Abstract

In rod photoreceptors, several phototransduction components display light-dependent translocation between cellular compartments. Notably, the G protein transducin translocates from rod outer segments to inner segments/spherules in bright light, but the functional consequences of translocation remain unclear. We generated transgenic mice where light-induced transducin translocation is impaired. These mice exhibited slow photoreceptor degeneration, which was prevented if they were dark-reared. Physiological recordings showed that control and transgenic rods and rod bipolar cells displayed similar sensitivity in darkness. After bright light exposure, control rods were more strongly desensitized than transgenic rods. However, in rod bipolar cells, this effect was reversed; transgenic rod bipolar cells were more strongly desensitized than control. This sensitivity reversal indicates that transducin translocation in rods enhances signaling to rod bipolar cells. The enhancement could not be explained by modulation of inner segment conductances or the voltage sensitivity of the synaptic Ca2+ current, suggesting interactions of transducin with the synaptic machinery.

Keywords: retina, adaptation, presynaptic modulation, SNARE complex, palmitoylation

Exposure of rod photoreceptors to bright light induces the translocation of key signaling molecules, including the G protein transducin (1–4), arrestin (2, 3), and recoverin (5), between their outer segment (OS), and inner segment (IS)/synaptic terminal (spherule). Transducin’s translocation has been suggested to contribute to light adaptation, because signal amplification in the phototransduction cascade seems to be reduced after translocation (4). However, subsequent studies revealed that transducin translocation is only triggered by light intensities that saturate rods (6). Accordingly, transducin’s movement from OS to IS might contribute to light adaptation within a very limited range of illumination corresponding to the transition from rod- to cone-mediated vision. However, when light intensity decreases and vision begins to shift from cone- to rod-mediated, the reduced OS transducin concentration may allow rods to be responsive during the lengthy process of dark adaptation (7).

Light-induced transducin translocation might also serve a neuroprotective role (8). Indeed, during the day, when rods are largely unresponsive, transducin’s exit from OS cuts excessive activation of phototransduction, perhaps reducing the efficacy of proapoptotic mechanisms that contribute to cell death (8). Consistent with this idea is the finding that slow retinal degeneration in Shaker1 mice coincides with an increased light threshold for translocation of rod transducin (9). However, a direct link between transducin translocation and retinal degeneration has not been established.

Surprisingly, the possibility that the light-induced redistribution of transducin may also play a role in modulation of synaptic transmission from rods to rod bipolar cells has received little attention. Clearly, a fraction of transducin reaches rod spherules in the outer plexiform layer in bright light and returns to the OS only after several hours of dark adaptation (2, 10). Furthermore, mice lacking phosducin, a key Gβγ binding partner, display reduced ON bipolar cell sensitivity (11). Thus, a role for G-protein activity in tuning synaptic transmission between rods and bipolar cells remains plausible.

To study the functional significance of light-induced transducin translocation, we generated a transgenic mouse model where this process is impaired. Activation of heterotrimeric transducin (Gαt1β1γ1) by photoexcited rhodopsin (R*) normally facilitates the dissociation of Gαt1GTP and Gβ1γ1 subunits from one another and from the disk membrane, allowing both to diffuse to the IS and spherule of rods. Based on the well-studied diffusion mechanism of this process (4, 7, 10, 12, 13), we generated a mouse model where an artificial S-palmitoylation site was introduced into Gαt1, promoting a higher affinity for membranes. Indeed, previous studies of this mutant Gαt1A3C in Xenopus laevis rods reveal that it remains substantially in the OS after bright light exposure (14). Here, we present analysis of the Gαt1A3C mouse model, which supports the role of transducin translocation in rod survival and reveals a unique role in enhancing signal transmission from rods to rod bipolar cells.

Results

Additional Palmitoylation Impairs Light-Dependent Transducin Translocation in Gαt1A3C Rods.

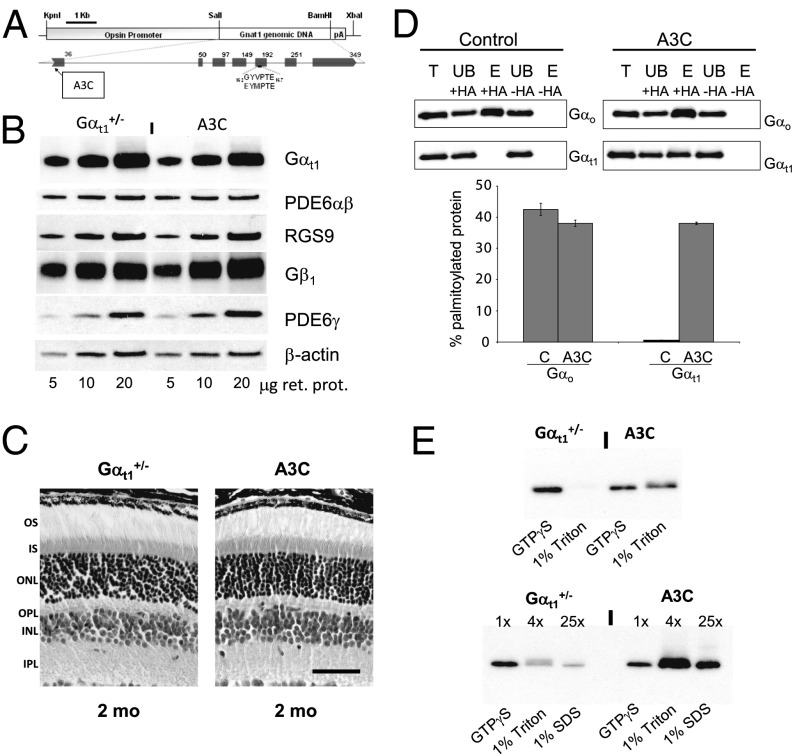

To study the role of rod transducin (Gαt1) translocation in the function of rod photoreceptors, our strategy was to generate a mouse model where translocation is impaired. Specifically, we introduced an additional S-palmitoylation site into Gαt1 that is expected to anchor Gαt1 more tightly to membranes and hinder diffusion to the IS after light exposure (14). The A3C substitution was introduced into a transgene for expression of the Glu-Glu epitope-tagged Gαt1, which is controlled by the rod opsin promoter (Fig. 1A). The Glu-Glu tagging of Gαt1 does not alter its biochemical activity or light-evoked responses measured from mouse rods (15, 16). Transgenic mice were subsequently bred into a Gαt1−/− background (17) to study the phenotype of A3C mice, which express only the mutant Gαt1A3C.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of A3C mouse retina. (A) Transgenic construct for generation of A3C mice. (B) Immunoblot analysis of key phototransduction proteins. Samples contained 5, 10, and 20 µg retinal homogenate from 2-mo-old A3C (Gαt1A3C/Gαt−/−) or control Gαt1+/− mice. The antibodies are described in Materials and Methods and SI Text. (C) Retinal morphology of 2-mo-old control and A3C mice. INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (D) Palmitoylation of Gαt1A3C using resin-assisted capture assay. Immunoblot (Upper Left) with indicated antibodies shows the elution of palmitoylated Gαo after hydroxylamine (+HA) cleavage. In contrast, native transducin (Gαt1) is not observed in these blots. In retinal extracts from A3C animals (Upper Right), both Gαo and Gαt1A3C are eluted only in presence of HA. Lower depicts the quantitative measure of observed protein palmitoylation based on elution from the resin. E, elution; T, total; UB, unbound. (E) Membrane association of Gαt1 in control and A3C mouse retinas. Soluble GTPγS-extracted, membrane Triton X-100–extracted, and Triton X-100 insoluble SDS-extracted fractions were obtained from mouse retinas as described in Materials and Methods and SI Text. The fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Gαt1 antibodies K-20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); 1×, 4×, and 25× correspond to 4%, 16%, and 100% of one-retina fractions, respectively.

Expression of Gαt1A3C in A3C mice was similar to the Gαt1 level in control Gαt1+/− mice, which express transducin at ∼80% of the level in WT mice (17) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). Given the role of phosducin in light-dependent translocation of transducin (18) and regulation of the rod-to-bipolar cell signaling (11), we examined phosducin expression and localization in the A3C retina. Neither the expression levels nor the light-independent distribution of phosducin in mouse rods was affected by the A3C mutation in Gαt1 (Fig. S2). The levels of other key phototransduction proteins in A3C and control mice were also comparable (Fig. 1B). In addition, the retinal morphology of A3C mice seemed normal at the age of 2–3 mo (Fig. 1C). Thus, A3C rods appear to be indistinguishable from control rods in every respect, except for the expression of the mutant Gαt1A3C.

The S-palmitoylation status of Gαt1A3C in the A3C retina was assessed quantitatively by a resin-assisted capture (RAC) technique (19). Native retinal Gαo, a protein known to be palmitoylated, served as positive control. Palmitoylation was dependent on hydroxylamine cleavage. This analysis showed that ∼40% of Gαt1A3C was palmitoylated, which was similar to the palmitoylation level of Gαo (Fig. 1D). No palmitoylation of Gαt1 was detected in control mice (Fig. 1D). To examine the effect of Gαt1A3C palmitoylation on its interaction with membranes, we performed extraction of bleached A3C and control retinal membranes with isotonic buffer containing GTPγS. The membrane-bound proteins were subsequently extracted with 1% Triton X-100 followed by extraction with 1% SDS. As expected, the dominant fraction of Gαt1 (>90%) from control retinas was found in the GTPγS extract (Fig. 1E). In contrast, ∼50% of Gαt1A3C remained in the membrane fraction. A small portion of the membrane-bound Gαt1A3C associates with the Triton X-100–resistant fraction (Fig. 1E).

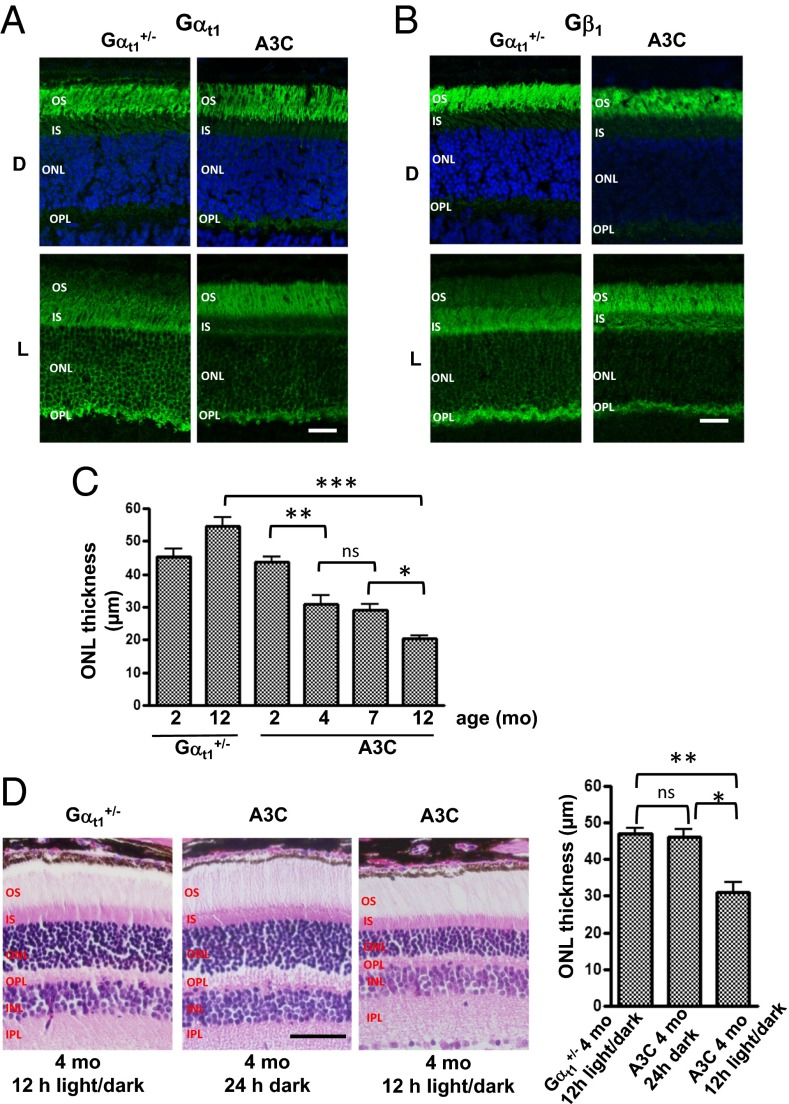

Localization of transducin in dark-adapted A3C and control mice was essentially indistinguishable. Both Gαt1A3C and Gβ1γ1 were correctly targeted to the OS (Fig. 2 A and B). Translocation of transducin was assessed in mice exposed to 500 lx light for 45 min after their pupils were dilated (Materials and Methods and SI Text). In control mice, the bulk of transducin moved in light to the IS and other rod compartments (Fig. 2 A and B and Figs. S3 and S4). However, transducin translocation in A3C mice was clearly impaired. The main fractions of Gαt1A3C (∼47%) and Gβ1γ1 (∼44%) were retained in the OS (Fig. 2 A and B and Figs. S3 and S4). However, light-induced IS→OS redistribution of arrestin was not altered in A3C mice (Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Impaired light-dependent translocation of transducin and retinal degeneration in A3C mice. Localization of (A) Gαt1 and (B) Gβ1γ1 in dark-adapted (D) and light-exposed (L; 45 min, 500 lx) control Gαt1+/− and A3C mice. Retina cryosections were stained with anti-Gαt1 or Gβ1 antibodies and counterstained with Quinolinium, 4-[3-(3-methyl-2(3H)-benzothiazolylidene)-1-propenyl]-1-[3-(trimethylammonio)propyl]-, diiodide (TO-PRO3) nuclear stain (blue in D panels). (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (C) Progression of retinal degeneration in A3C mice. The ONL thickness (mean ± SEM) was determined in four animals of each age group. *P = 0.011; **P = 0.0017; ***P = 0.0002; ns, not significant. (D) Dark rearing protects A3C mice from retinal degeneration. Retinal morphology and the ONL thickness of 4-mo-old control and A3C mice. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) *P = 0.011; **P = 0.006.

Dark Rearing Protects A3C Mice from Retinal Degeneration.

Although the retinal morphology of A3C mice maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle was normal up to 3 mo of age, by the age of 4 mo, they developed retinal degeneration (Fig. 2 C and D). The thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) of A3C mice was reduced from ∼45 μm at 2 mo to ∼31 μm at 4 mo of age (Fig. 2C). The subsequent progression of retinal degeneration in A3C mice was relatively slow, with the ONL thickness decreasing to ∼29 μm at 7 mo and ∼20 μm at 12 mo (Fig. 2C and Fig. S6). There were no significant differences in the thickness of the inner nuclear layer between control and A3C mice, indicating that the downstream retina remained intact.

We determined if retinal degeneration in A3C mice could be alleviated by rearing animals in darkness. After weaning (P20), A3C mice were maintained in light-protected cabinets until the age of 4 mo, at which point their retinal morphology was examined. Dark rearing seemed to prevent A3C retinas from degeneration, because the ONL thickness of dark-reared A3C mice at 4 mo was ∼46 μm, unlike the ONL thickness of the A3C mice maintained in a normal light/dark cycle (Fig. 2D).

Transducin Translocation Desensitizes Rod Phototransduction.

We examined the functional consequences of impaired transducin translocation in mouse rods. Dark-adapted rods of control and A3C mice displayed similar sensitivity, which is in good agreement with previous studies (20–22). The rising phases of dim flash responses were similar in dark-adapted control and A3C rods, with A3C rods displaying a modestly slowed recovery to baseline. An additional membrane restraint of Gαt1A3C by the palmitoyl anchor may preclude an optimal interaction and inactivation of the Gαt1A3C/PDE6 complex by the regulator of G protein signaling 9 (RGS9) GTPase-accelerating protein (GAP) complex. The times to peak of dim flash responses in control and A3C rods were statistically indistinguishable (Table 1), and the calculated amplification constant for phototransduction was also statistically indistinguishable (Fig. S7) (4, 23), indicating that dark-adapted phototransduction was relatively normal in both genotypes.

Table 1.

Response characteristics of control and A3C rods and rod bipolar cells

| Imax (pA)* | I1/2 (R*/rod) | TTP (ms)† or Hill exponent (n) | τrec (ms) | |

| Rods | ||||

| Control DA | 17 ± 1.6 (5) | 10 ± 0.7 (6) | 240 ± 15 (507) | 220 ± 23 (6) |

| Control LA | 15 ± 1.3 (8) | 80 ± 2.8 (3) | 190 ± 12 (597) | 150 ± 11 (3) |

| A3C DA | 20 ± 1.5 (7) | 11 ± 1.2 (3) | 280 ± 15 (986) | 410 ± 43 (3) |

| A3C LA | 22 ± 0.9 (7) | 17 ± 1.3 (5) | 280 ± 12 (457) | 420 ± 39 (5) |

| Rod bipolar cells | ||||

| Control DA | 480 ± 60 (6) | 2.8 ± 0.3 (6) | 1.7 ± 0.1 (6)‡ | |

| Control LA | 130 ± 31 (7) | 4.6 ± 0.3 (7) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (7)‡ | |

| A3C DA | 280 ± 53 (7) | 2.3 ± 0.3 (7) | 1.6 ± 0.1 (7)‡ | |

| A3C LA | 90 ± 24 (6) | 7.5 ± 0.8 (6) | 1.2 ± 0.1 (6)‡ |

DA, dark-adapted; Imax, light-evoked dark current; I1/2, half-maximal flash strength; LA, light-adapted; n, best fit Hill equation to the respective intensity–response curves; τrec, time constant describing the exponential that fits the decay of the dim flash response; TTP, time to peak of the dim flash response.

All results are presented as mean ± SEM (n cells).

TTP for rod dim flash responses are presented as mean ± SEM (number of trials).

Hill exponent.

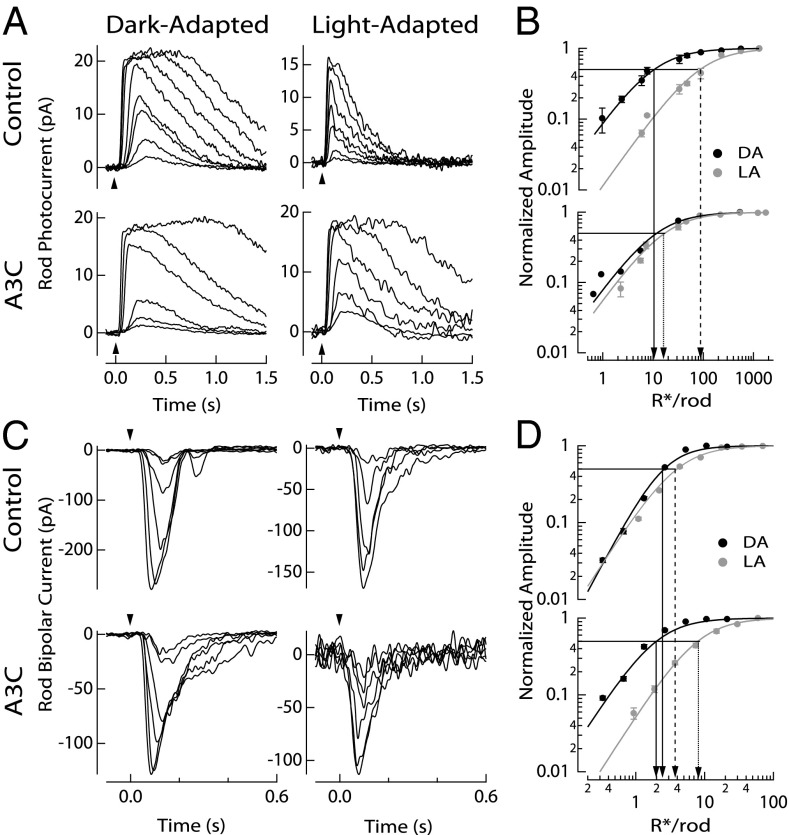

After the translocation protocol (Materials and Methods and SI Text), control mice displayed adapted rod photoresponses with reduced sensitivity and shorter times-to-peak and recovery time constants (Fig. 3 and Fig. S7). The amplification constant for phototransduction under these conditions was reduced by fivefold compared with darkness, which is similar to the findings in a previous work (4). This reduction in sensitivity can be attributed to both a lowered gain of signaling caused by reduced transducin presence in the OS (4) and desensitization as expected for partially bleached rods (24) (Materials and Methods and SI Text). However, A3C rods displayed little change in sensitivity after the translocation protocol and were approximately fivefold more sensitive compared with control rods (Fig. 3). In addition, the A3C rod amplification constant was reduced by 1.8 fold, a lesser extent than for control rods (Fig. S7). Furthermore, A3C rods did not display accelerated response kinetics in the dim flash response, which was observed in control rods (Fig. S7). This lack of desensitization presumably results from both an absence of transducin translocation and perhaps, the inability of free opsin to activate A3C transducin (Discussion). Unfortunately, biochemical evaluation of Gαt1A3C activation by opsin does not seem feasible. The palmitoylated transducin was not extracted from the membrane (Fig. 1E), and hydroxylamine treatment to produce rod outer segment membranes with opsin only would cleave off the palmitoyl moiety. However, the observed changes in dim flash response kinetics and sensitivity after the translocation protocol are consistent with a role for transducin translocation in normal rod function and adaptation.

Fig. 3.

Dark- and light-adapted rod and rod bipolar cell responses in control and A3C mice. (A) Representative flash response families from control (Gαt1+/−) and A3C rods in the dark-adapted state and after the translocation protocol. Timing of the 30-ms flash is indicated by the arrowheads, and flash strengths ranged from 0.6 to 540 R*/rod for the dark-adapted state and from 2.3 to 1,700 R*/rod for the translocated state. (B) Response–intensity relationships for dark-adapted (DA; black) and translocated (LA; gray) rods from control (Upper) and A3C (Lower) mice. Normalized flash responses were plotted as a function of flash strength. Sensitivity was estimated from the half-maximal flash strength of the Hill curve indicated by arrows for each state and genotype (Table 1). Arrows are included to indicate the half-maximal flash strength, with a solid line denoting the half-maximal flash strength of DA control and A3C rods, a dashed line denoting the half-maximal flash strength of LA control rods, and a dotted line denoting the half-maximal flash strength of LA A3C rods. (C) Representative flash response families from the different rod bipolar cells. Timing of the 10-ms flash is indicated by arrowheads, and flash strengths ranged from 0.3 to 21 R*/rod for the dark-adapted state and from 1.0 to 70 R*/rod for the light-adapted, translocated state. (D) Response–intensity relationships for dark-adapted (DA; black) and translocated (LA; gray) rod bipolar cells from control (Upper) and A3C (Lower) mice. Normalized flash responses were plotted as a function of flash strength. Sensitivity was estimated from the half-maximal flash strength of the Hill curve, which is indicated by arrows for each state and genotype (Table 1). Arrows are also included to indicate the half-maximal flash strength for comparison with rods. Solid lines denote the half-maximal flash strength of DA control and A3C rod bipolar cells, a dashed line denotes the half-maximal flash strength of LA control rod bipolar cells, and a dotted line denotes the half-maximal flash strength of LA A3C rod bipolar cells. Note the reversed position of the dashed and dotted lines in B and D. All records were sampled at 1 kHz and low pass-filtered at 50 Hz.

Transducin Translocation Enhances Signal Transmission to Rod Bipolar Cells.

In mammalian retinas, the glutamate release from rods is sensed primarily by a subclass of ON bipolar cells called rod bipolar cells (18). Dark-adapted rod bipolar cells of control and A3C mice displayed similar sensitivity (Fig. 3), which is in good agreement with previous studies (22, 25). Surprisingly, after the translocation protocol, there was a relatively minor (∼1.6-fold) reduction in sensitivity of control rod bipolar cells from the fully dark-adapted state (Table 1). However, A3C rod bipolar cells displayed approximately threefold reduced sensitivity from the dark-adapted state, and thus, they were approximately twofold less sensitive than control rod bipolar cells under the same experimental conditions. It should be noted that A3C rods using the translocation protocol were approximately fivefold more sensitive than control rods. Thus, despite the reduction in the sensitivity of control rods produced by light-induced transducin translocation, control rod bipolar cells seem to retain greater sensitivity than A3C rod bipolar cells. The exclusive expression of Gαt1 and Gαt1A3C in rods and the reduced sensitivity of A3C rod bipolar cells together suggest that, under normal circumstances, light-translocated transducin enhances signal transmission from rods to rod bipolar cells.

Desensitization in A3C Rod Bipolar Cells Is Not Caused by Changes in Rod Membrane Properties.

The reduced sensitivity of light-adapted A3C rod bipolar cells, compared with control, indicates that, under normal circumstances, transducin translocation to the rod IS or spherule improves the sensitivity of signal transmission to rod bipolar cells. In principle, transducin translocation to rod IS and spherules may alter the functional properties of three classes of targets: (i) transducin may enhance IS voltage-sensitive conductances, such as Ih (26), that increase the rod hyperpolarization per absorbed photon, (ii) transducin translocation may alter the voltage sensitivity of CaV1.4 Ca2+ channels, thereby allowing a larger relative reduction in synaptic Ca2+ per absorbed photon, or (iii) absent an influence of transducin on IS or synaptic Ca2+ conductances, transducin may interact with the glutamate release machinery to produce a larger reduction in glutamate release per absorbed photon. We tested explicitly the first two possibilities to determine whether they could contribute to enhanced signal transmission to rod bipolar cells.

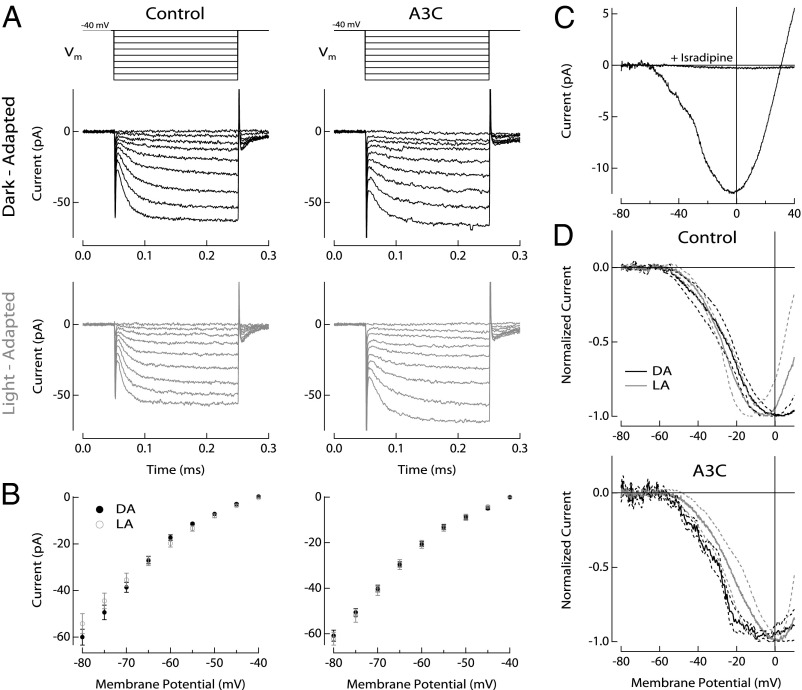

Rod IS currents were measured while varying the membrane potential. As shown in Fig. 4A, rods were held at a resting membrane potential of Vm = −40 mV and stepped for 200 ms to hyperpolarizing potentials in 5-mV increments to Vm = −80 mV. Such hyperpolarizing steps are representative of variations in the rod membrane potential during the light-evoked response (27). In addition, the duration of the voltage step exceeded the normal time to peak of the downstream rod bipolar cell light-evoked response. The current at steady state was plotted against the membrane potential in the dark-adapted rods using the translocation protocol for control (Fig. 4B, Left) and A3C mice (Fig. 4B, Right). We found that, in both control and A3C rods, the currents evoked by hyperpolarizing steps in membrane potential were statistically indistinguishable. Thus, light-induced transducin translocation does not seem to significantly influence rod IS conductances that shape the rod’s voltage response.

Fig. 4.

Dark- and light-adapted inner segment and synaptic conductances of control and A3C rods. (A) Rods were held at Vm = −40 mV and stepped for 200 ms to hyperpolarizing potentials in 5-mV increments up to Vm = −80 mV as shown in Upper. Representative voltage step families from rods of dark-adapted (black) and translocated (gray) control and A3C mice, respectively, are shown. Currents were sampled at 10 kHz and low pass-filtered at 300 Hz. (B) The measured inner segment membrane current is plotted as a function of the membrane potential for control and A3C rods. The control plot is an average of six dark- (black) and nine light-adapted (gray) rods. The A3C plot is an average of 9 dark- (black) and 10 light-adapted (gray) rods. Data are plotted as the mean ± SEM. (C) The Ca2+ current was measured by ramping the rod’s membrane potential between −80 and +40 mV over 1,000 ms. The synaptic Ca2+ current was isolated while blocking other membrane conductances with cesium-containing electrode internal solution (SI Text). The leak-subtracted Ca2+ current is an average from five cells. The Ca2+ current was blocked totally by 10 μM isradipine. (D) Leak-subtracted Ca2+ currents are plotted from dark-adapted (black) and translocated (gray) control and A3C rods. The control plot is an average of three dark- (black) and five light-adapted (gray) rods. The A3C plot is an average of five dark- (black) and five light-adapted (gray) rods. Data are plotted as the mean with 1 SD boundary. Calculations of the Ca2+ current density in the rod physiological voltage range (−80 to −40 mV) were 250 ± 78 pA2 in dark-adapted control rods (mean ± SEM, n = 3), 180 ± 36 pA2 in light-adapted control rods (mean ± SEM, n = 4), 170 ± 62 pA2 in dark-adapted A3C rods (mean ± SEM, n = 5), and 200 ± 33 pA2 in light-adapted A3C rods (mean ± SEM, n = 4).

Synaptic transmission from rods to rod bipolar cells can also be modulated through the tuning of the voltage sensitivity of CaV1.4 Ca2+ channels (28). The increased sensitivity of control rod bipolar cells might then be produced by a shift of the voltage sensitivity to hyperpolarized membrane potentials, which would enhance Ca2+ influx. We measured the voltage sensitivity of the synaptic Ca2+ current by ramping the membrane potential of rods and measuring the resulting current (Materials and Methods and SI Text). The recording conditions isolate appropriately the Ca2+ current, which is blocked completely by the selective inhibitor isradipine (29) (Fig. 4C). Measurements of the Ca2+ current from control or A3C rods in the dark-adapted state or after light-induced transducin translocation display a similar shape of the voltage dependence (and thus, a similar Ca2+ conductance) and no significant shift in voltage sensitivity, especially in the physiological range of rod voltages (Fig. 4D). In addition, the Ca2+ charge transfer, taken as the integral of the current response between −80 and −40 mV, was not significantly different in control or A3C mice under dark- or light-adapted conditions. Thus, light-induced transducin translocation does not seem to influence significantly Ca2+ influx to rod spherules.

Discussion

A feature of synapses is their ability to adjust strength in an activity-dependent manner. Such regulation is common in the visual system and responsible for the wide range of light intensities that it encodes. Here, we studied the role of transducin translocation in regulating the functional output of rod photoreceptors. Specifically, based on the diffusion model of light-dependent translocation (10, 12, 13), we have developed a transgenic mouse model where native rod transducin has been replaced with a mutant transducin, which displays impaired translocation. Analysis of retinal architecture and signal transmission in transgenic mice reveals that impaired translocation caused a slow light-dependent retinal degeneration and also impaired signal transmission to rod bipolar cells.

Additional Lipidation of Transducin-α Hinders Light-Evoked Translocation.

The RAC assay indicated that at least 40% of Gαt1A3C in transgenic rods is palmitoylated. Palmitoylation of Gαt1A3C apparently occurs in the IS, because most protein acyltransferases (Asp-His-His-Cys protein family) are localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi (30). Thus, Gαt1A3C is not fully palmitoylated in the IS or perhaps, is slowly depalmitoylated in the OS (31). Gαi and Gαo are largely depalmitoylated during purification (32). In view of the labile nature of the thioester linkage of S-acylation, the extent of Gαt1A3C palmitoylation in intact rods might be greater than the estimate from the RAC assay. Palmitoylated Gαt1A3C resisted extraction from the membranes with isotonic buffer containing GTPγS, confirming our prediction that the dual lipidation, N-acylation and S-palmitoylation, would firmly anchor the protein to the membrane. Although palmitoylation of Gα subunits has been reported to target G proteins to lipid rafts (33), only a small fraction of Gαt1A3C was found in the Triton-100 insoluble fraction. Palmitoylation of Gαt1A3C did not interfere with proper trafficking of transducin, which was localized to the OS in dark-adapted A3C mice. More importantly, light-dependent transducin translocation in A3C mice was noticeably impaired, apparently because of tight association of the palmitoylated Gαt1A3C with the disk membrane (Fig. 2 A and B). Translocations of both Gαt1A3C and Gβ1γ1 were deficient in mutant mice. The requirement of Gαt1 translocation for efficient redistribution of Gβ1γ1 in light-adapted rods is consistent with the sink model, where Gαt1 and Gβ1γ1 accumulate in the IS by forming a heterotrimer in the absence of R*-dependent activation (12).

Light-Evoked Transducin Translocation Promotes Rod Survival.

Interestingly, A3C mice develop photoreceptor degeneration under conditions of a 12/12-h light/dark cycle with modest light intensities of ∼100–200 lx (Fig. 2C and Fig. S6). These light conditions, nonetheless, are sufficient to trigger transducin translocation in WT rods (6, 15, 34). Dark rearing protected A3C mice from retinal degeneration, indicating that this photoreceptor death is light-dependent. Our results suggest two plausible reasons for the retinal degeneration, both of which lead to persistent high phototransduction gain in A3C rods. First, normal light-induced transducin translocation correlates with a reduction in the gain of phototransduction (4). Therefore, preventing light-induced transducin translocation would be expected to maintain a high gain of phototransduction, a hallmark of dark-adapted rods. Second, our recordings of A3C rod photocurrents reveal that little desensitization/adaptation is observed using the translocation protocol, which leads to a residual 35% bleached visual pigment (Materials and Methods and SI Text). It is well known that, after visual pigment bleaching in both amphibian and mammalian rods, the sensitivity of phototransduction is reduced because of the sum of the loss of quantum catch and residual phototransduction activity produced by free opsin (24, 35). The relatively minor desensitization of A3C rods using the translocation protocol (Fig. 3B) can be explained by the loss of quantum catch alone and thus, suggests that free opsin is unable to activate A3C transducin. This presumed lack of bleaching adaptation would also prevent a reduction in phototransduction gain. Taken together, the lack of transducin translocation and lack of bleaching adaptation would cause the overactivation of phototransduction in bright light and perhaps, the resulting retinal degeneration (8).

Light-Evoked Transducin Translocation Enhances Signal Transmission from Rods to Rod Bipolar Cells.

The dark-adapted sensitivities of both rods and rod bipolar cells were similar in control and A3C mice, which was expected based on the similar concentration of the G protein in both strains and the similar ability of Gαt1 and Gαt1A3C to be activated by R*. However, using the translocation protocol, we find substantial differences between control and A3C mice. The rods of A3C mice retained fivefold greater sensitivity under these conditions compared with control rods, but the A3C rod bipolar cells displayed twofold reduced sensitivity compared with control rod bipolar cells. This reversal indicates that the light-induced translocation of transducin has an influence downstream of the rod OS to increase the sensitivity of signal transmission.

Given the specific expression of Gαt1 and Gαt1A3C in rod photoreceptors and given that the dark-adapted sensitivity of control and A3C rods and rod bipolar cells is indistinguishable (Fig. 3), the lack of a major influence of Gαt on IS and synaptic currents (Fig. 4) is suggestive of a presynaptic interaction of transducin with the synaptic machinery. Although the exact nature of this interaction remains unclear, there is considerable evidence that shows G protein-coupled receptor signaling actively regulates of synaptic transmission in the CNS (36). Both Gαt1 and Gβ1γ1 translocate to the rod spherule in bright light, where they may form a heterotrimer. However, dissociated Gαt1 and Gβ1γ1 species can be generated in the spherule through the Gαt1 interaction with its protein partner UNC119 (37–39). Thus, in principle, either of these proteins may mediate the observed effect on signal transmission. For example, Gβ1γ1 has been shown to inhibit neurotransmitter release through direct interactions with the SNARE complex (40). Specifically, Gβ1γ1 and synaptotagmin have been shown to compete for binding to SNAP25, syntaxin1A, and the ternary SNARE complex in a Ca2+-dependent manner. The SNARE complexes in central and ribbon synapses are thought to comprise of homologous proteins (41). Thus, the light-induced decrease in intracellular Ca2+ in the rod spherule might augment the inhibitory action of Gβ1γ1 on the SNARE proteins and facilitate the reduction in glutamate release. An alternative mechanism for transducin’s synaptic sensitization may involve a direct action of Gαt1 with UNC119, a partner for the synaptic ribbon protein RIBEYE (42). The exact mechanisms of transducin modulation of rod-to-rod bipolar cell signal transmission will require additional investigation.

Thus, the light-dependent translocation of transducin in rods seems to provide adaptive changes to the rod photoresponse to facilitate light adaptation, which is not seen in A3C mice. Such a mechanism might protect rods from excessive stimulation under conditions where there is substantial free opsin in the OS. Additionally, transducin-dependent sensitization of signal transmission may, in turn, allow a larger part of the dynamic range of rod bipolar cells to be used under conditions where the rod photocurrent would be strongly desensitized. These direct demonstrations show the role of transducin translocation in the adaptation of rods and rod bipolar cells to background light.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Mice.

Transgenic mice with impaired transducin translocation were generated through the inclusion of an additional posttranslational modification to Gαt1. A site-directed mutation was made to transducin-α (Fig. 1A), which created the N-terminal S-palmitoylation site akin to the site present in Gαi/Gαo (43). The procedures used to generate A3C mice are well-established and described fully in SI Text.

Immunohistochemistry and Biochemistry.

The procedures used for immunoblotting, immunofluorescence and retina morphology analyses, transducin extraction, G-protein palmitoylation, and rhodopsin regeneration assays are well-established and described fully in SI Text.

Physiological Recording from Rods and Rod Bipolar Cells.

Rod photocurrents were measured using suction electrodes, and rod bipolar cell currents were measured using patch electrodes and methods described previously (SI Text). Voltage-dependent currents and the voltage sensitivity of Ca2+ currents in rods were measured with patch clamp electrodes from the rod inner segment in retinal slices. Experiments to measure voltage-dependent currents (Fig. 4 A and B) were performed using a K-Aspartate internal solution (SI Text), but the measurements of the voltage sensitivity of the synaptic Ca2+ current (Fig. 4 C and D) were made using a pipette internal solution that blocked other cationic currents (SI Text).

Light-Induced Transducin Translocation Protocols.

All experiments were performed on mice dark-adapted overnight or mice that, after dark adaptation, were exposed to light bright enough to cause transducin translocation. In biochemical and immunohistological experiments, dark-adapted mice were subjected to 500 lx light for 45 min after eye dilation (1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride) and euthanized according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa (Protocol 1005089).

In physiological experiments, the 500 lx light exposure was followed by a 30-min period of dark adaptation to ensure some visual pigment regeneration and recovery of visual sensitivity. This light exposure variation is also called the translocation protocol, and the preparation is referred to as light-adapted. The visual pigment regenerated to ∼65% of its dark-adapted level under these conditions (SI Text). Recordings were always halted at 1 h using the translocation protocol to ensure that Gαt remained substantially in the rod IS during the recordings (4). Mice used for physiological recordings were between 2 and 3 mo of age (before the onset of rod degeneration). Mice were euthanized in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Southern California (Protocol 10890).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Amy Lee for helpful comments on the manuscript. We also thank Dr. S. Thompson for providing access to custom-built light-protected cabinets for dark rearing of mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY17035 (to V.R.), EY17606 (to A.P.S.), and EY12682 (to N.O.A.) and the McKnight Endowment Fund for Neuroscience (A.P.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1222666110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brann MR, Cohen LV. Diurnal expression of transducin mRNA and translocation of transducin in rods of rat retina. Science. 1987;235(4788):585–587. doi: 10.1126/science.3101175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philp NJ, Chang W, Long K. Light-stimulated protein movement in rod photoreceptor cells of the rat retina. FEBS Lett. 1987;225(1-2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelan JP, McGinnis JF. Light-dependent subcellular movement of photoreceptor proteins. J Neurosci Res. 1988;20(2):263–270. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490200216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokolov M, et al. Massive light-driven translocation of transducin between the two major compartments of rod cells: A novel mechanism of light adaptation. Neuron. 2002;34(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strissel KJ, et al. Recoverin undergoes light-dependent intracellular translocation in rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(32):29250–29255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobanova ES, et al. Transducin translocation in rods is triggered by saturation of the GTPase-activating complex. J Neurosci. 2007;27(5):1151–1160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5010-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arshavsky VY, Burns ME. Photoreceptor signaling: Supporting vision across a wide range of light intensities. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(3):1620–1626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.305243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fain GL. Why photoreceptors die (and why they don’t) Bioessays. 2006;28(4):344–354. doi: 10.1002/bies.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng YW, Zallocchi M, Wang WM, Delimont D, Cosgrove D. Moderate light-induced degeneration of rod photoreceptors with delayed transducin translocation in shaker1 mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):6421–6427. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvert PD, Strissel KJ, Schiesser WE, Pugh EN, Jr, Arshavsky VY. Light-driven translocation of signaling proteins in vertebrate photoreceptors. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16(11):560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrmann R, et al. Phosducin regulates transmission at the photoreceptor-to-ON-bipolar cell synapse. J Neurosci. 2010;30(9):3239–3253. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4775-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Artemyev NO. Light-dependent compartmentalization of transducin in rod photoreceptors. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;37(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slepak VZ, Hurley JB. Mechanism of light-induced translocation of arrestin and transducin in photoreceptors: Interaction-restricted diffusion. IUBMB Life. 2008;60(1):2–9. doi: 10.1002/iub.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerov V, Artemyev NO. Diffusion and light-dependent compartmentalization of transducin. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46(1):340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerov V, et al. Transducin activation state controls its light-dependent translocation in rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(49):41069–41076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moussaif M, et al. Phototransduction in a transgenic mouse model of Nougaret night blindness. J Neurosci. 2006;26(25):6863–6872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1322-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvert PD, et al. Phototransduction in transgenic mice after targeted deletion of the rod transducin alpha -subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(25):13913–13918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250478897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sokolov M, et al. Phosducin facilitates light-driven transducin translocation in rod photoreceptors. Evidence from the phosducin knockout mouse. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):19149–19156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forrester MT, et al. Site-specific analysis of protein S-acylation by resin-assisted capture. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(2):393–398. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampath AP, et al. Recoverin improves rod-mediated vision by enhancing signal transmission in the mouse retina. Neuron. 2005;46(3):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn FA, Doan T, Sampath AP, Rieke F. Controlling the gain of rod-mediated signals in the Mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26(15):3959–3970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5148-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okawa H, Pahlberg J, Rieke F, Birnbaumer L, Sampath AP. Coordinated control of sensitivity by two splice variants of Gα(o) in retinal ON bipolar cells. J Gen Physiol. 2010;136(4):443–454. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pugh EN, Jr, Lamb TD. Amplification and kinetics of the activation steps in phototransduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1141(2-3):111–149. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90038-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nymark S, Frederiksen R, Woodruff ML, Cornwall MC, Fain GL. Bleaching of mouse rods: Microspectrophotometry and suction-electrode recording. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 10):2353–2364. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.228627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao Y, et al. Regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS11 determine the onset of the light response in ON bipolar neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(20):7905–7910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202332109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fain GL, Quandt FN, Bastian BL, Gerschenfeld HM. Contribution of a caesium-sensitive conductance increase to the rod photoresponse. Nature. 1978;272(5652):466–469. doi: 10.1038/272467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okawa H, Sampath AP, Laughlin SB, Fain GL. ATP consumption by mammalian rod photoreceptors in darkness and in light. Curr Biol. 2008;18(24):1917–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haeseleer F, et al. Essential role of Ca2+-binding protein 4, a Cav1.4 channel regulator, in photoreceptor synaptic function. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(10):1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/nn1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koschak A, et al. Cav1.4alpha1 subunits can form slowly inactivating dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ channels lacking Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci. 2003;23(14):6041–6049. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-06041.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hang HC, Linder ME. Exploring protein lipidation with chemical biology. Chem Rev. 2011;111(10):6341–6358. doi: 10.1021/cr2001977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo W, Marsh-Armstrong N, Rattner A, Nathans J. An outer segment localization signal at the C terminus of the photoreceptor-specific retinol dehydrogenase. J Neurosci. 2004;24(11):2623–2632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5302-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross EM. Protein modification. Palmitoylation in G-protein signaling pathways. Curr Biol. 1995;5(2):107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levental I, Grzybek M, Simons K. Greasing their way: Lipid modifications determine protein association with membrane rafts. Biochemistry. 2010;49(30):6305–6316. doi: 10.1021/bi100882y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee KA, Nawrot M, Garwin GG, Saari JC, Hurley JB. Relationships among visual cycle retinoids, rhodopsin phosphorylation, and phototransduction in mouse eyes during light and dark adaptation. Biochemistry. 2010;49(11):2454–2463. doi: 10.1021/bi1001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornwall MC, Fain GL. Bleached pigment activates transduction in isolated rods of the salamander retina. J Physiol. 1994;480(Pt 2):261–279. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Betke KM, Wells CA, Hamm HE. GPCR mediated regulation of synaptic transmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;96(3):304–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, et al. UNC119 is required for G protein trafficking in sensory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(7):874–880. doi: 10.1038/nn.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gopalakrishna KN, et al. Interaction of transducin with uncoordinated 119 protein (UNC119): Implications for the model of transducin trafficking in rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(33):28954–28962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.268821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinha S, Majumder A, Belcastro M, Sokolov M, Artemyev NO. Expression and subcellular distribution of UNC119a, a protein partner of transducin α subunit in rod photoreceptors. Cell Signal. 2013;25(1):341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon EJ, Gerachshenko T, Spiegelberg BD, Alford S, Hamm HE. Gbetagamma interferes with Ca2+-dependent binding of synaptotagmin to the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(5):1210–1219. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramakrishnan NA, Drescher MJ, Drescher DG. The SNARE complex in neuronal and sensory cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;50(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alpadi K, et al. RIBEYE recruits Munc119, a mammalian ortholog of the Caenorhabditis elegans protein unc119, to synaptic ribbons of photoreceptor synapses. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(39):26461–26467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801625200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wedegaertner PB, Wilson PT, Bourne HR. Lipid modifications of trimeric G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(2):503–506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.