, the benefits of ApoA-I therapy have also been reported for pulmonary fibrosis (Kim et al., 2010).

The proposal that reduction of maximal thickness of the sinus wall with ApoA-I mimetic peptide therapy resulted in improved AVA was supported by the results of FSI simulations in the aortic root region. These results suggest that favourable changes in the aortic sinuses (induced by ApoA-I therapy) could at least, in part, lead to an improvement in AVA. Although thickening of aortic root structures is not recognized as a major cause of AVS, aortic root compliance is crucial for normal valve function and it is possible that loss of compliance of this structure leads to fibro-calcification of the leaflets (Fokin et al., 2004; Sripathi et al., 2004).

In WrnΔhel/Δhel mice, ApoA-I therapy improves AVA and decreases valve collagen content

To determine whether ApoA-I treatment favourably affects AVS in a model not related to atherosclerosis and underlying dyslipidaemia, we used the WrnΔhel/Δhel ageing model. To accelerate the development of AVS in this model, which was previously observed in 1-year-old mice (Massip et al., 2006), we chose to use the same high-fat/high-carbohydrate diet that was shown to successfully induce AVS in wild-type mice (Drolet et al., 2006). To our knowledge, this is the first example of a progeria-related AVS model being used to test an HDL-based therapy. Although the WrnΔhel/Δhel mouse model showed mild AVS, typical accelerated ageing-related fibrogenesis, no calcifications and very little signs of atherosclerosis, ApoA-I mimetic peptide treatment efficiently halted the progressive decrease in AVA observed in placebo-treated mice. ApoA-I treatment resulted in reduced total collagen content in the aortic valve and sinus wall, and the change in AVA during the treatment period correlated inversely with the percentage of total collagen in the valve, further indicating the importance of decreased fibrosis on valvular function improvement. This is consistent with previous mouse studies showing that cusps from diseased valves were thickened with increased collagen content (Hinton et al., 2006). A decrease in total collagen content should lead to a decrease in tissue stiffness. In contrast to our results with the ApoE knockout mouse model, we did not observe any change of MMP9 expression by immunohistochemistry in the WrnΔhel/Δhel. Using modelling simulations, we have previously shown that a decrease in tissue stiffness could lead to an AVA increase in a human model (Nobari et al., 2009a). We propose that decreased stiffness of the aortic valve would result in increased AVA also in the mouse model, which could explain the improvement in AVA observed with echocardiography in the WrnΔhel/Δhel mice.

One of the most notable differences between atherosclerosis-related fibrosis and ageing-related fibrosis is the relative absence of macrophages in the normal ageing process. We observed very few Ly-6c+ monocytes and no F4/80+ macrophages using immunohistochemical analysis of the aortic root from WrnΔhel/Δhel AVS mice (data not shown). This indicates that the therapeutic action of the ApoA-I mimetic peptide on the aortic valve is not mediated by effects on macrophages in this model but rather that ApoA-I targets other cell types, most likely valvular myofibroblasts. In agreement with these findings, Lommi et al. (2011) recently showed that the concentration of ApoA-I was higher in control than in stenotic valves and that ApoA-I staining did not colocalize with inflammatory cell infiltrates.

Study limitations

Although mouse models do not fully reproduce the human disease, they do provide valuable tools to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of ApoA-I therapy in AVS. In humans, AVS is often associated with massive fibro-calcification of the aortic valve leaflets. Although we did not observe the same severity of such pathological signs in our models, we believe that we are most likely dealing with early phases of AVS development. The use of different AVS models (a hypercholesterolemic calcific mouse model and an accelerated ageing fibrotic mouse model) will help us to improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the benefits of HDL-based therapy.

In conclusion, infusions of an ApoA-I mimetic peptide lead to significant improvement of AVS and reduced remodelling and fibrosis of the aortic root and/or valve both in the ApoE−/− dyslipidemic and calcific mouse model and in WrnΔhel/Δhel mice which provide an accelerated ageing, pro-fibrotic but non-calcific and non-atherosclerotic model. Given the morbidity and mortality associated with this most prevalent form of valvular disease, HDL-based therapies should be tested in patients with AVS.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the statistical analysis by Malorie Chabot-Blanchet, MSc, Marieve Cossette, MSc, Daniel Cournoyer, MSc and Marie-Claude Guertin, PhD, at the Montreal Heart Institute Coordinating Center. Special thanks to Ekat Kritikou, PhD, for scientific review and editing of the current manuscript.

This work was supported by Canada Research Chair (tier 1) in translational and personalized medicine. J. C. T. holds the Canada Research Chair in translational and personalized medicine and the Université de Montréal research chair in atherosclerosis.

Glossary

- AVS

aortic valve stenosis

- ApoA

apolipoprotein A

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- AVA

aortic valve area

- CSALVOT

LVOT cross-sectional area

- FSI

fluid–structure interaction

- LVOT

left ventricular outflow tract

- TIMP-1

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1

- VAV

transvalvular maximal velocity

- VLVOT

LVOT velocity

- VTILVOT

velocity-time integral

- Wrn

WrnΔhel/Δhel

Conflicts of interest

A patent on the theme of HDL and aortic valve stenosis was submitted by the Montreal Heart Institute and Dr. Tardif is mentioned as an author.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Aortic valve area (AVA) values obtained by echocardiography during the AVS development period. Comparison between placebo group and ApoA-I mimetic peptide-infused group for a) ApoE−/− mice and b) WrnΔhel/Δhel mice.

Figure S2 Aortic valve area indexed to body weight (AVAi) adjusted values obtained by echocardiography and reported on body weight during the randomized treatment period. Comparison between placebo and ApoA-I groups for a) ApoE−/− mice and b) WrnΔhel/Δhel mice; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P ≤ 0.0001. ApoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide.

Table S1 Main individual echocardiographic parameters measured to characterise aortic valve stenosis. Adjusted means for the high-fat diet period and for the treatment period came from two separate statistical analyses: from baseline to 20 weeks of high-fat diet for (a) ApoE−/− mice and (c) WrnΔhel/Δhel mice; from 20 weeks of high fat to the end of treatment period for (b) ApoE−/− mice and (d) WrnΔhel/Δhel mice. LVOT: Left ventricular outflow tract. VTI: Velocity time integral. In case of significant group x time interaction, the comparison between groups under the repeated ANCOVA model was conducted at the last time point presented in the table (P-value).

References

- Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik D, Lok VM, Jaffer FA, Aikawa M, et al. Multimodality molecular imaging identifies proteolytic and osteogenic activities in early aortic valve disease. Circulation. 2007;115:377–386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.654913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa E, Aikawa M, Libby P, Figueiredo JL, Rusanescu G, Iwamoto Y, et al. Arterial and aortic valve calcification abolished by elastolytic cathepsin S deficiency in chronic renal disease. Circulation. 2009;119:1785–1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busseuil D, Shi Y, Mecteau M, Brand G, Kernaleguen AE, Thorin E, et al. Regression of aortic valve stenosis by ApoA-I mimetic peptide infusions in rabbits. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:765–773. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell BC, Collins FS, Nabel EG. Mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in accelerated aging syndromes. Circ Res. 2007;101:13–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aortic stenosis. Lancet. 2009;373:956–966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet MC, Arsenault M, Couet J. Experimental aortic valve stenosis in rabbits. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet MC, Roussel E, Deshaies Y, Couet J, Arsenault M. A high fat/high carbohydrate diet induces aortic valve disease in C57Bl/6J mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokin AA, Robicsek F, Cook JW, Thubrikar MJ, Schaper J. Morphological changes of the aortic valve leaflets in non-compliant aortic roots: in-vivo experiments. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13:444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondard O, Detaint D, Iung B, Choqueux C, Adle-Biassette H, Jarraya M, et al. Extracellular matrix remodelling in human aortic valve disease: the role of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1333–1341. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RV, Otto CM. Spectrum of calcific aortic valve disease: pathogenesis, disease progression, and treatment strategies. Circulation. 2005;111:3316–3326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.486738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis ZS, Johnson C, Godin D, Magid R, Shipley JM, Senior RM, et al. Targeted disruption of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene impairs smooth muscle cell migration and geometrical arterial remodeling. Circ Res. 2002;91:852–859. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000041036.86977.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimard BH, Larson JM. Aortic stenosis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubitzsch H, Beholz S, Wollert HG, Eckel L. Severe heart valve calcification in a young patient with Werner syndrome. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2000;9:53–54. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(99)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerraty M, Mohler IIIER. Models of aortic valve calcification. J Invest Med. 2007;55:278–283. doi: 10.2310/6650.2007.00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helske S, Kupari M, Lindstedt KA, Kovanen PT. Aortic valve stenosis: an active atheroinflammatory process. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:483–491. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282a66099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton RB, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circ Res. 2006;98:1431–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224114.65109.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjortnaes J, Butcher J, Figueiredo JL, Riccio M, Kohler RH, Kozloff KM, et al. Arterial and aortic valve calcification inversely correlates with osteoporotic bone remodelling: a role for inflammation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1975–1984. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, George SJ, Newby AC, Jackson CL. Divergent effects of matrix metalloproteinases 3, 7, 9, and 12 on atherosclerotic plaque stability in mouse brachiocephalic arteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15575–15580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Lee YH, Kim KH, Lee SH, Cha JY, Shin EK, et al. Role of lung apolipoprotein A-I in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect on experimental lung injury and fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:633–642. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0659OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel M, Leder P. A deletion within the murine Werner syndrome helicase induces sensitivity to inhibitors of topoisomerase and loss of cellular proliferative capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13097–13102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde D, Yap SC, van Dijk AP, Budts W, Pieper PG, van der Burgh PH, et al. Effects of rosuvastatin on progression of stenosis in adult patients with congenital aortic stenosis (PROCAS Trial) Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus IM, Naylor AR, Goodall S, Crowther M, Jones L, Bell PR, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in unstable carotid plaques. A potential role in acute plaque disruption. Stroke. 2000;31:40–47. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommi JI, Kovanen PT, Jauhiainen M, Lee-Rueckert M, Kupari M, Helske S. High-density lipoproteins (HDL) are present in stenotic aortic valves and may interfere with the mechanisms of valvular calcification. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makous N, Friedman S, Yakovac W, Maris EP. Cardiovascular manifestations in progeria. Report of clinical and pathologic findings in a patient with severe arteriosclerotic heart disease and aortic stenosis. Am Heart J. 1962;64:334–346. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(62)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijianowski MM, Teeling P, Mann J, Becker AE. Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with an increase in the type I/type III collagen ratio: a quantitative assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massip L, Garand C, Turaga RV, Deschênes F, Thorin E, Lebel M. Increased insulin, triglycerides, reactive oxygen species, and cardiac fibrosis in mice with a mutation in the helicase domain of the Werner syndrome gene homologue. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers CD, Kashyap ML. Pharmacologic augmentation of high-density lipoproteins: mechanisms of currently available and emerging therapies. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2005;20:307–312. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000167718.30076.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Weiss RM, Serrano KM, Castaneda LE, Brooks RM, Zimmerman K, et al. Evidence for active regulation of pro-osteogenic signaling in advanced aortic valve disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2482–2486. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.211029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Weiss RM, Heistad DD. Calcific aortic valve stenosis: methods, models, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2011;108:1392–1412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.234138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemes A, Forster T, Csanady M. Reduction of coronary flow reserve in patients with increased aortic stiffness. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:818–822. doi: 10.1139/y07-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol JW, Khan AR, Birbach M, Gaynor JW, Gooch KJ. Hemodynamics and axial strain additively increase matrix remodeling and MMP-9, but not MMP-2, expression in arteries engineered by directed remodeling. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1281–1290. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SE, Tsunoda T, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Cooper CJ, Yasin M, et al. Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2292–2300. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, et al. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1556–1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobari S, Mongrain R, Campbell I, Leask R, Cartier R. Assessment of pathological conditions using a 3D model of the aortic valve. 2009a. 6th Interdisciplinary Graduate Student Research Symposium; 2009 March; McGill University.

- Nobari S, Mongrain R, Campbell I, Leask R, Cartier R. Derivation of surrogate variables to assess pathological conditions using a 3D model of the aortic valve. 2009b. pp. 967–968. ASME Summer Bio-engineering Conference 2009. PT A-B.

- Nobari S, Mongrain R, Gaillard E, Leask R, Cartier R. Therapeutic vascular compliance change may cause significant variation in coronary perfusion: a numerical study. Comput Math Methods Med. 2012;2012:791686. doi: 10.1155/2012/791686. doi: 10.1155/2012/791686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauschinger M, Knopf D, Petschauer S, Doerner A, Poller W, Schwimmbeck PL, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with significant changes in collagen type I/III ratio. Circulation. 1999;99:2750–2756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamannan NM. Calcific aortic stenosis: lessons learned from experimental and clinical studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:162–168. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamannan NM, Evans FJ, Aikawa E, Grande-Allen KJ, Demer LL, Heistad DD, et al. Calcific aortic valve disease: not simply a degenerative process: a review and agenda for research from the National Heart and Lung and Blood Institute Aortic Stenosis Working Group. Executive summary: calcific aortic valve disease-2011 update. Circulation. 2011;124:1783–1791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollé F, Cornu E, Virot P, Chauvreau C, Christidès C, Laskar M. Calcified aortic valvular disease associated with adult progeria. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1997;90:1663–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas MJ, Santana O, Escolar E, Lamas GA. Medical therapy for calcific aortic stenosis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17:133–138. doi: 10.1177/1074248411416504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speidl WS, Cimmino G, Ibanez B, Elmariah S, Hutter R, Garcia MJ, et al. Recombinant apolipoprotein A-I Milano rapidly reverses aortic valve stenosis and decreases leaflet inflammation in an experimental rabbit model. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2049–2057. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripathi VC, Kumar RK, Balakrishnan KR. Further insights into normal aortic valve function: role of a compliant aortic root on leaflet opening and valve orifice area. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:844–851. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabet F, Rye KA. High-density lipoproteins, inflammation and oxidative stress. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;116:87–98. doi: 10.1042/CS20080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Sata M, Fukuda D, Suematsu Y, Motomura N, Takamoto S, et al. Age-associated aortic stenosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif JC, Grégoire J, L'Allier PL, Ibrahim R, Lespérance J, Heinonen TM, et al. Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1675–1682. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.jpc70004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.