Abstract

Design and construction of biochemical pathways has increased the complexity of biosynthetically-produced compounds when compared to single enzyme biocatalysis. However, the coordination of multiple enzymes can introduce a complicated set of obstacles to overcome in order to achieve a high titer and yield of the desired compound. Metabolic engineering has made great strides in developing tools to optimize the flux through a target pathway, but the inherent characteristics of a particular enzyme within the pathway can still limit the productivity. Thus, judicious protein design is critical for metabolic and pathway engineering. This review will describe various strategies and examples of applying protein design to pathway engineering to optimize the flux through the pathway. The proteins can be engineered for altered substrate specificity/selectivity, increased catalytic activity, reduced mass transfer limitations through specific protein localization, and reduced substrate/product inhibition. Protein engineering can also be expanded to design biosensors to enable high through-put screening and to customize cell signaling networks. These strategies have successfully engineered pathways for significantly increased productivity of the desired product or in the production of novel compounds.

Keywords: Protein engineering, directed evolution, rational design, pathway engineering, synthetic biology, biosensors

1. Introduction

Engineering highly efficient enzymatic pathways for industrial-scale production of fuels and chemicals remains an overwhelming challenge in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology (Keasling, 2010; Khosla and Keasling, 2003). The poor performance of pathways may result from unbalanced protein expression and activity levels, low availability of precursors and cofactors, toxic intermediates and end-products, and overall metabolic burden (Du et al., 2011). Several transcriptional engineering strategies have been developed to address these inefficiencies, such as varying plasmid copy number (Ajikumar et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2000), promoter engineering (Alper et al., 2005; Du et al., 2012), intergenic region engineering (Pfleger et al., 2006; Smolke et al., 2000), ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering (Salis et al., 2009), and codon optimization (Redding-Johanson et al., 2011). However, these strategies cannot overcome the limitations associated with enzymes themselves. Innate enzyme characteristics can produce bottlenecks, generate unwanted by-products, and limit high titers. To overcome these deficiencies, shrewd protein design can be indispensable when engineering an optimal pathway. In designing efficient proteins, one may choose to engineer activity, substrate specificity/selectivity, solubility, and stability. Additionally, substrate/product inhibition and protein localization can be considered in the design process to optimize the pathway. Protein function can also be designed as a major messenger of cellular signals, in detection of cell-cell communication and environmental inputs. Thus, protein engineering is a powerful tool in developing biosensors for high-throughput methods in metabolic engineering and designing customized cellular signaling networks.

This review will first briefly describe experimental and computational tools for protein engineering and design. Next, a few examples will be highlighted to illustrate how these tools can be used to improve the efficiency of pathways for the production of fuels and chemicals. Though there are innumerable examples of protein engineering to improve the performance of enzyme biocatalysts (Bornscheuer et al., 2012; Cobb et al., 2012; Rubin-Pitel and Zhao, 2006; Wang et al., 2012), this review will focus on engineering enzymes within a pathway, wherein the engineered enzyme is coupled with the entire pathway for an increased flux, titer, and productivity of the final product. Protein design for biosensor development and signaling pathway engineering will also be discussed, as systems can be engineered to yield novel output responses or react to novel inputs.

2. Tools for Protein Engineering

2.1. Directed Evolution

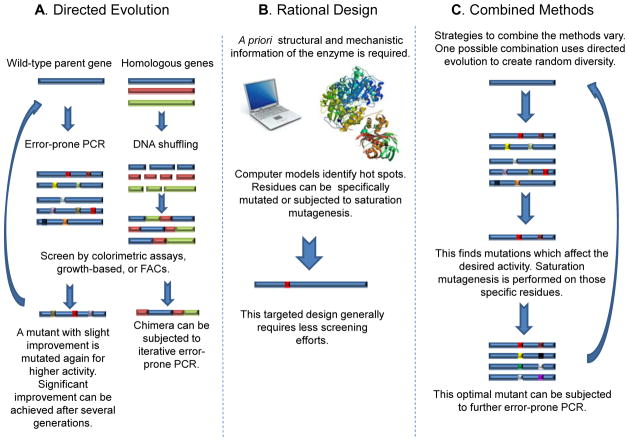

Directed evolution has become one of the most powerful tools in protein engineering. The process mimics Darwinian evolution in a test tube and involves iterative rounds of creating genetic diversity followed by selection or screening (Cobb et al., 2012; Rubin-Pitel, 2006; Wang et al., 2012) (Fig. 1A). The most common methods to generate genetic diversity include error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, chemical mutagenesis, and use of a mutator strain. To identify improved mutants from this genetic diversity, a myriad of screening/selection methods have been developed such as colorimetric assays, colony size-based growth assays, and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). A major advantage of directed evolution is that no prior knowledge of the enzyme structure or mechanism is required to improve enzymatic properties. Another advantage is the ability to mutate the entire enzyme, thus identifying residues distant to the active site that could affect activity through allosteric interactions. However, a major disadvantage of random mutagenesis-based directed evolution is the large library size; this limits the exploration of the full sequence diversity, even with the most powerful screening or selection method. Additionally, it can be difficult and time consuming to develop a high-throughput screening/selection method for a target enzyme property (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A schematic of the main protein engineering strategies consisting of directed evolution, rational design, and a combined approach. (A) Directed evolution involves the iterative rounds of genetic diversity, being screened/selected for higher activity. The genetic diversity can be introduced through either error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling. The graphs show possible increased activity over generations. (B) Rational Design identifies residues which are expected to increase the desired activity through a priori sequence or structure knowledge. The graph shows possible increased activity over a generation. (C) Though the methodology to combine these strategies can vary, one example of the conjoined method is using directed evolution to identify hotspots, and then rational design to target residues proximal to those hot-spots. The graph shows possible increased activity over generations.

2.2. Rational Design

Rational design is a knowledge-driven process which uses a priori information about the enzyme such as its structure or sequence. This knowledge is used to make specific, targeted amino acid mutations which are predicted to affect enzymatic properties vital for the desired reaction (Fig. 1B). This strategy can be valued more than directed evolution because it limits the onerous task of screening the large libraries of random mutagenesis-based directed evolution. In a sequence-based approach, researchers pursue systematic comparisons of homologous protein sequences to identify possible residues that could alter protein activity. When the three-dimensional crystal structure of the target enzyme or a homologous enzyme is available, a more direct structure-function relationship study of residues within the active site can be investigated. Through this visualization, the active site structure can be redesigned, allowing for modified chemistry to occur. Though there are many options for modifications, one example is to mutate large residues to smaller, hydrophobic residues, thus enlarging the active site which allows a larger substrate to bind. Various computational tools have been developed to compare the homologous sequences and structural databases to create a mutability map for a target protein (Damborsky and Brezovsky, 2009; Pavelka et al., 2009; Pleiss, 2011) (Fig. 1B).

Rational design is not only used to modify existing enzymes, it can also create new ones. Statistical methods linking structure and function relationships are becoming more successful for de novo protein design. A detailed understanding of the desired catalytic mechanism and its associated transition states and reaction intermediates is typically required for this method. An idealized active site is created by positioning protein functional groups to provide the lowest free energy barrier transition state between the substrates and the product (Rothlisberger et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2010). Siegel and coworkers developed a de novo enzyme which could catalyze the Diels-Alder reaction. In this design, the most dominant interaction of the transition state is interaction of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the diene with the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the dienophile. Thus, a narrow energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO was important for the design. Quantum mechanical calculations predicted that with the precise positioning of a hydrogen bond acceptor to interact with the carbamate NH of the diene and a hydrogen bond donor to interact with the carbonyl of the dienophile, the hydrogen bonds would stabilize the transition state by 4.7 kcal mol−1. This was the basic scaffold of the active site in the protein design. Furthermore, the Rosetta methodology was used to determine the final protein functional groups needed to complete the active site. This method was able to successfully design an active site which could accomplish the Diels-Alder reaction, but further rational design and site saturated mutagenesis was required to improve the activity (Siegel et al., 2010). Though not applied to a complete pathway yet, the de novo protein design is too significant to ignore when constructing a heterologous pathway.

2.3. Combination of Rational Design and Directed Evolution

Distinctions between rational design and directed evolution are becoming less clear, as researchers commonly combine these techniques (Fig. 1C). Though strategies to conjoin the methods vary, one strategy involves a two-step process of directed evolution to identify hotspots and apply rational design on those regions, or vice versa if used in de novo protein design. This was shown by Rothlisberger and coworkers in their de novo protein design, whereby the quantum mechanical calculations and rational design ensured that the key catalytic residues were positioned correctly but directed evolution was used to improve the enzyme, correcting the design parameters which could not be calculated (Rothlisberger et al., 2008).

Another strategy to combine these techniques is semi-rational design, the targeting of specific residues for saturation mutagenesis or mutagenizing a specific domain that is suspected to have critical function. Semi-rational design is powerful because it can reduce the library size to be screened and can augment the success rate of identifying positive hits (Quin and Schmidt-Dannert, 2011). These intelligent libraries rely on the ability to identify key beneficial mutations through critical structure-function relationships and knowledge of mutational effects on protein folding and activity. This design process harnesses the power of directed evolution but reduces the onerous task of screening. Techniques to develop these smart libraries have been diverse and efficient (Cobb et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012).

3. Engineering enzyme specificity or selectivity to improve pathway performance

Both rational design and directed evolution have successfully been used to engineer enzyme specificity or selectivity to improve pathway performance. Often, the promiscuity of enzymes tends to correlate with low catalytic activity and undesirable side-reactions. This results in an inefficient pathway with build-up of intermediates and by-products, which can be toxic to the cell. By redesigning proteins for increased specificity or selectivity toward the desired substrate, fewer by-products are formed. This strategy has proven to be one of the most successful strategies to optimize a pathway through protein design.

Eliminating side reactions through protein engineering was proven useful in the production of specialty chemical triacetic acid lactone (TAL) (Zha et al., 2004). The fatty acid synthase (FAS) is a bifunctional enzyme, but was rationally designed through sequence homology and structure-function relationships to inactivate the keto reductase domain. This eliminated the enzyme’s ability to utilize NADPH, abolishing the enzyme function to produce palmitic acid. As a result, the carbon flux was shifted exclusively to the desired product TAL. Another example did not completely eliminate secondary activity, but increased selectivity towards the desired reaction. Nair and Zhao engineered a xylose reductase with increased selectivity for D-xylose over L-arabinose (Nair and Zhao, 2008). Screening the error-prone PCR library revealed mutations clustering around the (β/α)8-barrel, which led to speculation that this region was involved in substrate recognition. Targeting this secondary structure, the site-saturation mutagenesis led to a final mutant with an increased selectivity from 2.4- to 16.5- fold preference for D-xylose. Further engineering for selectivity was shown to actually decrease overall catalytic activity, thus a trade-off in efficiencies was noted. Once re-introduced into the pathway and combined with other metabolic engineering strategies, all side reactions were effectively eliminated with no by-product formations from a mixture of substrates (Nair and Zhao, 2010).

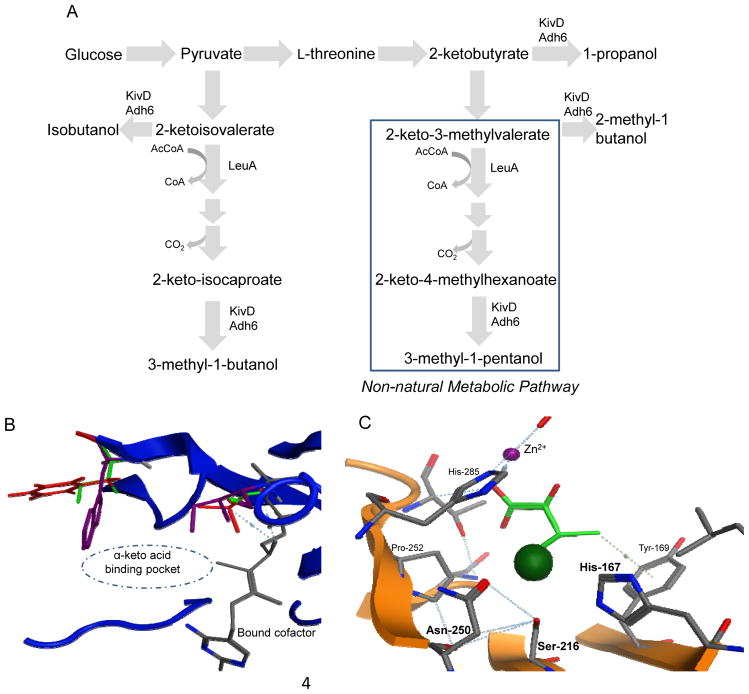

Zhang and coworkers (Zhang et al., 2008) engineered a promiscuous 2-keto-isovalerate decarboxylase (KivD) for preferred substrate specificity towards a non-natural substrate. This expanded the E. coli metabolism to produce unnatural C5 to C8 alcohols, which could be used for biofuels (Fig. 2A). The KivD specificity constant kcat/Km was engineered through rational design to a 40-fold higher preference for (S)-2-keto-4-methylhexanoate than its cognate substrate, 2-ketoisovalerate, a 10-fold increase over the wild-type specificity (Fig. 2B). The α-keto acid binding pocket was enlarged by mutating proximal residues to smaller hydrophobic amino acids, eliminating large bulky residues within the pocket. In this same report, 2-isopropylmalate synthase (LeuA) was rationally designed for increased activity for (S)-2-keto-3-methylvalerate. The crystal structure suggested the additional methanol group of the (S)-2-keto-3-methylvalerate would cause steric conflict with surrounding residues. This could be relieved by mutating those proximal residues to smaller and less bulky functional groups. The mutation S139G was identified with a seven-fold increase in kcat for (S)-2-keto-3-methylvalerate (Fig. 2C). The combination of the mutated KivD and LeuA produced several non-natural alcohols, which were not observed in the wild-type pathway.

Figure 2.

Design and establishment of the non-natural metabolic pathway to produce C5 to C8 alcohols. (A) The metabolic pathways for C5 to C8 alcohol production. The KivD is coupled with the Adh6, converting 2-keto acids to alcohols. To establish the non-natural metabolic pathway, the promiscuous KivD was engineered for increased specificity for 2-keto-4-methylhexanoate. The LeuA substrate specificity was engineered towards 2-keto-3-methylvalerate. (B) The binding pocket of KivD based on the homology model, showing the mutated residues for the best mutant V461A/F381L. The purple residues are from ZmPDC, a previously characterized crystal structure, the red residues are from wild-type KivD residues, and the green residues are from the mutated KivD. The purple residue is large and bulky, taking up significant space in the binding pocket, not allowing a large substrate to enter. The green residues illustrate the smaller hydrophobic residues, which create more space in the binding pocket and allow the enzyme to accept substrates larger than its cognate substrate. (C) Binding pocket of Mycobacterium tuberculosis LeuA bound with 2-ketoisovalerate (green). The substrate of interest (S)-2-keto-3-methylvalerate has one more methyl group, depicted by the dark green sphere. It was predicted that His-167, Ser-216, and Asn-250 would cause steric hindrance with the methyl group. A multiple sequence alignment identified the corresponding residues in E. coli LeuA and mutagenesis was applied to those residues.

The final products of the short chain trans-prenyl diphosphates family vary in chain length from C15 to C25, though they have similar tertiary structures. To better understand the mechanisms of the product chain length, a farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15) synthase (IspA) was engineered (Lee et al., 2005). The mutants identified through error-prone PCR exhibited altered chain length elongation mechanisms. Many of the mutations were found near the conserved first aspartate rich motif (FARM), known for its role during chain elongation. However, a previously unknown chain elongation mechanism was identified, through a mutation discovered on the helix adjacent to the FARM within the substrate-binding pocket. This is a major advantage of directed evolution over rational design: unknown structure-function relationships can be discovered. Other targets of protein design involving varying product chain length include polyketide synthases (Evans et al., 2011; Jez et al., 2001; Jez et al., 2002; Shao et al., 2011) and the enzyme R-hydratase (PhaJ), which was engineered to control monomer chain length in polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis (Tsuge et al., 2003).

Cofactor NAD(P)+ and NAD(P)H usage can also be engineered to increase the overall efficiency of the pathway. Properly designed proteins can reduce the competition for the cofactors between cell metabolism and enzymes of the pathway. An internal cofactor regeneration strategy was incorporated into the xylose utilization pathway to reduce the imbalance between the xylose reductase (XR) and xylitol dehydrogenase (XDH) for biofuel production. In one study, the XDH enzyme was engineered for switched cofactor specificity to NADP+, which would complement the XR cofactor preference of NADPH (Krahulec et al., 2009; Matsushika et al., 2008). In another study, the XR was altered to have preference for NADH, to complement the XDH preference of NAD+, which led to a 40-fold increase in ethanol productivity over the wild-type enzyme (Runquist et al., 2010). Similarly, Bastian and coworkers engineered an NADH-dependent pathway for the anaerobic production of isobutanol (Bastian et al., 2011). Under anaerobic conditions, the only available reducing equivalent is NADH, however a key enzyme in the isobutanol pathway, the ketol-acid reductoisomerase (IlvC), is NADPH–dependent. To optimize the pathway, the cofactor usage of the IlvC was completely switched from NADPH to NADH through iterative targeted mutagenesis. The pathway, coupled with an alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) which was engineered for higher catalytic efficiency through random mutagenesis, was able to produce nearly 14 g/L of isobutanol anaerobically. The pathway with the wild-type enzymes only produced 2 g/L.

4. Engineering protein activity to improve pathway performance

Though improving the substrate/cofactor specificity or selectivity of enzymes can increase flux, there are many other ways to engineer enzymes to increase the overall performance of a pathway. One example is higher activity, which can be achieved by improving the catalytic efficiency, protein solubility, and stability. Additionally, the pathway can be optimized by increasing the activity of the transport system, either through improved transfer of extra-cellular substrates into the cell or increased export of the products.

Leonard and coworkers (Leonard et al., 2010) engineered two enzymes from the diterpenoid biosynthetic pathway, geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPPS) and levopimaradiene synthase (LPS) for levopimaradiene production. To engineer the LPS, a homology model structure was used to select fifteen residues constituting the binding pocket. These residues were then mutated to specific residues based on phylogenetic analysis of functionally different LPS enzymes. The mutations which were found to yield increased levopimaradiene production were combined together. The resulting mutants were observed to produce the most levopimaradiene. To engineer the GGPS, random mutagenesis through error-prone PCR was used. The mutations were hypothesized to affect the GGPPS catalysis by improving the binding efficiency of the magnesium ions needed for substrate anchoring. The most improved mutants GGPPS (S239C/G295D) and LPS (M593I/Y700F) were cloned into the full pathway and combined with other metabolic engineering strategies. The final pathway resulted in a 2,600-fold increase in levopimaradiene production.

An interesting sequence-based rational design method was developed by Yoshikuni and coworkers (Yoshikuni et al., 2008). Over 30,000 homologous sequences of over 200 different E. coli enzymes involved in central metabolism were analyzed for the probability of mutations to each amino acid. Mutability prediction profiles were generated and it was found that Gly and Pro amino acids are less mutable, thus are more essential. It was hypothesized that an enzyme’s activity could be improved by redistribution of Gly and Pro based on the evolutionary relationship of other homologous enzymes. Proof of concept was demonstrated on two enzymes in the mevalonate pathway which were known as rate limiting: the 3-hydroxy-3methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (tHMGR) and the terpene synthase γ-humulene synthase (HUM). Multiple sequence alignments of homologous tHMGR and HUM enzymes were constructed and substitutions involving Gly and Pro were introduced according to the prediction profiles. This strategy identified a combination of tHMGR and HUM mutants that when integrated into the host had a 3-to 4-fold improved growth and nearly 1000-fold improved sesquiterpene production. It was noted that the improvement to the HUM protein was found to be from significantly improved concentration of the soluble enzyme.

Increasing the overall enzyme activity through traditional directed evolution was eloquently illustrated by Atsumi and Liao in a study focusing on 1-propanol and 1-butanol synthesis in E. coli (Atsumi and Liao, 2008). A combination of error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling through six rounds of directed evolution identified a top candidate, called CimaA3.7. The kcat/KM of CimaA3.7 for acetyl-CoA was 6.7 times greater than the wild-type enzyme at 30 °C. The enzyme activity was screened at varying temperatures and CimA3.7 showed higher activity than wild-type at all temperatures tested. Once re-inserted into the pathway, this enzyme yielded a 9.2-fold improvement in 1-propanol production and a 21.9-fold improvement in 1-butanol production.

Transporters can be the greatest limiting factor in a pathway but engineering these proteins has been an underutilized strategy for improving the pathway performance. Lack of three-dimensional crystal structure has limited the engineering of these proteins to directed evolution. Young and coworkers used directed evolution to generate mutants of xylose transporters with an increased affinity towards xylose but a lower Vmax. The yeast strain overexpressing the best xylose transporter mutant showed an improved growth rate of 70% on xylose as the sole carbon source (Young et al., 2012). Note that the trade-off between the Km and the Vmax in engineered xylose transporters was also found in cellodextrin transporter engineering (Ha et al., 2012). The mutant cellobiose transporters were found to have a higher Vmax, but a lower affinity for cellobiose. Efflux pumps can also be engineered to improve the efficiency of the pathway. Directed evolution was used to identify mutant efflux pumps which increased the host’s tolerance to antibiotics and toxins (Bokma et al., 2006; Crameri et al., 1997).

5. Engineering regulatory proteins to improve pathway performance

Besides engineering kinetic parameters of enzymes, pathway efficiency or the flux through the desired pathway may also be increased via relieving feedback regulation of the enzymes. Feedback inhibition by intermediates or final product has evolved as a major mechanism to regulate enzyme activities in natural systems. The function of this evolved mechanism is to maintain the concentration of intermediates or final products within a narrow range to prevent cytotoxicity (Jackson et al., 1974). If feedback-regulated enzymes exist in a biosynthetic pathway, they are often the bottleneck for efficient production. Thus, engineering feedback-resistant enzymes is an effective strategy to improve the overall pathway performance.

Liao and co-workers have developed a creative strategy to produce long-chain alcohols used for biofuels via 2-keto acids (Atsumi et al., 2008) and intermediates in the biosynthesis of amino acids. However, these amino acid biosynthetic pathways are known to be highly regulated by feedback inhibition (Jackson et al., 1974), which is one of the bottlenecks for efficient biofuel production. Relieving feedback inhibition in these biosynthetic pathways increased the titer of a series of alcohols significantly. For example, the introduction of the feedback-resistant aspartate kinase/homoserine dehydrogenase (ThrA), which catalyzes the first two steps in threonine production from aspartate, resulted in nearly a 4-fold increase in the titer of both 1-propanol and 1-butanol (Shen and Liao, 2008). In a follow-up study to produce 3-methyl-1-butanol, the precursor 2-ketoisocaproate was only produced at 0.2 g/L in the wild-type strain, limiting high-level production of the desired product. However, by replacing the wild-type 2-isopropylmalate synthase (IMPS, encoded by leuA) with a feedback insensitive mutant (IMPS-G462D), 2-ketoisocaproate was accumulated to a concentration of 1.6 g/L, and enhanced 3-methyl-1-butanol production was achieved (Connor and Liao, 2008).

Eliminating feedback inhibition can be accomplished by mutating the inhibitor-binding pockets, but also by simply removing the regulatory domain or relocating the enzyme to a different compartment within the cell. For example, the biosynthesis of L-phenylalanine is subject to feedback inhibition, with chorismate mutase-prephenate dehydratase (CM-PDT) as the major controlling point. The E. coli CM-PDT contains three distinct domains: CM (residues 1–109), PDT (residues 101–285), and the regulatory domain (residues 286–386). Removal of the regulatory domain eliminated the feedback inhibition by L-phenylalanine while retaining CM-PDT activities. A glucose yield of 0.21 g/g glucose, which is 38% of the theoretical maximum, could be achieved through the overexpression of the truncated CM-PDT (Baez-Viveros et al., 2004). Another example is the introduction of a truncated version of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) to improve the efficiency of the mevalonate pathway and the titer of the corresponding products. HMGR, consisting of a transmembrane domain and a catalytic domain, is the major rate-limiting and controlling enzyme of the mevalonate pathway (Donald et al., 1997). Through the truncation of the transmembrane domain, the desired protein was relocated to the cytosol as the soluble form, and the characterized regulatory features of HMGR were not observed. Consequently, the deregulated HMGR led to significantly enhanced production of a series of medically important drugs and chemicals, such as squalene (Donald et al., 1997; Rico et al., 2010), artemisinin (Ro et al., 2006) and taxol precursors (Engels et al., 2008), and ganoderic acid (Xu et al., 2012).

6. Engineering protein complexes to improve pathway performance

To improve the efficiency of pathways containing sequential biochemical reactions, natural systems have evolved to localize pathway enzymes in close proximity by means of protein complexes or microcompartments. The DmpGF complex to channel the toxic intermediate acetaldehyde (Manjasetty et al., 2003) and the carboxysome in cyanobacteria to increase the efficiency of carbon fixation (Dou et al., 2008) serve as two classic examples of natural multi-enzyme complexes. Protein co-localization can not only increase pathway flux via higher local metabolite concentration, but also prevent the release of potentially toxic intermediates into the cell. Therefore, the organization of multi-protein complexes is particularly desirable when the affinity of the pathway enzymes towards the substrate is low, or toxic intermediates are generated in the sequential reactions.

The simplest way to assemble the protein complexes is to fuse metabolic enzymes that catalyze successive reactions together. For example, fusion of FPP synthase and farnesene synthase resulted in increased farnesene production and eliminated formation of a side product, farnesol, when compared to free enzymes (Wang et al., 2011). In another project, to increase the pathway flux to bisabolene in S. cerevisiae, the endogenous farnesyl diphosphate synthase (ERG20) was fused to bisabolene synthase (AgBIS) using the flexible Gly-Gly-Gly-Ser (GGGS) linker, resulting in the increased production of bisabolene 2-fold greater than the individually expressed genes (Ozaydin et al., 2012). As simple as protein fusion is, this method suffers from several limitations prohibiting it from being widely applied to pathway optimization. There are a limited number of proteins that can be fused without affecting the enzyme activity and protein expression level cannot be balanced for enzyme activity.

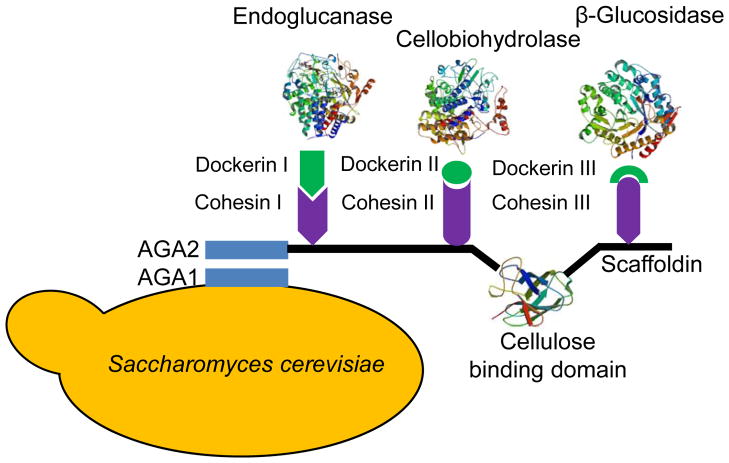

A more flexible method to co-localize sequential pathway enzymes is to use a synthetic protein scaffold, carrying multiple protein-protein interaction domains to allow the specific docking of pathway enzymes (Conrado et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2012). In addition, the modularity of the synthetic scaffold enables the optimization of the enzyme stoichiometry by varying the numbers of binding domains on the scaffold. This approach was first validated by increasing the efficiency of the mevalonate biosynthetic pathway consisting of an acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (AtoB), a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase (HMGS), and a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) (Dueber et al., 2009). AtoB, HMGS, and HMGR were tagged with peptide ligands and organized on an artificial scaffold. The optimal scaffold resulted in a 77-fold higher titer than that used by individually expressed proteins. The improvement was derived from a balanced pathway flux, which prevented the accumulation of the toxic intermediate and decreased superfluous protein expression level. Another successful example of protein complex engineering is the design and engineering of an artificial cellulosome (Wen et al., 2010) or hemicellulosome (Sun et al., 2012) by yeast cell surface display, which enabled the engineered S. cerevisiae to convert cellulose or xylan directly into bioethanol. In the assembly of a mini-cellulosome (Fig. 3), three component enzymes, endoglucanase, cellobiohydrolase, and β-glucosidase, were co-localized onto the yeast surface associated scaffoldin through high affinity interaction between cohesins and dockerins. The achieved enzyme-enzyme, enzyme-proximity, and cellulose-enzyme-cell synergy resulted in efficient consolidated bioprocessing (CBP), which integrated enzyme production, cellulose degradation, and fermentation in a single step, promising cost-effective production of biofuels (Fan et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2010).

Figure 3.

Yeast cell surface display of a tri-functional minicellulosome. The functional components of a cellulosome, including the endoglucanase, cellobiohydrolase, β-glucosidase, and the cellulose binding domain were assembled onto the yeast cell surface via scaffoldin. The specific interaction between cohesin and dockerin allows the tailored design of a functional minicellulosome.

7. Design and engineering of biosensors for pathway optimization

One increasingly important technology in high-throughput metabolic engineering and synthetic biology are biosensors (Michener et al., 2012). Generally, biosensors can be developed based on proteins (Zhang and Keasling, 2011), RNAs (Montange and Batey, 2008), and even whole cells (Pfleger et al., 2007). Here, we will focus on protein-based biosensors, which can be either naturally-existing or purposely engineered. To accommodate metabolic engineering or synthetic biology studies, a biosensor should be able to couple the presence or concentration of a specific molecule to a detectable and high-throughput compatible signal, such as fluorescence or antibiotic tolerance (Michener et al., 2012; Zhang and Keasling, 2011). Particularly, transcription factors that respond to precursors, intermediates, or products in synthetic pathways are the best candidates to initiate biosensor development. For example, a biosensor based on the transcriptional factor Lrp was developed to detect intracellular L-methionine in Corynebacterium glutamicum. This biosensor, which exhibited a linear relationship between cytoplasmic concentrations of the effector amino acid and the fluorescence output, was successfully used to isolate L-methionine over-producing mutants by high-throughput screening (Mustafi et al., 2012).

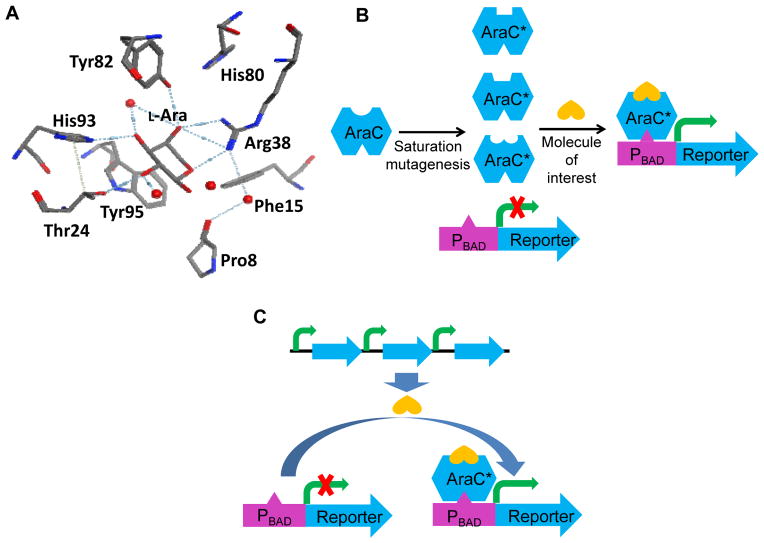

Although biosensor-based technology enables (ultra) high-throughput screening, its wide application in pathway engineering is hindered by the limited number of transcription factors or other sensing proteins responsive to the molecules of interest, such as industrial chemicals, drugs, and biofuels. When a suitable candidate does not naturally exist, directed evolution becomes a powerful tool to engineer a synthetic biosensor by taking advantage of the flexibility and plasticity of some transcription factors in molecular recognition. To demonstrate the feasibility of this strategy, Tang and coworkers engineered the L-arabinose responsive transcription factor, AraC, to be D-arabinose activated, by screening a library of AraC mutants (Tang et al., 2008). Furthermore, the AraC regulator was engineered to be mevalonate responsive, and the customized sensor was used for mevalonate pathway engineering (Tang and Cirino, 2011). In this work, a library of AraC mutants was created by simultaneous saturation mutagenesis of the effector-binding pocket (P8, T24, H80, Y82, and H93), as depicted in Fig. 4A. After several rounds of combined positive and negative screening, AraC-mev (P8P, T24L, H80L, Y82L, H93R) was found to be activated by mevalonate specifically (Fig. 4B). Then, as shown in Fig. 4C, the engineered biosensor was used to screen for mevalonate-overproducing strains from a randomized mevalonate pathway library. Theoretically, this general approach can be expanded to design reporters for any molecule of interest to develop high-throughput screening systems.

Figure 4.

Engineering a mevalonate responsive biosensor for mevalonate pathway engineering. (A) Binding pocket of wild-type AraC for L-arabinose (L-Ara), which was chosen as the target for saturation mutagenesis. Hydrogen bonds (dotted line) between the residues and L-arabinose are depicted. Extensive water molecules (red dots) in the binding pocket mediate the hydrogen bonds. (B) Directed evolution of AraC to respond to the desired molecule specifically. (C) Mevalonate pathway engineering using the evolved biosensor.

Another application of biosensors in pathway engineering is to control pathway expression according to the concentration of specific metabolites. Dynamic metabolic flux control via biosensors minimizes cellular burden and also prevents the accumulation of toxic intermediates by eliminating the expression of downstream proteins before sufficient substrates are available. For example, by using the acetyl phosphate biosensor to control the expression of the rate-controlling enzymes of lycopene synthesis, the production of lycopene was increased by 10-fold (Farmer and Liao, 2000). Similarly, in a recent report to increase the efficiency of fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) synthesis, the expression of an ethanol production pathway and a wax ester synthase, responsible for esterifying the fatty acids with ethanol, were placed under the control of FadR (Zhang et al., 2012). Being a fatty acyl-CoAs or free fatty acids responsive biosensor, it would not drive the expression of FAEE pathway genes until fatty acyl-CoA had accumulated to sufficient levels.

8. Protein design to engineer signaling pathways

Besides biosynthetic pathways, protein engineering can also be applied to rewire cell signaling pathways, which play important roles in cell-cell communication and decision making towards various environmental challenges. The engineered signaling pathways will not only enhance understanding of the molecular languages of cells, but also enable customized cell signaling networks to achieve desired applications (Kiel et al., 2010; Lim, 2010; Pryciak, 2009). Briefly, in a cell signaling pathway, sensors, such as receptors on the cell surface, can detect the environmental inputs, which are processed via the intracellular signaling networks to generate various outputs, including gene expression, cell growth, and cell migration. Therefore, one major goal of signaling pathway engineering involves redirecting the linkage between specific inputs and desired outputs (Lim, 2010).

Protein engineering can be applied to redirect the outputs of native receptors. As proof of concept of signaling pathway engineering, Notch transmembrane receptors were chosen as the target to generate novel outputs, by taking advantage of their modular structures (Sprinzak et al., 2010). Notch and Delta are both transmembrane proteins, which play important roles in communication between neighboring cells. When Delta in one cell binds to Notch in a neighboring cell, the cytoplasmic domain of Notch receptors, which is a transcription factor, is released by protease cleavage. The release of this transcription factor activates the expression of target genes. By replacing the system with an alternative transcription factor, the chimeric Notch can generate a novel transcriptional output. Therefore, Delta bound Notch can be used to target a new set of non-native genes. Similarly, this strategy was expanded to engineer other modular receptors that release the transcription factor through other mechanisms, other than proteolysis (Barnea et al., 2008).

Although engineering of signaling pathways can produce new outputs, the design of signaling networks that can sense novel, orthogonal, and even user-defined inputs is more desirable in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. To achieve this goal, a strategy known as RASSL (Receptors Activated Solely by Synthetic Ligands) which uses mutated receptors to bind novel and specific ligands, was developed based on G Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) (Conklin et al., 2008). By taking advantage of the abundance and diversity of GPCRs, the strategy was further developed to obtain a series of RASSLs that can be specifically controlled by novel molecules to generate a varied set of outputs (Armbruster et al., 2007).

9. Future Directions and Conclusions

The burgeoning success in protein and pathway engineering studies illustrate the immense level of knowledge and understanding researchers have accumulated in terms of in vitro and in vivo biocatalyst development. Nonetheless, it is still humbling how insignificant this knowledge is when compared to what is still undiscovered. Though researchers have the power to engineer target properties of enzymes, it is often accompanied by reduced functionality in another characteristic. Though this trade-off can be accepted now, the future of protein design may not have such limitations.

The multi-enzyme pathway for a tiered biocatalysis allows for complicated systems to be engineered which produce complex molecules. More intricate engineering of these systems will require high-throughput screening/selection methods to become more diversified and versatile to keep pace with the output of potential specialty chemicals. Future high-throughput screening processes could be realized through microfluidic platforms, with the ability to screen up to 108 colonies a day (Guo et al., 2012; Uhlen and Svahn, 2011), or more versatile application of FACS. With recent developments in in vivo assembly of pathway libraries in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Du et al., 2012; Ramon and Smith, 2011; Wingler and Cornish, 2011), the prospect of protein design on the pathway scale could include iterative multi-enzyme mutagenesis. Smart libraries with small but high quality mutant libraries will become even more significant in multi-enzyme mutagenesis, reducing the overall library size. As de novo protein design becomes more accurate, a distant future can be envisioned when enzymes in these pathways will not require directed evolution. Computer algorithms used for both de novo protein design and identification of critical residues will continue to improve. With the development of more powerful tools for protein design, biochemical pathways can be readily designed and constructed to efficiently produce industrially important chemicals and fuels.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM077596), the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative on Synthetic Biology, the Energy Biosciences Institute, the Department of Energy under Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) (DE-AR0000206), and the National Science Foundation as part of the Center for Enabling New Technologies through Catalysis (CENTC), CHE-0650456 for financial support in our protein and pathway engineering projects. DTE acknowledges the support of National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. JL acknowledges the support of the 3M Graduate Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KEJ, Wang Y, Simeon F, et al. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;330:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1191652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper H, Fischer C, Nevoigt E, Stephanopoulos G. Tuning genetic control through promoter engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12678–12683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504604102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S, Liao JC. Directed evolution of Methanococcus jannaschii citramalate synthase for biosynthesis of 1-propanol and 1-butanol by Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7802–7808. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S, Hanai T, Liao JC. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature. 2008;451:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature06450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez-Viveros JL, Osuna J, Hernandez-Chavez G, Soberon X, Bolivar F, et al. Metabolic engineering and protein directed evolution increase the yield of L-phenylalanine synthesized from glucose in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:516–524. doi: 10.1002/bit.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea G, Strapps W, Herrada G, Berman Y, Ong J, et al. The genetic design of signaling cascades to record receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:64–69. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710487105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian S, Liu X, Meyerowitz JT, Snow CD, Chen MM, et al. Engineered ketol-acid reductoisomerase and alcohol dehydrogenase enable anaerobic 2-methylpropan-1-ol production at theoretical yield in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2011;13:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokma E, Koronakis E, Lobedanz S, Hughes C, Koronakis V. Directed evolution of a bacterial efflux pump: adaptation of the E. coli TolC exit duct to the Pseudomonas MexAB translocase. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5339–5343. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornscheuer UT, Huisman GW, Kazlauskas RJ, Lutz S, Moore JC, et al. Engineering the third wave of biocatalysis. Nature. 2012;485:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nature11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb RE, Si T, Zhao H. Directed evolution: an evolving and enabling synthetic biology tool. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.05.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin BR, Hsiao EC, Claeysen S, Dumuis A, Srinivasan S, et al. Engineering GPCR signaling pathways with RASSLs. Nat Methods. 2008;5:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor MR, Liao JC. Engineering of an Escherichia coli strain for the production of 3-methyl-1-butanol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5769–5775. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00468-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrado RJ, Varner JD, DeLisa MP. Engineering the spatial organization of metabolic enzymes: mimicking nature’s synergy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crameri A, Dawes G, Rodriguez E, Jr, Silver S, Stemmer WP. Molecular evolution of an arsenate detoxification pathway by DNA shuffling. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:436–438. doi: 10.1038/nbt0597-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damborsky J, Brezovsky J. Computational tools for designing and engineering biocatalysts. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald KA, Hampton RY, Fritz IB. Effects of overproduction of the catalytic domain of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase on squalene synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3341–3344. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3341-3344.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Z, Heinhorst S, Williams EB, Murin CD, Shively JM, et al. CO2 fixation kinetics of Halothiobacillus neapolitanus mutant carboxysomes lacking carbonic anhydrase suggest the shell acts as a diffusional barrier for CO2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10377–10384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Shao Z, Zhao H. Engineering microbial factories for synthesis of value-added products. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:873–890. doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-0970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Yuan Y, Si T, Lian J, Zhao H. Customized optimization of metabolic pathways by combinatorial transcriptional engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueber JE, Wu GC, Malmirchegini GR, Moon TS, Petzold CJ, et al. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels B, Dahm P, Jennewein S. Metabolic engineering of taxadiene biosynthesis in yeast as a first step towards Taxol (Paclitaxel) production. Metab Eng. 2008;10:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BS, Chen Y, Metcalf WW, Zhao H, Kelleher NL. Directed evolution of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase AdmK generates new andrimid derivatives in vivo. Chem Biol. 2011;18:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan LH, Zhang ZJ, Yu XY, Xue YX, Tan TW. Self-surface assembly of cellulosomes with two miniscaffoldins on Saccharomyces cerevisiae for cellulosic ethanol production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13260–13265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209856109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer WR, Liao JC. Improving lycopene production in Escherichia coli by engineering metabolic control. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:533–537. doi: 10.1038/75398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo MT, Rotem A, Heyman JA, Weitz DA. Droplet microfluidics for high-throughput biological assays. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2146–2155. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha SJ, Galazka JM, Joong Oh E, Kordic V, Kim H, et al. Energetic benefits and rapid cellobiose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing cellobiose phosphorylase and mutant cellodextrin transporters. Metab Eng. 2012;15:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Williams LS, Umbarger HE. Regulation of synthesis of the branched-chain amino acids and cognate aminoacyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetases of Escherichia coli: a common regulatory element. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:1380–1386. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.3.1380-1386.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jez JM, Bowman ME, Noel JP. Structure-guided programming of polyketide chain-length determination in chalcone synthase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14829–14838. doi: 10.1021/bi015621z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jez JM, Bowman ME, Noel JP. Expanding the biosynthetic repertoire of plant type III polyketide synthases by altering starter molecule specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5319–5324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082590499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Kim SW, Keasling JD. Low-copy plasmids can perform as well as or better than high-copy plasmids for metabolic engineering of bacteria. Metab Eng. 2000;2:328–338. doi: 10.1006/mben.2000.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keasling JD. Manufacturing Molecules Through Metabolic Engineering. Science. 2010;330:1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1193990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla C, Keasling JD. Timeline - Metabolic engineering for drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:1019–1025. doi: 10.1038/nrd1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel C, Yus E, Serrano L. Engineering signal transduction pathways. Cell. 2010;140:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahulec S, Klimacek M, Nidetzky B. Engineering of a matched pair of xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase for xylose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol J. 2009;4:684–694. doi: 10.1002/biot.200800334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, DeLoache WC, Dueber JE. Spatial organization of enzymes for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2012;14:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PC, Petri R, Mijts BN, Watts KT, Schmidt-Dannert C. Directed evolution of Escherichia coli farnesyl diphosphate synthase (IspA) reveals novel structural determinants of chain length specificity. Metab Eng. 2005;7:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard E, Ajikumar PK, Thayer K, Xiao WH, Mo JD, et al. Combining metabolic and protein engineering of a terpenoid biosynthetic pathway for overproduction and selectivity control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13654–13659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006138107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WA. Designing customized cell signalling circuits. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:393–403. doi: 10.1038/nrm2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjasetty BA, Powlowski J, Vrielink A. Crystal structure of a bifunctional aldolase-dehydrogenase: sequestering a reactive and volatile intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6992–6997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1236794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushika A, Watanabe S, Kodaki T, Makino K, Inoue H, et al. Expression of protein engineered NADP+-dependent xylitol dehydrogenase increases ethanol production from xylose in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;81:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michener JK, Thodey K, Liang JC, Smolke CD. Applications of genetically-encoded biosensors for the construction and control of biosynthetic pathways. Metab Eng. 2012;14:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Batey RT. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafi N, Grunberger A, Kohlheyer D, Bott M, Frunzke J. The development and application of a single-cell biosensor for the detection of L-methionine and branched-chain amino acids. Metab Eng. 2012;14:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair NU, Zhao H. Evolution in reverse: engineering a D-xylose-specific xylose reductase. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1213–1215. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair NU, Zhao H. Selective reduction of xylose to xylitol from a mixture of hemicellulosic sugars. Metab Eng. 2010;12:462–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaydin B, Burd H, Lee TS, Keasling JD. Carotenoid-based phenotypic screen of the yeast deletion collection reveals new genes with roles in isoprenoid production. Metab Eng. 2012;15:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavelka A, Chovancova E, Damborsky J. HotSpot Wizard: a web server for identification of hot spots in protein engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W376–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger BF, Pitera DJ, Smolke DC, Keasling JD. Combinatorial engineering of intergenic regions in operons tunes expression of multiple genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1027–1032. doi: 10.1038/nbt1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger BF, Pitera DJ, Newman JD, Martin VJ, Keasling JD. Microbial sensors for small molecules: development of a mevalonate biosensor. Metab Eng. 2007;9:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleiss J. Protein design in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:611–617. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryciak PM. Designing new cellular signaling pathways. Chem Biol. 2009;16:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quin MB, Schmidt-Dannert C. Engineering of biocatalysts - from evolution to creation. ACS Catal. 2011;1:1017–1021. doi: 10.1021/cs200217t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon A, Smith HO. Single-step linker-based combinatorial assembly of promoter and gene cassettes for pathway engineering. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:549–555. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding-Johanson AM, Batth TS, Chan R, Krupa R, Szmidt HL, et al. Targeted proteomics for metabolic pathway optimization: application to terpene production. Metab Eng. 2011;13:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rico J, Pardo E, Orejas M. Enhanced production of a plant monoterpene by overexpression of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase catalytic domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6449–6454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02987-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro DK, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, Fisher KJ, Newman KL, et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, DeChancie J, et al. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature. 2008;453:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Pitel CM-HC, Chen W, Zhao H. Directed evolution tools in bioproduct and bioprocess development. In: Yang S-T, editor. Bioprocessing for value-added products from renewable resources: New technologies and applications. Elsevier Science; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Pitel SB, Zhao H. Recent advances in biocatalysis by directed enzyme evolution. Comb Chem High T Scr. 2006;9:247–257. doi: 10.2174/138620706776843183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runquist D, Hahn-Hagerdal B, Bettiga M. Increased ethanol productivity in xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae via a randomly mutagenized xylose reductase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:7796–7802. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01505-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z, Luo Y, Zhao H. Rapid characterization and engineering of natural product biosynthetic pathways via DNA assembler. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:1056–1059. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00338g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen CR, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for 1-butanol and 1-propanol production via the keto-acid pathways. Metab Eng. 2008;10:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JB, Zanghellini A, Lovick HM, Kiss G, Lambert AR, et al. Computational design of an enzyme catalyst for a stereoselective bimolecular Diels-Alder reaction. Science. 2010;329:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1190239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolke CD, Carrier TA, Keasling JD. Coordinated, differential expression of two genes through directed mRNA cleavage and stabilization by secondary structures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5399–5405. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5399-5405.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzak D, Lakhanpal A, Lebon L, Santat LA, Fontes ME, et al. Cis-interactions between Notch and Delta generate mutually exclusive signalling states. Nature. 2010;465:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Wen F, Si T, Xu JH, Zhao H. Direct conversion of xylan to ethanol by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains displaying an engineered minihemicellulosome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3837–3845. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07679-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SY, Cirino PC. Design and application of a mevalonate-responsive regulatory protein. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1084–1086. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SY, Fazelinia H, Cirino PC. AraC regulatory protein mutants with altered effector specificity. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5267–5271. doi: 10.1021/ja7109053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge T, Hisano T, Taguchi S, Doi Y. Alteration of chain length substrate specificity of Aeromonas caviae R-enantiomer-specific enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase through site-directed mutagenesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4830–4836. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4830-4836.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlen M, Svahn HA. Lab on a chip technologies for bioenergy and biosustainability research. Lab Chip. 2011;11:3389–3393. doi: 10.1039/c1lc90063c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Yoon SH, Jang HJ, Chung YR, Kim JY, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for alpha-farnesene production. Metab Eng. 2011;13:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Si T, Zhao H. Biocatalyst development by directed evolution. Bioresour Technol. 2012;115:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen F, Sun J, Zhao H. Yeast surface display of trifunctional minicellulosomes for simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of cellulose to ethanol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:1251–1260. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01687-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingler LM, Cornish VW. Reiterative Recombination for the in vivo assembly of libraries of multigene pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15135–15140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100507108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JW, Xu YN, Zhong JJ. Enhancement of ganoderic acid accumulation by overexpression of an N-terminally truncated 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene in the basidiomycete Ganoderma lucidum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7968–7976. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01263-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikuni Y, Dietrich JA, Nowroozi FF, Babbitt PC, Keasling JD. Redesigning enzymes based on adaptive evolution for optimal function in synthetic metabolic pathways. Chem Biol. 2008;15:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EM, Comer AD, Huang H, Alper HS. A molecular transporter engineering approach to improving xylose catabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2012;14:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha W, Shao Z, Frost JW, Zhao H. Rational pathway engineering of type I fatty acid synthase allows the biosynthesis of triacetic acid lactone from D-glucose in vivo. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4534453–4534455. doi: 10.1021/ja0317271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Keasling J. Biosensors and their applications in microbial metabolic engineering. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Carothers JM, Keasling JD. Design of a dynamic sensor-regulator system for production of chemicals and fuels derived from fatty acids. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:354–359. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg DS, Liao JC. Expanding metabolism for biosynthesis of nonnatural alcohols. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20653–20658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807157106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]