In the wake of the Connecticut school shooting, a public dialogue emerged about the accessibility of mental health (MH) care in the United States. Policy makers have called for a more critical examination of the MH treatment system, and advocates are rallying around federal legislation that would strengthen community-based MH services -- especially for children and adolescents.1 Although the implementation of recent federal policies (i.e., Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and the Affordable Care Act) will expand insurance coverage for MH disorders among many U.S. children, these expansions will not improve access if communities lack a sufficient infrastructure to serve those in need of care.

Mental health facilities that provide outpatient specialty services for youth comprise a critical element of the treatment infrastructure for those with MH problems, especially for youth who are living in poverty, uninsured, and/or publicly insured. To inform the current dialogue, we present data from the 2008 National Survey of Mental Health Treatment Facilities (NSMHTF) and examine the extent to which gaps exist in this infrastructure. The NSMHTF is a national facility-level survey of entities that provide specialty MH services such as psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment centers, freestanding outpatient clinics/partial care facilities, and multiservice MH facilities.2 A response rate of 74% was achieved from the 13,068 facilities that were surveyed. Results from supplemental analyses restricting the sample of counties to those with complete facility-level data were similar to those presented below.

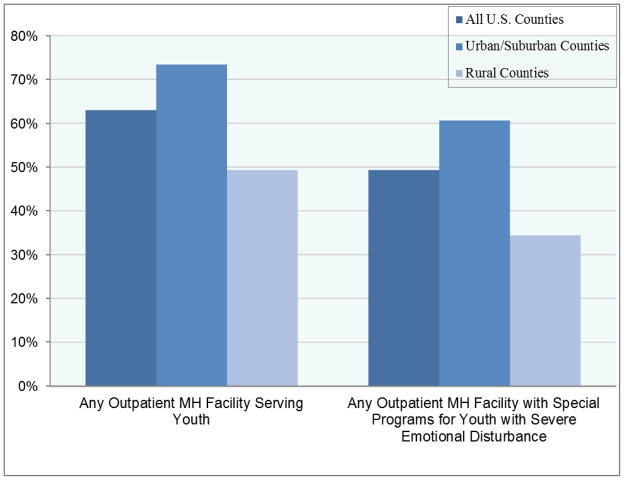

Using these data, we examine the percentage of U.S. counties that have at least one outpatient MH facility offering: (1) services for children and adolescents; and (2) any specially designed programs to treat youth with the most severe MH problems (i.e., severe emotional disturbance). Only 63% of U.S. counties have a MH facility that provides outpatient treatment for children/adolescents, and fewer than half of U.S. counties have a MH facility with any special programs for youth with severe emotional disturbance. [Figure] These gaps in infrastructure are especially pronounced in rural communities; fewer than half of rural counties have a MH facility that provides outpatient treatment for children/adolescents and only one-third have an outpatient facility with special programs for youth with severe emotional disturbance.

Figure 1. Percentage of U.S. Counties with Outpatient Facilities Providing MH Specialty Services to Youth.

Notes: Data from the 2008 National Survey of Mental Health Treatment Facilities

All Counties: N=3,143; Urban/Suburban Counties: N=1,787; Rural Counties N=1,356

These data likely represent conservative estimates of the extent of the problem because state funding for MH services has been reduced since 2008. Between 2009 and 2012, states eliminated more than $1.6 billion in general funds from their state MH agency budgets.3 These budgetary reductions have resulted in decreased services for children and adults with serious mental illness and closures of community MH programs, especially in states that have consistently reduced their budgets since 2009.3

These gaps in the MH facility infrastructure are part of a larger problem of geographic access to MH services for those with limited financial resources. Although some youth may seek treatment from MH clinicians in solo or small group practices, the accessibility of these services is limited for youth who are either uninsured or publically insured. For example, only 3% to 8% of patient caseloads for psychiatrists in solo or group practice, respectively, are covered by Medicaid.4

While services delivered through school-based MH programs could help address geographic and financial barriers to the MH care system, many school systems have also faced substantial budgetary reductions since the economic downturn;5 these budgetary reductions have affected the availability of school-based MH programs. Even if schools can offer MH services, they may lack the resources and personnel necessary to provide comprehensive services for youth with severe emotional disturbance for whom medication, intensive psychotherapy services, or both may be indicated.

One option for addressing these gaps in geographic accessibility for low-income youth is to expand the capacity of primary care safety-net facilities such as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) or rural health clinics (RHC) to provide youth MH services. Nearly three-fourths of counties have at least one of these clinics,6 most of which offer some type of MH services.7 Rural communities, in particular, may have the capacity to support these primary care facilities even if they do not have the capacity to support a specialty MH treatment facility. However, these primary care safety-net facilities typically care for patients with less severe MH disorders,7 suggesting that they may require additional resources to be able to provide comprehensive services to youth with the most severe MH problems. Telepsychiatry programs are one promising approach for providing specialty expertise for the treatment of complex patients in these primary care facilities.

In addition to expanding the number of facilities that can provide MH services for children, efforts to improve access will also need to address the national shortage of MH providers – especially those who specialize in providing services to youth. The Health Resources and Services Administration has designated four-fifths of U.S. counties as partial or whole Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas.6 Policy makers should work to ensure there is an adequate workforce to serve this population through mechanisms such as supplementary training grants and loan forgiveness programs.

The delivery system reforms considered above are necessary but not sufficient to ensure access to needed MH services for youth. Research has shown that knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and stigma about MH problems and treatment greatly affect whether, when, and how youth access the treatment system.8 Many youth do not receive treatment for MH problems because they and/or their parents do not perceive a need for services, do not believe treatment will be helpful, or they are worried about what others will think if they receive treatment. Educational outreach efforts about MH problems and available treatment options are key tools for overcoming these gaps in knowledge and attitudes. School health curricula should be expanded to better address mental health problems and treatments.

Although the implementation of recent federal policies expands insurance coverage for MH problems among many youth, the data presented above highlight large gaps in geographic access to a critical element of the MH infrastructure for youth with severe MH problems. These structural problems in access are compounded by ongoing shortages of MH providers, lack of knowledge about MH problems and available treatments, and stigma. The national dialogue that emerged from the Connecticut school shooting has provided an opportunity to address these challenges and achieve meaningful improvements in our children’s MH system. Improving access to MH services for this vulnerable population will require an ongoing national dialogue, sustained commitment from policy makers, and a comprehensive approach that addresses the complex array of barriers to treatment that exist in the current system.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions by Ewout van Ginneken, Michelle Ko, and Lindsay Allen. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (1K01MH09582301).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Viebeck E, Baker S. The Hill. Washington D.C: 2012. Advocates for mental health care have momentum after Connecticut Massacre. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Mental Health Services. 2008 National Survey of Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honberg R, Kimball A, Diehl S, Usher L, Fitzpatrick M. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Nov, 2011. State Mental Health Cuts: The Continuing Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs S, Wilk J, Chen D, Rae D, Steiner J. Datapoints: Medicaid as a payer for services provided by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Serv. 2005 Nov;56(11):1356. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliff P, Mai C, Leachman M. New School Year Brings More Cuts in State Funding for Schools. Washington D.C: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Sep 4, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Area Resource File (ARF) Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells R, Morrissey JP, Lee IH, Radford A. Trends in behavioral health care service provision by community health centers, 1998–2007. Psychiatr Serv. 2010 Aug;61(8):759–764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Paradise M, et al. Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: a focus on ethnic minority youth. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002 Feb;70(1):44–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]