Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The objective of this study was to compare complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in women with and without pelvic floor disorders (PFD).

Methods

We conducted a survey of women presenting to a specialty urogynecology (Urogyn) and gynecology (Gyn) clinic that examined demographic data, CAM use, and the presence of PFD (validated questionnaires). T tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and logistic regression were used for analysis. To detect a 20% difference between groups, 234 Urogyn and 103 Gyn patients were needed.

Results

Participants included 234 Urogyn and 103 Gyn patients. Urogyn patients reported more CAM use than Gyn patients, even when controlled for differences between groups (51% vs. 32%, adjusted p=0.006). Previous treatment (61% vs. 39%, adjusted p<0.001) and increased number of PFD was associated with increased CAM use (adjusted p=0.02).

Conclusions

Women with PFD use CAM more frequently than women without PFD.

Keywords: Complementary alternative medicine, Fecal incontinence, Pelvic floor disorders, Pelvic organ prolapse, Urinary incontinence

Introduction

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines complementary alternative medicine (CAM) as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine [1]. The use of CAM has gained popularity in the USA, increasing from 33% in 1990 to more than 42% in 1997 [2, 3]. One in five primary care patients reported CAM use within the past year in conjunction with a current medical problem including treatment of low back pain, diabetes, obesity, and diseases of the respiratory and genitourinary systems [4].

CAM is becoming more important in gynecologic practice [2, 4]. In a survey of general gynecology and gynecologic cancer patients, 52% and 66% of patients reported current CAM use [5]. CAM use in gynecology has been reported for the treatment of urinary tract disorders, gynecologic surgery, bowel disorders, cancer, infertility, menopause, menstrual disorders, vaginitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease [6]. Despite reported widespread use of CAM in gynecology, there is limited information on the specific use of CAM in women with pelvic floor disorders.

Pelvic floor disorders (PFD) are problems affecting a woman’s pelvic organs including the uterus, vagina, bladder, and rectum and the structures that support them. An estimated one-third of all US women are affected by one type of PFD in their lifetime [7]. The most common types of PFD include pelvic organ prolapse (POP), urinary (UI), and fecal incontinence (FI), with many women suffering from more than one disorder. Commonly used conventional therapies include dietary and lifestyle changes, medication, pessaries, pelvic floor exercises, and surgery. Efficacies of conventional medical therapies for PFD vary widely and are rarely curative. For example, one in three women who undergo surgery for UI and/or POP has a second surgery within a mean of 12 years [8]. In addition, PFD have proven responsiveness to non-traditional therapies such as behavioral therapy, which may have higher success rates than medication for some disorders such as overactive bladder [9].

Given less than optimal success rates for conventional therapy and the growth of widespread CAM use among women, CAM use is likely common and underreported among women with PFD. The purpose of this study was to compare CAM use between women presenting for routine gynecological care and women presenting to specialty urogynecology clinics. Our null hypothesis was that CAM use was not different between women with and without PFD.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Human Research Review Committee at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC). Women presenting to specialty urogynecology clinics (Urogyn) at UNMHSC or a private clinic in Santa Fe, and those presenting to a general gynecology clinic (Gyn) at UNMHSC between September 2008 and April 2009 were asked to complete an anonymous survey regarding CAM use. Women were eligible to participate if they were able to read English or Spanish, aged 18 or older, and were not pregnant. The survey included questions regarding age, marital status, ethnicity, income, education level, menopausal status, and parity. Income and education were dichotomized into two groups (income level above and below the poverty level defined as an annual income of $25,000, education levels equal to or below high school and above high school). Because this was an anonymous minimal risk observational study, women were not required to sign written consent.

Validated questionnaires evaluated presence and severity of pelvic floor disorders and included the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Scale, and question #35 from the Epidemiology of Prolapse and Incontinence Questionnaire (EPIQ). The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire is a symptom severity scale measuring the presence and severity of UI. Total scores are computed by multiplying the score for the first question by the score for the second question. Incontinence severity is rated on a point scale (0=dry, 1–2=slight, 3–4=moderate, 6–8=severe) [10, 11]. The severity index has been validated against pad weights and urinary diaries of 237 incontinent women [11]. It is reliable and sensitive to change. Presence of any UI was defined as a score greater than 0 on the severity scale, while moderate to severe incontinence was defined as a score ≥3.

Women completed three out of five questions from the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Severity Scale to assess both the presence and severity of FI [12]. The scale is sensitive to change and correlated with findings of FI quality of life scales in 152 anally incontinent women [13]. Each response to the incontinence questions was assigned a numeric value from 0–4 (0=never, 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=usually, 4= always). The numeric values from each question were then added together for a final score ranging from 0–12. FI was defined as a score greater than 4, and excluded women with only flatal incontinence.

Presence of POP was defined as an affirmative answer to Question #35 from the EPIQ questionnaire “Do you have a sensation that there is a bulge in your vagina or something is falling out from your vagina?” The EPIQ questionnaire has proven validity and reliability and has a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of >70% for diagnosing POP [14]. This single question evaluating patients for presence of POP has been used in large epidemiological studies to identify women with moderate to severe POP [7].

Women were also asked if they had previously received treatment for bladder, bowel, or vaginal problems. Patients who had tried previous treatments were asked specifically about surgery, physical therapy, dietary changes, pelvic floor exercises, medication, and pessary use.

Questions on the survey regarding CAM use were formulated after review by experts in CAM and treatment of PFD, and review of similar surveys administered in other clinical populations. In addition, a search of web-based information was performed using the terms “alternative medicine”, “herbal remedies”, “bladder dysfunction”, “incontinence”, “bowel incontinence”, “vaginal complaints”, and “complementary and alternative medicine”. Results of this search informed the list of herbal remedies queried for treatment of bowel, bladder, and vaginal complaints. The list of alternative therapies included representative therapies from the five major areas of CAM treatments identified by the NCCAM including whole medical systems, mind body medicine, biologically based principles, manipulative and body based practices, and energy medicine [1]. Patients were given a list of CAM therapies and asked if they had (a) never heard of them, (b) heard of them but never tried them, (c) used them in the past, but not currently using, and (d) used them in the past 2 months. CAM use was dichotomized into two categories (1) current or past use and (2) never used. Patients were also asked whether or not they were willing to try specific CAM therapies. Herbal supplement use for bladder, bowel, or vaginal problems was assessed by asking patients to identify herbs used from a list. They were also offered a place to write in a supplement not listed. Final content was reviewed by an expert panel, and adjusted for completeness. The survey was then trialed in ten women for comprehension and ease of completion. Non-validated portions of the survey were written at a seventh grade reading level as determined by the Flesch-Kincaid reading score. Missing answers were considered negative responses.

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) were used to describe patient characteristics including age, parity, and menopausal status. For comparisons between Urogyn and Gyn patients, Fisher’s exact test was used to compare groups, and t tests were used for comparison of continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to control for baseline differences between groups. Prior to conducting surveys, we determined that a sample size of 234 Urogyn patients and 103 general gynecology patients were needed to detect a 20% difference in CAM use between these two populations with 80% power and α =0.05 [15–19].

Results

Two hundred and thirty seven Urogyn and 103 Gyn patients gave data. Urogyn patients were older, more likely to be menopausal, more parous, had more Hispanic and Native American participants, were less likely to be educated beyond high school, and were more likely to have incomes below the poverty level than Gyn patients (Table 1). All further analyses are controlled for baseline differences between groups, and p values reflect adjusted values.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by clinic type

| Urogyn (n=237) | Gyn (n=103) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age±SDa(years) | 53.9±14.8 | 36.7±11.3 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic and Native American (%) | 117 (49) | 36 (35) | 0.04 |

| Education above high school (%) | 140 (59) | 86 (83) | <0.001 |

| Married (%) | 118 (50) | 47 (46) | 0.48 |

| Income <$25,000 annually (%) | 114 (48) | 26 (25) | <0.001 |

| Mean parity±SDa | 2.8±1.9 | 1.5±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Menopause (%) | 95 (40) | 12 (12) | <0.001 |

SD standard deviation

As expected, Urogyn patients were more likely to report moderate to severe UI (36.7% vs. 18.5%, p=0.04), FI (26.2% vs. 2.9%, p<0.001), and POP (37.6% vs. 9.7%, p= 0.003) compared to Gyn patients. Urogyn patients were also more likely to report that they had previously received treatment for a bladder, bowel, or vaginal problems (62% vs. 8.7%, p<0.001). Use of prescription medications (43.5% vs. 4.9%, p<0.001), surgery (35.4% vs. 0, p< 0.001), pessaries (22.4% vs. 1.9%, p=0.002), pelvic floor exercises (54.9% vs. 26.2%, p<0.001), dietary changes (27.9% vs. 12.6%, p=0.002), and physical therapy (28.2% vs. 2.9%, p<0.001) were greater in Urogyn patients.

Forty-five percent of all patients (both Urogyn and Gyn) surveyed reported either past or current CAM use for a bladder, bowel, or vaginal problem. Increasing age was independently associated with increased CAM use (p= 0.04). Ethnicity, income, education level, menopausal status, and marital status did not predict CAM use. Previous treatment for a bowel, bladder, or vaginal problem was also positively associated with CAM use. Women who reported that they had tried previous treatment used higher rates of CAM than women who had not tried previous treatment (59.6% vs. 32.6%, p<0.001). Women who had used medications (56.5% vs. 39.7%, p=0.02) and physical therapy (61.4% vs. 40.7%, p=0.006) were more likely to use CAM. Previous surgery was not associated with increased CAM use when controlling for baseline differences between patients.

Urogyn patients were more likely to use and more willing to try CAM therapies than Gyn patients even when controlling for baseline differences between groups (Table 2). Specifically, Urogyn patients reported increased use of counseling, meditation, and prayer compared to Gyn patients (Table 3). Urogyn patients also reported more willingness to try homeopathy (Table 4). Urogyn and Gyn patients reported similar rates of herbal remedy use. However, Urogyn patients identified specific herbal supplements used with increased frequency than Gyn patients (29.1% vs. 6.8%, p= 0.002). Herbal supplements used by patients for the treatment of bladder, bowel, or vaginal problems included cranberry (17.6%), green tea (10.6%), Gingko (5.9%), Ginseng (5.3%), St. John’s wort (4.1%), lemon grass (2.9%), Valerian (2.9%), and Kava (2.1%).

Table 2.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by clinic

| CAM use (%) | Urogyn (n=237) | Gyn (n=103) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAM use | 120 (51) | 33 (32) | 0.006 |

| Willingness to use CAM | 179 (76) | 62 (60) | 0.001 |

All p adjusted for baseline differences between groups with multivariable logistic regression

Table 3.

Specific complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use by clinic type

| CAM therapy (%) | All (n=340) | Urogyn (n=237) | Gyn (n=103) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins | 82 (24) | 58 (24) | 24 (23) | NS |

| Herbal remedies | 59 (17) | 46 (19) | 13 (13) | NS |

| Acupuncture | 23 (7) | 16 (7) | 7 (7) | NS |

| Counseling | 32 (9) | 28 (12) | 4 (4) | 0.03 |

| Massage | 28 (8) | 20 (8) | 8 (7) | NS |

| Osteopathy | 1 (.3) | 1 (.4) | 0 | NS |

| Chiropractic | 14 (4) | 12 (5) | 2 (2) | NS |

| Naturopathy | 10 (3) | 6 (3) | 4 (4) | NS |

| Meditation | 25 (7) | 25 (11) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Hypnosis | 6 (2) | 6 (3) | 0 | NS |

| Hypnotherapy | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | 0 | NS |

| Yoga | 21 (6) | 16 (7) | 5 (5) | NS |

| Reflexology | 8 (2) | 6 (3) | 2 (2) | NS |

| Homeopathy | 12 (4) | 10 (4) | 2 (2) | NS |

| Reiki | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | 0 | NS |

| Therapeutic touch | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | NS |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 13 (4) | 11 (5) | 2 (2) | NS |

| Ayurveda | 4 (1) | 4 (2) | 0 | NS |

| Prayer | 78 (23) | 66 (28) | 12 (12) | 0.004 |

All p adjusted for baseline differences between groups with multivariable logistic regression

Table 4.

Willingness to try specific complementary alternative medicine (CAM) therapies by clinic type

| Willingness to try CAM therapies (%) | All (n=340) | Urogyn (n=237) | Gyn (n=103) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins | 208 (61) | 153 (65) | 55 (53) | 0.12 |

| Herbal remedies | 189 (56) | 139 (59) | 50 (49) | 0.10 |

| Acupuncture | 133 (39) | 98 (41) | 35 (34) | 0.25 |

| Counseling | 131 (39) | 101 (43) | 30 (29) | 0.07 |

| Massage | 164 (48) | 122 (51) | 42 (41) | 0.052 |

| Osteopathy | 87 (26) | 66 (28) | 21 (20) | 0.07 |

| Chiropractic | 104 (31) | 78 (33) | 26 (25) | 0.053 |

| Naturopathy | 92 (27) | 65 (27) | 27 (26) | 0.47 |

| Meditation | 125 (37) | 93 (39) | 32 (31) | 0.15 |

| Hypnosis | 103 (30) | 76 (32) | 27 (26) | 0.20 |

| Hypnotherapy | 105 (31) | 77 (32) | 28 (27) | 0.24 |

| Yoga | 129 (38) | 90 (38) | 39 (38) | 0.37 |

| Reflexology | 119 (35) | 86 (36) | 32 (31) | 0.056 |

| Homeopathy | 117 (34) | 88 (37) | 29 (28) | 0.05 |

| Reiki | 86 (25) | 64 (27) | 22 (21) | 0.11 |

| Therapeutic touch | 111 (33) | 81 (34) | 30 (29) | 0.052 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 111 (33) | 82 (35) | 29 (28) | 0.07 |

| Ayurveda | 82 (24) | 59 (25) | 23 (22) | 0.35 |

| Prayer | 153 (45) | 115 (49) | 38 (37) | 0.14 |

All p adjusted for baseline differences between groups with multivariable logistic regression

Because a significant proportion of women in Gyn clinics reported at least one PFD (n=27, 26%), we then evaluated differences in CAM use between women with and without PFD. Thirty one percent of patients surveyed reported moderate to severe UI, 29.1% had POP, and 19.1% of patients had FI. Patients who reported moderate to severe UI used CAM at similar rates as women who reported no or slight UI (50% vs. 42.7%, p=0.36). Patients who reported POP also used CAM at similar rates as women without POP (53.5% vs. 41.5%, p=0.08). However, women with FI used CAM more frequently than women without FI (58.5% vs. 41.8%, p=0.04). Women with moderate to severe UI and women with FI reported increased willingness to try CAM than women without either disorder (all p<0.05). POP did not affect willingness to try CAM.

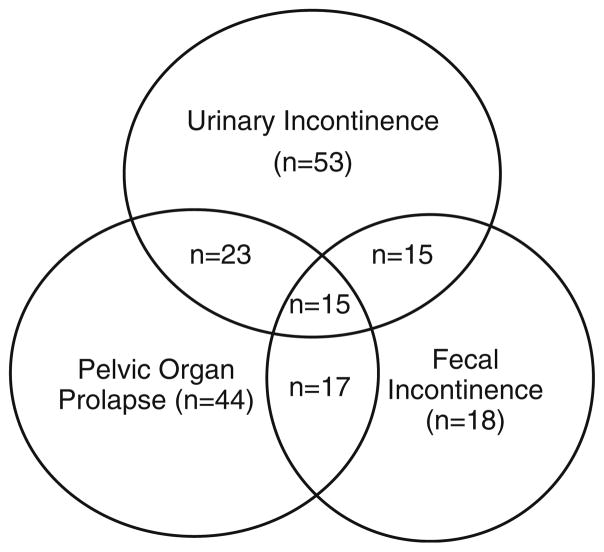

Since patients often reported more than one type of pelvic floor disorder (Fig. 1), we were unable to compare CAM use between types of disorder. Instead, we divided patients into categories based on number of pelvic floor disorders reported (Table 5). Increasing number of pelvic floor disorders was associated with increased CAM use and increased willingness to try CAM.

Fig. 1.

Number of women with pelvic floor disorders; n number with disorder

Table 5.

Number of pelvic floor disorders (PFD) and complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use

| No PFD (n=155) | 1 PFD (n=115) | 2 PFD (n=55) | 3 PFD (n=15) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAM use | 61 (39) | 52 (45) | 28 (51) | 12 (80) | 0.02 |

| Willingness to use CAM | 98 (63) | 85 (74) | 45 (82) | 13 (87) | 0.002 |

All p adjusted for baseline differences between groups with multivariable logistic regression

Discussion

We found that urogynecology patients were significantly more likely to report current or past CAM use and willingness to try CAM therapies than women reporting for routine gynecological care. We also found that women with FI were more likely than women without FI to report CAM use. Finally, increasing number of PFD was associated with increased CAM use and willingness to try CAM therapies. By the time patients are referred to a specialty clinic, they have often tried and failed multiple other therapies for their medical problem, which may explain higher reported use of CAM. In fact, any patient in our study population who had tried previous therapies for bowel, bladder, or vaginal problems were more likely to use CAM than those who had not tried previous therapies.

In contrast to other studies that have found increased rates of CAM use with higher education and income levels and no association with age, increased age was the only patient characteristic influencing CAM use in our patient population [4]. The differences in these findings may be related to the how questions were asked and the type of CAM therapies evaluated in previous studies.

While herbal remedy use was similar between Urogyn and Gyn patients, more Urogyn patients identified specific herbal supplements used. Cranberry was the most commonly identified supplement. Cranberry products are effective at reducing the incidence of urinary tract infections especially in women with recurrent infections, and patients seen at our Urogyn clinics are routinely offered cranberry tablets for infection prophylaxis [20]. This may account for the increased prevalence of cranberry use in our urogynecological patient population but does not explain differences observed between overall CAM use and willingness to try other CAM therapies.

Patients in our study also used St. John’s wort, kava, gingko, and ginseng, which can have significant impact on surgical complications. Kava prolongs anesthesia time, causes perioperative hypotension, increases drowsiness with narcotic administration, and has hepatotoxic side effects [21]. St. John’s wort is associated with hypotension under general anesthesia and has been linked to serotonin syndrome when used in combination with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [22]. Cranberry juice, ginseng, and St. John’s wort can interfere with anticoagulation therapies [23]. Gingko has demonstrated anti-platelet activity and has been reported to cause severe bleeding when taken in conjunction with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [24]. The American Society for Anesthesiologists recommends that herbal supplements be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to elective procedures due to potential anesthetic and perioperative complications. Since an estimated 10% of women have surgery in their lifetime for a PFD with 30% undergoing two or more surgical procedures, it is important to elicit information regarding herbal use in patients with PFD [8].

Prayer, meditation, and counseling were all more commonly used among Urogyn patients compared to Gyn patients. There are few studies addressing alternative therapies in treating pelvic floor disorders. We could find no literature specifically addressing prayer, meditation, or counseling in the treatment of pelvic floor disorders. However, there are studies addressing acupuncture, hypnotherapy, and chiropractic treatments. A randomized trial found that acupuncture specific for the bladder improved symptoms when compared to sham acupuncture therapy in a trial of 74 women [25]. Another study evaluated the use of hypnosis for urge incontinence in 50 women. After 12 sessions of hypnosis, 86% of patients experienced improvement in symptoms or were symptom free [26]. The use of ischemic compression over the bladder in a chiropractic clinic performed on 24 patients with urinary incontinence demonstrated a subjective decrease in urinary incontinence symptoms at 3 and 6 month intervals following treatment [27]. Given the difficulty of curing pelvic floor disorders with conventional medicine and willingness to use CAM in our study population, these alternative therapies warrant further investigation as adjuvant therapy for pelvic floor dysfunction.

Strengths of our study include use of a comparative group of patients presenting for gynecological care. Although these women differed significantly in multiple baseline characteristics, we did control for these differences in our analyses and found relatively high use in both patient populations. Weaknesses include lack of physical exam to confirm questionnaire findings although others have argued that patient assessment of symptoms may be more relevant to patient care than objective findings [28]. While associations between groups can be established in this type of study design, limitations include lack of identifiable causation.

Alternative therapies appear to be an underutilized treatment strategy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction. For example, few patients in our study have tried acupuncture or hypnosis despite their proven benefits in treating overactive bladder and urge incontinence [25, 26]. Health care providers may be hesitant to recommend CAM given the limited information available about specific CAM therapies, lack of provider training in CAM, as well as preconceived notions that CAM therapies are not valid. One study addressing medical student attitudes toward CAM found that increased time at medical school decreased medical student desire to train in CAM, to refer patients for CAM, and the belief the CAM should be available from the National Health Service [29]. Many patients seek medical advice from a licensed health care provider. Lack of support and recommendation of CAM therapies is a barrier to CAM utilization in patients who may be willing to try alternative therapies and benefit from their use.

Women with pelvic floor disorders frequently use CAM to treat their bladder, bowel, and vaginal problems and are willing to try CAM therapies. Research needs to be undertaken exploring the efficacy of specific alternative therapies in treating PFD so that practitioners are able to offer patients a variety of treatment options in addition to conventional therapies.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest Rebecca G Rogers has received grant support from Pfizer, has served on a speaker’s bureau and advisory board, and has provided consulting services. She also has served as a consultant for American Medical Systems. Yuko Komesu has received grant support from Pfizer; Tola Omotosho has received grant support from Pfizer. The work in this manuscript has been supported by a DHHS/ NIH/NCCR/GCRC Grant #5 M01-RR-00997. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Shannon L. Slavin, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC 10-5580, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA

Rebecca G. Rogers, Email: rrogers@salud.unm.edu, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC 10-5580, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA

Yuko Komesu, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC 10-5580, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA.

Tola Omotosho, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC 10-5580, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA.

Sarah Hammil, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC 10-5580, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA.

Cindi Lewis, Christus St Vincent Regional Medical Center, 465 St Michaels DR, Suite 202, Santa Fe, NM 87505, USA.

Robert Sapien, Department of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC 10-5560, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA.

References

- 1.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Available from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/html.

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States: prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328 (4):246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palinkas LA, Kabongo ML. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by primary care patients. A SURF*NET study. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(12):1121–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Gruenigen VE, White LJ, Kirven MS, Showalter AL, Hopkins MP, Jenison EL. A comparison of complementary and alternative medicine use by gynecology and gynecologic oncology patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11(3):205–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chez RA, Jonas WB. Complementary and alternative medicine. Part II: clinical studies in gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997;52(11):709–716. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199711000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgio KL. Influence of behavior modification on overactive bladder. Urology. 2002;60(5 Suppl 1):72–76. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01800-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):900–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanley J, Capewell A, Hagen S. Validity study of the severity index, a simple measure of urinary incontinence in women. BMJ. 2001;322(7294):1096–1097. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(1):77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(12):1525–1532. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Buckwalter JG, Burchette RJ, Nager CW, Luber KM. Epidemiology of prolapse and incontinence questionnaire: validation of a new epidemiologic survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(4):272–284. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H. Sample size calculations in clinical research. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Agostino RB, Chase W, Belanger A. The appropriateness of some common procedures for testing the quality of two independent binomial populations. Am Stat. 1998;42(3):198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachin JM. Biostatistical methods. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machin D, Campbell M, Fayers P, Pinol A. Sample size tables for clinical studies. 2. Blackwell Science; Malden: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jepson RG, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD001321. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raduege KM, Kleshinski JF, Ryckman JV, Tetzlaff JE. Anesthetic considerations of the herbal, kava. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16 (4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannel M. Drug interactions with St. John’s wort: mechanisms and clinical implications. Drug Saf. 2004;27(11):773–797. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 84: prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):429–440. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263919.23437.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardiner P, Phillips R, Shaughnessy AF. Herbal and dietary supplement-drug interactions in patients with chronic illnesses. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emmons SL, Otto L. Acupuncture for overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):138–143. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000163258.57895.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman RM, Baxby K. Hypnotherapy for incontinence caused by the unstable detrusor. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284 (6332):1831–1834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6332.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hains G, Hains F, Descarreaux M, Bussieres A. Urinary incontinence in women treated by ischemic compression over the bladder area: a pilot study. J Chiropr Med. 2007;6(4):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jcme.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elkadry EA, Kenton KS, FitzGerald MP, Shott S, Brubaker L. Patient-selected goals: a new perspective on surgical outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1551–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00932-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furnham A, McGill C. Medical students’ attitudes about complementary and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(2):275–284. doi: 10.1089/10755530360623392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]