Abstract

To study the mechanisms involved in membrane fusion, we visualized the fusion process of giant liposomes in real time by optical dark-field microscopy. To induce membrane fusion, we used (i) influenza hemagglutinin peptide (HA), a 20-aa peptide derived from the N-terminal fusion peptide region of the HA2 subunit, and (ii) two synthetic analogue peptides of HA, a negatively (E5) and positively (K5) charged analogue. We were able to visualize membrane fusion caused by E5 or by K5 alone, as well as by the mixture of these two peptides. The HA peptide however, did not induce membrane fusion, even at an acidic pH, which has been described as the optimal condition for the fusion of large unilamellar vesicles. Surprisingly, before membrane fusion, the shrinkage of liposomes was always observed. Our results suggest that a perturbation of lipid bilayers, which probably resulted from alterations in the bending folds of membranes, is a critical factor in fusion efficiency.

Keywords: giant liposome, influenza hemagglutinin, optical microscopy, direct observation

Membrane fusion plays an essential role in cellular activities such as exocytosis, endocytosis, and vesicle transport of various cellular organelles. Also, it is an essential step of infection by enveloped viruses. Because the fusion of biological membranes is so important, studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion have been performed. Many of those studies focused on membrane fusion driven by fusogenic peptides, for example, those derived from influenza hemagglutinin. Those studies demonstrated that there are several critical steps required for membrane fusion (1–4). To characterize membrane fusion, resonance-energy transfer and fluorescence-quenching methods have been commonly used (5, 6). The resonance-energy transfer method monitors the mixing of membrane lipids that occurs during fusion, whereas the fluorescence-quenching method monitors the mixing of vesicular contents. Light scattering to detect fusion kinetics, or electron microscopy to visualize the fusion process, has also been commonly used. Electron microscopy can provide snapshots of the changing membrane structures in detail (7), but it is not suitable for studying the time-dependent transition of the three-dimensional membrane morphology.

For understanding the fusion mechanism, the real-time visualization of individual fusion processes is indispensable (6, 8). We used giant (1–20-μm diameter) liposomes as a model for biological membrane vesicles, and we monitored their fusion process in real time by using optical high-intensity dark-field microscopy (8). Giant liposomes can be visualized by several optical microscopic methods (9–11). However, we have used dark-field microscopy because it gives the best high-contrast images of giant liposomes compared with other methods (8, 12–15).

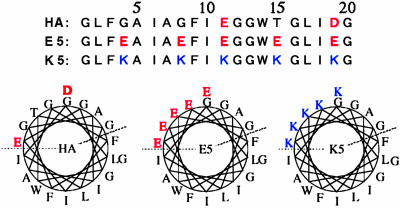

To induce membrane fusion, we used three different peptides: HA, E5, and K5. HA is a 20-aa peptide derived from the N-terminal fusion peptide region of the influenza hemagglutinin HA2 subunit, whereas E5 and K5 are negatively and positively charged analogs of HA, respectively. It has been thought that these peptides form an amphiphilic helical conformation (Fig. 1). As their electric charges are neutralized, they penetrate into the lipid bilayer and probably destabilize that bilayer structure to induce fusion (16–20). It has been demonstrated that fusion between large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) made of phosphatidylcholine (PC) was induced by either the HA or the E5 peptide alone at acidic pH, by the mixture of E5 and K5 peptides at neutral pH, or by K5 alone at alkaline pH. It has also been reported that the interaction between these peptides and the membrane strongly depends on the peptide concentration, the ionic strength, and the pH. These results, however, were obtained by using internal-content mixing or other common assay methods, as described above (16–18). Therefore, in this study we monitored individual fusion events in real time by using giant liposomes made of PC or a mixture of PC and phosphatidylglycerol (PG). Also, we studied the effects of the concentration of peptides and salt, pH, and lipid composition of the liposomal membrane on fusion efficiency.

Fig. 1.

Peptides derived from the fusion peptide region of influenza hemagglutinin (HA). Amino acid sequences and proposed helical-foil structures are shown.

In this study, the E5 and the K5 peptides were found to possess a capability to cause giant liposomes to shrink. Only the shrunken liposomes fused with each other. The HA peptide itself, however, showed no fusogenic activity, even at acidic pH, which has been described as the optimum condition.

Methods

Phospholipids and Peptides. PC and PG isolated from egg yolk were purchased from Sigma. Peptides (HA, E5, and K5) were synthesized as described (16, 17, 21). E5 and K5 were dissolved in Milli-Q water (Nihon Millipore, Yonezawa, Japan) at a concentration of 2 mM, whereas HA was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 10 mM. Each sample was stored at -20°C. A zwitterionic surfactant, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), was purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka).

Preparation and Observation of Giant Liposomes. Giant liposomes were prepared as described (13–15). A total of 200 μg of PC, or a 1:1 mixture of PC and PG (mol/mol), was dissolved in 98:2 chloroform/methanol (vol/vol). The organic solvent was evaporated under a flow of nitrogen gas, and the lipids were further dried in vacuo for at least 90 min. We then added 1 ml of buffer, containing 10 mM Mes·NaOH and Tris·HCl or Hepes·NaOH (pH 7.0) and 0–100 mM NaCl, to the dried lipid films at 25°C. The lipid films started swelling immediately to form liposomes, and the swelling was facilitated by agitating the test tubes occasionally by hand. Liposomes were observed at 25°C by using a dark-field BHF microscope (Olympus) as described (12–15). Images were recorded by using an SIT video camera (C-2400–08; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan), further processed with ip-lab software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA), and analyzed with image (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) and photoshop software (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). Samples were also observed by using a JEM-1200 EX II electron microscope (JEOL) after negative staining to analyze the structures of liposomal membranes.

Solution Mixing in a Mixing Chamber. To make a concentration or pH gradient of each peptide that was suitable for examination in a microscope, we used a mixing chamber made of a glass slide and a coverslip, which were firmly fixed together by spacers (22). This chamber has three open channels. To make a concentration gradient of a peptide in a liposome solution, a drop of the peptide solution was placed in one open channel of the chamber and the liposome solution was placed in another channel. These two solutions seeped into the chamber, with air coming out through the third channel. The solutions attached gently and mixed with each other, thereby generating a concentration gradient by diffusion. Slowly moving liposomes were followed in the microscope, and their behavior at various concentrations of the added peptide was monitored. A pH gradient in the chamber was made by using the same method. The pH in local areas was estimated by using tiny pH indicator strips (Merck).

Results

Shrinkage and Fusion of Liposomes Are Induced by a Mixture of K5 and E5. It has been shown that a mixture of K5 and E5 induces the fusion of PC-LUVs (LUVs made of PC) at neutral pH (17). Those results, however, were obtained by using indirect methods. To confirm those results, we tried to visualize this fusion process with our method. We mixed K5 with a mixture of E5 and PC liposomes (giant liposomes made of PC) in 10 mM Hepes·NaOH (pH 7.0). Fusion events that occurred in the mixing chamber were then observed and recorded by using a dark-field microscope.

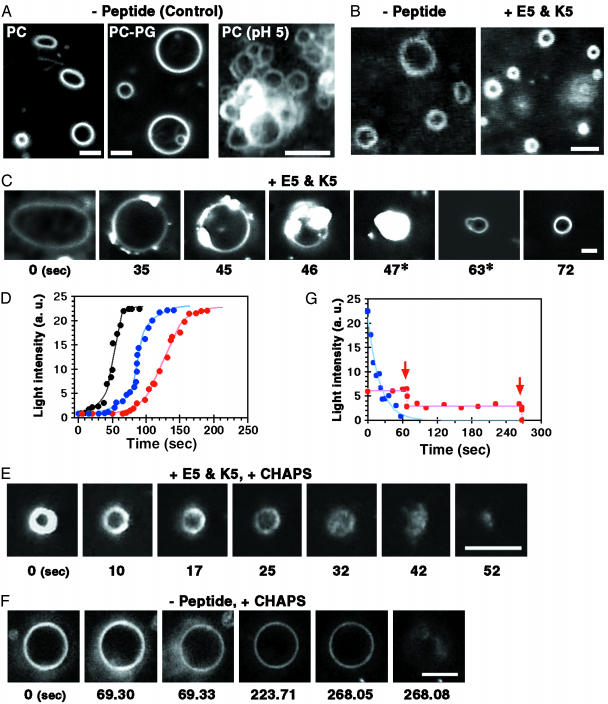

Giant liposomes have spherical or elliptical shapes (Fig. 2A). Without added peptides, giant liposomes did not show any morphological change, as determined at various combinations of lipid composition, pH, and salt concentrations, as well as at different osmotic conditions. For example, the morphologies did not change at pH 3–10 or in the buffer containing 100 mM sucrose or 0.2 mM nonfusogenic peptide (such as HA, as described below), except such that PC liposomes aggregated at acidic pH. When the pH was lowered to ≈5, PC liposomes became spherical, stabilized in shape, and then adhered to each other, forming huge aggregates (Fig. 2 A Right). As the pH was lowered further, these aggregates dissociated into individual liposomes again.

Fig. 2.

Shrinkage of giant liposomes. (A) Dark-field images of PC (Left) and PC-PG (Middle) liposomes in the absence of fusogenic peptides (1 mM lipids/10 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.0). These giant liposomes did not show any morphological change, even after the buffer (10 mM Mes·NaOH or Tris·HCl, pH 3–10) or osmotic condition (up to final 100 mM sucrose added) was changed, except that PC liposomes aggregated at pH ≈5(Right). (B) PC liposomes before (Left) and after (Right) shrinkage. The video-camera sensitivity was adjusted for every scene because the brightness of the shrunken liposomes increased too much. (C) A sequence of dark-field images of a shrinking liposome. Numbers under the images indicate the time lapse in seconds. Video-camera sensitivity was decreased at 47–63s(*). (D) Increase in the total light intensity (arbitrary units) scattered from a shrinking liposome. Three examples are shown. (B–D) 1 mM PC liposomes were mixed initially with 0.2 mM E5 and then with 0.2 mM K5 by using a mixing chamber. The buffer was 10 mM Hepes·NaOH (pH 7.0). (E) Sequential images showing the solubilization process of shrunken PC-PG liposomes caused by CHAPS. PC-PG liposomes (1 mM lipids/10 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.0) were shrunken with 10 mM Hepes·NaOH (pH 7.0) plus 0.2 mM E5 and 0.2 mM K5, and a few minutes later, the shrunken ones were mixed with a CHAPS solution (1 mM CHAPS/10 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.0) in the mixing chamber to make a concentration gradient of the surfactant. The solubilization process occurred independently from the fusion event. However, under the conditions that we used, the fusion between the shrunken liposomes was observed only rarely in the presence of CHAPS because almost all of them have solubilized before fusing each other. (F) A sequence of the CHAPS-induced burst process of a PC-PG liposome in the absence of fusogenic peptide. Because this PC-PG liposome was double-lamellar, it showed a burst twice. The burst occurred at the times indicated by arrows in G. The conditions were the same as in E, except that it contained no peptide. (G) Decrease in the total light intensities scattered from the two liposomes, caused by the solubilization with CHAPS (blue and red lines show the shrunken and control PC-PG liposomes, respectively). (Bars indicate 5 μm.)

At peptide concentrations <10 μM, PC liposomes did not show any morphological change. As the K5 and E5 concentrations were increased to >30 μM, the liposomes became smaller. By using a mixing chamber, we added 0.2 mM K5 to a mixture of 1 mM PC liposomes and 0.2 mM E5, and we monitored the change in shape of individual liposomes (Figs. 2 and 3). With increasing peptide concentrations, almost all liposomes gradually shrank in size (Fig. 2 B and C). During the shrinking, glittering spots appeared on their membranes, moved around along the membranes, and gradually accumulated. Finally, the liposomes became small spheres with brighter membranes. The light intensity scattered from the liposomal membrane depends very strongly on the number of membrane layers (12). The apparent surface area of liposomes before and after the shrinkage are 20 ± 16 and 3.9 ± 1.5 μm2, respectively (mean ± SD; n = 39). Therefore, if the total area of the membrane of each liposome is maintained during the shrinkage, we could estimate that the membrane might be folded about five times on average because of the shrinking of each liposome, consistent with the result shown in Fig. 2E. The possible folding and piling up of liposomal membranes during the liposome shrinkage was suggested by obervations made by using electron microscopy (see Figs. 4 and 5, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These shrinking processes were irreversible. Even when the peptides were subsequently diluted, the shrunken liposomes never transformed to their original size. To induce any transformation of giant liposome within several minutes by an osmotic effect, addition of ≈1 M sucrose was required. Neither apparent surface area nor light intensity of liposome changed during this transformation (data not shown). Therefore, the liposomal shrinkage described above is not a result of osmotic effect.

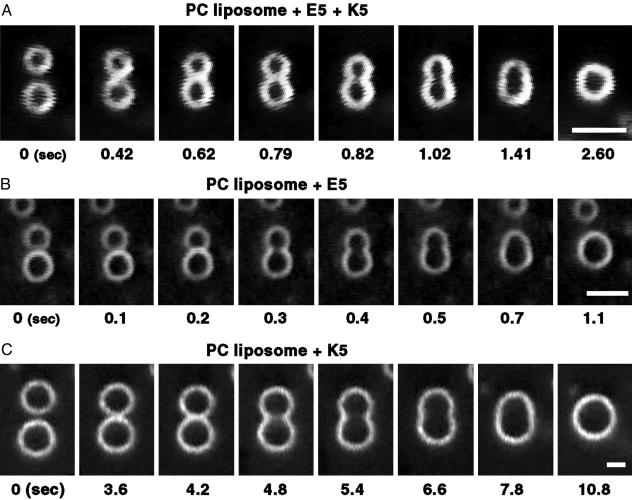

Fig. 3.

Fusion process of shrunken liposomes. Liposome fusion induced by a mixture of K5 and E5 (A), E5 (B), and K5 (C). E5-premixed PC liposomes (1 mM PC/0.2 mM E5/10 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.0) were mixed with K5 (0.2 mM K5/10 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.0) (A) or with 10 mN HCl (B) in the mixing chamber. K5-premixed PC liposomes (1 mM PC/0.2 mM K5/10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.0) were mixed with 10 mN NaOH (C) in the mixing chamber. Liposomes shown had already shrunken. (Bars indicate 5 μm.) In every fusogenic condition (see Table 1), when two shrunken liposomes closely contacted, ≈40% of them fused successfully. In the remaining shrunken liposomes, the two liposomes either continued to attach to each other without fusion (20%) or separated soon (40%). In each condition, >50 samples were examined. The fusion occurred repeatedly between one shrunken liposome and another until they no longer came into contact because of the decrease in their numbers caused by the fusion.

Surprisingly, membrane fusion occurred only among these shrunken liposomes (Fig. 3). When the observation field was moved from the low- to the high-concentration area of the peptide in the mixing chamber, we found the following images in order. (i) The giant liposomes did not yet show any change, (ii) the liposomes shrank and increased the light intensity of their membranes (Fig. 2C), and (iii) fusion occurred between the shrunken liposomes (Fig. 3). Note that when a mixture of K5 and E5 was used to induce fusion, finding a fusion event was easiest because the local area where fusion could be observed was wider than in the other cases. Fusion occurred repeatedly between one fused liposome and another; that is, the fused liposomes also fused again with each other. The shrinkage and subsequent fusion were equally inducible regardless of the adding order of E5 and K5 peptides. Because the shrinkage and fusion of PC liposomes were induced with E5 alone at acidic pH or K5 alone at alkali pH (Table 1), E5 or K5 is not necessarily required for the shrinkage and fusion at alkali or acidic pH, respectively.

Table 1. Liposomal fusion induced by fusogenic peptides.

| PC liposome

|

PC-PG liposome

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mM NaCl

|

100 mM NaCl

|

0 mM NaCl

|

100 mM NaCl

|

|||||

| Peptide | Shrink | Fusion | Shrink | Fusion | Shrink | Fusion | Shrink | Fusion |

| E5 + K5* | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| E5† | ≤6 | ≤6 | ≤6 | ≤6 | – | – | – | – |

| K5† | ≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | ≈7‡ | ≈7‡ | ≈7‡ | ≈7‡ |

| HA† | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Effects of lipid composition and salt concentrations are summarized. The pH ranges in which shrinkage or fusion occurred are shown (change or no change at the all-examined pH range are indicated by + or –, respectively). Reproducibility was confirmed by three experiments. PC, phosphatidylcholine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol.

Liposomes were mixed with E5 (1 mM lipids/0.2 mM E5) and then with K5 (0.2 mM) by using a mixing chamber. The buffer contained 10 mM MES·NaOH (pH 5.0), HEPES·NaOH (pH 7.0), or Tris·HCl (pH 9.0), with or without 100 mM NaCl

Liposomes (1 mM lipids/10 mM HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.0) were mixed with a peptide solution (0.2 mM E5, K5, or HA/10 mM HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.0) in the mixing chamber, or liposomes premixed with peptide (1 mM lipids/0.2 mM peptide/10 mM MES·NaOH or Tris·HCl, pH 7.0) were then mixed with 10 mM HCl or NaOH in the mixing chamber, respectively, with or without 100 mM NaCl

With mixing of HCl or NaOH, shrinkage and fusion did not occur

Fusion took place very rapidly (i.e., it finished within the 33-ms time-resolution limit). Subsequently, the fusion pores became larger, and the fused liposomes transformed from peanut shape to spherical shape within several seconds (Fig. 3). The fusion process was independent of salt concentration, at least up to 100 mM of NaCl. An interesting question is whether the fusion causes a change in the total surface area of the liposome membrane. From video images, we calculated the surface area and the volume of liposomes before and after the fusion. The ratio of the surface change did not depend on the size of the liposomes. After the fusion, on average, the total surface area decreased to 86 ± 10%, whereas the total volume increased 110 ± 20% (mean ± SD; n = 26). These results indicate that the liposome membrane shrank slightly during the fusion, whereas the total volume increased slightly. In the mixture of E5 and K5 at neutral pH, the same shrinkage and fusion processes also took place among giant PC-PG liposomes (made of PC and PG) (Table 1). However, at neutral pH, the shrinkage and fusion of PC-PG liposomes was induced even by K5 peptide alone (Table 1), indicating that E5 is not necessarily required for shrinkage and fusion at neutral pH.

What change in membrane organization causes the liposomal shrinkage? The light intensity scattered from a liposomal membrane reflects its thickness. Scattering intensity from the shrinking liposome increased in one step (Fig. 2D), although the rate of increase depended on the peptide concentrations or the means of solution mixing (see Fig. 5). Additionally, we reported (15) that CHAPS induces the sudden bursting of PC-PG liposome. If the shrink is a result of the transformation from a unilamellar to a multilamellar liposome, the light intensity of the liposome should decrease in a stepwise manner each time that a lipid bilayer bursts (Fig. 2 F and G). The light intensity of the shrunken PC-PG liposomes, however, decreased exponentially, but not in a stepwise manner, with time (Fig. 2 E and G), and their brightness became heterogeneous along the membrane (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that the shrinking may result from bending folds in the membrane rather than from multilamellarization of the liposome.

Shrinkage and Fusion of Liposomes Are Induced by E5 at Acidic pH. It has been reported that the E5 peptide alone induces the fusion of PC-LUVs at acidic pH (18). Thus, we mixed PC liposomes with E5, and monitored them in a pH gradient in the mixing chamber (Fig. 3B). In the area of neutral pH, the liposomes maintained their spherical shape and did not show any shape change. However, when the pH decreased to a pH of ≈5, the liposomes shrank and their diameters were reduced by more than one half, and the light intensity of their membranes increased (Fig. 2 B and C). pH 5 has been reported to be optimal for the E5-induced fusion of LUVs. Only the shrunken liposomes fused with each other (Fig. 3B). The fusion occurred repeatedly between one fused liposome and another, and each fusion process was completed within several seconds. The E5-induced liposome fusion was independent of the salt concentration, at least up to 100 mM. These shrinkage and fusion events occurred at E5 concentrations >30 μM, and they were the same as those that occurred in the mixture of K5 and E5. However, when PC-PG liposomes were used other than PC liposomes, no E5-induced morphological changes took place (Table 1).

Shrinkage and Fusion of Liposomes Are Induced by K5. It has been reported that K5 causes the fusion of LUVs at alkaline pH (18). To examine this fusion mechanism precisely, we examined whether the K5 peptide causes fusion in our system when the pH is varied. When the K5 concentration was raised to >30 μM, liposome shrinkage and subsequent fusion were observed at alkaline pH (Fig. 3C). PC liposomes were mixed with K5 in a mixing chamber with a pH gradient, and the liposome behavior was then monitored. As the pH approached 9, the giant liposomes shrank and increased the light intensity scattered from their membranes (Fig. 2 B and C). Fusion occurred repeatedly between one fused liposome and another (Fig. 3C). Each fusion event was completed within several seconds.

When PC-PG, rather than PC, liposomes were used, K5-induced fusion occurred at a neutral pH but not at an alkaline pH (Table 1). The fusion process (i.e., the fusion subsequent to the shrinkage) was the same as observed for PC liposomes. Therefore, it seems critical to the fusion process that the electric charge of the membrane is neutralized by the charge of the fusogenic peptide. The fusion process of the K5-induced liposome was independent of the salt concentration, at least up to 100 mM, regardless of lipid composition.

The HA Peptide Does Not Induce the Fusion of Giant Liposomes. To investigate the ability of the HA peptide to cause membrane fusion (16), PC or PC-PG giant liposomes were mixed with HA in a pH gradient generated in the mixing chamber. However, HA did not show any effect on giant liposomes, even at acidic pH, which was reported as being optimal for the fusion of PC-LUVs (Table 1). Even when the pH was decreased to <3, liposomal fusion never occurred. These negative results were independent of the salt concentration, at least up to 100 mM. Because the fusogenic activity of the peptides against PC-LUVs was confirmed (data not shown) by the conventional methods (16-18), the negative result with HA might come from the fact that giant liposomes were used in this study. At acidic pH, only the aggregation of PC liposomes was seen. However, this aggregation was observed also in the absence of HA (Fig. 2 A Right), indicating that the aggregation is due to a property of PC liposomes.

Discussion

Fusion of PC-LUVs induced with HA, E5, and/or K5 peptides have been studied by conventional fluorescence methods, such as lipid mixing and internal-content mixing (16–18, 23, 24). Those studies were based on average data that were obtained with huge numbers of vesicles, and they showed that the fusion finished within several 10-s periods. In contrast, in our study, individual fusion events of giant liposomes were observed directly. Fusion itself is actually a very rapid process and is faster than the time resolution (33 ms) of our method. And surprisingly, we found that influenza hemagglutinin-related fusogenic peptides caused the shrinkage of giant liposomes. The liposomal shrinkage before the fusion always occurred in every condition in which liposomes fused (Table 1). Therefore, the shrinkage is probably indispensable to the subsequent fusion event. In addition, changes in liposomal shape after fusion were discovered. These processes could not be detected by using the previous conventional methods.

The most mysterious problem involved in this study is the mechanism of shrinkage. The surface area of each shrunken liposome decreases several times, so that bending folds of the membrane and/or multilamellarization could be proposed to occur. Inhomogeneous increasing of light intensity from the shrinking liposomes and CHAPS-induced nonstepwise solubilization of the shrunken PC-PG liposomes seem to support the former mechanism. Fusion images of the shrunken liposomes seem to be single-layered liposomes fused with each other. This observation might support the bending-folds mechanism also. However, as a third possibility, the shrunken liposome could have an unknown thick-membrane structure composed of lipids and amphiphilic peptides. Further detailed investigations, using, for example, quick-freezing electron microscopy, will be necessary to elucidate the specific mechanism involved.

It has been reported that peptides HA, E5, and K5 are equally able to induce membrane fusion between PC-LUVs (16–18). In this study, however, E5 and K5, but not HA, caused the fusion between giant PC liposomes. The pH range at which giant liposomes fused was similar to the pH range that has reported for LUVs. E5 and K5 are the synthetic negatively and positively charged analogue peptides of HA, respectively (Fig. 1). The HA peptide has only two anionic amino acid residues. In contrast, E5 and K5 possess five anionic and cationic residues, respectively. When PG, an acidic phospholipid, was used to generate the liposomal membrane, the K5-induced fusion no longer required a high pH. These results indicate that more charged residues and neutralization of the charges (17, 18, 23) may be required to induce fusion between giant liposomes. It has been reported that membrane destabilization is essential for fusion (18, 24, 25). The many charged residues of the fusogenic peptides are probably involved in inducing strong perturbations into the lipid bilayer, and such strong perturbations may cause severe membrane bending folds. Although NaCl usually shows some effect on interactions derived from electrical charges, the fusogenic activity of the E5, K5, and combined peptides observed in this study was not altered by NaCl, at least at concentrations less than the physiological NaCl strength.

The major difference between LUVs and giant liposomes is their size. LUVs are 0.1–1 μm in diameter, whereas giant liposomes are 1–20 μm, which results in different membrane curvatures. Fusogenic peptides may penetrate more efficiently into membranes with larger curvatures and may destabilize the lipid bilayer structures, making fusion easier (26). Consequently, fusogenic peptides possess few charges, and HA causes fusion only between LUVs, but not giant liposomes, because only LUVs possess a large curvature. Because the influenza virus is almost equal to a LUV in size, the HA peptide may be sufficient only for fusion between the virus and cellular membranes, as occurs physiologically. In other words, because the HA peptide consists of the 20-aa sequence derived from the N-terminal fusion peptide region of the influenza hemagglutinin HA2 subunit, a larger part, such as a triple-coiled coil region of the HA2 subunit might be required also to induce membrane fusion (27–30).

Inversely, the lower curvature of the lipid bilayer may make fusion too difficult. For example, at least 30 μM peptide was required to induce fusion of giant liposomes, a concentration almost three times higher than that required to induce fusion of LUVs (18). The pH required for fusion of giant liposomes induced by E5 was <5, which is also a more acidic pH than required for fusion of LUVs. LUVs fused at pH <6 (18).

Fusion pores opened within 33 ms, whereas the change from peanut shape to spherical shape required several seconds. Rapid-fusion pore formation may result from the reorganization of two attached, strongly perturbed lipid bilayers. Details of this process remain to be revealed, for example, by using a high-speed video camera and/or other microscopes together. Because the volume of liposomes increased during the shape change, it seems likely that water molecules permeate into the fusing liposome through the destabilizing lipid bilayer (12), requiring much longer fusion times.

This study directly monitors the real-time process of membrane fusion successfully, such that it should be a useful approach for revealing mechanisms of membrane behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 13680738.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: LUV, large unilamellar vesicle; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl]dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate.

References

- 1.Hughson, F. M. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 49-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwardson, J. M. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 390-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramalho-Santos, J. & de Lima, M. C. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1376, 147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White, J. M. (1990) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 52, 675-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal, R., Clague, M. J., Durell, S. R. & Epand, R. M. (2003) Chem. Rev. (Washington, D.C.) 103, 53-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lei, G. & MacDonald, R. C. (2003) Biophys. J. 85, 1585-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanaseki, T., Kawasaki, K., Murata, M., Ikeuchi, Y. & Ohnishi, S. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 137, 1041-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takiguchi, K., Nomura, F., Inaba, T., Takeda, S., Saitoh, A. & Hotani, H. (2002) ChemPhysChem 3, 571-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bangham, A. D. (1995) BioEssays 17, 1081-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasic, D. D. (1995) In Handbook of Biological Physics, eds. Lipowsky, R. & Sackmann, E. (Elsevier, Amsterdam), pp. 491-519.

- 11.Lipowsky, R. (1991) Nature 349, 475-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotani, H. (1984) J. Mol. Biol. 178, 113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saitoh, A., Takiguchi, K., Tanaka, Y. & Hotani, H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1026-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda, M., Takiguchi, K., Ishikawa, S. & Hotani, H. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 287, 293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura, F., Nagata, M., Inaba, T., Hiramatsu, H., Hotani, H. & Takiguchi, K. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2340-2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murata, M., Sugahara, Y., Takahashi, S. & Ohnishi, S. (1987) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 102, 957-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murata, M., Kagiwada, S., Takahashi, S. & Ohnishi, S. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 14353-14358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murata, M., Takahashi, S., Kagiwada, S., Suzuki, A. & Ohnishi, S. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 1986-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubovskii, P. V., Li, H., Takahashi, S., Arseniev, A. S. & Akasaka, K. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 786-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishiguro, R., Matsumoto, M. & Takahashi, S. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 4976-4983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi, S. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 6257-6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takiguchi, K. (1991) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 109, 520-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murata, M., Shirai, Y., Ishiguro, R., Kagiwada, S., Tahara, Y., Ohnishi, S. & Takahashi, S. (1993) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1152, 99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murata, M., Takahashi, S., Shirai, Y., Kagiwada, S., Hishida, R. & Ohnishi, S. (1993) Biophys. J. 64, 724-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efremov, R. G., Nolde, D. E., Volynsky, P. E., Chernyavsky, A. A., Dubovskii, P. V. & Arseniev, A. S. (1999) FEBS Lett. 462, 205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lentz, B. R., McIntyre, G. F., Parks, D. J., Yates, J. C. & Massenburg, D. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 2643-2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han, X., Bushweller, J. H., Cafiso, D. S. & Tamm, L. K. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 715-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leikina, E., LeDuc, D. L., Macosko, J. C., Epand, R., Shin, Y. K. & Chernomordik, L. V. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 8378-8386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu, Y. G., King, D. S. & Shin, Y. K. (1994) Science 266, 274-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr, C. M. & Kim, P. S. (1993) Cell 73, 823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.