Abstract

There is discrepancy in the literature regarding the degree to which old age affects muscle bioenergetics. These discrepancies are likely influenced by several factors, including variations in physical activity (PA) and differences in the muscle group investigated. To test the hypothesis that age may affect muscles differently, we quantified oxidative capacity of tibialis anterior (TA) and vastus lateralis (VL) muscles in healthy, relatively sedentary younger (8 YW, 8 YM; 21–35 years) and older (8 OW, 8 OM; 65–80 years) adults. To investigate the effect of physical activity on muscle oxidative capacity in older adults, we compared older sedentary women to older women with mild-to-moderate mobility impairment and lower physical activity (OIW, n = 7), and older sedentary men with older active male runners (OAM, n = 6). Oxidative capacity was measured in vivo as the rate constant, kPCr, of postcontraction phosphocreatine recovery, obtained by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy following maximal isometric contractions. While kPCr was higher in TA of older than activity-matched younger adults (28%; p = 0.03), older adults had lower kPCr in VL (23%; p = 0.04). In OIW compared with OW, kPCr was lower in VL (~45%; p = 0.01), but not different in TA. In contrast, OAM had higher kPCr than OM (p = 0.03) in both TA (41%) and VL (54%). In older adults, moderate-to-vigorous PA was positively associated with kPCr in VL (r = 0.65, p < 0.001) and TA (r = 0.41, p = 0.03). Collectively, these results indicate that age-related changes in oxidative capacity vary markedly between locomotory muscles, and that altered PA behavior may play a role in these changes.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, bioenergetics, physical function, metabolism, aging, mitochondria

Introduction

Old age is accompanied by structural and functional changes of skeletal muscle that may lead to a diminished ability to perform activities of daily living. Because mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation plays an essential role in supplying adequate energy for cellular processes at rest and during work, muscle oxidative capacity may also limit the functional capacity of muscle during various tasks of daily living. While whole-body maximal oxygen consumption (V̇O2max) decreases with old age (Proctor and Joyner 1997), there are conflicting reports regarding the effects of old age on muscle oxidative capacity (Russ and Kent-Braun 2004).

Various measures are commonly used to provide an index of muscle oxidative capacity. Some studies using muscle biopsies have shown lower mitochondrial enzyme activities and respiratory rates in muscle from old compared with young humans (Cooper et al. 1992; Rooyackers et al. 1996; Short et al. 2005; Tonkonogi et al. 2003). These results are consistent with in vivo phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies showing lower oxidative capacity in vastus lateralis (VL) (Conley et al. 2000) and gastrocnemius (McCully et al. 1993) in older compared with younger adults. Together, this group of studies suggests that old age is associated with a diminished capacity for oxidative ATP production in skeletal muscle.

In contrast, other in vitro and in vivo studies indicate preserved muscle oxidative capacity in older individuals (Capel et al. 2005; Chilibeck et al. 1998; Chretien et al. 1998; Kent-Braun and Ng 2000; Lanza et al. 2005, 2007; Rasmussen et al. 2003; Rimbert et al. 2004). Rasmussen et al. (2003) and Rimbert et al. (2004) studied younger and older participants who were matched for habitual physical activity (PA) level by questionnaires, and found no evidence for reduced activities of several key enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation. These results are in agreement with several studies from our laboratory that have shown similar oxidative capacity, assessed by the rate of postcontraction phosphocreatine (PCr) recovery, in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle in younger and older individuals. Notably, in these studies, the younger and older groups were matched for comparable levels of habitual PA using accelerometry (Kent-Braun and Ng 2000; Lanza et al. 2005, 2007).

Work conducted by Brierley et al. (1996) and Barrientos et al. (1996) supports this notion suggesting that an age-related decrease in mitochondrial respiration rates may be secondary to a decline in habitual PA in older individuals. In general, PA level is lower in older adults (Davis and Fox 2007; Troiano et al. 2008), which constitutes a potential confounding factor in studies comparing muscle oxidative capacity in younger and older individuals (Russ and Kent-Braun 2004). In addition to a decrease in overall daily PA level, Troiano et al. (2008) reported an ~50% reduction in time spent in moderate- to vigorous-intensity PA (MVPA) in older (60– 69 years) adults compared with younger (20–29 years) adults. The effects of this behavioral change become particularly relevant when considering recent studies that have shown that time spent in MVPA is positively associated with oxidative capacity of VL (den Hoed et al. 2008; Larsen et al. 2009). Notably, in younger adults, minutes of daily MVPA was not associated with oxidative capacity of TA (Larsen et al. 2009). However, the impact of PA behavior on muscle oxidative capacity has not been thoroughly investigated in the context of old age.

It has long been understood that exercise training has a highly localized effect on muscle oxidative capacity (Gollnick et al. 1972). Therefore, differences between muscles in patterns of habitual use could explain some of the current discrepancies regarding the effects of old age on muscle oxidative capacity. In agreement with this idea, studies in humans (Houmard et al. 1998; Pastoris et al. 2000) and rats (Bass et al. 1975; Holloszy et al. 1991; Sanchez et al. 1983) have reported that age-related declines in oxidative enzyme activities vary across muscles. Holloszy et al. (1991) suggested that an age-related decline in physical activity would have a greater influence on the use of antigravity (i.e., weight-bearing) vs. non-antigravity muscles, which could provide an explanation for the differential effects of old age on oxidative enzyme capacities across muscles. Consistent with this notion, it is possible that altered PA behavior in aging will have greater influence on loading and habitual use of VL than TA (de Boer et al. 2008), a result that could lead to muscle-specific differences in oxidative capacity with old age.

To address the lack of clarity about age-related changes in muscle oxidative capacity, and to obtain information about the interactions between oxidative capacity, muscle group, and age, we measured habitual PA and oxidative capacity of TA and VL in vivo in relatively sedentary younger and older men and women. In addition, to explore the effects of differing levels of physical activity and physical function in older adults, we included a group of older women with early signs of mobility impairments and a group of older active men who ran a minimum of 15 miles per week. We hypothesized that (1) compared with younger adults of similar overall PA level, older adults would have similar oxidative capacity in TA but lower oxidative capacity in VL; (2) older women with mobility impairments would have lower oxidative capacity in both TA and VL compared with healthy, relatively sedentary older women; (3) highly active older men would exhibit higher oxidative capacity in TA and VL than healthy, sedentary older men; and (4) muscle oxidative capacity would be positively associated with PA behavior in VL but not in TA.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 45 nonsmoking men and women participated in this study: 32 relatively sedentary adults free from impairment, 7 older women with mobility deficits, and 6 older physically-active men. The participants were recruited via (i) our database for previous participants, (ii) flyers in public places (libraries, the university campus, senior centers, running events), and (iii) advertisements in local newspapers. All participants were screened for habitual PA and medical history via telephone interviews. The same inclusion criteria were used for the younger (between 21 and 35 years of age) and older (65–80 years) sedentary groups, such that no individual (i) performed more than 20 min of structured exercise, twice per week; (ii) had a history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, neurological disorders, or peripheral vascular disease; (iii) used anti-hypertensive, cardiac, or cholesterol- lowering medications; or (iv) had a history of pain or injury in the leg studied. Portions of these data (7 young women, 7 young men) have been reported previously (Larsen et al. 2009).

To begin to investigate how differing levels of PA and physical function may affect various aspects of muscle function in old age, we also studied a group of 7 community-dwelling older women with early signs of mobility impairments (OIW), and a group of 6 older active males (OAM) who ran a minimum of 15 miles per week. Volunteers aged 65–80 years were sought for both of these groups. Potential participants for the OIW group came in to the laboratory and were screened using the Short Performance Physical Battery consisting of (i) various balance tasks, (ii) measured habitual gait speed over 4 m, and (iii) time to complete 5 repeated chair rises (Guralnik et al. 1994). Each of the 4 components was scored (0–4 points; 4 = no impairment) and a summary score was calculated (0–12 points). Women qualified for the OIW group if they had a score of 8–10, which reflects moderate impairments in physical function and increased risk of future disability (Guralnik et al. 1995). The inclusion criteria for the OIW allowed individuals taking anti-hypertensives (not β-blockers) and cholesterol-lowering medications to participate in the study. One OIW was taking anti-hypertensive medications, 1 was taking cholesterol-lowering medications, and 2 were taking both of these.

For all older volunteers, written approval was obtained from each individual’s primary care physician prior to enrollment in the study. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the procedures approved by the Human Subjects Review Boards at the University of Massachusetts and Yale University School of Medicine, and conforming to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. After enrolment in the study, each participant completed 2 visits.

Physical function and habituation

The first session was conducted in the Muscle Physiology Laboratory at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Height and body mass were obtained and brachial and ankle blood pressures were measured while participants rested in a supine position. The ankle-to-brachial systolic blood pressure index was obtained as an indication of peripheral vascular disease. All participants, except 1 woman in the OIW group (ankle:brachial index = 0.87), had an ankle:brachial index > 1.0, which is indicative of healthy peripheral vasculature (McDermott et al. 2001).

Physical function was assessed using several standard, performance-based measures of mobility function. Participants were timed in their ability to perform 10 repeated sitto-stand transitions in a standardized chair. In addition, they were timed in their ability to ascend and descend a standard flight of stairs (8 steps), while keeping 1 foot on the ground at all times. Participants were allowed to practice each task. The stair ascent and descent were performed twice, and the fastest time was used for further analysis.

During the first session, participants also were familiarized with 2 contraction protocols: 1 for the dorsiflexor muscles and 1 for the knee extensor muscles. The setup for both protocols mimicked the arrangement used for the testing session at Yale University. Briefly, volunteers were positioned supine on a patient bed during both protocols. For the dorsiflexor (TA) protocol, the leg was straight and the foot was strapped to a custom-built foot plate with the ankle angle at 120° relative to the tibia with the knee straight (0° of flexion). The foot plate was connected to a strain gauge that allowed for measurement of maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVIC) of the dorsiflexor muscles. For the knee extensor (VL) protocol, the knee was fixed at ~35° of flexion and positioned over a custom-built apparatus with a built-in strain gauge. The foot was held down with a cushioned, inelastic strap placed over the ankle joint, which allowed for an isometric contraction of the knee extensor muscles. Each participant practiced a minimum of 3 baseline MVICs (3–5 s duration, 2 min recovery between each) to ensure that these contractions could be performed consistently. None of the participants had problems performing the contraction protocols or experienced knee pain during the contractions. Visual force feedback from a series of light-emitting diodes and verbal encouragement were provided during all contractions.

Following completion of the habituation, all participants were instructed in the use of the PA monitor. Participants wore a uniaxial accelerometer (model GT1M, Actigraph, LLC Pensacola, Fla., USA) at the waist for 7 consecutive days. Uniaxial accelerometry can have limitations in measuring activities with very low vertical accelerations (e.g., cycling). Therefore, during the initial screening process, all volunteers were asked about their regular activity routines, including activities such as walking, cycling, and swimming. None of our participants rode bikes or swam on a regular basis. For the same reason, we recruited runners (and not cyclists or swimmers) for the group of active older men. The volunteers were instructed to wear the accelerometer during all waking hours except during bathing, and to maintain their usual daily PA routines.

The accelerometer measures the accumulation of gravitational accelerations, referred to as “counts”, which were sampled continuously at 30 Hz and stored in 60-s epochs. We measured the sum of accelerometer counts over the course of the day, which represent total PA (PAcounts; counts·day−1), and total minutes of activity (PAmin; min·day−1) for which the participant was engaged in any type of PA. The activity data were imported into MATLAB and time spent in low-intensity PA (LPA; 1–1951 counts·min−1, ≤3 METS) and moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA; ≥1952 counts·min−1, >3 METS) were determined as per Freedson et al. (1998). A minimum of 10 h of accelerometer data per day were required in order for any particular day to be included in the analysis, and at least 4 complete days (3 weekdays and 1 weekend day) were required for inclusion of the subject’s activity data in the overall analyses, as this has been shown to provide >80% reliability (Matthews et al. 2002). All PA analyses were performed by the same investigator, using the objective criteria established a priori. In addition to the accelerometers, participants were given a daily activity log to complete, which provided a means for confirming periods of high and low activity. Accelerometer data from 1 YW was not included, as the established criteria for PA data were not met due to failure to comply with instructions.

Muscle metabolic measures

Volunteers were transported to the Magnetic Resonance Research Center at Yale University for the measurements of muscle oxidative capacity in vivo. This visit took place at least 48 h after the first session at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. For most participants, these 2 visits were separated by less than 7 days, but all participants completed the 2 visits within a 3-week period. During the Yale session, participants performed both the TA and VL contraction protocols in a 4.0 Tesla whole-body magnet (Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, Germany), while continuous measures of intracellular energy metabolites using phosphorus MRS were acquired. An advantage of the MRS measures is that they are volumetric, and therefore independent of muscle size. Analyses of all muscle metabolic measures were performed by the same investigator, using consistent procedures established a priori. No blinding was done for these analyses.

Because the VL test required adjustments to the patient bed in the magnet, the TA test was always done first. Participants were instructed to avoid strenuous PA and alcohol during the 24 h preceding this visit, and to abstain from caffeine for 6 h prior to testing. Approximately 4 h prior to testing, each participant consumed a standardized breakfast meal comprising 25% of estimated daily energy expenditure, based on the Harris–Benedict Equation and an activity factor of 1.3 (Harris and Benedict 1919).

Participants were positioned supine on the patient bed, with 1 leg secured to the non-magnetic exercise apparatus, as in the habituation session. For the TA test, a probe consisting of a 6-cm diameter proton surface coil and a 3 × 4 cm elliptical phosphorus surface coil was secured over the largest portion of the TA muscle. For the VL study, a probe housing a 9-cm diameter proton coil and a 6 × 8 cm elliptical phosphorus coil was positioned over the largest part of the VL muscle, verified by scout images in the 4T system. Five T1-weighted images were acquired in the axial plane to ensure optimal positioning of the muscle relative to the iso-center of the magnet. Magnetic field homogeneity of the sample volume was optimized by localized shimming on the proton signal from tissue water. For both TA and VL, free induction decays (FID) consisting of 2048 data points were acquired continuously with a repetition time of 2 s and a spectral width of 8000 Hz. A 125-µs hard pulse with a nominal 60° flip angle was used for excitation.

Each protocol consisted of a brief MVIC that was designed to deplete PCr to approximately 50% of resting levels without inducing acidosis. Based on previous work (Larsen et al. 2009), the duration of the contraction protocols was 16 s for the dorsiflexor muscles and 24 s for the knee extensor muscles. Prior to each of these contractions, participants practiced 2 brief MVICs (3–5 s duration, 2 min recovery between each). Because of technical issues with the spectrometer, MRS data in the VL of 2 OIW and 1 OW are missing.

Spectral analyses

Individual FIDs were averaged to yield temporal resolution of 1 min at rest, 4 s during the MVICs, 8 s during the initial 5 min of recovery, and 30 s during the last 5 min of recovery. The averaged FIDs were processed with 10 Hz exponential line broadening and zero-filled to 32k prior to Fourier transformation. The resulting spectra were phased manually, and peaks corresponding to PCr, Pi, and γ-ATP were fit using commercial software (NUTS software, Acorn NMR, Liver-more, Calif., USA). Intramuscular pH was determined based on the chemical shift of Pi relative to PCr (Moon and Richards 1973). Resting concentrations of phosphorus metabolites were calculated assuming that [PCr] + [Pi] = 42.5 mM (Harris et al. 1974). In a subset of 6 younger and 8 older participants, fully relaxed spectra (24 acquisitions, 30-s repetition time) were acquired to derive mean saturation correction factors for use in calculating metabolite concentrations.

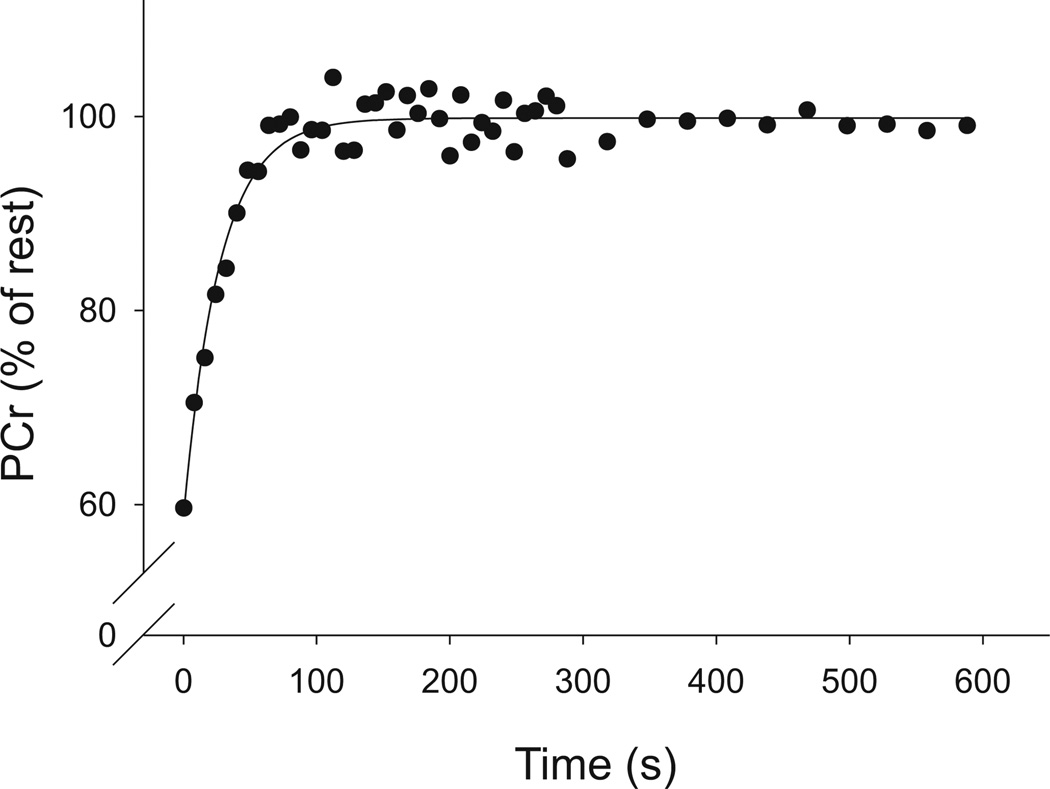

Calculation of oxidative ATP production

Oxidative capacity was determined from the postcontraction recovery kinetics of PCr. As long as any change in pH is small, the resynthesis of PCr follows a mono-exponential time course attributable to mitochondrial ATP production (Arnold et al. 1984; Meyer 1988; Quistorff et al. 1993). Recovery of PCr, from the end of the MVIC through 10 min of recovery, was fit with a single-exponential equation (Fig. 1), using Sigmaplot software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, Calif., USA):

| [1] |

where PCrend is the concentration of PCr at the end of the MVIC, and ΔPCr is the difference in PCr between rest and end of the MVIC. The theoretical maximal rate of oxidative ATP synthesis (Vmax) can be estimated as the product of the rate constant for PCr resynthesis (kPCr) and resting [PCr], using the following equation (Larsen et al. 2009;Meyer 1989):

| [2] |

whereVmax is in mM ATP·s−1,kPCr is in s−1 and [PCr]rest is in mM.

Fig. 1.

Recovery of PCr following contraction in 1 subject. Phosphocreatine (PCr, % of rest) recovered in an exponential manner following a 24-s maximal voluntary isometric contraction of vastus lateralis in a representative young male subject. Recovery data are fit with a mono-exponential equation. Under these conditions, the rate constant of this fit (kPCr) reflects the capacity of the muscle for oxidative ATP production in vivo.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., USA). Levene’s test for equal variances between or across groups was carried out prior to testing for group differences. When variances were equal, analyses comparing subject characteristics, PA, or metabolic measures in younger and older groups were analyzed with a 2- (age group, sex) or 3-factor (age group, sex, muscle) analysis of variance (ANOVA) using PROC MIXED with an unstructured covariance matrix on the repeated measures. A unique feature of the PROC MIXED test is that it handles missing data by using a set covariance structure. Specific comparisons were carried out within the repeated measures analysis using the SLICE option, which is a procedure that is used to evaluate significant interactions. In cases of equal variances for the comparisons between OW and OIW and between OM and OAM, analyses of subject characteristics, PA, and metabolic measures were each compared with unpaired t tests or a 2-factor (group, muscle) ANOVA using PROC MIXED.

If variances were unequal across groups, differences were tested using Welch’s test for equal means, with appropriate weighting for unequal variances. Differences between muscles within groups were analyzed using PROC UNIVARIATE, which performs parametric and nonparametric tests of a sample from a single population. Interactions were tested with a 1-way ANOVA on the differences between muscles for each variable.

Relationships between all PA variables and kPCr were evaluated by linear correlation analyses. Values are presented as means ± SD. Statistical significance was accepted when p ≤ 0.05; all relevant p values are provided.

Results

Subject characteristics and physical function

Characteristics for healthy younger and older participants are presented in Table 1. Men were heavier (p = 0.03) and taller than women (p < 0.001). There was an age-by-sex interaction such that young women were taller than old women (p = 0.02), and old men were taller than young men (p = 0.01). There were no effects of age or sex on body mass index (BMI). Systolic blood pressure was higher in older (125 ± 12 mm Hg) than younger (117 ± 11 mm Hg; p = 0.04) participants, whereas diastolic pressure and ankle:brachial index were similar between groups (data not shown). There were no differences in time to complete chair rises, stair ascent, or stair descent times between younger and older participants, although there was a trend for slower stair descent in the older group (p = 0.06). In addition, women had slower stair descent than men (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics, physical function, and physical activity for younger and older groups.

| Young |

Old |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 8) | Women (n = 8) | Men (n = 8) | Women (n = 8) | |

| Age (y)a | 24.8±3.5 | 27.0±3.1 | 68.9±3.9 | 69.4±2.4 |

| Height (cm)b,c | 176.2±3.8* | 170.2±5.4† | 182.5±5.9 | 164.1±3.4 |

| Body mass (kg)b | 80.6±15.6 | 73.9±18.9 | 78.1±7.6 | 63.6±7.1 |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 26.0±5.0 | 25.4±6.1 | 23.5±2.3 | 23.6±2.8 |

| Physical function | ||||

| Chair stands (s) | 15.6±4.1 | 14.4±3.0 | 15.9±3.3 | 15.5±3.3 |

| Stair ascent (s) | 2.9±0.3 | 3.2±0.3 | 3.1±0.5 | 3.3±0.5 |

| Stair descent (s)b | 2.6±0.3 | 2.8±0.3 | 2.7±0.4 | 3.3±0.7 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| PAcounts (counts·d−1·1000−1) | 246±92 | 192±55 | 227±86 | 208±61 |

| PAmin (min·d−1)a | 454±97 | 418±86 | 484±83 | 504±52 |

| LPA (min·d−1)a | 420±91 | 393±87 | 463±79 | 486±52 |

| MVPA (min·d−1) | 33.4±14.9 | 24.4±12.8 | 21.1±12.8 | 17.8±14.4 |

Note: Data are means ± SD. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) main effects of age

sex

age-by-sex interactions

are indicated. Significant differences between younger and older men

younger and older women

are also indicated.

BMI, body mass index; PAcounts, total daily physical activity counts; PAmin, total minutes of activity; LPA, low-intensity physical activity; MVPA, moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

Characteristics of OW and OIW are summarized in Table 2. The OIW group was older (p = 0.003) and heavier (p = 0.01) than the OW group. Time to complete each of the physical function tasks was significantly longer in OIW compared with YW and OW (p ≤ 0.003).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics, physical function, and physical activity for subgroups of older men and women.

| OW (n = 8) | OIW (n = 7) | OM (n = 8) | OAM (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)a | 69.4±2.4 | 75.6±3.7 | 68.9±3.9 | 69.3±5.3 |

| Height (cm) | 164.1±3.4 | 164.3±5.7 | 182.5±5.9 | 175.9±8.4 |

| Body mass (kg)a | 63.6±7.1 | 77.8±11.9 | 78.1±7.6 | 76.4±10.3 |

| BMI (kg·m−2)a | 23.6±2.8 | 28.8±4.2 | 23.5±2.3 | 24.8±3.3 |

| Physical function | ||||

| Chair stands (s)a | 15.5±3.3 | 28.1±5.4 | 15.9±3.3 | 14.1±2.4 |

| Stair ascent (s)a | 3.3±0.5 | 5.2±0.8 | 3.1±0.5 | 2.8±0.2 |

| Stair descent (s)a | 3.3±0.7 | 5.1±1.1 | 2.7±0.4 | 2.7±0.3 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| PAcounts (counts·d−1·1000−1)a,b | 208±61 | 117±33 | 227±86 | 410±92 |

| PAmin (min·d−1) | 504±52 | 481±60 | 484±83 | 480±73 |

| LPA (min·d−1) | 486±52 | 475±57 | 463±79 | 418±65 |

| MVPA (min·d−1)b | 17.8±14.4 | 5.9±9.0 | 21.1±12.8 | 61.5±20.5 |

Note: Data are means ± SD. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) differences between older women (OW) and older women women with mobility impairments (OIW)

and older men (OM) and older active men (OAM)

are indicated.

BMI, body mass index; PAcounts, total daily physical activity counts; PAmin, total minutes of activity; LPA, low-intensity physical activity; MVPA, moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

Characteristics of OM and OAM are presented in Table 2. There was no difference between OM and OAM in age (p = 0.86), height (p = 0.11), or body mass (p = 0.74). In addition, there were no differences in time to complete chair rises, stair ascent, or stair descent between these groups.

Physical activity

PA data for the younger and older groups are summarized in Table 1. For all comparisons, monitor wear time was not different between groups (data not shown). While total daily PA (PAcounts) was the same for the younger and older groups (217 vs. 217 counts·day−1·1000−1), other PA variables differed between groups. Specifically, total PA time (PAmin; p = 0.04), as well as time spent in LPA, was higher in older than younger (p = 0.02) participants. In contrast, minutes of MVPA tended to be higher in younger than older adults (p = 0.06). In general, the participants acquired MVPA through a number of different activities (e.g., hiking, dog-walking, garden work, walking to and from work or school).

Physical activity data for OW and OIW are summarized in Table 2. While PAcounts were lower in OIW compared with OW (p = 0.004), minutes of LPA (p = 0.68), MVPA (p = 0.08), and PAmin (p = 0.43) were not different between groups.

Physical activity data for OM and OAM are presented in Table 2. PAcounts (p = 0.004) and MVPA (p < 0.001) were higher in OAM than in OM, whereas PAmin (p = 0.93) and minutes of LPA (p = 0.29) were similar between groups.

Muscle oxidative capacity

There were no main effects nor interactions by sex for muscle metabolites, pH, or oxidative capacity. Therefore, data for the younger and older groups are collapsed by sex for simplicity of presentation (Table 3). Resting [PCr] was higher in TA than VL in the older adults (p = 0.003), and higher in younger compared with older participants in VL (p = 0.03). Intracellular pH at rest was lower in TA than VL (p < 0.001) with no effect of age. The MVICs induced greater depletion of PCr in younger than older participants (p = 0.02) with no effect of muscle. Greater PCr depletion in younger compared with older adults suggests higher rates of ATP synthesis via the creatine kinase reaction in the younger adults during the contraction. At the end of the MVICs, intracellular pH was higher in the older than the younger participants (p = 0.005), and in VL than TA (p = 0.04). Minimum pH, which occurred during recovery, was lower in TA than VL (p = 0.003) with no effect of age (p = 0.07).

Table 3.

Muscle metabolic measures for younger and older groups.

| Tibialis anterior |

Vastus lateralis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young (n = 16) | Old (n = 16) | Young (n = 16) | Old (n = 15) | |

| PCr, rest (mM)c | 37.6±1.3 | 38.2±1.5* | 37.8±1.3 | 36.9±0.9 |

| pH, restb | 7.02±0.03 | 7.02±0.03 | 7.07±0.03 | 7.06±0.05 |

| PCr, end (%)a | 51.7±8.9 | 60.47±5.4 | 50.7±12.5 | 56.2±9.0 |

| pH, enda,b | 7.01±0.05 | 7.07±0.04 | 7.05±0.07 | 7.09±0.06 |

| pH, minb | 6.84±0.05 | 6.89±0.04 | 6.89±0.08 | 6.92±0.08 |

| kPCr (s−1)c | 0.023±0.006*,† | 0.030±0.010† | 0.029±0.008 | 0.024±0.006 |

| Vmax (mM ATP)c | 0.87±0.21*,† | 1.12±0.35† | 1.11±0.30* | 0.88±0.20 |

Note: Data are means ± SD. Overall, there was an age-by-muscle interaction for muscle oxidative capacity, such that kPCr and maximal rate of oxidative phosphorylation (Vmax) of tibialis anterior were higher in the older than the younger adults, and kPCr and Vmax of vastus lateralis were lower in the older than the younger adults. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) main effects of age

muscle

and age-by-muscle interactions

are indicated. Significant differences between muscles within a group

and differences between younger and older participants

within a muscle are indicated.

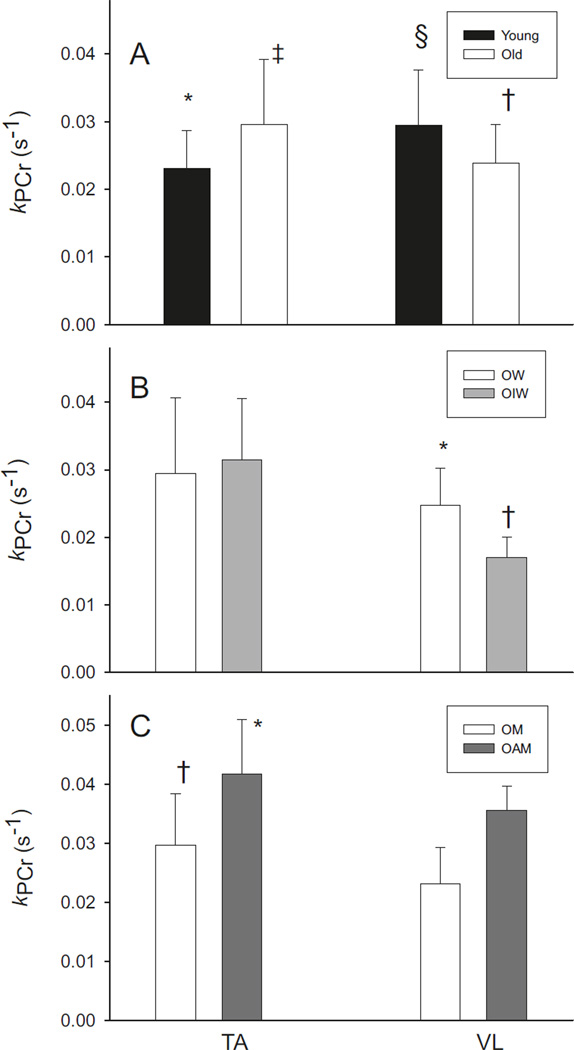

The rate constant for PCr recovery (kPCr) showed a muscle-by-age interaction (p = 0.003), such that kPCr in TA was higher in older than younger adults (p = 0.03), and kPCr in VL was higher in younger than older adults (p = 0.04, Table 3; Fig. 2A). The differences between age groups were ~28% in TA and ~23% in VL. Notably, in younger participants, kPCr was higher in VL than TA (p = 0.02), whereas the older participants showed a trend for higher kPCr in TA than VL (p = 0.06).

Fig. 2.

Muscle oxidative capacity in tibialis anterior (TA) and vastus lateralis (VL). (A) In younger adults (n = 16), kPCr was higher in VL than TA (*p = 0.02), while older adults (n = 16) had higher kPCr in TA than VL (†p = 0.04). Compared with younger participants, the older participants had higher kPCr in TA (‡p = 0.03), but lower kPCr in VL (§p = 0.04). (B) In VL, but not TA, kPCr was lower in older, physically-impaired women (OIW, n = 7) compared with older, unimpaired women (OW, n = 8; *p = 0.01). Additionally, kPCr of TA was higher than VL (†p = 0.01). (C) Older active men (OAM, n = 6) had higher kPCr than relatively sedentary older men (OM, n = 8) in both TA and VL (*p = 0.03), and kPCr was higher in TA than in VL (†p = 0.01). Data are means ± SD.

Consistent with the results for kPCr, the maximal rate of oxidative phosphorylation (Vmax) showed a muscle-by-age interaction (p = 0.001, Table 3). In TA, Vmax was higher in older than younger participants (p = 0.02), and Vmax in VL was higher in younger than older participants (p = 0.02). There were also differences between muscles within groups, such that younger adults had higher Vmax in VL than TA (p = 0.01), while older adults had higher Vmax in TA than VL (p = 0.03).

Muscle metabolic measures for OW and OIW are presented in Table 4. While PCr at rest was higher in TA than VL (p = 0.03), there were no differences between groups in PCr at rest or following the MVICs. Intracellular pH at rest and following the MVICs was not different between muscles or groups. Minimum pH during recovery was lower in TA than VL (p = 0.05), with no differences between OW and OIW. There were main effects of muscle for both kPCr and Vmax (Table 4 and Fig. 2B), such that both measures of oxidative capacity were higher in TA than VL (p ≤ 0.01). In addition, while kPCr and Vmax of TA were not different between groups, kPCr and Vmax of VL were lower in OIW compared with OW (p ≤ 0.02). Because of technical problems, MRS data from the VL of 2 OIW and 1 OW are missing. However, the oxidative capacity results were the same when the analyses were run without these 3 participants (i.e., oxidative capacity was lower in VL of OIW compared with OW and similar in TA, data not shown).

Table 4.

. Muscle metabolic measures for subgroups of healthy older women (OW) and older women with mobility impairments (OIW).

| Tibialis anterior |

Vastus lateralis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OW (n = 8) | OIW (n = 7) | OW (n = 7) | OIW (n = 5) | |

| PCr, rest (mM)a | 38.2±1.5 | 38.5±0.7 | 36.8±0.9 | 37.9±1.1 |

| pH, rest | 7.02±0.03 | 7.02±0.04 | 7.03±0.06 | 7.05±0.03 |

| PCr, end (%) | 61.1±4.3 | 58.3±9.0 | 55.9±13.5 | 59.5±12.3 |

| pH, end | 7.07±0.04 | 7.08±0.05 | 7.09±0.05 | 7.08±0.04 |

| pH, mina | 6.88±0.04 | 6.84±0.05 | 6.89±0.08 | 6.92±0.06 |

| kPCr (s−1)a,b | 0.029±0.011 | 0.032±0.009 | 0.025±0.005† | 0.017±0.003 |

| Vmax (mM ATP)a,b | 1.14±0.41 | 1.21±0.33 | 0.91±0.20† | 0.64±0.11 |

Note: Data are means ± SD. Overall, muscle oxidative capacity was higher in tibialis anterior than vastus lateralis, and kPCr and maximal rate of oxidative phosphorylation (Vmax) of vastus lateralis, but not tibialis anterior, were lower in OIW compared with OW. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) main effects of muscle

and group-by-muscle interactions

are indicated

as are differences between OW and OIW within a muscle

Muscle metabolic measures for OM and OAM are summarized in Table 5. At rest, PCr was higher in TA than VL (p < 0.001), with no difference between groups. At the end of the MVICs, PCr depletion was not different between groups or muscles. At rest, intracellular pH was lower in TA than VL (p < 0.001), with no differences between groups. Intracellular pH at the end of the MVICs, and minimum pH during recovery, were not different between groups or muscles. There were main effects of group and muscle for both kPCr and Vmax (Table 5 and Fig. 2C), such that kPCr and Vmax were higher in OAM than OM (p ≤ 0.03), and higher in TA than VL (p ≤ 0.01).

Table 5.

Muscle metabolic measures for subgroups of healthy older (OM) and active older men (OAM).

| Tibialis anterior |

Vastus lateralis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM (n = 8) | OAM (n = 6) | OM (n = 8) | OAM (n = 6) | |

| PCr, rest (mM)a | 38.4±1.3 | 38.5±0.9 | 37.0±0.9 | 36.8±1.2 |

| pH, resta | 7.03±0.02 | 7.03±0.03 | 7.07±0.02 | 7.06±0.03 |

| PCr, end (%) | 59.1.1±5.8 | 63.7±6.2 | 57.0±11.6 | 60.9±10.1 |

| pH, end | 7.07±0.04 | 7.08±0.04 | 7.09±0.07 | 7.11±0.04 |

| pH, min | 6.90±0.05 | 6.93±0.06 | 6.92±0.06 | 6.95±0.06 |

| kPCr (s−1)a,b | 0.030±0.009 | 0.042±0.014 | 0.023±0.006 | 0.036±0.012 |

| Vmax (mM ATP)a,b | 1.14±0.34 | 1.60±0.51 | 0.85±0.21 | 1.30±0.39 |

Note: Data are means ± SD. Overall, muscle oxidative capacity was higher in OAM than in OM, and kPCr and maximal rate of oxidative phosphorylation (Vmax) were higher in vastus lateralis than in tibialis anterior. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) main effect of muscle

and group

are indicated.

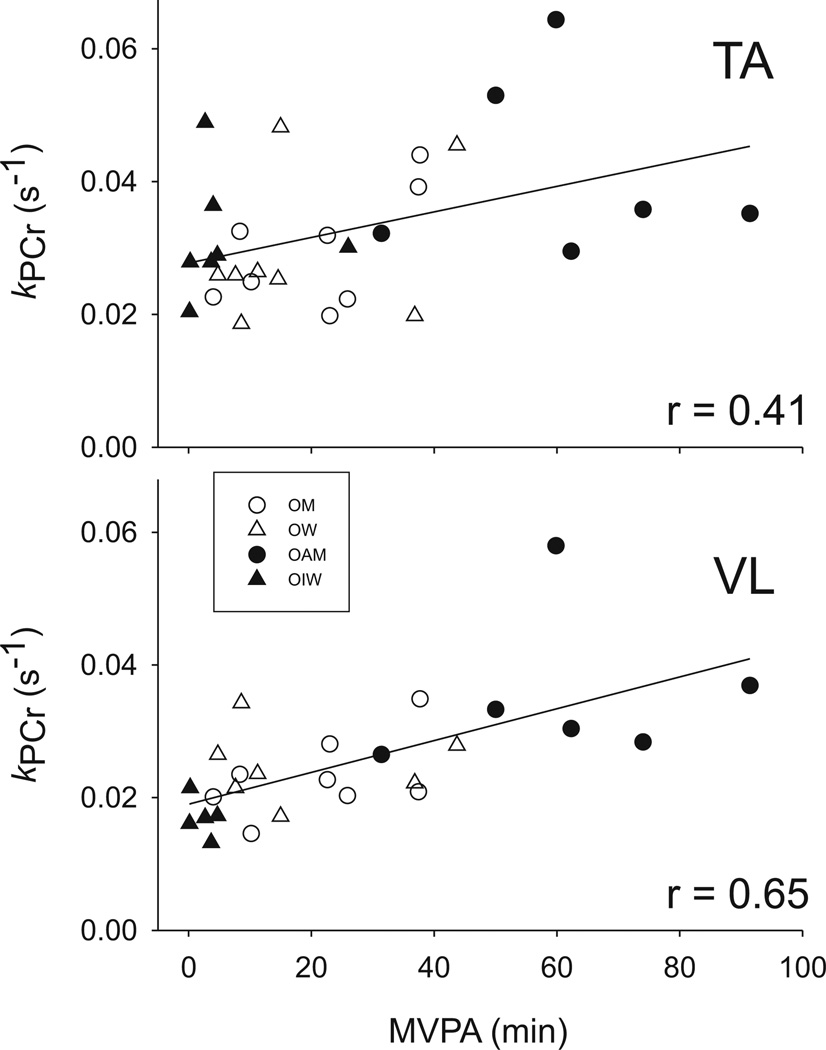

Associations between muscle oxidative capacity and physical activity behavior

For all subjects combined, VL kPCr was positively associated with PAcounts (r = 0.40, p = 0.01, n = 41) and MVPA (r = 0.57, p < 0.001, n = 41), but not LPA (r = 0.22, p = 0.16, n = 41) or PAmin (r = 0.01, p = 0.96, n = 41). In TA, kPCr was associated with PAcounts (r = 0.41, p = 0.01, n = 44) and PAmin (r = 0.35, p = 0.02, n = 44), but not LPA (r = 0.28, p = 0.07, n = 44) or MVPA (r = 0.27, p = 0.07, n = 44). Among the accelerometer variables, only PAcounts and MVPA were significantly correlated (r = 0.91, p < 0.001), which is consistent with the important role of MVPA in establishing daily PAcounts. Because of technical problems, MRS data from the VL of 2 OIW and 1 OW are missing from the correlation analyses for VL.

When data from only the older subjects were included in the correlation analyses, kPCr in VL remained strongly associated with PAcounts (r = 0.65, p < 0.001, n = 26) and MVPA (r = 0.65, p < 0.001, n = 26; Fig. 3). In addition, kPCr in TA became positively associated with PAcounts (r = 0.45, p = 0.01, n = 29) and MVPA (r = 0.41, p = 0.03, n = 29; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Associations between muscle oxidative capacity and daily minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) in older adults. There was a modest positive association between MVPA and kPCr in tibialis anterior (TA) (top panel, p = 0.03, n = 29), and a stronger association between MVPA and kPCr in vastus lateralis (VL) (bottom panel, p < 0.001, n = 26). Data from 2 OIW and 1 OW are missing for kPCr in the VL because of technical problems. OM, older healthy men; OW, older healthy women; OAM, older active men; OIW, older women with mobility impairments.

Discussion

The results of this study advance our understanding of age-related changes in muscle energetics by showing that the effects of old age on oxidative capacity in vivo vary between locomotory muscles, and likely depend to some extent on age-related changes in PA behavior. Older adults had higher capacity for oxidative ATP production in TA, but lower oxidative capacity in VL, compared with younger adults with similar overall PA levels. In addition, older women with early signs of mobility impairment and lower overall PA levels displayed similar oxidative capacity in TA, but lower oxidative capacity in VL, compared with healthy older women. In contrast, physically active older men had greater oxidative capacity than their sedentary counterparts in both the TA and VL. In comparing differences across muscles, within age groups, younger adults had higher oxidative capacity of VL than TA, while all older groups had higher oxidative capacity of TA than VL. Collectively, these results provide novel evidence of differences in oxidative capacity between distinct locomotory muscles in aged men and women. Further, there was a stronger association between daily minutes of MVPA and oxidative capacity in VL than in TA, suggesting that muscle-specific effects of old age on oxidative capacity in vivo may be influenced by age-related changes in habitual physical activity behavior.

Muscle oxidative capacity

Currently, there are discrepancies in the literature in terms of how old age may affect skeletal muscle bioenergetics. In the present study, we report a significant muscle-by-age interaction for oxidative capacity that was a result of greater oxidative capacity of the TA in older compared with activity-matched younger adults, while oxidative capacity of the VL was lower in the older group (Table 3, Fig. 2A). Thus, our results related to hypothesis 1 contribute to resolving the current controversy in the literature about age-related changes in muscle oxidative capacity by suggesting that some of these differences may have been due to differences in study populations (i.e., variable PA) and muscle groups (i.e., TA vs. VL).

Consistent with our results, biopsy studies in humans (Houmard et al. 1998; Pastoris et al. 2000) and animals (Bass et al. 1975; Holloszy et al. 1991; Sanchez et al. 1983) have provided some evidence that suggest that aging does not affect oxidative capacity equally in all skeletal muscles. Pastoris et al. (2000) reported reduced citrate synthase activity in VL, but similar citrate synthase activities in gluteus maximus and rectus abdominus in older compared with younger adults. However, interpretation of these earlier results was limited by the fact that muscle citrate synthase activities were not measured in the same individuals but rather in 3 separate groups of participants.

Previously, we and others have reported preserved muscle oxidative capacity in old age (Chilibeck et al. 1998; Kent- Braun and Ng 2000; Lanza et al. 2005, 2007; Rasmussen et al. 2003; Rimbert et al. 2004). While some of these studies suggested trends for higher oxidative capacity in older adults, the present study is the first report of higher oxidative capacity of TA in older compared with younger untrained adults of comparable habitual PA. Although this result may be somewhat surprising, it is in agreement with the results of Coggan et al. (1990), who compared oxidative enzyme activities in the lateral gastrocnemius of younger and older runners matched for 10 km performance time, as well as volume, pace, and intensity of training. Despite an ~11% lower V̇O2max, the older runners had higher activities of succinate dehydrogenase (~31%) and b-hydroxyacyl-CoA hydrogenase (~24%) compared with their younger counterparts. By assuming that the older runners were training and competing at a relatively higher exercise intensity (owing to a lower V̇O2max), the observation of higher oxidative enzyme activities was interpreted to be the result of a greater metabolic stress imposed on the older muscle, which could lead to larger metabolic adaptations and consequently higher oxidative capacity (Coggan et al. 1990). Thus, if younger and older humans are matched for PA, it is possible that some older muscles can exhibit greater oxidative capacity, as found here for the TA.

To be representative of aging individuals, we included both men and women in our primary analyses of younger and older healthy, relatively sedentary adults (Tables 1 and 3, Fig. 2A). Notably, this analysis indicated no sex-based difference in muscle oxidative capacity. This result is consistent with previous studies (Conley et al. 2000, Short et al. 2005, Lanza et al. 2007), but in contrast to some reports indicating lower mitochondrial capacity in women than men (Rooyackers et al. 1996, Karakelides et al. 2010). Karakelides et al. (2010) suggested that lower levels of mitochondrial ATP production rates in women compared with men could have been a consequence of lower levels of physical activity and (or) fitness in the women. Our relatively sedentary older men and women had similar levels of habitual PA, which could explain the discrepancy between our study and that of Karakelides et al. (2010). Alternatively, it is possible that our sample sizes did not allow us to detect subtle sex differences in muscle oxidative capacity. Overall, however, it appears from our data that potential sex-based differences in oxidative capacity are not a prominent feature in healthy, activity-matched adults.

We have shown previously that irrespective of training status, oxidative capacity is higher in VL than TA in young men and women (Larsen et al. 2009), which is consistent with studies of young adults, showing that oxidative capacity of TA is lower than oxidative capacities of other lower limb muscles (Forbes et al. 2009; Gregory et al. 2001). In contrast to the case for younger adults, the present study showed that groups of older adults with varying levels of PA all had higher oxidative capacity of TA than VL. Collectively, these results suggest muscle-specific effects of age on metabolic function. We propose that age-related changes in muscle use and activation patterns may contribute to these differences.

Muscle use and metabolic properties

Although both the TA and VL are important locomotory muscles, they are distinct from a functional and morphological perspective. Functionally, the respective activation and loading patterns of these muscles have been shown to differ significantly during locomotion. Cappellini and colleagues (2006) showed that activation of TA is relatively similar across a range of walking and running speeds, whereas VL activation increases much more as speed increases. Furthermore, a recent study showed that prolonged bed rest resulted in a reduction in muscle size of VL, but not TA, suggesting that antigravity vs. non-antigravity muscles are more susceptible to muscle remodeling in response to a decrease in physical activity level (de Boer et al. 2008). Along with different functional roles of the TA and VL muscles, VL is morphologically distinguished from TA (~76% type 1 fibers) by a relatively greater proportion of type II fibers in humans (~50%) (Grimby 1984; Jakobsson et al. 1988), which are innervated by higher-threshold motoneurons. Thus, maintenance of oxidative capacity in VL may be more dependent on higher intensity activities than are needed for the TA. This notion is consistent with the results from Dudley et al. (1982), who showed that the pattern of mitochondrial adaptations, following treadmill running in rats, varied across muscles. Specifically, changes in cytochrome C content of the white VL were highly dependent on running intensity, more so than in the red VL and soleus. Thus, the metabolic properties of various skeletal muscles are likely influenced by morphology and recruitment patterns during daily physical activities.

A number of investigators have begun to evaluate muscle activation patterns during mobility tasks in younger and older adults. Jakobsson et al. (1988) measured electromyography (EMG) activity of the TA during walking and found that muscle activity of the TA during heel strike, expressed relative to maximal EMG activity, was significantly higher in older (52%) than younger (37%) individuals. A study by DeVita and Hortobagyi (2000) measured joint torques during walking in healthy younger and older adults. The older group walked at the same speed as the younger group by producing the same support torque (i.e., sum of ankle, knee, and hip torques); however, the contribution from the knee extensors was smaller in the older group, suggesting less activation of the VL during walking in old age. Recently, a study of muscle activity using 9-h EMG recordings indicated a significant, positive association (r = 0.66, p < 0.001) between accelerometer measures of daily PA and VL activity in older women with a range of mobility function (Theou et al. 2010). Collectively, these studies suggest that an altered strategy for muscle activation during locomotion in older adults may contribute to the differential effects of old age on muscle oxidative capacities, as observed here. This hypothesis remains to be tested.

The importance of PA pattern on maintenance of oxidative capacity in locomotory muscles is suggested by our results from the subgroup comparisons. While our results and previous studies in older, exercise-trained individuals clearly demonstrate the beneficial effects of an active lifestyle on several indices of muscle oxidative capacity (Brierley et al. 1997; Lanza et al. 2008; Proctor et al. 1995), the extent to which low physical function and PA levels influence muscle oxidative capacity is less clear. By studying older women with early signs of mobility impairments who engage in minimal amounts of higher-intensity activities, we were able to further investigate the interplay between PA behavior and oxidative capacity in old age.

In contrast to our expectations (hypothesis 2), older women with early signs of mobility impairments (OIW) had preserved oxidative capacity in TA, but had a markedly lower (~45%) oxidative capacity in VL (Table 4; Fig. 2B). It is possible that these results were influenced by the fact that the OIW were ~6 years older than the OW group, and several of these women were on medications for hypertension or high cholesterol. However, despite these differences, oxidative capacity in TA was similar in both groups. Total PAmin and LPA were similar in OIW and OW, suggesting that low amounts of daily locomotion are sufficient to maintain oxidative capacity of TA. In contrast, the lower PAcounts and tendency for lower MVPA in the OIW suggest that higher intensity activities may be necessary to more fully activate VL and thus maintain its oxidative capacity in old age. While additional studies are needed to expand these observations to larger groups of mobility-impaired adults, these preliminary results may have important implications for PA behavior, particularly in aging women, who are at higher risk for mobility impairments than are older men (Janssen et al. 2002).

We also examined muscle oxidative capacity in older adults at the higher end of the PA spectrum (OAM). These results showed that in support of hypothesis 3, oxidative capacity was higher in both TA (~40%) and VL (~56%) in OAM compared with relatively sedentary OM (Table 5; Fig. 2C). Thus, it appears that both of these locomotory muscles may be responsive to a relatively high-intensity training stimulus in older men. Indeed, biopsy studies have shown increased capacity for mitochondrial ATP production in trained compared with untrained older adults in VL (Proctor et al. 1995; Lanza et al. 2008). Our study extends these results and provides novel evidence of higher in vivo oxidative capacity of 2 locomotory muscles in physically-active compared with relatively sedentary older men of similar age and health status (i.e., no medication or disease). This information may be useful in the design of interventions aimed at increasing mobility in older adults.

Associations between physical activity behavior and muscle oxidative capacity

Indeed, PA is important for maintaining several aspects of overall health. Based on the accelerometer data, we quantified the amount and intensity of habitual activities in our participants. In support of hypothesis 4, correlation analyses revealed that time spent in MVPA was positively associated with kPCr of VL in the older adults (Fig. 3), a result that is consistent with previous results in younger adults (den Hoed et al. 2008; Larsen et al. 2009). While there also emerged an association between MVPA and TA oxidative capacity in the older participants (Fig. 3), this association was not as strong (r = 0.41) as that for VL (r = 0.65). This difference between muscles was further distinguished when all study subjects (i.e., young and old) were included in the analysis. Notably, there were no associations between minutes of LPA and muscle oxidative capacity, which is in contrast to studies in young adults that have indicated the value of low-intensity PA in resisting weight gain (Levine et al. 1999) and maintaining metabolic health (Stephens et al. 2011). In sum, our results provide important new evidence of positive associations between habitual PA behavior and in vivo muscle oxidative capacity in older men and women.

Conclusions and significance

This study provides new information that addresses current discrepancies regarding the effects of old age on skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. This is the first study to show muscle-specific effects of old age on in vivo oxidative capacity in younger and older adults with comparable overall PA levels and to extend this finding in 2 locomotory muscles to an association with activity behavior in adults with a range of PA. These results suggest that interventions that directly address age-related changes in PA behavior, including decreased MVPA, may be needed to prevent loss of oxidative capacity in some muscles. We propose that changes in PA behavior in senescence contributed to the variation in muscle oxidative capacity observed here. The precise interactions between PA intensity and metabolic characteristics in distinct muscles and the mechanisms responsible for these interactions remain to be clarified.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants as well as the members of the Muscle Physiology Laboratory for help with various aspects of the project. We also wish to thank John Buonaccorsi, PhD, for expert statistical advice, and Douglas Befroy, PhD, for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH/NIA R01 AG21094, K02 AG023582, ACSM Student Grant (R.G.L.) and the Keck Foundation.

References

- Arnold DL, Matthews PM, Radda GK. Metabolic recovery after exercise and the assessment of mitochondrial function in vivo in human skeletal muscle by means of 31P NMR. Magn. Reson. Med. 1984;1(3):307–315. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010303. PMID:6571561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A, Casademont J, Rotig A, Miro O, Urbano-Marquez A, Rustin P, Cardellach F. Absence of relationship between the level of electron transport chain activities and aging in human skeletal muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;229(2):536–539. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1839. PMID:8954933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass A, Gutmann E, Hanzlikova V. Biochemical and histochemical changes in energy supply enzyme pattern of muscles of the rat during old age. Gerontologia. 1975;21(1):31–45. doi: 10.1159/000212028. PMID:166901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley EJ, Johnson MA, James OFW, Turnbull DM. Effects of physical activity and age on mitochondrial function. QJM. 1996;89(4):251–258. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.4.251. PMID:8733511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley EJ, Johnson MA, Bowman A, Ford GA, Subhan F, Reed JW, et al. Mitochondrial function in muscle from elderly athletes. Ann. Neurol. 1997;41(1):114–116. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410120. PMID:9005875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capel F, Rimbert V, Lioger D, Diot A, Rousset P, Mirand PP, et al. Due to reverse electron transfer, mitochondrial H2O2 release increases with age in human vastus lateralis muscle although oxidative capacity is preserved. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005;126(4):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.11.001. PMID:15722109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellini G, Ivanenko YP, Poppele RE, Lacquaniti F. Motor patterns in human walking and running. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;95(6):3426–3437. doi: 10.1152/jn.00081.2006. PMID:16554517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilibeck PD, Paterson DH, McCreary CR, Marsh GD, Cunningham DA, Thompson RT. The effects of age on kinetics of oxygen uptake and phosphocreatine in humans during exercise. Exp. Physiol. 1998;83(1):107–117. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004087. PMID:9483424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chretien D, Gallego J, Barrientos A, Casademont J, Cardellach F, Munnich A, et al. Biochemical parameters for the diagnosis of mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiency in humans, and their lack of age-related changes. Biochem. J. 1998;329(2):249–254. doi: 10.1042/bj3290249. PMID:9425106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan AR, Spina RJ, Rogers MA, King DS, Brown M, Nemeth PM, Holloszy JO. Histochemical and enzymatic characteristics of skeletal-muscle in master athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990;68(5):1896–1901. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.5.1896. PMID:2361892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Oxidative capacity and ageing in human muscle. J. Physiol. 2000;526(1):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00203.x. PMID:10878112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JM, Mann VM, Schapira AHV. Analyses of mitochondrial respiratory-chain function and mitochondrial-DNA deletion in human skeletal muscle - effect of aging. J. Neurol. Sci. 1992;113(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90270-u. PMID: 1469460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MG, Fox KR. Physical activity patterns assessed by accelerometry in older people. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;100(5):581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0320-8. PMID:17063361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer MD, Seynnes OR, di Prampero PE, Pisot R, Mekjavić IB, Biolo G, Narici MV. Effect of 5 weeks horizontal bed rest on human muscle thickness and architecture of weight bearing and non-weight bearing muscles. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104(2):401–407. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0703-0. PMID:18320207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hoed M, Hesselink MK, van Kranenburg GP, Westerterp KR. Habitual physical activity in daily life correlates positively with markers for mitochondrial capacity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;105(2):561–568. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00091.2008. PMID:18511526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita P, Hortobagyi T. Age increases the skeletal versus muscular component of lower extremity stiffness during stepping down. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000;55(12):B593–B600. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.b593. PMID:11129389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley GA, Abraham WM, Terjung RL. Influence of exercise intensity and duration on biochemical adaptations in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1982;53(4):844–850. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.4.844. PMID:6295989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SC, Slade JM, Francis RM, Meyer RA. Comparison of oxidative capacity among leg muscles in humans using gated 31P 2-D chemical shift imaging. NMR Biomed. 2009;22(10):1063–1071. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1413. PMID:19579230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. PMID:9588623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollnick PD, Armstrong RB, Saubert CW, IV,Piehl K, Saltin B. Enzyme activity and fiber composition in skeletal muscle of untrained and trained men. J. Appl. Physiol. 1972;33(3):312–319. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.3.312. PMID:4403464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory CM, Vandenborne K, Dudley GA. Metabolic enzymes and phenotypic expression among human locomotor muscles. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24(3):387–393. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200103)24:3<387::aid-mus1010>3.0.co;2-m. PMID:11353424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimby L. Firing properties of single human motor units during locomotion. J. Physiol. 1984;346:195–202. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015016. PMID:6699774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. PMID:8126356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332(9):556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. PMID:7838189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Benedict F. A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Washington D.C., USA: Carnegie Institute of Washington; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Harris RC, Hultman E, Nordesjo LO. Glycogen, glycolytic intermediates and high-energy phosphates determined in biopsy samples of musculus quadriceps femoris of man at rest. Methods and variance of values. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1974;33(2):109–120. PMID:4852173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO, Chen M, Cartee GD, Young JC. Skeletal muscle atrophy in old rats: differential changes in the three fiber types. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1991;60(2):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90131-i. PMID:1745075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard JA, Weidner ML, Gavigan KE, Tyndall GL, Hickey MS, Alshami A. Fiber type and citrate synthase activity in the human gastrocnemius and vastus lateralis with aging. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998;85(4):1337–1341. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1337. PMID:9760325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson F, Borg K, Edström L, Grimby L. Use of motor units in relation to muscle fiber type and size in man. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11(12):1211–1218. doi: 10.1002/mus.880111205. PMID:3070382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002;50(5):889–896. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50216.x. PMID:12028177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakelides H, Irving BA, Short KR, O’Brien P, Nair KS. Age, obesity, and sex effects on insulin sensitivity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Diabetes. 2010;59(1):89–97. doi: 10.2337/db09-0591. PMID:19833885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent-Braun JA, Ng AV. Skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in young and older women and men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;89(3):1072–1078. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1072. PMID:10956353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Befroy DE, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related changes in ATP-producing pathways in human skeletal muscle in vivo . J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;99(5):1736–1744. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00566.2005. PMID:16002769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Larsen RG, Kent-Braun JA. Effects of old age on human skeletal muscle energetics during fatiguing contractions with and without blood flow. J. Physiol. 2007;583(3):1093–1105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138362. PMID:17673506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Short DK, Short KR, Raghavakaimal S, Basu R, Joyner MJ, et al. Endurance exercise as a countermeasure for aging. Diabetes. 2008;57(11):2933–2942. doi: 10.2337/db08-0349. PMID:18716044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RG, Callahan DM, Foulis SA, Kent-Braun JA. In vivo oxidative capacity varies with muscle and training status in young adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;107(3):873–879. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00260.2009. PMID:19556459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JA, Eberhardt NL, Jensen MD. Role of nonexercise activity thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain in humans. Science. 1999;283(5399):212–214. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.212. PMID:9880251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews CE, Ainsworth BE, Thompson RW, Bassett DR., Jr Sources of variance in daily physical activity levels as measured by an accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002;34(8):1376–1381. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00021. PMID: 12165695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully KK, Fielding RA, Evans WJ, Leigh JS, Jr, Posner JD. Relationships between in-vivo and in-vitro measurements of metabolism in young and old human calf muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;75(2):813–819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.813. PMID:8226486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Dolan NC, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286(13):1599–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.13.1599. PMID:11585483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA. A linear model of muscle respiration explains monoexponential phosphocreatine changes. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;254(4):C548–C553. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.4.C548. PMID:3354652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA. Linear dependence of muscle phosphocreatine kinetics on total creatine content. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257(6):C1149–C1157. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.6.C1149. PMID:2610252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RB, Richards JH. Determination of intracellular pH by 31P magnetic resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248(20):7276–7278. PMID:4743524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastoris O, Boschi F, Verri M, Baiardi P, Felzani G, Vecchiet J, et al. The effects of aging on enzyme activities and metabolite concentrations in skeletal muscle from sedentary male and female subjects. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00077-7. PMID:10705043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Joyner MJ. Skeletal muscle mass and the reduction of VO2max in trained older subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997;82(5):1411–1415. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1411. PMID:9134886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Sinning WE, Walro JM, Sieck GC, Lemon PWR. Oxidative capacity of human muscle fiber types – effects of age and training status. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995;78(6):2033–2038. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.6.2033. PMID:7665396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistorff B, Johansen L, Sahlin K. Absence of phosphocreatine resynthesis in human calf muscle during ischaemic recovery. Biochem. J. 1993;291(3):681–686. doi: 10.1042/bj2910681. PMID: 8489495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen UF, Krustrup P, Kjaer M, Rasmussen HN. Experimental evidence against the mitochondrial theory of aging. A study of isolated human skeletal muscle mitochondria. Exp. Gerontol. 2003;38(8):877–886. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00092-5. PMID:12915209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimbert V, Boirie Y, Bedu M, Hocquette JF, Ritz P, Morio B. Muscle fat oxidative capacity is not impaired by age but by physical inactivity: association with insulin sensitivity. FASEB J. 2004;18(6):737–739. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1104fje. PMID:14977873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooyackers OE, Adey D, Ford GC, Ades P, Nair KS. Effect of aging on skeletal muscle mitochondrial protein synthesis rates in humans. J. Investig. Med. 1996;44:A317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ DW, Kent-Braun JA. Is skeletal muscle oxidative capacity decreased in old age? Sports Med. 2004;34(4):221–229. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434040-00002. PMID:15049714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J, Bastien C, Monod H. Enzymatic adaptations to treadmill training in skeletal muscle of young and old rats. Eur J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1983;52(1):69–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00429028. PMID:6686132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short KR, Bigelow ML, Kahl J, Singh R, Coenen-Schimke J, Raghavakaimal S, Nair KS. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102(15):5618–5623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501559102. PMID:15800038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens BR, Granados K, Zderic TW, Hamilton MT, Braun B. Effects of 1 day of inactivity on insulin action in healthy men and women: interaction with energy intake. Metabolism. 2011;60(7):941–949. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.08.014. PMID:21067784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theou O, Jones GR, Vandervoort AA, Jakobi JM. Daily muscle activity and quiescence in non-frail, pre-frail, and frail older women. Exp. Gerontol. 2010;45(12):909–917. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.008. PMID:20736056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkonogi M, Fernstrom M, Walsh B, Ji LL, Rooyackers O, Hammarqvist F, et al. Reduced oxidative power but unchanged antioxidative capacity in skeletal muscle from aged humans. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446(2):261–269. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1044-9. PMID:12684796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, Mcdowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. PMID:18091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]