Abstract

Inhibitors of bacterial DD-peptidases represent potential antibiotics. In the search for alternatives to β-lactams, we have investigated a series of compounds designed to generate transition state analogue structures on reaction with DD-peptidases. The compounds contain a combination of a peptidoglycan-mimetic specificity handle and a warhead capable of delivering a tetrahedral anion to the enzyme active site. The latter include a boronic acid, two alcohols, an aldehyde and a trifluoroketone. The compounds were tested against two low molecular mass class C DD-peptidases. As expected from previous observations, the boronic acid was a potent inhibitor, but, rather unexpectedly from precedent, the trifluoroketone [D-α-aminopimelyl-(1,1,1-trifluoro-3-amino)butan-2-one] was also very effective. Taking into account competing hydration, the trifluoroketone was the strongest inhibitor of the Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase, with a subnanomolar (free ketone) inhibition constant. A crystal structure of the complex between the trifluoroketone and the R39 enzyme showed that a tetrahedral adduct had indeed formed with the active site serine nucleophile. The trifluoroketone moiety, therefore, should be considered along with boronic acids and phosphonates, as a warhead that can be incorporated into new and effective DD-peptidase inhibitors and therefore, perhaps, antibiotics.

The bacterial DD-peptidases are of considerable importance in medical practice since they are the targets of β-lactam antibiotics. (1) These enzymes catalyze the final transpeptidation reaction in the biosynthesis of bacterial cell walls and are essential to bacterial survival. The β-lactams, acting as mechanism-based/transition state analogue inhibitors (2–4), are precisely structured to inactivate DD-peptidases in a manner that these enzymes have been unable to escape through evolution of a hydrolytic pathway. Bacteria have, however, been able to achieve resistance to β-lactams in a number of ways unrelated to DD-peptidase active site structure, and, in particular through evolution of β-lactamases from DD-peptidases (2,4). The β-lactamases, unlike DD-peptidases, are able to catalyze rapid β-lactam hydrolysis and thus destruction of their antibiotic activity (5).

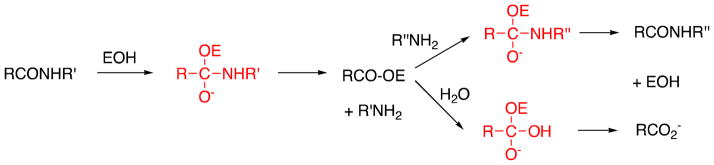

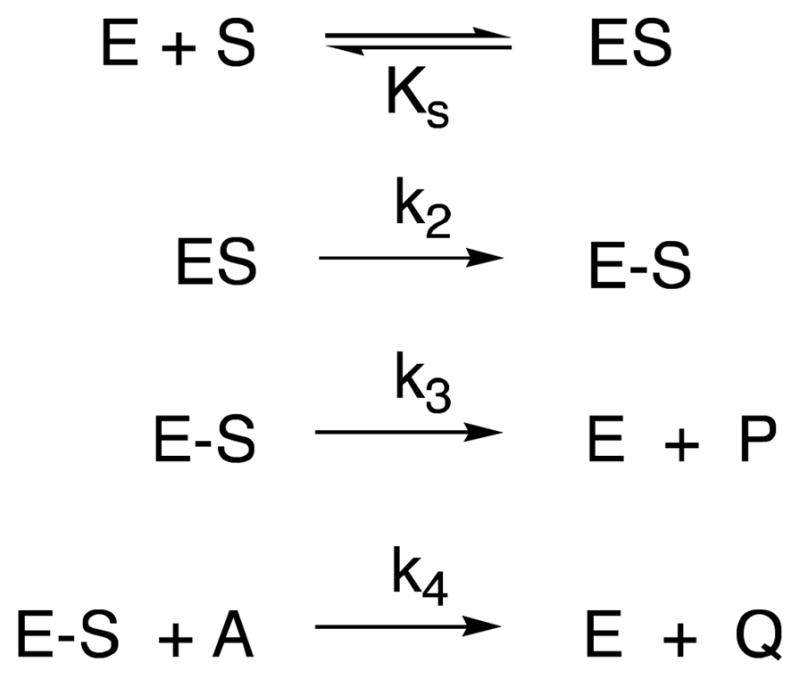

The rapid evolution of β-lactamases in response to new β-lactam antibiotics and also to β-lactam-based β-lactamase inhibitors (6–8), emphasizes the need for and stimulates the search for DD-peptidase inhibitors that are not β-lactam-based (9–15). One obvious approach is through transition-state analogues, since such molecules should, in principle, inhibit any enzyme (16–18). Since the reactions catalyzed by DD-peptidases in vivo are acyl-transfer reactions with a covalent acyl(serine)-enzyme intermediate (Scheme 1), substrate-based tetrahedral anions, covalently bound to the active site serine should be good analogues of the transition states of both acylation and deacylation steps. In principle, therefore the molecule 1, where “peptidoglycan” is a specific peptidoglycan, or peptidoglycan-mimetic fragment and X is a reactive moiety that generates a tetrahedral anion on reaction with the active site serine, would be the inhibitor of choice.

Scheme 1.

Approaches to 1 require the optimization of both “peptidoglycan” and X. One might expect that the former goal would be informed by studies of the substrate specificity of these enzymes, where a minimal, consensual, and thus broad spectrum peptidoglycan fragment would emerge. This goal has, however, not yet been achieved. It is true, of course, that peptidoglycan structure varies in detail between bacterial species, but even given this point, no consensual structure/class of privileged structures has emerged from consideration of DD-peptidase substrate specificity (19,20).

DD-Peptidases have been classified structurally into two groups, the low molecular mass (LMM)1 and high molecular mass (HMM) enzymes (21). The latter group is essential for bacterial growth and contains the killing targets of β-lactams. The former group are also inhibited by β-lactams but are not essential for bacterial survival, in the short term at least. Both groups of enzymes are believed to catalyze acyl-transfer reactions of peptidoglycan, viz. transpeptidase (HMM), carboxypeptidase and endopeptidase (LMM) reactions. Certain members of the LMM group, subclasses B and C, have been shown to have strong specificity for a free amine N-terminus in peptidoglycan substrates (19,22–27), but no strong specificity for any particular element of peptidoglycan has been demonstrated for the HMM enzymes (13,19,24,28,29). Design of transition state analogue inhibitors for the latter enzymes is thus difficult.

With respect to element X of 1, some advances have been made. In particular, boronic acids (Scheme 2) have been shown to be effective. Peptidoglycan-mimetic boronates have been found to be potent inhibitors of LMMC enzymes (13,20). The crystal structure of a complex of one such inhibitor, 2, with the LMMC Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase demonstrated the reason for its specificity (13). β-Lactam-mimetic boronic acids (bearing the amido side chains of classical β-lactam antibiotics rather than peptidoglycan) have also recently been found to be quite effective although studies of them are yet limited (11,12,31).

Scheme 2.

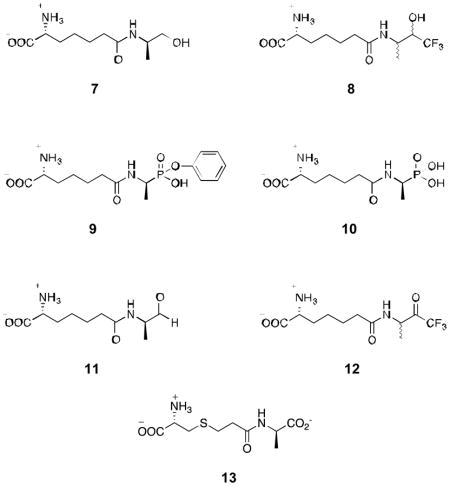

Beyond boronates, other sources of X, employed with a variety of serine hydrolases have been alcohols, phosphonates, aldehydes and trifluoroketones, yielding, in principle, the tetrahedral anions 3–6, respectively (32). Some assessment of the potential of these warheads with DD-peptidases has been made previously (14,33), although no indications of great potency have yet been observed. To date, the combination of the motifs 3–6, with a specific peptidoglycan fragment (as in 1) has not been investigated. In this paper, we present the synthesis and assessment of the inhibitory activity of 7–12 against representative LMMC DD-peptidases. We have discovered that the trifluoroketone 12 is a quite effective inhibitor of the Actinomadura R39 enzyme and present a crystal structure of its complex with this enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Commercially available reagents and solvents were purchased from Aldrich and Acros Organics, and used without purification, unless otherwise noted. D-Glutamic acid and N-(Z)-D-alanine were purchased from ChemImpex. Trifluoroacetaldehyde hydrate was purchased as a 75% solution in water from AlfaAesar. Compounds 24 (AlfaAesar), 25 and 27 were commercial products. The trifluoroketone 26 was synthesized in this laboratory by Dr. Abbas Shilabin. (Phenylacetyl)glycyl-D-thiolactate (14) and the boronic acid 2 were synthesized as previously described (30). The Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase and B. subtilis PBP4a were expressed and purified as described (34,35).

Varian Mercury 300 MHz and 400 MHz NMR spectrometers were used to collect 1H, 31P and 19F NMR spectra. Absorption spectra and spectrophotometric reaction rates were measured with Hewlett-Packard 8452A and 8453 spectrophotometers. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained from the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL. Routine ESI mass spectra were collected from a Thermo LCQ Advantage instrument. HPLC purification was achieved by a Varian ProStar unit equipped with a Varian ProStar model 340 UV/Vis detector and a Nucleosil® C-18 reverse phase column (Macherey-Nagel). Flash column chromatography was performed on Silicycle 60 Å, 32–63 μm silica gel.

Syntheses

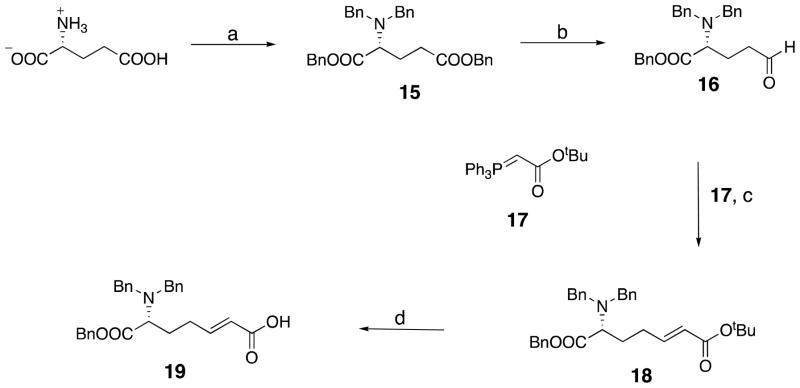

D-6-(N,N′-Dibenzylamino)-6-benzyoxylcarbonyl)-trans-hex-2-enoic acid 19 (Scheme 3)

Scheme 3.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) BnBr, NaOH, K2CO3, H2O, reflux, 60%; (b)DIBAL-H, Et2O, −78 °C, 65 %; (c) 17, THF, 25 °C, 1.5 h; (d) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 1 h, 90%.

N,N-Dibenzyl-D-glutamic Acid Dibenzyl Ester 15

This compound was synthesized following a previously reported general method (36). It was purified by chromatography on silica gel (hexane:ethyl acetate, 7:1) yielding the 15 as a colorless oil in 60% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 2.1 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.43, 2.56 (d quint, J = 9, 9 Hz, 2H,), 3.47 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.55, 3.93 (AB q, J = 13.5, 4H), 5.26 (AB q, J = 3 Hz, 2H), 5.20, 5.32 (AB q, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 7.25–7.46 (m, 20H).

D-4-(N,N-Dibenzylamino)-4-(benzyloxycarbonyl)butanal 16

To a stirred solution of 15 (3 g, 6 mmol, 1 equiv) in 30 mL of anhydrous diethyl ether under a nitrogen atmosphere was added DIBAL (1 M in hexane, 6.5 mL, 1.1 equiv) slowly at −78 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min, and then water (0.3 mL) added. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for an additional 30 min after which it was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and the volatiles evaporated, leaving a colorless gum, 16 (2.2 g), which was employed in the next step without purification. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ: 1.21 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.3–2.5 (m, 2H), 3.35 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.52, 3.86 (AB q, J = 13.5 Hz, 4H), 5.20, 5.26 (AB q, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H), 7.2–7.5 (m, 15H), 9.58 (s, 1H).

D-6-(N,N-Dibenzylamino)-6-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-trans-hex-2-enoic acid tert-butyl ester 18

To a stirred solution of 16 (2.0 g, 5 mmol, 1 equiv) in dry THF (20 mL) was added (t-butoxycarbonylmethylene)triphenylphosphorane 17 (Aldrich) (2.6 g, 6.8 mmol, 1.2 equiv) at room temperature. The reaction was stirred for 1.5 h after which solvent was removed by evaporation. The crude product was purified by chromatography on silica gel (hexane:ethyl acetate, 3:1), yielding the product 18 as a colorless oil (1.5 g, 60% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ: 1.47 (s, 9H), 1.86 (m, 2H), 2.07 (m, 1H), 2.32 (m, 1H), 3.34 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.53, 3.87 (AB q, J = 13.5 Hz, 4H), 5.19, 5.25 (AB q, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H), 5.59 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (quint, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.2–7.4 (m, 15H).

D-6-(N,N-Dibenzylamino)-6-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-trans-hex-2-enoic Acid 19

The ester 18 (0.5 g, 1 mmol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL). To this solution, stirred in an ice bath, trifluoroacetic acid (6 mL) was slowly added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature after which solvent was evaporated. After the residue was dried under vacuum, the product 19, was obtained as a gum (0.4 g, 90% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ: 1.86 (m, 2H), 2.07 (m, 1H), 2.32 (m, 1H), 3.34 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.53, 3.87 (AB q, J = 13.5 Hz, 4H), 5.19, 5.25 (AB q, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H), 5.59 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.7 (quint, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.2–7.4 (m, 15H). ES(+)MS m/z 444.4 (M + 1).

D-α-aminopimelyl-(1,1,1-trifluoro-3-amino)butan-2-one (Scheme 4)

Scheme 4.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) nitroethane, K2CO3, 50 – 60 °C, 3 h, 62%; (b) H2, 40 psi, 10% w/w PtO2, MeOH:CHCl3 (16:1), 12 h, 86%; (c) 19, HBTU, Et3N, 25 °C, 24 h, 80%; (d) Dess-Martin periodinane, TFA, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 3 h, 90%; (e) H2, 40 psi, 10% w/w Pd/C, MeOH, 12 h, 35%.

3-Nitro-1,1,1-trifluoro-2-butanol 20

This compound was prepared following the procedure reported by McBee et al. (37).

The product 20 was obtained as a yellow oil in 62% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 1.72 (d, 3H, J = 6 Hz), 3.2 – 3.6 (br. s), 4.76 – 4.92 (m, 2H).

3-Amino-1,1,1-trifluoro-2-butanol hydrochloride 21

This compound was prepared as a mixture of distereoisomers, following the procedure reported by Shao et al. (38). The colorless solid hydrochloride salt was obtained in 86% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, d6 DMSO), δ: 1.20 (d, 3H, J = 4.8 Hz), 1.27 (d, 3H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.40(m, 1H), 3.53(m, 1H), 4.14 (m, 1H), 4.38 (m, 1H), 8.06 (br. s, 3H), 8.22 (br. s, 3H).

D-1-[6-(N,N-Dibenzylamino)-6-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-trans-hex-2-enoyl-3-amino-1,1,1-trifluoro-2-butanol 22

To a mixture of D-1-[6-(N,N-dibenzylamino)-6-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-trans-hex-2-enoic acid 19 (488 mg, 1.1 mmol, 1 eq.) and 3-amino-1,1,1-trifluoro-2-butanol hydrochloride 21, dissolved in 10 ml of DMF, triethylamine (767 μL, 2.75 mmol, 2.5 eq.) was added followed by HBTU (1046 mg, 2.75 mmol, 2.5 eq.) at 0 – 5 °C. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 24 hours. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue dissolved in ethyl acetate. The organic solution was washed with 0.1 N hydrochloric acid, a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate, brine, and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (ethyl acetate/hexane) to give the product 22 in 80% yield as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 1.32 (d, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.76 (m, 2H), 2.06 – 2.16 (m, 1H), 2.25–2.36 (m, 1H), 3.32 (dd, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 3.46, 3.85 (AB q, 4H, J = 16 Hz), 4.07 (m, 1H), 4.28 (m, 1H), 4.83 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 4.91 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.21 (AB q, 2H, J = 16, 24 Hz), 5.40 (d, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 7.67 (m, 1H), 7.2–7.4 (m, 15 H).

D-1-[6-(N,N-Dibenzylamino)-6-(benzyloxycarbonyl)-trans-hex-2-enoyl-3-amino-1,1,1-trifluorobutan-2-one 23

To a stirred solution of 22 (380 mg, 0.67 mmol, 1 eq.) in dichloromethane (25 mL) at room temperature, Dess-Martin periodinane (850 mg, 2 mmol, 3 eq.) was added, followed by trifluoroacetic acid (150 μL, 2 mmol, 3 eq.) at room temperature. The reaction mixturewas stirred for three hours, after which it was quenched with sodium bicarbonate solution and extracted with ethyl acetate. After the drying and evaporation of the solvent, the crude product was purified on a silica gel column (ethyl acetate/hexane,1/1), and the product 23 was isolated in 90% yield as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 1.39 (d, 3H, J = 8 Hz), 1.46 (d, 3H, J = 8 Hz), 1.75 – 1.96 (m, 2H), 2.06 – 2.18 (m, 1H), 2.24 – 2.36 (m, 1H), 3.31 (m, 1H), 3.49, 3.86 (AB q, 4H, J = 16 Hz), 4.11 (m, 1H), 4.88 – 5.06 (2 × d, 1H, J = 8 Hz), 5.2 (AB q, 2H, J = 16, 24 Hz), 5.70 (d, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 7.69 (m, 1H), 7.23 s, 10H), 7.4 (s, 5H).

D-α-Aminopimelyl-(1,1,1-trifluoro-3-amino)butan-2-one 12

The required final product was prepared from 23 by catalytic hydrogenation overnight at 40 psi in 10 ml of MeOH with 10% Pd on carbon. After reaction, the solution was filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness to give a colorless solid. The crude product was dissolved in water and washed with ethyl acetate three times. The aqueous solution was separated and freeze-dried to give a colorless solid. This was purified by two passages through a Sephadex G10 size-exclusion chromatography column (water eluent). The product 12 was isolated in 35% yield as a colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O), δ: 1.06 (d,3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.22 (m, 2H), 1.46 (m, 2H), 1.70 (m, 2H), 2.12 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.56 (t, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 4.15 (q, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz).19F NMR (300 MHz, D2O) ppm - 82 (CF3). HRMS (ESI) [M+H]+ found 299.1220 (calc. 299.1219).

Syntheses of 7–11 are described in detail in Supporting Information.

Enzyme kinetics studies

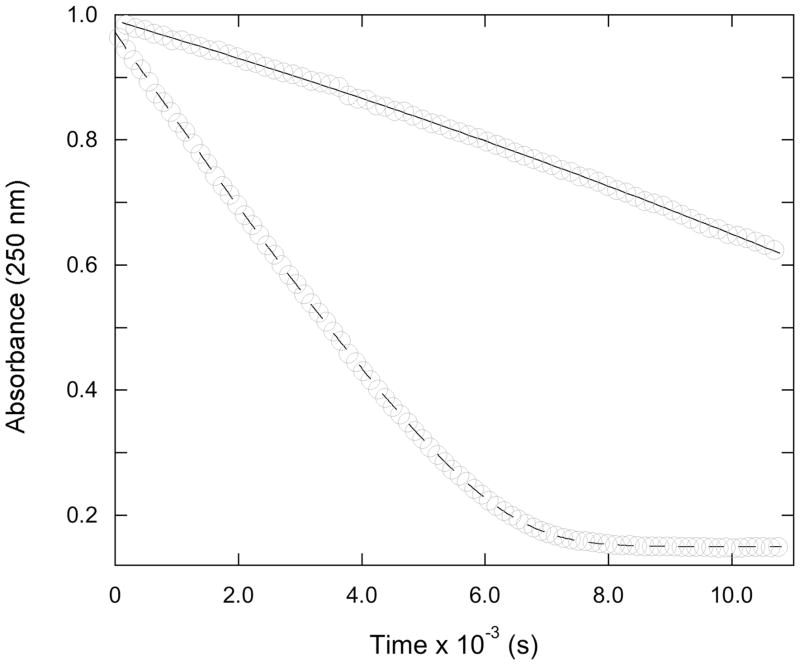

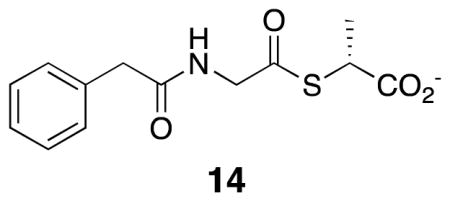

Inhibition of the Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase by compounds 7–12

In view of the nature of the inhibitors and all precedent (20,24–26), the inhibition was interpreted in all cases as purely competitive. Equilibrium constants for inhibition of the R39 DD-peptidase by the compounds 7 (0 – 3.0 mM), 10 (0 – 2.0 mM) and 11 (0 – 1.0 mM), 8 (0 – 400 μM), 9 (0 – 2.0 mM) and 12 (0 – 40 μM) were obtained from steady-state competition experiments where 14 was employed as a chromogenic (245 nm, Δε = 2500 cm−1M−1) substrate (0.5 mM). The reaction conditions were 20 mM MOPS buffer, pH 7.50, 25 °C, and an enzyme concentration of 210 nM. Under these conditions, the Km value of the substrate was 38.4 μM (25). Measurements of initial velocity vs concentrations of 7–11 were fitted to Scheme 5 and eq. 1 to obtain the Ki value. Total progress curves of inhibition of R39 DD-peptidase by compound 12 were fitted to Scheme 8 (see below) by the Dynafit program (39) to obtain the Ki value directly.

Scheme 5.

Scheme 8.

| (1) |

Inhibition of B. subtilis PBP4a by compounds 7–12

Equilibrium constants for inhibition of B. subtilis PBP4a by compounds 7–12 were obtained similarly to those for the R39 enzyme. The reaction conditions were 20 mM MOPS buffer, pH 7.50, 25 °C, and an enzyme concentration of 164 nM. Under these condition Km was (0.44 ± 0.08) mM for 14 as a substrate. The total progress curves for inhibition by compounds 8, (0 – 400 μM), 11 (0 – 1.0 mM), 12 (0 – 40 μM) were fitted to Scheme 5 by the Dynafit program (39) to obtain Ki values.

The Ki values for 24 – 27 with both enzymes were obtained from the measurement of initial rates at several concentrations of inhibitor in each case and application of eq. 1.

Kinetics of aminolysis of 14 by 7–10, catalyzed by the R39 DD-peptidase

Aminolysis of the substrate 14 by the amines 7–12, catalyzed by the R39 DD-peptidase, involves amine attack on the acyl-enzyme intermediate E-S (Scheme 6). The initial rates of reaction of 14, catalyzed by this enzyme, as a function of concentrations of 7–10 were fitted to Scheme 6 by the Dynafit program (39). These experiments were carried out in 20 mM MOPS buffer, pH 7.50, 25 °C, and with an enzyme concentration of 210 nM.

Scheme 6.

Crystallization, data collection and structure determination

Crystals of the enzyme were obtained by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 4 μL of a 25 mg mL−1 protein solution (also containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0), 2 μL of well solution (2.0 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M MES, pH 6), and 0.5 μL of 0.1 M CoCl2. Crystals were soaked in 6 μL of a solution containing 3.0 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M MES, pH 6, 0 and 0.5 μL of 0.5 M 12.

Data for the R39-12 crystals were measured on Beamline PROXIMA at SOLEIL (Paris, France) and processed using XDS. Molecular replacement processed with the native structure produced an interpretable density map, which clearly shows 12 in the four monomers of the asymmetric unit. Refinement was carried out with Refmac (40), Coot (41) and TLS (42) with final R and Rfree values of 19.3% and 23.7% Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inhibition of DD-Peptidases by Specific Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | R39 | PBP4a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (μM) | k4 (s−1 M−1) | Ki (μM) | |

| 2 | 0.032a (0.5)b 0.057 ± 0.001c |

NOd | 0.007 ± 0.001 |

| 7 | 6700 ± 100c (3000) | (6.1 ± 0.4) × 103 | >1000 (1000) |

| 8 | 1250 ± 50c,e (500) | (2.1 ± 0.1) × 104 | (110 ± 25)e (300) |

| 9 | NIc,f (2000) | (2.9 ± 0.1) × 102 | NDg |

| 10 | NIc (2000) | ≤ 1.0 × 102 | ND |

| 11h | (76 ± 13) (1000) | NO | (500 ± 150) (1000) |

| 12h | (0.37 ± 0.04)i (0.17 ± 0.02)c,i |

(2.2 ± 0.1) × 103 | (13.5 ± 0.3)i (300) |

| 13 | 480j | 3.0 × 103 j | ND |

Reference 30

Highest inhibitor concentration (μM) employed in parentheses

Fluorescence experiment (see text)

NO: No rate acceleration observed at highest concentration employed

Observed value divided by four, since it is assumed that only one of the four diastereomers present has significant activity (see text)

NI: No inhibition observed at the highest concentration employed

ND: Not determined

Ki values not corrected for hydration; see text for corrected values

Observed value divided by two, since it is assumed that only one of the two diastereomers present has significant activity (see text)

Reference 25

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of the new compounds 7–12 was achieved in a straight-forward fashion [Schemes 3,4, S1–S5 (Supporting Information)] via the versatile intermediate 19. They were all characterized by NMR and MS methods. All, along with the carboxylate 13 and the simple functional group analogues 24–27 were treated as rapid equilibrium competitive inhibitors of two LMMC DD-peptidases, the Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase and Bacillus subtilis PBP4a. No indications of slow binding were observed in any case. Values of the inhibition constant, Ki, obtained for 7 – 13, along with those for the boronate 2, previously determined (30), are as reported in Table 1.

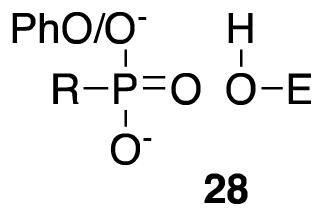

The alcohols 7 and 8 had very little inhibitory activity against either enzyme. Even the trifluoromethyl substituent of 8, which should reduce the alcohol pKa into a range where its anion would be accessible to the active site oxyanion hole, only produced a weak inhibitor of PBP4a. The configuration 3 of alcohols at the active site is therefore unfavorable. It should be noted in passing that the alcohol 8 was obtained as a mixture of four diastereoisomers in roughly equal amounts (see 19F NMR data in Supporting Information), only one of which would be expected to be an inhibitor (2R3S). Serine hydrolases, in general, are not efficiently inhibited by alcohols, even when specific (e.g. 43,44). The phosphonates 9 and 10 were also ineffective against the DD-peptidases. Presumably, the configuration 28 is not favorable either. A series of arylamidophosphonic acids was also found to lack significant inhibitory activity against the R39 DD-peptidase (12). Specific aryl phosphonate esters are known to be time-dependent covalent inhibitors of β-lactamases (45) and (weakly) of a LMMB DD-peptidase (46). No time-dependent inhibition of the present LMMC DD-peptidases by 9, however, was observed.

The carboxylate 13 is also a weak inhibitor of the R39 enzyme (Table 1). The trigonal carboxylate apparently does not sit well in the oxyanion hole. This is, in fact, seen in the crystal structure of a complex of the carba analogue of 13 with the R39 DD-peptidase (26), where the carboxylate is oriented away from the oxyanion hole. It is certainly reasonable that 13, the product of a DD-carboxypeptidase or endopeptidase reaction would be a poor inhibitor.

Both of the specific carbonyl compounds 11 and 12 are inhibitors of both LMMC enzymes. The trifluoroketone 12 is particularly effective [it is assumed that only one of the two diasteromers of 12, present in approximately equal amounts, has significant activity; this isomer, seen in the crystal structure described below, has D-stereochemistry at the ketone terminus]. It is likely (also see below) that these carbonyl compounds form the tetrahedral adducts, 4 and 5, respectively, at the active site. The greater effectiveness of the trifluoroketone is likely to be due in part to the higher alcohol acidity of the adduct (47), allowing thermodynamically more favorable formation of 6 than 5 at pH 7.5 [pKa values of trifluoroethanol and ethanol are 12.4 and 16 (48), respectively, favoring anion formation by the former by a factor of 103.6]. This factor is essentially sufficient to rationalize the higher inhibitory potency of 12 than 11.

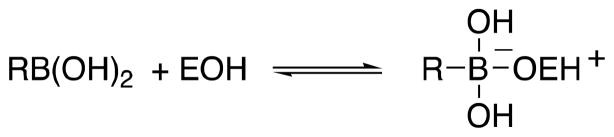

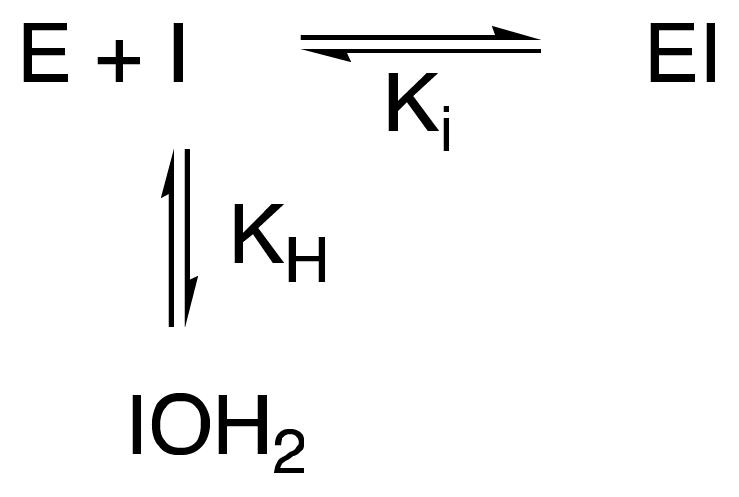

If it is assumed that the reacting species of 11 and 12 are the free carbonyls (47), then the observed or apparent Ki values of Table 1 should be corrected for the competing hydration in aqueous solution (Scheme 7) via eq 2, where Kiobs is the observed value. From 1H NMR spectra (not shown), KH for 11 is 30 and, therefore, from eq 2, the “real” Ki values for the carbonyl form of 11 are 2.5 μM and 16.1 μM, respectively, for the R39 DD-peptidase and PBP4a. The effect of hydration is even more dramatic with 12. Although estimates of KH for trifluoroacetone in the literature are curiously wide-ranging (47, 49,50), the lower limit estimate is 35 (49). If the additional effect of the amido substituent is included as a factor of 30 [estimated from the KH values of acetaldehyde (49) and 11], then a lower limit estimate of KH for 12 would be 1000. Certainly, we are unaware of any report in the literature of NMR observation of the carbonyl form of a α-trifluoro-α′-amidoketone in aqueous solution (e.g. 51,52). Thus Ki values for 12, corrected for hydration, can be estimated as 0.37 nM and 13.5 nM for the R39 DD-peptidase and PBP4a, respectively. These estimates represent upper limits and may be an order of magnitude larger than the real values. These carbonyl compounds are certainly powerful inhibitors of the LMMC DD-peptidases and, on reaction with the enzymes, may well generate structures resembling tetrahedral high-energy intermediates/transition states (see below).

Scheme 7.

| (2) |

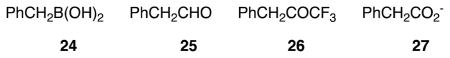

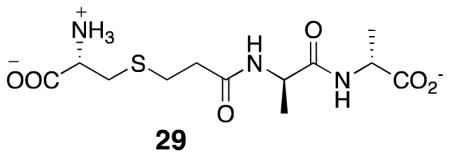

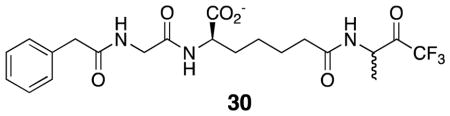

The lack of specificity of the trifluoromethyl moiety itself and the importance of the specific N-terminus is confirmed by the data of Table 2 where the effectiveness of the generic inhibitors 24 25, 26 and 27, bearing the “warheads” of 2, 7, 11, and 12, respectively, is displayed. Only 26 shows weak inhibition of the R39 DD-peptidase as do 24 and 26 of PBP4a.

Table 2.

Inhibition of DD-peptidases by Generic Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Ki (mM) | |

|---|---|---|

| R39 | PBP4a | |

| 24 | NIa (3.0)b | (0.23 ± 0.03) (3.0) |

| 25 | NI (2.5) | NDc |

| 26 | (0.27 ± 0.06) (2.0) | 5.0 ± 1.6 (3.0) |

| 27 | NI (2.5) | ND |

NI: no inhibition observed

Highest inhibitor concentration (mM) employed in parentheses

ND: not determined

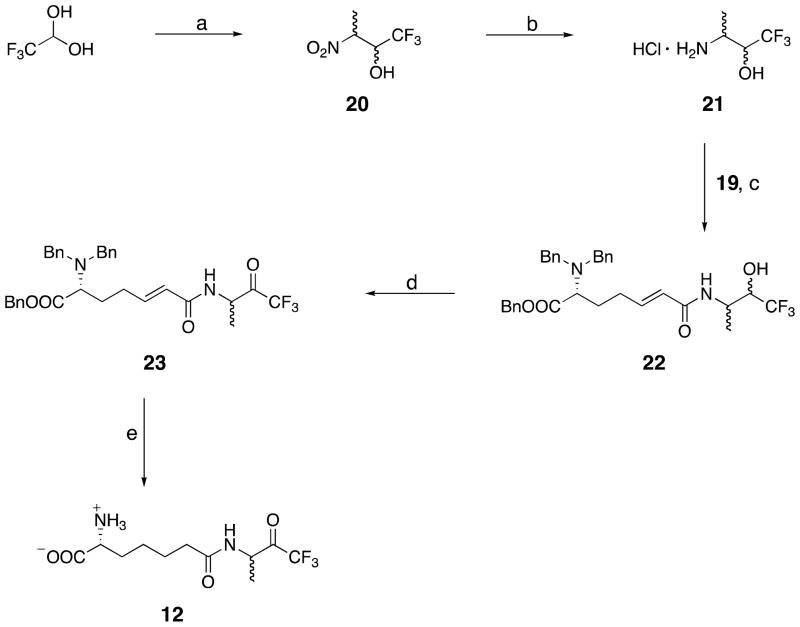

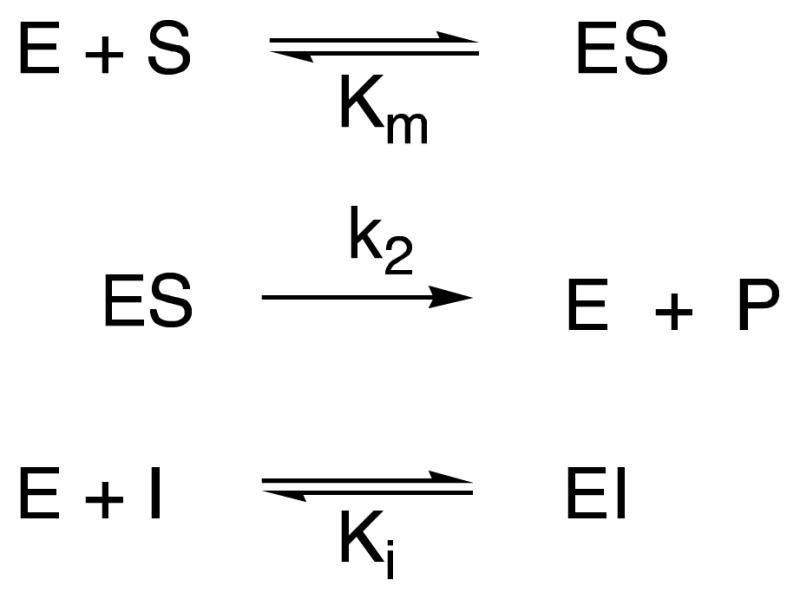

It was striking that the weaker “inhibitors”, of the R39 DD-peptidase, 7, 8, and 9, actually produced an increase in the initial rate of substrate turnover, as shown for 7 in Figure 1, for example. The likely explanation for this, with established precedent (25), is that, because of their free D-amino acid termini, these compounds may also act as acyl-acceptors and, in cases where enzyme deacylation is rate determining, as is presumably true for the thiolester 14, accelerates the observed reaction. Data such as in Figure 1 was fitted to Scheme 6 to obtain values for k4 (Table 1). Obviously, the k4 values for 7 and 8 are much higher than for the anionic 9 and 10 and are comparable to that (1.4 × 104 s−1M−1) of the best acceptor yet discovered for this enzyme, the good substrate 29 (25). It is, however, striking that the anionic terminal carboxylate 13 is so much a better acceptor than the equally anionic phosphonates 9 and 10. The ability of enzymes to bind carboxylates and phosph(on)ates differently has been noticed previously (53), although the functional significance of the distinction here is not evident.

Figure 1.

Progress curves showing turnover of the substrate 14 (0.5 mM) by the R39 DD-peptidase (0.21 μM) in the absence (dashed line) and presence (full line) of 12 (20 μM). The open circle points are experimental and the lines represent fits of the data to Scheme 8 (see text).

The acyl-acceptor ability of these inhibitors probably also led to the initially unexpected observation of an apparent decrease in the effectiveness of 12 as an inhibitor of the R39 DD-peptidase as a function of time in experiments with the substrate 14 (Figure 2). This phenomenon can be interpreted in terms of Scheme 8, which was fitted to data such as shown in Figure 2 (fit shown). The product of reaction of 12 with the substrate 14, Q, which presumably is 30, must be a weak inhibitor of the R39 enzyme. Acylation of 12 by 14 would lead to a gradual depletion of the inhibitor in solution and thus to decreasing inhibition with time (Figure 2). The Ki value for 12 reported in Table 1 derives from the fits of these data. This phenomenon was not observed in the experiments with 12 and PBP4a or with 11 and both enzymes probably because of the higher concentrations of inhibitors required for the experiments, leading to smaller fractional depletions of the inhibitors in these cases.

Figure 2.

Effect of the alcohol 7 on initial rates of turnover of the thiolester substrate 14 (0.5 mM) catalyzed by the R39 DD-peptidase. The points are experimental and the line represents the fit of the data to Scheme 6 (see text).

Because of the complication created by the ability of 7 and 8 to act as strong acyl group acceptors, their activity as inhibitors, although weaker than that of 2 and 12, could not be readily determined from experiments where turnover of substrate was monitored. Therefore, the binding strengths of 7 and 8 were determined from the inhibition of their irreversible inactivation of the R39 enzyme with cefotaxime, monitored fluorimetrically (54). These measurements showed that 7 and 8 did in fact bind very weakly [(at millimolar concentrations (Table 1)]. The fluorescence inhibition method was checked with 2 and 12, with acceptable results (Table 1).

It is also striking that 11 and 12 are more effective inhibitors of the R39 enzyme than of PBP4a. This may relate to the same order of reactivity of specific substrates with these enzymes (20). On the other hand, the analogous boronate 2 is a stronger inhibitor of PBP4a than of the R39 enzyme. The latter difference, however, may relate to the interesting observation that the binding of 2 to PBP4a is a slow (minutes; two step?) process (20), whereas its binding to the R39 enzyme is fast (with respect to manual mixing times). No time dependence in the inhibition of either of these enzymes by 11 and 12 was observed.

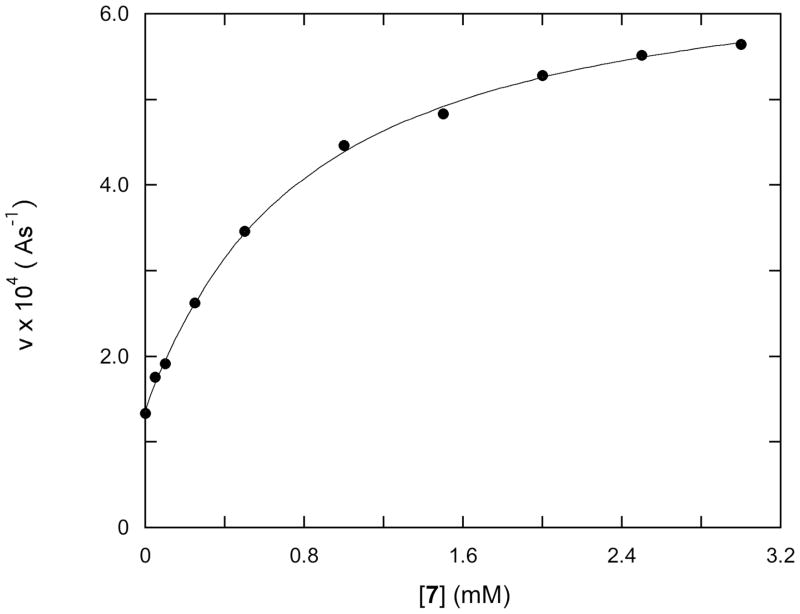

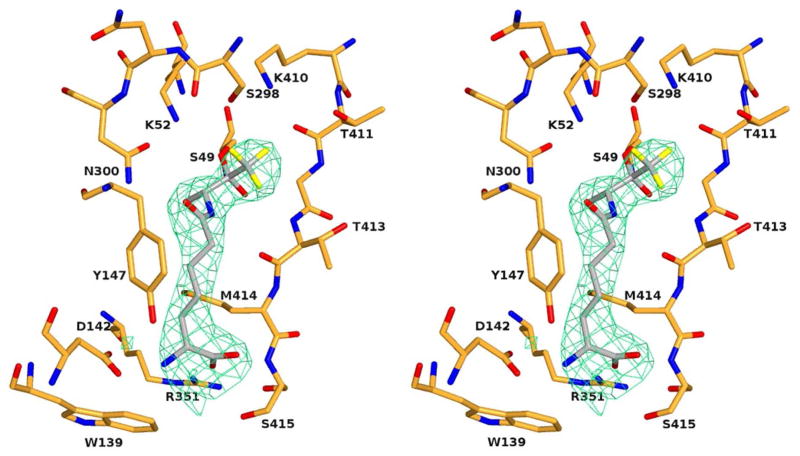

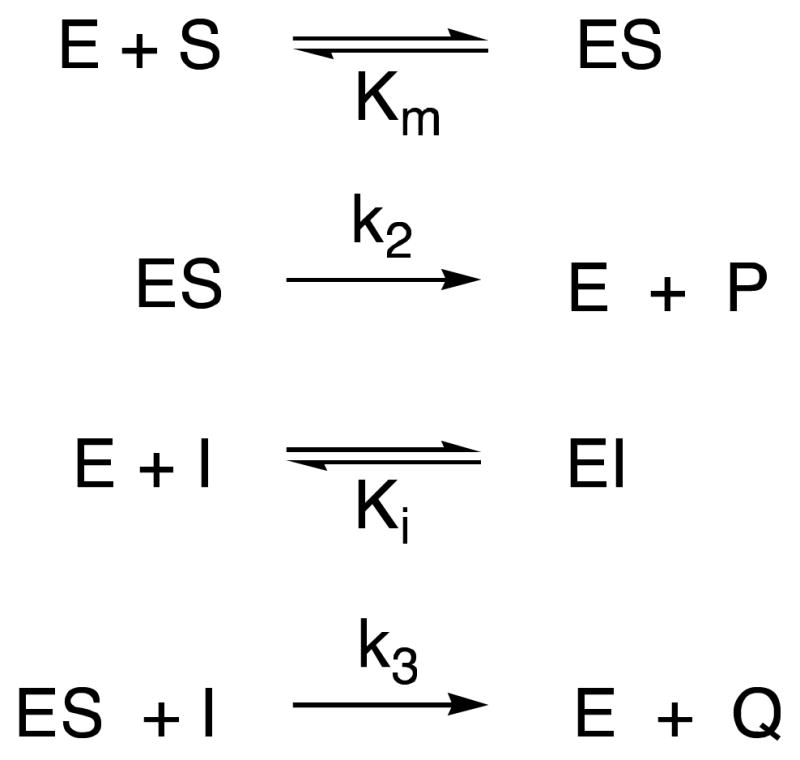

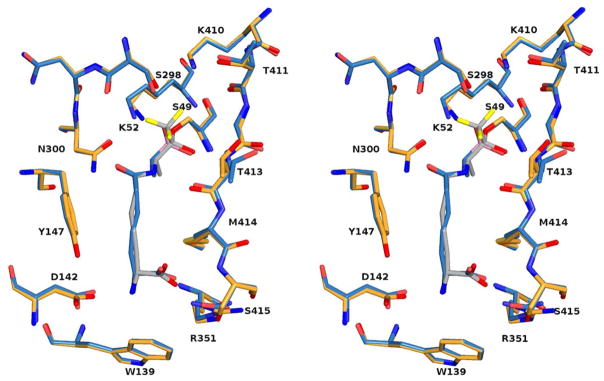

Crystal Structure of the Complex of the R39 DD-peptidase with 12

An X-ray diffraction study of the title complex was performed. Initial electron density maps resulting from the molecular replacement were excellent for the four protein monomers present in the asymmetric unit, allowing a precise localization of 12 in the active site of each monomer (Figure 3). The inhibitor 12 is covalently bonded to the active serine Ser49, the carbonyl carbon is now tetrahedral, and the ketone oxygen occupies the oxyanion hole, defined by the backbone NH groups of Ser49 and Thr413. The D-methyl group is directed into a hydrophobic pocket comprised residues Gly148, Leu 349 and Met414. As previously observed in the structures of the R39 enzyme with the boronic acid 2 (30), a cephalosporin or a peptide (26), each bearing an aminopimelic side chain, the aminopimelyl side chain runs along a hydrophobic groove and is fixed by a series of hydrogen bonds between the amido group and Asn300Nδ2 and Thr413O atoms, and between the terminal D-α-amino acid moiety and the Arg351 guanidinium, the Asp142 carboxylate and the Ser415 hydroxyl.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of the R39 DD-peptidase in complex with the specific trifluoroketone 12. In this stereoview, the electron density is a |Fo|−|Fc| difference map calculated from the final coordinates of the model refined in the absence of ligand. The resulting positive density is shown with green hatching and is contoured at 2.5 σ. The protein backbone and side chains are in orange and the trifluoroketone in grey. Heteroatoms are red (oxygen), blue (nitrogen), orange (sulfur) and yellow (fluorine). This figure was generated using PYMOL (www.pymol.sourceforge.net).

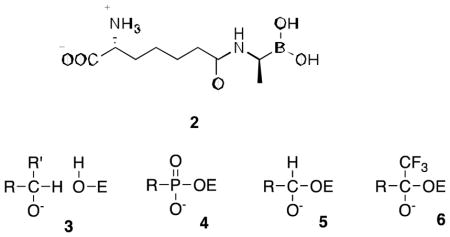

The most novel element of the structure is the position of the trifluoromethyl group and its interaction with the enzyme active site. Branching from the tetrahedral carbon bonded to Ser49Oγ, the CF3 group occupies the likely position of a leaving group in the tetrahedral intermediate of a peptidase substrate [and thus of one of the boronate hydroxyl groups in the analogous complex with 2 (30)]. An overlap of the active site elements of the boronate 2 complex and that of the trifluoroketone 12, both bearing a free D-α-aminopimelyl N-terminus, for which this enzyme is specific (20,24), is shown in Figure 4. The inhibitors are essentially identically placed in the active site, as would be expected of transition state analogs with such similar structure, with the CF3 group of 12 overlapping directly with the “leaving group” boronate hydroxyl. With respect to the position of the CF3 group, one O-C-C-F dihedral angle is 57°, indicating an essentially precise staggering of the fluorine atoms with respect to the oxyanion O−. This conformation would be expected, of course, on steric and electrostatic grounds and has been observed in serine protease/trifluoroketone complexes (for example, in reference 55). One fluorine atom is directed out of the active site into solvent where it might well interact with water molecules in the manner observed in a variety of crystal structures (55–58). Such interactions are probably more dipolar in nature than involving classical hydrogen bonding and are probably of ca 1 kcal/mol strength (59,60). The other two fluorine atoms appear to interact in a bifurcated fashion at a distance of 3.0 Å each with the hydroxyl of Ser298. This kind of arrangement has been previously observed, for example in a trifluoroketone adduct with chymotrypsin (55), where two fluorines interact with a water molecule, and in a thrombin complex where a similar interaction with a water molecule has been observed (57). It is interesting that the Lys52 terminal nitrogen has not moved closer than 4.0 Å distance to a fluorine atom. There are many examples of close NH---F interactions of < 3.0 Å in complexes of enzymes with fluorinated inhibitors (55–58,61). In the present case, the Lys52 amine would certainly be protonated, in a negatively charged transition state analog structure as it is and where it is strongly interacting with Ser49Oγ (2.9 Å) and Asn300Oδ (2.8 Å).

Figure 4.

Superimposition of the active site residues of the complex of 12 with the R39 DD-peptidase on those of the analogous complex with the boronic acid 2 (30). In this stereoview, the colors of the complex of 12 are as for Figure 3. The boronate complex is shown in blue except for the heteroatoms, which are as for Figure 3 and boron, which is in rose. This figure was generated using PYMOL (www.pymol.sourceforge.net). For Table of Contents Graphic only

A combination of the inhibition kinetics and the crystal structure, both discussed above, suggest that the trifluoromethyl moiety alone does not interact specifically and tightly with the DD-peptidase active site, but acts only as part of an electrophilic ketone that does react with the active site serine in a cooperative fashion with the specifically binding D-α-aminopimelyl N-terminus (26,27,30,62).

Conclusions

Compound 12 represents the first micromolar trifluoroketone inhibitor of a DD-peptidase. It owes its potency to the trifluoroketone moiety, elevating it over the less electrophilic aldehyde 11 and other tetrahedral species derived from 7–10, which occupy the active site less favorably. As shown by the very limited effectiveness of the generic analogues 24–27, it is clear that 12 is able to achieve its effectiveness only in combination with the strong specificity produced by the D-α-aminopimelyl terminus, whose affinity for certain LMMC DD-peptidases has been established. This combination of the trifluoroketone, which forms a tetrahedral adduct with the active site serine, and the D-α-aminopimelyl terminus into a complete inhibitor of the R39 DD-peptidase is seen very clearly in the crystal structure of the complex between the enzyme and 12. The trifluoroketone moiety and other activated carbonyls, therefore, should be considered along with boronic acids and phosphonates, as warheads that can be incorporated into new and effective DD-peptidase inhibitors and therefore, perhaps, antibiotics.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions (Å,°) | a=103.6, b=91.7, c=106.9, b=94.30 |

| Resolution range (Å)a | 48.9–2.6 (2.74–2.6) |

| No. of unique reflections | 61653 |

| Rmerge (%)a,b | 9.4 (63.2) |

| Redundancy a | 6.9 (6.9) |

| Completeness (%)a | 100 (100) |

| <I>/<δI> a | 13.5 (3.3) |

| Refinement: | |

| Resolution range | 47.9–2.6 |

| No. of non-hydrogen protein atoms | 13891 |

| No. of water molecules | 322 |

| R cryst (%) | 19.3 |

| R free (%) | 23.7 |

| RMS deviations from ideal stereochemistry | |

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 |

| bond angles (o) | 1.00 |

| Mean B factor (all atoms) (Å2) | 60.7 |

| Mean B factor (ligand) (Å2) | 45.0 |

| Ramachandran plot d: | |

| Favoured region (%) | 96.9 |

| Allowed regions (%) | 3.1 |

| outlier regions (%) | 0.0 |

| PDB code | 3zcz |

Statistics for the highest resolution shell are given in parentheses.

Rmerge = å | Ii −Im |/å Ii where Ii is the intensity of the measured reflection and Im is the mean intensity of all symmetry-related reflections. Figures within brackets are for the outer resolution shell.

Monomer A

Using program rampage (63)

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI-17986 (RFP) and in part by the Belgian Program on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction initiated by the Belgian State, Prime Minister’s Office, Science Policy programming (IAP no. P6/19), the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique, (IISN 4.4505.09, IISN 4.4509.11, FRFC 2.4511.06F) and by the University of Liège (Fonds spéciaux, Crédit classique, C-06/19 and C-09/75). CD and FK are research associates of the FRS-FNRS, Belgium

Abbreviations: DIBAL, diisobutylaluminum hydride; ESMS, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; HBTU: O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate; HMM, high molecular mass; HRMS, high resolution mass spectrometry; LMM, low molecular mass; MES, 4-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid; MOPS, 3-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; PBP, penicillin-binding protein; THF, tetrahydofuran.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Synthetic details for the preparation of the compounds 7 – 11. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Wise EM, Park JT. Penicillin: its basic site of action as an inhibitor of a peptide cross-linking reaction in cell wall mucopeptide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:75–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tipper DJ, Strominger JL. Mechanism of action of penicillins: a proposal based on their structural similarity to acyl-D-alanyl-D-alanine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:1133–1141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee B. Conformation of penicillin as a transition-state analog of the substrate of peptidoglycan transpeptidase. J Mol Biol. 1971;61:463–469. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratt RF. Functional evolution of the serine β-lactamase active site. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 2002;2:851–861. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frère J-M, editor. Beta-Lactamases. Nova; NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drawz SM, Bonomo RA. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:160–201. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bebrone C, Lassaux P, Vercheval L, Sohier JS, Jehaes A, Sauvage E, Galleni M. Current challenges in antimicrobial chemotherapy: focus on β-lactamase inhibition. Drugs. 2010;70:651–679. doi: 10.2165/11318430-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K, Macielag MJ. New β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2010;20:1277–1293. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2010.515588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miguet L, Zervosen A, Gerards T, Pasha FA, Luxen A, Distèche-Nguyen M, Thomas A. Discovery of new inhibitors of Streptococcus pneumoniae penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 2x by structure-based virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5926–5936. doi: 10.1021/jm900625q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turk S, Verlaine O, Gerards T, Zivec M, Humljan J, Sosic I, Amoroso A, Zervosen A, Luxen A, Joris B, Gobec S. New non-covalent inhibitors of penicillin-binding proteins from penicillin-resistant bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Contreras-Martell C, Amoroso A, Woon ECY, Zervosen A, Inglis S, Martins A, Verlaine O, Rydzik AM, Job V, Luxen A, Joris B, Schofield CJ, Dessen A. Structure-guided design of cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors that overcome β-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:941–951. doi: 10.1021/cb2001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woon ECY, Zervosen A, Sauvage E, Simmonds KJ, Zivec M, Inglis SR, Fishwick CWG, Gobec S, Charlier P, Luxen A, Schofield CJ. Structure guided development of potent reversibly binding penicillin binding protein inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:219–223. doi: 10.1021/ml100260x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dzhekieva L, Kumar I, Pratt RF. Inhibition of bacterial DD-peptidases (penicillin-binding proteins) in membranes and in vivo by peptidoglycan-mimetic boronic acids. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2804–2811. doi: 10.1021/bi300148v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shilabin AG, Dzhekieva L, Misra P, Jayaram B, Pratt RF. 4-Quinolones as non-covalent inhibitors of high molecular mass penicillin-binding proteins. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:592–595. doi: 10.1021/ml3001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedarovich A, Djordjevic KA, Swanson SM, Peterson YK, Nicholas RA, Davies C. High-throughput screening for novel inhibitors of Neisseria gonorrhoeae penicillin-binding protein 2. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pauling L. Molecular architecture and biological reactions. Chem Eng News. 1946;24:1375–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfenden R. Transition state analogues for enzyme catalysis. Nature. 1969;223:704–705. doi: 10.1038/223704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states and transition state analog design. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:693–720. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratt RF. Substrate specificity of bacterial DD-peptidases (penicillin-binding proteins) Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2138–2155. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7591-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemmara VV, Dzhekieva L, Sarkar KS, Adediran SA, Duez C, Nicholas RA, Pratt RF. Substrate specificity of low-molecular mass bacterial DD-peptidases. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10091–10101. doi: 10.1021/bi201326a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghuysen JM. Serine β-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:37–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JW, Pratt RF. Dipeptide binding to the extended active site of the Streptomyces R61 D-alanyl-D-alanine-peptidase: the path to a specific substrate. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12200–12209. doi: 10.1021/bi001295w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonough MA, Anderson JW, Silvaggi NR, Pratt RF, Knox JR, Kelly JA. Structures of two kinetic intermediates reveal species specificity of penicillin-binding proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JW, Adediran SA, Charlier P, Nguyen-Distèche M, Frère JM, Nicholas RA, Pratt RF. On the substrate specificity of bacterial DD-peptidases: Evidence from two series of peptidoglycan-mimetic peptides. Biochem J. 2003;373:949–955. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adediran SA, Kumar I, Nagarajan R, Sauvage E, Pratt RF. Kinetics of reactions of the Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase with specific substrates. Biochemistry. 2011;50:376–387. doi: 10.1021/bi101760p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauvage E, Powell AJ, Heilemann J, Josephine HR, Charlier P, Davies C, Pratt RF. Crystal structures of complexes of bacterial DD-peptidases with peptidoglycan-mimetic ligands; the substrate specificity puzzle. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauvage E, Duez C, Herman R, Kerff F, Parrella S, Anderson JW, Adediran SA, Pratt RF, Frère JM, Charlier P. Crystal structure of the Bacillus subtilis penicillin-binding protein 4a and its complex with peptidoglycan-mimetic peptide. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Josephine HR, Charlier P, Davies C, Nicholas RA, Pratt RF. Reactivity of penicillin-binding proteins with peptidoglycan-mimetic β-lactams: What’s wrong with these enzymes? Biochemistry. 2006;45:15873–15883. doi: 10.1021/bi061804f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar I, Josephine HR, Pratt RF. Reactions of peptidoglycan-mimetic β-lactamase with penicillin-binding proteins in vivo and in membranes. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:620–624. doi: 10.1021/cb7001347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dzhekieva L, Rocaboy M, Kerff F, Charlier P, Sauvage E, Pratt RF. Crystal structure of a complex between the Actinomadura R39 DD-peptidase and a peptidoglycan-mimetic boronate inhibitor: Interpretation of a transition state analogue in terms of catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6411–6419. doi: 10.1021/bi100757c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zervosen A, Bouillez A, Herman R, Amoroso A, Joris B, Sauvage E, Charlier P, Luxen A. Synthesis and evaluation of boronic acids as inhibitors of penicillin binding proteins of classes A, B, and C. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:3915–3924. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraut J. Serine proteases: structure and mechanism of catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:331–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pechenov A, Stefanova ME, Nicholas RA, Peddi S, Gutheil WG. Potential transition state analogue inhibitors for the penicillin-binding proteins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:579–588. doi: 10.1021/bi026726k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granier B, Duez C, Lepage S, Englebert S, Dusart J, Dideberg O, Van Beeumen J, Frère JM, Ghuysen JM. Primary and predicted secondary structures of the Actinomadura R39 extracellular DD-peptidase, a penicillin-binding protein (PBP) related to the Escherichia coli PBP4. Biochem J. 1992;282:781–778. doi: 10.1042/bj2820781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duez C, Van Hove M, Gallet X, Bouillene F, Docquier J-D, Brans A, Frère JM. Purification and characterization of PBP4a, a new low molecular-weight penicillin-binding protein from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1595–1599. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1595-1599.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriquez M, Taddei M. A simple procedure for the transformation of L-glutamic acid into the corresponding gamma-aldehyde. Synthesis-Stuttgart. 2005:493–495. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBee ET, Hathaway CE, Roberts CW. The ethanolysis of 1,1,1- trifluoro-2,3-epoxybutane and 2-methyl-1,1,1-trifluoro-2,3-epoxypropane. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:4053–4057. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao YM, Yang WB, Kuo TH, Tsai KC, Lin CH, Yang AS, Liang PH, Wong CH. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of trifluoromethyl ketones as inhibitors of SARS-CoV 3CL protease. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:4652–4660. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuzmic P. Program DYNAFIT for the analysis of enzyme kinetic data: application to HIV proteinase. Analyt Biochem. 1996;237:260–273. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–55. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–50. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bégué JP, Bonnet-Delpon D, Fischer-Durand N, Amour A, Reboud-Ravaux M. Stereoselective synthesis and inhibitor properties towards human leucocyte elastase of chiral β-peptidyl trifluoromethyl alcohols. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:1099–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potetinova JV, Voyushina TL, Stepanov VM. Enzymatic synthesis of peptidyl-amino aldehydes-serine proteinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1997;7:705–710. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahil J, Pratt RF. Mechanism of inhibition of the class C β-lactamase of Enterobacter cloacae P99 by phosphonate monoesters. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5869–5878. doi: 10.1021/bi00140a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silvaggi NR, Anderson JW, Brinsmade SA, Pratt RF, Kelly JA. The crystal structure of phosphonate-inhibited D-Ala-D-Ala peptide reveals an analogue of a tetrahedral transition state. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1199–1208. doi: 10.1021/bi0268955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen KN, Abeles RH. Inhibition kinetics of acetylcholinesterase with fluoromethyl ketones. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8466–8473. doi: 10.1021/bi00447a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jencks WP, Regenstein J. In: Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 3. Fassman GD, editor. Vol. 1. CRC, Cleveland, OH: Physical and Chemical Data; 1975. pp. 305–351. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guthrie JP. Carbonyl addition reactions: Factors affecting the hydrate- hemiacetal and hemiacetal-acetal equilibrium constants. Canad J Chem. 1975;53:898–906. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith RA, Copp LJ, Donnelly SL, Spencer RW, Krantz A. Inhibition of cathepsin B by peptidyl aldehydes and ketones: slow-binding behavior of a trifluoromethyl ketone. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6568–6573. doi: 10.1021/bi00417a056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imperiali B, Abeles RH. Inhibition of serine proteases by peptidyl fluoromethyl ketones. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3760–3767. doi: 10.1021/bi00361a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angelastro MR, Baugh LE, Bey P, Burkhart JP, Chen T-M, Durham SL, Hare CM, Huber EW, Janusz MJ, Koehl JR, Marquart AL, Mehdi S, Peet NP. Inhibition of human neutrophil elastase with peptidyl electrophilic ketones 2. Orally active PG-Val-Pro-Val pentafluoroethyl ketones. J Med Chem. 1994;37:4538–4554. doi: 10.1021/jm00052a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stamper CGF, Morello AA, Ringe D. Reaction of alanine racemase with 1-aminoethylphosphonic acid forms a stable external aldimine. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10438–10445. doi: 10.1021/bi980692s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuad N, Frère JM, Ghuysen JM, Duez C, Iwatsubo M. Mode of interaction between β-lactam antibiotics and the exocellular DD-carboxypeptidase-transpeptidase from Streptomyces R39. Biochem J. 1976;155:623–629. doi: 10.1042/bj1550623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brady K, Wei A, Ringe D, Abeles RH. Structure of chymotrypsin-trifluoromethyl ketone inhibitor complexes: comparison of slowly and rapidly equilibrating inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7600–7607. doi: 10.1021/bi00485a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernstein PR, Gomes BC, Kosmider BJ, Vacek EP, Williams JC. Nonpeptidic inhibitors of human leukocyte elastase. 6. Design of a potent, intratracheally active, pyridone-based trifluoromethyl ketone. J Med Chem. 1995;38:212–215.3. doi: 10.1021/jm00001a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salvagnini C, Michaux C, Remiche J, Wouters J, Charlier P, Marchand-Brynaert J. Design, synthesis and evaluation of graftable thrombin inhibitors for the preparation of blood-compatible polymer materials. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:4209. doi: 10.1039/b510239a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nielsen TK, Hildmann C, Riester D, Wegener D, Schwienhorst A, Ficner R. Complex structure of a bacterial class 2 histone deacetylase homologue with a trifluoromethylketone inhibitor. Acta Crystallogr, Sect F. 2007;63:270–273. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107012377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caminati W, Melandri S, Maris A, Ottaviani P. Relative strengths of the OH---Cl and OH---F hydrogen bonds. Ang Chem (Int Ed) 2006;45:2438–2442. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dalvit C, Vulpetti A. Intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds involving fluorine atoms: implications for recognition, selectivity, and chemical properties. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:262–272. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Majumdar S, Pratt RF. Intramolecular cooperativity in the reaction of diacyl phosphates with serine β-lactamases. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8293–8298. doi: 10.1021/bi900808x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, 3rd, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi, psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins. 2003;50:437–50. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.