Abstract

Purpose

Prostate cancer is a heterogenous disease with a variable natural history that is not accurately predicted by currently used prognostic tools.

Experimental Design

We genotyped 798 prostate cancer cases of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry treated for localized prostate cancer between June 1988 and December 2007. Blood samples were prospectively collected and de-identified before being genotyped and matched to clinical data. The survival analysis was adjusted for Gleason score and PSA. We investigated associations between 29 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and biochemical recurrence, castration-resistant metastasis, and prostate cancer-specific survival. Subsequently, we performed an independent analysis using a high resolution panel of 13 SNPs.

Results

On univariate analysis, 2 SNPs were associated (p<0.05) with biochemical recurrence; 3 SNPs were associated with clinical metastases; and 1 SNP was associated with prostate cancer-specific mortality. Applying a Bonferroni correction (p<0.0017), one association with biochemical recurrence (p=0.0007) was significant. Three SNPs showed associations on multivariable analysis, although not after correcting for multiple testing. The secondary analysis identified an additional association with prostate cancer-specific mortality in KLK3 (p<0.0005 by both univariate and multivariable analysis).

Conclusions

We identified associations between prostate cancer susceptibility SNPs and clinical endpoints. The rs61752561 in KLK3 and rs2735839 in the KLK2-KLK3 intergenic region associated strongly with prostate cancer-specific survival, and rs10486567 in 7JAZF1 gene associated with biochemical recurrence. A larger study will be required to independently validate these findings and determine the role of these SNPs in prognostic models.

Keywords: Single nucleotide polymorphisms, Prostate cancer, Prognosis

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a heterogenous disease with a variable natural history, and thus the optimal therapeutic approach may vary. Widespread use of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing has resulted in an increased rate of diagnosis of prostate cancer, so that a man’s risk over a lifetime now approaches 16%, while the lifetime risk of dying of the disease remains close to 3–4%.[1] PSA is a powerful prognostic biomarker,[2–3] but its limited predictive value is well documented. Germline genetic variation has the potential to identify predisposition to aggressive disease and to provide insight into biological pathways of initiation and progression of prostate cancer.

A variety of prediction tools are used in clinical practice to define the presentation of prostate cancer and tailor the treatment strategy. Nomograms incorporating PSA have been developed to predict the risk of prostate cancer at time of biopsy, biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy and after radiation therapy, metastatic progression and overall survival.[4] Despite reasonable discriminatory power and promising external validation studies, even the best clinical nomograms are limited in their prognostic capabilities. The widespread use of clinical multivariable prediction tools, and studies suggesting their superiority over clinical experience, supports their utility,[5] however, they have not been prospectively studied and may be improved by the incorporation of other factors including genetic markers.

A number of genetic variants have been associated with risk for prostate cancer, most notably BRCA2 mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at 8q24 and at least 20 additional SNPs at 10 different chromosomal loci.[6–17] This genetic variation may produce clinically useful biomarkers and reveal unappreciated disease biology. BRCA2 mutations have been associated with prostate cancer aggressiveness in a number of small studies,[18–20] but few of the susceptibility loci discovered by genome scans have been associated with clinical outcome.[21–23] In the current study, we investigated an association between 29 SNPs that have been associated with risk of prostate cancer, correlating these SNPs with clinical outcomes of 798 men with prostate cancer.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from 798 men treated for localized prostate cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between June 1988 and December 2007. All cases identified themselves as being of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Their medical records were collected as part of an institutional prostate cancer research database utilizing standardized questionnaires and chart abstraction forms, created and maintained by the prostate cancer disease management team at MSKCC. Analysis for this study was based on data on clinical stage, Gleason score (from needle biopsy), PSA levels, and age at diagnosis of the primary prostate cancer as well as dates of biochemical recurrence, development of castration-resistant metastasis, death due to prostate cancer, and overall survival. All patient records were reviewed by one physician to confirm the clinical endpoints being tested. Biochemical recurrence refers to the detection of rising PSA after local therapy, and was defined as a single measure of PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/ml after radical prostatectomy, and a value of ‘nadir+2’ after other therapy (table 1).[24–25] Castration-resistant metastases refers to time of progression of disease following initiation of anti-androgen therapy. Cause of death was determined from review of the death certificate and the medical record. In accordance with an Institutional Research Board approved protocol, patient identifiers were removed at time of genetic analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) or Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 68 (62, 73) |

| Pretreatment PSA (ng/ml) | 7.70 (4.85, 15.6) |

| Clinical stage | |

| T1 | 307 (38%) |

| T2 | 243 (30%) |

| T3/T4 | 119 (15%) |

| Unknown | 129 (16%) |

| Biopsy Gleason grade | |

| ≤ 6 | 296 (37%) |

| 7 | 302 (38%) |

| ≥ 8 | 177 (22%) |

| Unknown | 23 (3%) |

| Type of treatment | |

| Radical prostatectomy | 241 (30%) |

| Radiotherapy alone | 271 (34%) |

| Radiotherapy + hormones | 216 (27%) |

| Hormones alone | 35 (4%) |

| Watchful waiting | 34 (4%) |

| Chemotherapy alone | 1 (0.1%) |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 1987 to 1990 | 28 (4%) |

| 1991 to 1995 | 222 (28%) |

| 1996 to 2000 | 261 (33%) |

| 2001 to 2006 | 287 (36%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

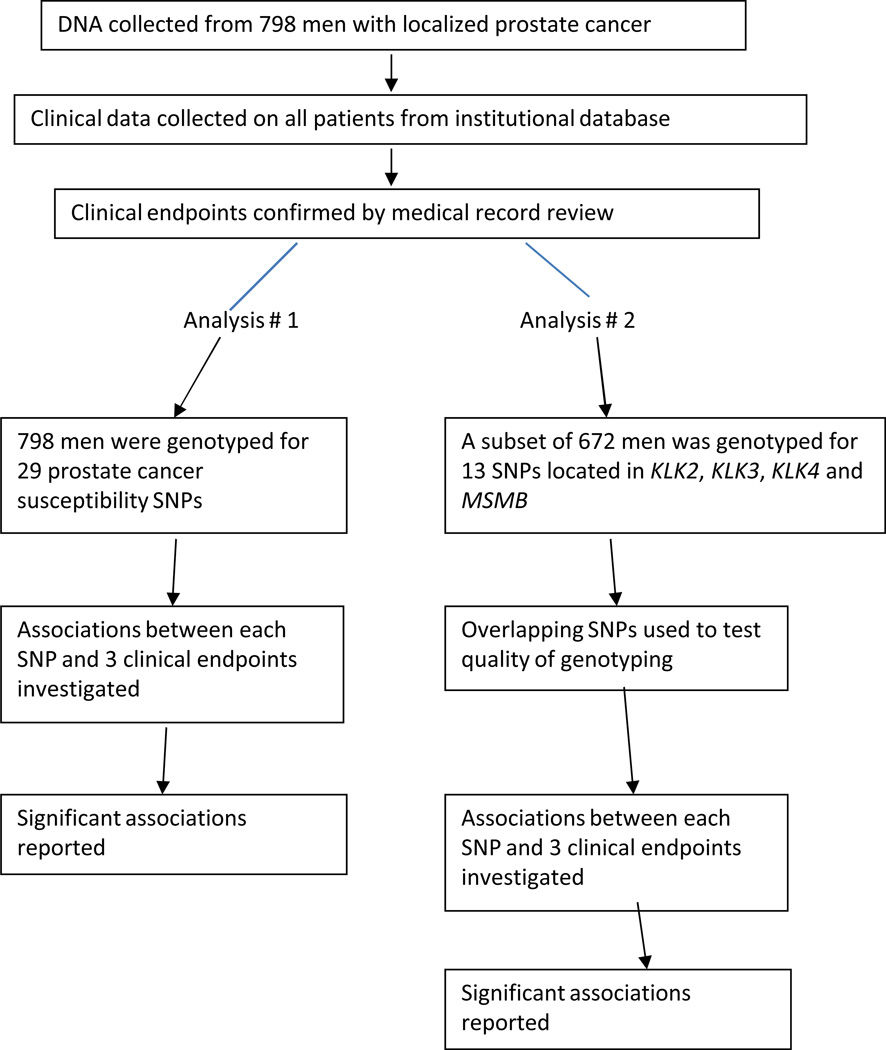

All blood samples were genotyped for 29 prostate cancer risk SNPs using a Mass ARRAY QGE iPLEX system (Sequenom, Inc)( Figure 1). The selected SNPs were previously associated with prostate cancer diagnosis in published genome-wide association studies or were SNPs of particular interest to our group. The primers were ordered from Sequenom Inc (San Diego, CA 92121). Overall genotyping rate for the 29 SNPs was 96% and each of the SNPs was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The minor allele frequency ranged from 4% to 47%. We performed a second, independent analysis at RSKC at the Wallenberg Research Laboratories, University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden, using a high resolution SNP panel with primers ordered from Sequenom Inc and genotyped individuals from the original cohort with sufficient DNA remaining (672 of 798 patients [84%]) for 13 SNPs using a new aliquot of DNA for each case. Two of these 13 SNPs were included in the analysis of 29 SNPs, and therefore serve as quality control of the genotyping. These 13 SNPs are located in the regions encoding 4 secretory products of the prostate: KLK2, KLK3, KLK4 and MSMB.[26]

Figure 1.

Study Schema

Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to investigate the association between each SNP and biochemical recurrence, castration-resistant metastases, and prostate cancer-specific mortality. Each SNP was analyzed under a co-dominant model, with the association determined from a global test for differences in outcome between the 3 genotypes (common homozygote, heterozygote, and rare homozygote), commonly referred to as a “2 degree of freedom test”. For illustrative purposes, we have also shown results from analyses where each SNP was analyzed under a log-additive (linear trend) model. The probability of freedom from the various events was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods. Time at risk was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of event or date of last contact, and patients without the event were censored at their last follow up date. For SNPs significant at p < 0.05 under the co-dominant model, multivariable analyses were conducted controlling for PSA (entered as a log-transformed continuous variable), clinical stage (categorized as T1, T2, and T3/4), and biopsy Gleason score (categorized as ≤ 6, 7, and ≥. Since patients received different forms of treatment which could possibly impact the results, we performed additional analyses according to primary treatment received (surgery or radiation therapy). Collection of blood samples for genetic testing began in 2000, and therefore some cases diagnosed before 2000, and who died before 2000 (or who did not participate in blood sampling), are not included in this cohort. This scenario is referred to statistically as “left truncation”, and as a sensitivity analysis we repeated all analyses by calculating time at risk from date of blood draw for genetic testing. Since it was possible for patients to die from other causes we repeated all analyses using a methodology which considers death from other causes as a competing risk.[27] P values were not corrected for multiple testing, as it was the intent for these results to be hypothesis generating. To address issues of multiple testing, by examining 29 SNPs and applying a Bonferroni correction, statistical significance was defined as p<0.0017. However, because the intent of this study was to be hypothesis generating, we also report all associations of potential interest for future validation. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Seven hundred and ninety-eight patients were genotyped. Patient characteristics are given in Table 1, and treatment at presentation was based on patient and physician preference. The majority of patients (92%) were treated with curative intent: 241 (30%) had radical prostatectomy and 487 (61%) had radiotherapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Most patients (75%) had biopsy Gleason score ≤ 7, and 46% of patients with available clinical staging information had T1 disease. At last follow up, 176 patients had died, with 91 having died from prostate cancer. The median follow up for survivors was 7.6 years. Biochemical recurrence was documented in 351 patients, and castration-resistant metastasis in 146 patients.

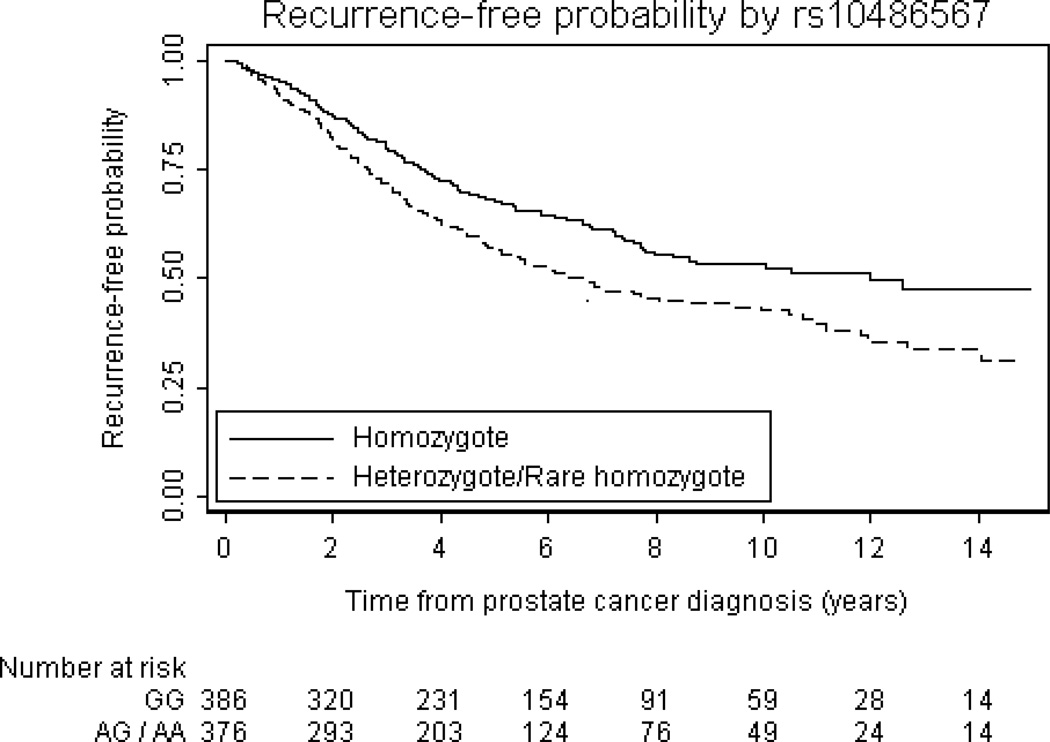

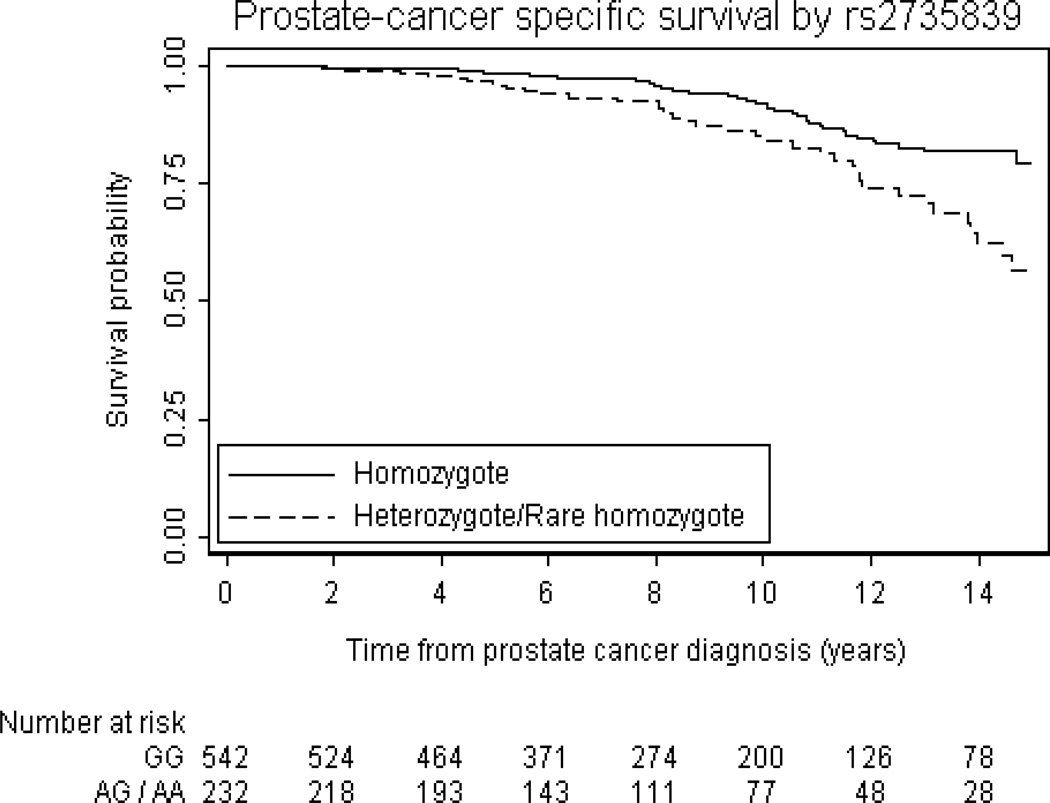

Univariate associations between the 29 SNPs and prostate cancer outcomes are summarized in Table 2. In the first analysis of 29 SNPs, 2 SNPs were associated with biochemical recurrence with p<0.05 (rs10486567, and rs7008482). Three SNPs were associated with castration-resistant metastases with p<0.05 (rs4962416, rs10486567, and rs6465657). One SNP was associated with prostate cancer-specific mortality with p<0.05 (rs2735839). For illustrative purposes, the probability of freedom from biochemical recurrence stratified by rs10486567 is given in figure 2, and the probability of freedom from prostate-cancer specific mortality stratified by rs2735839 is given in Figure 3. Of note, only 1 of these associations (between rs10486567 and biochemical recurrence) would have been significant had a formal Bonferroni correction for multiple testing been applied. There was little overlap between the SNPs associated with each outcome. For example, although rs2735839 was associated with prostate cancer-specific mortality (p=0.0017), there was no significant association with biochemical recurrence (p=0.7) or castrate-resistant metastasis (p=0.2). Hazard ratios were similar when subgroups defined by primary treatment received were analyzed, and we therefore saw no evidence that treatment impacted the results from the cohort when analyzed overall, e.g. rs10486567 and biochemical recurrence: HR for common heterozygote versus common homozygote: 1.79 (95% CI: 1.05, 3.06) for the surgery group and HR=1.90 (95% CI: 1.12, 3.20)for the radiation therapy group. Associations between the 29 SNPs and PSA, biopsy Gleason score, and clinical stage are given in the Supplemental Table.

Table 2.

Univariate associations between SNPs and prostate cancer outcomes under codominant model. Boldface represents SNPs with associations at p<0.05 by the “2 degree of freedom test”.

| SNP | Chromosomal region |

Number of Patients |

MAF | Published AF |

Genotype (% of patients) |

Biochemical Recurrence N=351 |

Clinical Metastases N=146 |

Prostate Cancer Specific Death N=91 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value1 | HR | 95% CI | P Value1 | HR | 95% CI | P Value1 | ||||||

| rs10090154 | 8q24 | 759 | 0.08 | NR | C/C (85) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| C/T (14) | 0.97 | 0.71, 1.32 | 0.75 | 0.45, 1.25 | 0.86 | 0.47, 1.58 | ||||||||

| T/T (1) | 0.6 | 0.08, 4.26 | 0.9 | * | * | 0.5 | * | * | 0.9 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.95 | 0.71, 1.27 | 0.7 | 0.72 | 0.44, 1.19 | 0.2 | 0.83 | 0.46, 1.51 | 0.5 | |||||

| rs1016343 | 8q24 | 749 | 0.23 | NR | C/C (60) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (36) | 0.96 | 0.76, 1.21 | 1.01 | 0.71, 1.45 | 0.88 | 0.55, 1.40 | ||||||||

| T/T (5) | 1.18 | 0.72, 1.94 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.44, 2.29 | 1 | 1.58 | 0.68, 3.68 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.01 | 0.84, 1.22 | 0.9 | 1.01 | 0.75, 1.35 | 1 | 1.05 | 0.73, 1.51 | 0.8 | |||||

| rs10486567 | 7 | 762 | 0.25 | 0.2 | G/G (51) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (42) | 1.37 | 1.09, 1.72 | 1.36 | 0.95, 1.95 | 1.06 | 0.67, 1.66 | ||||||||

| A/A (8) | 1.89 | 1.31, 2.74 | 0.0007 | 2.11 | 1.26, 3.55 | 0.014 | 1.56 | 0.80, 3.04 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.37 | 1.17, 1.62 | <0.0005 | 1.43 | 1.12, 1.83 | 0.005 | 1.18 | 0.86, 1.62 | 0.3 | |||||

| rs13254738 | 8 | 761 | 0.45 | 0.33 | A/A (29) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| C/A (52) | 0.97 | 0.75, 1.24 | 0.78 | 0.54, 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.64, 1.73 | ||||||||

| C/C (19) | 0.89 | 0.64, 1.22 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.45, 1.24 | 0.4 | 0.94 | 0.48, 1.83 | 0.9 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.94 | 0.81, 1.10 | 0.5 | 0.85 | 0.66, 1.09 | 0.2 | 0.98 | 0.71, 1.35 | 0.9 | |||||

| rs16901979 | 8q24 | 792 | 0.04 | 0.07 | C/C (93) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| C/A (7) | 1.14 | 0.77, 1.69 | 1.6 | 0.95, 2.69 | 1.06 | 0.51, 2.18 | ||||||||

| A/A (0.1) | 5.08 | 0.71, 36.30 | 0.2 | * | * | 0.2 | * | * | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.2 | 0.83, 1.76 | 0.3 | 1.48 | 0.89, 2.44 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.50, 2.07 | 1 | |||||

| rs1859962 | 17q24 | 765 | 0.44 | 0.49 | G/G (33) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| G/T (47) | 1.07 | 0.84, 1.36 | 1.15 | 0.79, 1.68 | 1.06 | 0.66, 1.69 | ||||||||

| T/T (20) | 0.95 | 0.70, 1.30 | 0.7 | 1.03 | 0.63, 1.70 | 0.7 | 0.84 | 0.44, 1.62 | 0.8 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.99 | 0.85, 1.15 | 0.9 | 1.04 | 0.82, 1.31 | 0.8 | 0.94 | 0.70, 1.28 | 0.7 | |||||

| rs2659056 | 19 | 731 | 0.27 | 0.25 | A/A (55) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (37) | 0.97 | 0.77, 1.23 | 0.98 | 0.68, 1.41 | 1.05 | 0.67, 1.66 | ||||||||

| G/G (8) | 0.95 | 0.61, 1.46 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.45, 1.81 | 1 | 1.03 | 0.44, 2.43 | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.97 | 0.82, 1.16 | 0.8 | 0.97 | 0.73, 1.27 | 0.8 | 1.03 | 0.74, 1.45 | 0.8 | |||||

| rs2660753 | 3p12 | 755 | 0.24 | 0.13 | C/C (57) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (36) | 0.98 | 0.78, 1.23 | 0.75 | 0.52, 1.07 | 0.73 | 0.46, 1.16 | ||||||||

| T/T (6) | 0.88 | 0.56, 1.38 | 0.8 | 0.59 | 0.27, 1.28 | 0.16 | 0.81 | 0.35, 1.90 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.96 | 0.80, 1.14 | 0.6 | 0.76 | 0.57, 1.01 | 0.055 | 0.82 | 0.57, 1.16 | 0.3 | |||||

| rs266849 | 19 | 764 | 0.24 | 0.19 | A/A (59) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (34) | 1.09 | 0.87, 1.37 | 1.31 | 0.93, 1.86 | 1.34 | 0.86, 2.09 | ||||||||

| G/G (7) | 0.88 | 0.56, 1.40 | 0.6 | 1.14 | 0.57, 2.27 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.85, 3.83 | 0.2 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.01 | 0.85, 1.20 | 0.9 | 1.17 | 0.90, 1.52 | 0.2 | 1.34 | 0.97, 1.85 | 0.075 | |||||

| rs4242382 | 8q24 | 759 | 0.8 | 0.14 | G/G (85) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (14) | 1.05 | 0.78, 1.41 | 0.77 | 0.47, 1.27 | 1 | 0.57, 1.78 | ||||||||

| A/A (1) | 1.13 | 0.36, 3.52 | 0.9 | * | * | 0.6 | * | * | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.05 | 0.80, 1.37 | 0.7 | 0.71 | 0.44, 1.14 | 0.16 | 0.91 | 0.53, 1.57 | 0.7 | |||||

| rs4430796 | 17q12 | 751 | 0.47 | 0.56 | G/G (29) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (49) | 0.82 | 0.64, 1.05 | 0.88 | 0.60, 1.29 | 1.22 | 0.73, 2.03 | ||||||||

| A/A (22) | 0.87 | 0.64, 1.18 | 0.3 | 0.87 | 0.54, 1.40 | 0.8 | 1.28 | 0.70, 2.33 | 0.7 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.92 | 0.79, 1.07 | 0.3 | 0.93 | 0.73, 1.17 | 0.5 | 1.13 | 0.85, 1.52 | 0.4 | |||||

| rs4962416 | 10q26 | 756 | 0.33 | 0.28 | T/T (46) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (42) | 0.94 | 0.75, 1.18 | 0.71 | 0.50, 1.01 | 0.8 | 0.51, 1.26 | ||||||||

| C/C (12) | 0.74 | 0.51, 1.08 | 0.3 | 0.47 | 0.23, 0.93 | 0.031 | 0.64 | 0.29, 1.42 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.89 | 0.76, 1.04 | 0.15 | 0.69 | 0.53, 0.91 | 0.008 | 0.8 | 0.58, 1.11 | 0.19 | |||||

| rs5945572 | Xp11 | 766 | 0.3 | 0.35 | G/G (71) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (0.3) | 1.23 | 0.17, 8.80 | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| A/A (29) | 0.89 | 0.69, 1.13 | 0.6 | 1.42 | 1.00, 2.03 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 0.73, 1.85 | 0.8 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.94 | 0.83, 1.06 | 0.3 | 1.19 | 1.00, 1.42 | 0.051 | 1.08 | 0.86, 1.36 | 0.5 | |||||

| rs721048 | 2p15 | 772 | 0.15 | 0.19 | G/G (71) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (26) | 1.12 | 0.88, 1.42 | 1.02 | 0.70, 1.49 | 1.07 | 0.67, 1.73 | ||||||||

| A/A (3) | 1.31 | 0.73, 2.33 | 0.5 | 0.99 | 0.37, 2.71 | 1 | 2.28 | 0.91, 5.72 | 0.2 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.13 | 0.93, 1.37 | 0.2 | 1.01 | 0.74, 1.39 | 0.9 | 1.26 | 0.86, 1.83 | 0.2 | |||||

| rs7501939 | 17q12 | 759 | 0.41 | 0.62 | C/C (35) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| C/T (48) | 0.94 | 0.74, 1.19 | 1.12 | 0.77, 1.63 | 0.87 | 0.55, 1.38 | ||||||||

| T/T (17) | 0.97 | 0.71, 1.32 | 0.9 | 1.14 | 0.68, 1.90 | 0.8 | 0.84 | 0.43, 1.63 | 0.8 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.98 | 0.84, 1.14 | 0.8 | 1.08 | 0.84, 1.38 | 0.5 | 0.91 | 0.66, 1.24 | 0.5 | |||||

| rs7920517 | 10 | 758 | 0.43 | 0.53 | G/G (34) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (47) | 1.26 | 0.98, 1.61 | 0.94 | 0.64, 1.38 | 0.92 | 0.57, 1.48 | ||||||||

| A/A (19) | 1.42 | 1.05, 1.92 | 0.056 | 1.01 | 0.64, 1.61 | 0.9 | 0.83 | 0.45, 1.53 | 0.8 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.2 | 1.03, 1.39 | 0.017 | 1 | 0.79, 1.26 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.68, 1.23 | 0.5 | |||||

| rs7931342 | 11q13 | 760 | 0.29 | 0.44 | G/G (51) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| G/T (39) | 0.96 | 0.76, 1.20 | 1.55 | 1.09, 2.20 | 1.41 | 0.91, 2.20 | ||||||||

| T/T (9) | 0.95 | 0.65, 1.40 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.71, 2.37 | 0.053 | 1.06 | 0.47, 2.37 | 0.3 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.97 | 0.82, 1.14 | 0.7 | 1.26 | 0.99, 1.61 | 0.06 | 1.16 | 0.85, 1.59 | 0.3 | |||||

| rs902774 | 12 | 749 | 0.14 | 0.15 | G/G (74) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| A/G (24) | 1.05 | 0.82, 1.35 | 0.84 | 0.56, 1.25 | 1.01 | 0.62, 1.63 | ||||||||

| A/A (2) | 1.09 | 0.51, 2.31 | 0.9 | 0.62 | 0.15, 2.50 | 0.6 | 1.02 | 0.25, 4.19 | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.05 | 0.85, 1.30 | 0.7 | 0.82 | 0.58, 1.18 | 0.3 | 1.01 | 0.67, 1.53 | 1 | |||||

| rs9364554 | 6p25 | 767 | 0.21 | 0.32 | C/C (62) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (34) | 1.06 | 0.84, 1.32 | 1.11 | 0.78, 1.58 | 1.32 | 0.85, 2.05 | ||||||||

| T/T (4) | 0.74 | 0.39, 1.40 | 0.6 | 0.73 | 0.23, 2.30 | 0.7 | 0.87 | 0.21, 3.57 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.98 | 0.81, 1.19 | 0.9 | 1.03 | 0.76, 1.39 | 0.9 | 1.18 | 0.82, 1.72 | 0.4 | |||||

| rs10896449 | 11q13 | 778 | 0.3 | 0.45 | G/G (50) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| G/A (40) | 0.96 | 0.76, 1.20 | 1.52 | 1.07, 2.15 | 1.43 | 0.93, 2.22 | ||||||||

| A/A (10) | 0.89 | 0.61, 1.29 | 0.8 | 1.33 | 0.76, 2.34 | 0.062 | 1.22 | 0.59, 2.52 | 0.3 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.95 | 0.81, 1.11 | 0.5 | 1.26 | 0.99, 1.59 | 0.058 | 1.2 | 0.89, 1.62 | 0.2 | |||||

| rs109939944 | 10q11 | 772 | 0.47 | 0.44 | T/T (29) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (48) | 1.07 | 0.82, 1.38 | 1.11 | 0.75, 1.66 | 1.03 | 0.64, 1.67 | ||||||||

| C/C (23) | 1.34 | 1.00, 1.78 | 0.11 | 0.93 | 0.58, 1.48 | 0.7 | 0.78 | 0.43, 1.41 | 0.6 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.16 | 1.00, 1.34 | 0.052 | 0.97 | 0.77, 1.21 | 0.8 | 0.89 | 0.68, 1.19 | 0.4 | |||||

| rs1447295 | 8q24 | 764 | 0.08 | 0.16 | C/C (86) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| C/A (13) | 0.99 | 0.72, 1.35 | 0.82 | 0.50, 1.35 | 0.95 | 0.53, 1.71 | ||||||||

| A/A (1) | 1.07 | 0.27, 4.29 | 1 | * | * | * | * | 1 | ||||||

| Per allele | 0.99 | 0.74, 1.32 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.48, 1.25 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.51, 1.59 | 0.7 | |||||

| rs2735839 | 19q13 | 774 | 0.17 | 0.13 | G/G (70) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| G/A (26) | 1 | 0.79, 1.28 | 1.39 | 0.97, 1.98 | 1.96 | 1.28, 3.02 | ||||||||

| A/A (4) | 0.76 | 0.40, 1.43 | 0.7 | 1.11 | 0.45, 2.75 | 0.2 | 1.83 | 0.66, 5.07 | 0.007 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.95 | 0.78, 1.16 | 0.6 | 1.24 | 0.93, 1.64 | 0.14 | 1.65 | 1.18, 2.30 | 0.003 | |||||

| rs4242384 | 8q24 | 768 | 0.08 | NR | A/A (86) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| C/A (14) | 1.03 | 0.76, 1.39 | 0.78 | 0.47, 1.27 | 0.98 | 0.55, 1.74 | ||||||||

| C/C (1) | 0.61 | 0.09, 4.33 | 0.9 | * | * | 0.6 | * | * | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 1 | 0.75, 1.33 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.46, 1.22 | 0.2 | 0.94 | 0.54, 1.66 | 0.8 | |||||

| rs6465657 | 7q21 | 766 | 0.44 | 0.49 | T/T (33) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (47) | 1.11 | 0.87, 1.42 | 1.12 | 0.75, 1.67 | 0.87 | 0.53, 1.43 | ||||||||

| C/C (20) | 0.99 | 0.73, 1.35 | 0.6 | 1.82 | 1.17, 2.84 | 0.017 | 1.61 | 0.94, 2.75 | 0.052 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.01 | 0.87, 1.17 | 0.9 | 1.35 | 1.07, 1.70 | 0.011 | 1.26 | 0.94, 1.68 | 0.12 | |||||

| rs6983267 | 8q24 | 773 | 0.45 | 0.56 | G/G (32) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| G/T (47) | 1.16 | 0.90, 1.48 | 1.03 | 0.71, 1.51 | 1.59 | 0.95, 2.64 | ||||||||

| T/T (21) | 1.16 | 0.86, 1.57 | 0.5 | 1.11 | 0.70, 1.77 | 0.9 | 1.66 | 0.91, 3.03 | 0.15 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.08 | 0.94, 1.25 | 0.3 | 1.05 | 0.84, 1.32 | 0.7 | 1.29 | 0.97, 1.72 | 0.077 | |||||

| rs6983561 | 8q24 | 769 | 0.04 | NR | A/A (92) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| C/A (7) | 1.16 | 0.78, 1.72 | 1.62 | 0.96, 2.74 | 1.07 | 0.52, 2.22 | ||||||||

| C/C (0.1) | 5.21 | 0.73, 37.28 | 0.2 | * | * | 0.19 | * | * | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.23 | 0.84, 1.79 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.91, 2.49 | 0.11 | 1.03 | 0.50, 2.10 | 0.9 | |||||

| rs7000448 | 8q24 | 772 | 0.48 | NR | T/T (29) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| T/C (47) | 0.94 | 0.73, 1.20 | 1.1 | 0.74, 1.65 | 1.15 | 0.68, 1.93 | ||||||||

| C/C (24) | 0.95 | 0.71, 1.27 | 0.9 | 1.53 | 0.99, 2.39 | 0.13 | 1.78 | 1.02, 3.09 | 0.087 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.97 | 0.84, 1.13 | 0.7 | 1.24 | 0.99, 1.56 | 0.063 | 1.34 | 1.01, 1.79 | 0.042 | |||||

| rs7008482 | 8q24 | 742 | 0.36 | NR | T/T (43) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| G/T (43) | 0.78 | 0.62, 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.67, 1.37 | 1.15 | 0.73, 1.79 | ||||||||

| G/G (14) | 0.68 | 0.48, 0.98 | 0.036 | 0.65 | 0.36, 1.19 | 0.4 | 0.79 | 0.38, 1.64 | 0.6 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.81 | 0.69, 0.95 | 0.012 | 0.86 | 0.67, 1.10 | 0.2 | 0.96 | 0.71, 1.31 | 0.8 | |||||

| rs11670728 | 19 | 506 | 0.26 | 0.36 | G (56) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GA (36) | 1.1 | 0.83, 1.47 | 0.73 | 0.46, 1.16 | 0.67 | 0.38, 1.21 | ||||||||

| A (8) | 1.25 | 0.77, 2.04 | 0.6 | 0.42 | 0.15, 1.15 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.41, 2.34 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.11 | 0.90, 1.37 | 0.3 | 0.69 | 0.48, 0.99 | 0.042 | 0.86 | 0.57, 1.29 | 0.5 | |||||

| 1541int | 19 | 499 | 0.05 | NR | G (91) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GT (9) | 0.69 | 0.40, 1.19 | 1.31 | 0.63, 2.72 | 1.21 | 0.48, 3.05 | ||||||||

| T (0.4) | 21.26 | 5.02, 90.04 | <0.0005 | 17.35 | 4.11, 73.26 | <0.0005 | 0 | * | 0.9 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.89 | 0.55, 1.44 | 0.6 | 1.87 | 1.04, 3.38 | 0.037 | 1.12 | 0.46, 2.70 | 0.8 | |||||

| rs1654553 | 19 | 494 | 0.45 | 0.49 | G (32) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GA (46) | 1.13 | 0.83, 1.54 | 1.25 | 0.76, 2.06 | 1.19 | 0.65, 2.19 | ||||||||

| A (22) | 1.01 | 0.68, 1.49 | 0.7 | 1.15 | 0.62, 2.14 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.51, 2.35 | 0.9 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.02 | 0.84, 1.23 | 0.9 | 1.09 | 0.81, 1.46 | 0.6 | 1.06 | 0.74, 1.53 | 0.8 | |||||

| rs17526278 | 19 | 509 | 0.1 | 0.1 | G (83) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| AG (15) | 1.34 | 0.93, 1.91 | 1.56 | 0.89, 2.73 | 1.31 | 0.64, 2.67 | ||||||||

| A (2) | 1.05 | 0.39, 2.82 | 0.3 | 3.16 | 0.76, 13.15 | 0.1 | 3.19 | 0.43, 23.70 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.21 | 0.90, 1.61 | 0.2 | 1.63 | 1.03, 2.59 | 0.039 | 1.42 | 0.77, 2.64 | 0.3 | |||||

| rs198972 | 19 | 495 | 0.37 | 0.3 | C (42) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| CT (43) | 1.15 | 0.86, 1.53 | 0.93 | 0.59, 1.49 | 0.94 | 0.55, 1.62 | ||||||||

| T (15) | 0.74 | 0.47, 1.15 | 0.14 | 1.07 | 0.58, 1.98 | 0.9 | 0.56 | 0.21, 1.46 | 0.5 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.93 | 0.77, 1.12 | 0.4 | 1.01 | 0.75, 1.37 | 0.9 | 0.81 | 0.55, 1.20 | 0.3 | |||||

| rs198977 | 19 | 500 | 0.25 | 0.26 | C (57) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| CT (37) | 1.07 | 0.81, 1.42 | 1.08 | 0.69, 1.69 | 0.7 | 0.39, 1.24 | ||||||||

| T (6) | 0.71 | 0.35, 1.46 | 0.5 | 1.42 | 0.56, 3.57 | 0.7 | 1.15 | 0.35, 3.74 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.97 | 0.77, 1.22 | 0.8 | 1.13 | 0.79, 1.62 | 0.5 | 0.83 | 0.52, 1.33 | 0.4 | |||||

| rs198978 | 19 | 496 | 0.35 | 0.34 | G (44) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GT (43) | 1.05 | 0.79, 1.40 | 1.12 | 0.71, 1.78 | 0.87 | 0.50, 1.51 | ||||||||

| T (13) | 0.86 | 0.55, 1.34 | 0.7 | 0.92 | 0.45, 1.86 | 0.8 | 0.51 | 0.18, 1.45 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.96 | 0.79, 1.17 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.74, 1.37 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.51, 1.17 | 0.2 | |||||

| rs2271094 | 19 | 455 | 0.38 | 0.43 | A (40) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GA (45) | 0.89 | 0.65, 1.21 | 0.78 | 0.48, 1.27 | 0.95 | 0.52, 1.74 | ||||||||

| G (15) | 1.06 | 0.69, 1.62 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.32, 1.51 | 0.5 | 1.05 | 0.44, 2.49 | 1 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.99 | 0.81, 1.22 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.58, 1.16 | 0.3 | 1.01 | 0.67, 1.52 | 1 | |||||

| rs3760728 | 19 | 505 | 0.25 | 0.42 | C (56) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GC (36) | 1.14 | 0.86, 1.52 | 0.79 | 0.50, 1.23 | 0.73 | 0.41, 1.29 | ||||||||

| G (7) | 1.4 | 0.86, 2.28 | 0.3 | 0.44 | 0.16, 1.21 | 0.2 | 1.03 | 0.43, 2.46 | 0.5 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.17 | 0.95, 1.44 | 0.15 | 0.73 | 0.51, 1.03 | 0.075 | 0.89 | 0.59, 1.35 | 0.6 | |||||

| rs6998 | 19 | 488 | 0.22 | 0.29 | G (63) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GA (31) | 1.13 | 0.84, 1.52 | 0.64 | 0.39, 1.02 | 0.62 | 0.34, 1.13 | ||||||||

| A (6) | 1.01 | 0.57, 1.79 | 0.7 | 0.35 | 0.11, 1.12 | 0.051 | 0.77 | 0.27, 2.15 | 0.3 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.06 | 0.85, 1.32 | 0.6 | 0.62 | 0.42, 0.91 | 0.014 | 0.74 | 0.48, 1.16 | 0.2 | |||||

| rs61752561 | 19 | 440 | 0.03 | 0.04 | G (95) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GA (4) | 0.71 | 0.32, 1.61 | 1.85 | 0.75, 4.60 | 4.49 | 2.00, 10.07 | ||||||||

| A (1) | 0.77 | 0.11, 5.52 | 0.7 | 5.79 | 1.41, 23.79 | 0.025 | 6.49 | 1.56, 27.05 | <0.0005 | |||||

| Per allele | 0.77 | 0.40, 1.47 | 0.4 | 2.16 | 1.20, 3.90 | 0.011 | 3.1 | 1.84, 5.20 | <0.0005 | |||||

| rs10993994swe | 19 | 505 | 0.48 | 0.44 | T (30) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| TC (45) | 1.1 0.79 | 1.52 | 1.16 | 0.70, 1.91 | 0.97 | 0.54, 1.77 | ||||||||

| C (25) | 1.21 0.84 | 1.74 | 0.6 | 0.81 | 0.44, 1.48 | 0.4 | 0.62 | 0.29, 1.32 | 0.4 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.1 0.92 | 1.32 | 0.3 | 0.91 | 0.69, 1.21 | 0.5 | 0.81 | 0.57, 1.15 | 0.2 | |||||

| rs2735839swe | 19 | 490 | 0.19 | 0.13 | G (68) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| GA (27) | 1.09 0.81 | 1.48 | 1.78 | 1.13, 2.82 | 2.11 | 1.21, 3.67 | ||||||||

| A (5) | 0.93 0.47 | 1.82 | 0.8 | 2.21 | 0.94, 5.22 | 0.02 | 3.1 | 1.19, 8.09 | 0.008 | |||||

| Per allele | 1.03 0.81 | 1.30 | 0.8 | 1.61 | 1.15, 2.24 | 0.005 | 1.88 | 1.27, 2.79 | 0.002 | |||||

The first p-value shown for each SNP was determined by a “2 degree of freedom test” for a global difference across genotypes; the second p-value shown was determined by a log-additive (linear trend) model

Hazard ratios were not estimated due to the low number of events and the low number of patients with genotype frequency.

Abbreviations: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; MAF, minor allele frequency; published AF, published allele frequency; HR, hazard ratio; swe, represents genotyping from second analysis performed in Malmo, Sweden; NR, not reported; Ref, reference.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier probability of freedom from biochemical recurrence common for individuals who are homozygote vs heterozygote or rare homozygote at rs10486567

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier probability of freedom from prostate cancer-specific death for individuals who are homozygote vs heterozygote or rare homozygote at rs2735839

On multivariable analysis, biopsy Gleason score was significantly associated with all 3 outcomes (all p<0.003), while PSA was not significantly associated with any of the 3 outcomes (all p> 0.3) and clinical stage was significantly associated with biochemical recurrence (p=0.01), but not clinical metastases (p=0.146) or prostate-cancer specific death (p=0.7). In relation to patients with biopsy Gleason score ≤ 6, the hazard ratio for prostate-cancer specific death for Gleason score of 7 was 2.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 4.7); and for Gleason score ≥ 8 was 3.6 (95% CI 1.8 to 7.4). For the SNPs associated with the various outcomes at p<0.05, we performed multivariable analyses controlling for age, PSA, clinical stage, and biopsy Gleason score, separately for each SNP (table 3). Trends for association were observed for 3 SNPs: between rs10486567 and biochemical recurrence (p=0.037) and clinical metastases (p=0.013); between rs6465657 and clinical metastases (p=0.050); and between rs2735839 and prostate cancer specific death (p=0.002)

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis for SNPs and prostate cancer outcomes. Each SNP is individually assessed in separate multivariable models, controlling for age at prostate cancer diagnosis, PSA at diagnosis, clinical stage, and biopsy Gleason grade. Shown are SNPs with univariate associations at p<0.05 by the “2 degree of freedom test”.

| SNP | Number of patients |

Biochemical Recurrence N=351 |

Clinical Metastases N=146 |

Prostate Cancer Specific Death N=91 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| rs10486567 | 635 | 1.29 | 1.00, 1.65 | 0.046 | 1.42 | 0.96, 2.10 | 0.083 | 1.1 | 0.66, 1.82 | 0.7 |

| rs4962416 | 628 | 1.08 | 0.84, 1.39 | 0.5 | 0.87 | 0.58, 1.29 | 0.5 | 0.85 | 0.50, 1.45 | 0.6 |

| rs7920517 | 631 | 1.53 | 1.17, 2.01 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 0.73, 1.68 | 0.6 | 1.06 | 0.61, 1.84 | 0.8 |

| rs7931342 | 632 | 1.03 | 0.80, 1.32 | 0.8 | 2.01 | 1.35, 3.00 | 0.0006 | 1.81 | 1.07, 3.05 | 0.027 |

| rs10896449 | 649 | 1.01 | 0.79, 1.28 | 1 | 1.88 | 1.28, 2.77 | 0.001 | 1.83 | 1.10, 3.04 | 0.021 |

| rs2735839 | 643 | 0.88 | 0.67, 1.17 | 0.4 | 1.26 | 0.84, 1.87 | 0.3 | 2.22 | 1.35, 3.66 | 0.002 |

| rs7008482 | 617 | 0.85 | 0.66, 1.09 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.59, 1.28 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.60, 1.65 | 1 |

The first p-value shown for each SNP was determined by a “2 degree of freedom test” for a global difference across genotypes; the second p-value shown was determined by a log-additive (linear trend) model

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to verify that our results were not affected by left truncation or the competing risk of death from other causes. None of the results from the sensitivity analyses would have led to different conclusions as obtained from the main analyses (data not shown). For example, in both sensitivity analyses we found rs10486567 to be associated with biochemical recurrence (left truncation analysis: hazard ratio 1.3 for heterozygote and 1.9 for rare homozygote versus common homozygote, p=0.001; competing risk analysis: hazard ratio 1.4 for heterozygote and 1.9 for rare homozygote versus common homozygote, p=0.0004) and rs2735839 to be associated with prostate cancer-specific survival (left truncation analysis: hazard ratio 2.0 for heterozygote and 1.6 for rare homozygote versus common homozygote, p=0.009; competing risk analysis: hazard ratio 2.0 for heterozygote and 1.5 for rare homozygote versus common homozygote, p=0.008).

Results of the secondary independent analysis were concordant with the primary genotyping study for the two overlapping SNPs. We confirmed the association with rs2735839. Additionally we identified associations between rs61752561, an Asp-Asn SNP in KLK3,[28] and prostate cancer-specific mortality on both univariate (HR = 4.82 for having any rare allele versus common homozygote, 95%CI: 2.33, 9.98, p<0.0005) and multivariable analyses (HR=5.1, 95%CI: 2.7, 11.8, p<0.0005), and between 1541int and biochemical recurrence (p<0.0005) and castration resistant metastasis (p<0.0005).

Conclusions

We identified associations between known susceptibility loci for prostate cancer and biochemical recurrence, castration-resistant progression of disease and prostate cancer-specific death. Five of the 29 SNPs examined in the initial analysis showed evidence of an association with biochemical recurrence, clinical metastases, or prostate cancer specific death, and three additional associations were identified in the high resolution SNP panel. Due to the small size of this study we did not formerly correct for multiple testing and our results are therefore intended to be hypothesis generating; however, even after accounting for multiple testing in the primary analysis one of the SNPs, rs10486567 located in the 7JAZF1, was significantly associated with biochemical recurrence.

Prostate cancer incidence continues to increase, but the death rate remains close to 3–4%,[1] suggesting that indolent disease is being increasingly diagnosed and treated. Biomarkers that compliment the clinical indicators currently available, and reliably predict aggressive disease are urgently needed. If they are associated with grade of disease, it is possible that susceptibility loci may also correlate with disease prognosis. Such appears to be the case for BRCA mutations, which are associated with increased risk for a higher grade of prostate cancer and independently with worse clinical outcome.17,[19]

Germline variation has been associated with risk of prostate cancer and it has recently been appreciated that germline variation may also be used to predict outcome after diagnosis. Initial studies investigating prognostic endpoints were disappointing, and efforts to associate susceptible loci with Gleason score and survival were unsuccessful.[16, 21–23]. However, others identified associations between rs2735839 in KLK3 (P = 8.4 × 10−7, rs10993994 in MSMB (P = 0.046),[29] rs2710646 at 2p15 and rs4054823 at 17p12 and more aggressive prostate cancer defined by histological grade and clinical stage.[7, 30] One study reported an association between rs7920517 and rs10993994 and PSA recurrence after prostatectomy.[31] The current report is thus among the first to characterize susceptibility loci identified by genome wide scans as potential prognostic indicators, and specifically to investigate clinically meaningful endpoints such as castration resistant metastases and prostate cancer-specific mortality.

No biomarker has yet been identified that adds a clinically significant increment to the prognostic power of currently used clinical indicators, such as PSA, clinical stage and Gleason score. Levels of serum markers such as human kallikrein-related peptidase 2 (hK2) and soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor have been associated with clinical outcome.[32–33], and appear to improve the predictive accuracy of pre-operative nomograms for biochemical recurrence,[34–35] but there is no evidence that any analyte improves significantly on the deficiencies of PSA testing. The somatic rearrangement TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion that is identified in approximately 50% of PSA-screened primary prostate cancers and was initially associated with tumor progression has subsequently been associated with both favorable and worse outcome associations.[36–38] The clinical utility of this marker is therefore currently uncertain. The inverse relationship between circulating tumor cell (CTC) number and outcome,[39] in addition to the potential of CTCs to provide somatic DNA for analysis,[40] supports their candidacy as a potential biomarker. Prospective tests of CTCs are still pending. Germline genetic variation provides attractive biomarker candidates which can be identified at time of blood draw, do not change over time (i.e. are constitutional), and when using a dominant model or recessive model are dichotomous (i.e. do not require adjustment or normalization).

The strongest association with a genetic variant identified here involved rs10486567 located in 7JAZF1. In both the univariate and the multivariable analyses this SNP predicted early biochemical recurrence for heterozygotes or rare homozygotes. This association remained significant after Bonferroni correction. Thomas et al identified no association between this SNP and prostate cancer risk in their first genome wide scan (p=0.04), but reported a protective effect in a second larger analysis [OR of heterozygotes vs controls for non-aggressive disease 0.74 (0.66–0.83); OR of heterozygotes vs controls for aggressive disease 0.89 (0.80–0.98)], and the signal appeared to be more strongly associated with aggressive disease, defined as Gleason score > 7 or disease stage 3/4[12]. A common translocation identified in endometrial stromal tumors brings together JAZF1 and the JJAZ1 gene;[41] expression of the protein product protects cells from apoptosis caused by hypoxia. JAZF1 appears to act as a transcriptional repressor of NR2C2, a nuclear orphan receptor that is highly expressed in prostate tissue and that reportedly interacts with the androgen receptor[12]. This gene has not been functionally implicated in prostate cancer to date, and while the possibility of a false negative association exists, this result highlights the potential for germline association studies to identify molecular pathways that may be important in disease development.

We identified an association between rs2735839, located in the KLK2-KLK3 intergenic region, and prostate cancer-specific mortality in both univariate (p=0.007), and multivariable analyses (0.002). This SNP has been associated with prostate cancer predisposition, but again with a protective effect for the heterozygous and rare homozygous alleles (per allele odds ratio = 0.83, P = 2 × 1018).[8] The protective allele has also been associated with poorly differentiated, high stage prostate cancer. However, it has been reported that this association is confounded by a PSA bias.[8, 21, 42] Individuals with the susceptibility allele may be biopsied earlier due to a raised PSA but have lower Gleason scores. Individuals with this PSA-associated allele may therefore have increased risk of being diagnosed because they have a higher PSA, and the SNP may not be etiologically involved in prostate cancer development. However, an association between a single PSA test and subsequent prostate cancer progression has been repeatedly reported supporting an etiological role for this locus,[3, 43–45] and the relationship between this SNP and PSA values at later stages of disease would be worthy of investigation. Furthermore, the association with prostate cancer-specific death remained (p=0.002) in a multivariable model that included PSA and stage.[46] Finally, the strong association of an additional polymorphism in Asp-Asn KLK3 (rs61752561) which is in linkage disequilibrium with rs2735839[26] with prostate cancer-specific mortality in our second analysis strengthens the hypothesis that this locus is important in influencing outcome.

The association between rs2735839 and rs61752561 and prostate cancer-specific mortality may be explained by an interaction between KLK genes and the androgen receptor. ADT is the mainstay of treatment for recurrent prostate cancer, however response duration is limited and prostate cancer evolves to regain the ability to grow despite low levels of circulating androgens.[47] Upon the development of hormone-refractory progression of disease most tumors maintain dependence on the androgen receptor despite low levels of circulating androgens, and novel therapeutic strategies targeting androgen receptor signaling in this setting have recently been developed. Functional data suggesting that a polymorphism in the androgen response element, located in the promoter of KLK3 gene, confers greater androgen responsiveness and a greater affinity for the androgen receptor provides an example of how mutations in KLK genes may correlate with the development of hormone refractory disease[46].

We recently reported that BRCA mutation was associated with worse outcome in Ashkenazi men with prostate cancer by predicting earlier biochemical recurrence, hormone refractory progression of disease and death due to prostate cancer.[48] The different associations between clinical endpoints and SNPs in this study may be related to their differential function. For example, different loci may contribute to different stages of disease progression. Rs7008482 was associated with biochemical recurrence in the univariate analysis but not in the multivariable analysis that included PSA. While a rise in PSA in both hormone-sensitive and castration-resistant prostate cancer predicts overall survival,[49] this study was limited to PSA determination at time of diagnosis, and PSA at a later time point may more accurately predict survival. Furthermore, our choice of definition for biochemical recurrence may also have obscured the associations with this end-point.[50] Patients in this study received different primary therapies for their prostate cancer and consequently different definitions were used to define biochemical recurrence. As a result, biochemical recurrence may be the least robust of the clinical endpoints used.

The results reported here are limited by the small number of patients in genetically defined subsets; larger studies are required to verify these findings. Population heterogeneity may induce false positive findings in genomic association studies; the limitation of the current analysis to those of Ashkenazi heritage was intended to address this potential concern. It is also possible that associations reported are unique to the genetic isolate we have investigated, but thus far, “founder” alleles for cancer risk have been representative of genetic variants in the general population. While the major finding of an association of rs10486567 and biochemical recurrence survives a Bonferonni correction, the significance of the point estimates of the other associations is limited by small sample size and multiple comparisons. For these reasons, the current findings are hypothesis generating and requiring of prospective validation. Investigation of SNP associations in a large cohort where clinical data is prospectively collected is needed. If confirmed, these and other findings which emerge could be incorporated into existing nomograms to allow more accurate risk predications than those based on PSA and common clinical markers. Investigation of the genetic candidates implicated by reported SNP associations with clinical outcome may also improve our understanding of the pathways of progression of prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Clinical Relevance.

Nomograms incorporating clinical variables are commonly used to guide the management of early stage prostate cancer, but their prognostic capability is limited. Prostate cancer specific mortality is the most robust prostate cancer endpoint but is particularly difficult to predict using clinical variables alone, and novel biomarkers are urgently needed. Common variants in germline DNA have been associated with increased prostate cancer risk but efforts to identify germline predictors of outcome have been disappointing. We investigated germline predictors of progression through the prostate cancer clinical states model in a homogenous group of patients with early stage prostate cancer, and report associations between susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms and certain clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Goldstein Research Initiative of the Program in Prevention, Control and Population Research at MSKCC, the Robert and Kate Niehaus Clinical Cancer Genetics Research Program, the Koodish Fellowship, David H. Koch through the Prostate Cancer Foundation, The Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers, the Swedish Cancer Society [no. 08-0345], the Swedish Research Council [Medicine no. 20095], and MTBH [no. 2006-7600]. We are grateful to Mia Gaudet, Ph.D. and Dean Bajorin, M.D. for discussion of study design.

References

- 1.Ries LA, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2000;88(10):2398–2424. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2398::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson IM, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(22):2239–2246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilja H, et al. Long-term prediction of prostate cancer up to 25 years before diagnosis of prostate cancer using prostate kallikreins measured at age 44 to 50 years. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(4):431–436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shariat SF, et al. An updated catalog of prostate cancer predictive tools. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3075–3099. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walz J, et al. Clinicians are poor raters of life-expectancy before radical prostatectomy or definitive radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100(6):1254–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haiman CA, et al. Multiple regions within 8q24 independently affect risk for prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):638–644. doi: 10.1038/ng2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudmundsson J, et al. Common sequence variants on 2p15 and Xp11.22 confer susceptibility to prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40(3):281–283. doi: 10.1038/ng.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eeles RA, et al. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40(3):316–321. doi: 10.1038/ng.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haiman CA, et al. A promoter polymorphism in the CASP8 gene is not associated with cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2008;40(3):259–260. doi: 10.1038/ng0308-259. author reply 260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gudmundsson J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):631–637. doi: 10.1038/ng1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeager M, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):645–649. doi: 10.1038/ng2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas G, et al. Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40(3):310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng I, et al. 8q24 and prostate cancer: association with advanced disease and meta-analysis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(4):496–505. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin AM, et al. Chromosome 17q12 variants contribute to risk of early-onset prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(16):6492–6495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng SL, et al. Association between two unlinked loci at 8q24 and prostate cancer risk among European Americans. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(20):1525–1533. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald LM, et al. Analysis of recently identified prostate cancer susceptibility loci in a population-based study: associations with family history and clinical features. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):3231–3237. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kote-Jarai Z, et al. Multiple novel prostate cancer predisposition loci confirmed by an international study: the PRACTICAL Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(8):2052–2061. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gayther SA, et al. The frequency of germ-line mutations in the breast cancer predisposition genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 in familial prostate cancer. The Cancer Research Campaign/British Prostate Group United Kingdom Familial Prostate Cancer Study Collaborators. Cancer Res. 2000;60(16):4513–4518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchhoff T, et al. BRCA mutations and risk of prostate cancer in Ashkenazi Jews. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(9):2918–2921. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher DJ PP, Kirchhoff T, et al. Germline BRCA mutations denote a clinicopathologic subset of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2871. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiklund FE, et al. Established prostate cancer susceptibility variants are not associated with disease outcome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(5):1659–1662. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penney KL, et al. Evaluation of 8q24 and 17q risk loci and prostate cancer mortality. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):3223–3230. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salinas CA, et al. Clinical utility of five genetic variants for predicting prostate cancer risk and mortality. Prostate. 2009;69(4):363–372. doi: 10.1002/pros.20887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephenson AJ, et al. Defining biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: a proposal for a standardized definition. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(24):3973–3978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen ME, et al. Is it possible to compare PSA recurrence-free survival after surgery and radiotherapy using revised ASTRO criterion--"nadir + 2"? Urology. 2008;72(2):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.10.053. discussion 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein RJ HC, Cronin AM, et al. Blood biomarker levels to aid discovery of cancer-related single nucleotide polymorphisms: kallikreins and prostate cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0206. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine JP GR. A proportional hazards model for the sub distribution of a competing risk. JASA. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mononen N, et al. Profiling genetic variation along the androgen biosynthesis and metabolism pathways implicates several single nucleotide polymorphisms and their combinations as prostate cancer risk factors. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):743–747. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kader AK, et al. Individual and cumulative effect of prostate cancer risk-associated variants on clinicopathologic variables in 5,895 prostate cancer patients. Prostate. 2009;69(11):1195–1205. doi: 10.1002/pros.20970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J, et al. Inherited genetic variant predisposes to aggressive but not indolent prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(5):2136–2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914061107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang SP, et al. Prognostic significance of prostate cancer susceptibility variants on prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(11):3068–3074. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lintula S, et al. Relative concentrations of hK2/PSA mRNA in benign and malignant prostatic tissue. Prostate. 2005;63(4):324–329. doi: 10.1002/pros.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steuber T, et al. Comparison of free and total forms of serum human kallikrein 2 and prostate-specific antigen for prediction of locally advanced and recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 2007;53(2):233–240. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.074963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kattan MW, et al. The addition of interleukin-6 soluble receptor and transforming growth factor beta1 improves a preoperative nomogram for predicting biochemical progression in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3573–3579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svatek RS, et al. Pre-treatment biomarker levels improve the accuracy of post-prostatectomy nomogram for prediction of biochemical recurrence. Prostate. 2009;69(8):886–894. doi: 10.1002/pros.20938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winnes M, et al. Molecular genetic analyses of the TMPRSS2-ERG and TMPRSS2-ETV1 gene fusions in 50 cases of prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;17(5):1033–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nam RK, et al. Expression of the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene predicts cancer recurrence after surgery for localised prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(12):1690–1695. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gopalan A, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion is not associated with outcome in patients treated by prostatectomy. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1400–1406. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danila DC, et al. Circulating tumor cell number and prognosis in progressive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):7053–7058. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Bono JS, et al. Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(19):6302–6309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koontz JI, et al. Frequent fusion of the JAZF1 and JJAZ1 genes in endometrial stromal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(11):6348–6353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101132598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahn J, et al. Variation in KLK genes, prostate-specific antigen and risk of prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1032–1034. doi: 10.1038/ng0908-1032. author reply 1035-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroder FH, et al. 4-year prostate specific antigen progression and diagnosis of prostate cancer in the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer, section Rotterdam. J Urol. 2005;174(2):489–494. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165568.76908.5c. discussion 493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carter HB, et al. Detection of life-threatening prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen velocity during a window of curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(21):1521–1527. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aus G, et al. Individualized screening interval for prostate cancer based on prostate-specific antigen level: results of a prospective, randomized, population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(16):1857–1861. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai J, et al. PSA/KLK3 AREI promoter polymorphism alters androgen receptor binding and is associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(5):1032–1039. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smaletz O, Scher HI. Outcome predictions for patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Semin Urol Oncol. 2002;20(2):155–163. doi: 10.1053/suro.2002.32938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gallagher DJPP, Kirchhoff T, et al. Correlation of BRCA2 mutation and prostate cancer phenotype. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol Genitouarinary Symposium (abstract #20) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hussain M, et al. Prostate-specific antigen progression predicts overall survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer: data from Southwest Oncology Group Trials 9346 (Intergroup Study 0162) and 9916. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2450–2456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephenson AJ, et al. Defining biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: a proposal for a standardized definition. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3973–3978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.