Background: The spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) gene encoding ataxin-1 (ATXN1) contains an alternative open reading frame overlapping the ATXN1 coding sequence.

Results: The alternative ATXN1 protein is constitutively co-expressed and interacts with ATXN1 N terminus. Alternative ATXN1 is also an RNA binding protein.

Conclusion: ATXN1 is a genuine dual coding gene.

Significance: Alternative ATXN1 may regulate the function of ATXN1 in physiological and pathological conditions.

Keywords: Ataxia, Gene Expression, Nucleus, RNA-Binding Protein, Translation, Alternative Translation Initiation, Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1, Dual Coding Gene, Overlapping Reading Frame

Abstract

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 is an autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia associated with the expansion of a polyglutamine tract within the ataxin-1 (ATXN1) protein. Recent studies suggest that understanding the normal function of ATXN1 in cellular processes is essential to decipher the pathogenesis mechanisms in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. We found an alternative translation initiation ATG codon in the +3 reading frame of human ATXN1 starting 30 nucleotides downstream of the initiation codon for ATXN1 and ending at nucleotide 587. This novel overlapping open reading frame (ORF) encodes a 21-kDa polypeptide termed Alt-ATXN1 (Alternative ATXN1) with a completely different amino acid sequence from ATXN1. We introduced a hemagglutinin tag in-frame with Alt-ATXN1 in ATXN1 cDNA and showed in cell culture the co-expression of both ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1. Remarkably, Alt-ATXN1 colocalized and interacted with ATXN1 in nuclear inclusions. In contrast, in the absence of ATXN1 expression, Alt-ATXN1 displays a homogenous nucleoplasmic distribution. Alt-ATXN1 interacts with poly(A)+ RNA, and its nuclear localization is dependent on RNA transcription. Polyclonal antibodies raised against Alt-ATXN1 confirmed the expression of Alt-ATXN1 in human cerebellum expressing ATXN1. These results demonstrate that human ATXN1 gene is a dual coding sequence and that ATXN1 interacts with and controls the subcellular distribution of Alt-ATXN1.

Introduction

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1)3 is a lethal autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive loss of motor coordination resulting from dysfunction and degeneration of the cerebellum. At the cellular level, atrophy of Purkinje cells from the cerebellar cortex is a pathological hallmark of SCA1. Isolation of the ATXN1 gene led to the observation that there is a direct correlation between the size of a (CAG)n repeat expansion in the gene and the age of onset of the disease (1). Normal alleles have a size range of 19–36 repeats, whereas pathological alleles have 39–82 repeats.

Individuals with >70 repeats develop a juvenile form of SCA1 (1, 2). The ATXN1 gene encodes ataxin-1 (ATXN1), a nuclear 98-kDa protein. CAG repeats encode a polyglutamine stretch of variable length, and the mutant polyglutamine ATXN1 misfolds and forms inclusions in the nuclei of different types of neurons (3).

The detailed pathogenic mechanism leading to gradual neuronal degeneration in SCA1 has not been determined, but biochemical studies and genetic data from mice models revealed several important facts. First, loss of function of ATXN1 is not the primary cause of toxicity in SCA1 as mice lacking ATXN1 do not show a SCA1-like phenotype (4). Yet loss of function may partially contribute to neuronal dysfunction through transcriptional dysregulation and abnormal protein interactions (5–7). Second, nuclear localization of the mutant polyglutamine-expanded ATXN1 is essential for the pathology (8). Third, SCA1 can develop in the absence of nuclear inclusions (8, 9). Fourth, the phosphorylation of Ser-776 is necessary for the development of the disease (10). These data and others suggest a complex pathogenic mechanism with contributions of both gain-of-toxic function of mutant ATXN1 in the nucleus and loss-of-function of the normal ATXN1 (6, 7).

The normal function of ATXN1 is still unclear. ATXN1 KO mice display impairments in learning and memory (4). ATXN1 also stimulates β-secretase processing of β-amyloid precursor protein (11). ATXN1 binds RNA and several transcription factors, and there is evidence that ATXN1 is involved in transcriptional regulation (7, 12, 13). ATXN1 genetically and physically interacts with many proteins, and further studies are required to use these data to elucidate the biological function of ATXN1 (14).

Given the complexity associated to ATXN1 in health and disease, we re-examined the ATXN1 coding sequence (CDS) and noticed a potential overlapping open reading frame (ORF) between bp 30 and 587. We show that the protein encoded in this overlapping ORF, termed Alt-ATXN1 (alternative ATXN-1) is co-expressed with ATXN1, and that Alt-ATXN1 interacts with ATXN1 in the nucleus. Furthermore, the presence of Alt-ATXN1 in nuclear inclusions is fully dependent on ATXN1 co-expression. These findings have direct implications regarding the comprehension of the function of ATXN1 in health and disease and more generally regarding gene usage in mammals.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning

All primer sequences are outlined in supplemental Table S1. ATXN1(30Q) cDNA with 30 CAG repeats was purchased from Addgene (ID16133, Cambridge, MA). cDNAs were amplified using primers ATXN1 F and ATXN1 R. The PCR products were digested with HindIII and NotI and inserted into the multiple cloning site of pCEP4β (Invitrogen). ATXN1(HA) was produced by inserting an HA tag in the +3 frame of human ATXN1 between bases 584 and 585 of the CDS by PCR overlap extension using the forward primers ATXN1 F and ATXN1(HA) overlap F and the reverse primers ATXN1(HA) overlap R and ATXN1 R. ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA), in which the alternative ATG at bp 132 of ATXN1(HA) was mutated to AAG, was produced by PCR overlap extension using the forward primer ATXN1 F and ATXN1(ATG132)(HA) overlap F and the reverse primers ATXN1(ATG132)(HA) overlap R and ATXN1 R. ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA) with the alternative ATG at bp 30 mutated to AAG was produced as described above with forward primers ATXN1 F and ATXN1(ATG30)(HA) overlap F and reverse primers ATXN1(ATG30)(HA) overlap R and ATXN1 R. ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) was produced as described above. Alt-ATXN1HA was amplified using the primers Alt-ATXN1 HindIII F and ATXN1(HA) overlap R and then inserted in StrataClone PCR Cloning vector pSC-A-amp/kan using the StrataClone PCR Cloning kits (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plasmid was then double-digested with HindIII and inserted into the multiple cloning site of pCEP4β. ATXN1(82Q) cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. Harry T. Orr (University of Minnesota). Myc-MBP-M9M construct was kindly provided by Dr. Yuh Min Chook (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) (15).

ATXN1DsRed2 was produced by PCR overlap using the forward primers DsRed HindIII F and DsRed-ATXN1 overlap R and the reverse primers DsRed-ATXN1 overlap F and ATXN1 R. PCR product was thereafter digested with HindIII and NotI and inserted in the multiple cloning site of pCDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen). ATXN1DsRed2 (K772T) 30Q or 82Q were produced using QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions using primers ATXN1-K772T F and ATXN1-K772T R.

Alt-ATXN1EGFPN1 was produced by amplifying Alt-ATXN1 DNA sequence using primers Alt-ATXN1 HindIII F and Alt-ATXN1 EcoRI BamHI R. The PCR product was digested with HindIII, and EcoRI was inserted in the multiple cloning site of pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA).

GST-Alt-ATXN1 was amplified by PCR using Alt-ATXN1HA as a template and the forward primer Alt-ATXN1-pGEX-4T1-EcoR1 F and the reverse primer ARF-HA-pGEX-4T1-NotI R. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and NotI and inserted into the multiple cloning site of pGEX-4T1 (GE Healthcare). His6-ATXN1 was produced by amplifying ATXN1 with forward primers Atxn1-pRSETA-XhoI F and the reverse primer Atxn1-pRSETA-HindIII R. The PCR product was inserted into the multiple cloning site of pRSET A (Invitrogen). The different His6-ATXN1 fragments were amplified from the wild type ATXN1 sequence using forward primers 1–360 F, 250–547 F, 425–689 F, and 568–816 F and reverse primers 1–360 R, 250–547 R, 425–689 R, and 568–816 R. The constructs were introduced in NheI predigested pRSET A using Gibson Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipwich, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies and Reagents

Primary antibodies used were polyclonal anti-ATXN1 (C-20, sc-8766; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), polyclonal anti-ATXN1 (catalog no. A302-292 A, Bethyl, Montgomery, TX), monoclonal anti-ATXN1 (catalog no. 73-122, Neuromab, Davis, CA), polyclonal anti-GAPDH (catalog no. ab9485, Abcam, Toronto, ON, Canada), monoclonal anti-HA (catalog no. MMS-101R, Covance, Montreal, QC, Canada), monoclonal anti-β-actin (clone AC-15, Sigma), monoclonal anti-HA (clone C29F4, Cell Signaling Technology, Whitby, ON, Canada), monoclonal anti-Myc (9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), polyclonal anti-SP1 (PEP 2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), polyclonal anti-GST (sc-459; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), monoclonal anti- Penta-His (catalog no. 34660, Qiagen, Toronto, ON, Canada), and polyclonal anti-hnRNP A1 kindly provided by Dr. Benoit Chabot (Université de Sherbrooke). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human Alt-ATXN1 were raised either against residues 129CQLHPITADPPNRQPRHQ146 and affinity-purified (Biomatik, Cambridge, ON, Canada) or against residues 158HSIPALPAGGLFHSAG172 and affinity-purified (Abnova, Walnut, CA). Secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (NA931V, GE Healthcare), HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (NA934V, GE Healthcare), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (A-11701, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-21069, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (A-11019, Invitrogen), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-11070, Invitrogen). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise stated.

Cell Culture and Drug Treatments

Human epithelial kidney cells (HEK293), HeLa cells, and murine neuroblastoma cells (N2a) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Wisent, St-Bruno, QC, Canada). Nonessential amino acids were also added to N2a cells. Cells were transfected with GeneCellin transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioCellChallenge, La Seyne-sur-Mer, Toulon, France). For drug treatments, cells were incubated for 3 h with 5 μg/ml actinomycin D or 25 μg/ml 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole riboside or for 1 h with 0.5 mm sodium arsenite. Human glioblastomas cells were a generous gift from Dr. David Fortin (Université de Sherbrooke). Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and research on human cells was approved from the Research ethics board for human subjects “Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke.” Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Wisent).

siRNA Treatments

Human glioblastoma cells were plated in a 100-mm plate in fresh medium containing no antibiotics. After 24 h, ATXN1 siRNA (catalog no. J-004510-07, Thermo Scientific, Walthan, MA) or AllStars Negative Control siRNA (catalog no. 1027281, Qiagen) was transfected into the cells at a final concentration of 100 nm using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 72 h, cells were harvested, and lysate was processed for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis to assess knockdown efficiency. Experiments were repeated four times.

Sample Preparation and Immunoblotting

Cells samples were prepared for immunoblotting as previously described (16). Human cerebellum extracts were purchased from Novus Biologicals (catalog no. NB820-59180, Oakville, ON, Canada). Proteins were detected by Western blot using anti-ATXN1 (NeuroMab, 1/2000), anti-Alt-ATXN1 (Biomatik, 2 μg/ml), and anti-Alt-ATXN1 (Abnova, 30 μg/ml) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells from a 100-mm plate were washed, lysed, and cleared as described (17). Briefly cells were lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0,5% Nonidet P-40, Complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) for 15 min at 4 °C with rocking, sheared with a syringe, and cleared at 15,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min.

For ATXN1 immunoprecipitation, lysates were diluted in immunoprecipitation buffer (same as the lysis buffer but without glycerol) at a protein concentration of 1 μg/μl in a 750-μl final volume. Thereafter, bethyl anti-ATXN1 antibody was incubated at a concentration of 1 ng/μl at 4 °C with rocking. After 12 h of incubation, 20 μl of protein A/G plus beads (Santa Cruz) were mixed for 1–4 h long with rocking at 4 °C. Beads were then harvested with a 5000 × g centrifugation for 5 min at 4 °C and washed once for 15 min and twice for 5 min at 4 °C. The bound proteins were eluted by incubating for 5 min at 95 °C in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (0.5% SDS (w/v), 1.25% 2-mercaptoethanol (v/v), 4% glycerol (v/v), 0.01% bromphenol blue (w/v), 15 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). Proteins were detected by Western blot using anti-HA (Covance, 1/500) and anti-ATXN1 (Bethyl, 1/2000) antibodies.

For Alt-ATXN1 immunoprecipitation, minor modifications were introduced in the above protocol: 1 ml of lysates were incubated at a protein concentration of 2 mg/ml and 80 μl of anti-HA Affinity Matrix (Roche Applied Science) for 2 h at 4 °C with rocking. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer without 2-mercaptoethanol to prevent the elution of anti-HA antibodies light chains. The eluates were transferred into new tubes, and 2-mercaptoethanol was then added to the samples.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was carried out as previously described (18). Primary antibodies were diluted as follow: anti-HA (Cell Signaling) 1/500, anti-ATXN1 (Santa Cruz) 1/500, anti-hnRNP A1 1/250, anti-SP1 1/50, anti-Myc 1/100. Confocal analysis was carried out as previously described (19).

Subcellular Fractionation

Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were isolated as previously described (20).

GST Pulldown Assay

GST and GST-Alt-ATXN1HA were produced and purified as previously described with minor modifications (21). Briefly, pGEX-4T1 and Alt-ATXN1-pGEX-4T1 were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL-21(λDE-3) (EMD Bioscience, Mississauga, ON, Canada). One clone from each construct was amplified in 100 ml of LB medium and induced for 6 h with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 37 °C with shaking. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in PBS, Triton 1%, pH 7.4, and treated with 1 mg/ml lysozyme for 30 min at 4 °C with shaking. The mixture was then sonicated and centrifuged to obtain a clear lysate. The lysate was incubated with 100 μl of glutathione-agarose beads (catalog no. 17-0756-01, GE Healthcare) for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were washed 3 times with PBS, 1% Triton and resuspended with 100 μl of the same buffer.

For His6-ATXN1 and the different His6-ATXN1 fragments purification, cells were resuspended with 300 mm NaCl, 50 mm NaH2PO4, and 10 mm imidazole, pH 8.0. The lysate was incubated with 100 μl of nickel resin beads (catalog no. 88221, Thermo Scientific) at 4 °C. Beads were washed 4 times with the resuspension buffer containing 20 mm imidazole. Purified His6-ATXN1 was eluted with 100 μl of resuspension buffer containing 250 mm imidazole.

15 μl of recombinant GST or GST-Alt-ATXN1 fixed on glutathione-agarose beads was incubated with 15 μl of purified His6-tagged ATXN1 for 12 h at 4 °C in 500 μl of PBS, Triton 1%, 1 mm DTT. The beads were washed three times using the same buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot. For the different ATXN1 fragment constructs, the same amount of GST-Alt-ATXN1 bound to the beads was used (5 μl) for each pulldown. Approximately the same amount of each ATXN1 fragment was incubated with the GST-Alt-ATXN1 beads.

Pulldown Assays of Alt-ATXN1HA with Oligo(dT)-cellulose

Assays were performed as previously described with minor modifications (22). Briefly, cells (confluent 100-mm plate) were lysed with 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl, 1% Triton, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm DTT) containing 430 units of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen). The lysate was homogenized using QIAshredder (Qiagen) and centrifuged for 2 min at 18,000 × g. The supernatant was incubated for 10 min at room temperature with 20 mg of oligo(dT)-cellulose (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. The beads were washed 4 times for 5 min with 1 ml of lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. For the oligonucleotides polymers competition experiment, oligo(dT)-cellulose was preincubated with 10 mg of polyadenylic acid. In the control experiment, there was no KCl in the lysis buffer.

Conservation Analyses

Transcript information was retrieved on the NCBI Gene Database for all the species selected (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), then transcribed in silico with the ExPASy Translate tool webserver. The ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 protein sequences obtained for the different species were analyzed using the standard settings of the multiple sequence alignment tool Clustal Omega.

RESULTS

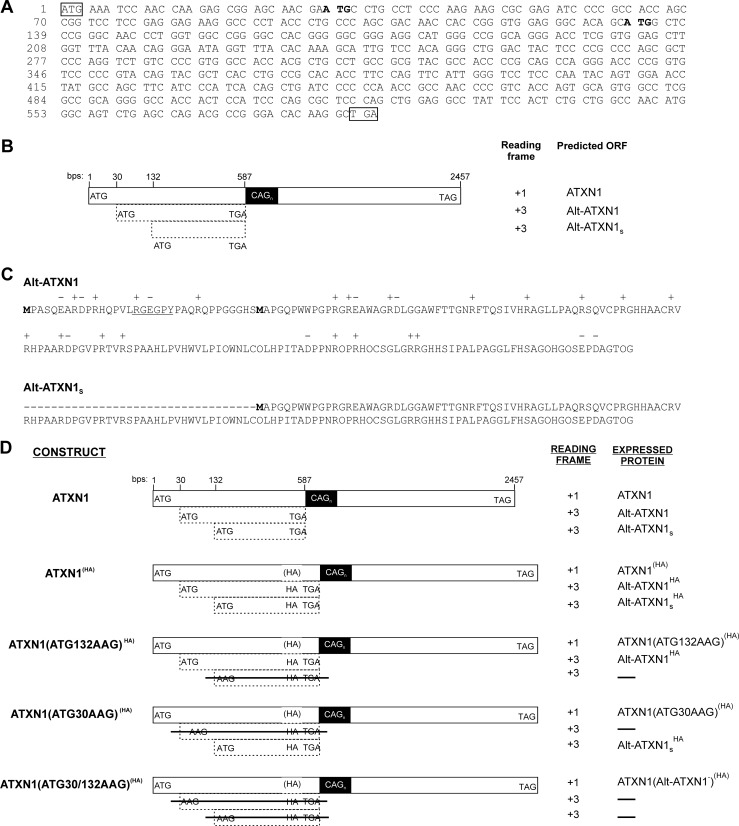

Alt-ATXN1 Is Expressed from ATXN1 cDNA

We noticed an alternative open reading frame in the +3 reading frame in ATXN1, with the ATG codon between bp 30 and 32 and a stop codon between bp 585 and 587, upstream of the (CAG)n repeats domain (Fig. 1, A and B). This ORF encodes a potential polypeptide termed Alt-ATXN1. Alt-ATXN1 is a 185-amino acid-long protein with a calculated molecular mass of 21 kDa and is highly basic despite the complete absence of lysine residues (20 Arg and 14 His; pI = 11.5) (Fig. 1C). Another feature of Alt-ATXN1 is the high proline content, with 26 Pro residues distributed throughout the protein. This alternative ORF also encodes a potential shorter isoform (151 amino acids, 17 kDa) from ATG at bp 133–135 termed Alt-ATXN1S (Fig. 1, A–C). Interestingly, the alternative ORF encoding Alt-ATXN1 long or short isoform in human is present in many eukaryotes, and the predicted proteins that they encode are fairly conserved among the different species, highlighting the potential importance of Alt-ATXN1 in biological processes (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

An alternative ORF overlaps ATXN1 coding sequence in the +3 reading frame. A, shown is the human ATXN1 DNA sequence starting from the ATXN1 start codon (boxed) up to the Alt-ATXN1 stop codon between bp 585–587 (boxed). For clarity purposes, the remaining ATXN1 CDS (up to bp 2448) is not shown. Initiation codons for the long and short Alt-ATXN1 isoforms are shown in bold. B, a diagram of ATXN1 CDS shows different features of ATXN1, including the localization of the long (Alt-ATXN1) and short (Alt-ATXN1S) alternative ATXN1 protein isoforms. Note that Alt-ATXN1 stop codon is located just upstream of the (CAG)n repeats domain. C, shown is the amino acid sequence of Alt-ATXN1. The N-terminal methionine residues of Alt-ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1S isoforms are labeled in bold. A putative PY-NLS with the sequence RGEGPY is underlined. D, shown is the strategy used to detect Alt-ATXN1 by introducing an HA tag at the C terminus of Alt-ATXN1. In ATXN1(HA), ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA), ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA) , and ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA), an HA tag (gray box), was inserted at the C terminus of Alt-ATXN1. The parentheses surrounding the HA in the ATXN1 reading frame represent the fact that the HA epitope sequence is encoded in the Alt-ATXN1 reading frame and is, therefore, undetected if expressed from the ATG codon at bp 1 of the ATXN1 CDS. ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA) and ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA) are identical to ATXN1(HA) except that the ATG codons at bp 132 and 30 have been mutated to AAG, respectively. ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) is identical to ATXN1(HA) except that both ATG codons at bp 30 and 132 have been mutated to AAG.

Because Alt-ATXN1 is a novel protein with a sequence completely different from that of ATXN1, we introduced an HA tag within ATXN1 cDNA containing 30 CAG repeats to produce Carboxyl-tagged Alt-ATXN1HA (Fig. 1D). This construct is termed ATXN1(HA) where (HA) indicates that the HA tag is silent within the reading frame of ATXN1. We also generated control constructs unable to express Alt-ATXN1, Alt-ATXN1S, or both isoforms (Fig. 1D). These constructs are ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA) and ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA) in which the alternative initiation codons between bp 132–135 and 30–32 were inactivated, respectively. Both alternative initiation codons were inactivated in the ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) construct.

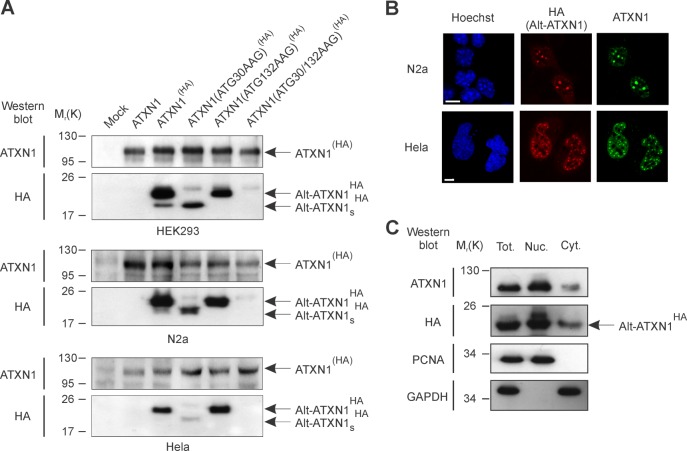

Lysates from mock-transfected cells and cells transfected with ATXN1, ATXN1(HA), ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA), ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA), or ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) were probed with both anti-ATXN1 and anti-HA antibodies. All constructs were expressed in different cell lines (Fig. 2A). Remarkably, two bands corresponding to the expected molecular weights for Alt-ATXN1HA and Alt-ATXN1SHA were detected in lysates from cells expressing ATXN1(HA) (Fig. 2A). The identity of these bands was confirmed in cells expressing various ATXN1(HA) mutants. Cells transfected with ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA) or ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA) did not express Alt-ATXN1HA or Alt-ATXN1SHA, respectively. Cells transfected with ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) did not express either Alt-ATXN1HA or Alt-ATXN1SHA. These results clearly indicate that initiation of Alt-ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1S occurred at the identified alternative initiations sites. The results also show that Alt-ATXN1S levels are insignificant compared with Alt-ATXN1 levels in HEK293 cells, and Alt-ATXN1S was barely detected in N2a and in HeLa cells.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of Alt-ATXN1. A, shown is a Western blot against ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 (HA epitope) in HEK293, N2a cells, and HeLa cells mock-transfected or transfected with ATXN1, ATXN1(HA), ATXN1(ATG132AAG)(HA), ATXN1(ATG30AAG)(HA), or ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) constructs. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left. This experiment is representative of three independent experiments in each cell line. B, shown is confocal microscopy of cells transfected with ATXN1(HA) and immunostained with anti-HA (red channel) and anti-ATXN1 (green channel) antibodies. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue channel). Scale bar, 5 μm. C, total extracts (Tot.), nucleus (Nuc.), and cytoplasmic (Cyt.) fractions from HEK293 cells expressing ATXN1(HA) were immunoblotted for Alt-ATXN1HA, the nuclear marker proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and the cytosolic marker GAPDH. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left. This experiment is representative of two independent experiments.

We verified the expression of Alt-ATXN1 by immunofluorescence and addressed the subcellular localization of this novel protein in N2a and HeLa cells transfected with ATXN1(HA) (Fig. 2B). As expected, ATXN1 was mainly detected in small intranuclear inclusions. Alt-ATXN1 was also predominantly present in similar intranuclear inclusions. The nuclear localization was confirmed by subcellular fractionation (Fig. 2C). Similar to ATXN1, Alt-ATXN1 was mainly detected in the nuclear fraction. Overall, these results show that ATXN1 encodes two nuclear proteins, ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1.

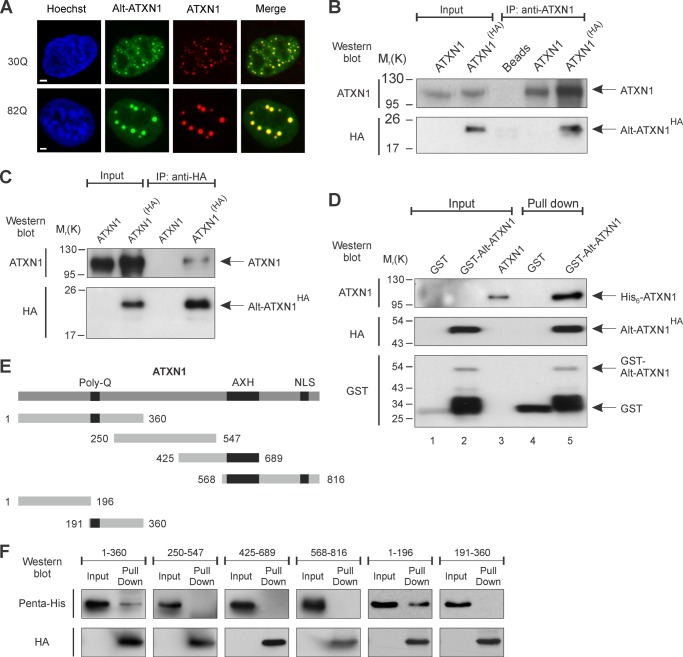

ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 Colocalize in the Nucleus and Interact

Because both ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 are localized in the nucleus, we addressed more precisely the question of their colocalization with ATXN1DsRed2 and Alt-ATXN1EGFP constructs. Cells transfected with ATXN1DsRed2 and Alt-ATXN1EGFP were analyzed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3A). As expected, ATXN1DsRed2 displayed mainly a typical localization in nuclear inclusions in addition to a minor diffuse nucleoplasmic distribution. Strikingly, Alt-ATXN1EGFP clearly colocalized with ATXN1 in nuclear inclusions and in the nucleoplasm. Because SCA1 is caused by expansion of CAG repeats in the ATXN1 gene, we determined if CAG expansion modifies the localization of Alt-ATXN1. We observed that colocalization of both proteins in nuclear inclusions was independent of the length of the polyglutamine tract as Alt-ATXN1EGFP colocalized with ATXN1DsRed2 (30 repetitions of glutamine residues) and ATXN1(82Q)DsRed2 with 82 repetitions (Fig. 3A). In addition, ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 colocalized in small and large inclusions.

FIGURE 3.

Alt-ATXN1 and ATXN1 colocalize in nuclear inclusions and interact. A, HeLa cells were co-transfected with Alt-ATXN1EGFP (green channel) and ATXN1DsRed2 (red channel). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue channel). ATXN1 contained 30 Gln (Q) repetitions or 82 Gln repetitions as indicated. Scale bar, 2 μm. B and C, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments with anti-ATXN1 (B) or anti-HA (C) antibodies were performed using lysates from N2a cells expressing ATXN1 or ATXN1(HA). This experiment is representative of four independent experiments. D, binding assays were carried out with purified glutathione-Sepharose-bound GST (Input, lane 1) or GST-Alt-ATXN1HA (Input, lane 2) incubated with purified recombinant His6-ATXN1 (Input, lane 3). GST-Alt-ATXN1HA present in the binding reaction was detected using antibodies against HA or GST, and binding of His6-ATXN1 was detected with antibodies against ATXN1 (lane 5). GST was detected with antibodies against GST. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left. E, shown is a schematic representation of the different ATXN1 fragments used to determine the region responsible for its interaction with Alt-ATXN1 (48). Residues 1–360 contain the polyglutamine repetitions (Poly-Q), 250–547 contain the SAD (self-associating domain), 425–689 contain the SAD and the AXH (ATXN1/HMG-box protein 1) domain, and 568–816 contain the AXH domain and the NLS region of ATXN1. Fragments 1–360 were subsequently divided into two subdomains, residues 1–196 and 191–360). F, binding assays with purified glutathione-Sepharose-bound GST-Alt-ATXN1HA incubated with purified recombinant His6-ATXN1 fragments are shown. GST-Alt-ATXN1HA present in the binding reaction was detected using antibodies against HA, and fragments of ATXN1 were detected with antibodies against pentahistidine.

To test the interaction between ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 in neuronal cells, we transfected N2a cells with ATXN1(HA). Immunoprecipitation with anti-ATXN1 antibodies showed that Alt-ATXN1HA interacts with ATXN1 (Fig. 3B). In a control experiment, cells were transfected with untagged ATXN1. In these cells Alt-ATXN1 does not bear an HA tag and should not be detected after immunoprecipitation. As expected, Alt-ATXN1 was not detected with anti-HA antibodies after ATXN1 immunoprecipitation. The interaction between ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 was confirmed by reverse immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies; these antibodies co-immunoprecipitated Alt-ATXN1HA and ATXN1(HA) (Fig. 3C).

To further examine if the interaction between ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 is direct, we used an in vitro GST pulldown assay. We produced and purified recombinant GST, GST-Alt-ATXN1HA, and His6-ATXN1 proteins and incubated GST or GST-Alt-ATXN1HA with His6-ATXN1. His6-ATXN1 showed a strong binding with GST-Alt-ATXN1HA but not with GST, thus confirming the direct and specific interaction between ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 (Fig. 3D, compare lanes 4 and 5). All together, these results clearly demonstrate that ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 directly interact.

To determine more precisely the domain of ATXN1 responsible for its interaction with Alt-ATXN1, we produced and purified different His6-tagged ATXN1 fragments (Fig. 3E). These fragments were incubated with the same amount of GST-Alt-ATXN1HA. Pulldown assays show that only the 1–360 domain of ATXN1 is responsible for the interaction with Alt-ATXN1 (Fig. 3F). We further demonstrated that only the N terminus of ATXN1 (residues 1–196), and not the polyglutamine track, was responsible for its interaction with Alt-ATXN1 (Fig. 3F).

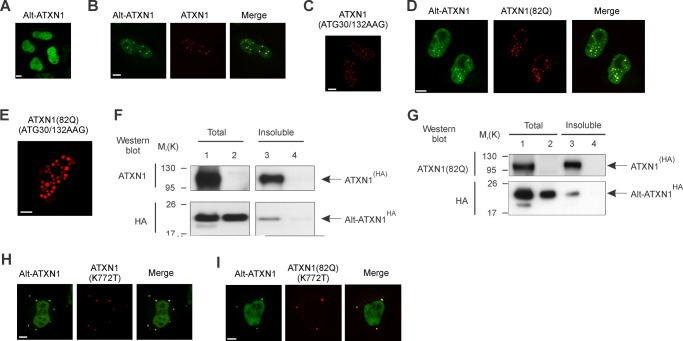

ATXN1 Promotes the Sequestration of Alt-ATXN1 in Inclusions

Based on their colocalization and interaction, we determined if one of these two proteins recruits the other protein into nuclear inclusions. Cells were transfected with Alt-ATXN1EGFP, ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)DsRed2, or co-transfected with ATXN1DsRed2 and Alt-ATXN1EGFP and observed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4, A–C). Alt-ATXN1 displayed a diffuse nucleoplasmic distribution in the absence of ATXN1 expression (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Alt-ATXN1 colocalized with ATXN1 in nuclear inclusions when co-transfected with ATXN1DsRed2 (Fig. 3B). In cells transfected with ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)DsRed2, a mutant construct that does not allow expression Alt-ATXN1, ATXN1 formed nuclear inclusions independently of the presence of Alt-ATXN1 (Fig. 4C). Identical results were observed with ATXN1(82Q) (Fig. 4, D and E). We conclude that ATXN1 spontaneously forms intranuclear inclusions in the absence of Alt-ATXN1 expression and recruits Alt-ATXN1 into these inclusions. This observation was confirmed using a solubility assay (10). Alt-ATXN1 was detected in the insoluble fraction only in cells expressing ATXN1(HA) (Fig. 4, F and G).

FIGURE 4.

ATXN1 and ATXN1(82Q) recruit Alt-ATXN1 inside inclusions. A–E, HeLa cells were transfected with Alt-ATXN1EGFP (A), Alt-ATXN1EGFP and ATXN1DsRed2 (B), ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)DsRed2 (C), Alt-ATXN1EGFP and ATXN1(82Q)DsRed2 (D), or ATXN1(82Q)(ATG30/132AAG)DsRed2 (E) and observed by confocal microscopy. F and G, a Western blot with anti-ATXN1 and anti-HA antibodies shows the proportion of ATXN1(HA) and Alt-ATXN1HA in a total cell lysate (lanes 1 and 2) and in the insoluble fraction (lanes 3 and 4) from HEK293 cells expressing ATXN1(HA) (F, lanes 1 and 3), ATXN1(82Q)(HA) (G, lanes 1 and 3), or Alt-ATXN1 (F and G, lanes 2 and 4). Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left. H and I, HeLa cells were co-transfected with Alt-ATXN1EGFP and ATXN1(K772T)DsRed2 or Alt-ATXN1EGFP and ATXN1(82Q)(K772T)DsRed2, fixed, and observed by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 10 μm.

To validate these observations, we used a nuclear localization signal mutant that forms cytoplasmic inclusions, ATXN1(K772T) (8). If ATXN1 forces Alt-ATXN1 into nuclear inclusions, the distribution of Alt-ATXN1 in cells expressing ATXN1(K772T) should remain diffuse in the nucleoplasm. Indeed, Alt-ATXN1 displayed an homogenous nucleoplasmic distribution in cells co-expressing ATXN1(K772T)DsRed2 and Alt-ATXN1EGFP (Fig. 4, H and I). Surprisingly, Alt-ATXN1 also associated with ATXN1(K772T) in cytoplasmic inclusions. These results demonstrate that ATXN1 is able to recruit Alt-ATXN1 in intracellular inclusions independently of their localization in the nucleus or the cytoplasm. They also suggest that Alt-ATXN1 can shuttle from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, similarly to ATXN1.

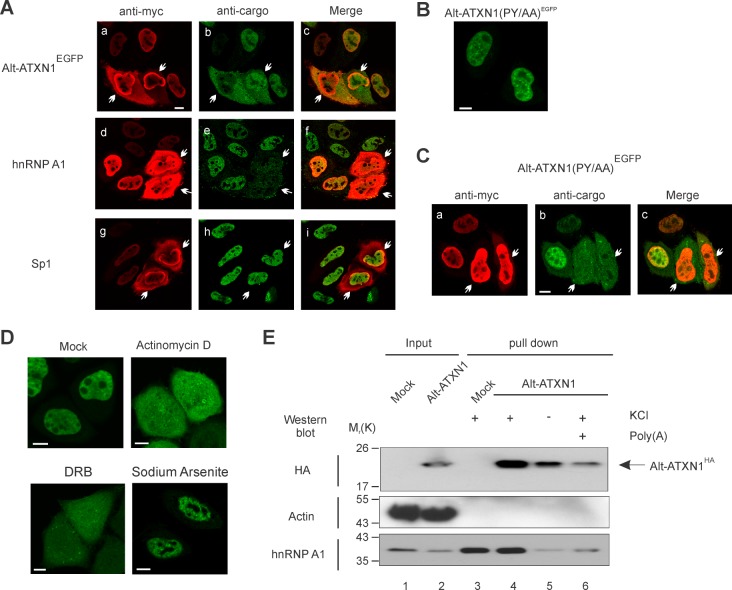

Alt-ATXN1 Nuclear Localization Is Dependent on RNA Transcription

Alt-ATXN1 does not have a predicted classical nuclear localization signal (NLS) (23), but a putative proline-tyrosine NLS (PY-NLS) within the sequence RGEGPY is present at the N terminus (24) (Fig. 1C). Two experiments were performed to test the functionality of this PY-NLS. First, because PY-NLS is specifically imported into the nucleus by karyopherin β2/transportin (Kapβ2) (24), we co-transfected the Kapβ2-specific inhibitor myc-MBP-M9M and Alt-ATXN1EGFP in HeLa cells (15). Overexpression of myc-MBP-M9M induced the mislocalization of Alt-ATXN1EGFP to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A, a–c), indicating that Kapβ2 is the nuclear importer of Alt-ATXN1. In control experiments, to confirm the specificity of myc-MBP-M9M for Kapβ2, myc-MBP-M9M mislocalized the Kapβ2 cargo hnRNP A1 (15) (Fig. 5, A, d–f). In contrast, SP1, a transcription factor that is transported into the nucleus in an importin-dependent manner (25) accumulated in the nucleus irrespective of the presence of myc-MBP-M9M. In a second approach to determine the functionality of the putative PY-NLS, a mutant Alt-ATXN1(PY/AA)EGFP construct with the PY residues changed to AA by site-directed mutagenesis was generated. Surprisingly, this mutation did not alter Alt-ATXN1(PY/AA)EGFP nuclear localization (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, overexpression of myc-MBP-M9M induced the mislocalization of Alt-ATXN1(PY/AA)EGFP to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that Alt-ATXN1 is a Kapβ2 cargo with an atypical NLS.

FIGURE 5.

Alt-ATXN1 is imported into the nucleus by Kapβ2 by a transcription-dependent mechanism and binds RNA. A, HeLa cells were co-transfected with Alt-ATXN1EGFP and myc-MBP-M9M (a–c) or transfected with myc-MBP-M9M only (d–i). Cells were processed for immunofluorescence with antibodies against myc-MBP-M9M (a, d, and g), endogenous hnRNP A1 (e), and endogenous Sp1 (h). Arrows indicate individual cells overexpressing myc-MBP-M9M at high levels. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, HeLa cells were transfected with Alt-ATXN1(PY/AA)EGFP for 24 h and visualized by confocal microscopy. C, HeLa cells were co-transfected with Alt-ATXN1(PY/AA)EGFP and myc-MBP-M9M. Cells were fixed 24 h post-transfection and processed for immunofluorescence with antibodies against myc. D, shown is confocal microscopy of Alt-ATXN1EGFP in mock-treated HeLa cells (Mock) and treated with actinomycin D, 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole riboside (DRB), or with sodium arsenite, as indicated. Scale bar, 5 μm. E, lysates from mock-transfected cells or cells expressing Alt-ATXN1HA (lanes 1 and 2, respectively) were incubated with oligo(dT)-cellulose beads. After extensive washing, proteins were eluted (lanes 3–6). In control experiments, cells were lysed in the absence of KCl (lane 5), or poly(A) was bound to the beads before pulldown (lane 6). Alt-ATXN1HA, hnRNP A1 and actin were detected by Western blotting. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left.

The localization of several nuclear proteins with no classical NLS is dependent on transcription (26–28). Thus, we determined if transcription inhibitors altered Alt-ATXN1 nuclear localization. Cells expressing Alt-ATXN1EGFP were treated with two inhibitors of RNA polymerase II, actinomycin D and 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole riboside (DRB) (Fig. 5D). After treatment with the drugs, Alt-ATXN1 clearly appeared in the cytoplasm. This effect was not a consequence of an unspecific stress as treatment with a sublethal dose of sodium arsenite to induce an oxidative stress (29) did not change the nuclear localization of Alt-ATXN1 (Fig. 5D).

Alt-ATXN1 Forms poly(A)+ RNA Complexes

Proteins with transcription-dependent nuclear localization generally bind to mRNAs and are involved in posttranscriptional regulation (26–28). To test if Alt-ATXN1 also binds to mRNA, we examined the binding of Alt-ATXN1HA-poly(A)+ RNA complexes to an oligo(dT)-cellulose resin. Cell lysates from cells expressing Alt-ATXN1HA or mock-transfected cells were incubated with oligo(dT)-cellulose. Alt-ATXN1HA was clearly recovered in the oligo(dT)-cellulose eluate fraction (Fig. 5E, lane 4). Two types of control experiments were performed to verify that Alt-ATXN1HA had bound to the oligo(dT)-cellulose via its association with poly(A)+ RNA. First, soluble poly(A) efficiently competed for the binding of Alt-ATXN1HA to the resin (Fig. 5E, compare lanes 4 and 6). Second, in the absence of KCl, which is required for poly(A)+ RNA binding to oligo(dT)-cellulose, Alt-ATXN1HA binding to the resin was largely inhibited (Fig. 5E, compare lanes 4 and 5). As a positive and negative control of an mRNA-binding protein, we tested in the eluate fraction the presence of hnRNP A1 and actin, respectively. Similar to Alt-ATXN1, hnRNP A1 bound to the oligo(dT)-cellulose in the presence of KCl. In contrast, actin was not recovered in the oligo(dT)-cellulose eluate fraction. All together, these results indicate that Alt-ATXN1 binds to and can be purified in association with mRNA on the oligo(dT) cellulose column.

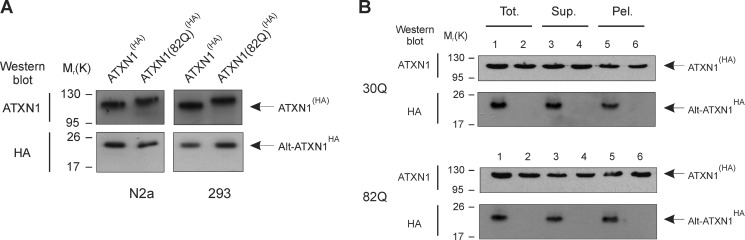

CAG Repeats Number Does Not Modify Alt-ATXN1 Expression, and Alt-ATXN1 Expression Does Not Modify ATXN1 Solubility

Because SCA1 is caused by expansion of CAG repeats in the ATXN1 gene, we determined if CAG expansion modifies Alt-ATXN1 levels. Although Alt-ATXN1 ORF is located upstream of the CAG repeats, the regulation of alternative translation is unknown, and mutations located 3′ to Alt-ATXN1 ORF might influence its expression. We compared Alt-ATXN1HA levels in cells transfected with ATXN1(HA) (30 repetitions) and ATXN1(82Q)(HA) (Fig. 6A). Levels of Alt-ATXN1HA expressed from ATXN1(HA) and ATXN1(82Q)(HA) did not significantly differ in two different cell lines.

FIGURE 6.

CAG repeats do not modify Alt-ATXN1 expression, and Alt-ATXN1 expression does not modify ATXN1 solubility. A, shown is a Western blot against ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 in lysates from N2a or HEK 293 cells transfected with ATXN1(HA) (30Q) or ATXN1(82Q)(HA) constructs. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left. B, a Western blot with anti-ATXN1 and anti-HA antibodies shows the distribution of ATXN1(HA) and Alt-ATXN1HA in a total cell lysate (Tot., lanes 1 and 2), in the soluble fraction (Sup., lanes 3 and 4), and in the insoluble fraction (Pel., lanes 5 and 6) from HEK293 cells expressing ATXN1(HA) (upper panels; lanes 1, 3, and 5), ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) (upper panels; lanes 2, 4, and 6), ATXN1(82Q)(HA) (lower panels; lanes 1, 3, and 5), or ATXN1(82Q)(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) (lower panels; lanes 2, 4, and 6).

Next, we determined if Alt-ATXN1 influences the biochemistry of ATXN1 by testing the impact of Alt-ATXN1 on the solubility of ATXN1 and ATXN1(82Q) in cultured cells. Cells were transfected with ATXN1(HA), ATXN1(82Q)(HA), ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA), and ATXN1(82Q)(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) for 24 h and lysed. Soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation, and ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 proteins were detected by Western blot (Fig. 6B). Similar to ATXN1, Alt-ATXN1 was present in both soluble and insoluble fractions. This distribution was expected because ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 have the same localization in nuclear inclusions and the nucleoplasm. The absence of Alt-ATXN1 expression in cells expressing ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) and ATXN1(82Q)(ATG30/132AAG)(HA) did not change the solubility of ATXN1 and ATXN1(82Q), respectively. We conclude that although ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 colocalize in the nucleus and interact, neither proteins has a direct impact on their expression levels and solubility.

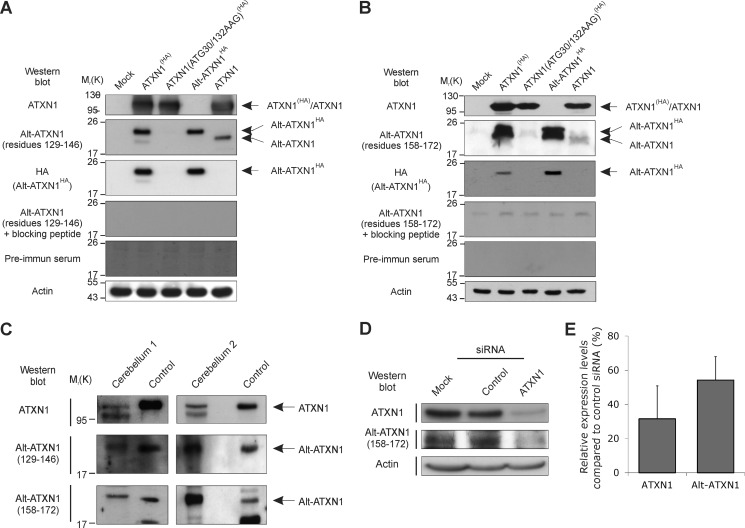

Alt-ATXN1 Is Endogenously Expressed from ATXN1

Next, we raised polyclonal antibodies against residues 129–146 or 158–172 from human Alt-ATXN1 to detect wild type Alt-ATXN1 encoded by the endogenous ATXN1 gene. To validate the antibody, Western blot experiments were performed using lysates from untransfected N2a cells (Mock) and N2a cells transfected with ATXN1(HA), ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA), Alt-ATXN1HA, or ATXN1 (Fig. 7, A and B). A band was detected with the expected molecular weight in lysates from ATXN1(HA), Alt-ATXN1HA, and ATXN1-expressing cells but not from cells expressing ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA). The addition of the immunogenic peptides to neutralize the antibodies directed against residues 129–146 or 158–172 completely prevented the detection of Alt-ATXN1. Pre-immune serum did not detect Alt-ATXN1. Therefore, both Alt-ATXN1 polyclonal antibodies specifically detect Alt-ATXN1.

FIGURE 7.

Alt-ATXN1 is endogenously expressed. A and B, validation of polyclonal antibodies against Alt-ATXN1 is shown. N2a cells were either untransfected (Mock) or transfected with ATXN1(HA), ATXN1(ATG30/132AAG)(HA), Alt-ATXN1HA, or ATXN1. Lysates were probed for Alt-ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1HA using polyclonal antibodies raised against residues 129CQLHPITADPPNRQPRHQ146 (A) or 158HSIPALPAGGLFHSAG172 (B) of Alt-ATXN1 or anti-HA antibodies. The same lysates were also probed with the anti-Alt-ATXN1 antibodies blocked with the immunogenic peptides or with the animal's pre-immune serum to demonstrate the specificity of the antibodies. Equal loading was assessed with an anti-β-actin antibody. C, two human cerebellum homogenates, cerebellum 1 (200 μg) and cerebellum 2 (100 μg), were probed for Alt-ATXN1 using two polyclonal antibodies raised against residues 129CQLHPITADPPNRQPRHQ146 or 158HSIPALPAGGLFHSAG172. A band at the same molecular weight as the one seen in 7.5-μg lysates from cells transfected with human ATXN1 (control) was detected. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left. D, endogenous Alt-ATXN1 was detected in glioblastoma cells, which express a high level of ATXN1. A siRNA against the 3′ of the coding sequence of ATXN1 greatly reduced the expression of ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1, whereas the control siRNA had no effect on the expression of both proteins. E, densitometric analysis of siRNA treatment showed a decrease (45–70%) in expression of both ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 after siRNA treatment in glioblastoma cells. Value is expressed as the mean value (±S.D.) from three independent experiments.

To test the expression of Alt-ATXN1 in a human tissue expressing ATXN1, we performed a Western blot on human cerebellum extracts (Fig. 7C). We found that both endogenous ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 are expressed, judging by the prominent band at the same molecular weight as the band present in a control cell lysate transfected with ATXN1. This result supports the evidence of Alt-ATXN1 expression in a tissue-expressing ATXN1.

We next assessed the expression of Alt-ATXN1 in primary cells from a glioblastoma of a patient, which express high levels of ATXN1. A band was detected at the expected molecular weight, suggesting endogenous expression of Alt-ATXN1 in these cells (Fig. 7D). The identity of the band was confirmed after transfecting the cells with a siRNA against ATXN1. Western blot analysis proves that Alt-ATXN1 is endogenously expressed in these cells, as ATXN1 knockdown resulted in a 65% decrease of the intensity of the band corresponding to ATXN1 and a 45% decrease of the intensity of the band corresponding to Alt-ATXN1 compared with cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 7, D and E). These results clearly demonstrated endogenous co-expression of ATXN1 and Alt-ATXN1 in primary neuronal cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe a novel protein encoded by ATXN1 and interacting with ATXN1, Alt-ATXN1. Alt-ATXN1 is constitutively expressed from an out-of-frame CDS overlapping the ATXN1 CDS and is detected in cells transfected with ATXN1 and endogenously in the human cerebellum.

In the absence of complete understanding about the physiological function of ATXN1, several studies sought to identify molecular pathways involving ATXN1 by discovering protein interactors. From such studies, it is clear that ATXN1 associates with large protein complexes and interacts with a vast network of proteins (12, 14, 30). Current knowledge indicates that ATXN1 may be involved in transcriptional repression and regulate Notch- and Capicua-controlled developmental processes (12, 31–33). Here we add Alt-ATXN1 as a novel ATXN1 protein interactor in the nucleus. Alt-ATXN1 interacts with both normal and pathological ATXN1, suggesting that it does not directly contribute to SCA1 by a simple interaction/loss of interaction mechanism. On the other hand, this result together with the observation that ATXN1 sequesters Alt-ATXN1 into nuclear inclusions and causes Alt-ATXN1 to become partially insoluble favors the hypothesis that Alt-ATXN1 is a mediator in the function of ATXN1 in normal and/or pathological conditions.

The sequestration of Alt-ATXN1 by ATXN1 in intranuclear inclusions is reminiscent of the interaction between ATXN1 and leucine-rich acidic nuclear protein (LANP, ANP32A, pp32) (49). Indeed, similar to Alt-ATXN1, transfected leucine-rich acidic nuclear protein displays a homogenous distribution in the nucleus, whereas co-transfection with ATXN1 induces its redistribution within ATXN1 inclusions (4). Leucine-rich acidic nuclear protein is a cofactor in transcriptional repression with a probable role in neuritic pathology in SCA1 (34, 35). In this context the role of Alt-ATXN1 in transcriptional repression in cooperation with ATXN1 deserves further investigations.

Another connection between Alt-ATXN1 and RNA derives from the observation that Alt-ATXN1 nuclear import pathway is dependent on RNA polymerase II transcription. This particular feature is shared with several proteins involved in RNA metabolism and regulating gene expression, including hnRNP proteins, human antigen R (HuR), deleted in azoospermia-associated protein 1 (DAZAP), Quaking I-5, TIAR, and TIA-1 (36–41). Finally, our observation that Alt-ATXN1 associates with poly(A)+ RNA definitively reinforces the hypothesis that this novel protein has a function in mRNA metabolism.

Whether coding multiple proteins with overlapping open reading frames, similar to ATXN1, is a usual feature in mammalians is not known. The only known examples include INK4a, GNAS1, XBP1, and PRNP (16, 42–44). PRNP and ATXN1 are particular in that the overlapping ORFs are entirely comprised in the CDS of the reference proteins PrP and ATXN1, respectively. Overlapping ORFs are also involved in the generation of cryptic epitopes translated from self-proteins (45–47). It is tempting to speculate that alternative translation in eukaryotes has been overlooked and may significantly contribute to the proteome. One way to address this issue would be to predict and test the expression of alternative ORFs in large scale experiments.

In summary, we discovered that in addition to ATXN1, the ATXN1 gene encodes a second protein in the non-canonical reading frame +3. This novel protein, termed Alt-ATXN1, is constitutively co-expressed and directly interacts with ATXN1 and displays RNA binding activity. Future studies will have to address whether Alt-ATXN1 may have a role in SCA1 pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Harry T. Orr for the gift of the ATXN1(82Q) cDNA clone and Dr. Yuh Min Chook for the gift of the M9M construct. We also thank Dr. Benoit Chabot for providing the hnRNP A1 antibody and Dr. David Fortin for providing the human glioblastoma cells.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-89881; to X. R.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S1.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) JX901140.

- SCA1

- spinocerebellar ataxia type 1

- ATXN1

- Ataxin 1

- Alt-ATXN1

- alternative Ataxin 1

- ORF

- open reading frame

- CDS

- coding sequence

- Kapβ2

- karyopherin β2

- NLS

- nuclear localization sequence

- PY-NLS

- proline-tyrosine NLS

- hnRNP

- heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- F

- forward

- R

- reverse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Orr H. T., Chung M. Y., Banfi S., Kwiatkowski T. J., Jr, Servadio A., Beaudet A. L., McCall A. E., Duvick L. A., Ranum L. P., Zoghbi H. Y. (1993) Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat. Genet. 4, 221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chung M. Y., Ranum L. P., Duvick L. A., Servadio A., Zoghbi H. Y., Orr H. T. (1993) Evidence for a mechanism predisposing to intergenerational CAG repeat instability in spinocerebellar ataxia type I. Nat. Genet. 5, 254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cummings C. J., Mancini M. A., Antalffy B., DeFranco D. B., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (1998) Chaperone suppression of aggregation and altered subcellular proteasome localization imply protein misfolding in SCA1. Nat. Genet. 19, 148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matilla A., Roberson E. D., Banfi S., Morales J., Armstrong D. L., Burright E. N., Orr H. T., Sweatt J. D., Zoghbi H. Y., Matzuk M. M. (1998) Mice lacking ataxin-1 display learning deficits and decreased hippocampal paired-pulse facilitation. J. Neurosci. 18, 5508–5516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crespo-Barreto J., Fryer J. D., Shaw C. A., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (2010) Partial loss of ataxin-1 function contributes to transcriptional dysregulation in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 pathogenesis. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zoghbi H. Y., Orr H. T. (2009) Pathogenic mechanisms of a polyglutamine-mediated neurodegenerative disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7425–7429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang S., Hong S. (2009) Molecular pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 disease. Mol. Cells 27, 621–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klement I. A., Skinner P. J., Kaytor M. D., Yi H., Hersch S. M., Clark H. B., Zoghbi H. Y., Orr H. T. (1998) Ataxin-1 nuclear localization and aggregation. Role in polyglutamine-induced disease in SCA1 transgenic mice. Cell 95, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cummings C. J., Reinstein E., Sun Y., Antalffy B., Jiang Y., Ciechanover A., Orr H. T., Beaudet A. L., Zoghbi H. Y. (1999) Mutation of the E6-AP ubiquitin ligase reduces nuclear inclusion frequency while accelerating polyglutamine-induced pathology in SCA1 mice. Neuron 24, 879–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emamian E. S., Kaytor M. D., Duvick L. A., Zu T., Tousey S. K., Zoghbi H. Y., Clark H. B., Orr H. T. (2003) Serine 776 of ataxin-1 is critical for polyglutamine-induced disease in SCA1 transgenic mice. Neuron. 38, 375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang C., Browne A., Child D., Divito J. R., Stevenson J. A., Tanzi R. E. (2010) Loss of function of ATXN1 increases amyloid β-protein levels by potentiating β-secretase processing of β-amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8515–8526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tong X., Gui H., Jin F., Heck B. W., Lin P., Ma J., Fondell J. D., Tsai C. C. (2011) Ataxin-1 and Brother of ataxin-1 are components of the Notch signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 12, 428–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lam Y. C., Bowman A. B., Jafar-Nejad P., Lim J., Richman R., Fryer J. D., Hyun E. D., Duvick L. A., Orr H. T., Botas J., Zoghbi H. Y. (2006) ATAXIN-1 interacts with the repressor Capicua in its native complex to cause SCA1 neuropathology. Cell 127, 1335–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lim J., Hao T., Shaw C., Patel A. J., Szabó G., Rual J. F., Fisk C. J., Li N., Smolyar A., Hill D. E., Barabási A. L., Vidal M., Zoghbi H. Y. (2006) A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell 125, 801–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cansizoglu A. E., Lee B. J., Zhang Z. C., Fontoura B. M., Chook Y. M. (2007) Structure-based design of a pathway-specific nuclear import inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 452–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vanderperre B., Staskevicius A. B., Tremblay G., McCoy M., O'Neill M. A., Cashman N. R., Roucou X. (2011) An overlapping reading frame in the PRNP gene encodes a novel polypeptide distinct from the prion protein. FASEB J. 25, 2373–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mizutani A., Wang L., Rajan H., Vig P. J., Alaynick W. A., Thaler J. P., Tsai C. C. (2005) Boat, an AXH domain protein, suppresses the cytotoxicity of mutant ataxin-1. EMBO J. 24, 3339–3351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grenier C., Bissonnette C., Volkov L., Roucou X. (2006) Molecular morphology and toxicity of cytoplasmic prion protein aggregates in neuronal and non-neuronal cells. J. Neurochem. 97, 1456–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beaudoin S., Vanderperre B., Grenier C., Tremblay I., Leduc F., Roucou X. (2009) A large ribonucleoprotein particle induced by cytoplasmic PrP shares striking similarities with the chromatoid body, an RNA granule predicted to function in posttranscriptional gene regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antonsson B., Montessuit S., Sanchez B., Martinou J. C. (2001) Bax is present as a high molecular weight oligomer/complex in the mitochondrial membrane of apoptotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11615–11623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith D. B., Corcoran L. M. (2001) Expression and purification of glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 16, Unit 16.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goggin K., Beaudoin S., Grenier C., Brown A. A., Roucou X. (2008) Prion protein aggresomes are poly(A)+ ribonucleoprotein complexes that induce a PKR-mediated deficient cell stress response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 479–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marfori M., Mynott A., Ellis J. J., Mehdi A. M., Saunders N. F., Curmi P. M., Forwood J. K., Bodén M., Kobe B. (2011) Molecular basis for specificity of nuclear import and prediction of nuclear localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1562–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee B. J., Cansizoglu A. E., Süel K. E., Louis T. H., Zhang Z., Chook Y. M. (2006) Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin β2. Cell 126, 543–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ito T., Kitamura H., Uwatoko C., Azumano M., Itoh K., Kuwahara J. (2010) Interaction of Sp1 zinc finger with transport factor in the nuclear localization of transcription factor Sp1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 403, 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michael W. M., Siomi H., Choi M., Piñol-Roma S., Nakielny S., Liu Q., Dreyfuss G. (1995) Signal sequences that target nuclear import and nuclear export of pre-mRNA-binding proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 60, 663–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pollard V. W., Michael W. M., Nakielny S., Siomi M. C., Wang F., Dreyfuss G. (1996) A novel receptor-mediated nuclear protein import pathway. Cell 86, 985–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee S., Neumann M., Stearman R., Stauber R., Pause A., Pavlakis G. N., Klausner R. D. (1999) Transcription-dependent nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking is required for the function of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 1486–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duncan R. F., Hershey J. W. (1987) Translational repression by chemical inducers of the stress response occurs by different pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 256, 651–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lim J., Crespo-Barreto J., Jafar-Nejad P., Bowman A. B., Richman R., Hill D. E., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (2008) Opposing effects of polyglutamine expansion on native protein complexes contribute to SCA1. Nature 452, 713–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee Y., Fryer J. D., Kang H., Crespo-Barreto J., Bowman A. B., Gao Y., Kahle J. J., Hong J. S., Kheradmand F., Orr H. T., Finegold M. J., Zoghbi H. Y. (2011) ATXN1 protein family and CIC regulate extracellular matrix remodeling and lung alveolarization. Dev. Cell 21, 746–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsai C. C., Kao H. Y., Mitzutani A., Banayo E., Rajan H., McKeown M., Evans R. M. (2004) Ataxin 1, a SCA1 neurodegenerative disorder protein, is functionally linked to the silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4047–4052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Riley B. E., Orr H. T. (2006) Polyglutamine neurodegenerative diseases and regulation of transcription. Assembling the puzzle. Genes Dev. 20, 2183–2192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cvetanovic M., Rooney R. J., Garcia J. J., Toporovskaya N., Zoghbi H. Y., Opal P. (2007) The role of LANP and ataxin 1 in E4F-mediated transcriptional repression. EMBO Rep. 8, 671–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cvetanovic M., Kular R. K., Opal P. (2012) LANP mediates neuritic pathology in Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Neurobiol. Dis. 48, 526–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piñol-Roma S., Dreyfuss G. (1991) Transcription-dependent and transcription-independent nuclear transport of hnRNP proteins. Science 253, 312–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fan X. C., Steitz J. A. (1998) HNS, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling sequence in HuR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15293–15298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin Y. T., Yen P. H. (2006) A novel nucleocytoplasmic shuttling sequence of DAZAP1, a testis-abundant RNA-binding protein. RNA. 12, 1486–1493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu J., Zhou L., Tonissen K., Tee R., Artzt K. (1999) The quaking I-5 protein (QKI-5) has a novel nuclear localization signal and shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29202–29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ayala Y. M., Zago P., D'Ambrogio A., Xu Y. F., Petrucelli L., Buratti E., Baralle F. E. (2008) Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3778–3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang T., Delestienne N., Huez G., Kruys V., Gueydan C. (2005) Identification of the sequence determinants mediating the nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of TIAR and TIA-1 RNA-binding proteins. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5453–5463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Quelle D. E., Zindy F., Ashmun R. A., Sherr C. J. (1995) Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell 83, 993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klemke M., Kehlenbach R. H., Huttner W. B. (2001) Two overlapping reading frames in a single exon encode interacting proteins. A novel way of gene usage. EMBO J. 20, 3849–3860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yoshida H., Matsui T., Yamamoto A., Okada T., Mori K. (2001) XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 107, 881–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang R. F., Parkhurst M. R., Kawakami Y., Robbins P. F., Rosenberg S. A. (1996) Utilization of an alternative open reading frame of a normal gene in generating a novel human cancer antigen. J. Exp. Med. 183, 1131–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rosenberg S. A., Tong-On P., Li Y., Riley J. P., El-Gamil M., Parkhurst M. R., Robbins P. F. (2002) Identification of BING-4 cancer antigen translated from an alternative open reading frame of a gene in the extended MHC class II region using lymphocytes from a patient with a durable complete regression following immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 168, 2402–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ho O., Green W. R. (2006) Alternative translational products and cryptic T cell epitopes. Expecting the unexpected. J. Immunol. 177, 8283–8289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Serra H. G., Duvick L., Zu T., Carlson K., Stevens S., Jorgensen N., Lysholm A., Burright E., Zoghbi H. Y., Clark H. B., Andresen J. M., Orr H. T. (2006) RORα-mediated Purkinje cell development determines disease severity in adult SCA1 mice. Cell 127, 697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Matilla A., Koshy B. T., Cummings C. J., Isobe T., Orr H. T., Zoghby H. Y. (1997) The cerebellar leucine-rich acidic nuclear protein interacts with ataxin-1. Nature 389, 974–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.