Abstract

Introduction

The pathophysiology of delirium after cardiac surgery is largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether increased concentration of preoperative and postoperative plasma cortisol predicts the development of delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. A second aim was to assess whether the association between cortisol and delirium is stress related or mediated by other pathologies, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or cognitive impairment.

Methods

The patients were examined 1 day preoperatively with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Trail Making Test to screen for depression and for cognitive impairment, respectively. Blood samples for cortisol levels were collected both preoperatively and postoperatively. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit was used within the first 5 days postoperatively to screen for a diagnosis of delirium.

Results

Postoperative delirium developed in 36% (41 of 113) of participants. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed two groups independently associated with an increased risk of developing delirium: those with preoperatively raised cortisol levels; and those with a preoperative diagnosis of MDD associated with raised levels of cortisol postoperatively. According to receiver operating characteristic analysis, the most optimal cutoff values of the preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentration that predict the development of delirium were 353.55 nmol/l and 994.10 nmol/l, respectively.

Conclusion

Raised perioperative plasma cortisol concentrations are associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. This may be an important pathophysiological consideration in the increased risk of postoperative delirium seen in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of MDD.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease is the single largest cause of death in developed countries, and one of the leading contributors to death in the developing world [1,2]. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is a lifesaving treatment for severe ischemic heart disease. However, this procedure is associated with neuropsychiatric complications. These complications include delirium, which substantially worsens postoperative recovery and prognosis [3,4].

According to recent studies, the most prominent factors contributing to postoperative delirium include comorbid load (atrial fibrillation, prior stroke, anemia, peripheral vascular disease) as well as psychiatric comorbidity such as cognitive impairment and preoperative major depressive disorder (MDD) [5-7]. The pathological association between MDD and postoperative delirium is unclear. These disorders have been proposed to be linked by a greater rise in plasma cortisol, interleukins and abnormalities in amino acids [5,7,8]. However, few studies have attempted to or been able to identify the pathogenesis of delirium following cardiac interventions, although two recent important studies suggest an association with raised postoperative cortisol levels [9,10], whilst Plaschke and colleagues have additionally implicated increased levels of IL-6 [10]. These authors hypothesize that the increased cortisol level is a stress marker. However, although current thinking implicates cortisol and cytokine abnormalities in both MDD and cognitive impairment, neither of these was screened for in the studies cited above [9,10]. As such, the precise delineation as to whether this was related to surgical stress rather than additional neuropsychiatric comorbidities remains unclear. The failure to assess for comorbidities such as MDD, cognitive impairment and impaired executive function may therefore represent a confound in the accurate interpretation of prior studies.

In light of this, the primary objective of the current study was to investigate the association between preoperative and postoperative plasma cortisol concentrations and the development of postoperative delirium. The secondary objective was to assess whether any association between cortisol and delirium is stress related or mediated by way of MDD or cognitive impairment. We hypothesized that: delirium after CABG surgery is independently associated with increased preoperative cortisol levels; these raised cortisol levels may be related to pre-existing conditions, such as MDD, cognitive disturbances and aging; increased reactivity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis associated with MDD results in a greater cortisol response postoperatively as compared with patients without MDD; and patients with MDD are at a greater risk of delirium postoperatively as a consequence of these mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Overview

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz, Poland and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted in the 14-bed cardiac surgical intensive care unit (ICU) of a university teaching hospital (University Hospital, Central Veterans Hospital, Poland) between May and September 2011. The subjects signed an informed consent the day before their operation. The inclusion criteria were: consecutive adult patients scheduled for CABG surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. The exclusion criteria were as follows: concomitant surgery other than CABG; history of adrenal gland disease; history of glucocorticoid therapy within the last year; non-Polish-speaking subjects; illiteracy; and patients with pronounced hearing and/or visual impairment.

Preoperative psychiatric and psychological procedures

The study population was examined by a psychiatrist (JK) on the day prior to the scheduled operation using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Trail Making Test Part B (TMT-B) to assess global cognition, and executive functions, respectively. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview was additionally employed to assess for a diagnosis of MDD.

The MoCA was designed as a rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. This instrument assesses different cognitive domains: attention and concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuoconstructional skills, conceptual thinking, calculations, and orientation [11]. The TMT-B is a widely used paper-and-pencil task that evaluates the executive functions and cognitive flexibility [12]. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview is a structured diagnostic interview, developed jointly by psychiatrists and clinicians in the United States and Europe for The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition and for International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision psychiatric disorders [13].

Anesthesia and surgery

For premedication, midazolam 7.5 mg per orally 1 hour before surgery was used. Before inducing anesthesia in the patients, routine monitoring was installed: electrocardiography leads II and V5, invasive radial arterial blood pressure monitoring, central venous pressure monitoring, cerebral oxygen saturation, and peripheral oxygen saturation. A standard anesthesia technique was used for all patients. Induction of anesthesia involved fentanyl 5 to 10 μg/kg, midazolam 0.1 to 0.15 mg/kg, and rocuronium 0.6 to 0.8 mg/kg. Medication during maintenance was as follows: fentanyl in continuous intravenous infusion of dose 1 to 2 μg/kg, midazolam (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg), and interrupted doses of rocuronium. Ventilation was provided with a breathing mixture of FiO2 0.5 and air to maintain end-tidal carbon dioxide at 35 mmHg. From surgical incision to cardiopulmonary bypass connection, sevoflurane 0.5 to 1.5 vol.% was used. Intraoperative monitoring additionally included end-tidal expiratory carbon dioxide, nasopharyngeal temperature, bladder temperature, and urine output. Pulmonary artery catheter was inserted when necessary. In cases of hypotension, norepinephrine was employed to counteract profound vasodilatation, at a rate 0.05 to 1 μg/kg/minute, to maintain mean arterial pressure above 60 mmHg.

All patients underwent CABG surgery through a median sternotomy. During the study period, the surgical and cardiopulmonary bypass procedures remained similar. The patients were operated on under normothermia using antegrade cold crystalloid St Thomas' Hospital cardioplegic solution No. 2 (4 to 6°C). After surgery, all patients were transferred to the ICU and were placed on mechanical ventilation. Until extubation, 102 (90%) study patients were sedated with midazolam in continuous infusion of 0.075 to 0.2 mg/kg/hour, plus additional interrupted doses of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg morphine, while the remaining participants were sedated with propofol perfusion at a rate of 1 to 2 mg/kg/hour, targeting Ramsay Sedation Scale scores of -4 to -5. The acceptable levels of arterial blood gases (maintained at pH 7.35 to 7.45, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood 35 to 45 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood > 90 mmHg) and oxygen saturations > 90% were necessary criteria for extubation. Additionally, patients were required to be awake and cooperative, hemodynamically stable with a body temperature > 36.5°C (preferably normothermic), have no active bleeding (< 400 ml/2 hours) nor coagulopathy and to demonstrate a return of muscle strength (defined by > 5 seconds head lift/strong hand grip). As a standard, weaning from mechanical ventilation and extubation in uncomplicated cases took place 4 to 6 hours after the operation.

Intraoperative and postoperative measures were recorded on the basis of local protocols pertaining to postoperative management of patients on the cardiac ICU. The lowest intraoperative hemoglobin concentration was entered into current analysis. During the surgery and postoperatively, the presence of atrial fibrillation was recorded by 24-hour electrocardiography monitoring. One-time and multiple increases of partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood ≥ 45 mmHg and a drop of partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood ≤ 50 mmHg were recorded and entered into the analysis.

Measurement of serum cortisol and IL-2 levels

The venous blood samples were taken twice during the study period: the day prior to the surgery (baseline measurement) and on the first postoperative day, between the hours 08:00 and 09:00 a.m. The blood samples were centrifuged at 7,000 rpm for 10 minutes and were refrigerated for a maximum of 1 month at -20°C until biochemical parameters were determined. The serum cortisol concentration was measured with a competitive electrochemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay in a calibrated Elecsys 2010 analyzer (Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The normal range of plasma cortisol according to the laboratory where measurements were performed is 171 to 536 nmol/l in the morning and 63 to 327 nmol/l in the evening. The venous blood samples for IL-2 were taken on the first day postoperatively, between the hours of 08:00 and 09:00 a.m. The serum IL-2 concentration was determined by chemiluminescent immunoassay technology. The normal concentration of plasma IL-2 according to the laboratory where the measurement was performed is < 710 U/ml. The tests were conducted by investigators that were blinded to clinical data.

Delirium diagnosis

None of the patients had preoperative delirium while being assessed according to the Confusion Assessment Method. Following surgical interventions, the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit was used to diagnose delirium [14]. Each individual was assessed by one of the study psychiatrists twice a day (from 08:00 to 10:00 a.m. and from 08:00 to 10:00 p.m.) within the first 5 days after surgery. Before each administration of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit, the level of sedation/arousal was assessed using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale [15]. If the patient was deeply sedated or was unarousable (-4 or -5 on the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale), evaluation was stopped and repeated later. If the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale was above -4 (-3 through +4), assessment with the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit was administered.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). For categorical variables, the number of observations (n) and fraction (%) were calculated. Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk's test for normality. Differences between two independent samples for continuous data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test (since the distributions of variables were different from normal).

For categorical variables, statistical analysis was based on the chi-squared test or the chi-squared test with Yates' adjustment. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the correlation between two quantitative variables. The minimum study sample size was calculated using the power analysis, estimating the expected effects from the pilot data and assuming an alpha level of 0.10 and a power of 80% (minimum sample size for each group is 37 patients).

Distributions for postoperative cortisol levels were different from normal in both depression and nondepression groups (P < 0.001). Similarly, the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not satisfied for postoperative cortisol levels (P < 0.01). The nonparametric Friedman's version of analysis of variance was thus used to compare cortisol before and after CABG surgery considering depression. Initially, baseline and perioperative variables were evaluated for univariate association with postoperative delirium. For quantitative variables (preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentration), significantly associated with the occurrence of delirium, receiver operating characteristic curves were drawn and decision thresholds were found. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and standard errors were also presented. Factors significant in univariate comparisons (P < 0.10) were included in a forward stepwise logistic regression model to identify the set of the independent risk factors for delirium. The results were considered significant for P < 0.05. All of the calculations were performed using STATISTICA (version 9, 2009; StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) and SPSS (SPSS Statistics, version 19; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) software.

Results

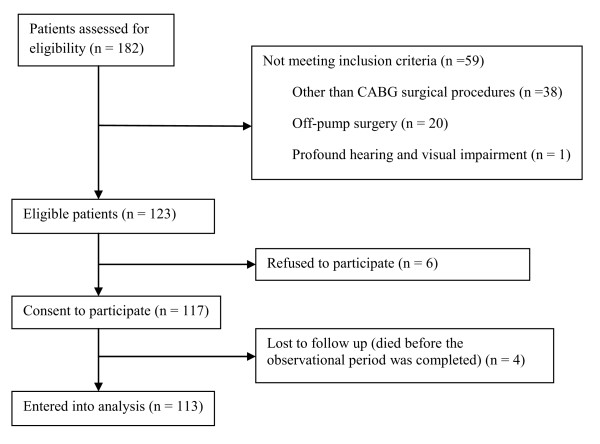

One hundred and eighty-two patients underwent CABG surgery during the study period; of these, 59 subjects did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Baseline demographic characteristics and patients' comorbidities are presented in Table 1. Postoperative delirium developed in 36% (41 of 113) of patients. The median duration of delirium was 3.5 days (IQR = 2 to 4). The frequency of diagnosis of delirium decreased with an increasing number of postoperative days (day 1, n = 22, 54%; day 2, n = 13, 32%; day 3, n = 4, 10%; day 4, n = 1, 2%; day 5, n = 1, 2%). Patients with postoperative delirium had a significantly longer stay in the ICU (6 vs. 2 days; P < 0.0001) and a longer total duration of hospitalization (19 vs. 11 days; P < 0.0001) compared with patients who did not develop delirium.

Figure 1.

Number of patients excluded and included in the data analysis. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and comorbidities of all 113 patients enrolled in the study

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Agea | 64 | (59 to 71) |

| Gender male | 90 | 79.65 |

| Years of education | ||

| Between 1 and 7 years | 31 | 28 |

| Between 8 and 11 years | 66 | 58 |

| 12 years or more | 16 | 14 |

| Living area | ||

| City > 100,000 people | 54 | 48 |

| City < 100,00 people | 33 | 29 |

| Country | 26 | 23 |

| Social status | ||

| Living with family | 100 | 88.5 |

| Living alone | 13 | 11.5 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | ||

| Depression | 18 | 16 |

| TMT-B scorea | 130 | (96 to 200) |

| MoCA scorea | 26 | (24 to 27) |

| MoCA score < 25 | 36 | 32 |

| Physical comorbidities | ||

| Anemia (hemoglobin < 10 mg/dl) | 18 | 16 |

| Urea concentration > 7 mmol/l | 33 | 29.2 |

| Creatinine concentration > 120 μmol/l | 7 | 6.2 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 23 | 20.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9 | 8 |

| Arterial hypertension | 94 | 83 |

| Diabetes | 39 | 35 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 | 5.3 |

| New York Heart Association grade | ||

| 0 | 13 | 11 |

| I | 30 | 27 |

| II | 52 | 46 |

| III | 18 | 16 |

| IV | - | |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society degree | ||

| 0 | 4 | 4 |

| I | 8 | 7 |

| II | 48 | 42 |

| III | 50 | 44 |

| IV | 3 | 3 |

MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TMT-B, Trail Making Test Part B. aFor continuous variables, the median and interquartile range is given.

The results of the univariate analysis of variables related to the condition of participants, anesthesia and surgical procedures are shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4. The unadjusted risk of postoperative delirium was higher both for patients with increased preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentrations (odds ratio = 1.004, P = 0.006; odds ratio = 1.002, P < 0.0001, respectively). Subjects with higher preoperative and postoperative cortisol level remained at increased risk of developing delirium after controlling for the following variables significant in univariable analysis: age, gender, cognitive performance (MoCA and TMT-B scores), preoperative urea, creatinine, hemoglobin concentration, peripheral vascular disease, duration of surgery, dose of midazolam, intraoperative hemoglobin level, partial pressure of oxygen, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, atrial fibrillation, and IL-2 concentration. However, after controlling for preoperative depression, only preoperative cortisol concentration remained significant, irrespective of the cortisol level after surgery (Table 5).

Table 2.

Biomarkers and variables related to demography and mental condition of patients analyzed in univariate analysis

| Variable | Nondelirious (n = 72) | Delirious (n = 41) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.5 (58 to 67.5) | 68.8 (64 to 74) | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.20) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender female | 11 (15.28%) | 12 (29.27%) | 2.29 (0.92 to 5.74) | 0.076 |

| MoCA score | 26 (25 to 27) | 25 (23 to 26) | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.94) | 0.0001 |

| TMT-B score | 100 (90 to 161.5) | 210 (145 to 300) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | < 0.0001 |

| Depression | 2 (2.78%) | 16 (39.02%) | 22.40 (6.72 to 74.65) | < 0.0001 |

| Preoperative cortisol (nmol/l) | 316.5 (239.6 to 423) | 444.8 (288.7 to 528.2) | 1.004 (1.001 to 1.006) | 0.006 |

| Postoperative cortisol (nmol/l) | 876.3 (672.1 to 1,101) | 1,162 (910 to 1,505) | 1.002 (1.001 to 1.003) | < 0.0001 |

| Postoperative IL-2 (U/ml) | 721.5 (569.5 to 1,043) | 1,179 (875 to 1,414) | 1.002 (1.001 to 1.003) | < 0.0001 |

Data presented as n (%); for continuous variables the median and interquartile range is given. CI, confidence interval; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TMT-B, Trail Making Test Part B.

Table 3.

Variables related to physical condition of patients analyzed in univariate analysis

| Variable | Nondelirious (n = 72) | Delirious (n = 41) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral vascular diseasea | 11 (15.28%) | 12 (29.27%) | 2.29 (0.92 to 5.74) | 0.076 |

| Urea concentration (mmol/l)a | 5.6 (4.9 to 7.15) | 6.5 (5.5 to 7.7) | 1.19 (1.02 to 1.39) | 0.008 |

| Creatinine concentration (μmol/l)a | 74 (62.5 to 90) | 78.5 (70 to 99.5) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.041 |

| Anemiaa, b | 7 (9.72%) | 11 (26.83%) | 3.40 (1.25 to 9.30) | 0.017 |

| Atrial fibrillationc | 3 (4.17%) | 12 (29.3%) | 5.70 (2.13 to 15.31) | 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseasea | 2 (2.78%) | 4 (9.76%) | 3.78 (0.73 to 19.50) | 0.112 |

| Arterial hypertensiona | 59 (81.94%) | 94 (85.37%) | 1.29 (0.45 to 3.68) | 0.640 |

| Diabetesa | 24 (33.33%) | 15 (36.59%) | 1.15 (0.52 to 2.57) | 0.727 |

| NYHA grade ≥ 3a | 11 (15.28%) | 7 (17.07%) | 1.14 (0.41 to 3.22) | 0.802 |

| CCS degree ≥ 3a | 30 (41.67%) | 23 (56.10%) | 1.79 (0.83 to 3.87) | 0.139 |

Data presented as n (%); for continuous variables the median and interquartile range is given. CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CI, confidence interval; NYHA, New York Heart Association. aPreoperative variable. bHemoglobin concentration < 10 mg/dl. cPostoperative variable.

Table 4.

Variables related to anesthesia and surgery analyzed in univariate analysis

| Variable | Nondelirious (n = 72) | Delirious (n = 41) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose of midazolam during surgery (mg) | 46.2 (35 to 50) | 50 (45 to 50) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.08) | 0.011 |

| Duration of surgery (hours) | 3 (2.5 to 3.5) | 3.5 (3 to 4) | 1.06 (0.83 to 1.35) | 0.051 |

| Hemoglobin concentrationa, b (mg/dl) | 8.9 (7.8 to 10.7) | 7.9 (6.5 to 8.6) | 0.66 (0.53 to 0.84) | 0.0001 |

| PaCO2 ≥ 45c, d (mmHg) | 17 (23.6%) | 19 (46.3%) | 2.79 (1.25 to 6.27) | 0.013 |

| PaO2 ≤ 60c, d (mmHg) | 13 (18.06%) | 25 (60.98%) | 7.09 (3.10 to 16.21) | < 0.0001 |

| Aortic cross-clampinga (minutes) | 485 (415 to 622) | 519 (435 to 675) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.100 |

Data presented as n (%); for continuous variables the median and interquartile range is given. CI, confidence interval. aIntraoperative variable. bThe lowest intraoperative hemoglobin concentration was recorded and entered into the analysis. cPostoperative variable. dBoth the one-time and multiple or sustained increase of partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) ≥ 45 mmHg and the drop of partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) ≤ 50 mmHg were recorded and entered into the analysis.

Table 5.

Factors independently associated with delirium after CABG surgery revealed in multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysisa

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard error | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMT-Bb | 0.016 | 0.004 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | < 0.0001 |

| Creatinine concentrationb | 0.015 | 0.012 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) | 0.191 |

| Dose of midazolam | 0.081 | 0.028 | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.15) | 0.005 |

| Preoperative cortisol | 0.005 | 0.002 | 1.005 (1.001 to 1.009) | 0.025 |

| Depressionb | 2.389 | 0.954 | 10.90 (1.68 to 70.67) | 0.012 |

| IL-2 concentrationc | 0.002 | 0.001 | 1.002 (1.001 to 1.004) | 0.004 |

| Constant | -12.964 | 2.725 | - | < 0.0001 |

CI, confidence interval; TMT-B, Trial Making Test. aThe regression model is statistically significant: χ2 = 76.889; P < 0.001. bPreoperative variable. cPostoperative variable.

According to receiver operating characteristic analysis, the most optimal cutoff values that predict the development of delirium were as follows: preoperative cortisol concentration ≥ 353.55 nmol/l, with sensitivity of 65.85% and specificity of 63.89%, positive predictive value of 50.94% and negative predictive value of 76.67% (odds ratio = 3.41) (area under the curve = 0.66; 95% confidence interval = 0.55 to 0.76; standard error = 0.05); and postoperative cortisol concentration ≥ 994.10 nmol/l, with sensitivity of 65.85% and specificity of 69.44%, positive predictive value of 55.10% and negative predictive value of 78.13% (odds ratio = 4.38) (area under the curve = 0.72; 95% confidence interval = 0.63 to 0.82; standard error = 0.05).

The median preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentrations in the whole population were 335.6 nmol/l (IQR = 247.5 to 459.5) and 940.7 nmol/l (IQR = 783.8 to 1,273), respectively. According to the Mann-Whitney U test, the median preoperative cortisol concentration was higher in patients with depression than in nondepression subjects: 483.1 nmol/l (IQR = 388.4 to 612.3) versus 318.8 nmol/l (IQR = 235.5 to 439.8) (P = 0.001), respectively. Similarly, the median postoperative cortisol concentration was higher in patients with depression compared with the nondepression group: 1,194.5 nmol/l (IQR = 936 to 1438) versus 908.4 nmol/l (IQR = 709 to 1,256) (P = 0.009), respectively. However, according to nonparametric analysis of variance, the interaction between the presence of depression and preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentration was not statistically significant (P = 0.447). This suggests that the postoperative cortisol concentration was higher than the preoperative, regardless of depression occurrence. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between preoperative cortisol and MoCA scores and between postoperative cortisol and MoCA scores were -0.21 (P = 0.025) and -0.14 (P = 0.130), respectively. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between preoperative cortisol and age and between postoperative cortisol and age were 0.18 (P = 0.049) and 0.25 (P = 0.007), respectively.

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of increased preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentration in relation to a diagnosis of preoperative MDD and cognitive impairment on the risk of developing postoperative delirium.

Among 113 patients undergoing CABG, 36% (41) developed delirium. The effect of both preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentration on the risk of developing delirium was significant after controlling for demographic, physical, cognitive, surgical and anesthetic-related factors. However, when cortisol levels were controlled for MDD, only the preoperative cortisol concentration remained significant. The final multivariate regression analysis revealed that the preoperative cortisol level, MDD, impaired executive functions, higher creatinine and IL-2 concentrations and a higher dosage of midazolam independently increase the risk of postoperative delirium.

The incidence of postoperative delirium reported in the present study is in line with findings of similar contributions related to cardiac surgery (the reported estimates vary from 3 to 50%) [16-18]. In our previous study conducted in cardiac surgery patients [19], however, the incidence of delirium was lower (11.5%) compared with those currently reported (36%). This discrepancy may be due to differences in the groups studied, diagnostic approaches and the assessment tools used. In the first contribution, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition criteria were used to diagnose delirium and the participants were younger (mean age 62 years). Moreover, screening for delirium was conducted once a day starting from the second postoperative day. All of these factors may have affected the final estimates.

In the current study, the incidence of MDD and cognitive impairment (MoCA score < 25) were 16% and 32%, respectively. This is higher than the prevalence of unipolar depression in the general population (5 to 9% for females, 2 to 3% for males) and is consistent with the prevalence of MDD in CABG patients reported in other studies (15 to 20%) [20-22]. Recent studies confirmed that cognitive impairment is common among older patients undergoing major surgery, including cardiac interventions [5,6,18,23]. Depending on the diagnostic measures employed, the prevalence of cognitive disturbances ranges between 17 and 44%, and this is consistent with the results presented here (32%) [5,6,18]. Worthy of notice is that our previous study revealed cognitive disturbances in 100 out of 563 patients (17%). In the current study, however, we used more sensitive diagnostic instruments, which additionally enabled us to diagnose milder forms of cognitive impairment [11].

A number of studies have investigated risk factors for postoperative delirium, but findings have been heterogeneous. This inconsistency of the results may be, in part, related to the multifactorial etiology of delirium. Unfortunately, the pathophysiology and biological processes underlying this neuropsychiatric syndrome are poorly described - but it is possible that different mechanisms involved in delirium act through the same final pathways. This might explain the heterogeneity of research findings.

The most consistently reported independent associations with delirium in recent studies of cardiac surgery to date include older age, preoperative cognitive impairment and MDD [5,6,18]. MDD and advanced age may contribute to delirium through the elevated level of cortisol, secondary to activation of the limbic HPA axis in such individuals [7]. In this model, glucocorticoids inhibit endothelial cell proliferation and turnover in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [24], whilst HPA axis dysregulation results in decreased hippocampus volume [25]. Two recent studies investigated the association between plasma cortisol and delirium among cardiac surgery patients [9,10]. Plaschke and colleagues reported the association between increased cortisol concentration and delirium among a heterogeneous population of cardiac surgery patients in a univariate analysis that did not control for other factors - as such, the association with and significance of raised cortisol levels were not determined [10]. Mu and colleagues showed an independent association between elevated cortisol levels and postoperative delirium in individuals who underwent CABG surgery [9]. Both of these groups propose that increased cortisol concentration may be a marker of stress response, with the caveat that surgery-related stress is probably not the only factor contributing to elevated cortisol levels. Neither group was able to determine whether hypercortisolemia was a cause or an effect of postoperative delirium in the absence of baseline cortisol measurements, samples only being collected postoperatively. Furthermore, preoperative screening for potentially confounding neuropsychiatric disorders that were associated with altered cortisol levels and with delirium were not performed.

According to the results of present study, major depression prior to surgery is strongly and independently associated with an increased risk of postoperative delirium. Interestingly, high postoperative cortisol level also increases the risk of delirium, but this association lost significance once preoperative MDD was controlled for. Moreover, according to univariate analysis, the concentration of cortisol after surgery is significantly higher among patients suffering from depression when compared with nondepression subjects. These data suggest that, regarding delirium, depression is the primary factor affecting the condition of the ICU patients. Hypercortisolemia may be the factor that mediates the impact of MDD on postoperative cognition. This interpretation should be treated with caution, however, since the postoperative cortisol concentration was higher than the preoperative one regardless of depression occurrence, according to analysis of variance. On the contrary, our analysis revealed that a higher cortisol concentration measured the day prior to surgery independently increases the risk of delirium, even after controlling for depression, cognitive performance and age. The concentration of preoperative cortisol was higher among individuals with depression compared with patients without this diagnosis; however, this difference was observed only in univariate comparisons. MDD and the associated increase in HPA axis reactivity and postoperative hypercortisolemia is probably not the only pathophysiological mechanism involved in the development of postoperative delirium. For example, a higher preoperative cortisol concentration may be another contributing factor. Unfortunately, the etiology of preoperative hypercortisolemia is unknown. It may be linked to preoperative MDD or reflect other, separate and undiscovered pathologies. According to recent publications, an increased cortisol level carries a predictive value in the development of mild cognitive impairment [26]. Moreover, higher cortisol measures have also been reported in Alzheimer's disease and are associated with poorer memory performance in subjects with cognitive decline [27,28] and alterations in HPA axis activity frequently accompany aging [29].

The current analysis revealed that delirium was significantly more frequent among patients with advancing age and with lower MoCA scores. However, older age and lower MoCA scores did not maintain significance in a multivariate analysis. Older patients significantly differed from younger participants in relation to the both preoperative and postoperative cortisol concentration. Furthermore, there was a correlation between lower MoCA scores and higher preoperative cortisol level. These findings suggest that higher cortisol levels prior to surgery that act as an independent risk factor for postoperative delirium may be associated with advanced age and the impaired cognitive performance in these participants.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several advantages. The study population was homogeneous, and the subjects were consecutive, prospectively enrolled and examined by an experienced, well-trained investigator. The analysis included a variety of factors associated with the mental and physical condition of participants, as well as those related to anesthesia and surgery. Therefore, while investigating the association between cortisol and delirium, both traumatic stress-related and psychiatric pathways were taken into consideration. To the knowledge of the authors, this represents the first study to investigate whether hypercortisolemia is a cause or an effect of delirium after cardiac surgery. This in turn allowed the analysis to control for possible confounders such as MDD and cognitive impairment, as well as factors associated with anesthesia and surgery (duration of surgery and aortic cross-clamping, dose of midazolam).

However, the study is not without limitations. The present findings cannot be considered definitive since other circulating hormones, mediators and inflammatory factors were not included in the analysis. In addition, not all prescribed medications and anesthetic agents were taken into account in the analysis, which focused on the association between the dose of midazolam and delirium. We decided to include midazolam into the analysis since this medication may decrease the level of cortisol perioperatively [30,31]. Moreover, the association between midazolam and postoperative delirium has been frequently reported [32,33]. However, the impact of other anesthetic agents that may play a role in delirium development, post-surgery sedation, as well as the impact of postoperative complications on the incidence of delirium was not assessed in this study. This being said, a recent study suggested that none of 20 different drug classes investigated (including antihypertensives, diuretics, antiplatelets and psychiatric agents) were associated with delirium after elective surgery [34].

Conclusions

On the basis of the current analysis we can conclude that patients with raised levels of cortisol prior to surgery are at significantly increased risk of postoperative delirium. This higher level of preoperative cortisol may be associated with MDD, aging and cognitive decline.

Secondly, patients with increased HPA axis reactivity secondary to pathologies such as MDD are characterized with higher postoperative cortisol concentrations compared with patients without MDD and, possibly as a consequence, are more likely to develop postoperative delirium. These observations suggest that an increased level of cortisol may be a cause rather than an effect of postoperative delirium. Preoperative neuropsychiatric screening and monitoring of cortisol levels of cardiac surgery patients combined with postoperative surveillance may improve the early detection of delirium and, indirectly, the prognosis.

Key messages

• Cardiac surgery patients with raised concentration of plasma cortisol prior to surgery are at significantly increased risk of postoperative delirium.

• A higher level of preoperative cortisol may be associated with MDD, advanced age and cognitive impairment.

• Preoperative diagnosis of MDD is an independent predictor of delirium after CABG surgery.

• Patients with a preoperative diagnosis of MDD have higher postoperative cortisol levels compared with patients without MDD, which may contribute to the development of delirium postoperatively.

Abbreviations

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; HPA: hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal; IL: interleukin; IQR: interquartile range; MDD: major depressive disorder; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TMT-B: Trial Making Test Part B.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JK designed the study, recruited the patients, conducted the neuropsychiatric evaluation and drafted the manuscript. AB participated in the study design and recruited the patients. JL collected and stored the patients' blood samples and the patients' data. JB drafted and revised the manuscript. RJ participated in the study design and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

See related commentary by Martin and Arora, http://ccforum.com/content/17/2/140

Contributor Information

Jakub Kazmierski, Email: jakub.kazmierski@umed.lodz.pl.

Andrzej Banys, Email: andrzej.banys@umed.lodz.pl.

Joanna Latek, Email: latek1@gazeta.pl.

Julius Bourke, Email: j.bourke@qmul.ac.uk.

Ryszard Jaszewski, Email: ryszard.jaszewski@umed.lodz.pl.

Acknowledgements

This study was founded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Grant No. 0174/P01/2010/70; 504-06-011. The authors gratefully acknowledge Mrs Ewa Zielinska for her help in sample collection and Dr Malgorzata Misztal for the contribution to statistical analysis.

References

- Martí-Carvajal AJ, Solà I, Lathyris D, Salanti G. Homocysteine lowering interventions for preventing cardiovascular events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;7:CD006612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006612.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaziano T, Reddy KS, Paccaud F, Horton S, Chaturvedi V. In: Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2. Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, editor. Washington, DC: The World Bank and New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. Cardiovascular disease. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detroyer E, Dobbels F, Verfaillie E, Meyfroidt G, Sergeant P, Milisen K. Is preoperative anxiety and depression associated with onset of delirium after cardiac surgery in older patients? A prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2278–2284. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BJ, Buth KJ, Arora RC, Baskett RJ. Delirium as a predictor of sepsis in post-coronary artery bypass grafting patients: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R171. doi: 10.1186/cc9273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierski J, Kowman M, Banach M, Fendler W, Okonski P, Banys A, Jaszewski R, Rysz J, Mikhailidis DP, Sobow T, Kloszewska I. IPDACS Study. Incidence and predictors of delirium after cardiac surgery: results from The IPDACS Study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, Rockett C, Inouye SK, Sellke FW, Khuri SF, Lipsitz LA, Ramlawi B, Levitsky S, Marcantonio ER. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;20:229–236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.795260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierski J, Kloszewska I. Is cortisol the key to the pathogenesis of delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery? Crit Care. 2011;15:102. doi: 10.1186/cc9372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Mast RC, van den Broek WW, Fekkes D, Pepplinkhuizen L, Habbema JD. Is delirium after cardiac surgery related to plasma amino acids and physical condition? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:57–63. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu DL, Wang DX, Li LH, Shan GJ, Li J, Yu QJ, Shi CX. High serum cortisol level is associated with increased risk of delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R238. doi: 10.1186/cc9393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaschke K, Fichtenkamm P, Schramm C, Hauth S, Martin E, Verch M, Karck M, Kopitz J. Early postoperative delirium after open-heart cardiac surgery is associated with decreased bispectral EEG and increased cortisol and interleukin-6. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2081–2089. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trailmaking Tests A and B. Washington, DC: War Department Adjutant General's Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, Speroff T, Gautam S, Bernard GR, Inouye SK. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1370–1379. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Mast RC, Roest FH. Delirium after cardiac surgery: a critical review. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41:13–30. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(96)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkiene I, Ringaitiene D, Misiuriene I, Samalavicius R, Bubulis R, Baublys A, Uzdavinys G. Incidence and precipitating factors of delirium after coronary artery bypass grafting. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2007;41:180–185. doi: 10.1080/14017430701302490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Grande LJ, Milberg WP, King EG, Lipsitz LA, Levkoff SE, Marcantonio ER. Impaired executive function is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:937–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierski J, Kowman M, Banach M, Pawelczyk T, Okonski P, Iwaszkiewicz A, Zaslonka J, Sobow T, Kloszewska I. Preoperative predictors of delirium after cardiac surgery: a preliminary study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:536–538. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully PJ, Baker RA. Depression, anxiety, and cardiac morbidity outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery: a contemporary and practical review. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2012;9:197–208. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1263.2011.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresnevaitė M, Benetis R, Taylor GJ, Jurėnienė K, Kinduris Š, Barauskienė V. Depression predicts perioperative outcomes following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2010;44:289–294. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2010.490593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer LF, Dunn CL, Moss M. Preoperative cognitive dysfunction is related to adverse postoperative outcomes in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand J, Hellsten J, Tingström A. Environmental enrichment, exercise and corticosterone affect endothelial cell proliferation in adult rat hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2008;442:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray F, Smith DW, Hutson PH. Chronic low dose corticosterone exposure decreased hippocampal cell proliferation, volume and induced anxiety and depression like behaviours in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy GM, Jacobson MW, Salmon DP, Gamst AC, Patterson TL, Goldman S, Mills PJ, Khandrika S, Galasko D. The influence of chronic stress on dementia-related diagnostic change in older adults. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:260–266. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182389a9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Bea FJ, Aisa B, Solomon A, Solas M, del Carmen Mugueta M, Winblad B, Kivipelto M, Cedazo-Mínguez A, Ramírez MJ. HPA axis dysregulation associated to apolipoprotein E4 genotype in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:829–838. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Talarico JN, Chaves EC, Lupien SJ, Nitrini R, Caramelli P. Relationship between cortisol levels and memory performance may be modulated by the presence or absence of cognitive impairment: evidence from healthy elderly, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease subjects. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:839–848. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen L, Geerlings MI, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Penninx BW, Comijs HC. Early and late life events and salivary cortisol in older persons. Psychol Med. 2009;26:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerjes W, Jerjes WK, Swinson B, Kumar S, Leeson R, Wood PJ, Kattan M, Hopper C. Midazolam in the reduction of surgical stress: a randomized clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.02.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekcan M, Celebioglu B, Demir B, Saricaoglu F, Hascelik G, Yukselen MA, Basgul E, Aypar U. The effect of premedication on preoperative anxiety. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2005;18:421–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado JR, Wysong A, van der Starre PJ, Block T, Miller C, Reitz BA. Dexmedetomidine and the reduction of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:206–217. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana Santos F, Wahlund LO, Varli F, Tadeu Velasco I, Eriksdotter Jonhagen M. Incidence, clinical features and subtypes of delirium in elderly patients treated for hip fractures. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:231–237. doi: 10.1159/000087311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelmeier DA, Thiruchelvam D, Daneman N. Delirium after elective surgery among elderly patients taking statins. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;179:645–652. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]