INTRODUCTION

BE is characterized by the replacement of squamous epithelium in the esophagus by metaplastic columnar epithelium with goblet cells (specialized intestinal metaplasia).1 The significance of BE stems from it being the strongest risk factor for EAC, a malignancy with the most rapid increase in incidence (approximately 500%) over the past 3 decades in the Western world and with persistently poor outcomes when diagnosed after the onset of symptoms (survival less than 20% at 5 years).2

BE is thought to progress to EAC in a stepwise fashion via increasing grades of dysplasia. The absolute annual risk of progression to EAC remains a subject of debate. Until recently the most accepted rate of progression was 0.5% per year, with a large systemic review of 7780 publications confirming this rate.3 More recent studies based on large population-based pathology registries have shown the risk to be lower.4 It is also well known that patients tend to overestimate their risk of progression,5 which leads to overutilization of surveillance.6

Risk factors for progression to EAC in subjects with BE remain unclear, with clinical, demographic and biomarker variables studied with inconsistent results. This has led to recommendations that subjects with BE be placed in surveillance programs based solely on their baseline grade of dysplasia. This approach is riddled with many limitations7 and is likely not cost effective,8 particularly for nondysplastic BE. Biomarkers predicting progression to EAC have been identified but have not been validated in large population-based prospective studies, limiting their clinical utility.

The exact effect of BE on life expectancy is not well defined. Data show that EAC remains an uncommon cause of death in patients with BE, with cardiovascular disorders a more common cause of mortality.9,10 One study reported a 37% increase in mortality; however, 55% of deaths were due to nonesophageal causes.11 These data highlight the importance not only of managing the risk of EAC but also reducing risks associated with cardiovascular disease in patients with BE. Population-based cohort studies have shown comparable life expectancy (to age-matched and gender-matched general population cohorts) in subjects with BE.12 This review explores current data and recommendations on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, screening, surveillance, and management of BE.

PATHOGENESIS

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the strongest risk factors for BE, with several studies showing its association with BE.13,14 Subjects with BE have more severe reflux (greater time with pH less than 4 in the distal esophagus on ambulatory pH monitoring) with reduced lower esophageal sphincter tone and larger hiatal hernias than those with nonerosive and erosive reflux disease. Nonacid reflux has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of BE.15 Reflux is also more difficult to control in BE subjects, with even high doses of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) failing to achieve control in a substantial minority of BE subjects.16,17

Obesity

The association of BE with elevated body mass index (BMI) has been studied by several investigators with somewhat inconsistent results; one meta-analysis concluded that increased BMI is a risk factor for GERD but not the development of BE.18 Two epidemiologic studies have reported an association of increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio with a BE diagnosis, independent of BMI.19,20 Visceral fat area measured by CT has also been shown a risk factor for BE independent of BMI.21 The distribution of fat as opposed to overall adiposity may play a role in the pathogenesis of BE. Central obesity may also explain the strong male gender and predilection of BE in the white population.

Central obesity leads to increased intrabdominal and intragastric pressure and disruption of the gastroesophageal junction, potentially leading to increased gastroesophageal reflux.22 The actual correlation between increased waist circumference and increased gastroesophageal reflux, however, is somewhat weak.23,24 A second mechanism to explain the association of central obesity with BE is the independent or complementary influence of visceral fat (a metabolically active component of abdominal fat) on esophageal inflammation and metaplasia. Adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines produced by visceral fat may contribute to esophageal injury and metaplasia as shown by preliminary studies.25,26 Whether this effect is independent of reflux-induced injury is unknown. Obesity is also associated with an earlier age of onset of EAC27 with central obesity also strongly associated with EAC.28,29

Familial BE

Genetic influences on the pathogenesis of BE have been hypothesized and explored. A small proportion of subjects with BE (7%) have a documented family history of BE or EAC in first-degree or second-degree relatives.30 This syndrome has been named, familial BE.31 Multiplex cohorts (those with 3 or more affected family members) may have a younger age of cancer onset compared with duplex families and those without family history. This association was found independent of BMI, regurgitation history, and smoking.32 Segregation analysis has identified a possible autosomal dominant mechanism as mediating this association.33

BE may arise from the transdifferentiation of esophageal squamous cells after exposure to gastroesophageal reflux contents or by the migration (from gastric cardia or bone marrow34) and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells under the influence of reflux contents.35 Evidence for the existence of both pathways has been described by investigators and the exact mechanism of the replacement of squamous epithelium in the esophagus by columnar epithelium remains unknown. Stromal elements, such as bone morphogenic protein 4 and fibroblast growth factors,36 are also likely involved in BE pathogenesis by stimulating the activation and modulation of pathways, such as the caudal homeobox gene–produced transcription factors (CDX1 and CDX2),37 Notch, sonic hedgehog, and the Wnt signaling pathways.38,39

DIAGNOSIS

BE is currently defined as “the condition in which any extent of metaplastic columnar epithelium that predisposes to cancer development replaces the stratified squamous epithelium that normally lines the distal esophagus.”40 This definition makes the presumption that the end of the tubular esophagus is well defined; this is unfortunately not true because changes with respiration and motility make this a mobile target. Currently, the top of the gastric folds (in a semi-inflated esophagus) is accepted as the marker for the gastroesophageal junction in the West, due to the lack of an alternate validated target.40,41 Given that interobserver agreement among endoscopists at recognizing a BE segment less than 1 cm long is poor, it is currently accepted that BE is suspected only if at least 1 cm of columnar mucosa is present proximal to the top of the gastric folds (Fig. 1).42 Finally, given the lack of consistent prospective cohort data on the elevated EAC risk with columnar epithelia other than intestinalized metaplasia in the esophagus, in the United States, only specialized columnar metaplasia with goblet cells is accepted as the diagnostic criterion for BE40,43 in contrast to other European countries. A recent population-based retrospective cohort study found the risk of EAC substantially lower in subjects with columnar metaplasia without goblet cells compared with those with specialized intestinal metaplasia, further reinforcing this criterion.44 The diagnosis of BE, therefore, requires the endoscopic confirmation of at least 1 cm of columnar mucosa in the distal esophagus with corresponding biopsies showing specialized intestinal metaplasia. The presence of intestinal metaplasia in biopsies from a normally located but irregular gastroesophageal junction identifies an entity called “intestinal metaplasia of the gastroesophageal junction or cardia” and is thought to have a substantially lower EAC risk than BE.12

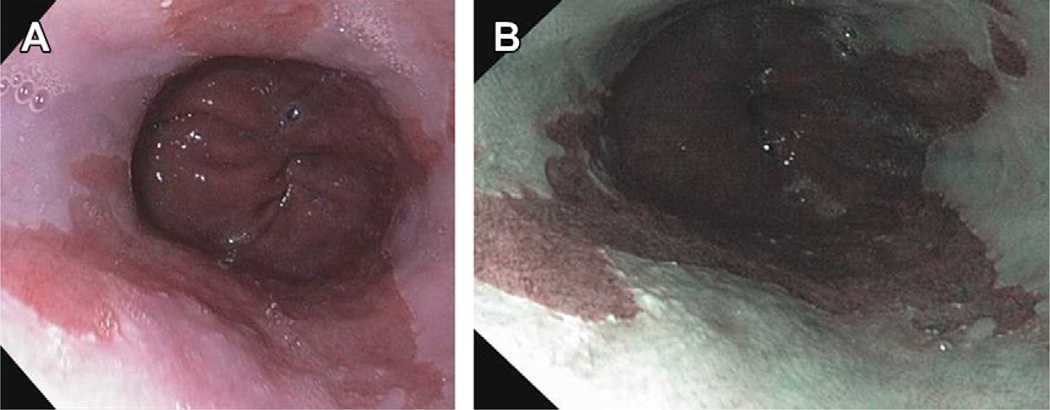

Fig. 1.

(A) Columnar mucosa seen in distal esophagus: columnar mucosa pink in color, squamous mucosa pale white in color. (B) Appearance of columnar mucosa in distal esophagus under NBI highlighting contrast between columnar and squamous mucosa.

The use of chemical agents to highlight esophageal mucosa (chromoendoscopy) has been studied for years with varying results. Methylene blue has had varying results in recognition of BE. A recent meta-analysis of 9 studies showed that there was no increase in detecting intestinal metaplasia compared with standard imaging techniques. 45 Indigo carmine has also been investigated with mixed results; 1 study found it superior in identifying areas with HGD.46 Currently, chromoendoscopy is not routinely used.40 Another technique that has been studied is narrow band imaging (NBI). This technique uses narrow band optical filters (which narrow the spectrum of light illuminating the mucosa to shorter wavelength blue and green light) to highlight the vascular and mucosal patterns of the mucosa. This technique also highlights the difference between squamous and columnar epithelium. NBI-directed biopsies found dysplasia in more patients compared with biopsies taken using standard resolution endoscope (57% vs 43%, respectively).47 Other studies have found its utility lower, with a crossover study looking at chromoendoscopy versus NBI, finding the 2 techniques to have similar rates of detecting HGD and early cancer. Neither technique was found superior to standard white light endoscopy.48 Other advanced endoscopic imaging techniques, like autofluorescence imaging and confocal laser endomicroscopy, have also been studied extensively, but their success beyond high-resolution white light endoscopy has not been enough to recommend use in routine practice.40

SCREENING, EARLY DETECTION

Rationale and Challenges

The basic rationale for screening in BE rests on the concept that EAC arises by a stepwise progression from metaplasia to dysplasia to EAC. Hence, if subjects with BE can be identified (by visualization and sampling of the esophageal mucosa by endoscopic or nonendoscopic methods) they can then be placed into an endoscopic surveillance program, allowing early identification of dysplasia or carcinoma and minimally invasive intervention and improved outcomes. Retrospective cohort studies49,50 have reported that carcinomas detected in surveillance programs are diagnosed at earlier stages with better outcomes compared with when diagnosed after the onset of symptoms. Modeling studies have found this approach cost effective.8 Identified risk factors for BE include older age, male gender, white race, obesity (especially central obesity), and family history. BE is known to present later in life. Cohort studies have shown that patients with GERD are more likely to have BE on endoscopy done later in life.51 This same study found that whites were at higher risk than African Americans or Hispanics for developing BE. This has been shown in several studies, with whites up to 6 times more likely than African Americans to develop BE.52 Men also seem to have predominance for BE, with a meta-analysis showing the ratio for men to women 2:1.18

Challenges to screening are multiple. The lack of a well-defined target population is a significant limitation: the prevalence of BE in those with chronic reflux is between 5% and 10%. Almost 40% to 50% of subjects with BE and EAC, however, do not report frequent or chronic reflux symptoms. Hence, limiting screening to those with chronic reflux symptoms potentially misses a large proportion of cases.53 Endoscopy is expensive and may lead to complications if used in a large population setting.54 The sensitivity and specificity of endoscopy in diagnosing BE has been questioned, with several other limitations noted in the management of subjects after a BE diagnosis, particularly in surveillance (sampling error, lack of agreement on diagnostic criteria for dysplasia, and lack of compliance with surveillance recommendations). The survival benefits seen in retrospective studies are also subject to length and lead time biases.55,56 Prospective studies documenting the beneficial effect of screening and surveillance on EAC-related and overall survival are not available.

Methods

Sedated endoscopy is still the standard of care for screening for BE. Making the diagnosis of BE requires 2 criteria. First endoscopic identification is needed followed by pathologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia (with goblet cells). Identifying the gastroesophageal junction (end of the tubular esophagus) remains central to the diagnosis of BE. During endoscopy, BE is seen as salmon-colored epithelium that projects into the tubular esophagus (see Fig. 1). Endoscopists should report the Prague circumferential and maximum extent of the visualized BE segment to help define the extent of the metaplasia.57 Biopsies should be taken throughout to confirm the diagnosis of BE. Currently the Seattle protocol calls for 4-quadrant biopsy specimens at intervals of 1 cm to 2 cm throughout the esophagus. Also, areas of irregularities should be separately biopsied because nodularity is associated with higher risk of prevalent malignancy.58 Once confirmation of BE is made, examination of the extent of dysplasia is needed because it effects the surveillance interval and treatment recommendations. Currently, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends confirmation of dysplasia by a second pathologist with expertise in gastrointestinal histopathology,40 because there remains substantial variability in the confirmation of dysplasia between community and academic pathologists59 as well as among academic pathologists.60

Several new modalities for screening have been investigated. Esophageal capsule is one technique that has been studied; the esophageal capsule has 2 optical domes that have the ability to capture 14 images per second. A recent meta-analysis, however, found the sensitivity and specificity low at 77% and 87%, respectively. This modality is inferior to standard endoscopy and its use in screening is currently not recommended. Esophageal capsule is safe, however, and has a higher rate of patient preference, suggesting that improvements in capsule technology (better imaging and less cost) could make this a suitable tool for screening and surveillance in BE.61 Another screening technique is unsedated transnasal endoscopy, which has been shown tolerable, safe, and accurate compared with sedated endoscopy.62 It allows accurate and efficient identification of BE with both visualization and biopsy confirmation. Recent studies have shown this technique acceptable and well tolerated in the general population compared with capsule endoscopy and sedated endoscopy. 63 Another nonendoscopic method for screening studied is the cytosponge, an ingestible esophageal sampling device coupled with an immunohistochemical biomarker, trefoil factor 3. It consists of a gelatin-coated capsule attached to a string, which is swallowed. After 5 minutes, the capsule coating dissolves with the formation of a sponge, which can be then pulled out orally providing cytology specimens of the esophagus. Investigators found it a practical and safe for BE screening. Despite its safety, the sensitivity and specificity of the test were found only 73.3% and 93.8%, respectively, for BE greater than 1 cm in circumferential length.64 The cost-effectiveness of these nonendoscopic tools remains to be assessed.

Current Recommendations

Recommendations on screening for BE by different gastroenterology societies are listed in Table 1. Given the issues discussed previously, recommendations are variable, with modest support for screening in subjects with multiple risk factors,40 such as male gender, chronic reflux symptoms, age greater than 50 years, white ethnicity, central obesity, and presence of a hiatal hernia. Combining these risk factors together and forming an algorithmic tool to determine who should be screened would be highly beneficial.40 Screening of the general public is still not recommended,65 although screening patients with chronic GERD, however, is still a common practice in the United States.

Table 1.

Current recommendations regarding screening for BE by gastroenterology societies

| AGA40 | AGA115 | ACG65 | BSG116 |

|---|---|---|---|

| In patients with multiple risk factors for EAC, screening is recommended (weak recommendation, moderate quality evidence) | Consider in those with chronic GER symptoms or at high risk of BE | Usefulness needs to be established | Not in those with chronic GER |

| Recommendations should be individualized | Only in those with alarm symptoms associated with GER (dysphagia, recurrent vomiting, weight loss, anemia) | ||

| Greatest yield in white obese males with chronic symptomatic reflux | |||

| Screening the general population not recommended (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence) |

Abbreviations: ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; ASGE, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology.

RISK STRATIFICATION

Risk of Progression

The risk of progression in subjects with BE has been the subject of much study. A landmark article estimated the risk of progression at 0.5% per patient year of follow-up. Large meta-analyses3,66 have confirmed these estimates (Table 2). More recently, large population-based studies from Europe (the Netherlands,67 Northern Ireland,44 and Denmark4) have reported lower estimates of progression, ranging from 0.12% to 0.22% per patient year of follow-up. In better-characterized cohorts with defined columnar segments and the confirmation of intestinal metaplasia, however, the incidence of EAC is closer to earlier estimates (0.38% per patient year of follow-up).44

Table 2.

Rates of progression in subjects with BE stratified by grade of dysplasia

Predictors of Progression

Demographic and clinical factors: older age and male gender seem to predict higher risk of progression to HGD and/or EAC in subjects with BE.3,44 The length of the BE segment may be a risk factor for progression, with 1 recent multicenter cohort study reporting that the risk of progression in nondysplastic BE subjects with a BE segment greater than 6 cm was significantly higher (0.65% per patient year) compared with those with segment lengths shorter than 6 cm (0.09% per patient year).68 Prior studies and meta-analyses had not found a similar association.3,69 Increased segment length may also lead to increased risk of progression to EAC in patients without HGD, but currently, a cutoff length at which the risk of HGD/EAC increases is not known.70 Smoking also seems to increase the risk of developing HGD or EAC in subjects with BE (hazard ratio 2.03; 95% CI, 1.29, 3.17).71 No association was seen with alcohol consumption in this study. The presence of nodularity in the BE segment also portends a higher likelihood of prevalent advanced neoplasia and higher rate of progression to EAC.58 Limited data exist on the influence of obesity (overall, as measured by BMI, or central, as measured by anthropometry: waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio) on progression in subjects with BE.70

Medications

Recent observational nonrandomized studies have reported a lower risk of progression to EAC in BE subjects on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and statins. 72,73 The effect of these 2 classes of medications may be additive.74

Grade of dysplasia

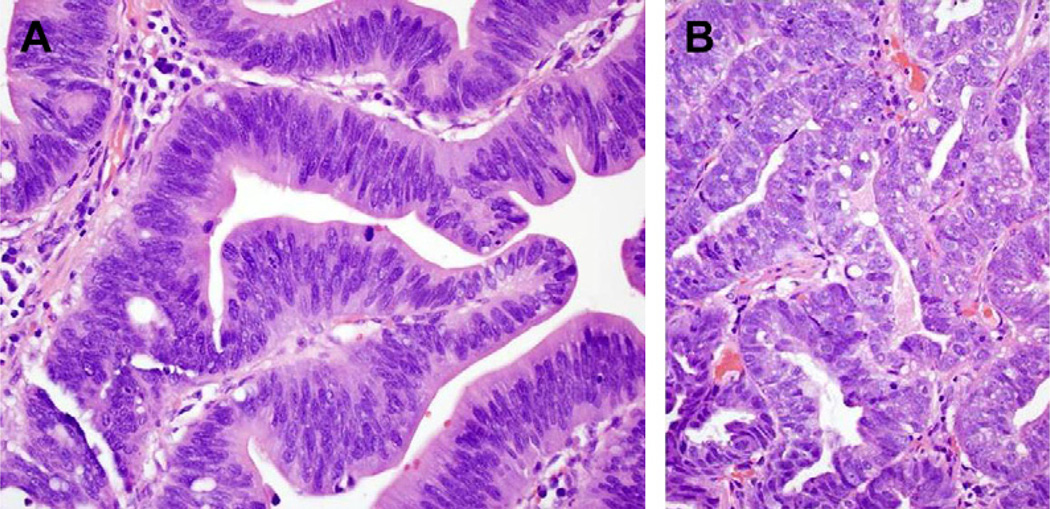

Grade of dysplasia is the most widely used marker for risk stratification in subjects with BE despite many limitations: (1) spotty distribution of dysplasia leading to sampling error, (2) significant interobserver variability amongst pathologists, and (3) variation in progression rates in different cohorts. Subjects with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) (Fig. 2A) seem to progress at a higher rate than those without dysplasia,66 although there are reports that contradict this.75 Patients with HGD (see Fig. 2B) progress to EAC at a substantially higher rate of 66 per 1000 patient years.76

Fig. 2.

(A) High-power view of LGD (200×) on hematoxylin-eosin stain: nuclei showing stratification, without pleomorhphism and maintaining orientation to basement membrane. (B) High-power view of HGD (200×) on hematoxylin-eosin stain: nuclei showing hyperchromatism, pleiomorphism, loss of polarity to basement membrane.

Biomarkers

Currently, there are several biomarkers that have been studied to help predict the progression of BE, although no panels are ready for clinical use. Biomarkers studied include loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for chromosome p17, aneuploidy/tetraploidy, and methylation-based markers. Patients with aneuploidy or tetraploidy present on biopsy had an increased incidence of 5-year cancer risk than those without, 0% versus 28% respectively.77 These investigators used flow cytometry performed on frozen tissue specimens, techniques that are not available at most institutions, thus making it hard to implement testing on large scale. Another marker for neoplastic progression is LOH for the 17p locus. One study concluded that subjects with 17p LOH had increased rates of progression to cancer with a relative risk of 16 compared with those with 2 intact 17p alleles.78 Unfortunately, this study also required a labor-intensive technique of flow cytometry. This same group looked at using a panel of aneuploidy/tetraploidy, 17p LOH, and 9p LOH, and found a 6-year incidence of cancer of 80% for those with all 3 abnormalities, compared with an incidence of 12% at 10 years for those without any abnormalities.79 Methylation-based panels have also shown promise in predicting which patients with BE will progress to HGD and/or to EAC. Patients with methylation of p16, RUNX3, and HPP1 were shown to have an increased risk of progression to both HGD and EAC.80 Although none of these markers has been applied to prospective trials, there may be use for them in the future for risk-stratifying patients with BE. At this time, biomarkers are not used in the current clinical management of BE.

MANAGEMENT

Surveillance

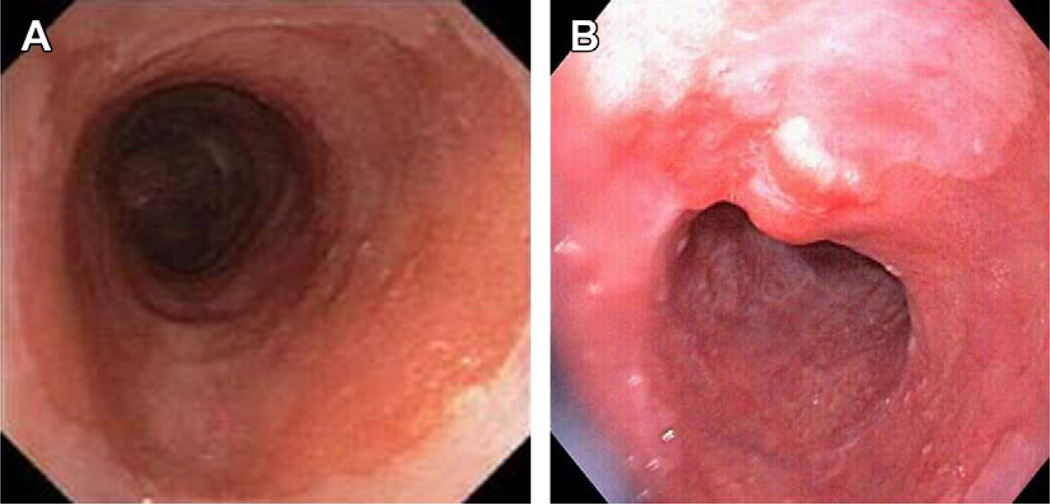

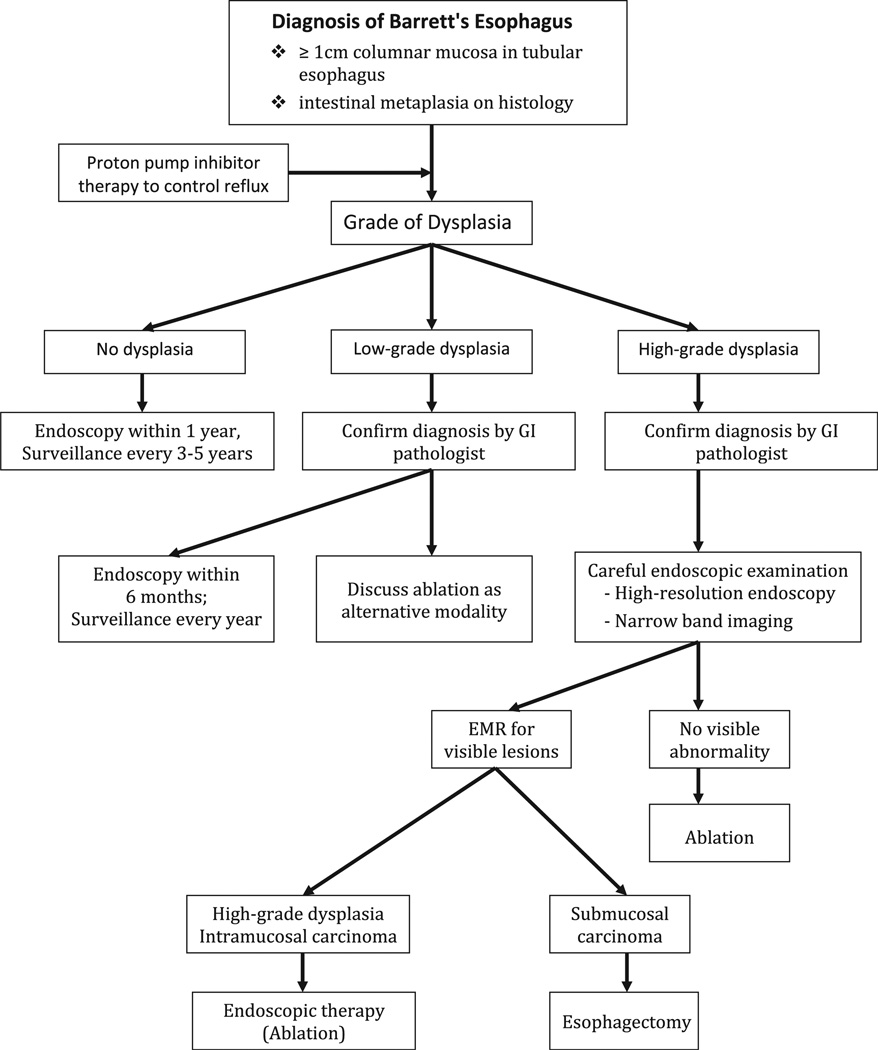

Surveillance guidelines for BE are based currently solely on the degree of dysplasia (Table 3). Current guidelines from each gastroenterology society vary, but it is generally accepted that patients found to have no dysplasia should have 2 esophageal examinations with biopsy within 1 year (to decrease the likelihood of missed prevalent dysplasia) followed by surveillance every 3 to 5 years.40 Patients with LGD (confirmed by 2 pathologists, at least 1 having expertise in gastrointestinal pathology) should have 2 esophageal examinations within 6 months (to exclude prevalent dysplasia) followed by annual surveillance. A diagnosis of HGD should be confirmed by a pathologist with expertise in gastrointestinal pathology. This should be followed by careful examination with high-resolution white light endoscopy and other imaging techniques, such as NBI to detect visible mucosal abnormalities, which may reflect more advanced neoplasia, such as intramucosal or submucosal adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3). Patients with HGD who do not undergo intensive therapy should be followed with endoscopic surveillance every 3 months.65 There is some evidence that patients who are followed in surveillance groups have better survival compared with patients who develop EAC outside of surveillance groups. In a recent retrospective study of 2754 subjects, patients who had prior endoscopy 3 to 6 months before diagnosis of EAC had survival median of 11 months compared with 7 months for patients who had never had endoscopy.50 One of the issues in determining how successful surveillance strategies actually are is the abundance of potential confounders, including lead-time and length-time biases. These confounders were highlighted in a cohort study by Rubenstein and colleagues56 that showed no survival advantage in patients with prior endoscopy. Randomized data on the influence of surveillance on outcomes in subjects with BE is still awaited. With the advent of better-tolerated and safe ablative techniques, surveillance is the least advisable approach, given the possibility of missed advanced neoplasia.

Table 3.

Summary of current recommendations regarding surveillance of subjects with BE, as determined by grade of dysplasia

| AGA40 | ASGE115 | ACG65 | BSG116 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dysplasia | Assess within 1 y and if no dysplasia, repeat in 5 y | Two consecutive examinations within 1 y and follow-up with endoscopy every 3 y | Two examinations with biopsy within 1 y and follow-up with endoscopy every 3 y | Surveillance every 2 y |

| LGD | Assess in 1 y and re-examine every year if confirmed by 2 pathologists | Follow-up after 6 mo with concentrated biopsies in area of dysplasia, with follow-up every 12 mo thereafter if persistent dysplasia | Treat based on highest grade of dysplasia on 2 examinations within 6 mo and follow-up every year until dysplasia is absent for 2 consecutive endoscopies | Extensive biopsies after acid suppression for 8–12 wk |

| Surveillance every 6 mo if dysplasia persists, every 2–3 y after 2 consecutive examinations showing no dysplasia | ||||

| HGD | Diagnosis should be confirmed by 2 pathologists | Diagnosis should be confirmed by a pathologist | Repeat examination with biopsy within 3 mo with pathology confirmation | Confirmation by 2 pathologists, esophagectomy recommended if persistent changes after intensive acid suppression, if not a surgical candidate then endoscopic therapy recommended |

| Patients should be treated with esophagectomy or endoscopic therapy; followup every 3 mo if no therapy | Surgical candidates should have surgery or have endoscopic therapy. If no therapy, surveillance every 3 mo. After 1 y of no malignancy, surveillance can be lengthened | |||

| Follow-up with EMR for any mucosal irregularity then surveillance every 3 mo if no intervention (esophagectomy vs endoscopic ablation) | ||||

Abbreviations: ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; ASGE, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology.

Fig. 3.

(A) Barrett’s segment in subject with HGD without visible abnormalities: flat HGD. (B) Barrett’s segment in subject with HGD showing visible nodular change on white light imaging: nodular HGD. This should be targeted by endoscopic resection for staging and diagnosis.

Endoscopic Therapy

The risk of progression for subjects with nondysplastic BE and LGD seem to remain low with long-term studies showing that less than 10% of patients progress to HGD or EAC,81 with some studies reporting similar rates of progression with both groups68,75,82 and others reporting higher rates.83

Ablation of nondysplastic BE has had varying success. One study reported both endoscopic and histologic reversal in 78% of patients; however, follow-up was only 6 months.84 Other studies have also showed successful eradication, with one trial comparing argon plasma coagulation group to photodynamic therapy (PDT), finding successful eradication in 97% versus 50%, respectively, in the 2 groups.85 Once again, longer follow-up of these patients was not done. Some investigators have argued that if eradication led to durable elimination of BE, ablation would be cost effective; however, currently data suggest that surveillance remains essential given the incidence of recurrence of metaplasia and dysplasia after successful ablation, making estimates of cost-effectiveness questionable.86 Also, treatment is not without complications becuase studies do report stricture formation and bleeding after treatment. Current guidelines do not recommend ablation therapy for nondysplastic BE.40 Treatment of LGD has been studied with varying success in eradication as well.87 Although some studies have suggested that subgroups of patients with LGD who are at higher risk of progression can be identified,88–90 others have not found these factors predictive.75 In subjects with LGD that has been confirmed by review of an expert pathologist, ablation as a modality of treatment can be discussed as per recent AGA guidelines.40 The need for continuing surveillance, however, even after successful ablation, given the risk of recurrence should be discussed with patients.

HGD is an accepted indication for endoscopic therapy as an alternative to esophagectomy. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) resects into the submucosa and is used for the evaluation of nodular dysplastic BE and the staging of early carcinoma. It is recommended that any mucosal irregularity, such as nodularity or ulcer, should be assessed with EMR for a more thorough histologic evaluation and exclusion of cancer. Additionally, it is recommended that repeat EGD with biopsies every 1 cm be done within 3 months to exclude coexistent EAC.65 EMR is helpful in staging of esophageal neoplasia. A study of 25 patients showed it as accurate as esophagectomy in diagnosis of tumor stage for early esophageal neoplasia during preoperative staging.91 Several studies have shown EMR useful in treatment of HGD and intramucosal cancer.92,93 Currently, there are no randomized studies comparing it to other modalities of treatment. Ablation of the residual BE segment after focal EMR is recommended to reduce rates of recurrent neoplasia.

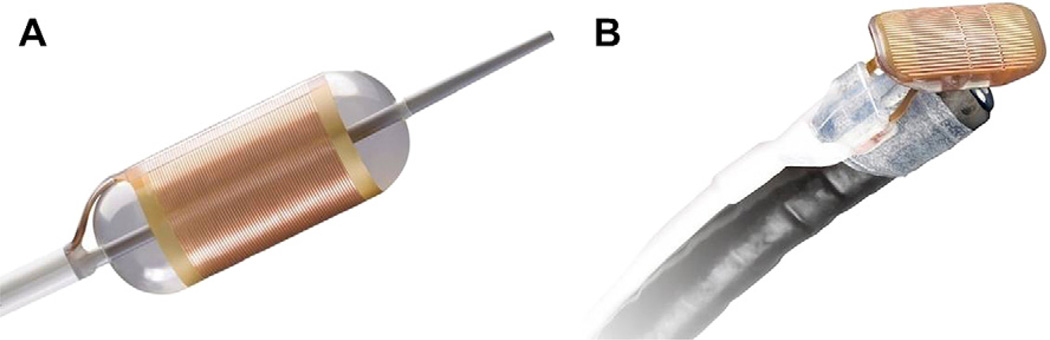

There is a plethora of evidence showing that endoscopic treatment is beneficial in treatment of HGD. PDT was shown superior when compared with omeprazole and surveillance in a randomized controlled trial, in terms of reducing the rate of progression to EAC and eliminating HGD.94 Other studies have also shown success with PDT.95 Beyond PDT, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has also shown promise. RFA has the ability to deliver high-energy pulses to the esophageal mucosa creating thermal injury. This energy can be delivered using a circumferential (Halo 360, BARRX, Sunnyvale, California) or focal (Halo 90, BARRX, Sunnyvale, California) device (Fig. 4). RFA was shown to achieve eradication of BE in 79% of patients in one study.96 Additionally it was proved safe and effective in a randomized controlled trial compared with a sham procedure.87 In this randomized controlled trial, RFA was well tolerated, with only 6% of patients developing strictures; additionally, in those treated with RFA, the rate of progression to EAC was reduced in the RFA arm compared with the sham arm. In addition to endoscopic treatment alone, studies have shown benefit of RFA after EMR: a study of 23 patients achieved eradication in 95% of HGD and 88% of early EAC at 22-month follow-up.97 The current approach to the management of subjects with BE is summarized in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

(A) Circumferential ablation device for RFA (Halo 360 ablation catheter, BARRX Medical, Sunnyvale, California). (B) Focal ablation device for RFA (Halo 90 ablation catheter, BARRX Medical, Sunnyvale, California).

Fig. 5.

Summary of current approach to the management of subjects with BE.

Recurrence of intestinal metaplasia after successful ablation has been reported. In a 3-year follow-up of the initial Ablation of Intestinal Metaplasia Containing Dysplasia trial,87 although 3-year rates of remission of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia were greater than 90%, 10% to 20% of subjects needed retreatment for recurrent intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia, underscoring the importance of continued surveillance after intestinal metaplasia is eliminated.98 This has also been seen with PDT.99 Subsquamous BE (columnar mucosa underneath neosquamous mucosa) is an issue that raises concerns given the possibility of undetected progression to HGD/EAC, which has been reported in case studies.100 Biologic properties of these subsquamous islands may, however, be less sinister than that of exposed columnar tissue. Subsquamous BE may exist before ablation and the rates of subsquamous BE after RFA seem low (0.9%), presuming that postablation biopsies are deep enough to detect subsquamous BE. Some investigators have reported that esophageal biopsies obtained postablation may be superficial with only limited amount of lamina propria present, rendering these biopsies inadequate to exclude subsquamous BE.101 Despite these concerns, overall, endoscopic therapy has been shown safe and beneficial in the treatment of HGD.

Esophagectomy has long been considered the gold standard for treatment of HGD; however, with the success of endoscopic therapy, this may no longer be certain. One retrospective study comparing survival of early EAC after treatment with PDT in 129 patients versus esophagectomy in 70 patients found similar overall survival in both groups.102 Similar results have been reported in subjects with HGD treated endoscopically and surgically as well.102 Esophagectomy carries a high risk for morbidity and mortality, and should be performed at large volume referral centers where many surgeries are done each year.103 Esophagectomy could be considered for young patients with HGD given the current lack of information on outcomes beyond 5 to 10 years after endoscopic therapy. As long-term data on outcomes after endoscopic therapy continue to accumulate, however, the rationale for esophagectomy may weaken further.

Fundoplication

The potential rationale for fundoplication in the management of subjects with BE rests on 3 areas: symptom control and inducing regression of BE, preventing progression to adenocarcinoma, and reflux control postablation to decrease the odds of recurrent metaplasia and neoplasia. Conclusions in these areas are limited by the lack of randomized data comparing medical and surgical therapy. Case series have reported the regression of metaplasia and dysplasia after the prolonged administration of either PPIs or after fundoplication: however, this is typically seen in subjects with very short segments. More typically, squamous islands appear at biopsy sites after prolonged surveillance and acid reflux control.104 A comprehensive meta-analysis reached the conclusion that fundoplication did not protect against progression to EAC compared with medical therapy, when data from randomized trials are considered105 (6.5 cases/1000 patient years in the medical group vs 4.8/1000 patient years in the surgical group) with more recent studies supporting that conclusion.104 A recent randomized trial comparing laparoscopic antireflux surgery to medical therapy with esomeprazole in subjects with esomeprazole-responsive reflux disease showed similar results.106 Data on factors predicting recurrence of metaplasia after successful ablation are limited to uncontrolled studies, with some reporting the presence of uncontrolled reflux as a factor predicting recurrent metaplasia and dysplasia.107,108 No controlled data, however, on the relative advantages of fundoplication versus medical therapy are currently available.

Chemoprevention

The concept of chemoprevention in BE has been investigated by several investigators. The use of PPIs to prevent progression of BE has been studied at length. Most of the evidence is indirect, with laboratory data showing that acid can damage DNA and induce proliferation. There are some nonrandomized observational studies showing that PPIs may reduce the rate of progression in BE and patients who use them have an overall lower incidence of EAC109,110; however, it is currently not recommended to use doses of PPIs over the amount needed to prevent symptomatic reflux as a form of chemoprevention. Preventing reflux has driven the concept of antireflux surgery as a means of chemoprevention. Several studies have not found antireflux surgery beneficial in preventing EAC111,112 and it is not recommended as an antineoplastic measure. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as a form of chemoprevention have shown promise in potentially reducing the risk of developing EAC113,114; however, randomized data are awaited. Currently, it is recommended that patients with BE and cardiovascular risk factors be started on low-dose aspirin. Because most patients are on a PPI, the risk of bleeding remains low. Further randomized controlled studies are in progress looking at the benefit of aspirin in BE.

In summary, subjects with BE have a significantly increased risk of progression to EAC. Screening for BE remains challenging due to lack of availability of a suitable tool and lack of a well-defined target population, although progress is being made in this direction. Predictors of progression in BE (in addition to the grade of dysplasia) include increasing age, male gender, and probably longer BE segments: biomarkers to predict progression are in development. Endoscopic therapy for dysplasia in BE has emerged as a first-line approach, with esophagectomy reserved for those who do not respond to endoscopic therapy. The role of obesity in the pathogenesis and progression of subjects with BE remains to be defined.

KEY POINTS.

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the strongest risk factor for and known precursor for esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), a lethal malignancy with a rapidly rising incidence.

Diagnosis requires endoscopic confirmation of columnar metaplasia in the distal esophagus and histologic confirmation of specialized intestinal metaplasia.

Current recommendations for the management of subjects diagnosed with BE include periodic endoscopic surveillance to detect the development of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or adenocarcinoma.

Multimodality endoscopic therapy is effective in the therapy of HGD and early-stage adenocarcinoma with comparable outcomes to esophagectomy in cohort studies.

Careful endoscopic surveillance to detect recurrent metaplasia or neoplasia after successful endoscopic therapy of BE-related neoplasia is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. RC4DK090413 from the National Institutes of Health, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Sharma P. Clinical practice. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2548–2556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0902173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(2):142–146. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yousef F, Cardwell C, Cantwell MM, et al. The incidence of esophageal cancer and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(3):237–249. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaheen NJ, Green B, Medapalli RK, et al. The perception of cancer risk in patients with prevalent Barrett’s esophagus enrolled in an endoscopic surveillance program. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crockett SD, Lipkus IM, Bright SD, et al. Overutilization of endoscopic surveillance in nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(1):23–31. e22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spechler SJ. Dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: limitations of current management strategies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):927–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inadomi JM, Sampliner R, Lagergren J, et al. Screening and surveillance for Barrett esophagus in high-risk groups: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):176–186. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.vanderBurgh A, Dees J, Hop WC, et al. Oesophageal cancer is an uncommon cause of death in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 1996;39(1):5–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rana PS, Johnston DA. Incidence of adenocarcinoma and mortality in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus diagnosed between 1976 and 1986: implications for endoscopic surveillance. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13(1):28–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solaymani-Dodaran M, Logan RF, West J, et al. Mortality associated with Barrett’s esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux disease diagnoses—a population- based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(12):2616–2621. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung KW, Talley NJ, Romero Y, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of intestinal metaplasia of the gastroesophageal junction and barrett’s esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(8):1447–1455. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisen GM, Sandler RS, Murray S, et al. The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eloubeidi MA, Provenzale D. Clinical and demographic predictors of Barrett’s esophagus among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a multivariable analysis in veterans. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(4):306–309. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song S, Guha S, Liu K, et al. COX-2 induction by unconjugated bile acids involves reactive oxygen species-mediated signalling pathways in Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2007;56(11):1512–1521. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.121244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katzka DA, Castell DO. Successful elimination of reflux symptoms does not insure adequate control of acid reflux in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(7):989–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spechler SJ, Barker PN, Silberg DG. Intragastric acid control in patients who have Barrett’s esophagus: comparison of once- and twice-daily regimens of esomeprazole and lansoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(2):138–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook MB, Greenwood DC, Hardie LJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of increasing adiposity on Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(2):292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelstein ZR, Farrow DC, Bronner MP, et al. Central adiposity and risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):403–411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, et al. Abdominal obesity and body mass index as risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):34–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.046. [quiz:311]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Serag HB, Kvapil P, Hacken-Bitar J, et al. Abdominal obesity and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(10):2151–2156. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandolfino JE, El-Serag HB, Zhang Q, et al. Obesity: a challenge to esophagogastric junction integrity. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):639–649. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Serag HB, Ergun GA, Pandolfino J, et al. Obesity increases oesophageal acid exposure. Gut. 2007;56(6):749–755. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Serag HB, Tran T, Richardson P, et al. Anthropometric correlates of intragastric pressure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(8):887–891. doi: 10.1080/00365520500535402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubenstein JH, Dahlkemper A, Kao JY, et al. A pilot study of the association of low plasma adiponectin and Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1358–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubenstein JH, Kao JY, Madanick RD, et al. Association of adiponectin multimers with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2009;58(12):1583–1589. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.171553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chak A, Falk G, Grady WM, et al. Assessment of familiality, obesity, and other risk factors for early age of cancer diagnosis in adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(8):1913–1921. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steffen A, Schulze MB, Pischon T, et al. Anthropometry and esophageal cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(7):2079–2089. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corley DA, Kubo A, Zhao W. Abdominal obesity and the risk of esophageal and gastric cardia carcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(2):352–358. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chak A, Lee T, Kinnard MF, et al. Familial aggregation of Barrett’s oesophagus, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, and oesophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma in Caucasian adults. Gut. 2002;51(3):323–328. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chak A, Ochs-Balcom H, Falk G, et al. Familiality in Barrett’s esophagus, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, and adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(9):1668–1673. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chak A, Chen Y, Vengoechea J, et al. Variation in Age at Cancer Diagnosis in Familial versus Nonfamilial Barrett’s Esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(2):376–383. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun X, Elston R, Barnholtz-Sloan J, et al. A segregation analysis of Barrett’s esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(3):666–674. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarosi G, Brown G, Jaiswal K, et al. Bone marrow progenitor cells contribute to esophageal regeneration and metaplasia in a rat model of Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21(1):43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souza RF. The role of acid and bile reflux in oesophagitis and Barrett’s metaplasia. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38(2):348–352. doi: 10.1042/BST0380348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishnadath KK. Novel findings in the pathogenesis of esophageal columnar metaplasia or Barrett’s esophagus. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23(4):440–445. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32814e6b4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Baal JW, Bozikas A, Pronk R, et al. Cytokeratin and CDX-2 expression in Barrett’s esophagus. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(2):132–140. doi: 10.1080/00365520701676575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrow DJ, Avissar NE, Toia L, et al. Pathogenesis of Barrett’s esophagus: bile acids inhibit the Notch signaling pathway with induction of CDX2 gene expression in human esophageal cells. Surgery. 2009;146(4):714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.050. [discussion:721–12]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters JH, Avisar N. The molecular pathogenesis of Barrett’s esophagus: common signaling pathways in embryogenesis metaplasia and neoplasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(Suppl 1):S81–S87. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, et al. American gastroenterological association technical review on the management of barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):e18–e52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McClave SA, Boyce HW, Jr, Gottfried MR. Early diagnosis of columnar-lined esophagus: a new endoscopic diagnostic criterion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33(6):413–416. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(87)71676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma P, McQuaid K, Dent J, et al. A critical review of the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: the AGA Chicago Workshop. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(1):310–330. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, Hahn H, Odze RD, et al. Metaplastic esophageal columnar epithelium without goblet cells shows DNA content abnormalities similar to goblet cell-containing epithelium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(4):816–824. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhat S, Coleman HG, Yousef F, et al. Risk of malignant progression in Barrett’s esophagus patients: results from a large population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(13):1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ngamruengphong S, Sharma VK, Das A. Diagnostic yield of methylene blue chromoendoscopy for detecting specialized intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(6):1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma P, Weston AP, Topalovski M, et al. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2003;52(1):24–27. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfsen HC, Crook JE, Krishna M, et al. Prospective, controlled tandem endoscopy study of narrow band imaging for dysplasia detection in Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):24–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kara MA, Peters FP, Rosmolen WD, et al. High-resolution endoscopy plus chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging in Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2005;37(10):929–936. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corley DA, Levin TR, Habel LA, et al. Surveillance and survival in Barrett’s adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(3):633–640. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Chak A. Receipt of previous diagnoses and endoscopy and outcome from esophageal adenocarcinoma: a population-based study with temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1356–1362. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abrams JA, Fields S, Lightdale CJ, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus among patients who undergo upper endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, et al. Race, ethnicity, sex and temporal differences in Barrett’s oesophagus diagnosis: a large community-based study, 1994–2006. Gut. 2009;58(2):182–188. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(11):825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dellon ES, Shaheen NJ. Does screening for Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus prolong survival. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(20):4478–4482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM. Potential for lead-time and length-time biases in outcomes in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):3106–3107. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.488. [author reply:3107–8]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rubenstein JH, Sonnenberg A, Davis J, et al. Effect of a prior endoscopy on outcomes of esophageal adenocarcinoma among United States veterans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(5):849–855. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1392–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buttar NS, Wang KK, Sebo TJ, et al. Extent of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus correlates with risk of adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(7):1630–1639. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alikhan M, Rex D, Khan A, et al. Variable pathologic interpretation of columnar lined esophagus by general pathologists in community practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50(1):23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montgomery E, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett esophagus: a reaffirmation. Hum Pathol. 2001;32(4):368–378. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.23510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhardwaj A, Hollenbeak CS, Pooran N, et al. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of esophageal capsule endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Atkinson M, Chak A. Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;12(2):62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tgie.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang JY, Talley NJ, Locke GR., 3rd Population screening for Barrett esophagus: a prospective randomized pilot study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(12):1174–1180. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kadri SR, Lao-Sirieix P, O’Donovan M, et al. Acceptability and accuracy of a non-endoscopic screening test for Barrett’s oesophagus in primary care: cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c4372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(3):788–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wani S, Puli SR, Shaheen NJ, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus after endoscopic ablative therapy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):502–513. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Jonge PJ, van Blankenstein M, Looman CW, et al. Risk of malignant progression in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus: a Dutch nationwide cohort study. Gut. 2010;59(8):1030–1036. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.176701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wani S, Falk G, Hall M, et al. Patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus have low risks for developing dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.008. [quiz: e226]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rudolph RE, Vaughan TL, Storer BE, et al. Effect of segment length on risk for neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett esophagus. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):612–620. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prasad GA, Bansal A, Sharma P, et al. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus: current knowledge and future directions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1490–1502. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coleman HG, Bhat S, Johnston BT, et al. Tobacco smoking increases the risk of high-grade dysplasia and cancer among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):233–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nguyen DM, Richardson P, El-Serag HB. Medications (NSAIDs, statins, proton pump inhibitors) and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2260–2266. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB, Henderson L, et al. Medication usage and the risk of neoplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(12):1299–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kastelein F, Spaander MC, Biermann K, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and statins have chemopreventative effects in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(6):2000–2008. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.036. [quiz: e2013–2004]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wani S, Falk GW, Post J, et al. Risk factors for progression of low-grade dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1179–1186. 1186 e1171. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rastogi A, Puli S, El-Serag HB, et al. Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):394–398. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reid BJ, Levine DS, Longton G, et al. Predictors of progression to cancer in Barrett’s esophagus: baseline histology and flow cytometry identify low- and high-risk patient subsets. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(7):1669–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reid BJ, Prevo LJ, Galipeau PC, et al. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus II: baseline 17p (p53) loss of heterozygosity identifies a patient subset at increased risk for neoplastic progression. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2839–2848. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Galipeau PC, Li X, Blount PL, et al. NSAIDs modulate CDKN2A, TP53, and DNA content risk for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. PLoS Med. 2007;4(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schulmann K, Sterian A, Berki A, et al. Inactivation of p16, RUNX3, and HPP1 occurs early in Barrett’s-associated neoplastic progression and predicts progression risk. Oncogene. 2005;24(25):4138–4148. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schnell TG, Sontag SJ, Chejfec G, et al. Long-term nonsurgical management of Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(7):1607–1619. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma P, Falk GW, Weston AP, et al. Dysplasia and cancer in a large multicenter cohort of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(5):566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Curvers WL, ten Kate FJ, Krishnadath KK, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: overdiagnosed and underestimated. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1523–1530. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sampliner RE, Faigel D, Fennerty MB, et al. Effective and safe endoscopic reversal of nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus with thermal electrocoagulation combined with high-dose acid inhibition: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53(6):554–558. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kelty CJ, Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, et al. Endoscopic ablation of Barrett’s oesophagus: a randomized-controlled trial of photodynamic therapy vs. argon plasma coagulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(11–12):1289–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inadomi JM, Somsouk M, Madanick RD, et al. A cost-utility analysis of ablative therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(7):2101–2114. e2101–e2106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2277–2288. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Montgomery E, Goldblum JR, Greenson JK, et al. Dysplasia as a predictive marker for invasive carcinoma in Barrett esophagus: a follow-up study based on 138 cases from a diagnostic variability study. Hum Pathol. 2001;32(4):379–388. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.23511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Skacel M, Petras RE, Gramlich TL, et al. The diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and its implications for disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3383–3387. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Skacel M, Petras RE, Rybicki LA, et al. p53 expression in low grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: correlation with interobserver agreement and disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2508–2513. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prasad GA, Buttar NS, Wongkeesong LM, et al. Significance of neoplastic involvement of margins obtained by endoscopic mucosal resection in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2380–2386. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peters FP, Kara MA, Rosmolen WD, et al. Stepwise radical endoscopic resection is effective for complete removal of Barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1449–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conio M, Repici A, Cestari R, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus: an Italian experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(42):6650–6655. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i42.6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Overholt BF, Wang KK, Burdick JS, et al. Five-year efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy with Photofrin in Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3):460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pech O, Gossner L, May A, et al. Long-term results of photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid for superficial Barrett’s cancer and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sharma VK, Jae Kim H, Das A, et al. Circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett’s esophagus containing dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):310–317. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pouw RE, Wirths K, Eisendrath P, et al. Efficacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for Barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shaheen NJ, Overholt BF, Sampliner RE, et al. Durability of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):460–468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Badreddine RJ, Prasad GA, Wang KK, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrent neoplasia after ablation of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(4):697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gray NA, Odze RD, Spechler SJ. Buried metaplasia after endoscopic ablation of Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(11):1899–1908. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.255. [quiz:1909]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gupta N, Mathur SC, Dumot JA, et al. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for postablation surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Prasad GA, Wang KK, Buttar NS, et al. Long-term survival following endoscopic and surgical treatment of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4):1226–1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.van Lanschot JJ, Hulscher JB, Buskens CJ, et al. Hospital volume and hospital mortality for esophagectomy. Cancer. 2001;91(8):1574–1578. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010415)91:8<1574::aid-cncr1168>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wassenaar EB, Oelschlager BK. Effect of medical and surgical treatment of Barrett’s metaplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(30):3773–3779. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chang EY, Morris CD, Seltman AK, et al. The effect of antireflux surgery on esophageal carcinogenesis in patients with barrett esophagus: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2007;246(1):11–21. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000261459.10565.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(19):1969–1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kahaleh M, Van Laethem JL, Nagy N, et al. Long-term follow-up and factors predictive of recurrence in Barrett’s esophagus treated by argon plasma coagulation and acid suppression. Endoscopy. 2002;34(12):950–955. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ferraris R, Fracchia M, Foti M, et al. Barrett’s oesophagus: long-term follow-up after complete ablation with argon plasma coagulation and the factors that determine its recurrence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(7):835–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cooper BT, Chapman W, Neumann CS, et al. Continuous treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus patients with proton pump inhibitors up to 13 years: observations on regression and cancer incidence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(6):727–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.El-Serag HB, Aguirre TV, Davis S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors are associated with reduced incidence of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(10):1877–1883. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Corey KE, Schmitz SM, Shaheen NJ. Does a surgical antireflux procedure decrease the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus? A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2390–2394. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tran T, Spechler SJ, Richardson P, et al. Fundoplication and the risk of esophageal cancer in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a Veterans Affairs cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(5):1002–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Corley DA, Kerlikowske K, Verma R, et al. Protective association of aspirin/NSAIDs and esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(1):47–56. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vaughan TL, Dong LM, Blount PL, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of neoplastic progression in Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(12):945–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(4):570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Playford RJ. New British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2006;55(4):442. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Desai TK, Krishnan K, Samala N, et al. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2012;61(7):970–976. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]