Abstract

Reprogramming of somatic cells into iPSCs involves a dramatic reorganization of chromatin. To identify posttranslational histone modifications that change in global abundance during this process, we have applied a quantitative mass-spectrometry-based approach. We found that iPSCs, compared to both the starting fibroblasts and a late reprogramming intermediate (pre-iPSCs), are enriched for histone modifications associated with active chromatin, and depleted for marks of transcriptional elongation and a subset of repressive modifications including H3K9me2/me3. Dissecting the contribution of H3K9methylation to reprogramming, we show that the H3K9methyltransferases Ehmt1, Ehmt2, and Setdb1 regulate global H3K9me2/me3 levels and that their depletion increases iPSC formation from both fibroblasts and pre-iPSCs. Similarly, inhibition of heterochromatin-protein-1γ (Cbx3), a protein known to recognize H3K9methylation, enhances reprogramming. Genome-wide location analysis revealed that Cbx3 predominantly binds active genes in both pre-iPSCs and pluripotent cells but with a strikingly different distribution: in pre-iPSCs, but not in ESCs, Cbx3 associates with active transcriptional start sites, suggesting a developmentally-regulated role for Cbx3 in transcriptional activation. Despite largely non-overlapping functions and the association of Cbx3 with active transcription, the H3K9methyltransferases and Cbx3 both inhibit reprogramming by repressing the pluripotency factor Nanog. Together, our findings demonstrate that Cbx3 and H3K9methylation restrict late reprogramming events, and suggest that a dramatic change in global chromatin character is an epigenetic roadblock for reprogramming.

Reprogramming of somatic cells into iPSCs by overexpression of the transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and cMyc is a fascinating, but inefficient process, with only a small subset of starting cells converting to a pluripotent state after 1–2 weeks1,2. Mechanistic insights into how chromatin regulators and chromatin states control reprogramming are only now beginning to be explored3–11. To gain insight into global chromatin changes that occur during reprogramming to iPSCs, we were interested in quantifying the post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones. We reasoned that histone PTMs with dramatic changes in global levels during reprogramming could be important for the suppression or promotion of the process.

Investigations of the role of histone PTMs during reprogramming have typically relied on the use of site-specific histone antibodies in immunostaining and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments3,12–14. While very insightful, these methods are reliant on the availability of cognate antibodies, and epitope recognition can be affected by modifications on neighboring residues or interacting factors. To circumvent these issues, we used label-free mass spectrometry (qMS)-based proteomics15,16 as an alternative approach to quantify alterations in histone PTMs during reprogramming, which is independent of antibodies (Fig S1A).

Results

Global levels of many histone PTMs change during reprogramming

To begin with, we determined the abundance of acetylation or methylation modifications at lysine (K) residues of histone H3 and H4, at the start and endpoint of reprogramming, i.e. in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and iPSCs derived from these cells. Two iPSC and two MEF lines were subjected to six independent qMS reactions per sample (see Experimental Methods), generating a highly reproducible quantification of histone PTMs in these cell types, which is summarized in Table S1.

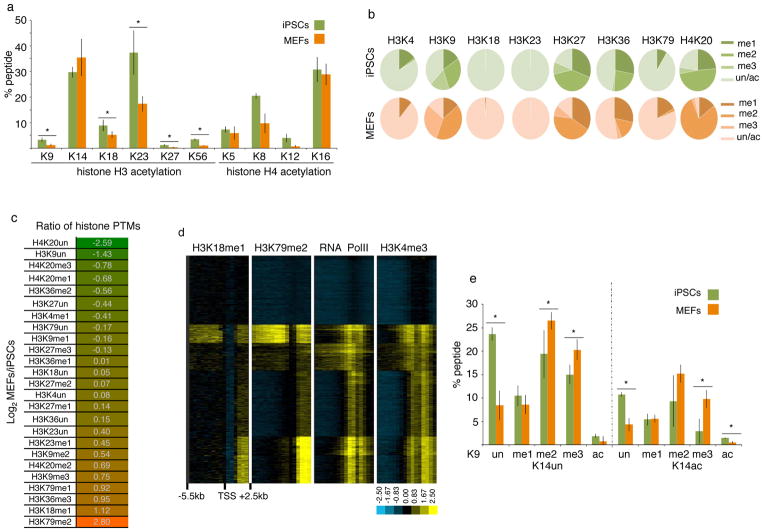

We found a wide variation in the abundance of histone acetylation across lysine residues in both histone H3 and H4. Within histone H3, acetylation was most abundant on residues K14 and K23 irrespective of the cell type analyzed (Fig 1A). Acetylation of H3K9, a mark associated with transcriptionally active or bivalent promoters and enhancers17,18, of H3K27, a mark characteristic of active enhancers19, or of H3K56, which overlaps with the binding of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG in human ESCs20, was present on less than 5% of histone H3 molecules (Fig 1A). These results potentially reflect the preferential association of this acetylation events with regulatory genomic elements compared to a broader chromatin role for H3K14 and H3K23ac. For example, H3K14 acetylation has already been implicated in DNA damage responses21. Similar variations in the extent of acetylation were found for the lysine residues of the N-terminal tail of histone H4 (Fig 1A). Importantly, almost all acetylated lysines on histone H3 and H4 were more prevalent in iPSCs than MEFs (Fig 1A). Since acetylation of lysines has been associated with active chromatin states and transcription17, our findings extend the conclusion that pluripotent cells are more euchromatic than differentiated cells22.

Figure 1. Global levels of the majority of histone PTMs differ between MEFs and iPSCs.

A) Graph displaying the percentage of acetylated (ac) lysine (K) residues in female iPSCs and MEFs. Data presented is the mean of 6 values obtained from 2 biological replicates, each analyzed three times. The asterisks indicate significantly different levels between iPSCs and MEFs at p<0.01 determined by the t-test. Error bar = standard deviation of six replicates. Source data are provided in Supp Table 1.

B) Pie charts indicating the percentage of mono- (me1), di- (me2), and tri- (me3) methylated and unmethylated (un) forms of the indicated lysine residues in female iPSCs and MEFs. The unmethylated portion represents the sum of acetylated and unacetylated isoforms. Standard deviations for six replicates and significant differences in these PTMs between iPSCs and MEFs are provided in Fig S1B.

C) Log2 ratio of the percentage of methylated and unmethylated lysines between female MEFs and iPSCs. Histone PTMs that are lower in MEFs than iPSCs are highlighted in green and those that are higher in MEFs than iPSCs in orange. The unmethylated state can be acetylated and/or unacetylated.

D) Hierarchical clustering of ChIP-chip data for H3K18me1, H3K79me2, RNA polymerase II, and H3K4me3 for 18300 genes. Each row represents the promoter region of a gene spanning −5.5kb to +2.5kb relative to the TSS, divided into sixteen 500bp fragments that display the average log ratio of probe signal intensity with blue, yellow, and grey representing lower-than-average, higher-than-average, and missing values (mostly due to lack of probes in those regions) for enrichment relative to input.

E) As in (A), except that the combination of PTMs on the histone H3 peptide containing amino acid 9 to 17 were quantified. Data presented is the mean of 6 values obtained from 2 biological replicates, each analyzed three times. The K9 residue exists in the ac, me1, me2, me3, or the unmethylated/unacetylated (un) forms, and K14 in the ac or un forms. Each combination of histone PTMs on K9 and K14 is referred to as peptide isoform. Source data are provided in Supp Table 1.

Histone methylation patterns are more complex due to the presence of mono-, di, and tri-methylation states. Similar to acetylation, there is a dramatic variation in the abundance of methylation across lysine residues in MEFs and iPSCs (Fig 1B, S1B). For methylated lysines related to transcriptional repression, such as H3K9 and H3K27, between 60–80% of the respective lysine are methylated in both MEFs and iPSCs, revealing an unexpected coverage of the genome by histones carrying these methylated residues. Methylation at lysine residues known to be associated with enhancers and promoters, for example at H3K4, is much less abundant in both cell types. Surprisingly, methylation associated with transcriptional elongation, particularly H3K36 methylation, is relatively abundant in the genome.

Analyzing differences in global histone methylation profiles between iPSCs and MEFs (Fig 1C), we found that H3K79me2 and H3K36me3, two methylation marks associated with transcriptional elongation23,24, and the relatively uncharacterized mark H3K18me125, were the top three marks that are more abundant in MEFs than iPSCs (Fig 1C). Notably, the reduction of global levels of H3K79me2 and H3K36me3 during reprogramming may be important for the generation of iPSCs since the inhibition of Dot1L, the enzyme responsible for H3K79 methylation and overexpression of H3K36me2/me3 demethylases enhance iPSC formation7–9. To better understand the function of H3K18me1, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation with an antibody specific for H3K18me1 (Fig S1C) in combination with promoter microarrays. We found that H3K18me1 is enriched in coding regions with a pattern similar to that of H3K79me2 (Fig 1D). These findings identify the association of a previously uncharacterized histone modification with transcriptional elongation. They also indicate that the most downregulated histone modifications during reprogramming are all linked to transcriptional elongation which is surprising given that pluripotent cells have been argued to be transcriptionally more permissive compared to differentiated cells26. Therefore, these modifications may have different functions in pluripotent and differentiated cells, which will be interesting to study in the future.

Among methylation marks associated with transcriptional silencing, H3K27 methylation states were not very different between iPSCs and MEFs; H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 levels were higher in MEFs than iPSCs; and H4K20me3 and H4K20me1 were more abundant in iPSCs than MEFs (Fig 1B–C, S1B). We also noted a strong increase in unmethylated H3K9 and H4K20 residues from MEFs to iPSCs that was higher than that of any methylation mark (Fig 1C), suggesting that the unmethylated state of these lysine residues is an important feature of the pluripotent state. Together, these data indicate that not all repressive methylation histone marks are depleted in iPSCs compared to MEFs, although pluripotent cells have a more euchromatic character compared to MEFs. We conclude that H3K9 and H4K20 methylation, in contrast to H3K27 methylation, partly exert their effects on reprogramming by modulation of their global levels.

Histones can be modified simultaneously on multiple amino acids. qMS offers arguably the only approach to exactly quantify combinations of PTMs that occur on the same peptide. We therefore examined the combination of acetylation and methylation that occurred within each tryptic histone peptide (i.e. in the peptides of H3 containing either K9/K14, K18/K23, or K27/K36, or in the H4 peptide carrying K5/K8/K12/K16) (Fig 1E, S1D–F). All examined histone peptides accommodate different modifications at neighboring amino acids, highlighting the complex control of histone modifications and functional output. For the H3-K9/K14 peptide, we found that repressive K9 methylation marks and the activating K14ac were often present on the same histone molecule (Fig 1E). Furthermore, although total levels of H3K14ac were similar between iPSCs and MEFs (Fig 1A), H3K14ac was significantly higher in iPSCs than MEFs when H3K9 was unmodified or acetylated on the same histone molecule (Fig 1E), indicating that modifications on the K9 residue affect the acetylation status of K14 in a cell type-specific manner. In addition, the unmodified form of the H3K9/K14 peptide (K9un/K14un) was the most prevalent isoform of this peptide in iPSCs, perhaps enabling the rapid acquisition of various modifications in response to differentiation cues (Fig 1E).

A global change in chromatin character occurs late in reprogramming

The differences in global levels of histone PTMs between MEFs and iPSCs prompted us to determine when they occur during reprogramming, and whether iPSCs are similar to ESCs in their global histone PTM profile. Although reprogramming is inefficient, intermediate stages of the process have been described1,3,11,27–29. To examine the global chromatin state in a late intermediate of reprogramming, we took advantage of pre-iPSCs. pre-iPSCs can be isolated from reprogramming cultures as a clonal population of cells with an ESC-like morphology that have efficiently repressed the somatic gene expression program but lack the expression of most pluripotency factors.3,27,30. These cells are commonly obtained when reprogramming is induced with retrovirally expressed Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and cMyc3,27,30. We reasoned that the analysis of the histone PTM profile in pre-iPSC lines would allow us to determine when global chromatin character changes occur in the reprogramming process relative to known transcriptional changes. Hence, we performed label-free qMS analysis for histone PTMs on one male ESC line, one male and one female pre-iPSC line, with least five replicate qMS data sets per cell line, and compared them to the iPSC and MEF data. Quantitative differences in histone PTMs between two cell types were confirmed directly by using chemical stable isotope labeling and subsequent mixing of the histone samples from the two cell types before MS analysis16 (Fig S2).

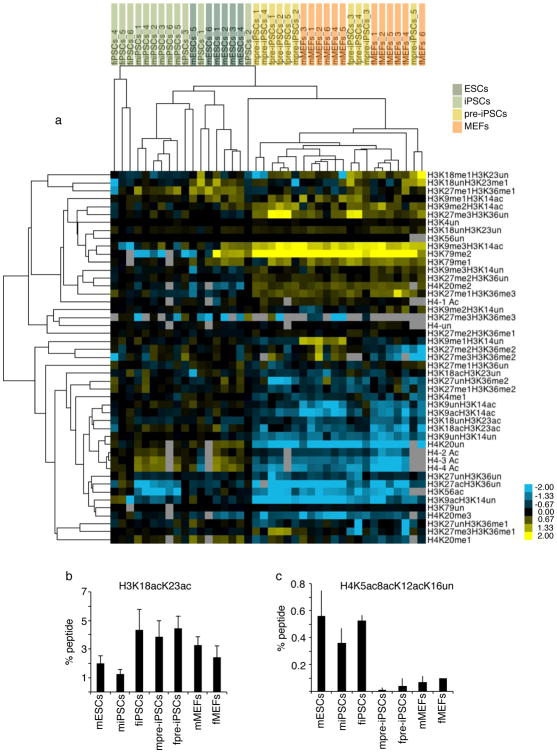

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of histone PTM levels for all replicate datasets, based on combinations of modifications per tryptic histone peptide (summarized in Table S1), demonstrated that the global chromatin character of pre-iPSCs is similar to that of MEFs (Fig 2A). Furthermore, pre-iPSCs and MEFs cluster away from both ESCs and iPSCs, which in turn are more related to each other in chromatin state (Fig 2A). In pre-iPSCs a few histone PTMs were present at an intermediate level between iPSCs and MEFs, as for instance H3K18ac/K23ac (Fig 2B), or less abundant than in any other cell lines, as for instance H4K5acK8acK12acK16un (Fig 2C). Irrespective of these differences, a shift toward the pluripotency profile is not evident for the majority of histone PTMs in pre-iPSCs. Together these findings demonstrate that ESCs and iPSCs share a similar global histone modification profile revealing a pluripotency-specific global chromatin structure. Furthermore, the transition from the MEF-like to the pluripotency-specific global chromatin character occurs late in reprogramming, after the state represented by pre-iPSCs, rather than gradually throughout the entire reprogramming process. Based on these data, we propose that the establishment of the global pluripotency-specific chromatin state constitutes an epigenetic barrier that contributes to the reprogramming block encountered by pre-iPSCs and the low overall efficiency of reprogramming to iPSCs.

Figure 2. Comparison of histone PTM profiles between ESCs, iPSCs, pre-iPSCs, and MEFs.

A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the log2 ratio of the percentage of histone isoforms for each qMS replicate in the indicated cell types relative to the average percentage of the same isoform in female iPSCs. Cell types included are: female iPSCs (fiPSCs, 6 replicates), male iPSCs (miPSCs; 6 replicates), male ESCs (mESCs, 6 replicates), female pre-iPSCs (fpre-iPSCs, 5 replicates), male pre-iPSCs (mpre-iPSCs, 5 replicates), male (mMEFs, 6 replicates), and female fibroblasts (fMEFs, 6 replicates). In the heat map, yellow represents isoforms that are more abundant than in fiPSCs and blue those that are less abundant. For the H4 peptide including amino acids 4–17, 1ac refers to the sum of isoforms that have a single acetylated lysine among K5, K8, K12 or K16; 2ac and 3ac to the sum of all isoforms with 2 and 3 acetyl marks, respectively; and 4ac to the completely acetylated peptide.

B) The graph displays the percentage of the isoform of the H3 peptide containing amino acids 18–26 that is acetylated at both K18 and K23, for the indicated cell types. Data presented is the mean of 6 values obtained from 2 biological replicates, each analyzed three times. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Source data are provided in Supp Table 1.

C) As in (B), except for the isoform of the H4 peptide containing amino acids 4–17 with acetylation at positions K5, K8, and K12, but not K16.

H3K9 methylation regulators control the efficiency of reprogramming

Our qMS approach demonstrated that pre-iPSCs and MEFs are more enriched for repressive H3K9 methylation marks than iPSCs. We therefore directed our efforts on further deconvoluting reprogramming barriers associated with the H3K9 site. Specifically, we asked whether the depletion of the writers, the histone methyltransferases (HMTases) Ehmt1, Ehmt2, and Setdb1, or the readers, the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family members Cbx1, Cbx3, and Cbx5, or overexpression of the H3K9 demethylase Jmjd2c, could modulate the efficiency of reprogramming. HP1 proteins are small proteins that have been shown to bind specifically to methylated histone H3K9 via their chromodomain in biochemical assays31,32. However, although initially identified as evolutionarily conserved regulators of heterochromatin formation, recent progress suggests additional roles for HP1 proteins in the regulation of active gene expression in euchromatic regions 33,34.

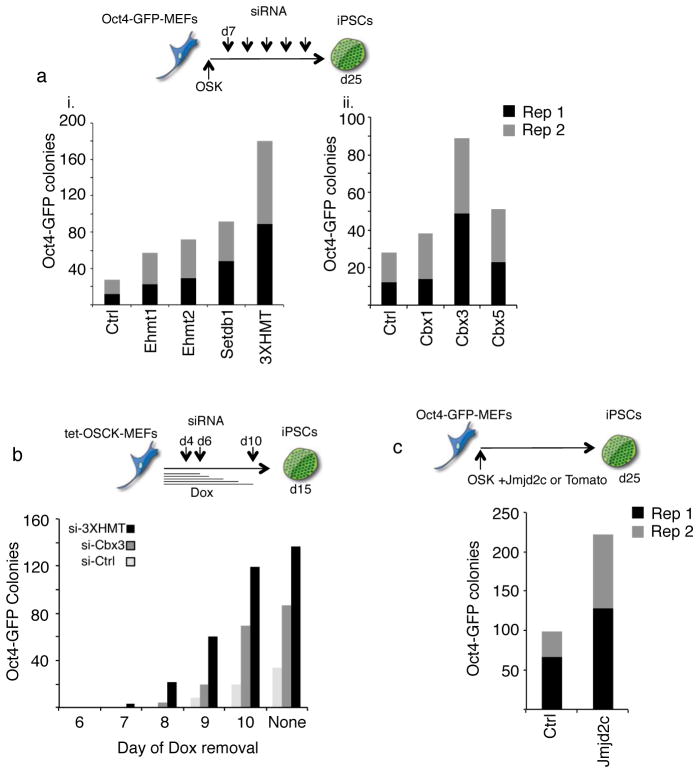

Since the knockout of some of these enzymes, like Setdb1, is known to lead to loss of pluripotency35,36, we only transiently depleted them during reprogramming by means of siRNA-mediated knockdown. Reprogramming was induced by overexpression of Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4, i.e. in the absence of ectopic cMyc, in MEFs containing GFP reporters linked to pluripotency promoters (Oct4 or Nanog). Efficient knockdown for all target genes was confirmed in each reprogramming experiment (Fig S3A). The depletion of any of the three H3K9 HMTases consistently increased the number of Oct4-GFP positive colonies at least two-fold, and simultaneous knockdown of all three HMTases (hence forth called 3XHMT) enhanced reprogramming even more efficiently (Fig 3Ai, S3Ai). GFP-positive colonies also expressed the endogenous pluripotency marker Esrrb indicating that the increase in colony number did not simply represent GFP-reporter activation (Fig S3B). Depletion of Cbx3 consistently increased the number of Oct4-GFP-positive colonies, while the effects of Cbx1 and Cbx5 interference were positive but milder and not always reproducible (Fig 3Aii, S3Aii). 3XHMT or Cbx3 knockdown also had a positive effect on reprogramming when c-Myc was included as a reprogramming factor, and reprogrammed colonies appeared at least a day earlier than under control conditions, indicating an improvement of the kinetics of the process (Fig 3B). In addition, overexpression of Jmjd2c, a H3K9me2/me3 demethylase38 important for the maintenance of the pluripotent state39 enhanced reprogramming about two–fold (Fig 3C, S3Aiii). Together, these results extend recent findings that the H3K9 methylation machinery impairs reprogramming to iPSCs and cell fusion-mediated gain of pluripotency9–11,37, and indicate that not only the H3K9 methylation enzymes but also members of the HP1 family act as critical barriers of reprogramming.

Figure 3. H3K9 methyltransferases, demethylases, and methyl binders are critical for reprogramming.

A) Depletion of H3K9 HMTases and Cbx3 enhances OSK reprogramming. Oct4-GFP reporter MEFs were infected with individual retroviruses expressing Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (OSK) and transfected with siRNAs targeting the indicated genes every three days starting on day seven post-infection. The number of GFP-positive colonies was determined on day 25 of reprogramming: i) for the knockdown of H3K9 methyltransferases Ehmt1, Ehmt2, and Setdb1; either singly or combined (indicated as 3XHMT); ii) for the knockdown of the heterochromatin protein 1 family members Cbx1 = HP1β, Cbx3 = HP1γ, or Cbx5 = HP1α. Data from two technical replicates (Rep1 and Rep2) from one out of three representative experiments are presented,.

B) Depletion of the H3K9 HMTases or Cbx3 enhances the efficiency and kinetics of OSCK reprogramming. Oct4-GFP reporter MEFs carrying a single, doxycycline (dox)- inducible polycistronic transgene encoding Oct4, Sox2, cMyc, and Klf4 (OSCK) were induced to reprogram by the addition of dox. On days 4, 6 and 10 post-induction, control siRNAs or the siRNA cocktail targeting 3XHMT or Cbx3 were transfected. To determine when reprogramming factor-independent GFP-positive colonies can be obtained, dox was withdrawn on days 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, respectively, and in all cases the number of GFP-positive colonies determined on day 15. Upon dox withdrawal, siRNA treatments were not continued.

C) Overexpression of the histone H3K9 demethylase Jmjd2c enhances reprogramming. Oct4-GFP reporter MEFs were reprogrammed with OSK as in (A) with the addition of Tomato (control) or Jmjd2c-expressing retroviruses. The number of GFP-positive colonies obtained was quantified on day 25. Data from two technical replicates (Rep1 and Rep 2) from one out of three representative experiments are presented.

To more directly address whether the reprogramming phenotypes observed above are linked to late reprogramming steps, we next tested whether pluripotency could be induced in pre-iPSCs by modulating HP1 or H3K9-HMTase levels. Knockdown of any of the three H3K9-HMTases or of any of the HP1 proteins in pre-iPSCs led to an increase in the number of Nanog-GFP-positive cells (Fig 4Ai). Among the HP1 family members the promoting effect was most pronounced for Cbx3 depletion (Fig 4Ai). Cbx3 knockdown enhanced the appearance of GFP-positive colonies with an ESC-like morphology to a similar extent as the knockdown of all three H3K9 HMTases together (Fig 4Aii, S3C). However, combined knockdown of Cbx3 and 3XHMT did not enhance colony formation further (Fig 4Aii), suggesting that at least some of the events regulated by Cbx3 and the HMTases during reprogramming are overlapping. GFP-positive colonies isolated from the Cbx3 siRNA-treated pre-iPSC cultures were expanded and displayed high expression levels of pluripotency markers such as Esrrb and Nanog (Fig 4B) and silencing of the retrovirally-encoded Oct4 and Sox2 transgenes (Fig S3D), satisfying hallmarks of pluripotency. The finding that decreasing levels of Cbx3 or H3K9 HMTases enhances iPSC formation from pre-iPSCs indicates that these proteins constitute a barrier to late reprogramming events.

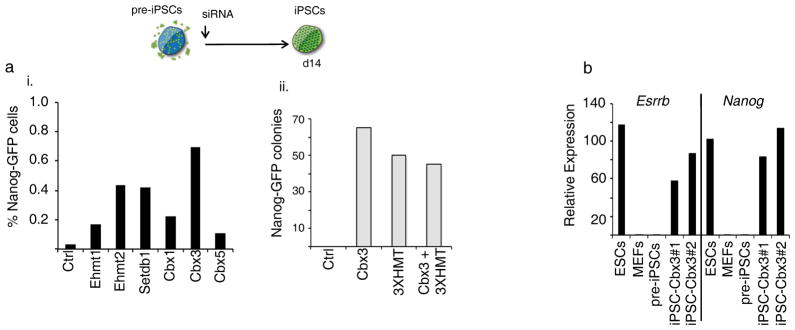

Figure 4. Interference with H3K9 methyltransferases or Cbx3 induces reprogramming in pre-iPSCs.

A) pre-iPSCs derived from Nanog-GFP reporter MEFs by retroviral expression of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and cMyc were transfected once with the indicated siRNAs. Reprogramming efficiency was determined by FACS analysis of GFP-positive cells on day 14 post siRNA transfection (i) or by counting the number of GFP-positive colonies on day 15 (ii). Note: colony numbers presented for Cbx3 and 3XHMT single knockdowns are the same as in Fig 6Diii, tetO-Nanog(−)/dox(−) condition). Repeated transfection of the siRNAs did not result in an increase in the number of GFP-positive cells.

B) Nanog-GFP-positive ESC-like colonies obtained upon Cbx3 knockdown in pre-iPSCs were expanded and two lines (iPSCs-Cbx3 #1 and #2) analyzed by qRT-PCR for transcript levels of the pluripotency genes Esrrb and Nanog. For comparison, ESCs, MEFs, and the starting pre-iPSCs, which were set to 1, are included in the analysis. Data presented is the mean of three technical replicates from one experiment.

Functions of H3K9-HMTases and Cbx3 during reprogramming

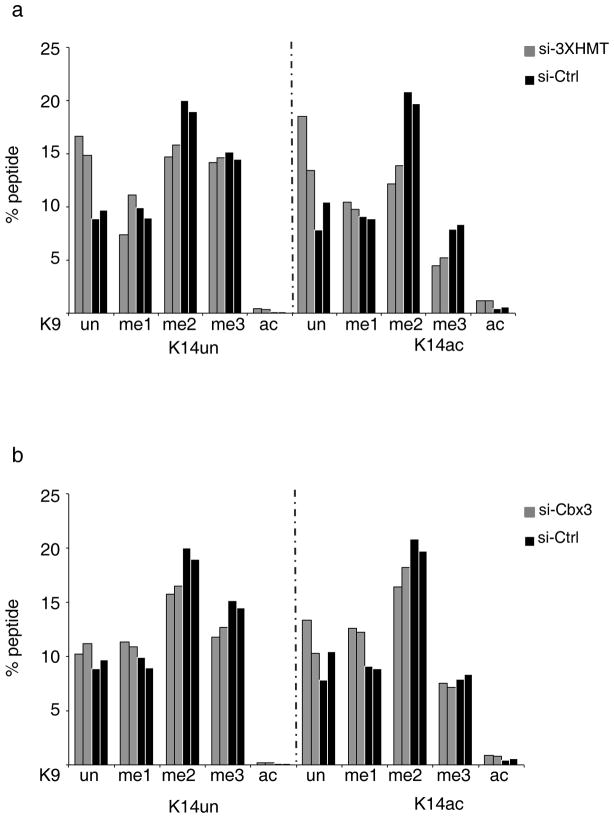

Next, we performed qMS analysis of histone PTMs in pre-iPSCs three days after initiation of 3XHMT or Cbx3 knockdown to gain insight into the molecular mechanisms of how these regulators promote late reprogramming events (MS data are summarized in Table S2). We reasoned that the analysis of histone PTMs shortly after initiation of knockdown but before Nanog-GFP expression was detectable (which first appeared seven days after the introduction of siRNAs (Fig S3C)), would reveal direct effects on global chromatin character due to depletion of the factors.

Upon 3XHMT knockdown, H3K9me2 levels decreased strongly, irrespective of the presence or absence of H3K14 acetylation on the same histone molecule, while H3K9me3 decreased only when K14 was acetylated as well (Fig 5A), indicating that the 3XHMT knockdown has specific effects in the context of combinatorial histone modifications. The decrease in H3K9me2/me3 was accompanied by a significant gain in the four unmethylated isoforms of the H3K9/K14 peptide: K9un/K14un, K9un/K14ac, K9ac/K14un, and K9ac/K14ac (Fig 5A). These changes in global chromatin state on the H3K9/K14 peptide trended towards the pattern seen in iPSCs (compare Fig 5A with Fig 1E). With the exception of a few low abundance histone PTMs, we detected no other dramatic changes in the histone PTM profile upon 3XHMT knockdown (Table S2), indicating that the PTM state of the H3K9 site does not immediately affect the majority of other histone PTMs. Upon Cbx3 knockdown most isoforms of the H3K9/K14 peptide did not change significantly in abundance, except those containing H3K9ac with and without K14ac (Fig 5B). We conclude that Ehmt1, Ehmt2, and Setdb1, but not Cbx3, directly contribute to the regulation of global H3K9me2/me3 levels in pre-iPSCs, and that a change in global H3K9me levels itself is not sufficient for the induction of pluripotency as additional time in culture is required for the efficient activation of the pluripotency network.

Figure 5. Depletion of the H3K9 HMTases but not of Cbx3 induces a change in PTMs on the histone H3 K9/K14 peptide in pre-iPSCs.

A) Percentages of the different isoforms of the H3 peptide containing the amino acids 9 to 17 (in which K9 and K14 are modified) in pre-iPSCs, three days post-transfection of control and 3XHMT siRNAs, determined by qMS. The data for two biological replicates are given. Source data are provided in Supp Table 2.

B) As in (A), except that the qMS approach was performed upon Cbx3 knockdown.

We also performed genome-wide transcriptional profiling on pre-iPSCs three days after transfection of the siRNAs, to further understand the role of the H3K9-HMTases and Cbx3 in reprogramming. Relatively few genes were differentially expressed in pre-iPSCs depleted for 3XHMT or Cbx3 (3XHMT siRNA: 222 genes 1.5-fold up and 261 genes 1.5-fold down; Cbx3 siRNA: 352 genes 1.5-fold up and 368 genes 1.5-fold down), and about a fifth of the up- and downregulated genes, respectively, changed their expression in the same direction between Cbx3 or 3XHMT knockdown (Fig 6A, Table S3). Further analysis demonstrated that the 3XHMT knockdown drives the gene expression program of pre-iPSCs more strongly towards the iPSCs expression pattern than Cbx3 depletion (Fig 6B). Accordingly, genes upregulated upon 3XHMT knockdown are more highly expressed in pluripotent cells than pre-iPSCs and downregulated genes are significantly lower expressed in pluripotent cells than pre-iPSCs (Fig 6C). For the Cbx3 knockdown this trend was only seen for the downregulated genes (Fig 6C). Interestingly, the 56 genes downregulated both in the 3XHMT and Cbx3 knockdown included Tgfβ2 and 49 of these genes were also expressed at lower levels in iPSCs than pre-iPSCs (Fig 6A), suggesting that the suppression of these genes may be important for the reprogramming enhancement observed upon these knockdowns. Consistent with this, TGFβ signaling is already known to inhibit reprogramming40,41. Inspecting the differentially expressed genes for other critical regulators of reprogramming, we found the pluripotency factor Nanog to be among the most upregulated genes in 3XHMT and Cbx3 depleted pre-iPSCs (Fig 6A–B; 7- and 10-fold up, respectively), which has been shown previously shown to be essential for the final reprogramming stage and to enhance reprogramming when overexpressed42,43. Additional pluripotency factors including Gdf3, Zfp42, Dppa4, and Lin28 were among the upregulated genes in pre-iPSCs specifically upon the 3xHMT knockdown (Fig 6A). We conclude that depletion of Cbx3 or 3XHMT yields partially overlapping gene expression changes in pre-iPSCs that converge on the induction of Nanog and the downregulation of genes that become reduced during the transition to the pluripotent state. Our finding the Cbx3 and 3XHMT knockdowns are not additive in their reprogramming enhancement (Fig 4B) is consistent with the idea that these knockdowns may enhance iPSC formation via overlapping transcriptional responses.

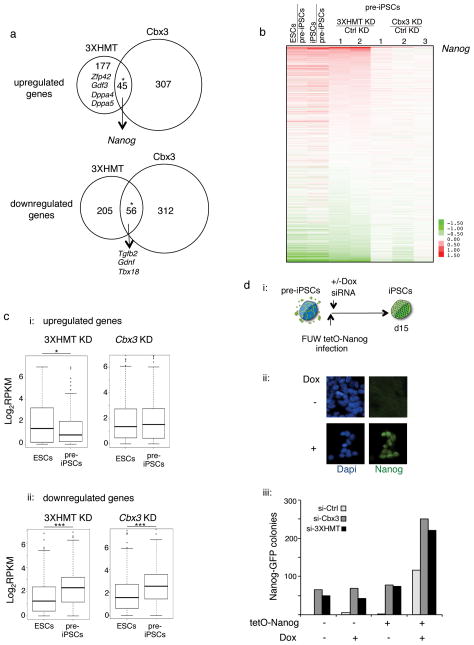

Figure 6. Depletion of H3K9 HMTases and Cbx3 promotes reprogramming of pre-iPSCs by inducing Nanog expression.

A) pre-iPSCs were transfected with control siRNAs or siRNAs targeting the three H3K9 HMTases (3XHMT) or Cbx3, and genome-wide expression was determined three days post-transfection. The venn diagrams show the overlap of genes that are up- or down- regulated in pre-iPSCs 3XHMT and Cbx3 knockdown, respectively, compared to control transfected cells. The asterisks denote significant overlap determined by the hypergeometric test, with a p-value of 5.19 × 10−31 and 5.84 × 10−39 for up- and downregulated genes, respectively. Interesting differentially expressed genes are indicated. Source data are provided in Supp Table 3.

B) Expression changes in pre-iPSCs upon 3XHMTase or Cbx3 knockdowns in relation to expression in pluripotent cells. The heatmap shows the differential expression (log2) for all genes (16333) between ESCs, iPSCs, two replicates of the 3XHMT knockdown in pre-iPSCs, and three replicates of Cbx3 knockdown in pre-iPSCs, each relative to control siRNA-transfected pre-iPSCs. Genes are ranked based on average expression differences caused by the 3XHMTase knockdown. Among the most upregulated genes is Nanog. Source data are provided in Supp Table 3.

C) (i) Box plot of the absolute gene expression levels in ESCs and pre-iPSCs for genes 1.5 fold up regulated upon 3XHMT knockdown (left) and Cbx3 knockdown (right) in pre-iPSCs; (ii) for genes 1.5-fold downregulated. Significance of difference in expression was determined by the Wilcoxon test, *p< 0.05, ***p<0.01. Source data are provided in Supp Table 3.

D) Combination of Nanog overexpression and 3XHMT or Cbx3 knockdowns in pre-iPSCs. (i) pre-iPSCs derived from Nanog-GFP reporter MEFs that carried the M2rtta (reverse tetracycline transactivator) were infected with a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible lentivirus encoding the Nanog cDNA and transfected once with siRNAs as indicated. (ii) Immunostaining for Nanog protein (green) of lentivirally infected cells in the presence or absence of dox. Dapi (blue) marks nuclei. (iii) Quantification of the number of GFP-positive colonies on day 15 post siRNA treatments for pre-iPSCs with and without the Nanog virus (tetO-Nanog), in the presence or absence of dox.

We therefore explored the contribution of Nanog upregulation to the reprogramming enhancement upon 3xHMT or Cbx3 knockdown. Since loss-of-function of Nanog prevents the establishment of iPSCs42, we did not test the consequence of 3XHMT or Cbx3 knockdown in pre-iPSCs lacking Nanog, but instead combined the knockdowns with Nanog overexpression. pre-iPSCs carrying a doxycycline-inducible Nanog transgene were transfected with siRNAs targeting 3XHMT or Cbx3 (Fig 6Di). Immunostaining indicated that over 90% of the infected cells expressed Nanog upon addition of doxycycline, and no expression in the absence of doxycycline (Fig 6Dii). By itself, overexpression of Nanog resulted in a strong induction of reprogrammed colonies similar to that seen upon 3XHMT or Cbx3 knockdown, indicating that high Nanog levels can efficiently convert our pre-iPSCs to iPSC (Fig 6Diii). Importantly, the 3XHMT or Cbx3 knockdowns only conferred a further two-fold enhancement in iPSC colony formation to Nanog expressing pre-iPSC (Fig 6Diii), consistent with the interpretation that Nanog upregulation is a key downstream event in the enhancement of reprogramming upon 3XHMT or Cbx3 depletion.

Nanog is a direct target of Cbx3 in pre-iPSCs

Our data predicted that Nanog is a target of Cbx3 and H3K9 methylation during reprogramming. To this end, we determined the genomic Cbx3 binding sites in pre-iPSCs and ESCs using ChIP-seq (Table S4). For each cell type, data from two biological replicates were merged for further analysis because they correlated well. We found that Cbx3 occupies regions upstream of the transcriptional start site (TSS) at the repressed Nanog locus in pre-iPSCs, overlapping with known upstream regulatory sites. In ESCs, where Nanog is strongly expressed, Cbx3 binding is absent from these regulatory regions (Fig 7A). Given that Nanog is the most upregulated gene upon Cbx3 knockdown in pre-iPSCs, these data indicate that Cbx3 directly represses Nanog in pre-iPSCs. Notably, the genomic region upstream of the TSS of Nanog is also enriched for H3K9me3 in pre-iPSCs, partially overlapping with Cbx3 occupancy (Fig S4A), in agreement with findings that showed H3K9 methylation at the Nanog promoter in differentiating ESCs39. Together, these findings indicate that Cbx3 functions together with H3K9me3 to repress Nanog in the reprogramming process, strengthening our conclusion that Nanog is an important downstream target on which Cbx3 and the regulation of H3K9 methylation converge during reprogramming.

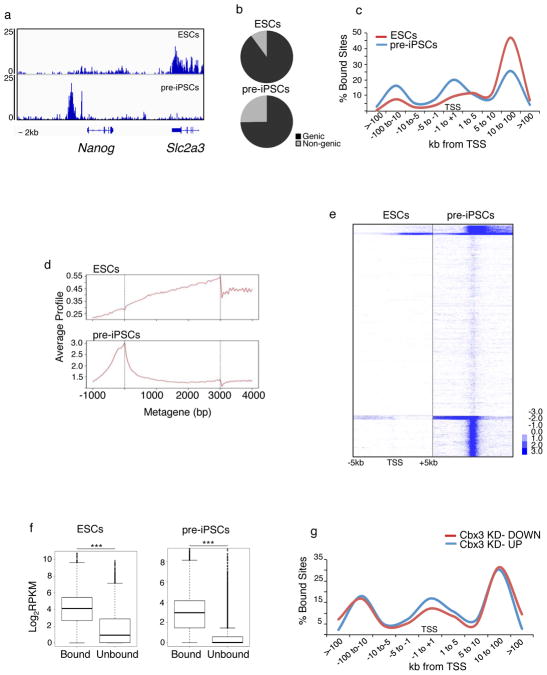

Figure 7. Cell type-specific occupancy of Cbx3 at TSS.

A) Snapshot of Cbx3 ChIP-seq data at the Nanog locus in pre-iPSCs and ESCs. Note that the neighboring gene Slc2a3 displays Cbx3 binding in the coding region in ESCs but not in pre-iPSCs.

B) Distribution of significant Cbx3 peaks between genic regions and non-genic regions, in both pre-iPSCs and ESCs, based on ChIP-seq. A Cbx3 peak was assigned to genic regions when it overlapped with a region from the TSS (transcriptional start site) to the 3′ end of the gene.

C) Frequency of sites bound significantly by Cbx3 with respect to the TSS is depicted for both pre-iPSCs and ESCs.

D) Average gene profiles for Cbx3 enrichment in pre-iPSCs and ESCs. Y-axis represents average signal (tag count) from 100bp windows.

E) Heatmap of Cbx3 enrichment for all genes from 5kb upstream to 5kb downstream of the TSS in pre-iPSCs and ESCs, divided into five groups based on K-means clustering. Blue denotes enrichment in a 100bp bin normalized to 1 million reads subtracted from normalized input values; values were log2 transformed.

F) Cbx3 occupied genes are more highly expressed than unbound genes. Box plot of absolute gene expression levels in ESCs and pre-iPSCs for Cbx3-bound and unbound genes. Log2 expression levels are based on reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) from RNA-seq data for these cell types. In this figure, genes were considered bound when Cbx3 was enriched anywhere in a region encompassing 10kb upstream of the TSS and the coding region. ***p<0.01, Wilcoxon test.

G) Distribution of Cbx3 binding sites with respect to distance to the TSS for genes that are up- and downregulated, respectively, in pre-iPSCs upon Cbx3 knockdown. All source for this figure data are provided in Supp Table 4.

Cbx3 predominantly binds highly expressed genes

Although the Nanog locus is bound by Cbx3 at upstream regulatory regions in pre-iPSCs, genome-wide Cbx3 predominantly occupies genic regions in both pre-iPSCs and ESCs (Fig 7B). The number of target genes with significant Cbx3 enrichment was dramatically lower in ESCs compared to pre-iPSCs (Fig S4B), and, within genes, Cbx3 displayed a distinct binding pattern between these two cell types (Fig 7C–E). Specifically, in ESCs, Cbx3 binding within genes increases from the TSS throughout the gene to the 3′ end, a pattern consistent with recent reports on Cbx3 binding in cancer cell lines34. Most of the target genes of Cbx3 in ESCs are also bound in pre-iPSCs (Fig S4B), typically associate with Cbx3 across the gene body (Fig 7E), and function in ribosome biogenesis, gene expression, and nucleosome assembly based on GO analysis. However, in pre-iPSCs Cbx3 additionally occupies the TSS regions of a large number of genes. Despite the different binding pattern, Cbx3-bound genes are on average significantly higher expressed than their unbound counterparts in both cell types (Fig 7F). Grouping Cbx3-bound genes in ESCs and pre-iPSCs into expression tiers also demonstrated that strong gene body and TSS occupancy of Cbx3 favors highly expressed genes (Fig S4C–D). Based on these findings and published reports34, we conclude that Cbx3 typically associates with gene bodies of highly transcribed genes. In addition our data uncover an unexpectedly strong association of Cbx3 with the TSS of expressed genes specifically in pre-iPSCs, which we also observed in early reprogramming intermediates.

Despite the widespread binding of Cbx3 to actively transcribed genes in pre-iPSCs only a relatively small number of genes were differentially expressed upon Cbx3 depletion (Fig 6A). A greater proportion of downregulated than upregulated genes was directly bound by Cbx3 (256 and 196 genes, respectively). Therefore, Cbx3 can both positively and negatively affect its target genes, likely depending on the exact context of its binding. Consistent with this, upregulated genes have slightly more pronounced binding of Cbx3 at the TSS and upstream promoter region than downregulated genes (Fig 7G).

Cbx3 associates with the transcriptional initiation complexes in a cell type- and activator-dependent manner

Exploring the nature of the TSS enrichment in pre-iPSCs further, we found that the Mediator co-activator complex, which is part of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex (PIC)44, mimics the Cbx3 binding pattern at the TSS (Fig 8A). The association of Cbx3 with the TSS in pre-iPSCs but not ESCs suggested that Cbx3 and Mediator might interact in differentiated cells but not in pluripotent cells. To test this hypothesis, we immunoprecipitated the Mediator complex from ESCs and ESC-derived differentiated cells, taking advantage of a tetracycline-inducible transgene encoding a Flag-tagged subunit of Mediator (Flag-Med29), and determined whether Cbx3 could be detected in the immunoprecipitate (Fig 8B). The results showed that Med29 can co-precipitate Cbx3 much more strongly in differentiated cells than ESCs, indicating that the interaction of Mediator and Cbx3 is regulated in a cell type-dependent fashion. We also studied the recruitment of Cbx3 to the PIC in vitro, employing nuclear extract, the model transcriptional activator GAL4-VP16, and an immobilized GAL4-responsive DNA template. The results show that Cbx3 is recruited from nuclear extracts to the chromatin template, but only upon activator addition, similar to Mediator (Fig 8C). These data suggest that Cbx3 is recruited to the TSS of transcribed genes in an activator-dependent manner by associating with the PIC, and that specifically in differentiated cells. It is conceivable that differential posttranslational modifications, the presence of different splice forms of Mediator subunits, or a different chromatin composition at the TSS in ESCs versus differentiated cells45 could explain the cell type specificity of the Cbx3 association with the PIC at the TSS. Since the association of Cbx3 with the TSS in pre-iPSCs appears to occur independently of H3K9me3 (Fig S4E), the interaction with PIC components is likely responsible for the Cbx3 recruitment to the TSS. Taken together, our findings reveal a function of Cbx3 in the context of transcriptional regulation at the TSS that appears to be specific for differentiated cells and reprogramming intermediates, as Cbx3 occupancy at the TSS is lacking in pluripotent cells.

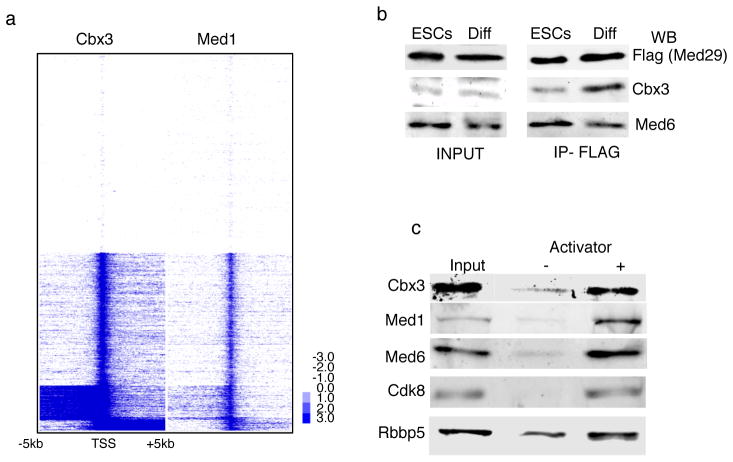

Figure 8. Cbx3 association with mediator components.

A) Cbx3 co-localizes with Mediator at the TSS. Heatmap of Cbx3 and Mediator (Med1 subunit) enrichment in pre-iPSCs for all genes from 5kb upstream to 5kb downstream of the TSS, divided into five groups based on K-means co-clustering, based on ChIP-seq. Blue denotes enrichment in a 100bp bin normalized to 1 million reads subtracted from normalized input values; values were log2 transformed.

B) Cbx3 precipitates more efficiently with Med29 in differentiated cells than ESCs. Immunoprecipitates (IP) of Flag-Med29 from ESCs and differentiated cells (neural precursors differentiated from ESCs) were probed with antibodies to Cbx3 or Med6 by western blotting (WB). 1% of input and 5% of IP are shown. Equal amounts of Cbx3 and Med6 are present in inputs from both cell types.. Cbx3 but not the control Med26 is enriched in the Med29 IP in NPCs.

C) Cbx3 is recruited to the PIC in an activator-dependent manner. Transcriptional preinitiation complexes (PICs) were formed in the presence and absence of a model activator GAL4-VP16 in nuclear extract. Note that Cbx3 was only incorporated in the PIC when the VP16 transcriptional activator was present, similar to Mediator (subunits Med1, Med6, Cdk8) and the Mll complex component Rbbp5. Uncropped scans are available in Figure Supp Fig 5.

Discussion

In summary, our qMS approach has yielded a quantitative and comprehensive analysis of global histone PTMs in differentiated and pluripotent cells, and during reprogramming. Our data indicate that the global histone PTM profile changes late in the reprogramming process, which may be associated with the efficient activation of the pluripotency network, major replication timing changes within early embryonic genes46, and the reactivation of the inactive X chromosome47. We speculate that global chromatin and replication-timing reorganization are key aspects of the final reprogramming stage, required for establishment of the self-sustaining pluripotency network.

The quantitative repository of global histone modification changes generated here can be used as a starting point for further dissection of reprogramming roadblocks and epigenetic differences between pluripotent and differentiated cells. Based on this idea, we determined the role of H3K9 methylation during reprogramming by analyzing proteins involved in the regulation of this histone modification. Despite the fact that our work reveals various distinct functions of Cbx3 and the methyltransferases Ehmt1, Ehmt2, and Setdb1 during reprogramming, reflected in the differential control of global H3K9 methylation levels or association with the basic transcriptional machinery, the removal of the three H3K9-HMTases or Cbx3 elicited partially overlapping transcriptional responses including the reactivation of the silent Nanog locus. Our data suggest that these common expression changes cause reprogramming enhancement.

By examining the role of Cbx3, we found a remarkable switch in the location of Cbx3 between pluripotent and non-pluripotent cells, and a physical association of Cbx3 with the Mediator complex that could be responsible for targeting Cbx3 to the TSS in non-pluripotent cells. Since only a small subset of its target genes become differentially expressed in pre-iPSCs upon knockdown of Cbx3, we speculate that Cbx3 binding at the TSS mediates more subtle functions and acts perhaps to maintain or restore nucleosome density near the promoter during transcription to protect the transcribed DNA. Alternatively, different HP1 family members may also act at the TSS and mask the effects of Cbx3. Consistent with this, another HP1 family member, HP1α, has been shown to localize to the TSS of transcribed genes in Drosophila48, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role of HP1 family members in the PIC. Understanding the mechanistic basis for the switch in Cbx3 localization between pluripotent and non-pluripotent cells will reveal further insight into the nature of the pluripotent state.

Methods

Histone sample preparation for quantitative mass spectrometry (qMS)

Cell pellets were lysed, nuclei isolated, and histones extracted as previously described16. For each sample, approximately 100 μg of extracted histones were re-suspended in 30μL of 100mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0. Chemical propionylation derivatization, digestion and desalting of histones was performed as described25, except that histones were digested for 6 hours. We performed both label free and isotopically labeled peptide relative quantification. For isotopically labeled peptide comparative MS analysis, d0- and d10-propionic anhydride were used as previously described15. All proteomics data are available at the Stem Cell Omics Repository at http://scor.chem.wisc.edu/.

Mass spectrometry and data analysis

Samples were analyzed by LC-MS and MS/MS as described15. In brief, digested samples were loaded by an Eksigent AS2 autosampler onto 75 μm ID fused silica capillary columns packed with 12 cm of C18-reversed phase resin (Magic C18, 5 μm particles, Michrom BioResources), constructed with an electrospray ionization tip. Peptides were separated by nanoflowLC and introduced into a hybrid linear quadrupole ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoElectron, San Jose, CA), and resolved with a gradient from 5 to 35% Buffer B in a 110-min gradient (Buffer A: 0.1 M acetic acid, Buffer B: 70% acetonitrile in 0.1 M acetic acid) with a flow rate of 150 nl/min on an Agilent 1200 binary HPLC system. The Orbitrap was operated in data-dependent mode essentially as previously described15. Relative abundances of peptide species were calculated by chromatographic peak integration of full MS scans using an in-house developed computer program. Peptide identity and modifications were verified by manual inspection of MS/MS spectra. Cluster 3.0 was used to create hierarchical clustering of ratio data and Java Treeview for visualization of the output.

Cell lines used for analysis of histone PTMs

The following cell lines were used for histone PTM qMS analysis in Figures 1 and 2: a female iPSC (2D4) line generated by retroviral expression of Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf413; a male iPSC line (C3) obtained upon retroviral expression of Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (i.e. in the absence of cMyc); a female pre-iPSC line (1A2)13 and a male pre-iPSC line (12-1) both obtained upon retroviral expression of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and cMyc in Nanog-GFP reporter MEFs. In addition, we used the male ESC line V6.5, and male and female wild-type MEFs from d13.5 embryos. ESCs, iPSCs, and pre-iPSCs were grown in standard mouse ESC media and MEFs in the same media lacking LIF.

Reprogramming experiments

Reprogramming experiments were carried out from Oct4-GFP49 or Nanog GFP13 reporter MEFs using pMX retroviruses encoding Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 as described previously27 and conducted in media containing 15% serum (FBS). MEFs containing a single polycistronic, tet-inducible cassette carrying the four reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and cMyc in the Col1A locus, the tet-transactivator M2rtTA in the R26 locus, and the Oct4-GFP reporter, were generated as described50, and induced to reprogram with 2ug/ml doxycycline. Reprogramming was scored by counting the number of GFP-positive ESCs-like colonies at indicated days. All reprogramming experiments from fibroblasts and pre-iPSC experiments were done in biological triplicates, and for each figure, error bars represent standard deviation from two technical replicates of a representative experiment. For pre-iPSC experiments, reprogramming to iPSCs upon siRNA knockdown was assessed by counting Nanog-GFP-positive colonies or quantifying GFP-positive cells by FACS at indicated days. For FACS analysis, 12-1 pre-iPSCs were harvested with trypsin, passed through a 40um cell strainer to obtain single-cell suspensions and analyzed on a LSR cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar). Fuw-tetO-loxp-mNANOG was created by ligation-independent cloning (Infusion, Clontech Mountain View, CA) by digesting the vector Fuw-tetO-loxp-hKLF4 (Addgene 20727) with EcoRI and PCR-amplifying mouse Nanog from pMX-mNANOG (Addgene 13354). The vector was cotransfected with pCMV-delta8.9 and pCAGS-VSVg (Generous gift from Dr. Donald Kohn, UCLA) into 293T cells and viral conditioned media harvested 48 hours post transfection in serum free media (Ultraculture, Lonza). Expression was confirmed by immunostaining. For over expression, Jmjd2c was cloned from a PCR product using gene specific primers (Forward: ATGCGAATTCATGGAGGTGGTGGAGGTG, Reverse: ATGCGCGGCCGCCTACTGTCTCTTCTGACA) into the EcoRI and NotI sites of pMX vector. Expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR performed with gene specific primers RNA three days after transduction (For-GGCCATGGAAGTAACCTTGA, Rev-GAGGCTTACCAAGTGGATGG).

siRNA transfection

Sets of four different siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon and transfected using lipofectamine–RNAi max (Life technologies) according to manufacturers instructions. Of the set of four siRNAs, the one producing the most efficient knockdown was used in reprogramming experiments at a final concentration of 20uM: Cbx1- MU-060281-01 #2, Cbx3 - MU-044218-01 #2, Cbx5 - MU-040799-01 #2, Setdb1 - MU-040815-01 #4, Ehmt1 - LU-059041-01- #3, Ehmt2 - MU053728-00- #3. For control siRNA treatments, we used the non-targeting Luciferase control- D-001210-02. The timing of siRNA transfections is indicated in each figure. For pre-iPSCs reprogramming experiments, reverse transfection of siRNAs was performed once, on 200,000 cells of the 12-1 pre-iPSC line, plated on gelatin. To test knockdown efficiency during reprogramming, RNA was harvested three days after the first transfection and on day 22, i.e. 3 days after the last transfection, and qRT-PCR was performed with gene-specific primers listed below.

| For=Forward, Rev=Reverse | Cbx1-For:GGAGAGGAAAGCAAACCAAA, |

| Rev:AGCTCCAATAATCCGCTCTG; | Cbx3-For:CTGGACCGTCGTGTAGTGAA, |

| Rev:AAATTTTCTTCTGGTTCCCAG; | Cbx5-For:GGAAATCCAGTTTCTCCAACA, |

| Rev:GCTCCGATGATCTTTTCTGG; | Ehmt1-For:TTGCTGCATGAAAACTGAGC, |

| Rev:CAAGACCCATTTGTTTCTCCA; | Ehmt2-For:CATGTCCAAACCTAGCAACG, |

| Rev:CCAGAGTTCAGCTTCCTCCTT; | Setdb1-For:GCAACTCAGAACCCGTCCTA, |

| Rev:ATAGGCTGTAGGGGCTCCAT. |

Expression Analysis and Data Processing

To determine the transcriptional changes upon 3XHMT and Cbx3 knockdown in pre-iPSCs, total RNA was extracted from the pre-iPSC line 12-1 three days after the cells were subjected to transfection with control siRNAs (in biological triplicates), si-Cbx3 (in biological triplicates), or a pool of si-Ehmt1, si-Ehmt2, and si-Setdb1 (in biological duplicates), and analyzed on an Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array at the UCLA Clinical Microarray core facility. Quantile normalization was performed using the Affymetrix package (affy) from Bioconductor. To convert probe data into gene expression data, probes ending in “_at” and “_a_at” were averaged for each gene. Data at the probe level were normalized with previously published data for ESCs, iPSCs, and MEFs27. Data are deposited in the GEO database under GSE44084.

RNA-seq was performed using 4 ug of mRNA as starting material from ESCs and pre-IPSCs, using standard illumina RNA-seq library construction protocols. Briefly polyadenylated RNA was purified by two rounds of oligo-dT bead selection followed by divalent cation fragmentation under elevated temperature. Following cDNA synthesis with random hexamers, the double-stranded products were end repaired, a single “A” base was added, and Illumina adaptors were ligated onto the cDNA products. Ligation products with an average size of 300 bp were purified by means of agarose gel electrophoresis. The adaptor ligated single-stranded cDNA was then amplified with 10 cycles of PCR. RNA-Seq libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2000. The RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon per million) was then computed for each gene.

Med29 Immunoprecipitation and PIC capture assay

ESCs expressing FLAG-Med29 were obtained by targeting the 3xFlag-Med29 under control of a tet-inducible promoter into the ColA1 locus51 in V6.5 ESCs carrying the M2rtTA in the R26 locus. Targeting was confirmed by Southern Blotting. Neural precursors were differentiated from these cells after suspension culture of embryoid bodies for four days, and selection in ITSF media for six days52. Nuclear extract of ESCs and neural precursors were prepared and the purification of protein complexes containing Med29 was performed as in previously described53. PIC assembly was performed from HeLa nuclear extract using the immobilized G5E4T and analyzed by Western blotting as described54. All primary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution and secondary antibodies at 1:10000 dilution- anti-FLAG from Sigma (F-1804), anti-Med6 (sc-9434), anti-Cbx3 from Millipore (05690), from SantaCruz anti-Med1 (sc-8998), anti-RBBP5 (Bethyl-A300-109), anti-Cdk8 (sc-1521).

ChIP-Seq and ChIP-chip analysis

12-1 pre-iPSCs or V6.5 ESCs were chemically cross-linked by the addition of formaldehyde to 1% final concentration for 10 minutes at room temperature, and quenched with 0.125 M final concentration glycine. Cells were washed twice in PBS, re-suspended in sonication buffer (50mM Hepes, 140mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), and sonicated with a Diagenode Bioruptor. Cell extracts were incubated with an antibody against Cbx3 (Millipore, 05-690; clone 42s2) or Med1 (sc-8998) overnight at 4°C and immunoprecipitates collected with magnetic beads.

Beads were washed twice with RIPA buffer, low salt buffer (20mM Tris pH 8.1, 150mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS), high salt buffer (20mM Tris pH 8.1, 500mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS), LiCl buffer (10mM Tris pH 8.1, 250mM LiCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40), and with 1xTE. Reverse cross-linking occurred overnight at 65°C with 1% SDS and proteinase K. Illumina/Solexa sequence preparation, sequencing, and quality control were performed according to Illumina protocols, with the minor modification of limiting the PCR amplification step to 10 cycles.

Reads were mapped to mm9 genome using the Bowtie software and only those reads that aligned to a unique position with no more than two sequence mismatches were retained for further analysis. Significant binding events were called as peaks using MACS2.0 using an FDR of 0.05 and the –broadpeaks setting that allows calling of broader domains. Location analysis of called peaks was performed using the Sole-search tool. Visualization of the ChIP-seq signal around the TSS is provided by heatmaps generated using Java Treeview. Briefly, enrichment is displayed after normalization to 1 million reads and subtraction of normalized input values per 100bp window. Data are deposited in the GEO database under GSE44242.

For ChIP-chip of H3K18me1 and H3K79me2, chromatin fragments (500ug) from V6.5 ESCs were enriched with specific antibodies, labeled and hybridized, along with corresponding input fragments, to an Agilent promoter microarray (Agilent-G4490) that contains the promoter regions of 18,300 annotated mouse genes, encompassing regions 5.5kb upstream to 2.5 kb downstream of the respective transcription start sites (TSS) as described27. The H3K18me1 antibody was generated by N. Mishra, and the H3K79me2 antibody was kindly provided by Michael Grunstein at UCLA. The ChIP-chip data sets for H3K4me3 and RNA PolII data have been previously published5,27. Hybridization onto the arrays, washing, and scanning were done according to manufacturer’s protocols. Average probe signals were extracted in a 500bp window-step-wise manner as described previously27.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Vincent Pasque for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Michael Grunstein (UCLA) for providing antibodies. KP is supported by the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA, NIH (DP2OD001686 and P01 GM099134) and CIRM (RN1-00564); RS was supported by the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, CC by a Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research Grant (10040), GB by the Whitcome Pre-doctoral Training Program, BAG by a National Science Foundation Early Faculty CAREER award and an NIH Innovator award (DP2OD007447), and MC by the NIH (GM074701).

Footnotes

Author contributions: R.S., K.P., and B.A.G. planned the project. R.S. and K.P. wrote the manuscript. The following performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data: R.S., C.C., G.B., R.M., S.P. under K.P.’s supervision, M.G-C. under B.A.G’s supervision, C.H. under M.C.’s supervision, and D.L. under M.P.’s supervision. N.M. generated H3K18me1 antibody.

References

- 1.Plath K, Lowry WE. Progress in understanding reprogramming to the induced pluripotent state. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrg2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikkelsen TS, et al. Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature. 2008;454:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nature07056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ang YS, et al. Wdr5 mediates self-renewal and reprogramming via the embryonic stem cell core transcriptional network. Cell. 2011;145:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaspar-Maia A, et al. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:863–868. doi: 10.1038/nature08212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singhal N, et al. Chromatin-Remodeling Components of the BAF Complex Facilitate Reprogramming. Cell. 2010;141:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang T, et al. The histone demethylases Jhdm1a/1b enhance somatic cell reprogramming in a vitamin-C-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang G, He J, Zhang Y. Kdm2b promotes induced pluripotent stem cell generation by facilitating gene activation early in reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:457–466. doi: 10.1038/ncb2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onder TT, et al. Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature. 2012;483:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, et al. H3K9 methylation is a barrier during somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs. Nat Gen. 2013;45:34–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soufi A, Donahue G, Zaret KS. Facilitators and Impediments of the Pluripotency Reprogramming Factors’ Initial Engagement with the Genome. Cell. 2012;151:994–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattout A, Biran A, Meshorer E. Global epigenetic changes during somatic cell reprogramming to iPS cells. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;3:341–350. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maherali N, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin MH, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia BA, et al. Chemical derivatization of histones for facilitated analysis by mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:933–938. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plazas-Mayorca MD, et al. One-Pot Shotgun Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Characterization of Histones. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5367–5374. doi: 10.1021/pr900777e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, et al. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karmodiya K, et al. H3K9 and H3K14 acetylation co-occur at many gene regulatory elements, while H3K14ac marks a subset of inactive inducible promoters in mouse embryonic stem cells. BMC Genomics. 2013;13:424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rada-Iglesias A, et al. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature. 2011;470:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature09692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie W, et al. Histone h3 lysine 56 acetylation is linked to the core transcriptional network in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 2009;33:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, et al. Histone H3 Lysine 14 Acetylation Is Required for Activation of a DNA Damage Checkpoint in Fission Yeast. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:4386–4393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.329417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meshorer E, et al. Hyperdynamic Plasticity of Chromatin Proteins in Pluripotent Embryonic Stem Cells. Developmental Cell. 2006;10:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steger DJ, et al. DOT1L/KMT4 Recruitment and H3K79 Methylation Are Ubiquitously Coupled with Gene Transcription in Mammalian Cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:2825–2839. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02076-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogan NJ, et al. Methylation of Histone H3 by Set2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Is Linked to Transcriptional Elongation by RNA Polymerase II. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23:4207–4218. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4207-4218.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zee BM, et al. In Vivo Residue-specific Histone Methylation Dynamics. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:3341–3350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Efroni S, et al. Global Transcription in Pluripotent Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sridharan R, et al. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell. 2009;136:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golipour A, et al. A Late Transition in Somatic Cell Reprogramming Requires Regulators Distinct from the Pluripotency Network. Stem Cell. 2012;11:769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polo JM, et al. A Molecular Roadmap of Reprogramming Somatic Cells into iPS Cells. Cell. 2012;151:1617–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva J, et al. Promotion of Reprogramming to Ground State Pluripotency by Signal Inhibition. Plos Biol. 2008;6:e253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bannister AJ, et al. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–124. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410:116–120. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon SH, Workman JL. The changing faces of HP1: From heterochromatin formation and gene silencing to euchromatic gene expression. Bioessays. 2011;33:280–289. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smallwood A, et al. CBX3 regulates efficient RNA processing genome-wide. Genome Research. 2012;22:1426–1436. doi: 10.1101/gr.124818.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilodeau S, Kagey MH, Frampton GM, Rahl PB, Young RA. SetDB1 contributes to repression of genes encoding developmental regulators and maintenance of ES cell state. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2484–2489. doi: 10.1101/gad.1837309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan P, et al. Eset partners with Oct4 to restrict extraembryonic trophoblast lineage potential in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2507–2520. doi: 10.1101/gad.1831909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma DK, Chiang CHJ, Ponnusamy K, Ming GL, Song H. G9a and Jhdm2a Regulate Embryonic Stem Cell Fusion-Induced Reprogramming of Adult Neural Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2131–2141. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloos PAC, et al. The putative oncogene GASC1 demethylates tri- and dimethylated lysine 9 on histone H3. Nature. 2006;442:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature04837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, George J, Ng HH. Jmjd1a and Jmjd2c histone H3 Lys 9 demethylases regulate self-renewal in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2545–2557. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li R, et al. A Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition Initiates and Is Required for the Nuclear Reprogramming of Mouse Fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ichida JK, et al. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of Tgf-β Signaling Replaces Sox2 in Reprogramming by Inducing Nanog. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva J, et al. Nanog is the gateway to the pluripotent ground state. Cell. 2009;138:722–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanna J, et al. Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature. 2009;462:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nature08592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas MC, Chiang CM. The General Transcription Machinery and General Cofactors. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2006;41:105–178. doi: 10.1080/10409230600648736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffiths DS, et al. LIF-independent JAK signalling to chromatin in embryonic stem cells uncovered from an adult stem cell disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;13:13–21. doi: 10.1038/ncb2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hiratani I, et al. Genome-wide dynamics of replication timing revealed by in vitro models of mouse embryogenesis. Genome Research. 2010;20:155–169. doi: 10.1101/gr.099796.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault DT, Hochedlinger K. Defining Molecular Cornerstones during Fibroblast to iPS Cell Reprogramming in Mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin H, Sweeney S, Raha D, Snyder M, Lin H. A High-Resolution Whole-Genome Map of Key Chromatin Modifications in the Adult Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szabó PE, Hübner K, Schöler H, Mann JR. Allele-specific expression of imprinted genes in mouse migratory primordial germ cells. Mech Dev. 2002;115:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Borkent M, Hochedlinger K. A reprogrammable mouse strain from gene-targeted embryonic stem cells. Nat Meth. 2009;7:53–55. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beard C, Hochedlinger K, Plath K, Wutz A, Jaenisch R. Efficient method to generate single-copy transgenic mice by site-specific integration in embryonic stem cells. Genesis. 2006;44:23–28. doi: 10.1002/gene.20180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okabe S, Forsberg-Nilsson K, Spiro AC, Segal M, McKay RD. Development of neuronal precursor cells and functional postmitotic neurons from embryonic stem cells in vitro. Mech Dev. 1996;59:89–102. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen XF, et al. Mediator and SAGA Have Distinct Roles in Pol II Preinitiation Complex Assembly and Function. Cell Reports. 2012;2:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin JJ, et al. Mediator coordinates PIC assembly with recruitment of CHD1. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2198–2209. doi: 10.1101/gad.17554711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.